Abstract

Telomerase is essential for telomere length maintenance. Mutations in either of the two core components of telomerase, telomerase RNA (TR) or the catalytic protein component telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), cause the genetic disorders dyskeratosis congenita, pulmonary fibrosis, and other degenerative diseases. Overexpression of the TERT protein has been reported to have telomere length-independent roles, including regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway. To examine the phenotypes of TERT haploinsufficiency and determine whether loss of function of TERT has effects other than those associated with telomere shortening, we characterized both mTERT+/− and mTERT−/− mice on the CAST/EiJ genetic background. Phenotypic analysis showed a loss of tissue renewal capacity with progressive breeding of heterozygous mice that was indistinguishable from that of mTR-deficient mice. mTERT−/− mice, from heterozygous mTERT+/− mouse crosses, were born at the expected Mendelian ratio (26.5%; n = 1,080 pups), indicating no embryonic lethality of this genotype. We looked for, and failed to find, hallmarks of Wnt deficiency in various adult and embryonic tissues, including those of the lungs, kidneys, brain, and skeleton. Finally, mTERT−/− cells showed wild-type levels of Wnt signaling in vitro. Thus, while TERT overexpression in some settings may activate the Wnt pathway, loss of function in a physiological setting has no apparent effects on Wnt signaling. Our results indicate that both TERT and TR are haploinsufficient and that their deficiency leads to telomere shortening, which limits tissue renewal. Our studies imply that hypomorphic loss-of-function alleles of hTERT and hTR should cause a similar disease spectrum in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Short telomeres play a critical role in human disease. It was first shown that short telomeres underlie the bone marrow failure seen in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita (57, 72). Short telomeres are also associated with a broad spectrum of degenerative disorders that are linked to aging, including aplastic anemia, pulmonary fibrosis, liver disease, and others (1, 4, 5, 11, 41, 70, 78, 79). While these diseases were once thought to be distinct, it is now clear that they share the common molecular defect of progressive telomere shortening (2). Progressive telomere shortening generates critically short telomeres that limit the replicative capacity of cells (30) and, in mice, is known to cause loss of tissue renewal capacity (29, 42) and progressive organ failure (2).

Telomeres cap chromosome ends and distinguish a natural chromosome end from a DNA break. When telomeres become critically short, the protective function is lost, initiating a DNA damage response (18, 20, 36). This damage response signals through p53, leading to either apoptosis or cellular senescence. Thus, maintaining telomere length is essential for cell survival. Telomerase is the enzyme that maintains telomere length. During normal DNA replication, telomeres shorten due to the inability of the replication machinery to fully copy the very ends of chromosomes. The natural shortening is counterbalanced by telomerase, which adds telomeric DNA sequence onto chromosome ends (28). Telomerase has two conserved core subunits: an essential RNA component, TR, and a catalytic protein component, TERT, as well as a number of species-specific accessory factors (8). Telomerase establishes a length equilibrium that is tightly regulated in the cell by telomere binding proteins and regulatory kinases that regulate the action of telomerase at the telomere (67). Mutations in the telomerase components TR and TERT that reduce telomerase activity result in telomere shortening in both humans and mice (4, 9, 45, 72, 79). The autosomal dominant inheritance of dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia, and pulmonary fibrosis in individuals carrying telomerase mutations is due to haploinsufficiency when telomerase components are compromised and short telomeres result (4, 5, 49, 70, 72, 79).

We generated and characterized a telomerase-null mouse to understand the connection between telomere length and telomerase (9). The RNA component, mTR, was deleted in this mouse, and initial studies were done on two different genetic backgrounds, the 129/C57BL/6J mixed genetic background (42) and later the C57BL/6J background (33). Both of these laboratory strains of mice have unusually long heterogeneous telomeres compared to those of humans and wild mice (31). When these mTR−/− mice were successively interbred for six generations, telomeres shortened with each generation (9). On this long-telomere genetic background, no phenotypes were seen for the first three generations. After telomeres were sufficiently short, the late-generation mTR−/− G4 through mTR−/− G6 mice showed a progressive functional decline in tissues with high turnover rates (42). There was a pronounced decrease in testis size due to germ cell apoptosis (32), and significant degenerative effects were also seen in the hematopoietic system, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and skin (26, 34, 35, 42, 64, 76).

To more fully examine phenotypes associated with short telomeres, we generated mTR+/− and mTR−/− mice on the CAST/EiJ genetic background, which has telomere lengths similar to those of humans (31). While the C57BL/6J mTR−/− mice were instrumental in understanding the role of short telomeres in limiting tumor growth (19, 50), the very heterogeneous and unusually long telomeres on this genetic background make phenotypic analysis difficult. In contrast to C57BL/6J mTR−/− mice, CAST/EiJ mTR−/− mice showed significant defects in tissue renewal in the first generation (29). Further, progressive breeding of CAST/EiJ mTR+/− mice showed haploinsufficiency for telomerase similar to that seen in human autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita families. The phenotypes of these mice recapitulate many of the disease phenotypes seen in human dyskeratosis congenita that contribute to the morbidity and mortality of the disease, including bone marrow failure (3, 29). The progressive telomere shortening and decreased survival with each generation in these mice are similar to the genetic anticipation found in dyskeratosis congenita. In these autosomal dominant families, the genetic anticipation describes a worsening of the phenotype and an earlier onset of disease in the later generations (4, 73).

Autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita was first found to be caused by loss-of-function mutations in the hTR gene (72), and other families were later identified that have mutations in hTERT (4). Mutations in either hTR or hTERT also cause autosomal dominant pulmonary fibrosis (5, 70), indicating that mutation in either hTR or hTERT can result in haploinsufficiency and telomere shortening (2). Mouse models of mTR and mTERT deficiency can offer insight into the role of these two components in human disease. The first experiments to look at loss of telomerase function in mammals were done using the mTR null allele, as described above. Subsequently, three different groups generated mTERT−/− mice (15, 45, 81). All of these mice were analyzed on C57BL/6J and 129/C57BL/6J mixed genetic backgrounds with long telomeres. Progressive telomere shortening was seen in the embryonic stem cells grown in culture (44, 45) and in successive generations of mTERT−/− mice (22). Similar to the mTR−/− mice, there was no phenotype seen in the early generations (22, 81), while later generations showed degenerative phenotypes in the testes, intestine, and bone marrow (14, 54) similar to those of mTR−/− mice.

