Nuclear-localized PLSCR1 allows extra amplification divisions of granulocytic precursors during G-CSF-induced neutrophil development.

Keywords: PLSCR1, emergency granulopoiesis, cell cycle, mitosis, nuclear trafficking

Abstract

PLSCR1−/− mice exhibit normal, steady-state hematologic parameters but impaired emergency granulopoiesis upon in vivo administration of G-CSF. The mechanism by which PLSCR1 contributes to G-CSF-induced neutrophil production is largely unknown. We now report that the expansion of bone marrow myelocytes upon in vivo G-CSF treatment is reduced in PLSCR1−/− mice relative to WT. Using SCF-ER-Hoxb8-immortalized myeloid progenitors to examine the progression of G-CSF-driven granulocytic differentiation in vitro, we found that PLSCR1 prolongs the period of mitotic expansion of proliferative granulocyte precursors, thereby giving rise to increased neutrophil production from their progenitors. This effect of PLSCR1 is blocked by a ΔNLS-PLSCR1, which prevents its nuclear import. By contrast, mutation that prevents the membrane association of PLSCR1 has minimal impact on the role of PLSCR1 in G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis. These data imply that the capacity of PLSCR1 to augment G-CSF-dependent production of mature neutrophils from myeloid progenitors is unrelated to its reported activities at the endofacial surface of the plasma membrane but does require entry of the protein into the nucleus, suggesting that this response is mediated through the observed effects of PLSCR1 on gene transcription.

Introduction

Neutrophil-mediated innate immunity is an integral part of the host defense system. The number of circulating neutrophils is tightly controlled to achieve a delicate balance between immune defense and inflammation or immunosuppression. This is primarily achieved by the continuous production of granulocytes and storage of mature neutrophils in the bone marrow and the release of mature neutrophils from the bone marrow into blood, as required for homeostasis [1, 2]. G-CSF has been established as the key cytokine-promoting granulopoiesis [3–6]. It regulates the production of myeloid lineage-committed progenitors, the proliferation and differentiation of granulocytic precursor cells, and the survival of postmitotic bone marrow neutrophils [7–11]. Serum levels of G-CSF can be up-regulated in response to infectious stress, stimulating neutrophil production in the bone marrow and release of neutrophils into the peripheral blood [12]. G-CSF is also widely used clinically to stimulate neutrophil production [13–15]. This G-CSF-induced “emergency granulopoiesis” is the result of accelerated cell cycle progression of granulocyte precursors and release of mature neutrophils from the bone marrow, relative to basal conditions [16, 17].

PLSCR1−/− mice exhibit temporary neutropenia around the time of birth, a period of rapid granulopoiesis [18]. Whereas steady-state peripheral neutrophil counts are normal in the adult animal, attenuated granulopoiesis is also observed when adult PLSCR1−/− mice are injected with a therapeutic dose of G-CSF. Colony-forming assays of the bone marrow cells of adult mice reveal decreased colony numbers and size of PLSCR1−/− hematopoietic progenitors (compared with WT) when cultured in G-CSF but not other hematopoietic cytokines, including GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-7, thrombopoietin, or erythropoietin. Granulocytic differentiation of bone marrow cells stimulated by G-CSF is also accompanied by an increase in PLSCR1 expression. These previous data imply that PLSCR1 participates in the response of hematopoietic progenitors to G-CSF and up-regulates the production of neutrophils from these precursors. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which PLSCR1 enhances granulopoiesis is poorly understood.

PLSCR1 was identified originally as an endofacial plasma membrane protein that mediates calcium-dependent, bidirectional movement of phospholipids [19–22]. Subsequent studies revealed that PLSCR1 also participates in kinase signaling pathways initiated through the activation of cell surface receptors, including the EGF and IgE receptors [23–26]. In addition to its putative functions at the plasma membrane, PLSCR1 has been shown to traffic into the nucleus in response to IFN or when membrane association was prevented by inhibiting its palmitoylation, resulting in transcriptional activation of target genes [27–31]. The existence of PLSCR1 in different subcellular compartments raises the question as to the relative role of membrane-associated versus nuclear-localized PLSCR1 in the observed enhancement of granulopoiesis. Also unresolved is whether the contribution of PLSCR1 to increased granulopoiesis reflects enhanced proliferation of neutrophil progenitors and/or facilitated differentiation of these progenitors to mature neutrophils. In this report, we investigated the effect of PLSCR1 on G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation in mouse bone marrow and immortalized neutrophil progenitors. Our data indicate that PLSCR1 prolongs the period of mitotic expansion of bone marrow myelocytes, leading to an increase in number of mature blood neutrophils, and that this enhanced granulopoiesis is mediated by nuclear-localized PLSCR1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The generation of PLSCR1−/− mice has been described previously [18]. All experiments reported here were performed using mice and cells derived from the inbred 129/SvEvBrd strain. Mice were sex- and age-matched (8–12 weeks) in all experiments. The experimental protocols were approved by the University of Rochester Committee on Animal Resources (Rochester, NY, USA).

Administration of G-CSF and BrdU to mice

Human rG-CSF (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), diluted in PBS with 0.1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered by s.c. injection into WT (n=5) and PLSCR1−/− mice (n=5) at a dose of 120 μg/kg/12 h for 3 days [8]. Immediately after the last G-CSF injection, each mouse was injected i.p. with 0.1 ml BrdU solution (10 mg/ml; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). One hour later, peripheral blood samples were collected through retro-orbital bleeding, and then bone marrow cells were harvested from the femora of these mice and suspended in “basic medium” composed of OptiMEM (Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Life Technologies), and 30 μM β-ME (Sigma-Aldrich).

In vitro granulocytic differentiation of SCF-ER-Hoxb8 myeloid progenitor cells

SCF-ER-Hoxb8, immortalized myeloid progenitor cells derived from WT and PLSCR1−/− mice, were established, as described previously by Kamps and colleagues [32]. The immortalized cells were maintained as promyelocyte-like cells in “progenitor outgrowth medium” composed of basic medium supplemented with 1 μM β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% conditioned medium from a murine SCF-producing cell line (CHO-mast cell growth factor/SCF; kindly provided by Dr. Mark Kamps, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA). To induce granulocytic differentiation of SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells, cells were washed twice with basic medium and then suspended in basic medium supplemented with 2 ng/ml murine G-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml. Total cell count of the cultures was measured by a Z1 Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and total live cell counts were calculated from the percentage of live cells assessed by exclusion of DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich), analyzed using an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Retroviral expression of WT and mutant PLSCR1

For granulopoiesis analysis, the cDNA of mouse WT PLSCR1 (193CCFPCC198 and 266GKISKQWSGF275), ΔPal-PLSCR1 (193AAFPAA198) [28], and ΔNLS-PLSCR1 (266GAISAAWSGF275) [29] was cloned into pMIG retroviral vector [31]. For confocal microscopy and ImageStream analyses, the cDNA of YFP-PLSCR1 and YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1 fusion constructs was cloned into pMSCVpuro retroviral vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The immortalized PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were single cell cloned and transduced with the retroviral supernatants as described previously [32]. Cells were cultured further for several passages (∼3 weeks) in progenitor outgrowth medium (or progenitor outgrowth medium containing 2 μg/ml puromycin for the cells infected with pMSCVpuro constructs), and the stably transduced cells expressing equivalent amounts of fluorescent protein (GFP or YFP) were isolated by FACS using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow-nucleated cells were obtained by treating each bone marrow sample with RBC lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) and then washed once with PBS containing 2% FBS (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). To determine myelocyte and granulocyte populations, cells were stained with antibodies against Mac1 (PE-conjugated clone M1/70) and GR1 (PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated clone RB6-8C5) [33]. To analyze the cell cycle status, cell incorporation of BrdU was determined using an APC BrdU flow kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. To characterize the bone marrow myeloid progenitors, cells were incubated with biotinylated antibodies against Lin (including CD5, CD11b, CD19, CD45R, Ly-6G, Ter119, and 7-4; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), c-kit (PE-Cy7-conjugated clone 2B8), Sca-1 (FITC-conjugated clone D7), CD34 (Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated clone RAM34; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), and FcγR (PE-conjugated clone 2.4G2) [34, 35]. Bound, biotinylated antibodies were detected with PerCP-streptavidin. Dead cells were excluded from analysis by staining with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were analyzed using an LSR-II flow cytometer and FACSDiva or FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA) software. All reagents and instrument/software were from BD Biosciences unless noted otherwise.

