Abstract

Centromeres serve as platforms for the assembly of kinetochores and are essential for nuclear division. Here we identified Neurospora crassa centromeric DNA by chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) of DNA associated with tagged versions of the centromere foundation proteins CenH3 (CENP-A) and CEN-C (CENP-C) and the kinetochore protein CEN-T (CENP-T). On each chromosome we found an ∼150- to 300-kbp region of enrichment for all three proteins. These regions correspond to intervals predicted to be centromeric DNA by genetic mapping and DNA sequence analyses. By ChIP-seq we found extensive colocalization of CenH3, CEN-C, CEN-T, and histone H3K9 trimethylation (H3K9me3). In contrast, H3K4me2, which has been found at the cores of plant, fission yeast, Drosophila, and mammalian centromeres, was not enriched in Neurospora centromeric DNA. DNA methylation was most pronounced at the periphery of centromeric DNA. Mutation of dim-5, which encodes an H3K9 methyltransferase responsible for nearly all H3K9me3, resulted in altered distribution of CenH3-green fluorescent protein (GFP). Similarly, CenH3-GFP distribution was altered in the absence of HP1, the chromodomain protein that binds to H3K9me3. We conclude that eukaryotes with regional centromeres make use of different strategies for maintenance of CenH3 at centromeres, and we suggest a model in which centromere proteins nucleate at the core but require DIM-5 and HP1 for spreading.

INTRODUCTION

Centromeres serve critical functions in genome stability and replication, yet their assembly, maintenance, and roles throughout some phases of the cell cycle (e.g., interphase) are still poorly understood. A major impediment to the study of centromeres in many organisms is their identification. In general, centromeric DNA sequences are AT rich and repetitive, making them difficult to sequence and assemble. While critical for survival, they are also rapidly evolving, perhaps driven by a proposed mechanism for centromere-mediated meiotic drive suppression (22, 41, 57, 58). Therefore, centromeric DNA sequences may be highly divergent even between closely related organisms and must be identified biochemically in each species. A functional definition for centromeric regions is the presence of a centromere-specific histone H3 variant, CenH3 (CENP-A), in place of H3.

Among fungi, centromere sequences have been functionally or biochemically identified in the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae (reviewed in reference 38) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (87) and the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans (65, 76). The centromeres of filamentous fungi have been difficult to assemble and are absent or not easily recognizable by bioinformatic tools in the almost completely sequenced and assembled genomes of Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph: Gibberella zeae) (20), Aspergillus fumigatus (26), Nectria haematococca (18), and even the one filamentous fungus for which there is a predicted “telomere-to-telomere” assembly, Mycosphaerella graminicola (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycgr3/Mycgr3.info.html).

Neurospora crassa produces octads of ordered ascospores, which made this organism attractive to early geneticists for constructing linkage maps. By relation to other markers on each linkage group (LG), Neurospora centromeres were mapped relatively early by classical genetics (2, 66). Representative centromeric DNA sequences from LG VII obtained from a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) library revealed a collection of AT-rich, inactivated transposons and simple sequence repeats, e.g., Tsp, Sma, and TTA repeats (11, 15). Neurospora lab strains contain few if any known active transposable elements (TEs), the exception being a LINE-like element called Tad, restricted to a single wild-collected strain, N. crassa Adiopodoume (12). Indeed, TEs found within the Cen VII sequence were mostly deactivated Tad segments (dTad) and relics of retrotransposons, e.g., copia-like segments (Tcen) and gypsy-like segments (Tgl1). Later studies of the methylated component (80) and subtelomeric regions (83, 94) of the Neurospora genome revealed that these elements (e.g., Tcen) are not centromere specific but rather can be found at subtelomeric regions and dispersed AT-rich heterochromatic regions on each chromosome arm.

The Neurospora draft genome sequence (33) contained large, presumably centromeric contigs of AT-rich, repetitive DNA on scaffolds several dozen kilobase pairs in length, sometimes at the edges of longer scaffolds. This sequence composition suggested that Neurospora has more complex centromeres than the three hemiascomycete fungi discussed above, reminiscent of the assembly of retrotransposons and other repeat elements found in higher eukaryotes, e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana (81), Oryza sativa (62), Zea mays (93), Drosophila melanogaster (86), and Homo sapiens (73, 77).

What makes Neurospora a uniquely suited organism to help in understanding the interplay between repeated centromeric DNA and epigenetic deposition of centromere proteins is the structure of Neurospora's “near-repeat” units. Whereas satellite repeats—predominately homogeneous arrays of ∼170-nucleotide (nt) AT-rich DNA units—make up most plant and animal centromeric DNA (17, 50), Neurospora repeats are heterogeneous due to the activity of a region-specific premeiotic mutator phenomenon called “repeat-induced point mutation” (RIP). The RIP machinery detects duplicated DNA between fertilization and karyogamy and induces C-to-T transition mutations in both (or all) copies of a repeat element (for a review, see reference 79). Because the percentage of Cs that are mutated and the positions of Cs targeted on each strand differ in each copy of a repeated segment, the resulting sequences are no longer identical repeats. The RIP process continues with diminished efficacy until the near-repeats have identities below ∼80% of their DNA sequence. If previously mutated segments are again duplicated, the process starts over and continues to deplete Cs from the duplicated segments (13). Mutated copies of nonfunctional transposons are under no known selective pressure, which presumably allows drift and accumulation of additional random mutations, now a mixture of transitions and transversions. The result is a collection of AT-rich, divergent sequences that can still be recognized as ancestral transposable elements, yet each copy of the repeat family differs sufficiently from all others to make almost all of the DNA sequence unique at the level of 36-mer reads typically used with first-generation Illumina sequencing. Therefore, we can use technologies that rely on DNA sequence differences between subdomains of centromeric DNA, which is still difficult or currently not possible in other organisms with large homogeneous arrays of repeats.

The most recent reference genome of N. crassa (“finished” assembly 10; http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/neurospora/Regions.html) contains seven supercontigs, corresponding to seven LGs, as well as 13 smaller subcontigs, corresponding largely to ribosomal DNA (rDNA) or short repeat regions mutated by RIP. In this assembly, each LG contains a single ∼150- to 300-kb region of AT-rich, repetitive DNA at positions corresponding to the previously mapped centromeres (Cen I to Cen VII; see reference 67), but each LG still contains several sequence gaps, which makes it formally possible that repetitive centromere core sequences are still not completely assembled.

Here we analyzed the large AT-rich repetitive regions for the presence of satellite-type repeats but found none. We next asked if these regions are indeed centromeric sequences and what epigenetic marks are associated with them. To address these questions, we employed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of three reliably centromere-specific proteins, CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T, followed by high-throughput sequencing (HTS) of associated DNA, a process called “ChIP-seq” (45, 59–61). CenH3, which replaces canonical H3 at centromeric nucleosomes, and CEN-C, which presumably interacts with both CenH3 and centromeric DNA, direct the assembly of dozens of other proteins that form the kinetochore (7, 14, 91). One inner kinetochore protein, CEN-T, was investigated as further evidence of kinetochore location. Neurospora CEN-T is a homolog of CENP-T, a component of the CENP-A centromeric nucleosome-associated complex required for CENP-A targeting (30, 39, 44).

Neurospora CenH3 was associated with almost the entire AT-rich region on each chromosome, and CEN-C and CEN-T colocalized with CenH3 except at the centromere peripheries. To our surprise, we found the heterochromatic mark H3K9me3 overlapping the entire CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T-enriched region. Smaller regions enriched with H3K9me3 and cytosine DNA methylation at the edge of each Neurospora centromere we define as pericentric heterochromatin. Euchromatic marks (e.g., H3K4me2 and H3K4me3) found at centromere cores in other systems were absent from Neurospora centromeric and pericentric regions. Finally, in contrast to what has been found in fission yeast (28, 46), heterochromatin is required for normal distribution of CenH3 at the centromere cores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Neurospora strains.

