Abstract

The burden of diabetes and obesity is increasing worldwide, indicating a need to find the best standard for diabetes care. The aim of this study was to generate a theory grounded in empirical data derived from a deeper understanding of health care professionals’ main concerns when they consult with individuals with diabetes and obesity and how they handle these concerns. Tape-recorded interviews were conducted with seven groups and three individual members of a diabetes team in an area of western Sweden. The grounded theory (GT) method was used to analyse the transcribed interviews. A core category, labelled Balancing coaching and caution and three categories (Coaching and supporting, Ambivalence and uncertainty, and Adjusting intentions) emerged. The core category and the three categories formed a substantive theory that explained and illuminated how health care professionals manage their main concern; their ambition to give professional individualised care; and find the right strategy for each individual with diabetes and obesity. The theory generated by this study can improve our understanding of how a lack of workable strategies limits caregivers’ abilities to reach their goals. It also helps identify the factors that contribute to the complexity of meetings between caregivers and individuals with diabetes.

Keywords: Care meeting, coaching, diabetes Type 2, grounded theory, health care professional, obesity

The burden of diabetes is increasing worldwide, indicating an urgent need to find the best standard for diabetes care (Funnell, 2004). There is a close relationship between obesity and Type 2 diabetes: 90% of individuals with diabetes are overweight or obese. The basic treatment is weight loss, physical activity, and diet (Haslam, 2010). Although there are many alternative therapies including lifestyle changes and medical treatment, two-thirds of people with diabetes do not reach an acceptable level of metabolic control resulting in an increased risk of serious complications (McGill & Felton, 2007).

Developments in diabetes care including new technologies and new medical treatments have been highlighted, along with the importance of mental well-being (Funnell, 2004). Many barriers need to be overcome to achieve development in health care practice (King & Kelly, 2011) and health care professionals’ attitudes have shifted from compliance-seeking and the traditional physician-led care to a model in which all team members including the individuals with diabetes play an active role, resulting in increased empowerment. One of the main factors in providing quality care and treatment in diabetes is securing the individual's active participation in self-care and care decisions (McGill & Felton, 2007) and communication and reflection play an important role (Zoffmann, Harder, & Kirkevold, 2008).

When health care professionals communicate with individuals with diabetes about how to handle the illness in daily life, it can be very effective; however, health care professionals tend to focus on medications and medical risk factors rather than on the individual's feelings and ability to apply knowledge to improve his/her quality of life (Funnell, 2004). The disconnection between medical goals and individuals’ daily lives can create conflicts and frustration for both professionals (Hornsten, Lundman, Almberg, & Sandström, 2008) and individuals with diabetes (Svenningsson, Gedda, & Marklund, 2011b). Integrating the disease into normal life is essential if individuals with diabetes are to achieve glycaemic control; unfortunately, this process is not always actively supported by health care professionals. When professionals and individuals with diabetes are unable to agree on actions that integrate the disease into individuals’ daily lives, both parties are disempowered (Zoffmann & Kirkevold, 2005).

Having obesity as well as diabetes presents an additional health care burden for the individual (Sundaram et al., 2007; Svenningsson, Attvall, Marklund, & Gedda, 2011a), and little is known about how obesity (Tsai & Wadden, 2009) with diabetes should be treated in primary care. Health care professionals often feel that they have inadequate time for and knowledge about successful weight loss counselling (Huang et al., 2004) and feel frustrated by these obstacles. Individuals with diabetes also feel frustrated by the difficulties associated with self-care (Funnell, 2004). For the overweight or obese, weight loss is not often discussed in care meetings, and individuals perceive a lack of support in weight loss management (Potter, Vu, & Croughan-Minihane, 2001). The extra emotional burden of being both obese and having diabetes has to be considered by health care professionals in individual care meetings (Svenningsson et al., 2011a).

A literature review revealed a lack of knowledge about what goes on in health care meetings between individuals with both diabetes and obesity and health care professionals.

The aim of this study was to generate a theory grounded in empirical data derived from a deeper understanding of health care professionals’ main concerns when they consult with individuals with both diabetes and obesity and how they handle these concerns.

