Abstract

Our data show that unlike bacteriophage λ, repressor bound at OL of bacteriophage 933W has no role in regulation of 933W repressor occupancy of 933W OR3 or the transcriptional activity of 933W PRM. This finding suggests that a cooperative long-range loop between repressor tetramers bound at OR and OL does not form in bacteriophage 933W. Nonetheless, 933W forms lysogens, and 933W prophage display a threshold response to UV induction similar to related lambdoid phages. Hence, the long-range loop thought to be important for constructing a threshold response in lambdoid bacteriophages is dispensable. The lack of a loop requires bacteriophage 933W to use a novel strategy in regulating its lysis-lysogeny decisions. As part of this strategy, the difference between the repressor concentrations needed to bind OR2 and activate 933W PRM transcription or bind OR3 and repress transcription from PRM is <2-fold. Consequently, PRM is never fully activated, reaching only ∼25% of the maximum possible level of repressor-dependent activation before repressor-mediated repression occurs. The 933W repressor also apparently does not bind cooperatively to the individual sites in OR and OL. This scenario explains how, in the absence of DNA looping, bacteriophage 933W displays a threshold effect in response to DNA damage and suggests how 933W lysogens behave as “hair triggers” with spontaneous induction occurring to a greater extent in this phage than in other lambdoid phages.

INTRODUCTION

Studies of how the lysis-lysogeny decisions of lambdoid bacteriophages are regulated have illustrated the importance of short- and long-range cooperative DNA binding by proteins in controlling a complex gene regulatory network. In all lambdoid phages, the repressor protein directs the establishment and maintenance of the lysogenic state by simultaneously repressing transcription of the genes needed for lytic phage growth and activating transcription of a gene needed for lysogen formation (30). Based primarily on studies of bacteriophage λ, two different cooperative repressor-DNA binding events are thought to be required for regulation of lambdoid phage lysogen development. The first involves formation of a repressor tetramer between two repressor dimers, one bound to each of the adjacent OR1 and OR2 sites. A similar tetramer is also formed at the OL1 and OL2 sites. The “side-by-side” cooperative binding by a repressor tetramer is prerequisite to forming a stable λ lysogens (2, 20, 30).

Additional cooperative interactions between two tetramers, each bound to a pair of adjacent operators that are separated by >2.5 kb, occur in bacteriophages λ and P22 (13–15, 31). In λ, a repressor octamer-mediated OL-cI8-OR complex forms with the intervening DNA looping out (3, 13, 15). This long-range cooperative interaction helps modulate the prophage's compensatory response to low doses of DNA damage (3) and thereby regulates lysogen stability. In all well-studied lambdoid phages, the amount of phage produced is not linearly related to the amount of DNA damage until a particular threshold amount of DNA damage is absorbed by the lysogen. This threshold is due to the compensatory effect of removing the repressor from a partially occupied OR3, an occupancy that is facilitated by the long-range loop mediated by a repressor octamer bound to OL1, OL2, OR1, and OR2 (3). The discovery of the long-range interaction between repressor tetramers bound at OR and OL in phage λ seemingly solved two long-standing puzzles: (i) the function of cI binding at OL3 and (ii) given that the λ repressor's affinity for OR3 is too weak to significantly repress its own promoter, how does autogenous negative control work?

Despite the apparent importance of long-range cooperativity in stabilizing lambdoid phage lysogens, several recent observations indicate that this interaction may not be required. We and others have reported that unlike all other well-studied bacteriophages, bacteriophage 933W contains only two, not three, repressor binding sites in OL (16, 23, 36) (Fig. 1). Bacteriophage 933W is derived from the Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strain EDL933. The gene encoding Shiga toxin is present on bacteriophage 933W and is part of an operon directly controlled by the bacteriophage PR′ promoter. Shiga toxin is not produced when the bacteriophage is in its lysogenic state, but toxin production increases substantially upon phage lysogen induction. As a result of its downstream position in the lytic cascade, the activity of PR′ and thereby Shiga toxin production by 933W are ultimately controlled by factors that influence 933W repressor DNA binding. Hence, in addition to providing information on bacteriophage gene control mechanisms, these studies will inform studies aimed at controlling Shiga toxin production in infected individuals.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the 933W immunity region. The positions of OR1, OR2, and OR3, of OL1 and OL2, and of the repressor (cI) and cro genes (Cro) are indicated by boxes; the transcription start sites of PL, PRM, and PR are indicated by bent arrows.

The absence of an OL3 site suggests that 933W repressor binding to OR3 may not be assisted by formation of a λ-like OL-cI8-OR looped complex. Also, we reported earlier that in intact 933W OR, the 933W repressor does not bind its OR1 and OR2 sites at an identical concentration (23), suggesting that the 933W repressor is incapable of binding cooperatively to these two adjacent sites. Cooperativity is not essential to the construction a of lysis-lysogeny switch in a lambdoid phage. For example, Babić and Little found that cis-acting mutations can allow a λ bacteriophage encoding a repressor that is incapable of forming DNA-bound tetramers (and, presumably, octamers) to form stable lysogens (2). Taken together, these results imply that the lysis-lysogeny regulatory circuitry of bacteriophage 933W does not involve cooperative binding of repressor tetramers or octamers.

Here we characterize the DNA binding and gene regulatory strategies that allow 933W bacteriophage to function as an outwardly “normal” temperate phage. Our findings confirm that the basic transcriptional behavior of 933W's lysis-lysogeny circuitry resembles that found in other well-characterized lambdoid phages. However, these data show that 933W repressors bound at OL regulate neither OR3 occupancy nor PRM activity. Since the activity of 933W PRM, the maintenance of lysogeny, is crucial, the stability of 933W lysogens is not regulated by a long-range DNA loop. Instead, our data show that OR3 occupancy and thus PRM activity depend on a small difference in the intrinsic affinities of the 933W repressor for OR2 and OR3. It is clear that 933W bacteriophage has evolved alternative strategies to regulate the lysogen stability decision. Remarkably, some of these strategies overlap those of mutant λ phage previously identified by Babić and Little (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages, and DNA.

All plasmids were propagated in either Escherichia coli strain K802 (40) or strain JM101 (27). 933W repressor was purified from the E. coli strain BL21(DE3)::pLysS (Novagen, Madison, WI) bearing a plasmid that directs its overexpression (p933WR) as described previously (23). Construction of the plasmid containing the 933W OR operator was described previously (23). Templates for DNase I footprinting and transcription were generated by PCR from these plasmids as described below.

The λimm434 bacteriophage used in lysogen induction experiments was from our collection. λimm933W (36) was the generous gift of D. Friedman (University of Michigan). Lysogens were formed in MG1655.

Deletion of the OL region of λimm933W was effected by using the lambda Red/Gam homologous recombination system expressed on helper plasmid pKD46 (12). For this process, OL, as well as part of the N gene found on p933WOL (23), was replaced with the spectinomycin resistance gene. Deletion of the 933W OL region within the lysogen was confirmed via PCR. As a consequence of the deletion of part of the N gene, the λimm933WΔOL lysogen is not inducible with mitomycin.