Neurospora strains were maintained, grown, and crossed according to standard procedures (21). To introduce epitope tags on CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T, we made constructs for homologous gene replacement based on pZero-GFP-loxP-hph-loxP (43). Replacement cassettes with the selectable hygromycin (Hyg) resistance marker (hph) were generated by fusion PCR. The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the cen-T gene were amplified from genomic DNA of NMF39 (Table 1 ) with the primers 1797 and 1798 and with 1799 and 1800, respectively (Table 2 ). A fragment containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and hph was amplified from pZero-GFP-loxP-hph-loxP with the primers 83 and 84. The 5′ and 3′ flanks were fused with the GFP-hph cassette by PCR with the hph split marker primers 1053 and 1054. Generation of tag constructs for CenH3 and CEN-C was similar and is described in detail elsewhere (P. A. Phatale, K. M. Smith, J. Mendoza, L. R. Connolly, E. U. Selker, and M. Freitag, unpublished data). Strain N3011 (Table 1) was the transformation host for all constructs. Transformants were generated by electroporation as described previously (19). Hygromycin-resistant (Hyg+) colonies were picked and screened for GFP. Southern analyses confirmed correct integration of the GFP tags. For CenH3 and CEN-C, heterokaryotic Hyg+ transformants were crossed to NMF160 to generate NMF166 and NMF225, respectively. NMF166 was crossed to N3074 (dim-5) to obtain NMF238 (dim-5), NMF239 (dim-5), NMF240 (dim-5), and NMF241 (dim+). The primary transformant TKS71.2 was crossed with N2552 (hpo) to generate NMF232. NMF233 is an hpo+ sibling of NMF232. All known strain genotypes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Neurospora strains used in this study

| Strain no. | Genotype | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| NMF39 | mat A | FGSC2489 |

| N3011 | mat a his-3; mus-51::bar+ | FGSC9538 |

| N3074 | mat A; Δdim-5::bar+; trp-2 | 53 |

| N2552 | mat A his-3+:hpoRIP-sgfp−; hpoRIP2 | 31 |

| NMF160 | mat A; ΔSad-2::hph+ | This study |

| NMF166 | mat a his-3; hH3v-gfp-loxP-hph-loxP; ΔSad-2::hph+ | This study |

| NMF168 | mat a his-3; hH3v-gfp-loxP-hph-loxP | This study |

| NMF169 | mat a his-3; hH3v-gfp-loxP-hph-loxP | This study |

| NMF225 | mat A; cen-c-gfp-lox-hph-lox | This study |

| NMF229 | mat A; hH3v-flag-lox-hph-lox | This study |

| NMF232 | mat a; hH3v-gfp-lox-hph-lox; hpoRIP2 | This study |

| NMF233 | mat a; hH3v-gfp lox-hph-lox; hpo+ | This study |

| NMF238 | mat A; hH3v-gfp-lox-hph-lox; Δdim-5::bar+ | This study |

| NMF239 | mat A; hH3v-gfp-lox-hph-lox; Δdim-5::bar+ | This study |

| NMF240 | mat A; hH3v-gfp-lox-hph-lox; Δdim-5::bar+ | This study |

| NMF241 | mat A; hH3v-gfp-lox-hph-lox; dim-5+ | This study |

| NMF399a | mat a his-3; cen-T-gfp-lox-hph-lox; mus-51::bar+ | This study |

| TKS71.2a | mat a his-3; hH3v-gfp-lox-hph-lox; mus-51::bar+ | This study |

Heterokaryotic transformant.

FGSC, Fungal Genetics Stock Center.

Table 2.

Primers

| Function | Primer no. | Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain construction | 83 | GlyF | GGCGGAGGCGGCGGAGGCGGAGGCGGAGG |

| 84 | loxp-R | CGAGCTCGGATCCATAACTTCGTATAGCA | |

| 1053 | hphSM-F | AAAAAGCCTGAACTCACCGCGACG | |

| 1054 | hphSM-R | TCGCCTCGCTCCAGTCAATGACC | |

| 1797 | 2161GlyR | CCTCCGCCTCCGCCTCCGCCGCCTCCGCCCGTCACCTCTTCGTCTTCGCC | |

| 1798 | 2161GlyF | AGTGATGGGATCGATTCGGGG | |

| 1799 | 2161loxR | TGTCCTGATTGAGTCCCAACC | |

| 1800 | 2161loxF | TGCTATACGAAGTTATGGATCCGAGCTCGGAGTGTTTGTTACCATTGATG | |

| Region-specific ChIP-PCR analysis | 911 | CenVII_Rep1F | ATGGAGACAGCTCCGGTCGTGACC |

| 910 | CenVII_Rep1R | TAGACAATTGTACGACGTAGAG | |

| 917 | CenVII_Rep3F | GGATAAGTGTTGGTGGGTCTCTGG | |

| 924 | CenVII_Rep3R | GCGCCTTGTTGAAATTAGCAATTA | |

| 914 | CenVII_Rep4F | ACTTGGTCATTTTTTGGACTTGG | |

| 918 | CenVII_Rep4R | CAATGTTAGGTGTCATCGGCTGTC | |

| 940 | CenVII_Rep8F | GGACTTTGTGTGGGATCACCAACGC | |

| 933 | CenVII_Rep8R | CGCCAAATTCGTTAAATTAATCGG | |

| 928 | CenVII_Rep9F | GTTAGAAAGGGTTTATAACTTGTG | |

| 929 | CenVII_Rep9R | GGTTTTGGAGCCGGGTCGGGTCC | |

| 1105 | LGIV_Rep1F | GTATTTGATAATGAGACACTTCTC | |

| 1106 | LGIV_Rep1R | ATCATTTATAGACGGAATTTTACC | |

| 1107 | LGIV_Rep2F | GCTGGGGAACAAGGCGTATAAAGG | |

| 1108 | LGIV_Rep2R | GGGGGAAGCAGGTAATATAGAAGG | |

| 1115 | LGIV_Rep4F | TACCGCCGTCCTAAAGGGAAGAGG | |

| 1116 | LGIV_Rep4R | CGTAATTGTATTTATCGAACTTAT | |

| 1117 | LGIV_Rep5F | TAGTATAATAGAAGTTCGATAGAG | |

| 1118 | LGIV_Rep5R | AAAGACGGAAGGGGTTATACTATT | |

| 1119 | LGIV_Rep6F | AATTAGAGAATAGATTTACTAGCC | |

| 1120 | LGIV_Rep6R | CGGACGAACTGGGTTTAATTATTC | |

| 1121 | LGIV_Rep7F | ATAGAGGCGAAATCTAATATATTG | |

| 1122 | LGIV_Rep7R | TTTCTACTTACGGTCGATTGACGG | |

| 1123 | LGIV_Rep8F | TATTTATTTTAACGGCCAGTAAGC | |

| 1124 | LGIV_Rep8R | ATTAATTATGAGCTATTTAGACCC | |

| 1125 | LGIV_Rep9F | GTACCATATTTTCTAAAAGGCAAT | |

| 1126 | LGIV_Rep9R | CTTTAATTAGGCGGACAGGCCGAT | |

| 1127 | LGIV_Rep10F | TGCGACTTTCTTATTTTGTAGGGG | |

| 1128 | LGIV_Rep10R | AGGACTATAAAGTATATTACTAGG | |

| 1085 | TEL_ILF | CTTCTTGCGTCTTGCCTGCTC | |

| 1086 | TEL_ILR | CCTTTTCGTTCGGTTGACAGC | |

| 1087 | TEL_VILF | AACTTGGCACCCTCCGCGTT | |

| 1088 | TEL_VILR | CCCCTCTAAGTTTTCCGATT | |

| 913 | Fsr126F | TAATGAAAGACAACCTCGGAGTCC | |

| 938 | Fsr126R | GCACGTAAACCTGCATATGAAGTG | |

| 915 | Fsr92F | TTCGCAATGGTGTCCGGCTCTCGG | |

| 920 | Fsr92R | GTGTGGAAACCATGCGGCTCAACC |

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were carried out on conidia germinated for 6 to 7 h in Vogel's minimal medium with required supplements as described previously (90). Strains and antibodies used for ChIP are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

ChIP-seq design and results

| Sample | Strain | Genotype | Antibodya | Exptb | No. of reads | No. of mapped reads | % mapped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CenH3 | NMF241 | WTc | Anti-GFP | HTS41 | 22,648,972 | 1,868,888 | 8 |

| NMF166 | WT | Anti-GFP | HTS114d | 5,765,823 | 5,115,507 | 89 | |

| NMF233 | WT | Anti-GFP | HTS115d | 3,396,810 | 2,991,616 | 88 | |

| Total | 31,811,605 | 9,976,011 | 31 | ||||

| NMF239 | dim-5 | Anti-GFP | HTS61 | 941,134 | 831,702 | 88 | |

| NMF239 | dim-5 | Anti-GFP | HTS76 | 1,945,259 | 1,361,074 | 70 | |

| Total | 2,886,393 | 2,192,776 | 76 | ||||

| NMF232 | hpo | Anti-GFP | HTS42 | 23,465,182 | 2,824,712 | 12 | |

| CEN-C | NMF225 | WT | Anti-GFP | HTS125 | 16,749,444 | 14,853,136 | 89 |

| CEN-T | NMF399 | WT | Anti-GFP | HTS118d | 3,584,558 | 1,842,613 | 51 |

| H3K4me2 | NMF229 | WT | Anti-H3 K4me2 | HTS14 | 6,978,488 | 3,620,059 | 52 |

| H3K4me3 | NMF39 | WT | Anti-H3 K4me3 | HTS62 | 1,265,661 | 1,180,098 | 93 |

| NMF39 | WT | Anti-H3 K4me3 | HTS77 | 11,944,378 | 10,021,030 | 84 | |

| Total | 13,209,739 | 11,201,128 | 85 | ||||

| H3K9me3 | NMF39 | WT | Anti-H3 K9me3 | HTS111 | 14,638,703 | 12,672,192 | 87 |

| NMF166 | WT | Anti-H3 K9me3 | HTS120d | 4,818,433 | 4,229,931 | 88 | |

| MeDIP | NMF39 | WT | Anti-5meC | HTS18 | 4,588,332 | 1,713,181 | 37 |

Antibodies used: anti-GFP, Abcam ab290; anti-H3K4me2, Upstate 07-030; anti-H3K4me3, Active Motif AR-0169; anti-H3 K9me3, Active Motif 39161; anti-5me-C, Diagenode MAb-5MECYT-100.

