Review focuses on the role of STAT3, SFB, and Ahr in Th17 differentiation, as well as innate sources of Th17 cytokines.

Keywords: IL-17, IL-22, STAT3, segmented filamentous bacteria, aryl hydrocarbon receptor

Abstract

Th17 cells contribute to mucosal immunity by stimulating epithelial cells to induce antimicrobial peptides, granulopoiesis, neutrophil recruitment, and tissue repair. Recent studies have identified important roles for commensal microbiota and Ahr ligands in stabilizing Th17 gene expression in vivo, linking environmental cues to CD4 T cell polarization. Epigenetic changes that occur during the transition from naïve to effector Th17 cells increase the accessibility of il17a, il17f, and il22 loci to transcription factors. In addition, Th17 cells maintain the potential for expressing T-bet, Foxp3, or GATA-binding protein-3, explaining their plastic nature under various cytokine microenvironments. Although CD4 T cells are major sources of IL-17 and IL-22, innate cell populations, including γδ T cells, NK cells, and lymphoid tissue-inducer cells, are early sources of these cytokines during IL-23-driven responses. Epithelial cells and fibroblasts are important cellular targets for IL-17 in vivo; however, recent data suggest that macrophages and B cells are also stimulated directly by IL-17. Thus, Th17 cells interact with multiple populations to facilitate protection against intracellular and extracellular pathogens.

Introduction

CD4+ T cells are critical effector cells of adaptive immune responses. The differentiation of naive to effector and memory T cells is complex with many checkpoints and balances along the way (reviewed in ref. [1]). In LNs, the presentation of exogenous Ag and costimulatory signals to naïve T cells primes their differentiation into specialized subsets. The route of Ag delivery or type of APC may influence T cell polarization. DCs are efficient at processing exogenous Ags into the MHC class II pathway and are surveyed by naïve T cells in LN subcortical regions. Other APC populations include macrophages, B cells, basophils, and plasmacytoid DCs. The differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into Th1 is important for controlling intracellular bacteria infections while Th2 cells initiate antibody responses against extracellular pathogens. Moreover, Th2 cells are critical for the expulsion of helminths. More recently, Th17 cells were found to be protective against infections at mucosal surfaces (reviewed in ref. [2]). Th17 cells work through multiple effector mechanisms, including coordinating granulopoiesis, neutrophil recruitment, induction of antimicrobial proteins and chemokines, germinal center formation, and antibody isotype switching [2–4]. The main effector cytokines associated with Th17 cells include IL-17A (IL-17), IL-17F, and IL-22 [5, 6], and they may express any combination of these. Although in vitro studies deciphered molecular mechanisms governing Th17 differentiation, the physiological circumstances under which this happens in vivo are still being elucidated, including the influence of endogenous and environmental factors. Understanding the maintenance and breadth of Th17 effector functions will reveal why they exist despite their potential for mediating autoimmune inflammation. Non-CD4+ T cell populations such as γδ T cells and NK cells are also capable of producing Th17 cytokines, suggesting that Ag-independent triggers can be responsible for initiating this type of inflammation commonly associated with Th17 immunity.

Th17 DIFFERENTIATION

Differentiation of T cell subsets is coordinated by lineage-specific transcription factors [1]. The anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β drives Treg differentiation by inducing Foxp3 [7]. IL-6 prevents the induction of Foxp3 by TGF-β and instead directs T cells toward the Th17 lineage by inducing rorc and rora, encoding RORγt and RORα, respectively [8–10]. This mechanism by which IL-6 promotes Th17 differentiation involves STAT3 activation [11, 12] and the production of IL-21 by T cells [13–16]. On the other hand, TGF-β indirectly supports Th17 polarization by inhibiting Th1 and Th2 differentiation [17, 18]. The acquisition of inflammatory potential in Th17 cells is driven by IL-23: culturing Th17 cells with IL-23 results in inflammatory cytokine production and the ability to transfer disease, whereas culturing Th17 cells with TGF-β plus IL-6 causes them to produce IL-10 [19, 20]. This effect may be explained by the ability of IL-23 to induce T-bet expression in Th17 cells [19, 21]. Ghoreschi et al. [19] compared transcriptional profiles of conventional Th17 cells generated with IL-6 plus TGF-β [Th17(β)] versus Th17 cells generated with IL-6 plus IL-23 [Th17(23)] and found that over 2000 genes were differentially expressed. For instance, Th17(23) cells expressed higher levels of Tbx21, Il18r1, Cxcr3, and Il33, whereas Th17(β) cells expressed higher levels of Il9, Il10, and Ccl20. IL-23 can also directly promote Th17 differentiation by increasing rorc expression in combination with IL-1β and IL-6 [19]. Overall, these data suggests that distinct subsets, Th17(β) versus Th17(23), can be identified by their transcriptional profile, and these populations differ in their ability to mediate disease. The positive impact of IL-1β on Th17 differentiation suggests that the multitude of endogenous and exogenous factors, which stimulate inflammasome activity, can support Th17-mediated inflammation [22–24].

STAT3 coordinates Th17 differentiation by binding to promoters for many Th17 genes including rorc, rora, il17a, il17f, il6ra, il21, and il23r [25]. Humans with STAT3 deficiency have impaired Th17 responses [26–29], and the induction of experimental autoimmune diseases requires STAT3 signaling in CD4 T cells [11, 30], suggesting that this molecule could be a useful therapeutic target. Cytokines that can prime Th17 differentiation through STAT3 include IL-6, IL-9, and IL-21 [11, 12, 15, 31]. IL-27 is similar to IL-6 in that it signals through gp130 and STAT3 [32–34]; however, IL-27 inhibits Th17 differentiation, suggesting that STAT3 activation in itself is not sufficient or that STAT1, which is also activated by IL-27, has a dominant inhibitory effect on Th17 differentiation [35–37]. Aside from Th17 differentiation, STAT3 has other functions, including supporting Th2 differentiation, Treg function, and peripheral T cell proliferation and survial [25, 38, 39]. STAT3 has also been linked to IL-17 production by CD8 T cells [40, 41]. In contrast, some naturally arising Th17 cells in the thymus are STAT3-independent [42]. Altogether, this suggests that STAT3 signaling may be specifically required for the acquisition of IL-17 potential in secondary lymphoid tissues.

SFB INDUCE LOCAL AND SYSTEMIC Th17 RESPONSES

The intestinal microbiota influences various aspects of immunity, including the maturation of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, IgA class switching, and the recruitment of activated lymphocytes (reviewed in ref. [43]). As microbial products can have pro- or anti-inflammatory effects, they influence the basal level of inflammation in the gut. One mechanism by which this occurs involves TLR stimulation on DCs, resulting in their migration to mesenteric LN, where they activate T cells. The T cells may respond by driving IgA class switching in B cells or the expression of antimicrobial defensins from intestinal epithelial cells [43]. Microbiota can also impact systemic immune responses, including susceptibility to autoimmunity or allergy, and understanding their role in shaping inflammation has therapeutic applications.

