Abstract

Background:

Acne vulgaris is a chronic disease with several pathogenic factors. Multiple medications are typically used that can lead to nonadherence and treatment failure. Combination medications target multiple pathways of acne formation and may offer therapeutic benefit.

Purpose:

To explore the efficacy and tolerability of combination retinoid plus antimicrobial treatments in acne vulgaris.

Methods:

A PubMed and Google search was conducted for combination therapies of clindamycin and tretinoin, with secondary analysis of related citations and references. Similar searches were completed for the combination medications of benzoyl peroxide plus clindamycin or erythromycin, and for the combination therapy of adapalene and benzoyl peroxide.

Results:

Combination clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin gel was found to be more efficacious than monotherapy of either drug or its vehicle for acne, including inflammatory acne, and has a greater onset of action than either drug alone. Clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin gel was well-tolerated, and adherence to its use exceeded that of using both medications in separate formulations. Benzoyl peroxide-containing combination medications with clindamycin or erythromycin were both more effective in the treatment of acne than either drug alone. Both medications were well-tolerated, with dry skin being the most common adverse effect.

Conclusions:

Combination medications have superior efficacy and adherence, and have a similar tolerability profile compared with monotherapy of its components. Several studies have found antibiotic-containing combination products with a retinoid effective for acne. The use of antibiotic-containing combination medications for acne can lead to bacterial resistance. Due to this potential for bacterial resistance, benzoyl peroxide treatments are also recommended in combination with a retinoid.

Keywords: erythromycin, adherence, efficacy, safety, tolerability

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis that consists of open and closed comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules.1 It represents the most common skin disease in the population, affecting 40–50 million individuals of all races and ethnicities in the US.2–4 Acne can affect neonates, teenagers, and adults, with its prevalence peaking during the teenage years at 85% and remaining at 8% through adulthood.2 Furthermore, the patient age for visits to a physician for acne is decreasing with the decreasing age of puberty onset.5 Although a common disease, it can affect an individual emotionally and functionally in a manner comparable to someone with psoriasis, a condition known to cause significant morbidity.6,7 This significant psychosocial impact results in patients desiring treatment, and it has been shown that medical treatment has led to improvement of these factors.8,9

Pathogenesis of acne

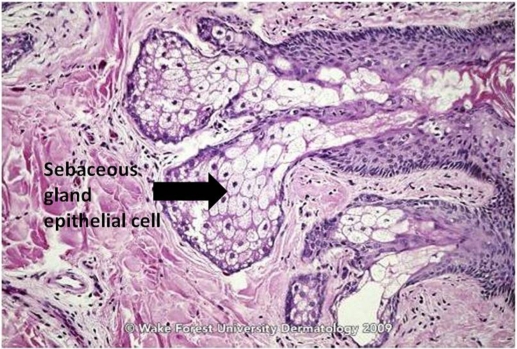

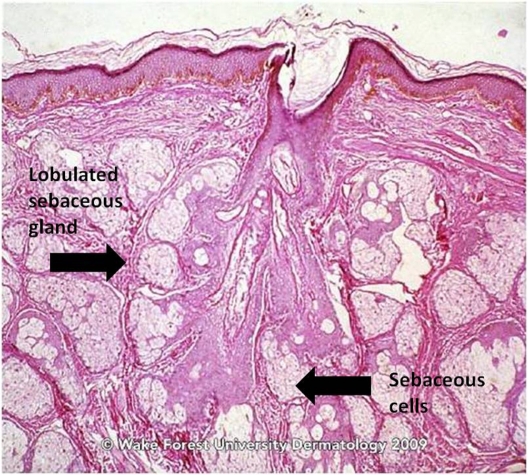

The classically described pathogenesis of acne is multi-factorial and originates at the pilosebaceous unit (PSU), which consists of large, multilobulated sebaceous glands, an epithelial-lined follicular canal, and a hair (Figures 1 and 2).3 In normal skin, sebum carries shed follicular epithelial cells to the skin’s surface unobstructed. However, in acne vulgaris, there is occlusion of the PSU by excess sebum production and/or increased cell turnover of the follicular canal. This results in bacterial overgrowth of, primarily, Propionibacterium acnes, an ensuing immune reaction, and inflammation.3 The combination of excess sebum production, dysfunctional epithelium development or desquamation, bacterial overgrowth, and immune reaction collectively lead to the development of acne vulgaris.

Figure 1.

Sebaceous gland of normal skin.

Source: Graham Library of Digital Images, Wake Forest University Department of Dermatology. © 2009 Wake Forest University Dermatology.

Figure 2.

Sebaceous gland of a young adult.

Source: Graham Library of Digital Images, Wake Forest University Department of Dermatology. © 2009 Wake Forest University Dermatology.

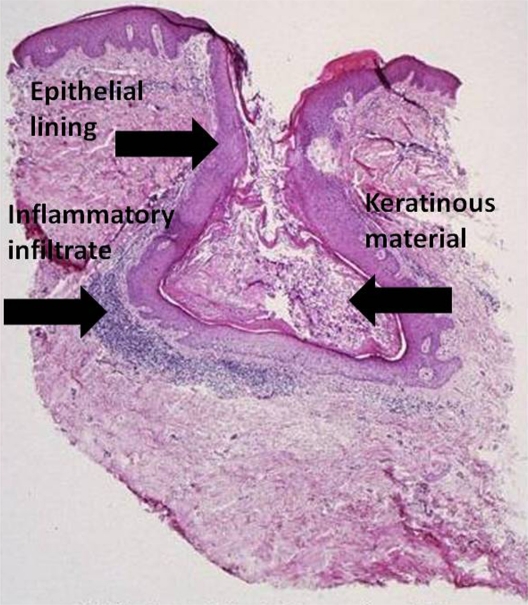

Microcomedones are the precursors to acne and are not visible on clinical examination. They can progress to noninflammatory lesions, or open and closed comedones, which both consist of sebum and shed keratinocytes (Figure 3).3 Both types of comedones can develop into inflammatory papules, nodules, or pseudocysts. Nodules and pseudocysts are present in severe forms of acne and may result in scarring if left untreated.

Figure 3.

Acne vulgaris, comedone. (Cx7).

Source: Graham Library of Digital Images, Wake Forest University Department of Dermatology. © 2009 Wake Forest University Dermatology.

