Abstract

Cocolonization of human mucosal surfaces causes frequent encounters between various staphylococcal species, creating opportunities for the horizontal acquisition of mobile genetic elements. The majority of Staphylococcus aureus toxins and virulence factors are encoded on S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs). Horizontal movement of SaPIs between S. aureus strains plays a role in the evolution of virulent clinical isolates. Although there have been reports of the production of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1), enterotoxin, and other superantigens by coagulase-negative staphylococci, no associated pathogenicity islands have been found in the genome of Staphylococcus epidermidis, a generally less virulent relative of S. aureus. We show here the first evidence of a composite S. epidermidis pathogenicity island (SePI), the product of multiple insertions in the genome of a clinical isolate. The taxonomic placement of S. epidermidis strain FRI909 was confirmed by a number of biochemical tests and multilocus sequence typing. The genome sequence of this strain was analyzed for other unique gene clusters and their locations. This pathogenicity island encodes and expresses staphylococcal enterotoxin C3 (SEC3) and staphylococcal enterotoxin-like toxin L (SElL), as confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) and immunoblotting. We present here an initial characterization of this novel pathogenicity island, and we establish that it is stable, expresses enterotoxins, and is not obviously transmissible by phage transduction. We also describe the genome sequence, excision, replication, and packaging of a novel bacteriophage in S. epidermidis FRI909, as well as attempts to mobilize the SePI element by this phage.

INTRODUCTION

Common genetic processes drive the evolution of both pathogens and commensals in response to selective environmental pressures. Thus, instances where two related species in a common environmental niche evolve toward divergent lifestyles (one as a pathogen and the other as a commensal) are especially significant for understanding of the evolution of pathogenicity.

Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are Gram-positive colonizers of the human mucosal surfaces and frequently encounter each other during mixed infections at various sites. The two species share a core genome of 1,681 genes (14) but differ significantly in their accessory genomes, composed of the flexible gene pool that is found only in some strains of a species and usually contributes an evolutionary benefit in specific environments (13, 20). Sequenced S. epidermidis genomes lack several genes common to the accessory genome of S. aureus, including those encoding superantigen toxins, certain proteases, and staphylokinase (20). The accessory genome and mobile genetic elements of S. epidermidis have been poorly characterized thus far, with only a few recent reports of conjugative plasmids and bacteriophages (9, 15). S. aureus, however, encodes more than 400 accessory genes, present on genomic islands, bacteriophages, and transposons, that account for the majority of toxins, resistance genes, and virulence determinants identified in the species (14). Antibiotic resistance genes are typically transferred by conjugative plasmids and recombination events, whereas phage-mediated transduction is the most common mechanism for the mobilization of superantigen toxins (27).

Lateral transfer of superantigen genes by transduction of S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs) among several strains of S. aureus is a well-characterized event (26, 30, 32), as is lateral transfer of such genes to related species, such as Staphylococcus xylosus and Listeria monocytogenes (3). SaPIs, which are chromosomal mobile elements with a conserved genome organization, typically comprise flanking site-specific attachment (att) sequences, one or more toxin genes, and a unique set of genes that enable their mobilization in conjunction with temperate phages such as φ11, φ13, and 80α (27).

The genetic processes that enable S. aureus to selectively stabilize and extensively exchange virulence determinants are poorly understood. From an evolutionary standpoint, toxin genes are equally relevant to the S. aureus host and to the persistence of the pathogenicity islands that transmit them among host genomes (13). Although recent reports have identified SaPI-like structures (lacking enterotoxins) in the sequenced genomes of Staphylococcus haemolyticus (27, 29) and Staphylococcus saprophyticus (18), and other studies have shown the presence of enterotoxin genes in several species of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) (6, 7, 33), there is no evidence so far to suggest that mobile elements in these staphylococcal commensals exchange virulence-associated genes as promiscuously as is seen in the S. aureus accessory genome.

In 2007, we presented the first evidence of a SaPI-like pathogenicity island and the expression of enterotoxins in a strain identified as S. epidermidis strain FRI909 (20a). The crystal structure of staphylococcal enterotoxin C3 (SEC3) from this strain has been reported previously as well (4). We report here the draft genome sequence of S. epidermidis strain FRI909, the complete sequence of a superantigen-bearing genomic island in strain FRI909, the transcriptional and translational expression of SEC3 and staphylococcal enterotoxin-like toxin L (SElL), and the sequence, excision, and packaging of a novel bacteriophage, φ909.

(Part of this work was presented at the 107th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in 2007.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture.

All bacterial strains used in this study were grown overnight at 37°C on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar medium. Broth cultures were grown aerobically in BHI broth at 37°C. S. epidermidis strain FRI909 was obtained from Merlin Bergdoll, formerly of the Food Research Institute, Madison, WI. S. epidermidis strain RP62a is a methicillin-resistant, biofilm-producing isolate whose genome is one of the two sequenced S. epidermidis genomes (14). S. epidermidis 414, referred to as HER1292 in this study, is commonly used as a phage recipient strain of S. epidermidis (8, 9) and was kindly provided by Vincent Fischetti of the Rockefeller University. Taxonomic identification of S. epidermidis FRI909 was initially conducted by biochemical assays (API Staph ID test), determination of the absence of coagulase production and its gene, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) of the gap and tuf genes, and multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Complete genome sequencing was subsequently used to confirm the genetic identity of the strain.

DNA methods.

Staphylococcal cells were lysed by lysostaphin treatment at 37°C for 30 min, and genomic DNA was isolated using the Qiagen (Valencia, CA) DNeasy kit. General DNA manipulations were performed by standard procedures (1).

Whole-genome sequencing and annotation of S. epidermidis FRI909.

