Abstract

The afsS gene of several Streptomyces species encodes a small sigma factor-like protein that acts as an activator of several pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., actII-ORF4 and redD in Streptomyces coelicolor). The two pleiotropic regulators AfsR and PhoP bind to overlapping sequences in the −35 region of the afsS promoter and control its expression. Using mutated afsS promoters containing specific point mutations in the AfsR and PhoP binding sequences, we proved that the overlapping recognition sequences for AfsR and PhoP are displaced by 1 nucleotide. Different nucleotide positions are important for binding of AfsR or PhoP, as shown by electrophoretic mobility shift assays and by reporter studies using the luxAB gene coupled to the different promoters. Mutant promoter M5 (with a nucleotide change at position 5 of the consensus box) binds AfsR but not PhoP with high affinity (named “superAfsR”). Expression of the afsS gene from this promoter led to overproduction of actinorhodin. Mutant promoter M16 binds PhoP with extremely high affinity (“superPhoP”). Studies with ΔafsR and ΔphoP mutants (lacking AfsR and PhoP, respectively) showed that both global regulators are competitive transcriptional activators of afsS. AfsR has greater influence on expression of afsS than PhoP, as shown by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) and promoter reporter (luciferase) studies. These two high-level regulators appear to integrate different nutritional signals (particularly phosphate limitation sensed by PhoR), S-adenosylmethionine, and other still unknown environmental signals (leading to AfsR phosphorylation) for the AfsS-mediated control of biosynthesis of secondary metabolites.

INTRODUCTION

Most of the genes which code for the synthesis of secondary metabolites are arranged in clusters which contain pathway-specific regulators (2, 21). These regulators are frequently controlled by other proteins with global regulatory functions. Examples of these regulators are AfsK, AfsR, and AfsS. These proteins have been shown to influence secondary metabolism and morphogenesis in several species of Streptomyces (8, 17, 29, 30, 40, 42).

The complete AfsK/AfsR/AfsS system was first described in Streptomyces coelicolor (reviewed in reference 10). AfsK is a loosely attached membrane kinase that autophosphorylates in serine and threonine residues under certain stimuli (e.g., S-adenosylmethionine) to enhance its kinase activity (16, 42). The activated AfsK phosphorylates the serine and threonine residues of the AfsR protein (24). Another protein, KbpA, inhibits the autophosphorylation of AfsK (41). Two other serine/threonine kinases, AfsL and PkaG, were also found to phosphorylate AfsR (35), suggesting that AfsR integrates multiple inputs. Phosphorylated AfsR binds the −35 region of the afsS promoter and activates its transcription (15, 39). AfsS then stimulates the expression of genes encoding the pathway-specific transcriptional regulators ActII-ORF4 and RedD, which in turn activate the transcription of the actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin genes (6, 10). Disruption of afsK, afsR, and afsS genes decreases antibiotic production in S. coelicolor, indicating that these gene products act as positive regulators of secondary metabolism in this bacterium (6, 15, 17, 24).

The positive effect which these proteins exert on secondary metabolism has also been observed in other Streptomyces species. For example, complementation of a Streptomyces avermitilis afsK disrupted mutant with a copy of a plasmid containing the afsK gene restored avermectin production (29). Overexpression of the afsR gene was shown to increase secondary metabolite production, not only in S. coelicolor but also in S. lividans, S. clavuligerus, S. griseus, S. peucetius, and S. venezuelae (6, 9, 19, 26). A similar effect was produced by the overexpression of the afsS gene in S. coelicolor, S. lividans, S. avermitilis, and S. albus (6, 14, 20, 25, 43). Therefore, these proteins are described as positive regulators of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces.

When the environmental phosphate concentration is low, many bacteria respond through changes in gene expression mediated by a conserved two-component system, named phoR-phoP in Streptomyces. The response regulator PhoP controls the transcription of pho regulon genes in S. coelicolor by binding to specific sequences called PHO boxes (37). Interestingly, PhoP binds and regulates the afsS gene in competition with AfsR (34). Both AfsR and PhoP regulators recognize overlapping sequences in the promoter region of afsS. The role of PhoP in the expression of afsS was initially thought to be negative because of its competition with the AfsR activator protein and the higher afsS promoter activity obtained in a ΔphoP mutant than in the wild-type strain. In this study, we prove that both proteins behave as competitive activators of afsS, with each being able to activate the transcription of this gene when acting separately. We have identified the nucleotides which are important for the recognition of each protein. Different operators that are able to bind only one, both, or neither of the two proteins have been obtained. The use of one of these mutated operators in the afsS gene resulted in an antibiotic-overproducing strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. The Streptomyces coelicolor strains used were the parental M145 strain and several mutants derived from it. The ΔafsR ΔphoP double mutant (INB513) was obtained from the ΔafsR mutant strain M513 (6) by replacement of the phoP gene with an apramycin resistance cassette as described previously (31). The ΔafsS mutant M952 was provided by Mervyn Bibb. All of the Streptomyces strains were manipulated according to standard procedures (12).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain/plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | ||

| M145 | Wild type | 12 |

| INB201 | ΔphoP Amr | 34 |

| M513 | ΔafsR | 6 |

| INB513 | ΔafsR ΔphoP Amr | This work |

| M952 | ΔafsS Amr | Mervyn Bibb |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | F′ φ80dlacZΔM15 | 7 |

| ET12567(pUZ8002) | dam dcm mutant, Neor Cmr | 18 |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3)/pLysS (Camr) | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFS-afsS | PCR product carrying afsS promoter cloned into pBSIISK+a, Ampr | 34 |

| pFS-afsS-M1 | PCR product carrying afsS-Mu-0 promoter cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pFS-afsS-M2 | PCR product carrying afsS-Mu-1 promoter cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pFS-afsS-M3 | PCR product carrying afsS-Mu-2 promoter cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pFS-afsS-M5 | PCR product carrying afsS-Mu-4 promoter cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pFS-afsS-M14 | PCR product carrying afsS-Mu-13 promoter cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pFS-afsS-M16 | PCR product carrying afsS-Mu-15 promoter cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pLUXAR-neo | Integrative promoter-probe vector, luxAB genes, Amr Neor | 34 |

| pLUX-afsS | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | 34 |

| pLUX-afsS-M1 | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS-M1 fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | This work |

| pLUX-afsS-M2 | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS-M2 fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | This work |

| pLUX-afsS-M3 | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS-M3 fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | This work |

| pLUX-afsS-M5 | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS-M5 fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | This work |

| pLUX-afsS-M14 | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS-M14 fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | This work |

| pLUX-afsS-M16 | BamHI-NdeI pFS-afsS-M16 fragment cloned into pLUXAR-neo, Amr Neor | This work |

| pBluescriptIISK+ | Cloning vector, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pAR-afsS | PCR product carrying complete wild-type afsS gene cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pAR-afsS-M5 | PCR product carrying complete M5 afsS gene cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pAR-afsS-M16 | PCR product carrying complete M16 afsS gene cloned into pBSIISK+, Ampr | This work |

| pRA | Conjugative, integrative vector derived from pSET152 | 28 |

| pARint-afsS | Integrative vector with complete wild-type afsS gene | This work |

| pARint-afsS-M5 | Integrative vector with complete M5 afsS gene | This work |

| pARint-afsS-M16 | Integrative vector with complete M16 afsS gene | This work |

| pET16-afsRΔTPR | Cloning vector carrying His-tagged truncated AfsR (Met1 to Glu618), Ampr | 39 |

| pGEX-DBD | S. coelicolor phoP DBD gene cloned into pGEX-2T | 37 |

pBSIISK+, pBluescriptIISK+.