Experiment names were used to submit data to the FFGED (see Materials and Methods).

WT, wild type.

Adapter sequence indicated for samples that were multiplexed: HTS114, ACGT; HTS115, CTGT; HTS118, CCCT; HTS120, GCTT.

MeDIP.

Genomic DNA purification, immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA (MeDIP), and MeDIP followed by high-throughput sequencing (MeDIP-seq) were as described previously (71). Two independent MeDIP experiments with wild-type NMF39 were pooled before library construction.

Library construction and high-throughput sequencing.

DNA obtained by ChIP was end repaired and ligated to adapters (71). Fragments (∼200 to 500 bp long) were gel purified and amplified by 18 to 21 cycles of PCR with Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes Oy, NEB) and Illumina PCR primers. PCR products were gel purified and sequenced on an Illumina 1G or GAIIx sequencer in the OSU CGRB core labs (all single end, 36 or 40 cycles). Raw sequence data and associated metadata have been deposited in the Filamentous Fungal Gene Expression Database (FFGED) at Yale University (http://bioinfo.townsend.yale.edu/) and can be identified by the HTS (high-throughput sequencing) experiment number (Table 3). Data are also available directly from the authors upon request.

Data analysis and visualization.

Illumina reads were mapped with the CASHX_2.0 software program (25), available for download at http://jcclab.science.oregonstate.edu/, to assembly 10 of the N. crassa genome (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/neurospora/MultiHome.html), including mitochondrial DNA. The “histogram_density_plots.pl” script (part of the CASHX package) was used to count reads in 1,000-nt windows with a 200-nt scroll and create whole-genome histograms with the following data filters: -h 1000 (excludes reads that match 1,000 or more places in the genome); -P N (pools reads from both positive and negative DNA strands and plots the total reads); -N Y (normalizes nonunique reads by dividing the read count by the number of matches to the genome). The -p option was calculated for each condition as 1,000,000 divided by the number of mapped reads in order to normalize experiments for sequencing depth. This was calculated with mapped reads instead of total reads, because some data sets contained a large percentage of unusable reads (Table 3). GC percent plots were generated with the script “GC_percent_plots.pl” (part of the CASHX package) in 1,000-nt windows with a 200-nt scroll. To identify windows with significant enrichment above average coverage (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material), we used a custom script, “peak_finder.pl.” Output from this analysis was used to determine centromere boundaries (outermost windows with significant enrichment) and calculate centromere sizes (see Fig. 8).

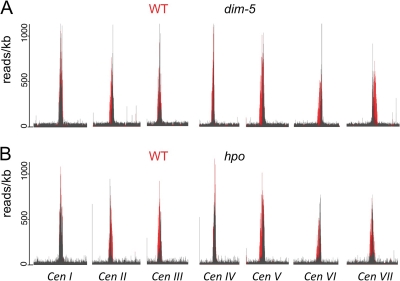

Fig. 8.

Occupancy of CenH3 is confined to smaller regions on most centromeres in heterochromatin mutants. Centromere boundaries were determined as the outermost 1-kb windows with enrichment significantly above background levels at a cutoff of P ≤ 0.0001. Centromere sizes are plotted here as a bar graph, and approximate sizes of centromeric regions for WT (NMF166), dim-5 (NMF239), and hpo (NMF232) strains are noted on the right. In some cases (e.g., Cen I and Cen III in dim-5 strains), single windows with significant CenH3-GFP enrichment were found separated by several kilobases from the “main” centromeric DNA.

Additional analyses were performed to show higher-resolution mapping of reads. We ran the MAQ (0.7.1) software program (55) with default settings and formatted the MAQ output with the Samtools program (0.1.7.0) (54) to generate bam files to view in two genome browsers, IGV (available for download at http://www.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/; see Fig. S5B to E in the supplemental material) or GenomeView (available for download at http://genomeview.org/; see Fig. S8). Repeats (36-mers) were counted by a custom perl script, “count_kmer_repeats.pl.” The script puts each 36-mer into a hash and counts every subsequent time a particular 36-mer is found (shown in Fig. S2). Other images (e.g., see Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 and S2) were generated with the argo genome browser (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/argo/).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of genes and relics of transposable elements (TE) on Neurospora LG VI. Plotting GC content (%GC) reveals an ∼249-kb AT-rich region with enrichment for TE relics. Centromeric repeat regions are not composed of unique DNA segments, since LINE-like segments (mostly dTad), retrotransposons (including copia-like segments, such as Tcen, and gypsy-like segments, such as Tgl1), the mariner-like DNA transposons dPunt and NcAnt1, and regions lacking obvious homology to any known TE are not confined to specific regions of the LG. All can be found at subtelomeric regions, dispersed AT-rich regions on each chromosome arm, and centromeric DNA. The same type of TE distribution is found on the other six chromosomes. For a more detailed view of centromeres IV and VI (Cen IV and Cen VI), see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, and for the distribution of 36-mers, see Fig. S2. The scale is in megabase pairs (Mb).

Region-specific ChIP-PCR.

Duplex PCRs with [α32P]dCTP were carried out to quantify enrichment in the ChIP samples relative to input DNA with region-specific oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) (42, 83), as described previously (71, 90). A euchromatic hH4-1 segment was used as a control. Phosphorimager screens were exposed to dried gels and analyzed with a GE Storm 820 imager. Bands were quantified using the ImageQuantTL software program. Enrichment was calculated as the ratio of the repeat to the hH4-1 control, relative to this ratio in the input DNA sample (input data not shown in Fig. 6 but similar to “control” in Fig. 5). Each PCR was performed at least two times with template from independent ChIP experiments.

Fig. 6.

CenH3 mislocalization in heterochromatin mutants. (A) ChIP-PCRs of centromere repeats compared to the hH4-1 euchromatic control show that distribution of CenH3-GFP is changed in both the dim-5 (NMF238) and hpo (NMF232) mutants, especially at repeats in the centromere periphery. ChIPs were repeated at least two times, and PCRs were performed at least two times with DNA from each replicate ChIP. Results from one representative experiment are shown. (B) Enrichment of CenH3 at centromere repeats relative to hH4-1 was calculated and plotted for the wild-type (WT), dim-5, and hpo strains. Variability in the amount of background (hH4-1 amplification) made quantification of enrichment difficult in some experiments.

Fig. 5.

ChIP-PCR confirms ChIP-seq results. (A) Cartoon showing approximate positions of ChIP-PCR primers along LG VII (∼4.2 Mb) and the first ∼2.5 Mb of LG IV. (B) Duplex ChIP-PCRs show CenH3-GFP localization at centromeric DNA compared to the hH4-1 euchromatic control. No enrichment of H3K4me2 was found in these regions, but CenH3 enrichment was similar to that of H3K9me3. DNA methylation was found at dispersed heterochromatin and the centromere periphery. (C) Neither the silencing marks, H3K27me3 and H4K20me3, nor the activating mark H3K9K14ac is enriched at centromeres. For panels B and C, abbreviations indicate H2A (HA), H2B (HB), Tel IL (T1), and Tel 6L (T6).

Linear growth assays in race tubes.

Freshly grown conidia were inoculated on solid supplemented Vogel's minimal medium in race tubes (21). Hyphal growth at 25C was measured at the times indicated (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

The dim-5 mutant and to a lesser extent the hpo mutant have defects that cause slow-growth phenotypes. (A) Linear growth of WT (NMF39) and CenH3-GFP-tagged strains (A, NMF168; B, NMF169). (B) Linear growth of dim-5 (N2264) and dim-5 CenH3-GFP strains (A and B, NMF238; C, NMF239; D and E, NMF240). (C) Linear growth of hpo (N2552) and hpo CenH3-GFP (NMF232) strains in race tubes at 25C. WT and CenH3-GFP-tagged strains have similar growth rates. The hpo mutants generally have lower growth rates. We recovered only a few hpo CenH3-GFP strains, which grow better than the original hpo mutants. The dim-5 mutation causes decreased but variable growth rates, which can be exacerbated by the presence of the CenH3-GFP allele.

RESULTS

Computational analyses of predicted centromeric DNA regions.

We generated plots of GC content for all seven LGs. On each LG, we found an AT-rich region of >180 kb enriched for relics of TEs. Here we show LG VI as one example (Fig. 1). The plot reveals two chromosome arms with more than 1,000 known or predicted genes, interrupted by an ∼249-kb AT-rich region and several segments of dispersed AT-rich DNA, all of which are enriched in TE relics. The presumably centromeric repeat-rich regions are not composed of a unique class of repeat elements. Low-stringency blastx searches revealed LINE-like segments (mostly dTad), relics of retrotransposons (copia-like segments, such as Tcen, and gypsy-like segments, such as Tgl1), relics of the mariner-like DNA transposons dPunt and NcAnt1, and AT-rich regions lacking obvious homology to any known TE at the presumed centromere, the subtelomeric regions, and dispersed AT-rich regions on each chromosome arm. The same type of TE distribution is found on the other six chromosomes (data not shown).

