Abstract

Type VI secretion systems (T6SS) are bacteriophage-derived macromolecular machines responsible for the release of at least two proteins in the milieu, which are thought to form an extracellular appendage. Although several T6SS have been shown to be involved in the virulence of animal and plant pathogens, clusters encoding these machines are found in the genomes of most species of Gram-negative bacteria, including soil, marine, and environmental isolates. T6SS have been associated with several phenotypes, ranging from virulence to biofilm formation or stress sensing. Their various environmental niches and large diversity of functions are correlated with their broad variety of regulatory mechanisms. Using a bioinformatic approach, we identified several clusters, including those of Vibrio cholerae, Aeromonas hydrophila, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato, and a Marinomonas sp., which possess typical −24/−12 sequences, recognized by the alternate sigma factor sigma 54 (σ54 or σN). σ54, which directs the RNA polymerase to these promoters, requires the action of a bacterial enhancer binding protein (bEBP), which binds to cis-acting upstream activating sequences. Putative bEBPs are encoded within the T6SS gene clusters possessing σ54 boxes. Using in vitro binding experiments and in vivo reporter fusion assays, we showed that the expression of these clusters is dependent on both σ54 and bEBPs.

INTRODUCTION

A large number of macromolecular systems are involved in bacterial pathogenesis. These systems include adhesion factors or organelles required for the secretion of toxin proteins. Among them, type VI secretion systems (T6SS) were first identified in 2006 in a screen for identifying bacterial factors necessary for Vibrio cholerae resistance to amoeba predation (40). Since then, T6SS have been characterized or described for many Gram-negative bacteria, including animal and human pathogens (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia species, pathogenic Escherichia coli, Francisella tularensis, Salmonella enterica), plant pathogens (Pectobacterium atrosepticum, Pseudomonas syringae, Agrobacterium tumefaciens), and fish pathogens (Edwardsiella tarda) as well as for soil, marine, and environmental bacteria (2, 15, 32, 36, 38, 42, 45, 48). They are thus widely distributed in a broad spectrum of bacteria in a wide range of environmental niches, but they are also involved in a broad diversity of processes (6, 12, 17, 41, 46, 47). Although necessary for E. tarda or Francisella pathogenesis, T6SS are required for processes as different as resisting predation in Vibrio cholerae, symbiosis in Rhizobium leguminosarum, biofilm formation in enteroaggregative E. coli, killing of niche competitors in P. aeruginosa, Burkholderia thailandensis, and Vibrio cholerae, and stress sensing in Vibrio anguillarum (for a recent review, see reference 46) (2, 7, 21, 30, 34, 40, 47, 60, 66).

This broad variety of environments and functions is reflected by a large diversity in the regulatory mechanisms: the expression of T6SS gene clusters is usually induced in the presence of host cells, of host cell extracts, or in medium mimicking their environment (5). Several regulatory mechanisms controlling T6SS gene cluster expression have been identified in recent years: they are regulated at the transcriptional level by alternate sigma factors, two-component systems, or transcriptional factors. Several cases of regulation by quorum sensing have also been reported. Because T6SS gene clusters are often found in pathogenicity islands or have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer, their GC content is sometimes different from the GC content of the core genome, and they are silenced by histone-like proteins. T6SS subunit production is also regulated at the translational level through the action of small regulatory RNA, and several T6SS need to be activated by posttranslational mechanisms (for a recent review, see reference 5).

In this paper, we report the characterization of the regulatory mechanism underlying the expression of T6SS gene clusters from V. cholerae, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, Aeromonas hydrophila, and a Marinomonas sp. For these clusters, we first identified genes encoding putative bacterial enhancer binding proteins (bEBPs; pfam family PF00158). bEBPs are ATP-dependent activators of the alternate sigma factor σ54 (10, 43, 49, 62, 64). σ54 (or σN), encoded by the rpoN gene, recognizes and binds consensus sequences centered at −24 and −12 upstream of the +1 transcriptional start. σ54 recruits the RNA polymerase (RNAP; E) to these specific promoters, allowing the formation of the closed complex; however, the Eσ54 complex cannot proceed to the open complex, and DNA melting is induced by the energy provided by the bEBP-dependent ATP hydrolysis (10, 62). bEBPs bind at cis-acting activating sequences usually located at ∼100 to 400 bp from the σ54 binding box, and they interact with the σ54 subunit through DNA bending (facilitated by the integration host factor [IHF]) (62).

Using bioinformatic analyses, we identified putative σ54 binding boxes in the promoter regions of the T6SS gene clusters encoding putative bEBPs (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, a transposon insertion in the rpoN gene has been obtained in the same screen that identified the T6SS gene cluster in V. cholerae (40). Recent studies showed that the production of A. hydrophila T6SS subunits is abolished in a strain with a deletion of the vasH gene, encoding the bEBP (51, 52). However, conflicting data have been recently reported in the case of V. cholerae; Ishikawa and colleagues showed that production of the Hcp protein is decreased to undetectable levels in an rpoN strain, suggesting that σ54 is a positive regulator of the hcp gene (22). In contrast, Syed and colleagues reported a negative effect of σ54 in the regulatory mechanism of the V. cholerae T6SS gene cluster (53). This discrepancy can be probably explained by the difference in the strain background, since the strain used in the latter study is devoid of the hapR gene, a transcriptional activator involved in the regulation of the T6SS gene cluster and the hcp gene (22, 53). In fact, T6SS are usually subject to complicated regulatory networks that involve transcriptional factors, quorum-sensing molecules and regulators, and various signals (5, 27). Due to cross-talk and feedback loops between these different regulators, indirect effects might occur. To bypass these pathways and avoid indirect regulatory effects, we tested the requirement for σ54 and cognate bEBP in T6SS gene cluster regulation in in vivo reconstitution assays using the heterologous host model Escherichia coli. Using reporter fusion assays, we first show that expression of the V. cholerae, A. hydrophila, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, and Marinomonas MWYL1 T6SS gene clusters are controlled by σ54 and cognate bEBP. We provide evidence for in vitro autophosphorylation of bEBPs and demonstrate binding of σ54 and cognate bEBP to the promoter regions by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, chemicals, media, and growth conditions.

The Escherichia coli strain W3110 and its uidA and rpoN derivatives were used throughout the study. The E. coli DH5α strain was used for cloning procedures. BL21(DE3) was used for protein production. The E. coli, Vibrio cholerae O395, and Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC7966 strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C. Pectobacterium atrosepticum SCRI1043 was grown in LB medium at 30°C, whereas Marinomonas sp. MWYL-1 was grown in LB medium supplemented with 5% sodium chloride at 30°C. Genomic DNA from these strains was prepared using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). Acetyl-phosphate and para-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Purified RNAP core enzyme was obtained from Epicentre Biotechnology. [32P]Orthophosphate (phosphorus) was purchased from PerkinElmer.

Strain construction.

The W3110 uidA::Kanr strain was obtained by P1 bacteriophage transduction from BW25113 uidA::Kanr (Keio collection) (4). The kanamycin cassette was then excised using the pCP20 plasmid as described previously (14) to yield W3110ΔuidA. The W3110ΔuidAΔrpoN strain was obtained similarly, by P1 transduction from the BW25113 rpoN::Kanr strain and cassette excision.

