Abstract

Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium difficile are closely related anaerobic Gram-positive, spore-forming human pathogens. C. sordellii and C. difficile form spores that are believed to be the infectious form of these bacteria. These spores return to toxin-producing vegetative cells upon binding to small molecule germinants. The endogenous compounds that regulate clostridial spore germination are not fully understood. While C. sordellii spores require three structurally distinct amino acids to germinate, the occurrence of postpregnancy C. sordellii infections suggests that steroidal sex hormones might regulate its capacity to germinate. On the other hand, C. difficile spores require taurocholate (a bile salt) and glycine (an amino acid) to germinate. Bile salts and steroid hormones are biosynthesized from cholesterol, suggesting that the common sterane structure can affect the germination of both C. sordellii and C. difficile spores. Therefore, we tested the effect of sterane compounds on C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germination. Our results show that both steroid hormones and bile salts are able to increase C. sordellii spore germination rates. In contrast, a subset of steroid hormones acted as competitive inhibitors of C. difficile spore germination. Thus, even though C. sordellii and C. difficile are phylogenetically related, the two species' spores respond differently to steroidal compounds.

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium difficile are Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming, obligate anaerobic bacteria that are phylogenetically closely related (12). C. sordellii can be identified in the vaginal microbiota of <1% of women and the gastrointestinal tracts of <10% of adults (1, 45). C. difficile spores are also carried asymptomatically in the gastrointestinal tracts of 3 to 15% of most healthy human adult populations (10, 41).

Many strains of C. sordellii are nonpathogenic, but virulent strains can produce lethal infections in several animals (26). Hemorrhagic enteritis occurs in sheep, cattle, and foals after ingestion of C. sordellii spores (2, 9, 23, 36). Penetrating trauma, injection of black tar heroin, and gynecological procedures are potential risk factors for infection in humans (1, 27, 31, 50). Septic shock due to C. sordellii bacteremia results in 70% to 100% mortality rates (1, 4). C. sordellii infections of the female genital tract develop primarily after childbirth and less commonly following spontaneous or medical abortion (1, 11, 19, 50). This suggests that female steroidal sex hormones might play a role in the pathogenesis of infection.

Resident gut microbes seem to be sufficient to keep C. difficile in the inactive, spore form (8, 42). Treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics disrupts the intestinal microbiota, which is believed to allow C. difficile spores to establish infection (10). C. difficile infection (CDI) is responsible for ∼25% of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (18).

The emergence of new C. difficile hypervirulent strains has further complicated treatment of CDI. C. difficile strain NAP1/BI/027 shows both antibiotic resistance and increased levels of toxins (29, 57). This strain is associated with more-severe forms of CDI that often progress to toxic megacolon, resulting in mortality rates of 1% to 2.5% (29, 30).

Glucocorticoids are used to treat diarrheas associated with inflammatory bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis (15). These diseases represent a potential risk for CDI. A recent paper has shown that glucocorticoid immunosuppressant therapy increases the risk of mortality in patients with CDI (15). This suggests that steroid hormones can also affect CDI establishment and/or virulence.

C. sordellii and C. difficile, like other Clostridium and Bacillus species, differentiate into metabolically inactive spores that can survive harsh environmental conditions (16, 37). The spores can revert to toxin-producing bacteria (a process called germination), typically in nutrient rich-environments (34, 48). Detection of nutrients is normally required for germination and is typically accomplished by the Ger receptor family of proteins (43). Although Ger receptors are encoded by most Bacillus and Clostridium species, there is no information regarding the presence of Ger receptors in C. sordellii. However, we have shown that C. sordellii spores specifically recognize l-alanine, l-phenylalanine, l-arginine, and bicarbonate as germinants (38), suggesting the involvement of germination receptors. Interestingly, C. difficile does not encode Ger receptors but must be able to detect metabolites for spores to enter germination and return to vegetative life (47). Indeed, recent work has shown that C. difficile spores recognize taurocholate (a bile salt) and glycine (an amino acid) as germinants (53). Furthermore, chenodeoxycholate was shown to be a naturally occurring inhibitor of C. difficile spore germination (54). Work from our laboratory has shown cooperative binding of both taurocholate and glycine, suggesting the presence of unidentified receptors for both germinants (39).

Bile salts and steroid hormones are mammalian metabolites biosynthesized from cholesterol (32, 44). Bile salts are produced in the liver and function to solubilize lipids in the gastrointestinal tract (44). Steroid hormones, on the other hand, are produced by different tissues and affect numerous cellular processes (32). Synthetic steroidal hormones are used in reproductive medicine to control endometrial irregularities and are also used to treat different types of cancer (6, 13, 25, 56).

Interestingly, although bile salts and steroid hormones are not part of the normal metabolome of prokaryotes, a number of bacterial species produce enzymes that modify steroidal molecules (22, 52). Specifically, bacterial transformation of steroidal hormones has been reported to occur in a wide range of bacteria, including Clostridium (7, 28). Normal gut bacteria also metabolize bile salts (40, 49), a process that has been implicated in the control of C. difficile infections (21). Furthermore, changes in progesterone and glucocorticoid levels have been implicated in modulating infectious disease susceptibility and progression (59). Progesterone analogs with antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria have also been developed (33).

