Abstract

Organic compounds exhibit various levels of toxicity toward living organisms based upon their ability to insert into biological membranes and disrupt normal membrane function. The primary mechanism responsible for organic solvent tolerance in many bacteria is energy-dependent extrusion via efflux pumps. One such bacterial strain, Pseudomonas putida S12, is known for its high tolerance to organic solvents as provided through the SrpABC resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family efflux pump. To determine how two putative regulatory proteins (SrpR and SrpS, encoded directly upstream of the SrpABC structural genes) influence SrpABC efflux pump expression, we conducted transcriptional analysis, β-galactosidase fusion experiments, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and pulldown analysis. Together, the results of these experiments suggest that expression of the srpABC operon can be derepressed by two distinct but complementary mechanisms: direct inhibition of the SrpS repressor by organic solvents and binding of SrpS by its antirepressor SrpR.

INTRODUCTION

Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for organic solvent tolerance in Gram-negative bacteria. These include the formation of membranous vesicles (21), organic solvent metabolism (5, 28), and increasing membrane rigidity (16, 17, 29, 40). Although a permeability barrier in the form of a cellular membrane is indispensable for bacteria to resist the toxic effects of organic solvents, it is a relatively passive mechanism, and many solvents can diffuse across this barrier over time (7, 29, 30). Consequently, extrusion of toxic solvents by membrane-spanning protein complexes, termed efflux pumps, is a crucial active mechanism to remove these compounds from the bacterial cell.

Efflux pumps are divided into five families: the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family, and the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family (25). To be effective, bacterial efflux pumps are necessarily located in the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria or the cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria, and their function is energy dependent (23, 25). The efflux of antimicrobial compounds as a resistance mechanism was first reported for tetracycline in Escherichia coli (27) and was later discovered in many bacteria resistant to antimicrobials. During the past decade, several efflux systems have also been discovered to be involved in bacterial tolerance to organic solvents (2), including the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in E. coli (25), the MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24), the SrpABC efflux pump in Pseudomonas putida S12 (19, 20), and the TtgABC, TtgDEF, and TtgGHI efflux pumps in P. putida DOT-T1E (30, 32). The characterization of these efflux pump systems has helped to elucidate bacterial mechanisms of tolerance to extremely high concentrations of toxic organic solvents.

The expression of most RND-type multidrug and solvent efflux systems is controlled by both complex global regulatory networks and a local repressor (10, 13, 25); the gene for the latter is typically situated upstream and is transcribed divergently from the efflux pump genes (22, 39). For example, the TtgGHI efflux pump of P. putida DOT-T1E (the system most closely related to the SrpABC pump in P. putida S12) is locally regulated by the repressor TtgV (33). The genes ttgV and ttgW (a pseudogene that does not regulate pump expression) are located upstream from the structural genes ttgGHI and are transcribed divergently from this operon (33). A mutant deficient in ttgV, but not in ttgW, was shown to possess much higher expression from the ttgGHI and ttgWV promoters, suggesting that ttgV encodes a repressor for the expression of both ttgGHI and itself (32, 33). Further studies revealed that TtgV is an IclR family protein that represses the transcription of these genes by binding to the ttgV-ttgG intergenic region, thereby preventing the binding of RNA polymerase to promoter sequences. Substrates of the TtgGHI pump such as 1-hexanol can release TtgV from its DNA-binding site and induce the expression of the efflux pump (11). More recently, Guazzaroni et al. (12) identified additional compounds that play a role similar to that of 1-hexanol in inducing TtgGHI expression and established a clear relationship between a compound's affinity for TtgV and its efficiency at inducing ttgGHI expression.

The genes encoding the SrpABC efflux pump in P. putida S12 possess two putative regulatory genes upstream and divergently transcribed from srpABC: srpS (putatively encoding an IclR family regulator) and srpR (putatively encoding a TetR family repressor). Wery et al. (41) discovered a 2.6-kb insertion sequence, ISS12, that can insert into the repressor gene srpS and block its expression, suggesting that an insertion sequence may also be involved in the regulation of this RND-type efflux pump. The discovery of a second insertion sequence, ISPpu21, that inserts into srpS and derepresses efflux pump expression (37) confirms that SrpS is the srpABC efflux pump repressor but eliminates the hypothesis that ISS12 is a specific srpS mutator element (41). No insertion sequences were detected inserted in srpS when cells were treated with 1% (vol/vol) toluene shocks, whereas approximately one-third of the cells that survived a 20% (vol/vol) toluene shock carried either ISPpu21 (37) or ISS12 (41) within srpS. Mutant S12TS, carrying a copy of ISPpuS12 within srpS, was shown to have a 17,000-fold increased survival frequency to toluene shock in comparison with wild-type S12. The increased survival frequency in S12TS dropped to wild-type levels when the strain was complemented with srpS but not with srpR. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that SrpS, but not SrpR, is the repressor of SrpABC. Importantly, this study indicated that two-thirds of the cells that survived extreme toluene levels do not require srpS gene inactivation.

The objective of this study was to determine how the putative regulators SrpS and SrpR are involved in controlling expression of the srpABC genes. Since the srpABC-srpSR gene cluster and the ttgGHI-ttgVW gene cluster are highly homologous, it was expected that SrpSR would perform in the same manner as TtgVW (SrpR having little to no importance). However, the results presented here suggest that SrpS and SrpR function together to control the production of SrpABC and that this activity is affected by the presence of organic solvents in the cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The E. coli and P. putida strains and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (34). Solid medium contained 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. When required for selection, the culture medium was supplemented with different antibiotics including ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), gentamicin (25 μg/ml), and streptomycin (150 μg/ml). E. coli and P. putida cultures were incubated at 37°C and 30°C, respectively. Liquid cultures were shaken on a horizontal shaker at 200 rpm. When P. putida culture plates were supplied with toluene via the gas phase, a sealed glass chamber was used, and saturated toluene vapor was achieved by adding toluene to the bottom of the chamber. When P. putida liquid cultures were supplied with certain concentrations of toluene, the culture flasks were sealed with foil-covered stoppers.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | λ− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169recA1endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44thi-1gyrArelA1 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli BL21 | F−ompThsdS (rB− mB−) gal | Amersham |

| E. coli M15 | Nals Sms Rifs Thi− Lac− Ara+ Gal+ Mtl− F− RecA+ Uvr+ Lon+ | Qiagen |

| P. putida S12 | Wild-type; srpABC+srpR+srpS+ | 14 |

| P. putida JK1 | srpB::TnMod-KmO | 19 |

| P. putida S12 lacZ | srpABC+srpS+srpR+lacZ, in a single-copy transcriptional fusion behind PsrpA | This study |

