Abstract

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is a spirochetal disease caused by at least 15 different Borrelia species. It is a serious human health concern in regions of endemicity throughout the world. Transmission to humans occurs through the bites of infected Ornithodoros ticks. In North America, the primary Borrelia species associated with human disease are B. hermsii and B. turicatae. Direct demonstration of the role of putative TBRF spirochete virulence factors in the disease process has been hindered by the lack of a genetic manipulation system and complete genome sequences. Expanding on recent developments in these areas, here we demonstrate the successful generation of a clone of B. hermsii YOR that constitutively produces green fluorescent protein (GFP) (B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp). This strain was generated through introduction of a kan-gfp cassette into a noncoding region of the 200-kb B. hermsii linear plasmid lp200. Genetic manipulation did not affect the growth rate or trigger the loss of native plasmids. B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp retained infectivity and elicited host seroconversion. Stable production of GFP was demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo. This study represents a significant step forward in the development of tools that can be employed to study the virulence mechanisms of TBRF spirochetes.

INTRODUCTION

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is a zoonotic infection transmitted to humans by infected Ornithodoros ticks (11, 13, 17). Fifteen different Borrelia species have been identified as etiological agents of TBRF (26, 27). TBRF is a significant human health concern in regions of endemicity throughout the world. Its impact is most dramatically felt in parts of Africa (Tanzania, Ethiopia, Senegal, Mauritania, and Mali) where it is the most common cause of fever, surpassing even malaria (5, 7, 18, 35). In North America, TBRF occurs in the West as a sporadic disease caused by Borrelia hermsii and Borrelia turicatae (3, 8, 12, 31, 33, 34). The relapsing fever episodes that are a hallmark of this infection coincide with the emergence of high-density, antigenically distinct populations of spirochetes in the blood (1, 6, 11).

The first demonstration of genetic manipulation of a Borrelia species was in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (30). While relatively standard methods were employed to introduce DNA by electroporation, large amounts of DNA were required to overcome low transformation efficiency. An important and confounding factor in the genetic manipulation of B. burgdorferi is the loss after electroporation of endogenous plasmids that encode proteins required for survival in either tick or mammalian hosts. Hence, the plasmid content of each transformant must be determined prior to further analyses. To date, there is only a single report, by Battisti et al., of site-directed allelic exchange in a TBRF species (2). Battisti and colleagues inactivated the vtp gene, which encodes the variable tick protein (Vtp). While Vtp was found to be nonessential for infectivity in mammals, this earlier report served as the first demonstration that foreign DNA can be introduced in a site-specific manner into a TBRF spirochete. There have been no additional reports of genetic manipulation of B. hermsii, and diverse tools for this purpose are lacking. Recent determinations of linear chromosome sequences of B. hermsii (genomic group I DAH isolate), Borrelia recurrentis, Borrelia duttonii, and Borrelia turicatae (21) will facilitate future analyses. Unfortunately, assembled, annotated, and complete sequences for plasmid components of these genomes have not yet been determined.

In this study, we have developed additional tools that can be used to study B. hermsii virulence mechanisms. An infectious clone of B. hermsii YOR (a genomic group II isolate) that harbors a selectable marker (kan) and produces green fluorescent protein (GFP) was generated. The resulting clone (B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp) was unaltered in its growth characteristics, retained all essential plasmids, and constitutively produced GFP in vitro and during infection in mice. This is the first report to demonstrate site-specific allelic exchange in a genomic group II B. hermsii strain and to generate a fluorescently labeled strain of a TBRF spirochete. This strain can serve as a parental, labeled strain for the introduction of other site-directed mutations and can be tracked and studied in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultivation.

B. hermsii YOR (an isolate derived from a human TBRF patient in the United States) is an extensively characterized genomic group II strain (14, 15, 32). B. hermsii was cultivated in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly-H (BSK-H) complete medium supplemented with 12% rabbit serum (37°C; 5% CO2) in sealed bottles (9). Antibiotic selection of transformants was achieved with kanamycin (200 μg ml−1).

Vector construction and electroporation.