New developments have expanded upon the classical pathogenesis of acne. In addition to the pathogenic factors from the classical model, altered sebum lipid quality, regulation of steroidogenesis in the skin, interaction with neuropeptidases, androgen activity, nutrition, and the presence of any pro- and anti-inflammatory agents have also been implicated in acne development.10

The sebaceous gland plays a more prominent role in acne development. Sebaceous glands express neuropeptide (NP) receptors such as corticotrophin-releasing hormone, B-endorphin, melanocortins, NP Y, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, and calcitonin gene-related peptide. These receptors regulate several processes in human sebaceous cells, including the regulation of inflammatory cytokine production, lipogenesis, and androgen metabolism.11,12 Further studies have shown that the keratinocytes and sebocytes of the PSU act as immune cells that recognize pathogens such as P. acnes via toll-like receptors, CD14, and CD1 molecules, and additionally identify abnormal lipids which result in inflammatory cytokine production.10,13 The follicles affected in acne have surrounding macrophages that express toll-like receptor 2 on their surface, which acts to trigger the production of cytokines and chemokines. The lipids produced by the sebaceous gland are increased in acne and play a role in signal transduction and biological pathways and also have pro- and anti-inflammatory characteristics.10,14 The fatty acids in the lipids act as ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, and when induced, cause lipogenic activity.15

Androgen activity plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of acne by influencing the proliferation and differentiation of sebocytes and infra-infundibular keratinocytes.10 Androgens may contribute to acne formation by initiating its development, by localized overproduction in the skin, or from the high expression or response of androgen receptors.10 The sebaceous gland expresses all of the enzymatic precursors necessary for testosterone synthesis, with the addition of 5α-reduced substances from dairy products or from circulating dehydroepiandrosterone.16,17

Investigation of the involvement of P. acnes in acne development remains controversial because of its presence as normal flora of human skin, and its pathogenic potential is not fully understood. Specific P. acnes strains can cause opportunistic infections that worsen acne.18 Antimicrobial peptides are present in noninflamed skin, which suggests that normal skin flora like P. acnes can facilitate the development of antimicrobial peptides without any inflammation.10 This can be beneficial in order to induce antibacterial effects; however, this also creates an environment that can promote increased resistance to other P. acnes strains.

Options for acne therapy

Approaching the management of acne is complex and requires consideration of the four main factors of its pathogenesis: disease duration and severity, past response to treatment, and skin color.4,19 No single topical or oral treatment can adequately address each component of therapy, and therefore several medications are usually required.3,19

Topical monotherapies can address three of the four causes of acne. However, no topical medicine can suppress excess sebum production.3,19 Topicals include retinoids, antibacterials, and benzoyl peroxide (BPO). Retinoids include tretinoin, isotretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. They act as keratolytics that have previously been reserved for noninflammatory lesions. There was concern of its association with skin irritation and an initial flare, both troublesome adverse effects (AEs).3,20 However, increasing evidence has led to the concept that retinoids can be used for inflammatory acne as a first-line treatment, with lesser skin irritation due to the development of newer generation retinoids, and retinoids can also aid in healing acne lesions.21,22 Also, clinical studies do not support the idea that topical retinoids worsen or flare acne during treatment.23 Antibacterials reduce the number of P. acnes, and can also work as weak comedolytics and anti-inflammatory agents.3 Long-term use of topical antibacterials cause resistant forms of P. acnes, and therefore is not recommended for chronic maintenance of acne. BPO is a mainstay of therapy for inflammatory acne and acts as an antibacterial and comedolytic agent.3,19,24 BPO can prevent bacterial resistance, thus contributing to safer, more eco-responsible acne management.25,26

Systemic medications for the treatment of acne are typically reserved for moderate and severe inflammatory acne, and include isotretinoin, antibacterials, and hormonal agents.3 Isotretinoin is a systemic retinoid that is highly effective for acne but carries a large systemic AE profile. Systemic antibiotics reduce the number of P. acnes, but have the risk of promoting bacterial resistance. They also carry AEs including gastrointestinal disturbances, photosensitivity, and vaginal yeast infections.3,27 Oral contraceptives can additionally be used, as the estrogen decreases the effect of androgens on the production of sebum.25

Adherence to acne therapy

With the greater risk of systemic AEs with oral therapies, several topical treatments may be prescribed. Topical application of medications is tedious, especially if multiple formulations have to be applied. This complicated treatment regimen for children to follow along with the chronic nature of the disease leads to poor medication adherence.28,29 Patients explain that failing to properly use their medications is in part due to forgetfulness and frustration.28,30,31 To improve adherence, simplifying treatment plans by way of decreasing dosing schedule and combining medicines into a single formulation are beneficial.

Use of combination formulations in the treatment of acne

Patients could theoretically be asked to combine multiple monotherapy medications and use them once per day to simplify their acne treatment regimen; however, it is unknown whether the active ingredients would remain stable and effective at lower concentration levels.28 This method may also add undue cost to the patient. Therefore, specially formulated combination therapies have been developed. The goal of combination therapy is to target multiple areas of acne pathogenesis that could not be accomplished with monotherapy of either active ingredient, thereby improving outcome.1 Various combination drugs have been studied, including tretinoin plus topical antibiotics, and BPO plus antibiotics. The purpose of this review is to explore the literature on the efficacy and tolerability of combination clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin and other combination medications in the treatments of acne vulgaris.

Methods

A PubMed search was performed to identify articles with the keywords “clindamycin” and “tretinoin”, and “combination”. Original articles on clinical trials were selected, and related citations were evaluated. Review articles and meta-analyses were selected for a comprehensive review. Similar searches for benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin or erythromycin were performed. A PubMed search was also performed to identify articles with the keywords “adapalene” and “benzoyl peroxide” and “combination”. This search resulted in 20 manuscripts, of which 17 were relevant for review and included original articles on clinical trials, meta-analyses, and review articles. A Google search was used to identify updates on new formulations for combination therapies. Reference lists from selected articles were used as a secondary method for obtaining articles and to evaluate the basis of the reviewed articles.