To understand the human diseases associated with telomerase, it is important to know whether mutations in hTR and hTERT would be expected to show similar or different phenotypes. Telomerase mutations in families are typically initially diagnosed as either dyskeratosis congenita or pulmonary fibrosis. However, the clinical manifestations of short telomeres are very heterogeneous. The factors that determine which clinical manifestation may be seen first are not yet clear. Several investigators have suggested that the specific gene that is mutated, hTR or hTERT, or the specific mutation may play a role in determining which disease is seen (12, 23, 74, 77). Another explanation that has been suggested for the difference in the disease spectrum comes from recent literature suggesting that the TERT protein may have functional roles independent of its role in telomere elongation (16, 24, 47, 51, 60). If, indeed, TERT has additional functions that are separate from telomere length maintenance, it would be expected that some mutations in hTERT might be manifested as diseases different than those seen with mutations in hTR.

To fully understand the potential spectrum of diseases that are due to mutations in either hTERT or hTR, we wanted to critically examine the effects of mTERT loss and mTERT haploinsufficiency in mice. To do this, we took advantage of the CAST/EiJ mouse with short, homogeneous telomere length distributions (31). By examining CAST/EiJ mTERT−/− and mTERT+/− mice and comparing them to CAST/EiJ mTR−/− and mTR+/− mice, we can further determine whether any additional phenotypes are seen that may be attributable to alternative functions of TERT. In our analysis, we found that the telomere shortening in mTERT−/− and mTERT+/− mice was very similar to that observed in mTR−/− and mTR+/− mice. We documented haploinsufficiency in progressive generations of mTERT+/− and mTERT−/− mice that led to a loss of tissue renewal capacity. Moreover, we did not find any additional phenotypes, including Wnt pathway defects, in mTERT−/− mice, suggesting that the phenotypic consequence of mTERT loss is caused by telomere shortening, not by telomere-independent functions of mTERT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse breeding.

mTERT CAST/EiJ mice were generated by following the protocol for mTR CAST/EiJ mice (29). Briefly, we backcrossed C57BL/6J mTERT heterozygous mice (45) onto the CAST/EiJ background for six generations. After six backcrosses, heterozygous mice were designated HG1 for heterozygous generation 1. The progeny of HG1 crosses generated KOG2, HG2, and WT2* mice (see Fig. 1A). Subsequent generations were obtained by interbreeding increasingly heterozygous generations. HG1 mice were maintained by crossing them to wild-type (WT) mice to avoid haploinsufficiency causing telomere shortening. All animals were housed and bred in a pathogen-free environment at The Johns Hopkins University. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Johns Hopkins University.

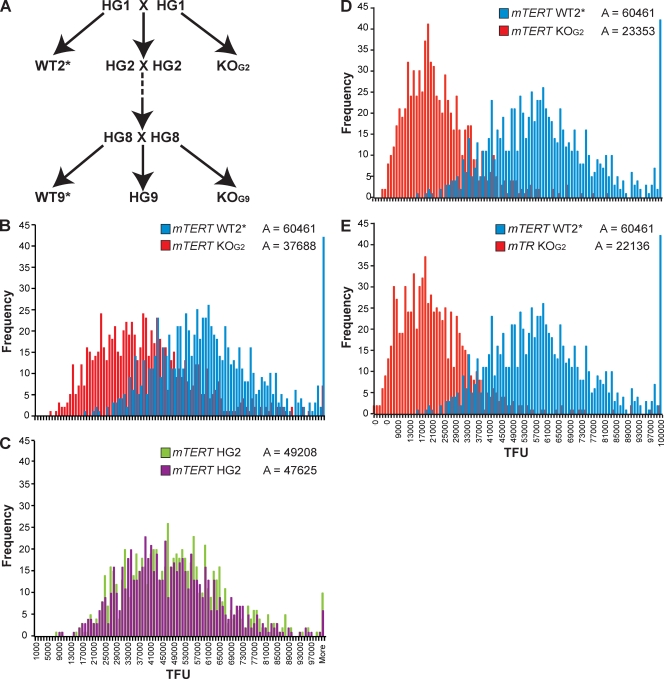

Fig. 1.

mTERT−/− and mTERT+/− mice show telomere shortening and haploinsufficiency. (A) CAST/EiJ mTERT+/− breeding scheme and nomenclature of each generation. (B and C) Q-FISH analysis of littermates from an mTERT+/− HG1 cross. TFU represents arbitrary telomere fluorescence units. mTERT−/− KOG2 (mean = 37,688 TFU) and WT WT2* (mean = 60,461 TFU) (B) and two mTERT+/− HG2 littermates (C) are compared on the same scale (means = 49,208 and 47,625 TFU, respectively). (D) Telomere length distribution in mTERT KOG2 (mean = 23,353 TFU) and (E) mTR KOG2 mice (mean = 22,136 TFU) compared to that in WT mice (mean = 60,461 TFU).

Telomere length analysis.

We measured telomere length by quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) and flow cytometry FISH (Flow-FISH). For Q-FISH, we generated metaphases from splenocytes as described previously (33). Metaphase slides were hybridized with a Cy3-labeled PNA telomere probe (Applied Biosystems) and imaged with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope, and telomere length analysis was performed in a blinded fashion using the TFL-TELO software (63). Flow-FISH was performed on splenocytes by following the protocol of Baerlocher et al. (6). Briefly, we isolated spleens and generated single-cell suspensions using a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). We removed erythrocytes by lysing them in RBC Lysis Buffer (eBioscience). The remaining white blood cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in hybridization mix (70% formamide [Fisher Scientific], 0.5% blocking reagent [Roche], 0.01 M Tris, 0.4 mg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]-labeled PNA probe [Applied Biosystems]) and incubated at 87°C for 15 min and then overnight at room temperature, both times in the dark. Cells were washed twice on the following day (1% bovine serum albumin [BSA; Roche], 0.01 M Tris, 70% formamide, 0.1% Tween 20 [Sigma]) and resuspended in 0.1% BSA. DNA was stained with 7-aminoactinomycin D (4 μg/ml; Invitrogen) and RNase A treated (0.2 mg/ml; Roche) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples were run on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using the FlowJo software. To ensure that the FL-1 channel was within the linear range of detection and sensitivity, we used FITC-labeled calibration beads (Bangs Laboratories) prior to every run.

Pathology.