Primers for site-directed mutagenesis, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), and the primer for detecting 933W repressor occupancy of OR (see below) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

In vitro transcription assays.

Template DNA was PCR amplified from the appropriate plasmid by using the standard M13 forward and reverse primers and gel purified. Increasing amounts of 933W repressor were incubated with 8 nM template DNA for 10 min at 25°C in transcription buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 75 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). E. coli RNA polymerase (2 mg/ml) was added and allowed to form open complexes at 37°C for 10 min. Single-round transcription was then initiated by adding a nucleoside triphosphate mix (2.5 mM each for ATP, CTP, and GTP, 0.5 mM UTP and [α-32P]UTP, and 1 mM heparin), and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Transcription was stopped with formamide dye and heated to 95°C for 4 min, and products were separated on a 6% acrylamide–7 M urea gel in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE; 89 mM Tris, 89 mM borate, 1 mM EDTA). Radiolabeled products were visualized and quantified by phosphorimaging.

UV induction of phage lysogens.

Measurements of the UV induction threshold response were performed using methods similar to those described previously (25). Briefly, lysogens were grown in LB to mid-log phase and then chilled, centrifuged, and washed with TMG buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgSO4, 10 μg/ml gelatin). Resuspended cells were irradiated at a distance of 20 cm (∼1 μW/cm2) by using a 254-nm UV light (Mineralight UVG-54). At various exposure times, aliquots of the cultures were plated on LB to ascertain viable bacterial cell counts. The UV-exposed culture was then diluted 1:10 in 5 ml of LB and incubated at 37°C shaking for 2 h. The induced culture was treated with CHCl3, and debris was removed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 1 min. Phage titers were measured by plating as described previously (1).

EMSA.

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed as essentially described (23). DNA containing the individual naturally occurring 933W repressor binding sites was obtained by annealing 60-base oligonucleotides containing the 15-bp 933W binding site sequence and two additional naturally occurring bases on either end of the identified site. The DNA fragments were radioactively labeled at their 5′ ends by incubating the DNA with [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) in the presence of T4 polynucleotide kinase (Epicentre, Inc., Madison, WI). OR1 DNA was also radiolabeled using [α-32P]dATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) in place of dATP in a PCR mixture with an OR1-containing plasmid as a template to increase the radioactive signal and detect DNA to concentrations below 0.1 nM. Labeled DNA was incubated with the specified concentrations of 933W repressor protein in binding buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA], 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG], 1 mM DTT) for 10 min at 25°C. The protein-DNA complexes were resolved on 5% polyacrylamide gels at 25°C. The electrophoresis buffer was 1× TBE. The amounts of protein-DNA complexes present on the dried gels were quantified using a Storm imager (GE Lifesciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Values of the dissociation constant (KD) were determined by nonlinear squares fitting of the EMSA data using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Each dissociation constant was determined from at least eight replicate measurements. Two-tailed t tests were employed to determine the significance of observed differences in dissociation constants of the various 933W repressor-DNA complexes.

DNase I footprinting.

Template DNA was PCR amplified from the desired plasmid using 5′-end-labeled standard M13 forward and unlabeled M13 reverse primers and gel purified. Following phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation, this DNA (≤0.05 nM) was incubated without or with 933W repressor in binding buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2,100 μg/ml BSA, 1 mM DTT) for 10 min at 25°C prior to addition of sufficient DNase I to generate, on average, one cleavage per DNA molecule with 5 min of additional incubation. The cleavage reactions were terminated by precipitation with ethanol and sec-butanol dehydration, and the DNA was dissolved in 90% formamide solution containing tracking dyes. The products along with chemical sequencing reactions (Maxam Gilbert 1980) derived from the same templates were resolved on 6% acrylamide gels containing 7 M urea in 1× TBE. Cleavage products were visualized using a Storm imager (GE Lifesciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Values of the dissociation constant (KD) were determined by nonlinear squares fitting of the measured intensities of repressor-protected bands for each of the three individual binding sites. Each dissociation constant was determined from measurements made in three independent experiments. The reported dissociation constants varied by ≤20%.

In vivo dimethylsulfate (DMS) footprinting.

Both MG1655::λimm933W and MG16655::λimm933WΔOL lysogens were transformed with pGP1-2 (35), which encodes T7 RNA polymerase and whose synthesis is under the control of a temperature-sensitive lambda repressor. Each of these two strains were subsequently separately transformed with p933WR or pET17b (EMB Biosciences).

Cultures of the two plasmid-containing lysogens were grown for 16 h at 37°C in LB with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. DMS was added to the cultures at a final concentration of 7.9 μM and incubated with shaking for 5 min at 37°C. The reactions were stopped by addition of an equal volume of ice-cold LB and immediately placed on ice. Genomic DNA from 1.5 ml of treated cells was isolated using lysozyme-phenol-RNase A essentially as described previously (32) and resuspended in PCR buffer (0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.001% gelatin). Resuspended genomic DNA (20 μg) was used as template for each primer extension reaction.

A primer complementary to a sequence just outside the 933W OR region, in the cro gene, 5′-CCTTTAATCGGCTCATCAAGATTTTGCAT-3′, was 5′ end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA) and [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA). Labeled primer was added to the dissolved genomic DNA to a final concentration of 1.4 μM, and the extension reaction was initiated with the addition Taq polymerase followed by thermocycling. After 35 rounds of extension, the products of extension reactions (one-half the reaction volume) were loaded onto 6% acrylamide–7 M urea gel (89 mM Tris, 89 mM borate, 1 mM EDTA) after addition of formamide dye and boiling of samples for 4 min. A sequencing ladder was also loaded next to the primer extension reaction mixtures (Sequenase DNA sequencing kit; USB, Cleveland, OH). Gels were dried and imaged with a Storm imager.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Cultures of the plasmid-containing MG1655::λimm933W and MG166::λimm933WΔOL lysogens were grown to early log phase at 30°C in LB with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Cultures were shifted to 42°C and grown until late log phase. RNA was extracted from 0.5 ml of cells by using the QuickExtract RNA extraction kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI). RNA was further purified by acid phenol extraction followed by chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and precipitation. RNA was resuspended in 22 μl of DNase I buffer and RiboGuard, and residual genomic DNA was removed by treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Epicentre, Madison, WI) for 1 h at 37°C. cDNA synthesis reaction mixtures containing purified RNA, Affinityscript buffer, forward primer, and Affinityscript reverse transcriptase/RNase block enzyme mix (Agilent Technologies, Cedarville, TX) were incubated at 25°C for 5 min to allow primer annealing, 45°C for 45 min for cDNA synthesis, and finally at 95°C for 5 min to heat kill the reverse transcriptase. Quantitation of RNA was performed by real-time PCR. DNA products were detected using Sybr Green I (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes Inc., Carlsbad, CA) in a MiniOpticon real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Primers used for amplification of PRM transcript cDNA were complementary to a portion of the 933W open reading frames 23 and 24. (933W PRM trans FWD, 5′-GCCGCTCTAACACCTAGTATTCTC-3′, and 933W PRM trans RVS, 5′-TAAGGCCGCCTGAACATATC-3′). As an internal control for RNA preparation, separate real-time PCR analyses were performed on the cDNA preparations of the E. coli UmuC gene transcript from the same RNA preparations as the PRM transcripts. These real-time PCR assays used primers complementary to a portion of the UmuC gene (FWD UmuC, 5′-GATTTATGGGGTAAACCGGTGG-3′; RVS UmuC, 5′-CAGTCAGATCGAGACAATTACG-3′). Standard curves for the real-time PCR analyses were made using known template amounts of a plasmid containing the region of interest.