Methods

Design

The method that was considered appropriate for this study was the classical version of grounded theory (GT; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The method aims to inductively produce new knowledge to generate concepts, models, or theories that explain what is happening in the studied area. This is achieved by systematically and continually comparing and examining the variations and similarities of and the differences between codes, categories, attributes, and sets of empirical data (Hallberg, 2006). The classical version of GT seems to be closely positioned to positivism, although Glaser and Strauss never declared their epistemological standpoints explicitly (Hallberg, 2006). The first author of this study (IS) is a registered nurse specialising in diabetes care with ample research experience in this area. The author's interest in diabetes care arose from her experience with the difficulties people with diabetes and obesity have with weight loss; she found that the situation was difficult for both individuals and health care professionals, e.g., nurses. This indicated a need for a better understanding of the main needs of the situation, and a qualitative approach seemed to offer the tools necessary to find new angles on the problem. To ensure that the first author's preconceptions would not affect the research process, reflexivity was used continuously throughout the process (Malterud, 2001).

Sampling procedure and study participant

This study was based on interviews with health care professionals who work with individuals with diabetes in health care settings. To examine health care professionals’ experiences in health care meetings with individuals with Type 2 diabetes and obesity, we selected diabetes teams in primary health care and county medical care settings in an area in western Sweden. We sought a maximum variation of experiences (Hallberg, 2006) by choosing caregivers and professionals from different disciplines as informants; that is, open sampling was used initially and followed later by theoretical sampling. We conducted seven group interviews and three individual interviews to deepen and enrich the data (Table 1). After seven interviews, signs of similarities in the information appeared; however, another three interviews were conducted to reach saturation. All informants had more than 15 years experience as health care professionals. Data collection was conducted during 2009–2010.

Table 1.

The informants.

| Interview | Nurses | Physicians | Dieticians | Physiotherapist |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 3 | |||

| 3 | 1 | |||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 8 | 1 | |||

| 9 | 2 | |||

| 10 | 1 |

The interviews were transcribed by the first author (IS), who conducted the group interviews along with the second author (BG). The individual interviews were conducted by the first author only (IS). The interviews took place at each informant's workplace during his/her working hours. Each interview lasted between 30 min and 1 h. During the interviews, the first author introduced the interview themes and the second author observed group interactions and took notes. The initial questions asked in the interviews were: What approaches do care providers generally use when meeting individuals with Type 2 diabetes and obesity? What do care providers intend to achieve with their strategies? What facts and ideas are these strategies based on? What is the result and the outcome of the strategies? Do care providers use different strategies for men and women with diabetes and obesity? When relevant, probing and follow-up questions were posed during the interviews. Accordingly, the interviews began with broad questions, which became more specific throughout the interviews and during analysis (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Theoretical sampling, which means that emerging results guided further questioning, was used to receive “thick descriptions” and data saturation. Data collection continued until theoretical saturation was reached, meaning that new data did not provide new information about the emerging categories (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Hallberg, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Data analysis

The analysis of the interviews took place as soon as each interview was transcribed, in accordance with the guidelines for GT (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Initially, each interview was read through to gain a sense of the wholeness of the content and its meaning. During the initial coding, which was done line-by-line close to the data, actions were identified and compared. By using the informants’ words, we ensured that these codes were grounded in the data. Codes with similar meanings were then grouped together to form comprehensive categories, which were labelled on a more abstract level. Data were compared with data and categories with categories to develop their properties (subcategories). In the third step, the relationships between the categories were sought and organised into an emerging theory. Throughout the process, codes and preliminary categories were compared, modified, and eventually given new names. Memos were written throughout the process to develop the analyses and the emerging theory. When a core category was identified, theoretical sampling was used to saturate related categories explaining how the main concern was managed. Theoretical sampling can be conducted by returning to previously collected data for further analysis and/or by conducting additional interviews. The first author (IS) conducted the first phase of the analysis, and codes, categories, and emerging theories were continually discussed with BG and LH.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (406–08). The participants were informed about the aim and procedure of the study and were invited to participate. They were also informed about the voluntary nature of participating in the study and their right to terminate their participation at any time without providing a reason.

