Abstract

Spirochetes have a unique cell structure: These bacteria have internal periplasmic flagella subterminally attached at each cell end. How spirochetes coordinate the rotation of the periplasmic flagella for chemotaxis is poorly understood. In other bacteria, modulation of flagellar rotation is essential for chemotaxis, and phosphorylation-dephosphorylation of the response regulator CheY plays a key role in regulating this rotary motion. The genome of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi contains multiple homologues of chemotaxis genes, including three copies of cheY, referred to as cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3. To investigate the function of these genes, we targeted them separately or in combination by allelic exchange mutagenesis. Whereas wild-type cells ran, paused (flexed), and reversed, cells of all single, double, and triple mutants that contained an inactivated cheY3 gene constantly ran. Capillary tube chemotaxis assays indicated that only those strains with a mutation in cheY3 were deficient in chemotaxis, and cheY3 complementation restored chemotactic ability. In vitro phosphorylation assays indicated that CheY3 was more efficiently phosphorylated by CheA2 than by CheA1, and the CheY3-P intermediate generated was considerably more stable than the CheY-P proteins found in most other bacteria. The results point toward CheY3 being the key response regulator essential for chemotaxis in B. burgdorferi. In addition, the stability of CheY3-P may be critical for coordination of the rotation of the periplasmic flagella.

INTRODUCTION

Spirochetes are a group of motile bacteria that have a unique morphology and means of motility. On the surface of the spirochete is an outer membrane, which is often referred to as the outer membrane sheath. Within this outer membrane are the cell cylinder and the periplasmic flagella. The periplasmic flagella reside between the outer membrane and the cell cylinder. Because of its medical importance and recent advances in genetic manipulation, we have focused on the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi to analyze spirochete motility and chemotaxis (for recent reviews, see references 10, 26, 34, and 68). This spirochete is relatively long (10 to 20 μm) and thin (0.31 μm) and has a flat-wave morphology, and motility is generated by rotation of the periplasmic flagella (11, 14, 24, 25, 33, 42). Approximately 7 to 11 periplasmic flagella are subterminally attached at each cell end (30), and recent electron cryotomography analysis indicates that these periplasmic flagella form elegant ribbons that wrap clockwise (CW) around the cell cylinder (11). Not only are the periplasmic flagella involved in motility, but these organelles have a skeletal function that in part dictates the flat-wave shape of the cell (10, 14, 26, 35, 40, 53, 68). Thus, mutants that lack periplasmic flagella are nonmotile and have a rod-shaped morphology (35, 40, 53). Motility is accomplished by backward-moving flat waves along the cell body. These waves are generated by the coordinated rotation of the rigid periplasmic flagella as they exert force on the relatively flexible cell cylinder (10, 11, 14, 26, 33).

The motile behavior of B. burgdorferi and other spirochetes is unique and complex (10, 26, 34). Tracking of B. burgdorferi swimming reveals three different swimming modes: run, flex, and reverse (1, 10, 25, 33, 42). Runs occur when the periplasmic flagellar motors at one end rotate in the direction opposite that of the motors at the other end. Thus, the periplasmic flagella of the anterior ribbon rotates counterclockwise (CCW) and those of the posterior end rotate CW (as a frame of reference, a periplasmic flagellum is viewed from its distal tip along the filament toward insertion into the motor) (10, 11, 14, 26, 33, 34). The flex is a nontranslational mode and is often associated with bending in the cell center with a distorted appearance (25, 42). The spirochete flex is thought to be equivalent to the Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium tumble (6, 10, 16, 26, 33, 34, 42). During the flex, the motors at both ends rotate in the same direction (10, 16, 26, 33, 34, 42); i.e., both rotate either CW or CCW. The final mode, cell reversal, occurs in translating cells when the motors at each end reverse their direction of rotation (10, 16, 33, 42). In B. burgdorferi, this reversal can last less than 300 ms (N. Charon, unpublished data).

Chemotaxis is defined as movement toward or away from a chemical stimulus. Bacteria undergo a biased random walk during chemotaxis, and this walk is achieved by modulating the direction of rotation of the flagella or, in some cases, the speed of flagellar rotation (50, 60). A two-component system mediates the direction or speed of flagellar rotation. In the paradigm chemotaxis model of E. coli and S. enterica, the response regulator phosphorylated CheY (CheY-P) shuttles between methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP) receptor signal complexes and flagellar motors. CheY is phosphorylated by the histidine protein kinase CheA, which forms part of the signal complexes, which are located preferentially at or near the cell poles (8, 39, 50, 60, 61, 63, 70, 72). CheY-P diffuses through the cytoplasm and interacts with the flagellar switch protein FliM, causing the motor rotational biases to shift from the default rotation of CCW to CW. Dephosphorylation of CheY-P, which restores the default CCW behavior, is dramatically enhanced by the action of the CheY-P-specific phosphatase CheZ (49, 73).

Chemotaxis in B. burgdorferi and other spirochetes is different from the well-studied paradigms of E. coli and S. enterica. For spirochetes to swim toward an attractant, the organisms must be able to coordinate the rotation of the motors at the two ends of the cell; these motors (32, 36) are located at a considerable distance from one another (often greater than 10 μm) (10, 33, 70). One of the long-standing questions related to spirochete chemotaxis is how the organisms are able to achieve this coordination (10, 16, 27, 33). To begin to understand this process, we have used allelic exchange mutagenesis to identify specific genes involved in chemotaxis. Genomic analysis indicates that B. burgdorferi is similar to the majority of bacteria in having multiple copies of chemotaxis genes (10, 18, 26, 39, 49, 69). For example, it has two cheA (cheA1 and cheA2), three cheW (cheW1, cheW2, and cheW3), and three cheY (cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3) genes. It does not have cheZ but instead possesses cheX, which is a CheY-P-specific phosphatase prevalent in several species of bacteria (42, 44, 46, 47). In addition, it has two homologs of the switch protein FliG rather than one (18, 35). We have shown that cheA2, but not cheA1, and cheX are involved in chemotaxis (33, 42). cheA2 mutants constantly run and fail to reverse or flex; thus, in the default state, the motors at each end of the cell rotate in opposite directions (33). In contrast, cheX mutants constantly flex and are also nonchemotactic (42). In this communication, we examine the roles of cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3 in chemotaxis by inactivating these genes separately or in combination. We found that only cheY3 is involved in chemotaxis. Furthermore, biochemical assays indicate that CheY3 is more efficiently phosphorylated by CheA2 than by CheA1. Finally, CheY3 is unique compared to most other bacterial chemotaxis proteins, as it forms a relatively stable, long-lived CheY3-P intermediate in the absence of CheX phosphatase. The results point toward CheY3 being the key response regulator for chemotaxis, and the stability of CheY3-P may be critical for coordinating the rotation of the periplasmic flagellar motors located at both cell ends.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

High-passage, avirulent B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31A and nonmotile flaB mutant strain MC-1 have been described previously (7, 40). Cells were grown in BSK-II medium at 34°C in a 2.5% CO2 humidified incubator (41).

Construction of cheY mutants.

