Abstract

The roles of DNA repair by apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonucleases alone, and together with DNA protection by α/β-type small acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP), in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance to different types of radiation have been studied. Spores lacking both AP endonucleases (Nfo and ExoA) and major SASP were significantly more sensitive to 254-nm UV-C, environmental UV (>280 nm), X-ray exposure, and high-energy charged (HZE)-particle bombardment and had elevated mutation frequencies compared to those of wild-type spores and spores lacking only one or both AP endonucleases or major SASP. These findings further implicate AP endonucleases and α/β-type SASP in repair and protection, respectively, of spore DNA against effects of UV and ionizing radiation.

TEXT

Bacterial endospores of Bacillus species are among the most durable forms of life, and they owe much of their longevity to mechanisms that (i) protect DNA from damage during spore dormancy and (ii) repair DNA damage upon spore germination (31, 32, 40). DNA lesions are produced by artificial and environmental DNA-damaging agents. One predominant type of DNA damage produced by radiation is the modification or loss of a base; thus, apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites are expected to be a frequent lesion in DNA exposed to ionizing radiation (11, 12, 20, 22), mainly due to DNA's reaction with reactive oxygen species (ROS) (2). AP sites block DNA replication and lead to increased rates of mutagenesis (9, 23). Two AP endonucleases, ExoA and Nfo (38, 43), have been implicated in DNA repair in germinating Bacillus subtilis spores (1, 21, 37). However, possible roles of ExoA and Nfo alone and together with DNA protection by α/β-type small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP) in spore resistance to and mutagenesis by different types of radiation (35, 36, 44, 45) have not been explored.

In this communication, we have examined the roles of ExoA, Nfo, and SASP in spore resistance to germicidal UV (254 nm) and environmentally relevant polychromatic (280 to 400 nm) UV radiation, as well as to sparsely ionizing (X rays) and densely ionizing (high-energy charged [HZE] particle) radiation. Since AP sites can cause errors in DNA replication (i.e., are mutagenic), we also determined the frequency of resistance to nalidixic acid (Nalr) of irradiated AP repair-deficient, SASP-deficient, and wild-type spores to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in spore resistance to UV and ionizing radiation (4, 19, 32, 40).

Strains used in this work are listed in Table 1, and all are isogenic with the wild-type strain PS832. Spores were obtained by cultivation under vigorous aeration in double-strength liquid Schaeffer sporulation medium (39), and spores were purified and stored as described previously (27–29). When appropriate, chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), neomycin (10 μg/ml), or tetracycline (10 μg/ml) was added to the medium. Spore preparations consisted of single spores with no detectable clumps and were free (>99%) of growing cells, germinated spores, and cell debris, as seen with a phase-contrast microscope (27–29, 41).

Table 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this studya

| Strain | Genotype and phenotype | Source and reference |

|---|---|---|

| PS832 | Trp+ revertant of strain 168 (wild type) | P. Setlow (13) |

| PS356 | ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− Cmr | P. Setlow (29) |

| PERM450 | ΔsspA ΔsspB ΔexoA::tet Δnfo::neo α−β− Cmr Tetr Neor | M. Pedraza-Reyes (21) |

| PERM452 | ΔexoA::tet Tetr | M. Pedraza-Reyes (21) |

| PERM453 | Δnfo::neo Neor | M. Pedraza-Reyes (21) |

| PERM454 | ΔexoA::tet Δnfo::neo Tetr Neor | M. Pedraza-Reyes (21) |

Cmr, resistant to chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml); Tetr, resistant to tetracycline (10 μg/ml); Neor, resistant to neomycin (10 μg/ml).