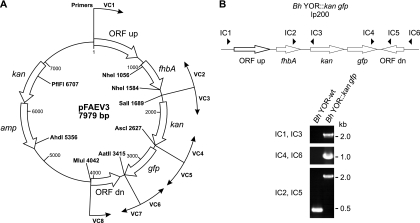

A suicide vector, designated pFAEV3, was designed to allow stable integration of a kanamycin resistance (kan) cassette and gfp into a noncoding region of lp200. The integration site resides between the 3′ end of fhbA and the 3′ end of an oppositely oriented hypothetical open reading frame (labeled as ORF dn in Fig. 1). Plasmids were constructed using the pCR2.1 vector backbone (Invitrogen). Regions of lp200 and the gfp and kan genes were PCR amplified from previously constructed plasmids. Appropriate restriction sites were incorporated into the primers, as needed, to allow for subsequent cloning procedures (Table 1). In brief, a 1,689-bp region of lp200 was amplified from an existing plasmid using the VC1 and VC2 primers. This amplicon extends from upstream of fhbA to 3′ of its coding sequence and terminates with a SalI site. A second, 627-bp amplicon spanning ORF dn was amplified from an existing plasmid using the VC8 and VC7 primers (with MluI and AatII restriction sites, respectively). The kan gene, linked to the constitutively active B. hermsii DAH flgB promoter (PflgB-kan), was amplified from pTABhFlgB-Kan (2) (kindly provided by T. Schwan) using the VC3 and VC4 primers (with SalI and AscI sites, respectively). gfp was amplified from pCE320 (10) (kindly provided by J. Radolf) using the VC5 and VC6 primers (with AscI and AatII sites, respectively). The kan and gfp genes were linked to allow for expression from the kan cassette. The two genes are separated by 60 bp of sequence derived from the region upstream of the gfp gene. Through standard subcloning approaches, the amplicons were ligated to yield the final vector, pFAEV3. This plasmid was propagated in NovaBlue Escherichia coli cells (Novagen), purified (HiSpeed plasmid Midi kit; Qiagen), and linearized with AhdI and PflFI prior to transformation.

Fig. 1.

B. hermsii pFAEV3 suicide vector map and PCR-based verification of allelic exchange. A suicide vector (pFAEV3) was constructed to allow for the introduction of a selectable marker (kan) and a green fluorescent protein (gfp) gene into a noncoding region of the native B. hermsii linear plasmid lp200. (A) The vector map is depicted. The primers used to generate the amplicons for vector construction (VC) are indicated. (B) Schematic depicting lp200 after cassette integration. The location of the primer targets for PCR used to confirm integration (IC primers) are indicated. The ethidium bromide-stained amplicons obtained through the PCR analyses are also shown. Primer sequences can be found in Table 1. Bh, B. hermsii; wt, wild type.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| VC1 | GTCAATGGTATATTAGTTTCAAGTTCTATGACCC |

| VC2 | ACGCGTAAAGTCGACTTAACATATAAATAATACTGATATTAAAATTTATGTAAA |

| VC3 | GTCGACGTTAAAGAAAATTGAAATAAACTTGGACTATGTTAATG |

| VC4 | GGCGCGCCTTAGAAAAACTCATCGAGCATCAAATG |

| VC5 | GGCGCGCCGGGCGAATTCGGCTTATTCC |

| VC6 | GACGTCCTATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGTG |

| VC7 | GACGTCCCTGAGAGTATAGGCAGTACTTCAATTACTACC |

| VC8 | ACGCGTCAATTGATATTGATGTGGCGTTGATTTCTAAAATAG |

| IC1 | GTCTACTCTATCTGGGATACTAAAGAGC |

| IC2 | CAAATTTCAATGACTTGCAAAATTTAGAGC |

| IC3 | CATCATTGGCAACGCTACC |

| IC4 | GTCCACACAATCTGCCCTTTC |

| IC5 | ATTGCATTAAGTTATGCAGATAAATTTAAGC |

| IC6 | GCATTAAGTAAGCGGTTTGTGAGC |

Abbreviations used in primer designations are as follows: VC, vector construction, and IC, insert confirmation. Restriction site tails are indicated by underlining.