Commensal bacteria support steady-state Th17 levels, as germ-free mice lack Th17 cells in the intestinal lamina propria [44–47]. The presence of SFB in the gut was recently found to be an important contributor to Th17 polarization [48, 49]. The emergence of Th17 cells correlates well with SFB colonization around weaning time [46, 50], and colonization of mice with SFB significantly increases IL-17 levels [48, 49]. SFB are transmitted through the fecal-oral route, inhabit a number of vertebrate species, and localize to small intestinal epithelial cells [50–52]. In addition, SFB are found in rainbow trout [53]. As SFB adhere to Peyer's patches and stimulate IgA responses in the gut and serum [48, 54, 55], they could assist in preventing bacterial translocation across the epithelium. Host PRRs that drive Th17 differentiation in response to SFB have not been elucidated, although serum amyloid A contributes to the effect [49]. It is notable that MyD88−/− × Toll/IL-1R domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β−/− mice have normal Th17 numbers in lamina propria [44], suggesting that TLR signals do not impact steady-state levels of Th17 cells. SFB colonization in the gut was found to enhance autoimmune arthritis and EAE [56, 57], demonstrating its impact on systemic Th17 responses. In addition to increasing IL-17 levels, SFB increases IFN-γ and IL-4 production in lamina propria, suggesting a positive impact on Th1 and Th2 differentiation as well [48]. In contrast, the abundance of Tregs found in colonic mucosa is maintained in part by Clostridium species [58]. Thus, microbial species differentially influence the intestinal Th cell balance, impacting systemic adaptive immunity.

THE Ahr SUPPORTS Th17 POLARIZATION AND IL-22 PRODUCTION

The Ahr is a cytosolic sensor for a broad range of chemicals containing two carbon ring systems, including tryptophan derivatives (reviewed in ref. [59]). Among the most studied Ahr agonists are TCDD and FICZ, a tryptophan-derived photoproduct. Ligation of Ahr results in its nuclear translocation and binding to gene promoters containing dioxin-responsive elements [59]. Tissues that contact the external environment express high levels of Ahr, such as the intestine, lung, and liver. Among the numerous processes regulated by Ahr are neurogenesis, vascularization, circadian rhythm, liver development, metabolism, and cell stress [59]. In addition, the role of Ahr expression by individual cell populations such as hematopoietic stem cells is actively being studied (reviewed in ref. [60]).

The finding that Ahr-deficient mice have fewer Tregs and enhanced susceptibility to autoimmunity supports its role as an immunosuppressive molecule [61, 62]. TCDD and the endogenous ligand 2-(1′H-indole-3′-carbonyl)-thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester were found to induce Foxp3 and functional Tregs [63–66]. On the other hand, FICZ preferentially supports Th17 differentiation [62, 67], suggesting that the binding affinity for Ahr differentially impacts gene expression. This could be a result of higher expression levels of Ahr in Th17 cells compared with Tregs [68, 69], resulting in increased sensitivity to Ahr ligands. Alternatively, the kinetics of Ahr activation may be responsible for functional differences between these ligands, as FICZ but not TCDD is degraded by xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes [59]. The expression of Ahr by phenotypically naïve CD62L+ cells [68] suggests a possible feedback loop in which the presence of Ahr ligands during Th polarization helps to maintain Ahr expression in effector/memory T cells. Ahr does not affect the expression of rorc or rora in developing Th17 cells but rather supports Th17 differentiation by directly inhibiting STAT1 and STAT5 [67, 68]. Ahr deficiency also impairs IL-22 responses [69], suggesting the involvement of endogenous ligands. The Notch pathway may provide a physiological target to regulate inflammation, as RBP-J stimulation increases IL-22 production through Ahr [70]. Notably, RBP-J-deficient mice were sensitive to Con A-induced hepatitis as a result of a lack of IL-22, and Notch signaling increased an endogenous Ahr agonist in Th17 cells. In human T cells, Ahr specifically enhances IL-22 production without affecting IL-17 [71, 72]. In addition to CD4 T cells, Ahr promotes IL-22 production by γδ T cells [73], and human immature NK cells required IL-1β to maintain Ahr expression and IL-22 potential [74]. Thus, Ahr expression in multiple lymphocyte subsets contributes to their IL-22 potential, and Ahr ligands have distinct effects on T cell differentiation.

Th17 STABILITY, PLASTICITY, AND EPIGENETICS

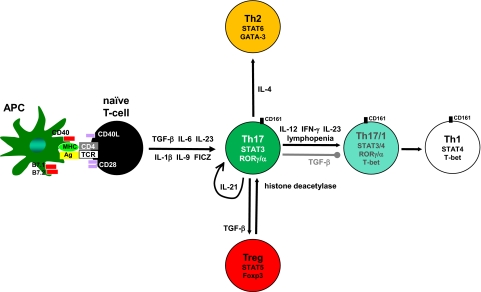

Many studies have focused on the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into effector subsets; however, recently, there has been attention toward understanding the interconversion among subsets. The balance between Tregs and Th17 cells in culture is controlled by various factors including IL-6, IL-1, IL-23, and retinoic acid [8, 75–77]. Moreover, some CD4 T cells at mucosal sites coexpress Foxp3 and RORγt [78, 79], suggesting the local milieu determines whether Tregs or Th17 cells are preferentially induced in vivo. DCs play an important role in T cell polarization, and DCs activated via dectin-1 but not TLR9 are able to stimulate IL-17 production from Foxp3+ RORγt+ cells [76]. This population that coexpresses Foxp3, RORγt, and IL-17 functions as suppressors in human and mouse models [80, 81]. Th17 cells are also capable of converting into Th1 or Th2 lineages but not vice versa (Fig. 1 and refs. [82, 83]). For instance, the presence of IFN-γ and/or IL-12 will cause Th17 cells to up-regulate T-bet and produce IFN-γ [84, 85]. It has been suggested that IL-17+ IFN-γ+ cells are derived from Th17 and can be identified by the surface marker CD161 [86]. Simply transferring Th17 cells into lymphopenic hosts will also result in their Th1 conversion [83, 87]. CD8 T cells producing IL-17 can switch to IFN-γ production in vivo [41], suggesting a fundamental mechanism underlying effector plasticity in CD4 and CD8 lineages.

Figure 1. Extracellular factors controlling Th17 plasticity.

CD4 T cell effector differentiation requires antigen and costimulatory signals derived from APCs. The presence of TGF-β and IL-6 induces IL-21 in T cells, which acts in an autocrine manner through the transcription factor STAT3 to establish Th17 commitment. IL-23 and IL-9 also activate STAT3 to promote Th17 differentiation. The tryptophan photoproduct FICZ induces IL-17 through the Ahr. The transcription factors RORγ and RORα function to stabilize IL-17 expression. Removing TGF-β from the milieu results in Th17 cells converting to Th1, preceded by an intermediate RORγ+/α+ T-bet+ CD161+ stage. IL-23 also up-regulates the expression of T-bet and IFN-γ in Th17 cells. Other signals resulting in Th1 conversion include IL-12, IFN-γ, and lymphopenia. In addition, Th17 cells are capable of converting into Tregs and vice versa. For instance, histone deacetylase activity promotes Treg conversion into Th17, suggesting that an epigenetic mechanism contributes to their reciprocal relationship. Further, stimulating Th17 cells with IL-4 increases GATA-binding protein-3 (GATA-3) expression and Th2 conversion. Therefore, effector Th17 cells are highly adaptable to their cytokine microenvironment, which may partially explain their association with pro- and anti-inflammatory functions.