Differential cell counts

Smears of peripheral blood and cytospins of bone marrow and in vitro-differentiated cells were stained with Wright-Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich), and manual differential counts of at least 200 nucleated cells were performed. ANC of peripheral blood was derived by multiplying the total white blood cell count times the percentage of neutrophils (including Seg. N. and Band N.) in the differential cell count. For in vitro granulocytic differentiation, data from differential cell counts were combined with the total live cell counts of each sample, and the absolute number of each cell type was presented.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblot was performed as described previously [18]. Briefly, cell lysates were resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane, which was blocked and incubated with mouse mAb against GFP (0.4 μg/ml; clone JL-8; Clontech) and mouse PLSCR1 (1 μg/ml; clone 1A8) [31] and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against C/EBPα (1 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and actin (0.1 μg/ml; Sigma-Alrich), respectively. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG (each 1:50,000 dilution; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and bound antibodies were detected by SuperSignal chemiluminesence substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and exposure to X-ray film.

qPCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted from PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), and reverse transcription was performed using AMV RT (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The levels of a subset of stage-specific myeloid gene transcripts were measured by qPCR using qPCR Mastermix Plus (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). The following primers were used: 5-GGCCCTAGACCTGCTGAAGA-3 and 5-GTCACCCCCACGTCCTATA-3 for MPO; 5-AGGGTTTCTGGTGCGAGAAG-3 and 5-GTTCTGCGGATTGTAATCAGGAT-3 for CTSG; 5-AGCCCCGGACTCACTACTATG-3 and 5-AGGTATGGACGAAGTGTCCCT-3 for LF; 5-TGCCCACTCTGCCTTTCTAAT-3 and 5-CTGCACCTTGAGATTGGTCCT-3 for CD177; 5-CGGACAGGATTGACAGATTG-3 and 5-CAAATCGCTCCACCAACTAA-3 for 18S rRNA. All reactions were performed on an iCycler and MyiQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative level of each transcript normalized to 18S rRNA is presented.

CellTrace Violet cell division analysis

PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells (106 cells/ml in PBS) were labeled with 6 μM CellTrace Violet dye (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) for 15 min and then washed with 10 vol progenitor outgrowth medium. The stained cells were cultured further in progenitor outgrowth medium at 5 × 105 cells/ml for 24 h and then subjected to FACS using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) to isolate cells labeled with equivalent amounts of CellTrace Violet dye. Granulocytic differentiation of the CellTrace Violet dye-labeled cells was induced by G-CSF, as described previously. At the indicated times, the intensity of the CellTrace Violet dye was analyzed using an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the populations of the cells that had undergone zero to 10 divisions were calculated by FlowJo curve-fitting software (Tree Star).

Confocal microscopy and ImageStream analyses

Granulocytic differentiation of the SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells expressing YFP-PLSCR1 and YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1 fusion constructs was induced by G-CSF as described above. At the indicated times, cells were fixed by para-formaldehyde solution (4% in PBS; USB Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA) for 5 min and then permeabilized with Triton X-100 solution (0.2% in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min. For confocal microscopy analysis, cell nuclei were stained with 5 μM DRAQ5 (Biostatus Ltd., Leicestershire, UK). The samples were mounted on glass slides by SHUR/MOUNT (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC, USA) and examined using a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) at ×1000 original magnification (objective: Fluar 100×/1.3 oil UV; pinhole size: 100; scanning thickness: 0.5 μm). The YFP signal was excited by a 488-nm laser and detected using a BP505-600 filter. The DRAQ5 signal was excited by a 633-nm laser and detected using a LP650 filter. For multispectral imaging flow cytometeric analysis, the nuclei of the cells were stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10,000 events of each sample were recorded using an ImageStream instrument (Amnis Corp., Seattle, WA, USA). Single color-labeled cells were used to compensate fluorescence between YFP and DAPI channel images, and the data were analyzed by IDEAS4.0 image analysis software (Amnis Corp.). The SV is defined as the degree of correlation between YFP-PLSCR1 and DAPI images of each cell based on the log-transformed Pearson's correlation coefficient using the similarity feature of the software. The cell region is defined by a bright-field image mask that fits the membrane of the cells.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± sem. Statistical comparisons were made using two-tailed paired and unpaired Student′s t tests. P < 0.05 (*) was considered significant.

RESULTS

Reduced myelocyte population in PLSCR1−/− mice in response to in vivo G-CSF treatment

Previous studies have shown that PLSCR1−/− mice exhibit normal, steady-state hematologic parameters but impaired neutrophil production upon in vivo administration of G-CSF, a condition mimicking emergency granulopoiesis [18]. To further investigate the primary impact of PLSCR1 on the progression of granulopoiesis, age- and sex-matched WT and PLSCR1−/− mice were injected with rG-CSF for 3 days, and ANCs of peripheral blood and differential counts of bone marrow cells were performed (Table 1). As reported previously, the basal level of neutrophils in peripheral blood was normal in untreated PLSCR1−/− mice, whereas in response to G-CSF, the increase of blood neutrophils was attenuated in PLSCR1−/− mice compared with WT [18]. Differential counts of bone marrow revealed no significant differences between untreated WT and PLSCR1−/− mice. By contrast, in G-CSF-treated animals, the percentage of bone marrow myelocytes in PLSCR1−/− mice was reduced significantly compared with WT (10.9±1.1% vs. 15.6±1.5%; P<0.05). These data suggested that the impaired emergency granulopoiesis in PLSCR1−/− mice was associated with an attenuated increase of the myelocyte population in response to G-CSF.

Table 1. Altered Bone Marrow Hematopoietic Cell Populations in PLSCR1–/– Mice in Response to in vivo G-CSF Administration.

| Group | Genotype | Blood ANC (103/uL) | Bone marrow-nucleated cell type (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blasts | Promyelocytes | Myelocytes | Band N. | Seg. N. | Lymphocytes | Erythrocytes | Othersa | |||

| Untreated | WT | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 12.0 ± 2.1 | 35.6 ± 1.2 | 17.9 ± 1.5 | 14.7 ± 1.4 | 9.4 ± 0.4 |

| PLSCR1–/– | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 0.6 | 34.7 ± 2.5 | 19.0 ± 2.3 | 16.1 ± 2.5 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | |

| G-CSF | WT | 44.6 ± 2.5 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 0.8 | 15.6 ± 1.5 | 29.5 ± 1.6 | 29.0 ± 2.2 | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| PLSCR1–/– | 35.3 ± 2.3b | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.1b | 29.8 ± 1.4 | 33.1 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | |

Data represent mean ± sem. Untreated, n = 4 mice; G-CSF-treated, n = 5 mice.

Includes monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and megakaryocytes.

P < .05 compared with WT in the same group.