Numerical simulation of transcription data.

Occupancies of OR1, OR2, and OR3 at various 933W repressor concentrations were calculated using the dissociation constants given in Fig. 5, below, and the following equation: frOx bound = −{([Ox total] + [933W Rtotal] + KD) − {([Ox total] + [933W Rtotal] + KD)2 − 4[Ox total][933W Rtotal]}1/2}/(2[Ox total]), where Ox is either OR1, OR2, or OR3 and Rtotal is the total repressor concentration. For the simulations, the DNA concentration was fixed at the value used in the transcription experiments. Relative activities of PRM transcription were calculated using the experimentally verified assumptions that 933W repressor bound at OR2 activates PRM and that 933W repressor bound at OR3 represses the activity of this promoter. Maximal promoter activity was set to 60, corresponding to the observed maximal activity of PRM relative to PR, as measured on a template bearing a mutation in OR3 that prevented repressor binding.

Fig. 5.

Sequences and intrinsic affinities of 933W for separate naturally occurring 933W operators. (A) Binding of 933W repressor to individual naturally occurring binding sites. Various concentrations of 933W repressor were mixed with radiolabeled binding site-containing DNA, and protein-DNA complex formation was detected as described in Materials and Methods. Points represent averages of ≥8 replicate experiments. Lines represent best nonlinear least-squares fits to the data based on a hyperbolic equation. (B) The sequences and dissociation constants (KD [lswb]± standard deviation]) of 933W repressor binding to OR1, OR2, OR3, OL1, and OL2. Dissociation constants were derived from data shown in panel A and determined as described in Materials and Methods. Standard deviations were calculated from the averages of ≥8 replicate experiments.

Statistical methods.

Where employed, tests for statistical significance of differences between paired data sets were performed using two-tailed t tests.

RESULTS

Examination of the threshold response to UV light.

An OL3-bound λ repressor cooperatively assists binding of repressor to OR3 (15). This interaction requires the formation of an octameric λ repressor-DNA complex containing two tetramers of λ repressor, one bound at OR1 and OR2 and another at OL1 and OL2 (15). Deletion of OL eliminates the increased PRM activity in response to low doses of UV (no derepression effect), suggesting the DNA damage “threshold response” depends on formation of the OL-cI8-OR loop in phage λ (3). The observation that bacteriophage 933W lacks an OL3 site (16, 23, 36) (Fig. 1) indicates that unlike other lambdoid phages (3), 933W either does not display a threshold response or that the threshold response of this phage is constructed differently from that of other lambdoid phages. To distinguish between these alternatives, we compared the ability of UV light to induce lysogens of two different hybrid bacteriophages: (i) λimm933W, a bacteriophage that contains the entire immunity region of 933W and whose lysis-lysogeny decision is controlled by 933W repressor-DNA interactions, and (ii) λimm434, a bacteriophage that bears the immunity region of bacteriophage 434 and whose repressor is capable of cooperatively binding its DNA sites. Other than the immunity regions (i.e., DNA between the N gene [immediately upstream of OL] and the end of the cro gene [immediately downstream of OR]), the sequences of these two phages are identical. Hence, any differences in the ability of UV light to induce these two phages can be directly attributed to differences in gene regulation mechanisms encoded within the immunity region.

At low UV dosages, neither the λimm434 nor λimm933W lysogen produces a significant number of bacteriophage (Fig. 2). In contrast, once the UV exposure reached a threshold dose of ∼3.5 J/m2, the amount of phage produced by both of these strains rose sharply and increased linearly with UV dosage (Fig. 2). These findings show that the 933W immunity region codes for a threshold response to DNA damage. The UV threshold set point value for 933W is nearly identical to that observed with bacteriophage λ lysogens (3, 25), but since 933W lacks an OL3 site, its response must be enabled by a mechanism different from phage λ and its related bacteriophages.

Fig. 2.

Demonstration of the λimm933W threshold response to UV induction, similar to that of λimm434. Lysogens containing either 933W (λimm933W) or 434 (λimm434) immunity regions were subjected to either no UV light or increasing doses of UV light. Lysogens were then diluted and incubated with aeration at 37°C for 2 h to allow phage induction. Phage titers were determined by plating on MG1655. Cell numbers were determined by plating aliquots of cells on LB plates prior to the 2-h incubation. Phage numbers are expressed as the fraction of the maximal amount of phage-forming units (PFU) per cell-forming units (CFU). Error bars represent standard deviations calculated from the averages of 5 replicate experiments.

Repressor occupancy of OR3 is independent of the presence of OL.

Despite the absence of an OL3 site (16, 23), 933W repressor bound at OL could have a role in regulating repressor occupancy of OR3, the key element of the threshold response (Fig. 2). We wished to directly test whether the OL region of 933W has any role in regulating repressor occupancy of OR3. To do this we first used DMS footprinting to examine 933W repressor occupancy in vivo in both a λimm933W lysogen (which bears an intact 933W OR and OL) and a λimm933WΔOL lysogen, in which the OL region of λimm933W has been deleted. These strains were transformed with either a control plasmid or one that directs the synthesis of 933W repressor (see Materials and Methods). These strains were exposed to DMS, and the DMS modification/protection pattern was detected by primer extension and using a radioactively labeled primer.

To assist with identification of the 933W repressor-protected bands in the samples isolated from the cells, genomic DNA was isolated from untreated cells and treated in vitro with DMS in the absence or presence of purified 933W repressor. As expected, 933W repressor occupancy of OR1, OR2, and OR3 on isolated DNA in vitro was detectable by a repressor-dependent decrease in the intensity of several DMS-reactive guanine residues in these sites (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 and 8). For example, the DMS reactivity at positions 5′G, 7′G, and 2G in OR1 and 5′G in OR2 in wild-type DNA decreased in the presence of 933W repressor. The ability of the repressor to protect these bases from modification in vitro was unaffected by deletion of the OL region (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 7 and 8 with lanes 8 and 9).

Fig. 3.