| P. putida SrpS−lacZ | srpABC+srpS mutant srpR+lacZ, in a single-copy transcriptional fusion behind PsrpA | This study |

| P. putida SrpR−lacZ | srpABC+srpS+srpR mutant lacZ, in a single-copy transcriptional fusion behind PsrpA | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | TOPO TA cloning vector for direct insertion of PCR products, blue/white screening; Apr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pJD101 | Derived from a BamHI digestion of P. putida JK1 chromosome; contains srpR through a partial open reading frame of TnMod-KmO plasposon-mutated srpB | 19 |

| pJD102 | Derived from a PstI digestion of P. putida JK1 chromosome; contains a partial open reading frame of TnMod-KmO plasposon-mutated srpB through srpC | 19 |

| pJD203 | Constructed by digestion (EcoRV and BamHI) and ligation of pJD101 and pJD102; contains a partial open reading frame of TnMod-KmO plasposon-mutated srpB through srpC | This study |

| pJD500 | Apr Kmr; promoterless trp-lacZ fusion downstream of the srpA promoter, for the construction of single-copy chromosomal lacZ reporter fusions | This study |

| pGEX-4T-1 | Apr; cloning vector for overexpression of N-terminal GST fusion proteins | Amersham |

| pGEX-srpR | Entire coding region of srpR cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (BamHI-EcoRI) | This study |

| pQE31 | Apr; cloning vector for overexpression of N-terminal His6 fusion proteins | Qiagen |

| pQE31-srpS | Entire coding region of srpS cloned into pQE31 (BamHI-KpnI) | This study |

| pQE31-arpR | Entire coding region of arpR cloned into pQE31 (SstI-PstI) | This study |

| pREP4 | Kmr; introduced into E. coli M15; constitutively expresses LacI | Qiagen |

DNA techniques.

Total genomic DNA was isolated from P. putida strains by the hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) procedure (3). Plasmid isolations were performed with a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen Inc., Mississauga, ON). Digestions with restriction enzymes were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Ligations were performed with T4 DNA ligase (Promega, Madison, WI). Chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells (Invitrogen) were transformed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Electroporation of P. putida and E. coli strains was performed as described previously (8) using a MicroPulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Genetic mutations in srpS and srpR were constructed in the S12 chromosome using a standard technique (34): the double crossover of a nonreplicating plasmid carrying an amplified S12 gene fragment with an internal antibiotic resistance marker insertion (9). Based on previous reports (41) and unpublished data, it was determined that due to polar effects, the srpS knockout is, in fact, an srpS srpR double mutant. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels using a GeneClean II kit (Q. BIOgene, Carlsbad, CA). DNA fragments amplified by PCR for use in sequencing reactions and restriction enzyme digestion were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). Samples for sequencing were prepared with an Amersham DYEnamic ET kit (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) and provided to the University of Alberta Molecular Biology Services Unit (MBSU) for automated sequencing using an ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Nucleotide and amino acid sequence analysis was carried out with the BLAST program on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) server (1).

RNA preparation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA from P. putida S12 was isolated with an RNeasy Mini Kit and RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen) was used to eliminate DNA contamination. Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with 1 μg of RNA/ml in a 20-μl reaction volume using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen), and PCR amplification of the cDNA was performed with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen). The first-strand cDNA synthesis step was conducted at 55°C for 50 min, and the cycling conditions for PCR amplification were as follows: a 2-min denaturation period at 94°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min per kb of DNA template at 68°C; and a final 2-min extension period at 68°C. Positive and negative controls were performed in all assays. The primers and their uses in this study are listed in Table 2. The concentration of toluene used in all experiments is above its solubility limit in an aqueous solution (0.47 g/liter). To ensure that SrpS came into contact with toluene in the in vitro RT-PCR assays, we used an excess of toluene at 6 M (20%, vol/vol). In order to ensure cell viability throughout our reporter fusion experiments (see below), the toluene concentration was reduced to 6 mM, a concentration just over the solubility limit of toluene (0.552 g/liter).

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Use |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | TTGGAGGTGAATACTGG | With primer S2 to PCR amplify a 205-bp fragment within srpS; used in RT-PCR to amplify the first-strand cDNA of srpS |

| S2 | TCGGTCTGCCTGGCTTCT | With primer S1 or with R0 in RT-PCR to amplify a 940-bp fragment overlapping srpS and srpR |

| R0 | CGCCGATTGAGGTTTGAAG | RT-PCR to amplify the first-strand cDNA of srpR or srpSR; used with primer R2 to amplify a 450-bp fragment within srpR |

| R2 | AGGCGGAGGAGACAAGA | With primer R0 to PCR amplify the cDNA of srpR |

| SP1 | AACCTGTTCTTTCTCACCAC | With AP2, PCR amplification of a 490-bp fragment in the srpS-srpA intergenic region used in EMSAs |

| AP2 | TTCTTCCAGAGCGTTGATGA | With SP1, PCR amplification of a 490-bp fragment in the srpS-srpA intergenic region used in EMSAs |

| SF-01 | ATGTCGACTACAGTGGCGGC | With SR-02, PCR amplification of an 831-bp fragment encompassing the coding sequence of srpS to clone into pMAL-c2X |

| SR-02 | TTAAGCTTCTAGGGAGCTTTCTTC | With SF-01, PCR amplification of an 831-bp fragment encompassing the coding sequence of srpS to clone into pMAL-c2X |

| RF-01 | TAGTCGACATGGCTAGAAAGACG | With RR-02, PCR amplifies a 642-bp fragment encompassing the coding sequence of srpR to clone into pMAL-c2X |

| RR-02 | ATAAGCTTTACTCGAAGGATTTGACTT | With RF-01, amplifies a 642-bp fragment encompassing the coding sequence of srpR to clone into pMAL-c2X |

| SR | ACCACTCTGCCTCACTTCG | RT-PCR to amplify the first-strand cDNA of srpS |

| SF0 | TGCTGAATCGTAATGCGGT | With primer SR to determine the transcription start site of srpS |

| SF1 | CCGTTGGTCGAGGTTTACC | With primer SR to determine the transcription start site of srpS |

| SF2 | CCAGAGCAGCCTCGATCA | With primer SR to determine the transcription start site of srpS |

| AR | CGTGGGTCAATCTGATAAAG | RT-PCR to amplify the first-strand cDNA of srpA |

| AF0 | ATCGCATAATGGTAGACTCT | With primer AR to determine the transcription start site of srpA |

| AF1 | AGACTCTACCGCATTACGAT | With primer AR to determine the transcription start site of srpA |

| AF2 | ATTACGATTCAGCAATAGCC | With primer AR to determine the transcription start site of srpA |

| AR5Sst | AAGAGCTCGATGGTCCGTC | PCR amplification of a 657-bp fragment encompassing the entire coding sequence of arpR to clone into pQE31 |

| AR3Pst | GGCTGCAGCAAAGTGTCAT | |

| S5Bam | AAGGATCCTATGAACCAATCA | PCR amplification of a 794-bp fragment encompassing the entire coding sequence of srpS to clone into pQE31 |

| S3Kpn | CTTATCTAGGGTACCTTCTTCGAC | |

| R5Bam | AAGGATCCATGGCCAGAAAGAC | PCR amplification of a 649-bp fragment encompassing the entire coding sequence of srpR to clone into pGEX-4T-1 |

| R3Eco | GGGAATTCGGATTTGACTTGC |

Engineered restriction sites are underlined.

