Removal of sialyl residues on β2 integrin and ICAM-1 by sialidase activity, mobilized during PMN activation, is an important regulator of leukocyte recruitment.

Keywords: β2 integrin, polymorphonuclear leukocyte, endothelial cell, leukocyte trafficking

Abstract

Diapedesis is a dynamic, highly regulated process by which leukocytes are recruited to inflammatory sites. We reported previously that removal of sialyl residues from PMNs enables these cells to become more adherent to EC monolayers and that sialidase activity within intracellular compartments of resting PMNs translocates to the plasma membrane following activation. We did not identify which surface adhesion molecules were targeted by endogenous sialidase. Upon activation, β2 integrin (CD11b/CD18) on the PMN surface undergoes conformational change, which allows it to bind more tightly to the ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 on the EC surface. Removal of sialyl residues from CD18 and CD11b, by exogenous neuraminidase or mobilization of PMN sialidase, unmasked activation epitopes, as detected by flow cytometry and enhanced binding to ICAM-1. One sialidase isoform, Neu1, colocalized with CD18 on confocal microscopy. Using an autoperfused microflow chamber, desialylation of immobilized ICAM-1 enhanced leukocyte arrest in vivo. Further, treatment with a sialidase inhibitor in vivo reversed endotoxin-induced binding of leukocytes to ICAM-1, thereby suggesting a role for leukocyte sialidase in the cellular arrest. These data suggest that PMN sialidase could be a physiologic source of the enzymatic activity that removes sialyl residues on β2 integrin and ICAM-1, resulting in their enhanced interaction. Thus, PMN sialidase may be an important regulator of the recruitment of these cells to inflamed sites.

Introduction

The post-translational modification of proteins enhances the structural and functional diversity of the cell. The glycosylation of proteins and lipids at the cell surface is an important determinant of cell-to-cell interactions and may protect these molecules from enzymatic degradation. Sialic acids are a family of amino sugars present on the surface of most eukaryotic cells. These highly negatively charged molecules are known to be important in T–B lymphocyte interactions, mask antigens on the surface of cells, regulate ligand–receptor interactions, and determine the lifespan of proteins and cells that are cleared by asialoreceptors [1–4]. Sialic acids also play a critical role in nerve cell development and in the metastatic potential of malignant cells [5, 6].

We reported previously that the sialidase activity within PMN secondary granules of resting cells translocates to the plasma membrane following activation [7]. This mobilized sialidase activity appeared to play a role in leukocyte trafficking and migration in vitro and in vivo [8, 9]. Stimulation of PMNs in vitro and in vivo enhanced PMN recruitment to inflamed sites via modulation of cell surface sialylation, presumably by promoting PMN adherence to and migration across ECs [9]. Blockade of PMN sialidase activity by pharmacologic inhibition or immune blockade inhibited their recruitment to inflamed sites in vivo; however, in those studies, we did not examine which of the adhesion molecules on the PMN or endothelial surface might be modified by sialidase activity.

The activation of the β2 integrin is a critical event in diapedesis. β2 integrins are heterodimeric receptors on the surface of myeloid cells that mediate adhesion to counterligands on other cells (e.g., ICAM-1 and -2 on ECs). The principal PMN β2 integrins are CD11a/CD18 (LFA-1) and CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1, CR3) [10, 11]. As PMNs circulate in the bloodstream, the integrins are in a nonactivated, low-affinity state by virtue of a bent conformation that renders the ligand-binding site inaccessible to potential ligands. Upon reaching a site of inflammation, the PMNs are activated, and the integrins undergo a conformational change, whereby the CD11b/CD18 molecule opens in an extended, “switch-blade”-like manner, exposing the ligand-binding site—the I domain on the α (CD11b) subunit, so that it can become a high-affinity receptor and bind to ICAM-1 or ICAM-2 on ECs [12–14]. Activation of the integrins increases the strength of binding between individual integrin molecules and its ligand (“affinity”) up to 10,000-fold [15]. Clustering of integrins on the plasma membrane via conformational changes and lateral redistribution increases the overall strength of binding (“avidity”) [11, 15].

Given the prominence of sialic acid residues on cell surface molecules and its importance in regulating cell-to-cell interactions necessary for diapedesis, we hypothesized that removal of sialyl residues on adhesion molecules expressed on ECs and PMNs may play an important role in the tight adhesion between these cells. We now report that removal of sialyl residues from β2 integrin and its binding partner ICAM-1 by exogenous neuraminidase or mobilization of endogenous sialidase enhances the interaction between PMNs and ECs in static and flow assays of PMN adhesion. Thus, the modulation of the sialylation status may be an additional mechanism by which the adhesive events mediated by these glycans are regulated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Purified and FITC-conjugated anti-CD18 antibody (clone L130) and PE-conjugated PSGL-1 antibody (clone KPL-1) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA); FITC-conjugated anti-CD18 activation epitope (clone MEM148) was purchased from AbD Serotec (Oxford, UK); purified anti-CD11b (clone ICRF44) and FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b activation epitope (clone CBRM1/5) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA); FITC-conjugated PNA was purchased from EY Laboratories (San Mateo, CA, USA); biotinylated SNA and MAA lectins were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA); 2-DN and wortmannin were purchased from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ, USA); LY294002 was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); PMA, 4-MUNANA, and NA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); and anti-ICAM-1, rsICAM-1, and ICAM-1-Fc fusion protein were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Anti-neu1 antibody was purchased from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA, USA), and anti-neu3 antibody was purchased from Strategic Diagnostics (Newark, DE, USA).

PMN isolation

PMNs were isolated from healthy volunteers as described previously [7] under a protocol approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Baltimore, MD, USA).