Results

Combination clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin

The combination product of clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin has been developed to target multiple areas of acne pathogenesis. Tretinoin acts as a comedolytic and anti-inflammatory, while clindamycin primarily acts as an antibacterial and decreases P. acnes counts.3 Together, the medications reduce comedogenesis and inflammation, and aid in the healing of acne lesions.21

There are currently two combination clindamycin and tretinoin products available. The first combination clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel (CTG) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 12 years and older in November 2006 (Ziana® Gel, Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation, Scottsdale, AZ). Another CTG formulation initially failed FDA approval in June 2005 because of concerns of dermal carcinogenicity in a single mouse model (Velac® Gel, Connetics Corporation, Palo Alto, CA). However, the CTG formulation was resubmitted and approved by the FDA in July 2010 (Veltin® Gel, Stiefel Laboratories Inc, NC).32

CTG vs use of clindamycin phosphate plus tretinoin

Several studies have been performed that investigated the use of CTG combination therapy vs using two separate medications each day (Table 1). In 1983, Rietschel and Duncan investigated the use of combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and tretinoin 0.025% gel vs monotherapy of clindamycin phosphate 1% plus tretinoin gel 0.025%.33 In this 8-week study, the combination regimen was not in a single formulation, but rather clindamycin phosphate applied in the morning and tretinoin at bedtime. All three programs resulted in lesion count reduction, but without significant differences between the study arms. Patient self evaluations found the most satisfactory improvement in 79% of the clindamycin monotherapy group, 68% in the tretinoin gel only group, and 65% in the combination therapy group. The combination therapy did not reduce patient tolerance of the medications, and the combination regimen had higher tolerability ratings than tretinoin gel. Also, clindamycin phosphate systemic absorption was undetectable at both 2 and 8 weeks. This suggests the combination therapy has similar efficacy to monotherapy and does not result in more patient intolerance.

Table 1.

Summary of investigations comparing CTG combination therapy to monotherapy of clindamycin, tretinoin, or vehicle

| Study | Drug | Study design | Study length | Study size (n) | Major results | Safety/AE | Other comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rietschel and Duncan33 | Clindamycin 1% plus tretinoin 0.025% vs monotherapy of clindamycin or tretinoin | Double-blind, randomized | 8 weeks | 64 | Similar efficacy amongst tretinoin plus clindamycin, tretinoin alone, and clindamycin alone; all arms of the study were well-tolerated | Dryness and peeling worse with tretinoin alone; burning and erythema not significantly different between combination of drugs and tretinoin; clindamycin alone had least AEs | Absorption of cindamycin phosphate was not detected at 2 and 8 weeks; combination therapy had fewer subjective complaints |

| Leyden et al34 | CTG vs monotherapy of clindamycin or tretinoin or vehicle | Two randomized, double-blind, multicenter, active drug- and vehicle-controlled | 12 weeks | 2219 | CTG group showed superior efficacy in treating inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions compared with monotherapy or vehicle alone | Well-tolerated overall; 87.6% of participants reporting no AEs | Study conclusions may not represent predominantly inflammatory or nodulocystic acne; most subjects had noninflammatory acne |

| Yentzer et al28 | CTG vs application of two separate generic subcomponents | Single-blind, prospective, single center, randomized, controlled trial | 12 weeks | 21 | CTG group had significant reduction in total lesions over length of study; both groups improved mild to moderate acne | Treatment was well-tolerated in both groups | Adherence of CTG product exceeded that of using two separate medications |

| Richter et al35 | CTG vs 0.025% tretinoin gel | Randomized, double-blind, multicenter | 12 weeks | 152 | CTG was superior to tretinoin in papular and inflammatory acne lesions and in overall acne severity | Less burning reported with CTG | CTG onset of action was faster than tretinoin |

| Zouboulis et al36 | CTG vs clindamycin lotion | Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, comparative | 12 weeks | 206 | CTG was more effective at reducing acne lesions than clindamycin monotherapy | More erythema and desquamation reported with CTG | CTG had faster onset of action than clindamycin monotherapy |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse effect; CTG, clinamycin 1.0%–1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel.

In 2010, Yentzer et al led a 12-week investigator-blinded, prospective, single-center, randomized, controlled trial that studied the efficacy and adherence of CTG vs dual use of separate clindamycin phosphate 1% gel and tretinoin 0.025% in the treatment of mild-to-moderate acne.28 CTG was applied once daily in one group, while clindamycin phosphate was applied once in the morning and tretinoin was applied once at night in the other. Study participants were evaluated at weeks 4, 8, and 12 via an investigator global assessment. Adherence was electronically monitored with Medication Event Monitoring System® (MEMS) caps to record information on when the medication was opened, and patients were unaware of the use of the MEMS caps. Only the CTG group had improvement at week 4 of the study when combining the results of noninflammatory and total lesion counts (P ≤ 0.05). Also, both groups improved in all areas of assessment by the end of the study, except for noninflammatory lesion reduction in the group using two separate medications (P < 0.05). Although not significant, the CTG group had a 51% mean reduction in total lesions vs 32% in the group using separate medications. A difference in adherence in the groups was found only at week 12 (P = 0.02). With compliance to treatment defined as 80% or more adherence, 67% of the CTG group and 8% of the group taking the separate medications were compliant. The CTG patients had no detected change in adherence over time (P = 0.24), while there was a significant drop in the separate agent group (P = 0.003). Although CTG use resulted in greater lesion reduction and better adherence, the correlation between the two was not statistically significant, which may have been due to the small study size. This investigation found that the use of a once-daily combination medication can encourage better adherence and clinical efficacy.

CTG vs tretinoin monotherapy

In 2006, Leyden et al compared CTG to monotherapy of its components and vs vehicle alone in two 12-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, active drug- and vehicle-controlled studies.34 A total of 634 patients were in the CTG arm of the study, with 635 in the tretinoin arm. There was a significantly greater reduction in inflammatory lesions in patients using CTG therapy (53.4%) vs the tretinoin only group (43.3%). The combination therapy group also reduced noninflammatory lesion counts (45.2%) vs tretinoin monotherapy (37.9%). The CTG group showed a significantly greater reduction in total lesion counts (48.7%) than tretinoin monotherapy (40.3%). At the end of the study, 37% of CTG subjects compared with 25% of tretinoin gel monotherapy subjects were clear or almost clear on Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA). Regarding tolerability, CTG and tretinoin monotherapy subjects had similar rates of AEs (19% vs 17%, respectively). This supported the efficacy of CTG over monotherapy in reducing inflammatory and noninflammatory acne lesions.