FRI909 was sequenced by 454 FLX pyrosequencing (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) to 20-fold coverage across the genome. Sequence assembly was completed using GS De Novo Assembler software (Roche) and resulted in 69 contigs greater than 500 bp, ranging from 558 bases to 293 kbp. The genome sequences linking the contigs comprising the S. epidermidis pathogenicity island (SePI) and φ909 were confirmed by Sanger dideoxy sequencing (see the footnotes to Tables 1 and 2). Genome annotation of Staphylococcus epidermidis FRI909 was performed at The Institute for Genomic Sciences (IGS), University at Maryland School of Medicine, using the IGS Annotation Engine (http://ae.igs.umaryland.edu/cgi/index.cgi). The genomes of Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228 and RP62A were downloaded from GenBank. Coding sequences with at least 50 amino acids were extracted from GenBank files, and orthologs and recent paralogs were determined using OrthoMCL with the default parameter set (i.e., a BLAST E value cutoff of 1e−5 and an inflation parameter of 1.5) (19). Briefly, all-against-all BLASTp searches were first performed to reveal putative pairs of orthologs or recent paralogs based on reciprocal BLAST. Recent paralogs are defined as genes within the same genome that are reciprocally more similar to each other than to any sequence from another genome. BLAST P values were converted to a normalized similarity matrix by OrthoMCL. The matrix was analyzed by MCL, a Markov Cluster algorithm based on probability and graph flow theory (http://www.micans.org/mcl/), to generate a set of clusters. Each cluster contained a set of orthologs and/or recent paralogs.

Table 1.

ORFs identified in genomic islands and the SePIa in S. epidermidis FRI909

| ORFb | Locus ID | Size (bp) | Size (kDa) | Predicted function | Most significant database match (E value) | % aa identity (similarity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GSEF_0620 | 231 | 9.12 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein SERP0452, S. epidermidis RP62a (1e−36) | 99 (99) |

| 2 | GSEF_0619 | 945 | 44.5 | Integrase | Integrase, S. aureus MW2 genomic island Saα3mw (5e−173) | 92 (97) |

| 3 | GSEF_0618 | 297 | 12.7 | Unknown | No significant match | |

| 4 | GSEF_0617 | 477 | 26 | Packaging protein, SaPI | ORF007, S. aureus SaPI1028 (7e−25) | 38 (62) |

| 5 | GSEF_0616 | 336 | 21 | Packaging protein, SaPI | ORF010, S. aureus SaPI1028 (4e−25) | 58 (78) |

| 6 | GSEF_0615 | 342 | 13.8 | Packaging protein, SaPI | ORF014, S. aureus SaPI1028 (2e−14) | 35 (62) |

| 7 | GSEF_0614 | 492 | 22.7 | Terminase, small subunit | ORF009, S. aureus SaPI1028 (6e−54) | 64 (83) |

| 8 | GSEF_0613 | 999 | 39 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein MW0756, S. aureus MW2 (4e−60) | 37 (64) |

| 9 | GSEF_3000 | 582 | 22.3 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein MW0757, S. aureus MW2 (5e−23) | 50 (71) |

| 10 | GSEF_0163 | 801 | 31.9 | Enterotoxin C3 | Enterotoxin type C3, S. aureus Mu50 (9e−141) | 95 (97) |

| 11 | GSEF_0162 | 1,423 | 67 | Transposase | Putative transposase, S. epidermidis ATCC 12228 (0.0) | 97 (99) |

| 12 | GSEF_0161 | 723 | 28.8 | Enterotoxin L | Extracellular enterotoxin L, S. aureus Mu50 (1e−122) | 97 (98) |

| 13 | GSEF_0160 | 1,014 | 40.4 | Transposase | ISSep-1-like transposase, S. aureus (0.0) | 98 (98) |

| 14 | GSEF_0159 | 60 | 2.4 | Hypothetical protein | Hypothetical protein, S. epidermidis (0.061) | 90 (95) |

| 15 | GSEF_0158 | 309 | 18.8 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein, S. aureus USA300 (1e−18) | 52 (68) |

| 16 | GSEF_0157 | 261 | 22.7 | Terminase, small subunit | Terminase small subunit, S. aureus MRSA252 (5e−23) | 69 (82) |

| 17 | GSEF_0156 | 438 | 17.7 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein SAR1890, S. aureus MRSA252 (6e−31) | 56 (75) |

| 18 | GSEF_0155 | 747 | 64.3 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein SAR1895, S. aureus MRSA252 (3e−46) | 49 (68) |

| 19 | GSEF_0154 | 429 | 17.8 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein SAR1894, S. aureus MRSA252 (3e−19) | 38 (64) |

| 20 | GSEF_0153 | 1,527 | 64.3 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein SAR1895, S. aureus MRSA252 (1e−77) | 46 (66) |

| 21 | GSEF_0152 | 300 | 11.8 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein SAR1896, S. aureus MRSA252 (1e−17) | 47 (72) |

| 22 | GSEF_0151 | 426 | 17.04 | Hypothetical protein | Conserved hypothetical protein, S. epidermidis W23144 (1e−32) | 48 (69) |

| 23 | GSEF_0150 | 339 | 13.56 | Hypothetical protein | Conserved hypothetical protein, S. epidermidis W23144 (2e−30) | 75 (84) |

| 24 | GSEF_0149 | 405 | 16.2 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Conserved hypothetical protein, S. epidermidis W23144 (1e−38) | 96 (99) |

| 25 | GSEF_0148 | 168 | 6.72 | Unnamed protein product | Hypothetical protein SH1800, S. haemolyticus JCSC1435 (5e−20) | 87 (94) |

| 26 | GSEF_0147 | 141 | 5.64 | Unnamed protein product | Hypothetical protein SH1800, S. haemolyticus JCSC1435 (2e−13) | 88 (95) |

| 27 | GSEF_0146 | 354 | 18.8 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein, S. aureus USA300 (6e−13) | 62 (75) |

| 28 | GSEF_0145 | 468 | 19.1 | Hypothetical S. aureus protein | Hypothetical protein MW0372, S. aureus MW2 (1e−23) | 46 (60) |

| 29 | GSEF_0144 | 738 | 29.5 | Amidohydrolase | 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid hydrolase, S. haemolyticus (9e−07) | 45 (64) |

The SePI is encoded on two separate contigs: (i) GSEF_144_163 (contig 00004) and (ii) GSEF_0613-620 (contig 00011). The sequence (GSEF_3000) linking contigs 00004 and 00011 was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

ORFs not in consecutive numerical order were manually reannotated after initial automated annotation.

