Early in infection, influenza, HSV-1 and Sendai virus modulate hBD-1 in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells, monocytes and epithelial cells, suggesting importance in innate immunity.

Keywords: viral, alarmins, primary cells, antimicrobial peptides, mouse

Abstract

hBD comprise a family of antimicrobial peptides that plays a role in bridging the innate and adaptive immune responses to infection. The expression of hBD-2 increases upon stimulation of numerous cell types with LPS and proinflammatory cytokines. In contrast, hBD-1 remains constitutively expressed in most cells in spite of cytokine or LPS stimulation; however, its presence in human PDC suggests it plays a role in viral host defense. To examine this, we characterized the expression of hBD-1 in innate immune cells in response to viral challenge. PDC and monocytes increased production of hBD-1 peptide and mRNA as early as 2 h following infection of purified cells and PBMCs with PR8, HSV-1, and Sendai virus. However, treatment of primary NHBE cells with influenza resulted in a 50% decrease in hBD-1 mRNA levels, as measured by qRT-PCR at 3 h following infection. A similar inhibition occurred with HSV-1 challenge of human gingival epithelial cells. Studies with HSV-1 showed that replication occurred in epithelial cells but not in PDC. Together, these results suggest that hBD-1 may play a role in preventing viral replication in immune cells. To test this, we infected C57BL/6 WT mice and mBD-1(−/−) mice with mouse-adapted HK18 (300 PFU/mouse). mBD-1(−/−) mice lost weight earlier and died sooner than WT mice (P=0.0276), suggesting that BD-1 plays a role in early innate immune responses against influenza in vivo. However, lung virus titers were equal between the two mouse strains. Histopathology showed a greater inflammatory influx in the lungs of mBD-1(−/−) mice at Day 3 postinfection compared with WT C57BL/6 mice. The results suggest that BD-1 protects mice from influenza pathogenesis with a mechanism other than inhibition of viral replication.

Introduction

One of the mechanisms common to many species as a first line of defense against pathogens is the inducible production of host-defense peptides such as defensins. Two classes, α-defensin and BD, were initially described as exhibiting broad-spectrum, in vitro antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi and mycobacteria (reviewed in refs. [1, 2]). These two homologous antimicrobial peptide classes are similar in that their members are 29- to 40-aa cationic peptides with six disulfide-linked cysteines [3]. The cysteine spacing in each class is invariantly conserved and differs between the classes. Four hBD peptides (hBD-1–4) have been isolated, but possibly, many more isoforms exist, as suggested by others searching genetic databases [4–6]. Unlike hBD-2, which is up-regulated in epithelial cells by LPS and proinflammatory cytokines, hBD-1 is expressed constitutively in epithelial cells and is not modulated by LPS [7]. However, hBD-1 is detected in monocytes, mature MDDC, and PDC and can be up-regulated in monocytes by IFN-γ and/or LPS [8–10].

Defensins are antiviral in addition to being antibacterial. Early studies showed that human neutrophil α-defensins exhibited in vitro inactivation of HSV-1 and -2, CMV, VSV, influenza virus [11], and HIV [12]. Three studies confirmed that α-defensins inhibit HIV infection and gene expression [13] and directly inactivate HIV [14, 15]. In addition, α-defensin and BD were described to inhibit infectivity of adenovirus [16] and adeno-associated virus in vitro [17]. In another study, overexpression of an α-defensin, human defensin-5, and a BD, hBD-1, in two different cell lines also provided the cultures with increased resistance to bacterial and adenoviral infection [18].

In addition to being antimicrobial, α-defensin and BD are highly chemotactic in vitro. hBD-1 and hBD-2 exhibit potent chemotactic activity for memory T cells and immature MDDC via the binding of the chemokine receptor, CCR6 [19]. In addition, hBD-3 and hBD-4 attract monocytes/macrophages [20, 21].

Viruses were shown to induce BD in epithelial cells following infection in vivo in animals [22, 23]; increased BD levels were also observed in vitro following viral infection in human epithelial cells and were associated with virus infection clinically [24, 25]. In lambs infected with parainfluenza type 3, sheep BD-1 mRNA, a homologue of hBD-1, was increased in whole lung homogenates 17 days following infection [22]. In mice, mBD-1, -2, and -3 were induced in lungs following influenza infection with a mouse-adapted strain [23]. In primary bronchial epithelial cells, human rhinovirus induced hBD-2 and hBD-3 but not hBD-1 via a possible TLR3-dependent mechanism [24, 25]. Rhinovirus introduced into nasal passages of normal volunteer patients also induced hBD-2 in nasal lavage and hBD-2 mRNA in nasal epithelium [24, 25]. One study showed that HIV-1 induced the expression of hBD-2 and hBD-3 but not hBD-1 in oral epithelial cells and that hBD-2 and hBD-3 inhibited HIV-1 replication [26]. However, human papilloma virus induced hBD-1 as well as hBD-2 and -3 in lesions from patients with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis [27]. Thus, the type of virus and its target cell may be important in the pattern of induction of BD.

To date, no studies have examined the induction of BD in cells of the immune system by influenza virus, HSV-1, or Sendai virus. As BD are antiviral and also attract cells that link the innate and adaptive immune response against viruses, we reasoned that BD might act in the first line of host defense against viruses and thus, may be induced in some of the cells important in the innate immune response against viral infection. We focused on BD induction in PDC and monocytes, as these cells produce IFN-α when infected with enveloped viruses such as HSV-1 and Sendai viruses [28]. Here, we demonstrate that viral infection of cultured PBMCs results in greatly increased levels of hBD-1 mRNA and peptide in PDC and monocytes. In addition, an initial suppression of hBD-1 in bronchial and oral (target) epithelial cells by influenza and live HSV-1, respectively, was demonstrated. We also show experiments demonstrating biological activity: when the mouse homologue of hBD-1, mBD-1, is deleted, influenza morbidity and mortality in mice are increased. Together, the results suggest that hBD-1 may play an important role in the initial defense against viruses and may be important in interfacing innate and adaptive immunity to viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, viruses, and mice

Polyclonal rabbit anti-hBD-1 antiserum and the corresponding preimmune serum were generously donated by Dr. Tomas Ganz (University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA) [29]. PR8 was kindly provided by Dr. Thomas Moran (Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA) [30]. Mouse-adapted HK18 was originally obtained from Dr. Mary Jane Selgrade (Immunotoxicology Branch, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) [31–34]. Sendai virus (Cantell strain, 6 hemagglutination units/μl) was obtained from Charles River SPAFAS (North Franklin, CT, USA). HSV (HSV-1 strain 2931) was originally obtained from Dr. Carlos Lopez (then of Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY, USA). HSV-GFP was obtained from Dr. K. Gus Kousoulas (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA). This virus contains an eGFP gene construct under an immediate early CMV promoter, allowing cells to fluoresce green upon HSV replication [35]. HSV-1 and HSV-GFP were grown and titered on Vero cells in DMEM with 2% FCS, penicillin, and streptomycin at 34°C and harvested by homogenizing cell lysates, centrifuging the debris (600 g), and freezing the supernatants at –70°C as described previously [36]. HSV titers ranged from 1.2 to 1.3 × 107 PFU/ml. UV-irradiated HSV was obtained by exposing virus stocks to 780 mJ/cm2 in a UV Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). This UV treatment completely inhibited viral replication in permissive Vero cells. Similar UV treatments of PR8 and HK18 influenza virus strains completely inhibited replication in MDCK cells. C57BL/6 mice with the mBD-1(−/−) were obtained from Dr. James M. Wilson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA) [37].

rhBD-1

rhBD-1, produced from the infection of Sf21 cells with baculovirus constructs, was kindly obtained from Dr. Aaron Weinberg (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA). The methods for production and characterization of rhBD-1 were published previously [10]. Briefly, the rhBD-1 was made following the method of Valore et al. [29] and the Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, USA) instruction manual, and hBD-1 was purified to homogeneity using an ion exchange resin followed by cyanogen bromide cleavage and reverse-phase HPLC [10]. Purity was assessed by mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequencing [10]. Biological activity was assessed by radial diffusion assay on Escherichia coli as described previously [10, 38].

In our laboratory, hBD-1, -2, and -3 gene expression was confirmed by cloning (using the TopoTA kit from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and sequencing the cDNA products from RT-PCR of purified human monocytes (hBD-1) stimulated with virus and NHBE cells stimulated with 100 ng/ml IL-1β (hBD-2 and hBD-3).

Isolation of PBMC and monocytes

Fresh heparinized peripheral blood was obtained from normal, healthy volunteers with informed consent, and cells were isolated at room temperature. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), enumerated with a Coulter Z1 particle counter (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL, USA), and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Monocytes were isolated from PBMCs to 98–100% purity (as determined by detecting CD14+ expression with flow cytometry), using a positive-selection kit containing magnetic beads conjugated to antibodies against CD14, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). Cells were resuspended in RPMI medium at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml.