Primers CAR91 (TGAGGAATTCGGAGCCGGTCTCCTGAAC, introduced EcoRI site underlined) and CAR21 (ATGCGGATCCTCAGCCTCTACGAGCAGC, BamHI site underlined) were used to amplify the complete afsS gene. After EcoRI-BamHI digestion, the product (578 bp) was cloned into pBluescriptIISK+ to obtain pAR-afsS. The insert was sequenced to confirm the absence of mutations. The EcoRV-BamHI fragment was ligated into pRA-neo vector, a derivative of the conjugative, integrative plasmid pRA (28) containing the kanamycin resistance gene neo, to obtain pARint-afsS.

All of the S. coelicolor cultures were grown in defined MG medium (5) containing 3.2 mM potassium phosphate (MG-3.2 [33]) for phosphate-limited studies.

For luciferase studies, samples were taken at 45 and 50 h of culture, and for antibiotic production assays, samples were collected at 47, 50, 54, 57, 70, and 80 h.

Production and purification of H-AfsRΔTPR and GST-PhoPDBD proteins.

The H-AfsRΔTPR protein (68 kDa; His-tagged protein containing the N-terminal and central regions of AfsR, but with the C-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat [TPR] deleted) (39) was purified from the soluble fraction of Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS harboring the plasmid pET16-afsRΔTPR, as described by Lee et al. (15). The purified samples were dialyzed overnight against a 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7)—10% glycerol solution.

The GST-PhoPDBD protein (39 kDa; consisting of glutathione S-transferase [GST] fused to the DNA-binding domain [DBD] of PhoP) (37) was purified from the soluble fraction of E. coli DH5α harboring the plasmid pGEX-DBD, as described by Sola-Landa et al. (37). Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad).

Luciferase assay, growth, and antibiotic production.

luxAB expression was determined in a Luminoskan luminometer (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) as follows. Culture samples were immediately ice cooled; 50 μl of 1% n-decanal was added to 100 μl of sample, and the light emission was read after 10 s of integration time. For each culture sample, triplicate measurements were averaged. For dry weight determination, cells were harvested from 2 ml of culture, washed twice with MilliQ water, and dried at 80°C.

Antibiotic production assays were performed as described by Kieser et al. (12).

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR).

RNAs from S. coelicolor strains M145, INB201, M513, and INB513 (parental strain and ΔphoP, ΔafsR, and ΔafsR ΔphoP mutants, respectively) were isolated from 44-h cultures. Commercial kits were used for RNA stabilization in the culture samples (RNA Protect bacterial reagent [Qiagen]), purification (RNeasy minispin columns [Qiagen]), and DNA removal (both an RNase-free DNase set [Qiagen] and a DNA-free kit [Ambion]). RNA concentration and quality were checked using a NanoDrop ND-1000 instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent).

Transcriptional analysis of afsS was performed using SuperScript one-step RT-PCR with a Platinum Taq kit (Invitrogen) and primers afsS-Dir-RT (CGACAAGATGAAGGACGCG) and afsS-Rev-RT (TACTTGCCGTCGCCGTCC), which amplified 186 bp of the afsS coding region. The primers hrdB-Dir-RT (ACGCCCCGGCCCAGCAGGTC) and hrdB-Rev-RT (CAGGTGGCGTACGTGGAGAACTTGT) were used in the control reactions to amplify the hrdB transcript (400 bp).

RT-PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for 60 min and 94°C for 2 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 70°C for 30 s, with a decrease of 1°C per cycle, followed by 72°C for 50 s; 30 to 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s; and, finally, 72°C for 10 min. The optimized reaction mixes contained 200 ng of total RNA, 1.45 mM MgSO4, and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Platinum Taq was used in control reactions to ensure the lack of DNA contamination.

Directed mutagenesis.

Point mutations of the afsS promoter were generated with the site-directed ligase independent mutagenesis (SLIM) procedure described by Chiu et al. (4) using the primers detailed in Table 2 and the plasmids pFS-afsS (34) and pAR-afsS (this work) as templates.

Table 2.

Primers used in the SLIM procedure to introduce point mutations in the AfsR and PhoP binding sequences of the afsS promoter

| Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Stranda | Targetb |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP01 | TATCTCCCCCTGGCACTG | Dir | DRu-1 |

| AP02 | CGGCTACCGCCGGTCGAC | Rev | DRu-1 |

| AP03 | GAGTGTTCAGCGTTCGTTTATCTCCCCCTGGCACTG | Dir | M1 |

| AP04 | AACGAACGCTGAACACTCCGGCTACCGCCGGTCGAC | Rev | M1 |

| AP05 | GAGCTTTCAGCGTTCGTTTATCTCCCCCTGGCACTG | Dir | M2 |

| AP06 | AACGAACGCTGAAAGCTCCGGCTACCGCCGGTCGAC | Rev | M2 |

| AP07 | GAGCGATCAGCGTTCGTTTATCTCCCCCTGGCACTG | Dir | M3 |

| AP08 | AACGAACGCTGATCGCTCCGGCTACCGCCGGTCGAC | Rev | M3 |

| AP09 | GAGCGTTTAGCGTTCGTTTATCTCCCCCTGGCACTG | Dir | M5 |

| AP10 | AACGAACGCTAAACGCTCCGGCTACCGCCGGTCGAC | Rev | M5 |

| AP11 | CCTGGCACTGTCATCTCC | Dir | DRu-2 |

| AP12 | GAACGCTCCGGCTACCGC | Rev | DRu-2 |

| AP13 | AGCGTTCGATTATCTCCCCCTGGCACTGTCATCTCC | Dir | M14 |

| AP14 | GGGAGATAATCGAACGCTGAACGCTCCGGCTACCGC | Rev | M14 |

| AP15 | AGCGTTCGTTCATCTCCCCCTGGCACTGTCATCTCC | Dir | M16 |

| AP16 | GGGAGATGAACGAACGCTGAACGCTCCGGCTACCGC | Rev | M16 |

Dir, forward; Rev, reverse.

DRu-1, direct repeat unit 1; DRu-2, direct repeat unit 2.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

The conditions for the DNA–GST-PhoPDBD and DNA–H-AfsRΔTPR binding reactions were those described by Sola-Landa et al. (37) and Tanaka et al. (39), respectively. Labeling of the DNA fragments was done as described previously (34). A constant DNA concentration was maintained in all reactions. Electrophoresis was carried out in 5% acrylamide gels with 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer for 2 h at 80 V, using a mini-Protean III instrument (Bio-Rad).