Notably, progesterone, mifepristone, bile salts, and corticosteroids (which have also been associated with CDI [15]) share a four-ring sterane skeleton. Thus, we investigated the effect of select steroidal hormones and bile salts on C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germination. Our results show that sterane analogs increase C. sordellii spore germination rates. In contrast, a subset of steroid hormones acted as competitive inhibitors of C. difficile spore germination. Our results suggest that steroidal hormones may play an important role in the pathogenesis of toxigenic clostridial infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and chemicals.

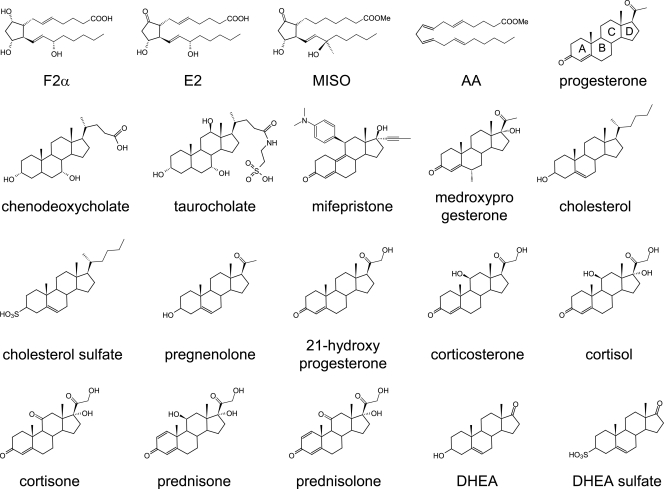

HistoDenz, bile salts, prostaglandin, and steroid hormone analogs (Fig. 1) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO).

Fig. 1.

Compounds tested as agonists and antagonists of C. difficile spore germination. F2α refers to prostaglandin F2α, E2 refers to prostaglandin E2, MISO refers to misoprostol, AA refers to arachidonic acid, and DHEA refers to dehydroepiandrosterone.

Bacterial strains and spore preparations.

C. sordellii ATCC 9714 and C. difficile strain 630 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). C. sordellii was plated in brain heart infusion (BHI) agar. C. difficile was plated in BHI agar supplemented with 1% yeast extract, 0.1% l-cysteine, and 0.05% sodium taurocholate. Individual C. sordellii and C. difficile colonies were grown in BHI broth and replated in 15 to 20 plates to obtain bacterial lawns. Plates were incubated for 5 days (for C. sordellii) or 7 days (for C. difficile) at 37°C in an anaerobic environment (5% CO2, 10% H2, 85% N2). Bacterial lawns were collected by flooding the plates with ice-cold deionized water. Spores were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh deionized water. After two washing steps, spores were separated from vegetative and partially sporulated cells by centrifugation through a 20% to 50% HistoDenz gradient. Spore pellets were washed five times with water, resuspended with 0.1% sodium thioglycolate, and stored at 4°C for no more than 14 days. Spore preparations were more than 95% pure, as determined by microscopy observation of Schaeffer-Fulton-stained aliquots (35).

Enhancement and inhibition of C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germination.

Changes in light diffraction during spore germination (optical density at 580 nm [OD580]) were monitored using a Tecan Infinite M200 96-well plate reader set at 580 nm (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland). C. difficile and C. sordellii spores were heat activated at 65°C for 30 min. After heat activation, spores were resuspended in germination buffer specific for each bacterium at an OD580 of 1. C. difficile was germinated in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) supplemented with 0.5% NaHCO3. C. sordellii was germinated in a buffer solution made with 6.6 mM KH2PO4, 15 mM NaCl, 59.5 mM NaHCO3, and 35.2 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 7.0. Spore suspensions were monitored for auto-germination for 30 min, and germination experiments were carried out with spores that did not auto-germinate. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least two different spore preparations. All germination experiments were carried out with 96-well plates at a 200-μl final volume. Spore aliquots were individually treated with various concentrations of prostaglandin or steroidal hormone analogs (Fig. 1) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature while OD580 was monitored. C. difficile spores were then supplemented with 12 mM glycine (for activation experiments) or 6 mM taurocholate-12 mM glycine (for inhibition experiments). These concentrations of taurocholate and glycine are the lowest concentrations of each compound that give the maximal germination rate. Similarly, C. sordellii spores were germinated under suboptimal conditions with 5 mM l-alanine, 5 mM l-arginine, and 1 mM l-phenylalanine (for enhancement experiments) or under optimal conditions with 25 mM l-alanine, 10 mM l-arginine, and 5 mM l-phenylalanine (for inhibition assays). After addition of germinants, spore germination was monitored as the decrease in OD580 measured at 1-min intervals for 90 min. Relative OD580 values were obtained at different times by dividing each OD580 value by the initial OD580 value. All measurements showed standard deviations of less than 10%. Germination rates (v) were calculated as the slope of the linear portion immediately following the initial lag phase of the relative OD values over time. As expected, germination rates decreased in the presence of active germination inhibitors and increased in the presence of germination enhancers. Germination was confirmed for selected samples by microscopy observation of Schaeffer-Fulton-stained aliquots (35). For prostaglandin assays, germination rates were set to 100% for C. difficile spores germinated with 6 mM taurocholate and 12 mM glycine and for C. sordellii spores germinated with 5 mM l-alanine, 5 mM l-arginine, and 1 mM l-phenylalanine. Relative germination rates were calculated as fractions of the values for these conditions. For sterane compounds, the germination rates obtained were plotted against the logarithm of compound concentrations. The resulting sigmoidal curves were fitted using the four-parameter logistic function of the SigmaPlot version 9 software program to calculate 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) (for enhancers of spore germination) or 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) (for inhibitors of spore germination). The EC50 is the concentration of a germination enhancer required to increase the germination rate to 50% of the maximal value. The IC50 is the concentration of a germination inhibitor required to reduce the germination rate to 50% of the maximal value.