Analysis of in vivo BrdU incorporation in PLSCR1−/− mice

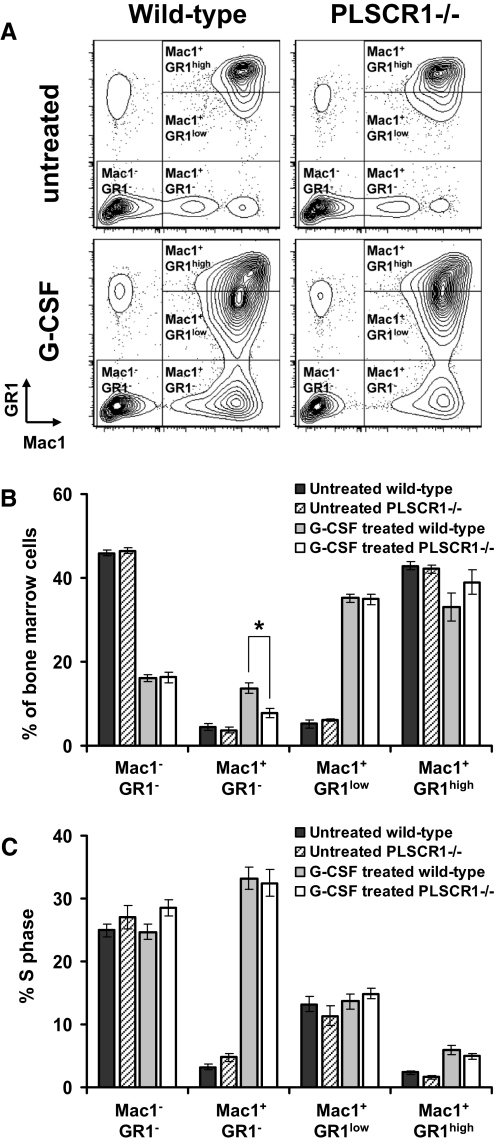

To further understand the origin of the attenuated response to in vivo administration of G-CSF observed in PLSCR1−/− mice, we next measured the incorporation of BrdU into bone marrow cells under these conditions. To analyze the percentage of cells in S-phase at different stages of granulocytic differentiation, the myeloid lineage cells were subdivided into Mac1+/GR1– myelocytes, Mac1+/GR1low immature granulocytes, and Mac1+/GR1high mature granulocytes (Fig. 1A) [33]. Consistent with the differential count results shown in Table 1, the percentage of the Mac1+/GR1– myelocyte population was reduced in G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/− versus WT mice (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 1C, G-CSF treatment potently increased the incorporation of BrdU in the Mac1+/GR1– myelocyte population. Nevertheless, no change in the percentage of cells in S-phase was detected between WT and PLSCR1−/− mice in this cell population. Moreover, no significant differences in terms of the size of the population and the percentage of cells in S-phase were observed in Mac1–/GR1–, Mac1+/GR1low, and Mac1+/GR1high populations between WT and PLSCR1−/− mice. These data suggested that the reduced number of myelocytes observed in G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/− mice could not be attributed to a change in the percentage of bone marrow cells in S-phase in response to G-CSF.

Figure 1. Cell cycle analysis of mouse bone marrow cells in response to in vivo G-CSF treatment.

Administration of G-CSF and BrdU to mice was detailed in Materials and Methods. Bone marrow cells collected 1 h after BrdU injection were stained with anti-Mac1, anti-GR1, and anti-BrdU antibodies. (A) Representative Mac1/GR1 flow cytometric profiles of bone marrow cells from untreated and G-CSF-treated WT and PLSCR1−/− mice. (B) Percentage of Mac1–/GR1–, Mac1+/GR1–, Mac1+/GR1low, and Mac1+/GR1high cells in total bone marrow cells. (C) Analysis of percentage cells in S-phase assessed by BrdU incorporation. Data represent mean ± sem of untreated WT (black bars; n=4), untreated PLSCR1−/− (hatched bars; n=4), G-CSF-treated WT (gray bars; n=5), and G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/− (white bars; n=5) mice. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

Analysis of myeloid precursor populations in PLSCR1−/− mice

The preceding results raised the possibility that the differences in the bone marrow myelocyte population between G-CSF-treated WT and PLSCR1−/− mice may be a result of differences in the relative number of specific myeloid precursor cells. To examine this possibility, Lin–/Sca-1–/c-kit+ bone marrow myeloid precursors were subdivided into CMP (CD34+/FcγRlow), GMP (CD34+/low/ FcγR+), and MEP (CD34low/–/FcγRlow/–; Fig. 2A) [34, 35]. As shown in Fig. 2B and 2C, no significant differences were observed between WT and PLSCR1−/− mice in the numbers of CMP, GMP, and MEP before or after G-CSF treatment. This suggested that the reduced number of myelocytes observed in G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/− mice could not be attributed to a change in myeloid progenitor cell populations.

Figure 2. Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow myeloid progenitor populations in response to in vivo G-CSF treatment.

Administration of G-CSF to mice and staining of bone marrow samples were detailed in Materials and Methods. Lin–/Sca-1–/c-kit+ cells were pre-gated from total bone marrow cells and further divided into CD34+/FcγRlow (CMP), CD34+/low/ FcγR+ (GMP), and CD34low/–/FcγRlow/– (MEP). (A) Representative CD34/FcγR flow cytometric profiles of the bone marrow samples from untreated and G-CSF-treated WT and PLSCR1−/− mice. (B) Percentage of CMP, GMP, and MEP derived from flow cytometric analysis, as depicted in A. (C) Absolute numbers of CMP, GMP, and MEP harvested from each mouse were calculated by multiplying the total number of nucleated cells obtained from each mouse (untreated WT, 2.26±0.55×107; untreated PLSCR1−/−, 2.20±0.42×107; G-CSF-treated WT, 2.54±0.56×107; G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/−, 2.74±0.65×107) by the percentage of CMP, GMP, and MEP (from B). Data represent mean ± sem of untreated WT (black bars; n=4), untreated PLSCR1−/− (hatched bars; n=4), G-CSF-treated WT (gray bars; n=5), and G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/− (white bars; n=5) mice.

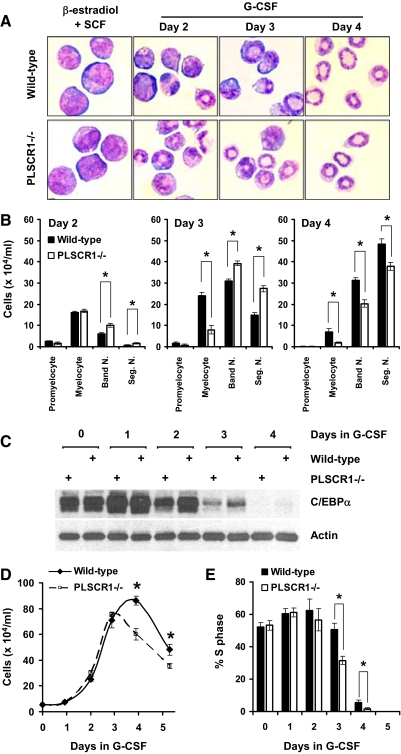

Altered response of PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 myeloid progenitors to G-CSF

To characterize more precisely the impact of PLSCR1−/− on the progression of G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation from pre-committed myeloid progenitors, we used SCF-ER-Hoxb8 conditionally immortalized bone marrow cells as first described by Kamps and colleagues [32]. As shown in Fig. 3A, SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells derived from WT and PLSCR1−/− mice were maintained at the promyelocyte-like stage by the presence of β-estradiol and SCF in the medium. Under this condition, we observed no differences in the immortalization efficiency or the rate of cell growth between WT and PLSCR1−/−. Upon substitution of β-estradiol and SCF with G-CSF, WT and PLSCR1−/− cells underwent differentiation through morphologically identifiable myelocyte- and Band N.-like stages (Days 2 and 3). These cells became fully differentiated within 4 days to Seg. N.-like cells, as indicated by the low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and highly condensed chromatin.

Figure 3. G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis of SCF-ER-Hoxb8 myeloid progenitors.

