Abstract

Expression of ID1 (inhibitor of differentiation) has been correlated with the progression of a variety of cancers, but little information is available on its role in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Here we show that ID1 is induced by nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in a panel of NSCLC cell lines and primary cells from the lung. ID1 induction was Src dependent and mediated through the α7 subunit of nAChR; transfection of K-Ras or EGFR to primary cells induced ID1. ID1 depletion prevented nicotine- and EGF-induced proliferation, migration, and invasion of NSCLC cells and angiogenic tubule formation of human microvascular endothelial cells from lungs (HMEC-Ls). ID1 could induce the expression of mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and fibronectin by downregulating ZBP-89, a zinc finger repressor protein. ID1 levels were elevated in tumors from mice that were exposed to nicotine. Further, human lung tissue microarrays (TMAs) showed elevated levels of ID1 in NSCLC samples, with maximal levels in metastatic lung cancers. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) performed on patient lung tumors showed that ID1 levels were elevated in advanced stages of NSCLC and correlated with elevated expression of vimentin and fibronectin, irrespective of smoking history.

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor in the development of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for 80% of all lung cancers (22, 23). In addition to the mutagenic effect of tobacco-specific nitrosamines like 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN), these agents and nicotine can affect cellular functions through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (51, 52, 65). While nAChRs are mainly expressed in neurons and neuromuscular junctions, they are also present on a variety of nonneuronal cells, where they induce cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis (16, 19, 20, 36, 53, 67). While there is scant evidence that nicotine contributes to the initiation of tumors, it has been demonstrated that nicotine can promote the growth and metastasis of solid tumors in vivo (10, 44), suggesting that nicotine might be promoting the progression of tumors already initiated by the tobacco-specific nitrosamines (10).

While the majority of NSCLC cases are correlated with smoking, about 25% of the patients are nonsmokers. NSCLCs in smokers and nonsmokers have different molecular signatures; NSCLC cells in smokers harbor mutations mainly in Ras and p53 genes while epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are less prevalent (60, 64). On the other hand, NSCLC cells in nonsmokers show more widespread mutations in the kinase domain of EGFR encoded by exons 18 to 24 (38) and show high expression of p27 and Akt1 (59, 69). Interestingly, the EGFR gene is amplified or overexpressed in late-stage cancers in both smokers and nonsmokers, indicating that EGFR activity contributes to the growth and progression of NSCLC (54, 58, 60). Indeed, EGFR overexpression is observed in 62% of NSCLC cases and is correlated with poor prognosis (21, 38, 54). Studies in recent years have also shown polymorphisms in nAChR genes that correlate with NSCLC in smokers (25, 37, 51). Since primary cells from the lung as well as lung cancer cells can proliferate in response to both nAChR and EGFR signaling, it is probable that there might be common mediators of these signals in smokers and nonsmokers. Here we demonstrate that the transcriptional repressor ID1 (inhibitor of DNA binding/differentiation 1) is a common mediator of nAChR and EGFR signaling in NSCLC.

ID proteins belong to the helix-loop-helix (HLH) family of transcription factors acting as dominant negative transcriptional repressors of basic HLH (bHLH) factors (27, 45). Increased expression of ID1 has been shown to be associated with decreased cell differentiation and enhanced cell proliferation (39, 40). ID1 has been shown to induce proliferation by transcriptionally inhibiting the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p16, p21, p27, and p57 (41). ID1 overexpression has been correlated with a variety of human cancers, including breast, prostate, pancreatic, ovarian, endometrial, and bladder cancers and melanomas (27, 35, 43, 55, 56). Further, ID1 expression has been associated with more aggressive, more invasive, and less differentiated cancers (3, 49). Recently ID1 has been shown to be expressed in a majority of NSCLC tissue microarray (TMA) samples by immunohistochemistry (48). While it has been suggested that ID1 can promote the invasion of NSCLC cells (4), not much information is known about its role in the growth and progression of NSCLCs. In the present study, we report that ID1 is induced in a wide variety of NSCLC cell lines as well as primary epithelial and endothelial cells from the lung in response to nAChR as well as EGFR signaling. Depletion of ID1 using ID1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) prevented nicotine- and EGF-induced proliferation and invasion of cells. ID1 could also transcriptionally induce fibronectin and vimentin genes, which are mesenchymal genes that facilitate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT); this was facilitated by the ID1-mediated downregulation of a repressor, ZBP-89. Further, the levels of ID1 were elevated in tumors from mice exposed to nicotine as well as in human metastatic NSCLC, irrespective of smoking status. These results raise the possibility that ID1 is a common mediator of NSCLC progression and metastasis in both smokers and nonsmokers and that therapeutic targeting of ID1 might be a viable strategy for combating NSCLC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents.

The human NSCLC cell line A549 (bronchioloalveolar carcinoma [BAC]) was maintained in Ham's F-12K medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; CellGro). H1650, H820, H292, H322, H358, H1299, H2279, PC9, and HCC827 were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech Cellgro) containing 10% FBS. Human microvascular endothelial cells from lungs (HMEC-Ls) were obtained from Clonetics and cultured in EBM-2 supplemented with 5% serum and growth factors (EGM-2 bullet kit; Lonza). Normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBEs; Lonza) and AALE cells (tracheobronchial epithelial cells [17]) were maintained in bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM) containing growth supplement, and small airway epithelial cells (SAECs) were cultured in SAEC growth medium (SAGM) supplemented with growth factors per the supplier's instructions.

For nicotine stimulation, NHBEs, SAECs, and HMEC-Ls were rendered quiescent by growth in basal medium without growth factors and serum for 24 h and subsequently stimulated with 1 μM nicotine for 2, 6, or 18 h.

The studies using nicotine or signal transduction inhibitors were done on cells that were rendered quiescent by serum starvation for 48 h. Cells were preincubated with the indicated inhibitors for 30 min, following which 1 μM nicotine (Sigma Chemical Company) was added. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 6 h (for the experiment shown in Fig. 3G). LY294002 (used at 1 μM), α-bungarotoxin (α-BT; used at 1 μM), and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE; 1 μM) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company. PP2 (used at 1 μM) was purchased from Alexis Biotechnologies.

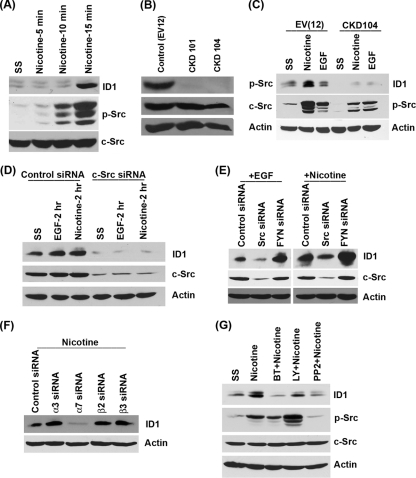

Fig. 3.

Nicotine-induced ID1 expression is mediated by Src. (A) A549 cells stimulated with nicotine show elevated levels of phospho-Src. (B) Phospho-Src levels are significantly lower in A549 cells that are stably transfected with a dominant negative Src construct (CKD101 and -104) than in the control cells. (C) The CKD104 cell line does not induce ID1 upon nicotine stimulation. (D) Transient transfection of Src siRNA reduced endogenous ID1 levels and prevented ID1 induction by EGF and nicotine. (E) Src siRNA prevented the induction of ID1 by EGF and nicotine; Fyn siRNA had no effect, indicating the specific involvement of Src. (F) Depletion of α7 subunit of nAChR abrogated nicotine-induced expression of ID1. (G) Nicotine-induced ID1 expression is ablated by 1 μM α7 nAChR inhibitor α-bungarotoxin and 1 μM Src inhibitor PP2. The PI3K inhibitor LY compound had only a marginal effect on ID1 inhibition.

Generation of stable cell lines.

A549 cells that stably express dominant negative Src (CKD104, kinase dead) were generated by transfecting A549 cells with a plasmid construct that expresses mutant kinase-dead Src and selecting for puromycin resistance. A549 cells transfected with empty vector (called A549-EV [12]) were used as the control.

Lysate preparation and Western blots.

Lysates from cells treated with different agents were prepared by NP-40 lysis as described earlier, and 100 μg protein was run on a polyacrylamide-SDS gel. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotted with antibodies raised against various proteins. Monoclonal ID1 antibody purchased from Biocheck (BCH-1; catalog no. 195-14 cDNA), monoclonal c-Src antibody obtained from Upstate Biotech, and polyclonal phospho-Src antibody from Cell Signaling were used in Western blot assays. Monoclonal antibody to actin was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.

Transfections and luciferase assays.

Fibronectin (pFN, 1.2 kb) and vimentin (VimPro, 1.5 kb) promoter-luciferase constructs were kindly provided by Jesse Roman (Emory University) and C. Gilles (Liege University, Belgium) (15, 72). ID1 promoter-luciferase construct (ID1-Luc, 2.2 kb) was a kind gift from Pierre-Yves Desprez (California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco, CA) (14, 57). Vimentin promoter-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) constructs were kindly provided by Zendra E. Zehner (Virginia Commonwealth University) (71). A549 cells were transiently transfected by the calcium phosphate method, and H1650 cells were transfected using Fugene HD reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase assays were done 48 h posttransfection, using the dual luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and luciferase activity was measured with a luminometer (Turner luminometer). For each construct, relative luciferase activity was defined as the mean value of the firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase ratios obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Construction of ID1 deletion mutants.