Plasmid construction.

PCRs were performed with a Biometra thermocycler, using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Plasmids (listed in Table 1) were constructed by a double PCR technique, allowing amplification of the gene or promoter of interest flanked by extensions annealing to the target vector (3, 58). The products of the first PCR were then used as oligonucleotides for a second PCR using the target vector as the template (custom oligonucleotides, synthesized by Eurogentec, are listed in Table 2). For uidA transcriptional fusions, the promoter sequences were amplified from genomic DNA and cloned downstream of the T7 promoter into the pT7.7 vector (54). The uidA gene, encoding β-glucuronidase, has then been cloned downstream of each promoter. For bEBP-producing plasmids, the gene encoding the bacterial enhancer binding protein fused to an N-terminal FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK) has been amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into the pOK12 vector (59) downstream of the lac promoter. For protein purification, genes encoding the E. coli σ54 protein and the various bEBPs were amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into the pET19b plasmid (Novagen). The production of the protein fused to an N-terminal 10-histidine tail is then controlled by the T7 promoter. All constructs were verified by restriction analyses and DNA sequencing (Genome Express).

Table 1.

Plasmids constructed for this study

| Plasmid category (vector)a and name | Description |

|---|---|

| uidA transcriptional fusion (pT7.7) | |

| pPglnA | Escherichia coli glnA (GenBank accession no. AP_003938) promoter (379 bp, starting at position −376 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPVCA0107 | Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion gene cluster (VCA0107; accession no. NP_232508) promoter (390 bp, starting at position −387 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPVCA0017 | Vibrio cholerae hcp-vgrG operon (VCA0017; accession no. NP_232418) promoter (397 bp, starting at position −394 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPECA3445 | Pectobacterium atrosepticum type VI secretion gene cluster (ECA3445; accession no. YP_051535) promoter (604 bp, starting at position −601 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPECA2866 | Pectobacterium atrosepticum hcp-vgrG operon (ECA2866; accession no. YP_050957) promoter (326 bp, starting at position −323 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPECA4275 | Pectobacterium atrosepticum hcp-vgrG operon (ECA4275; accession no. YP_052352) promoter (730 bp, starting at position −727 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPAHA1826 | Aeromonas hydrophila type VI secretion gene cluster (AHA_1826; accession no. YP_856360) promoter (606 bp, starting at position −603 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPMWYL1196 | Marinomonas sp. MWYL1 type VI secretion gene cluster, operon 1 (Mar-1) (Mmwyl1_1196; accession no. YP_001340060) promoter (744 bp, starting at position −741 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| pPMWYL1195 | Marinomonas sp. MWYL1 type VI secretion gene cluster, operon 2 (Mar-2) (Mmwyl1_1195; accession no. YP_001340059) promoter (744 bp, starting at position −741 from the AUG start codon) upstream of the uidA gene |

| Epitope-tagged EBP production (pOK12) | |

| pOK-NtrC | Escherichia coli ntrC gene (accession no. AP_003940) |

| pOK-VCA0117 | Vibrio cholerae vasH gene (VCA0117; accession no. NP_232518) |

| pOK-ECA3435 | Pectobacterium atrosepticum vasH gene (ECA3435; accession no. YP_051525) |

| pOK-AHA1842 | Aeromonas hydrophila vasH gene (AHA_1842; accession no. YP_856376) |

| pOK-MWYL1206 | Marinomonas sp. MWYL1 vasH gene (Mmwyl1_1206; accession no. YP_001340070) |

| Protein purification (pET19b) | |

| pET-RpoN | Escherichia coli rpoN gene (accession no. AP_003745) |

| pET-NtrC | Escherichia coli ntrC gene (accession no. AP_003940) |

| pET-VCA0117 | Vibrio cholerae vasH gene (VCA0117; accession no. NP_232518) |

| pET-ECA3435 | Pectobacterium atrosepticum vasH gene (ECA3435; accession no. YP_051525) |

| pET-AHA1842 | Aeromonas hydrophila vasH gene (AHA_1842; accession no. YP_856376) |

| pET-MWYL1206 | Marinomonas sp. MWYL1 vasH gene (Mmwyl1_1206; accession no. YP_001340070) |

Plasmids within each category were cloned in the indicated vector (shown in parentheses) for that category.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide purpose and name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Promoter insertion in pT7.7a and gel shift expts | |

| PglnA | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCGCCTCAGGCATTAGAAATAGCGCGTTATTG |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCCATACTTTAACTCTCCTGGATTGGTCATGGTC | |

| PVCA0107 | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCGGGGTAAAAGATCACGCTTCGGG |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCCATATTACGTCTCCAATACCTATGCCAAACG | |

| PVCA0017 | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCTTCCCGTTTGTCGTTATATACCTTTCCTAC |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCTATTTCCTTTCAATAAATCATTTTTAAGTCAATG | |

| PECA3445 | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCCCTTAATTTGTTAGCGGGTTAAGTATTTCGTTG |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCCATGTGTCTATACCAACGTAAGGGCACTCG | |

| PECA2866 | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCTGATATTGATAAATTTATGAGGATATCCTCCCCATTC |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCAGTCTTGCTCCTTGTTGTTGAACGTGATG | |

| PECA4275 | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCACCGGCAAGTATCAGCAATAAGTGTTTC |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCGGAGTTGGCATAGTGTTGCTCCTTGTTG | |

| PAHA1826 | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCGCGAAGGGCAGGGAACATAGAGCC |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCCATGGGTATGCTCCTGATTGGTTGAACG | |

| PMWYL1196 (Mar-1) | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCATACTTTTCTCCATCCAACGACGTC |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCATAGTAAAATTCCTTATTTAAAAATAGTAAAAACGTG | |

| PMWYL1195 (Mar-2) | CTCACTATAGGGAGACCGGAATTCGAGCTCATAGTAAAATTCCTTATTTAAAAATAGTAAAAACGTG |

| GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCATACTTTTCTCCATCCAACGACGTC | |