β-Galactosidase assays.

The plasmid pJD500, based on the kanamycin- and ampicillin-resistant narrow-host range vector pGEM-5Zf(+) (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), was constructed containing a promoterless trp-lacZ gene transcriptionally fused to the srpA gene downstream of the srpA promoter. To create the srpA-lacZ reporter gene fusion strains, P. putida S12 lacZ, an SrpS− lacZ strain, and an SrpR− lacZ strain, pJD500 was transformed by electroporation using standard techniques (8) into wild-type P. putida S12 and the S12 SrpS− and S12 SrpR− mutants. Transformants were selected using kanamycin antibiotic selection. Chromosomal PCR analysis was performed to verify the occurrence of a single chromosomal homologous recombination event, leaving a functional srpABC efflux pump operon. β-Galactosidase assays, including the calculation of Miller units, were performed according to the method of Slauch and Silhavy (36). Briefly, formation of o-nitrophenol (ONP) was monitored by measuring A420. Readings were taken for a 60-min period, and the β-galactosidase activity was determined by calculating the ratio of A420 to the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The cultures used in these assays were supplemented with or without 6 mM toluene. All assays were averages of at least three independent trials.

Overexpression and purification of MBP-SrpS and MBP-SrpR.

The putative regulators SrpS and SrpR were overexpressed in E. coli DH5α as N-terminal maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins for use in the in vitro protein-DNA binding studies. The srpS gene was PCR amplified from the P. putida S12 chromosome using the primers SF-01 and SR-02, which contain engineered SalI and HindIII sites, respectively. The amplified fragment was digested accordingly and cloned in frame downstream of the malE gene in the plasmid pMAL-c2X (New England BioLabs, Mississauga, ON). Likewise, the srpR gene was cloned into pMAL-c2X using the primers RF-01 and RR-02, which also contain engineered SalI and HindIII sites, respectively. To overexpress the fusion proteins, E. coli DH5α cells transformed with the respective plasmids were grown in 1 liter of LB medium with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6 and induced with 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested after 6 h of induction at 37°C, resuspended in 30 ml of column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) containing 0.01 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and stored at −20°C overnight. Subsequently, the cells were thawed on ice and lysed by sonication in four pulses of 15 s using a Branson Sonifier 450. Following centrifugation at 9,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant containing the soluble protein fraction was diluted 1:2 with column buffer. The column buffer used throughout the protein purification steps was supplemented with 0.01 mM PMSF. Purification of the fusion protein from the crude extract was performed in a 20-ml syringe containing 15 ml of amylase resin (New England BioLabs, Mississauga, ON). The resin was initially washed with 8 column volumes of column buffer. Subsequently, the diluted crude extract was added, and the resin was washed with 12 column volumes of column buffer. The fusion protein bound to the amylase resin was eluted in 3-ml fractions using column buffer containing 10 mM maltose. Samples were analyzed by measuring the A280, and the purified protein fractions were pooled and quantified using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Quantified fusion proteins were divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

A 490-bp DNA fragment within the srpS-srpA intergenic region, containing the promoters of both srpS and srpA and the regulatory region containing potential operators, was PCR amplified from the plasmid pJD101 using the primers SP1 and AP2. The amplified fragment was purified and end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP. Binding reactions were carried out in 20-μl volumes and consisted of increasing amounts of purified MBP-SrpS or MBP-SrpR, 1× binding buffer [65 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 0.2 M KCl, 25 mM MgCl2 · 6H2O, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.25% NP-40, 12.5% glycerol, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC)], labeled target DNA (2 × 106 to 4 × 106 cpm), and sterile Milli-Q H2O to adjust the volume. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min, followed by the addition of a one-fifth volume of 5× loading buffer. The samples were then separated by electrophoresis in a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide–1× TAE (Tris-acetate EDTA) gel before exposure to X-ray film and visualization by autoradiography. Competition assays were performed under the same conditions with the addition of competitive or noncompetitive DNA. When toluene was included in the assays, it was added to the reaction mixtures either prior to or following the binding reaction.

Overexpression and purification of GST-SrpR, His-SrpS, and His-ArpR.

The srpR gene was PCR amplified from pJD101 using the primers R5Bam and R3Eco, which contain engineered BamHI and EcoRI sites, respectively. The amplified fragment was digested accordingly and cloned in frame downstream of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene in the plasmid pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham), resulting in the N-terminal GST-tagged construct pGEX-srpR. The srpS gene was PCR amplified from pJD101 using the primers S5Bam and S3Kpn, which contain engineered BamHI and KpnI sites, respectively. The amplified fragment was digested accordingly and cloned in frame downstream of the 6× histidine gene in the plasmid pQE31 (Qiagen), resulting in the N-terminal His6-tagged construct pQE31-srpS. Likewise, arpR was cloned into pQE31 with the primers AR5Sst and AR3Pst and used as a negative control for the pulldown assay. E. coli BL21 was used to express GST and GST fusion proteins, and E. coli M15(pREP4) was used to express His6 fusion proteins. To induce expression of the fusion proteins, E. coli cells transformed with the respective plasmids were grown at 37°C in 2× YT broth (1.6% [wt/vol] tryptone, 1.0% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.5% [wt/vol] NaCl) until the OD600 reached 0.7, and IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.05 mM. Incubation was continued for one additional hour at 30°C before the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer. The cells were then lysed by sonication, and the sonicates were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min to remove insoluble material. The supernatants were saved as the crude cell lysate samples. These total protein samples were quantified using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit and stored at −80°C before being used in the pulldown assay.

GST pulldown assays.