Deletion mutants of ID1 promoter (ID1-1288 + 92, 1019 + 92, 902 + 92, and 555 + 92) were made in order to determine the minimal promoter region responsible for induction by nicotine and EGF. ID1 promoter fragments were PCR amplified using the full-length promoter as the template. Forward primers for PCR amplification were designed with a KpnI restriction site at the 5′ end, and reverse primers were designed with a XhoI recognition site. To generate the first deletion mutant, a promoter fragment containing 1,288 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) and 92 bp downstream of TSS was amplified using the primer pair ID1F-Kpn1288 and ID1R-Xho. Shorter promoter fragments that contain 1,019, 902, or 555 bp upstream of the TSS and 92 bp downstream of the TSS were generated using the following forward primers: ID1F-Kpn1288, ATGCTGGTACCCTCAGAGAGGGCATGCGACCCGCCTGA; ID1F-Kpn1019, ATGCTGGTACCGGAGCACGGGAACTAGCTAGACCAG; ID1F-Kpn902, ATGCTGGTACCCGGTCTGAGCCGCTGGTTCAGACG; ID1F-Kpn555, ATGCTGGTACCCAGGAACACGAACAGCAACATTATTTAG. The same reverse primer (ID1R-Xho, GTCAGCTCGAGGGCGACTGGCTGAAACAGAATG) was used for all the PCRs. The PCR fragments were digested with KpnI and XhoI, gel purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and cloned into pGL3 luciferase vector digested with KpnI and XhoI.

Proliferation assays.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling kits were obtained from Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN. A549 and H1650 cells were plated in poly-d-lysine-coated glass chamber slides at a density of 5,000 cells per well and transfected with either ID1 siRNA or control siRNA (100 picomoles) using Oligofectamine reagent. Following 24 h of transfection, cells were serum starved for 24 h and stimulated with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF for 18 h. S-phase cells stained for BrdU were visualized by microscopy and quantitated by counting 5 fields of 100 cells in triplicate. Data are representative of two independent experiments and presented as the percentage of BrdU-positive cells out of the 100 cells counted.

Invasion assays.

The invasive ability of A549 and H1650 cells was assayed according to the standard protocols (34). Briefly, the upper surfaces of the filters were precoated with collagen (100 μg/filter). Matrigel was applied to the upper surface of the filters (50 μg/filter) and dried in a hood. These filters were placed in Boyden chambers. Cells were grown to 70% confluence in respective media and were rendered quiescent by serum starvation and then treated with 1 μM nicotine (Sigma) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were trypsinized and 20,000 cells were plated in the upper chamber of the filter in medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and nicotine. Medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum was placed in the lower well as an attractant, and the chambers were incubated at 37°C. After 18 h, nonmigrating cells on the upper surface of the filters were removed by wiping with cotton swabs. The filters were processed first by fixing in methanol followed by staining with hematoxylin. The cells migrating on the other side of the filters were quantitated by counting three different fields under 40× magnification.

Wound healing assay.

A549 and H1650 cells were grown in a 6-well plate (Falcon; Becton Dickinson) transfected with siRNAs. These cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then washed with 1× Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; MediaTech). The cells were scratched with a sterilized 200-μl pipette tip in three separate places in each well, and medium containing 1 μM nicotine, EGF (100 ng/ml), or starving medium was added to the wells. After 24 h, the wounds were observed and images were taken at 20× magnification.

siRNA transfections and real-time PCR.

ID1 siRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SC-29356 and SC-44267). A nontargeting siRNA was used as the control. A549 cells, H1650 cells, or HMEC-Ls were grown in 60-mm dishes and transfected with either control siRNA (100 pmol) or ID1 siRNA (100 pmol) using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. The cells were collected 24 h after transfection, and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Levels of ID1 mRNA were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) which was performed using the Bio-Rad iCycler. The primers used for amplifying ID1 mRNA were ID1-F, 5′-GAG CTG AAC TCG GAA TCC GAA G-3′, and ID1-R, 5′ GAT CGT CCG CAG GAA CGC ATG C 3′. Data were normalized using 18S rRNA as an internal control, and the fold change in the expression levels was determined using the nontargeting siRNA as the control.

Western blotting was also carried out with anti-ID1 and anti-β-actin to monitor the expression of ID1 after siRNA transfection. siRNAs to c-Src (sc-29228), c-Myc (sc-29226), and ZBP-89 (sc-38639) and nontargeting control siRNAs (sc-37007 and sc-44230) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and siRNAs to nAChR α7 subunit (16708) and c-Myc (AM4250) were purchased from Ambion.

Real-time PCR from human lung tissue samples and statistical analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from 129 archived lung tumor samples using Trizol reagent, and cDNA was prepared using standard protocols. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in an ABI 7500 Fast Real Time system (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan probes for ID1, fibronectin, vimentin, and CHRNA7 (nAChR α7). 18S rRNA was used as an internal control. Threshold cycles of primer probes were normalized to 18S rRNA and translated to relative values.

Statistical methods and analysis.

A log transformation was performed to make mRNA expression values of four genes (ID1, VIM, FN1, and CHRNA7) approximately normal. Pearson rank correlation (r) was used to assess correlation among these four genes. An exact normal scores test was used to assess the association between mRNA expression values of these four genes and pathological stage. The reduced monotonic regression model (50) was used to assess the association between mRNA expression values of these four genes and smoking pack-years. An optimal cut point for disease-free survival (DFS), defined as the time for surgical resection to disease recurrence or death, was tested for using the maximal chi-square test (54). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Matrigel assays.

Matrigel (Becton Dickinson) was used to promote the differentiation of HMEC-Ls into capillary tube-like structures. A total of 100 μl of thawed Matrigel was added to 96-well tissue culture plates, followed by incubation for 60 min at 37°C to allow polymerization. siRNA-transfected HMEC-Ls after serum starvation and stimulation with nicotine or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were seeded (12,000 cells/100 μl Matrigel) on the gels and incubated overnight at 37°C. Capillary tube formation was assessed using a Leica DMIL phase-contrast microscope (Wetzlar).

Immunohistochemistry.

Human lung cancer tissue microarray slides (Imgenex; IMH number 358) were immunostained for ID1. The slide had a total of 60 cores covering normal lung tissues, different carcinomas of lung, and metastatic lung carcinomas. The data presented are from 9 normal lung tissues adjacent to the tumors, 39 primary tumors of the lung, and 10 metastatic lung carcinomas. Staining was done according to the protocol described previously (10). In brief, the slide was deparaffinized by baking at 62°C for 1 h and passed through xylene, rehydrated to water, and subjected to microwave “antigen retrieval” for 20 min on 70% power, with a 1-min cooling period after every 5 min in 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Sections were cooled for 20 min and rinsed 3 times in distilled water (dH2O) and twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the rest of the staining was done according to the manufacturer's protocol (Universal Elite ABC kit; Vector Labs). Primary antibody was monoclonal ID1 antibody (1:25 dilution; Biochek). For color development, the slides were treated with a peroxidase substrate kit from Vector Labs (catalog no. SK-4100) and developed using diaminobenzidine (DAB) as chromogen. After a final rinse in dH2O, sections were lightly counterstained in hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with Clarion mounting medium (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Also tissue sections obtained from animal experiments were stained in a similar manner for ID1. Immunostained slides were scanned on an Aperio automatic scanning system from Applied Imaging and scored by a pathologist (D.C.). The semiquantitative score was reached by taking into consideration both cellularity and intensity of expression (total score = cellularity × intensity; a score of 3 represents >66% cellularity, 2 represents 34% to 65% cellularity, and 1 represents <33% cellularity; intensity was scored as follows: 3, strong; 2, moderate; 1, weak). The P value was calculated using Student's t test for statistical significance. Total and nuclear expression levels of ID1 were analyzed and plotted as fold change.

RESULTS

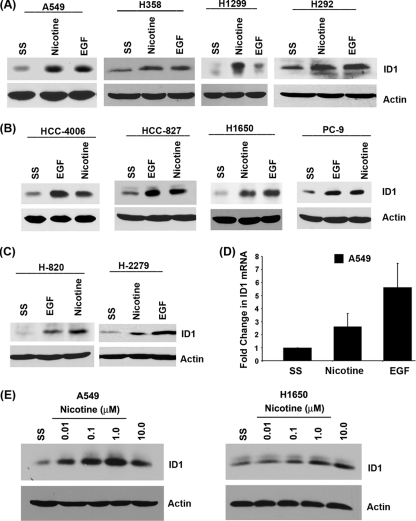

Nicotine and EGF induce expression of ID1 in NSCLC cell lines.

