Abstract

A young apparently healthy, non-diabetic, HIV non-reactive woman presented with a mycetoma-like lesion on right buttock. Discharge was scanty, and mycotic grains were not seen. Biopsy of sinus track was obtained for microscopy and culture. Microscopic examination revealed plenty of fungal hyphae in direct microscopic examination of grounded tissues in saline; KOH, Gram's, and H and E-stained smears. All the three inoculated slants of Sabouraud's media yielded heavy growth of Fusarium solani. Presence of numerous hyphal fragments in direct microscopy and heavy growth of F. solani in all three slants indicative of etiological role of fungus in the present case. It is probably a first report of F. soloni mycetoma from India.

Keywords: Fusarium solani, granulomatous fusariosis, mycetoma

Introduction

Mycetoma is a chronic slowly progressive subcutaneous granulomatous infection characterized by triad of swelling, multiple sinus track formation, and discharge of granules. True fungi, actinomycetes, and bacterial species are known to be etiological agents. At least 23, true fungal species have been accepted as causative agents of eumycetoma.[1] some more fungal agents are possible contenders of place in the list. Of the 23 fungal species only two species are of common occurrence, 5 are of rare occurrence, and remaining 16 species are of exceptional occurrence. Fusarium solani belongs to the exceptional category[1]

Globally about 50% of mycetomas are eumycetomas and rest are actinomycetomas.[1] Mycetoma is a fairly common condition in India as in other tropical countries. Occurrence of eumycetoma in India is relatively lower at 35%, while actinomycetomas account for the remaining 65% cases.[2] We could not find any report of Fusarium mycetoma from India.

Case Report

A 30-year-old female housewife belonging to low socio-economic status presented with mildly painful swelling of 4 years duration on right buttock. There was no history of injury or prick.

On examination, the patient was apparently healthy, with mild pallor. There was no other significant finding. Local examination showed swelling on right buttock of 6×7 cm with three sinuses. The mass was firm, adherent to skin but not to the pelvic bone. There was moderate tenderness and scanty discharge. Sinus openings were non-flared, non-inflamed and blocked with dried up exudates.

Peripheral smear of blood was within normal limits. She was non-diabetic and HIV non-reactive. X-ray of affected buttock showed that the underlying bones were not affected. There was no other abnormal finding.

In spite of repeated efforts, mycotic grain could not be obtained either in the pus discharge, which was scanty, or on the surface of dressing. Hence, a biopsy of sinus track was undertaken. A piece of tissue of 8×8 mm was obtained and was grounded with sterile pestle and mortar with all aseptic precautions inside a laminar flow cabinet.

A saline mount, KOH mount, Gram's-stain smear, and modified acid fast stain decolorized with 1% sulphuric acid and H and E stained smears were examined.

Grounded tissue was inoculated on three slants of SDA. The inoculum was liberally applied in a zigzag pattern. Two slants were incubated at room temperature and the third at 37°C.

Three control slants inoculated with sterile saline were incubated simultaneously, one at room temperature and two at 37°C.

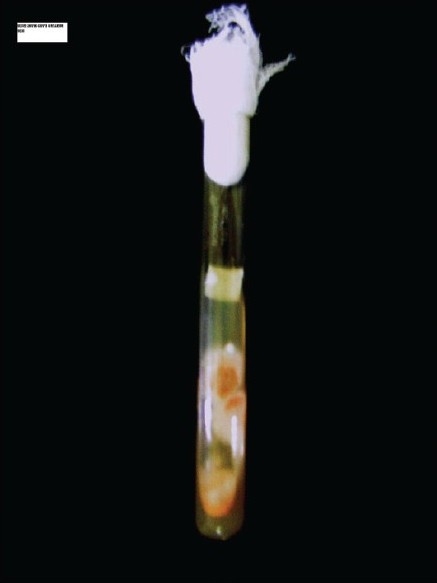

Saline mount, KOH mount, Gram's stain, and H and E smear all showed fungal hyphal fragments in abundance. With 10× objective, many of the fields showed several hyphal fragments ranging from 50 to 500 μm in length. Hyphae we re 3–6 μm in width, septate and smooth. In unstained mounts, hyphae were nonpigmented [Figure 1]. All three slants showed multiple colonies distributed along the zigzag track of inoculation. The growth was visible in 24 h and matured on the third day. The growth was loose cottony white, which turned golden yellow on maturity. The reverse was nonpigmented [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Wet mount of tissue showing hyphal fragment

Figure 2.