Preparation of spore samples for radiation exposure has been described in detail previously (28, 30). Spores were exposed to monochromatic 254-nm UV-C, UV-A plus UV-B [UV-(A+B)] (280 to 400 nm), UV-A (320 to 400 nm), or X rays (150 keV/14 mA) as described previously (30). HZE particle irradiation was performed at the Heavy Ion Medical Accelerator (HIMAC) at the National Institute for Radiological Sciences (NIRS) in Chiba, Japan, under the aegis of HIMAC research project 20B463. The following two ion species were applied (energies [in MeV/nucleon {n}] and linear energy transfer [LET] rates [in keV/μm] are in parentheses): helium (He; 150 MeV/n and 2.2 keV/μm) and iron (Fe; 500 MeV/n and 200 keV/μm). Further details on the irradiation geometry of the HIMAC facility, beam monitoring, dosimetry, and dose calculations have been described previously (27, 28, 34). Spore recovery and viability assays were performed as described previously (27–30). The surviving fraction of B. subtilis spores was determined from the ratio N/N0, with N being the number of CFU of the irradiated sample and N0 that of the nonirradiated controls. Spore inactivation curves, representing fluence- or dose-effect correlations, were obtained as described previously (28, 30). Data are reported as F10 or D10 values, the UV fluence or dose of ionizing radiation killing 90% of the initial spore population (29, 30, 41).

To determine mutation frequencies to Nalr, aliquots of spores of each strain were taken from UV after irradiation with fluences of 100 J/m2 of UV-C (254 nm), 10 kJ/m2 of UV-(A+B) (280 to 400 nm), and 250 kJ/m2 of UV-A (320 to 400 nm) or 250 Gy of X rays or high-energy charged helium and iron ions, as well as untreated samples. Aliquots were spread on 2× LB medium agar plates with or without 20 μg nalidixic acid/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and incubated for 24 to 48 h at 37°C, and the frequencies of mutation to Nalr for spores of each strain were calculated as the number of Nalr colonies/total survivors at the various radiation doses as described previously (10, 27).

All data are expressed as averages ± standard deviations (n = 3). Data were compared statistically using Student's t test. Values were analyzed in multigroup pairwise combinations, and differences with P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant (27, 28, 30).

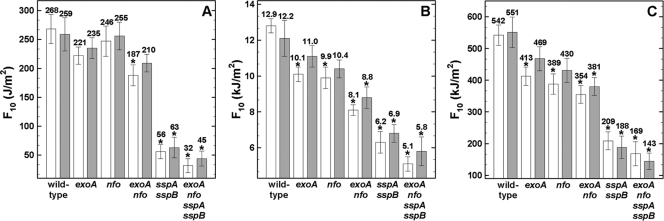

In order to assess the importance of the AP endonucleases ExoA and Nfo and the DNA-protective SASP in B. subtilis spore resistance to different types of radiation, wild-type, SASP-deficient (α−β−), and AP endonuclease-deficient spores, either air-dried monolayers or suspended in water, were irradiated with various UV wavelengths, X rays, and high-energy charged particles. α−β− spores were significantly more sensitive to all UV wavelengths than were wild-type spores, in either the wet or dry state (Fig. 1), as expected (25, 29, 30). Spores lacking either ExoA or Nfo were not significantly more sensitive to 254-nm UV-C than were wild-type spores (Fig. 1A). However, single AP mutant spores were significantly more sensitive to environmentally relevant UV-(B+A) or UV-A when exposed in the dry state (Fig. 1B and C), but not in water (Fig. 1B and C). This finding suggests that there is a higher induction of AP sites by environmental UV radiation in dry spores than in spores in water.

Fig. 1.

Spore resistance to standard germicidal 254-nm UV-C (A), environmentally relevant 280- to 400-nm UV-(A+B) (B), and 320- to 400-nm UV-A (C) radiation. Spores were irradiated as air-dried monolayers (white bars) or in water (gray bars), and F10 values are expressed as averages ± standard deviations (n = 3) as described in the text. Asterisks indicate F10 values that were significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) from those for wild-type spores. Note the differences in the y axes between panels A, B, and C.