A more-detailed view of Cen IV and Cen VI summarizes the state of Neurospora genome assembly at the predicted centromeres (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Cen IV is predicted to be on a single contig of ∼174 kb, while Cen VI is currently placed on five large and six short contigs, altogether ∼249 kb. As mentioned above, most duplicated TEs have undergone RIP and are barely recognizable as retrotransposons, DNA transposons, or LINEs after blastx searches, and there are some stretches of AT-rich DNA without homology to any known TEs. There are also a few poor matches to hypothetical genes (Table 4) in other organisms (e.g., the fungus Chaetomium globosum); these homologues appear mutated by RIP, and the ancestral function is unknown.

Table 4.

Regions with centromeric DNA on the seven Neurospora chromosomes

| LG | Cen posa (kb) | Cen size, kb (%)b | Positions of pericentric regionsc (kb) | No. of ctd | First gene left arm | First gene right arm | Predicted gene in centromeree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 3736–3969 | 233.4 (2.4) | 3735–3736 | 4 | 3732488–3734801 | 3972683–3974681 | 3819644–3819946 |

| 3969–3980 | (NCU08579) | (NCU09892) | (NCU08585) | ||||

| II | 1105–1346 | 240.8 (5.4) | 1090–1105 | 6 | 1091322–1092875 | 1366146–1367085 | 1152277–1154521 |

| 1346–1366 | (NCU03328) | (NCU05338) | (NCU11930) | ||||

| III | 705–951 | 246.0 (4.7) | 680–705 | 4 | 681888–682855 | 965755–967346 | 813119–139778 |

| 951–970 | (NCU10596) | (NCU07815) | (NCU05742) | ||||

| IV | 894–1068 | 174.0 (2.9) | 870–894 | 1 | 872242–874450 | 1088600–1089972 | 994038–994787 |

| 1068–1090 | (NCU04963) | (NCU04983) | (NCU04974) | ||||

| V | 932–1209 | 276.8 (4.3) | 890–932 | 5 | 897183–897949 | 1219940–1221421 | None |

| 1209–1230 | (NCU09667) | (NCU11600) | |||||

| VI | 2811–3060 | 249.0 (5.9) | 2770–2811 | 11 | 2766824–2769514 | 3080312–3087794 | None |

| 3060–3080 | (NCU03846) | (NCU12161) | |||||

| VII | 1801–2089 | 287.4 (6.8) | 1770–1801 | 1 | 1770246–1772345 | 2120198–2122450 | None |

| 2090–2120 | (NCU02438) | (NCU11384) |

Position of centromeric (Cen) region on linkage group (LG) in kb.

Size of centromeric (Cen) region in kb and percentage of chromosome that is centromeric DNA, which is large compared to that for S. pombe (0.6 to 4.5%).

Positions of pericentric regions, defined as high in 5-methylcytosine and H3K9me3 enrichment but having little CenH3 enrichment, typically ∼19 to 35 kb of AT-rich DNA on either side of each centromere.

Number of contigs (ct) in the centromeric regions.

The gene within Cen II (NCU11899) is on a short ∼2-kb segment and likely misassembled with respect to the neighboring contigs. All other hypothetical or predicted genes annotated within the centromeres of LG I, III, and IV have no known transcripts, are not associated with H3K4me2 or H3K4me3, and are enriched for CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T and likely pseudogenes.

To detect stretches of identical or near-identical repeats, we plotted the distribution of 36-mer repeats throughout the genome. For the copy number of each 36-mer plotted along each centromere, see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. While some regions with high copy numbers are present, these short regions are dispersed across the whole genome and are not arranged as tandem centromeric arrays. Much of each centromere is composed of unique sequence (i.e., 36-mer repeat count of one). Breaks between contigs are separated by stretches of 100 Ns, accounting for a high 36-mer count at such regions (see Fig. S2). Our results suggest that there are no long segments of satellite-type repeats present in the predicted Neurospora centromeric DNA. A detailed analysis of centromeric DNA from the reference strain, Oak Ridge 74A, and other Neurospora wild-collected and lab strains is the subject of a separate study (K. R. Pomraning, K. M. Smith, and M. Freitag, unpublished data). Neurospora has extended AT-rich pericentric and centromeric regions, ranging from 3 to 7% of the length of individual chromosomes (Table 4).

Strain construction for ChIP.

We generated C-terminal GFP fusion alleles of CenH3 (NCU00145; accession number XP_956658.1), CEN-C (NCU09609; accession number CAB91393.1), and CEN-T (NCU02161; accession number XP_964520) at their endogenous loci under the control of their respective native promoters. The Neurospora CenH3 gene has been designated hH3v (37), but to maintain accepted nomenclature in the field we call the protein CenH3. Heterokaryotic CenH3 and CEN-C transformants were crossed with CenH3 wild-type strains to isolate homokaryotic replacement strains. The Sad-2 mutation suppresses meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA (82) and was used to efficiently pass the CenH3-GFP tag through a cross with a CenH3 wild-type allele in the other parent. The CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T genotypes were verified by Southern blotting and DNA sequencing, and correct expression of epitope-tagged proteins was confirmed both by Western blotting and cytologically (Phatale et al., unpublished). Tagging CenH3, CEN-C, or CEN-T with C-terminal GFP resulted in no obvious growth and developmental phenotypes when the tagged alleles were present in wild-type strains.

ChIP-seq of centromere proteins.

The centromere-specific histone variant, CenH3, a CenH3-interacting protein, CEN-C, and an inner kinetochore protein, CEN-T, were subjected to ChIP. DNA associated with these proteins was sequenced and mapped to assembly 10 of the Neurospora genome. We counted the number of perfect matches to the genome and normalized read counts for both nonuniqueness and sequencing depth (see Materials and Methods). Sequence reads from all three ChIP libraries were enriched in a 150- to 300-kb AT-rich region on each of the seven Neurospora chromosomes (Fig. 2 and 3A; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), corresponding to regions where centromeres had been mapped genetically (68). We tabulated LG coordinates and how much of each chromosome is centromeric DNA, including the most proximal annotated genes and the few hypothetical genes annotated within the centromeres (Table 4). Enrichment of CenH3 (Fig. 2, red) was greater than that of CEN-C (Fig. 2, black) after accounting for sequencing depth, and the region of enrichment extended further for CenH3 than for CEN-C. Greater detail of protein enrichment is shown for Cen II and Cen IV (Fig. 3A) and for all centromeric DNA in the supplemental materials (see Fig. S3). CEN-T enrichment was also confined to a more narrow range than CenH3 but followed CenH3 distribution more closely than CEN-C (Fig. 3A; see also Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

CenH3 and CEN-C colocalize at predicted Neurospora centromeres. Normalized ChIP-seq read counts in 1,000-bp windows (200-bp scroll) along Neurospora's seven linkage groups for CenH3-GFP (NMF166, red) and CEN-C-GFP (NMF225, black). GC content (%GC, top of each panel) was calculated in the same windows. The peak in reads per kilobase pair (reads/kb) for both CenH3 and CEN-C correlates with the large region of AT-rich DNA on each chromosome (scale in megabase pairs [Mb]).

Fig. 3.

Expanded view of ChIP-seq read counts at Cen II (left) and Cen IV (right). (A) Compared to CenH3 (NMF166), CEN-C (NMF225), and CEN-T (NMF399), enrichments do not extend to the periphery of the centromeric DNA. (B and C) Three CenH3-GFP strains generate similar ChIP-seq results (whole centromere [B] or selected 20-kb region [C]). Scales and abbreviations are as shown in Fig. 2.

To determine if centromere positioning following numerous mitotic and meiotic cell divisions was reproducible and constant, we sequenced CenH3-bound DNA from three different CenH3-GFP strains (Fig. 3B and C; see all centromeres in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Strain NMF166 (also shown in Fig. 2, 3, 4, and 7) was generated by crossing the CenH3-GFP+ transformant to a Sad-2 strain, strain NMF241 was generated by crossing NMF166 to a dim-5 mutant, and strain NMF233 was generated by crossing the primary CenH3-GFP transformant to an hpo strain. CenH3-GFP localization was almost superimposable in these three strains from different lineages and when analyzed in separate experiments, strongly suggesting that while there may be minor differences in average centromeric nucleosome positioning, overall the centromeric regions appear reproducibly static. For most analyses we plotted reads/kilobase (e.g., 1-kb windows with a step of 200 nt), a high resolution that still made whole-genome data manipulation more manageable. A higher-resolution view (coverage/nucleotide [see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material]) in centromeric and noncentromeric heterochromatin and euchromatin reveals similar peaks and valleys seen at the resolution of 1-kb windows (Fig. 3B; see also Fig. S4). This “periodicity” becomes more obvious at a finer scale (e.g., in Fig. 3C).

