Abstract

Transcription factor GATA-3 is vital for multiple stages of T cell and natural killer (NK) cell development, and yet the factors that directly regulate Gata3 transcription during hematopoiesis are only marginally defined. Here, we show that neither of the Gata3 promoters, previously implicated in its tissue-specific regulation, is alone capable of directing Gata3 transcription in T lymphocytes. In contrast, by surveying large swaths of DNA surrounding the Gata3 locus, we located a cis element that can recapitulate aspects of the Gata3-dependent T cell regulatory program in vivo. This element, located 280 kbp 3′ to the structural gene, directs both T cell- and NK cell-specific transcription in vivo but harbors no other tissue activity. This novel, distant element regulates multiple major developmental stages that require GATA-3 activity.

INTRODUCTION

Maturation of T lineage lymphocytes is one of the most clearly defined pathways in all of developmental biology. Immature hematopoietic cells from the bone marrow migrate through the bloodstream to initially populate the thymus. The earliest detectable thymic progenitor (early T lineage progenitors [ETP]) cells differentiate uniquely in the thymic microenvironment through several early stages in which neither the CD4 nor CD8 coreceptors are expressed (double-negative [DN] cells, stages 2 to 4) and thence into cells which express both CD4 and CD8 (double-positive [DP] cells) and finally generate either CD4 single-positive (CD4 SP; CD4+ CD8−) cells or CD8 single-positive (CD8 SP; CD4− CD8+) cells. CD4+ thymocytes have the potential to differentiate into helper (Th) or regulatory T cells, while CD8 SP cells are programmed to fulfill cytotoxic functions. These mature single-positive thymocytes exit the thymus to execute their defined effector functions after activation in the periphery.

The zinc-finger transcription factor GATA-3 (23, 49) is expressed throughout T cell development (20), peaking in abundance in CD4 SP and Th2 cells (11, 17, 18, 38, 44, 52, 53). GATA-3 function has been shown to be vital for the generation of ETP (19), DN4, and CD4 SP cells (37) and for the differentiation and function of Th2 cells (36, 54). While its expression is critical for normal T cell development, enforced ectopic expression of GATA-3 can have catastrophic consequences (3, 7, 33, 34, 40, 41), such as causing T cell lymphoma in transgenic mice (34, 45) and converting DP cells into a premalignant state (45). Additionally, GATA-3 plays a role in the aberrant survival of T lymphoma cells in E2A mutant mice (48). These results, taken together, suggest that both the timing and abundance of GATA-3 must be exquisitely regulated for proper development of the T cell lineage.

Ours and many other laboratories have sought to define how this key T lymphocyte regulatory protein is itself so precisely modulated during T cell development, but prior studies have failed to conclusively identify Gata3 transcriptional cis elements that are capable of conferring appropriate regulatory properties to this gene in vivo. In exploring the transcriptional networks that lead to proper T cell differentiation, potential trans upstream regulators of Gata3 have been proposed (1, 12, 31, 50, 51). However, while Gata3 proximal promoter sequences are capable of activating its transcription in transfection experiments (14), we report here that neither of the Gata3 promoters (4) is capable of conferring such activity in vivo. Since previous studies have not demonstrated a functional requirement for the direct association of any of the proposed epistatic Gata3 regulators (Notch/CSL, c-Myb, T cell factor 1 [TCF-1], and Dec2) with their cognate binding sites in the Gata3 promoters through site mutagenesis followed by in vivo activity tests, the experiments described here clearly demonstrate that those sequences are insufficient for thymic T cell-specific expression.

We and many others have shown that GATA-3 plays critical roles in quite diverse developmental events (5, 15, 21, 24, 25, 30, 32, 43) and that Gata3 expression in those tissues and organs is usually dictated by individual tissue-specific enhancers (14, 16, 26, 27, 29). Here, we report the identification of a cis element that regulates Gata3 expression during multiple stages of T cell development and that is located far 3′ to the Gata3 gene. This element induces the transcription of a reporter gene in vivo in thymic ETP, natural killer (NK), γδT, CD4 SP, and peripheral CD4+ stages and thus its expression pattern reflects that of endogenous Gata3. While additional cis elements may be required to fully support appropriate expression of Gata3 during T cell development, this distant element appears to confer activity at several of the major developmental transitions that are required for Gata3 T cell-specific transcriptional control in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Transgenic mice were generated using standard techniques in the University of Michigan Transgenic Animal Model Core or using our own instruments. Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) or plasmid DNAs were microinjected into (C57BL/6J × SJL)F2 fertilized oocytes. Transgenic lines were established by crossing onto a CD1 background. GATA-3–enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) fusion cDNA knock-in mice (Gata3g/+) were generated previously (19) (T. Moriguchi et al., unpublished data). Gata3z/+ mice (17) and TgB125.LacZ mice (the genome sequence-revised endpoints are −451 to +211 kb, with respect to the translation start site) were described previously (16, 26, 27). All animal experiments were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals of the University of Michigan and were performed according to their guidelines (IACUC approval no. 8611).

BAC recombineering.

The RPCI-23 C57BL/6J mouse BACs used in this study are described by the following endpoints (±0.5 kbp) relative to the Gata3 translational start site: 43G17, +49/+294; 193E6, +128/+330; 263A8, +269/+473. Modification of BAC clones was performed as previously described (22, 28).

eGFP reporter BAC recombinants.

The pGATA-3–eGFP fusion cDNA plasmid containing the genomic 1b promoter (unpublished data) was digested with NcoI and self-ligated to remove only the Gata3 cDNA; this is referred to as the pG3-1b.eGFP plasmid. pG3-1b.eGFP was digested with EcoRI and NotI to excise the fragment containing the 1b promoter (sequences corresponding to bp −1314 to +1, with respect to the translational initiation site) and eGFP cassette. A pG3 BAC-targeting vector (unpublished data), which contains an Frt-Neo-Frt selection cassette, the 1b-LacZ reporter, and two homology arms that were identical to two segments of the SacBII gene in the pBACe3.6 vector backbone, was digested with EcoRI and NotI to remove the 1b-LacZ cassette. The EcoRI-NotI fragment of pG3-1b.eGFP and the EcoRI-NotI fragment of the pG3 BAC-targeting vector were ligated to generate the 1b.eGFP BAC-targeting plasmid. The resultant plasmid was digested, purified, and used for BAC homologous recombination. The recombinant BAC clones were verified by restriction enzyme digest pattern and Southern blotting (data not shown).

Deletion of TCE-7.1 from BAC 43G17.

Two homology arms that were located immediately adjacent to either end of TCE-7.1 were amplified by PCR and then subcloned into the pFrtNeo plasmid, which contains the Frt-Neo-Frt cassette (22). BAC homologous recombination was performed using the purified targeting fragment as described previously (22). The resultant recombinant BAC (43G17Δ7.1) was verified by restriction enzyme digestion and Southern blotting (data not shown).