Bioinformatic analysis.

The sequences downstream of afsR in the different species of Streptomyces were obtained from StrepDB (http://strepdb.streptomyces.org.uk) (S. coelicolor, S. avermitilis, S. griseus, and S. scabiei) and from GenBank (S. noursei). All others were from the Broad Institute database. The sequence corresponding to S. tsukubaensis was obtained from the genome sequencing project data at INBIOTEC (unpublished).

The WebLogo page (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi) was used to create the sequence logo of the afsS direct repeats.

The scanning of the S. coelicolor genome for sequences was done using the RSAT web page (http://rsat.ulb.ac.be/rsat/). To calculate the individual information content (Ri) of each 11-nucleotide (nt) sequence, the weight matrix of model 1 of PhoP operators was used (38).

RESULTS

Analysis of the PhoP and AfsR binding sequences in the S. coelicolor afsS promoter.

Previously, we reported that the PhoP binding site in the afsS promoter overlaps with the AfsR binding site in S. coelicolor (34). The overlapped sequence encompasses two 11-nucleotide direct repeats. These direct repeats are located 163 nt upstream of the afsS start codon and 30 nt downstream of the afsR end triplet. Tanaka and coworkers (39) proved the importance of the localization of these repeats with respect to the −10 element and the relevance of both repeat units for the transcription of the afsS gene. However, these authors did not determine which nucleotides are necessary for AfsR binding and activation of afsS gene transcription.

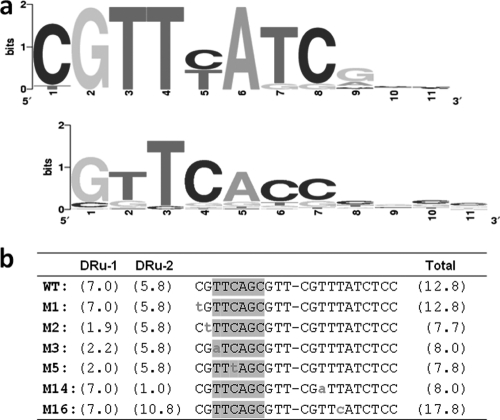

In order to test the conservation of the AfsR-binding direct repeats among organisms in the Streptomyces genus, the afsS sequences of 20 different species were analyzed. The alignment of the 40 repeat units showed high conservation in the first 8 nucleotides. This is depicted in the sequence logo shown in Fig. 1a. Nucleotides at positions 2 (G), 3 (T), 4 (T), and 6 (A) are fully conserved in all species analyzed. Positions 1, 7, and 8 are highly conserved (at least 90% of the repeat units share the same nucleotide). Position 5 shows either a C or a T. Interestingly, when the direct repeat units of one promoter are analyzed, each unit has a C or a T, but in no case is the same nucleotide (i.e., C/C or T/T) present at the fifth positions of both repeat units. In summary, the first 8 nucleotides in both repeat units are almost the same among the Streptomyces species, and the fifth position shows a fixed pattern of variation that involves both repeats of the binding site. This consensus AfsR-binding sequence is somewhat different from the consensus PhoP binding sequence (Fig. 1a, bottom logo). We decided to analyze by mutagenesis the role of these nucleotides in the regulation of afsS.

Fig. 1.

(a) (Top) Sequence logo corresponding to the alignment of the 11-nt sequences that form the direct repeat unit of the AfsR and PhoP overlapping operators in the afsS gene of the following species of Streptomyces: S. coelicolor, S. avermitilis, S. lividans, S. noursei, S. griseus, S. scabiei, S. tsukubaensis, S. clavuligerus, S. pristinaespiralis, S. roseosporus, S. hygroscopicus, S. albus, S. sviceus, S. viridochromogenes, S. ghanaensis, S. griseoflavus, Streptomyces sp. strain E14, Streptomyces sp. strain C, Streptomyces sp. strain Mg1, and Streptomyces sp. strain SPB74. (Bottom) For comparison, the logo of the PhoP binding sites is shown (33). (b) Point mutations made in the AfsR and PhoP binding sequences of the S. coelicolor afsS promoter by SLIM. Lowercase letters indicate the changed nucleotides. The −35 element described by Lee et al. (15) is indicated with shaded boxes, and the conservation value (Ri) of each PhoP direct repeat according to model I (38) is shown for each mutant. Note that the PhoP operator starts in the second nucleotide. WT, wild type; DRu-1 and DRu-2, direct repeat units 1 and 2, respectively.

Directed modifications of the AfsR and PhoP operators in the afsS promoter.

Previously, we described that the binding of PhoP to the afsS promoter caused a negative effect on the expression of afsS by hampering the binding of the AfsR protein (the main afsS activator) (34). The binding site of PhoP in the afsS promoter overlaps the −35 region, and this situation is also found in other genes for which PhoP functions as an activator (22). We introduced point mutations on the afsS promoter in order to test whether PhoP is able to activate the expression of afsS when AfsR is not present and to elucidate which nucleotides are important for the specific binding of each protein.

To decide which mutations might be more informative, the model of PhoP operators (38) was taken into account. The PhoP binding sites are composed of direct repeat units of 11 nt. The five more frequent nucleotides of the PhoP sequence (GTTCA, positions 1 to 5) match the nucleotides that appear in positions 2 to 6 of the AfsR logo shown in Fig. 1a, with the exception of the T at position 5. By means of an information-based score matrix (model 1 [38]), we were able to predict the effect of mutations on PhoP binding. For each 11-nt repeat, an information content value (Ri) was obtained from the matrix.

Using the SLIM procedure (4), we generated 6 point mutations (Fig. 1b). The rationale for these mutations was to discriminate which nucleotides were important for binding of each regulatory protein. In the M1 sequence, the first nucleotide was mutated because it is conserved in the direct repeat of afsS but it is not conserved in the PhoP operators (so the Ri value of the PhoP operator did not change) (Fig. 1a and b). For the mutation of the second position (M2), the guanine, although it is always present in the afsS repeats, it is conserved in the PhoP operator. As shown in Fig. 1b, the M2 mutation decreases the Ri value of the mutant operator.

Similarly, with M3, we tested the effect of changing an invariable nucleotide included in the −35 element. In order to determine whether the effect of the mutation was due to the modification of the −35 element, the same mutation was made in the second repeat (M14). In both cases, the Ri value of the whole PhoP operator decreased to 8.0.

In M5 and M16, artificial CGTTTA and CGTTCA direct repeat units, respectively, were created. As for the other mutants, the PhoP Ri value of M5 decreased with respect to the wild-type value. On the contrary, the Ri value of M16 increased five units. The direct repeat generated in the M5 mutation does not appear in any promoter of the S. coelicolor genome. On the other hand, the direct repeat generated in M16 appears in the promoters of SCO1394, SCO6372, and SCO7453. Of these three genes, the first two have been described as members of the pho regulon in S. coelicolor (38). Therefore, it is expected that the site created in M16 binds PhoP with higher affinity than the sites in other mutants.