The expression of Th17 effector cytokines is associated with epigenetic changes in promoter regions. The combination of TGF-β and IL-6 causes histone acetylation at the il17a and il17f promoters, enhancing the accessibility of chromatin to transcription factors [88]. STAT3, which is activated through IL-6, promotes epigenetic modifications associated with the Th17 signature [25]. The conversion of human Tregs to Th17 by allogeneic stimulation required histone deacetylation [89]. Histone trimethylation maps revealed that Tbx21, encoding the Th1 transcription factor T-bet, has a broad spectrum of epigenetic states, explaining how multiple Th subsets can be conditioned for IFN-γ production [90]. This mechanism may underlie the basis for Th plasticity. Mapping DNase I hypersensitivity sites revealed that Th17 cell activation in the presence of IL-12 modifies the IFN-γ promoter, and accessibility to the il17a locus was limited to Th17 cells [91]. Thus, studying the epigenetic state of histones at promoters associated with Th lineages has contributed to our understanding of T cell differentiation and stability.

INNATE SOURCES OF IL-17 AND IL-22

Although CD4+ T cells are major sources of IL-17 and IL-22 [92], some innate cell populations can also produce Th17-type cytokines when stimulated with IL-23 (Table 1). γδ T cells are prominent sources of IL-17 in a number of models (reviewed in ref. [101]), including EAE, where IL-17 can be independent of TCR stimulation [109]. iNKT cells produce IL-17 and IL-22 in response to heat-killed bacteria [108]. In lymphocyte-deficient mice, the IL-23/IL-17 axis contributes to inflammatory bowel diseases [96, 110]. In this case, Gr-1+ CD11b+ cells were a significant source of intestinal IL-17 [96]. Neutrophil-derived IL-17 was also reported in LPS-induced lung inflammation [97], kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury [98], and systemic vasculitis [99]. TLR2 stimulation induced IL-17 in macrophages [100]. Subsets of mucosal NK cells have been found to produce IL-22 [94, 105, 106]. LTi-like cells identified as CD4+ CD3– are an early source of IL-17 and IL-22 following treatment with zymosan or flagellin [102, 103]. These cells require the common γ chain for development and express IL-23R, Ahr, and RORγt. DCs were upstream of the LTi cell response, possibly as a result of their specialized role in amplifying IL-6 levels following treatment with PAMPs [102]. In response to Citrobacter rodentium infection, LTi cells were critical for the IL-22 production and host defense [104]. Further, reconstituting RORγ−/− mice with LTi cells restored IgA levels through the induction of isolated lymphoid follicles, independently of T cells [111]. Another innate population identified as Thy1+ lineage– CD4– Sca-1+ CCR6+ was critical for bacteria-driven innate colitis [107]. This population expresses RORγt and mediates colitis through IL-17. Altogether, multiple innate cell types produce IL-17 and/or IL-22 in a RORγ-dependent manner following IL-23 treatment. Studying their physiological roles can help us to understand why T cells evolved to become specific and specialized IL-17 producers. Further, this information identifies pathways that can be used to trigger Th17 effector cytokines in lymphopenic patients.

Table 1. Cellular Sources of IL-17 and IL-22.

| Lymphocytes | IL-17 refs. | IL-22 refs. | Nonlymphocytes | IL-17 refs. | IL-22 refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ T cells | 92, 93 | 94, 95 | Neutrophils (Gr-1+ CD11b+) | 96–99 | |

| CD8+ T cells | 40, 41 | Macrophages | 100 | ||

| γδ T cells | reviewed in 101 | reviewed in 101 | LTi-like (CD4+ CD127+ CD3–) | 102, 103 | 102–104 |

| NK cells | 105, 106 | Innate lymphoid cells (Thy1+ lin– CD4– Sca-1+ CCR6+) | 107 | ||

| iNKT cells | 108 | 108 |

POTENTIAL EFFECTOR MECHANISMS OF Th17 CYTOKINES IN THE MUCOSA

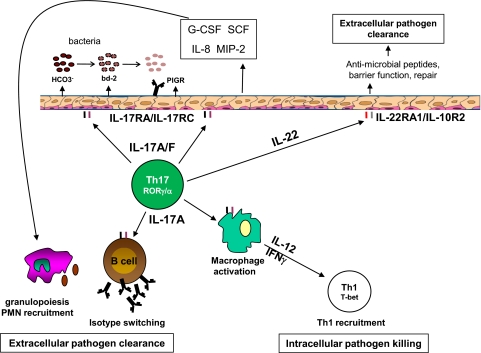

One of the earliest functions described for IL-17 was its ability to stimulate granulopoiesis in vivo [112]. This is not a direct effect of IL-17 on hematopoietic progenitors but rather, is mediated by the induction of G-CSF and SCF in epithelial cells (Fig. 2 and refs. [93, 113]). IL-17 also contributes to hematopoietic recovery following γ radiation [114]. The action of IL-17 on bronchial epithelial cells causes them to produce IL-8 and MIP-2, resulting in neutrophil recruitment to the lung [115, 116]. In addition, IL-17 mediates neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneum through keratinocyte-derived chemokine [117]. Other important functions of IL-17 on lung epithelium include the induction of antimicrobial genes (β-defensins, S100 family) and HCO3– secretion through cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator [2, 118]. Interestingly, carbonate ion increases bacterial membrane permeability and susceptibility to human β-defensin 2 [119]; thus, the coinduction of defensin gene expression and HCO3– transport may be an important mechanism by which IL-17 mediates mucosal immunity (Fig. 2). The variety of genes induced by IL-17 on epithelial cells impacts host resistance to many bacterial and fungal pathogens (reviewed in ref. [120]).

Figure 2. Th17 effector functions in the lung.

IL-17 and the related cytokine IL-17F stimulate lung epithelial cells through the IL-17RA/IL-17RC complex, inducing mediators that promote granulopoiesis and neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection (G-CSF, SCF, IL-8, MIP-2). In addition, IL-17 facilitates HCO3– secretion and expression of antimicrobial peptides [i.e., β-defensin-2; (bd-2)], which directly promote bacterial membrane lysis. IL-22 stimulates the IL-22RA/IL-10R2 complex on lung epithelium, facilitating injury repair and antimicrobial gene expression. In addition to these functions, IL-17 directly stimulates macrophages to produce IL-12, enhancing Th1 immunity to intracellular infections. IL-17 promotes humoral immunity by directly stimulating B cells to undergo isotype switching as well as increasing expression of the PIGR on lung epithelium. In this manner, Th17 cells support memory responses to extracellular pathogens.

Although antibody responses were found to be diminished in IL-17−/− and IL-23p19−/− mice [121, 122], it was unclear if this was a result of the direct action of IL-17 on B cells. Recent studies have found that IL-17 directly promotes B cell isotype switching and germinal center formation [3, 4, 123, 124]. This is relevant to autoimmunity, as systemic lupus erythematosus patients have high serum levels of IL-17, which sustained peripheral B cell survival, proliferation, and IgM secretion [124]. Th17 cells also mediated B cell recruitment to the lung and expression of the PIGR on airway epithelium [125]. Thus, Th17 cells promote multiple aspects of humoral immunity (Fig. 2).

