Abstract

Primary cutaneous actinomycosis caused by Actinomyces israelii occurs most commonly in the cervicofacial area. It commonly presents as “lumpy jaw” with draining sinuses which discharge the characteristic “sulfur granules”. A low index of suspicion and a low sensitivity in culturing the organism, due to its fastidious nature often delays the diagnosis. An atypical clinical presentation mimicking lymphangioma circumscriptum with grouped papulovesicular and nodular lesions along the lower jaw extending from skin to the inner buccal mucosa, confirmed on histology and an excellent therapeutic response to penicillin is reported.

Keywords: Cervicofacial actinomycosis, lymphangioma, mimicker

Introduction

Cervicofacial actinomycosis is an uncommon chronic suppurative and granulomatous disease caused by Actinomycetes that are normal inhabitants of the oral cavity. It spreads to contiguous tissues following disruption of anatomical barriers by trauma, surgery or infection. It presents as chronic suppurative or indurated mass with draining sinuses overlying the mandible or as an acute painful swelling in the submandibular region.[1] We report an unusual case of cervicofacial actinomycosis clinically resembling lymphangioma circumscriptum without the characteristic draining sinuses or granules, with the demonstration of actinomycotic granule on histology and confirmed subsequently with an excellent response to penicillin.

Case Report

A 22-year-old farmer from Jalgaon was referred to us for asymptomatic spongy red raised lesions on the right side of his chin since 3 months. It started as a single red raised lesion resembling an insect bite which gradually increased in size and firmness. On reaching the size of a one rupee coin, numerous solid and fluid filled small lesions started developing on the plaque in close proximity to each other. They would rupture spontaneously to release scanty, viscid, odorless, clear fluid, and occasionally blood. There was no discharge of grains or bony particles. There was no history of preceding congenital anomaly, trauma, dental infection, use of dentures, or plant twig for brushing teeth. One and half month later, he noticed similar lesions on the mucosal aspect of the chin corresponding to the external lesions discharging similar clear, odorless, and salty fluid. He was a chronic gutkha chewer since 7–8 years.

Examination revealed an ill defined, nontender, indurated dusky red plaque measuring 4 × 5 cm2 on the right side of the chin extending vertically from the angle of the mouth to the lower border of the mandible and horizontally from the mentum to 6 cm laterally [Figure 1]. Overlying the indurated area were multiple spongy papulovesicles and sessile nodules of variable size, closely grouped giving a “frogspawn appearance” and on rupturing discharged clear, viscid, odorless fluid without granules, pus or bony particles. These lesions extended to the corresponding buccal mucosa as smaller white papules with difficulty to insinuate a finger between the mucosa and mandible. There were enlarged, nontender, matted cervical lymph nodes.

Figure 1.

Grouped translucent pink spongy papulovesicular and nodular lesions simulating lymphangioma

A differential diagnosis of lymphangioma circumscriptum, lymphangiosarcoma, lupus vulgaris, actinomycosis, and deep fungal infection were considered on clinical findings.

Routine hematological investigations were normal, and local radiological examination did not reveal bony involvement or retained tooth. Repeated samples of the discharge subjected to gram staining for actinomycetes, potassium hydroxide mount for fungus and Ziehl Nelson staining for Nocardia and mycobacterium were negative. FNAC from the cervical lymph node revealed inflammatory infiltrate. Skin biopsy was subjected to histology and cultures for aerobes, anaerobes, mycobacterium, and fungus. CT scan revealed diffuse thickening of skin and subcutaneous tissue without bony involvement. Histology revealed a hyperkeratotic and acanthotic epidermis with the deep dermis showing slender-beaded Gram-positive filaments crowded at the center and radiating parallely along the border suggestive of actinomycotic granule. They were surrounded by dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate and demonstrated the “Splendore Hoeppli” phenomenon [Figure 2]. However, repeated cultures did not grow any organism. On the basis of histopathological demonstration of grain, a final diagnosis of cervicofacial actinomycosis was made, with the clinical presentation masquerading as lymphangioma circumscriptum. The patient was treated with injection crystalline penicillin 4 million units intravenously thrice daily for 6 weeks with tablet cotrimoxazole 960 mg twice daily. After 6 weeks, the intravenous route was to oral Penicillin G 400 mg twice daily with continuation of cotrimoxazole. There was significant reduction in the size of the entire plaque and individual lesions within the first month of therapy and complete clinical resolution by 4 months [Figures 3 and 4].