Kinetic analysis of progesterone-induced inhibition of C. difficile spore germination.

After heat activation, C. difficile spore aliquots were resuspended in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) supplemented with 0.5% NaHCO3 to an OD580 of 1. Spore aliquots were then treated with saturating concentrations (6 mM) of glycine and individually supplemented with various concentrations (400, 300, 200, 100, 50, and 0 μM) of progesterone. Spore suspensions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature while OD580 was monitored. Taurocholate was then added to give a 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12 mM final concentration. Germination rates (v) were determined as described above. The resulting data were plotted as double reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/taurocholate concentration2 at different progesterone concentrations and as Dixon plots of 1/v versus progesterone concentration at different taurocholate concentrations. The various slopes from the inhibition double reciprocal plots were further plotted against progesterone concentrations to determine the apparent inhibition constant (Ki).

RESULTS

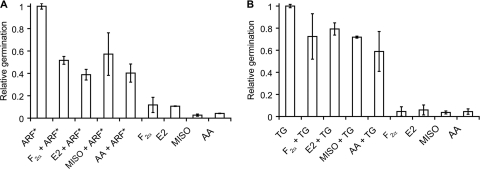

In this work, we tested the effect of prostaglandin and steroid hormone analogs on C. sordellii spore germination. To determine species specificity, prostaglandin and steroid hormone analogs were also tested in C. difficile spore germination assays. Prostaglandin analogs only weakly inhibited C. sordellii spore germination at supraphysiological concentrations of 0.5 mM (Fig. 2A). Similarly, prostaglandin analogs did not significantly affect C. difficile spore germination (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of prostaglandin analogs on spore germination. (A) C. sordellii ATCC 9714 spores were germinated with 25 mM l-alanine, 10 mM l-arginine, 5 mM l-phenylalanine, and 50 mM NaHCO3 (ARF*) or ARF* supplemented with 0.5 mM F2α, E2, MISO, or AA. C. sordellii spores were also individually treated with F2α, E2, MISO, or AA alone. “Relative germination” refers to relative germination rates of prostaglandin treated C. sordellii spores as a fraction of the relative germination rate of untreated C. sordellii spores. (B) C. difficile 630 spores were germinated with 12 mM taurocholate and 6 mM glycine (TG) or TG supplemented with 0.5 mM F2α, E2, MISO, or AA. C. difficile 630 spores were also individually treated with F2α, E2, MISO, or AA alone. Relative germination refers to relative germination rates of prostaglandin-treated C. difficile spores as a fraction of the relative germination rate of untreated C. difficile spores.

In contrast to the weak effect of prostaglandins, C. sordellii and C. difficile spores show strikingly differential responses to bile salts and steroid hormones. Whereas C. sordellii spores showed germination enhancement in the presence of steroid hormones, C. difficile spores showed germination inhibition. Furthermore, both germination enhancement and inhibition were dependent on the concentration of the steroid hormone analog tested. These results were confirmed by Schaeffer-Fulton staining of aliquots taken at different time points after germinant addition. Samples treated with germination enhancers showed fast emergence of red-stained germinated cells. Meanwhile, samples treated with germination inhibitors showed only green-stained spores (data not shown).

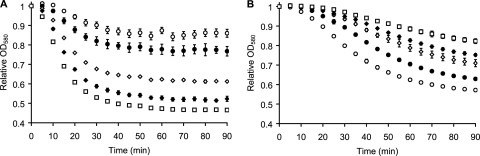

Progesterone is a naturally occurring steroid that is produced in large quantities during pregnancy (58). Progesterone titration increases C. sordellii spore germination rates at suboptimal germinant concentrations (Fig. 3A). Indeed, progesterone can increase C. sordellii spore germination to its maximal rate. The EC50 for progesterone germination enhancement was 27.7 μM (Table 1). Even though progesterone can increase C. sordellii spore germination, progesterone alone or combined with individual or binary combinations of l-alanine, l-arginine, or l-phenylalanine did not induce C. sordellii spore germination (data not shown). At the concentrations tested, progesterone supplementation did not affect vegetative growth of C. sordellii or C. difficile bacilli.