Mice were euthanized, and organs were fixed in 10% formalin. Where organ architecture needed to be preserved (GI tract, lungs), organs were injected with 10% formalin. Following fixation, organs were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For testis analysis, testes were fixed in Bouin's fixative overnight and similarly processed. Testis slides were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope and analyzed using the NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon). Both pathologic and testis analyses were performed in a blinded fashion. Complete blood counts were done on blood obtained by cardiac puncture of anesthetized mice using heparin-rinsed syringes, placed into EDTA-coated tubes (BD), and sent to the Johns Hopkins medical lab for complete and differential blood counts on the same day. To analyze mouse ribs, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation prior to X-ray analysis and imaged using a Faxitron model MX-20 X-ray machine. To look for subtle Wnt-related phenotypes, embryos from mTERT+/− crosses were dissected at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) to E14.5. The gross morphology, including body axis formation, was examined in a blinded manner after dissection. Samples were taken for genotype analysis, and embryos were then fixed in formalin. The lungs and kidneys were dissected and examined for morphological changes. Embryonic heads were processed for paraffin embedding according to standard methods. Ten-micrometer serial coronal sections of the head were cut. Sections 250 μm apart were stained with H&E. The major structures of the brain, including the forebrain, midbrain, and cerebellum, of WT and mTERT−/− mice were compared in a blinded manner by two independent researchers.

Luciferase assay.

CAST/EiJ mTERT WT2* and KOG2 and C57BL/6J WT and mTERT knockout (KO) G1 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were split into 24-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well and transfected with 200 ng total DNA for 48 h using Fugene-6 (Roche). Transfected DNA contained several plasmids, including 50 ng TOPflash firefly luciferase plasmid, 50 ng Wnt3a plasmid, and 0.8 ng Renilla luciferase pTK-RL as a transfection control, and 99.2 ng of DNA for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). In samples where one or more components were omitted, total DNA was adjusted to 200 ng/well with DNA for EGFP. All plasmids were kindly provided by Jeremy Nathans. After transfection, cells were washed with PBS and luciferase levels were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Luciferase levels were calculated by dividing firefly luciferase by Renilla luciferase levels. Assays were performed at least in triplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance was calculated with the Prism software (GraphPad) using an unpaired Student t test. We considered a P value below 0.05 to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

To examine the phenotypes associated with both complete loss of mTERT and haploinsufficiency, we crossed the mTERT null allele from the C57BL/6J strain (45) onto the CAST/EiJ genetic background by crossing mTERT+/− mice to CAST/EiJ WT mice for six generations. To examine the effects of progressive telomere shortening, we then intercrossed the heterozygous mice for nine generations (Fig. 1 A). We designated each successive heterozygous generation HG1 through HG9 as previously described for mTR+/− mice (29). The mTERT−/− “knockouts” from each generation were designated KOG2 through KOG9, and the WT littermates were designated WT2* through WT9* (3). mTERT+/− mice on the C57BL/6J background were previously shown to have 50% of the mTERT transcript level of WT mice (45). We confirmed a similar decrease in mTERT mRNA in the bone marrow, liver, and MEFs of the CAST/EiJ mouse strain by using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (data not shown).

Telomere shortening in mTERT−/− and mTERT+/− mice is similar to shortening in mTR−/− and mTR+/− mice.

We first examined the telomere lengths in WT, mTERT+/−, and mTERT−/− mice by Q-FISH (63). There was significant telomere shortening in mTERT−/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 1B), and two heterozygous littermates from this cross were intermediate in telomere length (Fig. 1C). This shows that haploinsufficiency for mTERT leads to shorter telomeres in one generation. To compare telomere shortening in mTERT−/− mice to the shortening that occurs in mTR−/− mice, we used Q-FISH on splenocyte metaphases prepared from generation- and age-matched mice. The degree of telomere shortening of mTERT−/− mice (Fig. 1D) was indistinguishable from that of mTR−/− mice (Fig. 1E). This indicates that loss of telomerase activity, whether from loss of mTR or loss of mTERT, leads to a very similar degree of telomere shortening.

To examine individual mice in successive generations of heterozygous breeding, we used the Flow-FISH protocol (6). Using this method, we first examined littermates from a cross of mTERT+/− HG5 mice and compared the telomere lengths to those of WT mice from our CAST/EiJ colony (Fig. 2A). The mTERT KOG6 mice had the shortest telomeres, followed by the mTERT+/− HG6 and WT6* mice. The mTERT+/+ WT6* mice show inheritance of short telomeres, as was seen for the WT* mice from late-generation heterozygous crosses of mTR+/− mice (3, 29).

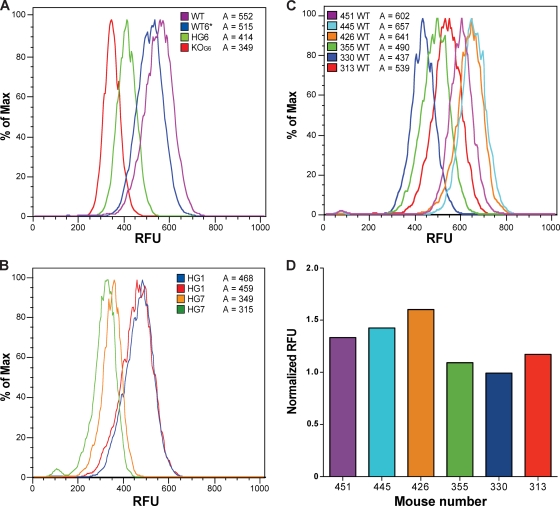

Fig. 2.

Telomere length decreases in mTERT−/− and mTERT+/− mice analyzed by Flow-FISH. (A) Flow-FISH analysis of telomere length within one litter and compared to that in WT mice. RFU is relative fluorescence units of the telomere signal (means: WT = 552 RFU, WT6* = 515 RFU, HG6 = 414 RFU, and KOG6 = 349 RFU). (B) Telomere length comparison of two HG1 mice to two HG7 mice by Flow-FISH (geometric means: HG1 = 468 RFU, HG1 = 459 RFU, HG7 = 349 RFU, and HG7 = 315 RFU). (C) Flow-FISH analysis of six independent WT mice shows heterogeneity within mice of the same genotype. The numbers indicate the numbers of mice in our colony. (D) The quantitative Flow-FISH value, normalized RFU to bovine thymocytes as an internal control, is shown for each mouse analyzed in panel C.

To examine whether there is progressive telomere shortening with successive generations in mTERT+/− mice, we compared the telomere length in two HG1 mice to that in two HG7 mice. The later-generation mTERT+/− HG7 mice had considerably shorter telomeres, indicating that mTERT is haploinsufficient (Fig. 2B). We also saw mouse-to-mouse variation in telomere length that was particularly evident in two HG7 littermates. This mouse-to-mouse variation has been noted previously in Q-FISH experiments (Fig. 1D and B) (unpublished data) and was confirmed by the analysis of six unrelated, age-matched WT mice (Fig. 2C and D). This mouse-to-mouse variation is likely due to the random inheritance of different numbers of long and short telomeres from the parents (2). Telomere length on any given chromosome end varies independently of the chromosome identity, and random segregation at meiosis then allows such individual variation to occur within litters (33).