Deletion of 933W OL does not affect repressor occupancy at OR3. (A) Representative DMS footprinting gel. DMS methylation of 933W genomic DNA template was used to detect repressor protection of OR sites. DMS was either not added (lanes 1 and 2) to lysogenic cells (lanes 3 to 6) or isolated genomic DNA from lysogens was added (lanes 7 to 10) and allowed to react at 37°C for 5 min. Isolated genomic DNA in all lanes was subjected to primer extension using a radiolabeled DNA primer complementary to regions just outside of the 933W OR and Taq polymerase (see Materials and Methods). Locations of guanine bases in OR3, OR2, and OR1 sensitive to methylation by DMS are indicated. For the in vivo DMS treatment (lanes 3 to 6), DMS was added to overnight cultures of λimm933W (wt) or λimm933WΔOL (ΔOL) grown at 37°C. The level of 933W repressor was determined by either endogenous lysogen levels (lanes 3 and 5) or endogenous levels plus additional repressor expressed from p933WR (lanes 4 and 6). No DMS was used in lanes 1 and 2. For the in vitro DMS treatment (lanes 7 to 10), DMS was added to purified genomic DNA isolated from λimm933W (lanes 7 and 8) or λimm933WΔOL (lanes 9 and 10) lysogens. Lanes 7 and 9 had no 933W repressor present upon DMS addition. In lanes 8 and 10, saturating amounts of purified 933W repressor were added to genomic DNA prior to the DMS methylation reaction. (B) Quantification of in vitro DMS methylation intensities of guanines in OR3 (see panel A, lanes 7 to 10). (C) Quantification of in vivo DMS methylation intensities of guanines in OR3 (see panel A, lanes 3 to 6). In panels B and C, intensities were normalized to the reactivity at position 1′. Error bars in panels B and C represent standard deviations derived from 4 replicate experiments.

Our major focus with respect to the effect of OL deletion on 933W repressor occupancy of its binding sites in OR concerned OR3. Repressor binding to this site was therefore considered in detail. In the absence of any 933W repressor, the DMS reactivities of the four guanine residues on the top strand in OR3 (positions 2, 7′, 5′, and 1′) were unaffected by the presence or absence of the OL region (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 7 and 9). Also, for both these DNAs, added 933W repressor protected the guanines at positions 2 and 5′ of OR3 from DMS modification (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 8 and 10). The extent of repressor-mediated protection of each of the guanines at positions 2 and 5′ was essentially identical in both the λimm933W and λimm933WΔOL DNAs (Fig. 3B). These observations establish the protection DMS modification pattern of the repressor-bound OR3 site and provide a basis for understanding the in vivo DMS modification patterns.

Similar to the pattern of DMS reactivity seen in vitro, once inside cells DMS modifies guanines at positions 2, 7′, 5′, and 1′ of OR3. However, compared to the results obtained in vitro in the absence of repressor, the relative DMS reactivities of the guanine residues at positions 2 and 5′ in OR3 are lower than seen at positions 7′ and 1′ (Fig. 3A, compare lane 3 to lanes 7 and 8 and lane 5 to lanes 9 and 10; see also B and C). In the absence of repressor in vitro, the intensities of these bands are essentially equal, indicating near-identical accessibility to DMS (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 and 9, and B). Quantification of the results in lane 3 showed that the DMS reactivities of the guanines at positions 2 and 5′ were 2-fold lower than that at position 1′ (Fig. 3C). This finding suggests that at the level of 933W repressor found in the λimm933W lysogen, OR3 is partially occupied by the 933W repressor. Consistent with this suggestion, the reactivities of the bases at positions 2 and 5′ were reduced by an additional 2-fold when cells were transformed with a plasmid that directs synthesis of an additional amount of 933W repressor (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 5 and 6). Moreover, in the presence of the excess repressor, the levels of DMS reactivity of position 2 and 5′ guanines were reduced to the same level as that seen when this DNA reacted with DMS in the presence of saturating levels of 933W repressor in vitro (see Fig. 5B and C, below).

Importantly, we found that both the pattern and degree of protection of the bases in OR3 in the λimm933WΔOL lysogen are identical to that seen in the λimm933W lysogen (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3 and 5, and B and C). This result indicated that the absence or presence of the OL region has no effect on the ability of the 933W repressor to occupy OR3 in vivo at the levels of repressor found in a lysogen. We also found that the degree to which excess (plasmid-derived) repressor enhanced the protection of the guanines at positions 2 and 5′ inside λimm933WΔOL lysogens was identical to that found with the λimm933W lysogen (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results show that 933W repressor binding to sites in OL does not influence repressor occupancy of OR3. These observations are consistent with the suggestion that a repressor-mediated DNA loop between OL and OR does not form in bacteriophage 933W. The DMS modification patterns in the region around OR1 and OR2 obtained in vitro differ slightly from those found in vivo. We suspect these differences do not stem from differences in repressor occupancy under these two conditions, but rather arise from the partial occupancy of this region by RNA polymerase bound at PR and/or PRM. Regardless, inspection of the results shown in Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 6, shows that the DMS modification pattern of these sites was unaffected by the absence or presence of OL, indicating deletion of OL does not affect 933W repressor binding to these sites. This finding is consistent with our observation that deletion of OL does not affect repressor occupancy of OR3.

PRM transcriptional activity is not dependent on OL.

To further examine the potential role of OL-bound 933W repressor on OR3 occupancy, we determined if the presence or absence of the OL region affected the transcriptional activity of PRM in vivo. For these experiments, we compared the amount of PRM transcript produced in both the λimm933W and λimm933WΔOL lysogens in the absence and presence of additional 933W repressor.

Quantification of PRM transcripts found in λimm933W and λimm933WΔOL showed that the differences in the steady-state amounts of PRM-derived mRNA in these two lysogens were statistically insignificant (P = 0.34) (Fig. 4). Production of additional 933W repressor inside each of these lysogens repressed PRM transcript levels by an identical amount (Fig. 4). Since repressor occupancy of OR2 and OR3 positively and negatively regulates PRM activity, respectively (see Fig. 7, below), these results showed that OL has no effect on repressor occupancy of OR2 and OR3. These findings are completely consistent with the results of our in vivo DMS footprinting study (Fig. 3), which showed that deletion of the repressor binding sites in OL did not have any effect on 933W repressor occupancy of OR3. These observations do differ dramatically from what was found with bacteriophage λ. In that case, deletion of λ repressor binding sites in λOL increased transcription from λPRM as a consequence of the decreased occupancy of λOR3 by 2- to 3-fold (3, 13). Thus, our results show that occupancy of the binding sites in 933W OR by the 933W repressor is by interactions between repressors bound at OR and OL.

Fig. 4.

Deletion of 933W OL does not affect in vivo levels of PRM transcripts. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to determine PRM cDNA levels produced from reverse transcription of total RNA extracted from λimm933W and λimm933WΔOL lysogens producing wild-type levels of 933W repressor (containing pET17b and pGP1-2) or excess 933W repressor (+++-containing p933WR and pGP1-2). Amounts of PRM transcripts were normalized to the amount of UmuC transcripts, determined in parallel reverse transcription reactions (see Materials and Methods). Differences between the amounts of transcript without or with excess repressor were significant (P < 0.0001). The amount of transcripts from OL+ and ΔOL lysogens were not significantly different (P = 0.34), regardless of the absence or presence of the repressor-producing plasmid. Data are derived from eight replicate experiments.