Fig. 3.

Effect of progesterone on C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germination. (A) Enhancement of C. sordellii spore germination. C. sordellii spores were treated with 5 mM l-alanine, 5 mM l-arginine, 1 mM l-phenylalanine, and 50 mM NaHCO3, and progesterone was added at 0 μM (○), 1 μM (●), 5 μM (♢), 10 μM (♦), and 50 μM (□) final concentrations. C. sordellii spores were also treated with 25 mM l-alanine, 10 mM l-arginine, 5 mM l-phenylalanine, and 50 mM NaHCO3 (■) to obtain the maximum germination rate in the absence of progesterone. For clarity, data are shown at 5-min intervals. (B) Inhibition of C. difficile spore germination. C. difficile spores were incubated with 0 mM (○), 0.05 mM (●), 0.1 mM (♢), 0.2 mM (♦), and 0.4 mM (□) concentrations of progesterone and supplemented with taurocholate (6 mM) and glycine (12 mM). For clarity, data are shown at 5-min intervals.

Table 1.

Effect of progesterone analogs on C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germination

| Steroid hormone | EC50 (μM) for C. sordellii spore germination enhancementa,b,c | IC50 (μM) for C. difficile spore germination inhibitionc,d |

|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 27.7 (7.4) | 80.5 (19.5) |

| Chenodeoxycholate | 32.2 (7.4) | 235.3 (17.2) |

| Taurocholate | 16.0 (4.3) | –e |

| Mifepristone | 6.3 (1.0) | 18.2 (2.1) |

| Medroxyprogesterone | 22.1 (1.7) | NA |

| Cholesterol | NA | NA |

| Cholesterol sulfate | NA | NA |

| Pregnenolone | 9.3 (5.1) | NA |

| 21-Hydroxyprogesterone | 20.6 (2.7) | 217.5 (19.4) |

| Corticosterone | 12.3 (2.8) | 451.4 (55.3) |

| Cortisol | 235.2 (39.8) | NA |

| Cortisone | 45.2 (1.7) | NA |

| Prednisone | 241.6 (28.6) | 305.6 (72.5) |

| Prednisolone | 17.9 (0.8) | NA |

| DHEA | NA | 168.3 (15.8) |

| DHEA sulfate | NA | 456.8 (60.4) |

All reactions were carried out in the presence of suboptimal concentrations of ARF* (5 mM l-alanine, 5 mM l-arginine, 1 mM l-phenylalanine, and 50 mM NaHCO3). This combination of germinant concentrations yielded a germination rate of 11.6% (3.4%) compared with the rate obtained with optimal concentrations of ARF* (25 mM l-alanine, 10 mM l-arginine, 5 mM l-phenylalanine, and 50 mM NaHCO3).

The EC50 for l-arginine was 4.0 (0.22) mM, the EC50 for l-alanine was 12.8 (4.7) mM, the EC50 for l-phenylalanine was 0.005 (0.001) mM, and the EC50 for NaHCO3 was 39.7 (13.1) mM at saturating concentrations of other germinants.

Values in parentheses are standard deviations. “NA” indicates compounds that do not enhance or inhibit spore germination up to 0.5 mM final concentrations.

All reactions were carried out at saturating concentrations of taurocholate (6 mM) and glycine (12 mM).

The EC50 for taurocholate was 15.9 (3.3) mM, and the EC50 for glycine was 11.4 (2.4) mM at the saturating concentration of the second germinant.

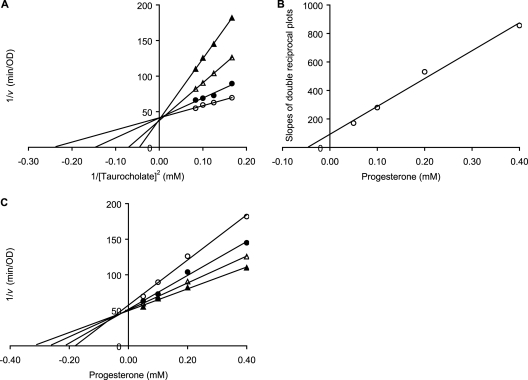

In contrast to the germination enhancement seen for C. sordellii spores, progesterone inhibited C. difficile spore germination (Fig. 3B). Progesterone titration yielded an IC50 of 80.5 μM for C. difficile spore germination inhibition (Table 1). Double reciprocal plot (Fig. 4A) and Dixon plot (Fig. 4C) analyses of progesterone-induced inhibition of C. difficile spore germination showed that progesterone is a competitive inhibitor of taurocholate-mediated germination. The Ki for progesterone was calculated to be 44.7 μM (Fig. 4B). Similarly, pregnenolone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) also behaved as competitive inhibitors of C. difficile spore germination (data not shown). We recently reported that C. difficile spores bind chenodeoxycholate cooperatively (39). Interestingly, inhibition analysis shows no cooperativity for binding of progesterone to C. difficile spores (Fig. 4C). Similar noncooperative binding behavior was observed for pregnenolone and DHEA (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Kinetic analysis of progesterone-induced inhibition of C. difficile spore germination. Germination rates were calculated from the linear segment of optical density changes over time. (A) Lineweaver-Burk plots of C. difficile spore germination at various concentrations of taurocholate (6, 8, 10, and 12 mM) and 0.05 (○), 0.1 (●), 0.2 (▵), and 0.4 (▴) mM progesterone concentrations. (B) A replot of slopes from Lineweaver-Burk plots versus progesterone concentrations was fitted to a straight line and yielded a Ki of 0.045 mM for progesterone binding. (C) Dixon plot of C. difficile spore germination at various concentrations of progesterone (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 mM) and 6 (○), 8 (●), 10 (▵), and 12 (▴) mM taurocholate.