Isolation of PDC

Peripherial blood (300 ml) was drawn from each donor, and PBMCs were isolated as described above. PDC comprised 0.1–0.5% of PBMCs. PDC were directly isolated from PBMCs via a positive selection using BDCA-4 antibodies conjugated to magnetic beads, or PDC were purified from PBMCs via a relatively new negative-selection PDC isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity ranged from 85% to 97% using the positive-selection method (as determined by high expression of surface markers detected with flow cytometry using BDCA-2-FITC, HLA-DR-APC, and CD123-PE surface staining). An example of a flow cytometry plot of these purified PDC populations is shown elsewhere [39]. Purity ranged from 93% to 97% using the negative-selection method, but yields were only 0.1–0.7 × 106 cells/300 ml peripheral blood. hBD-1 was analyzed in these samples by real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR; described below).

Cell culture of epithelial cells

NHBE cells were obtained from Cambrex (Walkersville, MD, USA) and grown in bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM Bullet kit, Lonza, Switzerland), supplemented with a packet containing bovine pituitary extract, insulin, hydrocortisone, retinoic acid, transferrin, triiodothyronine, epinephrine, and human epithelial growth factor, according to the manufacturer's directions. NHBE (passage-5) cells were seeded onto six-well tissue-culture plates at a density of 0.35 × 106 cells/well and incubated overnight. Old medium was removed, and 2 ml fresh medium was added to each well. Cells were incubated in fresh media for 24 h prior to addition of PR8 influenza virus.

OKF6/TERT cells, an immortalized cell line derived from keratinocytes, were obtained from Dr. James Rheinwald (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA) and grown in keratinocyte growth medium (Lonza) as described [40]. Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in humidified incubators to 70–80% confluence before stimulation.

Stimulation of cells with virus

NHBE cells were treated with PR8 influenza virus at a MOI of 1:1 or 10:1 for 3 h or 18 h. In another experiment, NHBE cells were treated with PR8 at MOI = 1 for 3 h and 6 h with live or UV-inactivated (780 mJoules/cm2 UV light) virus. OKF6/TERT cells were treated with HSV-1 2931 or HSV-GFP at a MOI of 1:1 for 0–8 h or at a MOI of 1:1 or 10:1 for 18 h. OKF6/TERT cells were also treated for 18 h with live or UV-inactivated virus at a MOI of 1:1. Finally, OKF6/TERT cells were treated with 1 μg/ml CpG-A DNA (UMDNJ Molecular Resource Facility, Newark, NJ, USA) or 40 μg/ml poly I:C (Sigma-Aldrich) for 18 h.

PBMCs were treated with PR8 influenza, HSV-1 2931, HSV-GFP, or Sendai virus, Cantell strain, at a MOI of 1:1 for 0–8 h prior to qRT-PCR and intracellular flow cytometric analysis for hBD-1 mRNA and peptide, respectively. Purified PDC and monocytes were infected with HSV and influenza virus at a MOI of 1:1 for 2, 3, and 6 h prior to mRNA analysis by semi-qRT-PCR and qRT-PCR.

Total RNA extraction

Cell samples were lysed and homogenized using a QIAshredder after resuspending them with RLT buffer from an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA was isolated according to the directions in the kit and resuspended in 30 μl RNase-free deionized water. Concentrations and purity of total RNA samples were determined by a 260/280-nm ratio on a UV spectrophotometer. Ratios ranged from 1.2 to 1.8.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was performed using reagents from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). For detection of BD in PBMCs incubated with and without virus, RNA was isolated and subjected to multiplex RT-PCR using oligo dT to prime the RT reaction and murine leukemia virus RT (one cycle at 42°C for 15 min, 99°C for 5 min, and then hold at 4°C), followed by PCR with the respective BD and β-actin primers in the same PCR reaction tube as described above. RT-PCR generated products of 178 bp for hBD-1, 254 bp for hBD-2, 166 bp for hBD-3, 92 bp for hBD-4, 333 bp for exon 7 of human G6PD, and 550 bp for β-actin. For detection of hBD-1 mRNA in purified PDC and monocyte populations and in fresh PBMCs, RT used murine leukemia virus RT and the respective reverse primer (Table 1) to prime the RT reaction as above. RT-PCR lacking RT was also performed on samples as a control. The specific PCR primer sequences for hBD-1–4 (synthesized by the UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School Molecular Core Facility) are shown in Table 1. After PCR for 30 cycles (one cycle at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and then 72°C for 2 min), levels of hBD-1 cDNA were visualized by gel electrophoresis of amplified products in 3% agarose and stained with 10 μg/ml ethidium bromide.

Table 1. Specific Oligonucleotide Primer Sequences Used in Semi-RT-PCR for BD Gene Expression in PBMCs Monocytes, and PDC.

| hBD-1 | 5′-AGTTCCTGAAATCCTGAGTGTTGC-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-CAGAATAGAGACATTGCCCTCCAC-3′ REVERSE | |

| hBD-2 | 5′-AAGAAAGGCCTCTCCTGAGT-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-AGTAAGCTTCACCAGGAGCTC-3′ REVERSE | |

| hBD-3 | 5′-GCTCTTCCTGTTTTTGGTGC-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-TCTTCGGCAGCATTTTCG-3′ REVERSE | |

| hBD-4: | 5′-TGCTGCTATTAGCCGTTTCTCTT-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-GGCAGTCCCATAACCCATATTC-3′ REVERSE | |

| β-actin | 5′-GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-GTCCTTAATGTACGCACGATTTC-3′ REVERSE | |

| G6PD | 5′-CACCTTCAAGGAGCCCTTTG-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-GCAAGACTCACTTCCTGATCC-3′ REVERSE |

qPCR

For qPCR, mRNA levels were quantified using a MyCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). RNA from PDC, monocytes, and epithelial cells was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen) priming with oligo dT for monocytes and epithelial cells, and the specific downstream primer for PDC mRNA. cDNA (2 μl) was amplified by PCR and visualized by gel electrophoresis. cDNA from reverse-transcribed mRNA was analyzed for hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3, IFN-α1/13, and IFN-α8, with β-2 microglobulin as a housekeeping control. A total of 1 μl cDNA was analyzed using a final concentration of 100 nM primers, 2× SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) in a volume of 20 μl. qRT-PCR primers used are shown in Table 1. Amplification was carried out in triplicate for 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. For PDC amplification, a 1-min extension at 72°C was included per cycle. All amplified products were assessed for quality by melt-curve analysis, followed by gel electrophoresis. Fold change in mRNA levels was quantified by the ΔΔ comparative threshold method normalized to β-actin.

Intracellular flow cytometry for hBD-1 or IFN-α and FACS analysis of cell surface phenotype

Following incubation with or without virus, cells were washed with 3 ml 0.1% BSA in PBS. Cell pellets were then surface-stained by incubating 5 μl normal human serum and 5 μl mAb conjugated to fluorochromes (Bectin Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA) to detect the following combinations of cells: for PDC and monocytes in the same sample, CD123-PE and HLA-DR-PerCP (PDC markers are CD123high, HLA-DR+ and are lineage–) and CD14-APC (CD14+ for monocytes) were used. For PDC and MDC in the same sample, CD123-PE, HLA-DR-PerCP, and CD11c-APC were used (PDC are CD123high, CD11c–, HLA-DR+; MDC are CD123low, CD11c+, HLA-DR+). For lymphocyte typing in the same sample, CD4-PE, CD3-biotin-streptavidin-QR, and CD8-APC or CD3-PE, CD19-PerCP, and CD14-APC were used to detect CD3+, CD4+ Th cells, CD3+, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and CD19+, CD3– B cells. Matching mouse IgG isotypes conjugated to identical fluorochromes were used as isotype controls: IgG1-PE, IgG1-PerCP, and IgG2a-APC. Cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min, washed once with cold PBS, and fixed overnight with 1% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in PBS.

Cells were stained for intracellular hBD-1 [10] or IFN-α [40, 41] at room temperature the next day as described. Briefly, cells were washed once with 2% FCS in PBS (flow wash buffer) and permeabilized with 0.5% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) in flow wash buffer for 15 min. Cell pellets were then incubated with 5 μl normal human serum for 10 min, followed by the addition of 5 μl/tube rabbit anti-hBD1 antiserum, diluted 1:10 in PBS (final concentration ∼1:250), or similarly diluted preimmune rabbit serum for 1 h. Cells were then washed with permeabilization buffer twice and then incubated for 30 min with 5 μl FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA). For IFN-α detection, PBMCs were incubated 30 min with biotinylated mAb against IFN-α, followed by incubation with streptavidin-QR (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. Following sequential washes with permeabilization buffer, flow wash buffer, and PBS, cells were fixed again with 1% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer with CellQuest analysis software (Becton Dickinson).