WT and PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were cultured in the presence of G-CSF at a seeding concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml. (A) WT (upper panel) and PLSCR1−/− (lower panel) SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells cultured in progenitor outgrowth medium (β-estradiol+SCF) and in basic medium supplemented with 2 ng/ml G-CSF (Days 2–4) were transferred to glass slides by cytospin and stained with Wright-Giemsa solution. Slides were examined at ×400 original magnification. (B) At the indicated times, the number of promyelocytes, myelocytes, Band N., and Seg. N. in WT (black bars) and PLSCR1−/− (white bars) cultures was determined by differential cell counts, as detailed in Materials and Methods. (C) Cell lysates of WT and PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells cultured in G-CSF were analyzed by Western blotting for C/EBPα (42 kDa) and actin. (D) Total live cell counts of WT (solid line) and PLSCR1−/− (dashed line) SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells cultured in G-CSF for up to 5 days. (E) At the indicated times, cells were incubated with 10 μM BrdU at 37°C for 40 min, and the incorporated BrdU was detected by anti-BrdU antibody. The percentage of cells in S-phase of the cell cycle (BrdU+ cells) in WT (black bars) and PLSCR1−/− (white bars) cultures was determined by flow cytometry. Data represent mean ± sem of five independently immortalized SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cell lines, each from WT and PLSCR1−/− mouse bone marrow. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

To compare G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis of WT versus PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells, we analyzed the number of cells at each stage of maturation by differential cell count from Day 2 to Day 4 in G-CSF. As shown in Fig. 3B, the maximum number of mature Seg. N. was lower in the PLSCR1−/− culture as compared with WT at Day 4 after G-CSF treatment. This result was consistent with the attenuated G-CSF-induced emergency granulopoiesis, as observed previously in PLSCR1−/− mice. Additionally, the PLSCR1−/− culture contained a reduced number of myelocytes compared with WT on Days 3 and 4 in G-CSF. This was similar to the observed phenomenon in the bone marrow of G-CSF-treated PLSCR1−/− mice (Table 1). Consistent with the morphological evaluation shown in Fig. 3B, the level of C/EBPα, a granulopoietic transcription factor predominantly expressed in promyelocytes and myelocytes [36–38], was reduced in PLSCR1−/− versus WT on Days 2 and 3 following induction of granulopoiesis by culture in G-CSF (Fig. 3C). These results suggested that PLSCR1−/− in myeloid progenitors altered the progression of cellular maturation during G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation.

In addition to the changed progression of granulocytic maturation observed in G-CSF-stimulated PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells, total cell counts shown in Fig. 3D revealed that the number of PLSCR1−/− cells ceased to expand after 3 days in G-CSF. By contrast, the WT cells continued to expand until Day 4 in G-CSF. As a result of this temporal shift in the peak of the culture, the maximum cell count was reduced in PLSCR1−/− (75.5±1.7×104/ml on Day 3) as compared with the WT culture (86.2±3.3×104/ml on Day 4; P<0.05). To further investigate the cause of this temporal shift and attenuated expansion of PLSCR1−/− cells in G-CSF, we next examined the incorporation of BrdU in differentiating SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cultures. As shown in Fig. 3E, the percentage of cells in S-phase in WT and PLSCR1−/− cultures decreased dramatically after 3 days in G-CSF. WT and PLSCR1−/− cells accumulated at G1/0-phase after 4 days of differentiation (data not shown). This phenomenon mirrored the morphological maturation of these cells toward terminally differentiated neutrophils, as shown in Fig. 3A. Notably, the percentage of cells in S-phase was lower in the PLSCR1−/− compared with WT culture at Days 3 and 4 after G-CSF treatment. At these time-points, a reduced number of myelocytes were also observed in PLSCR1−/− compared with WT culture (Fig. 3B). Together, our data derived from SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells suggested that the attenuated capacity of PLSCR1−/− progenitors to produce neutrophils was a result of reduced mitotic expansion of the PLSCR1−/− myelocyte population during G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation.

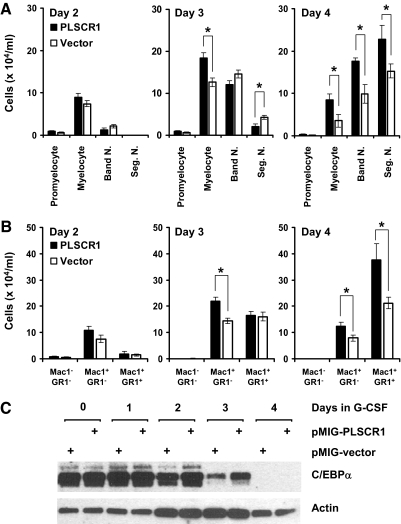

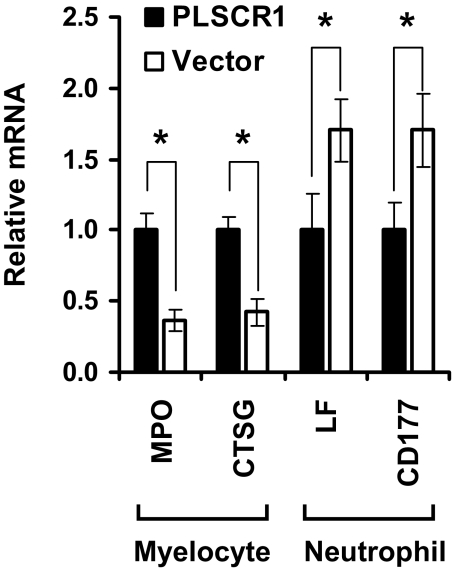

Ectopic expression of PLSCR1 promotes neutrophil production from SCF-ER-Hoxb8 progenitors

To corroborate that the altered G-CSF response observed in PLSCR1−/− myeloid progenitors was directly attributable to the absence of PLSCR1 protein in these cells, we used pMIG retroviral transduction to establish PLSCR1 protein expression in a clonal cell line of the PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 5A, differential cell counts revealed an increased number of myelocytes in the culture of PLSCR1-expressing cells compared with vector-infected cells on Days 3 and 4 after G-CSF stimulation. Expression of PLSCR1 also increased the maximum number of mature Seg. N. served at Day 4, compared with vector-infected cells. These data recapitulated the results shown in Fig. 3B, comparing WT and PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells. Consistent with the morphological evaluation shown in Fig. 5A, flow cytometric analysis shown in Fig. 5B revealed that ectopic expression of PLSCR1 resulted in an increased number of Mac1+/GR1– myelocytes on Days 3 and 4 and enhanced maximum production of Mac1+/GR1+ granulocytes on Day 4 in G-CSF. Of note, C/EBPα expression was elevated in PLSCR1-expressing versus vector-infected cells on Days 2 and 3 in G-CSF (Fig. 5C), consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3C, comparing WT and PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells. Additionally, we used qPCR to verify the altered cell populations of G-CSF-treated, PLSCR1-expressing versus vector-infected cultures. As shown in Fig. 6, the myelocyte-specific genes MPO [39] and CTSG [40] were expressed at higher levels in the culture of PLSCR1-expressing cells compared with vector-infected cells at Day 3 in G-CSF. Conversely, the neutrophil-specific genes LF [41] and CD177 [42, 43] were more abundant in the culture of vector-infected cells. These data indicated that at Day 3 after G-CSF treatment, the culture of PLSCR1-expressing cells contained a higher proportion of myelocytes compared with the vector-infected cells. Taken together, our results suggested that ectopic expression of PLSCR1 in PLSCR1−/− myeloid progenitors reversed the altered granulocytic maturation in response to G-CSF, which is observed in the PLSCR1−/− cells.

Figure 4. Ectopic expression of PLSCR1 in PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 myeloid progenitors by retroviral transduction.

Clonal PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were transduced with PLSCR1-expressing and vector pMIG retrovirus, and cells expressing comparable amounts of GFP were isolated by FACS, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Cell lysates of WT, PLSCR1−/−, and virally transduced PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were analyzed by Western blotting for PLSCR1, GFP, and actin.

Figure 5. Effect of ectopically expressed PLSCR1 on neutrophil production from SCF-ER-Hoxb8 myeloid progenitors.

PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells (see Fig. 4) were cultured in the presence of G-CSF at a seeding concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml. (A) Cells were transferred to glass slides by cytospin and stained with Wright-Giemsa solution at the indicated times. The number of promyelocytes, myelocytes, Band N., and Seg. N. in the cultures of PLSCR1-expressing (black bars) and vector-infected (white bars) cells was determined by differential cell counts, as detailed in Materials and Methods. (B) Cells were harvested at the indicated times, stained with anti-Mac1 (PE) and anti-GR1 antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The total live cell count was obtained for each sample, and the absolute number of Mac1–/GR1–, Mac1+/GR1–, and Mac1+/GR1+ cells in the cultures of PLSCR1-expressing (black bars) and vector-infected (white bars) cells was calculated from their percentage of the total cell population derived by flow cytometry. (C) Cell lysates of PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected cells cultured in G-CSF were analyzed by Western blotting for C/EBPα (42 kDa) and actin. Data represent mean ± sem of three each independently infected PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected PLSCR1−/− cell lines. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

Figure 6. Analysis of the expression level of stage-specific myeloid genes.

PLSCR1-expressing (black bars) and vector-infected (white bars) PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were cultured in the presence of G-CSF for 3 days. The levels of MPO, CTSG, LF, and CD177 gene transcripts were determined by qPCR, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean ± sem of three each independently infected PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected PLSCR1−/− cell lines. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

Expression of PLSCR1 in myeloid progenitors prolonged the expansion of culture in G-CSF (Fig. 7A). As a result, the maximum cell count was increased significantly in the culture of PLSCR1-expressing cells (49.5±7.0×104/ml on Day 4) as compared with the vector-infected cells (32.2±3.5×104/ml on Day 3; P<0.05). This increased expansion of the PLSCR1-expressing culture was similar to the results shown in Fig. 3D, comparing WT and PLSCR1−/− cells. Furthermore, BrdU incorporation analysis, shown in Fig. 7B, revealed that the percentage of cells in S-phase was higher in the culture of PLSCR1-expressing cells compared with vector-infected cells at Days 3 and 4 after G-CSF treatment. This increase in mitotic index of PLSCR1-expressing cells was again consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3E comparing WT versus PLSCR1−/− cells. These results suggested that ectopic expression of PLSCR1 increased the capacity of SCF-ER-Hoxb8 progenitors to produce neutrophils in a manner similar to endogenously expressed PLSCR1 in WT cells.

Figure 7. Effect of PLSCR1 on the mitotic expansion of granulocyte precursors cultured in G-CSF.

PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were cultured in the presence of G-CSF at a seeding concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml. (A) Total live cell counts of PLSCR1-expressing (solid line) and vector-infected (dashed line) cells cultured in G-CSF for up to 5 days. (B) At the indicated times, cells were incubated with 10 μM BrdU at 37°C for 40 min, and the incorporated BrdU was detected by anti-BrdU antibody. The percentage of cells in S-phase of the cell cycle (BrdU+ cells) in the cultures of PLSCR1-expressing (black bars) and vector-infected (white bars) cells was determined by flow cytometry. Data represent mean ± sem of three each independently infected PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected PLSCR1−/− cell lines. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test. (C) Representative flow cytometric histogram plots of CellTrace Violet dye-labeled PLSCR1-expressing (left) and vector-infected (right) PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells cultured in G-CSF. The cells labeled with equivalent amounts of CellTrace Violet dye were isolated by FACS, and the fluorescence intensity of the cells before differentiation (black) and after culture in G-CSF for 1 day (red), 2 days (orange), 3 days (green), and 4 days (blue) is shown. The gray-filled histograms indicate the autofluorescence of SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells not labeled with CellTrace Violet dye. (D) Mean division number of CellTrace Violet dye-labeled PLSCR1-expressing and vector-infected SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells cultured in G-CSF was calculated by FlowJo curve-fitting software. Data represent mean ± sem of a triplicate experiment. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

To corroborate further that the augmented neutrophil production observed in the PLSCR1-expressing cell culture was directly attributable to an increase in cellular mitosis during G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis, we next analyzed the number of cell divisions using CellTrace Violet dye dilution. As shown in Fig. 7C and D, the mean division number was higher in the culture of PLSCR1-expressing cells (6.8±0.1 divisions) compared with vector-infected cells (6.2±0.1 divisions) after 4 days in G-CSF. Together, our results suggested that expression of PLSCR1 prolongs the phase of mitotic expansion and allows extra amplification divisions of the differentiating granulocytic precursors during G-CSF-induced neutrophil development.

Entry of PLSCR1 into the nucleus is required for the effect of PLSCR1 on G-CSF-induced neutrophil production

PLSCR1 is an intracellular plasma membrane-associated protein that was identified originally based on its putative ability to promote the transbilayer movement of membrane phospholipids [19–22]. It has also been shown to participate in kinase signaling pathways initiated through ligand activation of cell surface receptors [23–26, 44]. The association of PLSCR1 with the plasma membrane is mediated by its multiple palmitoyl acyl chains in thioester linkage with the protein's polycysteine motif (193CCFPCC198). ΔPal-PLSCR1 (193AAFPAA198) prevents anchorage of PLSCR1 to the cell membrane and promotes trafficking of PLSCR1 into the nucleus [28]. The nuclear-localized PLSCR1 binds to DNA in a nucleotide sequence-specific manner and is capable of activating targeted gene expression. A NLS has been identified in PLSCR1 (266GKISKQWSGF275), and ΔNLS-PLSCR1 (266GAISAAWSGF275) blocks the interaction of PLSCR1 with the nuclear chaperone importin-α and consequently, prevents nuclear entry of PLSCR1 [29, 30].

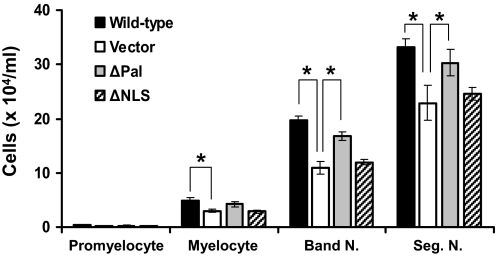

To elucidate the contribution of plasma membrane-bound versus nuclear-localized PLSCR1 in promoting G-CSF-induced neutrophil production, we expressed ΔPal-PLSCR1 and ΔNLS-PLSCR1 in a clonal cell line of PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells. As shown in Fig. 8, differential cell count on Day 4 after G-CSF treatment revealed that ΔNLS-PLSCR1 eliminated the capacity of PLSCR1 to increase the production of myelocytes, Band N., and Seg. N. from SCF-ER-Hoxb8 progenitors. By contrast, preventing palmitoylation of PLSCR1 had minimal impact on the function of PLSCR1 to promote granulopoiesis. These data suggested that the effect of PLSCR1 on enhancing G-CSF-induced production of neutrophils was unrelated to its reported activities at the plasma membrane but required importin-α-mediated entry of PLSCR1 into the nucleus.

Figure 8. Effect of mutant PLSCR1 on neutrophil production from SCF-ER-Hoxb8 myeloid progenitors.

Clonal PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells were transduced with WT PLSCR1, ΔPal-PLSCR1, ΔNLS-PLSCR1, and vector pMIG retrovirus, respectively. Cells expressing comparable amounts of GFP were isolated by FACS, as detailed in Materials and Methods, and then cultured in the presence of G-CSF at a seeding concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml for 4 days. The number of promyelocytes, myelocytes, Band N., and Seg. N. in each culture was determined by differential cell counts, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean ± sem of three experiments. *P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

Analysis of the subcellular distribution of PLSCR1 in granulocyte precursors during G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis

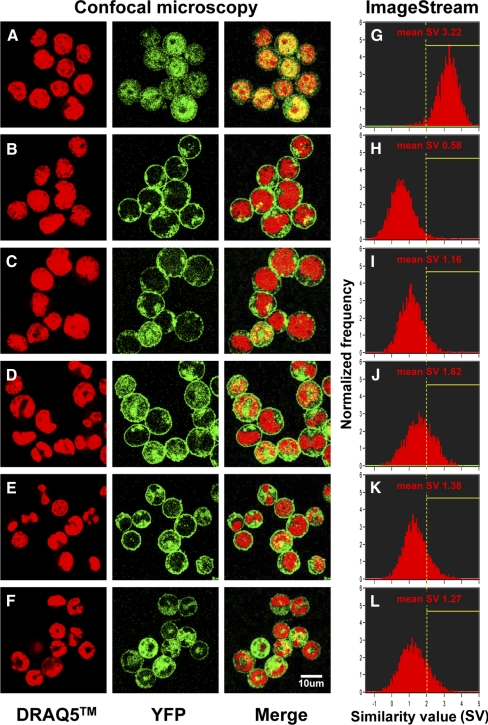

The preceding results raised the possibility that the effect of PLSCR1 on augmenting neutrophil production from myeloid progenitors requires the trafficking of PLSCR1 into the nucleus. To examine the subcellular localization of PLSCR1 in differentiating granulocyte precursors during G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis, we expressed YFP-PLSCR1 and YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1 (deleting sites of palmitoylation required for membrane anchoring) fusion constructs in a clonal cell line of PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells. Consistent with previous reports, confocal microscopy revealed that YFP-PLSCR1 is predominantly a plasma membrane-associated protein in SCF-ER-Hoxb8 progenitor cells (Fig. 9B), whereas YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1 (Fig. 9A) promoted the trafficking of the fusion protein into the nucleus [28]. Of note, an increased colocalization of noncell membrane-associated YFP-PLSCR1 with DRAQ5 nuclear stain was observed in differentiating SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells cultured in G-CSF-containing medium (Fig. 9C–F), as compared with the cells cultured in progenitor outgrowth medium (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9. Analysis of subcellular distribution of YFP-PLSCR1 in SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells under G-CSF stimulation.

Clonal PLSCR1−/− SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells expressing comparable amounts of YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1 (A and G) or YFP-PLSCR1 (B and H) fusion proteins were isolated by FACS, as detailed in Materials and Methods. The YFP-PLSCR1-expressing cells were further cultured in the presence of G-CSF for 1 day (C and I), 2 days (D and J), 3 days (E and K), and 4 days (F and L), respectively. For confocal microscopy analysis (A–F), the cell nuclei were stained with DRAQ5 dye, and the samples were examined for DRAQ5 (red), YFP-PLSCR1 (green), and merge images at ×1000 original magnification with 0.5 μm scanning thickness using a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL laser-scanning microscope. For ImageStream multispectral image flow cytometry analysis (G–L), the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. The SV between YFP-PLSCR1 and DAPI nuclear stain images of each single cell, as well as the mean SV of each sample, was analyzed using the similarity feature of IDEAS4.0 software.

To confirm and quantify the increased level of nuclear-localized PLSCR1 in differentiating granulocyte precursors by a high-throughput method, we then used ImageStream multispectral flow cytometry (Amnis Corp.) to analyze the correlation between YFP-PLSCR1 and DAPI nuclear stain images of 10,000 cells from each sample. Briefly, the ImageStream system is a combination of a flow cytometer and a fluorescence microscope that enables image-based analysis of large numbers of cells/sample. Using the similarity feature, each single cell was granted a SV, indicating the degree of correlation between YFP-PLSCR1 and DAPI stain images of the cell based on the log-transformed Pearson's correlation coefficient. As shown in the right panel of Fig. 9, cells expressing nuclear-trafficking form of PLSCR1 (YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1) exhibited a much higher SV of YFP-to-DAPI images (Fig. 9G; mean SV 3.22) than the cells expressing YFP-PLSCR1 (Fig. 9H; mean SV 0.58). Interestingly, a transient increase in mean SV of YFP-to-DAPI images was observed in YFP-PLSCR1 cells after G-CSF treatment (Fig. 9I–L), as compared with the cells cultured in progenitor outgrowth medium (Fig. 9H). The highest mean SV (1.62) of YFP-PLSCR1-expressing cells was recorded at Day 2 during G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation, mirroring the apparent maximal increase in nuclear-localized PLSCR1 in granulocyte precursors, as was independently observed when these cells were imaged directly by confocal microscopy (Fig. 9D).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that emergency granulopoiesis is impaired in PLSCR1−/− mice [18]. The mechanism underlying the contribution of this gene/protein to the development of the granulocytic lineage has not been elucidated previously. In the present study, we characterized the response of WT and PLSCR1−/− hematopoietic progenitors to G-CSF stimulation. Our results provide the first evidence that PLSCR1 prolongs the phase of mitotic expansion of granulocytic progenitors under the influence of G-CSF, thereby resulting in an increased production of terminally differentiated neutrophils.

Our results derived from in vivo G-CSF administration suggested that the impaired emergency granulopoiesis in PLSCR1−/− mice was associated with an attenuated expansion of the bone marrow myelocyte population in response to G-CSF (Table 1). However, interpretation of these data to identify the primary impact of PLSCR1 on granulocytic differentiation was limited by the heterogeneous and asynchronous nature of the hematopoietic precursors in bone marrow. Furthermore, complicated networks of cytokines/growth factors in vivo may also compensate for some of the defective response to G-CSF by providing alternative myelopoietic signals [45, 46]. Thus, an in vitro cellular model capable of responding to G-CSF and differentiating into mature neutrophils was required to further resolve how PLSCR1 contributes to G-CSF-driven granulopoiesis. As described by Kamps and associates [32], SCF-ER-Hoxb8 conditionally immortalized bone marrow cells can be maintained and expanded at a GMP-like stage in the presence of β-estradiol and SCF. Upon substitution of β-estradiol and SCF with G-CSF, these cells differentiate into Seg. N.-like cells that accumulate at the G1/0-phase of cell cycle, indicating their maturation toward terminally differentiated granulocytes. These characteristics of the SCF-ER-Hoxb8 progenitors enabled us to evaluate the function of PLSCR1 in the maturation of a uniform population of promyelocyte-like cells into terminally differentiated neutrophils. Furthermore, such cells can be derived from WT and PLSCR1−/− mouse bone marrow to examine the role of endogenous PLSCR1 in granulocytic differentiation and were also amenable to retroviral transduction so as to study the function of ectopically expressed WT versus mutant PLSCR1. Our results using SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells revealed that the average cell doubling time of WT SCF-ER-Hoxb8 culture (14.4±0.6 h) was indistinguishable from PLSCR1−/− (14.0±0.2 h) from Day 1 to Day 3 in G-CSF. Similarly, no difference was observed in the percentage of cells in S-phase from Day 0 to Day 2 of G-CSF-stimulated WT versus PLSCR1−/− cultures (Fig. 3E). These results are consistent with the in vivo BrdU cell cycle analysis of bone marrow showing comparable percentage of myeloid cells in S-phase between G-CSF-treated WT and PLSCR1−/− mice (Fig. 1C), suggesting that PLSCR1 does not enhance the rate of cell proliferation to increase total cell number.

Our analysis of the number of cell divisions (Fig. 7C and D) suggests that the contribution of PLSCR1 to G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis is to prolong the expansion of granulocytic progenitors under the influence of G-CSF. This allows the PLSCR1-expressing cells to undergo additional amplification divisions from Day 3 to Day 4 in G-CSF, resulting in an increased number of cells that will subsequently differentiate into mature neutrophils. Although our data revealed an approximate twofold dilution of dye intensity/cell division up to seven divisions after culture in G-CSF, we cannot rule out that the changes in cellular morphology, which occur during granulocytic differentiation, may additionally affect the cell-associated dye intensity. However, the results of cell division analysis derived from CellTrace Violet dye labeling are in agreement with the results of total cell count (Fig. 7A) and BrdU cell cycle analysis (Fig. 7B). All of these data indicated a similar rate of proliferation of PLSCR1-expressing versus vector-infected cell cultures up to 3 days under G-CSF treatment, whereas a significantly higher mitosis activity was observed in PLSCR1-expressing cell culture from Day 3 to Day 4 in G-CSF.