Construction of an eGFP reporter plasmid containing TCE-7.1.

To prepare the 1b.eGFP reporter plasmid, the Neo cassette was removed from the 1b.eGFP BAC-targeting plasmid. BAC 43G17 DNA was digested with SalI and KpnI. The 7.1-kbp SalI-KpnI fragment (TCE-7.1 fragment) was gel purified and cloned into the SalI/KpnI sites of pGEM-4Z. The TCE-7.1 fragment was verified by restriction digestion pattern and sequencing. To generate the 7.1-1b.eGFP reporter plasmid, the SalI-KpnI TCE-7.1 fragment from the pGEM-4Z 7.1-kbp plasmid, the PacI-SalI fragment of the 1b.eGFP plasmid, and the PacI-KpnI fragment of pNEB193 were ligated together. The resultant 7.1-1b.eGFP plasmid was digested with PmeI and KpnI and used for microinjection. To generate Gata3-1b promoter-only transgenic mice, the 1b.eGFP plasmid was digested with PacI and PmeI and used for microinjection.

Flow cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions of thymocytes, bone marrow, splenocytes, or peripheral blood were incubated with Fc Block (BD Biosciences). Splenocytes and peripheral blood were hemolyzed using NH4Cl before incubation with Fc Block. The following antibodies (either from eBioscience or from BD Biosciences) were then applied: phycoerythrin-cyanine 7-conjugated (PE-Cy7) anti-CD4 (RM4-5), PE–anti-CD4 (H129.19), allophycocyanin (APC)–anti-CD8a (53-6.7), biotin–anti-CD8a (53-6.7), PE–anti-CD44 (IM7), peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5 (PerCP-Cy5.5)–anti-CD62L (MEL-14), PE–Cy7–anti- CD25 (PC61.5), APC–anti-c-Kit (2B8), PE–anti-CD3e (145-2C11), PE–Cy7–anti-CD3e (145-2C11), biotin–anti-CD3e (145-2C11), APC–anti-γδTCR (T cell receptor) (GL3), biotin–anti-γδTCR (GL3), PE–Cy7–anti-CD19 (1D3), biotin–anti-CD19 (1D3), APC–anti-CD49b (DX5), APC–anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), biotin–anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), APC–eFluor780–anti-Mac1 (M1/70), biotin–anti-Mac1 (M1/70), eFluor450–anti-Gr1 (RB6-8C5), biotin–anti-Gr1 (RB6-8C5), APC–anti-TER119 (TER-119), biotin–anti-TER119 (TER-119), PE–anti-CD71 (R17217), PerCP–Cy5.5–anti-TCRβ (H57-597), biotin–anti-TCRβ (H57-597), PE–anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), biotin–anti-NK1.1 (PK136), biotin–anti-CD11c (N418), PE–Cy7–anti-gamma interferon (anti-IFN-γ) (XMG1.2), APC–anti-interleukin 4 (anti-IL-4) (11B11), PE–Cy7–anti-Sca1 (D7), streptavidin eFluor450. Immature T cells were analyzed as previously described (19). The FluoReporter LacZ flow cytometry kit (Molecular Probes) was used to analyze LacZ expression according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were analyzed on either FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) or FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) or propidium iodide. Acquired data were analyzed using either Weasel (WEHI Biotechnology Centre), FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc.), FACSDiva, or Cell Quest (BD Biosciences) software. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of eGFP was normalized using the LinearFlow green flow cytometry intensity calibration kit (Molecular Probes) in most experiments. These calibration beads were excited by 488 nm, and fluorescence measurements were performed in the same manner as eGFP measurements in every experiment. A standard curve was generated based on acquired calibration bead data, and eGFP MFI of each sample was normalized using the standard curve.

In vitro CD4+ T cell differentiation assay.

CD4+ CD25− splenocytes were purified using the Dynal mouse CD4-negative isolation kit (Invitrogen) in combination with affinity-purified anti-mouse CD25 antibody (PC61.5; eBioscience) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 25 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Isolated CD4+ cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3e antibody (10 μg/ml; 145-2C11; BD Biosciences) and anti-CD28 antibody (10 μg/ml; 37.51; BD Biosciences). For nonpolarizing conditions, 10 ng/ml recombinant human IL-2 (PeproTech) was added. For Th1-polarizing condition, 10 μg/ml anti-IL-4 antibody (11B11; BD Biosciences), 10 ng/ml IL-2, and 5 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-12 (PeproTech) were added. For Th2-polarizing condition, 10 μg/ml anti-IFN-γ antibody (XMG1.2; BD Biosciences), 10 μg/ml anti-IL-12 antibody (C17.8; BD Biosciences), 10 ng/ml IL-2, and 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-4 (PeproTech) were added. On day 4 of culture, cells were diluted. On day 6, cells were restimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3e and anti-CD28 antibodies for 6 h. During the last 2 h, 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Half of the cells were analyzed using flow cytometry to evaluate eGFP expression, while the other half were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences), and used for intracellular staining to confirm differentiation by detecting IFN-γ and IL-4 (data not shown).

In vivo and ex vivo imaging.

Postnatal day 4 mice (anesthetized with isoflurane vapor) or fresh organs from adult mice were analyzed using an IVIS spectrum (Caliper Life Sciences). The excitation and emission wavelengths used in this study were 465 nm and 520 nm, respectively. Acquired data were analyzed using Living Image 4.0 software.

Bioinformatics.

Comparisons of mouse genomic sequences with human, dog, and rat were performed using VISTA (http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml). The information describing the position of DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) in human CD4+ T cells were obtained from the UCSC genome browser (6, 8–10, 47).

ESTs.

The information regarding the two expressed sequence tags (ESTs) that are located within 300 kbp of TCE-7.1 is as follows: AK080422, Mus musculus 7-day neonate cerebellum cDNA, RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone ID A730010B06 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGene?hgg_gene=uc008ihc.1&hgg_prot=&hgg_chrom=chr2&hgg_start=9512845&hgg_end=9519470&hgg_type=knownGene&db=mm9&hgsid=186400201); and AK035738, Mus musculus adult male urinary bladder cDNA, RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone ID 9530097M04 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGene?hgg_gene=uc008ihb.1&hgg_prot=&hgg_chrom=chr2&hgg_start=9274116&hgg_end=9369303&hgg_type=knownGene&db=mm9&hgsid=186400201).

RESULTS

Neither the Gata3-1a nor -1b promoter confers T cell autonomous expression in vivo.