Endotoxin analysis

Supernatant samples were tested for endotoxin contamination using the Limulus amoebocyte lysate gel clot kit (Associates of Cape Cod, Woods Hole, MA, USA). The kit was standardized to detect 25 pg/ml E. coli 0111:B4 LPS or 0.125 EU/ml. Supernatants were diluted tenfold in pyrogen-free water (Invitrogen), and 0.2 ml each dilution was tested in the assay. After incubation at exactly 37°C for 1 h, tubes were examined for clot formation. Samples inducing the clot to form were considered to contain >25 pg/ml LPS.

HSV plaque assay and hBD-1 plaque inhibition assay

Vero cells were seeded with 150 μl/well in a 96-well plate at a density of 1.8 × 105 cells/ml in DMEM with 5% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity until confluent. Solutions of rhBD-1 ranging from 0 to 50 μg/ml were used to treat 1.2–1.3 × 104 PFU HSV/ml PBS at 37°C for 1 h in siliconized Eppendorf tubes (the final FCS concentration was 0.002%, obtained by diluting the virus stock 1:1000 in PBS). The aqueous stock solution of 1 mg/ml hBD-1 was stored at –20°C and was not thawed more than once. Serial dilutions of the treated virus were then made in DMEM with 2% FCS. Following removal of the DMEM growth medium on the Vero cells, each dilution of the hBD-1-treated HSV was put on the cell cultures in sextuplicate and incubated for 2 h. One drop (50 μl) of RPMI medium containing methylcellulose was layered over each well, and cultures were incubated further for 48 h. The cells were stained with crystal violet, and plaques were counted using an inverted microscope. PFU/ml was determined by averaging the number of plaques in each of the six wells.

Influenza morbidity and mortality studies

Groups of 11 C57BL/6 WT and 20 mBD-1(−/−) 12- to 16-week-old male mice were lightly anesthetized with an i.p. injection of ketamine/xylazine (40 mg/kg/5 mg/kg). Mice were then infected intranasally (in 5 μl increments) with 300 PFU mouse-adapted HK18 virus or this virus inactivated by UV light (780 mJoules) in 50 μl HBSS– (Invitrogen). Initial weights were taken, and individual mouse weights were recorded daily after infection. Percent body-weight loss was recorded for each individual mouse and then averaged for WT and KO mice. Daily mortality was also recorded.

Histopathology in mBD-1(−/−) versus WT mice

WT and KO mice (four/group) were sacrified following infection with 300 PFU HK18 influenza virus on Days 3 and 6. Ten percent buffered formalin was infused into the lungs via a cannula, and lungs were excised and stored for 24 h in 10% buffered formalin. Lungs were gradually dehydrated with daily changes of 50%, 70%, and 95% ethanol prior to the embedding process in paraffin. The Imaging Core Facility at UMDNJ performed embedding and sectioning. Lungs were scored according to inflammatory cell infiltrate along the bronchioles and alveolar spaces, along with hemorrhage and perivascular edema.

Virus titers in mBD-1(−/−) versus WT mice

WT and KO mice (five/group) were killed 24 h following infection with 300 PFU HK18 influenza virus. Lungs were weighed, homogenized by mortar and pestle with sterile sand in a 10% w/v amount of HBSS–, and centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min to remove debris, and the supernatants were stored at –70°C. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay using MDCK cells [33].

Statistical analysis

Differences in human PDC, monocyte, and epithelial cell hBD-1 and IFN-α mRNA levels comparing mock and virus-stimulated cells were assessed by Student′s t test or if multiple comparisons were made, Tukey's test. Mouse mortality curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. For body-weight loss, ANOVA and Tukey's test for multiple comparisons were used to compare the differences between influenza-infected WT and mBD-1(−/−) mice. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Detection of hBD-1 gene expression in fresh and virus-stimulated PBMCs

To determine if there was a basal level of BD mRNA in fresh mononuclear cells, human PBMCs were obtained from a single donor, and the mRNA was immediately isolated and analyzed by RT-PCR. Oligonucleotide primers for all four hBD (Table 1) were used to prime the RT reaction and for PCR. G6PD primers were used as a control (not shown). Only hBD-1 mRNA was detected, and no hBD-2, hBD-3, or hBD-4 was detected in fresh PBMCs (Fig. 1A). Duplicate samples with no RT showed no bands (data not shown). Fig. 1B also shows basal hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3, and hBD-4 gene expression in cultured NHBE cells as a positive control.

Figure 1. Expression of hBD-1 mRNA (A) in fresh human PBMCs using RT-PCR and (B) in mock-stimulated and virus-stimulated PBMCs using real-time qRT-PCR.

(A) BD gene expression in fresh PBMCs without virus stimulation (from Donor #2 in B). Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed with the specific primers for hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3, and hBD-4 (Lanes 1–4, respectively). RNA from NHBE cells was also assayed for hBD-1–4, and gene expression of each BD is shown below. The oligonucleotide sequences are shown in Table 1. The lane labeled with “M” used a 123-bp MW marker to assess size. Only hBD-1 was expressed at the basal level in PBMCs (Lane 1). Below is the basal expression of hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3, and hBD-4 in unstimulated NHBE in liquid culture. (B) Individual variation of increased hBD-1 mRNA by viruses. qRT-PCR detected variable stimulation of hBD-1 gene expression in total mRNA from PBMCs of four donors stimulated with PR8 influenza, HSV-1, or Sendai virus for 3, 6, or 18 h. Each sample was assayed in triplicate using the oligonucleotide primer sequences in Table 2. All viruses increased gene expression of hBD-1. Error bars indicate sd of the mean indicated by the height of the bar. Levels were compared with those of fresh PBMCs and seemed to be donor-dependent.

Table 2. qPCR Primer Sequences (Spanning an Intron).

| hBD-1a | 5′-CGC CAT GAG AAC TTC CTA CCT TCT G-3′ FORWARD |

| hBD-1 | 5′-GAA TAG AGA CAT TGC CCT CCA CTG C-3′ REVERSE |

| 5′-GAT CAT TAC AAT TGC GTC AGC AG-3′ FORWARD | |

| 5′-CTC ACT TGC AGC ACT TGG CCT TC-3′ REVERSE | |

| hBD-2 | 5′-GAT GCC TCT TCC AGG TGT TTT TGG-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-TTG TTC CAG GGA GAC CAC AGG TG-3′ REVERSE | |

| hBD-3 | 5′-TAT CTT CTG TTT GCT TTG CTC TTC C-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-CCT CTG ACT CTG CAA TAA TAT TTC TGT AA-3′ REVERSE | |

| IFN-α8 | 5′-TCT CTC CTT TCT CCT GCC TGA A-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-GCT TGA GCC TTC TGG AAC TGT TTA T-3′ REVERSE | |

| IFN-α1/13 | 5′-GCA ATA TCT ATG ATG GCC TCG C-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-GGT CTC AGG GAG ATC ACA GCC-3′ REVERSE | |

| β-actin | 5′-AGT CCT GTG GCA TCC ACG AAA CTA C-3′ FORWARD |

| 5′-CTT CTG CAT CCT GTC GGC AAT G-3′ REVERSE |

Used for influenza-stimulated PDC.

To examine whether the viral induction of hBD-1 was common in other individuals and whether other enveloped viruses compared with influenza similarly induced hBD-1, the effect of three different viruses on hBD-1 expression was compared on PBMCs of four healthy individuals using qRT-PCR. Cells were mock-infected or infected for 3, 6, and 18 h with PR8 influenza virus, HSV-1, or Sendai virus. Fig. 1B demonstrates that hBD-1 gene expression was induced to a great extent in all PBMC samples infected with influenza or Sendai virus, whereas no hBD-1 gene expression was detected in the mock-infected PBMCs. HSV-1 stimulated hBD-1 in PBMCs to a much lesser extent. Levels of hBD-1 peaked as early as 3 h in some individuals and remained elevated or decreased by 18 h. There was a high variability in the samples from different donors in terms of the degree of stimulation of hBD-1 by the three viruses.

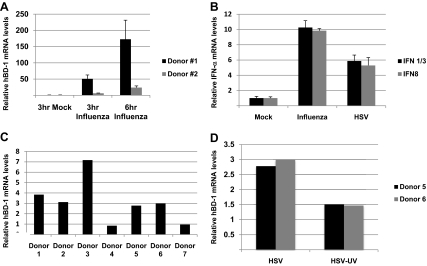

Detection of hBD-1 and IFN-α gene expression in virus-stimulated PDC and monocytes

We identified that PR8 influenza virus and HSV-1 stimulated positively and negatively selected, purified PDC to increase hBD-1 mRNA 3- to 200-fold above mock (medium)-stimulated PDC (Fig. 2A, C, D). To first identify which cell type was responding to viral stimulation, hBD-1 gene expression was examined in purified PDC populations using the specific priming RT method for semi-qRT-PCR. The purified, positively selected PDC populations contained 85% and 97% BDCA-2+ PDC. In these highly purified PDC populations from two separate donors, HSV induced an increase in hBD-1 mRNA, confirming that the increase was directly in this cell type (data not shown).