Inactivation of cheY1 (gene locus bb0551; gene length, 381 bp), cheY2 (bb0570; gene length, 375 bp), and cheY3 (bb0672; gene length, 441 bp) was achieved essentially as described previously (33, 40–42). Briefly, cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3 plus flanking DNA were, respectively, amplified by PCR with the following primers (5′-3′): for cheY1, CheY1-F (ATTTGCAGTTGTTTTATGAC) and CheY1-R (GCAAATCAAGATCATAAACC); for cheY2, CheY2-F (TCTGCTAGGTTTCAAAATAT) and CheY2-R (TGGACTTACCCTTTACATAG); and for cheY3, CheY3-F (GGGGAGCTGATTGTTTGGAAG) and CheY3-R (ACAGTCCCAGTGAATATAGAG). The PCR products were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Inc.), yielding pCheY1-Easy, pCheY2-Easy, and pCheY3-Easy, respectively. Antibiotic resistance cassettes were similarly amplified by PCR with restriction sites at both ends (see below). The cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3 genes were inactivated by inserting erythromycin (ermC), synthesized modified coumermycin A1 (gyrB), and kanamycin (PflgB-kan; aphI) resistance cassettes, respectively (7, 15, 33, 40, 52, 55). The cheY1 inactivation plasmid was constructed by inserting an ermC cassette into the HindIII site (18 bp downstream from the cheY1 translation start site). Inactivation plasmids for cheY2 and cheY3 were constructed with gyrB and aphI cassettes, respectively, and inserted at the unique EcoRV sites within cheY2 (177 bp downstream from the translation start site) and cheY3 (317 bp downstream from the translation start site). Linear, PCR-amplified DNA containing cheY1-ermC, cheY2-gyrB, or cheY3-aphI was electroporated separately into competent B31A cells to obtain individual single mutants (7, 41). Transformants were selected with 0.06 μg/ml erythromycin (for cheY1::ermC), 2.5 μg/ml coumermycin A1 (cheY2::gyrB), and 350 μg/ml kanamycin (cheY3::aphI). The cheY1 and cheY2 genes were also inactivated using the aphI cassette as described above. Double mutants were constructed by electroporating linear DNA containing one inactivated cheY gene into cells containing a different cheY mutation. A cheY1::ermC cheY2::gyrB cheY3::aphI triple mutant was obtained in a similar manner by introducing cheY2-gyrB DNA into a cheY1 cheY3 double mutant, and colonies were selected on plates containing erythromycin, coumermycin A1, and kanamycin.

Construction of complementation vehicle.

The previously described shuttle vector pKSSF1, which carries the streptomycin cassette, was used to complement the cheY3::aphI mutant (17). The B. burgdorferi flgB promoter (7, 23) and cheY3 gene sequences were amplified with primers containing HindIII and NdeI restriction enzyme sites (5′-3′ and 3′-5′, respectively) and inserted into the NdeI site (the 3′ end of the promoter fragment and the 5′ end of the cheY3 gene) to yield pFlgBCheY3. The primers used were as follows (5′-3′): for flgB, FlgB-Hind (AAGCTTTAATACCCGAGCTTCAAG) and FlgB-Nde (CATATGGAAACCTCCCTCAT); for cheY3, CheY3-Nde (CATATGATTCAAAAGACTAC) and CheY3-Hind (AAGCTTTAACAAATACAGACATTAC). Underlined sequences indicate restriction sites. The flgB cheY3 DNA was then ligated into the HindIII site of pKSSF1 to yield pCheY3.com. Approximately 10 μg of purified pCheY3.com plasmid was used to transform competent cheY3:: aphI mutant cells by electroporation as described above. Transformants were selected with 350 μg/ml kanamycin plus 100 μg/ml streptomycin. To confirm that the plasmid was complementing in trans, the pCheY3.com shuttle vector was rescued from complemented cheY3+ cells, transformed, and then purified from E. coli and the integrity of the flgB-cheY3 construct was verified by restriction digestion.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and RNA ligase-mediated (RLM) rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE).

To determine the operon structure and promoter in genes contained in the cheY1 cluster, exponentially growing cells (2 × 107/ml) were treated with RNAprotect bacterial reagent and then total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc.). Contaminating DNA in the RNA samples was removed by RNase-free Turbo DNase I (Ambion Inc.) digestion for 3 h at 37°C, followed by RNeasy mini purification. For RT-PCR, cDNA was prepared from purified RNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen Inc.). RT-PCR primer sequences are not shown but can be obtained upon request. To determine the transcription start site (TSS) of the cheY1 operon, 5′ RLM-RACE was performed using 2 μg purified total RNA and the cheY1 gene-specific primer 5′-CTTGGGCTTCTAAAAATTCT-3′ according to the manufacturer's protocol (Ambion Inc.). RLM-RACE PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Inc.); this was followed by DNA sequencing. As a positive control, we determined the TSS of the monocistronically transcribed flaB gene operon previously reported (22) using a flaB-specific primer (5′-CTTCATTTAAATTCCCTTCTGTT-3′).

Protein preparation and antibody production.

Recombinant CheY1, CheY2, CheY3, CheA1, and CheA2 proteins (rCheY1, rCheY2, rCheY3, rCheA1, and rCheA2, respectively) were synthesized by PCR amplification of the sequences of the genes that encode them, without the translation initiation ATG/TTG codon. Amplified DNA fragments of cheY1 and cheY2 were ligated into the pQE30 expression vector (Qiagen Inc.) using restriction sites SphI and KpnI. PCR-amplified cheY3 DNA was inserted into the pQE30 expression vector restricted with BamHI and HindIII. PCR primers (5′-3′) were as follows: for CheY1, RY1-F (GCATGCGATAAAAGGAGTGCTAGT) and RY1-R (GGTACCCTAATCCAAAAGTTTAAT); for CheY2, RY2-F (GCATGCAAAAAAAGAATTTTGGTT) and RY2-R (GGTACCTTAAAATATCTTTGAGAT); for CheY3, RY3-F (GGATCCATTCAAAAGACTACAATTGC) and RY3-R (AAGCTTTTTAACAAATACAGACATTAC). Vectors containing cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3 were transformed into an E. coli expression strain containing M15 (pREP4) (Qiagen Inc.) and overexpressed using 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Proteins were affinity purified according to the manufacturer's protocol and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline. Amino-terminally His-tagged CheA1 and CheA2 were prepared using similar procedures and are described elsewhere (33, 41, 42). Rats (for CheY3) and rabbits (for CheY1 and CheY2) were immunized with 200 to 400 μg of dialyzed protein to raise specific antiserum using standard methods (Alpha Diagnostic International Inc.).

Gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection method (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia) were carried out as previously reported (21). The protein concentration in the cell lysates was determined with a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Unless noted otherwise, 10 μg of lysates was loaded into each lane of an SDS-PAGE gel and subjected to immunoblotting using specific antibodies. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies that were kindly provided by other investigators included the following: anti-FlaB (H9724) by A. G. Barbour (University of California, Irvine, CA), anti-FlaA by B. Johnson (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA), anti-DnaK by J. Benach (SUNY, Stony Brook, NY), and polyclonal anti-CheA by P. Matsumura (University of Illinois, Chicago, IL). The specific reactivities of those antibodies to B. burgdorferi FlaB, FlaA, DnaK, and CheA2, respectively, have been reported previously (1, 13, 33, 40, 43). The intensity of the CheY3 protein bands in wild-type and complemented cheY3+ was measured using Alpha View spot densitometry (Version 3.0.2.0; Alpha Innotech Corporations).

Capillary tube chemotaxis assays.

Capillary tube chemotaxis assays were performed as previously described (1, 33, 41, 42), and flow cytometry to quantify cells was carried out as previously reported (1, 41). A positive chemotactic response was defined as at least twice as many cells entering the attractant-filled tubes as the buffer-filled tubes (1).

Microscopy and computer-assisted motion analysis.

B. burgdorferi cells were observed using dark-field microscopy (Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope; Carl Zeiss Inc.) (1, 41). Cells were centrifuged at 2,500 × g and resuspended in a motility buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 1% methylcellulose (400 mesh; Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Cells were tracked on a temperature-controlled stage (34°C) using Volocity (Perkin-Elmer) (1, 41). For each strain, at least 10 individual cells were recorded for up to 1 min. Because the cheY3 mutant cells constantly ran, they exited the microscopic field within several seconds, precluding 1-min recording periods. Results are expressed as the total distance the center of each cell traveled/number of seconds the cell was tracked. The resulting velocity (μm/s) is a minimal velocity, as cells do not translate during flexes. Cell reversal frequency (number of reversals per minute) was also determined; reversals in direction were often accompanied by an intervening flex of less than 0.5 s. For convenience, a prolonged flex interval is defined as lasting 0.5 to 2 s with the cell stopped and having a twisted morphology.

