Abstract

The bacterial sugar:phosphotransferase system (PTS) delivers phosphoryl groups via proteins EI and HPr to the EII sugar transporters. The antitermination protein LicT controls β-glucoside utilization in Bacillus subtilis and belongs to a family of bacterial transcriptional regulators that are antagonistically controlled by PTS-catalyzed phosphorylations at two homologous PTS regulation domains (PRDs). LicT is inhibited by phosphorylation of PRD1, which is mediated by the β-glucoside transporter EIIBgl. Phosphorylation of PRD2 is catalyzed by HPr and stimulates LicT activity. Here, we report that LicT, when artificially expressed in the nonrelated bacterium Escherichia coli, is likewise phosphorylated at both PRDs, but the phosphoryl group donors differ. Surprisingly, E. coli HPr phosphorylates PRD1 rather than PRD2, while the stimulatory phosphorylation of PRD2 is carried out by the HPr homolog NPr. This demonstrates that subtle differences in the interaction surface of HPr can switch its affinities toward the PRDs. NPr transfers phosphoryl groups from EINtr to EIIANtr. Together these proteins form the paralogous PTSNtr, which controls the activity of K+ transporters in response to unknown signals. This is achieved by binding of dephosphorylated EIIANtr to other proteins. We generated LicT mutants that were controlled either negatively by HPr or positively by NPr and were suitable bio-bricks, in order to monitor or to couple gene expression to the phosphorylation states of these two proteins. With the aid of these tools, we identified the stringent starvation protein SspA as a regulator of EIIANtr phosphorylation, indicating that PTSNtr represents a stress-related system in E. coli.

INTRODUCTION

In many bacteria the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system (transport PTS) represents the major carbohydrate uptake system (5, 48). The transport PTS is also a global signaling system that orchestrates carbohydrate utilization and coordinates it with other processes (15). It is composed of the two general phosphotransferases enzyme I (EI) and histidine protein (HPr), which deliver phosphoryl groups from phosphoenol-pyruvate to the EII enzymes (EIIs). The EIIs are carbohydrate-specific transport proteins and consist of three domains which may be fused or encoded separately as distinct proteins. The EIIC domain is membrane bound and forms the sugar translocation channel, while the EIIA and EIIB domains are cytoplasmic and sequentially transfer phosphoryl groups from HPr to the substrate during transport. The phosphorylation state of the PTS proteins is modulated in response to the available carbon source (8, 28). This state is sensed and used to regulate other protein activities, either through protein binding or by transfer of phosphoryl groups. Paradigmatic examples include the EIIAGlc protein of the glucose transporter, which controls carbon catabolite repression (CCR) and inducer exclusion in Enterobacteriaceae, and HPr, which carries out the analogous regulation in Firmicutes (for reviews, see references 14 and 24).

In addition to the transport PTS, many Proteobacteria possess the paralogous PTSNtr (for review, see reference 45). In analogy to the canonical PTS, the PTSNtr constitutes a phosphorylation cascade working in the direction PEP→EINtr→NPr→EIIANtr (43, 49, 50, 72). Associated EIIBC domains are lacking and, accordingly, PTSNtr is believed to exclusively serve regulatory functions. PTSNtr affects numerous processes, such as nitrogen and carbon assimilation and virulence (17, 49, 66), but mechanistic knowledge is often lacking. Recently, a direct role of PTSNtr in regulation of K+ uptake was revealed in Escherichia coli. EIIANtr binds to the low-affinity K+ transporter TrkA (35) and to the sensor kinase KdpD (41). Binding to TrkA inhibits K+ uptake at high external K+ concentrations, while binding to KdpD at low K+ concentrations stimulates its kinase activity, thereby activating the response regulator KdpE, which in turn stimulates synthesis of the high-affinity K+ transporter KdpFABC. Absence of EIIANtr increases K+ uptake through TrkA, resulting in extraordinarily high intracellular K+ concentrations, which have been suggested to globally redirect gene expression from σ70- to σS-dependent transcription (34). The physiological meaning of this regulation is unknown. Only dephosphorylated EIIANtr is competent to bind to TrkA and KdpD (35, 41). Therefore, the identification of the signal(s) that controls phosphorylation of PTSNtr is expected to reveal the biological role of this regulation.

In addition to EI-, HPr-, and EIIA-like proteins, the EII transport proteins are also involved in regulation (47). Transcriptional antitermination proteins of the BglG/SacY family are regulatory proteins that are controlled by the activities of EIIs (for reviews, see references 15, 59, and 64). Common to these proteins are two iterative homologous PTS regulation domains (PRDs) and an N-terminal RNA-binding domain. When active, they bind a defined sequence in their target mRNAs and prevent formation of an overlapping transcriptional terminator that blocks synthesis of a specific EII and the associated catabolic functions. The activity of the antitermination proteins is in turn controlled by PTS-catalyzed phosphorylation of conserved histidines in the PRDs. One of the best-characterized members of this family is LicT of Bacillus subtilis, which regulates expression of the bglPH operon coding for the β-glucoside PTS transporter EIIBgl (BglP) and the β-glucosidase BglH (33, 55). In the absence of β-glucosides, LicT is inactivated by BglP-mediated phosphorylation of histidines 100 and 159 located in PRD1. Although these sites are not phosphorylated in the presence of substrate, this is not sufficient for activity. In addition, LicT requires phosphorylation of histidines 207 and/or 269 in PRD2 for activity, which is catalyzed by HPr (37, 62). Evidence suggests that phosphorylation of either one of these residues is sufficient for activation of LicT (62). This second, antagonistically acting phosphorylation plays a role in CCR and downregulates LicT activity in the presence of preferred PTS substrates (38). Similar models have been proposed for the homologous proteins SacT and GlcT from B. subtilis and BglG from E. coli (2, 20, 22, 54). Structural studies suggest that LicT oscillates between several conformations involving switches in the regions linking the three protein domains that ultimately control dimerization (12, 25, 65). Phosphorylation of PRD2 leads to stabilization of the active LicT dimer, and this is accomplished through contacts at the PRD interfaces. In contrast, phosphorylation of PRD1 shifts the equilibrium toward the inactive monomeric form of LicT.

A still-open question concerning BglG/SacY-type antiterminators concerns the identity of the protein that catalyzes the phosphorylations in PRD1. It was shown that in vitro HPr phosphorylates not only PRD2 but also PRD1 of several antiterminators, including LicT, SacY, and GlcT from B. subtilis. Addition of the cognate EII stimulates this phosphorylation (37, 54, 61, 62). One explanation was that all phosphorylations are catalyzed by HPr and that the kinetics of phosphorylation of PRD1 is just modified by the EII (61). Alternatively, nonphysiological high HPr concentrations in the in vitro assays were considered to be responsible for the observed phosphorylation of PRD1, which therefore should be irrelevant for regulation in vivo (62). However, for GlcT, experimental evidence suggests a direct phosphoryl group transfer from the EII to the antitermination protein (54), leaving the role of the HPr in this reaction obscure.

We are interested in the regulatory functions of the PTS and in characterization of the underlying protein-protein interactions. For a better understanding of these interactions, we started to swap PTS components of the Gram-negative organism E. coli with their homologous counterparts from the Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis. Application of this approach to HPr revealed a signature motif in its interacting surface that determines the specificity of HPr for either Gram-negative or -positive EIIs (52). In the present study, we extended this approach to the antitermination proteins and transplanted the B. subtilis licT gene to E. coli. Our data reveal that LicT becomes phosphorylated at both PRDs, even in E. coli. By using transposon mutagenesis, mutational analysis, and phosphorylation assays, the responsible phosphoryl group donors were identified. Surprisingly, HPr from E. coli phosphorylates PRD1 rather than PRD2 of LicT, leading to its inactivation. In contrast, the activating phosphorylation at PRD2 is catalyzed by the HPr homolog NPr of the PTSNtr. Hence, subtle differences in the interaction surface of HPr-like proteins determine whether PRD1 or PRD2 becomes phosphorylated. The data provide insight into the specificity determinants required for interaction with either PRD1 or PRD2 of LicT. Most importantly, we show that LicT is a useful tool for the identification of factors that alter the phosphorylation state of PTSNtr in E. coli. In making the first use of this device, we identified the stringent starvation protein SspA as a regulator of phosphorylation of EIIANtr, suggesting that the PTSNtr has a role in the stress response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and plasmids.

LB was used as standard medium. Where necessary, antibiotics were added to final concentrations of 50 μg/ml (ampicillin), 10 μg/ml (tetracycline), 20 μg/ml (chloramphenicol), 40 μg/ml (kanamycin), and 50 μg/ml (erythromycin). MacConkey-lactose plates were prepared from Difco MacConkey agar base supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) lactose. For induction of the tacOP promoter, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.1 or 1 mM) was added as indicated. Plasmids were constructed following standard techniques. Their relevant structures are given in Table 1. When necessary, protruding DNA ends were filled in with Klenow polymerase. Sequences of oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis and PCR cloning are given in Table S1 of the supplemental material. Details on plasmid construction are also provided in the supplemental material.