Fig. 4.

Neurospora centromeres are heterochromatic. (A) LG IV is shown as a representative chromosome to compare CenH3-GFP localization (red, NMF166) to modified histones. H3K4me2 (black; NMF229) and H3K4me3 (black; NMF39) are enriched along chromosome arms in genes but absent from the centromere. The heterochromatic mark H3K9me3 (black, NMF166) is found at both dispersed heterochromatin along the chromosome arms and overlapping CenH3 at the centromere. DNA methylation (5meC, black; NMF39) is found at dispersed heterochromatin and the outer edges of the centromere but not the centromere core. (B and C) Expanded view of ChIP-seq read counts for chromatin modifications at Cen II (left) and Cen IV (right) compared to CenH3 enrichment (NMF166). (B) The euchromatic marks, H3K4me2 (NMF229) and H3K4me3 (NMF39) are absent from CenH3-enriched regions. (C) The heterochromatic mark, H3K9me3 (NMF39) is found throughout the CenH3-enriched region and in adjacent pericentric heterochromatin, but DNA methylation (5mC; NMF39) is largely restricted to pericentric heterochromatin (at the centromere edges). Scales and abbreviations are as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 7.

CenH3 localization is changed in heterochromatin mutants. ChIP-seq of CenH3-GFP was performed on dim-5 (NMF239) (A) or hpo (NMF232) (B) mutants and revealed altered patterns of CenH3 enrichment compared to that of the WT (NMF166) and thus CenH3 localization on most chromosomes.

We were surprised to find this reproducible periodicity in CenH3 localization (Fig. 3C; see also fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material) and investigated features of the underlying DNA sequence. To do this, we selected 50 regions each of “peaks” (regions of high CenH3 enrichment) and “valleys” (regions with little CenH3 enrichment) from within Cen VI to analyze for sequence characteristics. By all means employed (e.g., nucleotide content, motifs, near-repeat structure, similarity to nucleosome positioning sequences, and ClustalW analyses) there was no quantifiable difference between the peak and valley sequences (data not shown). Both classes contained features that resemble preferred nucleosome positioning sequences (56, 78), and both classes were enriched for the preferred motifs for de novo DNA methylation in Neurospora, TAAA and TTAA (89). We were unable to construct contigs or consensus sequences from either class that specifically matched to peak or valley sequences of centromeric DNA (by low-stringency blastn searches; data not shown). In conclusion, sequences found in peaks or valleys of one centromeric region were not predictive for peaks or valleys of another centromeric region.

Neurospora centromeres are enriched for H3K9me3-containing nucleosomes.

To address the epigenetic state of Neurospora centromeres, we performed ChIP-seq with antibodies against histone modifications known to be associated with transcriptionally active (H3K4me2 and -me3) or silent (H3K9me3) chromatin (Fig. 4). H3K9me3 is required for binding of the heterochromatin-associated protein HP1, and HP1-GFP fusion proteins localize in typical heterochromatic foci that are absent in the dim-5 mutant, which lacks H3K9 methyltransferase activity (31). We also assayed for cytosine methylation by MeDIP-seq. We present LG IV as an example (Fig. 4A) and a detailed view of Cen II and Cen IV (Fig. 4B and C), but all modification patterns described here were seen on all seven chromosomes (see Fig. S6 and S7 in the supplemental material). As expected, we found both H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 along the chromosome arms in coding regions, but they were absent from the centromeric regions defined by CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T binding (Fig. 4A and B). All reads were normalized based on sequencing depth, which suggests that the increased number of reads obtained for H3K4me3 in comparison to H3K4me2 reflects either greater abundance of that epitope or more efficient ChIP with this particular antibody.

The sharp H3K4me3 peak at 1.15 Mb within Cen II suggests that transcripts are produced from this region. Because CenH3 and CEN-C are not enriched in this region (Fig. 4B; see also Fig. S7 in the supplemental material) and because this is the single such region we found in all seven centromeric regions (see Fig. S7), we suspected that the underlying DNA sequence had been misassembled. In support of this hypothesis, we looked at gene annotations and contig breaks within this region (see Fig. S8). Indeed, the 2,787-bp-long contig 97 enriched in H3K4me3 contains a single gene, NCU11899.5, that is not enriched for CenH3. Unpublished results from the Neurospora Genome Project show transcription from this gene (as determined by “RNA-seq”; F. Yang, K. M. Smith, M. Freitag, and M. S. Sachs, unpublished data). In contrast, the other hypothetical genes annotated within centromeric DNA (NCU08585 on LG I, NCU5742 on LG III, and NCU4974 on LG IV) (Table 4) are not expressed under any condition assayed, have no H3K4me, and all are associated with CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T.

DNA methylation and H3K9me3, which generally colocalize, were enriched at dispersed heterochromatin (Fig. 4A and C), as expected from previous studies (53, 90). H3K9me3 was also found throughout the centromere regions, whereas DNA methylation was mostly restricted to the centromere peripheries and overlapped little with CenH3 localization (Fig. 4A and C; see also Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). We define as Neurospora pericentric regions those peripheral regions with enrichment of H3K9me3 and cytosine DNA methylation but little or no CenH3.

ChIP-seq validation.

Since centromere DNA sequences are AT rich and repetitive, we felt it imperative to validate the ChIP-seq and MeDIP-seq small read mapping results with an alternate method, duplex ChIP-PCR. We designed primers to centromere sequences on LG VII (repeats 3 and 4) and LG IV (repeats 1 through 10, moving from the centromere edge into the core). For negative controls, we designed primers to amplify other types of repetitive DNA: heterochromatic repeats 1, 8, and 9 on LG VII and 5S ribosomal genes (Fsr126 and Fsr92). Other known regions of dispersed heterochromatin (8:G3 and 8:F10) (42) and subtelomeric heterochromatin (Tel1 and Tel 6) (83) were also included. The histone H2A and H2B genes, just outside of the Cen VII region, were used as euchromatic controls (approximate positions of amplicons are shown in Fig. 5A; primer sequences are listed in Table 2). In each PCR, primers to the hH4-1 gene were used as an internal control.

ChIP-PCR was completely consistent with ChIP-seq results (Fig. 5B), i.e., CenH3 was enriched at centromere repeats (LG VII repeats 3 and 4 and LG IV repeats 1 to 10), H3K4me2 was found at euchromatic genes (hH4-1, hH2A, and hH2B) but not centromeres, and H3K9me3 was found at dispersed heterochromatin (LG VII repeats 1, 8, and 9, 8:G3 and 8:F10), subtelomeric heterochromatin (Tel1 and Tel6), and centromere repeats. Similar CEN-C ChIP-PCR assays were also consistent with ChIP-seq (data not shown).

Other epigenetic marks.

While we have not used antibodies to every conceivable histone modification, we used ChIP-PCR to screen for other likely candidate epigenetic marks that may be expected to associate with Neurospora centromeres (Fig. 5C). The two heterochromatic marks H3K27me3 and H4K20me3, both found at Neurospora telomeres (83), and two euchromatic marks, acetylation of H3K9 and H3K14, were not enriched at Neurospora centromeres.

DIM-5 and HP1 are required for normal CenH3 distribution.

We found that H3K9me3 was colocalized with CenH3 (Fig. 4 and 5). To test whether this mark is required for CenH3 localization, we performed CenH3 ChIP in a dim-5 mutant, which lacks nearly all H3K9me3 (88, 90). Enrichment of CenH3 at centromeres in the dim-5 mutant was greatly reduced as determined by duplex ChIP-PCR (Fig. 6). This reduction was greater at the centromere edge (Cen VII repeat 3 and Cen IV repeats 1 to 6) than at more internal repeats (Cen VII repeat 4 and Cen IV repeats 7 to 10).

HP1 binds to H3K9me3 and is required for DNA methylation in Neurospora (31, 42). Based on the results obtained with dim-5 strains, we expected that CenH3 distribution should also be altered in the HP1 mutant hpo strain. Indeed, similar to findings for dim-5 strains, CenH3 enrichment was reduced in the hpo strain and the effect was greatest at the centromere edge (Fig. 6).

We next comprehensively assayed the effects of DIM-5 and HP1 on CenH3 distribution at all seven centromeres by ChIP-seq of CenH3 in both mutants (Fig. 7; also shown, at higher resolution, in Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). We calculated the size of the centromeres based on CenH3 enrichment (reads/kilobase) significantly above the average number of background reads (at P ≤ 0.0001, Z ≥ 3.719015) in wild-type, dim-5, and hpo strains (Fig. 8; see also Fig. S10). In both mutants, Cen I and Cen IV showed overall CenH3 enrichment similar to wild-type levels (Fig. 8). The other five centromeres had significantly reduced regions of CenH3 enrichment in the dim-5 strain (Fig. 7A and 8; see also Fig. S9 and S10). In some cases the size of the CenH3-enriched region in the dim-5 strain may be overestimated by this measure due to some “outliers” (e.g., on the right flank of LG I and III) (see Fig. S10). Frequently the region of CenH3 enrichment shifted to one side (Cen II, IV, V, VI, and VII), which explains why the ChIP-PCR results revealed a decrease in CenH3 enrichment in the left flank of Cen IV (compare Fig. 6 to Fig. S9 and S10 in the supplemental material). Results for the hpo strain were similar, but the overall distribution of CenH3 appeared to be restricted to a smaller region than in the dim-5 strain (Fig. 8; see also Fig. S9 and S10).