Results

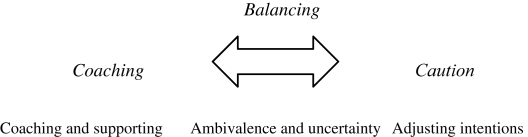

The analysis showed that the main concern for health care professionals in the diabetes team is their ambition to provide professional care; that is, to provide individualised care and find the right strategy for each individual with diabetes and obesity. This is achieved by “balancing coaching and caution,” which was identified as the core category in the data (see Fig. 1). This core category was related to three categories, each associated with several subcategories, forming a pattern of behaviour that further explained how the main concern was handled. The three categories were labelled “Coaching and supporting,” “Ambivalence and uncertainty,” and “Adjusting intentions.” The core category and the three categories formed a substantive theory that explained how health care professionals in the diabetes team managed their goal of providing professional care and finding the right strategy for each individual with diabetes and obesity.

Figure 1.

The main concern of health care professionals caring for people with diabetes and obesity is to provide individualised and helpful care. This is achieved by balancing coaching and caution.

Balancing coaching and caution (core category)

“Balancing coaching and caution” explores how the the main concern of care providers was managed during meetings with individuals with diabetes and obesity. According to the data, this includes a strong feeling of responsibility and an unspoken need to be successful in achieving weight loss for the individual with diabetes and obesity, due to professionality and a determination to contribute to lifestyle changes, better metabolic control, and weight loss. The health care professionals’ approach is to urgently coach, assist, and support individuals rather than to give up in response to resistance and the obstacles that individuals with diabetes and obesity can present. Based on their professional knowledge and experience, the health care professionals’ task is to guide each individual to a better health situation and, at the same time, seriously consider the individual's perspective and his/her situation and resources. This includes proposing the measures that need to be taken, suggesting approaches to achieve the desired results and explaining the link between individuals’ actions and their health. The health care professionals’ experiences have taught them that this is a most difficult task and successfully supporting the individual to change his/her lifestyle is a challenge. The care providers are balancing coaching and caution and are trying and testing different strategies based on the needs and capacities of each individual case, knowing that there is no general rule for success.

Coaching and supporting

This category, related to the subcategories “a professional challenge,” “helping the individuals to see their own potential for progress,” and “highlighting any progress towards the goal” describes strategies health care professionals use in their struggle to provide individualised care. The interviews showed that health care professionals genuinely tried to take a coaching and supporting approach to increase the individuals’ ability to lose weight. The premise is that every person can be successful in losing weight, achieve better metabolic control, and reduce the risk of disease-related complications. Health care professionals strive for a holistic approach, in which the individual is central and medical skills are synchronised with care. This requires collaborating with the individual, who guides the agenda according to his/her unique situation, needs, knowledge, and special requirements.

A professional challenge

According to the data, coaching and supporting individuals with diabetes and obesity is a professional challenge. The intention is that the strategy the professionals choose should be based on what they think will be helpful and what the obese diabetic individual can accept. This includes describing the steps that need to be taken, explaining the links between actions and results, and affirming the individual's promising steps towards a healthier lifestyle and a reduction in body weight. The challenge for the professionals was that in their consultations, it was difficult to find coaching and supporting strategies that simultaneously increase the individual's incentive to take actions that allow him/her to lose weight, avoid being intrusive, and remain open and concrete without lecturing. The informants found that many individuals with diabetes and obesity are not aware of the risks associated with their condition, and that men and women might require different coaching and supporting strategies. To achieve this, the individual's autonomy should be in focus as professionals try to guide him/her in the most convenient way without threatening his/her integrity. Quotes from the interviews below illustrate this professional challenge:

It's not a matter for me to determine how they should live their lives.

Yes, they know that they should not take this piece of pastry but then they cannot resist it; but if I say that if you replace the piece of pastry and take a bun instead and avoid the cream // but they don't think it is enough because they want to lose 10 kilograms in one week. Sometimes they do not understand the risks of continuing their present lifestyle.