Table 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid name | Relevant structurea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pFDX2656 | tacOP-SDlicT-licTtet ori p15A | 55 |

| pFDX2676 | lacIq P16-bglt2-lacZtet ori ColEI | 22 |

| pFDX3194 | tacOP-SDlicT-licT in MCS of pLDR10 | This work |

| pFDX3219 | tacOP-SDbglG-licT in MCS of pLDR10 | This work |

| pFDX3526 | lacIq P16-bglt2-lacZ-lacYtet ori ColEI | This work |

| pFDX4254 | mTn10::ery λPR::ats transposase, cat, cis elements of ori pSC101 | This work |

| pFDX4260 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H100A mutation | This work |

| pFDX4261 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H100D mutation | This work |

| pFDX4262 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H159A mutation | This work |

| pFDX4263 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H159D mutation | This work |

| pFDX4275 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H207A mutation | This work |

| pFDX4277 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H269A mutation | This work |

| pFDX4278 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H269D mutation | This work |

| pFDX4279 | Same as pFDX3219, but licT has H207D mutation | This work |

| pFDX4291 | Operatorless Ptac-SDsacB-MCS cat ori pSC101 | 31 |

| pFDX4292 | npr under Ptac control in pFDX4291 | 31 |

| pFDX4294 | ptsN under Ptac control in pFDX4291 | 31 |

| pFDX4296 | ptsN-yhbJ-npr under Ptac control in pFDX4291 | 31 |

| pFDX4298 | ptsP under Ptac control in pFDX4291 | This work |

| pFDX4334 | npr(H16A) under Ptac control in pFDX4291 | This work |

| pFDX4583 | lacIq P16-bglt2-lacZtet ori p15A | This work |

| pFDY226 | lacIq P16-bglt2-lacZbla ori ColEI | 55 |

| pLDR8 | λint under control of λPR, λcI857 neo ori pSC101-rep(Ts) | 16 |

| pLDR10 | bla λattPneo ori ColEI MCS | 16 |

SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence; MCS, multiple cloning site.

Strain constructions.

The genotypes of relevant E. coli strains are given in Table 2. The tacOP-licT cassettes were integrated into the λattB site on the chromosome by using the λatt integration system as described previously (16). Briefly, originless DNA fragments carrying the respective cassette, the λattP site, and the bla selection marker were isolated by NotI digestion and circularized by self-ligation. Subsequently, they were introduced into target strains, which contained helper plasmid pLDR8 carrying the temperature-inducible λ integrase gene and a temperature-sensitive origin of replication. Selection of transformants at 42°C on ampicillin-containing plates resulted in site-specific recombination of the circularized DNA fragments with the chromosomal attB site.

Table 2.

E. coli strains used in this study

| E. coli strain | Genotypea | Reference or construction |

|---|---|---|

| IBPC903 | hfrHlacZ43 λ relA1spoT1thi1ΔpcnB::kan | 30 |

| JW0740 | Δ(araD-araB)567ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB-3) λ− ΔgalK729::kanrph-1 Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568hsdR514 | 4 |

| JW1510 | Δ(araD-araB)567 ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB-3) λ−ΔlsrF738::kanrph-1 Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568hsdR514 | 4 |

| JW1511 | Δ(araD-araB)567 ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB-3) λ−ΔlsrG739::kanrph-1 Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568hsdR514 | 4 |

| JW3197 | Δ(araD-araB)567 ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB-3) λ− ΔsspB756::kanrph-1 Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568hsdR514 | 4 |

| JW3198 | Δ(araD-araB)567 ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB-3) λ− ΔsspA757::kanrph-1 Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568hsdR514 | 4 |

| LR2-175 | F− thi-1 argG6 metB1 hisG1 lacY1 galT6 xyl-7 rpsL104 ΔphoA8 supE44 galP50 manI161 manA162 nagE167 ptsG168 fru-174 | 57 |

| R1279 | CSH50 Δ(pho-bgl)201 Δ(lac-pro) arathi | 22 |

| R1653 | Same as R1279, but Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | 22 |

| R1958 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-bglG (bla) | 22 |

| R2051 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-bglG (bla) Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | 22 |

| R2077 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDlicT-licT (bla) | pFDX3194/NotI→R1279, this work |

| R2079 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDbglG-licT (bla) | pFDX3219/NotI→R1279, this work |

| R2105 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDlicT-licT (bla) Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | T4-GT7 (TP2811)→R2077, this work |

| R2107 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDbglG-licT (bla) Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | T4-GT7 (TP2811)→R2079, this work |

| R2404 | Same as R1279, but ΔptsP | 31 |

| R2409 | Same as R1279, but ΔptsP Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | 31 |

| R2413 | Same as R1279, but Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] | 31 |

| R2415 | Same as R1279, but Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | 31 |

| R2449 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDlicT-licT (bla) ΔptsP Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | pFDX3194/NotI→R2409, this work |

| R2451 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDlicT-licT (bla) Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | pFDX3194/NotI→R2415, this work |

| R3555 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDbglG-licT (bla) Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] | pFDX3219/NotI→R2413, this work |

| R3557 | Same as R1279, but attB::tacOP-SDbglG-licT (bla) Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | pFDX3219/NotI→R2415, this work |

| TP2811 | F− xyl argH1 ΔlacX74 aroB ilvA Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]::neo | 36 |

| TP2862 | F− xyl argH1 ΔlacX74 aroB ilvA Δcrr::neo | 36 |

| Z267 | Same as R1279, but attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | 41 |

| Z269 | Same as R1279, but ΔptsP attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | 41 |

| Z501 | Same as R1279, but ptsN-3×FLAG::kanattB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | PCR BG741/742→Z267, this work |

| Z502 | Same as R1279, but ptsN-3×FLAG::kan ΔptsP attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (Z501)→Z269, this work |

| Z504 | Same as R1279, but ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | Z501 cured from kan, this work |

| Z505 | Same as R1279, but ptsN-3×FLAG ΔptsP attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | Z502 cured from kan, this work |

| Z522 | Same as R1279, but sspB::kan ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (JW3197)→Z504, this work |

| Z523 | Same as R1279, but sspA::kan ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (JW3198)→Z504, this work |

| Z540 | Same as R1279, but lsrF::kan ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (JW1510)→Z504, this work |

| Z541 | Same as R1279, but lsrG::kan ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (JW1511)→Z504, this work |

| Z548 | Same as R1279, but galK::kan ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (JW0740)→Z504, this work |

| Z549 | Same as R1279, but pcnB::kan ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | T4-GT7 (IBPC903)→Z504, this work |

| Z571 | Same as R1279, but sspAB::cat ptsN-3×FLAG attB::kdpFA′-lacZ (aadA) | PCR BG851/852→Z504, this work |

| ZSC103a | ptsG manA glk-7 rpsL | 9 |

| ZSC112L | ptsM glk strA ptsG::Cm | 9 |

SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence.

Strain Z501 carrying the ptsN-3×FLAG::kan allele was constructed using plasmid pSUB11 (63). Briefly, the kan cassette of plasmid pSUB11 was amplified by PCR using primers BG741/BG742, and the PCR fragment was introduced into strain Z267 to obtain strain Z501 upon recombination. The ptsN-3×FLAG::kan allele of Z501 was moved to strain Z269 by phage T4-GT7 transduction (70), which resulted in strain Z502. The kan cassettes of strains Z501 and Z502 were removed using plasmid pCP20 (10), which yielded strains Z504 and Z505. Subsequently, various deletion alleles tagged with a kan cassette were introduced into strain Z504 by transduction using phage T4-GT7, which yielded strains Z522 to Z549. The sspAB double mutation present in strain Z571 was constructed by introducing into strain Z504 a PCR fragment that was generated using primers BG851/BG852 and the template plasmid pKD46, as described previously (10). Strain constructions were verified by diagnostic PCR.

Determination of β-galactosidase activity.

β-Galactosidase assays were carried out as described previously (42). Cells were grown in minimal medium (M9) containing proline (20 μg/ml), thiamine (1 μg/ml), Casamino Acids (0.66% [wt/vol]), the appropriate antibiotics, and 1% (wt/vol) glycerol as carbon source if not otherwise indicated. Activities were determined from exponentially growing cells. Presented values are the means of at least three measurements from independent cultures.

Radioactive labeling of proteins in vivo.

In vivo protein phosphorylation using H3[32P]O4, labeling with [35S]methionine, and subsequent SDS-PAGE were performed as described previously (22, 23). Dried gels were autoradiographed by phosphorimaging, and signals were quantified using the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Determination of phosphorylation state of EIIANtr.