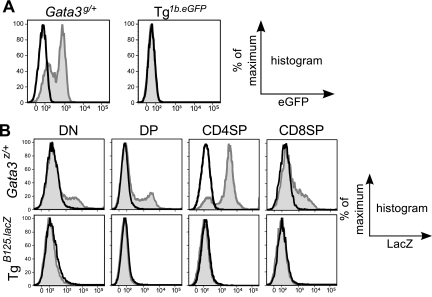

Given our previous report that sequences in the Gata3-1b (gene-proximal) promoter exerted differential T cell activity in transfection experiments (14), we first asked whether the same promoter was capable of directing T cell transcription in vivo. Transgenic mice were generated in which an eGFP reporter cassette was directed by 1b promoter sequences (1b.eGFP), and expression in T cells was monitored by flow cytometry. Surprisingly, the reporter gene failed to be expressed in T cells of adult transgenic (Tg1b.eGFP) mice (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, mice expressing a germ line eGFP–GATA-3 fusion protein (Gata3g/+) (Fig. 1A) or a germ line lacZ insertion at the Gata3 initiation codon (Gata3z/+) (Fig. 1B) both robustly express the reporters in T cells (17, 19). These data demonstrate that the Gata3-1b promoter is insufficient to confer T cell-specific transcription in vivo and, therefore, that an additional cis element(s) is required.

Fig. 1.

Neither the Gata3-1b promoter alone nor a 662-kbp Gata3/LacZ YAC containing both 1a and 1b promoters recapitulates GATA-3 activity in thymocytes. (A) eGFP expression in CD4 SP thymocytes from Gata3g/+ mice (left, gray shaded histogram) or Tg1b.eGFP mice (right, gray shaded histogram). The black-line (open) histograms indicate eGFP fluorescence in wild-type thymocytes. Data represent at least three mice of each genotype. (B) LacZ expression in thymocytes stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies was examined by flow cytometry. Each population was gated as depicted. The gray shaded histograms indicate fluorescein di-β-d-galactopyranoside fluorescence (13) resulting from hydrolysis due to β-galactosidase expression in either Gata3-lacZ knock-in (Gata3z/+) (17) or B125-lacZ YAC transgenic (27) mice, while the black-line (open) histograms indicate expression in wild-type mice. These individual data are representative of results from at least three mice of each genotype.

A potent T cell element located far 3′ to Gata3.

We previously generated B125 yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) LacZ reporter transgenic mice harboring 662 kbp of genomic DNA containing the 33-kbp Gata3 structural gene as well as vast swaths of adjacent 5′ (451-kbp) and 3′ (211-kbp) genomic noncoding sequences (Fig. 1B, TgB125.LacZ) (26, 27). We compared β-galactosidase expression in the thymocytes of TgB125.LacZ mice and LacZ germ line knock-in (Gata3z/+) animals. Surprisingly, LacZ expression was not observed in adult TgB125.LacZ thymocytes (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the Gata3z germ line knock-in allele was strongly expressed, most robustly in the CD4 SP population that also abundantly expresses endogenous GATA-3 in thymocytes (Fig. 1B). These data demonstrate that even 662 kbp of contiguous genomic sequence, including the gene and both Gata3 promoters, was insufficient to direct Gata3 T cell transcription in vivo and that the cis elements required for T lineage specification must be located beyond the boundaries of that YAC.

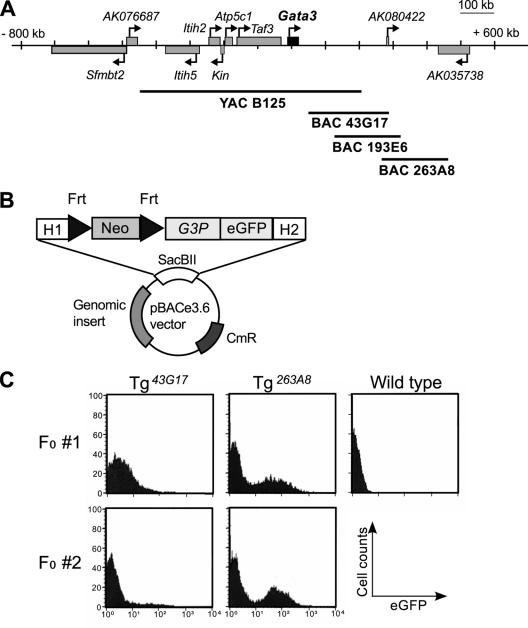

Next, we began to examine sequences lying even further away using the coupled BAC/transgenic (BAC-trap) assay we developed and exploited previously to identify several distant Gata2 urogenital enhancers (22). Three BACs that overlapped and extended 3′ to the B125 YAC (Fig. 2 A) were modified by recombineering (28) to insert an eGFP reporter gene directed by the Gata3-1b (gene-proximal) promoter (1b.eGFP) into each BAC vector backbone (Fig. 2B). The 1b promoter was examined (instead of the more distal 1a promoter) in these studies since more than 98% of peripheral T cell transcripts initiate from exon 1b (51). The three recombineered BACs were used to generate founder transgenic animals, and robust eGFP expression was detected in thymocytes from multiple transgenic animals (Fig. 2C and data not shown) using all three BACs. Although eGFP expression initially appeared to differ between the different BAC clones, after recovery of multiple founders bearing each clone (and after subsequent analysis of multiple BAC transgenic lines), we concluded that the heterogeneity was due to mosaic expression of the transgenes in the founder transgenic mice. Based on the T cell-directed eGFP responses observed in this founder screen, we immediately focused on the region of overlap between the three BAC clones.

Fig. 2.

A candidate T lymphocyte enhancer element is located far 3′ to the Gata3 gene. (A) The Gata3 gene and adjacent genes on mouse chromosome 2. The relative genomic positions of the BAC and YAC clones examined in this study are depicted graphically. (B) Schematic diagram of the targeting cassette used to generate modified BACs. H1 and H2, homology arms; Neo, neomycin resistance gene; G3P, Gata3 promoter; SacBII, SacBII gene present in the vector backbone of the RPCI-23 mouse BAC library; CmR, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene C, founder screening of BAC-trap Tg embryos. eGFP expression in total thymocytes recovered from E18.5 F0 Tg embryos was analyzed by flow cytometry. The results of two independent F0 Tg embryos for each BAC clone are shown; in each case, a fraction of the thymocytes expressed eGFP, except from wild-type embryos.

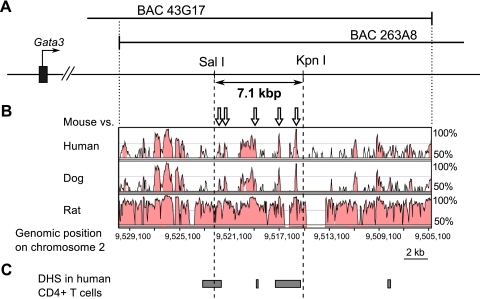

Preliminary bioinformatic analysis revealed (Fig. 3 A and B) that multiple species-conserved noncoding sequence (CNS) elements lie within the overlap (approximately 25 kbp) between the RPCI-23 library BACs 43G17 and 263A8. We further informed the analysis by aligning DHS data from primary human CD4+ T cells (6, 8–10, 47) (Fig. 3C); several of the CNS were close to, or overlapped, DHS sites (Fig. 3). Given the close relationship between conserved sequence elements and DHS sequences with transcriptional control, we hypothesized that the most highly conserved CNS overlapping the DHS (shown in Fig. 3B) might serve as a cis regulatory element that controls T cell-specific Gata3 transcription.