Table 2.

Genome organization of S. epidermidis FRI909 temperate bacteriophage ϕ909a

| ORF | Locus ID | Size (bp) | Predicted function | Most significant database match (E value) | % aa identity (similarity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GSEF_0256 | 1,125 | Integrase | Bacillus cereus E33L, integrase (9e−66) | 39 (58) |

| 2 | GSEF_0255 | 372 | Unknown | Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSC5402 integrase, MCCL_0938 (8e−86) | 43 (65) |

| 3 | GSEF_0254 | 351 | Repressor | S. aureus phage 80α, CI-like repressor (3e−22) | 67 (85) |

| 4 | GSEF_0253 | 237 | Repressor | S. aureus phage ϕPVL108, cro-like repressor (5e−29) | 83 (88) |

| 5 | GSEF_0252 | 279 | Unknown | S. epidermidis M23864:W1 unknown, HMPREF0793_2053 (1e−33) | 72 (89) |

| 6 | GSEF_0251 | 156 | Hypothetical | No significant match | 0 |

| 7 | GSEF_0250 | 204 | Hypothetical | No significant match | 0 |

| 8 | GSEF_0249 | 165 | Hypothetical | No significant match | 0 |

| 9 | GSEF_0248 | 210 | Unknown | S. aureus phage 96, ORF086 (2.4e−20) | 68 (80) |

| 10 | GSEF_0247 | 192 | Membrane protein | S. epidermidis W23144, unknown, HMPREF0791_1646 (5e−12) | 55 (77) |

| 11 | GSEF_0246 | 267 | Unknown | S. aureus A9635, unknown, SALG_01528 (2e−30) | 49 (70) |

| 12 | GSEF_0245 | 396 | ssDNA binding proteinb | S. aureus phage 80α, ssDNA binding protein (8e−32) | 57 (79) |

| 13 | GSEF_0244 | 903 | DNA replication | S. aureus USA300, DnaD DNA replication protein, HMPREF0776_0149 (3e−53) | 43 (58) |

| 14 | GSEF_0243 | 312 | Unknown | S. aureus phage 80a, gp26 (0.52) | 30 (50) |

| 15 | GSEF_0242 | 300 | Membrane protein | S. epidermidis W23144, unknown, HMPREF0791_1646 (5e−12) | 55 (77) |

| 16 | GSEF_0241 | 225 | Unknown | Clostridium botulinum strain E3, acetyltransferase, CLH_0023 (7.9) | 37 (56) |

| 17 | GSEF_0240 | 252 | Positive control factor | Bacillus sp. positive control sigma-like factor (1.3e−7) | 42 (57) |

| 18 | GSEF_1849 | 144 | RNA polymerase | Bacillus pumilus ATCC 7061, RNA polymerase sigma factor (6e−19) | 33 (53) |

| 19 | GSEF_1848 | 393 | Unknown | Nitrobacter winogradskyi Nb-255, dehydrogenase, Nwi_0422 (2.5) | 26 (39) |

| 20 | GSEF_1847 | 357 | HNH endonuclease | S. aureus phage ϕSLT, ϕSLTp37 (2e−21) | 57 (68) |

| 21 | GSEF_1846 | 402 | Unknown | Bacillus anthracis conserved hypothetical protein (3e−16) | 53 (79) |

| 22 | GSEF_1845 | 1,716 | Terminase | B. anthracis prophage LambdaBa01, terminase large subunit (3e−144) | 61 (78) |

| 23 | GSEF_1844 | 1,227 | Portal protein | Phage portal protein, Clostridium botulinum (6e−80) | 39 (62) |

| 24 | GSEF_1843 | 1,251 | Major capsid protein | Phage protein, Clostridium perfringens (2e−61) | 33 (53) |

| 25 | GSEF_1842 | 288 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein SA1771, S. aureus phage ϕN315 (2e−08) | 32 (59) |

| 26 | GSEF_1841 | 339 | DNA packaging | QlrG family phage protein (6e−07) | 40 (61) |

| 27 | GSEF_1840 | 1,557 | Unknown | S. epidermidis RP62a, unknown, SERP2279 (7.4e−273) | 97 (98) |

| 28 | GSEF_1839 | 414 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein SA1770, S. aureus phage ϕN315 (2e−16) | 37 (59) |

| 29 | GSEF_1838 | 660 | Tail protein, structural | Major tail protein, S. aureus phage ϕSLT (5e−30) | 35 (61) |

| 30 | GSEF_1837 | 351 | Unknown | Bacillus subtilis, conserved hypothetical protein (4e−04) | 33 (57) |

| 31 | GSEF_1836 | 1,509 | Glycosyl transferase | S. epidermidis ATCC 12228, SE2243, lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis protein (2.5e−265) | 97 (99) |

| 32 | GSEF_1835 | 4,491 | Tail tape length measure | Tail tape length measure protein, S. aureus USA300_TCH1516 (0.0) | 41 (59) |

| 33 | GSEF_1834 | 825 | Putative holin | Holin-like protein, S. aureus phage ϕ12 (8e−47) | 37 (54) |

| 34 | GSEF_1833 | 1,179 | Structural protein | Minor structural protein, Listeria monocytogenes phage (3e−74) | 40 (62) |

| 35 | GSEF_1832 | 597 | Conserved phage protein | S. aureus phage 187, ORF019 (7e−60) | 53 (64) |

| 36 | GSEF_1831 | 1,017 | Acylhydrolase, putative structural component | S. aureus phage 187, putative protein (3e−93) | 55 (71) |