In 1998, Richter et al conducted a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, multicenter study of 161 patients to compare the efficacy and safety of CTG in moderate to severe acne vs monotherapy of tretinoin, with some similar results.35 The efficacy of each treatment regimen was evaluated at 4, 8, and 12 weeks by calculating an overall acne severity grade and assessing its improvement over time. AEs were graded and recorded by investigator assessments at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. There was no difference in the reduction of open comedones in the CTG group vs the tretinoin group at the end of the study, at 58% and 53%, respectively (P = 0.3), or the reduction of closed comedones, at 65% and 52%, respectively (P = 0.06). The reduction of total lesions with CTG treatment vs tretinoin treatment was 61% and 55%, respectively (P = 0.15). CTG was more effective than tretinoin at reducing papules at each of the 3 weeks of assessment (P = 0.04, 0.01, and 0.0004 at weeks 4, 8, and 12, respectively), but there was no difference in pustule or nodule reduction. CTG was more effective in reducing the quantity of inflammatory acne lesions during treatment with a 73% reduction vs 54% with tretinoin (P = 0.006 at 12 weeks). This decrease occurred about 60% faster as well. Overall acne severity grade improved 64% over the length of the study for CTG and 54% for tretinoin (P = 0.01). Authors concluded that CTG efficacy was superior to tretinoin monotherapy in papular and inflammatory lesions, as well as in overall acne severity. CTG also reported less burning, but this may have been due to an emollient added in the CTG vehicle formulation.

CTG vs clindamycin monotherapy

Zouboulis et al performed a 12-week, Phase III, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, comparative study on 206 subjects to investigate the efficacy and safety of CTG vs clindamycin 1% lotion for moderate-to-severe acne.36 CTG was applied once daily, and the clindamycin lotion was applied twice daily. Efficacy, AEs, medications, the overall acne severity grade, and compliance were all assessed at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 of the study. Compliance was evaluated by recording missed applications at each follow-up visit.

The absolute lesion reduction was 69.2% for the CTG group vs 60.9% for the clindamycin group (P = 0.05). Reduction of noninflammatory lesions at the end of the study was 66.8% for CTG vs 59.9% for the clindamycin group. The absolute reduction of inflamed lesions at week 12 was greater for CTG than clindamycin (P = 0.018), and was true for all inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, and nodules). In the per protocol group, the reduction of pustules over the length of the study was significant in the CTG group compared with clindamycin monotherapy (P = 0.031), and the reduction in nodules neared significance (P = 0.062). Absolute reduction of acne severity score was observed at week 12 for both the overall score (P = 0.03) and mean percentage (P < 0.01). Subjective assessment of overall acne severity using the Cook scale found a greater reduction in the CTG group over the 12-week study (P = 0.007). Regarding rapidity of effects, the CTG group had more individuals with a 50% reduction in total lesions by day 60 (77%) than the clindamycin lotion group (56%) (P = 0.003). Open comedone reduction contributed largely to the more rapid effect of onset of CTG (P = 0.0006). Both groups showed moderate or good improvement in the overall analysis and were generally well-tolerated. This demonstrates that once daily use of CTG is at least as effective as clindamycin 1% lotion applied twice daily, while also having a quicker onset of action.

Leyden et al in 2006 also compared CTG with clindamycin, including 634 participants in the CTG group vs 635 in the clindamycin monotherapy group.34 There was a 53.4% reduction of inflammatory lesions using CTG vs 47.5% of clindamycin only subjects, as well as a 45.2% vs 31.6% mean reduction of noninflammatory lesions in the CTG and clindamycin groups, respectively. Total lesion count reductions were 48.7% in the CTG group vs 38.3% in the clindamycin group. ISGA showed 37% of CTG participants were clear or almost clear after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 27% of clindamycin gel only subjects. Each of these parameters demonstrated greater efficacy of CTG therapy vs clindamycin monotherapy. However, fewer subjects in the clindamycin arm reported AEs (5%) compared with the CTG group (19%).

Associations with acne flares

The original formulations of tretinoin had a 0.05% concentration in a hydroalcohol vehicle, and nearly 20% of patients reported AEs, including acne flares, within a few weeks of initiating treatment.37 Thus, the use of tretinoin was hesitatingly used for acne, particularly with the inflammatory type. Schlessinger et al investigated an evaluation of flaring of inflammatory lesions after 2 weeks of therapy with either CTG, clindamycin phosphate 1.2%, tretinoin 0.025% gel, or vehicle monotherapy.38 Flaring was defined as a 20% or more increase in inflammatory lesion count. In patients with moderate-to-severe acne, the subjects using only vehicle experienced the greatest acne flare (12.1% in moderate cases, 12.7% in severe). In mild acne, tretinoin monotherapy resulted in the greatest percentage of flares (9.9%) followed by clindamycin (7.7%). For mild and moderate acne, CTG showed the lowest percentage of acne flares (4.2%, 5.6%, and 7.5% for mild, moderate, and severe, respectively). The authors concluded that except for subjects with mild inflammatory acne, there was no evidence of acne flaring caused by tretinoin use. This conclusion is consistent with the known anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin, and that new vehicle formulations are utilized with tretinoin gel and CTG.37,38

AEs

AEs reported from Phase III studies by the manufacturers of CTGs are shown in Table 2. At 12 weeks, at least one AE was reported in 27% of CTG patients, 24% for clindamycin, 27% for tretinoin gel, and 22% for vehicle gel.39,40 Nasopharyngitis ranged among all groups from 1% to 5%, followed by pharyngolaryngeal pain (1%–2%), dry skin (0%–1%), cough (1%–2%), and sinusitis (1%–2%). These AEs occurred in about equal percentages amongst all groups, were most likely due to general medical conditions or local application site reactions, and occurred as expected.38,41

Table 2.

|

CTG N = 1853 N (%) |

Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% N = 1428 N (%) |

Tretinoin 0.025% gel N = 846 N (%) |

Vehicle gel N = 423 N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least 1 AE | 497 (27) | 342 (24) | 225 (27) | 91 (22) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 65 (4) | 64 (5) | 16 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Pharyngolaryngeal pain | 29 (2) | 18 (1) | 5 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Dry skin | 23 (1) | 7 (1) | 3 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Cough | 19 (1) | 21 (2) | 9 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Sinusitis | 19 (1) | 19 (1) | 15 (2) | 4 (1) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse effect; CTG, clinamycin 1.0%–1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel.