Fig. 3.

Mapping conserved noncoding sequences (CNS) and DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS) in the overlap between two BAC clones. (A) The region of overlap (approximately 25 kbp) between BACs 43G17 and 263A8 is depicted. (B) Genomic sequences within the overlap (mouse chromosome 2, 9,530,005 to 9,504,884) were compared with the human, dog, and rat genomes, respectively. CNSs are colored pink. (C) The DHS homologies corresponding to human CD4+ T cells are depicted as gray rectangles. Open arrows in panel B indicate CNSs that were predicted to be potential regulatory elements (i.e., high ESPERR scores).

A 7.1-kbp genomic fragment directs Gata3 activity at multiple T cell stages.

Within the 25-kbp overlapping BAC interval, we initially focused on a 7.1-kbp SalI/KpnI restriction fragment that contained multiple CNS elements and that also had high predicted regulatory sequence potential (evolutionary and sequence pattern extraction through reduced representations [ESPERR]) scores (42) (data not shown); additionally, this fragment encompassed most of the DHS (Fig. 3), and therefore we assigned to it the preliminary designation TCE-7.1 (7.1-kbp T cell element). First, we asked whether or not this fragment contained T cell enhancer activity by deleting the corresponding region (Δ7.1) via recombineering from the BAC 43G17 clone into which a 1b.eGFP reporter cassette had already been inserted. We chose to examine BAC 43G17 instead of the two others simply because we first observed transcription of eGFP reporter gene in thymocytes of Tg43G17 mice (data not shown). The deletion BAC was then used to generate transgenic mice (Tg43G17Δ7.1). eGFP fluorescence was conspicuously absent in peripheral CD4+ cells in all founder Tg43G17Δ7.1 mice (0/14 transgenic mice expressed eGFP fluorescence) compared to that in the cells of the parental Tg43G17 mice (Table 1), indicating that TCE-7.1 is necessary for direction of reporter gene transcription in T cells. To ask if that same fragment alone was sufficient to enhance T cell transcription, it was linked to the same 1b.eGFP reporter cassette that was used in the BAC vector modification recombineering experiments; this reporter was then used to generate founder transgenic mice (Tg7.1-1b.eGFP). We found that eGFP in peripheral CD4+ T cells increased in all founder mice (6/6) bearing TCE-7.1 linked to the promoter compared to in transgenic mice bearing the 1b promoter alone (Table 1).

Table 1.

eGFP expression in the peripheral blood of F0 Tg mice

| Transgene | No. of mice with CD4+ eGFP+ cells/no. of mice with Tg (PCR+) |

|---|---|

| Tg43G17 | 7/8 |

| Tg43G17Δ7.1 | 0/14 |

| Tg1b.eGFP | 1a/14 |

| Tg7.1-1b.eGFP | 6/6 |

eGFP expression was detected in CD4+ cells and granulocytes (Gr1+Mac1+) in only one founder Tg1b.eGFP mouse. We concluded that it was ectopic expression since the remaining founder Tg1b.eGFP mice never expressed eGFP in CD4+ cells.

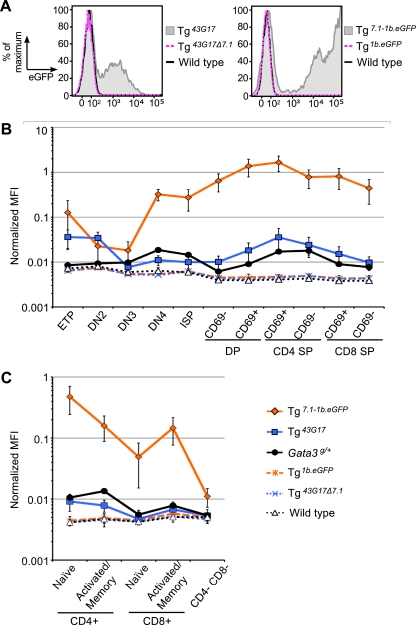

We next established transgenic lines bearing each of these reporters and assayed the lines for when (during T cell development) and where (in which organs) the transgenes were expressed. We initially analyzed thymocytes from multiple established transgenic lines: six lines of Tg7.1-1b.eGFP, four lines of Tg1b.eGFP, five lines of Tg43G17, and three lines of Tg43G17Δ7.1. Thymocytes were electrically gated into DN1 to DN4, DP, CD4SP, and CD8SP stages using anti-CD4, CD8, CD25, and CD44 antibodies; we found that eGFP was expressed in those cells in all lines of both Tg43G17 and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice. In contrast, eGFP expression was not observed in the absence of TCE-7.1 (data not shown). Based on those pilot experiments, we chose two lines of each construct-derived transgenic mouse and examined their T cell expression profiles in detail as described in Materials and Methods. We found that eGFP was expressed in CD4SP CD69+ thymocytes as well as in other stages of both Tg43G17 mice and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice. In contrast, eGFP expression was essentially abolished when TCE-7.1 was deleted, and expression reverted to the levels observed in nontransgenic mice (Fig. 4 A and B and data not shown). Moreover, we found that the pattern of eGFP expression in Tg43G17 mice and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice reflected the expression of endogenous Gata3 during late stages of thymocyte development in which positive selection and CD4 versus CD8 lineage choice occur.

Fig. 4.

A 7.1-kbp fragment (TCE-7.1) within the BAC overlap directs αβ T cell reporter gene transcription. (A) eGFP expression in CD69+ CD4 SP thymocytes from Tg43G17, Tg43G17Δ7.1, Tg7.1-1b.eGFP, Tg1b.eGFP, and wild-type mice. Data are representative of results from at least three individual mice of each genotype. (B and C) Normalized mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of eGFP in each population of thymocytes (B) and splenocytes (C). MFI was normalized using the LinearFlow green flow cytometry intensity calibration kit and presented as percentage of relative fluorescence of calibration beads. Error bars (B and C) denote means ± standard deviations (SD). Two lines of each construct-derived Tg mouse were examined (data not shown), and at least three individual mice of each Tg line were analyzed. Data represent a single line from each construct-derived Tg mouse. Note that all MFI expression data are presented on a log scale. ETP, lineage-negative (Lin−) CD25low c-Kithigh; DN2, Lin− CD25high c-Kithigh; DN3, Lin− CD25high c-Kitlow; DN4, Lin− CD25low c-Kitlow; ISP, TCRbetalow CD8 SP; CD69− DP, TCRbetalow CD69− DP; CD69+ DP, TCRbeta+ CD69+ DP; CD4 SP CD69+, TCRbeta+ CD69+ CD4 SP; CD4 SP CD69−, TCRbeta+ CD69− CD4 SP; CD8 SP CD69+, TCRbeta+ CD69+ CD8 SP; CD8 SP CD69−, TCRbeta+ CD69− CD8 SP; Naïve CD4+, CD4+ CD62Lhigh CD44low; Activated/Memory CD4+, CD4+ CD62Llow CD44high; Naïve CD8+, CD8+ CD62Lhigh CD44low; Activated/Memory CD8+, CD8+ CD62Llow CD44high.