Electroporation conditions were adapted from methods originally developed by Samuels et al. for B. burgdorferi (30). In brief, B. hermsii YOR cells were harvested from a 100-ml, mid-log-phase culture by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C), washed 3 times with cold EPS buffer (93 mg ml−1 sucrose, 15% glycerol), and suspended in 100 μl EPS buffer containing 25 μg of linearized pFAEV3. After 5 min on ice, the cells were electroporated (0.2-cm cuvette, 2.5 kV, 25 mF, 200 W), transferred to 10 ml of BSK-H medium with 12% rabbit serum, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The culture volumes were increased to 50 ml with fresh BSK-H medium and supplemented with kanamycin (200 μg ml−1). Cultures were maintained at 37°C, and growth was monitored by dark-field microscopy. To obtain clonal populations, serial dilutions of the cultures were made in tissue culture plates containing BSK-H medium (200 μl) with 200 μg ml−1 kanamycin. The plates were sealed with adhesive plate covers (EdgeBio) and incubated at 37°C (5% CO2). Growth was monitored by dark-field microscopy.

Growth curve analyses.

Growth rates were determined as previously described (28). In brief, fresh medium was seeded with the same number of actively growing cells of each strain. The cultures were maintained at 37°C, and cell counts were conducted daily for 7 days using dark-field microscopy. For each culture, at each time point, the average number of spirochetes per field of view (×400 magnification) was determined from counts of 10 fields. The average number of cells at each time point is presented.

Plasmid analysis by PFGE.

Linear plasmid composition was assessed using contour-clamped homogeneous electric field–pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (CHEF-PFGE; Bio-Rad) as previously described (4). In brief, DNA from cells lysed in agarose was fractionated in 1% GTG-grade agarose gels (0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA, pH 8.0; 14°C). Electrophoresis parameters (calibration factor, 1.00; gradient, 6.0 V/cm; run time, 15 h 16 min; included angle, 120°; initial switch time, 0.22 s; final switch time, 17.33 s; ramping factor, a, linear) were generated using the CHEF mapper auto-algorithm function and maximized for separation of DNA molecules of between 5 and 200 kb. DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses.

B. hermsii cell lysates were solubilized, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 15% precast Criterion gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride by electroblotting (23), and screened with antisera as previously described (16). Mouse anti-FhbA (15) and mouse anti-FlaB antisera were used at dilutions of 1:1,000 and 1:400,000, respectively. Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:40,000; Pierce) served as the secondary antibody, with detection by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West; Pierce).

Infection analyses and visualization of GFP production in vivo.

Infectivity was assessed by subcutaneous needle inoculation of C3H/HeJ mice (3 per group) with 5 × 104 spirochetes in BSK-H medium. Blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes from tail nicks performed 3, 4, and 7 days postinoculation, and the presence of spirochetes was assessed by dark-field microscopy. For reisolation of spirochetes, undiluted blood (6 μl) was inoculated into BSK-H medium (supplemented with rifampin, fosfomycin, and amphotericin). GFP production was assessed by fluorescence microscopy of spirochetes present in log-phase cultures and heparinized blood samples (diluted 1:20 in PBS). All microscopy was performed using an Olympus BX51 microscope, and images were captured using an Olympus DP71 camera (DP Controller 3.1.1.267 software; Olympus).

Serological analyses.

Blood was collected at 6 weeks postinoculation and serum harvested using standard methods. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with a suspension of wild-type B. hermsii YOR (B. hermsii YOR-wt) cells and screened with a dilution series of sera collected from each mouse. All methods were as previously described (9).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation and characterization of a GFP-expressing B. hermsii strain.