Defects in H3K9 methylation result in decreased linear growth.

To begin to address the functional relevance of our observations, we tested growth rates of wild-type, dim-5, and hpo mutant strains as a proxy for centromere function; more typically used genetic or cytological assays are not yet available for Neurospora. We compared strains with and without the CenH3-GFP tag. Strains with CenH3-GFP grew at rates comparable to those of the wild type (Fig. 9A). The dim-5 mutant showed variable but reduced linear growth (Fig. 9B) (31, 88). Addition of the CenH3-GFP tag typically resulted in an additional reduction in the dim-5 strain's growth rate, but the range overlapped that with dim-5 alone. CenH3-GFP hpo progeny were difficult to recover from all crosses carried out, and the strain used here unexpectedly grew almost as well as wild type (Fig. 9C).

DISCUSSION

Neurospora centromeric DNA.

Here we have identified and described centromere core sequences for a filamentous fungus, N. crassa. DNA fragments mapping to the centromere on LG VII were first cloned in 1994 (15). A 16.1-kb segment was sequenced and found to contain degenerate transposons mutated by RIP and three types of simple sequence repeats (11). Initial assemblies of the Neurospora genome revealed long stretches of AT-rich regions, presumably mapping to the centromeric regions on each chromosome (9, 33). Here we used ChIP-seq to determine how much of these AT-rich regions on each Neurospora chromosome serve as the centromere core and contain the centromere-specific H3 variant, CenH3.

Although the Neurospora centromeres are composed of repetitive DNA, the segments are nonidentical “near-repeats” generated by RIP and other mutations. This provides a major advantage for study of Neurospora centromeres not applicable to higher eukaryotes with arrays of identical repeats. The 36-mer sequences generated by Illumina sequencing can be mapped to specific regions of the Neurospora centromeres with high confidence (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material); analyses including only unique reads that map to a single site in the genome (data not shown) generate results similar to those with the normalized total reads shown here (Fig. 2, 3, 4, and 7). We found enrichment of CenH3 across the entire AT-rich region of each predicted centromere (Fig. 2). The sharp peak in the histograms, as opposed to a steady plateau with a marked boundary, implies that average occupancy of CenH3 is greatest at the center of the region and gradually decreases toward the outer edges of the centromere, similar to what has been observed at human neocentromeres (1).

The same sharp peak in chromosome-wide distribution was seen for Neurospora CEN-C (Fig. 2) and CEN-T (Fig. 3A), but both average peak height and width are smaller for CEN-C and CEN-T than for CenH3 (Fig. 2 and 3A), which suggests that CEN-C and CEN-T bind at only a subset of CenH3 sites. It is also possible that the CEN-C and CEN-T ChIPs were less efficient than those for CenH3, perhaps because the epitope tag is less accessible to antibody binding. Incomplete overlap of CEN-C and CenH3 is reminiscent of centromere-kinetochore assemblies in human cells (40), where CEN-C binding may be more dynamic and less stable than that of CenH3. We observed asymmetric CEN-C and CEN-T distribution within the CenH3-defined centromere core regions (best seen in Cen II, Cen VI, and Cen VII; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, kinetochores may not necessarily assemble in the center of the centromere core regions.

We found no conservation of primary DNA sequence at the highest point of the CenH3 enrichment peaks. Analysis of transposon content, AT content, and searches for enriched motifs all provided evidence that peaks and valleys in CenH3 enrichment at different subcentromeric domains possess the same sequence characteristics. How exactly the relatively stable positioning of CenH3-containing nucleosome blocks is achieved and maintained is under investigation. We conclude that RIP-mutated transposon relics serve as centromeric core sequences and that Neurospora lacks alpha-satellite repeats found in plant and human centromeres or indeed any class of centromere-specific repeats. Although undoubtedly small gaps remain in the assembly and small regions of centromere core sequence are still missing (see Fig. S1, S2, and S8 in the supplemental material), most of the centromeric DNA sequences as defined by association with CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T are contained in assembly 10.

Neurospora centromeres lack H3K4 methylation.

Two euchromatic marks, H3K4me2 and H3K4me3, are generally associated with regions undergoing transcription. It was thus surprising when H3K4me2 was found within centromere cores of both Drosophila and humans (49, 85), a region classically thought of as constitutive heterochromatin. This new class of H3K4me2-containing chromatin, also called “centrochromatin,” has since been observed in S. pombe (10). It has been proposed that H3K4me2 is present at the centromere because centromeric repeats are transcribed to generate RNA that serves both structural (23) and silencing roles (10) in humans. Loss of H3K4me2 resulted in a lack of transcription of satellite sequences and a lower efficiency of HJURP-directed targeting of CenH3 to the centromere of an artificial human chromosome (4).

We show here that both H3K4 di- and trimethylation are absent from Neurospora centromeres as defined by occupancy with CenH3, CEN-C, CEN-T, and H3K9me3 (Fig. 4A and B; see also Fig. S6 and S7 in the supplemental material). H3K4 methylation was found along the chromosome arms in coding regions that are actively transcribed. The detailed role of small RNA that is transcribed from Neurospora centromeric DNA has not been explored, although there is evidence of transcription of dispersed heterochromatin (16, 72) and some evidence for the presence of small RNA species produced from the centromeres (51). If RNA is required to establish and maintain centromeres in Neurospora, H3K9me3-enriched heterochromatin is expected not to interfere with the transcription process.

Epigenetic marks at Neurospora centromeres.

In Arabidopsis, fission yeast, flies, and humans, centromeres are surrounded by pericentric heterochromatin, but centromere cores contain the euchromatic H3K4me2 modification. In Neurospora, the H3-containing nucleosomes, interspersed between CenH3-containing nucleosomes, are modified by H3K9me3, not H3K4me2 or H3K4me3. No other marks investigated thus far are enriched at the centromere, e.g., Neurospora centromeres lack silencing marks associated with Neurospora subtelomeric regions, H3K27me3 and H4K20me3 (83). Our finding by both MeDIP-seq (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S6 in the supplemental material) and MeDIP-PCR (Fig. 5B) that DNA methylation appears diminished in or even excluded from the central core region of the centromere compared to the pericentric regions is consistent with findings for Arabidopsis thaliana and Zea mays (96). In human cells, however, CENP-C directly recruits the de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3B, which results in hypermethylation of centromere core sequences (34). The centromeres in rice showed mixed patterns of DNA hypo- or hypermethylation dependent on DNA sequence composition (95). Previous MeDIP experiments in Neurospora that were analyzed by microarray hybridization found DNA methylation across all of Cen VII (53), but this may have been caused by cross-hybridization of repetitive, AT-rich DNA to non-perfectly matched oligonucleotide probes used on the custom arrays. The same study showed enrichment of both H3K9me3 and HP1 at Cen VII (53).

A surprising finding is the apparent colocalization of CenH3 and H3K9me3 within identical regions, rather than several kilobases of alternating blocks of CenH3-containing nucleosomes and H3-containing nucleosomes like those seen in S. pombe, flies, and humans (8, 10, 49, 85). This may reflect differential nucleosome occupancy across a large heterogeneous population of asynchronous nuclei. Smeared microccocal nuclease digestion patterns at centromeric chromatin, indicative of irregular nucleosome spacing, have been observed in S. pombe and C. albicans (3, 70, 87). A more recent study, however, showed regular nucleosome positioning at the S. pombe centromere by ChIP-chip (84). We are currently addressing this question by attempting to synchronize the Neurospora cell cycle to distinguish patterns of CenH3 and H3K9me3 enrichment in synchronized cells.

H3K9 methylation is required for normal CenH3 distribution.

In fission yeast, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated heterochromatin formation directs CenH3 assembly at neocentromeres but is dispensable for inheritance of centromere position (28). The H3K9 methyltransferase, Clr4, and the HP1 homolog, Swi6, are also required for pericentric gene silencing, and Swi6 physically interacts with the CenH3 homolog (27). Swi6 and another chromodomain protein, Chp2, both participate in transcriptional gene silencing at pericentric repeats by their physical interaction with the histone deacetylases (HDACs) Clr3 and Clr6 (27). Both of these HDACs are required to exclude RNA polymerase II from pericentric repeats. Human neocentromeres are also dependent upon formation of adjacent heterochromatin for stability (63). In Neurospora, RNAi appears to be dispensable for heterochromatin formation and DNA methylation (32). Although known RNAi components may not be involved in Neurospora centromere formation, it is clear that heterochromatin, as defined by the presence of H3K9me3, HP1 binding, and formation of discrete HP1-GFP-labeled foci (31, 32), plays a role in chromosome maintenance (31, 32, 52) and CenH3 distribution (Fig. 6 and 7). In the absence of the H3K9 methyltransferase DIM-5 or HP1, the predominant protein binding to H3K9me3, the region of CenH3 distribution shrinks and sometimes shifts. Both dim-5 and hpo mutants have growth phenotypes that remain to be fully characterized. Unincorporated CenH3 is typically subject to protein degradation (6, 24, 29, 36, 48). Why centromeric CenH3 levels appear to be overall diminished in dim-5 and hpo strains will be addressed in future experiments.