Local skin reactions were also summarized for all Phase III studies on CTG therapy (Table 3).39,40 Erythema, scaling, itching, burning, and stinging were all reported. Erythema was the most common local skin reaction overall, and decreased slightly in frequency from baseline to the end of treatment (35% and 26%, respectively). Scaling was reported in 13% at baseline and 17% at the end of treatment. Itching was found in 10% of subjects at baseline and decreased to 4% by the end of treatment. Burning and stinging were both reported to be less than 5% at both baseline and at the end of treatment. The incidence of local skin reactions was either minimally increased or decreased by the end of treatment.38

Table 3.

| Local reaction |

Baseline N = 1835 N (%) |

End of treatment N = 1614 N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Erythema | 636 (35) | 416 (26) |

| Scaling | 237 (13) | 280 (17) |

| Itching | 189 (10) | 70 (4) |

| Burning | 38 (2) | 56 (4) |

| Stinging | 33 (2) | 27 (2) |

Abbreviation: CTG, clinamycin 1.0%–1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel.

The trial by Zouboulis et al reported erythema and skin desquamation occur more often in subjects using CTG than clindamycin monotherapy.36 When AEs occurred with CTG use, application site dryness, desquamation, burning, erythema, and pruritus were more common in subjects using CTG than in clindamycin, tretinoin, or vehicle monotherapy.34 The AE incidence using CTG paralleled that in tretinoin for dryness (9% vs 8%), desquamation (8% vs 7%), burning (6% vs 5%), and pruritus (4% vs 3%), and were more common than in the clindamycin or vehicle monotherapy groups. Although AEs occurred, they were expected, and notably AEs are more commonly not reported. In one report of 2219 subjects, 87.6% reported no AEs over the course of the 12-week study.34 Kircik et al investigated AEs and safety for CTG with a 6- or 12-month duration, multicenter, open-label study. In long-term treatment, 92%, 91%, and 94% of all participants (N = 655) reported no itching, burning, or stinging, respectively.42 Most studies conclude CTG combination therapy as being well-tolerated overall.28,33,34,36,41–43

Safety considerations

There are two major safety issues to consider with CTGs. Topical clindamycin has been associated with pseudomembranous colitis due to overgrowth of Clostridium difficile, and systemic circulation of retinoids is known for being a teratogenic. With the suspicion of increased permeability of the skin with a combination formulation such as CTG due to the enhancing effects of tretinoin, van Hoogdalem et al investigated the transdermal uptake of both tretinoin and clindamycin from CTG.43 After 5 days of daily application to the face, percutaneous absorption of clindamycin phosphate in plasma samples were immeasurable (<5 ng/mL), while plasma levels of clindamycin HCl topical were as high as 13 ng/mL (n = 12). Urinary excretion of clindamycin from both the combination medicine and reference clindamycin lotion was comparable in all but one subject. This subject had increased excretion, but the patient had irritated, peeling skin contributing to the increased uptake of drug. In a separate study of acne patients in the same manuscript, CTG use did not cause a measurable transdermal uptake of tretinoin after 12 weeks, clindamycin levels were not quantifiable in 87% of patients, and the highest clindamycin level was 11 mL–1 (n = 40). These studies support the notion that clindamycin uptake in the presence of tretinoin in combination therapy is not increased, and the risk of pseudomembranous colitis with combination clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin is low. However, combination therapy should be discontinued if significant diarrhea occurs.39,40

The safety of CTG use during pregnancy is still unknown and is classified as a category C drug.39,40 All studies have excluded both pregnant and lactating females. It is recommended to avoid use of CTG in this patient subpopulation unless its benefit of use is determined to outweigh the potential risks.

Other combination acne combination therapies

Various other combination products on the marketplace also incorporate a topical antibiotic, such as topical clindamycin or erythromycin. Some utilize BPO, which acts via a different mechanism as an antibacterial agent and comedolytic agent, as a replacement for the tretinoin used in CTG.

Combination BPO and clindamycin (BPO/clin)

Several studies investigated the benefit of a combined formulation of BPO/clin vs monotherapy of either drug (Table 4). Lookingbill et al performed an 11-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel, controlled study of 334 subjects comparing BPO/clin (5%/1%) to monotherapy of either drug of similar concentrations or vehicle.44 The BPO/clin combination had greater efficacy than monotherapy of either drug or vehicle, and the combination drug was well-tolerated.

Table 4.

Summary of comparative investigations of BPO/clin or BPO/erythro combination therapies vs monotherapy of either drug’s constituents and vehicle

| Study | Drug | Study design | Study length | Study size (n) | Major results | Safety/AE | Other comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lookingbill et al44 | BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs monotherapy of BPO (5%) or clin (1%) or vehicle | Two double-blind, randomized, parallel, controlled | 11 weeks | 334 | BPO/clin showed greater efficacy than monotherapy of BPO, clin, or vehicle | Excellent overall tolerance reported in 95% of patients; no difference in AEs in active drug arms | Concluded that combination BPO/clin is superior to either drug alone |

| Leyden et al45 | BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs monotherapy of BPO (5%) or clin (1%) or vehicle | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind | 10 weeks | 480 | BPO/clin more effective than monotherapy of BPO, clin, or vehicle | Similar AEs in all arms of study; most common AE was skin dryness | Concluded combination BPO/clin as an alternative treatment for moderate to moderately severe acne |

| Leyden et al46 | BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs BPO (5%) or BPO/erythro (5%/3%) | Randomized, multicenter, single-blind | 10 weeks | 492 | BPO/clin showed greater reduction than BPO in inflammatory lesions and was not more efficacious than BPO/erythro | AEs similar in all arms; dry skin most frequently reported in all arms | Concluded BPO/clin combination more effective than BPO alone and at least as effective as BPO/erythro |

| Tschen et al47 | BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs BPO (5%) vs clin (1%) vs vehicle | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group | 10 weeks | 278 | BPO/clin reduced inflammatory lesions more than either drug alone; BPO/clin reduced comedones more than clin or vehicle | Dry skin most frequent AE overall and more common in BPO/clin and BPO | Concluded BPO/clin more effective than monotherapy of either drug, especially for inflammatory acne |

| Thiboutot et al48 | BPO/clin (2.5%/1.2%) vs BPO (2.5%) vs clin (1.2%) vs vehicle | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active- and vehicle-controlled, parallel-group, comparative | 12 weeks | 2813 | BPO/clin was more effective at treating both noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions than either drug alone or vehicle | BPO/clin preparation was well-tolerated, and the AEs reported were reported as mild to moderate | BPO/clin is a safe, effective, and well-tolerated agent for the treatment of moderate to severe acne |