Phosphorylation assays.

Phosphorylation of B. burgdorferi CheA1 and CheA2 (6×His-tagged rCheA1 and rCheA2) and phosphate transfer to rCheY3 were carried out as previously described (41, 42). [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from MB Biomedicals. Micro Bio-Spin6 columns were obtained from Bio-Rad; all other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. rCheA1 and rCheA2 (2 μM) were incubated in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.5)–50 mM KCl,–5 mM MgCl2–0.3 mM ATP–1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol)/μl for 30 min. Reactions were initiated by the addition of ATP plus [γ-32P]ATP. Autophosphorylated rCheA reaction mixtures were applied to Bio-Spin6 columns according to the manufacturer's instructions to remove unincorporated [32P]ATP. To measure phosphotransfer from rCheA-P to CheY, 2 μM 32P-labeled rCheA was incubated with 14.8 μM rCheY3 for the indicated times at 25°C, reactions were stopped by the addition of 4× stop buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.4 M dithiothreitol, 8% SDS, 0.4% bromophenol blue, 40% glycerol, 20% 2-mercaptoethanol), and reaction products were electrophoresed on 15% SDS polyacrylamide gels. Dried gels were exposed to a phosphorimaging screen (usually for 1 h) and analyzed with a Molecular Dynamics Storm 820; the intensity of phosphorylated proteins was calculated using ImageQuant v2003.02 software and is expressed as relative “volume.”

RESULTS

Functional residues of chemotaxis response regulators are conserved in CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3.

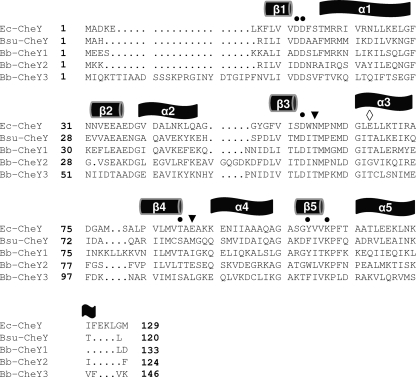

To initially investigate the extent to which the three putative B. burgdorferi CheY proteins might be functional, the deduced amino acid sequences of B. burgdorferi CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3 were aligned and compared with those of E. coli and Bacillus subtilis CheY (Fig. 1). B. burgdorferi CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3 share 32%, 38%, and 25% amino acid sequence identity with E. coli CheY, respectively. B. burgdorferi CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3 share 41%, 33%, and 47% sequence identity with B. subtilis CheY; thus, based on sequence identity, B. burgdorferi CheY2 is more similar to CheY of E. coli and CheY1 and CheY3 are more similar to CheY of B. subtilis. As pointed out below, an analysis of specific key residues in each of the three CheY proteins supports this proposition. All of the functional residues of a CheY response regulator were found to be conserved in CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3, suggesting that they all are potential chemotaxis response regulators (57, 67) (Fig. 1, circles). For example, E. coli CheY and B. burgdorferi CheY proteins have a (βα)5 “Rossman fold” where E. coli residues D12 and D13 are located on the loop connecting β1 with α1, β3 ends with D57, β4 ends at T/S87, and β5 ends at K109 (Fig. 1) (57, 67). In addition, the aromatic residue Y106 of E. coli that rotates upon phosphorylation is conserved in CheY1 (circle). The nonconserved active-site residues of E. coli CheY, N59 and E89, which participate in CheY autodephosphorylation (57, 58), are conserved in B. burgdorferi CheY2 but not in CheY1 or CheY3 (Fig. 1, arrowheads). E89 is also involved in CheZ dephosphorylation in E. coli CheY (57, 58, 73). However, as determined by the analysis of the B. burgdorferi cocrystal CheY3-CheX, amino acid residue T81 of CheY3 (Fig. 1, diamond) participates in the CheX-mediated dephosphorylation of CheY3-P (47). T81 is also conserved in B. burgdorferi CheY1 and B. subtilis CheY but not in E. coli CheY or B. burgdorferi CheY2. These results are consistent with the known dephosphorylation activity of CheX on B. burgdorferi CheY3-P and that of the CheX homolog CheC on B. subtilis CheY-P (42, 44, 47).

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignments of B. burgdorferi CheY proteins with E. coli and B. subtilis CheY using T-Coffee (45). Conserved residues that are essential for function in E. coli are indicated by solid circles. The nonconserved active-site residues of E. coli CheY, N59 and E89, that are conserved in B. burgdorferi CheY2, but not in CheY1 or CheY3, are identified by arrowheads. T81 of CheY3, which is involved in CheX dephosphorylation of CheY3-P and is also conserved in B. burgdorferi CheY1 and in B. subtilis CheY, is identified by a diamond. Secondary structure elements as determined for E. coli CheY and predicted for B. burgdorferi CheY proteins are shown above the sequence alignment. The E. coli and B. subtilis CheY proteins are identified as Ec-CheY and Bsu-CheY, respectively. Amino acid residue numbers are indicated on the left. The last amino acid residue number of each CheY sequence is shown on the right.

Transcription of cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3.