Spores of the exoA nfo mutant were significantly more sensitive to 254-nm UV-C than were wild-type spores in the dry state, but not in the wet state (Fig. 1A). However, spores of the double mutant were significantly more sensitive to environmentally relevant UV-(A+B) and UV-A when treated either wet or dry (Fig. 1B and C). α−β− spores lacking ExoA and Nfo appeared slightly more sensitive than spores lacking only SASP to all UV wavelengths tested, in both the dry and the wet states, but these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 1). Taken together, the results from previous (29, 31, 33, 40) and present experiments indicate that (i) SASP are important protectants of DNA against damage by germicidal and environmentally relevant UV radiation-induced damage, and (ii) both ExoA and Nfo play a role in spore resistance to DNA damage caused by environmentally relevant UV-B and UV-A wavelengths. It is well known that solar UV exerts its lethal effects through direct interaction with spore DNA and indirectly via the generation of ROS, such as peroxide, superoxide, or hydroxyl radicals (reviewed in references 5 and 6). Examples of direct UV damage include pyrimidine dimers, such as the “spore photoproduct” (SP) 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine, cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs), and 6-4 photoproducts (5, 13). These photoproducts are produced much more efficiently by 254-nm UV-C and the shorter-wavelength UV-B (290 to 320 nm) component of sunlight than they are by longer-wavelength UV-A (320 to 400 nm) (5, 19, 41). In contrast, nonspecific DNA damage, such as double-strand breaks (DSB), single-strand breaks (SSB), and AP sites are more likely to be produced indirectly from UV-A via ROS production (41, 42). Slieman and Nicholson (41) reported that CPDs were preferentially produced in spores exposed to the UV-B component of sunlight and that nonspecific DSB and SSB were formed mainly when spores were exposed to the UV-A component of sunlight. In their work, the assessment of the induction of UV-induced photoproducts relied on neutral agarose gel electrophoresis, which has limited sensitivity (8). Consequently, Slieman and Nicholson (41) did not detect AP sites in the DNA of UV-treated spores, whereas we observed clear differences in spore resistance to environmental UV radiation, depending on the presence or absence of AP endonucleases (Fig. 1B and C).

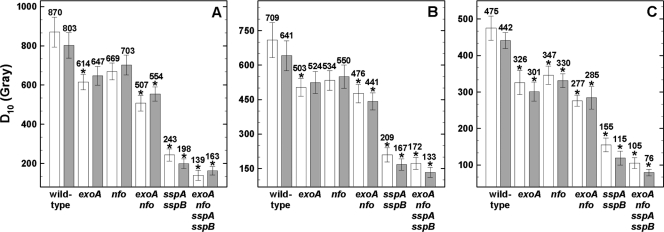

We next examined the roles of ExoA and Nfo and SASP in spore resistance to ionizing radiation from X rays and high-energy charged-particle beam irradiation (Fig. 2). Spores lacking both ExoA and Nfo, α−β− spores, and α−β− spores also lacking ExoA or Nfo were all significantly more sensitive than wild-type spores to ionizing radiation, whether exposed in the wet or dry state (Fig. 2). These results show that (i) both ExoA and Nfo play a role in the repair of X-ray and high-energy particle damage to spore DNA, and (ii) irradiation with X rays or HZE particles generates AP sites in spore DNA.

Fig. 2.

Spore resistance to X rays (A) and high-energy charged helium (B) and iron (C) ions. Spores were irradiated as air-dried monolayers (white bars) or in water (gray bars), and D10 values are expressed as averages ± standard deviations (n = 3) as described in the text. Asterisks indicate D10 values that were significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) compared to wild-type spores. Note the differences in the y axes between panels A, B, and C.