Endogenous Gata3 is induced by T cell receptor (TCR) signaling during positive selection at the DP stage, and this induction requires the activity of transcription factor c-Myb. After DP cells differentiate into intermediate (CD69+) CD4 SP cells, endogenous Gata3 expression remains high and then gradually diminishes during maturation into mature (CD69−) CD4 SP cells. In contrast, there is no induction of Gata3 in intermediate (CD69+) CD8 SP cells, and its level of expression diminishes even further as the cells differentiate into mature (CD69−) CD8 SP cells (18, 31, 34). We observed induced expression of the MFI of eGFP after cell differentiation from the preselection (CD69− DP cells) stage into CD69+ DP cells, where positive selection has begun, in both Tg43G17 and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice. eGFP increased in intermediate CD4 SP cells and declined thereafter in mature CD4 SP cells, as does endogenous Gata3. In CD8 SP cells, eGFP declined, again reflecting the endogenous Gata3 expression pattern (Fig. 4B and data not shown). These results suggest that TCE-7.1 contains cis information required to direct the late stages of Gata3-regulated thymocyte development.

In contrast to late thymocyte development, some differences in expression characteristics of the TCE-7.1 transgenes were detected at earlier stages than the reported expression of endogenous Gata3 mRNA (11, 44). For example, Tg7.1-1b.eGFP and Tg43G17 mice displayed intense eGFP fluorescence at the ETP stage that gradually diminished as they differentiated into the DN2 and DN3 stages (Fig. 4B and data not shown). In addition, Tg7.1-1b.eGFP CD69− DP thymocytes expressed eGFP more intensely than immature CD8 SP (ISP) cells, while Tg43G17 exhibited no difference between those two populations. Neither is true of GATA-3 expression from the endogenous locus (Fig. 4B). Taken together, we tentatively conclude that the cis element(s) that is required to stimulate Gata3 transcription at the DN3 stage (11, 44) or required to negatively regulate Gata3 at the ETP stage must be located beyond the boundaries of the 43G17 BAC, while additional regulatory elements that negatively regulate Gata3 at the CD69− DP stage or positively regulate it at the ISP stage must exist outside TCE-7.1 but may be included within the boundaries of BAC 43G17.

We also analyzed splenocytes to examine reporter gene expression in peripheral T cells in greater detail. Both Tg43G17 and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP displayed higher eGFP MFI in naïve CD4+ cells than in naïve CD8+ cells, which is similar to the pattern of endogenous Gata3. Those activities were essentially ablated in the absence of TCE-7.1 (Fig. 4C and data not shown). These results indicate that TCE-7.1 is critical for transcription in peripheral T cells, although small differences were detectable. For example, eGFP was higher in naïve CD4+ cells than in activated/memory CD4+ cells of both Tg43G17 and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice (Fig. 4C), which again does not perfectly reflect the in vivo changes in GATA-3 that occur during T cell differentiation. In addition, eGFP in naïve and activated/memory CD8+ splenocytes remained high compared to CD4− CD8− splenocytes, especially in Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that TCE-7.1 is vital for transcription of a Gata3 promoter-directed reporter gene in thymocytes and in splenocytes in vivo, although the element within TCE-7.1 may not alone be sufficient to precisely recapitulate all aspects of Gata3 T cell expression. We therefore speculate that additional regulatory elements that negatively regulate Gata3 in peripheral CD8+ T cells may exist outside TCE-7.1 but within the 43G17 BAC.

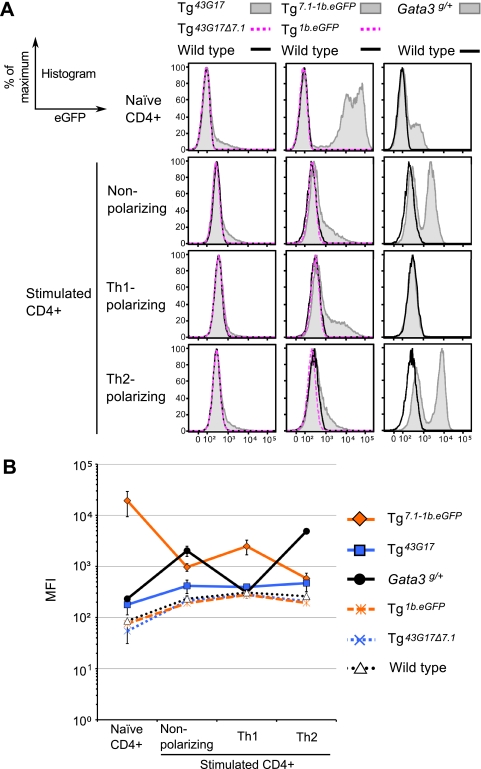

In order to determine whether TCE-7.1 contains the element(s) specifying increased Gata3 transcription in Th2 cells but not in Th1 cells (52, 53), we analyzed the expression of eGFP in CD4+ cells from Tg43G17 mice under a variety of cytokine stimulatory conditions (see Materials and Methods). After stimulation, eGFP in CD4+ cells under Th2-polarizing and nonpolarizing conditions was not significantly altered, although the cells did express low levels of eGFP (Fig. 5), in keeping with the observed properties of GATA-3 expression in vivo. We confirmed that the in vitro polarization of these cells was successful by monitoring cytokine induction (IFN-γ and IL-4) (data not shown). In CD4+ cells recovered from Tg43G17Δ7.1 mice, eGFP was not observed. In contrast, Tg7.1-1b.eGFP CD4+ cells cultured under stimulatory conditions somewhat surprisingly displayed greatly reduced eGFP fluorescence under Th2-polarizing or nonpolarizing conditions compared to that of naïve CD4+ cells. Moreover, Tg7.1-1b.eGFP cells under Th1-polarizing conditions actually displayed higher eGFP expression than under Th2-polarizing or nonpolarizing conditions (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Both results contradict the GATA-3 expression characteristics observed in vivo. These data suggest that TCE-7.1, either in concert with the Gata3-1b promoter or even within the context of the entire BAC43G17 clone, does not contain the regulatory element that specifies Gata3 activation in Th2 cells or in activated CD4+ T cells, although TCE-7.1 does contain an element that is critical for high-basal-level transcription in stimulated CD4+ cells. Furthermore, a putative cis element that must be located outside the boundaries described by TCE-7.1, but within the boundaries specified by BAC 43G17, may additionally be required for the repression of Gata3 in Th1 cells and naïve CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 5.