Cultures of strains carrying the 3×FLAG epitope fused to the 3′ end of the gene ptsN were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 to 0.8. Cells corresponding to 1 OD600 unit were harvested by centrifugation (4°C, 13,000 rpm, 10 min), and the pellets were resuspended in 200 μl sample buffer containing 10% glycerol and 0.05% bromophenol blue. Thirteen-microliter aliquots of these suspensions were directly loaded on nondenaturing gels prepared from 12% modified acrylamide ProSieve 50 (Lonza) in 375 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.7). Exposure of the gels to a voltage of 100 V resulted in release of the proteins by dielectric breakdown, as reported previously for Pseudomonas putida (44). Gels were run at 4°C using 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.7), 192 mM glycine as running buffer. After separation, the proteins were electroblotted for 1 h at 0.8 mA cm−2 to a polyvinyl difluoride membrane. EIIANtr-3×FLAG was detected using anti-FLAG antibodies produced in rabbits (Sigma) and diluted 1:10,000. The antibodies were visualized using rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and the CDP* detection system (Roche Diagnostics).

Transposon mutagenesis.

The target strains R2079 and R2107 carrying the reporter plasmid pFDX3526 were grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5 to 1.0. Cells were transformed with the transposon delivery plasmid pFDX4254 by electroporation and subsequently stored at −80°C until their use. Aliquots were thawed and plated on LB plates containing erythromycin and tetracycline and incubated at 33°C. The obtained colonies were replica plated on MacConkey-lactose plates containing the same antibiotics and incubated overnight at 33°C. Subsequently, the colonies were screened for the phenotype of interest. To exclude that a second mutation elsewhere on the chromosome was responsible for the phenotype, the transposon insertions of mutants of interest were transduced to the respective parent strain by using phage T4-GT7 (70). The mini-Tn10 (mTn10) insertion sites of positive clones were mapped by sequencing of chromosomal DNA by using primer 742.

RESULTS

The E. coli transport PTS phosphorylates and inhibits activity of LicT.

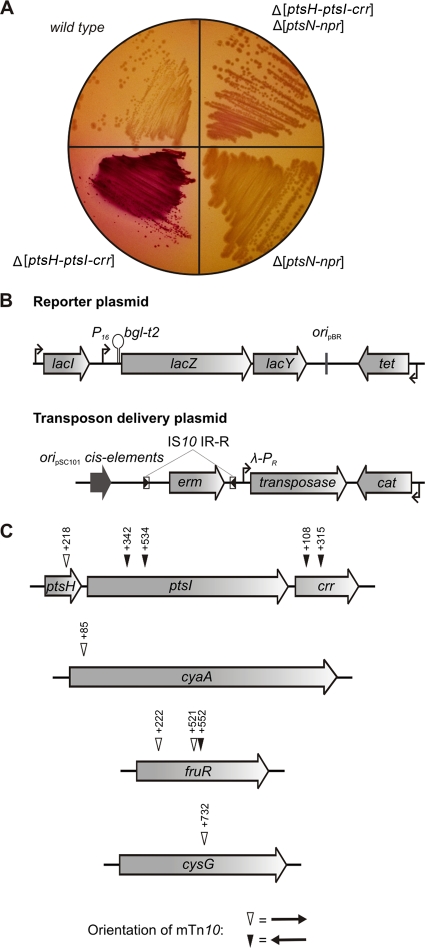

In order to study the potential regulation of the B. subtilis antiterminator protein LicT in E. coli, the licT gene was placed under the control of the IPTG-inducible tacOP to allow for regulated expression. Since the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) translation initiation sequences preceding B. subtilis genes are known to yield exceptionally high translation initiation rates in E. coli (67), two different constructs were made. One carried the native SD sequence of licT, while in the other construct the SD sequence of the E. coli bglG gene was used to start translation of licT. The latter situation also allows for comparison with an isogenic construct that carries bglG, which was used in previous studies (22, 23). Thus, these constructs should yield comparable expression levels for licT and bglG. To determine whether LicT requires HPr for activity, as in its natural host, the licT alleles were integrated into the chromosome of E. coli strain R1279 (referred to in Fig. 1 as wild-type or pts+, respectively) and an isogenic mutant carrying a deletion of the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon (coding for HPr, EI, and EIIAGlc, respectively). The strains also carried a deletion of the bgl operon to avoid interference with the naturally encoded BglG protein and its negative regulator, BglF, which is a homolog of B. subtilis BglP. To assess antitermination activity, a reporter plasmid was used that carries the bgl terminator t2 between a constitutive promoter (P16) and the lacZ reporter gene, as has been described previously (22, 23, 52) (Fig. 1A). It has been shown that in the heterologous host E. coli, LicT efficiently alleviates termination at terminator t2 of the bgl operon (55).

Fig. 1.

Regulation of LicT activity by the transport PTS in E. coli. (A) LicT is inhibited rather than activated by the transport PTS. The genes bglG and licT, which are under the control of tacOP (Ptac) and thus inducible with IPTG, were introduced into the chromosomes (λ attachment site) of isogenic pairs of wild-type (wt) and pts-negative strains. The licT gene was integrated with its native translation initiation sequences (SDlicT) and, in addition, with those of bglG (SDbglG). The resulting strains R1958, R2051, R2077, R2105, R2079, and R2107 were transformed with antitermination reporter plasmid pFDX2676, which carries the constitutive promoter P16 and the lacZ reporter gene separated by terminator bglt2 and in addition the lacI gene, providing a repressor for the control of tacOP (top). β-Galactosidase activities indicate the efficiency of transcriptional antitermination at the terminator bglt2. (B) LicT is phosphorylated in vivo by the E. coli transport PTS and by an additional activity. Strain R1279 (pts+; lanes 1 to 3) and its isogenic Δpts derivative R1653 (lanes 4 to 6) were doubly transformed with plasmid pFDX2656 carrying the tacOP-controlled licT gene and plasmid pFDY226, providing synthesis of the Lac repressor (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). Aliquots of cultures were labeled with H3[32P]O4 in the presence or absence of 1 mM IPTG as inducer for LicT synthesis, the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and bands were subsequently visualized by autoradiography. (C) Synthesis of LicT is not affected by the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutation. The transformants from panel B were labeled with [35S]methionine, and labeled proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

The various strains were grown in the absence or presence of IPTG, and β-galactosidase activities were determined. When synthesis of BglG was induced by the addition of IPTG, termination was alleviated in the wild-type strain, as previously shown, resulting in synthesis of 274 units of β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 1A). Without IPTG, only background levels of enzyme activity were obtained, indicating the known, weak leakiness of the terminator (22, 52). However, when licT was expressed to the same extent as bglG (Fig. 1A, licT with the SD of bglG), only background levels of enzyme activity were detectable in the wild-type strain, even in the presence of IPTG, while 112 units were obtained when LicT was under the control of its own, more efficient SD sequence. This picture changed drastically when the strains lacking the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon were employed. While the activity of BglG dropped to background levels as expected (22), the activity of LicT was enormously stimulated, resulting in 146 units of enzyme activity with the bglG SD sequence and even 1,703 units when under the control of its own SD sequence. It can thus be concluded that, in contrast to BglG, the activity of LicT does not require the presence of EI and HPr in E. coli but that it is, on the contrary, inhibited by the E. coli transport PTS.

Based on these unexpected results, we wanted to learn whether LicT is phosphorylated by the E. coli transport PTS, i.e., whether inactivity correlates with phosphorylation. We therefore performed metabolic H3[32P]O4 labeling of strains that expressed licT from a plasmid. This technique allows the detection of in vivo-phosphorylated proteins. A phosphorylated protein was indeed detected on the gel at the position expected for LicT, which greatly increased in signal strength when synthesis of LicT was induced by IPTG (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 3). This signal was undetectable in the strains lacking licT, demonstrating that it is LicT (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 4). When assayed in the strain missing the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon, the intensity of the LicT phosphorylation signal drastically decreased (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 6). However, residual phosphorylation of LicT was detectable, which amounted to about 10% of that seen in the wild-type strain. Since a defect of the PTS has pleiotropic effects, we compared LicT protein levels in these strains by pulse-labeling with [35S]methionine and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C). Synthesis of LicT was unaffected by the differences in strain backgrounds, confirming that the differences in strengths of the phosphorylation signals are not based on differences in LicT protein levels. In order to unambiguously verify that the IPTG-inducible protein band is indeed LicT, we identified the protein present in this band by mass spectrometry. To this end, total protein extracts of the corresponding strains were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Once more, a single IPTG-inducible protein band migrating at the position expected for LicT (molecular mass, 32.3 kDa) appeared exclusively in the transformants carrying the tacOP::licT allele on a plasmid and when IPTG was also present (see Fig. S1, lanes 4 and 8). The respective bands were isolated and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Exclusively, peptides matching LicT were identified, verifying that the IPTG-inducible protein band consists of LicT (for details, see the results of mass spectrometric analyses provided in the supplemental material).

Taken together, we can conclude that LicT is inhibited and at the same time strongly phosphorylated by the E. coli transport PTS, while it is active and still weakly phosphorylated by an activity of yet-unknown origin in the absence of a functional transport PTS.

Control of LicT activity by antagonistically acting phosphorylation activities of its PRDs is preserved in E. coli.