| uidA | GCGCGGGGATCCTCTAGAGTCGACCATGTTACGTCCTGTAGAAACCCCAACCCG |

| ACAGCTTATCATCGATAAGCTTGGGCTGCATCATTGTTTGCCTCCCTGCTGCGG | |

| EBP insertion in pOK12a,b | |

| NtrC | GGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGGACTACAAAGACGACGATGACAAGCAACGAGGGATAGTCTGGGTAGTCG |

| GGCCTCGGACTAGTGGCGTAATCATGGTCACTCCATCCCCAGCTCTTTTAACTTAC | |

| VCA0117 | GGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGGACTACAAAGACGACGATGACAAGAGTCAATGGCTGGCGTTTGCAACC |

| GGCCTCGGACTAGTGGCGTAATCATGGTCATGGGGTTTTGATCTCCAATTTCAGG | |

| ECA3435 | GGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGGACTACAAAGACGACGATGACAAGCAACATGCCCTCAAACTGGCGCTAG |

| GGCCTCGGACTAGTGGCGTAATCATGGTCAATTCACCTCCAGCTTCTGGCATTTG | |

| AHA1842 | GGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGGACTACAAAGACGACGATGACAAGGAGCAAGCCCTCGCATTTTCCCTG |

| GGCCTCGGACTAGTGGCGTAATCATGGTCAGTTCACCTCCAGTTTCTGGCACTTG | |

| MWYL1206 | GGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGGACTACAAAGACGACGACGATAAATGGCTTAAGTCTGCAGCTGAGTTGG |

| GGCCTCGGACTAGTGGCGTAATCATGGTCTAATCATTTATGGAAATCTCCAATTTCAAACAC | |

| RpoN and EBP insertion in pET19ba | |

| RpoN | GCGGCCATATCGACGACGACGACAAGAAGCAAGGTTTGCAACTCAGGCTTAGCC |

| GTTAGCAGCCGGATCCTCGAGCATATGTCAAACGAGTTGTTTACGCTGGTTTGACG | |

| NtrC | GGCCATATCGACGACGACGACAAGCAACGAGGGATAGTCTGGGTAGTCGATG |

| GCAGCCGGATCCTCGAGCATATGTCACTCCATCCCCAGCTCTTTTAACTTAC | |

| VCA0117 | GGCCATATCGACGACGACGACAAGAGTCAATGGCTGGCGTTTGCAACC |

| GCAGCCGGATCCTCGAGCATATGTCATGGGGTTTTGATCTCCAATTTCAGG | |

| ECA3435 | GGCCATATCGACGACGACGACAAGCAACATGCCCTCAAACTGGCGCTAG |

| GCAGCCGGATCCTCGAGCATATGTCAATTCACCTCCAGCTTCTGGCATTTG | |

| AHA1842 | GGCCATATCGACGACGACGACAAGGAGCAAGCCCTCGCATTTTCCCTG |

| GCAGCCGGATCCTCGAGCATATGTCAGTTCACCTCCAGTTTCTGGCACTTG | |

| MWYL1206 | GGCCATATCGACGACGACGACAAGAATAACTGGCTTAAGTCTGCAGCTGAGTTGGTG |

| GCAGCCGGATCCTCGAGCATATGCTAATCATTTATGGAAATCTCCAATTTCAAACAC | |

| Consensus boxes for competition exptsc | |

| RpoN | TATGCCGAAGGGTGGCACGATGATTGCATATGCCG |

| CGGCATATGCAATCATCGTGCCACCCTTCGGCATA | |

| Fur | TATGCCGGATAATGATAATCATTATCTATGCCG |

| CGGCATAGATAATGATTATCATTATCCGGCATA |

Sequence complementary to the target vector is underlined.

The FLAG tag coding sequence is italicized.

The consensus sequence is underlined.

β-Glucuronidase assays.

β-Glucuronidase enzyme activity was measured from cells in mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.6) as previously described (23). Briefly, 0.2 ml of cell culture was mixed with 0.8 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 7.0], 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100) and lysed by the addition of one drop of 0.1% SDS and two drops of chloroform. After vigorous vortexing, the cell extracts were diluted four times in Z buffer, and β-glucuronidase activity (release of para-nitrophenol) was monitored at 405 nm after the addition of para-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide (Sigma-Aldrich; 10 mM final concentration). The specific β-glucuronidase activity was expressed in Miller units. Each enzymatic assay was performed in triplicate, starting from each biological triplicate (from independent plasmid transformations).

Protein purification.

The E. coli σ54 protein and the bEBPs from the various species were purified as follows. Proteins were produced in BL21(DE3) carrying the corresponding pET19b derivative, by T7 polymerase gene induction using 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 22°C. Despite optimization of the production conditions, bEBPs always remained in inclusion bodies. bEBPs were therefore solubilized and purified in the presence of urea as described below. Cells were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–100 mM NaCl (TN buffer) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete EDTA-free; Roche) and 8 M urea. Cells were then lysed by the addition of lysozyme (100 μg/ml) and the use of a French press. After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation for 45 min at 90,000 × g, histidine-tagged proteins were immobilized on a ion metal affinity chromatography resin (Cobalt Talon resin; Clontech) preequilibrated in TN buffer supplemented with urea. Proteins were eluted by using an imidazole gradient, and the fractions containing concentrated and pure proteins were pooled and dialyzed stepwise against TN buffer containing 6 M, 4 M, and 2 M urea and no urea. At this step, a large portion of the bEBPs precipitated and were removed by ultraspeed centrifugation (15 min at 30,000 × g). The Fur protein was purified from plasmid pBT4-1 (55) as previously published (55). The Fur protein was shown to be functional in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay using the Fur-dependent Escherichia coli K-12 cirA promoter as the probe (data not shown). The purity of each protein was estimated to be >95% based on Coomassie blue staining. The concentration of each protein was determined by the absorbance at 280 nm using theoretical molar extinction coefficients calculated using an ExPASy website tool (http://www.expasy.ch/tools/protparam.html).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

32P-Labeled probes were obtained by PCR amplification of the promoter sequences from chromosomal DNA using dNTP mixes containing [α-32P]deoxyadenosine triphosphate. Labeled probes were column purified (Wizard SV gel and PCR cleanup kit; Promega) to remove radioactive nucleotides. Gel shift experiments were carried out with soluble bEBPs and with reconstituted Eσ54. DNA binding activity of Eσ54 was measured as previously described (11, 50, 56). Briefly, 32P-labeled probes were mixed with Eσ54 (premixed as an RNAP core enzyme at a σ54 ratio of 1:2) in STA buffer (25 mM Tris-acetate [pH 8.0], 8 mM magnesium acetate, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 3.5% PEG 6000) in the presence of sonicated salmon sperm DNA (10 μg/ml) and bovine serum albumin (BSA; 50 μg/ml). Controls include incubation with RNAP core enzyme or with double-stranded DNA competitors (consensus σ54 and Fur binding boxes obtained by the annealing of two complementary oligonucleotides; Table 2). Binding of bEBPs to the promoters was tested by adaptation of previously described protocols (13, 24, 57). Purified bEBPs were mixed with 32P-labeled promoter probes in a binding reaction mixture containing sonicated salmon sperm DNA (10 μg/ml), BSA (100 μg/ml), 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM potassium acetate, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, and 10 mM acetyl-phosphate in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9). After the 20-min binding step, samples were resolved using a prerun 9% acrylamide gel in Tris-borate buffer. Gels were fixed in 10% trichloroacetic acid for 10 min and exposed to Kodak BioMax MR films.

In vitro phosphorylation.

Acetyl-[32P]phosphate was synthesized as previously described (33). Phosphorylation assays were performed as previously described (16, 29) with minor modifications. Briefly, 10 μg of protein was incubated for 30 min in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 5 mM acetyl-[32P]phosphate. The reaction was quenched by the addition of loading buffer, and the proteins were subjected to electrophoresis using a 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, autoradiographed, and then immunodetected with anti-His monoclonal antibody.

Miscellaneous.