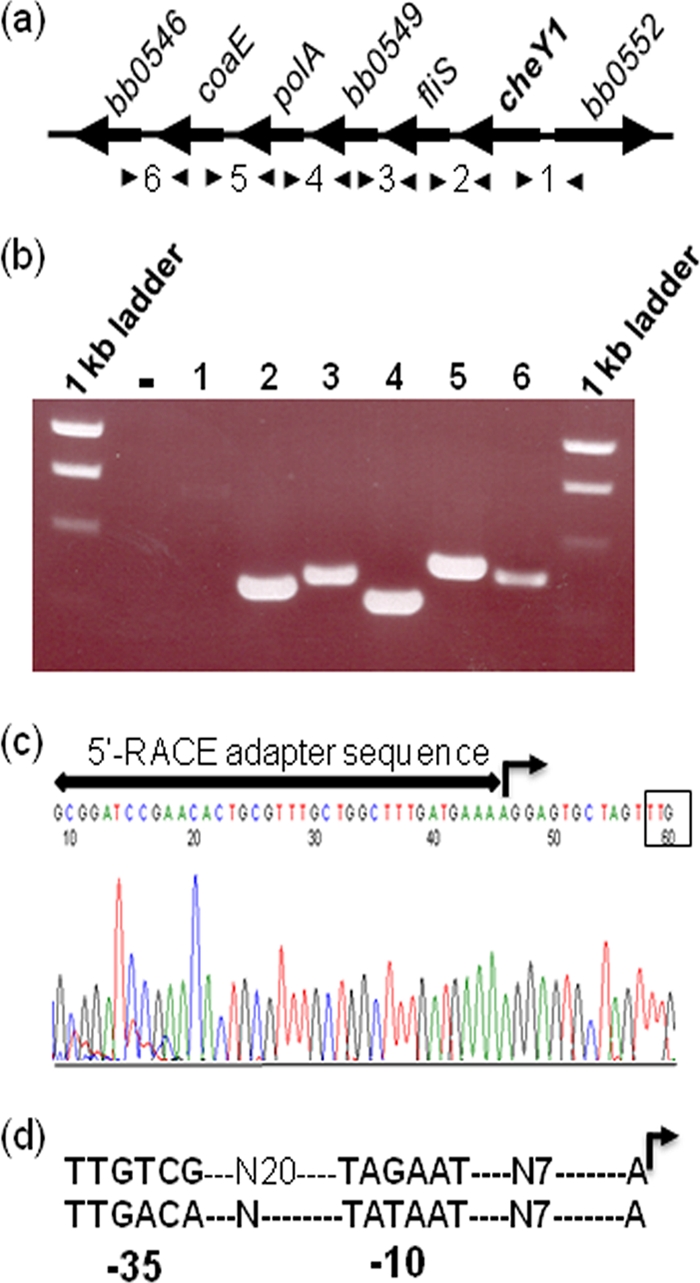

The three B. burgdorferi chromosomal cheY genes are located in different operons, and two of the three cheY genes (cheY2 and cheY3) map at the distal end of the operons (18, 19, 33). The operon structures housing CheY2 (cheW2 operon) and CheY3 (flaA operon) have been characterized. The cheY2 operon, consisting of cheW2, orf566, cheA1, cheB2, orfO569, and cheY2, was shown to be initiated by a σ70 promoter (33). The operon that contains cheY3 was shown to be initiated by either of two σ70 promoters, one upstream of flaA (flaA, cheA2, cheW3, cheX, and cheY3) and the other upstream of ami (ami, bb0665, bb0666, bb0667, flaA, cheA2, cheW3, cheX, and cheY3) (20, 65, 71). The gene cluster housing cheY1 consists of cheY1, fliS (formerly flaJ), bb0549, polA, coaE, and bb0546, but whether these genes are coordinately transcribed has not been reported. RT-PCR indicated that these genes are transcribed as a polycistronic mRNA (Fig. 2a and b, lanes 2 to 6). The region between cheY1 and gene bb0552 failed to be amplified, which is consistent with bb0552 being divergently transcribed and not part of the cheY1 operon (Fig. 2b, lane 1).

Fig. 2.

cheY1 (bb0551) operon structure. (a) Schematic representation of the cheY1 operon. Arrowheads indicate specific primer pairs that amplify regions between genes. (b) Agarose gel showing the RT-PCR products. The number above each lane represents a number between arrowheads in panel a. Lane 1 did not amplify a product, as cheY1 and bb0552 are divergently transcribed. A no-RT control reaction is represented by a minus sign. (c) DNA sequencing chromatogram of an RLM-RACE analysis that resulted in the identification of the TSS of the cheY1 operon (right-angled arrow). The cheY1 translation start TTG codon is boxed. A horizontal line with arrowheads represents the 5′ RACE adapter sequence (provided in the kit). (d) Predicted −35 and −10 promoter sequences with the TSS (right-angled arrow) of cheY1 operon (top) and a typical σ70 promoter sequence (bottom) are shown (28).

To determine if expression of the cheY1 operon is also mediated by a σ70 promoter, the TSS of the cheY1 operon was determined using RLM-RACE. A TSS with a predicted σ70-like promoter directly upstream of cheY1 was identified (TTGTCG-N20-TAGAAT-N7-A) (Fig. 2c and d). To validate the RACE result, we determined the TSS of the flaB (bb0147) gene as a control, as the TSS of the flaB monocistronic operon has previously been determined using primer extension assays (22). Our RACE analysis produced the expected results (TTCTTT-N17-TATTCT-N7-A) (not shown; see reference 22). Thus, the cheY1 operon, like the operons that contain cheY2 or cheY3, is initiated by a σ70-like promoter and is polycistronically transcribed.

Western blot analysis of single, double, and triple cheY mutants and the complemented cheY3 mutant.

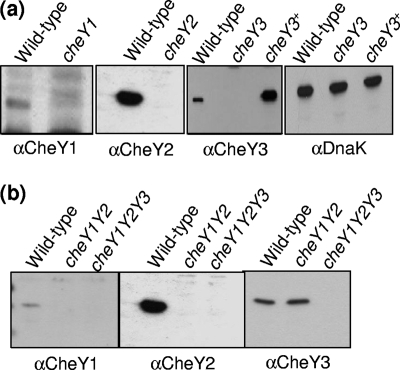

The response regulator CheY plays a key role in the chemotactic signaling in bacteria. Western blot analysis was used to determine if all three CheY proteins were expressed in B. burgdorferi and to determine the extent to which these CheY proteins participate in chemotaxis. cheY1, cheY2, and cheY3 were inactivated singly or in combination using targeted mutagenesis with different antibiotic resistance cassettes as described in Materials and Methods. PCR results of specific clones verified that the antibiotic resistance cassettes were appropriately inserted into the cheY1 (cheY1::ermC), cheY2 (cheY2::gyrB), and cheY3 (cheY3::aph1) genes, as expected (not shown). Western blot analyses indicated that CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3 were expressed in wild-type cells but not in the corresponding mutant cells (Fig. 3a), and as expected, the masses of the reactive proteins varied from 11 to 14 kDa. trans complementation of cheY3 (cheY3+) restored CheY3 synthesis, albeit at a higher level (3.5 times by densitometry) than in the wild-type cells (Fig. 3a). We also constructed all combinations of cheY double mutants (cheY1 cheY3, cheY2 cheY3, and cheY1 cheY2) and the triple cheY mutant (cheY1 cheY2 cheY3) (Fig. 3b and not shown). Western blot analysis indicated that, as with the single mutants, the appropriate cheY genes were specifically inactivated (Fig. 3b). For example, in the cheY1 cheY2 double mutant, the expression of CheY1 and CheY2 was abolished without affecting the expression of CheY3 (Fig. 3b, lanes cheY1Y2). As expected, Western blot analysis also demonstrated that none of the CheY proteins were expressed in the triple cheY (cheY1 cheY2 cheY3) mutant (Fig. 3b, lanes cheY1Y2Y3).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analyses of CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3 in wild-type and cheY mutant B. burgdorferi cells. Approximately 10 μg protein of cell lysates from the wild-type strain and the indicated cheY mutant strains was subjected to Western blotting and probed with antibodies specific to the CheY proteins (αCheY1, αCheY2, and αCheY3). Samples containing 3 μg lysates were used for the loading control (αDnaK, panel a, rightmost). The approximate molecular masses of CheY1 (11 kDa), CheY2 (10 kDa), CheY3 (14 kDa), and DnaK (72 kDa) were determined based on the masses of marker proteins (not shown). In panel a, lysates from wild-type; cheY1, cheY2, or cheY3 single mutant; and complemented cheY3+ B. burgdorferi cells were probed with the indicated CheY antisera. In panel b, lysates from wild-type, cheY1 cheY2 double mutant (cheY1Y2), and cheY1 cheY2 cheY3 triple mutant B. burgdorferi cells (cheY1Y2Y3) were probed with CheY1, CheY2, and CheY3 antisera.

Chemotactic behavior of single cheY mutants.

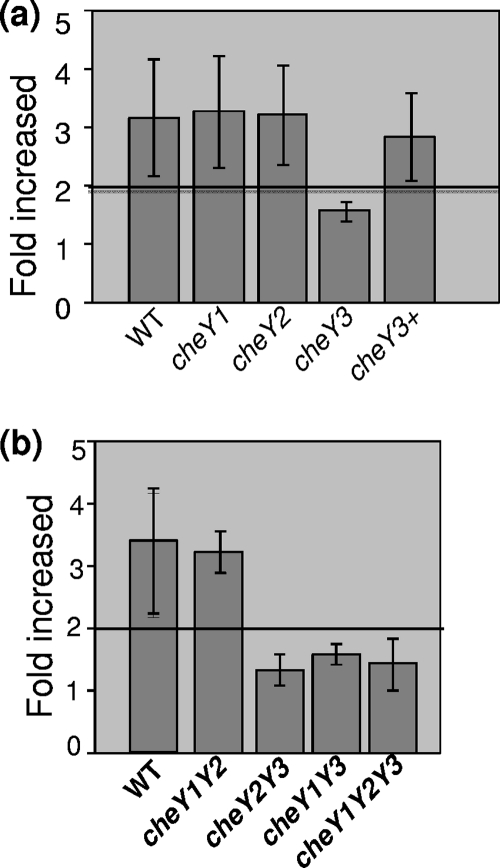

In other species that have multiple cheY homologs, often only one participates in chemotaxis. However, in some species, more than one cheY homolog is necessary for full chemotaxis (31, 49–51, 59, 62). Accordingly, we tested if the three cheY genes functioned in chemotaxis using capillary tube assays (Fig. 4). We found that the cheY1 and cheY2 mutants had a chemotactic response indistinguishable from that of the wild type. In contrast, the cheY3 mutant failed to significantly respond to the attractant, but complementation restored chemotaxis to a level equivalent to that of the wild type (Fig. 4a). Thus, these results indicate that cheY3, but not cheY1 or cheY2, is involved in chemotaxis. In addition, the lack of a detectable defect on the chemotaxis phenotype in cheY1 and cheY2 mutants was not due to the use of the ermC and gyrB cassettes, as identical results were obtained when each was inactivated with the aphI cassette (not shown).