In vitro analysis of the binding of AfsR and PhoP to the mutant afsS promoters.

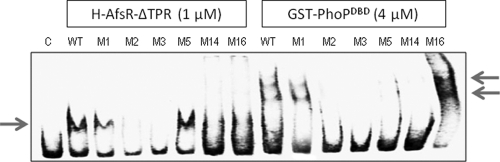

We previously described that an H-AfsRΔTPR protein concentration of 0.5 μM was enough to produce a shift in the phoRP and pstS promoters (34). In addition, we showed that a GST-PhoPDBD concentration of 2 μM was enough to produce a shift in the afsS promoter.

In this work, to test the abilities of these proteins to bind the different afsS mutated promoters, EMSAs were performed. In all cases, the same amounts of DNA (1 ng) and protein (1 μM for H-AfsRΔTPR and 4 μM for GST-PhoPDBD) were used to avoid differences in the DNA/protein ratios.

Figure 2 shows that all of the mutations that decreased the Ri value of the PhoP operator (M2, M3, M5, and M14 mutations) prevented the binding of PhoP. In contrast, the M16 sequence, with an increased Ri value, yielded a much higher percentage of probe retardation (i.e., increased binding) than the wild-type or M1 fragment. In the M1 fragment, the mutation did not affect the PhoP binding site core. In summary, it can be concluded that, as expected, there was a good correlation between the calculated Ri variation for each mutant sequence and the loss or gain of PhoP affinity. Due to the increased PhoP binding to the M16 sequence, we named M16 the “superPhoP” operator.

Fig. 2.

EMSAs of the wild-type and mutated afsS promoters, using the proteins H-AfsRΔTPR and GST-PhoPDBD. In lane C (control, using the wild-type promoter), no proteins were added. Note the increase of the PhoP binding activity in the M16 mutant. Note also the cooperative binding of PhoP that results in the formation of several DNA/protein complexes.

On the other hand, all of the mutations that change the invariable nucleotides of the repeat (M2, M3, and M14 mutations) prevented the binding of AfsR. This result proved the importance of the 2nd (G) and 3rd (T) positions for the binding of AfsR. The involvement of the less conserved cytosine at position 1 was also reflected in the binding assays (Fig. 2). The most favorable nucleotide at position 5 for AfsR binding was a thymine (the M5 sequence is recognized with at least the same affinity as the wild-type sequence), as opposed to a cytosine (M16), which impaired the AfsR protein binding (Fig. 2).

These results (lack of binding of PhoP to M5 and of AfsR to M16) may explain why, in order to bind both proteins, the homologous afsS operators always conserve a C in one repeat and a T in the other.

Moreover, the inability of both PhoP and AfsR to bind M3 and M14, with the equivalent positions changed, indicates the need of the two direct repeat units for the binding of both proteins, in concordance with the observations published by Sola-Landa et al. (38) for PhoP and by Tanaka et al. (39) for AfsR.

Analysis of afsS expression in the ΔphoP, ΔafsR, and ΔafsR ΔphoP strains.

As described above, the afsS promoter region has the ability to be bound at least by the AfsR and PhoP proteins. So far, AfsR is the only known activator of the afsS gene; however, significant afsS promoter activity was detected in a ΔafsR strain (34). It has not been determined which regulator activates the afsS promoter in the ΔafsR background or whether PhoP might be this second activator.

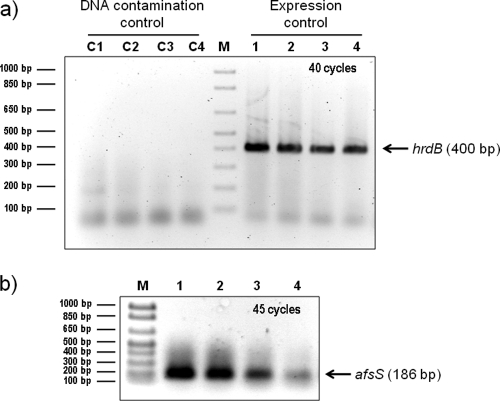

To study the effect of the lack of both the AfsR and the PhoP protein on afsS expression, an ΔafsR ΔphoP double mutant (strain INB513) was constructed as indicated in Materials and Methods. The afsS transcription in the wild-type, ΔphoP, ΔafsR, and ΔafsR ΔphoP backgrounds was studied by RT-PCR. Samples for RNA were taken from 44-h MG-3.2 cultures. This medium is limited in phosphate, and the expression of pho genes, as well as growth, antibiotic production, and phosphate consumption, has been determined before (32, 33, 34). The pho regulon in S. coelicolor is induced when the phosphate in the medium reaches a concentration lower than 0.1 mM. In MG-3.2, this occurs after 44 h of culture (33).

Amplification of the control hrdB transcript was clearly observed in all of the RNA samples after 40 cycles. No amplification was detected when the retrotranscriptase was omitted, which indicates a lack of DNA contamination (Fig. 3a). The amplification of the afsS transcript obtained after 40 cycles was poor (data not shown). When the number of cycles was increased to 45, good amplification was obtained; the highest intensity of afsS transcript corresponded to the wild-type and the ΔphoP strains, in which the AfsR activator is functional (Fig. 3b). The low but significant afsS transcript obtained in the ΔafsR mutant was in agreement with our previous promoter-probe assays (34). On the other hand, the lack of afsS transcript in the double mutant points to an activator role of PhoP (in addition to that of AfsR) in afsS transcription.

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR amplification of the hrdB (a) and afsS (b) transcripts using the RNA of S. coelicolor M145 (parental strain, lane 1), INB201 (ΔphoP mutant, lane 2), M513 (ΔafsR mutant, lane 3), and INB513 (ΔafsR ΔphoP mutant, lane 4) strains. Cultures were grown in MG-3.2 medium, and samples for RNA were taken at 44 h. The hrdB transcript is used as an expression control. For the DNA control reactions (represented by C1 to C4), Platinum Taq was added instead of retrotranscriptase. Lane M, molecular size marker.

In vivo analysis of the effect of the point mutations on afsS promoter activity.

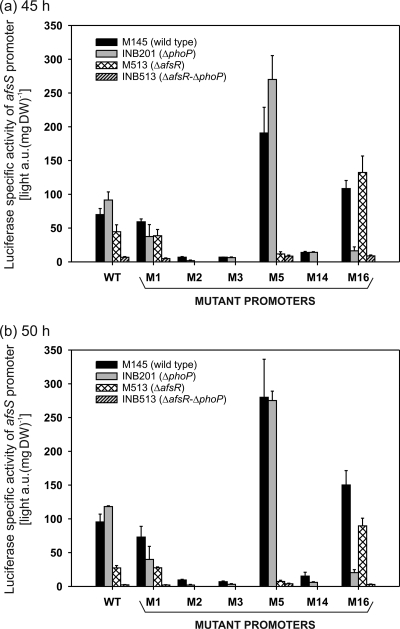

In order to determine the effect of the point mutations on promoter activity of afsS, the wild-type and mutant promoters were cloned into the promoter-probe vector pLUXAR-neo for comparative studies. The respective plasmids were then introduced into the M145 (wild-type), INB201 (ΔphoP mutant), M513 (ΔafsR mutant), and INB513 (ΔafsR ΔphoP mutant) strains.