In the genuine host B. subtilis, activity of LicT is regulated by multiple phosphorylations of the conserved histidines in the PRDs. Phosphorylation of PRD1 is mediated by BglP and inactivates LicT, while phosphorylation of PRD2 by HPr is a prerequisite for its activity. Our data suggested that in wild-type E. coli LicT is likewise inactivated by phosphorylation catalyzed by a yet-unknown protein of the transport PTS. Surprisingly, LicT was highly active in the absence of HPr. The residual phosphorylation of LicT in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant suggested that another protein can take over the activating function of HPr. To assess whether LicT is subject to dual phosphorylation of its PRDs also in E. coli, we tested LicT mutants carrying individual amino acid exchanges of each of the four phosphorylated histidines. The effects of mutations in these sites have been extensively investigated in the authentic host, B. subtilis (62). It was shown that the nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated states of the individual histidines could be mimicked by alanine and aspartate substitutions, respectively. Therefore, licT mutants carrying Ala as well as Asp substitutions of each of the four histidines were placed on plasmids and introduced into the “wild-type” strain, R1279, and the isogenic Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant, R1653. A compatible antitermination reporter plasmid allowed for the monitoring of LicT activity. Expression of wild-type licT resulted in 10-fold-higher antitermination activities in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant than the wild-type strain (Fig. 2, columns 1 and 2), reflecting the results obtained before with the chromosomally encoded licT alleles (Fig. 1A). Examination of the various licT alleles yielded results that were generally very similar to those obtained previously with these mutants in B. subtilis (62). Substitution of the negative regulatory sites His100 and His159 with Ala residues resulted in high antitermination activities in both the wild-type strain and the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant (Fig. 2, columns 9, 10, 17, and 18). In contrast, the Asp substitutions of these sites led to low antitermination activities (Fig. 2, columns 13, 14, 21, and 22). This indicated that both histidines are also phosphorylated in the E. coli wild-type strain, causing inactivation of LicT, while they are not phosphorylated in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant, leading to a high LicT activity. Substitution of the positive regulatory site His207 or His269 with Ala resulted in completely inactive LicT variants in both strains (Fig. 2, columns 25, 26, 33, and 34), suggesting that LicT requires phosphorylation at these sites for activity even in E. coli. In contrast, substitution of these sites with Asp restored wild-type LicT behavior (Fig. 2, columns 29, 30, 37, and 38), demonstrating that these exchanges are able to mimic phosphorylation of these sites. Collectively, the data indicate that LicT is controlled by antagonistically acting phosphorylations even in E. coli. In the wild-type strain, LicT is phosphorylated at His100 and His159, leading to its inactivity. Although these inhibitory phosphorylations do not occur in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant, this is not sufficient for LicT activity. In addition, LicT requires phosphorylation of His207 and/or His269 in PRD2 for its activity, as is the case in its genuine host.

Fig. 2.

Effects of mutations of the four histidine phosphorylation sites on LicT activity in wild-type E. coli and mutants lacking a functional transport PTS, PTSNtr, or both. Strains R1279 (wild type), R1653 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]), R2413 (Δ[ptsN-npr]), and R2415 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-npr]) were transformed with antitermination reporter plasmid pFDX4583 and, in addition, with the following plasmids carrying various licT alleles under tacOP control: pFDX3219 (wild-type licT; columns 1 to 4), pLDR10 (empty plasmid; columns 5 to 8), pFDX4260 [licT(H100A); columns 9 to 12], pFDX4261 [licT(H100D); columns 13 to 16], pFDX4262 [licT(H159A); columns 17 to 20], pFDX4263 [licT(H159D); columns 21 to 24], pFDX4275 [licT(H207A); columns 25 to 28], pFDX4279 [licT(H207D); columns 29 to 32], pFDX4277 [licT(H269A); columns 33 to 36], pFDX4278 [licT(H269D); columns 37 to 40]. For the induction of LicT synthesis, 0.1 mM IPTG was added to the cultures. The β-galactosidase activities produced by the transformants are depicted. The values corresponding to the individual columns are shown below the graph.

In order to also provide biochemical evidence that LicT is phosphorylated at histidine residues when present in E. coli, we tested the stability of the phosphoryl group bonds in LicT toward treatment with hydroxylamine, NaOH, heat, and acid (see Fig. S2 and its legend in the supplemental material for details). By this approach, the phosphoryl groups on BglG were previously characterized as phosphoamidates, i.e., N-phosphates (1). Therefore, we used phospho-BglG as a control and tested it in parallel to phospho-LicT. Cells overproducing LicT or BglG were labeled with H3[32P]O4, and the labeled proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Treatment of the gel with hydroxylamine resulted in the disappearance of phospho-BglG as well as phospho-LicT, while an alkali treatment of the gel had no effect (see Fig. S2A to C). Treatment of the samples with heat for increasing times prior to their being loaded onto the gels resulted in increased loss of the LicT phosphorylation signal, and this disappearance was drastically accelerated in the presence of HCl (see Fig. S2D). Phospho-ester amino acids are stable in the presence of hydroxylamine, acid, and heat but sensitive to alkali treatment. Phospho-tyrosines and phospho-cysteines are stable under acidic as well as basic conditions, while acyl-phosphates are labile under both conditions (1, 3). In sum, the results are only compatible with the properties of phospho-amidates. Only one case of phosphorylation of a protein at an arginine is known in bacteria, while phosphorylation of lysines has not been reported (7, 19). Thus, these results provide further evidence that in E. coli exclusively histidine(s) is phosphorylated in LicT, as is the case in the cognate host.

The transposon mutagenesis screen for relief of inhibition of LicT activity in E. coli yielded mutations in the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon.

Next, we were keen to identify the unknown phosphoryl group donors responsible for regulation of LicT activity in E. coli. Thereby, we hoped to learn more about the specificity determinants required for interactions of proteins with either PRD1 or PRD2 of LicT. To identify the negative regulator of LicT, a transposon mutagenesis screen was performed. For this purpose, we used a modified antitermination reporter plasmid that additionally carried the gene lacY, encoding lactose permease, transcriptionally fused to the upstream-located P16-bglt2-lacZ reporter cassette (Fig. 3B, top). Thus, only cells that contain active LicT express the lacZY genes and are able to utilize lactose. Accordingly, the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant R2107 carrying this reporter plasmid and the tacOP::licT cassette on the chromosome formed red colonies on MacConkey-lactose plates, indicating lactose utilization, while colorless colonies were obtained with the isogenic “wild-type” R2079 (Fig. 3A). This phenotypic difference appeared to be suitable for the screening of mutations that alter activity of LicT.

Fig. 3.

Transposon mutagenesis screen for identification of the negative regulator of LicT activity in E. coli. (A) Phenotypes of strains R2079 (wild type), R2107 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]), R3555 (Δ[ptsN-npr]), and R3557 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-npr]) on MacConkey-lactose plates. All strains carried reporter plasmid pFDX3526 (see panel B) and the tacOP::licT cassette on the chromosome. (B) Relevant structures of the reporter plasmid pFDX3526 (top) and the transposon delivery plasmid pFDX4254 (bottom) used in the mutagenesis screens. As a contrast with the reporter plasmids pFDX2676 and pFDX4583 (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2), plasmid pFDX3526 additionally carries the lacY gene, encoding lactose permease, in tandem with lacZ. Therefore, high LicT activity leads to expression of lacZY, which allows the bacterium to transport and utilize lactose as a carbon source. This permits the screening of LicT activity on MacConkey-lactose indicator plates. Transposon delivery plasmid pFDX4254 carries a transposable erythromycin resistance gene encompassed by copies of the right inverted repeat (IR-R) of IS10. The ats transposase, which is an IS10-derived transposase with relaxed target site recognition (6), is encoded outside the mTn10 cassette and expressed constitutively from the λ-PR promoter. The plasmid carries only the cis elements of plasmid pSC101 required for replication, while the repA gene is absent. Thus, pFDX4254 can only replicate in engineered host strains that provide the repA gene in trans. This minimizes the possibility of multiple transpositions, since the plasmid is rapidly lost by the target strains. (C) Transposon insertions obtained in the screen for loss of inhibition of LicT activity in wild-type strain R2079. Cells of strain R2079 carrying licT on the chromosome and reporter plasmid pFDX3526 were transformed with transposon delivery plasmid pFDX4254 by electroporation. Transposant colonies were selected on LB plates containing erythromycin and tetracycline and subsequently replica plated on MacConkey-lactose plates containing the same antibiotics. Colonies exhibiting a dark red phenotype, indicating lactose fermentation, were isolated, and the transposon insertion sites were identified by sequencing. The location and the orientation of the transposon insertions are indicated by open and closed triangles, respectively. The positions of the mTn10 insertions are indicated relative to the first nucleotide of the respective gene.