Helping individuals see their own potential for progress and change

The health professionals’ assumption is that each individual has the potential for change, and their main task is to help the individual to find this potential. To achieve this, the professionals attempt to motivate and teach the individuals to adopt lifestyle changes by improving their understanding of how lifestyle changes affect the disease. The professionals provide individual- and situation-specific advice, and their philosophy is that there is always an opportunity for change, no matter the individual's situation. According to the informants, their strategies include pointing out each individual's unique skills, focusing on disease and behaviour change, and educating individuals about physiological processes in the body. The health care professionals intend to improve the individuals’ understanding to help them recognise their potential for change. The professionals understand that there are different conditions among individuals with diabetes and obesity, and that they must respond to this by finding ways to overcome obstacles and help the individual become aware of his/her options. To achieve this, professionals must balance their knowledge of what the situation demands with what is possible for the individual to do; they must balance providing guidelines with waiting for the individual's own proposals for action. Another balancing act involves determining how to support each individual. With some individuals, the professionals can express their views clearly and straightforwardly; while with others, they must express their message more cautiously.

It is a bit of getting each individual to find their own resources that can be useful and to use what they have within themselves to think in a certain way, act in a certain way, and they have the resources within themselves but they might not be aware of it.

Highlighting any progress towards the goal

The informants expressed that a major goal in their meetings with individuals with diabetes and obesity was to help him/her reduce body weight. Their experience has shown that weight loss is a lengthy process for which the individual must take responsibility; the professionals will not abandon the individual during this process, even if it takes several years. The health care professionals know that obesity combined with diabetes provides an extra burden, but they have to balance the weight discussion to avoid losing sight of the individual's needs. The health care professionals’ strategy for achieving this was to confirm and applaud even small amounts of progress to show the individual the value of any lifestyle change and motivate him/her to continue these positive changes, even when the individual failed to lose weight. A common recurring comment among the interviewed health care professionals was that it is important not to get caught up in the weight loss issue. Instead, it is important to acknowledge that the individual has really tried to change his/her lifestyle habits and acknowledge the changes he/she has managed. Otherwise, he/she may get a feeling of failure and abandon his/her life style changes. This strategy is considered a balancing act between what the professional's experience has shown to be the best way to handle the situation and what will improve the individual's condition and motivation: a little physical exercise is better than nothing.

Whatever they do, it is better than nothing. // And I understand that they cannot exercise those 30 minutes. Whatever they do, it is better to try to motivate them that a little is better than nothing.

To listen and feel is important. We must not talk about a lot of things that the patient does not want to hear, while we have to look to find out what they need to know. There is a balance there.

Ambivalence and uncertainty

The second strategy, “ambivalence and uncertainty,” includes the subcategories “experiment with insecurity” and “feelings of failure” and describes how health care professionals handle the dilemma when the obese person with diabetes has not achieved the necessary lifestyle changes despite all the professional's attempts.

Experiment with insecurity

According to the health care professionals, it is almost impossible to predict which strategy will produce positive results for the individual. Some professionals even doubt whether they have any role at all in a possible success. The most common strategy described in the interviews was “experiment,” because the health care professionals had no access to a general strategy that could lead to a successful outcome. As a result, they have to examine the methods they have at hand, without knowing whether those will help the individual. This implies that working with obese individuals with diabetes is perceived as a large experiment in which professionals do not have access to proven methods or procedures to achieve good results for each individual. At the same time, they have no clear idea over why some individuals with obesity are able to lose weight and others are not. The professionals feel uncertain and have to balance how to communicate their message to the individual so that he/she can acquire new skills and put these skills into practice. When the individual with diabetes and obesity does not lose weight, health care professionals blame themselves and feel guilt and failure.

Now, we do have a number of tools, but how should I use them? // I struggle with it very much // I often feel it // in fact, an agony // and it takes some energy // I wish we had developed ways of working in depth with this. How can I help this patient and understand the seriousness and // and like it is, is there something wrong with my way of communicating?

Whatever it was that made him grasp the problem, I do not know.