Liquid MG-3.2 defined medium was used to grow the different strains. The maximum promoter activity of afsS in this medium is reached after 50 h of growth (34).

The specific luciferase activities of the wild-type afsS promoter were lower in the M513 strain (ΔafsR mutant) and higher in the INB201 strain (ΔphoP mutant) than in the parental M145 strain at 45 and 50 h (Fig. 4). The almost null promoter activity in the ΔafsR ΔphoP background coincided with the results of the RT-PCR experiment.

Fig. 4.

Promoter activity of afsS determined using the luxAB reporter of S. coelicolor M145 (wild-type), INB201 (ΔphoP mutant), M513 (ΔafsR mutant), and INB513 (ΔafsR ΔphoP mutant) strains. Each of these strains contained an integrated single copy of pLUX-afsS, pLUX-afsS-M1, pLUX-afsS-M2, pLUX-afsS-M3, pLUX-afsS-M5, pLUX-afsS-M14, and pLUX-afsS-M16. The plasmids pLUX-afsS-M2, pLUX-afsS-M3, and pLUX-afsS-M14 were not introduced into strains M513 and INB513, because the low activities obtained with those plasmids in strains M145 (wild type) and INB201 (ΔphoP mutant) suggested that no activity would be obtained in strains M513 (ΔafsR mutant) and INB513 (double deletion mutant). The cultures were grown in 100 ml of MG-3.2 medium at 30°C and 300 rpm. Samples for dry weight (DW) and luciferase determination were taken at 45 and 50 h of growth (time of maximal expression). Error bars correspond to the standard errors of the means from three biological replicates. a.u., arbitrary units.

The specific luciferase activities of all mutant afsS promoters which bind neither AfsR nor PhoP (M2, M3, and M14) were significantly reduced compared to that of the wild-type promoter. At the time of maximum afsS luciferase activity (50 h), the M2, M3, and M14 values were, respectively, 10%, 7%, and 16% that of the wild-type promoter in the M145 strain and 2%, 3%, and 5% that of the wild-type promoter in the INB201 strain. These results indicate that in M2, M3, and M14 these nucleotide modifications almost abolish the promoter activity of afsS, especially in the ΔphoP mutant strain, confirming that the wild-type nucleotides are important for the AfsR interaction with the promoter. The reduction of afsS promoter activity in the promoters that do not bind PhoP and AfsR reveals again a positive role in afsS expression not only for AfsR, but also for PhoP.

The specific luciferase activities of the M1 promoter in the M145 strain, which binds both proteins, were similar to those of the parental M145 promoter (85% at 45 h and 77% at 50 h). However, the values in the ΔphoP (INB201) background were less than half of the wild-type promoter activities (41% at 45 h and 34% at 50 h).

On the other hand, in the ΔafsR (M513) background, the luciferase values of the M1 promoter were almost equal to those of the wild-type promoter (87% at 45 h and 100% at 50 h). These results indicate that in the M1 promoter the activation due to AfsR, but not the activation due to PhoP, is impaired. This makes sense since the nucleotide C is much more conserved than the nucleotide T in the first position of the direct repeat (Fig. 1a). Moreover, this position is not included in the PhoP core operator (28), so it should not be involved in PhoP binding. Our results with the M1 mutant confirmed that the AfsR and PhoP binding sequences start at positions displaced in 1 nucleotide.

With promoters M5 and M16, which bind only one of the two proteins, the luciferase activities are in concordance with the EMSA results. The M5 specific activity values were reduced in the ΔafsR strain background (to 26% at 45 h and 27% at 50 h), since it lacks activation by AfsR, but increased in the parental M145 strain (272% and 293% at 45 and 50 h, respectively) and the ΔphoP strain (295% and 233% at 45 and 50 h, respectively), where AfsR is functional. This means that the nucleotide T in the fifth position of the direct repeat is required for the activation properties of AfsR and that, as expected, this nucleotide hampers the binding of PhoP (the PhoP operator Ri value is decreased in M5). Similarly to the M16 sequence (see above), we named the M5 operator “superAfsR.”

On the contrary, the M16 promoter increased the activation properties of PhoP and decreased those of AfsR. Thus, the luciferase values of M16, with respect to those of the wild-type promoter, were 297% at 45 h and 327% at 50 h in the ΔafsR strain (where PhoP is the remaining activator) and 18% at 45 h and 17% at 50 h in the ΔphoP strain. This result is in agreement with the higher Ri value of M16 and confirms the “superPhoP” character of this mutant promoter.

For M5 and M16, as for the wild-type and M1 promoters, less than 10% reporter activity values were detected in the ΔafsR ΔphoP double mutant strain with regard to the values for the parental M145 strain. This means that the activation of the afsS gene can be exerted by both AfsR and PhoP, with the activation activity of AfsR being higher than that of PhoP. Thus, in the wild-type promoter, when AfsR acts alone (in the ΔphoP strain), it generates a higher promoter activity than when both proteins act together (parental M145 strain). Therefore, these proteins may be described as competitive activators (3, 27).

In vivo analysis of the effect of “superPhoP” and “superAfsR” promoters on antibiotic production.

In order to test whether the high promoter activities obtained with the M5 and M16 promoters in the presence and absence of afsR, respectively, affect antibiotic production, the strains M952 (ΔafsS mutant) and M513 (ΔafsR mutant) were complemented with the pARint-afsS, pARint-afsS-M5, or pARint-afsS-M16 integrative plasmid. The resulting complemented strains, together with the M952 (ΔafsS mutant), M513 (ΔafsR mutant), and M145 (parental) strains, were grown in MG-3.2 medium and tested for growth and antibiotic production at 47, 50, 54, 57, 70, and 80 h. The introduction into the ΔafsR strain of one extra copy of afsS with either its own promoter or the “superAfsR” (M5) or “superPhoP” (M16) promoter did not produce a significant effect on the undecylprodigiosin production with respect to that for the ΔafsR strain (Fig. 5c). In contrast, the production of actinorhodin was significantly increased in the ΔafsR strain with the introduction of the afsS gene under the control of the “superPhoP” promoter (Fig. 5b), which is in agreement with its higher promoter activity in this background (Fig. 4). However, the actinorhodin production of this strain (M513/pARint-afsS-M16) was still about four times lower than that of the parental strain M145 (Fig. 5b and 6b). Thus, afsS appears to depend on AfsR for its stimulatory properties, as previously stated by other authors (6). On the other hand, the complementation of the ΔafsS strain with the afsS gene under the control of the wild-type, the “superAfsR” (M5), or the “superPhoP” (M16) promoter restored the wild-type levels of actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin production (Fig. 6b and c). As shown in Fig. 6b, the actinorhodin values of the ΔafsS strain M952 at the times when production rates were highest (at 57, 70, and 80 h) were reduced to 30, 32, and 34%, respectively, of the level of the parental M145 strain. The undecylprodigiosin values were also lower in the ΔafsS strain (43, 45, and 49% that of the parental strain at 57, 70, and 80 h, respectively [Fig. 6c]). This reduction of antibiotic production in the ΔafsS strain is in agreement with data published by Lee et al. (15) and Lian et al. (17), although in the latter study, in R5 cultures no actinorhodin production at all was obtained in the afsS disruption mutant. The results of our work with MG-3.2 medium show that deletion of afsS drastically reduces actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin production (although it does not suppress it) and that complementation with the gene restores wild-type production levels. Obviously, the antibiotic production in the ΔafsS mutant is culture medium dependent.