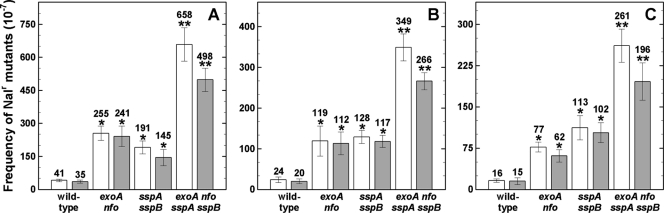

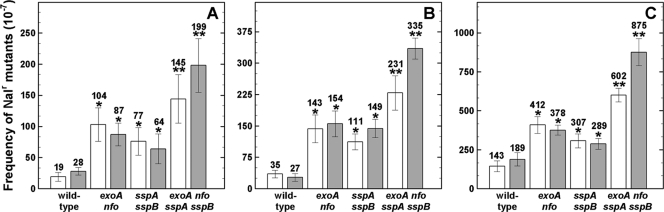

In addition to spore inactivation kinetics, we measured mutagenesis of AP repair-deficient, α−β−, and wild-type spores by germicidal and environmental UV (Fig. 3) and ionizing X rays and HZE particles (Fig. 4). Independent of the type and quality of radiation, α−β− exoA nfo spores showed a significantly higher mutation frequency than α−β−, exoA nfo, or wild-type spores, with the order α−β− exoA nfo > α−β− > exoA nfo > wild-type spores (Fig. 3 and 4). Mutagenesis to Nalr also exhibited wavelength dependence in the order 254 nm > 280 to 400 nm > 320 to 400 nm (Fig. 3A to C), in agreement with previous work (19, 35, 45). The level of mutagenesis to Nalr also depended on the LET of the applied ion species and radiation, also in agreement with previous work (16, 18, 27, 45).

Fig. 3.

Mutation frequencies to Nalr of dormant spores of different strains irradiated with 100 J/m2 of 254-nm UV-C (A), 10 kJ/m2 of UV-(A+B) (B), and 250 kJ/m2 of UV-A (C) radiation. Spores were exposed as air-dried monolayers (white bars) or in water (gray bars), and values are averages ± standard deviations for triplicate determinations in three separate experiments as described in the text. One asterisk indicates a mutation frequency that was significantly different from that of wild-type spores, and two asterisks indicate a mutation frequency that was also significantly different from that of α−β− spores (Student's t test; P ≤ 0.05). Note the differences in the y axes in the different panels. The spontaneous mutation frequency to Nalr of the tested strains ranged from 1.6 × 10−7 to 8.3 × 10−7, in good agreement with previous data (10).

Fig. 4.

Mutation frequencies to Nalr of dormant spores of different strains irradiated with 250 Gy of X rays (A) and high-energy helium ions and (B) and iron ions (C). Spores were exposed as air-dried monolayers (white bars) or in water (gray bars), and values are averages ± standard deviations for triplicate determinations in three separate experiments as described in the text. One asterisk indicates a mutation frequency that was significantly different from that of wild-type spores, and two asterisks indicate a mutation frequency that was also significantly different from that of α−β− spores (Student's t test; P ≤ 0.05). Note the differences in the y axes in the different panels. The spontaneous mutation frequency to Nalr of the tested strains ranged from 1.6 × 10−7 to 8.3 × 10−7, in good agreement with previous work (10).

Base excision repair (BER) is a major pathway involved in repair of a wide variety of DNA base damage resulting from exposure to various chemical (e.g., hydrogen peroxide) and physical (e.g., dry and wet heat, UV and ionizing radiation) insults (2, 3, 7, 15, 24, 26). In contrast to initial steps in BER, which require a large number of lesion-specific N-glycosylases that create AP sites, ExoA and Nfo are the major B. subtilis AP endonucleases that nick DNA at AP sites, leading to gap filling by DNA polymerase I (14). In contrast to the situation in vegetative cells, relatively little is known about how BER contributes to spore resistance to DNA-damaging agents (21, 37). This communication confirms and extends (i) the essential role of SASP as key spore DNA protectants against UV and ionizing radiation (17, 21, 28, 29), (ii) the important role of ExoA and Nfo as AP repair enzymes during spore germination and outgrowth (21, 37, 38), and (iii) the major roles that SASP and AP enconucleases play in the prevention of both lethal and mutagenic damage to spore DNA.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Andrea Schröder for her excellent skillful technical assistance during the sample preparation and analyses. We also thank Thomas Berger and Hisashi Kitamura for their superb support and continual readiness to help during the heavy ion irradiations. We are grateful to Takeshi Murakami and the HIMAC operators for their technical assistance and beam monitoring. The authors acknowledge Marcelo Barraza Salas's help during sample analyses (supported by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia [CONACYT] of Mexico).