Fig. 4.

Chemotaxis assays of cheY mutants. (a and b) Capillary tube chemotaxis assays coupled with flow cytometry were performed with wild-type (WT) and mutant strains. The results are expressed as n-fold increases in the number of cells entering capillary tubes containing glucosamine attractant relative to the number of cells entering tubes containing a no-attractant control (buffer alone). A 2-fold increase (horizontal line) compared to the buffer control is considered significant (1). Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error from three independent experiments.

Chemotactic behavior of double and triple cheY mutants.

The results in Fig. 1 and 3 indicate that all three CheY proteins have the necessary domains for chemotaxis and are expressed in wild-type cells. We next asked whether CheY3, in combination with either CheY1 or CheY2, was essential for chemotaxis. Conceivably, CheY1 and CheY2 could overlap in function to augment chemotaxis mediated by CheY3 in a manner analogous to CheY3 or CheY4 promoting CheY6-mediated chemotaxis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides (49–51). To test this possibility, we constructed a cheY1 cheY2 double mutant and measured its ability to undergo chemotaxis. Capillary tube chemotaxis assays indicated that the cheY1 cheY2 double mutant had no detectable alteration in its chemotactic response (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the cheY1 cheY3 and cheY2 cheY3 double mutants, as well as the cheY1 cheY2 cheY3 triple mutant, were deficient in chemotaxis (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these results indicate that cheY1 and cheY2 are not essential for chemotaxis and that cheY3 is the sole response regulator required for B. burgdorferi chemotaxis under our assay conditions.

Swimming behavior of the cheY mutants.

One possible explanation for the above results is that the cheY3 mutation resulted in a defect in motility and not in chemotaxis, as found in some species of bacteria. For example, in Rhodospirillum centenum, cheY3 mutants fail to synthesize flagella and are nonmotile (2). To test for this possibility, we analyzed individual cells using a computer-assisted cell tracker coupled with video microscopy. Because the periplasmic flagella influence cell shape (10, 14, 26, 35, 40, 53), we first analyzed cell structure by dark-field microscopy. We found that the morphology of the mutants was indistinguishable from that of the wild type (not shown). Furthermore, the swimming velocity of each of the cheY mutants, including those containing the cheY3 mutation, was similar to that of the wild type (Table 1). The velocities ranged from 8 to 11 μm/s. These results indicate that the cheY3 mutation did not result in a defect in motility.

Table 1.

Swimming behavior of B. burgdorferi cheY mutants

| Strain | Mean velocity (μm/s) ± SDa | Mean no. of reversals/min ± SDa |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 20.0 ± 1.2b |

| cheY1 mutant | 8.6 ± 1.8 | 18.5 ± 1.5 |

| cheY2 mutant | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 19.0 ± 2.1 |

| cheY3 mutant | 10.5 ± 1.7 | 0.0c |

| cheY3+ mutant | 9.5 ± 0.8 | 25.0 ± 1.5d |

| cheY1 cheY2 mutant | 10.8 ± 2.3 | 21.0 ± 3.0 |

| cheY1 cheY3 mutant | 11.7 ± 2.9 | 0.0c |

| cheY2 cheY3 mutant | 10.1 ± 1.8 | 0.0c |

| cheY1 cheY2 cheY3 mutant | 11.7 ± 1.8 | 0.0c |

Standard deviations were calculated from data obtained from at least 10 individual tracked cells of each strain.

In the 20 reversals that occurred in the wild type during a 1-min interval, a prolonged flex lasting more than 0.5 s occurred 6 to 10 times.

Cells ran in only one direction and did not reverse.

In the cheY3+ mutant, all 25 reversals were accompanied by a flex lasting more than 0.5 s.

However, the swimming behavior of the mutants carrying the cheY3 mutation was different. The wild-type and cheY1, cheY2, and cheY1 cheY2 mutant cells reversed 18 to 22 times per minute, whereas the mutants carrying the cheY3 mutation failed to reverse, even when these cells were observed for several minutes. As expected, wild-type swimming behavior was restored when the cheY3 single mutant was complemented in trans, albeit with a slightly higher rate of reversal (Table 1). In addition, when the cheY3+ cells reversed, the reversal was consistently accompanied by an intervening prolonged flex which lasted longer than 0.5 s. In contrast, when the wild type reversed, only 6 to 10 times out of 20 was there an accompanying intervening prolonged flex lasting more than 0.5 s. These results suggest that cheY3+ had a higher rate of flexing than the wild type; this result could be related to the finding that the cheY3+ mutant produces ∼3.5 times more CheY3 than the wild type (Fig. 3a).

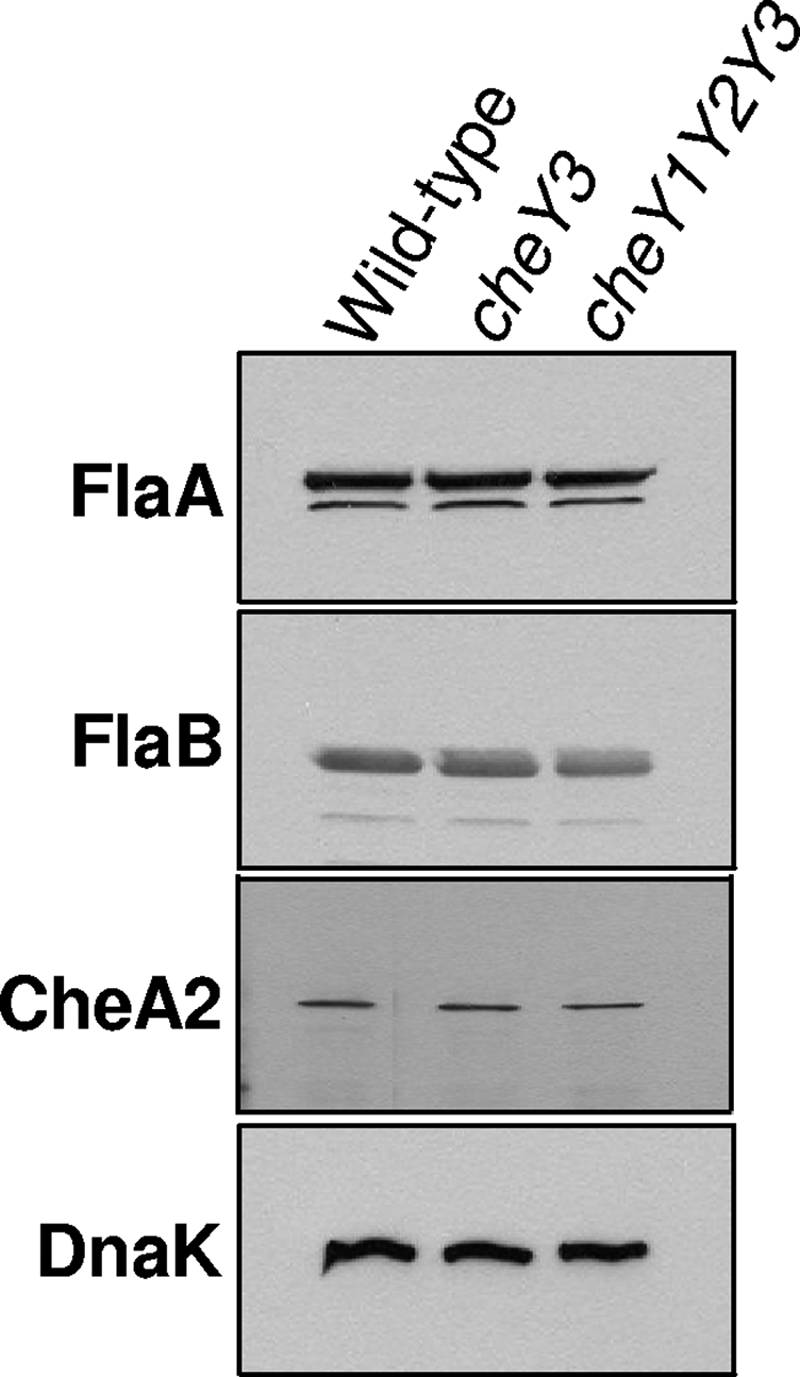

Synthesis of motility and chemotaxis proteins.