The “wild-type” strain R2079 carrying licT was subjected to transposon mutagenesis by using the mTn10 transposon delivery plasmid pFDX4254 (Fig. 3B, bottom). Ten mutants were isolated that exhibited a Lac+ phenotype. Mapping of the mTn10 insertion sites revealed insertions in the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon in five mutants (Fig. 3C). One insertion disrupted ptsH, while ptsI and crr were hit two times each at different positions. The remaining insertions were located in cyaA, which encodes adenylate cyclase, in fruR, which encodes the pleiotropic transcriptional regulator Cra, and in cysG, which codes for a siroheme synthase (Fig. 3C). The genes cyaA, fruR, and cysG encode proteins that are not involved in phosphorylations, indicating that their disruption acted indirectly on LicT activity or on lactose utilization. The gene cysG is required for biosynthesis of siroheme, which is a prosthetic group present in sulfite and nitrite reductases (69). The inactivation of cya has pleiotropic effects on the expression of numerous genes due to the pivotal role of cyclic AMP (cAMP) in CCR. Notably, cAMP-CRP is also required for high expression of ptsH and ptsI (13, 46), raising the possibility that the cyaA::mTn10 mutation acted through downregulation of ptsH and ptsI expression on LicT activity. FruR is a global transcriptional regulator that controls synthesis of enzymes of the Krebs cycle and gluconeogenesis (51). The mechanism underlying the Lac+ phenotype of the fruR mutants remains to be determined.

In E. coli, the phosphorylation that inhibits LicT activity is apparently catalyzed by HPr and does not involve an enzyme II.

The results from the transposon mutagenesis suggested that the negative regulator of LicT is encoded in the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon. Apart from crr, which encodes EIIAGlc, a gene coding for an EII of the PTS could not be identified, suggesting that inactivation of LicT in E. coli does not involve a PTS transporter. Antitermination proteins of the BglG/SacY family are usually only active in the presence of specific substrate for their cognate EII. In order to further assess whether inactivation of LicT requires a specific EII in E. coli, we determined LicT activity in wild-type cells grown in minimal medium supplemented with different carbon sources (Table 3). Interestingly, there was no substrate that specifically caused activation of LicT. In contrast, activity of LicT varied with the carbon source and was highest when cells utilized glucose, N-acetyl-glucosamine (NAG), or mannitol, which are preferred substrates for E. coli. Their utilization leads to preferential dephosphorylation of the general PTS proteins EI, HPr, and EIIAGlc, while these proteins are preferentially phosphorylated when less-preferred carbon sources, such as mannose or glycerol, are utilized (8, 28). Thus, there is an inverse correlation of LicT activity and the degree of phosphorylation of the general PTS enzymes (Table 3). These results are incompatible with a mechanism that involves a specific EII controlling the activity of LicT. They are most easily explained by a drain of the phosphoryl groups from PRD1 of LicT via HPr to the incoming sugar.

Table 3.

Effect of carbon source on antitermination activity of LicT in E. colia

| Carbon source | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) | % phosphorylation of EIIAGlc (EIIAGlc∼P) |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | 107 ± 9 | 47 ± 4 |

| Trehalose | 73 ± 6 | NDb |

| Mannose | 78 ± 4 | 48 ± 22 |

| Sorbitol | 82 ± 4 | 26 ± 10 |

| Fructose | 132 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 |

| Mannitol | 199 ± 3 | 14 ± 6 |

| N-Acetyl-glucosamine | 422 ± 23 | 17 ± 10 |

| Glucose | 645 ± 31 | 5 ± 2 |

β-Galactosidase activities (means ± standard deviations) were determined from cultures of strain R2077-pFDX2676 grown in M9 minimal medium supplemented with the indicated carbon source in the presence of 1 mM IPTG as inducer for LicT expression. The relative amounts of phosphorylated EIIAGlc protein (according to reference 8) reflecting the phosphorylation status of EI and HPr are shown for comparison.

ND, not determined.

How can the mTn10 insertions in gene crr be explained? Several EIIs of the PTS depend on phosphorylation by EIIAGlc. Although our experiments made phosphorylation of LicT by a specific EII unlikely, we wanted to ultimately rule out that EIIAGlc or an EIIAGlc-dependent EII catalyzes this phosphorylation. Therefore, we tested phosphorylation of LicT in mutants lacking EIIAGlc or EIICBGlc (encoded by ptsG) by 32P labeling. The absence of these proteins did not impair phosphorylation of LicT (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, a reasonable explanation for the Lac+ phenotype of the crr::mTn10 mutants might be an increased LacY activity in this mutant. The activity of LacY is limited by an autoregulatory loop that involves interaction with EIIAGlc (29). Alternatively, the mTn10 insertions in crr could destabilize the pts operon transcripts, leading to poor synthesis of EI and HPr. Indeed, destabilization of the ptsHI mRNA by insertions has been observed in Lactobacillus sake (58). In sum, the data provide evidence that the phosphorylation inhibiting LicT activity in E. coli is directly catalyzed by HPr and does not involve a specific EII.

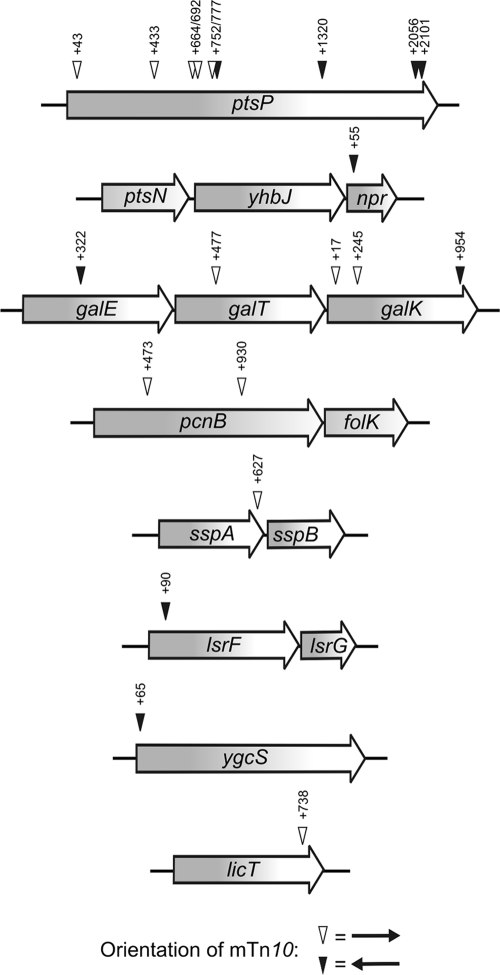

A transposon mutagenesis screen for mutations leading to loss of LicT activity in E. coli identified EINtr and NPr.

The next task was to identify the phosphoryl group donor responsible for activity of LicT in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant. Therefore, once more a transposon mutagenesis was performed, but this time the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant carrying the tacOP::licT cassette on the chromosome (strain R2107) (Fig. 3A) was used. Twenty-one insertion mutants were isolated, which exhibited colorless colonies on MacConkey-lactose plates (Fig. 4). Nine of these mutants carried insertions in the gene ptsP, encoding EINtr, and one mutant carried the mTn10 in the gene npr, encoding NPr, which delivers phosphoryl groups from EINtr to EIIANtr. In five mutants, the insertions were located in the gal operon and likely impaired utilization of the galactose moiety of lactose, explaining the Lac− phenotype. In one case, the licT gene itself was disrupted. Two mutants carried disruptions of gene pcnB, which codes for poly(A) polymerase. Mutations in pcnB drastically reduce the copy number of ColEI-type plasmids (40), such as the reporter plasmid used in the screen, which may explain the Lac− phenotype. The remaining insertions were located in the genes sspA, encoding the stringent starvation protein A (26), lsrF, which plays a role in processing of the quorum-sensing signal AI-2 (71), and ygcS, which encodes a putative transport protein of so-far-unknown function (Fig. 4). None of the latter genes is known to encode a protein involved in phosphoryl group transfer reactions.

Fig. 4.

Transposon mutagenesis screen for identification of genes required for LicT activity in E. coli. Transposon insertions obtained in the screen for loss of LicT activity in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] strain R2107 are shown. The reporter plasmid and the transposon delivery plasmid used in the screen are described in Fig. 3B. The screen was carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 3B except that mutants exhibiting colorless colonies were isolated and characterized.

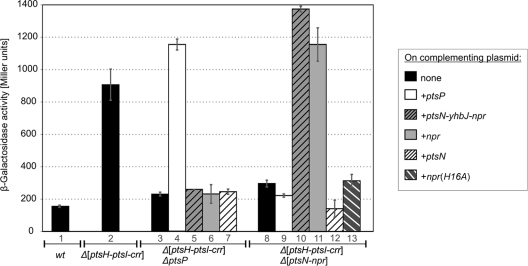

EINtr and NPr are essential for activity of LicT in E. coli, whereas EIIANtr is dispensable.