C. difficile spores use taurocholate and glycine as cogerminants. Titration of C. difficile spores with taurocholate in the presence of saturating glycine concentration yielded an EC50 of 15.9 mM for taurocholate. Titration of C. difficile spores with chenodeoxycholate (a known germination inhibitor) in the presence of saturating taurocholate and glycine concentrations yielded an IC50 of 235 μM for chenodeoxycholate. In contrast to the differential effect that bile salts have on C. difficile spore germination, both chenodeoxycholate and taurocholate enhanced C. sordellii spore germination, with EC50s of 32.2 μM and 16.0 μM, respectively (Table 1).

Mifepristone is a synthetic steroid that acts as a progesterone and glucocorticoid antagonist (25). Medroxyprogesterone, on the other hand, is a synthetic progestin that functions as a progesterone agonist (6). Similar to progesterone, mifepristone also enhanced C. sordellii spore germination, with an EC50 of 6.3 μM, and inhibited C. difficile spore germination, with an IC50 of 18.2 μM (Table 1). In contrast, medroxyprogesterone is also a strong enhancer of C. sordellii spore germination (EC50 of 22.1 μM) but does not affect C. difficile spore germination (Table 1).

Cholesterol is the precursor of both steroid hormones and bile salts (32, 44). Cholesterol sulfate is a natural inhibitor of steroidogenesis (60). Despite having the same sterane backbone as steroid hormones and bile salts, neither cholesterol nor cholesterol sulfate affected C. sordellii or C. difficile spore germination.

Pregnenolone is biosynthesized directly from cholesterol and is the initial prohormone of steroidogenesis (32). Pregnenolone differs from progesterone in the position of the double bond and the change of the 3-keto group to a 3-hydoxyl group. Similar to medroxyprogesterone, pregnenolone enhanced C. sordellii spore germination, with an EC50 of 9.3 μM (a potency similar to that of mifepristone), but did not significantly affect C. difficile spore germination (Table 1).

21-Hydroxyprogesterone is biosynthesized from progesterone and is further converted to corticosterone (46). 21-Hydroxyprogesterone differs from progesterone by a hydroxyl group at position 21, while corticosterone has a second hydroxyl at position 11. In C. sordellii spores, there is a slight stepwise enhancement of germination with successive addition of hydroxyls, with EC50s of 27.7 μM, 20.6 μM, and 12.3 μM for progesterone, 21-hydroprogesterone, and corticosterone, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, the addition of the hydroxyl group reduces inhibition activity against C. difficile spores, as shown by IC50s of 80.5 μM, 217.5 μM, and 451.4 μM for progesterone, 21-hydroprogesterone, and corticosterone, respectively (Table 1).

Cortisol, an adrenal hormone, is biosynthesized from corticosterone by addition of a hydroxyl group at position 17 (46). Cortisol can in turn be converted to cortisone by oxidation of the 11-hydroxyl group to a ketone. In C. sordellii spores, there is a large loss of germination enhancement from corticosterone to cortisol, as seen by the increasing EC50s of 12.3 μM to 235.2 μM, respectively (Table 1). Change of cortisol to cortisone, on the other hand, retrieves much of the germination enhancement ability, as shown by an EC50 of 45.2 μM. In C. difficile spore germination, the addition of the hydroxyl group results in negligible germination inhibition activity by both cortisol and cortisone.

Prednisone is an artificial corticosteroid that is converted into prednisolone in the liver (20). Prednisone and prednisolone are structurally similar to cortisol and cortisone, differing in an extra double bond in the A ring of the sterane skeleton. Prednisone and prednisolone behave similarly to their natural analogs toward both C. sordellii and C. difficile spores.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is biosynthesized from pregnenolone in two steps (32). DHEA has no effect on C. sordellii spore germination. In contrast, DHEA inhibits C. difficile spore germination, with an IC50 of 168.3 μM. In contrast, the more polar dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA sulfate) does not affect C. sordellii spore germination and is a weak inhibitor of C. difficile spore germination, with an IC50 of 456.8 μM.

DISCUSSION

Recently, it was shown that pharmacological doses of misoprostol, a prostaglandin analog, could reduce immune defenses against C. sordellii in rodents (5). Misoprostol is given in combination with mifepristone, a hormone steroid antagonist. In this work, we showed that whereas prostaglandin analogs have little effect on clostridial spore germination, steroid hormones can affect both C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germination.