For detection by immunostaining, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and blots were probed with anti-PentaHis (Qiagen) or M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich) monoclonal antibodies and anti-mouse secondary antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase and developed using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium.

RESULTS

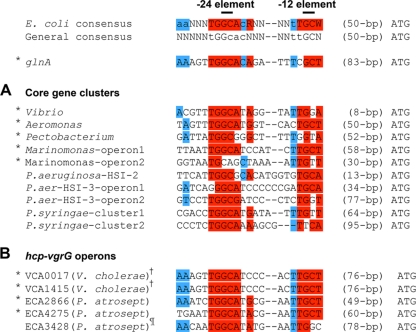

Identification of σ54 binding boxes.

To identify T6SS gene clusters potentially controlled by σ54, we performed a survey using the BProm algorithm (SoftBerry). The putative σ54-dependent T6SS promoter list includes T6SS gene clusters from Vibrio cholerae, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, Aeromonas hydrophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (HSI-2 and HSI-3), P. syringae pv. tomato (two clusters), and a Marinomonas sp. (Fig. 1A) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These promoters were found upstream of the first gene of the cluster, suggesting that all the genes that are organized in the same orientation are part of an operon structure. In one case (Pectobacterium atrosepticum), an additional promoter was identified upstream of the ECA3428 gene, suggesting that the cluster is composed of two operons (see Fig. S1). In the case of T6SS, genes are present within two divergent operons, and a σ54 binding sequence is found in both orientations (P. aeruginosa HSI-3 and the Marinomonas sp.) (see Fig. S1). Interestingly, genes encoding putative bEBPs are present within T6SS gene clusters that share putative σ54 boxes (see Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Alignment of putative σ54 binding sequences within T6SS gene cluster promoters. Putative σ54 promoters identified for T6SS gene clusters (A) or orphan hcp and vgrG genes (B) characterized or discussed in this study are aligned using Clustal W with the E. coli σ54 binding sequence consensus (upper line) (44). The promoters of the T6SS gene clusters are PVCA0107 (Vibrio cholerae), PECA3445 (Pectobacterium atrosepticum [P. atrosept]), PAHA1826 (Aeromonas hydrophila), PMWYL1196 (Marinomonas sp., operon 1), PMWYL1195 (Marinomonas sp., operon 2), PPA1656 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa HSI-2), PPA2365 (P. aeruginosa HSI-3, operon 1), PPA2364 (P. aeruginosa HSI-3 [P.aer-HSI-3], operon 2), PPSPTO2541 (P. syringae, cluster 1), PPSPTO5428 (P. syringae, cluster 2) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material for promoter location details). Base conservation in the E. coli consensus is indicated with a color code (red, highly conserved; blue, partly conserved; white, variable base). Promoters characterized in this study are indicated by asterisks. † indicates that these two promoters (VCA0017 and VC1415) are strongly similar (two mismatches along a 200-bp sequence). The region upstream of the ECA3428 gene (encoding an hcp homologue in the main Pectobacterium T6SS gene cluster) also contains a putative σ54 promoter (indicated by ¶).

Activities of transcriptional fusions.

To test whether the type VI secretion gene clusters that share putative σ54 binding sequences are directly regulated by σ54, we used an in vivo reconstitution approach into the heterologous host Escherichia coli. This allowed reducing indirect regulatory effects by other factors, cross-talk, regulatory feedback loops, and growth conditions. We constructed transcriptional fusions, in which the uidA gene, encoding β-glucuronidase, is under the control of the promoter region of the type VI secretion gene cluster of Vibrio cholerae (PVCA0107), Pectobacterium atrosepticum (PECA3445), or Aeromonas hydrophila (PAHA1826). The Marinomonas sp. T6SS genes are distributed in two distinct divergent operons, and σ54 binding sequences are found in both orientations in the promoter region; the region between these two operons has been thus cloned in both orientations (PMWYL1195 and PMWYL1196). Plasmids carrying the transcriptional fusion have been introduced into the E. coli uidA strain or its rpoN derivative, and β-glucuronidase activities have been measured. Figure 2A shows that the fusions have a low level of activity in both backgrounds.

Fig. 2.

T6SS gene clusters are regulated by σ54 and cognate enhancer binding proteins. β-Glucuronidase activity of transcriptional fusions in the Escherichia coli wild type strain (white bars) and its rpoN derivative strains (black bars), in the absence (A) or presence (B) of bEBP ectopic overproduction. The inset in panel B shows the levels of NtrC and T6SS-associated bEBPs produced during the experiments: VCA0117 (V. cholerae), ECA3435 (Pectobacterium atrosepticum), AHA1842 (A. hydrophila) and MWYL1206 (Marinomonas sp.) (immunodetected by the anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody); molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are at the right.

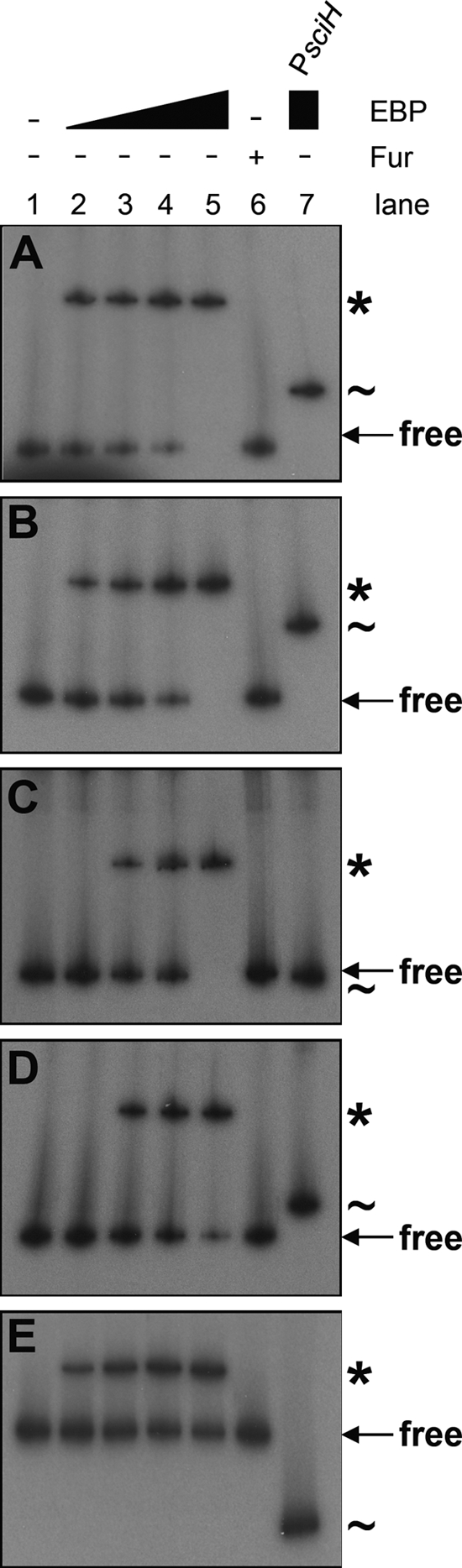

σ54 binds to type VI secretion gene cluster promoters.