The degree to which different Th17 cytokines have redundant functions in mucosal immunity is also being explored. Although IL-17RA is required for host defense, multiple IL-17 family members signal through IL-17RA (IL-17, IL-17F, IL-25; reviewed in ref. [126]). Mice that are double-deficient for IL-17 and IL-17F, but not single-deficient mice, are susceptible to systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection, indicating partially redundant roles for these cytokines [127]. On the other hand, expression of both IL-17 and IL-17F was required for the induction of β-defensins and immunity to oral C. rodentium infection. In conjunction with IL-17, IL-22 increases the expression of G-CSF and antimicrobial genes including lipocalin-2 in lung epithelium [128]. Further, IL-22 enhances the clonogenic potential of lung epithelium independently of IL-17 and tissue repair following injury. As a result, IL-22 is required for host defense and survival following pulmonary Klebsiella pneumoniae infection [128]. In the gut, IL-22 has similar functions and mediates protection to C. rodentium through the induction of antimicrobial genes (Reg3β and Reg3γ) and maintenance of colonic epithelial integrity [129]. In toxoplasmosis, however, IL-22 was found to be proinflammatory [130]. Other important targets of IL-22 in vivo include keratinocytes, liver, and pancreas (reviewed in ref. [95]). Overall, Th17 cells produce multiple effector cytokines with partially overlapping roles in immunity.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Environmental factors controlling Th17 responses in vivo are actively being investigated. Maintaining a reservoir of Th17 cells in the gut is important for barrier functions and preventing Salmonella typhimurium dissemination [131]. However, the impact of the intestinal microenvironment, including the presence of SFB, on systemic Th17 responses remains an interesting question. The plastic nature of Th17 cells underlies the importance of controlling its expression and localization, and whether Th17 responses are intrinsically or extrinsically regulated in vivo is unclear. The longevity of Th17 cells following intranasal infection was of shorter duration than the Th1 pool generated with systemic infection [132], and this was associated with decreased expression of the survival molecule Bcl-2 in CD27– IL-17+ T cells compared with CD27+ IFN-γ+ T cells. Although innate immune cells are capable of producing IL-17 and IL-22, the selective advantage for CD4 T cells to acquire this potential suggests that IL-17 is very important for secondary immune responses. In support, IL-17 contributes to vaccine-induced immunity by increasing Th1 cell recruitment to the site of infection (Fig. 2 and ref. [133]). Although IL-17 effector functions were initially studied on epithelial cells, leukocytes are also important targets for IL-17 in vivo. For instance, IL-17 conditions macrophages for IL-12 production and promotes Th1 immunity to the intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis [134]. Overall, selectively targeting the IL-17 pathway on cell populations may be a way to promote immunity while minimizing unwanted side-effects such as autoimmune inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health NHLBI grants 5R37HL079142-07 and 5P50HL084935-05 to J.K.K.