Decreased survival with progressive breeding of mTERT+/− mice.

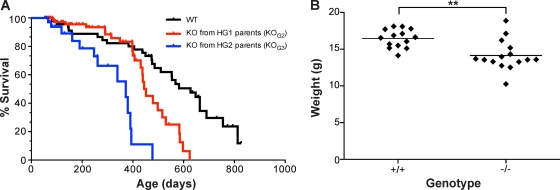

To examine the phenotypes that are due to the loss or haploinsufficiency of mTERT, we examined the survival of mTERT−/− KOG2 and KOG3 mice derived from progressive generations of mTERT+/− mice. The survival of mTERT−/− mice decreased with progressive generations of breeding. The median survival of the WT mice in our colony was 627 days (n = 45). This survival decreased in KOG2 mice born to HG1 parents (median, 452 days; n = 82) and further decreased in KOG3 mice born to HG2 parents (median, 372 days; n = 36) (Fig. 3A). Coincident with the decreased survival, there was also a decrease in body weight in the mTERT−/− mice with short telomeres (Fig. 3B). This decreased body weight is similar to that in mTR+/− mice and may be due to bone marrow failure, malabsorption secondary to the gastrointestinal defects, or typhlocolitis, an inflammation of the colon secondary to bone marrow failure (2).

Fig. 3.

mTERT−/− mice have decreased survival and body weights. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for WT (n = 45), KOG2 (n = 82), and KOG3 (n = 36) mice (median survival: WT = 627 days; KOG2 = 452 days; KOG3 = 372 days). (B) Body weight analysis of WT (n = 14, average weight = 16.47 g) and mTERT−/− (KOG2 through KOG6, n = 15; average weight = 14.15 g) mice. ** indicates P = 0.0011.

mTERT+/− and mTERT−/− mice show phenotypes associated with human syndromes of telomere shortening.

To establish the underlying cause of the decreased survival time in the mTERT+/− breeding colony, we carried out complete necropsy of WT, mTERT+/−, and mTERT−/− mice under a protocol in which the pathologist did not know the genotype of the mice under study. The mTERT−/− mice showed the most severe phenotypes, including intestinal villous atrophy and crypt depletion, occasional crypt hyperplasia and microadenomas, typhlocolitis in the large intestine, atrophy of the seminiferous tubules, extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH) in the liver and spleen, and a skewed myeloid/erythroid ratio in the bone marrow. Consistent with the haploinsufficiency seen in telomere length maintenance, mTERT+/− mice also showed similar pathology, although it was less severe than in the null animals, including a skewed myeloid/erythroid ratio, EMH, and intestinal atrophy.

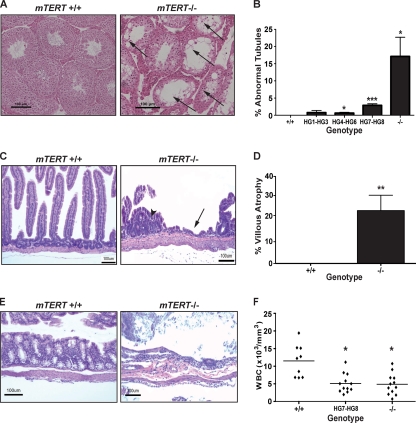

To more carefully examine the phenotypes seen in pathology, we quantitated the appearance of abnormal seminiferous tubules in the testes. Telomere shortening in germ cells leads to apoptosis in the testes (32, 42), which is evident in H&E-stained sections as hypocellular seminiferous tubules. We compared age-matched WT, mTERT+/−, and mTERT−/− mice and found a significant increase in hypocellular tubules in both mTERT+/− and mTERT−/− mice, although the phenotype was most pronounced in mTERT−/− mice, where telomeres were significantly shorter (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

mTERT−/− and mTERT +/− mice show defects in tissue renewal. (A) H&E staining of testis sections from WT (left panel) and mTERT−/− mice (right panel). Arrows show abnormal or empty tubules (magnification, ×100; scale bar = 100 μm). (B) Quantitation of abnormal tubules in mTERT+/− (HG1-HG3, n = 5; HG4-HG6, n = 6; HG7-HG8, n = 12) and mTERT−/− (n = 7) mice compared to those of WT (+/+, n = 7) mice. * indicates P < 0.05; *** indicates P = 0.0002. (C) H&E staining of small intestine sections from WT (left panel) and mTERT−/− (right panel) mice. Arrow indicates area of villous atrophy, and arrowhead indicates microadenoma (magnification, ×100; scale bar = 100 μm). (D) Quantitation of percent villous atrophy in the GI tracts of WT (+/+, n = 5) and mTERT−/− (−/−, n = 5) mice. ** indicates P = 0.003. (E) H&E staining of large intestine sections from WT (left panel) and mTERT−/− (right panel) mice. (F) White blood cell (WBC) counts of blood from WT (+/+, n = 9), mTERT+/− (HG7 and HG8, n = 12), and mTERT−/− (n = 12) mice. ** indicates P = 0.0007.

Loss of tissue renewal due to short telomeres is seen in several proliferative organs. The whole animal pathology indicated there was significant villous atrophy in the small intestine (Fig. 4C) and large intestine (Fig. 4E) in mTERT−/− mice. We quantitated the degree of atrophy in H&E-stained sections from mTERT−/− mice (Fig. 4D). mTERT−/− mice showed both significant villous atrophy and microadenomas in regions adjacent to regions of atrophy (Fig. 4C). This appearance of microadenomas is similar to what was found in mTR−/− mice and indicates that short telomeres, in addition to loss of tissue renewal, may sometimes lead to neoplastic growth (3, 29). The defect in the mTERT+/− mice was more subtle and was seen only in one older mouse. This lower penetrance of the intestinal villous atrophy in mTERT+/− mice than in mTR+/− mice is likely due to the fact that the mTR+/− colony was established 7 years earlier and has undergone additional telomere shortening during breeding, allowing phenotypes due to haploinsufficiency to be manifested.