| Cunliffe et al49 | BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs clin 1% gel | Double-blind, randomized, parallel-group | 16 weeks | 70 | BPO/clin reduced number of Propionibacterium acnes and clin-resistant P. acnes; clin monotherapy increased bacteria count; BPO/clin showed better efficacy than clin | Both preparations were well-tolerated | Decreasing P. acnes and clin-resistant P. acnes counts correlated with the reduction in total acne lesions |

| Chalker et al51 | BPO/erythro (5%/3%) vs BPO (5%) vs erythro (3%) vs vehicle | Double-blind, controlled | 10 weeks | 165 | BPO-containing products reduced comedones more effectively than erythro alone; reduced pustules, papules, and inflammatory lesions | No AEs reported | BPO/erythro more effective than either drug alone, especially for inflammatory lesions |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse effect; BPO, benzoyl peroxide; BPO/clin, benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin phosphate combination medication; BPO/erythro, benzoyl peroxide/erythromycin combination medication; clin, clindamycin phosphate; erythro, erythromycin.

Leyden et al also studied the efficacy of BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs monotherapy of either BPO (5%), clindamycin (1%), or vehicle.45 Again, BPO/clin was more effective than either of its active drugs alone as an alternative treatment of moderate or moderately severe acne. The combination formulation was well-tolerated, with dry skin the most frequently reported AE in all groups, and its AE profile was similar to that of BPO monotherapy.

In a separate investigation, Leyden et al compared combination BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs BPO (5%) alone and BPO/erythromycin (5%/3%) in 492 subjects.46 BPO/clin was more efficacious than BPO monotherapy for reducing inflammatory lesions, and there was no difference in efficacy between the two combination therapies. AEs were similar amongst all three groups, with skin dryness most commonly reported, but overall the medications in all groups were well-tolerated. Thus, BPO/clin combination therapy is an efficacious, tolerable, and safe alternative therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-moderately severe acne vulgaris.

A total of 287 patients with moderate to moderately severe acne was performed by Tschen et al, which also compared BPO/clin to monotherapy of BPO, topical clindamycin, or vehicle.47 BPO/clin reduced inflammatory lesions more than either drug alone. Also, the combination medication reduced comedones more than clindamycin or vehicle, but not compared with BPO monotherapy. Tolerability was good for all medicines used. Dry skin was the most frequent AE and more common in the BPO/clin and BPO groups. This investigation concluded that BPO/clin was more effective than monotherapy of either drug, especially for inflammatory acne.

Thiboutot et al compared BPO/clin (2.5%/1.2%) to monotherapy of BPO, clindamycin phosphate, or vehicle in the largest subject study for acne vulgaris (n = 2813).48 The 12-week multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active- and parallel-group, comparative study evaluated BPO/clin for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. BPO/clin was more effective for treating both noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions than monotherapy of either active drug or vehicle. The combination drug was well-tolerated, and any reported AEs were mild-to-moderate in nature. Thus, a larger study shows BPO/clin as safe, effective, and well-tolerated for the treatment of acne vulgaris.

Cunliffe et al compared BPO/clin (5%/1%) to clindamycin 1% gel for clinical efficacy and reductions in P. acnes and clindamycin-resistant P. acnes counts.49 After 16 weeks of treatment in 70 subjects, BPO/clin therapy reduced the number of P. acnes and clindamycin-resistant P. acnes counts significantly more than topical clindamycin monotherapy. Use of clindamycin alone actually increased bacteria counts > 1600% after 16 weeks of treatment. Both preparations were well-tolerated by the study participants. This demonstrated a correlation exists between acne lesion counts and the number of P. acnes and clindamycin-resistant P. acnes.

All studies reviewed demonstrated that combination therapy was more effective than monotherapy of either BPO or clindamycin in the treatment of acne vulgaris, particularly for the treatment of inflammatory lesions. Although the superiority in efficacy of BPO/clin combination therapy over monotherapy of either drug alone has been demonstrated, the value of this in clinical practice needs to be considered by the practitioner as to whether this data in combination with other factors like cost, risks including bacterial resistance, and availability.50

Combination BPO and erythromycin (BPO/erythro)

Chalker et al completed a 10-week study on 165 participants that compared the efficacy of BPO/erythro (5%/3%) combination therapy to monotherapy of each drug and vehicle (Table 4).51 The BPO-containing products, BPO/erythro and BPO monotherapy, reduced comedones more than erythromycin alone, but not significantly. Also, combination therapy reduced pustules and papules, but no more than either drug alone. BPO/erythro significantly reduced the number of inflammatory lesions better than either drug alone or the vehicle. There were no reported AEs. Thus, particularly for inflammatory lesions, BPO/erythro was more effective than either drug alone.

As previously discussed, Leyden et al compared BPO/clin (5%/1%) vs BPO (5%) or BPO/erythro (5%/3%) in a 10-week study of 492 patients, showing no differences between the two combination therapies, however BPO/erythro was more efficacious than BPO alone.46

Combination adapalene and BPO (adapalene-BPO)

A new, potent combination regimen incorporates adapalene, a retinoid, plus BPO, where BPO acts as a bactericidal agent and decreases inflammation, and a retinoid acts on both comedonal and inflammatory lesions without the need for an antibiotic.19,21,22 Several trials have assessed the efficacy and tolerability of the combination adapalene-BPO gel vs monotherapies of either drug and its vehicle (Table 5). All of the studies reported superior efficacy of the combination product vs monotherapies of either drug.52–55 Few clinical trials only investigated the tolerability of the combination product vs monotherapies and found good tolerability overall when compared with monotherapy of either drug and a similar AE profile to adapalene monotherapy.56–58 Troielli et al investigated the use of adapalene-BPO in the community setting and found the combination therapy demonstrates good efficacy and tolerability in general practice.56

Table 5.