We tested whether the cheY3 mutation caused altered expression of other motility and chemotaxis genes that resulted in a constant running phenotype. Western blot analysis indicated that the level of expression of the major and minor periplasmic flagellar proteins FlaB and FlaA was similar in the cheY3 single mutant, cheY triple mutant, and wild-type cells (Fig. 5), indicating that mutations in cheY3 did not alter the expression of these flagellar proteins. In addition, because cheA2 mutants have also been shown to run constantly, we examined whether cheY3 mutants influenced CheA2 expression (1, 33). We found that the level of CheA2 expression was unaltered in the cheY3 mutant or the triple mutant cells (Fig. 5). Thus, the altered swimming and defective chemotactic behaviors observed in cheY3 strains were not due to the altered expression of CheA2.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis of motility and chemotaxis proteins among mutants. Western blot analysis using B. burgdorferi monoclonal anti-FlaB, -FlaA, and -DnaK and E. coli polyclonal anti-CheA antibodies. Cell lysates (10 μg protein) from wild-type and cheY3 and cheY1 cheY2 cheY3 mutant (cheY1Y2Y3) cells were probed with the indicated antibodies. For FlaB, 3 μg was loaded in each lane, and for Dnak, 2 μg of lysate was loaded in each lane.

Phosphorylation of CheY3.

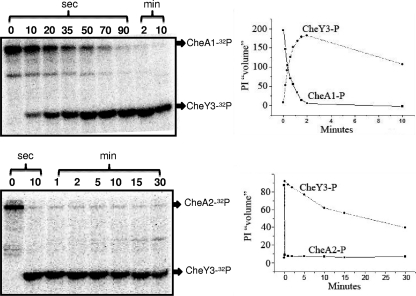

The genetic-phenotypic analysis indicates that only CheY3 is involved in chemotaxis. Previous work in our laboratory indicated that CheA2, but not CheA1, is involved in chemotaxis (1, 33). cheA2 and cheY3 are also in the same operon; we therefore asked if CheY3 is preferentially phosphorylated by CheA2 compared to CheA1. We also assessed the stability of the CheY3-P intermediate relative to CheY-P proteins of other bacteria. We first autophosphorylated CheA1 and CheA2 with [32P]ATP. CheA1-32P and CheA2-32P were found to be stable for at least 60 min, with no detectable loss of phosphate (not shown). The addition of an ∼7-fold molar excess of CheY3 resulted in the loss of phosphate from CheA1-32P and CheA2-32P and transfer to CheY3-P (Fig. 6). Phosphotransfer from CheA2-32P to CheY3 was markedly more efficient than that from CheA1-32P. Specifically, complete phosphotransfer occurred within 10 s with CheA2-32P, whereas it took 90 s with CheA1-32P. We also found that CheY3-32P had a half-life of greater than 10 min, which makes it markedly more stable than CheY-P of E. coli and most other bacteria (29, 48, 59). These results are consistent with those we and our colleagues recently obtained using a photometric assay for CheY3-P autodephosphorylation (47). Taken together, our results indicate that CheY3 is more efficiently phosphorylated by CheA2 than by CheA1, which agrees with the in vivo results that only CheA2 is involved in chemotaxis (1, 33) and that CheY3-P has a markedly weak autodephosphorylase activity.

Fig. 6.

Transfer of phosphate from CheA1-32P (top panels) and CheA2-32P (bottom panels) to CheY3. CheA1 and CheA2 were autophosphorylated with [32P]ATP, and unincorporated [32P]ATP was removed by centrifugation on Bio-Spin6 columns. Recovered CheA1-32P and CheA2-32P (2 μM each) were incubated with 14.8 μM CheY3 for the indicated periods of time. Reactions were stopped, and products were analyzed as described in the text. Phosphor images are shown in the left panels, and relative intensities (PI “volumes”) are shown in the right panels. CheA1-32P and CheA2-32P are represented as solid lines and squares, and CheY3-P is represented as circles and dashed lines.

DISCUSSION

The three cheY genes of B. burgdorferi are distributed throughout the chromosome. Two of the cheY genes (cheY2 and cheY3) reside in operons with other chemotaxis gene homologs, and the third cheY gene (cheY1) is in an operon with a motility gene and other genes of unknown function. B. burgdorferi is not unusual in possessing multiple homologs of chemotaxis genes in its genome. A recent genomic bioinformatic analysis of over 450 bacteria indicates that more than 50% of those with chemotaxis gene homologs have more than one copy of these genes (69). These homologs have been shown to participate not only in flagellum-mediated chemotaxis but also in type 4 pilus-based motility (4, 38), polysaccharide biosynthesis associated with pilus-based gliding motility (5), and flagellar morphogenesis (2). In many cases, genetic analysis has not been successful in sorting out the function of these chemotaxis gene homologs (49, 69).

In this study, we determined the role of the three B. burgdorferi cheY genes in chemotaxis and motility. All three CheY proteins were expressed in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 3), and sequence analysis indicates that all three cheY genes contain the conserved functional residues associated with response regulatory proteins that form phosphorylated intermediates (Fig. 1). Consistent with this analysis, CheY3 was phosphorylated by both CheA1 and CheA2 (Fig. 6), and recent results suggest that both CheY1 and CheY2 can also be phosphorylated by B. burgdorferi CheA proteins (M. Motaleb, M. Miller, and N. Charon, unpublished data). These results agree with previous reports that CheY3 can be phosphorylated by CheA2 (41, 42). We found that when the three cheY genes were inactivated singly or in combination, only mutations in cheY3 led to a nonchemotactic, constantly running phenotype; complementation of cheY3 restored the chemotactic response, but such cells had an increase in flexing (Fig. 4; Table 1). Thus, we conclude that only CheY3 is essential for chemotaxis under the conditions tested. We used an avirulent strain, and it is conceivable that in a virulent strain, CheY1 and CheY2 could participate in chemotaxis under conditions that best mimic those in the tick or the mammal hosts (10, 64). However, the identical cheY3::aphI mutation, when introduced into virulent strain B31-A3, resulted in cells with a constant running phenotype similar to that found with the avirulent strain (M. Motaleb and N. Charon, unpublished data). These results indicate that cheY3 is involved in chemotaxis in a virulent strain as well.

cheY3 is in a cluster with other genes (cheA2, cheW3, cheX, and cheY3) that are known to participate in chemotaxis (33, 42). Specifically, mutations in cheA2, cheX, and now cheY3 all result in a nonchemotactic phenotype (33, 42). Preliminary experiments with cheW3 mutants indicate that this gene is also involved in chemotaxis (K. Zhang, C. Li, and N. Charon, unpublished data). This chemotaxis gene cluster is well conserved in B. burgdorferi along with the spirochetes Treponema denticola and Treponema pallidum in both gene order and sequence identity (56). Because the treponemes have only one homolog of these genes in their genomes, these clusters also likely function in chemotaxis. In support of this proposition, analysis of a cheA mutant in T. denticola revealed it to be nonchemotactic (37).