TCE-7.1 directs reporter gene transcription in stimulated CD4+ cells. (A) Histograms of eGFP in naïve CD4+ splenocytes and stimulated CD4+ splenocytes under various conditions. Data are representative of results from at least three individual mice of each genotype. (B) MFI of eGFP in naïve and stimulated CD4+ splenocytes under various conditions. Note that MFI was not normalized using calibration beads in this experiment. Error bars denote means ± SD. Two lines of each construct-derived Tg mouse were examined (data not shown), and at least three individual mice of each Tg line were analyzed. Data represent a single line from each construct-derived Tg mouse. Note that MFI expression data are presented on a log scale.

TCE-7.1 bears Gata3 T and NK cell-specific regulatory information.

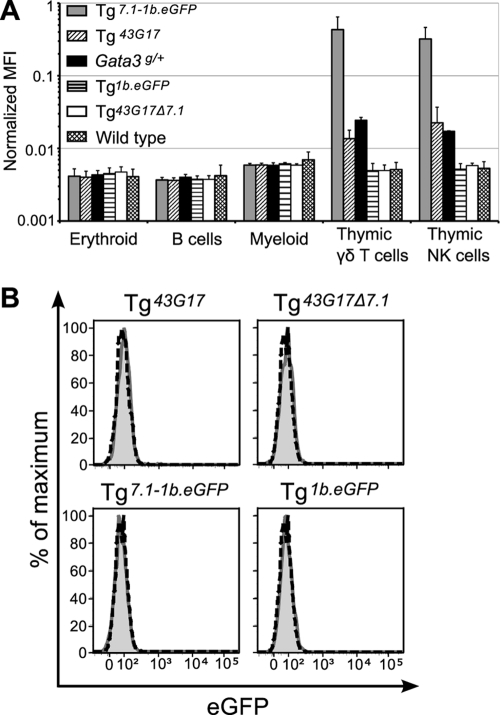

In addition to its well-characterized roles in αβ T cell, sympathoadrenal, kidney, parathyroid, breast epithelial, and epidermal development (5, 15, 21, 24, 25, 30, 32, 43), GATA-3 has been shown to play critical roles in the generation and maturation of NK cells (39, 46). In addition, GATA-3 is expressed in γδ T cells (19) as well as in hematopoietic progenitors (38), although its function there is not well understood. We analyzed NK cells, γδ T cells, and hematopoietic progenitors (lineage− Sca1+ c-Kithi [LSK]) in multiple transgenic lines to ascertain whether TCE-7.1 was also active in those related lymphoid lineages.

Somewhat surprisingly, robust eGFP fluorescence was observed in thymic NK cells and γδ T cells in both Tg7.1-1b.eGFP and Tg43G17 mice, while mice bearing the 7.1-kbp deleted BAC Tg43G17Δ7.1 or mice bearing only the Gata3-1b promoter failed to express eGFP (Fig. 6 A). In contrast to GATA-3-expressing cells (e.g., αβ or γδ T cells or NK cells), other hematopoietic lineages that do not express endogenous GATA-3 also failed to express eGFP, in both Tg7.1-1b.eGFP and Tg43G17 mice (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, neither Tg7.1-1b.eGFP nor Tg43G17 express eGFP in the early hematopoietic progenitor compartment (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrated that TCE-7.1 is active in T and NK cells but not in other hematopoietic lineages or progenitors.

Fig. 6.

Among hematopoietic cells, TCE-7.1 confers only NK cell and αβ and γδ T cell enhancer activity. (A) Normalized MFI of eGFP in erythroid cells (TER119+), B cells (CD19+ B220+ CD3−), and myeloid cells (Gr1+ Mac1+) in the bone marrow, as well as γδ T cells (TCRγδ+) and NK cells (CD3− CD19− DX5+) in the thymus are shown. Error bars denote means ± SD. Note that MFI data are presented on a log scale. (B) eGFP expression in bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors (Lin− Sca1+ c-Kithi). The shaded histograms indicate each Tg mouse, while dashed lines indicate wild-type mice. For both panels A and B, two lines of each construct-derived Tg mouse were examined (data not shown), and at least three individual mice of each Tg line were analyzed. Data represent a single line from each construct-derived Tg mouse.

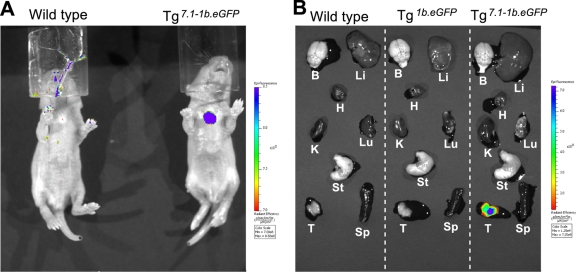

In order to more globally examine whether the eGFP expression conferred by TCE-7.1 was T cell specific, we examined Tg7.1-1b.eGFP expression by IVIS Spectrum whole-body in vivo imaging. Robust eGFP fluorescence was detected exclusively in the thymi of Tg7.1-1b.eGFP neonates (Fig. 7 A). In contrast, other organs in these mice did not display expression above background levels; similarly, neither Tg1b.eGFP nor wild-type mice expressed detectable eGFP (Fig. 7A and data not shown). Ex vivo imaging of individual adult organs confirmed the conclusions on the living neonatal mice. As shown in Fig. 7B, eGFP fluorescence was detected only in the thymi of Tg7.1-1b.eGFP mice but not in other organs. In agreement with conclusions from the in vivo imaging, neither Tg1b.eGFP nor wild-type adult mice displayed detectable eGFP expression (Fig. 7B). These results demonstrated conclusively that sequences within TCE-7.1 direct exclusive T and NK cell-specific transcription of Gata3.

Fig. 7.