The results of the mutagenesis screen indicated that the genes ptsP and npr are required for the activity of LicT in E. coli. To dissect the involvement of PTSNtr in activation of LicT, a complementation analysis was carried out. Double mutants were tested that carried a deletion of the ptsH-ptsI-crr operon and additionally lacked ptsP or the gene cluster ptsN-yhbJ-npr (ptsN encodes EIIANtr). The strains carried the tacOP::licT cassette on the chromosome and a reporter plasmid for monitoring LicT activity. In both double mutants, expression of the lacZ reporter gene was much lower than in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] single mutant (Fig. 5, columns 1, 2, 3, and 8). Complementation of the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] ΔptsP mutant with a plasmid expressing ptsP restored high lacZ expression, while plasmids carrying either npr or ptsN or the complete ptsN-yhbJ-npr gene cluster had no effect (Fig. 5, columns 3 to 7). Similarly, the presence of plasmids that expressed npr restored high lacZ expression in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] mutant, while complementation with plasmids carrying ptsP or ptsN was without effect (Fig. 5, columns 8 to 12). These data show that both EINtr and NPr are required for LicT activity in E. coli, whereas EIIANtr is dispensable.

Fig. 5.

In E. coli, activity of LicT requires EINtr and NPr. Strains R2077 (wild type; column 1), R2105 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr]; column 2), R2449 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] ΔptsP; columns 3 to 7), and R2451 (Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-npr]; columns 8 to 13) were used for complementation analysis. These strains carried the chromosomal tacOP::licT cassette, reporter plasmid pFDX3526, and, in addition, one of the following complementation plasmids: pFDX4291 (empty plasmid; columns 1, 2, 3, and 8), pFDX4298 (ptsP; columns 4 and 9), pFDX4296 (ptsN-yhbJ-npr; columns 5 and 10), pFDX4292 (npr; columns 6 and 11), pFDX4294 (ptsN; columns 7 and 12), and pFDX4334 [npr(H16A); column 13]. The β-galactosidase activities produced by these transformants in the presence of 0.1 mM IPTG are shown.

Evidence for phosphoryl group transfer from NPr to PRD2 of LicT.

Phosphorylation of NPr requires the presence of EINtr. Hence, the data suggested a transfer of phosphoryl groups from EINtr via NPr to LicT. To test this possibility, the phosphorylation site His16 in NPr was exchanged for an Ala residue. Indeed, this mutation abolished the ability of NPr to stimulate lacZ expression and, hence, LicT activity in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] mutant (Fig. 5, columns 8, 11, and 13). Hence, NPr is most likely the protein donating phosphoryl groups to LicT.

Next, we wanted to confirm that NPr is responsible for phosphorylation of the histidines in PRD2 of LicT. To this end, we investigated the activities of the various LicT variants carrying mutations of the four histidine phosphorylation sites in the Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] and Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] mutants (strains R2413 and R2415) (Fig. 2). None of the LicT variants exhibited high antitermination activity in the Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] strain. Notably, even the mutants carrying the His100Ala and His159Ala exchanges exhibited only low activities, although they were active in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2, columns 9, 11, 17, and 19). This suggests that NPr transfers phosphoryl groups to LicT not only in the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] mutant but also in the wild type. In the Δ[ptsH-ptsI-crr] Δ[ptsN-yhbJ-npr] double mutant, exclusively the His207Asp and His269Asp LicT mutants gained activity (Fig. 2, columns 32 and 40), demonstrating that the lack of activation by NPr can be compensated by Asp mutations mimicking phosphorylation of the His residues in PRD2 of LicT. In sum, the data indicate that NPr transfers phosphoryl groups to PRD2 of LicT, leading to its activation.

Mutations in sspA impair phosphorylation of EIIANtr, the effector protein of the PTSNtr.

According to our data, NPr activates LicT by its phosphorylation in E. coli. Normally, NPr transfers phosphoryl groups from EINtr to EIIANtr. When nonphosphorylated, EIIANtr interacts with target proteins to regulate the activities of K+ transporters. However, the signal(s) that triggers (de)phosphorylation of PTSNtr and thereby its regulatory output is essentially unknown. Therefore, we reasoned that LicT could be a useful tool for the identification of factors that influence the phosphorylation state of PTSNtr. Alongside the mutations in ptsP and npr, we had identified additional mutations in the screen for loss of LicT activity (Fig. 4). One possibility was that these additional mutations mechanistically acted through impaired phosphorylation of EINtr and/or NPr, resulting in low LicT activity and, in parallel, in reduced phosphorylation of EIIANtr. To address this possibility, we determined the phosphorylation state of EIIANtr. To this end, we applied nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, which enables the simultaneous detection of the phosphorylated as well as nonphosphorylated forms of a phosphoprotein. To allow for the detection of EIIANtr, a sequence coding for the 3×FLAG epitope was fused to the 3′ end of gene ptsN at its natural chromosomal locus. Next, we separated extracts of the “wild-type” strain Z504 and the isogenic ΔptsP mutant Z505 by nondenaturing PAGE and detected EIIANtr-3×FLAG by subsequent Western blotting using anti-FLAG antiserum. In the wild-type strain, only a faster-migrating EIIANtr band could be detected, while in the ptsP mutant only a slower-migrating band was detectable (Fig. 6, compare lanes 1 and 7 with lanes 2, 5, and 8). This result indicated that EIIANtr is almost completely phosphorylated in the wild-type strain and nonphosphorylated in the absence of EINtr, at least under the conditions employed. Next we tested isogenic mutants carrying deletions of genes that were identified in the screen for reduced LicT activity (Fig. 4). Deletion mutants of the genes sspB and lsrG were also employed to account for polar effects of the mTn10 insertions in sspA and lsrF. Deletion of sspB, lsrF, lsrG, pcnB, or galK had any effect on the phosphorylation state of EIIANtr (Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 11 to 14 and data not shown). In contrast, two bands corresponding to nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated EIIANtr were detectable in the sspA mutant (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 10). Since the isolated mTn10 insertion in sspA (Fig. 4) supposedly also affected the expression of sspB, an sspA sspB double mutant was employed. However, the additional presence of the sspB mutation had no further effect on the ratio of the two forms of EIIANtr compared to the sspA single mutant (Fig. 6, lanes 9 and 10). Thus, the sspA mutation appears to be sufficient for the inhibition of the phosphorylation of EIIANtr, demonstrating that the SspA protein influences EIIANtr phosphorylation in a positive way. Hence, LicT in general is a useful tool for the identification of modulators of the phosphorylation state of EIIANtr, the regulatory output device of the PTSNtr.

Fig. 6.

Determination of the phosphorylation state of EIIANtr in various mutants. Strains that carried a 3×FLAG-tagged ptsN gene in the chromosome and had the indicated genotypes were grown in minimal glucose medium. Crude extracts were separated by nondenaturing PAGE. EIIANtr-3×FLAG was subsequently detected by Western blotting using anti-FLAG antiserum. The following strains were employed: Z504 (wild type; lanes 1 and 7), Z505 (ΔptsP; lanes 2 and 5), Z522 (ΔsspB::kan; lanes 3 and 11), Z523 (ΔsspA::kan; lanes 4 and 10), Z571 (ΔsspAB::kan; lane 9), Z540 (ΔlsrF; lane 12), Z541 (ΔlsrG; lane 13), Z549 (ΔpcnB; lane 14). As a control for specificity of the antiserum, the wild-type strain lacking the 3×FLAG sequence was also employed (Z267; lane 6).

DISCUSSION

Antitermination proteins of the BglG/SacY family are widespread and found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In E. coli, the antitermination protein BglG regulates the bgl operon required for β-glucoside utilization (56). In B. subtilis, the analogous regulation is carried out by LicT, which shares 42% sequence identity with BglG. A phylogenetic study suggested that the bgl system was acquired by a horizontal gene transfer event, presumably from a Gram-positive bacterium such as B. subtilis (53). Not surprisingly, both antitermination proteins are similarly regulated in their hosts, involving EIIBgl- and HPr-catalyzed phosphorylation of their PRDs (Fig. 7A) (20, 22, 37, 62). In the present study, we showed that despite these similarities, LicT is not regulated the same way when transferred to E. coli. Surprisingly, LicT gained activity only in the absence of the general PTS proteins EI and HPr. Our results indicate that in E. coli LicT is phosphorylated by HPr at PRD1 rather than PRD2, leading to its inactivity. In the absence of HPr, LicT is active in E. coli, but this activity requires the HPr homolog NPr, which apparently phosphorylates LicT at PRD2 (see the model in Fig. 7B). These observations not only provide further insight into the role of HPr for the control of antitermination proteins (see below) but also may be useful for the design of reporter systems suited for monitoring the phosphorylation states of HPr and NPr in living E. coli cells. The LicT variants carrying His→Asp exchanges in PRD2 lost the requirement for NPr and were exclusively subject to negative regulation by HPr∼P (Fig. 2). Thus, activity of these mutants and, accordingly, reporter readout are directly coupled to the degree of HPr dephosphorylation. Using green fluorescent protein (GFP) as the reporter gene may even allow monitoring of the phosphorylation state of HPr in single cells. So far, cAMP/CRP-dependent reporter systems, which reflect the PTS phosphorylation state only indirectly, have been used in system biology approaches addressing the PTS (8). Similarly, the LicT mutants carrying the His→Ala exchanges in PRD1 escape negative regulation by HPr but are still regulated by NPr, and they are therefore useful for monitoring its phosphorylation state in vivo. Indeed, by using LicT as a tool we identified the protein SspA as a modulator of the phosphorylation state of NPr and thus of PTSNtr (see below).