Footnotes

- Ahr

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- CD40/62L

- CD40/62 ligand

- EAE

- experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- FICZ

- 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole

- Foxp3

- forkhead box p3

- HCO3–

- bicarbonate

- iNKT cell

- invariant NK T cell

- LTi cell

- lymphoid tissue inducer cell

- PIGR

- polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- RBP-J

- recombination signal-binding protein-J

- Reg3β/γ

- regenerating islet-derived family β/γ

- ROR

- retinoid-related orphan receptor

- SCF

- stem cell factor

- SFB

- segmented filamentous bacteria

- T-bet

- T-box expressed in T cells

- TCDD

- 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzodioxin

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

REFERENCES

- 1. Wan Y. Y., Flavell R. A. (2009) How diverse—CD4 effector T cells and their functions. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 20–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khader S. A., Gaffen S. L., Kolls J. K. (2009) Th17 cells at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity against infectious diseases at the mucosa. Mucosal Immunol. 2, 403–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitsdoerffer M., Lee Y., Jager A., Kim H. J., Korn T., Kolls J. K., Cantor H., Bettelli E., Kuchroo V. K. (2010) Proinflammatory T helper type 17 cells are effective B-cell helpers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14292–14297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsu H. C., Yang P., Wang J., Wu Q., Myers R., Chen J., Yi J., Guentert T., Tousson A., Stanus A. L., et al. (2008) Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat. Immunol. 9, 166–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liang S. C., Tan X. Y., Luxenberg D. P., Karim R., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Collins M., Fouser L. A. (2006) Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2271–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilson N. J., Boniface K., Chan J. R., McKenzie B. S., Blumenschein W. M., Mattson J. D., Basham B., Smith K., Chen T., Morel F., et al. (2007) Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 950–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen W., Jin W., Hardegen N., Lei K. J., Li L., Marinos N., McGrady G., Wahl S. M. (2003) Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25– naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-β induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J. Exp. Med. 198, 1875–1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bettelli E., Carrier Y., Gao W., Korn T., Strom T. B., Oukka M., Weiner H. L., Kuchroo V. K. (2006) Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ivanov I. I., McKenzie B. S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C. E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J. J., Cua D. J., Littman D. R. (2006) The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang X. O., Pappu B. P., Nurieva R., Akimzhanov A., Kang H. S., Chung Y., Ma L., Shah B., Panopoulos A. D., Schluns K. S., Watowich S. S., Tian Q., Jetten A. M., Dong C. (2008) T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR α and ROR γ. Immunity 28, 29–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris T. J., Grosso J. F., Yen H. R., Xin H., Kortylewski M., Albesiano E., Hipkiss E. L., Getnet D., Goldberg M. V., Maris C. H., Housseau F., Yu H., Pardoll D. M., Drake C. G. (2007) Cutting edge: an in vivo requirement for STAT3 signaling in TH17 development and TH17-dependent autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 179, 4313–4317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang X. O., Panopoulos A. D., Nurieva R., Chang S. H., Wang D., Watowich S. S., Dong C. (2007) STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9358–9363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Korn T., Bettelli E., Gao W., Awasthi A., Jager A., Strom T. B., Oukka M., Kuchroo V. K. (2007) IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature 448, 484–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nurieva R., Yang X. O., Martinez G., Zhang Y., Panopoulos A. D., Ma L., Schluns K., Tian Q., Watowich S. S., Jetten A. M., Dong C. (2007) Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature 448, 480–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wei L., Laurence A., Elias K. M., O′Shea J. J. (2007) IL-21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives IL-17 production in a STAT3-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34605–34610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou L., Ivanov I. I., Spolski R., Min R., Shenderov K., Egawa T., Levy D. E., Leonard W. J., Littman D. R. (2007) IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat. Immunol. 8, 967–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Das J., Ren G., Zhang L., Roberts A. I., Zhao X., Bothwell A. L., Van Kaer L., Shi Y., Das G. (2009) Transforming growth factor β is dispensable for the molecular orchestration of Th17 cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2407–2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Santarlasci V., Maggi L., Capone M., Frosali F., Querci V., De Palma R., Liotta F., Cosmi L., Maggi E., Romagnani S., Annuziato F. (2009) TGF-β indirectly favors the development of human Th17 cells by inhibiting Th1 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghoreschi K., Laurence A., Yang X. P., Tato C. M., McGeachy M. J., Konkel J. E., Ramos H. L., Wei L., Davidson T. S., Bouladoux N., et al. (2010) Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-β signaling. Nature 467, 967–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McGeachy M. J., Bak-Jensen K. S., Chen Y., Tato C. M., Blumenschein W., McClanahan T., Cua D. J. (2007) TGF-β and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1390–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang Y., Weiner J., Liu Y., Smith A. J., Huss D. J., Winger R., Peng H., Cravens P. D., Racke M. K., Lovett-Racke A. E. (2009) T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1549–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Acosta-Rodriguez E. V., Napolitani G., Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F. (2007) Interleukins 1β and 6 but not transforming growth factor-β are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 942–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kryczek I., Wei S., Vatan L., Escara-Wilke J., Szeliga W., Keller E. T., Zou W. (2007) Cutting edge: opposite effects of IL-1 and IL-2 on the regulation of IL-17+ T cell pool IL-1 subverts IL-2-mediated suppression. J. Immunol. 179, 1423–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chung Y., Chang S. H., Martinez G. J., Yang X. O., Nurieva R., Kang H. S., Ma L., Watowich S. S., Jetten A. M., Tian Q., Dong C. (2009) Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity 30, 576–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Durant L., Watford W. T., Ramos H. L., Laurence A., Vahedi G., Wei L., Takahashi H., Sun H. W., Kanno Y., Powrie F., O′Shea J. J. (2010) Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity 32, 605–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Beaucoudrey L., Puel A., Filipe-Santos O., Cobat A., Ghandil P., Chrabieh M., Feinberg J., von Bernuth H., Samarina A., Janniere L., et al. (2008) Mutations in STAT3 and IL12RB1 impair the development of human IL-17-producing T cells. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1543–1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma C. S., Chew G. Y., Simpson N., Priyadarshi A., Wong M., Grimbacher B., Fulcher D. A., Tangye S. G., Cook M. C. (2008) Deficiency of Th17 cells in hyper IgE syndrome due to mutations in STAT3. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1551–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milner J. D., Brenchley J. M., Laurence A., Freeman A. F., Hill B. J., Elias K. M., Kanno Y., Spalding C., Elloumi H. Z., Paulson M. L., Davis J., Hsu A., Asher A. I., O′Shea J., Holland S. M., Paul W. E., Douek D. C. (2008) Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature 452, 773–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Renner E. D., Rylaarsdam S., Anover-Sombke S., Rack A. L., Reichenbach J., Carey J. C., Zhu Q., Jansson A. F., Barboza J., Schimke L. F., Leppert M. F., Getz M. M., Seger R. A., Hill H. R., Belohradsky B. H., Torgerson T. R., Ochs H. D. (2008) Novel signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) mutations, reduced T(H)17 cell numbers, and variably defective STAT3 phosphorylation in hyper-IgE syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 122, 181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu X., Lee Y. S., Yu C. R., Egwuagu C. E. (2008) Loss of STAT3 in CD4+ T cells prevents development of experimental autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 180, 6070–6076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elyaman W., Bradshaw E. M., Uyttenhove C., Dardalhon V., Awasthi A., Imitola J., Bettelli E., Oukka M., van Snick J., Renauld J. C., Kuchroo V. K., Khoury S. J. (2009) IL-9 induces differentiation of TH17 cells and enhances function of FoxP3+ natural regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12885–12890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hibbert L., Pflanz S., De Waal Malefyt R., Kastelein R. A. (2003) IL-27 and IFN-α signal via Stat1 and Stat3 and induce T-bet and IL-12Rβ2 in naive T cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 23, 513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pflanz S., Hibbert L., Mattson J., Rosales R., Vaisberg E., Bazan J. F., Phillips J. H., McClanahan T. K., de Waal Malefyt R., Kastelein R. A. (2004) WSX-1 and glycoprotein 130 constitute a signal-transducing receptor for IL-27. J. Immunol. 