Assaying centromere function is difficult in filamentous fungi like Neurospora because many nuclei contribute to the function of the growing hypha. A defect causing aneuploidy in a significant percentage of nuclei generally results in slow growth, because the rare nuclei that are able to undergo mitosis can rescue the growth of the syncytium. A Neurospora DNA methyltransferase mutant, the dim-2 mutant, has no known growth defects (47), and thus, the slow-growth phenotypes and other morphological abnormalities observed in the dim-5 and hpo strains are not likely attributable to their known defects in DNA methylation (31, 88). We hypothesize that the growth defect in the original dim-5 and hpo mutants is due to centromere dysfunction. Recent data suggest that the frequency of atypical “chromatin bridges” increases in dim-5 and hpo strains (52). In our experiments, the dim-5 and dim-5 CenH3-GFP strains grew more slowly than wild-type controls (Fig. 9). We expected a similar or more severe growth defect in the hpo mutant, because the defect in CenH3-GFP localization appeared more severe in the hpo strain than in the dim-5 strain (Fig. 8; see also Fig. S10 in the supplemental material). However, we saw similar growth rates for the hpo CenH3-GFP and wild-type strains compared to that of the parental hpo mutant (Fig. 9C). Even the parental hpo mutant (Fig. 9C), which has been subcultured or backcrossed several times, has recovered from the severe growth defect first described in the original hpo mutants (31), a phenomenon not yet understood. One explanation for the “rescued” growth phenotype in the hpo and hpo CenH3-GFP strains is overexpression of another Neurospora chromodomain protein, which can suppress a lack of HP1. One such candidate is CDP-1, a homologue of S. pombe Chp2. Further work must be done to determine the role of HP1 at the centromere and to determine the precise functional significance of the smaller centromeres in both the dim-5 and hpo mutants. Isolation of hpo CenH3-GFP progeny was difficult, further evidence of a genetic interaction between CenH3 and hpo. Instead of the expected 25% of progeny with both markers, only roughly 1% recombinants were recovered (data not shown).

Pericentric heterochromatin and the centromere core are required for chromatid cohesion (5, 35, 64, 69, 92). A distinction between pericentric heterochromatin and the centromere core, where the kinetochore is built and attaches to spindle microtubules, is proposed to determine either monopolar or bipolar spindle attachment of sister chromatids during meiosis and mitosis, respectively (74, 75). How Neurospora segregates these two functions in the absence of a clear boundary between centromere core and pericentric heterochromatin deserves further study. It is difficult to define pericentric regions in Neurospora because H3K9me3 is found throughout the centromeric-pericentric region. A notable difference at the periphery of Neurospora centromeres is the presence of DNA methylation and overabundance of H3K9me3 compared to CenH3 (Fig. 4C; see also Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Further investigation of the presence of HP1, which recruits the DNA methyltransferase DIM-2 (42), and other chromodomain proteins across the centromere will provide additional insight into the distinction between core and pericentric regions. In mouse, where H3K9me2 is also found in both core and pericentric regions, HP1α is found only at pericentric regions and centromere proteins are found only at the core (35).

Conclusions.

Here we show that Neurospora centromeres consist of ∼150 to 300 kb of AT-rich, RIP-mutated repeats and lack tandem satellite repeats found in many other eukaryotes with regional centromeres. The epigenetic pattern of histone modification in the centromere core, occupied by CenH3, CEN-C, and CEN-T, is heterochromatic, not centrochromatic, containing H3K9me3 instead of H3K4me2 or H3K4me3. At the same time, the heterochromatin at the centromere is distinct from subtelomeric heterochromatin, which is also enriched for H3K27me3 and H4K20me3, and it is distinct from dispersed heterochromatin, which is typically marked by extensive DNA methylation. The pattern of CenH3 and H3K9me3 enrichment at centromeric DNA implies some fluidity between the position of CenH3-containing nucleosomes and H3K9me3-containing nucleosomes. Moreover, we found that centromeric heterochromatin is necessary for normal distribution of CenH3. Future studies will uncover if heterochromatin is essential for centromere maintenance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lanelle Connolly for technical support, Mark Dasenko, Steve Drake, Matthew Peterson, and Scott Givan at the OSU CGRB core facility for assistance with Illumina sequencing, and Noah Fahlgren and Henry Priest for helpful discussions and for sharing code. Shinji Honda and Eric Selker kindly provided pZero plasmids, as well as hpo and dim-5 mutant strains. Yi Zhou and Jason Stajich gave us access to RepeatMasker files. We are grateful to James C. Carrington for his support and encouragement of this work.

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (RSG-08-030-01-CCG to M.F.), start-up funds from the OSU Computational and Genome Biology Initiative, and funds supporting the OSU CGRB.