Flow cytometry

Isolated PMNs (1×106 /ml) were treated with NA (30 mU/ml), with or without 2-DN, PMA (100 ng/ml), or HBSS only (as negative control), at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of CMP (250 μg/ml) to inhibit resialylation by PMN sialyltransferase [16] and washed. In some experiments, cells were stimulated with fMLP (10−6 M; Sigma-Aldrich) and cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 37°C. The treated cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD18, anti-CD18 activation epitope, PNA, or anti-CD11b activation epitope and PE-conjugated PSGL-1 at 4°C for 30 min and analyzed on a MoFlow cytometer/cell sorter (Dako-Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO, USA).

ICAM-1-binding assays

To assess the ability of ICAM-1 to bind to activated CD18, a flow cytometric assay was used. ICAM-1-Fc fusion protein (25 μg/ml) or rhIgG1 Fc was incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-Fc antibodies (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA; 25 μg/ml) at 4°C overnight before use. The treated PMNs were stained with the above ICAM-1 or rhIgG1 complexes for 30 min at room temperature. In some experiments, cells were incubated with rsICAM-1 (100 μg/ml) for 10 min before adding the ICAM-1 complexes as a control for specificity. Cells were then washed two times and analyzed on a MoFlow cytomer/cell sorter.

Immunoprecipitation

Treated PMNs were lysed in RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) and precleared with anti-mouse IgG agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C overnight. The supernatant was incubated with 1 μg anti-CD18 antibody for 5 h, followed by overnight incubation with fresh anti-mouse IgG agarose. An isotype antibody control was added to exclude nonspecific pull-down. The binding proteins on agarose were washed five times with RIPA buffer and released in Laemmli buffer with 10 min of boiling for analysis. The same cell lysate was also immunoprecipitated with anti-CD11b antibody to confirm that CD11b was coimmunoprecipitated with the anti-CD18 antibody.

Western and lectin blots

The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels (4–15%; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBS and blotted with anti-CD11b antibody (1 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The membrane was developed with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent subtrate (Pierce).

For lectin blots, the membrane was blocked with 3% BSA (crystalline; Sigma-Aldrich) in TBS overnight. The sialylation of immunoprecipitated proteins on the membrane was determined by blotting with biotinylated SNA or MAAII, followed by streptavidin-HRP (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Fetuin and asialofetuin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as positive and negative lectin blot controls, respectively.

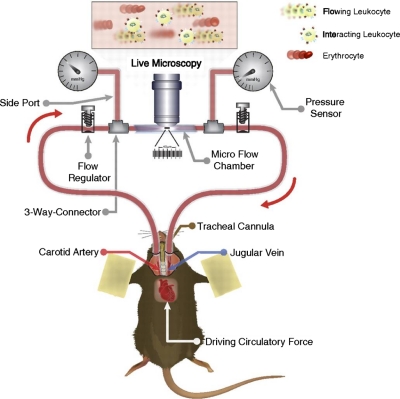

Autoperfused microflow chamber

The experimental procedures were described previously [17, 18] and shown in Fig. 1. Briefly, ICAM-1 and P-selectin (5 μg/ml; R&D Systems) were immobilized on heparinized microslides that were microsurgically connected to the carotid artery and the jugular vein of anesthetized mice. An upright microscope (Leica, Germany) was used for live microscopy.

Figure 1. Autoperfused microflow chamber assay.

Heparinized, translucent microchambers were double-coated with rmP-selectin (5 μg/ml) and ICAM-1 (5 μg/ml), the latter with or without NA treatment at 4°C overnight. Microchambers were connected to polyester tubing at both ends, which subsequently, at the time of experiment, were microsurgically connected to the right carotid artery and the left jugular vein of an anesthetized mouse, as described previously [17, 18]. One hour prior to connecting the chambers to the animal's blood flow, the chambers were incubated with 1% BSA to prevent nonspecific leukocyte interactions with the inner surfaces. Leukocyte number and rolling velocity were recorded and analyzed using the autoperfused microflow chamber assay [17, 18].

Fluorescence microscopy

PMNs were plated on chamber slides precoated with normal human serum for 2 h to allow adherent. The cells were stimulated with fMLP (10−6 M) and cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml) for 10 min or PMA (100 ng/ml) for 30 min and washed three times with HBSS and fixed in fresh-prepared, 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min. After another wash, the slides were incubated with anti-CD18 and anti-Neu1 or anti-Neu3 antibody overnight at 4°C. The next day, the slides were washed and incubated with Cy2-conjugated anti-mouse and Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (kindly provided by Dr. Adam Puche, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA). The slides were counterstained further with DAPI and mounted in mounting medium. The images were captured on an Olympus BX61 Fluoview laser-scanning microscope with a 60× objective and 2.5× or 8× digital amplification with Fluoview V5.0. The images from different channels were merged with Adobe Photoshop 4.0.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test in Microsoft Excel; P values <0.05 were considered as significantly different. For flow cytometry data, the MFI of each sample and its sd were obtained by Winlist (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA). The t values for Student's t test between two samples were calculated as: t = |MFI1 –MFI2|/SE, where SE = square root of (N1×sd12+N2sd22)/(N1+N22) × (1/N1+1/N2), and N1 and N2 are the cell numbers for each sample.

RESULTS

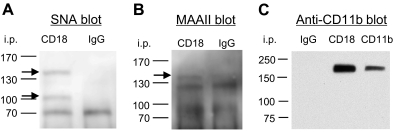

CD18 and CD11b are sialylated

Although it has been reported that LFA-1 and Mac-1 (β2 integrin) are sialylated [19, 20], to our knowledge, the specific linkage of such sialylation was unknown. Terminal sialic acid residues on glycoproteins can be detected by the SNA or MAAII lectins in a linkage-specific manner (α-2,6 and α-2,3, respectively) [21]. We immunoprecipitated PMN lysates with anti-CD18 antibody or isotype control and blotted with SNA or MAAII lectins. SNA recognized two anti-CD18-immunoprecipitated proteins at 105 KD and 165 KD, the corresponding sizes of CD18 and CD11b, respectively (Fig. 2A). MAAII recognized only the protein at 165 KD (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Sialylation of CD18 and CD11b.