The TCE-7.1 enhancer is T cell specific. (A) eGFP expression in living P4 mice. Data are representative of multiple pups examined in two independent experiments. (B) eGFP expression in various organs from each genotype of adult mice. Three individual mice of each genotype were analyzed. B, brain; Li, liver; H, heart; K, kidney; Lu, lung; St, stomach; T, thymus; Sp, spleen. In both panels A and B, two lines of both Tg7.1-1b.eGFP and Tg1b.eGFP mouse were examined (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Here, we report that a 7.1-kbp DNA fragment (abbreviated TCE-7.1) located 280 kbp 3′ to the Gata3 gene contains cis information that is critical for the transcription of Gata3, both at multiple stages of T cell development and in thymic NK cells. While previous experiments have identified central roles for GATA-3 at multiple stages of T cell development (19, 36, 37, 54), it is expressed at all stages that have been examined, but its level clearly differs markedly between developmental stages (e.g., in CD4 versus CD8 SP cells or in Th1 versus Th2 cells) (17, 18, 52, 53). Although several trans-acting factors are believed to directly regulate Gata3 (1, 12, 31, 50, 51), a coherent mechanism explaining how this information is integrated to allow differential, stage-specific Gata3 expression at multiple stages of T cell development in vivo has not emerged.

The BAC-trap transgenic assay utilized in this report reiterated the generality of this assay, showing that even a very distant cis element, located more than 200 kbp from the structural gene (the amount of information usually borne in a BAC), can be identified, thus revealing the position of a cell-specific enhancer that is capable of conferring transcription to a reporter gene at several discrete developmental stages, from ETP to peripheral CD4+ T cells, in vivo. The expression pattern of the reporter was similar to that of endogenous Gata3 even though differences were documented. Since eGFP expression was not observed in the absence of the enhancer-bearing fragment, we conclude that this element is critical for transcription of the Gata3 gene in T lymphocytes.

In this study, both Tg43G17 and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP displayed expression profiles that reflected almost perfectly the endogenous Gata3 expression pattern in late stages of thymocyte development. At the DP stage, the TCRα locus begins to rearrange, and subsequently a low level of the TCRαβ complex is expressed. Those DP cells are poised for positive selection, although most of them fail to emerge intact from selection: only a few cells that have an appropriate TCR affinity are positively selected and finally emerge to differentiate into either CD4 SP or CD8 SP cells. Endogenous Gata3 is induced at the onset of positive selection, and its expression is controlled by TCR signaling (18, 34). Based on the remarkably similar expression patterns of endogenous Gata3, Tg43G17, and Tg7.1-1b.eGFP during late thymocyte development, we conclude that TCE-7.1 contains the activity required for development through those stages.

We found that TCE-7.1 harbors multiple putative transcription factor binding sites through bioinformatic analyses (data not shown). Perhaps not surprisingly, candidate binding sites for many transcription factors that are critical for T cell development can be identified in this region. For example, highly species-conserved sequences contain putative binding sites for transcription factors c-Myb, Runx, E2A, and TCF-1 as well as others. The proto-oncogene c-Myb is required for the induction of Gata3 following TCR signaling, and the binding of c-Myb to the Gata3-1b promoter is detectable in thymocytes (31). It is important to remember that this same Myb binding site is present in the B125 YAC, and that the YAC-derived transgene was not expressed in thymocytes. Moreover, this binding site was absent in all of the BAC and 7.1-1b.eGFP reporter constructs examined in this report, but nonetheless the reporter gene was induced in the T cells of both Tg7.1-1b.eGFP and Tg43G17 mice. Since the fragment bearing the T cell enhancer activity contains several putative c-Myb binding sites, it is possible that these enhancer sites participate in Gata3 induction by c-Myb.

Although expression in both the Tg7.1-1b.eGFP and Tg43G17 mice resembled that of endogenous Gata3, whether this element or group of elements constitute a bona fide cis element for Gata3 has not been conclusively demonstrated. Only two spliced ESTs other than Gata3 are located within 300 kbp of TCE-7.1. Those two ESTs, AK080422 and AK035738, have been identified as nonprotein-coding mRNAs (35). AK080422 was detected in a mouse neonatal cerebellum cDNA library, while AK035738 was observed in an adult male mouse urinary bladder cDNA library. The function of those two ESTs is unknown, and their expression in thymocytes has not been detected. Taken together, assigning TCE-7.1 activity to the Gata3 gene is likely the most conservative interpretation of these data.

Numerous interesting questions emerge from this study: does a single element within TCE-7.1 control Gata3 expression in αβT, γδT, and NK cells, or alternatively do multiple elements within TCE-7.1 each regulate transcription in those distinct lineages? Do multiple elements, perhaps in different combinations, consort to elicit proper stage-specific Gata3 activation during T cell development, or do different cofactors, all acting on a single cis element within TCE-7.1, function at different stages to confer the specificity? Answers to these fascinating questions should be resolved soon by the many groups studying Gata3 function in T cell transcription.

Finally, the data predict that (one or multiple) sequences within TCE-7.1 must collaborate with as-yet-undiscovered cis elements lying beyond the TCE-7.1 boundaries to fully recapitulate proper Gata3 expression in T lymphocytes. TCE-7.1 clearly contains sequences that are important for directing transcription in both the T cell and NK cell lineages. Further analysis of Gata3 gene regulation in T cells should help us to not only understand the complex mechanisms of gene regulation that are used to confer T cell specificity to this regulatory network but perhaps might also shed light on the mechanisms where GATA-3 may play an oncogenic role in leukemia and lymphoma (34, 45, 48).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Sartor for advice in the bioinformatics analysis, I. Maillard for advice and critical reading of the manuscript, and W. Filipiak, M. Van Keuren, and the Transgenic Animal Model Core of the University of Michigan's Biomedical Research Core Facilities for the generation of some of these transgenic mice.

Core support was provided by the University of Michigan Cancer Center and the Center for Organogenesis. Initial support for this project was provided by the NIH (GM28896). None of the authors have competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amsen D., et al. 2007. Direct regulation of Gata3 expression determines the T helper differentiation potential of Notch. Immunity 27:89–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reference deleted.