Figure 2. qRT-PCR detecting hBD-1 and IFN-α1/13 and IFN-α8 gene expression in PDC.

(A) hBD-1 mRNA following a 3- and 6-h stimulation of 96% pure PDC with PR8 influenza virus in two donors (different donors from the semi-quantitative experiments). The increase is significant in both samples, as measured by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (P<0.001). (B) IFN-α1/13 and IFN-α8 mRNA increases following a 2-h incubation with PR8 influenza and HSV-1 in the same two donors. (A and B) Error bars indicate the sd of the mean value of the qRT-PCR. (C) qRT-PCR of HSV-stimulated, 96%-purified PDC from different donors after 6 h. (D) UV inactivation of HSV-1 prevented the virus-induced increase of hBD-1 mRNA. In all figures, medium-stimulated PDC was given a value of 1.0, and all bars of each donor are relative to their medium-stimulated control.

The results with HSV-1 were confirmed in Fig. 2C and D in different donors using the negatively selected PDC. Fig. 2C demonstrates that highly purified PDC from different donors have increased hBD-1 following viral stimulation using qRT-PCR. As shown in this figure, 6-h HSV-stimulated PDC from all but two donors produced hBD-1, showing the variability of the response in different individual donors. However, on average, highly purified PDC did respond to HSV-1, and this increase is eliminated by HSV-1 treatment with UV light for 10 min (Fig. 2D). Fig. 2A shows PDC from two different donors, stimulated with PR8 influenza virus for 3 h and 6 h using qRT-PCR. The levels of hBD-1 mRNA are compared with a mock, 6-h infection. The purity of the cells was 95%; the contaminating cells, the B-lymphocytes, do not produce hBD-1 (data not shown), which was induced in PDC by PR8 influenza virus as early as 3 h in both donors.

As hBD-1 was increased early (within 3 h) after infection, we examined whether IFN-α mRNA also increased early, as PDC are known to produce nanogram amounts of IFN-α. Using Donor #1 in Fig. 2A and C, 6.7 × 105/ml purified PDC were also incubated with media (mock), PR8 influenza, or HSV for 2 h. Fig. 2B shows that there was a substantial, early IFN-α gene expression response of PDC to both viruses, and a five- to tenfold increase of the mRNA of two common subtypes was detected (with HSV stimulating twofold less IFN-α gene expression than PR8 influenza virus).

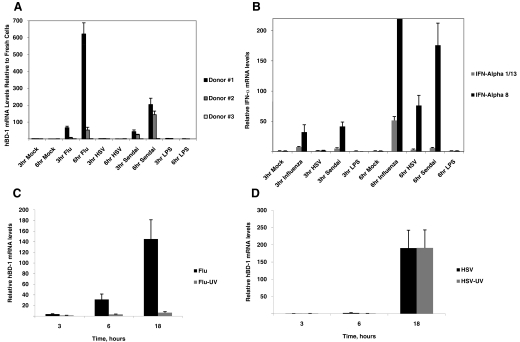

To determine whether virus induced hBD-1 in monocytes, highly purified monocytes (99%) were stimulated with virus and hBD-1 gene expression assessed by qRT-PCR. In Fig. 3A, monocytes expressed hBD-1 upon influenza and Sendai virus stimulation in the same two donors as in Fig. 2A. A third donor had little increased hBD-1 gene expression in monocytes following influenza and Sendai virus stimulation at 3 h or 6 h. HSV was not a strong stimulator of hBD-1 in monocytes at these time-points but stimulated monocytes to produce hBD-1 at 18 h (Fig. 3D). Although PR8 influenza stimulated hBD-1 gene expression in PDC and monocytes, the levels were very different, as demonstrated in Fig. 1 with PBMC. With PR8 influenza, UV-treated virus did not stimulate hBD-1 in monocytes (Fig. 3C), but UV-treated HSV-1 stimulated hBD-1 to levels of untreated virus (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. qRT-PCR detecting hBD-1 and IFN-α1/13 and IFN-α8 gene expression in monocytes.

(A) hBD-1 mRNA increases relative to mock-stimulated monocytes following a 3- and 6-h stimulation of 100%-purified monocytes stimulated with PR8 influenza, HSV-1, and Sendai viruses in the same two donors as Fig. 2A, plus a new third donor. LPS stimulation (100 ng/ml) was used as a negative control. (B) IFN-α subtypes 8 and 1/3 mRNA increases above that of fresh monocytes from Donors #1 and #2 stimulated for 3 h and 6 h with the same agents as in A. (C) Monocytes stimulated with PR8 influenza and (D) HSV-1 with their UV-inactivated (10 min) counterparts (bars indicate mean and sd of n=3 donors). UV-inactivated influenza stimulated increases in hBD-1 mRNA in monocytes but did not inactivate this effect by HSV-1. In all graphs, medium controls are normalized to 1.0.

IFN-α gene expression was also examined in purified monocytes stimulated for 3 h and 6 h with PR8 influenza, HSV-1, and Sendai viruses (Fig. 3B). Monocytes produced IFN-α protein only with influenza and Sendai viruses but not HSV (data not shown), but the qRT-PCR detected stimulation of the IFN-α8 subtype as early as 3 h with influenza and Sendai but not HSV and high levels at 6 h with all three viruses. The IFN-α1/13 subtype was stimulated at much smaller levels at 3 h and 6 h by influenza and Sendai viruses and not at all by HSV. LPS did not stimulate either IFN-α subtype in monocytes.

To control for the possibility that hBD-1 induction in PDC and monocytes was influenced by or as a result of contaminating endotoxin, we measured endotoxin activity in supernatants collected after infection and took precautions to use LPS-free medium and plasticware in our experiments. Most supernatants did not contain endotoxin; those that did had no more than 250 pg/ml, a level that does not stimulate the production of hBD-1 [10]. Whereas HSV-1-stimulated hBD-1 mRNA increases, purified LPS did not stimulate hBD-1 mRNA in 85%- and 97%-purified PDC populations from two donors (semi-qRT-PCR; data not shown), agreeing with our previous study that found no hBD-1 peptide up-regulation in PDC with purified LPS [10]. LPS stimulated little or no hBD-1 or IFN-α mRNA in monocytes (Fig. 3A and B).

Using HSV-GFP to infect PBMC and isolated PDC, GFP expression was not detected by flow cytometry or by fluorescent microscopy in hourly samples over an 8-h time period. No GFP was detected at 24 h after infection, indicating that HSV-1 replication does not occur in PDC. In contrast, similar infections of MDDC with HSV-GFP showed GFP expression at 24 h [42].

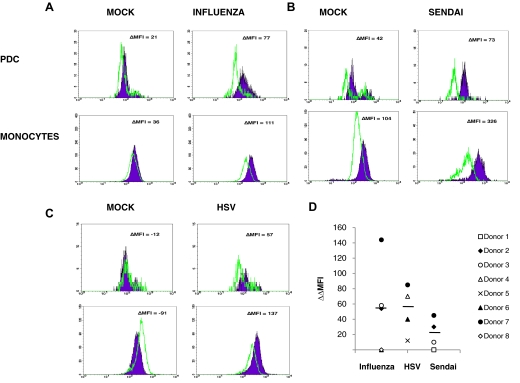

Detection of intracellular hBD-1 peptide in PDC and monocytes

We have demonstrated previously that hBD-1 can be detected in cells in a PBMC population by flow cytometry following incubation for 2 h with commercial LPS [10], providing us with a very sensitive method to study the potential expression of BD in a variety of cells of the immune system. As we observed an induction of hBD-1 gene expression in PDC with three viruses, a time course for hBD-1 peptide induction following the incubation of PBMC by HSV, influenza, and Sendai virus from 0 to 6 h was performed using two donors/virus (six different donors in all; data not shown). PDC and monocytes within the PBMC population were gated and analyzed for hBD-1 peptide via intracellular and four-color flow cytometry in PDC and monocytes as described [10]. Only a small amount of hBD-1 was detected at 1 h after stimulation, possibly as no brefeldin A was added prior to staining (brefeldin A inhibits the de novo expression of cytokine mRNA in cells [43]), and the hBD-1 was secreted in the medium. The increased expression of intracellular hBD-1 peptide was optimally detected from 2 h to 3 h after stimulation. All three viruses induced hBD-1 in PDC and monocytes 2 h after infection (Fig. 4A–C). Beyond 3 h, the detection of hBD-1 became variable as a result of increasing amounts of hBD-1 detected in the mock-infected cells compared with the virus-infected PBMCs. This was also noted in our previous study [10].

Figure 4. Intracellular hBD-1 in PDC and monocytes in PBMCs stimulated for 2 h with no virus (mock), influenza virus, HSV, or Sendai virus.