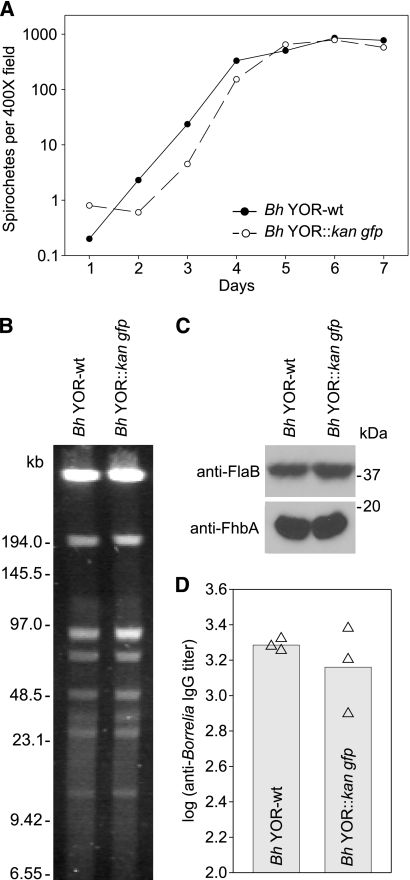

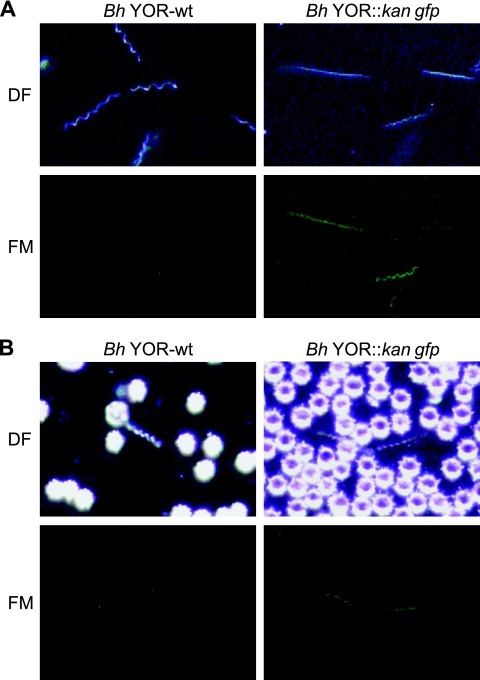

To generate a B. hermsii clonal population that harbors a selectable marker (kan) and constitutively expresses a fluorescent marker (gfp), the pFAEV3 vector was constructed (Fig. 1A) and electroporated into B. hermsii YOR cells. The kan-gfp cassette was successfully inserted into a noncoding sequence of 209 bp located on lp200 between the fhbA gene and a hypothetical ORF (Fig. 1B). lp200 was chosen to harbor the integration site due, in part, to the availability of sequence for this plasmid and its wide distribution and stability among B. hermsii isolates (15, 16, 22). Clonal transformant populations were obtained by limiting dilution. It is worthy of note that efforts to generate clonal populations using subsurfacing plating methods, originally developed for B. burgdorferi (30), were not successful. Growth curve and Western blot analyses revealed that insertion of the cassette does not influence growth kinetics (Fig. 2A) or interfere with expression of the adjacent fhbA gene (Fig. 2C). GFP production by the B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp strain was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3A). Note that when these analyses were initiated, attempts were made to insert the kan-gfp cassette into the B. hermsii DAH strain, which is the type strain for this species. While those efforts were not successful, we have subsequently achieved allelic exchange in the DAH isolate using the methods detailed here (R. T. Marconi, unpublished data). Hence, the approach described within can be applied in the genetic manipulation of other strains of B. hermsii.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp strain. (A) The growth rates of B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp and the parental wild-type strain (Bh YOR-wt) were determined as indicated in the text. (B) The plasmid content of each strain was assessed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and ethidium bromide staining. DNA size standards (in kb) are indicated to the left of the panel. (C) Immunoblot analyses of whole-cell lysates of each strain were screened with anti-FhbA or anti-FlaB antiserum (as indicated). (D) The anti-B. hermsii YOR IgG titers elicited by each strain were determined by ELISA. Whole-cell lysates of the wild-type strain served as the immobilized antigen.

Fig. 3.

Demonstration of GFP production. Dark-field microscopy (DF) was used to detect spirochetes, and fluorescence microscopy (FM) was used to detect GFP production during in vitro cultivation (A) and in diluted blood samples from infected mice (B). All methods were as detailed in the text.

As discussed above, electroporation of B. burgdorferi often results in the loss of some plasmids (20, 25, 29). Since Borrelia plasmids bear genes required for survival in mammalian and arthropod hosts, plasmid loss can influence the interpretation of mutagenesis studies. In B. burgdorferi, plasmid content is typically assessed by PCR using plasmid-specific primer sets (19, 24, 25). However, while the sequence of the B. hermsii DAH chromosome is available (htt://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore?term, Borrelia hermsii DAH genome), sequences for the plasmids are not. Hence, plasmid-specific PCR could not be applied for this purpose here. To determine if genetic manipulation of B. hermsii YOR resulted in plasmid loss, plasmid composition was assessed using PFGE. The plasmid profiles of the parental strain and the GFP-producing clone were indistinguishable (Fig. 2B). However, it is possible that some B. hermsii plasmids were not discerned by this approach due to size similarities and comigration patterns. In addition, circular plasmids migrate as diffuse bands in PFGE systems and are not readily visualized by staining. With these limitations in mind, we did not observe differences in plasmid profiles. The analyses detailed below provide further verification that plasmids required for survival in mammalian hosts were not lost, since the B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp strain retained infectivity.