172, 2225–2231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nishihara M., Ogura H., Ueda N., Tsuruoka M., Kitabayashi C., Tsuji F., Aono H., Ishihara K., Huseby E., Betz U. A., Murakami M., Hirano T. (2007) IL-6-gp130-STAT3 in T cells directs the development of IL-17+ Th with a minimum effect on that of Treg in the steady state. Int. Immunol. 19, 695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Batten M., Li J., Yi S., Kljavin N. M., Danilenko D. M., Lucas S., Lee J., de Sauvage F. J., Ghilardi N. (2006) Interleukin 27 limits autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the development of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat. Immunol. 7, 929–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stumhofer J. S., Laurence A., Wilson E. H., Huang E., Tato C. M., Johnson L. M., Villarino A. V., Huang Q., Yoshimura A., Sehy D., Saris C. J., O′Shea J. J., Hennighausen L., Ernst M., Hunter C. A. (2006) Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat. Immunol. 7, 937–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoshimura T., Takeda A., Hamano S., Miyazaki Y., Kinjyo I., Ishibashi T., Yoshimura A., Yoshida H. (2006) Two-sided roles of IL-27: induction of Th1 differentiation on naive CD4+ T cells versus suppression of proinflammatory cytokine production including IL-23-induced IL-17 on activated CD4+ T cells partially through STAT3-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 177, 5377–5385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stritesky G. L., Muthukrishnan R., Sehra S., Goswami R., Pham D., Travers J., Nguyen E. T., Levy D. E., Kaplan M. H. (2011) The transcription factor STAT3 is required for T helper 2 cell development. Immunity 34, 39–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chaudhry A., Rudra D., Treuting P., Samstein R. M., Liang Y., Kas A., Rudensky A. Y. (2009) CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science 326, 986–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huber M., Heink S., Grothe H., Guralnik A., Reinhard K., Elflein K., Hunig T., Mittrucker H. W., Brustle A., Kamradt T., Lohoff M. (2009) A Th17-like developmental process leads to CD8(+) Tc17 cells with reduced cytotoxic activity. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 1716–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yen H. R., Harris T. J., Wada S., Grosso J. F., Getnet D., Goldberg M. V., Liang K. L., Bruno T. C., Pyle K. J., Chan S. L., Anders R. A., Trimble C. L., Adler A. J., Lin T. Y., Pardoll D. M., Huang C. T., Drake C. G. (2009) Tc17 CD8 T cells: functional plasticity and subset diversity. J. Immunol. 183, 7161–7168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tanaka S., Yoshimoto T., Naka T., Nakae S., Iwakura Y., Cua D., Kubo M. (2009) Natural occurring IL-17 producing T cells regulate the initial phase of neutrophil mediated airway responses. J. Immunol. 183, 7523–7530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cerf-Bensussan N., Gaboriau-Routhiau V. (2010) The immune system and the gut microbiota: friends or foes? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 735–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Atarashi K., Nishimura J., Shima T., Umesaki Y., Yamamoto M., Onoue M., Yagita H., Ishii N., Evans R., Honda K., Takeda K. (2008) ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature 455, 808–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hall J. A., Bouladoux N., Sun C. M., Wohlfert E. A., Blank R. B., Zhu Q., Grigg M. E., Berzofsky J. A., Belkaid Y. (2008) Commensal DNA limits regulatory T cell conversion and is a natural adjuvant of intestinal immune responses. Immunity 29, 637–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ivanov I. I., Frutos Rde L., Manel N., Yoshinaga K., Rifkin D. B., Sartor R. B., Finlay B. B., Littman D. R. (2008) Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe 4, 337–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Niess J. H., Leithauser F., Adler G., Reimann J. (2008) Commensal gut flora drives the expansion of proinflammatory CD4 T cells in the colonic lamina propria under normal and inflammatory conditions. J. Immunol. 180, 559–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gaboriau-Routhiau V., Rakotobe S., Lecuyer E., Mulder I., Lan A., Bridonneau C., Rochet V., Pisi A., De Paepe M., Brandi G., Eberl G., Snel J., Kelly D., Cerf-Bensussan N. (2009) The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity 31, 677–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ivanov I. I., Atarashi K., Manel N., Brodie E. L., Shima T., Karaoz U., Wei D., Goldfarb K. C., Santee C. A., Lynch S. V., Tanoue T., Imaoka A., Itoh K., Takeda K., Umesaki Y., Honda K., Littman D. R. (2009) Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 139, 485–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Davis C. P., Savage D. C. (1974) Habitat, succession, attachment, and morphology of segmented, filamentous microbes indigenous to the murine gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 10, 948–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Klaasen H. L., Koopman J. P., Van den Brink M. E., Van Wezel H. P., Beynen A. C. (1991) Mono-association of mice with non-cultivable, intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 156, 148–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klaasen H. L., Koopman J. P., Van den Brink M. E., Bakker M. H., Poelma F. G., Beynen A. C. (1993) Intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria in a wide range of vertebrate species. Lab. Anim. 27, 141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Urdaci M. C., Regnault B., Grimont P. A. (2001) Identification by in situ hybridization of segmented filamentous bacteria in the intestine of diarrheic rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Res. Microbiol. 152, 67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jepson M. A., Clark M. A., Simmons N. L., Hirst B. H. (1993) Actin accumulation at sites of attachment of indigenous apathogenic segmented filamentous bacteria to mouse ileal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 61, 4001–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Klaasen H. L., Van der Heijden P. J., Stok W., Poelma F. G., Koopman J. P., Van den Brink M. E., Bakker M. H., Eling W. M., Beynen A. C. (1993) Apathogenic, intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria stimulate the mucosal immune system of mice. Infect. Immun. 61, 303–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee Y. K., Menezes J. S., Umesaki Y., Mazmanian S. K. (2011) Microbes and health sackler colloquium: proinflammatory T-cell responses to gut microbiota promote experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4615–4622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu H. J., Ivanov I. I., Darce J., Hattori K., Shima T., Umesaki Y., Littman D. R., Benoist C., Mathis D. (2010) Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity 32, 815–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Shima T., Imaoka A., Kuwahara T., Momose Y., Cheng G., Yamasaki S., Saito T., Ohba Y., Taniguchi T., Takeda K., Hori S., Ivanov I. I., Umesaki Y., Itoh K., Honda K. (2011) Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science 331, 337–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Esser C., Rannug A., Stockinger B. (2009) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in immunity. Trends Immunol. 30, 447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Singh K. P., Casado F. L., Opanashuk L. A., Gasiewicz T. A. (2009) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor has a normal function in the regulation of hematopoietic and other stem/progenitor cell populations. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 577–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Apetoh L., Quintana F. J., Pot C., Joller N., Xiao S., Kumar D., Burns E. J., Sherr D. H., Weiner H. L., Kuchroo V. K. (2010) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c-Maf to promote the differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL-27. Nat. Immunol. 11, 854–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Quintana F. J., Basso A. S., Iglesias A. H., Korn T., Farez M. F., Bettelli E., Caccamo M., Oukka M., Weiner H. L. (2008) Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 453, 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gandhi R., Kumar D., Burns E. J., Nadeau M., Dake B., Laroni A., Kozoriz D., Weiner H. L., Quintana F. J. (2010) Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces human type 1 regulatory T cell-like and Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 11, 846–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Quintana F. J., Murugaiyan G., Farez M. F., Mitsdoerffer M., Tukpah A. M., Burns E. J., Weiner H. L. (2010) An endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand acts on dendritic cells and T cells to suppress experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20768–20773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang L., Ma J., Takeuchi M., Usui Y., Hattori T., Okunuki Y., Yamakawa N., Kezuka T., Kuroda M., Goto H. (2010) Suppression of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis by inducing differentiation of regulatory T cells via activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 2109–2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Funatake C. J., Marshall N. B., Steppan L. B., Mourich D. V., Kerkvliet N. I. (2005) Cutting edge: activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin generates a population of CD4+ CD25+ cells with characteristics of regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 175, 4184–4188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Veldhoen M., Hirota K., Christensen J., O′Garra A., Stockinger B. (2009) Natural agonists for aryl hydrocarbon receptor in culture medium are essential for optimal differentiation of Th17 T cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 43–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kimura A., Naka T., Nohara K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kishimoto T. (2008) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates Stat1 activation and participates in the development of Th17 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9721–9726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Veldhoen M., Hirota K., Westendorf A. M., Buer J., Dumoutier L., Renauld J. C., Stockinger B. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453, 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Alam M. S., Maekawa Y., Kitamura A., Tanigaki K., Yoshimoto T., Kishihara K., Yasutomo K. (2010) Notch signaling drives IL-22 secretion in CD4+ T cells by stimulating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5943–5948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ramirez J. M., Brembilla N. C., Sorg O., Chicheportiche R., Matthes T., Dayer J. M., Saurat J. H., Roosnek E., Chizzolini C. (2010) Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor reveals distinct requirements for IL-22 and IL-17 production by human T helper cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 2450–2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Trifari S., Kaplan C. D., Tran E. H., Crellin N. K., Spits H. (2009) Identification of a human helper T cell population that has abundant production of interleukin 22 and is distinct from T(H)-17, T(H)1 and T(H)2 cells. Nat. Immunol. 10, 864–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Martin B., Hirota K., Cua D. J., Stockinger B., Veldhoen M. (2009) Interleukin-17-producing γδ T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity 31, 321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hughes T., Becknell B., Freud A. G., McClory S., Briercheck E., Yu J., Mao C., Giovenzana C., Nuovo G., Wei L., Zhang X., Gavrilin M. A., Wewers M. D., Caligiuri M. A. (2010) Interleukin-1β selectively expands and sustains interleukin-22+ immature human natural killer cells in secondary lymphoid tissue. Immunity 32, 803–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mucida D., Park Y., Kim G., Turovskaya O., Scott I., Kronenberg M., Cheroutre H. (2007) Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science 317, 256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Osorio F., LeibundGut-Landmann S., Lochner M., Lahl K., Sparwasser T., Eberl G., Reis e Sousa C. (2008) DC activated via dectin-1 convert Treg into IL-17 producers. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 3274–3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yang X. O., Nurieva R., Martinez G. J., Kang H. S., Chung Y., Pappu B. P., Shah B., Chang S. H., Schluns K. S., Watowich S. S., Feng X. H., Jetten A. M., Dong C. (2008) Molecular antagonism and plasticity of regulatory and inflammatory T cell programs. Immunity 29, 44–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lochner M., Peduto L., Cherrier M., Sawa S., Langa F., Varona R., Riethmacher D., Si-Tahar M., Di Santo J. P., Eberl G. (2008) In vivo equilibrium of proinflammatory IL-17+ and regulatory IL-10+ Foxp3+ RORγ t+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1381–1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhou L., Lopes J. E., Chong M. M., Ivanov I. I., Min R., Victora G. D., Shen Y., Du J., Rubtsov Y. P., Rudensky A. Y., Ziegler S. F., Littman D. R. (2008) TGF-β-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature 453, 236–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tartar D. M., VanMorlan A. M., Wan X., Guloglu F. B., Jain R., Haymaker C. L., Ellis J. S., Hoeman C. M., Cascio J. A., Dhakal M., Oukka M., Zaghouani H. (2010) FoxP3+RORγt+ T helper intermediates display suppressive function against autoimmune diabetes. J. Immunol. 184, 3377–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Voo K. S., Wang Y. H., Santori F. R., Boggiano C., Arima K., Bover L., Hanabuchi S., Khalili J., Marinova E., Zheng B., Littman D. R., Liu Y. J. (2009) Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4793–4798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lexberg M. H., Taubner A., Forster A., Albrecht I., Richter A., Kamradt T., Radbruch A., Chang H. D. (2008) Th memory for interleukin-17 expression is stable in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 2654–2664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nurieva R., Yang X. O., Chung Y., Dong C. (2009) Cutting edge: in vitro generated Th17 cells maintain their cytokine expression program in normal but not lymphopenic hosts. J. Immunol. 182, 2565–2568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lexberg M. H., Taubner A., Albrecht I., Lepenies I., Richter A., Kamradt T., Radbruch A., Chang H. D. (2010) IFN-γ and IL-12 synergize to convert in vivo generated Th17 into Th1/Th17 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 3017–3027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lee Y. K., Turner H., Maynard C. L., Oliver J. R., Chen D., Elson C. O., Weaver C. T. (2009) Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity 30, 92–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Nistala K., Adams S., Cambrook H., Ursu S., Olivito B., de Jager W., Evans J. G., Cimaz R., Bajaj-Elliott M., Wedderburn L. R. (2010) Th17 plasticity in human autoimmune arthritis is driven by the inflammatory environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14751–14756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bending D., De La Pena H., Veldhoen M., Phillips J. M., Uyttenhove C., Stockinger B., Cooke A. (2009) Highly purified Th17 cells from BDC2.5NOD mice convert into Th1-like cells in NOD/SCID recipient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 565–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Akimzhanov A. M., Yang X. O., Dong C. (2007) Chromatin remodeling of interleukin-17 (IL-17)-IL-17F cytokine gene locus during inflammatory helper T cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5969–5972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Koenen H. J., Smeets R. L., Vink P. M., van Rijssen E., Boots A. M., Joosten I. (2008) Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood 112, 2340–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Wei G., Wei L., Zhu J., Zang C., Hu-Li J., Yao Z., Cui K., Kanno Y., Roh T. Y., Watford W. T., Schones D. E., Peng W., Sun H. W., Paul W. E., O′Shea J. J., Zhao K. (2009) Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity 30, 155–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mukasa R., Balasubramani A., Lee Y. K., Whitley S. K., Weaver B. T., Shibata Y., Crawford G. E., Hatton R. D., Weaver C. T. (2010) Epigenetic instability of cytokine and transcription factor gene loci underlies plasticity of the T helper 17 cell lineage. Immunity 32, 616–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Weaver C. T., Hatton R. D., Mangan P. R., Harrington L. E. (2007) IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 821–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Fossiez F., Djossou O., Chomarat P., Flores-Romo L., Ait-Yahia S., Maat C., Pin J. J., Garrone P., Garcia E., Saeland S., et al. (1996) T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 183, 2593–2603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wolk K., Kunz S., Asadullah K., Sabat R. (2002) Cutting edge: immune cells as sources and targets of the IL-10 family members? J. Immunol. 168, 5397–5402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wolk K., Witte E., Witte K., Warszawska K., Sabat R. (2010) Biology of interleukin-22. Semin. Immunopathol. 32, 17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hue S., Ahern P., Buonocore S., Kullberg M. C., Cua D. J., McKenzie B. S., Powrie F., Maloy K. J. (2006) Interleukin-23 drives innate and T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2473–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ferretti S., Bonneau O., Dubois G. R., Jones C. E., Trifilieff A. (2003) IL-17, produced by lymphocytes and neutrophils, is necessary for lipopolysaccharide-induced airway neutrophilia: IL-15 as a possible trigger. J. Immunol. 170, 2106–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Li L., Huang L., Vergis A. L., Ye H., Bajwa A., Narayan V., Strieter R. M., Rosin D. L., Okusa M. D. (2010) IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-γ-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 331–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hoshino A., Nagao T., Nagi-Miura N., Ohno N., Yasuhara M., Yamamoto K., Nakayama T., Suzuki K. (2008) MPO-ANCA induces IL-17 production by activated neutrophils in vitro via classical complement pathway-dependent manner. J. Autoimmun. 31, 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Da Silva C. A., Hartl D., Liu W., Lee C. G., Elias J. A. (2008) TLR-2 and IL-17A in chitin-induced macrophage activation and acute inflammation. J. Immunol. 