Aplastic anemia is a common manifestation of telomere shortening in human patients with dyskeratosis congenita (7, 40). The EMH seen in the mouse is indicative of bone marrow failure. To examine potential bone marrow dysfunction, we performed complete blood cell counts and found a significant decrease in the total white blood cell counts of mTERT+/− (P = 0.0007) and mTERT−/− mice (P = 0.0007) (Fig. 4F). These decreased white blood cell counts are indicative of bone marrow dysfunction in mice with short telomeres. Therefore, the spectrum of pathological changes seen in mTERT+/− mice is similar to that previously characterized in mTR+/− mice and in dyskeratosis congenita patients.

mTERT−/− mice show no additional phenotypes not seen in mTR−/− mice.

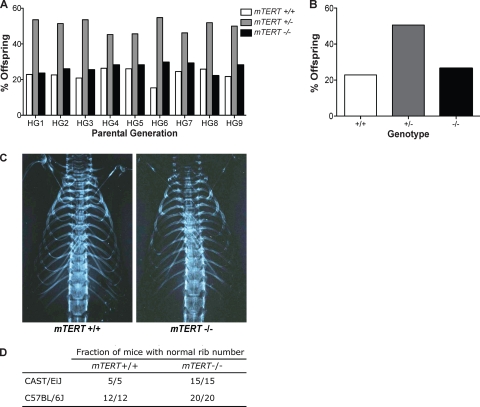

Recent experiments have suggested that TERT may have additional roles in cell growth independent of its function at telomeres (17, 55). Mice overexpressing mTERT show excessive hair growth (65). In contrast, we examined but did not find hair loss in mTERT−/− mice, indicating that absence of TERT does not affect hair growth. The TERT protein has also been suggested to play a role in the Wnt signaling pathway independent of its role at telomeres (16, 60). Most Wnt pathway mutant mice (Wnt1−/− through Wnt 11−/−) have severe developmental defects and die embryonically or right after birth (46). To determine whether we might have missed a class of mice that die embryonically due to Wnt pathway defects, we first examined the ratios of genotypes of adult offspring from our crosses. Crosses of heterozygous CAST/EiJ mTERT+/− mice yielded expected Mendelian ratios of 23% +/+, 51% +/−, and 26% −/− mice, with 1,089 mice examined (Fig. 5A and B). Thus, we find no evidence of loss of the mTERT−/− genotype due to embryonic defects.

Fig. 5.

mTERT−/− mice are born in expected ratios and show no phenotypes ascribed to Wnt signaling deficiency. (A) Quantitation of Mendelian ratios of progeny from each generation of heterozygous mice. (B) Total genotype distribution from all heterozygous crosses (n = 1,089) from CAST/EiJ mTERT+/− intercrosses: 22.9% WT, 50.6% mTERT+/−, and 26.5% mTERT−/−. (C) X rays to examine rib numbers in CAST/EiJ mTERT+/+ and mTERT−/− mice. (D) Quantitation of rib numbers from X rays of WT and mTERT−/− mice in both the CAST/EiJ and C57BL/6J genetic backgrounds.

To examine possible Wnt pathway phenotypes, we examined organs of adult mTERT−/− mice. Blinded examination of H&E-stained sections revealed no defects in the lungs, kidneys, heart, or urogenital tract in mTERT−/− mice. A previous publication (60) suggested that some mTERT−/− mice have missing ribs, which was interpreted as a Wnt pathway developmental defect. To look specifically at rib numbers, we examined X rays of both WT and mTERT−/− CAST/EiJ mice (n = 15), as well as WT and mTERT−/− C57BL/6J mice (n = 20) (Fig. 5C). All of the mice examined showed the normal number and appearance of ribs (Fig. 5D).

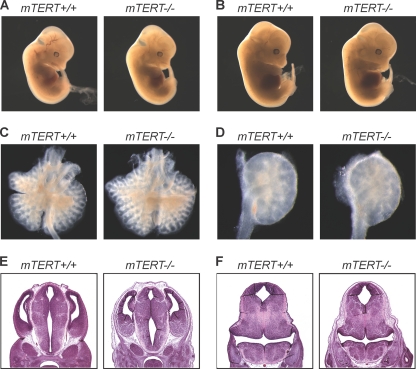

While most Wnt KO mice have severe developmental defects, it has been suggested that severe Wnt pathway defects may not be seen in adult mTERT−/− mice due to developmental compensation (60). To determine whether there may be subtle defects in the Wnt pathway in early development that may be compensated for to allow survival, we examined embryos from crosses of CAST/EiJ mTERT+/− mice. To guide our analysis, we examined specific phenotypes seen in Wnt gene KO mice. Wnt4−/−, Wnt9b−/−, and Wnt11−/− mice show defects in kidney development (38, 48, 68). Wnt2/2b−/− mice show defects in lung development (25, 59). Defects in axis development, including a truncated axis and truncated limbs, are seen in Wnt3−/−, Wnt5a−/−, and Wnt7a−/− mice (43, 61, 80). Runting and small embryo size are found in several mutants, including Wnt2−/− mice (59). Urogenital defects are seen in Wnt7−/− and Wnt 9b−/− mice (13, 56). Finally, failure of the midbrain and cerebellum to develop is found in Wnt1−/− mice (52, 53, 69). To determine whether these phenotypes are seen in mTERT−/− mice, we dissected 58 embryos from mTERT+/− intercrosses. WT and mTERT−/− embryos were examined in a blinded fashion by two experts familiar with Wnt developmental defects. The mTERT−/− embryos showed no gross morphological differences; we did not find evidence of axis truncation, limb truncation, or smaller embryo size (Fig. 6A and B). Embryos were dissected, and the lungs and kidneys were examined for morphological defects (Fig. 6C and D). We also examined embryonic brain sections for defects in the midbrain and cerebellum (Fig. 6E and F). We found no differences between WT and mTERT−/− embryos in any of the tissues examined. Our phenotypic data from Mendelian ratios and adult and embryonic tissues showed no evidence of Wnt pathway defects in two different genetic backgrounds.

Fig. 6.

mTERT−/− embryos show no phenotypes ascribed to Wnt signaling deficiency. To look for subtle phenotypes, 58 embryos were dissected and evaluated in a blinded fashion. Representative examples are shown. E13.5 (A) and E14.5 (B) WT (left panels) and mTERT−/− (right panels) whole embryos (magnification, ×0.8; n = 12 each) are shown. (C) Embryonic lungs dissected from WT (left panel) and mTERT−/− (right panel) embryos at E14.5 (magnification, ×3.2; n = 3 each). (D) Embryonic kidneys dissected from WT (left panel) and mTERT−/− (right panel) embryos at E14.5 (magnification, ×6.6; n = 3 each). Also shown are H&E-stained midbrain (E) and cerebellar primordium (F) sections from E14.5 WT (left panels) and mTERT−/− (right panels) embryos (magnification, ×2.5; n = 3 each).