Fig. 7.

OR2 and OR3 are required for regulation of PRM transcription by repressor. (A) Representative transcription gels. 933W DNA templates containing wild-type (wt) OR or OR regions bearing mutations in either OR2 (OR2−) or OR3 (OR3−) were transcribed in vitro in the absence of repressor (lane 1) and at repressor concentrations increased in 2-fold steps (lanes 2 to 7), starting with 4.5 nM protein. Positions of transcripts initiated from PR and PRM are indicated. The 933W repressor was incubated with DNA template at 25°C for 10 min, followed by addition of E. coli RNA polymerase. The reaction mixture was transferred to 37°C for 10 min before the transcription reaction was initiated by the addition of nucleotides and heparin. (B) Graphical representation of the amount of PRM transcript synthesized as a function of 933W repressor concentration from the template bearing wild-type OR or templates bearing a mutation in OR3 or OR2. The transcript amounts are quantified as a percentage of maximal PR transcription as a function of 933W repressor concentration. Error bars represent standard deviations calculated from the averages of at least three replicate experiments. (C) Numerical simulation of transcription data using OR occupancy data calculated from dissociation constants given in Fig. 5 (see also Materials and Methods). The lines represent simulated data. Points are the measured PRM activity, as described for panel B.

Affinities of the 933W repressor for naturally occurring 933W OR binding sites in separate sites and intact OR.

In the absence of OL-mediated regulation of OR3 occupancy, how then might the UV threshold response of bacteriophage 933W (Fig. 2) be determined? To begin to answer this question, we measured the affinity of the 933W repressor for its naturally occurring sites in OR and OL, both on the individual sites and in the context of the intact operator. The intrinsic affinity of the 933W repressor for the individual sites was measured in an electrophoresis mobility shift assay. Figure 5 shows that the 933W repressor displayed a hierarchy of affinities for the sites in OR, as it bound with highest affinity to OR1 and with ∼100- and 15-fold-lower affinities to OR2 and OR3, respectively. The differences in affinities of the 933W repressor for OR1, OR2, and OR3 were significant (P ≤ 0.005), and the relative affinities of the 933W repressor for its sites in OR were qualitatively and quantitatively different than what was seen with other well-studied lambdoid bacteriophage repressors, e.g., λ (OR1 of 1, OR2 of 75, and OR3 of 30), 434 (OR1 of 1, OR2 of 14, and OR3of 5.5), and P22 (OR1 of 1, OR2 of 14, and OR3 of 6) (5, 6, 19, 21, 33, 34, 37).

Our previously reported DNase I footprinting results also suggested that the 933W repressor does not bind cooperatively to OR1 and OR2 when these sites are present within intact OR (23). However, the conditions under which those experiments were performed are not directly comparable to those used in the EMSA determinations reported here. Also, those experiments were performed at concentrations of DNA that, based on the data in Fig. 5, were either within or near the stoichiometric range for repressor binding to OR1 and OR2, respectively. Therefore, we repeated the footprinting experiments under conditions identical to those used in the EMSA determinations (i.e., low DNA concentration and absence of competitor DNA) to provide a comparable measure of the affinities of 933W repressor for its individual sites in intact OR. Unlike the case with other lambdoid bacteriophage repressors, the 933W repressor binds the three sites in intact OR at distinctly different concentrations (Fig. 6). The dissociation constants deduced from a series of footprinting experiments were as follows: OR1, 0.22 nM; OR2, 3.0 nM; OR3, 5.8 nM (± ∼20%). Hence, the affinities of the 933W repressor for OR1, OR2, and OR3 in intact OR are essentially identical to the affinities of the 933W repressor for the individual, separated sites shown in Fig. 5. The similarities between 933W repressor affinities for the separated sites and the sites present in intact OR led us to modify our earlier suggestion that the 933W repressor may bind with weak cooperativity to adjacent sites within the intact operators (23). Instead, our data indicate that the 933W repressor does not cooperatively bind to adjacent sites in OR.

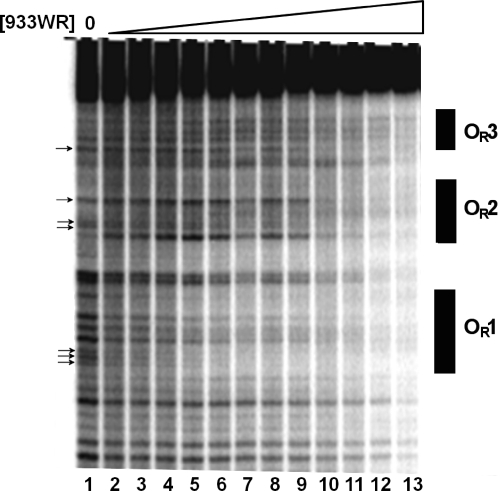

Fig. 6.

DNase I footprinting of complexes between the 933W repressor and 933W OR. Shown is a representative phosphorimage of a representative gel. DNA templates containing 933W OR radioactively labeled were partially digested with DNase I in the presence of increasing amounts of the 933W repressor. Lane 1 shows the DNase I cleavage pattern of the DNA in the absence of added repressor. In lanes 2 to 13, repressor concentrations were increased in 1.5-fold steps starting at 0.17 nM protein. The arrows identify positions of protected bands used in measuring site occupancies of OR1, OR2, and OR3.

Our measurements revealed that the 933W repressor binds to OL1 and OL2 with similar affinities (Fig. 5). We showed previously that in intact 933W OL, the 933W repressor binds its respective OL1 and OL2 with nearly equal affinity (23). Similar measurements under comparable conditions to our EMSA studies confirmed this finding (data not shown). Thus, the equal affinities of 933W repressor for OL1 and OL2 seen in intact OL are apparently not a result of cooperative binding by this protein.

Regardless of whether 933W repressor binds DNA cooperatively, our data confirm the earlier finding that its affinities for OR2 and OR3 differ by 1.5- to 2-fold. This observation provides a potential explanation as to how the UV threshold in bacteriophage 933W is generated. Instead of being regulated by a long-range loop, 933W repressor occupancy of the sites in OR is instead governed solely by the intrinsic affinities of the repressor for the individual sites in OR.

Positive and negative regulation of PRM transcription by the 933W repressor.

To further explore how the small differences in the 933W repressor's intrinsic affinities for sites in OR might contribute to the UV threshold, we determined how the bacteriophage 933W repressor regulates transcription from PRM. In vitro transcription analysis of a 933W wild-type OR template, containing the 933W OR region and its PR and PRM promoters, showed that in the absence of 933W repressor, no PRM transcript was observed, while PR was robustly transcribed. As the 933W repressor concentration was increased to up to ∼30 nM, an increasing amount of PRM transcript was synthesized and transcription of PR was repressed (Fig. 7). Transcription from PRM was inhibited as the concentration of 933W repressor was increased from 30 nM to 120 nM (Fig. 7). Consistent with previous observations (23), these findings indicate that, similar to other bacteriophage repressors, the 933W repressor both activates and represses PRM transcription and functions as a repressor of PR transcriptional activity.