A test group (GST-SrpR and His-SrpS) and three negative-control groups (GST-SrpR and His-ArpR, GST and His-SrpS, and PBS buffer and His-SrpS) were assayed simultaneously in the pulldown experiments. Preliminary tests were performed to determine the concentrations of cell lysate samples to be used, such that the test group and control groups would contain the same amount of GST-SrpR and GST, as well as the same amount of His-SrpS and His-ArpR. Formal pulldown assays were then performed accordingly. One milliliter of 0.83 mg/ml cell lysate containing GST-SrpR, 1 ml of 0.14 mg/ml cell lysate containing GST, or 1 ml of PBS buffer was incubated with 20 μl of 50% glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham) at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were then washed twice with 1 ml of PBST (PBS and 0.05% Tween 20) and once with 1 ml of PBS. Following the wash steps, 1 ml of 0.22 mg/ml cell lysate containing His-SrpS or His-ArpR was added to the beads, and the samples were incubated with gentle agitation at 4°C for 2 h. Subsequently, the beads were washed twice with PBST and twice with PBS and heated in SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 95°C for 5 min. Finally, the beads were briefly pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by Western blotting. The His6 fusion proteins were detected by Penta-His Antibody (Qiagen) and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA). The pulldown assay results were the product of three independent trials.

RESULTS

Transcriptional analysis of the srpSR-srpABC gene cluster.

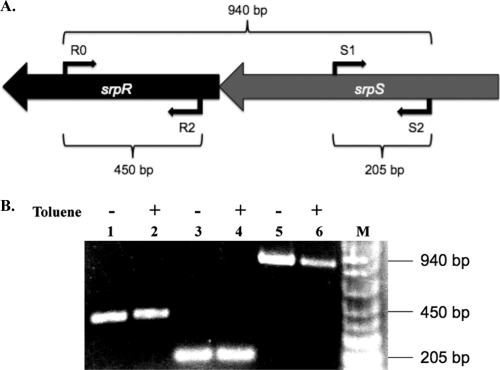

It is unclear whether srpR and srpS are coexpressed in the presence or absence of organic solvent. To analyze srpSR expression, total RNA was isolated from cells grown in the presence or absence of 20% (vol/vol) toluene, and RT-PCR assays were performed with primer pairs within srpR (primers R0 and R2), srpS (primers S1 and S2), and across srpSR (primers R0 and S2). srpR and srpS were transcribed as a single unit in both the presence and absence of toluene (Fig. 1), thus confirming that srpR and srpS are encoded on a polycistronic transcript.

Fig. 1.

RT-PCR analysis of srpSR in P. putida S12. (A) RT-PCR primers and amplified region. Primers R0 and R2 were used to amplify srpR, primers S1 and S2 were used to amplify srpS, and primers R0 and S2 were used to amplify srpSR. The expected fragment sizes are shown. (B) RT-PCR results. Lanes 1 and 2, srpR amplification; lanes 3 and 4, srpS amplification; lanes 5 and 6, srpR-srpS amplification; lane M, molecular size markers (1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder; Invitrogen) (0.1 kb to 1.0 kb shown). RNA templates in lanes 1, 3, and 5 were isolated from cells grown without toluene; RNA templates in lanes 2, 4, and 6 were isolated from cells grown with 20% (vol/vol) toluene. Negative controls without reverse transcriptase added were included with all of the reaction mixtures (data not shown).

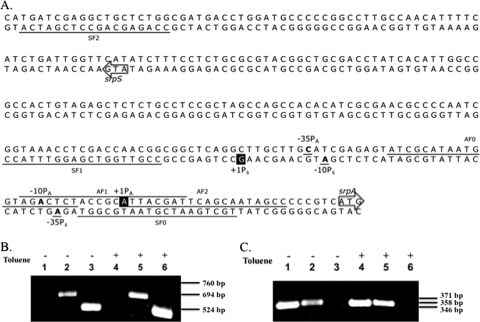

P. putida DOT-T1E is another solvent-tolerant P. putida strain. The TtgGHI efflux pump in this strain is highly homologous (98% nucleotide sequence identity) to the SrpABC efflux pump in P. putida S12 (32). The structural genes ttgGHI correspond to srpABC, and ttgV, encoding the repressor, and ttgW correspond to srpS and srpR, respectively. In an alignment of the srpS sequences with the ttgV sequence features identified by Rojas et al. (33), the transcription start site of ttgV corresponds to the highlighted G residue in Fig. 2A (+1PS), and the translation start codon of ttgV corresponds to the arrow labeled srpS in Fig. 2A. To determine if these sites are similarly important in the srpSR operon, RT-PCR assays were performed with primers upstream (primer SF0) and downstream (primers SF1 and SF2) of the position +1PS. Total RNA samples isolated from cells grown with or without 20% (vol/vol) toluene were used as templates, and srpS first-strand cDNA was amplified with primer SR. PCR amplification was then performed by adding primer SF0, SF1, or SF2. Amplification was achieved only when primers downstream of +1PS were used (SF1 and SF2), and no band was obtained with the primer upstream of +1PS (SF0) (Fig. 2B). This result confirms that the transcription start site of the srpSR operon is between SF1 and SF0 both in the presence and absence of toluene. Together with the ttgV bioinformatics comparisons, these RT-PCR results are consistent with the prediction that the G residue indicated by +1PS in Fig. 2A is the transcription start site of the srpSR operon.

Fig. 2.

Determination of the transcription start regions of the srpS and srpA genes in P. putida S12. (A) Overlap region of the srpS and srpA promoters. The translation start codons of srpS and srpA are indicated by arrows. The predicted transcription start sites for srpS and srpA (based on bioinformatics and RT-PCR analysis) are highlighted and designated +1PS and +1PA, respectively. The base pairs at the putative −10 and −35 positions of each promoter are bolded and underlined. The primers used in RT-PCR assays are underlined (or overlined for AF1), with names indicated in small font above or below the sequence. (B) RT-PCR results for determination of the transcription start region of srpS. Lanes 1 and 4, amplification with primer SF0 (expected size, 760 bp); lanes 2 and 5, amplification with primer SF1 (expected size, 694 bp); lanes 3 and 6, amplification with primer SF2 (expected size, 524 bp). (C) RT-PCR results for determination of the transcription start region of srpA. Lanes 1 and 4, amplification with primer AF2 (expected size, 346 bp); lanes 2 and 5, amplification with primer AF1 (expected size, 358 bp); lanes 3 and 6, amplification with primer AF0 (expected size, 371 bp). RNA templates in lanes 1, 2, and 3 of panels B and C were isolated from cells grown without toluene; RNA templates in lanes 4, 5, and 6 were isolated from cells grown with 20% (vol/vol) toluene.