The results on spore resistance to high-energy charged-particle bombardment will be included in the research reports of HIMAC project 20B463 (R.M.).

This study was supported in part by grant CBP.EAP.CLG.983747 from the NATO Science for Peace Program to R.M., grants from the Army Research Office (P.S.), México CONACYT grant 84482 (M.P.-R.), and NASA (NNA06CB58G) and USDA (FLA-MCS-04602) grants to W.L.N.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barraza-Salas M., et al. 2010. Effects of forespore-specific overexpression of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease Nfo on the DNA-damage resistance properties of Bacillus subtilis spores. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 302:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blaisdell J. O., Harrison L., Wallace S. S. 2001. Base excision repair processing of radiation-induced clustered DNA lesions. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 97:25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boiteux S., Guillet M. 2004. Abasic sites in DNA: repair and biological consequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair 3:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Breimer L. H. 1988. Ionizing radiation-induced mutagenesis. Br. J. Cancer 57:6–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cadet J., Douki T., Ravanat J. L. 2010. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49:9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cadet J., Sage E., Douki T. 2005. Ultraviolet radiation-mediated damage to cellular DNA. Mutat. Res. 571:3–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpenter E. P., et al. 2007. AP endonuclease paralogues with distinct activities in DNA repair and bacterial pathogenesis. EMBO J. 26:1363–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan K. C., Koutny L. B., Yeung E. S. 1991. On-line detection of DNA in gel electrophoresis by ultraviolet absorption utilizing a charge-coupled device imaging system. Anal. Chem. 63:746–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clauson C. L., Oestreich K. J., Austin J. W., Doetsch P. W. 2010. Abasic sites and strand breaks in DNA cause transcriptional mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:3657–3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. del Carmen Huesca Espitia L., Caley C., Bagyan I., Setlow P. 2002. Base-change mutations induced by various treatments of Bacillus subtilis spores with and without DNA protective small, acid-soluble spore proteins. Mutat. Res. 503:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dianov G. L., O'Neill P., Goodhead D. T. 2001. Securing genome stability by orchestrating DNA repair: removal of radiation-induced clustered lesions in DNA. Bioessays 23:745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dianov G. L., Sleeth K. M., Dianova I. I., Allinson S. L. 2003. Repair of abasic sites in DNA. Mutat. Res. 531:157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Douki T., Setlow B., Setlow P. 2005. Effects of the binding of α/β-type small, acid-soluble spore proteins on the photochemistry of DNA in spores of Bacillus subtilis and in vitro. Photochem. Photobiol. 81:163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Friedberg E. C., et al. 2006. DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodhead D. T. 1994. Initial events in the cellular effects of ionizing radiations: clustered damage in DNA. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 65:7–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodhead D. T. 1999. Mechanisms for the biological effectiveness of high-LET radiations. J. Radiat. Res. 40(Suppl.):1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hackett R. H., Setlow P. 1988. Properties of spores of Bacillus subtilis strains which lack the major small, acid-soluble protein. J. Bacteriol. 170:1403–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamada N. 2009. Recent insights into the biological action of heavy-ion radiation. J. Radiat. Res. 50:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horneck G., Klaus D. M., Mancinelli R. L. 2010. Space microbiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:121–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hutchinson F. 1985. Chemical changes induced in DNA by ionizing radiation. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 32:115–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ibarra J. R., et al. 2008. Role of the Nfo and ExoA apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in repair of DNA damage during outgrowth of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 190:2031–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindahl T. 2001. Keynote: past, present, and future aspects of base excision repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 68:xvii–xxx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loeb L. A., Preston B. D. 1986. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu. Rev. Genet. 20:201–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lomax M. E., Gulston M. K., O'Neill P. 2002. Chemical aspects of clustered DNA damage induction by ionising radiation. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 99:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mason J. M., Setlow P. 1986. Essential role of small, acid-soluble spore proteins in resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to UV light. J. Bacteriol. 167:174–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCullough A. K., Dodson M. L., Lloyd R. S. 1999. Initiation of base excision repair: glycosylase mechanisms and structures. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:255–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moeller R., et al. 2010. Astrobiological aspects of the mutagenesis of cosmic radiation on bacterial spores. Astrobiology 10:509–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moeller R., et al. 2008. Roles of the major, small, acid-soluble spore proteins and spore-specific and universal DNA repair mechanisms in resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to ionizing radiation from X-rays and high-energy charged-particle bombardment. J. Bacteriol. 190:1134–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moeller R., Setlow P., Reitz G., Nicholson W. L. 2009. Roles of small, acid-soluble spore proteins and core water content in survival of Bacillus subtilis spores exposed to environmental solar UV radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5202–5208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moeller R., et al. 2007. Role of DNA repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance to extreme dryness, mono- and polychromatic UV and ionizing radiation. J. Bacteriol. 189:3306–3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nicholson W. L., Munakata N., Horneck G., Melosh H. J., Setlow P. 2000. Resistance of bacterial endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:548–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nicholson W. L., Schuerger A. C., Setlow P. 2005. The solar UV environment and bacterial spore UV resistance: considerations for Earth-to-Mars transport by natural processes and human spaceflight. Mutat. Res. 571:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nicholson W. L., Setlow B., Setlow P. 1991. Ultraviolet irradiation of DNA complexed with alpha/beta-type small, acid-soluble proteins from spores of Bacillus or Clostridium species makes spore photoproduct but not thymine dimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:8288–8292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Okayasu R., et al. 2006. Repair of DNA damage induced by accelerated heavy ions in mammalian cells proficient and deficient in the non-homologous end-joining pathway. Radiat. Res. 165:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pfeifer G. P., You Y. H., Besaratinia A. 2005. Mutations induced by ultraviolet light. Mutat. Res. 571:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Powers E. L., Lyman J. T., Tobias C. A. 1968. Some effects of accelerated charged particles on bacterial spores. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 14:313–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salas-Pacheco J. M., Setlow B., Setlow P., Pedraza-Reyes M. 2005. Role of the Nfo (YqfS) and ExoA apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in protecting Bacillus subtilis spores from DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 187:7374–7381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salas-Pacheco J. M., Urtiz-Estrada N., Martínez-Cadena G., Yasbin R. E., Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. YqfS from Bacillus subtilis is a spore protein and a new functional member of the type IV apurinic/apyrimidinic-endonuclease family. J. Bacteriol. 185:5380–5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schaeffer P., Millet J., Aubert J.-P. 1965. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 45:704–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Setlow P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:514–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Slieman T. A., Nicholson W. L. 2000. Artificial and solar UV radiation induces strand breaks and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in Bacillus subtilis spore DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tyrrell R. M. 1992. Inducible responses to UV-A exposure, p. 59–64 In Urbach F. (ed.), Biological responses to ultraviolet-A radiation. Valdenmar Publishing, Overland Park, KS [Google Scholar]

- 43. Urtiz-Estrada N., Salas-Pacheco J. M., Yasbin R. E., Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. Forespore-specific expression of Bacillus subtilis yqfS, which encodes type IV apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, a component of the base excision repair pathway. J. Bacteriol. 185:340–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yokoya A., et al. 2008. DNA damage induced by the direct effect of radiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 77:1280–1285 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zamenhof S., Reddy T. K. 1967. Induction of mutations by ultraviolet irradiation of spores of Bacillus subtilis. Radiat. Res. 31:112–120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]