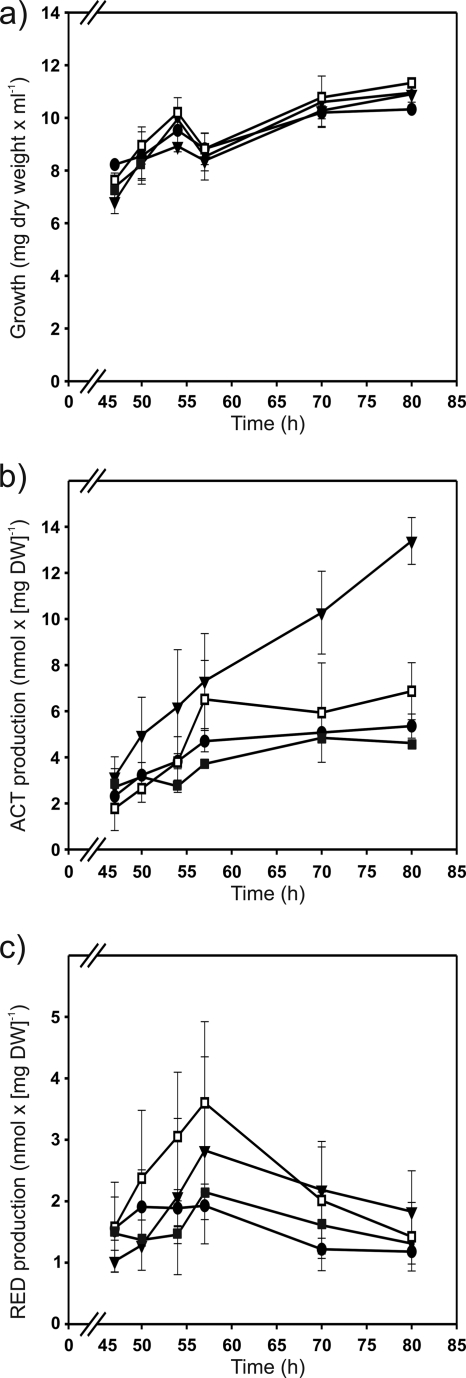

Fig. 5.

Growth (a), actinorhodin (ACT) production (b), and undecylprodigiosin (RED) production (c) of S. coelicolor M513 (ΔafsR mutant; white squares) and the complemented strains M513/pARint-afsS (black circles), M513/pARint-afsS-M5 (black squares), and M513/pARint-afsS-M16 (black inverted triangles) grown on MG-3.2. Error bars correspond to the standard errors of the means from three biological replicates.

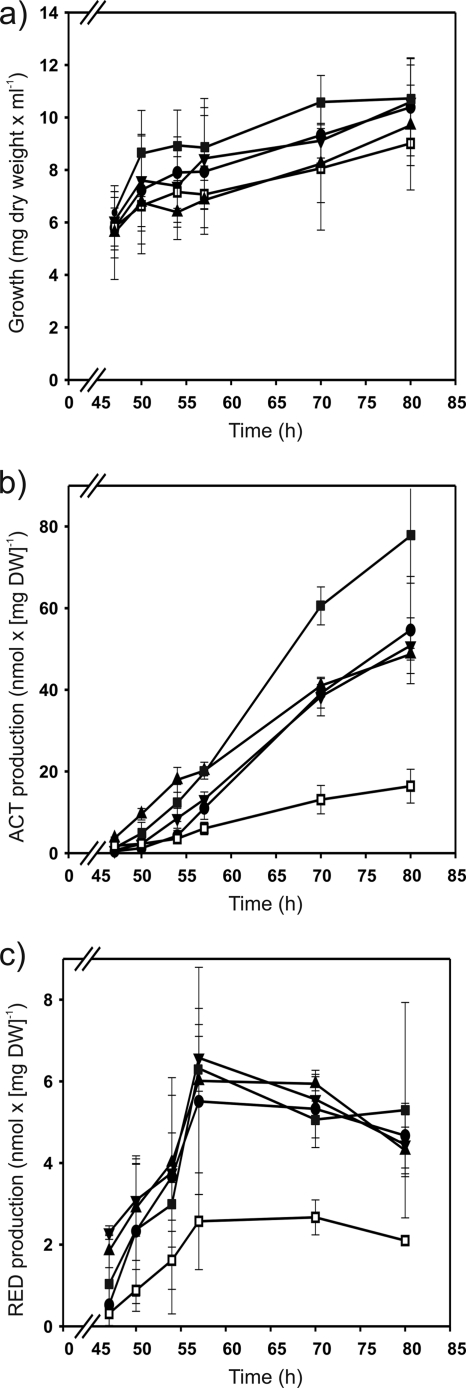

Fig. 6.

Growth (a), actinorhodin production (b), and undecylprodigiosin production (c) of S. coelicolor M145 (parental strain; black triangles), M952 (ΔafsS mutant; white squares), and the complemented strains M952/pARint-afsS (black circles), M952/pARint-afsS-M5 (black squares), and M952/pARint-afsS-M16 (black inverted triangles) grown on MG-3.2. Error bars correspond to the standard errors of the means from three biological replicates.

In addition, Fig. 6b shows that complementation of the ΔafsS mutant with the “superAfsR” (M5) afsS gene significantly increases actinorhodin production in comparison with the level achieved by introduction of the native gene or the “superPhoP” afsS gene. This result indicates that AfsR is a stronger activator for afsS than PhoP. In fact, the actinorhodin production of the strain transformed with the “superAfsR” gene is also higher than that of the wild-type strain (1.5 and 1.6 times higher at 70 and 80 h, respectively). However, as with the “superPhoP” construction in the ΔafsR strain, no significant differences in undecylprodigiosin production were observed among the different ΔafsS complemented strains (Fig. 5c and Fig. 6c).

In summary, we conclude that the high activities of the “superAfsR” and “superPhoP” promoters correlate with an increase of actinorhodin production and that, as indicated by other authors, AfsS seems to regulate actinorhodin production to a greater extent than that of undecylprodigiosin, which is also the case with AfsR (6, 15, 17, 34).