EGFR mutations are prevalent in NSCLC cells, and previous studies have shown that nicotine can induce cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cultured cells (6–9); further, nicotine had promoted the metastasis of NSCLC in mice (10). Given this background, we examined whether ID1 contributes to the growth and progression of NSCLC in response to nAChR and EGFR signaling. We first examined whether nicotine and EGF could induce ID1 in a panel of NSCLC cell lines harboring various mutations. The cell lines used were A549 (adenocarcinoma/bronchioloalveolar [BAC], wild-type EGFR and mutant K-Ras), H358 (BAC, wild-type EGFR and mutant K-Ras), H1650 (adenocarcinoma, mutant EGFR and wild-type K-Ras), H1299 (large cell carcinoma, wild-type EGFR and K-Ras), H820 (adenocarcinoma, mutant EGFR and wild-type K-Ras), HCC4006 (adenocarcinoma, mutant EGFR and wild-type K-Ras), PC9 (adenocarcinoma, mutant EGFR and wild-type K-Ras), HCC827 (adenocarcinoma, mutant EGFR and wild-type K-Ras), H2279 (adenocarcinoma, mutant EGFR and wild-type K-Ras), and H292 (squamous cell carcinoma [SCC], wild-type EGFR and K-Ras). Cells were rendered quiescent by serum starvation and stimulated with 1 μM nicotine (equivalent to the amount present in the bloodstream of heavy smokers [19]) or 100 ng/ml EGF; induction of ID1 was assessed by Western blotting. Stimulation with nicotine and EGF induced ID1 in all the cell lines tested, irrespective of the mutational status of K-Ras or EGFR or the histology (Fig. 1A to C). Real-time PCR on RNA from quiescent as well as nicotine- or EGF-stimulated A549 cells showed that the induction of ID1 occurred at the transcriptional level (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that signaling through nAChR and EGFR can induce the expression of ID1 in established NSCLC cell lines. Attempts were made to determine the optimum concentration of nicotine required for ID1 induction. A549 cells were serum starved and stimulated with different concentrations of nicotine (0.01 μM, 0.1 μM, 1.0 μM, and 10 μM). Nicotine induced ID1 expression even at the lowest concentration tested, and maximum induction was observed at a concentration of 1.0 μM (Fig. 1E). Similar results were obtained for H1650 cells; hence, 1.0 μM nicotine was used in all the experiments.

Fig. 1.

Nicotine and EGF induce expression of ID1 in NSCLC cell lines. (A to C) Stimulation of quiescent cells with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF induces ID1 as seen by Western blotting. (A) ID1 induction in cell lines that harbor wild-type EGFR, such as A549, H358, H1299, and H292. (B and C) Similar experiments showing ID1 induction in H1650, PC9, HCC827, HCC4006, H820, and H2279 cells that have mutant EGFR. (D) Nicotine and EGF induce transcription of ID1 mRNA in A549 cells, as seen by real-time PCR. (E) Induction of ID1 expression at different concentrations of nicotine (0.01, 0.1, 1.0, and 10 μM) in A549 and H1650 cells. SS, serum starvation.

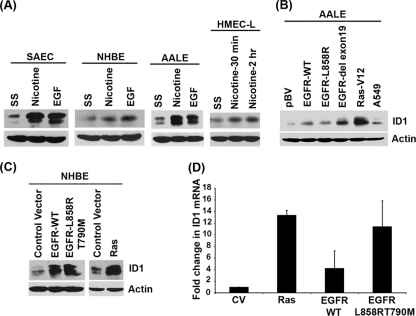

ID1 is induced by nicotine and EGF in primary lung cells.

We next examined whether nicotine and EGF could induce ID1 in a panel of primary lung cells such as small airway epithelial cells (SAECs), normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBEs), immortalized human tracheobronchial epithelial (hTBE) cells, and human microvascular endothelial cells from the lung (HMEC-Ls). Western blotting of quiescent cells stimulated with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF showed a significant induction of ID1 protein (Fig. 2A), suggesting that these agents can elicit ID1 induction in both primary and transformed cells. Since EGFR is mutated or overexpressed in most NSCLCs, we examined the levels of ID1 protein in a panel of immortalized human tracheobronchial epithelial (hTBE) cell lines (17), AALE cells, which stably overexpress EGFR-WT, EGFR-L858R, EGFR del exon 19, or control vector. As shown in Fig. 2B, it was found that ID1 levels were elevated in all of them compared to the control parental cells. Interestingly, stable overexpression of a mutant K-Ras also elevated ID1 levels, suggesting that K-Ras mutations might also elevate the levels of ID1. To further confirm the induction of ID1 by EGFR and Ras, we transiently transfected Ras-V12, EGFR-WT, or EGFR-L858R and -T790M expression vectors into NHBEs and ID1 expression was assessed by Western blotting. Transient transfection of these genes significantly enhanced the level of endogenous ID1 in NHBE cells. This raises the possibility that mutation of K-Ras as a result of exposure to tobacco carcinogens or activation of EGFR can elevate ID1 levels in primary lung epithelial cells (Fig. 2C). Here also the induction of ID1 was at the transcriptional level as revealed by RT-PCR experiments (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Induction of ID1 in primary human lung epithelial cells by nicotine and EGF. (A) Stimulation of quiescent SAEC, NHBE, AALE, and HMEC-L cells with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF induces ID1, as seen by Western blotting. (B) ID1 levels are elevated in AALE cells stably transfected with wild-type or mutant EGFR or K-Ras. (C) Transient transfection of NHBE cells with wild-type or mutant EGFR significantly enhanced the levels of ID1. (D) Transcriptional induction of ID1 in NHBEs transfected with Ras and EGFR as seen by real-time PCR.

Src is necessary for nicotine- and EGF-induced expression of ID1.

Attempts were made to elucidate the signaling pathways involved in the induction of ID1 by nAChR and EGFR. Since Src is activated by both nAChR and EGFR signaling, and since Src has been reported to induce ID1 (14), experiments were conducted to assess whether Src contributes to the induction of ID1. Western blot analysis of quiescent A549 cells stimulated with 1 μM nicotine showed Src activation within 10 min; ID1 protein could be detected within 15 min of nicotine stimulation (Fig. 3A). To elucidate the contribution of Src in the induction of ID1, we established A549 cell lines that stably express a dominant negative, kinase domain mutant Src (CKD101 and CKD104). Asynchronously growing A549 cells transfected with an empty control vector (EV12) had a significant amount of phosphorylated Src, while the CKD cells showed minimal amounts of phospho-Src (Fig. 3B). The total c-Src levels in the two cell lines were comparable. Stimulation of the control EV12 cells with nicotine or EGF led to induction of ID1 protein; in contrast, CKD104 cells stably expressing the dominant negative Src gene did not show ID1 induction in response to nicotine or EGF (Fig. 3C). This suggests that Src activation is necessary for nicotine and EGF to induce ID1. These results were further confirmed by depleting Src by transient transfection of c-Src siRNA in A549 cells. It was found that endogenous levels of ID1 were significantly reduced in Src siRNA-transfected cells compared to those in cells transfected with a control siRNA; further, there was no induction of ID1 by nicotine or EGF in the Src-depleted cells (Fig. 3D). Since it had been reported that Src family members like Fyn are induced by nicotine in certain cells (62, 63), we examined whether Fyn contributes to the induction of ID1 by nicotine. Interestingly, while depletion of Src by siRNA prevented the induction of ID1 by nicotine as well as EGF, depletion of Fyn did not affect the induction of ID1 (Fig. 3F). This confirms that Src itself is mediating the induction of ID1 in response to nicotine and EGF stimulation.

Nicotine-induced expression of ID1 is mediated by α7 subunit of nAChR.

Our earlier studies demonstrated that the α7 subunit of nAChR mediates nicotine-induced proliferation of NSCLC cells (8), while the α3/β2 subunits mediated resistance to apoptosis (7). To identify the nAChR subunit involved in the induction of ID1 by nicotine, A549 cells were transiently transfected with a control siRNA or siRNA to α3, α7, β2, and β3 subunits of nAChR; nicotine stimulation enhanced the levels of ID1 in the transfected cells, except those transfected with α7 siRNA, indicating the role of α7 in regulating nicotine-induced expression of ID1 (Fig. 3F). To confirm the role of α7 nAChR, quiescent A549 cells were induced with nicotine in the presence of 1 μM α7 nAChR antagonist, α-bungarotoxin (α-BT); it was found that α-BT could significantly impair the ID1 induction by nicotine (Fig. 3G).

It has also been reported that nicotine can induce the Akt pathway, and Akt has been shown to elevate the levels of ID1 (29); the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) Akt pathway also intersects with Src kinase activity. To examine whether the PI3K/Akt pathway contributes to nicotine-mediated induction of ID1, A549 cells were rendered quiescent and stimulated with 1 μM nicotine in the presence of 1 μM Src inhibitor PP2 or PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Fig. 3G). Western blot analysis showed that inhibiting the PI3K pathway reduced the induction of ID1 protein by nicotine, while inhibition of Src had a more pronounced effect. These experiments show that Src and PI3/Akt kinases play a major role in the induction of ID1 by nicotine.

Nicotine and EGF induce ID1 promoter activity.

Experiments were conducted to investigate whether the observed induction of ID1 protein by nicotine and EGF was a result of an induction of the ID1 promoter. A549 and H1650 cells were transiently transfected with an ID1 promoter-luciferase construct (2,212 bp of ID1 promoter cloned in pGL3 vector). The cells were rendered quiescent by serum starvation for 24 h and subsequently induced with either 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. Luciferase reporter assays showed that both nicotine and EGF could induce the ID1 promoter in both the cell lines (Fig. 4A). These results confirm that nicotine and EGF can transcriptionally induce ID1, probably leading to the increased protein levels.