Fig. 7.

Regulation of the B. subtilis antitermination protein LicT by proteins of the PTS in its cognate host (A) and in E. coli (B). (A) In B. subtilis the β-glucoside transporter EIIBgl (BglP) inhibits LicT activity in the absence of substrate. This inhibition involves the transfer of phosphoryl groups to PRD1. Substrate availability results in the reversible process. In addition, LicT requires phosphorylation of PRD2 for activity, which is directly catalyzed by HPr. The model is based on previously published evidence (33, 37, 62). (B) In E. coli, activity of LicT is likewise controlled by antagonistically acting phosphorylations (present study). However, in this host the inhibitory-acting phosphorylation of PRD1 is catalyzed by HPr, while the stimulatory-acting phosphorylation of PRD2 is carried out by the HPr homolog NPr. NPr is a member of the regulatory PTSNtr. Thus, LicT is a tool suitable for the identification of conditions that alter the phosphorylation state of PTSNtr and thereby its regulatory output. (C) Amino acid sequence alignments of HPr proteins from Firmicutes and NPr and HPr proteins from Enterobacteriaceae. The positions of the α-helices and β-sheets are indicated at the top. Residues within the interaction surface that are identical or similar in the Gram-positive HPr and NPr proteins, but differ in the Gram-negative HPrs, are indicated with arrows. Identical residues are shown in red, conserved residues are shown in blue, and similar residues are shown in green.

How can the unexpected rerouting of phosphoryl transfer reactions, as observed here for LicT in E. coli, be explained? The fold of HPr-like proteins consists of three α-helices on top of a four-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet. HPr and NPr interact with other proteins through the same narrow region, composed of helices α1 and α2 and the loops preceding α1 and following α2 (15, 68). However, several residues in the interaction surface are not conserved between Gram-positive and Gram-negative HPr proteins (Fig. 7C). These differences prevent efficient interaction of B. subtilis HPr with the EIIs from E. coli, as shown previously (52), and supposedly they are also responsible for the inability of E. coli HPr to phosphorylate PRD2 of LicT, as observed here. Interestingly, several features of the interaction surface of the Gram-positive HPrs are shared with the NPr proteins, but not with the Gram-negative HPrs (Fig. 7C). These similarities include hydrophobic aliphatic residues, i.e., Ala16 and Leu22 in helix α1 and Met, Ile, or Leu at positions 48 and 51 in helix α2. Moreover, Ala or Gly residues are present at positions 49 and 56. In contrast, Gram-negative HPrs contain Phe at positions 22 and 48, Thr at positions 16 and 56, Lys at position 49, and Gln at position 51. In conclusion, hydrophobic aliphatic residues, in particular in α-helix 2, are the likely features that allow NPr to phosphorylate PRD2 of LicT. The aromatic and polar residues present at the corresponding positions in HPr of E. coli may prevent interaction with PRD2, but at the same time they trigger efficient interaction with PRD1 of LicT. Thus, subtle differences in the interaction surface decide whether HPr preferentially phosphorylates PRD2 or the homologous PRD1, switching it from an activator to an inhibitor of LicT activity.

It has been speculated for several antitermination proteins from B. subtilis that phosphorylation of PRD1 is catalyzed by HPr and that the cognate EII modulates this reaction in response to substrate availability. This hypothesis is also supported by our observation that LicT becomes efficiently phosphorylated at PRD1 by HPr of E. coli. Thus, it is conceivable that the previously observed phosphorylation of PRD1 by the cognate HPr protein in vitro (see the introduction) reflects HPr's natural ability to also carry out this reaction in vivo. A plausible mechanism may involve binding of the antitermination protein by the phosphorylated form of the cognate EII and its presentation in a manner that increases the affinity of HPr for PRD1. Indeed, EIIBgl-dependent membrane sequestration has been reported for BglG from E. coli (23, 39). Alternatively, phosphorylation of PRD1 by HPr could be an evolutionary relic reflecting the phylogeny of the antitermination proteins. It is conceivable that an ancestral antitermination protein was only negatively controlled by HPr-mediated phosphorylation of a single “PRD.” Perhaps, this protein controlled synthesis of EI and HPr (as observed for GlcT in recent Firmicutes) and of a prototypical EII. This antitermination protein would only be active during sugar transport, which would cause withdrawal of the inhibitory phosphoryl groups from PRD1 via HPr to the EII, a behavior similar to that observed here for LicT in E. coli (Table 3). This simple feedback loop would have coupled synthesis of the PTS proteins to substrate availability. The acquisition of additional EIIs during evolution required an additional substrate-specific regulation mechanism to avoid unspecific activation by transport of any PTS substrate. The EIIB domains could have taken over the task to phosphorylate PRD1, and the cognate HPr proteins progressively lost this ability, while it was still retained by noncognate HPrs, as observed in the present study. Although not homologous, the interaction surfaces of HPr and the EIIB domains share similar topologies, as also reflected by their common ability to interact with EIIA domains. Thus, such a phylogeny appears plausible from a structural point of view as well.

The pivotal role of EI and HPr at the top of the PTS phosphorylation cascade, their important physiological roles, and their dissimilarities to eukaryotic proteins make these proteins attractive potential targets for antimicrobial chemotherapy. EI-deficient mutants of several human pathogens have been shown to be attenuated in mice (11, 32, 60). Previous studies had already shown that LicT is inactive in wild-type E. coli but active in mutants lacking HPr and/or EI (21, 27). It was proposed that this gain of function in response to the loss of EI/HPr activity makes LicT an excellent reporter for high-throughput screening of inhibitors of the general PTS enzymes EI and HPr in living E. coli cells (27). Although the principal design of this system is appealing, the findings here reveal a hitherto-hidden Achilles heel. The transport PTS and PTSNtr are highly homologous systems and can even exchange phosphoryl groups under certain conditions (49, 72). Thus, compounds that inhibit the EI autophosphorylation cycle or the subsequent phosphoryl group transfer to HPr may also inhibit the homologous protein of PTSNtr. As a consequence, reporter readout would be negative, and the respective compounds would escape their identification. However, using LicT mutants with the His→Asp exchanges in PRD2 rather than the wild-type LicT would circumvent this problem, because it would make PTSNtr activity irrelevant for reporter readout.

Most importantly, our results demonstrate that the LicT-based reporter system is a useful tool for the identification and investigation of regulators of the phosphorylation state of PTSNtr in E. coli and perhaps other Proteobacteria. Little is known about the phosphorylation state of PTSNtr in E. coli and how it might be controlled. Here, we show that EIIANtr is present almost completely in its phosphorylated form in wild-type cells grown under standard conditions in minimal glucose medium (Fig. 6). This suggests the existence of so-far-unknown conditions able to inhibit the PTSNtr phosphorylation cascade and to increase the concentration of dephosphorylated EIIANtr, which finally regulates synthesis and activities of K+ transporters and perhaps other functions. Interestingly, EINtr carries an N-terminal GAF signaling domain, which could modulate activity of the full-length protein in response to binding of an unknown ligand, either a metabolite or a protein (45). By using LicT as a tool, we identified the protein SspA as a regulator of the phosphorylation state of EIIANtr. In sspA mutants, LicT was less active, and at the same time phosphorylation of EIIANtr was inhibited, at least partially. Thus, SspA is required for full EINtr autophosphorylation activity and/or efficient phosphorylation of NPr. SspA is highly conserved in Gram-negative bacteria and was shown to play an important role in the acid stress response by activating expression of the transcription factor GadE, which is crucial for acid resistance (26). On the other hand, K+ plays a pivotal role in regulation of intracellular pH (18). Thus, one possibility is that PTSNtr regulates K+ uptake in response to acid stress, which could involve its interaction with SspA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grant GO1355/7-1 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to B.G. and by the DFG Graduiertenkolleg “Biochemie der Enzyme” (W.M., T.B., and B.R.). T.B. was supported by a stipend of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