- 3. Anderson M. K., et al. 2002. Definition of regulatory network elements for T cell development by perturbation analysis with PU.1 and GATA-3. Dev. Biol. 246:103–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asnagli H., Afkarian M., Murphy K. M. 2002. Cutting edge: identification of an alternative GATA-3 promoter directing tissue-specific gene expression in mouse and human. J. Immunol. 168:4268–4271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asselin-Labat M.-L., et al. 2007. Gata-3 is an essential regulator of mammary-gland morphogenesis and luminal-cell differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyle A. P., et al. 2008. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell 132:311–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen D., Zhang G. 2001. Enforced expression of the GATA-3 transcription factor affects cell fate decisions in hematopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 29:971–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crawford G. E., et al. 2006. DNase-chip: a high-resolution method to identify DNase I hypersensitive sites using tiled microarrays. Nat. Methods 3:503–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crawford G. E., et al. 2004. Identifying gene regulatory elements by genome-wide recovery of DNase hypersensitive sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:992–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crawford G. E., et al. 2006. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 16:123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. David-Fung E.-S., et al. 2006. Progression of regulatory gene expression states in fetal and adult pro-T-cell development. Immunol. Rev. 209:212–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fang T. C., et al. 2007. Notch directly regulates Gata3 expression during T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity 27:100–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fiering S. N., et al. 1991. Improved FACS-Gal: flow cytometric analysis and sorting of viable eukaryotic cells expressing reporter gene constructs. Cytometry 12:291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. George K. M., et al. 1994. Embryonic expression and cloning of the murine GATA-3 gene. Development 120:2673–2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grigorieva I. V., et al. 2010. Gata3-deficient mice develop parathyroid abnormalities due to dysregulation of the parathyroid-specific transcription factor Gcm2. J. Clin. Invest. 120:2144–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hasegawa S. L., et al. 2007. Dosage-dependent rescue of definitive nephrogenesis by a distant Gata3 enhancer. Dev. Biol. 301:568–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hendriks R. W., et al. 1999. Expression of the transcription factor GATA-3 is required for the development of the earliest T cell progenitors and correlates with stages of cellular proliferation in the thymus. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1912–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hernández-Hoyos G., Anderson M. K., Wang C., Rothenberg E. V., Alberola-Ila J. 2003. GATA-3 expression is controlled by TCR signals and regulates CD4/CD8 differentiation. Immunity 19:83–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosoya T., et al. 2009. GATA-3 is required for early T lineage progenitor development. J. Exp. Med. 206:2987–3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hosoya T., Maillard I., Engel J. D. 2010. From the cradle to the grave: activities of GATA-3 throughout T-cell development and differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 238:110–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaufman C. K., et al. 2003. GATA-3: an unexpected regulator of cell lineage determination in skin. Genes Dev. 17:2108–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khandekar M., Suzuki N., Lewton J., Yamamoto M., Engel J. D. 2004. Multiple, distant Gata2 enhancers specify temporally and tissue-specific patterning in the developing urogenital system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10263–10276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ko L. J., et al. 1991. Murine and human T-lymphocyte GATA-3 factors mediate transcription through a cis-regulatory element within the human T-cell receptor delta gene enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:2778–2784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kouros-Mehr H., Slorach E. M., Sternlicht M. D., Werb Z. 2006. GATA-3 maintains the differentiation of the luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Cell 127:1041–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kurek D., Garinis G. A., van Doorninck J. H., van der Wees J., Grosveld F. G. 2007. Transcriptome and phenotypic analysis reveals Gata3-dependent signalling pathways in murine hair follicles. Development 134:261–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lakshmanan G., Lieuw K. H., Grosveld F., Engel J. D. 1998. Partial rescue of GATA-3 by yeast artificial chromosome transgenes. Dev. Biol. 204:451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lakshmanan G., et al. 1999. Localization of distant urogenital system-, central nervous system-, and endocardium-specific transcriptional regulatory elements in the GATA-3 locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1558–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee E. C., et al. 2001. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics 73:56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lieuw K. H., Li G., Zhou Y., Grosveld F., Engel J. D. 1997. Temporal and spatial control of murine GATA-3 transcription by promoter-proximal regulatory elements. Dev. Biol. 188:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lim K. C., et al. 2000. Gata3 loss leads to embryonic lethality due to noradrenaline deficiency of the sympathetic nervous system. Nat. Genet. 25:209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maurice D., Hooper J., Lang G., Weston K. 2007. c-Myb regulates lineage choice in developing thymocytes via its target gene Gata3. EMBO J. 26:3629–3640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moriguchi T., et al. 2006. Gata3 participates in a complex transcriptional feedback network to regulate sympathoadrenal differentiation. Development 133:3871–3881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nawijn M. C., et al. 2001. Enforced expression of Gata-3 in transgenic mice inhibits Th1 differentiation and induces the formation of a T1/ST2-expressing Th2-committed T cell compartment in vivo. J. Immunol. 167:724–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nawijn M. C., et al. 2001. Enforced expression of GATA-3 during T cell development inhibits maturation of CD8 single-positive cells and induces thymic lymphoma in transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 167:715–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okazaki Y., et al. 2002. Analysis of the mouse transcriptome based on functional annotation of 60,770 full-length cDNAs. Nature 420:563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pai S.-Y., Truitt M. L., Ho I.-C. 2004. GATA-3 deficiency abrogates the development and maintenance of T helper type 2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:1993–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pai S.-Y., et al. 2003. Critical roles for transcription factor GATA-3 in thymocyte development. Immunity 19:863–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sambandam A., et al. 2005. Notch signaling controls the generation and differentiation of early T lineage progenitors. Nat. Immunol. 6:663–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Samson S. I., et al. 2003. GATA-3 promotes maturation, IFN-gamma production, and liver-specific homing of NK cells. Immunity 19:701–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taghon T., et al. 2001. Enforced expression of GATA-3 severely reduces human thymic cellularity. J. Immunol. 167:4468–4475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taghon T., Yui M. A., Rothenberg E. V. 2007. Mast cell lineage diversion of T lineage precursors by the essential T cell transcription factor GATA-3. Nat. Immunol. 8:845–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taylor J., et al. 2006. ESPERR: learning strong and weak signals in genomic sequence alignments to identify functional elements. Genome Res. 16:1596–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tsarovina K., et al. 2010. The Gata3 transcription factor is required for the survival of embryonic and adult sympathetic neurons. J. Neurosci. 30:10833–10843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tydell C. C., et al. 2007. Molecular dissection of prethymic progenitor entry into the T lymphocyte developmental pathway. J. Immunol. 179:421–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van Hamburg J. P., et al. 2008. Cooperation of Gata3, c-Myc and Notch in malignant transformation of double positive thymocytes. Mol. Immunol. 45:3085–3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vosshenrich C. A., et al. 2006. A thymic pathway of mouse natural killer cell development characterized by expression of GATA-3 and CD127. Nat. Immunol. 7:1217–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xi H., et al. 2007. Identification and characterization of cell type-specific and ubiquitous chromatin regulatory structures in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 3:e136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu W., Kee B. L. 2007. Growth factor independent 1b (Gfi1b) is an E2A target gene that modulates Gata3 in T-cell lymphomas. Blood 109:4406–4414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yamamoto M., et al. 1990. Activity and tissue-specific expression of the transcription factor NF-E1 multigene family. Genes Dev. 4:1650–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang X. O., et al. 2009. Requirement for the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Dec2 in initial Th2 lineage commitment. Nat. Immunol. 10:1260–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu Q., et al. 2009. T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-gamma. Nat. Immunol. 10:992–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang D. H., Cohn L., Ray P., Bottomly K., Ray A. 1997. Transcription factor GATA-3 is differentially expressed in murine Th1 and Th2 cells and controls Th2-specific expression of the interleukin-5 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272:21597–21603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zheng W., Flavell R. A. 1997. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell 89:587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhu J., et al. 2004. Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in T(H)1-T(H)2 responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:1157–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]