Similarly, the transcription start region of the srpABC operon was determined. According to prior srpABC reverse transcriptase experiments in our lab and predictions based on the ttgGHI experiments by Guazzaroni et al. (11), the putative transcription start site of srpA in P. putida S12 is the A nucleotide indicated by +1PA in Fig. 2A. To confirm that the start site is in this region, RT-PCR assays were performed with primers upstream of +1PA (primer AF0), covering +1PA (primer AF1), and downstream of +1PA (primer AF2). Amplification was achieved only using primers AF1 or AF2 (Fig. 2C). Together with the bioinformatics comparisons, these RT-PCR results suggest that the A indicated by +1PA in Fig. 2A is the transcription start site of the srpABC operon.

SrpS is a repressor and SrpR is an antirepressor of the srpA promoter.

Based on the results of β-galactosidase assays, Rojas et al. (33) concluded that ttgV encodes a repressor that prevents expression of the ttgGHI operon, whereas ttgW does not play a significant role in regulation. The srpR and ttgW genes have 96% identity at the nucleotide level over the length of ttgW, but srpR encodes a 213-amino-acid protein, whereas ttgW encodes a significantly shorter 134-amino-acid protein. We performed β-galactosidase assays to determine the functions of SrpS and SrpR. The single-copy chromosomal srpA-lacZ reporter P. putida S12 lacZ, SrpS− lacZ, and SrpR− lacZ gene fusion strains were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. Table 3 shows the averages for at least three independent assays performed for each strain in the presence or absence of 6 mM toluene. In the wild-type background, expression from the srpA promoter was observed even in the absence of toluene (892 ± 13 Miller units). However, expression was increased approximately 6-fold with the addition of toluene (5,023 ± 363 Miller units). In the absence of toluene, expression from the srpA promoter increased approximately 5.5-fold in the srpS deletion background compared to the wild-type background. In the presence of toluene, expression from the srpA promoter failed to increase in the srpS deletion background, suggesting that toluene directly contributes to the inhibition of SrpS repressor activity in wild-type cells. Deletion of srpR caused expression from the srpA promoter to decrease almost 6-fold compared to the wild-type background in the absence of toluene (153 ± 7 versus 892 ± 13 Miller units) and approximately 3-fold in the presence of toluene (1,555 ± 95 versus 5,023 ± 363 Miller units). These results indicate that SrpR positively influences srpABC efflux pump gene expression in both the presence and absence of toluene.

Table 3.

Transcription from the srpA promoter in the presence or absence of toluene in srpS or srpR deletion backgrounds compared to the wild-type background

| P. putida strain | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Without toluene | With toluene | |

| S12 lacZ strain | 892 ± 13 | 5,023 ± 363 |

| SrpS−lacZ strain | 4,500 ± 223 | 4,528 ± 102 |

| SrpR−lacZ strain | 153 ± 7 | 1,555 ± 95 |

β-Galactosidase assays were performed in the srpA-lacZ reporter SrpS− lacZ, SrpR− lacZ, and S12 lacZ gene fusion strains in the presence or absence of 6 mM toluene. The values in the table are the averages of at least three independent assays followed by the standard deviations.

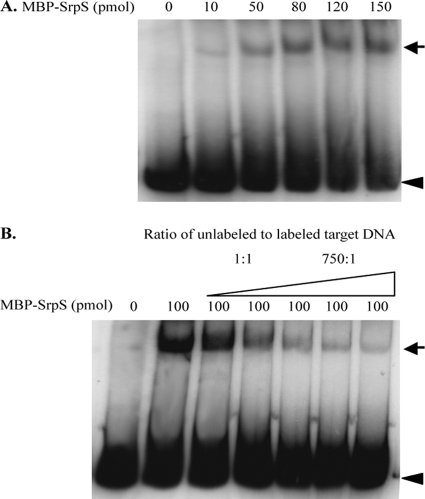

In vitro assay of the protein-DNA interactions between SrpS and SrpR and the srpS-srpA intergenic region.

To further investigate the regulatory mechanisms of SrpS and SrpR, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed to assess the interactions of the SrpS and SrpR proteins with the srpS-srpA intergenic region. A 490-bp DNA fragment within the srpS-srpA intergenic region was PCR amplified and end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP, and increasing amounts of purified MBP-SrpS or MBP-SrpR were allowed to bind to this fragment. When the labeled DNA was incubated with increasing amounts of MBP-SrpS, a single shifted band was observed (Fig. 3A). The shifted band appeared following addition of as little as 10 pmol of MBP-SrpS, and the intensity of the shifted band increased with the addition of increasing amounts of MBP-SrpS, suggesting that SrpS binds with high affinity to the target DNA within the srpS-srpA intergenic region. Competition assays were performed under the same conditions and a fixed amount of MBP-SrpS to determine if the binding was specific. When the 490-bp unlabeled DNA fragment was added to the reaction mixtures as a competitive inhibitor in ratios ranging from 1:1 to 750:1, a gradual decrease in intensity of the shifted band was observed (Fig. 3B). However, in a similar experiment where noncompetitive DNA [poly(dI-dC)] was added to the reaction mixtures, the intensity of the shifted band remained the same (data not shown). These results confirm that SrpS functions as a specific repressor that binds to an operator in the srpS-srpA intergenic region, repressing expression of the srpABC operon.

Fig. 3.

EMSAs used to assess the interaction of SrpS within the srpS-srpA intergenic region. (A) The 490-bp DNA fragment within the srpS-srpA intergenic region was end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP. Purified MBP-SrpS at the indicated amounts was allowed to bind to the labeled DNA fragment (2 × 106 to 4 × 106 cpm) in 1× binding buffer at 30°C for 30 min. (B) The 490-bp DNA fragment within the srpS-srpA intergenic region in both the unlabeled and labeled forms (with the ratio of unlabeled to labeled DNA ranging from 1:1 to 750:1) was mixed with 100-pmol samples of MBP-SrpS. The reaction mixtures were analyzed on a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide–1× TAE gel. The black arrows indicate the shifted band caused by the binding of SrpS to the target DNA. The arrowheads indicate the unbound DNA.