Feelings of failure

Health care professionals realise that despite their efforts, many individuals with diabetes and obesity fail to lose weight. This gives the health care professionals a sense of failure and powerlessness, and they blame themselves for not being able to communicate knowledge in a way that makes the individual understand the seriousness in the situation. According to the professionals, they spend a lot of time thinking about how to find workable strategies; however, the dearth of strategies means that there are no easy solutions to the problem. Available tools such as medical treatment, obesity surgery, and physical activity prescriptions are not always successful in the long run. They assume that individuals with obesity and diabetes rarely show their frustration. The question arises about whether it is they, as professional health care professionals, who are the most disappointed and inclined to wonder what is wrong with their tactics. When all their strategies have been exhausted, they feel dejection and failure.

Then I feel that we meet, of course, also people that we cannot reach //we cannot influence them how much we beat our forehead bloody.

Sometimes I feel like why? Why? I say, “It's so clear”; I say “You're young, you need help” and then I can feel, “Oh, God, can I do it in any other way? What am I doing wrong?”

Adjusting intentions

“Adjusting intentions” is the third category, related to the subcategories “cautious participation” and “wishing not to hurt or blame.” This category describes the health care professionals’ strategies when they find that they are unable to progress further in their efforts and trials to contribute to an improved situation for the individual with diabetes and obesity.

Cautious participation

To ensure that the individual does not feel abandoned in his/her failed attempts to lose weight, the professionals consider taking the role of a cautious companion. This means that they change their attitude and provide more passive support for the individual's struggle, sympathising with his/her difficulties, avoiding statements that could destroy their relationship, or that the individual might perceive as offensive. The health care professionals believe that many of the individuals already have poor self-esteem due to their obesity and they do not want to make the situation worse. According to the professionals, this was even more pronounced in meetings with women. The professionals reported that they took a more cautious approach in conversations with women because they believe that women are more emotionally affected by their obesity than men, that they are more vulnerable, feel ashamed, and blame themselves for their obesity. They also stated that women have been upset by unwanted messages, both explicit and implicit, given during health care consultations. As a result, the professionals feel that when they consult with women, they are “walking on eggshells” and must talk about obesity very cautiously to avoid increasing the individuals’ guilt and shame.

Wishing not to hurt or blame

Although the goal is to never stop searching for a solution, the professionals may be forced to abandon the goal of weight loss and adjust their intentions. This can occur, for example, after meeting with an individual year after year and recognising that no weight loss or changes have occurred. One reason for this, according to the health care professionals, is that obesity limits the possibilities for physical activity and, consequently, weight loss is almost impossible. The professionals also mean that individuals’ old habits are so ingrained that it is almost impossible to make a change. The professionals become resigned to the fact that lifestyle changes are unobtainable. To minimise the sense of guilt on both sides, they instead focus on the diabetes, metabolic control, and other problems and factors that the individual can handle, accepting that the individual is giving up on a long-term process that requires a commitment to change habits and lifestyle.

Concretely, when it comes to women, I do not know if it is right, but you do not want in any way to hurt or blame her, even concretely.

Women … maybe they tried to influence their weight before and failed so then. Many guys have not done it until they get here.

To a man, I can say that he is too round in the belly... This, I would never think of saying to a woman.

Discussion

The substantive theory generated in this GT study identified that the main concern for health care professionals meeting with individuals with diabetes and obesity was providing professional care and finding the right strategy for each individual. To achieve this, they balance coaching and caution, which was identified as the core category. This core category is related to a pattern of strategies labelled “coaching and supporting,” “ambivalence and uncertainty,” and “adjusting intentions.” According to the health care professionals in the study, meetings with individuals with diabetes and obesity present a professional challenge. The professionals aim to help each individual to lose weight and they are struggling to reach this goal. In their efforts, they are balancing coaching and caution. Combining those two approaches while simultaneously searching for strategies suited to each individual's unique situation, providing customised information, and motivating the individual to put knowledge into practice is a complex task. An additional challenge to health care professionals is their desire to help individuals to set realistic goals. The results also show that differing views between care providers and individuals concerning how the problem should be solved are not uncommon, which makes the situation even more complex. These findings are supported by results from a study by Zoffmann and Kirkevold (2005).