| 37 | GSEF_1830 | 1,278 | Minor capsid protein | S. aureus phage 187, ORF006 (1e−21) | 49 (70) |

| 38 | GSEF_1829 | 177 | Putative membrane protein | S. epidermidis ATCC 12228, SE2234 (2.9e−24) | 100 (100) |

| 39 | GSEF_1828 | 246 | Holin | S. epidermidis phage lysis holin (1e−13) | 50 (72) |

| 40 | GSEF_1827 | 918 | Amidase | Bacillus sp., N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (8e−24) | 37 (54) |

| 41 | GSEF_1826 | 774 | Unknown | Staphylococcus phage 52A, ORF013 (3e−25) | 41 (58) |

| 42 | GSEF_1825 | 2,859 | Phage infection protein | S. epidermidis RP62a, SERP2262 (0e−0) | 99 (99) |

| 43 | GSEF_1824 | 331 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein SAB1174, S. aureus RF122 (1e−56) | 77 (90) |

The phage is encoded on two separate contigs: (i) GSEF_1824 to GSEF_1849 (contig 00040) and (i) GSEF_0240 to GSEF_0256 (contig 00006). The sequence linking contigs 00040 and 00006 was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

Identification of a SEC-encoding genetic fragment.

Staphylococcus epidermidis FRI909 was originally isolated from a human source and was identified as an enterotoxin C-producing CoNS (22). The presence of a sec gene in FRI909 was confirmed by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing with primers corresponding to sec3 (17). To identify the chromosomal region containing sec, FRI909 genomic DNA was digested with HindIII and was analyzed by Southern blotting using an alkaline phosphatase-labeled 500-nucleotide (nt) internal sec3 fragment (17). The sequence of the 10-kb genomic restriction fragment containing the sec gene was determined by sequencing a series of deletion products generated using the Erase-A-Base system (Promega, Madison, WI). The remaining sequence of the SePI element was determined after genome sequencing of FRI909 by 454 FLX pyrosequencing.

PCR screen of S. epidermidis clinical isolates for SePI.

S. epidermidis clinical isolates recovered in cases of bacteremia were obtained from hospitals in the Kaleida Health System of Western New York. Two hundred isolates were from monomicrobial S. epidermidis infections. Six isolates were from mixed S. epidermidis-S. aureus infections. The isolates were screened for the presence of a SePI-like island by multiplex PCR amplification of nine S. aureus enterotoxin genes (including sec3 and sell) and three genes within the core of the SePI element: (i) the SePI integrase (GSEF_0619), (ii) a SaPI-like packaging protein (GSEF_0617), and (iii) a hypothetical SaPI protein (GSEF_0613) homologous to MW0756, which is found within the SaPImw3 of MW2.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

Bacteria were grown overnight in BHI and were diluted 1:100 in fresh medium. Culture aliquots were removed at specified time points and were added to RNAProtect Bacteria reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was isolated from samples by bead-beating cultures in lysing matrix B tubes (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) with Trizol (Invitrogen), followed by chloroform extraction from the aqueous phase and precipitation in isopropanol. Extracted RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX) in order to remove any contaminating genomic DNA and was purified on RNeasy columns (Qiagen). Complete removal of contaminating DNA was confirmed by PCR. Clean RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically and was subsequently used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using the MyiQ SYBR green detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). S. aureus N315 was used as a positive control for SEC3 production. For each time point, fold changes in gene expression were calculated relative to the expression of the internal control genes for 16S rRNA and DNA gyrase A.

Generation of an anti-SEC3 antibody.

To generate anti-SEC3 sera, SEC3 was purified from cultures by using preparative isoelectric focusing as described previously (10). New Zealand White rabbits (Simonsen Laboratories, Gilroy, CA) were immunized biweekly with SEC3. One week after the fourth boost, sera were harvested and pooled.

Western blotting.

Bacterial cultures were grown as for the RT-PCR experiments described above. Ten-milliliter samples from cultures were pelleted (16,000 × g, 10 min) at the time points specified in Fig. 3C. Supernatants were sterilized with 0.45-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and were concentrated to a 100-μl volume with Amicon Ultra-15 concentration units (Millipore) by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min. Samples were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (10% polyacrylamide gels), and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After being blocked with 2% skim milk in TTBS (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), membranes were incubated with anti-SEC3 (see above) or anti-SEL sera, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare). Proteins were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit according to the manufacturer's directions (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

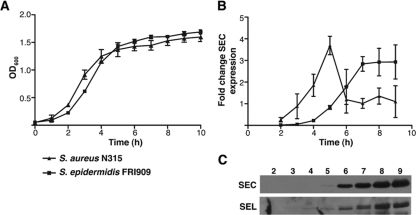

Fig. 3.

Analysis of SEC3 expression by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. (A) Growth curves measured by the OD600 for S. aureus N315 and S. epidermidis FRI909. (B) Expression of enterotoxin SEC3 was evaluated by qRT-PCR using gyrB as a standard and the SEC3-producing strain S. aureus N315 as a positive control. (C) Similar levels of expression from the two strains were observed by Western immunoblotting. Lane labels indicate time (h).

Bacteriophage induction, transduction, and DNA extraction.

Bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.45 and were induced by the addition of mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Cultures were grown aerobically at 37°C for 16 h in order for complete lysis to occur. The resultant lysates were used for electron microscopy. Lysates were filter sterilized (with 0.45-μm-pore-size filters) and were used to transduce recipient strain S. epidermidis HER1292 as described in the literature (25). Phage DNA was extracted by standard methods (1). Briefly, purified phage particles were treated with DNase to remove any contaminating genomic DNA, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation of phage DNA. PCR to test for the presence of SePI-1 in this DNA was performed using primers for gyrA (to confirm the absence of genomic DNA), the portal gene (phage), and SEC3.

Electron microscopy.