Representative data from different donors (#7, #2, and #4 in D) are shown in A (influenza), B (Sendai virus), and C (HSV-1). Filled peaks represent anti-hBD-1 (1:250) antiserum compared with solid lines representing preimmune rabbit serum (1:250). Secondary staining was performed using goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to FITC. The ΔMFI between the hBD-1 antiserum and preimmune antiserum is shown in each histogram. PDC stimulated with influenza and Sendai viruses showed the greatest amount of hBD-1 induction. Monocytes stimulated with influenza and HSV showed a much smaller induction of hBD-1. (D) Variation between donors regarding virus-induced hBD-1 in PDC. PBMCs were stimulated for 2 h with virus in the presence of brefeldin A (added 1.5 h after 30-min stimulation), and hBD-1 was analyzed in PDC by flow cytometry as described above. ΔMFI was determined by comparing the geometric MFI of anti-hBD-1 antiserum with the MFI of normal rabbit serum in virus-stimulated cells. The ΔMFI was also determined in unstimulated cells. Δ(ΔMFI) was then determined. Lines indicate the mean Δ(ΔMFI) for each group. Most normal donor PDC responded to each virus, but there was variability in response by one individual to different viruses and also between different donors to a single virus (Donors #6 and #8 did not respond to PR8 influenza). Not all viruses were tested with each donor.

Fig. 4D demonstrates the variability of the virus-induced hBD-1 response and summarizes the detection of hBD-1 peptide in various donors, as detected by flow cytometry, showing the difference in MFI between the mock and virus-stimulated PDC within the PBMC population from eight different donors. Differences between the MFI of the mock-stimulated PDC and the MFI of the virus-stimulated PDC were greater in some individuals than with others. The hBD-1 increase by each virus was detected in PDC of several individuals but not in others, and the response of PBMCs from a single donor to different viruses varied. However, PDC of most individuals responded to each virus by increasing intracellular hBD-1 within 2–3 h. In CD19+ B-lymphocytes and CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes, hBD-1 increases were not seen at this early time (data not shown).

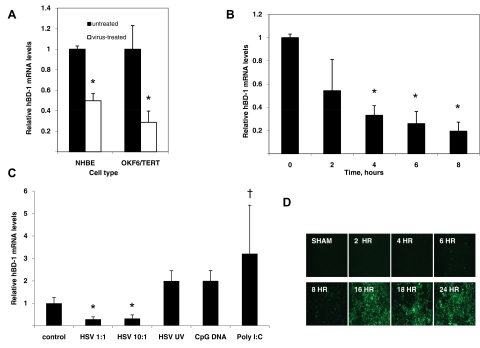

Modulation of hBD-1 gene expression in target epithelial cells by influenza and HSV-1

Epithelial cells are known to express basal levels of hBD-1; gene expression of this BD is known to be unaffected by LPS or cytokines, but stimulation effects with HSV-1 and influenza virus on hBD-1 gene expression in their target epithelial cells have not been studied. To determine the effect of viral challenge on epithelial cells, airway (NHBE) and gingival (OKF6/TERT) cells were infected with PR8 influenza virus or HSV-1, respectively. Total mRNA was isolated, and hBD-1 mRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR relative to untreated cells. The results in Fig. 5A demonstrate that in contrast to PDC, hBD-1 mRNA levels decreased significantly (P≤0.05) by ∼50% in NHBE in response to viral challenge after 3 h. Fig. 5A also shows that HSV-1 decreases hBD-1 levels in OKF6/TERT cells after 3 h. hBD-1 mRNA levels in oral epithelial cells (OKF6/TERT cells) decreased over time to 8 h (Fig. 5B). The HSV-1-induced hBD-1 mRNA inhibition occurred at MOI = 1 or 10 (Fig. 5C). Infection of cells with HSV-GFP demonstrated fluorescent cells at 8 h, indicating little replication had occurred prior to this point (Fig. 5D). HSV-GFP also decreased hBD-1 levels significantly at 3 h after infection (data not shown). Further challenge of OKF6/TERT cells with HSV-1 for 18 h did not result in hBD-1 mRNA induction (data not shown). To determine whether this inhibition required live virus, OKF6/TERT cells were incubated with live HSV-1, UV-inactivated virus, or CpG DNA oligonucleotide. The results shown in Fig. 5C demonstrate that the reduction in hBD-1 mRNA levels requires live virus and that nonmammalian CpG DNA is not sufficient to significantly stimulate or reduce hBD-1 gene expression. However, the results with poly I:C, a synthetic RNA, are similar to that observed with other microbe-associated molecular patterns and increased hBD-1 significantly in OKF6/TERT cells [44].

Figure 5. Effect of virus challenge on hBD-1 gene expression in target epithelial cells.

(A) NHBE cells were treated with influenza virus, and OKF6/TERT cells were treated with HSV-1 at a MOI of 1:1 for 3 h. Total mRNA was isolated, and hBD-1 mRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR relative to β-actin. The qRT-PCR was carried out in triplicate, and data are shown as mean ± sd of qRT-PCR values for five cultures/infected cells and two cultures for mock-infected cells. Reduction in hBD-1 mRNA levels is significant by t test (P<0.01). (B) OKF6/TERT cells were treated with HSV-1 at a MOI of 1:1 for 0–8 h. Total mRNA was isolated, and hBD-1 mRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Reduction in hBD-1 mRNA levels is significant by one-way ANOVA (*P=0.03). (C) OKF6/TERT cells were challenged for 18 h with live HSV-1 at a MOI of 1:1 or the equivalent viral dose after viral inactivation by UV treatment or at a MOI of 10:1 of live HSV-1 for 18 h. Cells were also treated with 1 μg/ml CpG and 40 μg/ml poly I:C. Results were compared by ANOVA followed by Tukey's testing for multiple comparisons. Each bar represents the mean among three cultures, and error bars indicate sd. Only live HSV suppressed hBD-1 (*P<0.01). Incubation with poly I:C increased hBD-1 levels (†P<0.04). (D) Visualization of GFP in OKF6/TERT cells infected with HSV-1 (n=3; only one represented). Upon replication, when enough GFP is expressed, cells glow fluorescent green (beginning at 6 h).

Direct hBD-1 antiviral activity

α-Defensins have been shown to inactivate viruses directly, so we wanted to determine whether hBD-1 directly inactivates a virus used in our study. In two experiments using a standard plaque assay [36] to measure antiviral activity of rhBD-1 against HSV-1, using a direct treatment protocol modeled from a prior study [45], we observed an IC50 within the range reported for α-defensins with rhBD-1 reconstituted fresh with distilled pyrogen-free water (data not shown). The IC50 was 3, previously 4, μM. The maximum hBD-1 concentration tested, 50 μg/ml, yielded a 1.5-log reduction in virus titer. Freezing and thawing of hBD-1 more than once attenuated the antiviral activity and also inactivated antibacterial activity against E. coli, demonstrating that hBD-1 is labile. Thus, hBD-1 had very weak activity against HSV-1.

Studies exploring the role of BD-1 in a mouse influenza model of infection

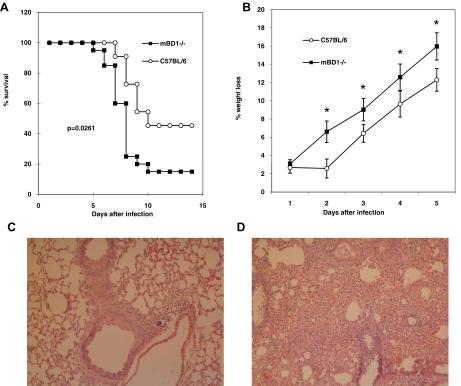

The differential regulation in epithelial cells and in PDC and monocytes suggests that hBD-1 may enhance innate immunity against influenza virus and possibly other viruses. To begin to study the role of BD-1 in vivo, WT C57BL/6 and mBD-1(−/−) male mice (KO) were infected with a mouse-adapted strain that is well characterized in our laboratory [32–34] The KO mice died 2 days faster than WT, and by Day 14, mortality was tripled in the KO mice (P=0.0276 by the log-rank test; Fig. 6A). The KO mice also had a significantly higher percentage of body-weight loss during the first 5 days of infection (P<0.05; Fig. 6B), indicating that mBD-1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of the virus. Groups infected with UV-inactivated HK18 influenza virus had no mortality, and no body-weight loss occurred in either strain (data not shown).

Figure 6. Survival and weight loss of WT and mBD-1(−/−) mice following infection of mice with mouse HK18.

(A) Kaplan-Meyer plot of survival of WT C57BL/6 male mice and mice lacking mBD-1 (KO), the homologue to hBD-1, following intranasal infection with 300 PFU. The survival plots were different at P = 0.027. (B) Comparison of percent body-weight loss in WT mice versus KO following infection; *P ≤ 0.05. (C) Representative micrographs (Table 3) of WT and mBD-1(−/−) mice infected with mouse-adapted HK18. Mice were infected with 300 PFU and killed 3 days after infection. Each panel represents a lung section from one mouse stained with H&E. A more severe inflammatory leukocytic infiltrate (neutrophils and mononuclear cells) and perivascular edema occurred at 3 h in the KO mice. Objective magnification is 10×. Total magnification is 100×.