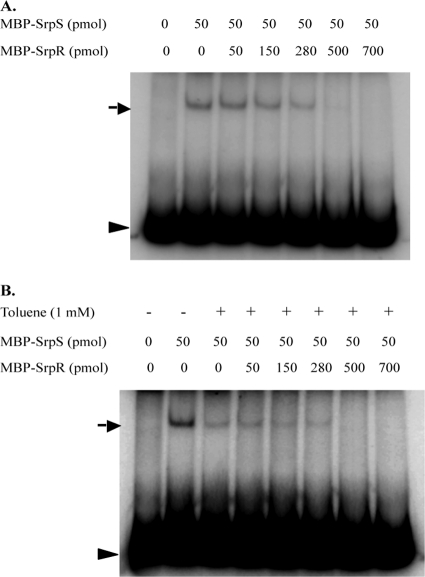

Several attempts were made to determine if SrpR binds to the same 490-bp DNA fragment as SrpS. EMSAs were initially performed using the same buffer and binding conditions as for SrpS, and subsequently several variations of buffer compositions, temperatures, toluene additions, and increased DNA fragment sizes were also tested. None of these experiments showed a band shift with MBP-SrpR. Because srpA-lacZ reporter results suggested that SrpR positively influences srpABC expression 2, but SrpR does not bind to the srpS-srpA intergenic region, we hypothesized that SrpR may act as an antirepressor that binds to SrpS, inhibiting SrpS binding to promoter DNA and derepressing transcription from the srpA promoter. To test this hypothesis, EMSAs were performed to determine if SrpR, with or without toluene, affected the binding of SrpS to the srpS-srpA intergenic region. A fixed amount of MBP-SrpS was allowed to bind to the labeled target DNA, and shifted bands were visualized following the addition of increasing amounts of MBP-SrpR (with the ratio of MBP-SrpS to MBP-SrpR ranging from 1:1 to 1:14). The samples were incubated at 30°C for 30 min to allow SrpR to interact with SrpS (Fig. 4). Another set of EMSAs was performed such that both 1 mM toluene and MBP-SrpR (with the ratio of MBP-SrpS to MBP-SrpR ranging from 1:1 to 1:14) were added simultaneously to the prebound MBP-SrpS–DNA reaction mixtures. The samples were incubated at 30°C for 30 min to allow SrpR to interact with SrpS (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, regardless of whether MBP-SrpR was added to the reaction mixtures after MBP-SrpS was allowed to bind to the DNA (Fig. 4) or MBP-SrpR and MBP-SrpS were added simultaneously (data not shown), the intensity of the DNA-SrpS band gradually decreased as the amount of MBP-SrpR added increased. Also, as shown in Fig. 4B, toluene exhibits a direct inhibitory effect on SrpS DNA binding, independent of the presence of SrpR (complete SrpS dissociation occurring at above 280 pmol of SrpR both in the presence (Fig. 4B), and absence (Fig. 4A) of toluene). Overall, these results indicate (i) that SrpR prevents the binding of SrpS to the srpS-srpA intergenic region, (ii) that SrpR is capable of dissociating SrpS prebound to this region, and (iii) that, consistent with the β-galactosidase assay results (Table 3), both toluene and SrpR have direct inhibitory effects on the binding of SrpS to its target DNA.

Fig. 4.

EMSAs used to assess if SrpR, in the presence or absence of toluene, affects the binding of SrpS within the srpS-srpA intergenic region. The 490-bp DNA fragment within the srpS-srpA region was end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP. Samples of MBP-SrpS at a fixed amount of 50 pmol were allowed to bind to the labeled DNA fragment (2 × 106 to 4 × 106 cpm) in 1× binding buffer at 30°C for 30 min. (A) Following the binding reaction, purified MBP-SrpR was added to the reaction mixtures in the indicated amounts and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. (B) Purified MBP-SrpR in the indicated amounts and toluene (final concentration of 1 mM) were added simultaneously to the reaction mixtures following the binding reaction and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were analyzed on a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide–1× TAE gel. The black arrows indicate the shifted band caused by the binding of SrpS to the target DNA. The arrowheads indicate the unbound DNA.

In vitro analysis of SrpR-SrpS protein-protein interactions.

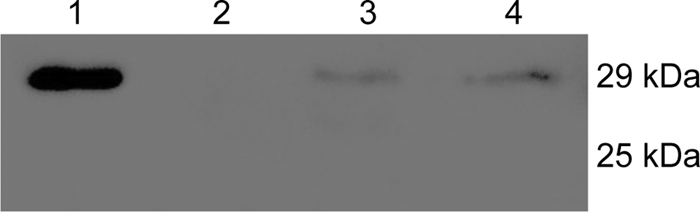

The EMSA results described above suggest that SrpR may act as a regulator that counteracts the repressor activity of SrpS. To test this hypothesis, an in vitro glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay was used to determine if these two regulatory proteins interact directly with one other. srpR and srpS were cloned into the GST gene fusion vector pGEX-4T-1 and the His6 tag gene fusion vector pQE31, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods. arpA, a regulatory gene that encodes the ArpABC efflux pump repressor in P. putida S12 (18), was cloned into pQE31 and included in the pulldown assay as a negative control for SrpS. In the GST pulldown assays, GST-SrpR was used as the bait protein, and His-SrpS was used as the prey protein. Three negative-control groups were tested simultaneously: GST-SrpR and His-ArpR, GST and His-SrpS, and PBS buffer and His-SrpS. The results of the pulldown assays were visualized using Western blotting, and Penta-His antibody was used to detect the His6 fusion proteins (Fig. 5). A strong band was present for the test group (lane 1), whereas no band (lane 2) or very faint bands (lanes 3 and 4) were present for the control groups, indicating that GST-SrpR and His-SrpS specifically interact with each other. This result supports our hypothesis that SrpR directly interacts with SrpS and acts as an antirepressor in the transcriptional regulatory system of the SrpABC efflux pump.

Fig. 5.

Results of the GST-pulldown assays visualized by Western blotting. The His6 fusion proteins were detected by Penta-His antibody and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Lane 1, GST-SrpR and His-SrpS (test group); lane 2, GST-SrpR and His-ArpR (negative control); lane 3, GST and His-SrpS (negative control); lane 4, PBS buffer and His-SrpS (negative control). The expected size of His-SrpS is 29 kDa, and the expected size of His-ArpR is 25 kDa. These assays were repeated three times; this figure, resulting from one of the three experiments, is representative of all three trials.

DISCUSSION

The SrpABC organic solvent efflux pump in P. putida S12 is a unique RND-type efflux system that has an unusual regulatory system consisting of two regulatory genes, srpS and srpR, located upstream of and transcribed divergently from the structural genes. Although the DNA sequence for the RND-type efflux system TtgGHI in P. putida DOT-T1E is highly similar to that encoding SrpABC, the pseudogene ttgW encodes a protein of only 134 amino acids compared to the 213-amino-acid SrpR protein. Therefore, while the truncated TtgW protein does not appear to be involved in regulation of the TtgGHI efflux pump (33), we show that SrpR is able to derepress SrpABC expression by inactivating SrpS activity in P. putida S12.