The selected steroidal compounds tested allowed for determination of the epitope necessary for stimulation or inhibition of spore germination. Structure-activity relationship analysis of germination enhancers yielded information on functional groups necessary for both binding to clostridial spores and activation of the germination pathway. On the other hand, inhibition assays yielded information on functional groups required only for binding to clostridial spores. Finally, compounds that could neither activate nor inhibit spore germination yielded information on functional groups that interfered with spore binding.

At suboptimal germinant concentrations, C. sordellii spore germinations rates were enhanced by progesterone, chenodeoxycholate, taurocholate, mifepristone, medroxyprogesterone, pregnenolone, 21-hydroxyprogesterone, corticosterone, cortisol, cortisone, prednisone, and prednisolone. No inhibitor of C. sordellii spore germination was found among the compounds tested. In contrast, C. difficile spore germination was inhibited by progesterone, chenodeoxycholate, mifepristone, 21-hydroxyprogesterone, corticosterone, prednisone, DHEA, and DHEA sulfate. As expected, no activator of C. difficile spore germination was found among the compounds tested. To our knowledge, this is the first report of compounds that can act both as germination enhancers and as inhibitors on related wild-type bacterial spores.

Both EC50 and IC50 are relative values that strongly depend on the concentrations of germinants. Nevertheless, EC50s and IC50s obtained under similar conditions are useful for comparing the effects of related compounds on spore germination. To compare germination enhancements, EC50s for steroid analogs were calculated at suboptimal concentrations of germinants. Similarly, to compare germination inhibitions, IC50s for steroid hormone analogs were calculated at saturating concentrations of germinants. Although C. sordellii and C. difficile are closely related species, there was no correlation in the activity of sterane compounds toward their respective spores. Some compounds were strong enhancers of C. sordellii spore germination and strong inhibitors of C. difficile spore germination (e.g., mifepristone). Other compounds activated C. sordellii spore germination but had no effect on C. difficile spore germination (e.g., cortisone). Yet, other compounds did not affect C. sordellii spore germination but inhibited C. difficile spore germination (e.g., DHEA). Furthermore, it seems that C. sordellii spores are able to recognize taurocholate 1,000-fold better than C. difficile spores. This is consistent with the presence of related receptors in both species that have evolved to recognize different functional groups in the sterane ring structure.

Sterane compounds are not germinants of C. sordellii spores per se but act as germination enhancers. Remarkably, the sterane concentrations required for the enhancement effect are 2 to 3 orders of magnitude lower than those of the natural germinants l-alanine, l-arginine, and bicarbonate (38). Thus, steranes are probably bound tightly and are able to prime C. sordellii spores for the germination process.

Molecular interactions between spore germination machinery and sterane compounds require specific contacts. For C. sordellii spores, it seems that either hydroxyl or ketone groups are required in both the A ring and the side chain from the D ring. Extra hydroxyl groups in the side chain do not affect interaction with the C. sordellii spore. However, addition of hydroxyl group at position 11 in the C ring reduces binding of the compound to spores. This interference is reduced when the hydroxyl group is changed to a ketone. Finally, addition of either hydroxyl or ketone to position 17 of the D ring has a large detrimental effect on sterane activity.

C. difficile spores seem to favor steroid hormone inhibitors that have ketone groups and disfavor compounds with hydroxyl groups. Position 17 of the D ring seems to be especially sensitive to deactivation by the presence of a hydroxyl group. This pattern of progesterone analog recognition contrasts with the recognition of bile salts by C. difficile spores, where both germinants and inhibitors require hydroxyl groups at least at positions 3, 7, and/or 12 (24).

In our hands, taurocholate and chenodeoxycholate show cooperative binding to C. difficile spores. Thus, Km and Ki values for these compounds are complex constants that contain terms for inhibitor concentrations and for factors of interaction between cooperating binding sites. In a recent article, the Ki for chenodeoxycholate was independently calculated (55). However, this Ki value was obtained for a single chenodeoxycholate concentration and thus cannot be compared directly to the results obtained in our work. Progesterone, just like chenodeoxycholate, was shown to be a competitive inhibitor of taurocholate-mediated germination (39, 55), suggesting that taurocholate, chenodeoxycholate, and progesterone bind to the same site in C. difficile spores. However, in contrast to taurocholate and chenodeoxycholate, C. difficile spores show noncooperative binding for progesterone, pregnenolone, or DHEA. This difference in binding mechanism makes it impractical to compare Ki values between chenodeoxycholate and progesterone analogs. In contrast, IC50s obtained under similar saturating germinant concentrations can be used to contrast inhibitor strength. Under these conditions, progesterone was shown to be 3-fold more active than chenodeoxycholate in C. difficile spore germination inhibition assays.

Even though mifepristone is an antagonist of progesterone binding in humans (25), it exhibited behavior similar to that of progesterone toward C. sordellii and C. difficile spores. Furthermore, mifepristone seems to be a more potent enhancer of C. sordellii spore germination and a better inhibitor of C. difficile spore germination than naturally occurring progesterone or chenodeoxycholate (39). The relevance of these findings to the clinical use of mifepristone in humans remains to be determined.

Conclusions.