Our study revealed that the health care professionals have no predetermined plan for how to meet the special needs of individuals with diabetes and obesity in the care meeting and there is no solution that guarantees weight loss. The informants perceived that they were lacking sufficient strategies to help the individuals. Instead, they rely on their experience, their creativity, and their intuition of what seems to be appropriate for each individual. Not reaching their goal causes frustration, feelings of inadequacy, and a need to increase their knowledge of lifestyle counselling; this was also found in other studies (Huang et al., 2004; Jallinoja et al., 2007).

According to the health care professionals, the best indicator for success is the individuals’ internal motivation. The professionals are aware that they have an important task in increasing the individual's responsibility for his/her own situation, knowledge, and motivation. This is in-line with other studies that found that the individual's willingness to take responsibility for treatment and lifestyle changes was important to success (Elfhag & Rossner, 2005), and enhancing the individual's motivation was perceived as one of the health care professionals’ most important duties (Jallinoja et al., 2007). Despite all their knowledge of disease and what affects an individual's potential for weight loss, the informants still felt insecure about how to coach, counsel, and interact with the individual during the care meeting.

Health care professionals reported that it was almost impossible to predict which individuals will be successful or what strategies succeed in achieving weight loss. This produces feelings of insecurity as they apply different, tentative strategies in the attempt to help the individual achieve a better health situation. If the individual's health situation does not improve, the health care professionals feel responsible and their knowledge of the consequences becomes a burden. When the individual fails to achieve weight loss, their care providers feel frustrated and blame themselves for not having effective strategies. At the same time, they do not understand why the individual is not taking the problem seriously and making the necessary lifestyle changes. This is consistent with earlier studies that showed that when professionals do not succeed in motivating and guiding individuals to change their behaviour, they become frustrated (Jallinoja et al., 2007; Persson, Hornsten, Winkvist, & Mogren, 2010). When the professionals lack strategies to help the individual, they are at risk of blaming the individual and giving strict advice that has limited effects on the diabetes balance (Hornsten et al., 2008). Blaming the individual was not a prominent feature in our study; on the contrary, we found that when health care professionals failed in all their attempts to help the individual with obesity and diabetes, they resorted to the role of a cautious companion. In this role, professionals are wary of damaging their relationship with the individual. They do not discuss obesity much because they are afraid of increasing the individual's sense of guilt and shame. Satisfied with what the individual has achieved so far, they continue to search for new strategies to improve weight loss. This is in-line with an earlier study (Persson et al., 2010) that found that when the health care professionals were afraid to fail, they chose to act as a caring companion and felt it was preferable to have a good relationship in which they empowered the individual and respected his/her autonomy.

Some of the informants chose to abandon the obesity discussion and instead focused on mandatory issues and the medical situation. When the care providers focus on medical goals in the care meeting, they give priority to the biomedical paradigm and risk not meeting the individual's personal needs (Hornsten et al., 2008). Not discussing obesity openly increases the risk that the problem is not made explicit, neither the health care professional nor the individual will address it and weight loss will be difficult to achieve. As a result, the obesity will persist and the individual will not receive the necessary help and support. Huang et al. (2004) reported a relationship between whether the obesity problem is made clear in the care meeting and the actions that can be taken to address the weight problem.

The avoidance of discussing obesity was even more pronounced in meetings with obese women, as they were perceived by the study informants as more emotionally influenced than the obese men. When professionals do not discuss the disease as openly with women as they could do with the men, the risks associated with diabetes and obesity are not adequately addressed. The gender differences experienced by the professionals in our study were also reported in an earlier study, in which women were more emotionally influenced when they were reminded about their weight, whereas men did not express these emotional responses when discussing this issue (Svenningsson et al., 2011b). Women with obesity and diabetes talk about their obesity with strong feelings of guilt and shame (Svenningsson et al., 2011b); this study shows how such emotions influence how professionals perceive the different genders’ situation. The result of this study indicates that health care professionals might communicate with men and women differently because of their assumptions that women are more emotionally affected by their obesity than men. One explanation for this is the finding that men and women communicate differently in the care meeting (Street, 2002), which affects the way health care professionals interact with the different genders. It may be that they are more sensitive to women's needs than men's. When individuals provide details about their symptoms and express their feelings about the diagnosis, it affects the interaction between the individual and the care provider and allows a more exploratory approach (Cegala & Post, 2009).The present study is methodologically based on information from health care professionals interviewed either in groups or individually. The number of informants was quite small, which could be a possible weakness. However, data collection continued until there were no new features or information to add to the developed categories and saturation was reached. The interviewed groups were small because there were few professionals in the diabetes team at each health care centre. The study was conducted within the context of Swedish diabetes care and the findings should consider similar contexts. The interaction between the first author and the informants may have been influenced by the first author's previous knowledge. To avoid interpretations based on this previous knowledge, the first author continuously reflected on and discussed this with the co-authors, BG and LH. We believe that this study contributes to a deeper understanding by illuminating health care professionals’ main concern; their ambition to provide professional care and find the right strategy for each individual with diabetes and the strategies used to address it in care meetings with people with Type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Concluding remarks