Bacteriophages were pelleted by centrifugation at 70,000 × g for 1 h, washed twice with ammonium acetate solution (100 mM), and resuspended in 4 mM CaCl2–1 mM MgCl2. The sample was adsorbed onto a carbon grid and was negatively stained using 2% sodium phosphotungstate (pH 7.0). The sample was air dried and examined at a magnification of ×85,000 on a JEOL 100 CX2 transmission electron microscope.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The results of this Whole Genome Shotgun project have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession number AENR00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, AENR01000000. Nucleotide sequences and annotation for the S. epidermidis FRI909 SePI element and the φ909 bacteriophage are included in this accession.

RESULTS

Taxonomic placement of strain FRI909.

Because S. epidermidis FRI909 was isolated from a human source (22) and previous studies have raised concerns about the species identity of clinical CoNS isolates based on phenotypic characteristics (16, 24), we confirmed the genotype of S. epidermidis strain FRI909 by PCR-RFLP of gap, sequencing of tuf, and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (21).

Comparison of the S. epidermidis FRI909 genome to those of sequenced strains.

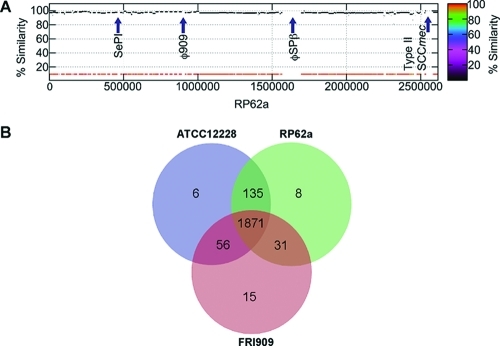

Contigs assembled from genome sequencing were annotated using the IGS annotation engine. The alignment of the FRI909 draft genome sequence with the genome sequence of S. epidermidis RP62a and the locations of SePI, φ909, φSPβ, and the type II staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) are indicated in Fig. 1A. SePI and φ909 are unique to S. epidermidis FRI909. φSPβ and the type II SCCmec are unique to S. epidermidis RP62a. Families of orthologous gene groups were identified by comparison to the two completely sequenced S. epidermidis genomes, those of ATCC 12228 and RP62a. As shown in the Venn diagram in Fig. 1B, FRI909 contains 15 unique orthologous groups (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) not present in the other two genomes. Several hypothetical proteins were identified in these groups, along with clusters of mobilization proteins that appear to be chromosomal remnants of a plasmid that may have integrated into the genome and undergone rearrangements. Interestingly, some of these mobilization proteins also flank a putative CRISPR locus identified in the genome. The only other significant unique group consists of the genes present on SePI-1, corresponding to the enterotoxins and SaPI-like elements identified on this pathogenicity island. The bacteriophage present in S. epidermidis FRI909 is clustered with orthologous phage genes from the bacteriophage present in S. epidermidis RP62a.

Fig. 1.

(A) Genome alignment and ortholog comparison of S. epidermidis FRI909 with S. epidermidis RP62a and ATCC 12228, whose genomes have been completely sequenced. (A) Alignment of the S. epidermidis FRI909 and RP62a genomes shows the positions of FRI909 SePI and φ909 relative to each other and to RP62a φSPβ and type II SCCmec. The SePI is inserted into the tmRNA region of FRI909. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of orthologous groups in each genome, as well as the common and unique clusters identified.

Sequence analysis and identification of a genomic island.

Multiplex PCR was used to screen the FRI909 genome for nine staphylococcal superantigens (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The strain tested positive only for sec and sell (data not shown). Sequencing and additional PCR with primers specific to sec3 and sell confirmed the presence of these two toxins. Because these two toxin genes are typically associated with mobile pathogenicity islands flanked by att sites in S. aureus, the sequences of regions flanking the toxin genes were determined. We identified a novel genomic sequence of about 20.5 kb inserted at the transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) gene of S. epidermidis FRI909, just downstream of the SsrA binding protein (identical in sequence to the corresponding region of the sequenced genome of S. epidermidis RP62a; SERP0451 is the locus identification [ID] for ssrA, and SERP_SetmRNA1 is the locus ID for tmRNA, in RP62a, while GSEF_0621 is the locus ID for ssrA in FRI909). The tmRNA region is associated with the insertion of foreign genetic elements in the genomes of several bacteria, and the insertion of the pathogenicity island μSaα3mw (called SaPImw2 by Novick et al. [27]) in S. aureus MW2 occurs in an identical region (2). As described below, the presence of multiple transposases and repeat sequences, along with the mixed S. aureus and S. epidermidis sequence in this region, suggests that more than one insertion and recombination event have led to the formation of this SePI. Considering the gene organization of this composite genomic island, we propose that it comprises two distinct regions, as shown in Fig. 2A. The first of these is SePI-1, a classical pathogenicity island that shows significant homology to the enterotoxin-bearing SaPIs, and the second is SeCI-1 (S. epidermidis chromosomal insertion 1), an IS1272-like region flanked by 73-bp direct repeats, which contains multiple transposases and several exported S. aureus proteins.

Fig. 2.

Sequence and ORF map of the composite SePI and comparison with sequenced SaPIs. (A) The 20.5-kb mobile genetic element is inserted into the tmRNA region of S. epidermidis FRI909, between the SsrA-binding protein (GSEF_0621) and a Na+-transporting ATPase (GSEF_0143). This island appears to be the product of two independent insertional events, one resulting in the insertion of SePI-1 (flanked by 14-bp attL and attR direct-repeat sequences) and the other in a transposon-mediated insertion. The second insertion, SeCI-1, is flanked by 73-bp direct-repeat sequences and comprises several S. aureus proteins not found in sequenced S. epidermidis genomes. A list of ORFs and predicted functions is presented in Table 1. (B) For comparison to the composite SePI, ORFs in SaPImw2, SaPIn315, and SaPIbov1, which have been functionally characterized (31, 32), are shown.

Chromosomal integration site and comparison to known SaPIs.