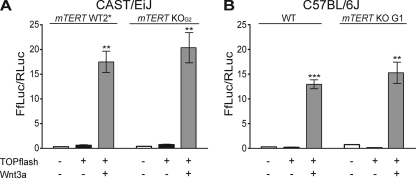

To directly investigate whether absence of TERT affects Wnt signaling, we used a functional readout of Wnt-induced transcriptional activity. CAST/EiJ and C57BL/6J WT and mTERT−/− MEFs were transformed with the TOPflash reporter plasmid, which contains 7 tandem TCF binding sites driving the luciferase reporter gene (58). To specifically activate the Wnt pathway, these cells were cotransfected with a plasmid that allows expression of the Wnt3a ligand and luciferase levels were measured. As a control, we measured the uninduced level of luciferase in cells that did not receive the Wnt3a plasmid, as well as in untransfected cells. The levels of luciferase in WT and mTERT−/− cells were indistinguishable (P = 0.487) (Fig. 7A). Since previous experiments indicating that TERT overexpression activates the Wnt pathway were done in the C57BL/6J background, we repeated the luciferase reporter experiments with WT and mTERT−/− MEFs from C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 7B) and again saw no difference in luciferase levels between WT and mTERT−/− cells (P = 0.37). Thus, we conclude that loss of TERT does not affect the Wnt signaling pathway.

Fig. 7.

mTERT−/− cells show Wnt pathway signaling activation similar to that of WT cells in vitro. Luciferase activity was measured in MEFs transfected with the TOPflash reporter plasmid and a control Renilla luciferase reporter, with and without Wnt3a ligand (see Materials and Methods), as indicated below the graphs. (A) TOPflash luciferase assay of CAST/EiJ mTERT WT2* (**, P = 0.0015, relative to basal activation) and mTERT KOG2 (**, P = 0.0031, relative to basal activation) MEFs. (B) TOPflash luciferase assay of C57BL/6J WT (***, P = 0.0021, relative to basal activation) and mTERT KO G1 (**, P = 0.0001, relative to basal activation) MEFs.

DISCUSSION

Mutations in the telomerase components hTERT and hTR lead to a spectrum of diseases of telomere shortening, including dyskeratosis congenita, pulmonary fibrosis, aplastic anemia, and liver disease, among others (2, 7, 75). To understand whether these disease phenotypes in humans are likely to all be due to telomere shortening or if some may be due to alternative functions of TERT, we examined the pathology in CAST/EiJ mTERT+/− and mTERT−/− mice in detail. We found that mTERT deficiency produces a phenotype indistinguishable from that due to mTR deficiency and worsens with each generation, indicating that short telomeres mediate disease in both mutant backgrounds.

Haploinsufficiency for mTERT results in telomere shortening and loss of tissue renewal.

We found progressive telomere shortening with successive breeding of mTERT+/− mice, indicating that loss of one allele of mTERT results in haploinsufficiency. While one previous study suggested that mTERT did not show haploinsufficiency (15), three recent studies that examined successive generations of mTERT+/− mice on the C57BL/6J genetic background found progressive telomere shortening (14, 22, 54). However, these studies using C57BL/6J mTERT+/− mice did not find phenotypic changes in later-generation heterozygotes using two different heterozygous breeding schemes (14, 54). In contrast, we found with both CAST/EiJ mTR+/− (3, 29) and mTERT+/− (this report) mice that the progressive telomere shortening with each generation is associated with a progressive decline in organ function, similar to the genetic anticipation seen in dyskeratosis congenita patients. Since many phenotypes in CAST/EiJ mTR+/− and mTERT+/− heterozygous mice are initially subtle in early generations, it is likely that the lack of phenotype expression in C57BL/6J mice is due to insufficient telomere shortening. C57BL/6J mice have unusually long and heterogeneous telomeres, and thus, the consequences of telomere shortening are not seen for many generations, even in the null background (14, 42, 54). CAST/EiJ mice have both more homogeneous and shorter telomere length distributions, similar to humans; thus, the effects of short telomeres are manifested more clearly in these mice.

Loss of mTERT does not affect Wnt signaling.

The TERT protein has been reported to function in several pathways that are independent of telomere length regulation. Overexpression of mTERT has been reported to stimulate hair follicle stem cell proliferation (65), activate transcription of the Wnt and c-myc transcriptional pathways (16, 60, 66), and affect the transforming growth factor beta regulatory pathway (24). In addition, in one study, knockdown of hTERT was implicated in the DNA damage response (51). In contrast to these results, two independent studies have examined mTERT−/− cells and found no evidence of a change in the DNA damage response (21, 71). In addition, whole-genome transcriptional analysis of C57BL/6J mTERT−/− G1 MEFs and tissues revealed no genes, including genes in the Wnt and DNA damage pathways, that were specifically up- or downregulated compared to those in WT cells (71). Here we functionally examined Wnt transcriptional pathway activation by using the TOPflash reporter assay and found similar levels of activation in WT and mTERT−/− cells.

How can we reconcile the activation of Wnt pathway genes in mTERT overexpression with the lack of changes in Wnt signaling when mTERT is deleted? It is possible that high-level overexpression of TERT generates a new gain-of-function phenotype that activates the Wnt pathway. Our studies argue that this effect of TERT is not part of its normal physiological function. Such generation of a neomorph upon high-level overexpression has a precedent in the genetic literature (37, 82). The activation of the Wnt pathway could play a role in some situations when TERT is overexpressed, even though this is not the normal role of TERT in most cells.

mTERT−/− mice show no unexpected phenotypes.

While studies of mTERT−/− cells in culture allowed the examination of transcriptional and DNA damage pathways (21, 71), careful analysis of the mTERT−/− mouse can allow phenotypes to be assessed in an unbiased manner. If TERT has essential functions other than telomere lengthening, we would expect to see phenotypes associated with those essential functions in mTERT−/− mice. In one study, mTERT−/− mice were reported to have aberrant numbers of ribs, which is suggestive of a Wnt pathway developmental defect (60). We found that mTERT−/− mice do not die embryonically, as do most Wnt mutant mice. Adult mice also did not show characteristic Wnt-related defects in the lungs, kidneys, or urogenital tract, and there was no evidence of a rib number defect. Previous reports of rib number variation may be due to mouse strain phenotypic variability, as has been previously reported (10, 27, 39). Examination of mTERT−/− embryos and embryonic tissues also revealed no subtle Wnt phenotypes. Finally, while TERT function has recently been linked to mitochondrial RNA processing endoribonuclease (RMRP) (47), the blinded total necropsy we performed showed no overt phenotypes in mTERT−/− mice that might be expected from RMRP deficiency. The phenotypes that we did find in mTERT−/− mice are very similar to those seen in mTR−/− mice, consistent with the notion that short telomeres mediate these effects.

mTR and mTERT produce indistinguishable phenotypes: implications for human disease.