B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp is infectious and expresses GFP in vivo.

To determine if the B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp strain is infectious in mice and produces GFP during infection, mice were needle inoculated and blood was collected at 3, 4, and 7 days postinoculation. Both the B. hermsii wild type- and the B. hermsii YOR::kan gfp-inoculated mice developed significant and equivalent anti-B. hermsii IgG titers, indicating seroconversion (Fig. 2D). To confirm infection status, blood samples from infected mice were placed in BSK-H media. All blood samples yielded positive cultures. To determine if GFP expression was stable during infection and upon reisolation from mammals, fluorescence microscopy was performed on recultivated spirochetes and on diluted blood samples obtained during infection (Fig. 3B). All spirochetes observed by microscopy produced GFP; however, some variation in GFP expression among cells was evident (data not shown). These results demonstrate that (i) GFP production by the YOR transformant strain is stable in vivo and in vitro, (ii) insertion of GFP into lp200 does not interfere with in vivo viability, and (iii) plasmids required for infectivity (including those potentially not visualized by PFGE) were not lost during genetic manipulation.

Concluding remarks.

Prior to this study, there had been only a single report of the successful genetic manipulation of a TBRF spirochete (2). In that study, the vtp gene of B. hermsii DAH (clone 2E7) was replaced with an antibiotic resistance cassette to generate a B. hermsii DAH vtp mutant. It is noteworthy that, since the original study of Battisti et al. (2), there have been no additional publications demonstrating genetic manipulation in TBRF spirochetes, and new tools for this purpose have not been developed. The goal of this study was to expand the molecular tools available for studying the pathogenesis of TBRF spirochetes. Specifically, we sought to construct a well-characterized, GFP-producing clone of B. hermsii YOR that could be employed by us and others in the field as an infectious, fluorescence-tagged parental strain for future mutagenesis analyses. In summary, a kan-gfp cassette was successfully incorporated into lp200 of B. hermsii YOR. This modified native plasmid proved to be highly stable, with no observed loss of antibiotic resistance or GFP production after several passages in media (even in the absence of selection) and after passage through mice. By all criteria, the GFP-producing strain appeared identical to the wild type, and no evidence for plasmid loss resulting from genetic manipulation was observed. The GFP strain readily infected mice, and analyses of blood smears revealed a strong spirochete-associated GFP signal, demonstrating expression in vivo. The B. hermsii strain generated in this report can serve as a useful tool for future investigations of B. hermsii virulence mechanisms.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barbour A. G., Dai Q., Restrepo B. I., Stoenner H. G., Frank S. A. 2006. Pathogen escape from host immunity by a genome program for antigenic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:18290–18295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Battisti J. M., Raffel S. J., Schwan T. G. 2008. A system for site-specific genetic manipulation of the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii. Methods Mol. Biol. 431:69–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyer K. M., et al. 1977. Tick-borne relapsing fever: an interstate outbreak originating at Grand Canyon National Park. Am. J. Epidemiol. 105:469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlyon J. A., LaVoie C., Sung S. Y., Marconi R. T. 1998. Analysis of the organization of multicopy linear- and circular-plasmid-carried open reading frames in Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. Infect. Immun. 66:1149–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cutler S., Talbert A. 2003. Tick-borne relapsing fever in Tanzania—a forgotten problem? ASM News 69:542–543 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dai Q., et al. 2006. Antigenic variation by Borrelia hermsii occurs through recombination between extragenic repetitive elements on linear plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1329–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dupont H. T., La Scola B., Williams R., Raoult D. 1997. A focus of tick-borne relapsing fever in southern Zaire. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dworkin M., Shoemaker P., Fritz C., Dowell M., Anderson D. E., Jr 2002. The epidemiology of tick-borne relapsing fever in the United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66:753–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Earnhart C. G., et al. 2010. Identification of residues within ligand-binding domain 1 (LBD1) of the Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein required for function in the mammalian environment. Mol. Microbiol. 76:393–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eggers C. H., Caimano M. J., Radolf J. D. 2004. Analysis of promoter elements involved in the transcriptional initiation of RpoS-dependent Borrelia burgdorferi genes. J. Bacteriol. 