DISCUSSION

Production of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites plays an essential role in bacterial interactions with other living beings; therefore, the expression of the antibiotic biosynthetic genes has to be tightly controlled. The genetic control includes several pathway-specific, broad-range, and global regulators, which in turn respond to different physiological signals, such as phosphate starvation (2, 21). The phosphate starvation response in Streptomyces is mediated by PhoP, a transcriptional regulator which belongs to the OmpR family (31, 36, 37). The DNA-binding domain of OmpR consists of three α-helices packed against two antiparallel β-sheets, forming a winged helix-turn-helix (23).

On the other hand, the wide-range transcriptional regulator AfsR consists of three major functional regions: the 270 N-terminal residues, which have the same domain structure as Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory proteins (SARPs); the central ATPase domain; and a C-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR). SARPs are characterized by a DNA-binding domain that resembles that of OmpR and by an accompanying bacterial transcriptional activation domain, BTAD (39, 44).

Traditionally, the AfsK/AfsR/AfsS system was thought to comprise a linear signal transduction system for secondary metabolism in Streptomyces (10). However, in spite of its apparently linear hierarchy, the interaction of these regulators with other regulatory proteins was later reported in S. coelicolor (11, 22, 34). AfsR can be phosphorylated by kinases other than AfsK (35), and in turn, AfsR is able to regulate antibiotic production mediated or not by AfsS (15). Thus, protein binding analyses with purified AfsR showed that AfsR is able to interact with the promoters of genes other than afsS, such as pstS, phoRP (34), and glnR (data not shown). Moreover, transcriptomic analyses revealed the implication of AfsS in the regulation not only of genes involved in secondary metabolism but also of genes involved in phosphate, nitrogen, and sulfate assimilation (17). In S. lividans, the transcription of afsS is modulated by the carbon source of the culture medium (13). In addition, afsS can be activated by proteins other than AfsR, as has been shown in a ΔafsR background (34). There are three afsR homologous genes in the S. coelicolor genome (1), but only AfsR (which is linked to afsS) has been reported to bind the afsS promoter gene (15). On the other hand, results from EMSA and reporter (luciferase) studies have demonstrated that PhoP interferes with the action of two different regulators, AfsR (34) and GlnR (32). PhoP, but not GlnR (data not shown), is able to bind to the afsS promoter. Overall, it can be concluded that these regulators are involved in a regulatory network mechanism in which multiple interactions between the regulators and other proteins occur.

In this study, using ΔafsR and ΔphoP strains and a ΔafsR ΔphoP double mutant, in combination with mutant afsS promoters that show affinity toward only one or neither of the proteins AfsR and PhoP, we have proven that PhoP is able to activate afsS transcription. Thus, almost null afsS promoter activity was detected in the ΔafsR ΔphoP strain. The same occurred in the mutated afsS promoters that were unable to bind either of these two proteins. The highest promoter activities were observed with the promoters that bind only one protein (M5 or M16), with M5 (named “superAfsR”) being the best one. In fact, by improving the PhoP recognition sequence (mutant sequence M16), we observed increased transcription of afsS in a ΔafsR strain. In addition, we found that the greater ability of AfsR to activate afsS expression (mutant sequence M5) resulted in an increase of actinorhodin production.

The effects of molecular mechanisms of the afsS-encoded protein on the regulation of secondary metabolism are still unknown. Previous reports (6, 15, 17, 34), as well as the results of this work, indicate that AfsS regulates mainly the actinorhodin production in S. coelicolor. There is not always a correlation between afsS expression and antibiotic production. Thus, the afsS promoter activity of the ΔphoP strain was higher than that of the wild type, but the antibiotic production was lower in this mutant. The same lack of strict correlation was observed when limited and replete phosphate cultures of both wild-type and ΔafsR strains were compared (34), suggesting alternative control points of the antibiotic pathway. In this study, we have determined the positive correlation between higher afsS promoter activities (those of the “superAfsR” and “superPhoP” promoters) and higher actinorhodin production (Fig. 5b and 6b), although the promoter activities and the actinorhodin production were not proportional. The undecylprodigiosin production was not affected.

The main conclusion from this study is that both AfsR and PhoP stimulate afsS transcription in a competitive manner, but to different extents, with AfsR being a more potent activator of afsS than PhoP. A similar transcriptional regulatory mechanism in E. coli was described previously by Peeters et al. (27). These authors demonstrated that the Lrp and ArgP regulators act as competitive activators on a single promoter, with each regulator being more potent in the absence of the other. The molecular basis of this interference resides in the reciprocal inhibition of Lrp and ArgP binding to overlapping targets in the argO promoter region.

Although the argO gene of E. coli (codes for an l-arginine exporter) and the afsS gene of S. coelicolor (encoding a small protein involved in secondary metabolism) have different functions, they share almost identical features in their regulation mechanisms, as follows. (i) Both genes are regulated by a specific activator protein (ArgP and AfsR, respectively, for argO and afsS) and a global regulator which responds to nutritional conditions (Lrp and PhoP, respectively). (ii) ArgP and AfsR form a unique DNA/protein complex in EMSA experiments, while Lrp and PhoP bind cooperatively to multiple binding sites, forming several DNA/protein complexes (Fig. 2). (iii) The binding of ArgP and Lrp to argO and the binding of AfsR and PhoP to afsS are mutually inhibitory. (iv) Both pairs of regulators (ArgP-Lrp and AfsR-PhoP) behave as competitive activators of argO and afsS, respectively. (v) The specific activators ArgP and AfsR are more potent activators of argO and afsS than the global regulators Lrp and PhoP, respectively.

The fact that two very different systems and organisms share similar regulatory mechanisms suggests that the competitive activation of two regulators on a single promoter is a useful mechanism in bacteria, which may serve to integrate different signal inputs on expression of a key regulatory gene without altering too much the proper level of transcription of that regulatory gene. An accumulative rather than competitive effect of the two regulatory proteins would result in an abnormally high expression of afsS that might hamper proper cell development in nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was supported by grant CICYT Consolider Project Bio2006-14853-O2-1 from the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain and by the SYSMO STREAM project of the European Union (GEN2006-27745-E/SYS). Fernando Santos-Beneit was supported by a contract of the Junta de Castilla y León project.