SePI-1 is a 9.6-kb region flanked by direct repeats that encompasses the two superantigen genes. The 14-bp direct repeats (DR1) defining the ends of SePI-1 (Fig. 2A) are identical to the att sequences of SaPImw2 in S. aureus MW2 and to those of three other known SaPIs (2, 27). The map of SePI-1 includes 11 open reading frames (ORFs) identified on the basis of homology to known sequences (Fig. 2A; Table 1). The putative SEC3 gene identified bears 95% identity to previously sequenced SEC3 genes from S. aureus. It differs at 12 amino acid residues from the SEC3 gene of S. aureus Mu3. However, none of these residues lie in the Zn-binding or T-cell receptor binding domains, suggesting that functional differences are unlikely. The crystal structure of FRI909 SEC3 has also been described previously (4). The SElL gene is 97% identical to known S. aureus SElL genes, and its product differs at 6 amino acid residues from the S. aureus gene product.

An integrase at the left-hand junction of this putative pathogenicity island is 92% identical to the integrase in genomic island SaPImw2, present in S. aureus strain MW2 (2). Although SePI-1 ORF3 occurs in a context and at a location similar to those of the regulatory stl gene in SaPIs, it bears no sequence homology to stl. Other genes within the island encode a terminase and four of the packaging proteins associated with sequenced SaPIs, as shown in Table 1. For purposes of comparison with the SePI ORFs, the ORFs of sequenced SaPIs are shown in Fig. 2B.

The presence of another set of direct-repeat sequences of 73 bp (DR2) flanking transposase elements and several exported proteins from S. aureus, suggests the occurrence of at least one other insertion event in this region of the FRI909 chromosome (Fig. 2A). The element flanked by DR2, termed SeCI-1, is similar to IS1272, which is also flanked by direct repeats and contains transposase genes, but bears no further similarity to known pathogenicity-associated or other genomic islands. Together, SePI-1 and SeCI-1 form the composite genomic island seen in strain FRI909.

Searches of the two sequenced S. epidermidis genomes reveal that strain ATCC 12228 contains 19 copies of the 73-bp repeat flanking SeCI-1 and that 1 of these is at the same genomic location (upstream of Na+-transporting ATP synthase) as that in FRI909. The short 14-bp direct repeat is also found in ATCC 12228, at the same genomic location as that in FRI909 (downstream of the SsrA-binding protein).

Expression of enterotoxins SEC3 and SElL.

Although previous studies have identified enterotoxin genes in CoNS (5, 7), the potential regulatory mechanisms and expression of these genes in non-S. aureus strains have not been examined. Expression of the SEC3 gene from this region was confirmed by Northern blotting (data not shown), and qRT-PCR was performed to identify possible growth-dependent regulation (Fig. 3B). SEC3 expression appears to increase significantly toward late-log phase and early-stationary phase (Fig. 3C), slightly later than the peak of expression observed with a control S. aureus strain, N315. Similar results were obtained with SElL (data not shown), and transcriptional expression was corroborated by translational studies with Western immunoblotting for both enterotoxins (Fig. 3C). While the regulation and significance of this pattern of toxin expression have yet to be elucidated, the virulence potential of this genomic island is evident in the expression of the two toxin genes present.

Mobilization.

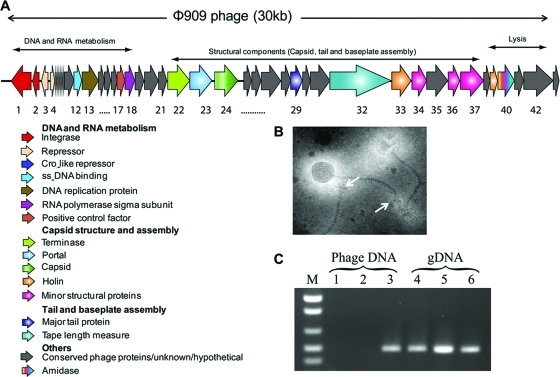

Both transduction and conjugation are known to function in the horizontal transmission of accessory genes in S. aureus. Since superantigen toxins and SaPIs are most frequently mobilized by bacteriophage, there is a strong possibility that interspecies transfer also occurs by similar mechanisms. We tested the phage-related excision and packaging of SePI-1 by mitomycin C treatment. A previously unknown S. epidermidis bacteriophage was identified in the culture lysate. Purified phage particles studied by transmission electron microscopy revealed symmetrical icosahedral heads (diameter, approximately 60 nm), flexible banded tails, and end plates (Fig. 4B). All induced phage particles were identical in size, suggesting that even if packaging of SePI-1 occurs in conjunction with this temperate phage, the small phage heads characteristically observed in SaPI transduction (30) are unlikely to be formed. The insertion of SeCI-1 interrupts the SePI-1 sequence with an S. epidermidis transposase, disrupting the SaPI ORFs implicated in the formation of smaller infectious SaPI phage particles (30, 32). This does not rule out the possibility that SePI-1 may be excised and packaged at a lower frequency in normal phage particles. PCR was performed on purified phage DNA using primers designed to amplify both the SePI-1 SEC3 gene and the phage-specific portal gene as a positive control. The absence of contaminating genomic DNA was confirmed by using gyrA as a negative control. Phage DNA gave a 600-bp product only for the portal gene, suggesting that SePI-1 is not packaged as part of the phage DNA (Fig. 4C). PCR to test SePI-1 excision and circularization, and Southern blotting to check for SePI-1-specific bands upon phage excision, gave negative results (data not shown), suggesting that SePI-1 is unlikely to be mobilized by a temperate phage in the SaPI-like excision-replication-packaging mechanism (32). Although we also identified plasmids in S. epidermidis strain FRI909, conjugative transfer of genomic elements to recipient strains RP62a and HER1292 was not seen at any discernible frequency (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Sequence and ORF analysis of the temperate bacteriophage φ909 in S. epidermidis FRI909. (A) The φ909 bacteriophage insertion is found immediately downstream of the FemC/glutamine synthetase gene (SERP0876 in RP62a; GSEF_0257 in FRI909), a site distinct from the composite genomic island containing SePI-1. The genome shows conserved regions corresponding to those seen in S. aureus phages. (B) Ultrastructure of the bacteriophage showing intact phage particles. Transmission electron microscopy reveals isometric heads (diameter, 60 nm) with long, banded tails and end plates. Arrows mark end plates on tails. (C) PCR amplification of toxin genes from phage DNA and bacterial genomic DNA (gDNA). Lanes 1 and 4, gyrA; lanes 2 and 5, the SEC3 gene; lanes 3 and 6, porF; lane M, marker.