Phosphorylation assays revealed that CheA1 and CheA2 transferred phosphate to CheY3. CheA2 was considerably more efficient than CheA1 (Fig. 6). These results are expected, as genetic analysis indicates that both CheA2 and CheY3, but not CheA1, are involved in chemotaxis (1, 33) and both CheA2 and CheY3 reside in the same operon. Although biochemical assays indicate that CheA1-P transferred its phosphate to CheY3 in vitro, there was no evidence of cross talk in which CheA1 could substitute for CheA2 in vivo (33).

The other noteworthy biochemical reaction is that CheY3-P is unusually stable, with a half-life of approximately 10 min. E. coli CheY-P is considerably less stable, with a half-life measured in seconds (29). To our knowledge, the only reported CheY-P homolog that is more stable is DifD of Myxococcus xanthus (5), with a half-life of 30 min. DifD is involved in both polysaccharide biosynthesis associated with social motility and chemotaxis. This stability has been related to the slow gliding movement of M. xanthus and its prolonged adaptation time for chemotaxis (5). At this time, we do not know why CheY3-P has such a prolonged half-life; however, it points to CheX, besides CheA2, playing a critical role in modulating CheY-P concentration.

The results presented here and previous results from our laboratory point toward CheY3 being the key response regulator controlling the direction of flagellar rotation in B. burgdorferi. In E. coli and S. enterica, CheY-P binding to motor proteins promotes CW rotation of flagella, resulting in tumbles; attractants reduce levels of CheY-P, generating longer runs (49, 50, 54, 60). Two conditions should lead to high CheY3-P concentrations in B. burgdorferi. One is inactivation of the cheX phosphatase, and the other is overproduction of CheY3 (12, 42). Both of these conditions result in an increase in flexing frequency, with cheX mutants constantly flexing (Table 1; Fig. 3a), (42). In contrast, mutations in either cheA2 or cheY3 should lead to negligible intracellular concentrations of CheY3-P. We found that mutations in either of these genes result in cells that constantly run (1, 33). These results suggest that CheY3-P affects the rotation of flagellar rotors in a manner similar to that found in E. coli: Both species constantly run under low CheY-P concentrations. However, the situation is more complex in B. burgdorferi and is presently not understood, as during its run, the periplasmic flagella at both ends rotate in opposite directions, not in the same direction as in E. coli (10, 33).

It is too early to understand the basis of periplasmic flagellar coordination that results in chemotaxis in B. burgdorferi. Recent results suggest that the MCPs are subpolarly located, form clusters at both ends, and are in close proximity to the flagellar motors (8, 70). CheA2 likely forms a complex via CheW3 with these MCPs, as CheA, CheW, and MCPs form complex arrays in other bacteria (3, 49). Thus, CheA2 is also likely to be subpolarly localized. Based on these assumptions and the evidence that CheY3 is the key response regulator essential for chemotaxis, two possible models of flagellar coordination are evident. One model states that if an attractant is bound to MCPs at one end of the cell, a signal in the form of a change in the CheY3-P concentration is generated at that end that affects flagellar rotation not only at the proximal end but also at the distal cell end. Given B. burgdorferi's velocity of ∼10 μm/s (Table 1), a change in CheY3-P concentration must be rapidly sensed at the distal end of the cell by this model. Diffusion of CheY3-P to the distal end is unlikely to be responsible for this coordination, as it is too slow (using t = L2/D, where L is a cell length of 10 μm and D is 10 μm2/s, t is 10 s). Thus, it would take at least 10 s for a change in CheY3-P concentration generated at one end to diffuse to the other end (66). Perhaps CheY3-P is transported to the distal end through a presently unknown internal cytoskeletal structure, and the relative stability we find in CheY3-P is essential for this to occur (9). For example, the gliding motion of M. xanthus is related to intracellular movement of AglZ, and this movement is mediated by the cell skeletal protein MreB (38). Because transport of AglZ from one cell end to the other is on the order of several minutes, a CheY3 transport system in B. burgdorferi would, by necessity, have to be considerably faster. Our results do not rule out the possibility that CheY3-P acts at another, unknown, site such that the membrane potential is altered when the cell is undergoing chemotaxis (27).