In the other well-studied bacteriophages, the repressor-OR2 complex is needed to activate transcription of PRM. To investigate the role of the 933 repressor-OR2 complex in stimulating 933W PRM transcription, we created a transcription template bearing two base substitutions in OR2 at positions 5′ and 4′ (G5′T4′ → T5′C4′) (see Fig. 1 for wild-type sequences). Control experiments established that these sequence changes prevented 933W repressor binding to OR2, without detectably altering binding of this protein to OR1 or OR3 or the concentration of repressor needed to repress PR transcription (data not shown). As opposed to the case with wild-type template, 933W repressor was incapable of activating PRM transcription from the OR2− template in vitro (Fig. 7A). This finding showed that, similar to other lambdoid phages, a 933W repressor bound to OR2 is needed to activate transcription from PRM.

In all other bacteriophages, the repressor-OR3 complex inhibits transcription initiated at PRM. We investigated the mechanism by which the 933W repressor negatively regulates PRM, and thus its own synthesis, by examining the effects of mutations that prevent 933W repressor binding to OR3 on PRM transcription in vitro. Mutations that blocked 933W repressor binding to OR3 prevented the 933W repressor from repressing transcription from PRM (Fig. 7A). These results show that 933W repressor binding to OR3 mediates repression of transcription from PRM.

Our results show that the effects of 933W repressor binding to OR2 and OR3 on PRM transcriptional activity are similar to those seen in other bacteriophages. However, inspection of the results shown in Fig. 7 reveals that the activity of 933W PRM, in response to varied 933W repressor concentrations, differs considerably from that seen in other lambdoid bacteriophages. In 933W, the maximal repressor-stimulated PRM transcription from the OR3− template was nearly 4-fold higher than that observed from the wild-type template. In contrast, in bacteriophage λ, the maximal amount of repressor-stimulated PRM transcript obtained on wild-type and OR3− templates is the same (17, 28). Similar results were obtained with bacteriophage 434 (10, 42). Based on the observation that the 933W repressor affinity for OR2 is less than 2-fold higher than its affinity for OR3 (Fig. 5), the results in Fig. 7A indicate that at 933W repressor concentrations needed to completely occupy OR2, the 933W repressor partially occupies OR3. This conclusion was verified by accurately simulating these transcription results, using operator occupancy data derived from the dissociation constants shown above (Fig. 7C).

On the wild-type OR template, complete repression of PRM transcription occurred with the addition only 4-fold more 933W repressor than is needed maximally for this promoter (Fig. 7). The difference in 933W repressor concentration needed to activate versus repress PRM transcription was much lower than that seen in other lambdoid phages. In bacteriophage λ, >20-fold more λ repressor is required to repress PRM transcription from an OR template than is needed to maximally stimulate this promoter's activity (17, 29). Similar results were obtained with bacteriophage 434 (10, 43).

DISCUSSION

Our data clearly show that in vivo, deletion of the 933W OL region does not influence repressor occupancy of OR3 or the activity of the PRM promoter. Hence, bacteriophage 933W regulates PRM activity, and therefore repressor levels, by a mechanism that apparently does not involve long-range cooperative interactions between 933W repressors. Had a long-range DNA loop formed in 933W and had such a loop been required for modulating 933W repressor occupancy of sites in OR, we would also have anticipated that the affinities of 933W repressor for the sites in OL should be equal to or greater than its affinities for OR1 and OR2. However, the intrinsic affinities of 933W repressor for OL1 and OL2 were ≥7-fold lower than its affinities for OR1 (Fig. 5). It is possible that 933W repressor binding at OL1 and OL2 stabilizes 933W repressor binding at OR. However, this view is inconsistent with the finding that deletion of OL apparently does not impact 933W repressor occupancy of any sites in OR (Fig. 3).

How then does bacteriophage 933W regulate repressor levels so that it can form a stable and yet inducible lysogen? In general, 933W repressor-mediated regulation of PRM activity in bacteriophage 933W employs a strategy similar to that of other lambdoid phages. Like those phages, 933W repressor bound to OR2 is responsible for activation of PRM, and repressor bound to OR3 is required for repression. However, unlike other lambdoid phages, in bacteriophage 933W negative regulation of PRM transcriptional activity by the repressor is governed solely by differences in the 933W repressor's intrinsic affinities OR2 and OR3. The ∼2-fold difference between the affinities of 933W repressor for 933W OR2 and 933W OR3 (as opposed to the 15- to 30-fold differences in affinities of the λ repressor for λOR2 and λOR3 in intact λ OR) results in tight repressor autoregulation of PRM activity. The small differences in relative affinities of the 933W repressor for 933W OR2 and 933W OR3 are sufficient to allow repressor occupancy at OR3 in vivo for negative regulation of PRM in 933W. That is, the closely matched affinities of OR2 and OR3 allow for the counterbalancing of the autogenous positive- and negative-control activities of the 933W repressor-DNA complexes formed at 933W OR2 and 933W OR3, respectively, on the transcriptional activity of PRM.

Interestingly, repression of 933W PRM transcription in vitro, which is mediated by the 933W repressor binding to OR3, occurs at 933W repressor concentrations where full occupancy of OR2, and thus maximal activation of PRM transcriptional activity, has not yet been reached. Furthermore, complete repression of PRM occurs at levels of repressor that are only 4-fold higher than is needed for activation, further arguing for the partial occupancy of OR3 at concentrations where OR2 is not yet completely filled. The lack of repressor-mediated interactions between OL and OR suggests that the in vitro transcription findings accurately represent the situation in vivo.

The narrow range of 933W repressor concentrations needed to activate and repress 933W PRM transcription is strikingly different from that seen in vitro with other lambdoid phages. In bacteriophages λ and 434, repression of PRM (via occupancy of OR3) does not occur until a repressor concentration at which PRM is fully activated (or OR2 is maximally filled) is reached. This is because in these bacteriophages, at least 20-fold more repressor is required to fully repress PRM than that needed to maximally stimulate transcription. Therefore, in both λ and 434 bacteriophages, the activity of maximal repressor-stimulated PRM activity on wild-type OR and OR3 mutant templates, where repressor cannot repress PRM transcription, is essentially identical (10, 29).

It is important to note that to enable repression of PRM in vivo, the weak intrinsic affinity of λ repressor for OR3 must be overcome by the long-range DNA loop mediated by repressor bound at OL and OR sites (15). As a consequence, repression of PRM in bacteriophage λ in vivo requires only 4-fold more λ repressor than is needed for activation, as opposed to the ≥20-fold needed in vitro (15, 29). Therefore, the range of λ repressor concentrations needed to activate and repress λ PRM in vivo transcription matches that seen for 933W. However, as a consequence of the cooperative binding of λ repressor to OR1 and OR2, repressor-stimulated transcriptional activity of PRM in vivo reaches >70% of the maximum amount seen in an OL3− or OR3− λ bacteriophage. Hence, in λ, repression of PRM only occurs at repressor concentrations higher than where PRM is essentially fully activated. This observation contrasts with our findings for intact 933W OR, where PRM reached only ∼25% of the maximum activation possible.