According to the transcription start site predictions based on alignment with the homologous ttgV and ttgG genes characterized previously by Rojas et al. (33), there is a 42-bp intergenic region between srpS and srpA, covering both the −10 and −35 regions of the promoters of these genes. We characterized srpA promoter activity in SrpS-deficient and SrpR-deficient backgrounds by constructing srpA-lacZ reporter gene fusion strains and performing β-galactosidase assays (Table 3). Expression from the srpA promoter increased 5.5-fold in the SrpS-deficient mutant in the absence of toluene but decreased almost 6-fold in the SrpR-deficient mutant, indicating that SrpS represses and SrpR derepresses srpABC expression. The srpS mutant (srpR polar mutation) showed complete derepression in the presence or absence of toluene. The data in Table 3 indicate that SrpR is responsible for approximately 83% of the srpABC derepression in the absence of toluene through its effect on SrpS and for 69% of the srpABC derepression in the presence of toluene. Furthermore, when SrpR is absent (SrpR− lacZ strain), toluene increases expression of the srpABC operon 10-fold (153 ± 7 versus 1,555 ± 95 Miller units), but no effect is observed when SrpS is absent (4,500 ± 223 versus 4,528 ± 102 Miller units), suggesting that toluene must interact directly with SrpS. However, it is interesting that full derepression of srpABC in the presence of toluene does not occur in the absence of SrpR (1,555 ± 95 versus 5,023 ± 363 Miller units), suggesting that either toluene potentiates SrpR to remove SrpS or else that toluene and SrpR act together to remove SrpS from the DNA. Given that SrpS is directly affected by toluene (Fig. 4), we predict that both mechanisms play an independent role in causing SrpS removal from an operator region upstream of srpABC: for toluene, activity is calculated as 5,023 ± 363 minus 892 ± 13 Miller units, or 4131 of 5,023 Miller units (or ∼82%); and for SrpR, activity is calculated as 892 ± 13 minus 153 ± 7 Miller units or 739 of 892 Miller units (or ∼83%). Together, toluene and SrpR act to dissociate SrpS from its operator upstream of srpABC.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays show that SrpS binds to the srpS-srpA intergenic region, thus repressing the transcription of srpA (Fig. 3 and 4). Although SrpR does not bind to this DNA region, it nevertheless inhibits the binding of SrpS to its operator (Fig. 4A), indicating that the derepressing effect of SrpR is achieved through the direct interaction of SrpR with SrpS. In Fig. 4, SrpS dissociates from target DNA at the same concentration of SrpR, regardless of whether toluene is present, suggesting that there is a threshold level of SrpR required to complex SrpS. However, in contrast to the in vivo lacZ promoter fusion data that suggest that SrpR is responsible for 69% of the SrpS derepression observed in the presence of toluene, a large proportion of the SrpS derepression in vitro appears to be due to the direct activity of toluene on SrpS (compare the 50-pmol MBP-SrpS and 50-pmol MBP-SrpR bands in Fig. 4A with the 50-pmol MBP-SrpS and 50-pmol MBP-SrpR plus toluene bands in Fig. 4B). The much greater SrpS dissociation shown in Fig. 4B can be at least partially explained by the fact that the comparison being made is between the effects of toluene directly on an in vitro system versus the indirect penetration of toluene into a live cell. It is reasonable to assume that the S12 cells were able to reduce the internal concentration of toluene to a level that not only permitted cell survival but also allowed SrpR to play a greater role in coregulating SrpS relative to the amount of toluene added. With higher cytoplasmic concentrations of toluene (e.g., as viable cells are nearing maximum toluene tolerance), it is possible that high levels of cytoplasmic toluene would lead to increased toluene inactivation of SrpS.

To further investigate the direct interaction of SrpR and SrpS, we conducted GST pulldown assays to identify protein-protein interactions between these two regulators. The bait protein GST-SrpR specifically binds to the prey protein His-SrpS but not to the negative control His-ArpR (the repressor protein for the P. putida S12 paralogous ArpABC efflux pump) (Fig. 5). This in vitro evidence further supports the contention that SrpR directly binds to SrpS and acts as an antirepressor in the transcriptional regulation of the SrpABC efflux pump. A model of the proposed interactions between SrpS and SrpR in regulating srpABC expression in both the presence and absence of toluene (organic solvent) is shown in Fig. 6.

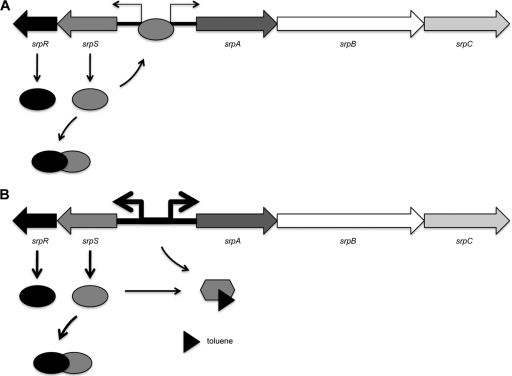

Fig. 6.

Proposed mechanism of transcriptional regulation of the srpABC operon in P. putida S12. (A) In the absence of toluene, SrpR (antirepressor) binding to SrpS (repressor) reduces the ability of SrpS to bind the operator site, permitting low-level expression from the srpS and srpA promoters. (B) In the presence of toluene, toluene binds SrpS, limiting its ability to bind the operator site. This derepression (in addition to the derepression caused by SrpR) strongly increases the transcription level from the srpS and srpA promoters. The opposing black arrows represent the promoters of srpS and srpA, with the thickness of the arrows indicating the level of transcription. The black triangle represents toluene.