We purified the E. coli σ54 protein and tested its ability to interact with the T6SS gene cluster promoters in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Labeled promoters were incubated with increasing concentrations of Eσ54. Several specific controls were included, such as (i) incubation with the RNAP core enzyme (i.e., devoid of σ54), (ii) the use of a specific competitor consisting of a consensus E. coli σ54 binding sequence (tatgccgAAgggTGGCACGatgaTTGCAtatgccg; the consensus sequence is in uppercase) (44), (iii) the use of a nonspecific competitor corresponding to a consensus E. coli Fur binding sequence (tatgccgGATAATGATAATCATTATCtatgccg; the consensus sequence is in uppercase) (55), and (iv) the incubation of Eσ54 with the promoter region of the enteroaggregative E. coli sci1 T6SS gene cluster, which shares a typical σ70 binding sequence. Figure 3 shows that the promoter regions of the various T6SS gene clusters are retarded in the presence of increasing amounts of Eσ54 and that the mobility shifts are abolished in the presence of an excess of the specific cold competitor. Further, the Marinomonas promoter displays two retarded bands (Fig. 3), a result compatible with the presence of two putative σ54 binding boxes regulating the two divergent operons. Taken together, the data reported in Fig. 3 suggest that the promoter regions of these T6SS gene clusters are under the control of σ54.

Fig. 3.

σ54 binds to T6SS gene cluster promoters. Gel shift assays using reconstituted σ54-RNA polymerase complex (Eσ54) (lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 25 nM; lane 3, 100 nM; lane 4, 250 nM) or RNA polymerase core enzyme (E) (lane 5; 250 nM). Competition experiments using double-stranded consensus σ54 binding box (lane 6, molecular ratio [probe/competitor[ of 1:5; lane 7, molecular ratio of 1:25) or nonspecific consensus Fur binding box (lane 8, molecular ratio [probe/competitor] of 1:5; lane 9, molecular ratio of 1:25). (A) E. coli glnA promoter; (B) V. cholerae T6SS gene cluster promoter (PVCA0107); (C) Pectobacterium atrosepticum T6SS gene cluster promoter (PECA3445); (D) A. hydrophila T6SS gene cluster promoter (PAHA1826); (E) Marinomonas MWYL1 T6SS gene cluster promoter (PMWYL1196/PMWYL1195). Retarded probe-Eσ54 complexes are indicated by asterisks. Control with the enteroaggregative E. coli sci1 T6SS gene cluster promoter probe (PsciH; indicated by ∼) is shown (panel A, lane 10, 250 nM). free, labeled promoter probe.

Activities of the transcriptional fusions are dependent on the bEBP.

Activity of σ54-dependent promoter relies on transcriptional activators of the EBP family. We therefore tested whether the bacterial EBPs encoded by the vasH genes enhanced the activities of the transcriptional fusions. The vasH genes from V. cholerae, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, A. hydrophila, and the Marinimonas sp. were cloned in the pOK12 vector under the control of the lac promoter and fused to an N-terminal FLAG epitope coding sequence. Western blot analyses showed that all the bEBPs (VasH) were produced (Fig. 2B, inset). pOK12 is a P15A replicon derivative and thus is compatible with the vector carrying the β-glucuronidase reporter fusions. Figure 2B shows that overproduction of the cognate bEBP increases the activity of the transcriptional fusions of the different T6SS gene clusters 20- to 30-fold. This high expression level is dependent upon the presence of the σ54 alternate factor, since activities of the fusions in the presence of bEBPs are abrogated in the rpoN mutant strain (Fig. 2B). As a control, the activity of the enteroaggregative sci-1 T6SS promoter was shown to be independent of σ54 and of the E. coli NtrC proteins (data not shown). These data confirm that the expression of the V. cholerae, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, A. hydrophila, and Marinimonas T6SS gene clusters is under the control of σ54 and further show that cognate bEBPs are required for activation of transcription.

bEBP autophosphorylation.

In vivo, response regulators are phosphorylated by cognate sensor kinases. In vitro, these response regulators are often capable of autophosphorylation in the presence of small-molecule phosphodonors, such as acetyl-phosphate or carbamyl-phosphate. This characteristic has also been reported for bEBPs, including NtrC (16, 29, 33, 61). We therefore tested whether the T6SS-associated bEBPs are capable of autophosphorylation. E. coli NtrC and the different T6SS bEBPs were purified to homogeneity by ion metal affinity chromatography after solubilization of inclusion bodies with urea (see Materials and Methods). Soluble bEBPs were then incubated in the presence of a low-molecular-mass phosphodonor. Figure 4 shows that the bEBPs from the V. cholerae, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, A. hydrophila, and Marinomonas sp. T6SS were phosphorylated in the presence of acetyl-[32P]phosphate, as was NtrC. As the control, the σ54 protein was not phosphorylated under the same conditions.

Fig. 4.

T6SS-associated bEBPs autophosphorylate. Purified bEBPs from E. coli (NtrC, lane 1), or from V. cholerae (VCA0117; lane 2), Pectobacterium atrosepticum (ECA3435; lane 3), A. hydrophila (AHA1842; lane 4), or Marinomonas (MWYL1206; lane 5) T6SS gene clusters and the E. coli σ54 protein (lane 6), incubated with the low-molecular-weight phosphodonor [32P]acetyl-phosphate were separated by 10% acrylamide SDS-PAGE, blotted, and immunodetected by anti-His antibody (upper panel) or detected by autoradiography (lower panel). Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

Binding of the σ54-dependent activator on type VI secretion gene cluster promoters.

The results of the reporter fusion assays (Fig. 2B) suggest that the bEBPs bind to the T6SS gene cluster promoters to activate their transcription. To test this hypothesis, we performed EMSA using the purified bEBPs. As shown in Fig. 5, the bEBPs specifically bind the promoter region of their cognate T6SS gene cluster. As controls, (i) the purified Fur protein did not retard the different promoters, and (ii) the various bEBPs did not interact with the enteroaggregative E. coli sci-1 promoter.

Fig. 5.

bEBPs bind to T6SS gene cluster promoters. Gel shift assays using purified bEBPs (lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 50 nM; lane 3, 200 nM; lane 4, 400 nM; lane 5, 800 nM) or a specificity control using the purified Fur protein (lane 6, 800 nM). (A) E. coli glnA promoter; (B) V. cholerae T6SS gene cluster promoter (PVCA0107); (C) Pectobacterium atrosepticum T6SS gene cluster promoter (PECA3445); (D) A. hydrophila T6SS gene cluster promoter (PAHA1826); (E) Marinomonas MWYL1 T6SS gene cluster promoter (PMWYL1196/PMWYL1195). Retarded probe-bEBP complexes are indicated by asterisks. Control with the enteroaggregative E. coli sci1 T6SS gene cluster promoter probe (PsciH; indicated by ∼) and each bEBP protein is shown (lane 7, 800 nM).

Orphan hcp and vgrG genes are coregulated with the core T6SS gene cluster.