181, 4279–4286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Cua D. J., Tato C. M. (2010) Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Van Maele L., Carnoy C., Cayet D., Songhet P., Dumoutier L., Ferrero I., Janot L., Erard F., Bertout J., Leger H., Sebbane F., Benecke A., Renauld J. C., Hardt W. D., Ryffel B., Sirard J. C. (2010) TLR5 signaling stimulates the innate production of IL-17 and IL-22 by CD3(neg)CD127+ immune cells in spleen and mucosa. J. Immunol. 185, 1177–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Takatori H., Kanno Y., Watford W. T., Tato C. M., Weiss G., Ivanov I. I., Littman D. R., O′Shea J. J. (2009) Lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells are an innate source of IL-17 and IL-22. J. Exp. Med. 206, 35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sonnenberg G. F., Monticelli L. A., Elloso M. M., Fouser L. A., Artis D. (2011) CD4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. Immunity 34, 122–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Satoh-Takayama N., Vosshenrich C. A., Lesjean-Pottier S., Sawa S., Lochner M., Rattis F., Mention J. J., Thiam K., Cerf-Bensussan N., Mandelboim O., Eberl G., Di Santo J. P. (2008) Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity 29, 958–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Cella M., Fuchs A., Vermi W., Facchetti F., Otero K., Lennerz J. K., Doherty J. M., Mills J. C., Colonna M. (2009) A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature 457, 722–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Buonocore S., Ahern P. P., Uhlig H. H., Ivanov I. I., Littman D. R., Maloy K. J., Powrie F. (2010) Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature 464, 1371–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Doisne J. M., Soulard V., Becourt C., Amniai L., Henrot P., Havenar-Daughton C., Blanchet C., Zitvogel L., Ryffel B., Cavaillon J. M., Marie J. C., Couillin I., Benlagha K. (2011) Cutting edge: crucial role of IL-1 and IL-23 in the innate IL-17 response of peripheral lymph node NK1.1-invariant NKT cells to bacteria. J. Immunol. 186, 662–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sutton C. E., Lalor S. J., Sweeney C. M., Brereton C. F., Lavelle E. C., Mills K. H. (2009) Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from γδ T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity 31, 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Uhlig H. H., McKenzie B. S., Hue S., Thompson C., Joyce-Shaikh B., Stepankova R., Robinson N., Buonocore S., Tlaskalova-Hogenova H., Cua D. J., Powrie F. (2006) Differential activity of IL-12 and IL-23 in mucosal and systemic innate immune pathology. Immunity 25, 309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Tsuji M., Suzuki K., Kitamura H., Maruya M., Kinoshita K., Ivanov I. I., Itoh K., Littman D. R., Fagarasan S. (2008) Requirement for lymphoid tissue-inducer cells in isolated follicle formation and T cell-independent immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity 29, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Schwarzenberger P., La Russa V., Miller A., Ye P., Huang W., Zieske A., Nelson S., Bagby G. J., Stoltz D., Mynatt R. L., Spriggs M., Kolls J. K. (1998) IL-17 stimulates granulopoiesis in mice: use of an alternate, novel gene therapy-derived method for in vivo evaluation of cytokines. J. Immunol. 161, 6383–6389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Schwarzenberger P., Huang W., Ye P., Oliver P., Manuel M., Zhang Z., Bagby G., Nelson S., Kolls J. K. (2000) Requirement of endogenous stem cell factor and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor for IL-17-mediated granulopoiesis. J. Immunol. 164, 4783–4789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Tan W., Huang W., Zhong Q., Schwarzenberger P. (2006) IL-17 receptor knockout mice have enhanced myelotoxicity and impaired hemopoietic recovery following γ irradiation. J. Immunol. 176, 6186–6193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Laan M., Cui Z. H., Hoshino H., Lotvall J., Sjostrand M., Gruenert D. C., Skoogh B. E., Linden A. (1999) Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J. Immunol. 162, 2347–2352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ye P., Rodriguez F. H., Kanaly S., Stocking K. L., Schurr J., Schwarzenberger P., Oliver P., Huang W., Zhang P., Zhang J., Shellito J. E., Bagby G. J., Nelson S., Charrier K., Peschon J. J., Kolls J. K. (2001) Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J. Exp. Med. 194, 519–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Witowski J., Pawlaczyk K., Breborowicz A., Scheuren A., Kuzlan-Pawlaczyk M., Wisniewska J., Polubinska A., Friess H., Gahl G. M., Frei U., Jörres A. (2000) IL-17 stimulates intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO α chemokine from mesothelial cells. J. Immunol. 165, 5814–5821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Kreindler J. L., Bertrand C. A., Lee R. J., Karasic T., Aujla S., Pilewski J. M., Frizzell R. A., Kolls J. K. (2009) Interleukin-17A induces bicarbonate secretion in normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 296, L257–L266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Dorschner R. A., Lopez-Garcia B., Peschel A., Kraus D., Morikawa K., Nizet V., Gallo R. L. (2006) The mammalian ionic environment dictates microbial susceptibility to antimicrobial defense peptides. FASEB J. 20, 35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Dubin P. J., Kolls J. K. (2008) Th17 cytokines and mucosal immunity. Immunol. Rev. 226, 160–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Nakae S., Komiyama Y., Nambu A., Sudo K., Iwase M., Homma I., Sekikawa K., Asano M., Iwakura Y. (2002) Antigen-specific T cell sensitization is impaired in IL-17-deficient mice, causing suppression of allergic cellular and humoral responses. Immunity 17, 375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Ghilardi N., Kljavin N., Chen Q., Lucas S., Gurney A. L., De Sauvage F. J. (2004) Compromised humoral and delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in IL-23-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 172, 2827–2833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Milovanovic M., Drozdenko G., Weise C., Babina M., Worm M. (2010) Interleukin-17A promotes IgE production in human B cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 2621–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Doreau A., Belot A., Bastid J., Riche B., Trescol-Biemont M. C., Ranchin B., Fabien N., Cochat P., Pouteil-Noble C., Trolliet P., Durieu I., Tebib J., Kesai B., Ansieau S., Puisieux A., Eliaou J. F., Bonnefoy-Bérard M. (2009) Interleukin 17 acts in synergy with B cell-activating factor to influence B cell biology and the pathophysiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Immunol. 10, 778–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Jaffar Z., Ferrini M. E., Herritt L. A., Roberts K. (2009) Cutting edge: lung mucosal Th17-mediated responses induce polymeric Ig receptor expression by the airway epithelium and elevate secretory IgA levels. J. Immunol. 182, 4507–4511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Gaffen S. L. (2009) Structure and signaling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 556–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Ishigame H., Kakuta S., Nagai T., Kadoki M., Nambu A., Komiyama Y., Fujikado N., Tanahashi Y., Akitsu A., Kotaki H., Sudo K., Nakae S., Sasakawa C., Iwakura Y. (2009) Differential roles of interleukin-17A and -17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity 30, 108–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Aujla S. J., Chan Y. R., Zheng M., Fei M., Askew D. J., Pociask D. A., Reinhart T. A., McAllister F., Edeal J., Gaus K., et al. (2008) IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 14, 275–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Zheng Y., Valdez P. A., Danilenko D. M., Hu Y., Sa S. M., Gong Q., Abbas A. R., Modrusan Z., Ghilardi N., de Sauvage F. J., Ouyang W. (2008) Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat. Med. 14, 282–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Wilson M. S., Feng C. G., Barber D. L., Yarovinsky F., Cheever A. W., Sher A., Grigg M., Collins M., Fouser L., Wynn T. A. (2010) Redundant and pathogenic roles for IL-22 in mycobacterial, protozoan, and helminth infections. J. Immunol. 184, 4378–4390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Raffatellu M., Santos R. L., Verhoeven D. E., George M. D., Wilson R. P., Winter S. E., Godinez I., Sankaran S., Paixao T. A., Gordon M. A., Kolls J. K., Dandekar S, Baumler A. J. (2008) Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat. Med. 14, 421–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Pepper M., Linehan J. L., Pagan A. J., Zell T., Dileepan T., Cleary P. P., Jenkins M. K. (2010) Different routes of bacterial infection induce long-lived TH1 memory cells and short-lived TH17 cells. Nat. Immunol. 11, 83–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Khader S. A., Bell G. K., Pearl J. E., Fountain J. J., Rangel-Moreno J., Cilley G. E., Shen F., Eaton S. M., Gaffen S. L., Swain S. L., Locksley R. M., Haynes L., Randall T. D., Cooper A. M. (2007) IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat. Immunol. 8, 369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Lin Y., Ritchea S., Logar A., Slight S., Messmer M., Rangel-Moreno J., Guglani L., Alcorn J. F., Strawbridge H., Park S. M., et al. (2009) Interleukin-17 is required for T helper 1 cell immunity and host resistance to the intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis. Immunity 31, 799–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]