By contrast to the information we were able to obtain from the differentiation of promyelocyte-like cells to mature, neutrophil-like cells, SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells are less suitable to evaluate an effect of PLSCR1 on the G-CSF-induced differentiation of earlier myeloid progenitors, as these cells appear to be pre-committed at a GMP-like stage, favoring granulocytic lineage development [32]. Although we found no obvious abnormality in the population of CMP, GMP, and MEP in PLSCR1−/− mice at steady-state or during emergency granulopoiesis (Fig. 2), we cannot rule out the possibility that PLSCR1 may also affect the lineage commitment of GMP to granulocytic or monocytic lineages. However, this is less likely, as there was not a significant increase in the monocyte/macrophage lineage development in PLSCR1−/− mice or cells (data not shown).

In addition to its effects on lineage commitment and cell proliferation, G-CSF is known to sustain the survival of granulocytic cells, which also contributes to the elevated number of circulating neutrophils resulting from emergency granulopoiesis [6, 11]. This raises the question of whether PLSCR1 might contribute to G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis by also prolonging cell survival. However, we detected no significant changes in the viability of Mac1+/GR1–, Mac1+/GR1low, and Mac1+/GR1high cells in bone marrow of G-CSF-treated WT versus PLSCR1−/− mice (viability as assessed by exclusion of DAPI exceeded 98% in all myeloid populations; data not shown). Similarly, TUNEL assays of the differentiating SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells revealed a low and comparable percentage of apoptotic cells for WT and PLSCR1−/− culture up to 3 days in G-CSF (<5%; data not shown). These data suggest that the effect of PLSCR1 on G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis is not related to a change in the rate of apoptosis of myeloid populations but derives specifically from its capacity to prolong the phase of mitotic expansion of myelocytes and potentially other granulocyte precursors.

PLSCR1 is predominantly an endofacial plasma membrane-tethered protein that has been shown to have the potential to alter signaling through cell surface growth factor receptors [23–26]. In the case of the cellular response to G-CSF, however, our data suggest that ΔPal-PLSCR1 [28], so as to prevent protein trafficking to the plasma membrane, is equally effective as WT PLSCR1 to promote G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis (Fig. 8). This suggests that any activity of PLSCR1 observed at the plasma membrane is not required for the function of this protein to augment G-CSF-driven neutrophil production from myeloid progenitors. By contrast, ΔNLS-PLSCR1 [29, 30], which prevents PLSCR1 entry into the nucleus, blocks the effect of PLSCR1 on the hematopoietic response to G-CSF (Fig. 8). Additionally, using confocal microscopy and ImageStream multispectral image flow cytometry (Fig. 9), we discovered that the level of nuclear-localized PLSCR1 is increased in differentiating granulocyte precursors after G-CSF stimulation. A similar phenomenon of increased, nuclear-localized PLSCR1 was observed previously in the cellular response to α-IFN [28]. In that case, PLSCR1 was shown to potentiate the IFN-induced viral defense mechanisms through increasing the expression of a subset of IFN-stimulated genes [47]. These results imply that PLSCR1 may contribute to the cellular response to G-CSF through a nuclear effector pathway(s), potentially including its known role in regulating gene transcription [31].

In summary, the present study provides direct evidence that nuclear-localized PLSCR1 prolongs the phase of mitotic expansion and allows extra amplification divisions of the differentiating granulocytic precursors during G-CSF-induced neutrophil development. This adds to the functions described previously of PLSCR1 in promoting G-CSF-driven colony formation (in vitro) and emergency granulopoiesis (in vivo) [18]. Future studies to identify the target genes of nuclear PLSCR1 in neutrophil progenitors are necessary to further elucidate the mechanisms that underlie the regulatory activities of PLSCR1 in granulopoiesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL036946, HL063819, and HL076215. The authors acknowledge Dr. Mark Kamps (University of California, San Diego, CA, USA) for generously providing the materials and technical assistance for establishing SCF-ER-Hoxb8 cells from mouse bone marrow. We are most grateful to Dr. Quansheng Zhou (Soochow University, Suzhou, China) and Dr. Kathleen McGrath (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA) for helpful discussions. We also thank James Boyer for excellent technical assistance and maintaining the mouse colony.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 215

- ΔNLS-PLSCR1

- mutation in the nuclear localization signal motif of phospholipid scramblase 1

- ΔPal-PLSCR1

- mutation at sites of palmitoylation of phospholipid scramblase 1

- ANC

- absolute neutrophil count

- Band N.

- band neutrophils

- CMP

- common myeloid progenitors

- CTSG

- cathepsin G

- ER-Hoxb8

- ER-binding domain-Hoxb8 fusion protein

- GMP

- granulocytic/monocytic-restricted progenitors

- GRI

- lymphocyte antigen 6 G/C

- LF

- lactoferrin

- Lin

- lineage-specific antigens

- Mac1

- macrophage antigen 1

- MEP

- megakaryocytic/erythroid-restricted progenitors

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- MSCV

- murine stem cell virus

- NLS

- nuclear localization signaling

- PLSCR1

- phospholipid scramblase 1

- PLSCR1–/–

- PLSCR1-knockout

- pMIG

- p-murine stem cell virus-IRES-GFP

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- Sca-1

- lymphocyte antigen 6 A/E

- SCF

- stem cell factor

- Seg. N.

- segmented neutrophils

- SV

- similarity value

- YFP-ΔPal-PLSCR1

- YFP and mutation at sites of palmitoylation of phospholipid scramblase 1 fusion construct