The narrow window of repressor concentrations between the amount needed to activate versus repress 933W PRM transcription explains why 933W bacteriophage displays a “threshold response” to DNA damage. The observation of a threshold response has been attributed to the response of PRM activity to various levels of repressor. As discussed above, in both 933W and λ lysogens, the transcriptional activity of PRM is partially repressed due to partial occupancy of OR3 by repressor. At low UV doses, as a consequence of RecA-mediated repressor degradation, OR3 occupancy decreases, leading to increased PRM activity and a consequent increase in repressor levels. At high UV doses, the rate of RecA-mediated repressor degradation exceeds the rate of new repressor synthesis, and the repressor concentration falls below the level needed to occupy OR1 and OR2, leading to lysogen induction. Hence, the key feature of the threshold response is partial occupancy of OR3 by the repressor. In bacteriophage λ, OR3 binding is facilitated by a repressor-mediated loop between OL and OR that allows an OL3-bound repressor to closely approach OR3 and to help a repressor bind that site via cooperative interactions that are thought to mimic those used by λ repressor bound at adjacent sites (3). In bacteriophage 933W, OR3 occupancy is facilitated by the closely matched affinities of 933W repressor for the binding site that activates (OR2) and the one that represses (OR3) PRM transcription.

This proposed strategy for generating a UV threshold response in bacteriophage 933W not only eliminates the need for long-distance cooperative interactions between two DNA-bound repressor tetramers but also the subsequent role for cooperative binding between spatially adjacent OR3- and OL3-bound repressor dimers in the looped complex. Since the interaction between repressors bound at OR3 and OL3 is anticipated to use the “side-by-side” cooperativity interface, this conclusion is consistent with the indication that the 933W repressor is incapable of cooperatively binding to adjacent sites on OR (Fig. 5 and 6). Together with the fact that bacteriophage 933W forms stable lysogens, this suggestion indicates that the ∼9-fold difference in relative affinity of the 933W repressor for OR2 and OR1 is sufficient to enable efficient occupancy of OR2 and positive regulation of PRM in the absence of side-by-side cooperative repressor interactions. In contrast, the λ phage repressor's intrinsic affinity for OR1 is 30 times higher than its affinity for OR2 (21, 22, 34). It is known that efficient occupancy of OR2 in wild-type λ phage, and therefore stable λ lysogen formation, requires cooperative repressor binding to OR1 and OR2 (2, 11).

The different levels of maximal PRM activity in vivo in λ and 933W bacteriophages and the apparent inability of the 933W repressor to cooperatively bind adjacent sites may help explain the observation that 933W lysogens behave as a “hair trigger,” i.e., the frequency of DNA damage-independent (spontaneous) induction is much higher in 933W than in other related bacteriophages (26). The increased induction frequency in these stx-encoding phages has been attributed to the requirement for a lower concentration of active RecA necessary for induction (26). The critical level of RecA needed for induction of 933W phage could be determined by an increased sensitivity of the 933W repressor to RecA, a decrease in the strength of the 933W repressor's binding interactions with its operators, and/or a decreased total amount of 933W repressor present in the lysogen.

Our findings show that the absolute affinities of the 933W repressor for its DNA sites are not dramatically different than the affinities of other lambdoid phage repressors for their cognate operators (Fig. 5). We have not directly assessed the sensitivity of 933W to RecA-mediated autocleavage. Results of in vitro transcription assays indicated that the maximal activity of 933W repressor-stimulated PRM is 60% of the value of PR (Fig. 7), whereas similar experiments have indicated that the maximal activity of λ repressor-stimulated PRM is ∼3-fold lower, i.e., ∼20% of λ PR activity (18, 39, 41). Our data also indicate that the in vivo activity of 933W PRM is only 25% of its maximal level. Together these observations suggest that the amount of repressor is lower in 933W lysogens than in λ lysogens. Therefore, the increased sensitivity of 933W lysogens to spontaneous induction could be due, at least in part, to a smaller amount of repressor in the 933W lysogen than in λ lysogens.

Babić and Little (2) were able to isolate cis-acting mutants that allow a λ bacteriophage encoding a repressor that is incapable of cooperatively forming DNA-bound tetramers to form stable lysogens. The mutant phages identified by Babić and Little compensated for the repressor cooperativity defect, in part, by increasing the relative affinity of OR2 for the λ repressor. We showed here that the affinity of the 933W repressor for its OR2 is 4- to 6-fold higher, relative to 933W OR1, than seen in wild-type λ. Therefore, the compensatory OR2 mutation found in the mutant λ phages mimics a key native feature of the 933W bacteriophage lysis-lysogeny circuitry.

The increased affinity of repressor for OR2 in the mutant λ phage creates a scenario where, akin to bacteriophage 933W, the λ repressor binds OR3 and the mutant OR2 with similar affinities. Consequently, the smaller difference between OR2 and OR3 affinities would mean that at λ repressor concentrations where full occupancy of OR2 has not yet been reached, OR3 would be partially occupied, and thus PRM partially repressed. With PRM partially repressed, the mutant λ phage requires a more active PRM promoter to maintain required levels of λ repressor to form stable lysogens. This observation is consistent with the inference that the maximal stimulated activity of 933W PRM is greater than that of wild-type λPRM.

The 933W repressor is apparently unique among the lambdoid bacteriophage repressors in its native inability to bind cooperatively to either adjacent or widely separated sites. The C-terminal domain (CTD) of lambdoid phage repressors is responsible for mediating any cooperative binding (30). We hypothesize that the 933W repressor is incapable of binding DNA cooperatively due to critical sequence differences between its CTD and the CTDs of other lambdoid repressors. A sequence comparison of phage repressor CTDs revealed only a weak (10 to 11%) similarity between the sequence of the 933W CTD and those of λ, 434, and P22 phages (Fig. 8), In contrast, the sequences of the CTDs of λ, 434, and P22 were highly similar (36 to 60%) to each other. Strikingly, the sequence alignment showed many of the λ repressor residues found in the tetramer interface and those tested for mediating cooperative interactions, such as E188, K192, S198, G199, Q209, Y210, and M212, differ from those in analogous positions in 933W in terms of both identity and character (4, 7–9, 38). In contrast, most of the residues in these regions of the 434 and P22 CTDs, which are known to bind DNA cooperatively, are similar to those found in the λ repressor. Hence, we suggest that these sequence differences underlie the inability of the 933W repressor to cooperatively bind DNA.

Fig. 8.