We have no conflicting interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 19 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alonso A., et al. 2007. Co-localization of CENP-C and CENP-H to discontinuous domains of CENP-A chromatin at human neocentromeres. Genome Biol. 8: R148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barratt R. W., Newmeyer D., Perkins D. D., Garnjobst L. 1954. Map construction in Neurospora crassa. Adv. Genet. 6: 1–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baum M., Sanyal K., Mishra P. K., Thaler N., Carbon J. 2006. Formation of functional centromeric chromatin is specified epigenetically in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 14877–14882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergmann J. H., et al. 2011. Epigenetic engineering shows H3K4me2 is required for HJURP targeting and CENP-A assembly on a synthetic human kinetochore. EMBO J. 30: 328–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernard P., et al. 2001. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science 294: 2539–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Black B. E., et al. 2007. Centromere identity maintained by nucleosomes assembled with histone H3 containing the CENP-A targeting domain. Mol. Cell 25: 309–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blower M. D., Karpen G. H. 2001. The role of Drosophila CID in kinetochore formation, cell-cycle progression and heterochromatin interactions. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 730–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blower M. D., Sullivan B. A., Karpen G. H. 2002. Conserved organization of centromeric chromatin in flies and humans. Dev. Cell 2: 319–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borkovich K. A., et al. 2004. Lessons from the genome sequence of Neurospora crassa: tracing the path from genomic blueprint to multicellular organism. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68: 1–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cam H. P., et al. 2005. Comprehensive analysis of heterochromatin- and RNAi-mediated epigenetic control of the fission yeast genome. Nat. Genet. 37: 809–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cambareri E. B., Aisner R., Carbon J. 1998. Structure of the chromosome VII centromere region in Neurospora crassa: degenerate transposons and simple repeats. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 5465–5477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cambareri E. B., Helber J., Kinsey J. A. 1994. Tad1-1, an active LINE-like element of Neurospora crassa. Mol. Gen. Genet. 242: 658–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cambareri E. B., Singer M. J., Selker E. U. 1991. Recurrence of repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 127: 699–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carroll C. W., Milks K. J., Straight A. F. 2010. Dual recognition of CENP-A nucleosomes is required for centromere assembly. J. Cell Biol. 189: 1143–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centola M., Carbon J. 1994. Cloning and characterization of centromeric DNA from Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 1510–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chicas A., Cogoni C., Macino G. 2004. RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent mechanisms contribute to the silencing of RIPed sequences in Neurospora crassa. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 4237–4243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cleveland D. W., Mao Y., Sullivan K. F. 2003. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112: 407–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coleman J. J., et al. 2009. The genome of Nectria haematococca: contribution of supernumerary chromosomes to gene expansion. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colot H. V., et al. 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 10352–10357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuomo C. A., et al. 2007. The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals a link between localized polymorphism and pathogen specialization. Science 317: 1400–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davis R. H. 2000. Neurospora: contributions of a model organism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dawe R. K., Henikoff S. 2006. Centromeres put epigenetics in the driver's seat. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31: 662–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Du Y., Topp C. N., Dawe R. K. 2010. DNA binding of centromere protein C (CENPC) is stabilized by single-stranded RNA. PLoS Genet. 6: e1000835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dunleavy E. M., et al. 2009. HJURP is a cell-cycle-dependent maintenance and deposition factor of CENP-A at centromeres. Cell 137: 485–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fahlgren N., et al. 2009. Computational and analytical framework for small RNA profiling by high-throughput sequencing. RNA 15: 992–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fedorova N. D., et al. 2008. Genomic islands in the pathogenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fischer T., et al. 2009. Diverse roles of HP1 proteins in heterochromatin assembly and functions in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 8998–9003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Folco H. D., Pidoux A. L., Urano T., Allshire R. C. 2008. Heterochromatin and RNAi are required to establish CENP-A chromatin at centromeres. Science 319: 94–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foltz D. R., et al. 2009. Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-A nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell 137: 472–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Foltz D. R., et al. 2006. The human CENP-A centromeric nucleosome-associated complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 8: 458–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freitag M., Hickey P. C., Khlafallah T. K., Read N. D., Selker E. U. 2004. HP1 is essential for DNA methylation in Neurospora. Mol. Cell 13: 427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Freitag M., et al. 2004. DNA methylation is independent of RNA interference in Neurospora. Science 304: 1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Galagan J. E., et al. 2003. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 422: 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gopalakrishnan S., Sullivan B. A., Trazzi S., Della Valle G., Robertson K. D. 2009. DNMT3B interacts with constitutive centromere protein CENP-C to modulate DNA methylation and the histone code at centromeric regions. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18: 3178–3193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guenatri M., Bailly D., Maison C., Almouzni G. 2004. Mouse centric and pericentric satellite repeats form distinct functional heterochromatin. J. Cell Biol. 166: 493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayashi T., et al. 2004. Mis16 and Mis18 are required for CENP-A loading and histone deacetylation at centromeres. Cell 118: 715–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hays S. M., Swanson J., Selker E. U. 2002. Identification and characterization of the genes encoding the core histones and histone variants of Neurospora crassa. Genetics 160: 961–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hegemann J. H., Fleig U. N. 1993. The centromere of budding yeast. Bioessays 15: 451–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hellwig D., et al. 2008. Live-cell imaging reveals sustained centromere binding of CENP-T via CENP-A and CENP-B. J. Biophotonics 1: 245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hemmerich P., et al. 2008. Dynamics of inner kinetochore assembly and maintenance in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 180: 1101–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henikoff S., Ahmad K., Malik H. S. 2001. The centromere paradox: stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science 293: 1098–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Honda S., Selker E. U. 2008. Direct interaction between DNA methyltransferase DIM-2 and HP1 is required for DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 6044–6055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Honda S., Selker E. U. 2009. Tools for fungal proteomics: multifunctional Neurospora vectors for gene replacement, protein expression and protein purification. Genetics 182: 11–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hori T., et al. 2008. CCAN makes multiple contacts with centromeric DNA to provide distinct pathways to the outer kinetochore. Cell 135: 1039–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Johnson D. S., Mortazavi A., Myers R. M., Wold B. 2007. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science 316: 1497–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kagansky A., et al. 2009. Synthetic heterochromatin bypasses RNAi and centromeric repeats to establish functional centromeres. Science 324: 1716–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kouzminova E. A., Selker E. U. 2001. Dim-2 encodes a DNA-methyltransferase responsible for all known cytosine methylation in Neurospora. EMBO J. 20: 4309–4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lagana A., et al. 2010. A small GTPase molecular switch regulates epigenetic centromere maintenance by stabilizing newly incorporated CENP-A. Nat. Cell Biol. 12: 1186–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lam A. L., Boivin C. D., Bonney C. F., Rudd M. K., Sullivan B. A. 2006. Human centromeric chromatin is a dynamic chromosomal domain that can spread over noncentromeric DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 4186–4191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lamb J. C., Yu W., Han F., Birchler J. A. 2007. Plant chromosomes from end to end: telomeres, heterochromatin and centromeres. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10: 116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee H. C., et al. 2010. Diverse pathways generate microRNA-like RNAs and Dicer-independent small interfering RNAs in fungi. Mol. Cell 38: 803–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lewis Z. A., et al. 2010. DNA methylation and normal chromosome behavior in Neurospora depend on five components of a histone methyltransferase complex, DCDC. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lewis Z. A., et al. 2009. Relics of repeat-induced point mutation direct heterochromatin formation in Neurospora crassa. Genome Res. 19: 427–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li H., et al. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li H., Ruan J., Durbin R. 2008. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 18: 1851–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lowary P. T., Widom J. 1998. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 276: 19–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Malik H. S., Bayes J. J. 2006. Genetic conflicts during meiosis and the evolutionary origins of centromere complexity. Biochem. Soc Trans. 34: 569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Malik H. S., Henikoff S. 2002. Conflict begets complexity: the evolution of centromeres. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mavrich T. N., et al. 2008. A barrier nucleosome model for statistical positioning of nucleosomes throughout the yeast genome. Genome Res. 18: 1073–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mavrich T. N., et al. 2008. Nucleosome organization in the Drosophila genome. Nature 453: 358–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mikkelsen T. S., et al. 2007. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature 448: 553–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mizuno H., et al. 2006. Identification and mapping of expressed genes, simple sequence repeats and transposable elements in centromeric regions of rice chromosomes. DNA Res. 13: 267–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nakashima H., et al. 2005. Assembly of additional heterochromatin distinct from centromere-kinetochore chromatin is required for de novo formation of human artificial chromosome. J. Cell Sci. 118: 5885–5898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nonaka N., et al. 2002. Recruitment of cohesin to heterochromatic regions by Swi6/HP1 in fission yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 4: 89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Padmanabhan S., Thakur J., Siddharthan R., Sanyal K. 2008. Rapid evolution of Cse4p-rich centromeric DNA sequences in closely related pathogenic yeasts, Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105: 19797–19802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Perkins D. D. 1953. The detection of linkage in tetrad analysis. Genetics 38: 187–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Perkins D. D., Radford A., Newmeyer D., Björkman M. 1982. Chromosomal loci of Neurospora crassa. Microbiol. Rev. 46: 426–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Perkins D. D., Radford A., Sachs M. S. 2001. The Neurospora Compendium. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 69. Peters A. H., et al. 2001. Loss of the Suv39h histone methyltransferases impairs mammalian heterochromatin and genome stability. Cell 107: 323–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Polizzi C., Clarke L. 1991. The chromatin structure of centromeres from fission yeast: differentiation of the central core that correlates with function. J. Cell Biol. 112: 191–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pomraning K. R., Smith K. M., Freitag M. 2009. Genome-wide high throughput analysis of DNA methylation in eukaryotes. Methods 47: 142–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rountree M. R., Selker E. U. 1997. DNA methylation inhibits elongation but not initiation of transcription in Neurospora crassa. Genes Dev. 11: 2383–2395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rudd M. K., Schueler M. G., Willard H. F. 2003. Sequence organization and functional annotation of human centromeres. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant Biol. 68: 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sakuno T., Tada K., Watanabe Y. 2009. Kinetochore geometry defined by cohesion within the centromere. Nature 458: 852–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sakuno T., Watanabe Y. 2009. Studies of meiosis disclose distinct roles of cohesion in the core centromere and pericentromeric regions. Chromosome Res. 17: 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sanyal K., Baum M., Carbon J. 2004. Centromeric DNA sequences in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans are all different and unique. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101: 11374–11379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schueler M. G., Higgins A. W., Rudd M. K., Gustashaw K., Willard H. F. 2001. Genomic and genetic definition of a functional human centromere. Science 294: 109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Segal E., et al. 2006. A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature 442: 772–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Selker E. U. 1990. Premeiotic instability of repeated sequences in Neurospora crassa. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24: 579–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Selker E. U., et al. 2003. The methylated component of the Neurospora crassa genome. Nature 422: 893–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shibata F., Murata M. 2004. Differential localization of the centromere-specific proteins in the major centromeric satellite of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Cell Sci. 117: 2963–2970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shiu P. K., Zickler D., Raju N. B., Ruprich-Robert G., Metzenberg R. L. 2006. SAD-2 is required for meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA and perinuclear localization of SAD-1 RNA-directed RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 2243–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Smith K. M., et al. 2008. The fungus Neurospora crassa displays telomeric silencing mediated by multiple sirtuins and by methylation of histone H3 lysine 9. Epigenetics Chromatin 1: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Song J. S., Liu X., Liu X. S., He X. 2008. A high-resolution map of nucleosome positioning on a fission yeast centromere. Genome Res. 18: 1064–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sullivan B. A., Karpen G. H. 2004. Centromeric chromatin exhibits a histone modification pattern that is distinct from both euchromatin and heterochromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11: 1076–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sun X., Le H. D., Wahlstrom J. M., Karpen G. H. 2003. Sequence analysis of a functional Drosophila centromere. Genome Res. 13: 182–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Takahashi K., et al. 1992. A low copy number central sequence with strict symmetry and unusual chromatin structure in fission yeast centromere. Mol. Biol. Cell 3: 819–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tamaru H., Selker E. U. 2001. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nature 414: 277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tamaru H., Selker E. U. 2003. Synthesis of signals for de novo DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 2379–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tamaru H., et al. 2003. Trimethylated lysine 9 of histone H3 is a mark for DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nat. Genet. 34: 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Tanaka K., Chang H. L., Kagami A., Watanabe Y. 2009. CENP-C functions as a scaffold for effectors with essential kinetochore functions in mitosis and meiosis. Dev. Cell 17: 334–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Valdeolmillos A., et al. 2004. Drosophila cohesins DSA1 and Drad21 persist and colocalize along the centromeric heterochromatin during mitosis. Biol. Cell 96: 457–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]