Whole cell lysates from PMNs were immuniprecipitated with anti-CD18, CD11b, or control IgG, separated on a 4–15% SDS-PAGE gel, and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membranes were blotted with biotinylated SNA (A), MAAII (B), or purified anti-CD11b antibody (C).

CD11b is a glycoprotein associated with CD18 to form the β2-integrin heterodimer (also known as Mac-1, CR3). To determine if the 165-KD proteins detected by SNA and MAAII were CD11b, we blotted CD18 immunoprecipitate with anti-CD11b antibody. For comparison, we also included the sample from an immunoprecipitation using anti-CD11b antibody, which detected a single band at 165 kD, the same size as that detected by SNA and MAAII on CD18 and CD11b immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2B). These data confirm that CD18 and CD11b were immunoprecipitated by anti-CD18 antibody and sialylated: CD11b with α-2,6 and α-2,3 linkages but CD18 with only an α-2,6 linkage.

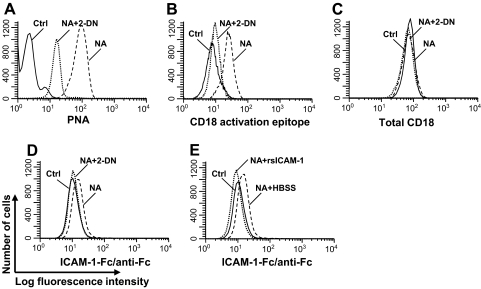

Desialylation of PMNs increased its CD18 activation epitope expression

To interact with ICAM-1, CD11b/CD18 must transform into the high-affinity form, which can be recognized specifically on the CD18 chain by the MEM148 antibody [22]. We hypothesized that the sialyl residues on the β2 integrin masked the activation epitope of CD18 and that removal of these sialic acid residues allows the heterodimer to change conformation and expose its activation epitope. Removal of terminal sialic acid from glycoconjugates exposes a subterminal galactose, which can be recognized by the lectin PNA [23]. NA treatment increased the binding of the PNA on PMN (Fig. 3A), indicative of loss of sialyl residues, and this PNA binding was inhibited by 2-DN. In experiments not shown, addition of 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid, a molecule with the same MW and charge as sialic acid, did not block NA-induced PNA expression, and boiled NA did not induce PNA binding. These data confirm that NA treatment desialylated glycoconjugates on PMNs.

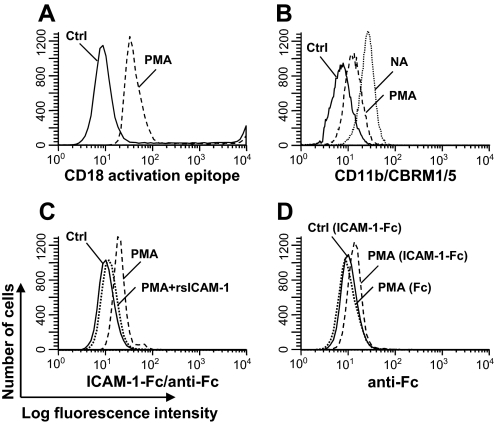

Figure 3. Desialylation increased the CD18 activation epitope expression and ICAM-1 binding on PMNs.

PMNs (1×106/ml) were treated with 30 mU/ml NA (dashed lines), NA plus 250 μg/ml 2-DN (dotted line), or no treatment (Ctrl; solid line) for 1 h and stained with FITC-conjugated PNA (A), anti-CD18 activation epitope (B), anti-CD18 (C), or ICAM-1-Fc plus FITC-labeled anti-Fc complex (D). NA-treated PMNs were preincubated with rsICAM-1 (dotted line) or HBSS (dashed line) before staining with ICAM-1-Fc plus FITC-labeled anti-Fc complex (E). Data shown are representative of data from at least four independent experiments using different donors each with similar results.

Using the mAb MEM148, which recognizes a hCD18 activation epitope, we studied the effect of desialylation on the expression of activated CD18 on the PMN cell surface. Compared with the untreated cells, the NA treatment increased the exposure of the CD18 activation epitope (MFI increased threefold, from 7.8 to 24.6; P<0.05), whereas 2-DN suppressed this increase (MFI: 9.7 vs. 24.6; P<0.05; Fig. 3B). NA treatment, however, did not change the overall expression level of total CD18 (Fig. 3C).

Exposure of the CD18 activation epitope after NA treatment enhances PMN binding to ICAM-1

If desialylation unmasked the CD18 activation epitope, we would expect increased ICAM-1 binding to the NA-treated PMNs. We therefore analyzed the binding of untreated or NA-treated PMNs to ICAM-1-Fc fusion protein/FITC-conjugated anti-Fc antibody complex by flow cytometry. Increased ICAM-1 binding on the NA-treated cells was observed compared with untreated cells (MFI: 14.9 vs. 10.8; P<0.05), and 2-DN treatment reduced such binding (MFI: 11.1 vs. 14.9; P<0.05; Fig. 3D). As an additional control, we repeated the experiment with cells pretreated with rsICAM-1 as a competitive inhibitor. In the presence of this inhibitor, the ICAM-1 binding to the PMNs was reduced (MFI: 9.3 vs. 14.9; P<0.05; Fig. 3E), consistent with the hypothesis that the rsICAM-1 bound to the PMNs, thereby blocking access of the fusion protein to the activated CD18 epitope.