The phenotypes seen in mTERT+/− and mTR+/− mice were remarkably similar to each other and recapitulate the phenotypes seen in human disease. In humans, mutations in both hTR and hTERT lead to autosomal dominant disease. Our evidence of haploinsufficiency and progressive disease onset in both mTERT+/− and mTR+/− mice is consistent with the genetic anticipation found in these families. It is still not known why some families with telomerase mutations present with dyskeratosis congenita and others present first with pulmonary fibrosis. Because of disease heterogeneity, it has been suggested that perhaps the disease spectrum may differ, depending on whether there are mutations in hTR or hTERT (23, 74, 77). Our analysis of the null phenotype for loss of either TERT or TR indicates that, in an isogenic genetic background, the phenotypes of mutations in these two components are indistinguishable. Recent studies indicate that a single mutant allele can cause heterogeneous phenotypes within a family where pulmonary fibrosis is seen in earlier generations and aplastic anemia becomes the predominant phenotype in later generations (62). This evidence further indicates that it is not the specific mutations in either hTERT or hTR that determine the disease spectrum, but rather telomere length.

In summary, we have found that loss of the protein component of telomerase, TERT, and loss of the RNA component, TR, result in indistinguishable phenotypes, suggesting that all of the phenotypes we observed are due to telomere shortening. We find no evidence of a phenotypic expression of proposed alternative functions of TERT. Understanding all of the potential manifestations of hTERT and hTR mutations has important implications for human disease. Our findings make it unlikely that specific diseases will be specifically associated with mutations in the two different components. Effort can therefore be focused on understanding how telomere shortening influences disease expression in different tissues. The ability to study the phenotype in heterozygous mice that mimic the genetic anticipation and haploinsufficiency in humans makes this a powerful model for understanding the consequences of telomere shortening.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mary Armanios, Brendan Cormack, and Jeremy Nathans for critical reading of the manuscript and Jeremy Nathans for advice and assistance in evaluating embryos for Wnt phenotypes, as well as kindly providing the luciferase assay vectors. We thank the anonymous reviewers, whose comments on the manuscript helped us to strengthen and focus our findings.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, RO1AG027406.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 April 2011.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alder J. K., et al. 2008. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105: 13051–13056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armanios M. 2009. Syndromes of telomere shortening. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10: 45–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armanios M., et al. 2009. Short telomeres are sufficient to cause the degenerative defects associated with aging. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85: 823–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armanios M., et al. 2005. Haploinsufficiency of telomerase reverse transcriptase leads to anticipation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 15960–15964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Armanios M. Y., et al. 2007. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356: 1317–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baerlocher G. M., Vulto I., de Jong G., Lansdorp P. M. 2006. Flow cytometry and FISH to measure the average length of telomeres (flow FISH). Nat. Protoc. 1: 2365–2376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bessler M., Wilson D. B., Mason P. J. 2010. Dyskeratosis congenita. FEBS Lett. 584: 3831–3838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blackburn E. H., Collins K. 21 July 2010. Telomerase: an RNP enzyme synthesizes DNA. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blasco M. A., et al. 1997. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 91: 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Branch S., Rogers J. M., Brownie C. F., Chernoff N. 1996. Supernumerary lumbar rib: manifestation of basic alteration in embryonic development of ribs. J. Appl. Toxicol. 16: 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calado R. T., et al. 2009. A spectrum of severe familial liver disorders associate with telomerase mutations. PLoS One 4: e7926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carroll K. A., Ly H. 2009. Telomere dysfunction in human diseases: the long and short of it! Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2: 528–543 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carroll T. J., Park J. S., Hayashi S., Majumdar A., McMahon A. P. 2005. Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev. Cell 9: 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chiang Y. J., et al. 2010. Telomere length is inherited with resetting of the telomere set-point. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107: 10148–10153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiang Y. J., et al. 2004. Expression of telomerase RNA template, but not telomerase reverse transcriptase, is limiting for telomere length maintenance in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 7024–7031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choi J., et al. 2008. TERT promotes epithelial proliferation through transcriptional control of a Myc- and Wnt-related developmental program. PLoS Genet. 4: e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cong Y., Shay J. W. 2008. Actions of human telomerase beyond telomeres. Cell Res. 18: 725–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. d'Adda di Fagagna F., et al. 2003. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature 426: 194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Lange T., Jacks T. 1999. For better or worse? Telomerase inhibition and cancer. Cell 98: 273–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Enomoto S., Glowczewski L., Berman J. 2002. MEC3, MEC1, and DDC2 are essential components of a telomere checkpoint pathway required for cell cycle arrest during senescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13: 2626–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erdmann N., Harrington L. A. 2009. No attenuation of the ATM-dependent DNA damage response in murine telomerase-deficient cells. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 8: 347–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Erdmann N., Liu Y., Harrington L. 2004. Distinct dosage requirements for the maintenance of long and short telomeres in mTert heterozygous mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101: 6080–6085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garcia C. K., Wright W. E., Shay J. W. 2007. Human diseases of telomerase dysfunction: insights into tissue aging. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 7406–7416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geserick C., Tejera A., Gonzalez-Suarez E., Klatt P., Blasco M. A. 2006. Expression of mTert in primary murine cells links the growth-promoting effects of telomerase to transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Oncogene 25: 4310–4319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goss A. M., et al. 2009. Wnt2/2b and beta-catenin signaling are necessary and sufficient to specify lung progenitors in the foregut. Dev. Cell 17: 290–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goytisolo F. A., et al. 2000. Short telomeres result in organismal hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation in mammals. J. Exp. Med. 192: 1625–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Green E. L. 1941. Genetic and non-genetic factors which influence the type of the skeleton in an inbred strain of mice. Genetics 26: 192–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greider C. W., Blackburn E. H. 1985. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell 43: 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hao L. Y., et al. 2005. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell 123: 1121–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harley C. B., Futcher A. B., Greider C. W. 1990. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345: 458–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hemann M. T., Greider C. W. 2000. Wild-derived inbred mouse strains have short telomeres. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 4474–4478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hemann M. T., et al. 2001. Telomere dysfunction triggers developmentally regulated germ cell apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 2023–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hemann M. T., Strong M., Hao L.