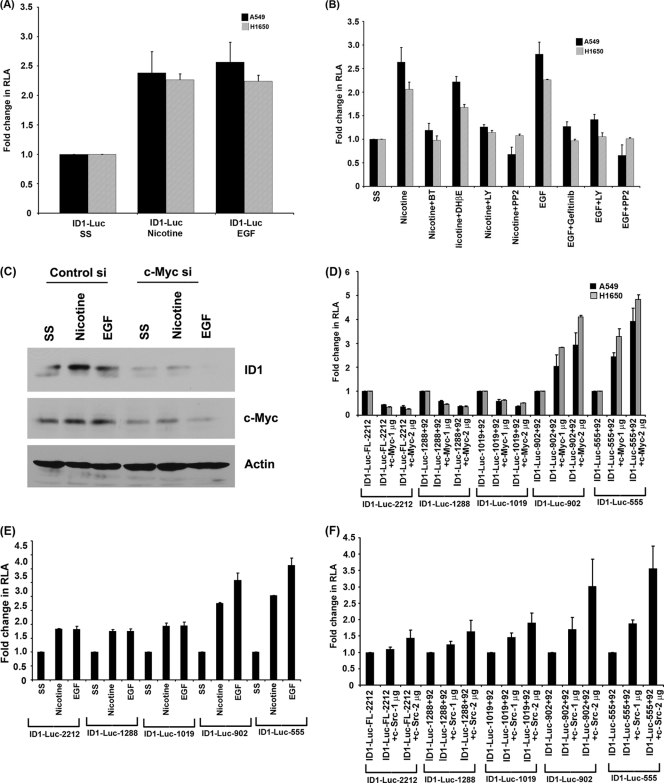

Fig. 4.

Nicotine and EGF induce ID1 promoter activity. (A) A549 and H1650 cells transfected with ID1 promoter constructs showed enhanced promoter activity in response to nicotine and EGF stimulation. (B) Promoter activity was significantly reduced when the cells were treated with α-bungarotoxin, PP2, and LY compound, indicating the involvement of α7 subunit of nAChR, Src, and PI3K pathway in nicotine-induced ID1 expression. Gefitinib, PP2, and LY compound abrogated EGF-mediated ID1 promoter induction. (C) Depletion of c-Myc using siRNA abrogates ID1 expression as seen in Western blots. (D) Induction of ID1 promoters (ID1-902 and ID1-555) after transfection with c-Myc expression vector. (E and F) Nicotine-, EGF-, and Src-responsive region of ID1 promoter overlaps with the c-Myc-responsive region. Shorter ID1 promoter constructs (ID1-902 + 92 and ID1-555 + 92) showed higher induction in response to nicotine and EGF treatment. Cotransfection with c-Src constructs also showed higher induction of the shorter promoter constructs, indicating the presence of nicotine-, EGF-, c-Myc-, and c-Src-responsive elements in the 555-bp region upstream of the TSS. RLA, relative luciferase activity.

Experiments were designed to assess whether signaling molecules, including Src and PI3K, affected the transcriptional induction of ID1 by nicotine and EGF. A549 and H1650 cells were transiently transfected with ID1-luciferase constructs and subjected to serum starvation. Cells were then stimulated with nicotine or EGF for 24 h, in the presence or absence of the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. It was observed that these agents prevented the induction of ID1 luciferase by nicotine as well as EGF in both the cell lines. In addition, α-BT could inhibit the induction of ID1 luciferase by nicotine, showing a role for the α7 nAChR subunit in the process; DHβE did not affect the nicotine-mediated induction, indicating that the induction is indeed mediated through the α7 subunit. EGF-induced induction of ID1 was inhibited by the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib in both the cell lines (Fig. 4B). These results show that the inductions of the ID1 promoter by nicotine and EGF are receptor-dependent events that are mediated by Src and the PI3K/Akt pathway.

Experiments were conducted to determine the transcriptional mechanisms involved in the induction of ID1 promoter by nicotine and EGF. Since c-Myc is known to be induced by Src, and since it has been reported that c-Myc can induce ID1, ID2, and ID3 (26, 31, 61), we examined whether c-Myc mediates the induction of ID1 by nicotine and EGF. Toward this purpose, cells were transfected with a control siRNA or a siRNA to c-Myc; reduction of c-Myc levels led to a significant reduction in the induction of ID1 by nicotine and EGF as seen by Western blot assays (Fig. 4C) and by RT-PCR (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with a different species of c-Myc siRNA (AM4256; data not shown). This suggests that c-Myc might mediate the induction of ID1 in response to nicotine and EGF.

Deletion mutants of ID1 promoter were made in order to determine the region responsible for induction by c-Myc (ID1-1288 + 92, 1019 + 92, 902 + 92, and 555 + 92). Transient-transfection assays using the deletion mutants showed that the full-length and longer ID1 promoter constructs (ID1-2.2 kb, ID1-1288 + 92, and ID1-1019 + 92) were not induced by c-Myc while the shorter promoter fragments (ID1-902 + 92 and ID1-555 + 92) were strongly induced (Fig. 4D); this suggests that there may be a repressor element in the upstream region that counteracts c-Myc function. Experiments were performed to assess whether the c-Myc-responsive region responded to nicotine and EGF. Although all the promoter constructs were induced by nicotine and EGF, the shorter promoter constructs that were responsive to c-Myc showed a higher level of induction (Fig. 4E). Further, cotransfection experiments with a c-Src construct also showed a similar pattern of promoter induction (Fig. 4F). Taken together, we conclude that c-Myc is involved in the nicotine- and EGF-mediated induction of ID1 in a Src-dependent fashion.

Depletion of ID1 inhibits nicotine- and EGF-induced proliferation.

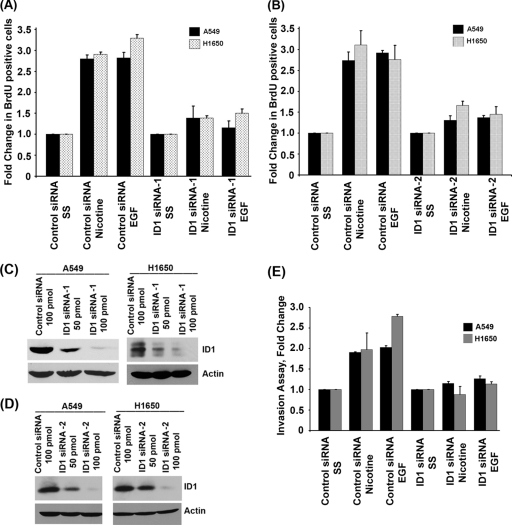

Our earlier studies had shown that nAChR stimulation led to the activation of Src, Raf-1 kinase, and cyclin–cyclin-dependent kinases (cyclin-CDKs), culminating in elevated E2F1 transcriptional activity and cell proliferation (6–9). Since Src is known to elevate ID1 levels, we examined the effect of depleting ID1 on nAChR- and EGFR-mediated cell proliferation. A549 cells carrying a wild-type EGFR gene and H1650 cells carrying mutant EGFR were transfected with 100 pmol of a nontargeting control siRNA or an siRNA to ID1 (SC-29356); cells were then rendered quiescent by serum starvation for 24 h and subsequently stimulated with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF for 18 h. It was found that stimulation of the control siRNA-transfected cells with nicotine or EGF led to a robust incorporation of BrdU (10% BrdU-positive cells in serum-starved cells versus about 30% in stimulated cells; data not shown), suggesting S-phase entry and cell proliferation; in contrast, BrdU incorporation was greatly reduced in cells transfected with an ID1 siRNA (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained when a different siRNA directed against ID1 (SC-44267) was used (Fig. 5B). Depletion of ID1 protein levels after siRNA transfection was confirmed by Western blotting for ID1. Indeed, transfection with 100 pmol of ID1 siRNA significantly reduced ID1 in both A549 and H1650 cells compared to the control siRNA (Fig. 5C and D). This experiment suggests that ID1 is necessary for the proliferative response of cells irrespective of their EGFR status.

Fig. 5.

Depletion of ID1 inhibits nicotine- and EGF-induced proliferation and abrogates invasive capacity of cells. (A) Depletion of ID1 in A549 or H1650 cells significantly reduces EGF- and nicotine-induced cell proliferation as seen in a BrdU incorporation assay. Three areas of cells were counted from two separate experiments, and results are presented graphically. (B) Similar results were obtained when a second ID1 siRNA was used. (C and D) Western blots showing depletion of ID1 in A549 and H1650 cells upon transfection of ID1 siRNA. (E) ID1 siRNA significantly inhibited the ability of A549 and H1650 cells to invade in response to nicotine or EGF exposure as seen in Boyden chamber assays.

Depletion of ID1 abrogates the invasive capacity of cells.

Studies have suggested that exposure to nicotine can enhance the metastatic potential of NSCLC (10, 47). Experiments were conducted to assess how depletion of ID1 affected the invasive property of A549 and H1650 cells. To examine this, cells were transiently transfected with 100 pmol of a nontargeting control siRNA or an ID1 siRNA. Cells were serum starved and subsequently stimulated with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. The cells were then plated on Boyden chambers and allowed to invade in response to nicotine or EGF. As shown in Fig. 5E, cells transfected with the control siRNA invaded through the collagen and Matrigel-coated filters robustly upon nicotine and EGF stimulation. In contrast, the invasion was greatly inhibited in cells transfected with ID1 siRNA, suggesting that invasion induced by these agents requires ID1.

Depletion of ID1 abrogates migratory ability of cells.