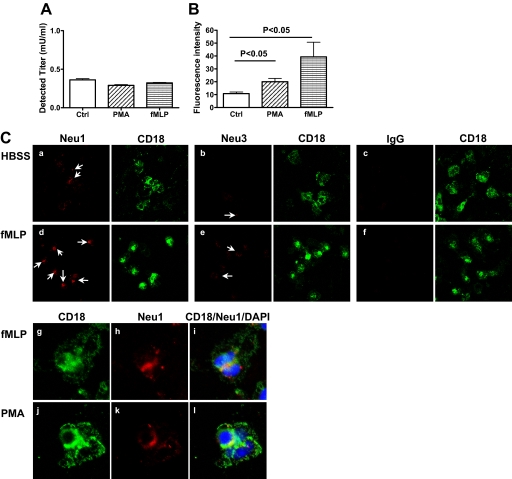

PMA stimulation translocated sialidase activity to the cell surface

Although treatment of PMNs with exogenous NA unmasked activation epitopes on CD18 and CD11b, which enhanced its binding to ICAM-1, it is not clear if such desialylation has any physiologic relevance or could occur in vivo. We previously reported that PMNs have endogenous sialidase activity, which upon activation, is translocated from compartments within the cell to the plasma membrane [7]. We therefore speculated that stimulation with a receptor-mediated agonist fMLP or a nonreceptor-mediated agonist PMA would mobilize the PMN sialidase activity to the plasma membrane, expose the activation epitope of CD11b/CD18, and facilitate its binding to ICAM-1, as we observed with exogenous NA treatment. Comparable sialidase activities were detected from total lysates of fMLP or PMA-stimulated and untreated cells (Fig. 4A), suggesting that PMNs have sialidase activity but no significant change in total sialidase activity after PMA stimulation. Assay for the sialidase activity on the cell surface using intact cells revealed that fMLP and PMA-treated cells demonstrated higher enzyme activity compared with that of untreated cells (39.3±19.7 and 20.0±4.5 vs. 10.8±2.1; P<0.05; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. PMA stimulation translocated sialidase activities to the PMN cell surface.

(A) Sialidase activity in whole cell lysates of PMNs was detected using 4-MUNANA as the substrate, as described previously [5]. (B) PMA-treated or untreated PMNs (5×106) were suspended in 200 μl HBSS with 0.5 mM 4-MUNANA and 250 mM CMP to inhibit sialyltransferase [16] on a 96-well plate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The fluorescence from the free 4-methylum-belliferone released by the enzyme into the supernatant was read. (C) Unstimulated (HBSS, a–c) or fMLP (10−6 M) plus cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml, d–i)- or PMA (100 ng/ml)-stimulated PMNs (j–l) on slides were stained with CD18 (green) and Neu1 (a, d, and g–l), Neu3 (b and e), or isotype IgG (c and f) antibodies (red) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). (a–f) Images with 60× objective and 2.5× digital amplification. Arrows indicate the Neu1- or Neu3-positive cells. (g–l) Cells were stained with the antibody to CD18 (g and j) and Neu1 (h and k), and the images merged (i and l; 60× objective and 8× digital amplification). Data shown are representative of data from at least three independent experiments using different donors, each with similar results.

Four sialidase isoforms have been identified in humans [24]. Among them, neu1 is reported to be the most abundant, and neu3 is important on the cell surface [24, 25]. We therefore examined whether expression of neu1 and neu3 on the PMN surface changed after stimulation using fluorescence microscopy. neu1 expression was detected on the PMN surface (Fig. 4C, a), which was further enhanced after fMLP stimulation (Fig. 4C, d) and colocalized with CD18 (Fig. 4C, g–i). In contrast, neu3 expression was scattered on untreated cells but only slightly increased after stimulation (Fig. 4C, b and e). PMA-induced neu1 expression also colocalized with CD18 (Fig. 4B, j–l). Thus, neu1 might be in sufficiently close proximity to the β2 integrin to remove sialyl residues from this adhesion molecule.

PMA stimulation enhanced CD18 activation epitope expression and ICAM-1 binding

Having shown that fMLP or PMA stimulation increased sialidase activity on the cell surface and translocated neu gene expression on the plasma membrane, we then examined whether the PMA-mobilized sialidase activity would expose the activation epitope of CD11b/CD18 and facilitate its binding to ICAM-1. PMA stimulation increased the expression of the CD18 activation epitope on the PMN surface (MFI from 9.7 to 39.2; P<0.05; Fig. 5A). Further, treatment of PMNs with NA or PMA similarly unmasked an activation epitope on CD11b, as revealed by binding of the CBRM1/5 mAb (MFI from 7.3 to 25.8 and 14.5, respectively; P<0.05; Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. PMA stimulation increased the CD18 activation epitope expression and ICAM-1 binding on PMNs.

(A) PMNs (1×106/ml) were stimulated with PMA (100 ng/ml; dashed line) or no treatment (solid line) for 1 h and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD18 activation epitope. (B) PMNs (1×106/ml) were stimulated with PMA (100 ng/ml; dashed line), NA (dotted line), or no treatment (solid line) for 1 h and stained with FITC-labeled anti-CD11b (CBRM1/5) antibody. (C and D) PMNs (1×106/ml) were stimulated with PMA (100 ng/ml; dashed lines) or no treatment (solid lines) for 1 h and stained with ICAM-1-Fc fusion protein plus a FITC-labeled anti-Fc complex. As a specificity control, (C) PMA-stimulated cells were preincubated with rsICAM-1 (100 μg/ml) before staining (dotted line), or (D) PMA-stimulated cells were stained with rhIgG1 Fc plus a FITC-labeled anti-Fc complex (dotted line). Data shown are representative of data from at least three independent experiments using different donors, each with similar results.

We then studied whether the increased expression of the CD18 activation epitope following PMA treatment corresponded to enhanced binding to ICAM-1. Compared with nonstimulated PMNs, there was increased ICAM-1 binding on PMA-treated cells (MFI from 10.8 to 19.8; P<0.05), which was inhibited with the pretreatment with rsICAM-1 (MFI: 12.4 vs. 19.8; P<0.05; Fig. 5C). Further, rhIgG1 Fc/FITC-conjugated anti-Fc antibody complex did not bind to PMA-activated PMNs as ICAM-1-Fc did (MFI: 9.7 vs. 10.8; P=NS; Fig. 5D). Thus, activation of PMNs with known agonists also induced expression of CD18 and CD11b activation epitopes, even in the absence of exogenous microbial sialidase, suggesting that an agonist-induced mobilization of an endogenous source of sialidase activity could be involved in the physiologic activation of the integrin.