Histopathology and virus titers in mBD-1(−/−) versus WT mice

Deletion of mBD-1 resulted in an earlier influx of inflammatory cells into the lung following influenza infection. Fig. 6C and Table 3 show that a greater number of inflammatory cells, perivascular edema, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage were present in the KO mice on Day 3 compared with WT mice. On Day 6, this difference was less apparent, suggesting that mBD-1 is important early in infection. However, when virus titers were compared between KO and WT mice 24 h following infection, no differences were detected. C57BL/6 WT mice (n=4) had 4.12 × 104 ± 1.43 × 104 PFU/g lung tissue compared with mBD-1(−/−) mice (n=4), which had 3.24 × 104 ± 1.17 × 104.

Table 3. Scoring of Histopathology of WT C57BL/6 and mBD-1(−/−) Mouse Lung Sections.

| Mouse # | Inflammatory cells | Perivascular edema | Hemorrhage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | |||

| WT1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| WT2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| WT3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| KO1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| KO2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| KO3 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Day 6 | |||

| WT1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| WT2 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| WT3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| KO1 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| KO2 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| KO3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

Sections were scored blindly by determining the number of inflammatory cells, perivascular edema, and hemorrhage/surface area, A diffuse alveolar infiltrate with perivascular edema and hemorrhage was seen more in the mBD-1(−/−) mice at Day 3.

DISCUSSION

Innate immunity against viruses involves numerous cell types, including DCs, monocytes, and NK cells, along with soluble mediators such as IFNs and other cytokines. PDC are thought to play a pivotal role in viral host defense via the production of large amounts of IFN-α [46–48] and chemokines such as CCL4 (MIP-1β) and CXCL10 (IP-10) [49, 50], which augment the Th1 response and recruit immune cells to the site of infection, respectively.

The importance of BD as a critical link between the innate and adaptive immune responses and not merely antibiotic peptides has been suggested by several key studies. First, the transfection of cells with the chemokine receptor, CCR6, which was shown to bind hBD-1 and hBD-2, was followed by experiments using hBD-2 to demonstrate chemoattraction of memory T cells and MDDC [19]. Second, the fact that hBD can act as adjuvants when fused to nonimmunogenic tumor antigens [51] or the gp120 protein of HIV [52] suggests a possible role in influencing the adaptive immune response. Finally, the binding of mBD-2b with TLR4, although a controversial study in that it implicates mBD-2b as an endogenous ligand for TLR4, suggests that BD activate innate immune signaling cascades that result in the release of proinflammatory cytokines, which ultimately influence adaptive immunity [53].

Our results uniquely demonstrate that enveloped RNA and DNA viruses, namely influenza, Sendai virus, and HSV-1, induce hBD-1 peptide and mRNA in PDC and monocytes, which are important cells of the immune system. Furthermore, our results also demonstrate that these viruses are capable of inducing only hBD-1 in these cells. hBD-1 is unlike the other hBD, which can be induced in epithelial cells by LPS and proinflammatory cytokines [54], suggesting different pathways for stimulation of BD. PDC are a specialized DC subpopulation that produces up to 10 pg/cell IFN-α, as well as lesser amounts of TNF and the chemokines CXCL10 (IP-10), CCL5 (RANTES), and CCL3 (MIP-1α), in response to viral stimulation [50] (for review, see refs. [48, 55]).

The inhibition of hBD-1 expression observed in epithelial cells in response to viral challenge stands in direct contrast to the stimulation observed in PDC in our study as well as the observation by others that viral infection leads to an induction of hBD-1 homologues by influenza and parainfluenza virus in vivo [22, 23]. However, the hBD-1 analysis in these latter studies was performed at times 24 h or greater, agreeing with our results with influenza at 18 h. This suggests that the initial suppression of hBD-1 mRNA by influenza and HSV-1 may be an immediate response, which may be at the level of mRNA degradation rather than an inhibition of transcription. The fact that neither inactive virus nor CpG DNA suppressed hBD-1 expression suggests that a viral factor specifically targets the peptide-based defense mechanism found in the target cells for the respective virus. A generalized HSV-1 shut-off of protein synthesis is not the reason for the decrease in hBD-1, as preliminary data in our laboratory showed that hBD-3 is not reduced following HSV-1 infection (unpublished data not shown).

We have observed a similar suppression of BD expression in airway epithelial cells by a virulence factor from the airway bacterial pathogen Bordetella bronchiseptica [56], leading to an increased susceptibility to infection. Additional evidence comes from a study reporting that early in Shigella infections, hBD-1 is reduced or turned off [57]. The study implicated Shigella plasmid DNA as one mediator that down-regulated hBD-1 and LL-37 and suggested that suppression of these peptides, a cathelicidin, might promote adherence and invasion of the bacterium into the host epithelial cell. This supports the role of hBD-1 in viral defense and suggests a mechanism for viral pathogenesis in epithelial tissue. Furthermore, the suppression of hBD-1, which also exhibits broad-spectrum antibiotic activity, suggests a mechanism for the opportunistic bacterial infections seen in the airway in patients with influenza infections [58, 59]. It also supports the association between HSV-1 infections observed in patients with chronic and aggressive periodontitis (reviewed in ref. [60]). Although the longer-term results differed between airway and gingival cells, this is not surprising in light of the differences between their responses seen in numerous studies (reviewed in ref. [61]).

The variation among hBD-1 responses among individuals in the experiments using blood cells could be a result of higher hBD-1 basal levels observed in some of the mock-infected samples, leaving little difference between virus-stimulated hBD-1 and hBD-1, which is produced from fresh or from a mock, 2-h infection. Others have observed that epithelial cell hBD-1 levels vary between normal and immunocompromised individuals [62]. However, in our experiments, the epithelial cells were from a single source (NHBE and OKF6/TERT cells), so great variability in hBD-1 mRNA levels was not observed. The variability in PDC and monocyte responses may be a result of genetic polymorphisms in the hBD-1 locus. These polymorphisms have been associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [63] and Candida carriage [64] and in children and adults with HIV [65, 66]. Normal volunteers could have had a subclinical viral infection when PBMCs were isolated, thus increasing the hBD-1 levels in mock control PBMC.

Although the significance of the virus-induced hBD-1 increase in these immune cells remains to be elucidated, two studies using viral plaque inhibition assays describe the direct antiviral activity of α-defensins, reporting an IC50 of 0.5–24 μM for HIV [14] and for HSV [11]. Although these concentrations might not be reached by secretion of the defensins into the circulation and tissues, they may certainly be achieved intracellularly or sequestered in the endosomal compartment or in the PDC microenvironment and thus, may act in an intracellular-defensive capacity to immediately protect the cell until sufficient levels of IFN-α can be translated.

If hBD-1 is secreted in a human viral infection, another likely role for hBD-1 production by these cells is to chemoattract and induce migration of mature MDC to the infection site, as much lesser amounts appear to be required to chemoattract cells than to kill viruses. Either function would provide an important role in innate immunity against viruses. Further studies to determine other biological functions using human cells, such as chemoattraction of MDDC and memory T-lymphocytes, are underway.

There is other evidence that hBD-1 may not be sequestered in the cell for the purpose of preventing viral infection. In a sheep animal model of parainfluenza type 3 infection, sheep BD-1 mRNA was increased in lung homogenates 3, 6, and 17 days following infection. The increased expression coincided with increases in surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D as well as decreased viral replication, but the precise role for sheep BD-1 in viral clearance and the source of this hBD-1 homologue were unclear [22]. hBD-1 was found in BAL from normal volunteers and in patients with inflammatory lung diseases [67]. PDC and other cells may be recruited to the lung, producing hBD-1 along with IFN-α in response to viruses. In humans, other sources would include alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells [8, 67].

Mice lacking the homologue for hBD-1, mBD-1 [68, 69], had an early, rapid body-weight loss and a swifter time to death (by 2 days) and had more deaths than the WT mice, despite showing similar levels of replication. In addition, the inflammatory cell infiltrate, edema, and hemorrhage were more marked in the mBD-1(−/−) mice compared with WT. The results in mice are indicative that BD-1 has other biological functions besides acting as an intracellular defense against viruses and plays a role in protecting against the pathogenesis of influenza by modulating proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, or other defensins and through altering the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lung. Further studies in mBD-1(−/−) mice that are underway will help elucidate the biological role of hBD-1 in innate immunity against influenza and whether mBD-1 plays a role in adaptive immunity as well.