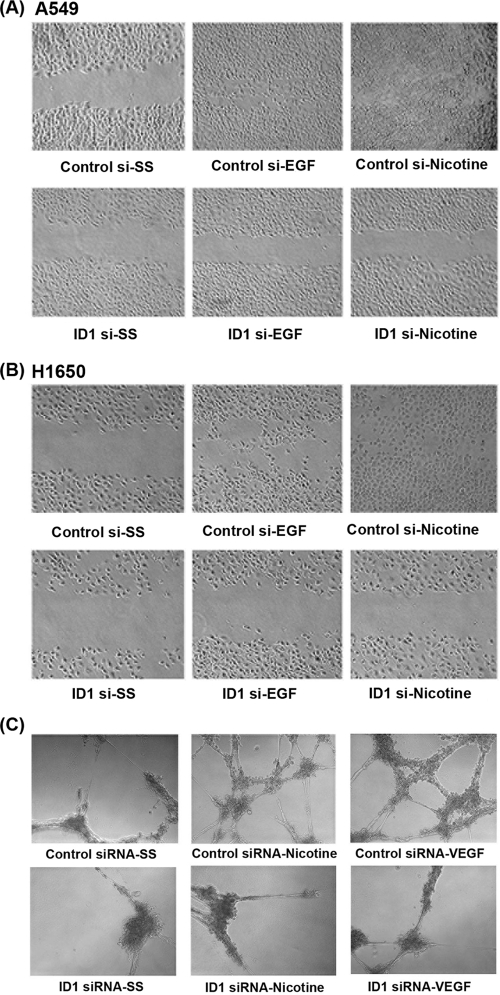

Since ID1 facilitates the invasive properties of A549 and H1650 cells, we decided to investigate whether ID1 plays a role in migration of these cells in response to nicotine or EGF stimulation, using wound healing assays. Toward this purpose, A549 and H1650 cells were transfected with ID1 siRNA or control siRNA and grown to 80 to 90% confluence on 35-mm dishes. The plates were scratched with a pipette tip, and the cells were induced with nicotine or EGF for 24 h. It was observed that ID1-depleted cells did not migrate to the scratched area while control siRNA-treated cells could migrate to the wounded area upon nicotine or EGF stimulation (Fig. 6A and B). These results raise the possibility that ID1 regulates the expression of genes involved in the invasion and migration of cells.

Fig. 6.

Depletion of ID1 abrogates migratory ability of NSCLC cells and angiogenic tubule formation in HMEC-Ls. Wound healing assays show that depletion of ID1 greatly retarded the migratory capacity of cells in response to EGF or nicotine stimulation in A549 (A) and H1650 (B) cells. Depletion of ID1 inhibits angiogenic tubule formation in HMEC-Ls in response to nicotine and VEGF. Transient transfection of a control siRNA did not affect angiogenic tubule formation in growth factor-reduced Matrigel when stimulated with nicotine or VEGF, while transfection of ID1 siRNA significantly reduced angiogenic tubule formation (C).

Depletion of ID1 inhibits angiogenic tubule formation.

Given that ID1 has been shown to promote angiogenesis by repressing the antiangiogenic protein thrombospondin-1 (66) and the observations that nicotine can induce angiogenesis significantly (6, 19), attempts were made to assess whether ID1 contributes to nicotine- and VEGF-induced angiogenic tubule formation in Matrigel. Primary human microvascular endothelial cells from the lung (HMEC-Ls) were transiently transfected with a control siRNA or ID1 siRNA and serum starved for 24 h as in the previous experiments. Cells were seeded on growth factor-reduced Matrigel and stimulated with nicotine or VEGF. Angiogenic tubule formation was induced by treatment with 1 μM nicotine or 100 ng/ml VEGF for 18 h. As shown in Fig. 6C, HMEC-Ls transfected with control siRNA showed robust sprouting of angiogenic tubules; at the same time, tubule formation was greatly reduced in cells transfected with ID1 siRNA. These findings suggest that ID1 contributes to NSCLC angiogenesis in response to exposure to nicotine.

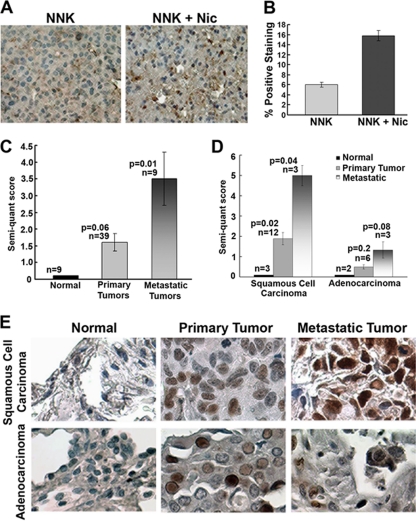

ID1 is overexpressed in lung tumors of mice exposed to nicotine.

Experiments were designed to examine the effects of nicotine on tumors induced by the tobacco carcinogen NNK; this experimental system mimics a situation where tumors are initiated by a carcinogen, followed by exposure to nicotine alone, as in nicotine replacement therapy. We had reported that A/J mice (n = 16) treated with 100 mg NNK/kg of body weight once a week for 5 weeks to initiate tumor formation developed significantly larger tumors when they were administered nicotine 1 mg/kg (n = 8) three times weekly by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection for 28 weeks (10). Lungs from NNK-treated mice or those exposed to NNK and nicotine were harvested, and levels of ID1 in tumor foci were examined by immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal ID1 antibody (BCH-1; Biocheck). As shown in Fig. 7A, tumors from mice exposed to nicotine had significantly higher ID1 expression than those from mice where tumors were induced by NNK but not exposed to nicotine (Fig. 7B). This result also suggests that ID1 is a target of nAChR signaling in vivo and might be contributing to tumor growth induced by nicotine and nAChR activation.

Fig. 7.

(A) ID1 levels are elevated in NNK-induced lung tumors in A/J mice which are exposed to nicotine, 1 mg/kg 3 times a week. (B) Quantification of immunohistochemistry data shows a 3-fold increase of ID1 in mice that received nicotine. (C) ID1 expression was 1.6-fold more in primary tumors of the lung and 3-fold more in the metastatic ones than in the normal lung tissues. (D) ID1 levels are elevated in squamous cell carcinomas compared to normal tissue as seen by immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays. Metastatic foci in lymph nodes of the same patient had even higher ID1 levels than did the primary tumor. Similar results were obtained in adenocarcinomas. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma also showed elevated ID1 expression in tumors compared to normal lung tissue. (E) Quantification of ID1 staining of human NSCLC samples using a monoclonal antibody. ID1 levels were elevated in primary tumors compared to normal lung; levels were maximum in metastatic foci.

Similar results were obtained in a second mouse model that was tested in immunocompetent mice. Line1 mouse adenocarcinoma cells were implanted into the flanks of BALB/c mice and allowed to form tumors. Mice that received nicotine (1 mg/kg) three times weekly by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection had significantly larger tumors than did those receiving vehicle (10). Levels of ID1 in two pairs of tumors from control or nicotine-treated animals were examined by Western blotting. It was found that ID1 levels were elevated in both the tumors derived from mice that received nicotine, suggesting that nAChR activation in vivo can lead to elevated levels of ID1 (data not shown); further, this finding supports the contention that ID1 contributes to nicotine-mediated growth of NSCLC in vivo, reflecting the results of the in vitro studies.

ID1 levels are elevated in primary NSCLC tumors compared to normal lung tissue.

ID1 has been reported to be overexpressed in a variety of human tumors, and we made attempts to assess its expression status in primary and metastatic NSCLC. Toward this purpose, commercially obtained human lung tumor tissue microarrays (Imgenex; IMH 358) were stained for ID1 expression. Immunohistochemical analysis using an ID1 monoclonal antibody showed that primary tumor tissues had larger amounts of ID1 than did normal tissue in the case of all the tumor types. As shown in Fig. 7C, the immunohistochemical analysis of 9 normal tissues, 39 primary tumors, and 9 metastatic lung tumors with ID1 monoclonal antibody revealed the expression of ID1 to be minimal or negative in normal tissues, to be moderate to strong in primary tumors, and to be the highest in the metastatic lung tumors. Similar results were obtained using a polyclonal antibody (data not shown). Importantly, the TMAs had matching metastatic tissue from the lymph nodes for certain SCCs and adenocarcinomas. The quantified results are presented in Fig. 7D. As shown in Fig. 7E, ID1 levels were maximal in the metastatic tumors, compared to the primary tumors or the normal tissues. These results strongly suggest that ID1 expression increases during NSCLC progression, independently of the histologic tumor subtype, and that it probably contributes to the metastasis of NSCLC in both smokers and nonsmokers.

ID1 regulates the expression of mesenchymal markers vimentin and fibronectin.