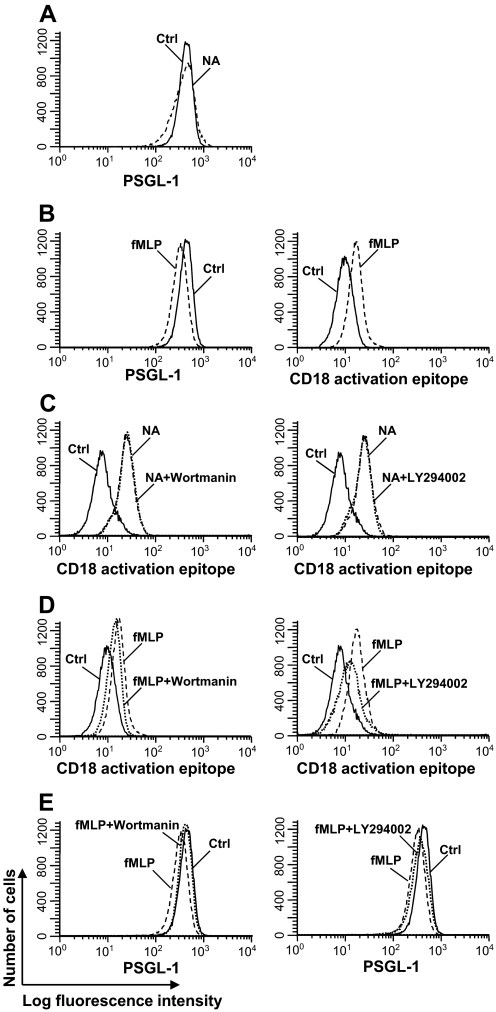

NA and fMLP treatments activate CD18 by different mechanisms

Upon activation, the surface PSGL-1 expression on PMN is down-regulated [26]. NA treatment did not alter the PSGL-1 expression on PMNs (MFI: 432 vs. 402; P=0.081; Fig. 6A), and stimulation with fMLP/cytochalasin B decreased the PSGL-1 expression level (MFI: 323 vs. 432; P<0.05) and increased expression of the CD18 activation epitope (MFI from 10.1 to 17.4; P<0.05; Fig. 6B). We wondered if NA treatment of PMNs differed from fMLP stimulation in their intracellular signaling. PI3K is an intracellular enzyme whose activity leads to the activation of downstream signaling cascades [27]. Pretreatment of PMNs with wortmannin or LY294002, two PI3K inhibitors, did not inhibit the enhanced expression of the activated CD18 epitope on NA-treated PMNs (MFI from 24.6 to 25.5 and from 24.6 to 23.7, respectively; P=NS; Fig. 6C). In contrast, similar treatment with the PI3K inhibitors inhibited the fMLP-induced expression of the activated CD18 epitope (MFI from 17.2 to 16.0, P<0.05; and from 17.2 to 12.0, P<0.05; Fig. 6D) and the down-regulation of PSGL-1 expression on fMLP-stimulated PMNs (MFI from 323 to 402, P<0.05; and from 323 to 361, P=0.049; Fig. 6E). These data suggest that NA and fMLP treatments activate CD18 by different signaling pathways.

Figure 6. PI3K inhibitor did not block NA-induced CD18 activation.

(A) PMNs (1×106/ml) were treated with NA (30 mU/ml; dashed line) for 1 h or untreated (solid line) and stained with PE-labeled anti-PSGL-1 antibody. (B) PMNs were stimulated at 37°C with fMLP (10−6 M) plus cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml; dashed line) for 10 min or untreated (solid line) and stained with PE-labeled anti-PSGL-1 antibody (left panel) or FITC-labeled anti-CD18 activation epitope (right panel). (C) PMNs were treated with NA (30 mU/ml; dotted line) for 1 h in the presence of wortmanin (200 nM, left panel) or LY294002 (50 μM, right panel) and stained with FITC labeled anti-CD18 activation epitope antibody. Untreated (solid line) or NA-treated cells (dashed line) were included as controls. (D) PMNs were stimulated with fMLP (10−6 M) plus cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml; dotted line) for 10 min in the presence of wortmanin (200 nM, left panel) or LY294002 (50 μM, right panel) and stained with FITC-labeled anti-CD18 activation epitope antibody. Untreated (solid line) and fMLP/cytochalasin B-stimulated (dashed line) cells were included for comparison. (E) Cells were treated as in D and stained with PE-labeled anti-PSGL-1 antibody. Data shown are representative of data from at least three independent experiments using different donors each with similar results.