We thank S. Horinouchi for providing the plasmid pET16-afsRΔTPR and M. Bibb for strain S. coelicolor M952.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bentley S. D., et al. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bibb M. J. 2005. Regulation of secondary metabolism in streptomycetes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Browning D. F., Busby S. J. 2004. The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiu J., March P. E., Lee R., Tillett D. 2004. Site-directed, ligase-independent mutagenesis (SLIM): a single-tube methodology approaching 100% efficiency in 4 h. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e174–e179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doull J. L., Vining L. C. 1991. Culture conditions promoting dispersed growth and biphasic production of actinorhodin in shaken cultures of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 65:265–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Floriano B., Bibb M. 1996. afsR is a pleiotropic but conditionally required regulatory gene for antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 21:385–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horinouchi S., Hara O., Beppu T. 1983. Cloning of a pleiotropic gene that positively controls biosynthesis of A-factor, actinorhodin, and prodigiosin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 155:1238–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horinouchi S., Malpartida F., Hopwood D. A., Beppu T. 1989. afsB stimulates transcription of the actinorhodin biosynthetic pathway in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and Streptomyces lividans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 215:355–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horinouchi S. 2003. AfsR as an integrator of signals that are sensed by multiple serine/threonine kinases in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 30:462–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang J., et al. 2005. Cross-regulation among disparate antibiotic biosynthetic pathways of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1276–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kieser T., Bibb M. J., Buttner M. J., Chater K. F., Hopwood D. A. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim E. S., Hong H. J., Choi C. Y., Cohen S. N. 2001. Modulation of actinorhodin biosynthesis in Streptomyces lividans by glucose repression of afsR2 gene transcription. J. Bacteriol. 183:2198-2203 (Erratum, 183:2969.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee J., Hwang Y., Kim S., Kim E., Choi C. 2000. Effect of a global regulatory gene, afsR2, from Streptomyces lividans on avermectin production in Streptomyces avermitilis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 89:606–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee P.-C., Umeyama T., Horinouchi S. 2002. afsS is a target of AfsR, a transcriptional factor with ATPase activity that globally controls secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 43:1413–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee Y., Kim K., Suh J.-W., Rhee S., Lim Y. 2007. Binding study of AfsK, a Ser/Thr kinase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and S-adenosyl-L-methionine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 266:236–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lian W., et al. 2008. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis reveals that a pleiotropic antibiotic regulator, AfsS, modulates nutritional stress response in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). BMC Genomics 9:56–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacNeil D. J., et al. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maharjan S., Oh T.-J., Lee H. C., Sohng J. K. 2009. Identification and functional characterization of an afsR homolog regulatory gene from Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC 15439. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Makitrynskyy R., et al. 2010. Genetic factors that influence moenomycin production in streptomycetes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37:559–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martín J. F., Liras P. 2010. Engineering of regulatory cascades and networks controlling antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13:263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martín J. F., et al. 2010. Cross-talk of global nutritional regulators in the control of primary and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces. Microb. Biotechnol. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00235.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martínez-Hackert E., Stock A. M. 1997. The DNA-binding domain of OmpR: crystal structures of a winged helix transcription factor. Structure 5:109–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsumoto A., Hong S. K., Ishizuka H., Horinouchi S., Beppu T. 1994. Phosphorylation of the AfsR protein involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces species by a eukaryotic-type protein kinase. Gene 146:47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsumoto A., Ishizuka H., Beppu T., Horinouchi S. 1995. Involvement of a small ORF downstream of the afsR gene in the regulation of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Actinomycetologica 9:37–43 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parajuli N., et al. 2005. Identification and characterization of the afsR homologue regulatory gene from Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 27952. Res. Microbiol. 156:707–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peeters E., Le Minh P. N., Foulquie-Moreno M., Charlier D. 2009. Competitive activation of the Escherichia coli argO gene coding for an arginine exporter by the transcriptional regulators Lrp and ArgP. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1513–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pérez-Redondo R., Santamarta I., Bovenberg R., Martín J. F., Liras P. 2010. The enigmatic lack of glucose utilization in Streptomyces clavuligerus is due to inefficient expression of the glucose permease gene. Microbiology 156:1527–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajkarnikar A., Kwon H.-J., Ryu Y.-W., Suh J.-W. 2006. Catalytic domain of AfsKav modulates both secondary metabolism and morphologic differentiation in Streptomyces avermitilis ATCC 31272. Curr. Microbiol. 53:204–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rajkarnikar A., Kwon H.-J., Ryu Y.-W., Suh J.-W. 2007. Two threonine residues required for the role of AfsKav in controlling morphogenesis and avermectin production in Streptomyces avermitilis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17:1563–1567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rodríguez-García A., Barreiro C., Santos-Beneit F., Sola-Landa A., Martín J. F. 2007. Genome-wide transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of the primary response to phosphate limitation in Streptomyces coelicolor M145 and in a ΔphoP mutant. Proteomics 7:2410–2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodríguez-García A., Sola-Landa A., Apel K., Santos-Beneit F., Martín J. F. 2009. Phosphate control over nitrogen metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor: direct and indirect negative control of glnR, glnA, glnII and amtB expression by the response regulator PhoP. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:3230–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Santos-Beneit F., Rodríguez-García A., Franco-Domínguez E., Martín J. F. 2008. Phosphate-dependent regulation of the low- and high-affinity transport systems in the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology 154:2356–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Santos-Beneit F., Rodríguez-García A., Sola-Landa A., Martín J. F. 2009. Cross-talk between two global regulators in Streptomyces: PhoP and AfsR interact in the control of afsS, pstS and phoRP transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 72:53–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sawai R., Suzuki A., Takano Y., Lee P. C., Horinouchi S. 2004. Phosphorylation of AfsR by multiple serine/threonine kinases in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Gene 334:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sola-Landa A., Moura R. S., Martín J. F. 2003. The two-component PhoR-PhoP system controls both primary metabolism and secondary metabolite biosynthesis in Streptomyces lividans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:6133–6138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sola-Landa A., Rodríguez-García A., Franco-Domínguez E., Martín J. F. 2005. Binding of PhoP to promoters of phosphate-regulated genes in Streptomyces coelicolor: identification of PHO boxes. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1373–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sola-Landa A., Rodríguez-García A., Apel A. K., Martín J. F. 2008. Target genes and structure of the direct repeats in the DNA-binding sequences of the response regulator PhoP in Streptomyces coelicolor. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:1358–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tanaka A., Takano Y., Ohnishi Y., Horinouchi S. 2007. AfsR recruits RNA polymerase to the afsS promoter: a model for transcriptional activation by SARPs. J. Mol. Biol. 369:322–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Umeyama T., Lee P. C., Ueda K., Horinouchi S. 1999. An AfsK/AfsR system involved in the response of aerial mycelium formation to glucose in Streptomyces griseus. Microbiology 145:2281–2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Umeyama T., Horinouchi S. 2001. Autophosphorylation of a bacterial serine/threonine kinase, AfsK, is inhibited by KbpA, an AfsK-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 183:5506–5512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Umeyama T., Lee P. C., Horinouchi S. 2002. Protein serine/threonine kinases in signal transduction for secondary metabolism and morphogenesis in Streptomyces. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 59:419–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vögtli M., Chang P. C., Cohen S. N. 1994. afsR2: a previously undetected gene encoding a 63-amino-acid protein that stimulates antibiotic production in Streptomyces lividans. Mol. Microbiol. 14:643–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wietzorrek A., Bibb M. 1997. A novel family of proteins that regulates antibiotic production in streptomycetes appears to contain an OmpR-like DNA-binding fold. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1181–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]