Several mechanisms for antirepression have been previously described. Many mobile genetic elements have regulatory systems similar to an integrative and conjugative transposon named ICEBs1 found in the Bacillus subtilis genome (4). The SOS response and cell-cell signaling activate the conjugative transfer of ICEBs1 following inactivation of the ImmR repressor. Although the ImmR protein sequence is similar to that of many characterized phage repressors, its inactivation is not through RecA-dependent coproteolysis but, rather, results from direct proteolysis by the ICEBs1-encoded antirepressor ImmA. This antirepressor mechanism of action appears to be quite common, and ImmA homologs are widely conserved in many mobile genetic elements. A second functional class of antirepressors, especially those encoded within phage genomes, exhibits inhibitory activity through direct interaction and binding to their cognate repressors. For example, satellite phage RS1 produces antirepressor RstC that forms complexes with the RstR repressor of the phage CTX (6). Similarly, antirepressors Tum, Coi, E, and Ant from phages 186, P1, P4, and P22, respectively, are all thought to complex with their respective repressors and inhibit the ability of these repressors to bind DNA (15, 26, 35, 38). Even though no sequence or structural similarity is apparent between any of these antirepressors and SrpR, it is the second functional category of antirepressors to which SrpR belongs. Interestingly, SrpR is also predicted to belong to the TetR family of transcriptional regulators. Other members of this family are transcriptional repressors with a high degree of amino acid similarity at the helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain (31). Although SrpR contains this signature HTH domain in its N terminus, the results from this study indicate that SrpR is functionally neither a DNA-binding protein nor a transcriptional repressor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.J.D. gratefully acknowledges funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

We thank T. Raivio, S. Jensen, and J. Foght for helpful suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aono R., Ito M., Inoue A., Horikoshi K. 1992. Isolation of novel toluene-tolerant strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 56:145–146 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ausubel F. M., et al. 1991. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bose B., Auchtung J. M., Lee C. A., Grossman A. D. 2008. A conserved anti-repressor controls horizontal gene transfer by proteolysis. Mol. Microbiol. 70:570–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cruden D. L., Wolfram J. H., Rogers R. D., Gibson D. T. 1992. Physiological properties of a Pseudomonas strain which grows with p-xylene in a two-phase (organic-aqueous) medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2723–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis B. M., Kimsey H. H., Kane A. V., Waldor M. K. 2002. A satellite phage-encoded antirepressor induces aggregation and cholera toxin gene transfer. EMBO J. 21:4290–4299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Bont J. A. M. 1998. Solvent-tolerant bacteria in biocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 16:493–499 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dennis J. J., Sokol P. A. 1995. Electrotransformation of Pseudomonas. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dennis J. J., Zylstra G. J. 1998. Plasposons: Modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of Gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2710–2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duque E., Segura A., Mosqueda G., Ramos J. L. 2001. Global and cognate regulators control the expression of the organic solvent efflux pumps TtgABC and TtgDEF of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1100–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guazzaroni M. E., Teran W., Zhang X., Gallegos M. T., Ramos J. L. 2004. TtgV bound to a complex operator site represses transcription of the promoter for the multidrug and solvent extrusion TtgGHI pump. J. Bacteriol. 186:2921–2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guazzaroni M. E., et al. 2005. The multidrug efflux regulator TtgV recognizes a wide range of structurally different effectors in solution and complexed with target DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 280:20887–20893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guazzaroni M. E., et al. 2007. The transcriptional repressor TtgV recognizes a complex operator as a tetramer and induces convex DNA bending. J. Mol. Biol. 369:927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hartmans S., van der Werf M. J., de Bont J. A. 1990. Bacterial degradation of styrene involving a novel flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent styrene monooxygenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1347–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heinzel T., Velleman M., Schuster H. 1992. C1 repressor of phage P1 is inactivated by noncovalent binding of P1 Coi protein. J. Biol. Chem. 267:4183–4188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heipieper H. J., de Bont J. A. M. 1994. Adaptation of Pseudomonas putida S12 to ethanol and toluene at the level of fatty acid composition of membranes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4440–4444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Junker F., Ramos J. L. 1999. Involvement of the cis/trans isomerase Cti in solvent resistance of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 181:5693–5700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kieboom J., de Bont J. A. 2001. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux system involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 multidrug resistance. Microbiology 147:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kieboom J., Dennis J. J., de Bont J. A., Zylstra G. J. 1998a. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 solvent tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 273:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kieboom J., Dennis J. J., Zylstra G. J., de Bont J. A. 1998b. Active efflux of organic solvents by Pseudomonas putida S12 is induced by solvents. J. Bacteriol. 180:6769–6772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobayashi H., Uematsu K., Hirayama H., Horikoshi K. 2000. Novel toluene elimination system in a toluene-tolerant microorganism. J. Bacteriol. 182:6451–6455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krell T., et al. 2007. Optimization of the palindromic order of the TtgR operator enhances binding cooperativity. J. Mol. Biol. 369:1188–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kumar A., Schweizer H. P. 2005. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: active efflux and reduced uptake. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 57:1486–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li X. Z., Zhang L., Poole K. 1998. Role of the multidrug efflux systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in organic solvent tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 180:2987–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li X. Z., Nikaido H. 2004. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria. Drugs 64:159–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu T., Renberg S. K., Haggard-Ljungquist E. 1998. The E protein of satellite phage P4 acts as an anti-repressor by binding to the C protein of helper phage P2. Mol. Microbiol. 30:1041–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McMurry L., Petrucci R. E., Jr., Levy S. B. 1980. Active efflux of tetracycline encoded by four genetically different tetracycline resistance determinants in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 77:3974–3977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mosqueda G., Ramos-González M. I., Ramos J. L. 1999. Toluene metabolism by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1 strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene 232:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ramos J. L., et al. 1997. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3887–3890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ramos J. L., et al. 2002. Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:743–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramos J. L., et al. 2005. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:326–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rojas A., et al. 2001. Three efflux pumps are required to provide efficient tolerance to toluene in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 183:3967–3973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rojas A., et al. 2003. In vivo and in vitro evidence that TtgV is the specific regulator of the TtgGHI multidrug and solvent efflux pump of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 185:4755–4763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shearwin K. E., Brumby A. M., Egan J. B. 1998. The Tum protein of coliphage 186 is an antirepressor. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5708–5715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Slauch J. M., Silhavy T. J. 1991. cis-Acting ompF mutations that result in OmpR-dependent constitutive expression. J. Bacteriol. 173:4039–4048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun X., Dennis J. J. 2009. A novel insertion sequence derepresses efflux pump expression and preadapts Pseudomonas putida S12 for extreme solvent stress. J. Bacteriol. 191:6773–6777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Susskind M. M., Youderian P. 1982. Transcription in vitro of the bacteriophage P22 antirepressor gene. J. Mol. Biol. 154:427–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Teran W., et al. 2003. Antibiotic-dependent induction of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E TtgABC efflux pump is mediated by the drug binding repressor TtgR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3067–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weber F. J., de Bont J. A. M. 1996. Adaptation mechanisms of microorganisms to the toxic effects of organic solvents on membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1286:225–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wery J., Hidayat B., Kieboom J., de Bont J. A. 2001. An insertion sequence prepares Pseudomonas putida S12 for severe solvent stress. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5700–5706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]