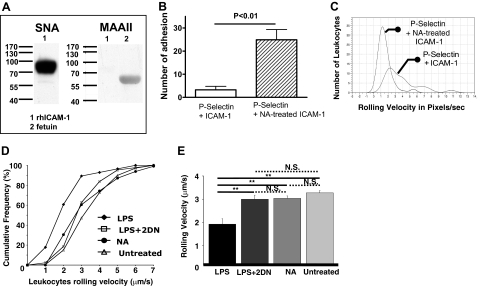

In vivo leukocyte arrest

Although removal of sialic acid residues from PMN β2 integrins promoted the binding of ICAM-1 to CD18 on PMNs in static adhesion assays, it was not clear whether the CD18/ICAM-1 interaction also occurs under physiologic blood flow in vivo. We have developed a murine model in which the binding of leukocytes to specific ligands can be studied under conditions in which leukocytes are subjected to physiologic shear force and unperturbed by any experimental manipulation and used this model to examine the role of ICAM-1 desialylation in leukocyte adhesion (Fig. 1). Using this system, we previously reported functional up-regulation of VLA-4 as well as PSGL-1 in systemic inflammation [17, 18]. We coated the microchambers with mock-treated and NA-treated rsICAM-1 and measured leukocyte arrest. ICAM-1 is a heavily N-glycosylated type I transmembrane protein belonging to the Ig superfamily of adhesion molecules with binding sites for LFA-1 and Mac-1 [20, 28]. With lectin blot, we confirmed that rsICAM-1 was a 90-kD protein with α-2,6 linkage sialylated: rsICAM-1 appeared at 90 KD and was recognized with SNA but not MAAII (Fig. 7A). Normal and desialylated ICAM-1 showed no difference in leukocyte binding (data not shown); however, the addition of untreated P-selectin to the chambers, along with the ICAM-1, resulted in marked differences. Chambers with NA-treated ICAM-1 but untreated P-selectin had an increase in the number of arrested leukocytes (24.9±4.4 vs. 3.25±leukocytes/fields of view; n=4 each; P<0.01; Fig. 7B) as well as a reduced rolling velocity (1.6±0.5 vs. 3.9±1.3 pixels/s; n=4 each; P<0.05; Fig. 7C). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that not only is the CD18 activation epitope masked by sialyl residues but that an ICAM-1 activation epitope is similarly glycosylated and that desialylation of the ICAM-1 promotes leukocyte arrest as well. Furthermore, our data indicate that the rolling receptor, P-selectin, is required for the initial tethering of the PMNs so that the subsequent firm adhesion to the ICAM-1 can take place.

Figure 7. Desialylation of ICAM-1 enhanced leukocyte rolling.

(A) rhICAM-1 (0.5 μg) was loaded and separated on 4–15% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to the PVDF membrane. The membranes were blotted with biotinylated SNA (left) or MAAII (right). Fetuin was included as a positive control for MAAII binding. (B and C) The autoperfused microflow chambers were prepared as described in Fig. 1 legend and the number of adhesive events in the absence or presence of NA treatment of rICAM-1 recorded (B). The rolling velocity of the cells arrested in the chamber was plotted (C). (D and E) Untreated C57BL/6 mice (n=3) were connected to the chambers, and the rolling of untreated, nonactivated leukocytes on the surface of the microchamber was recorded (▵, untreated). To assess the effect of desialylation on the rolling velocity of nonactivated leukocytes, NA (100 mU, i.v.) was given to mice (n=4), and 25 min later, 2-DN (500 μg, i.v.) was given to block any NA in the circulation. Mice were then connected to the double-coated chamber 5 min after the 2-DN (●, NA). A third group (n=4) was treated with LPS (150 μg, i.p.) and after 4 h, connected to the microchambers, where the leukocyte rolling was recorded (♦, LPS). In a final experimental group, mice (n=3) were treated with a single dose of 2-DN, and 30 min later, LPS (150 μg) i.p. was administered. After 4 h, mice were connected to the double-coated microchambers and rolling velocity determined (□, LPS+2-DN). **P < 0.05 between the two groups.

To test whether desialylation of leukocytes affects their arrest in vivo, we administered NA (100 mU) i.v. to the mice, 25 min later, injected the sialidase inhibitor 2-DN, and 5 min later, connected the animal to the chamber to record and analyze leukocyte rolling. This design prevented the in vivo-injected NA to desialylate the chamber's rmP-selectin and rICAM-1 coating when the chamber was connected to the mice. Under these conditions, there was no significant difference in the average leukocyte rolling velocity of NA-treated mice (3±0.1 μm/s) compared with untreated mice (3.3±0.1 μm/s; P=0.1; Fig. 7D). However, mice that were treated with LPS for 4 h before being connected to the chamber had a decrease in average leukocyte rolling velocity (1.9±0.2 μm/s) compared with the untreated (P=0.0000003) and the NA-treated groups (P=0.0003; Fig. 7D). When mice were given a single dose of 2-DN after LPS injection to inhibit desialylation, LPS was no longer capable of inducing the leukocyte arrest: the average rolling velocity (3.0±0.2 μm/s) was significantly higher than the LPS-treated group (P=0.0004) but did not differ from the average rolling velocities of the untreated or NA-treated groups (P>0.05; Fig. 7, D and E). This suggests that under physiologic conditions, in vivo desialylation alone is not sufficient to induce leukocyte arrest but that endogenous sialidase activity does play a role in the activation-induced binding of leukocytes to adhesion molecules expressed on ECs, perhaps by unmasking the binding site from the α I domain on the activated β2 integrin and/or sialyl residues from ICAM-1 on ECs.

DISCUSSION

Our studies show that removal of sialyl residues from the β2 integrin (CD11b/CD18) and ICAM-1 exposes activation epitopes on each of these binding partners that enhances their interaction, resulting in tight adhesion between PMNs and ECs. Further, agonist-induced mobilization of an endogenous sialidase may be a source of this desialylating activity, which could remove sialyl residues from adhesion molecules on the cell surface during diapedesis.

The activation of the β2 integrin is a critical event in diapedesis. LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) and LFA-2 (CD11b/CD18, Mac-1) are the principal β2 integrins on the PMN surface [10, 11]. Our data suggest a role for sialidase in β2-integrin regulation. It has been known that the integrin glycoproteins are sialylated and that these sialyl residues may mask binding sites for ICAM-1, but no one has proposed how this desialylation might occur in vivo during inflammation. Our data show that the β2-integrin and ICAM-1-binding partners are sialylated by an α2-6 linkage and that removal of these sialyl residues by exogenous sialidase unmasks CD18 and CD11b activation epitopes (Fig. 3) and increases the binding of PMNs to the ICAM-1 (Figs. 3 and 7). These adhesive events are abrogated by heat inactivation of the sialidase or the addition of the sialidase inhibitor, 2-DN. The binding of ICAM-1 to sialidase-treated PMNs is also blocked by the addition of rsICAM-1, thereby demonstrating the specificity of the β2-integrin/ICAM-1 interaction. Removal of sialyl residues from the CD11b/CD18 might not only promote conformational changes on the molecule itself, but by removing a negative charge, desialylation may also facilitate the clustering of the integrin molecules on the PMN surface (avidity). As clustering of the heterodimers is required for outside-in signaling, loss of sialyl residues on the integrins may remove the negative charges that would be expected to impede this event.