Our studies have shown that nicotine can induce invasion and migration of NSCLC cells along with EMT-like changes in an α7 receptor- and Src-dependent manner (9). Nicotine can diminish the expression of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin and β-catenin and upregulate mesenchymal proteins like fibronectin and vimentin in multiple cell lines, indicative of increased cell motility. Since nicotine induces ID1 expression and also fibronectin and vimentin expression, we further investigated if ID1 can induce expression of these mesenchymal proteins. A549 cells were transiently transfected with a fibronectin promoter-luciferase reporter construct and an ID1 expression vector. Cotransfection of ID1 resulted in the induction of the promoter in a dose-dependent manner, as seen by luciferase assays. There was a 5-fold increase in the luciferase activity when 2 μg of fibronectin promoter was cotransfected with 4 μg of ID1. Vimentin promoter was also induced by ID1 in A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8A). Similar induction of fibronectin and vimentin reporters was observed in H1650 cells as well, when transfected with increasing amounts of ID1 (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

ID1 regulates the expression of mesenchymal markers vimentin and fibronectin. ID1 could induce fibronectin and vimentin promoter in a dose-dependent manner when transient transfections were conducted in A549 and H1650 cells (A and B). Depletion of ID1 by siRNAs resulted in inhibition of nicotine- and EGF-induced expression of vimentin and fibronectin as seen by Western blots (C). Nicotine- and EGF-induced vimentin and fibronectin promoter activity was abrogated when treated with α-bungarotoxin, PP2, LY compound, and gefitinib, indicating the involvement of α7 subunit of nAChR, Src, PI3K, and EGFR in fibronectin and vimentin expression (D).

To further confirm the involvement of ID1 in nicotine- and EGF-induced expression of vimentin and fibronectin, ID1 levels were depleted in A549 cells by transfecting an ID1 siRNA; cells transfected with a control siRNA or ID1 siRNA were stimulated with either nicotine or EGF for 24 h. Control siRNA-transfected cells showed upregulation of vimentin and fibronectin while ID1-depleted cells did not show induction of vimentin and fibronectin (Fig. 8C), as seen in Western blot analysis. To examine whether Src, PI3K, α7 subunit of nAChR, and EGFR are involved in nicotine- or EGF-induced vimentin and fibronectin expression, we transiently transfected cells with vimentin or fibronectin promoter constructs, serum starved and induced with nicotine or EGF in the presence of inhibitors such as α-bungarotoxin, PP2, LY294002, dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE α3/β2 and α4/β2 subunit inhibitor), and gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor). Nicotine-mediated promoter induction was significantly ablated by α7 subunit antagonist α-BT, Src inhibitor PP2, and LY compound, while DHβE did not significantly affect promoter induction, suggesting that expression of vimentin and fibronectin is primarily mediated by α7 subunit of nAChR, Src, and PI3K. EGF-induced vimentin and fibronectin promoter induction was abrogated by gefitinib, PP2, and LY294002, confirming the involvement of EGFR, Src, and PI3K in the expression of these genes (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that ID1 can mediate the expression of the mesenchymal proteins fibronectin and vimentin at the transcriptional level in response to nicotine as well as EGF stimulation.

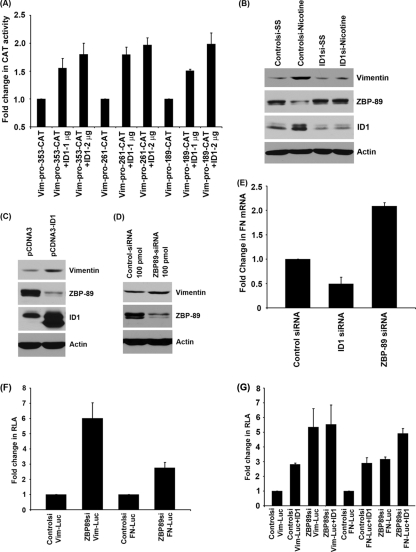

ID1 regulates vimentin and fibronectin expression by repressing ZBP-89.

We further explored the mechanism by which ID1 regulates vimentin and fibronectin expression. To identify the ID1-responsive region of the vimentin promoter, transient-transfection experiments were conducted using vimentin promoter constructs fused to the CAT gene (vim-pro-CAT-353, vim-pro-CAT-261, and vim-pro-CAT-189) along with different amounts of ID1 (1 and 2 μg). We observed that even the shorter promoter construct (vim-pro-CAT-189) was transcriptionally induced by ID1 (Fig. 9A). We performed a promoter analysis using the Genomatix MatInspector program to identify the transcription factors that can bind to this region of vimentin promoter. The promoter analysis results revealed several putative binding sites of a previously reported repressor of vimentin, ZBP-89, on the proximal promoter of vimentin. Previous studies have demonstrated that ZBP-89, a zinc finger, Kruppel-like protein, represses vimentin gene expression by interacting with the transcriptional activator Sp1 and also by recruiting histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) (68, 71). To examine whether ID1 could be inducing vimentin by repressing the expression of ZBP-89, A549 cells were transfected with a control siRNA or ID1 siRNA, serum starved, and subsequently induced with nicotine. Control siRNA-transfected cells showed downregulation of ZBP-89 in response to nicotine stimulation, resulting in enhanced vimentin expression, while ID1-transfected cells had larger amounts of ZBP-89, leading to low levels of vimentin (Fig. 9B). Conversely, overexpression of ID1 by transfecting an ID1 expression vector resulted in the downregulation of ZBP-89 with a corresponding upregulation of vimentin (Fig. 9C), strongly suggesting that ID1 regulates vimentin expression by repressing ZBP-89. Depletion of ZBP-89 by siRNA transfection resulted in elevated expression of vimentin (Fig. 9D), confirming previous results (71).

Fig. 9.

Regulation of vimentin promoter by ID1. (A) Vimentin promoter constructs (vim-pro-CAT-353, -261, and -189) were transcriptionally induced by ID1. (B) Depletion of ID1 results in upregulation of ZBP-89 and downregulation of vimentin. (C) Transient transfection of A549 cells with ID1 expression vector showed downregulation of ZBP-89, which leads to higher vimentin expression. (D) Depletion of ZBP-89 using siRNA also resulted in upregulation of vimentin. (E) Depletion of ID1 resulted in lower levels of fibronectin mRNA, while depletion of ZBP-89 showed elevated levels of fibronectin mRNA, indicating the role of ID1 in regulating fibronectin expression by downregulating ZBP-89. (F) Vimentin and fibronectin promoter activity in ZBP-89-depleted cells was higher than that from the control siRNA-transfected cells. (G) ZBP-89-depleted cells did not show ID1-induced vimentin promoter activity, while fibronectin promoter activity was further induced by ID1 in ZBP-89-depleted cells.

A similar Genomatix MatInspector program analysis revealed that a number of probable binding sites for ZBP-89 were present in fibronectin promoter as well. To determine the role of ZBP-89 in the regulation of fibronectin expression, A549 cells were transfected with control siRNA, ID1 siRNA, or ZBP-89 siRNA. ID1-downregulated cells showed a reduction in fibronectin expression as seen by real-time PCR, while depletion of ZBP-89 showed upregulation of fibronectin (Fig. 9E), indicating that ZBP-89 might be a transcriptional repressor of fibronectin as well.

To further confirm the role of ZBP-89 in the regulation of vimentin and fibronectin, transient transfections using vimentin and fibronectin promoter-luciferase constructs were done in cells transfected with a control siRNA or siRNA to ZBP-89. When ZBP-89 was depleted, there was increased transcription from both the promoters (Fig. 9F), confirming a role for ZBP-89 in the regulation of these promoters.

To further confirm whether ZBP-89 plays a role in ID1-mediated induction of these promoters, cells were first transfected with a control siRNA or siRNA to ZBP-89 and subsequently transfected with vimentin or fibronectin promoter construct with or without ID1. It was found that cotransfection of ID1 with control siRNA led to an induction of vimentin promoter. Similarly, transfection of ZBP-89 siRNA also stimulated vimentin promoter; there was no further induction of vimentin when ID1 was cotransfected with ZBP-89 siRNA, suggesting that ZBP-89 is the main and probably sole mediator of ID1-mediated induction of vimentin expression. Similar results were obtained with the fibronectin promoter; however, there was an increase in transcriptional activity of fibronectin promoter when ID1 was cotransfected with ZBP-89 siRNA, indicating that this protein may not be the sole facilitator of ID1-mediated induction of fibronectin (Fig. 9G). These experiments suggest that ID1 might be inducing these promoters through the mediation of ZBP-89.

ID1 expression levels correlate with levels of fibronectin, vimentin, and α7 subunit of nAChR in lung tumor tissues from patients.