The results of this study describe unique observations of hBD-1 gene expression changes by the virus in cells of the innate immune system and represent initial studies about hBD-1. Taken together, the results of the experiments in this study indicate that hBD-1 is not just a constitutively produced BD with weaker antimicrobial activity than the other hBD but is induced by viruses in cells of the innate immune system. hBD-1 is differentially regulated in epithelial cells compared with PDC and monocytes, suggesting pleiotropic effects, which depend on the cell type. Finally, hBD-1 appears to be biologically relevant, playing a protective role in the pathogenesis of influenza through mechanisms yet to be discovered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by NIH Public Health Service grants R01 AI26806 (P.F-B.), DE14897 and HL67871 (G.D.), and AI26806-07S1, R21AI072245, and R03ES016851 (L.K.R.) and the UMDNJ Foundation (L.K.R. and G.D.). The authors thank Dr. Alex Izaguirre for providing the initial RNA from fresh and HSV-stimulated PBMCs, Danielle Laube for performing initial PCR experiments, Divesh Mistry for performing some mouse experiments, Sarah Breakstone and Sung Ernest Lee for the monocyte and plaque assays, and Dr. Tina Cocuzza for performing initial antiviral assays.

Footnotes

- ΔMFI

- difference in geometric mean fluorescence intensity

- Δ(ΔMFI)

- difference in difference in geometric mean fluorescence intensity

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- BD

- β-defensin

- BDCA

- blood DC antigen

- G6PD

- glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase

- hBD

- human β-defensin(s)

- HBSS–

- HBSS without Ca++ and Mg++

- HK18

- influenza A/Hong Kong/1968/passage #18 h H3N2 in mouse lung homogenate (2.4×105/ml)

- HSV

- Herpes simplex virus

- IP-10

- IFN-inducible protein 10

- KO

- knockout

- mBD-1

- mouse β-defensin-1

- mBD-1(–/–)

- mouse β-defensin-1 gene deleted

- MDC

- myeloid DC(s)

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- MDDC

- monocyte-derived DC(s)

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

- NHBE

- normal human bronchial epithelial

- OKF

- human oral keratinocytes of the normal floor of the mouth

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PDC

- plasmacytoid DC(s)

- poly I:C

- polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- PR8

- influenza virus A, PR8 strain (H1N1; 1×106 PFU/μl)