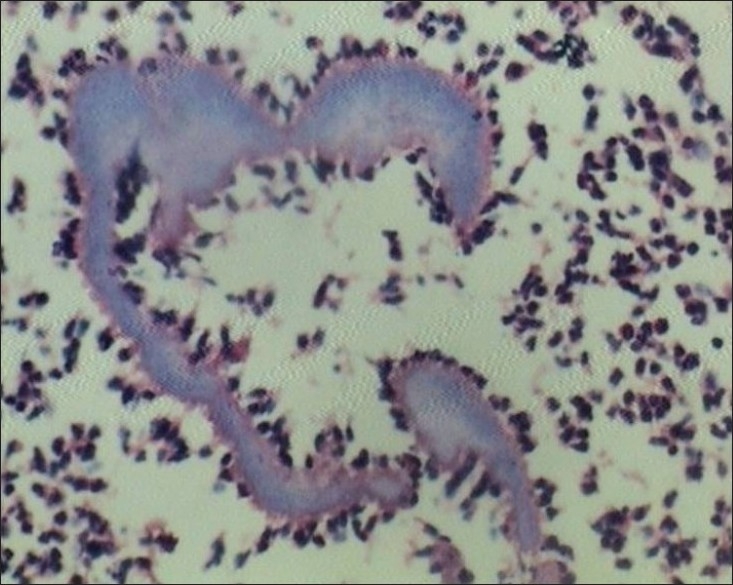

Figure 2.

H and E stain; ×100 showing basophilic granule with peripheral eosinophilic ray-like projections suggestive of “actinomycotic” granule.

Figure 3.

Resolving papulovesicular lesions after 4 weeks of treatment

Figure 4.

Complete clinical resolution after 4 months of therapy

Discussion

Cervicofacial actinomycosis presents in two distinct morphological patterns; first “lumpy jaw”, a slow enlarging, fluctuant painless swelling over the lower border of mandible and second, more painful and widespread, simulating an acute pyogenic infection affecting the submandibular area.[1] Other variants include chronic osteitis, osteolytic lesion, hard nodule on the tongue, lockjaw, parapical, or paradental abscess.[2]

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is a hamartomatous malformation of the lymphatic system of deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue clinically characterized by clusters of thin-walled vesicles giving a “frog spawn” appearance.[3] They occur as congenital abnormality or as acquired damage to lymphatic channels typically seen in post-radiation.[4] The most common sites affected are head and neck, differentials in this region include plunging ranula, hemangioma, branchial cleft cyst, thyroglossal duct cyst, varix, lipoma, schwannoma, parotid cyst, malignant tumors or metastases, herpes simplex, angioma serpiginosum, lymphangiectasia, angiokeratoma corporis circumscriptum, etc. However, actinomycosis has never been reported to mimic this condition in the literature excepting a case report in a study where fungal infection was observed to cause acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum of the oral cavity.[5]

Maxillofacial trauma in any form is an important risk factor for cervicofacial actinomycosis which was not noted in our case. This history cannot be elicited in 40% of cases.[6] In 28 cases of cervicofacial actinomycosis described by Weese and Smith, 89% had palpable mass, 61% had visible sinus tract or fistula, 54% had both, and 40% had lymphadenopathy.[7] The classic formation of draining sinus tracts with sulfur granules is seen in approximately 40% of cases.[2] Our patient had palpable mass with regional lymphadenopathy but no sinus tracts or sulfur granules.

Cultures are positive in less than 50% cases due to fastidious nature of the organism.[8] Diagnosis is often based on the morphology of granules, seen as basophilic masses with a granular center and a radiating fringe of club-shaped protrusions on histology which was noted in our case.[1] However, in our case, no histological correlation could be established for the vesicular nature of the skin lesions noted clinically and that remains elusive. CT and MRI yield only quantitative information such as localization, borders, invasion of surrounding organs, and homogeneity of lesion.[9]

The current recommended therapy includes 4 weeks of high-dose IV Penicillin followed by a 3 to 6 month course of oral penicillin, continuing treatment even after total resolution of symptoms. This was found to be extremely useful in our case.[1]

Acknowledgments

We hereby acknowledge our sincere gratitude and respects to all the resident doctors and teachers of the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy and the Department of Pathology and Microbiology at Grant Medical College and Sir J J Hospital, Mumbai who have contributed towards the clinical diagnosis, treatment and intellectual inputs to the write-up of this case.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Çiftdoðan DY, Bayram N, Akalýn T, Vardar F. Actinomycosis in differential diagnosis of cervicofacial mass: A Case Report. J Pediatr Inf. 2009;3:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tortorici S, Burruano F, Buzzanca ML, Difalco P, Daniela C, Emiliano M. Cervico-facial actinomycosis: epidemiological and clinical comments. Am J Infect Dis. 2008;3:204–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anees A, Yaseen M, Sherwani R, Khan MA. Extensive lymphangioma circumscriptum - A case report. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2006;7:55–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal K, Gupta S, Jain VK, Marwah N. Congenital lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva - a case report. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:428–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poh CF, Priddy RW. Acquired oral lymphangioma circumscriptum mimicking verrucous carcinoma. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41:277–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagral SS, Patel CV, Pathare PT, Pandit AA, Mittal BV. Actinomycotic pseudo-tumor of the mid-cervical region. J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:62–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weese WC, Smith IM. A study of 57 cases of actinomycosis over a 36 year period. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton N, Cook C. Allergic granulomatous nodules of the eyelid and conjunctiva. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancella A, Abbate G, Foscolo AM, Dosdegani R. Two unusual presentations of cervicofacial Actinomycosis and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:89–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]