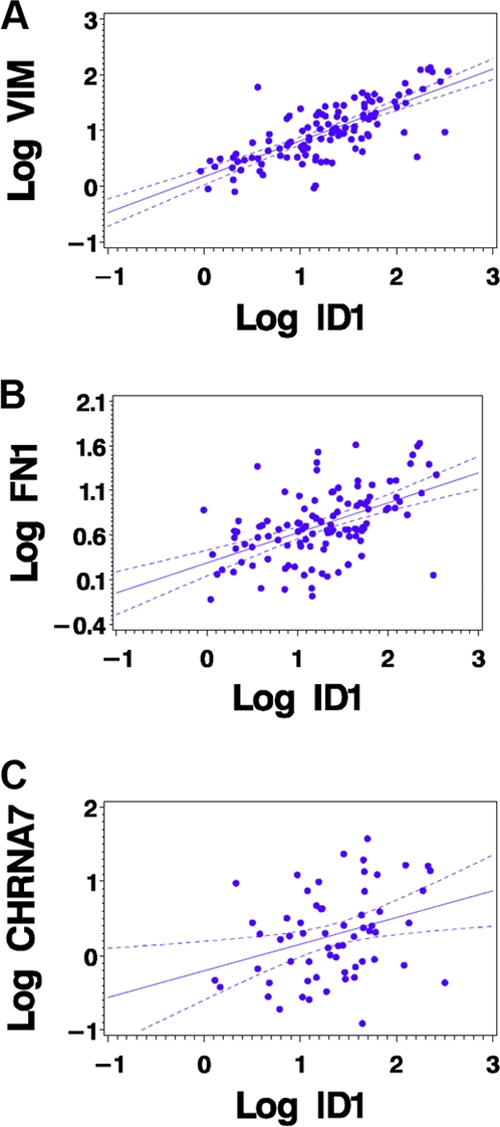

It has been reported that nicotine stimulation of a variety of cells can lead to the induction of fibronectin and vimentin, which are mesenchymal genes that promote the early metastatic steps of cancers. Given the observations that ID1 expression is induced by both nAChR and EGFR signaling, that ID1 is involved in invasion and migration of cells, and that ID1 is overexpressed in metastatic cancers, we next examined whether the expression of ID1 in human lung tumor samples correlates with levels of vimentin, fibronectin, and the α7 subunit of nAChR. Quantitative RT-PCR performed on 117 patient samples (68 males, 49 females) revealed a significant association of ID1 with these genes. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 10, ID1 expression showed a very strong positive correlation with vimentin (r = 0.75; P < 0.0001) and fibronectin (r = 0.52; P < 0.0001), which are the mesenchymal markers overexpressed in more aggressive tumors. There was a positive correlation of ID1 expression with that of the α7 subunit of nAChR (CHRNA7, n = 61, r = 0.32; P = 0.0114) in the samples analyzed. This indicates that ID1 expression is regulated by nAChR signaling in NSCLC.

Table 1.

Association of ID1 with vimentin, fibronectin, and α7 subunit of nAChR (CHRNA7)

| Protein | Pearson correlation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vimentin | Fibronectin | ID1 | α7 nAChR (CHRNA7) | |

| Vimentin | 1; n = 117 | r = 0.70; P < 0.0001; n = 117 | r = 0.75; P < 0.0001; n = 117 | r = 0.37; P = 0.0033; n = 61 |

| Fibronectin | 1 | r = 0.52; P < 0.0001; n = 117 | r = 0.35; P = 0.0056; n = 61 | |

| ID1 | 1 | r = 0.32; P = 0.0114; n = 61 | ||

| α7 nAChR (CHRNA7) | 1; n = 61 | |||

Fig. 10.

Scatter plots showing the correlations of ID1 with vimentin (A), fibronectin (B), and α7 nAChR (C).

We next examined whether ID1 levels are associated with pathological stages of the tumor samples analyzed. We observed that vimentin, fibronectin, and ID1 levels were significantly associated with pathological stage, with all P values being ≤0.006. Of the 117 tumors analyzed, 94 were grouped as pathological stage I (IA, n = 46; IB, n = 48); the remaining 23 were IIA (n = 1), IIB (n = 10), IIIA (n = 3), IIIB (n = 2), and IV (n = 7). An elevated level of ID1 was significantly associated with later stages of lung tumors (stages IIA, IIB, IIIA, IIIB, and IV) compared to early pathological stage (stages IA and IB), with a P value of 0.006. Similarly, higher vimentin and fibronectin levels were observed in later-stage tumors than in early-stage tumors (P = 0.004 and 0.0037, exact normal scores test; Table 2). We also analyzed the association of smoking status of the patients with expression levels of ID1, vimentin, and fibronectin. There were tumor samples from 29 active smokers, 8 never-smokers, and 66 patients who quit smoking. No significant association was observed between expression of these genes and smoking history (pack-years) and disease-free survival (data not shown); this is probably because ID1 expression is elevated in NSCLC in both smokers and nonsmokers. These observations strongly support our contention that ID1 is a common mediator of NSCLC genesis and progression in both smokers and nonsmokers.

Table 2.

Association of ID1, vimentin, fibronectin, and α7 subunit of nAChR (CHRNA7) expression levels with pathological stage

| Gene by pathological stage (IA or IB vs others) | Exact normal scores test (P value) |

|---|---|

| ID1 | 0.006 |

| Vimentin | 0.004 |

| Fibronectin | 0.0037 |

| CHRNA7 | 0.172 |

DISCUSSION

ID proteins play a major role in controlling the proliferation and differentiation of cells by interfering with the DNA binding activity of bHLH transcription factors (2, 27). The ID family of proteins (ID1, ID2, ID3, and ID4), which lack a DNA binding domain, are negative regulators of bHLH transcription factors (45). They exert their control by associating with basic HLH proteins as homo- or heterodimers and prevent them from binding to DNA (2). ID1 has been implicated in regulating a variety of cellular processes, including growth, senescence, differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and neoplastic transformation (3). A number of studies have suggested several mechanisms for cell cycle progression by ID1, including inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors such as p16, p21, and p27, leading to Rb phosphorylation and subsequent cell cycle progression (12, 42, 45, 46). In spite of the similar structures and functional bases for the four ID proteins, they play different regulatory roles throughout embryonic development and tumorigenesis. ID1 and ID3 are involved in angiogenesis during embryogenesis and after birth (1, 2). Their crucial role in tumor angiogenesis is evident in the tumor xenograft studies conducted on double-knockout mice, which failed to develop proper tumor vasculature (2, 34). ID2/Rb interaction is a well-established ID regulatory mechanism, and overexpression of ID2 has been shown to increase cell proliferation and cell cycle progression (45). ID4, on the other hand, is mostly involved in neurogenesis during embryonic development (49). Unlike other family members, ID4 has been suggested to have tumor suppressor properties in some cancers. Overexpression of ID4 has been shown to be associated with development of metastases in prostate cancer (5).

ID1's proliferative and antiapoptotic functions have been correlated with the onset and progression of a variety of human tumors, including those of mammary gland and pancreas (28); indeed, its overexpression is significantly associated with increased tumor angiogenesis and worse prognosis in these cancers (3, 33). It has been shown that ID1 was essential for the metastasis of cancers to the lung in mouse models of cancer (13, 18). Studies on cultured cells and mouse models have shown that levels of ID1 correlate with invasive as well as metastatic properties of cancer cells and that transfection of ID1 could make human breast cancer cells significantly more aggressive and metastatic (32). ID1 upregulation has been strongly correlated with increased EGFR expression and bladder cancer invasion (11). ID1 has been found to be activated by Src as well as EGFR (11, 14, 30).

Though dysregulation of ID proteins has been observed in many types of cancers, there is little information on whether ID1 or other family members contribute to the onset and progression of NSCLC. Here, we provide evidence that ID1 is a major mediator of NSCLC progression and metastasis, irrespective of the underlying mutations in EGFR or K-Ras genes. The facts that ID1 expression is regulated by signaling altered in lung cancer and that ID1 can in turn affect the expression and function of proteins involved in tumor angiogenesis lead us to believe that ID1 could be playing a major role in the genesis and progression of these cancers. Our earlier studies have shown that exposure of cells to nicotine induces Src activation, which is an important upstream signaling event that mediates Rb–Raf-1 binding upon nicotine stimulation (8). It appears that induction of ID1 is another event downstream of Src that promotes the proliferation and invasion of cells in response to these agents. The finding that both nicotine and EGF can induce the expression of ID1 in a Src-dependent manner raises the possibility that ID1 might be contributing to oncogenesis in smokers and nonsmokers. Our results showing that ID1 is involved in tumor cell migrations are in agreement with a recent study showing that ID1 promotes tumor cell migration in NSCLC (4). Several studies have shown that the decrease in E-cadherin and β-catenin with a concurrent increase in fibronectin and vimentin levels is one of the hallmarks of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells (24). Earlier studies from our lab showed that nicotine induces changes consistent with EMT such as upregulation of mesenchymal proteins like vimentin and fibronectin (9). In the present study, we observed strong positive correlations of ID1 with mesenchymal markers vimentin and fibronectin and also with the α7 subunit of nAChR in human tumor samples. Further, ID1, vimentin, and fibronectin levels were elevated in tumors of advanced pathological stage. Association of the increased expression of these proteins with malignant characteristics of the cells indicates possible roles played by ID1 in the expression of these genes. We also observed that the expression of vimentin and fibronectin is regulated by ID1 at transcriptional level, by downregulating ZBP-89, which is a transcriptional repressor of vimentin and fibronectin (68, 71). Recent studies have revealed that ZBP-89 regulates multiple aspects of tumor development, including cell proliferation and apoptosis (70), and our results raise the possibility that a variety of signals that target ID1 might modulate this protein. In conclusion, the observation that ID1 is overexpressed in metastatic NSCLC along with the in vitro studies strongly suggests an important role for ID1 in the genesis and progression of NSCLC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support of the Moffitt Cancer Center Lung SPORE as well as Shared Resources is greatly appreciated. These studies were supported by grant CA139612 from the NCI to S.P.C.