- YFP-PLSCR1

- YFP and phospholipid scramblase 1 fusion construct

AUTHORSHIP

C-W.C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. M.S. and T.W. designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. Q.Z. initiated the project and contributed to preliminary experiments. P.J.S. supervised the project, designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. von Vietinghoff S., Ley K. (2008) Homeostatic regulation of blood neutrophil counts. J. Immunol. 181, 5183–5188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furze R. C., Rankin S. M. (2008) Neutrophil mobilization and clearance in the bone marrow. Immunology 125, 281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nicola N. A., Metcalf D., Matsumoto M., Johnson G. R. (1983) Purification of a factor inducing differentiation in murine myelomonocytic leukemia cells. Identification as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 9017–9023 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Souza L. M., Boone T. C., Gabrilove J., Lai P. H., Zsebo K. M., Murdock D. C., Chazin V. R., Bruszewski J., Lu H., Chen K. K., et al. (1986) Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: effects on normal and leukemic myeloid cells. Science 232, 61–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lieschke G. J., Grail D., Hodgson G., Metcalf D., Stanley E., Cheers C., Fowler K. J., Basu S., Zhan Y. F., Dunn A. R. (1994) Mice lacking granulocyte colony-stimulating factor have chronic neutropenia, granulocyte and macrophage progenitor cell deficiency, and impaired neutrophil mobilization. Blood 84, 1737–1746 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu F., Wu H. Y., Wesselschmidt R., Kornaga T., Link D. C. (1996) Impaired production and increased apoptosis of neutrophils in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor-deficient mice. Immunity 5, 491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lord B. I., Bronchud M. H., Owens S., Chang J., Howell A., Souza L., Dexter T. M. (1989) The kinetics of human granulopoiesis following treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 9499–9503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lord B. I., Molineux G., Pojda Z., Souza L. M., Mermod J. J., Dexter T. M. (1991) Myeloid cell kinetics in mice treated with recombinant interleukin-3, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (CSF), or granulocyte-macrophage CSF in vivo. Blood 77, 2154–2159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Basu S., Hodgson G., Katz M., Dunn A. R. (2002) Evaluation of role of G-CSF in the production, survival, and release of neutrophils from bone marrow into circulation. Blood 100, 854–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richards M. K., Liu F., Iwasaki H., Akashi K., Link D. C. (2003) Pivotal role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the development of progenitors in the common myeloid pathway. Blood 102, 3562–3568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Raam B. J., Drewniak A., Groenewold V., van den Berg T. K., Kuijpers T. W. (2008) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor delays neutrophil apoptosis by inhibition of calpains upstream of caspase-3. Blood 112, 2046–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kawakami M., Tsutsumi H., Kumakawa T., Abe H., Hirai M., Kurosawa S., Mori M., Fukushima M. (1990) Levels of serum granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with infections. Blood 76, 1962–1964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Welte K., Bonilla M. A., Gillio A. P., Boone T. C., Potter G. K., Gabrilove J. L., Moore M. A., O′Reilly R. J., Souza L. M. (1987) Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Effects on hematopoiesis in normal and cyclophosphamide-treated primates. J. Exp. Med. 165, 941–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morstyn G., Campbell L., Souza L. M., Alton N. K., Keech J., Green M., Sheridan W., Metcalf D., Fox R. (1988) Effect of granulocyte colony stimulating factor on neutropenia induced by cytotoxic chemotherapy. Lancet 1, 667–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gabrilove J. L., Jakubowski A., Scher H., Sternberg C., Wong G., Grous J., Yagoda A., Fain K., Moore M. A., Clarkson B., et al. (1988) Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on neutropenia and associated morbidity due to chemotherapy for transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium. N. Engl. J. Med. 318, 1414–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barreda D. R., Hanington P. C., Belosevic M. (2004) Regulation of myeloid development and function by colony stimulating factors. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 28, 509–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Panopoulos A. D., Watowich S. S. (2008) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: molecular mechanisms of action during steady state and “emergency” hematopoiesis. Cytokine 42, 277–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou Q., Zhao J., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (2002) Normal hemostasis but defective hematopoietic response to growth factors in mice deficient in phospholipid scramblase 1. Blood 99, 4030–4038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou Q., Zhao J., Stout J. G., Luhm R. A., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (1997) Molecular cloning of human plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase. A protein mediating transbilayer movement of plasma membrane phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18240–18244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou Q., Sims P. J., Wiedmer T. (1998) Identity of a conserved motif in phospholipid scramblase that is required for Ca2+-accelerated transbilayer movement of membrane phospholipids. Biochemistry 37, 2356–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao J., Zhou Q., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (1998) Level of expression of phospholipid scramblase regulates induced movement of phosphatidylserine to the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6603–6606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stout J. G., Zhou Q., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (1998) Change in conformation of plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase induced by occupancy of its Ca2+ binding site. Biochemistry 37, 14860–14866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun J., Nanjundan M., Pike L. J., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (2002) Plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase 1 is enriched in lipid rafts and interacts with the epidermal growth factor receptor. Biochemistry 41, 6338–6345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nanjundan M., Sun J., Zhao J., Zhou Q., Sims P. J., Wiedmer T. (2003) Plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase 1 promotes EGF-dependent activation of c-Src through the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37413–37418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pastorelli C., Veiga J., Charles N., Voignier E., Moussu H., Monteiro R. C., Benhamou M. (2001) IgE receptor type I-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipid scramblase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20407–20412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Amir-Moazami O., Alexia C., Charles N., Launay P., Monteiro R. C., Benhamou M. (2008) Phospholipid scramblase 1 modulates a selected set of IgE receptor-mediated mast cell responses through LAT-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25514–25523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhao J., Zhou Q., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (1998) Palmitoylation of phospholipid scramblase is required for normal function in promoting Ca2+-activated transbilayer movement of membrane phospholipids. Biochemistry 37, 6361–6366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wiedmer T., Zhao J., Nanjundan M., Sims P. J. (2003) Palmitoylation of phospholipid scramblase 1 controls its distribution between nucleus and plasma membrane. Biochemistry 42, 1227–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ben-Efraim I., Zhou Q., Wiedmer T., Gerace L., Sims P. J. (2004) Phospholipid scramblase 1 is imported into the nucleus by a receptor-mediated pathway and interacts with DNA. Biochemistry 43, 3518–3526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen M. H., Ben-Efraim I., Mitrousis G., Walker-Kopp N., Sims P. J., Cingolani G. (2005) Phospholipid scramblase 1 contains a nonclassical nuclear localization signal with unique binding site in importin α. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10599–10606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou Q., Ben-Efraim I., Bigcas J. L., Junqueira D., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (2005) Phospholipid scramblase 1 binds to the promoter region of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor type 1 gene to enhance its expression. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35062–35068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang G. G., Calvo K. R., Pasillas M. P., Sykes D. B., Hacker H., Kamps M. P. (2006) Quantitative production of macrophages or neutrophils ex vivo using conditional Hoxb8. Nat. Methods 3, 287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Panopoulos A. D., Zhang L., Snow J. W., Jones D. M., Smith A. M., El Kasmi K. C., Liu F., Goldsmith M. A., Link D. C., Murray P. J., Watowich S. S. (2006) STAT3 governs distinct pathways in emergency granulopoiesis and mature neutrophils. Blood 108, 3682–3690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Na Nakorn T., Traver D., Weissman I. L., Akashi K. (2002) Myeloerythroid-restricted progenitors are sufficient to confer radioprotection and provide the majority of day 8 CFU-S. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 1579–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huntly B. J., Shigematsu H., Deguchi K., Lee B. H., Mizuno S., Duclos N., Rowan R., Amaral S., Curley D., Williams I. R., Akashi K., Gilliland D. G. (2004) MOZ-TIF2, but not BCR-ABL, confers properties of leukemic stem cells to committed murine hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Cell 6, 587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang D. E., Zhang P., Wang N. D., Hetherington C. J., Darlington G. J., Tenen D. G. (1997) Absence of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor signaling and neutrophil development in CCAAT enhancer binding protein α-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 569–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Theilgaard-Mönch K., Jacobsen L. C., Borup R., Rasmussen T., Bjerregaard M. D., Nielsen F. C., Cowland J. B., Borregaard N. (2005) The transcriptional program of terminal granulocytic differentiation. Blood 105, 1785–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Orkin S. H., Zon L. I. (2008) Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell 132, 631–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iida S., Watanabe-Fukunaga R., Nagata S., Fukunaga R. (2008) Essential role of C/EBPα in G-CSF-induced transcriptional activation and chromatin modification of myeloid-specific genes. Genes Cells 13, 313–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lennartsson A., Garwicz D., Lindmark A., Gullberg U. (2005) The proximal promoter of the human cathepsin G gene conferring myeloid-specific expression includes C/EBP, c-myb and PU.1 binding sites. Gene 356, 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gombart A. F., Kwok S. H., Anderson K. L., Yamaguchi Y., Torbett B. E., Koeffler H. P. (2003) Regulation of neutrophil and eosinophil secondary granule gene expression by transcription factors C/EBP ε and PU.1. Blood 101, 3265–3273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sachs U. J., Andrei-Selmer C. L., Maniar A., Weiss T., Paddock C., Orlova V. V., Choi E. Y., Newman P. J., Preissner K. T., Chavakis T., Santoso S. (2007) The neutrophil-specific antigen CD177 is a counter-receptor for platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23603–23612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Buzzeo M. P., Yang J., Casella G., Reddy V. (2007) Hematopoietic stem cell mobilization with G-CSF induces innate inflammation yet suppresses adaptive immune gene expression as revealed by microarray analysis. Exp. Hematol. 35, 1456–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun J., Zhao J., Schwartz M. A., Wang J. Y., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J. (2001) c-Abl tyrosine kinase binds and phosphorylates phospholipid scramblase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28984–28990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu F., Poursine-Laurent J., Wu H. Y., Link D. C. (1997) Interleukin-6 and the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor are major independent regulators of granulopoiesis in vivo but are not required for lineage commitment or terminal differentiation. Blood 90, 2583–2590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Basu S., Hodgson G., Zhang H. H., Katz M., Quilici C., Dunn A. R. (2000) “Emergency” granulopoiesis in G-CSF-deficient mice in response to Candida albicans infection. Blood 95, 3725–3733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dong B., Zhou Q., Zhao J., Zhou A., Harty R. N., Bose S., Banerjee A., Slee R., Guenther J., Williams B. R., Wiedmer T., Sims P. J., Silverman R. H. (2004) Phospholipid scramblase 1 potentiates the antiviral activity of interferon. J. Virol. 78, 8983–8993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]