Our bioinformatic survey indicated that σ54 binding sequences are present in the promoter region of genes encoding Hcp and VgrG subunits when those are isolated elsewhere on the chromosome (Fig. 1B) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The promoter regions of the orphan hcp-vgrG operons from V. cholerae (PVCA0017) and Pectobacterium atrosepticum (PECA2866 and PECA4275) were then cloned and tested for their σ54 and bEBP dependence. Reporter fusion studies demonstrated that the expression of these genes and operons is controlled by σ54 and by the bEBP encoded within the T6S core cluster (Fig. 6A and B). This result was validated by gel shift assays showing that the promoter regions of VCA0017, ECA2866, and ECA4275 are retarded by σ54 (Fig. 6C) and bEBP (Fig. 6D). Together, these results show that orphan hcp and vgrG genes are coregulated with the main T6SS gene cluster.

Fig. 6.

Eσ54 and bEBP bind and regulate orphan hcp and vgrG genes. (A) β-Glucuronidase activity of the indicated transcriptional fusions in the wild-type strain (white bars) and its rpoN derivative strains (black bars), in the absence (upper graph) or presence (lower graph) of bEBP overproduction. (B and C) Gel shift assays with the σ54-RNA polymerase complex (B) or purified bEBP (C) and the V. cholerae hcp-vgrG (PVCA0017, upper panel) or the Pectobacterium atrosepticum hcp-vgrG (PECA2866, middle panel; PECA4275, lower panel) promoters. See legends to Fig. 3 and 5 for details. Retarded complexes are indicated by asterisks.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we used an in vivo reconstitution approach in the heterologous host E. coli and in vitro DNA binding assays to study the role of the alternate sigma factor σ54 in the regulation of several T6SS gene clusters. This allowed us to bypass other regulatory determinants and to specifically study σ54-dependent regulation and the role of bEBP encoded within the T6SS gene clusters. Our results from the reporter fusions show that the bEBP from several microorganisms, such as V. cholerae, A. hydrophila, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, and Marinomonas sp., adapt with the E. coli σ54-RNAP complex. Interactions of a bEBP and a σ54 from two distinct microorganisms have already been demonstrated (50). This is made possible by the high degree of conservation between the σ54 binding region of E. coli bEBPs and the bEBPs used in this study: the central domain, including the GAFTGA sequence, which mediates bEBP binding to σ54, is conserved among all the bEBPs used in this study (8, 43, 49, 65) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Reciprocally, the σ54 region I (residues 15 to 47), which is involved in bEBP recognition, is highly conserved between the E. coli σ54 and the σ54 subunits from the various microorganisms used in this study (11, 63). However, although these specific sequences are conserved among the bEBPs, a sequence alignment between the bEBPs studied in this work and NtrC showed that the N-terminal activation domain and the C-terminal DNA binding domain are the less-conserved regions (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This observation suggests that the T6SS-associated bEBPs respond to different signals and bind different DNA sequences.

Using a combination of reporter fusion and gel shift experiments, we conclude that the expression of the V. cholerae, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, A. hydrophila, and Marinomonas sp. T6SS gene clusters are positively controlled by σ54 and cognate bEBPs. Our results confirm and extend previous studies showing that (i) σ54 and the VasH bEBP are required for expression of the V. cholerae T6SS gene cluster (40), (ii) σ54 is necessary for V. cholerae Hcp production (22), and (iii) the A. hydrophila vasH gene is necessary for T6SS production (51). In the case of the Marinomonas sp., the cluster is distributed into two divergent operons, under the control of a single intergenic sequence which contains two divergent σ54 promoters but probably with a unique binding site for the bEBP. Expression of both operons is σ54 and bEBP dependent. However, we have not yet mapped the bEBP binding UAS sequences in the promoter regions. These cis-acting sequences are often composed of palindromes. Several palindromes can be identified by bioinformatic analyses in these promoters but remain to be experimentally validated by DNase footprint experiments. Interestingly, the identified palindromes do not share sequence similarities, a result which is supported by the differences observed for the helix-turn-helix DNA binding domains of the T6SS-associated bEBPs (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Interaction between Eσ54 and bEBPs is usually facilitated by the action of DNA bending proteins, such as IHF (62). Here again, IHF binding sequences can be identified by in silico approaches, but it remains to be seen how IHF contributes to T6SS regulation.

Our results also showed that Eσ54 and bEBP bind and regulate the expression of orphan hcp and vgrG genes, demonstrating that the core T6SS cluster and accessory elements are coregulated. It is noteworthy that only few proteins secreted by T6SS have been identified. One may hypothesize that the expression of genes encoding protein substrates is coregulated with the main cluster. Indeed, the toxin/antitoxin system secreted through the P. aeruginosa HSI-1 T6SS has been recently shown to be coregulated with the HSI-1 gene cluster (21). Proteome or transcriptome analyses of cells overproducing the enhancer binding protein may thus help to identify coregulated genes and hence putative protein substrates.

Interestingly, the observation that core T6SS gene clusters and orphan hcp and vgrG genes are coregulated raises a new question: do additional specific regulatory mechanisms modulate the expression of the orphan genes to specifically express hcp-vgrG pairs in certain conditions, allowing the bacteria to surface-expose distinct Hcp/VgrG structures, or does a strict coregulation allow the formation of a cocktail of Hcp/VgrG structures? This is an exciting question that will require further investigation.

One striking observation from this study is that σ54-regulated T6SS gene clusters include those of plant pathogen bacteria (Pectobacterium atrosepticum, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato), marine bacteria (Marinomonas sp.), or human environmental pathogens (such as V. cholerae and A. hydrophila, which are ubiquitous inhabitants of brackish water). None of the strict animal or human pathogens, such as pathogenic E. coli or Salmonella, have σ54-dependent promoters, an observation which suggests that this regulatory mechanism has been hijacked by environmental strains. However, the different T6SS gene clusters used in this study are not phylogenetically related (6, 9), suggesting that the σ54-dependent regulation results from a distinct evolution history for adaptation to a specific niche rather than acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. In Gram-negative bacteria, σ54 controls the expression of a number of genes and operons, essentially those involved in nitrogen metabolism or assimilation (44). These genes are induced in nitrogen starvation, a condition which is also found in the soil, in water, or in the plant rhizosphere. One may hypothesize that environmental strains have rerouted a physiological regulatory mechanism to spatially and temporarily induce the expression of virulence or adaptation genes, such as those encoding T6SS. Because of the role of T6SS in bacteria/bacteria interactions (21, 30, 46, 47), it is tempting to hypothesize that this regulatory mechanism may help bacterial colonization in a highly competitive environment, such as the rhizosphere.