Growth of Fusarium solani

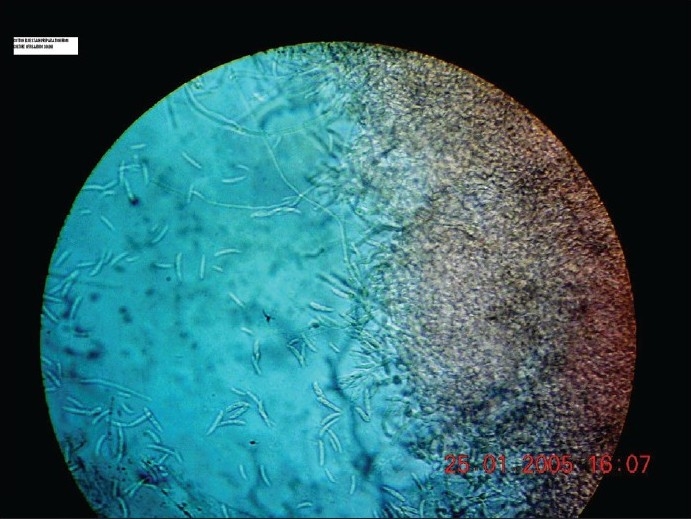

Microscopy of the growth showed 4–6 μm broad septate, non-pigmented tangled hyphal growth. The macro conidia were produced in abundance, and were crescent shaped, 2–4 celled, thick walled [Figure 3]. Moderate numbers of ovoid 3–4 μm micro conidia born latterly on vegetative hyphae were observed. The fungus was identified as F. solani.[1] Control slants did not show any growth even after 3 weeks of incubation.

Figure 3.

Wet mount of culture showing macrospores and hyphae

Discussion

F. solani is widely distributed plant pathogen. Fusarium species have been reported from variety of clinical conditions like keratitis, skin infection in burns, variety of skin lesions, arthritis, peritonitis, systemic infection in immunocompromised hosts, systemic, and granulomatous diseases, in aplastic anemia.[1] Recently, a case of breast abscess in diabetic patient has been reported.[3]

The earliest documented Fusarium mycetoma report is from Senegal.[4] It was a white grain mycetoma. It is argued that some of the earlier reports of white grain mycetoma reported as to be due to Cephalosporium species might have been actually due to Fusarium species. It is contemplated that Fusarium species might have failed to sporulate on certain culture media used in those times leading to wrong reporting.[4] Giving credence to this argument is report of Ajello et al[5] who in 1985 restudied a case of white grain mycetoma reported previously as Acremonium species, and found some of them to be Fusarium moniliformae mycetoma on the basis of culture studies.

Recently two cases of F. solani mycetoma have been reported. One of it was an osteolytic mycetoma of hand[6] and another of foot.[7] The later case has been diagnosed by DNA sequencing, as the fungus could not be grown in cultures.

Demonstration of well-formed granule seems to be difficult in case of F. solani. Tomimori-Yamashita et al[6] have stated that no macroscopic grains were observed and histopathological findings showed grains consisting of numerous hyphae. It seems that there was no cementing substance and the same has been acknowledged by Ajello et al.[5]

We too could not demonstrate granules macro or microscopically, but crushed tissue showed abundant hyphal elements in tissue. Further, all the three slants showed numerous colonies on the zigzag line of inoculation, while control slants remained sterile thus ruling out laboratory contamination. As the patient did not return for follow up, repeat sampling for histopathological study could not be done. This is probably the first ever report of F. solani mycetoma from India. Since mycotic granules were not formed, authors feel that the lesion may be better labeled as, “granulomatous fusariosis.”

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rippon JW. Medical Mycology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chander J. Textbook of Medical Mycology. 1st ed. New Delhi: Mehta Publisher; 1995. pp. 114–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anandi V, Vishwanathan P, Sasikala S, Rangarajan M, Subramaniyan CS, Chidambaram N. Fusarium soloni breast abscess. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005;23:198–9. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.16596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emmons CW, Chapman H, Binford JP. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1977. UTZ, K.J. Kwon-Chung Medical Mycology. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajello L, Padhye AA, Chandler FW, McGinnis MR, Morganti L, Alberici F. Fusarium moniliformae, a new mycetoma agent: Restudy of a European case. Eur J Epidemiol. 1985;1:5–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00162306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomimori YJ, Ogawa MM, Hirata SH, Fischman O, Michalany NS, Yamashita H.K, et al. Mycetoma caused by Fusarium solani with osteolytic lesion on the hand: A case report. Mycopathologia. 2002;153:11–4. doi: 10.1023/a:1015294117574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yera H, Bougnoux ME, Jeanrot C, Baixench MT, De Pinieux G, Dupony-camet J. Mycetoma of the Foot caused by Fusarium Solani: Identification of the Etiological Agent by DNA Sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1805–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1805-1808.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]