Our results show that both C. sordellii and C. difficile spore germinations are differentially affected by steroid hormone analogs. As expected, changing the functional groups of the sterane moiety affected germination efficiency. Structure-activity relationship analysis points to a number of specific interactions between C. sordellii and C. difficile germination machineries and steroidal hormones.

Inhibition analysis suggests that steroid hormones bind to the same receptors that recognize taurocholate in C. difficile spores. However, it seems that bile salts and steroid hormone recognition by C. difficile spores follow distinct rules, even though both groups of sterane compounds compete with taurocholate for spore binding. Whether these differences are due to binding to different taurocholate receptors or differential recognition by the same receptor has not been elucidated.

Since C. sordellii spores are also activated by taurocholate, we expect that C. sordellii will contain a homolog taurocholate-type receptor. Obviously, the putative receptors in both species recognize sterane compounds differently. This is characteristic of orthologic binding sites that have evolved to respond differently to their cognate ligands. Unfortunately, even though putative receptors must be present in both C. sordellii and C. difficile spores to recognize sterane compounds, the identity of these receptors has not been determined. This precludes a more detailed mechanistic analysis of the effect of steroidal hormones on clostridial spore germination.

We have recently speculated that the presence of increased amino acid levels during pregnancy together with high vaginal pH may provide the signaling for C. sordellii spore germination and infection establishment (38). The concentration of progesterone in placenta can be as high as 6 μM (17). Therapeutic administration of mifepristone leads to serum concentrations of ≤10 μM (51). Intrauterine concentrations of mifepristone have not been determined but are expected to be negligible. Thus, in postdelivery females, progesterone would be the major sterane compound in the intrauterine environment where C. sordellii establishes infection. Since progesterone can enhance spore germination in vivo, it could serve as a complicating factor in the increase of postdelivery or postabortion C. sordellii infections.