Phage genome.

Since the 9.6-kb SePI-1 element is interrupted by a transposon not typically seen in SaPI sequences, it is possible that this genomic island was mobilized by a bacteriophage from S. aureus into S. epidermidis FRI909 but can no longer be mobilized due to the transposase interruption. The complete genome sequence of the endogenous prophage in S. epidermidis FRI909 was compared to those of known S. epidermidis bacteriophage and SaPI-associated temperate phages from S. aureus. Overall, this previously unidentified phage bears greater sequence homology to S. aureus phages than to the two phages in sequenced S. epidermidis genomes (9), as evidenced by the database matches in Table 2. The 30,124-bp genome contains 29 putative ORFs and has an AT-rich genome (GC content, 28%), which is comparable to other staphylococcal phage genomes, both in S. aureus and in S. epidermidis. A complete list of genes and their closest database matches appears in Table 2. The phage genome appears modular, organized as genes involved in lysis, lysogeny, and DNA replication and modification, followed by structural genes for capsid formation and assembly and for head and tail morphogenesis (Fig. 4A). Despite the similarity of the FRI909 phage to S. aureus temperate phages, its genome sequence indicates that it is not one of the many temperate phages with a well-defined relationship to the SaPIs.

Screening for SePI-like elements in S. epidermidis clinical isolates associated with bacteremia.

To determine if acquisition of the SePI element by FRI909 was an isolated or rare event, we screened more than 200 S. epidermidis bacteremia isolates for the presence of nine S. aureus enterotoxins as well as the SePI integrase (GSEF_0619), a SaPI-like packaging protein (GSEF_0617), and a hypothetical SaPI protein (GSEF_0613) homologous to MW0756, which is found within SaPImw3 of MW2 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Two hundred of these isolates were from patients with monomicrobial S. epidermidis infections. Six were from patients with mixed S. epidermidis-S. aureus infections, an environment likely to promote the transfer of pathogenicity islands between these two species. None of the isolates contained enterotoxins, the SePI integrase, or the SaPI-like packaging proteins. The absence of sec3 and sell in the isolates suggests that the SePI element we describe is unique to FRI909. The absence of the SePI integrase and SaPI-like packaging proteins in the bacteremia isolates suggests that SePI-like elements that do not encode these enterotoxins occur rarely in S. epidermidis.

DISCUSSION

Early reports of the presence of superantigen toxins in CoNS have been based primarily on phenotypic tests for coagulase production and subsequent identification of the toxin genes (5). Later studies contradicting these results suggest that coagulase production is not an adequate means of classification for the staphylococci (16). More-recent reports of enterotoxins and other superantigens in CoNS have also based the classification of clinical isolates predominantly on phenotypic criteria rather than on genotypic characterization and MLST. Since toxin-containing coagulase-negative S. aureus strains have been reported in the literature (24), and it is known that clinical isolates of bacteria tend to show greater phenotypic variability than laboratory strains, MLST or another method of genotypic characterization is of great importance to any studies of toxin gene distribution in staphylococcal species.

Although previous studies have identified superantigen genes in CoNS, their genomic location in other species has not been analyzed so far. Our results suggest that they can occur in more diverse genetic contexts than just the specialized pathogenicity islands exclusive to S. aureus. The SaPIs, as described thus far, all contain specific ORFs to hijack temperate phage function for the structural proteins required for SaPI packaging. They do not encode functions beyond these 20 or so ORFs, att sequences, and toxin genes. Little is known about the evolutionary processes that have resulted in the current composition of SaPIs, and they are usually regarded as highly specialized temperate phages. So far, there have been no reports of superantigen gene mobilization by means other than transduction or by mobile elements other than phages.

Compared to the specialized transfer mechanism of SaPIs, other virulence-associated accessory genes in staphylococci and the related enterococci are transmitted by genomic elements that are more variable, both in their structures and in their sources. Antibiotic resistance genes, for example, are known to be mobilized between S. aureus strains by chromosomal elements, from S. epidermidis to S. aureus by conjugative plasmids, and from enterococci to S. aureus by conjugative processes (12, 15, 34). Vancomycin resistance elements (VRE) are mobilized from Enterococcus spp. to S. aureus by conjugative plasmids (34). Interestingly, although the VRE in Enterococcus spp. bear the hallmarks of a classical excision-replication-integration pathway (att sequences, integrase, terminase), none of these features are involved in the process of mobilization into S. aureus (28). The conjugative process that transfers these resistance genes into the S. aureus genome operates exclusively between enterococci and S. aureus.

Similarly, the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) reported in the S. aureus USA300 genome is actually more prevalent in S. epidermidis strains and is mobilized only from S. epidermidis to S. aureus, not between S. aureus strains (11). Like the VRE, this 57-kb composite island is interspersed with direct and inverted repeats and is a result of the insertion of three separate pieces of foreign DNA into the same region of the S. epidermidis genome.

Further, S. aureus itself is known to contain large nonmobile genomic islands encoding enterotoxin-like genes. Even though these are widespread among S. aureus strains, they are typically not taken into account in discussions of the mobilization of superantigen genes, since their horizontal transfer has not been demonstrated.