The theory generated by this study can improve our understanding of how a lack of workable strategies influences caregivers’ abilities to reach their goal and can help identify the factors that contribute to the complexity of meetings between caregivers and individuals with diabetes and obesity.

Practice implications

This study addresses the main concern for health care professionals when consulting with individuals with obesity and diabetes at the health care centre. The professionals’ main concern was their ambition to provide professional care and find the right strategy for each individual with diabetes and obesity; that is, to offer individualised care. However, the most prominent element expressed was the lack of useful strategies. Obesity combined with diabetes is a major problem, and there is a need for individual strategies that take gender differences into account.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

References

- Cegala D. J., Post D. M. The impact of patients’ participation on physicians’ patient-centered communication. Patient Education and Counselling. 2009;77(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elfhag K., Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Review. 2005;6(1):67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funnell M. M. Overcoming obstacles: Collaboration for change. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;151(Suppl. 2):T19–T22. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151t019. discussion T29–T30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B., Strauss A. L. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg L. R.-M. The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Wellbeing. 2006;1(3):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam D. Obesity and diabetes: The links and common approaches. Primary Care Diabetes. 2010;4(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsten A., Lundman B., Almberg A., Sandström H. Nurses’ experiences of conflicting encounters in diabetes care. European Diabetes Nursing. 2008;5(2):64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Yu H., Marin E., Brock S., Carden D., Davis T. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Academic Medicine. 2004;79(2):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallinoja P., Absetz P., Kuronen R., Nissinen A., Talja M., Uutela A., et al. The dilemma of patient responsibility for lifestyle change: Perceptions among primary care physicians and nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2007;25(4):244–249. doi: 10.1080/02813430701691778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K., Kelly D. Practice development in community nursing: Opportunities and challenges. Nursing Standard. 2011;25(30):38–44. doi: 10.7748/ns2011.03.25.30.38.c8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M., Felton A. M. New global recommendations: A multidisciplinary approach to improving outcomes in diabetes. Primary Care Diabetes. 2007;1(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson M., Hornsten A., Winkvist A., Mogren I. “Mission Impossible”? Midwives’ experiences counseling pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter M. B., Vu J. D., Croughan-Minihane M. Weight management: What patients want from their primary care physicians. Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50(6):513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. L., Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Street R. L.,Jr. Gender differences in health care provider-patient communication: Are they due to style, stereotypes, or accommodation? Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;48(3):201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram M., Kavookjian J., Patrick J. H., Miller L. A., Madhavan S. S., Scott V. G. Quality of life, health status and clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(2):165–177. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson I., Attvall S., Marklund B., Gedda B. Type 2 diabetes: Perceptions of quality of life and attitudes towards diabetes from a gender perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2011a Mar 1; doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson I., Gedda B., Marklund B. Experiences of the encounter with the diabetes team—A comparison between obese and normal-weight type 2 diabetic patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011b;82(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai A. G., Wadden T. A. Treatment of obesity in primary care practice in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(9):1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoffmann V., Harder I., Kirkevold M. A person-centered communication and reflection model: Sharing decision-making in chronic care. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:670–685. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoffmann V., Kirkevold M. Life versus disease in difficult diabetes care: Conflicting perspectives disempower patients and professionals in problem solving. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(6):750–765. doi: 10.1177/1049732304273888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]