The relation between steroid hormones and their effect on CDI establishment is not clear. Steroid hormones administered orally are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream and are not present at significant levels in the intestinal tract (14). Hence, C. difficile spores have little opportunity to encounter steroid hormones before germination. On the other hand, a number of corticosteroids with enhanced topical activity and low systemic activity have recently been developed for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (3). Indeed, a recent study revealed a correlation between oral glucocorticoid use and increased CDI risk (15). Whether the glucocorticoid-CDI relation is due to the effect of these hormones on C. difficile spore germination is not known.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aldape M. J., Bryant A. E., Stevens D. L. 2006. Clostridium sordellii infection: epidemiology, clinical findings, and current perspectives on diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:1436–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al-Mashat R. R., Taylor D. J. 1983. Production of diarrhoea and enteric lesions in calves by the oral inoculation of pure cultures of Clostridium sordellii. Vet. Rec. 112:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Angelucci E., Malesci A., Danese S. 2008. Budesonide: teaching an old dog new tricks for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 15:2527–2535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aronoff D. M., Ballard J. D. 2009. Clostridium sordellii toxic shock syndrome. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:725–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aronoff D. M., et al. 2008. Misoprostol impairs female reproductive tract innate immunity against Clostridium sordellii. J. Immunol. 180:8222–8230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bakry S., et al. 2008. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate: an update. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 278:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bokkenheuser V. D., Suzuki J. B., Polovsky S. B., Winter J., Kelly W. G. 1975. Metabolism of deoxycorticosterone by human fecal flora. Appl. Microbiol. 30:82–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borriello P. S. 1990. The influence of the normal flora on Clostridium difficile colonization of the gut. Ann. Med. 22:61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clark S. 2003. Sudden death in periparturient sheep associated with Clostridium sordellii. Vet. Rec. 153:340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cloud J., Kelly C. P. 2007. Update on Clostridium difficile associated disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 23:4–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen A. L., et al. 2007. Toxic shock associated with Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens after medical and spontaneous abortion. Obstet. Gynecol. 110:1027–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collins M. D., et al. 1994. The phylogeny of the genus Clostridium: proposal of five new genera and eleven new species combinations. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:812–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cullins V. E. 1996. Noncontraceptive benefits and therapeutic uses of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. J. Reprod. Med. 41:428–433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Czock D., Keller F., Rasche F. M., Häussler U. 2005. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of systemically administered glucocorticoids. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 44:61–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Das R., Fererstadt P., Brandt L. J. 2010. Glucocorticoids are associated with increased risk of short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105:2040–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Errington J. 2003. Regulation of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feinshtein V., et al. 2010. Progesterone levels in cesarean and normal delivered term placentas. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 281:387–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fekety R., Shah A. B. 1993. Diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. JAMA 269:71–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fischer M., et al. 2005. Fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:2352–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frey B. M., Frey F. J. 1990. Clinical pharmacokinetics of prednisone and prednisolone. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 19:126–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giel J. L., Sorg J. A., Sonenshein A. L., Zhu J. 2010. Metabolism of bile salts in mice influences spore germination Clostridium difficile. PLoS One 5:e8740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayakawa S. 1973. Microbiological transformation of bile acids. Adv. Lipid. Res. 11:143–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hibbs C. M., Johnson D. R., Reynolds K., Harrington R. 1977. Clostridium sordellii isolated from foals. Vet. Med. Small Anim. Clin. 72:256–258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Howerton A., Ramirez N., Abel-Santos E. 2011. Mapping interactions between germinants and Clostridium difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 193:274–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Im A., Appleman L. J. 2010. Mifepristone: pharmacology and clinical impact in reproductive medicine, endocrinology and oncology. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 11:481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kachman M. T., Hurley M. C., Thiele T., Srinivas G., Aronoff D. M. 2010. Comparative analysis of the extracellular proteomes of two Clostridium sordellii strains exhibiting contrasting virulence. Anaerobe 16:454–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kimura A. C., et al. 2004. Outbreak of necrotizing fasciitis due to Clostridium sordellii among black-tar heroin users. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:e87–e91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krafft A. E., Winter J., Bokkenheuser V. D., Hylemon P. B. 1987. Cofactor requirements of steroid-17-20-desmolase and 20-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activities by Clostridium scindens. J. Steroid Biochem. 28:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loo V. G., et al. 2005. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:2442–2449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McDonald L. C., et al. 2005. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:2433–2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miech R. P. 2005. Pathophysiology of mifepristone-induced septic shock due to Clostridium sordellii. Ann. Pharmacother. 39:1483–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller W. L. 2002. Androgen biosynthesis from cholesterol to DHEA. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 198:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mohareb R., Hana H. 2008. Synthesis of progesterone heterocyclic derivatives of potential antimicrobial activity. Acta Pharm. 58:29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moir A., Corfe B. M., Behravan J. 2002. Spore germination. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mormak D. A., Casida L. E. 1985. Study of Bacillus subtilis endospores in soil by use of a modified endospore stain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1356–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ortega J., et al. 2007. Infection of internal umbilical remnant in foals by Clostridium sordellii. Vet. Pathol. 44:269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paredes C. J., Alsaker K. V., Papoutsakis E. T. 2005. A comparative genomic view of clostridial sporulation and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:969–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramirez N., Abel-Santos E. 2010. Requirements for germination of Clostridium sordellii spores in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 192:418–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramirez N., Liggins M., Abel-Santos E. 2010. Kinetic evidence for the presence of putative germination receptors in Clostridium difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 192:4215–4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ridlon J. M., Kang D.-J., Hylemon P. B. 2006. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 47:241–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Riggs M. M., et al. 2007. Asymptomatic carriers are a potential source for transmission of epidemic and nonepidemic Clostridium difficile strains among long-term care facility residents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:992–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rolfe R. D., Helebian S., Finegold S. M. 1981. Bacterial interference between Clostridium difficile and normal fecal flora. J. Infect. Dis. 143:470–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ross C., Abel-Santos E. 2010. The Ger receptor family from sporulating bacteria. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 12:147–158 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Russell D. W. 2003. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:137–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ryan J., et al. 2010. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile in an Irish continuing care institution for the elderly: prevalence and characteristics. Irish J. Med. Sci. 179:245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schroepfer G. J. 1981. Sterol biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 50:585–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sebaihia M., et al. 2006. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat. Genet. 38:779–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Setlow P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:550–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shimada K., Bricknell K. S., Finegold S. M. 1969. Deconjugation of bile acids by intestinal bacteria: review of literature and additional studies. J. Infect. Dis. 119:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sinave C., Le Templier G., Blouin D., Léveillé F., Deland É. 2002. Toxic shock syndrome due to Clostridium sordellii: a dramatic postpartum and postabortion disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1441–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sitruk-Ware R., Spitz I. M. 2003. Pharmacological properties of mifepristone: toxicology and safety in animal and human studies. Contraception 68:409–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith K. E., Ahmed F., Antoniou T. 1993. Microbial transformations of steroids. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 21:1077–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sorg J. A., Sonenshein A. L. 2008. Bile salts and glycine as cogerminants for Clostridium difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 190:2505–2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sorg J. A., Sonenshein A. L. 2009. Chenodeoxycholate is an inhibitor of Clostridium difficile spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 191:1115–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sorg J. A., Sonenshein A. L. 2010. Inhibiting the initiation of Clostridium difficile spore germination using analogs of chenodeoxycholic acid, a bile acid. J. Bacteriol. 192:4983–4990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spitz I. M. 2009. Clinical utility of progesterone receptor modulators and their effect on the endometrium. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 21:318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stabler R. A., Dawson L. F., Phua L. T. H., Wren B. W. 2008. Comparative analysis of BI/NAP1/027 hypervirulent strains reveals novel toxin B-encoding gene (tcdB) sequences. J. Med. Microbiol. 57:771–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Strauss J. F., Martinez F., Kiriakidou M. 1996. Placental steroid hormone synthesis: unique features and unanswered questions. Biol. Reprod. 54:303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tait A. S., Butts C. L., Sternberg E. M. 2008. The role of glucocorticoids and progestins in inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84:924–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xu X. X., Lambeth J. D. 1989. Cholesterol sulfate is a naturally occurring inhibitor of steroidogenesis in isolated rat adrenal mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7222–7227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]