Alignments of the CTDs of the 933W repressor with three other lambdoid phage repressors known to cooperatively bind DNA. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW (24). Shaded boxes were used to demonstrate the output based on residue matches (black) and functional similarities (gray). This program was written by Kay Hofmann and Michael D. Baron. Numbers indicate the residue within the protein that defines the beginning of the CTD. Black dots indicate residues in the λ repressor that contribute to cooperative interactions between repressor dimers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The work described in the paper was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (MCB-0956454) to G.B.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arber W., et al. 1983. Lambda II, p. 433–466 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Babić A. C., Little J. W. 2007. Cooperative DNA binding by cI repressor is dispensable in a phage lambda variant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17741–17746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baek K., Svenningsen S., Eisen H., Sneppen K., Brown S. 2003. Single-cell analysis of lambda immunity regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 334:363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beckett D., Burz D. S., Ackers G. K., Sauer R. T. 1993. Isolation of lambda repressor mutants with defects in cooperative operator binding. Biochemistry 32:9073–9079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beckett D., Koblan K. S., Ackers G. K. 1991. Quantitative study of protein association at picomolar concentrations: the lambda phage cI repressor. Anal. Biochem. 196:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bell A. C., Koudelka G. B. 1993. Operator sequence context influences amino acid-base-pair interactions in 434 repressor-operator complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 234:542–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell C. E., Frescura P., Hochschild A., Lewis M. 2000. Crystal structure of the lambda repressor C-terminal domain provides a model for cooperative operator binding. Cell 101:801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benson N., Adams C., Youderian P. 1994. Genetic selection for mutations that impair the co-operative binding of lambda repressor. Mol. Microbiol. 11:567–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burz D. S., Ackers G. K. 1994. Single-site mutations in the C-terminal domain of bacteriophage lambda cI repressor alter cooperative interactions between dimers adjacently bound to O R. Biochemistry 33:8406–8416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bushman F. D. 1993. The bacteriophage 434 right operator. Roles of OR1, OR2 and OR3. J. Mol. Biol. 230:28–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cao Y., Lu H.-M., Liang J. 2010. Probability landscape of heritable and robust epigenetic state of lysogeny in phage lambda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:18445–18450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dodd I. B., Perkins A. J., Tsemitsidis D., Egan J. B. 2001. Octamerization of lambda cI repressor is needed for effective repression of PRM and efficient switching from lysogeny. Genes Dev. 15:3013–3022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dodd I. B., Shearwin K. E., Egan J. B. 2005. Revisited gene regulation in bacteriophage lambda. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15:145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dodd I. B., et al. 2004. Cooperativity in long-range gene regulation by the lambda cI repressor. Genes Dev. 18:344–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fattah K. R., Mizutani S., Fattah F. J., Matsushiro A., Sugino Y. 2000. A comparative study of the immunity region of lambdoid phages including Shiga-toxin-converting phages: molecular basis for cross immunity. Genes Genet. Syst. 75:223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawley D. K., Johnson A. D., McClure W. R. 1985. Functional and physical characterization of transcription initiation complexes in the bacteriophage lambda OR region. J. Biol. Chem. 260:8618–8626 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hershberger P. A., DeHaseth P. L. 1993. Interference by PR-bound RNA polymerase with PRM function in vitro. modulation by the bacteriophage l cI protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268:8943–8948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hilchey S. P., Wu L., Koudelka G. B. 1997. Recognition of nonconserved bases in the P22 operator by P22 repressor requires specific interactions between repressor and conserved bases. J. Biol. Chem. 272:19898–19905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson A. D., et al. 1981. Lambda repressor and cro: components of an efficient molecular switch. Nature 294:217–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koblan K. S., Ackers G. K. 1991. Cooperative protein-DNA interactions: effects of KCl on lambda cI binding to OR. Biochemistry 30:7822–7827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koblan K. S., Ackers G. K. 1991. Energetics of subunit dimerization in bacteriophage lambda cI repressor: linkage to protons, temperature, and KCl. Biochemistry 30:7817–7821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koudelka A. P., Hufnagel L. A., Koudelka G. B. 2004. Purification and characterization of the repressor of the Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophage 933W: DNA binding, gene regulation, and autocleavage. J. Bacteriol. 186:7659–7669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Larkin M. A., et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Little J. W., Shepley D. P., Wert D. W. 1999. Robustness of a gene regulatory circuit. EMBO J. 18:4299–4307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livny J., Friedman D. I. 2004. Characterizing spontaneous induction of Stx encoding phages using a selectable reporter system. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1691–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Messing J. 1983. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Methods Enzymol. 101:20–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meyer B. J., Maurer R., Ptashne M. 1980. Gene regulation at the right operator (OR) of bacteriophage lambda. II. OR1, OR2, and OR3: their roles in mediating the effects of repressor and cro. J. Mol. Biol. 139:163–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meyer B. J., Ptashne M. 1980. Gene regulation at the right operator (OR) of bacteriophage lambda. III. lambda repressor directly activates gene transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 139:195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ptashne M. 1986. A genetic switch. Blackwell Press, Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]

- 31. Revet B., Wilcken-Bergmann B., Bessert H., Barker A., Muller-Hill B. 1999. Four dimers of lambda repressor bound to two suitably spaced pairs of lambda operators form octamers and DNA loops over large distances. Curr. Biol. 9:151–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rex J. H. 2000. Purification of genomic DNA from gram-negative bacteria. Focus 22:26–27 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Senear D. F., Ackers G. K. 1990. Proton-linked contributions to site-specific interactions of lambda cI repressor and OR. Biochemistry 29:6568–6577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Senear D. F., Batey R. 1991. Comparison of operator-specific and nonspecific DNA binding of the lambda cI repressor: [KCl] and pH effects. Biochemistry 30:6677–6688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tabor S., et al. 1990. Expression using the T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system, p. 16.2.1–16.2.11 Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing and Wiley-Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tyler J. S., Mills M. J., Friedman D. I. 2004. The operator and early promoter region of the Shiga toxin type 2-encoding bacteriophage 933W and control of toxin expression. J. Bacteriol. 186:7670–7679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wharton R. P., Brown E. L., Ptashne M. 1984. Substituting an α-helix switches the sequence specific DNA interactions of a repressor. Cell 38:361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whipple F. W., Hou E. F., Hochschild A. 1998. Amino acid-amino acid contacts at the cooperativity interface of the bacteriophage lambda and P22 repressors. Genes Dev. 12:2791–2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Whipple F. W., Ptashne M., Hochschild A. 1997. The activation defect of a lambda cI positive control mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 265:261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wood W. B. 1966. Host specificity of DNA produced by Escherichia coli: bacterial mutations affecting the restriction and modification of DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 16:118–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Woody S. T., Fong R. S. C., Gussin G. N. 1993. Effects of a single base-pair deletion in the bacteriophage lambda P RM promoter. Repression of PRM by repressor bound at OR2 and by RNA polymerase bound at PR. J. Mol. Biol. 229:37–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu J., Koudelka G. B. 1998. DNA-based positive control mutants in the binding site sequence of 434 repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24165–24172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xu J., Koudelka G. B. 2001. Repression of transcription initiation at 434 P(R) by 434 repressor: effects on transition of a closed to an open promoter complex. J. Mol. Biol. 309:573–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]