186:7390–7402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Felsenfeld O. 1971. Borrelia. Strains, vectors, human and animal borreliosis. Warren H. Green, Inc., St. Louis, MO [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fritz C. L., et al. 2004. Isolation and characterization of Borrelia hermsii associated with two foci of tick-borne relapsing fever in California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1123–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goubau P. F. 1984. Relapsing fevers. A review. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 64:335–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hovis K. M., Freedman J. C., Zhang H., Forbes J. L., Marconi R. T. 2008. Identification of an antiparallel coiled-coil/loop domain required for ligand binding by the Borrelia hermsii FhbA protein: additional evidence for the role of FhbA in the host-pathogen interaction. Infect. Immun. 76:2113–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hovis K. M., McDowell J. V., Griffin L., Marconi R. T. 2004. Identification and characterization of a linear-plasmid-encoded factor H-binding protein (FhbA) of the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii. J. Bacteriol. 186:2612–2618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hovis K. M., Schriefer M. E., Bahlani S., Marconi R. T. 2006. Immunological and molecular analyses of the Borrelia hermsii factor H and factor H-like protein 1 binding protein, FhbA: demonstration of its utility as a diagnostic marker and epidemiological tool for tick-borne relapsing fever. Infect. Immun. 74:4519–4529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ilsley M. L. 1952. Relapsing fever probably caused by Borrelia duttonii. Calif. Med. 77:195–196 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jongen V. H., van Roosmalen J., Tiems J., Van Holten J., Wetsteyn J. C. 1997. Tick-borne relapsing fever and pregnancy outcome in rural Tanzania. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 76:834–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Labandeira-Rey M., Skare J. T. 2001. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with the loss of either linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect. Immun. 69:446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lawrenz M. B., Kawabata H., Purser J. E., Norris S. J. 2002. Decreased electroporation efficiency in Borrelia burgdorferi containing linear plasmids lp25 and lp56: impact on transformation of infectious B. burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 70:4798–4804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lescot M., et al. 2008. The genome of Borrelia recurrentis, the agent of deadly louse-borne relapsing fever, is a degraded subset of tick-borne Borrelia duttonii. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lopez J. E., et al. 2008. Relapsing fever spirochetes retain infectivity after prolonged in vitro cultivation. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 8:813–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marconi R. T., Konkel M. E., Garon C. F. 1993. Variability of osp genes and gene products among species of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect. Immun. 61:2611–2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDowell J. V., Sung S. Y., Labandeira-Rey M., Skare J. T., Marconi R. T. 2001. Analysis of mechanisms associated with loss of infectivity of clonal populations of Borrelia burgdorferi B31MI. Infect. Immun. 69:3670–3677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purser J. E., Norris S. J. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13865–13870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ras N., et al. 1996. Phylogenesis of relapsing fever Borrelia spp. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:859–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rebaudet S., Parola P. 2006. Epidemiology of relapsing fever borreliosis in Europe. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 48:11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rogers E. A., et al. 2009. Rrp1, a cyclic-di-GMP-producing response regulator, is an important regulator of Borrelia burgdorferi core cellular functions. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1551–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosa P. A., Tilly K., Stewart P. E. 2005. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samuels D. S., Mach K., Garon C. F. 1994. Genetic transformation of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi with coumarin-resistant gyrB. J. Bacteriol. 176:6045–6049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwan T. G., et al. 2003. Tick-borne relapsing fever caused by Borrelia hermsii in Montana. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1151–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwan T. G., Raffel S. J., Schrumpf M. E., Porcella S. F. 2007. Diversity and distribution of Borrelia hermsii. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:436–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwan T. G., et al. 2009. Tick-borne relapsing fever and Borrelia hermsii, Los Angeles County, California, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1026–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trevejo R. T., et al. 1998. An interstate outbreak of tick-borne relapsing fever among vacationers at a rocky mountain cabin. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58:743–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vial L., et al. 2006. Incidence of tick-borne relapsing fever in west Africa: longitudinal study. Lancet 368:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]