A bioinformatic survey of putative σ54-dependent T6SS gene clusters suggests that several other clusters might be regulated by σ54, including those of P. syringae pv. tomato and P. aeruginosa HSI-2 and HSI-3. Other virulence genes of plant pathogens, such as the phytotoxin coronatine, the alginate biosynthesis pathway, and the type III secretion system in P. syringae, are regulated by σ54 (1, 18, 37). Regarding P. aeruginosa, although this bacterium is an opportunistic human pathogen, it has also been shown to be involved in plant pathogenesis. Interestingly, the HSI-1 cluster is regulated by the RetS/LadS sensor kinase pair and the GacS/GacA/Rsm pathway, a regulatory mechanism allowing the bacteria to switch from the acute phase of infection to the chronic phase (36). Furthermore, high-throughput screens have shown that the HSI-1 cluster, but not the HSI-2 and HSI-3 clusters, is required for lung infection in a rat model of respiratory infection, and antibodies against the HSI-1-linked Hcp protein are found in the sputum of cystic fibrosis patients infected with P. aeruginosa (36, 39). However, recent studies showed that the HSI-1 machinery translocates antibacterial effectors (21). These data suggest that the HSI-1 T6SS might serve as interbacterial competition in animals or humans, whereas our observation suggests that the HSI-2 and HSI-3 T6SS might have importance in the environment or for the development of plant diseases. Indeed, σ54 is required for full virulence toward plant models in P. syringae and P. aeruginosa (1, 19, 20, 37) and a redundant role of P. aeruginosa HSI-2 and HSI-3 T6SS in virulence toward the plant model Arabidopsis thaliana has been reported (26). The survey also shows that a putative σ54-dependent promoter is found upstream of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia pestis T6SS gene clusters. Here again, these animal and human pathogens have a infection cycle involving development in the flea, and one might suggest that these T6SS are likely involved in flea colonization rather than development of symptoms in humans. This prediction is strengthened by transcription profiling studies showing that the Y. pestis cluster is induced at low temperatures and repressed at 37°C, suggesting a role in the flea vector (35).

Most of the clusters studied in this work, such as V. cholerae, A. hydrophila, and Pectobacterium atrosepticum, but also Pseudomonas aeruginosa HSI-2 and HSI-3, have also been shown to be regulated by quorum-sensing or two-component systems (5, 22, 25, 26, 28). This raises the question of how these different regulatory mechanisms are coordinated. Zheng et al. recently suggested an elegant model to explain how the V. cholerae vas cluster is regulated, by coordinating the action of the quorum-sensing, histone-like TsrA, and σ54 pathways (67). Although we have demonstrated the existence of σ54 promoters, it remains possible that additional σ70 promoters might be responsive to other regulatory elements. One alternate hypothesis is that bEBP phosphorylation occurs through a quorum-sensing-dependent signaling pathway or is dependent upon a sensor kinase and a specific environmental signal which remain to be identified. Interestingly, the Pectobacterium atrosepticum T6SS gene cluster has been shown to be induced by cell extracts of potato tubers (31, 32), suggesting that the bacteria sense specific compounds and provide an output response leading to T6SS expression. In all these cases, defining the interplay or convergence of different regulatory pathways is essential to an understanding of the complete network of regulation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Andrew Johnston and Andrew Curson (University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom) for strain Marinomonas sp. MWYL-1, Béatrice Py (Institut de Microbiologie de la Méditerranée [IMM], Marseille, France) for strain Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. atrosepticum SCRI193, Guy Condemine (Institut Nationale des Sciences Appliquées [INSA], Lyon, France) for strain P. carotovorum ssp. atrosepticum SCRI1043, Peter S. Howard (University of Saskatchewan, Canada) for strain Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC7966, Anne Delcour (University of Houston, Houston, TX) for strain Vibrio cholerae O395, Mireille Ansaldi for plasmids, protocols, and discussions, Laurent Loiseau for plasmid pUIDC1 and protocols, Patrice Moreau for strains, and Emmanuelle Bouveret and members of the Lloubès, Bouveret, and Sturgis research groups for discussions, helpful comments, and encouragement. We thank the three anonymous reviewers for their interesting comments and suggestions. We thank Ginette O'yélaivécé for encouragement.