As an alternative, perhaps there is no internal signal that coordinates the motors at both cell ends. According to this model, flagellar coordination and chemotaxis are achieved by the attractant binding to either one or both of the MCP clusters at the cell ends. The change in CheY3-P concentration generated by this binding specifically affects the direction of rotation of the motors that are adjacent to those MCPs. For example, consider the following scenario. If the attractant binds the MCPs at one cell end, it causes the motors only at that end of the cell to change their direction of rotation, and perhaps the cell flexes. In contrast, if attractant molecules simultaneously bind to the MCPs at both cell ends, the motors at both ends change directions and the cell runs. Now that we know which compounds serve as attractants (1) and that CheY3 is the response regulator, we are finally in a position to determine how the rotation of periplasmic flagella in these spirochetes is coordinated for chemotaxis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Barbour, J. Benach, B. Johnson, and P. Matsumura for sharing antibodies, P. Stewart and P. Rosa for sharing plasmids, and A. Cockburn, K. Miller, M. James, U. Pal, B. Schraf, and R. Silversmith for suggestions.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI29743 to N.W.C. and an East Carolina University Research and Development start-up grant to M.A.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bakker R. G., Li C., Miller M. R., Cunningham C., Charon N. W. 2007. Identification of specific chemoattractants and genetic complementation of a Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis mutant: flow cytometry-based capillary tube chemotaxis assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1180–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berleman J. E., Bauer C. E. 2005. A che-like signal transduction cascade involved in controlling flagella biosynthesis in Rhodospirillum centenum. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1390–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhatnagar J., et al. 2010. Structure of the ternary complex formed by a chemotaxis receptor signaling domain, the CheA histidine kinase, and the coupling protein CheW as determined by pulsed dipolar ESR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 49:3824–3841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhaya D., Takahashi A., Grossman A. R. 2001. Light regulation of type IV pilus-dependent motility by chemosensor-like elements in Synechocystis PCC6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:7540–7545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Black W. P., Schubot F. D., Li Z., Yang Z. 2010. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation among Dif chemosensory proteins essential for exopolysaccharide regulation in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 192:4267–4274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boesch K. C., Silversmith R. E., Bourret R. B. 2000. Isolation and characterization of nonchemotactic cheZ mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:3544–3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bono J. L., et al. 2000. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 182:2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Briegel A., et al. 2009. Universal architecture of bacterial chemoreceptor arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17181–17186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cabeen M. T., Jacobs-Wagner C. 2010. A metabolic assembly line in bacteria. Nat. Cell Biol. 12:731–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charon N. W., Goldstein S. F. 2002. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: the spirochetes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:47–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charon N. W., et al. 2009. The flat ribbon configuration of the periplasmic flagella of Borrelia burgdorferi and its relationship to motility and morphology. J. Bacteriol. 191:600–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clegg D. O., Koshland D. E., Jr 1984. The role of a signaling protein in bacterial sensing: behavioral effects of increased gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:5056–5060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coleman J. L., Benach J. L. 1992. Characterization of antigenic determinants of Borrelia burgdorferi shared by other bacteria. J. Infect. Dis. 165:658–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dombrowski C., et al. 2009. The elastic basis for the shape of Borrelia burgdorferi. Biophys. J. 96:4409–4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elias A. F., et al. 2003. New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fosnaugh K., Greenberg E. P. 1988. Motility and chemotaxis of Spirochaeta aurantia: computer-assisted motion analysis. J. Bacteriol. 170:1768–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frank K. L., Bundle S. F., Kresge M. E., Eggers C. H., Samuels D. S. 2003. aadA confers streptomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 185:6723–6727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraser C. M., et al. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ge Y., Charon N. W. 1997. An unexpected flaA homolog is present and expressed in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 179:552–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ge Y., Charon N. W. 1997. Molecular characterization of a flagellar/chemotaxis operon in the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 153:425–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge Y., Li C., Corum L., Slaughter C. A., Charon N. W. 1998. Structure and expression of the FlaA periplasmic flagellar protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 180:2418–2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ge Y., Old I., Saint Girons I., Charon N. W. 1997. The flgK motility operon of Borrelia burgdorferi is initiated by a sigma 70-like promoter. Microbiology 143:1681–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ge Y., Old I. G., Saint Girons I., Charon N. W. 1997. Molecular characterization of a large Borrelia burgdorferi motility operon which is initiated by a consensus sigma70 promoter. J. Bacteriol. 179:2289–2299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldstein S. F., Buttle K. F., Charon N. W. 1996. Structural analysis of Leptospiraceae and Borrelia burgdorferi by high-voltage electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 178:6539–6545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldstein S. F., Charon N. W., Kreiling J. A. 1994. Borrelia burgdorferi swims with a planar waveform similar to that of eukaryotic flagella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:3433–3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldstein S. F., et al. 2010. The chic motility and chemotaxis of Borrelia burgdorferi, p. 161–181 In Samuels D. S., Radolf J. D. (ed.), Borrelia: molecular biology, host interaction and pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goulbourne E. A., Jr., Greenberg E. P. 1981. Chemotaxis of Spirochaeta aurantia: involvement of membrane potential in chemosensory signal transduction. J. Bacteriol. 148:837–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harley C. B., Reynolds R. P. 1987. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:2343–2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hess J. F., Oosawa K., Kaplan N., Simon M. I. 1988. Phosphorylation of three proteins in the signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis. Cell 53:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hovind-Hougen K. 1984. Ultrastructure of spirochetes isolated from Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes dammini. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:543–548 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hyakutake A., et al. 2005. Only one of the five CheY homologs in Vibrio cholerae directly switches flagellar rotation. J. Bacteriol. 187:8403–8410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kudryashev M., Cyrklaff M., Wallich R., Baumeister W., Frischknecht F. 2010. Distinct in situ structures of the Borrelia flagellar motor. J. Struct. Biol. 169:54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li C., et al. 2002. Asymmetrical flagellar rotation in Borrelia burgdorferi nonchemotactic mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6169–6174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li C., Motaleb M. A., Sal M., Goldstein S. F., Charon N. W. 2000. Spirochete periplasmic flagella and motility. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:345–354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li C., Xu H., Zhang K., Liang F. T. 2010. Inactivation of a putative flagellar motor switch protein FliG1 prevents Borrelia burgdorferi from swimming in highly viscous media and blocks its infectivity. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1563–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu J., et al. 2009. Intact flagellar motor of Borrelia burgdorferi revealed by cryo-electron tomography: evidence for stator ring curvature and rotor/C-ring assembly flexion. J. Bacteriol. 191:5026–5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lux R., Sim J., Tsai J. P., Shi W. 2002. Construction and characterization of a cheA mutant of Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 184:3130–3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mauriello E. M., Mignot T., Yang Z., Zusman D. R. 2010. Gliding motility revisited: how do the Myxobacteria move without flagella? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:229–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller L. D., Russell M. H., Alexandre G. 2009. Diversity in bacterial chemotactic responses and niche adaptation. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 66:53–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Motaleb M. A., et al. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10899–10904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Motaleb M. A., Miller M. R., Bakker R. G., Li C., Charon N. W. 2007. Isolation and characterization of chemotaxis mutants of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi using allelic exchange mutagenesis, flow cytometry, and cell tracking. Methods Enzymol. 422:421–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Motaleb M. A., et al. 2005. CheX is a phosphorylated CheY phosphatase essential for Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 187:7963–7969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Motaleb M. A., Sal M. S., Charon N. W. 2004. The decrease in FlaA observed in a flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi occurs posttranscriptionally. J. Bacteriol. 186:3703–3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Muff T. J., Ordal G. W. 2008. The diverse CheC-type phosphatases: chemotaxis and beyond. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1054–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. 2000. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302:205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Park S. Y., et al. 2004. Structure and function of an unusual family of protein phosphatases: the bacterial chemotaxis proteins CheC and CheX. Mol. Cell 16:563–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pazy Y., et al. 2010. Identical phosphatase mechanisms achieved through distinct modes of binding phosphoprotein substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1924–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Porter S. L., Armitage J. P. 2002. Phosphotransfer in Rhodobacter sphaeroides chemotaxis. J. Mol. Biol. 324:35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Porter S. L., Wadhams G. H., Armitage J. P. 2008. Rhodobacter sphaeroides: complexity in chemotactic signalling. Trends Microbiol. 16:251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Porter S. L., Wadhams G. H., Armitage J. P. 2011. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Porter S. L., et al. 2006. The CheYs of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 281:32694–32704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rosa P. A., Tilly K., Stewart P. E. 2005. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sal M. S., et al. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J. Bacteriol. 190:1912–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sarkar M. K., Paul K., Blair D. 2010. Chemotaxis signaling protein CheY binds to the rotor protein FliN to control the direction of flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:9370–9375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sartakova M., Dobrikova E., Cabello F. C. 2000. Development of an extrachromosomal cloning vector system for use in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:4850–4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Seshadri R., et al. 2004. Comparison of the genome of the oral pathogen Treponema denticola with other spirochete genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5646–5651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Silversmith R. E., et al. 2003. CheZ-mediated dephosphorylation of the Escherichia coli chemotaxis response regulator CheY: role for CheY glutamate 89. J. Bacteriol. 185:1495–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Silversmith R. E., Smith J. G., Guanga G. P., Les J. T., Bourret R. B. 2001. Alteration of a nonconserved active site residue in the chemotaxis response regulator CheY affects phosphorylation and interaction with CheZ. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18478–18484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sourjik V., Schmitt R. 1998. Phosphotransfer between CheA, CheY1, and CheY2 in the chemotaxis signal transduction chain of Rhizobium meliloti. Biochemistry 37:2327–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sourjik V., Armitage J. P. 2010. Spatial organization in bacterial chemotaxis. EMBO J. 29:2724–2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sourjik V., Berg H. C. 2000. Localization of components of the chemotaxis machinery of Escherichia coli using fluorescent protein fusions. Mol. Microbiol. 37:740–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sourjik V., Schmitt R. 1996. Different roles of CheY1 and CheY2 in the chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti. Mol. Microbiol. 22:427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Szurmant H., Ordal G. W. 2004. Diversity in chemotaxis mechanisms among the bacteria and archaea. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:301–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tilly K., Rosa P. A., Stewart P. E. 2008. Biology of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 22:217–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Trueba G. A., Old I. G., Saint G., Johnson R. C. 1997. A cheA cheW operon in Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Res. Microbiol. 148:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vaknin A., Berg H. C. 2004. Single-cell FRET imaging of phosphatase activity in the Escherichia coli chemotaxis system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:17072–17077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Volz K. 1993. Structural conservation in the CheY superfamily. Biochemistry 32:11741–11753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wolgemuth C. W., Charon N. W., Goldstein S. F., Goldstein R. E. 2006. The flagellar cytoskeleton of the spirochetes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 11:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wuichet K., Zhulin I. B. 2010. Origins and diversification of a complex signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Sci. Signal. 3:ra50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Xu H., Raddi G., Liu J., Charon N. W., Li C. 2011. Chemoreceptors and flagellar motors are subterminally located in close proximity at the two cell poles in spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 193:2652–2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yang Y., Li C. 2009. Transcription and genetic analyses of a putative N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase in Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 290:164–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang P., Khursigara C. M., Hartnell L. M., Subramaniam S. 2007. Direct visualization of Escherichia coli chemotaxis receptor arrays using cryo-electron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:3777–3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao R., Collins E. J., Bourret R. B., Silversmith R. E. 2002. Structure and catalytic mechanism of the E. coli chemotaxis phosphatase CheZ. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:570–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]