We thank Michelle Kovacs and Shilpa Mikkilineni for their technical support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alani R. M., Silverthorn C. F., Orosz K. 2004. Tumor angiogenesis in mice and men. Cancer Biol. Ther. 3:498–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benezra R. 2001. Role of Id proteins in embryonic and tumor angiogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 11:237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benezra R., Rafii S., Lyden D. 2001. The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene 20:8334–8341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhattacharya R., Kowalski J., Larson A. R., Brock M., Alani R. M. 2010. Id1 promotes tumor cell migration in nonsmall cell lung cancers. J. Oncol. 2010:856105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carey J. P., Asirvatham A. J., Galm O., Ghogomu T. A., Chaudhary J. 2009. Inhibitor of differentiation 4 (Id4) is a potential tumor suppressor in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 9:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dasgupta P., Chellappan S. P. 2006. Nicotine-mediated cell proliferation and angiogenesis: new twists to an old story. Cell Cycle 5:2324–2328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dasgupta P., et al. 2006. Nicotine inhibits apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs by up-regulating XIAP and survivin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:6332–6337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dasgupta P., et al. 2006. Nicotine induces cell proliferation by beta-arrestin-mediated activation of Src and Rb-Raf-1 pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 116:2208–2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dasgupta P., et al. 2009. Nicotine induces cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a variety of human cancer cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 124:36–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis R., et al. 2009. Nicotine promotes tumor growth and metastasis in mouse models of lung cancer. PLoS One 4:e7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ding Y., et al. 2006. Significance of Id-1 up-regulation and its association with EGFR in bladder cancer cell invasion. Int. J. Oncol. 28:847–854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Everly D. N., Jr., Mainou B. A., Raab-Traub N. 2004. Induction of Id1 and Id3 by latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus and regulation of p27/Kip and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in rodent fibroblast transformation. J. Virol. 78:13470–13478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gao D., et al. 2008. Endothelial progenitor cells control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis. Science 319:195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gautschi O., et al. 2008. Regulation of Id1 expression by SRC: implications for targeting of the bone morphogenetic protein pathway in cancer. Cancer Res. 68:2250–2258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilles C., et al. 2003. Transactivation of vimentin by beta-catenin in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 63:2658–2664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gotti C., Clementi F. 2004. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology. Prog. Neurobiol. 74:363–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greulich H., et al. 2005. Oncogenic transformation by inhibitor-sensitive and -resistant EGFR mutants. PLoS Med. 2:e313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta G. P., et al. 2007. ID genes mediate tumor reinitiation during breast cancer lung metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:19506–19511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heeschen C., et al. 2001. Nicotine stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth and atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 7:833–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heeschen C., Weis M., Aicher A., Dimmeler S., Cooke J. P. 2002. A novel angiogenic pathway mediated by non-neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 110:527–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Irmer D., Funk J. O., Blaukat A. 2007. EGFR kinase domain mutations—functional impact and relevance for lung cancer therapy. Oncogene 26:5693–5701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jemal A., et al. 2009. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J. Clin. 59:225–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson D. H., Schiller J. H. 2002. Novel therapies for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother. Biol. Response Modif. 20:763–786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalluri R. 2009. EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J. Clin. Invest. 119:1417–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lam D. C., et al. 2007. Expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes in non-small-cell lung cancer reveals differences between smokers and nonsmokers. Cancer Res. 67:4638–4647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lasorella A., Noseda M., Beyna M., Yokota Y., Iavarone A. 2000. Id2 is a retinoblastoma protein target and mediates signalling by Myc oncoproteins. Nature 407:592–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lasorella A., Uo T., Iavarone A. 2001. Id proteins at the cross-road of development and cancer. Oncogene 20:8326–8333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee K. T., et al. 2004. Overexpression of Id-1 is significantly associated with tumour angiogenesis in human pancreas cancers. Br. J. Cancer 90:1198–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li B., et al. 2009. Id-1 promotes tumorigenicity and metastasis of human esophageal cancer cells through activation of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Int. J. Cancer 125:2576–2585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li X., et al. 2007. Prognostic significance of Id-1 and its association with EGFR in renal cell cancer. Histopathology 50:484–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Light W., Vernon A. E., Lasorella A., Iavarone A., LaBonne C. 2005. Xenopus Id3 is required downstream of Myc for the formation of multipotent neural crest progenitor cells. Development 132:1831–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lin C. Q., et al. 2000. A role for Id-1 in the aggressive phenotype and steroid hormone response of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 60:1332–1340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ling M. T., et al. 2005. Overexpression of Id-1 in prostate cancer cells promotes angiogenesis through the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Carcinogenesis 26:1668–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lyden D., et al. 1999. Id1 and Id3 are required for neurogenesis, angiogenesis and vascularization of tumour xenografts. Nature 401:670–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Massari M. E., Murre C. 2000. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:429–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Minna J. D. 2003. Nicotine exposure and bronchial epithelial cell nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 111:31–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mukhin A. G., et al. 2008. Greater nicotinic acetylcholine receptor density in smokers than in nonsmokers: a PET study with 2-18F-FA-85380. J. Nucl. Med. 49:1628–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nicholson R. I., et al. 2001. Modulation of epidermal growth factor receptor in endocrine-resistant, oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 8:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishimine M., et al. 2003. Id proteins are overexpressed in human oral squamous cell carcinomas. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 32:350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nishiyama K., et al. 2005. Id1 gene transfer confers angiogenic property on fully differentiated endothelial cells and contributes to therapeutic angiogenesis. Circulation 112:2840–2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Norton J. D. 2000. ID helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J. Cell Sci. 113:3897–3905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Norton J. D., Atherton G. T. 1998. Coupling of cell growth control and apoptosis functions of Id proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2371–2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ohtani N., et al. 2001. Opposing effects of Ets and Id proteins on p16INK4a expression during cellular senescence. Nature 409:1067–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paleari L., et al. 2008. Role of alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in human non-small cell lung cancer proliferation. Cell Prolif. 41:936–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45. Perk J., Iavarone A., Benezra R. 2005. Id family of helix-loop-helix proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5:603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prabhu S., Ignatova A., Park S. T., Sun X. H. 1997. Regulation of the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 by E2A and Id proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5888–5896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Richardson G. E., et al. 1993. Smoking cessation after successful treatment of small-cell lung cancer is associated with fewer smoking-related second primary cancers. Ann. Intern. Med. 119:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rothschild S. I., et al. 2011. The stem cell gene “inhibitor of differentiation 1” (ID1) is frequently expressed in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 71:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ruzinova M. B., Benezra R. 2003. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 13:410–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schell M., Singh B. 1997. The reduced monotonic regression method. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 92:128–135 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schuller H. M. 2009. Is cancer triggered by altered signalling of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors? Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schuller H. M., Jull B. A., Sheppard B. J., Plummer H. K. 2000. Interaction of tobacco-specific toxicants with the neuronal alpha(7) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and its associated mitogenic signal transduction pathway: potential role in lung carcinogenesis and pediatric lung disorders. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 393:265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sharma G., Vijayaraghavan S. 2002. Nicotinic receptor signaling in nonexcitable cells. J. Neurobiol. 53:524–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sharma S. V., Bell D. W., Settleman J., Haber D. A. 2007. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7:169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sikder H., et al. 2003. Disruption of Id1 reveals major differences in angiogenesis between transplanted and autochthonous tumors. Cancer Cell 4:291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sikder H. A., Devlin M. K., Dunlap S., Ryu B., Alani R. M. 2003. Id proteins in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 3:525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Singh J., Murata K., Itahana Y., Desprez P. Y. 2002. Constitutive expression of the Id-1 promoter in human metastatic breast cancer cells is linked with the loss of NF-1/Rb/HDAC-1 transcription repressor complex. Oncogene 21:1812–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Soh J., et al. 2008. Sequential molecular changes during multistage pathogenesis of small peripheral adenocarcinomas of the lung. J. Thorac. Oncol. 3:340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sos M. L., et al. 2009. PTEN loss contributes to erlotinib resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer by activation of Akt and EGFR. Cancer Res. 69:3256–3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sun S., Schiller J. H., Gazdar A. F. 2007. Lung cancer in never smokers—a different disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7:778–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Swarbrick A., et al. 2005. Regulation of cyclin expression and cell cycle progression in breast epithelial cells by the helix-loop-helix protein Id1. Oncogene 24:381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Swope S. L., Huganir R. L. 1994. Binding of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor to SH2 domains of Fyn and Fyk protein tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29817–29824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Swope S. L., Qu Z., Huganir R. L. 1995. Phosphorylation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by protein tyrosine kinases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 757:197–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tam I. Y., et al. 2006. Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin. Cancer Res. 12:1647–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Villablanca A. C. 1998. Nicotine stimulates DNA synthesis and proliferation in vascular endothelial cells in vitro. J. Appl. Physiol. 84:2089–2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Volpert O. V., et al. 2002. Id1 regulates angiogenesis through transcriptional repression of thrombospondin-1. Cancer Cell 2:473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wessler I., Kirkpatrick C. J., Racke K. 1998. Non-neuronal acetylcholine, a locally acting molecule, widely distributed in biological systems: expression and function in humans. Pharmacol. Ther. 77:59–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wu Y., Zhang X., Salmon M., Zehner Z. E. 2007. The zinc finger repressor, ZBP-89, recruits histone deacetylase 1 to repress vimentin gene expression. Genes Cells 12:905–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yamamoto H., et al. 2008. PIK3CA mutations and copy number gains in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 68:6913–6921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang C. Z., Chen G. G., Lai P. B. 2010. Transcription factor ZBP-89 in cancer growth and apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1806:36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang X., Diab I. H., Zehner Z. E. 2003. ZBP-89 represses vimentin gene transcription by interacting with the transcriptional activator, Sp1. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:2900–2914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zheng Y., Ritzenthaler J. D., Roman J., Han S. 2007. Nicotine stimulates human lung cancer cell growth by inducing fibronectin expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 37:681–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]