-Y., Greider C. W. 2001. The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell 107: 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herrera E., Martinez A. C., Blasco M. A. 2000. Impaired germinal center reaction in mice with short telomeres. EMBO J. 19: 472–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herrera E., et al. 1999. Disease states associated with telomerase deficiency appear earlier in mice with short telomeres. EMBO J. 18: 2950–2960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. IJpma A., Greider C. W. 2003. Short telomeres induce a DNA damage response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 987–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacobs C., Pirson I. 2003. Pitfalls in the use of transfected overexpression systems to study membrane proteins function: the case of TSH receptor and PRA1. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 209: 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karner C. M., et al. 2009. Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nat. Genet. 41: 793–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khera K. S. 1981. Common fetal aberrations and their teratologic significance: a review. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1: 13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirwan M., Dokal I. 2008. Dyskeratosis congenita: a genetic disorder of many faces. Clin. Genet. 73: 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kirwan M., et al. 2009. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum. Mutat. 30: 1567–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee H.-W., et al. 1998. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature 392: 569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu P., et al. 1999. Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nat. Genet. 22: 361–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu Y., Kha H., Ungrin M., Robinson M. O., Harrington L. 2002. Preferential maintenance of critically short telomeres in mammalian cells heterozygous for mTert. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99: 3597–3602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu Y., et al. 2000. The telomerase reverse transcriptase is limiting and necessary for telomerase function in vivo. Curr. Biol. 10: 1459–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Logan C. Y., Nusse R. 2004. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20: 781–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maida Y., et al. 2009. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase formed by TERT and the RMRP RNA. Nature 461: 230–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Majumdar A., Vainio S., Kispert A., McMahon J., McMahon A. P. 2003. Wnt11 and Ret/Gdnf pathways cooperate in regulating ureteric branching during metanephric kidney development. Development 130: 3175–3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marrone A., Stevens D., Vulliamy T., Dokal I., Mason P. J. 2004. Heterozygous telomerase RNA mutations found in dyskeratosis congenita and aplastic anemia reduce telomerase activity via haploinsufficiency. Blood 104: 3936–3942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maser R. S., DePinho R. A. 2002. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science 297: 565–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Masutomi K., et al. 2005. The telomerase reverse transcriptase regulates chromatin state and DNA damage responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 8222–8227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McMahon A. P., Bradley A. 1990. The Wnt-1 (int-1) proto-oncogene is required for development of a large region of the mouse brain. Cell 62: 1073–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McMahon A. P., Joyner A. L., Bradley A., McMahon J. A. 1992. The midbrain-hindbrain phenotype of Wnt-1−/Wnt-1− mice results from stepwise deletion of engrailed-expressing cells by 9.5 days postcoitum. Cell 69: 581–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meznikova M., Erdmann N., Allsopp R., Harrington L. A. 2009. Telomerase reverse transcriptase-dependent telomere equilibration mitigates tissue dysfunction in mTert heterozygotes. Dis. Model Mech. 2: 620–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Millar S. E. 2009. Cell biology: the not-so-odd couple. Nature 460: 44–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miller C., Sassoon D. A. 1998. Wnt-7a maintains appropriate uterine patterning during the development of the mouse female reproductive tract. Development 125: 3201–3211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mitchell J. R., Wood E., Collins K. 1999. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature 402: 551–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Molenaar M., et al. 1996. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 86: 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Monkley S. J., Delaney S. J., Pennisi D. J., Christiansen J. H., Wainwright B. J. 1996. Targeted disruption of the Wnt2 gene results in placentation defects. Development 122: 3343–3353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Park J. I., et al. 2009. Telomerase modulates Wnt signalling by association with target gene chromatin. Nature 460: 66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Parr B. A., McMahon A. P. 1995. Dorsalizing signal Wnt-7a required for normal polarity of D-V and A-P axes of mouse limb. Nature 374: 350–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Parry E. M., Alder J. M., Qi J. X., Chen J.-L., Armanios M. 24 March 2011. Syndrome complex of bone marrow failure and pulmonary fibrosis predicts germline defects in telomerase. Blood [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-322149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Poon S. S. S., Lansdorp P. M. 1 November 2001, posting date Quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH). Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 18: Unit 18.14. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1804s12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rudolph K. L., et al. 1999. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell 96: 701–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sarin K. Y., et al. 2005. Conditional telomerase induction causes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells. Nature 436: 1048–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Smith L. L., Coller H. A., Roberts J. M. 2003. Telomerase modulates expression of growth-controlling genes and enhances cell proliferation. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 474–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Smogorzewska A., de Lange T. 2004. Regulation of telomerase by telomeric proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73: 177–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stark K., Vainio S., Vassileva G., McMahon A. P. 1994. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature 372: 679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Thomas K. R., Musci T. S., Neumann P. E., Capecchi M. R. 1991. Swaying is a mutant allele of the proto-oncogene Wnt-1. Cell 67: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tsakiri K. D., et al. 2007. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104: 7552–7557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vidal-Cardenas S. L., Greider C. W. 2010. Comparing effects of mTR and mTERT deletion on gene expression and DNA damage response: a critical examination of telomere length maintenance-independent roles of telomerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: 60–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vulliamy T., et al. 2001. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature 413: 432–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vulliamy T., et al. 2004. Disease anticipation is associated with progressive telomere shortening in families with dyskeratosis congenita due to mutations in TERC. Nat. Genet. 36: 447–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vulliamy T. J., Dokal I. 2008. Dyskeratosis congenita: the diverse clinical presentation of mutations in the telomerase complex. Biochimie 90: 122–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Walne A. J., Dokal I. 2009. Advances in the understanding of dyskeratosis congenita. Br. J. Haematol. 145: 164–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wong K. K., et al. 2000. Telomere dysfunction impairs DNA repair and enhances sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Nat. Genet. 26: 85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yamaguchi H. 2007. Mutations of telomerase complex genes linked to bone marrow failures. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 74: 202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yamaguchi H., et al. 2003. Mutations of the human telomerase RNA gene (TERC) in aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 102: 916–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yamaguchi H., et al. 2005. Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 352: 1413–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yamaguchi T. P., Bradley A., McMahon A. P., Jones S. 1999. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development 126: 1211–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yuan X., et al. 1999. Presence of telomeric G-strand tails in the telomerase catalytic subunit TERT KO mice. Genes Cells 4: 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang J. Z. 2003. Overexpression analysis of plant transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6: 430–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]