- QR

- quantum red

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- UMDNJ

- University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

AUTHORSHIP

L.K.R. was the lead investigator on this grant, designing all experiments and performing initial PDC and monocyte purification, RT-PCR experiments, and in vivo studies; developing the flow cytometry methods for detecting hBD-1; managing the project and statistics; and writing the manuscript. P.F-B. provided guidance for the in vitro studies with HSV-1, influenza, and Sendai virus in PDC and monocytes and revised the manuscript. J.D., Z.Y., N.M., and V.U. developed and performed methods for obtaining purified PDC and qRT-PCR. G.D. guided the studies on BD in epithelial cells and all molecular biology methods, analyzed the qRT-PCR data, and revised the manuscript. K.D.S., S.Y. and J.M.A. performed the studies with the epithelial cells and provided input on design of the experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1. Diamond G., Bevins C. L. (1998) β-Defensins: endogenous antibiotics of the innate host defense response. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 88, 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehrer R. I., Ganz T. (2002) Defensins of vertebrate animals. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin E., Ganz T., Lehrer R. I. (1995) Defensins and other endogenous peptide antibiotics of vertebrates. J. Leukoc. Biol. 58, 128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kao C. Y., Chen Y., Zhao Y. H., Wu R. (2003) ORFeome-based search of airway epithelial cell-specific novel human β-defensin genes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 29, 71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodríguez-Jiménez F. J., Krause A., Schulz S., Forssmann W. G., Conejo-Garcia J. R., Schreeb R., Motzkus D. (2003) Distribution of new human β-defensin genes clustered on chromosome 20 in functionally different segments of epididymis. Genomics 81, 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schutte B. C., Mitros J. P., Bartlett J. A., Walters J. D., Jia H. P., Welsh M. J., Casavant T. L., McCray P. B., Jr. (2002) Discovery of five conserved β-defensin gene clusters using a computational search strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2129–2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao C., Wang I., Lehrer R. I. (1996) Widespread expression of β-defensin hBD-1 in human secretory glands and epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 396, 319–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duits L. A., Ravensbergen B., Rademaker M., Hiemstra P. S., Nibbering P. H. (2002) Expression of β-defensin 1 and 2 mRNA by human monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunology 106, 517–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fang X. M., Shu Q., Chen Q. X., Book M., Sahl H. G., Hoeft A., Stuber F. (2003) Differential expression of α- and β-defensins in human peripheral blood. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 33, 82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan L. K., Diamond G., Amrute S., Feng Z., Weinberg A., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (2003) Detection of hBD1 peptide in peripheral blood mononuclear cell subpopulations by intracellular flow cytometry. Peptides 24, 1785–1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daher K. A., Selsted M. E., Lehrer R. I. (1986) Direct inactivation of viruses by human granulocyte defensins. J. Virol. 60, 1068–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakashima H., Yamamoto N., Masuda M., Fujii N. (1993) Defensins inhibit HIV replication in vitro. AIDS 7, 1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang T. L., Francois F., Mosoian A., Klotman M. E. (2003) CAF-mediated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 transcriptional inhibition is distinct from α-defensin-1 HIV inhibition. J. Virol. 77, 6777–6784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang L., Yu W., He T., Yu J., Caffrey R. E., Dalmasso E. A., Fu S., Pham T., Mei J., Ho J. J., Zhang W., Lopez P., Ho D. D. (2002) Contribution of human α-defensin 1, 2, and 3 to the anti-HIV-1 activity of CD8 antiviral factor. Science 298, 995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mackewicz C. E., Yuan J., Tran P., Diaz L., Mack E., Selsted M. E., Levy J. A. (2003) α-Defensins can have anti-HIV activity but are not CD8 cell anti-HIV factors. AIDS 17, F23–F32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bastian A., Schafer H. (2001) Human α-defensin 1 (HNP-1) inhibits adenoviral infection in vitro. Regul. Pept. 101, 157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Virella-Lowell I., Poirier A., Chesnut K. A., Brantly M., Flotte T. R. (2000) Inhibition of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) transduction by bronchial secretions from cystic fibrosis patients. Gene Ther. 7, 1783–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gropp R., Frye M., Wagner T. O., Bargon J. (1999) Epithelial defensins impair adenoviral infection: implication for adenovirus-mediated gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 10, 957–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang D., Chertov O., Bykovskaia S. N., Chen Q., Buffo M. J., Shogan J., Anderson M., Schroeder J. M., Wang J. M., Howard O. M., Oppenheim J. J. (1999) β-Defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science 286, 525–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. García J. R., Jaumann F., Schulz S., Krause A., Rodriguez-Jimenez J., Forssmann U., Adermann K., Kluver E., Vogelmeier C., Becker D., Hedrich R., Forssmann W. G., Bals R. (2001) Identification of a novel, multifunctional β-defensin (human β- defensin 3) with specific antimicrobial activity. Its interaction with plasma membranes of Xenopus oocytes and the induction of macrophage chemoattraction. Cell Tissue Res. 306, 257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. García J. R., Krause A., Schulz S., Rodrigues-Jimenez F. J., Kluver E., Adermann K., Forssmann U., Frimpong-Boateng A., Bals R., Forssmann W. G. (2001) Human β-defensin 4: a novel inducible peptide with a salt-sensitive spectrum of antimicrobial activity. FASEB J. 15, 1819–1821 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grubor B., Gallup J. M., Meyerholz D. K., Crouch E. C., Evans R. B., Brogden K. A., Lehmkuhl H. D., Ackermann M. R. (2004) Enhanced surfactant protein and defensin mRNA levels and reduced viral replication during parainfluenza virus type 3 pneumonia in neonatal lambs. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 11, 599–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chong K. T., Thangavel R. R., Tang X. (2008) Enhanced expression of murine β-defensins (MBD-1, -2,- 3, and -4) in upper and lower airway mucosa of influenza virus infected mice. Virology 380, 136–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duits L. A., Nibbering P. H., van Strijen E., Vos J. B., Mannesse-Lazeroms S. P., van Sterkenburg M. A., Hiemstra P. S. (2003) Rhinovirus increases human β-defensin-2 and -3 mRNA expression in cultured bronchial epithelial cells. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Proud D., Sanders S. P., Wiehler S. (2004) Human rhinovirus infection induces airway epithelial cell production of human β-defensin 2 both in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 172, 4637–4645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quiñones-Mateu M. E., Lederman M. M., Feng Z., Chakraborty B., Weber J., Rangel H. R., Marotta M. L., Mirza M., Jiang B., Kiser P., Medvik K., Sieg S. F., Weinberg A. (2003) Human epithelial β-defensins 2 and 3 inhibit HIV-1 replication. AIDS 17, F39–F48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chong K. T., Xiang L., Wang X., Jun E. L., Xi L. F., Schweinfurth J. M. (2006) High level expression of human epithelial β-defensins (hBD-1, 2 and 3) in papillomavirus induced lesions. Virol. J. 3, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milone M. C., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (1998) The mannose receptor mediates induction of IFN-α in peripheral blood dendritic cells by enveloped RNA and DNA viruses. J. Immunol. 161, 2391–2399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valore E. V., Park C. H., Quayle A. J., Wiles K. R., McCray P. B., Ganz T. (1998) Human β-defensin-1: an antimicrobial peptide of urogenital tissues. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1633–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. López C. B., Fernandez-Sesma A., Schulman J. L., Moran T. M. (2001) Myeloid dendritic cells stimulate both Th1 and Th2 immune responses depending on the nature of the antigen. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 21, 763–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burleson G. R., Lebrec H., Yang Y. G., Ibanes J. D., Pennington K. N., Birnbaum L. S. (1996) Effect of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) on influenza virus host resistance in mice. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 29, 40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ryan L. K., Copeland L. R., Daniels M. J., Costa E. R., Selgrade M. J. (2002) Proinflammatory and Th1 cytokine alterations following ultraviolet radiation enhancement of disease due to influenza infection in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 67, 88–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryan L. K., Neldon D. L., Bishop L. R., Gilmour M. I., Daniels M. J., Sailstad D. M., Selgrade M. J. (2000) Exposure to ultraviolet radiation enhances mortality and pathology associated with influenza virus infection in mice. Photochem. Photobiol. 72, 497–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suliman H. B., Ryan L. K., Bishop L., Folz R. J. (2001) Prevention of influenza-induced lung injury in mice overexpressing extracellular superoxide dismutase. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 280, L69–L78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foster T. P., Rybachuk G. V., Kousoulas K. G. (1998) Expression of the enhanced green fluorescent protein by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) as an in vitro or in vivo marker for virus entry and replication. J. Virol. Methods 75, 151–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fitzgerald P. A., von Wussow P., Lopez C. (1982) Role of interferon in natural kill of HSV-1-infected fibroblasts. J. Immunol. 129, 819–823 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moser C., Weiner D. J., Lysenko E., Bals R., Weiser J. N., Wilson J. M. (2002) β-Defensin 1 contributes to pulmonary innate immunity in mice. Infect. Immun. 70, 3068–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lehrer R. I., Rosenman M., Harwig S. S. L., Jackson R., Eisenhauer P. (1991) Ultrasensitive assays for endogenous antimicrobial polypeptides. J. Immunol. Methods 137, 167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dai J., Megjugorac N. J., Amrute S. B., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (2004) Regulation of IFN regulatory factor-7 and IFN-α production by enveloped virus and lipopolysaccharide in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 173, 1535–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Feucht E. C., DeSanti C. L., Weinberg A. (2003) Selective induction of human β-defensin mRNAs by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in primary and immortalized oral epithelial cells. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 18, 359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feldman S., Stein D., Amrute S., Denny T., Garcia Z., Kloser P., Sun Y., Megjugorac N., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (2001) Decreased interferon-α production in HIV-infected patients correlates with numerical and functional deficiencies in circulating type 2 dendritic cell precursors. Clin. Immunol. 101, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Megjugorac N. J., Jacobs E. S., Izaguirre A. G., George T. C., Gupta G., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (2007) Image-based study of interferongenic interactions between plasmacytoid dendritic cells and HSV-infected monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunol. Invest. 36, 739–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fujiwara T., Oda K., Yokota S., Takatsuki A., Ikehara Y. (1988) Brefeldin A causes disassembly of the Golgi complex and accumulation of secretory proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 18545–18552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sørensen O. E., Thapa D. R., Rosenthal A., Liu L., Roberts A. A., Ganz T. (2005) Differential regulation of β-defensin expression in human skin by microbial stimuli. J. Immunol. 174, 4870–4879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lehrer R. I., Daher K., Ganz T., Selsted M. E. (1985) Direct inactivation of viruses by MCP-1 and MCP-2, natural peptide antibiotics from rabbit leukocytes. J. Virol. 54, 467–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Siegal F. P., Kadowaki N., Shodell M., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. A., Shah K., Ho S., Antonenko S., Liu Y. J. (1999) The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science 284, 1835–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cella M., Jarrossay D., Facchetti F., Alebardi O., Nakajima H., Lanzavecchia A., Colonna M. (1999) Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nat. Med. 5, 919–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P., Dai J., Singh S. (2008) Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and type I IFN: 50 years of convergent history. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 19, 3–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Penna G., Vulcano M., Roncari A., Facchetti F., Sozzani S., Adorini L. (2002) Cutting edge: differential chemokine production by myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 169, 6673–6676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Megjugorac N. J., Young H. A., Amrute S. B., Olshalsky S. L., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (2004) Virally stimulated plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce chemokines and induce migration of T and NK cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 504–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Biragyn A., Surenhu M., Yang D., Ruffini P. A., Haines B. A., Klyushnenkova E., Oppenheim J. J., Kwak L. W. (2001) Mediators of innate immunity that target immature, but not mature, dendritic cells induce antitumor immunity when genetically fused with nonimmunogenic tumor antigens. J. Immunol. 167, 6644–6653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Biragyn A., Belyakov I. M., Chow Y. H., Dimitrov D. S., Berzofsky J. A., Kwak L. W. (2002) DNA vaccines encoding human immunodeficiency virus-1 glycoprotein 120 fusions with proinflammatory chemoattractants induce systemic and mucosal immune responses. Blood 100, 1153–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Biragyn A., Ruffini P. A., Leifer C. A., Klyushnenkova E., Shakhov A., Chertov O., Shirakawa A. K., Farber J. M., Segal D. M., Oppenheim J. J., Kwak L. W. (2002) Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of dendritic cells by β-defensin 2. Science 298, 1025–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaiser V., Diamond G. (2000) Expression of mammalian defensin genes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68, 779–784 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. (2002) Natural interferon-α producing cells, the plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Biotechniques Oct. (Suppl.), 16–20, 22, 24–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Legarda D., Klein-Patel M. E., Yim S., Yuk M. H., Diamond G. (2005) Suppression of NF-κB-mediated β-defensin gene expression in the mammalian airway by the Bordetella type III secretion system. Cell. Microbiol. 7, 489–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Islam D., Bandholtz L., Nilsson J., Wigzell H., Christensson B., Agerberth B., Gudmundsson G. (2001) Downregulation of bactericidal peptides in enteric infections: a novel immune escape mechanism with bacterial DNA as a potential regulator. Nat. Med. 7, 180–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Finelli L., Fiore A., Dhara R., Brammer L., Shay D. K., Kamimoto L., Fry A., Hageman J., Gorwitz R., Bresee J., Uyeki T. (2008) Influenza-associated pediatric mortality in the United States: increase of Staphylococcus aureus coinfection. Pediatrics 122, 805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rothberg M. B., Haessler S. D., Brown R. B. (2008) Complications of viral influenza. Am. J. Med. 121, 258–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Slots J. (2005) Herpesviruses in periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 2000 38, 33–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Diamond G., Beckloff N., Ryan L. K. (2008) Host defense peptides in the oral cavity and the lung: similarities and differences. J. Dent. Res. 87, 915–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Krisanaprakornkit S., Weinberg A., Perez C. N., Dale B. A. (1998) Expression of the peptide antibiotic human β-defensin 1 in cultured gingival epithelial cells and gingival tissue. Infect. Immun. 66, 4222–4228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Matsushita I., Hasegawa K., Nakata K., Yasuda K., Tokunaga K., Keicho N. (2002) Genetic variants of human β-defensin-1 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291, 17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jurevic R. J., Bai M., Chadwick R. B., White T. C., Dale B. A. (2003) Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in human β-defensin 1: high-throughput SNP assays and association with Candida carriage in type I diabetics and nondiabetic controls. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 90–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Braida L., Boniotto M., Pontillo A., Tovo P. A., Amoroso A., Crovella S. (2004) A single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human β-defensin 1 gene is associated with HIV-1 infection in Italian children. AIDS 18, 1598–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zapata W., Rodriguez B., Weber J., Estrada H., Quinones-Mateu M. E., Zimermman P. A., Lederman M. M., Rugeles M. T. (2008) Increased levels of human β-defensins mRNA in sexually HIV-1 exposed but uninfected individuals. Curr. HIV Res. 6, 531–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Singh P. K., Jia H. P., Wiles K., Hesselberth J., Liu L., Conway B. A., Greenberg E. P., Valore E. V., Welsh M. J., Ganz T., Tack B. F., McCray P. B., Jr. (1998) Production of β-defensins by human airway epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14961–14966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Huttner K. M., Kozak C. A., Bevins C. L. (1997) The mouse genome encodes a single homolog of the antimicrobial peptide human β-defensin 1. FEBS Lett. 413, 45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Morrison G. M., Davidson D. J., Kilanowski F. M., Borthwick D. W., Crook K., Maxwell A. I., Govan J. R. W., Dorin J. R. (1998) Mouse β defensin-1 is a functional homolog of human β defensin-1. Mamm. Genome 9, 453–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]