In this study, we used an exogenous source, Clostridium perfringens NANase, to remove sialyl residues from the glycoconjugates. We also demonstrate in vitro that activation of PMNs with known agonists induced expression of CD18 and CD11b activation epitopes, even in the absence of exogenous microbial sialidase, and this expression was decreased in the presence of the sialidase inhibitor. Administration of the sialidase inhibitor 2-DN in vivo reduced the LPS-induced leukocyte arrest under shear force to chambers coated with rsP-selectin and rsICAM-1. These data suggest that an endogenous source of sialidase activity could be involved in the physiologic activation of the integrin. Our laboratory described endogenous sialidase activity in human neutrophils that was mobilized to the cell surface following activation [7] (Fig. 4). This mobilized sialidase activity appeared to play a role in leukocyte trafficking and migration in vitro and in vivo [8, 9]. Blockade of PMN sialidase activity by pharmacologic inhibition or immune blockade inhibited their recruitment to inflamed sites in vivo.

Since our report, four isoforms of mammalian sialidase have been described, neu1–4, each of which is thought to differ based on cellular localization, substrate, and tissue specificity [24, 29]. We find that following activation with PMA or fMLP/cytochalasin B, there is increased expression of neu1 but not neu3, the other prominent NEU gene associated with hPMNs, and that neu1 colocalizes with CD18 (Fig. 4). Thus, neu1 might be in sufficiently close proximity to the β2 integrin to remove sialyl residues from this adhesion molecule.

In the present study, we show that not only does the removal of sialyl residues promote the binding of a sICAM-1 preparation to PMNs but also that the sialidase-treated cells bind to immobilized ICAM-1. The heavily glycosylated ICAM-1 adhesion molecule has binding sites for LFA-1 and Mac-1 [20, 28]. An earlier study found that binding of hICAM-1 to Mac-1 but not to LFA-1 was hindered by sialyl residues on the third Ig domain [20]; however, a potential role for sialyl residue modification of ICAM-1 by endogenous sialidase activity was not proposed. Palmblad and Lerner [30] had reported that LTB4 treatment of ECs induced a “hyperadhesive” state for PMNs and suggested that ICAM-1 or a CD54-like molecule had to be “activated” to be optimally functional. Indeed, when examined under conditions of physiologic shear force in an ex vivo model of leukostasis, we found that removal of sialyl residues on ICAM-1 greatly enhanced the binding of PMNs to ICAM-1 (Fig. 7). We speculate that the sialidase translocated to the PMN surface during activation may remove critical sialyl residues that unmask the firm binding site from the αI domain on the activated β2 integrin and that PMN or a EC sialidase might remove sialyl residues from ICAM-1 on ECs.

Activation of integrins may occur through “inside-out” or “outside-in” signaling, whereby signals are transmitted to or from the cytoplasm across the plasma membrane in a bidirectional manner using the same pathways but traveling in opposite directions [12]. Only a subset of the integrin molecules on the cell surface may be thus activated [31]. In the former instance, activation of G-protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptors, such as IL-8R and fMLPR, initiates intracellular signaling cascades, followed by signaling to the ectodomain that leads to conformational shift and ability to bind its ligand. In contrast, outside-in signaling is initiated by activation of the integrin ectodomain, which transmits signaling to the cytoplasm through a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent cascade leading to cytoskeletal reorganization and downstream events [32].

As in a previous study using IL-8, PI3K inhibitors blocked expression of the CD18 activation epitope induced by fMLP. In our study, these inhibitors were unable to do so with exogenous sialidase treatment (Fig. 6). These data suggest that the PI3K pathway, a critical intracellular signaling cascade involved in inside-out signaling, may not be involved in β2-integrin activation following exogenous neuraminidase treatment.

Thus, our data show that β2 integrins on hPMNs and their binding partner on ECs, ICAM-1, have α2,6-linked sialyl residues that mask activation epitopes involved in tight adhesion during diapedesis. Further, the endogenous sialidase activity of PMNs could mediate this desialylation of the β2 integrin, and based on our previous observation that activated PMNs could desialylate ECs [8], they might remove sialyl residues of ICAM-1 on ECs as well. Inhibition of sialidase activity inhibited the recruitment of PMNs into inflammatory sites in experimental murine models of inflammation [9]. These data extend those observations by identifying potential molecular targets of that therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH grant HL0869 33-01A1 to A.S.C.