This work is supported by the Institut National des Sciences Biologiques of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique through a Projet Exploratoire—Premier Soutien (PEPS) grant (SDV.2009-1935) and an Agence National de la Recherche grant (ANR-10-JCJC-1303-03) to E.C. Y.R.B is supported by a graduate doctoral fellowship from the French Ministry of Research.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 4 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alarcón-Chaidez F. J., Keith L., Zhao Y., Bender C. L. 2003. RpoN (σ54) is required for plasmid-encoded coronatine biosynthesis in Pseudomonas syringae. Plasmid 49:106–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aschtgen M. S., Bernard C. S., de Bentzmann S., Lloubès R., Cascales E. 2008. SciN is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for type VI secretion in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:7523–7531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aschtgen M. S., Gavioli M., Dessen A., Lloubès R., Cascales E. 2010. The SciZ protein anchors the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli type VI secretion system to the cell wall. Mol. Microbiol. 75:886–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baba T., et al. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernard C. S., Brunet Y. R., Gueguen E., Cascales E. 2010. Nooks and crannies in type VI secretion regulation. J. Bacteriol. 192:3850–3860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bingle L. E., Bailey C. M., Pallen M. J. 2008. Type VI secretion: a beginner's guide. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bladergroen M. R., Badelt K., Spaink H. P. 2003. Infection-blocking genes of a symbiotic Rhizobium leguminosarum strain that are involved in temperature-dependent protein secretion. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16:53–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bordes P., et al. 2004. Communication between Esigma(54), promoter DNA and the conserved threonine residue in the GAFTGA motif of the PspF sigma-dependent activator during transcription activation. Mol. Microbiol. 54:489–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boyer F., Fichant G., Berthod J., Vandenbrouck Y., Attree I. 2009. Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: what can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? BMC Genomics 10:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buck M., Gallegos M. T., Studholme D. J., Guo Y., Gralla J. D. 2000. The bacterial enhancer-dependent σ54 (σN) transcription factor. J. Bacteriol. 182:4129–4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Casaz P., Gallegos M. T., Buck M. 1999. Systematic analysis of sigma54 N-terminal sequences identifies regions involved in positive and negative regulation of transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 292:229–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cascales E. 2008. The type VI secretion toolkit. EMBO Rep. 9:735–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen P., Reitzer L. J. 1995. Active contribution of two domains to cooperative DNA binding of the enhancer-binding protein nitrogen regulator I (NtrC) of Escherichia coli: stimulation by phosphorylation and the binding of ATP. J. Bacteriol. 177:2490–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dudley E. G., Thomson N. R., Parkhill J., Morin N. P., Nataro J. P. 2006. Proteomic and microarray characterization of the AggR regulon identifies a pheU pathogenicity island in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1267–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feng J., et al. 1992. Role of phosphorylated metabolic intermediates in the regulation of glutamine synthetase synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:6061–6070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Filloux A., Hachani A., Bleves S. 2008. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology 154:1570–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hendrickson E. L., Guevera P., Ausubel F. M. 2000. The alternative sigma factor RpoN is required for hrp activity in Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola and acts at the level of hrpL transcription. J. Bacteriol. 182:3508–3516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hendrickson E. L., et al. 2000. Virulence of the phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola is RpoN dependent. J. Bacteriol. 182:3498–3507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hendrickson E. L., Plotnikova J., Mahajan-Miklos S., Rahme L. G., Ausubel F. M. 2001. Differential roles of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 rpoN gene in pathogenicity in plants, nematodes, insects, and mice. J. Bacteriol. 183:7126–7134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hood R. D., et al. 2010. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 7:25–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishikawa T., Rompikuntal P. K., Lindmark B., Milton D. L., Wai S. N. 2009. Quorum sensing regulation of the two hcp alleles in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains. PLoS One 4:e6734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jefferson R. A., Burgess S. M., Hirsh D. 1986. β-Glucuronidase from Escherichia coli as a gene-fusion marker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:8447–8451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jyot J., Dasgupta N., Ramphal R. 2002. FleQ, the major flagellar gene regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, binds to enhancer sites located either upstream or atypically downstream of the RpoN binding site. J. Bacteriol. 184:5251–5260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khajanchi B. K., et al. 2009. N-Acylhomoserine lactones involved in quorum sensing control the type VI secretion system, biofilm formation, protease production, and in vivo virulence in a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microbiology 155:3518–3531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lesic B., Starkey M., He J., Hazan R., Rahme L. G. 2009. Quorum sensing differentially regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa type VI secretion locus I and homologous loci II and III, which are required for pathogenesis. Microbiology 155:2845–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leung K. Y., Siame B. A., Snowball H., Mok Y. K. 2011. Type VI secretion regulation: crosstalk and intracellular communication. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu H., et al. 2008. Quorum sensing coordinates brute force and stealth modes of infection in the plant pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lukat G. S., McCleary W. R., Stock A. M., Stock J. B. 1992. Phosphorylation of bacterial response regulator proteins by low molecular weight phospho-donors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:718–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MacIntyre D. L., Miyata S. T., Kitaoka M., Pukatzki S. 2010. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:19520–19524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mattinen L., Nissinen R., Riipi T., Kalkkinen N., Pirhonen M. 2007. Host-extract induced changes in the secretome of the plant pathogenic bacterium Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Proteomics 7:3527–3537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mattinen L., et al. 2008. Microarray profiling of host-extract-induced genes and characterization of the type VI secretion cluster in the potato pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Microbiology 154:2387–2396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCleary W. R., Stock J. B. 1994. Acetyl phosphate and the activation of two-component response regulators. J. Biol. Chem. 269:31567–31572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miyata S. T., et al. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system: evaluating its role in the human disease cholera. Front. Microbiol. 1:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Motin V. L., et al. 2004. Temporal global changes in gene expression during temperature transition in Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 186:6298–6305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mougous J. D., et al. 2006. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science 312:1526–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peñaloza-Vázquez A., Fakhr M. K., Bailey A. M., Bender C. L. 2004. AlgR functions in algC expression and virulence in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Microbiology 150:2727–2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Persson O. P., et al. 2009. High abundance of virulence gene homologues in marine bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1348–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Potvin E., et al. 2003. In vivo functional genomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for high-throughput screening of new virulence factors and antibacterial targets. Environ. Microbiol. 5:1294–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pukatzki S., et al. 2006. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1528–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pukatzki S., McAuley S. B., Miyata S. T. 2009. The type VI secretion system: translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rao P. S., Yamada Y., Tan Y. P., Leung K. Y. 2004. Use of proteomics to identify novel virulence determinants that are required for Edwardsiella tarda pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 53:573–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rappas M., Bose D., Zhang X. 2007. Bacterial enhancer-binding proteins: unlocking sigma54-dependent gene transcription. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17:110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reitzer L., Schneider B. L. 2001. Metabolic context and possible physiological themes of sigma(54)-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:422–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schell M. A., et al. 2007. Type VI secretion is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia mallei. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1466–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schwarz S., Hood R. D., Mougous J. D. 2010. What is type VI secretion doing in all those bugs? Trends Microbiol. 18:531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schwarz S., et al. 2010. Burkholderia type VI secretion systems have distinct roles in eukaryotic and bacterial cell interactions. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shalom G., Shaw J. G., Thomas M. S. 2007. In vivo expression technology identifies a type VI secretion system locus in Burkholderia pseudomallei that is induced upon invasion of macrophages. Microbiology 153:2689–2699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Studholme D. J., Dixon R. 2003. Domain architectures of sigma54-dependent transcriptional activators. J. Bacteriol. 185:1757–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Studholme D. J., Wigneshwereraraj S. R., Gallegos M. T., Buck M. 2000. Functionality of purified σN (σ54) and a NifA-like protein from the hyperthermophile Aquifex aeolicus. J. Bacteriol. 182:1616–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Suarez G., et al. 2008. Molecular characterization of a functional type VI secretion system from a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb. Pathog. 44:344–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suarez G., Sierra J. C., Kirtley M. L., Chopra A. K. 2010. Role of a type 6 secretion system effector Hcp of Aeromonas hydrophila in modulating activation of host immune cells. Microbiology 156:3678–3688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Syed K. A., et al. 2009. The Vibrio cholerae flagellar regulatory hierarchy controls expression of virulence factors. J. Bacteriol. 191:6555–6570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tabor S., Richardson C. C. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:1074–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tardat B., Touati D. 1993. Iron and oxygen regulation of Escherichia coli MnSOD expression: competition between the global regulators Fur and ArcA for binding to DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 9:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tintut Y., Wong C., Jiang Y., Hsieh M., Gralla J. D. 1994. RNA polymerase binding using a strongly acidic hydrophobic-repeat region of sigma 54. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:2120–2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tropel D., van der Meer J. R. 2002. Identification and physical characterization of the HbpR binding sites of the hbpC and hbpD promoters. J. Bacteriol. 184:2914–2924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van den Ent F., Löwe J. 2006. RF cloning: a restriction-free method for inserting target genes into plasmids. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 67:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vieira J., Messing J. 1991. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene 100:189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weber B., Hasic M., Chen C., Wai S. N., Milton D. L. 2009. Type VI secretion modulates quorum sensing and stress response in Vibrio anguillarum. Environ. Microbiol. 11:3018–3028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Weiss V., Magasanik B. 1988. Phosphorylation of nitrogen regulator I (NRI) of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:8919–8923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wigneshweraraj S. R., et al. 2008. Modus operandi of the bacterial RNA polymerase containing the sigma54 promoter-specificity factor. Mol. Microbiol. 68:538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wigneshweraraj S. R., Casaz P., Buck M. 2002. Correlating protein footprinting with mutational analysis in the bacterial transcription factor sigma54 (sigmaN). Nucleic Acids Res. 30:1016–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang X., et al. 2002. Mechanochemical ATPases and transcriptional activation. Mol. Microbiol. 45:895–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang N., et al. 2009. The role of the conserved phenylalanine in the sigma54-interacting GAFTGA motif of bacterial enhancer binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:5981–5992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zheng J., Leung K. Y. 2007. Dissection of a type VI secretion system in Edwardsiella tarda. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1192–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zheng J., Shin O. S., Cameron D. E., Mekalanos J. J. 2010. Quorum sensing and a global regulator TsrA control expression of type VI secretion and virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:21128–21133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.