Summary of comparative investigations of adapalene-BPO combination therapies vs monotherapy of each and vehicle

| Author | Drug | Study design | Study length | Study size (n) | Major results | Safety/AE | Other comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poulin et al52 | Adapalene-BPO vs vehicle | Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled | 12 weeks | 243 | Significantly higher lesion maintenance success rate for inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions with adapalene-BPO vs vehicle | Adapalene-BPO was safe and well-tolerated | Adapalene-BPO prevents the relapse in severe acne and continues to reduce lesion counts over 6 months |

| Troielli et al56 | Adapalene-BPO | Open-label, community-based, multicenter, interventional | 12 weeks | 105 | Adapalene-BPO use significantly decreased inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions | Good local tolerability | Adapalene-BPO has good efficacy and tolerability in routine practice |

| Gold et al53 | Adapalene-BPO vs monotherapy of either drug alone and gel vehicle | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, active- and vehicle-controlled | 12 weeks | 1429 | Adapalene-BPO showed higher success rate and reduction of acne lesions than other groups | comparable safety of adapalene-BPO to monotherapies and gel vehicle | Large clinical trial demonstrates fixed-dose combination therapy to be superior in efficacy with an early onset of efficacy |

| Gollnick et al54 | Adapalene-BPO vs monotherapy of either drug alone and gel vehicle | Randomized, double-blind, controlled | 12 weeks | 1670 | Adapalene-BPO showed significantly greater efficacy than monotherapies | Well-tolerated, with comparable tolerability to a dapalene monotherapy | Adapalene-BPO use results in significantly greater and synergistic results in the treatment of acne vulgaris compared with monotherapies |

| Loesche et al58 | Adapalene-BPO vs monotherapy of either drug alone and gel vehicle | Single center, controlled, randomized, investigator-blinded intra-individual | 3 weeks | 24 | Study analyzed tolerability only; no significant difference in irritation indices for adapalene-BPO vs monotherapies | Adapalene-BPO is as well-tolerated as either monotherapy in relation to irritancy | |

| Andres et al57 | Adapalene-BPO vs BPO 2.5%; adapalene-BPO vs BPO 5%; adapalene 0.1%-BPO 5% combination vs BPO 5%; and adapalene 0.1%-BPO 5% combination vs BPO 10% | Randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded, single-center, bilateral (split-face), dose-assessment | 3 weeks | 60 | Study analyzed tolerability only; better tolerability profile of adapalene 0.1%-BPO 2.5% than adapalene 0.1%-BPO 5%; similar to either BPO 2.5% or 5% monotherapy; adapalene 0.1%-BPO 5% caused more irritation than BPO 5% or 10% monotherapy | Adapalene 0.1%-BPO 2.5% combination product had best tolerability profile compared with BPO monotherapy | |

| Thiboutot et al55 | Adapalene-BPO vs monotherapy of either drug alone and gel vehicle | Randomized, double-blind, controlled | 12 weeks | 517 | Adapalene-BPO significantly more effective than monotherapies with significant reduction in lesion counts at 1 week | Similar adverse event frequency and tolerability profile for combination gel vs adapalene monotherapy | Adapalene-BPO use results in significantly greater efficacy for treatment of acne vulgaris compared to monotherapies and a similar tolerability profile to adapalene monotherapy |

Abbreviations: adapalene-BPO, adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% combination gel; BPO, benzoyl peroxide.

Zouboulis et al directly compared the combination therapies adapalene-BPO and BPO/clin.59 They found that the two combination therapies have a similar efficacy profile in reducing both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions; however, they concluded that the BPO/clin product results in better treatment success with a better tolerability profile and safety profile than adapalene-BPO.

A subgroup analysis by Eichenfield et al investigated the efficacy and safety of an adapalene/BPO (0.1%/2.5%) combination gel in acne, showing the combination therapy was more effective than monotherapies or vehicle alone and had an onset of action of 1 week.60 The early onset of action and combination dosing can aid in increased adherence and therapeutic outcome because of its ease of use in a single formulation and its high treatment efficacy. This medication also avoids the potential for bacterial resistance and includes two mainstays in the treatment of acne vulgaris.

Discussion

The use of combination therapy is established as a superior treatment plan to monotherapy in acne vulgaris because it targets multiple factors of its pathogenesis.3 Combining medications also results in increased adherence and better therapeutic outcomes by reducing the complexity of acne management.28 The combination of clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin treatment works to decrease inflammation, reduces P. acnes counts, acts as a comedolytic, and reduces comedogenesis. CTG is indicated for mild-to-moderate acne; however, studies have investigated the use of CTG for moderate-to-severe acne either alone or in conjunction with other therapies.35,36 The ability for CTG to decrease inflammatory lesions can aid in more severe forms of acne and can be considered as an alternative agent in treatment.

Other antibiotic-containing combination therapies include BPO and either clindamycin or erythromycin. These combination therapies were also more efficacious in treating mild-to-moderate acne and are well-tolerated. When combination BPO and either clindamycin or erythromycin are compared with one another for efficacy, there is no significant difference in outcome.46

One limitation of the use of combination medications that include antibiotics is the potential for bacterial resistance while using topical antibiotics, and more eco-responsible alternatives should be considered when appropriate.25 BPO is a mainstay of mild-to-moderate acne therapy and an alternative to antibiotic use for management. Incorporating BPO into one’s treatment regimen can reduce antibiotic resistance when used with a topical antibiotic and can be used long-term.25,26 Combination products that combine BPO are thus a reasonable alternative. Eady et al investigated the use of combination BPO and erythromycin treatment and its effects on P. acnes and erythromycin-resistant P. acnes and found combining medications results in greater reductions of bacterial counts and also better clinical outcomes in patients already colonized with resistant strains of P. acnes.61 Although combining BPO with an antibiotic can reduce bacterial counts with good clinical outcomes, taking measures to reduce the initial problem of drug-resistant bacteria by the physician is prudent.

The combination product of a retinoid plus BPO, such as adapalene-BPO, should be strongly considered for acne vulgaris. Feldman et al analyzed several clinical trials on adapalene-BPO and found that its benefit increases with higher lesion counts at the beginning of the study.62 This data suggests that adapalene-BPO therapy may be suitable for more severe forms of acne; however, the combination product was studied on inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions and is also found to be efficacious in milder forms of acne. The versatility of its efficacy suggests that its use should be considered in the spectrum of mild-to-severe acne. It also has the added benefit of a BPO, which is not associated with antibiotic resistance.