Elge Koalick is thanked for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 18 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amster-Choder O., Wright A. 1997. BglG, the response regulator of the Escherichia coli bgl operon, is phosphorylated on a histidine residue. J. Bacteriol. 179:5621–5624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnaud M., et al. 1992. Regulation of the sacPA operon of Bacillus subtilis: identification of phosphotransferase system components involved in SacT activity. J. Bacteriol. 174:3161–3170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Attwood P. V., Piggott M. J., Zu X. L., Besant P. G. 2007. Focus on phosphohistidine. Amino Acids 32:145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baba T., et al. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barabote R., Saier M., Jr 2005. Comparative genomic analyses of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:608–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bender J., Kleckner N. 1992. IS10 transposase mutations that specifically alter target site recognition. EMBO J. 11:741–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Besant P. G., Attwood P. V., Piggott M. J. 2009. Focus on phosphoarginine and phospholysine. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 10:536–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bettenbrock K., et al. 2007. Correlation between growth rates, EIIACrr phosphorylation, and intracellular cyclic AMP levels in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 189:6891–6900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curtis S. J., Epstein W. 1975. Phosphorylation of D-glucose in Escherichia coli mutants defective in glucose phosphotransferase, mannose phosphotransferase, and glucokinase. J. Bacteriol. 122:1189–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delrue R. M., Lestrate P., Tibor A., Letesson J. J., De Bolle X. 2004. Brucella pathogenesis, genes identified from random large-scale screens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Demene H., et al. 2008. Structural mechanism of signal transduction between the RNA-binding domain and the phosphotransferase system regulation domain of the LicT antiterminator. J. Biol. Chem. 283:30838–30849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Reuse H., Danchin A. 1988. The ptsH, ptsI, and crr genes of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system: a complex operon with several modes of transcription. J. Bacteriol. 170:3827–3837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deutscher J. 2008. The mechanisms of carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deutscher J., Francke C., Postma P. W. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:939–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diederich L., Rasmussen L. J., Messer W. 1992. New cloning vectors for integration in the lambda attachment site attB of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Plasmid 28:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dozot M., et al. 2010. Functional characterization of the incomplete phosphotransferase system (PTS) of the intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. PLoS One 5:e12679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Epstein W. 2003. The roles and regulation of potassium in bacteria. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 75:293–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fuhrmann J., et al. 2009. McsB is a protein arginine kinase that phosphorylates and inhibits the heat-shock regulator CtsR. Science 324:1323–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Görke B. 2003. Regulation of the Escherichia coli antiterminator protein BglG by phosphorylation at multiple sites and evidence for transfer of phosphoryl groups between monomers. J. Biol. Chem. 278:46219–46229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Görke B. 2000. Signal transduction at the bgl operon of Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis. Biology III, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 22. Görke B., Rak B. 1999. Catabolite control of Escherichia coli regulatory protein BglG activity by antagonistically acting phosphorylations. EMBO J. 18:3370–3379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Görke B., Rak B. 2001. Efficient transcriptional antitermination from the Escherichia coli cytoplasmic membrane. J. Mol. Biol. 308:131–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Görke B., Stülke J. 2008. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:613–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graille M., et al. 2005. Activation of the LicT transcriptional antiterminator involves a domain swing/lock mechanism provoking massive structural changes. J. Biol. Chem. 280:14780–14789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hansen A. M., et al. 2005. SspA is required for acid resistance in stationary phase by downregulation of H-NS in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 56:719–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hesterkamp T., Erni B. 1999. A reporter gene assay for inhibitors of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:309–317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hogema B. M., et al. 1998. Inducer exclusion in Escherichia coli by non-PTS substrates: the role of the PEP to pyruvate ratio in determining the phosphorylation state of enzyme IIAGlc. Mol. Microbiol. 30:487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hogema B. M., Arents J. C., Bader R., Postma P. W. 1999. Autoregulation of lactose uptake through the LacY permease by enzyme IIAGlc of the PTS in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1825–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joanny G., et al. 2007. Polyadenylation of a functional mRNA controls gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:2494–2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kalamorz F., Reichenbach B., März W., Rak B., Görke B. 2007. Feedback control of glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase GlmS expression depends on the small RNA GlmZ and involves the novel protein YhbJ in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1518–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kok M., Bron G., Erni B., Mukhija S. 2003. Effect of enzyme I of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) on virulence in a murine model. Microbiology 149:2645–2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krüger S., Hecker M. 1995. Regulation of the putative bglPH operon for aryl-beta-glucoside utilization in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:5590–5597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee C.-R., et al. 2010. Potassium mediates Escherichia coli enzyme IIANtr-dependent regulation of sigma factor selectivity. Mol. Microbiol. 78:1468–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee C. R., Cho S. H., Yoon M. J., Peterkofsky A., Seok Y. J. 2007. Escherichia coli enzyme IIANtr regulates the K+ transporter TrkA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:4124–4129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levy S., Zeng G. Q., Danchin A. 1990. Cyclic AMP synthesis in Escherichia coli strains bearing known deletions in the pts phosphotransferase operon. Gene 86:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lindner C., Galinier A., Hecker M., Deutscher J. 1999. Regulation of the activity of the Bacillus subtilis antiterminator LicT by multiple PEP-dependent, enzyme I- and HPr-catalysed phosphorylation. Mol. Microbiol. 31:995–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindner C., Hecker M., Le Coq D., Deutscher J. 2002. Bacillus subtilis mutant LicT antiterminators exhibiting enzyme I- and HPr-independent antitermination affect catabolite repression of the bglPH operon. J. Bacteriol. 184:4819–4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lopian L., Nussbaum-Shochat A., O'Day-Kerstein K., Wright A., Amster-Choder O. 2003. The BglF sensor recruits the BglG transcription regulator to the membrane and releases it on stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7099–7104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lopilato J., Bortner S., Beckwith J. 1986. Mutations in a new chromosomal gene of Escherichia coli K-12, pcnB, reduce plasmid copy number of pBR322 and its derivatives. Mol. Gen. Genet. 205:285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lüttmann D., et al. 2009. Stimulation of the potassium sensor KdpD kinase activity by interaction with the phosphotransferase protein IIANtr in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 72:978–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pflüger K., de Lorenzo V. 2008. Evidence of in vivo cross talk between the nitrogen-related and fructose-related branches of the carbohydrate phosphotransferase system of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 190:3374–3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pflüger K., di Bartolo I., Velazquez F., de Lorenzo V. 2007. Non-disruptive release of Pseudomonas putida proteins by in situ electric breakdown of intact cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 71:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pflüger-Grau K., Görke B. 2010. Regulatory roles of the bacterial nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system. Trends Microbiol. 18:205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Plumbridge J. 1999. Expression of the phosphotransferase system both mediates and is mediated by Mlc regulation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33:260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Plumbridge J. 2002. Regulation of gene expression in the PTS in Escherichia coli: the role and interactions of Mlc. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Postma P. W., Lengeler J. W., Jacobson G. R. 1993. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:543–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Powell B. S., et al. 1995. Novel proteins of the phosphotransferase system encoded within the rpoN operon of Escherichia coli. Enzyme IIANtr affects growth on organic nitrogen and the conditional lethality of an erats mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 270:4822–4839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rabus R., Reizer J., Paulsen I., Saier M. H., Jr 1999. Enzyme INtr from Escherichia coli. A novel enzyme of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system exhibiting strict specificity for its phosphoryl acceptor, NPr. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26185–26191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ramseier T. M., Bledig S., Michotey V., Feghali R., Saier M. H., Jr 1995. The global regulatory protein FruR modulates the direction of carbon flow in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1157–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Reichenbach B., Breustedt D. A., Stülke J., Rak B., Görke B. 2007. Genetic dissection of specificity determinants in the interaction of HPr with enzymes II of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:4603–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sankar T. S., et al. 2009. Fate of the H-NS-repressed bgl operon in evolution of Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schmalisch M. H., Bachem S., Stülke J. 2003. Control of the Bacillus subtilis antiterminator protein GlcT by phosphorylation. Elucidation of the phosphorylation chain leading to inactivation of GlcT. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51108–51115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schnetz K., et al. 1996. LicT, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator protein of the BglG family. J. Bacteriol. 178:1971–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schnetz K., Toloczyki C., Rak B. 1987. Beta-glucoside (bgl) operon of Escherichia coli K-12: nucleotide sequence, genetic organization, and possible evolutionary relationship to regulatory components of two Bacillus subtilis genes. J. Bacteriol. 169:2579–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sprenger G. A., Lengeler J. W. 1988. Analysis of sucrose catabolism in Klebsiella pneumoniae and in Scr+ derivatives of Escherichia coli K12. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:1635–1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stentz R., Lauret R., Ehrlich S. D., Morel-Deville F., Zagorec M. 1997. Molecular cloning and analysis of the ptsHI operon in Lactobacillus sake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2111–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stülke J., Arnaud M., Rapoport G., Martin-Verstraete I. 1998. PRD: a protein domain involved in PTS-dependent induction and carbon catabolite repression of catabolic operons in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 28:865–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sun Y. H., Bakshi S., Chalmers R., Tang C. M. 2000. Functional genomics of Neisseria meningitidis pathogenesis. Nat. Med. 6:1269–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tortosa P., et al. 1997. Multiple phosphorylation of SacY, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator negatively controlled by the phosphotransferase system. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17230–17237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tortosa P., et al. 2001. Sites of positive and negative regulation in the Bacillus subtilis antiterminators LicT and SacY. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1381–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Uzzau S., Figueroa-Bossi N., Rubino S., Bossi L. 2001. Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:15264–15269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]