The stability and transmissibility of the accessory gene pool of a species may be significantly impacted by core genomic factors. Natural competence in many species is a function of, and is regulated by, the core genome. A recent report by Marraffini and Sontheimer also shows that sequence-directed immunity against bacteriophages can reduce conjugative gene acquisition in S. epidermidis (23). Other research has demonstrated that SaPI transduction to S. epidermidis occurs much less frequently than to L. monocytogenes (3).

Our results are the first conclusive evidence of the stable horizontal acquisition of virulence-associated mobile elements in an S. epidermidis genome. Although we have screened more than 200 other clinical S. epidermidis isolates, we have found no evidence of enterotoxins or SePI-like genomic elements in these other strains. In this context, the multiple insertions of chromosomal pathogenicity islands, truncated plasmids, transposases, and bacteriophage in S. epidermidis FRI909 are especially significant, and a closer examination of the whole genome may provide insights into the evolutionary pressures and core genomic components that have enabled the stabilization of the staphylococcal pathogenicity island SePI-1 in this genome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the J. R. Oishei Foundation (S.R.G.), the NIH (P20RR15587, P20RR016454, and U54AI57141) (G.A.B.), and the USDA NRI and Idaho Agricultural Experimental Station (G.A.B.).

We thank Diane Dryja (Western New York Kaleida Health) for collection of the S. epidermidis bacteremia isolates, Kiyonobu Homma (University at Buffalo) for valuable advice regarding real-time RT-PCR methods, Ted Szczesny (University at Buffalo) for assistance with electron microscopy, and Janet Waterhouse for assistance with SePI sequencing.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 11 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ausubel F. M., et al. 2007. Current protocols in molecular biology, 5th ed. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baba T., et al. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen J., Novick R. P. 2009. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science 323:139–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chi Y. I., et al. 2002. Zinc-mediated dimerization and its effect on activity and conformation of staphylococcal enterotoxin type C. J. Biol. Chem. 277:22839–22846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crass B. A., Bergdoll M. S. 1986. Involvement of coagulase-negative staphylococci in toxic shock syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23:43–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crass B. A., Bergdoll M. S. 1986. Involvement of staphylococcal enterotoxins in nonmenstrual toxic shock syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23:1138–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cunha Mde L., Rugolo L. M., Lopes C. A. 2006. Study of virulence factors in coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from newborns. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 101:661–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Curtin J. J., Donlan R. M. 2006. Using bacteriophages to reduce formation of catheter-associated biofilms by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1268–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daniel A., Bonnen P. E., Fischetti V. A. 2007. First complete genome sequence of two Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 189:2086–2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deringer J. R., Ely R. J., Stauffacher C. V., Bohach G. A. 1996. Subtype-specific interactions of type C staphylococcal enterotoxins with the T-cell receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 22:523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diep B. A., et al. 2006. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367:731–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forbes B. A., Schaberg D. R. 1983. Transfer of resistance plasmids from Staphylococcus epidermidis to Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for conjugative exchange of resistance. J. Bacteriol. 153:627–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gal-Mor O., Finlay B. B. 2006. Pathogenicity islands: a molecular toolbox for bacterial virulence. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1707–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gill S. R., et al. 2005. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J. Bacteriol. 187:2426–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurdle J. G., O'Neill A. J., Mody L., Chopra I., Bradley S. F. 2005. In vivo transfer of high-level mupirocin resistance from Staphylococcus epidermidis to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with failure of mupirocin prophylaxis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:1166–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kreiswirth B. N., Schlievert P. M., Novick R. P. 1987. Evaluation of coagulase-negative staphylococci for ability to produce toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2028–2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuroda M., et al. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuroda M., et al. 2005. Whole genome sequence of Staphylococcus saprophyticus reveals the pathogenesis of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:13272–13277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li L., Stoeckert C. J., Jr., Roos D. S. 2003. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13:2178–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindsay J. A., Holden M. T. 2006. Understanding the rise of the superbug: investigation of the evolution and genomic variation of Staphylococcus aureus. Funct. Integr. Genomics 6:186–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a. Madhusoodanan J., Seo K. S., Park J. Y., Gill A. L., Waterhouse J., Remortel B., Bohach G., Gill S. R. 2007. Abstr. 107th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. B-420. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maiden M. C., et al. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3140–3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marr J. C., et al. 1993. Characterization of novel type C staphylococcal enterotoxins: biological and evolutionary implications. Infect. Immun. 61:4254–4262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J. 2008. CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322:1843–1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matthews K. R., Roberson J., Gillespie B. E., Luther D. A., Oliver S. P. 1997. Identification and differentiation of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction. J. Food Prot. 60:686–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novick R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Novick R. P. 2003. Mobile genetic elements and bacterial toxinoses: the superantigen-encoding pathogenicity islands of Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid 49:93–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Novick R. P., Subedi A. 2007. The SaPIs: mobile pathogenicity islands of Staphylococcus. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 93:42–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shankar N., Baghdayan A. S., Gilmore M. S. 2002. Modulation of virulence within a pathogenicity island in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Nature 417:746–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takeuchi F., et al. 2005. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus haemolyticus uncovers the extreme plasticity of its genome and the evolution of human-colonizing staphylococcal species. J. Bacteriol. 187:7292–7308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tallent S. M., Langston T. B., Moran R. G., Christie G. E. 2007. Transducing particles of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island SaPI1 are comprised of helper phage-encoded proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189:7520–7524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ubeda C., Barry P., Penades J. R., Novick R. P. 2007. A pathogenicity island replicon in Staphylococcus aureus replicates as an unstable plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:14182–14188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ubeda C., et al. 2008. SaPI mutations affecting replication and transfer and enabling autonomous replication in the absence of helper phage. Mol. Microbiol. 67:493–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Valle J., Vadillo S., Piriz S., Gomez-Lucia E. 1991. Toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) production by staphylococci isolated from goats and presence of specific antibodies to TSST-1 in serum and milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:889–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weigel L. M., et al. 2003. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 302:1569–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.