Footnotes

- 2-DN

- 2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-N-acetylneuraminic acid

- 4-MUNANA

- 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid sodium salt hydrate

- CMP

- cytidine monophosphate

- EC

- endothelial cell

- h

- human

- m

- murine

- MAAII

- Maackia amurensis lectin II

- Mac-1

- macrophage antigen 1

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

- NA

- Clostridium perfringens neuraminidase type X

- PNA

- peanut agglutinin lectin

- PSGL-1

- P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1

- s

- soluble

- SNA

- Sambucus nigra lectin

AUTHORSHIP

C.F., L.Z., L.A., S.F., and M.W. performed the experiments; C.F., L.A., S.F., and A.H-M. analyzed results and made the figures; and C.F. and A.S.C. designed the research and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kearse K. P., Cassatt D. R., Kaplan A. M., Cohen D. A. (1988) The requirement for surface Ig signaling as a prerequisite for T cell:B cell interactions: a possible role for desialylation. J. Immunol. 140, 1770–1778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schauer R. (1985) Sialic acids and their role as biological masks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 10, 357–360 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hayes G. R., Lockwood D. H. (1986) The role of cell surface sialic acid in insulin receptor function and insulin action. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2791–2798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bridges K., Harford J., Ashwell G., Klausner R. D. (1982) Fate of receptor and ligand during endocytosis of asialoglycoproteins by isolated hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 350–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hasegawa T., Yamaguchi K., Wada T., Takeda A., Itoyama Y., Miyagi T. (2000) Molecular cloning of mouse ganglioside sialidase and its increased expression in Neuro2a cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8007–8015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fogel M., Altevogt P., Schirrmacher V. (1983) Metastatic potential severely altered by changes in tumor cell adhesiveness and cell surface sialylation. J. Exp. Med. 157, 371–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cross A. S., Wright D. G. (1991) Mobilization of sialidase from intercellular stores to the surface of human neutrophils and its role in stimulated adhesion responses of these cells. J. Clin. Invest. 88, 2067–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakarya S., Rifat S., Zhou J., Bannerman D. D., Stamatos N. M., Cross A. S., Goldbulum S. E. (2004) Mobilization of neutrophil sialidase activity desialylates the endothelial surface and increases resting neutrophil adhesion to and migration across the endothelium. Glycobiology 14, 481–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cross A. S., Sakarya S., Rifat S., Held T. K., Drysdale B-E., Grange P. A., Cassels F. J., Wang L-X., Stamatos N., Farese A., Casey D., Powell J., Bhattacharjee A. K., Kleinberg M., Goldblum S. E. (2003) Recruitment of murine neutrophils in vivo through endogenous sialidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4112–4120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanchez-Madrid F., Nagy J., Robbins E., Simon P., Springer T. A. (1983) A human leukocyte differentiation antigen family with distinct α subunits and a common β subunit; the lymphocyte function associated antigen-1 (LFA-1), the C3bi complement receptor (OKM1/Mac-1) and the p150.95 molecule. J. Exp. Med. 158, 1785–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luo B-H., Carman C. V., Springer T. A. (2007) Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 619–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abram C. L., Lowell C. A. (2009) The ins and outs of leukocyte integrin signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 339–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takagi J., Petre B. M., Walz T., Springer T. A. (2002) Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell 110, 599–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McDowall A., Leitinger B., Stanley P., Bates P. A., Randi A. M., Hogg N. (1998) The I domain of integrin leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 is involved in a conformational change leading to high affinity binding to ligand intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27396–27403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans R., Patzak I., Svensson L., DeFilippo K., Jones K., McDowall A., Hogg N. (2009) Integrins in immunity. J. Cell Sci. 122, 215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rifat S., Kang T. J., Mann D., Zhang L., Puche A. C., Stamatos N. M., Goldblum S. E., Brossmer R., Cross A. S. (2008) Expression of sialyltransferase activity on intact human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84, 1075–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hafezi-Moghadam A., Thomas K. L., Cornelssen C. (2004) A novel mouse-driven ex vivo flow chamber for the study of leukocyte and platelet function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C876–C892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Almulki L., Amini R., Schering A., Garland R. C., Nakao S., Nakazawa T., Hisatomi T., Thomas K. L., Masil S., Hafezi-Moghadam A. (2009) Surprising up-regulation of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) in endotoxin-induced uveitis. FASEB J. 23, 929–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Takeda A. (1987) Sialylation patterns of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) differ between T and B lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 17, 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diamond M. S., Staunton D. E., Marlin S. D., Springer T. A. (1991) Binding of the integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) to the third immunoglobulin-like domain of ICAM-1 (CD54) and its regulation by glycosylation. Cell 65, 961–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abe Y., Smith C. W., Katkin J. P., Thurmon L. M., Xu X., Mendoza L. H., Ballantyne C. M. (1999) Endothelial α 2,6-linked sialic acid inhibits VCAM-1-dependent adhesion under flow conditions. J. Immunol. 163, 2867–2876 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drbal K., Angelisova P., Hilgert I., Cerny J., Novak P., Horejsi V. (2001) A proteolytically truncated form of free CD18, the common chain of leukocyte integrins, as a novel marker of activated myeloid cells. Blood 98, 1561–1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Novogrodsky A., Lotan R., Ravid A., Sharon N. (1975) Peanut agglutinin, a new mitogen that binds to galactosyl sites exposed after neuraminidase treatment. J. Immunol. 115, 1243–1248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Monti E., Preti A., Venerando B., Borsani G. (2002) Recent developments in mammalian sialidase molecular biology. Neurochem. Res. 27, 649–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Papini N., Anastasia L., Tringali C., Croci G., Bresiani R., Yamaguchi K., Miyagi T., Preti A., Prinetti A., Prioni S., Sonnino S., Tettamanti G., Venerando B., Monti E. (2004) The plasma membrane-associated sialidase mNEU3 modifies the ganglioside pattern of adjacent cells supporting its involvement in cell-to-cell interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16989–16995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carlow D. A., Gossens K., Naus S., Veerman K. M., Seo W., Ziltener H. J. (2009) PSGL-1 function in immunity and steady state homeostasis. Immunol. Rev. 230, 75–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ridley A. J., Schwartz M. A., Burridge K., Firtel R. A., Ginsberg M. H., Borisy G., Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R. (2003) Cell: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diamond M. S., Staunton D. E., deFougerolles A. R., Stacker S. A., Garcia-Aguilar J., Hibbs M. L., Springer T. A. (1990) ICAM-1 (CD54): a counter receptor for Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18). J. Cell Biol. 111, 3129–3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monti E., Bassi M. T., Bresciani R., Civini S., Croci G. L., Papini N., Riboni M., Zanchetti G., Ballabio A., Preti A., Tettamanti G., Venerando B., Borsani G. (2004) Molecular cloning and characterization of NEU4,the fourth member of the human sialidase gene family. Genomics 83, 445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palmblad J. E., Lerner R. (1992) Leukotriene B4-induced hyperadhesiveness of endothelial cells for neutrophils: relation to CD54. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 90, 300–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diamond M. S., Springer T. A. (1993) A subpopulation of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) molecules mediates neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1 and fibrinogen. J. Cell Biol. 120, 545–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walzog B., Offermanns S., Zakrzewicz A., Gaehtgens P., Ley K. (1996) β2 integrins mediate protein tyrosine phosphorylation in human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 59, 747–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]