A combination retinoid with antimicrobial medication is effective for both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne. It has a faster onset of action than either drug alone and is considered to be well-tolerated and safe for most patients. A combination product leads to increased adherence and greater clinical outcome. BPO and antibiotic combination formulations are also more efficacious than either treatment alone with a good tolerability profile. The concern for bacterial resistance arises when using topical antibiotics, thus a combination product containing other active medications like a retinoid plus BPO should be considered for therapy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The Center for Dermatology Research is supported by an educational grant from Galderma Laboratories, LP. Dr Feldman has received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Galderma, Abbott Labs, Warner Chilcott, Leo, Amgen, Astellas, Centocor, National Biological Corporation, and Stiefel/GSK. Dr Dabade, Ms Feneran, and Mr Kaufman have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Katsambas A, Dessinioti C. New and emerging treatments in dermatology: acne. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gollnick H. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of acne: implications for drug treatment. Drugs. 2003;63:1579–1596. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins A, Cheng C, Hillebrand G, Miyamoto K, Kimball A. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010 Nov 25; doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03919.x. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg JL, Dabade TS, Davis SA, Fleischer AB, Jr, Krowchuk DP, Feldman SR. Changing Age of Acne Vulgaris Visits: another sign of earlier puberty? Accepted for publication March 19, 2011 by Pediatric Dermatology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:846–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasek RJ, Chren MM. Acne vulgaris and the quality of life of adult dermatology patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:454–458. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo J. The psychosocial impact of acne: patients’ perceptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:S26–S30. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krowchuk DP, Stancin T, Keskinen R, Walker R, Bass J, Anglin TM. The psychosocial effects of acne on adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:332–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:821–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zouboulis CC. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DY, Yamasaki K, Rudsil J, et al. Sebocytes express functional cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides and can act to kill propionibacterium acnes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1863–1866. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koreck A, Pivarcsi A, Dobozy A, Kemeny L. The role of innate immunity in the pathogenesis of acne. Dermatology. 2003;206:96–105. doi: 10.1159/000068476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alestas T, Ganceviciene R, Fimmel S, Muller-Decker K, Zouboulis CC. Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of leukotriene B4 and prostaglandin E2 are active in sebaceous glands. J Mol Med. 2006;84:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Testosterone metabolism to 5alpha-dihydrotestosterone and synthesis of sebaceous lipids is regulated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligand linoleic acid in human sebocytes. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:428–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darling JA, Laing AH, Harkness RA. A survey of the steroids in cows’ milk. J Endocrinol. 1974;62:291–297. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0620291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, Tsai SJ, Liao CY, et al. Higher levels of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and type I 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the scalp of men with androgenetic alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2332–2335. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell A, Valanne S, Ramage G, et al. Propionibacterium acnes types I and II represent phylogenetically distinct groups. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:326–334. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.326-334.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leyden JJ. A review of the use of combination therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S200–S210. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf JE, Jr, Kaplan D, Kraus SJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of combined topical treatment of acne vulgaris with adapalene and clindamycin: a multicenter, randomized, investigator-blinded study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S211–S217. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Naser MB, Zouboulis CC. Clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin gel formulation in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2931–2937. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.16.2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf JE., Jr Potential anti-inflammatory effects of topical retinoids and retinoid analogues. Adv Ther. 2002;19:109–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02850266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yentzer BA, McClain RW, Feldman SR. Do topical retinoids cause acne to “flare”? J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:799–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanghetti E. The evolution of benzoyl peroxide therapy. Cutis. 2008;82:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinney MA, Yentzer BA, Fleischer AB, Jr, Feldman SR. Trends in the treatment of acne vulgaris: are measures being taken to avoid antimicrobial resistance? J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:519–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sagransky M, Yentzer BA, Feldman SR. Benzoyl peroxide: a review of its current use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:2555–2562. doi: 10.1517/14656560903277228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiboutot D. New treatments and therapeutic strategies for acne. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:179–187. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koo J. How do you foster medication adherence for better acne vulgaris management? Skinmed. 2003;2:229–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2003.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Manuel JC, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yentzer BA, Baldwin H, Shalita A, Webster G, Feldman SR. Optimizing patient adherence: update on combination acne therapy – teens and beyond. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:s92–s95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding S. Veltin™ (Clindamycin Phosphate and Tretinoin) Gel 1.2%/0.025% 2011. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/050803Orig1s000ChemR.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2011.

- 33.Rietschel RL, Duncan SH. Clindamycin phosphate used in combination with tretinoin in the treatment of acne. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:41–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1983.tb02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leyden JJ, Krochmal L, Yaroshinsky A. Two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of 2219 subjects to compare the combination clindamycin/tretinoin hydrogel with each agent alone and vehicle for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter JR, Forstrom LR, Kiistala UO, Jung EG. Efficacy of the fixed 1.2% clindamycin phosphate, 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) and a proprietary 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Aberela) in the topical control of facial acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zouboulis CC, Derumeaux L, Decroix J, Maciejewska-Udziela B, Cambazard F, Stuhlert A. A multicentre, single-blind, randomized comparison of a fixed clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) applied once daily and a clindamycin lotion formulation (Dalacin T) applied twice daily in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:498–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2000.03701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leyden JJ, Wortzman M. A novel gel formulation of clindamycin phosphate-tretinoin is not associated with acne flaring. Cutis. 2008;82:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining 1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medicus Ziana® prescribing information. http://pi.medicis.us/ziana.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2011.

- 40.Stiefel Veltin® prescribing information. http://www.stiefel.com/US/us_veltin.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2011.

- 41.Eichenfield LF, Wortzman M. A novel gel formulation of 0.25% tretinoin and 1.2% clindamycin phosphate: efficacy in acne vulgaris patients aged 12 to 18 years. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:257–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kircik LH, Peredo MI, Bucko AD, et al. Safety of a novel gel formulation of clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025%: results from a 52-week open-label study. Cutis. 2008;82:358–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Hoogdalem EJ, Baven TL, Spiegel-Melsen I, Terpstra IJ. Transdermal absorption of clindamycin and tretinoin from topically applied anti-acne formulations in man. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1998;19:563–569. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199812)19:9<563::aid-bdd134>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590–595. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leyden JJ, Berger RS, Dunlap FE, Ellis CN, Connolly MA, Levy SF. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of a combination topical gel formulation of benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin with benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin and vehicle gel in the treatments of acne vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:33–39. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leyden JJ, Hickman JG, Jarratt MT, Stewart DM, Levy SF. The efficacy and safety of a combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel compared with benzoyl peroxide alone and a benzoyl peroxide/erythromycin combination product. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:37–42. doi: 10.1177/120347540100500109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tschen EH, Katz HI, Jones TM, et al. A combination benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin topical gel compared with benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin phosphate, and vehicle in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2001;67:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, Webster G, Calvarese B, Chen D. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, Levy SF. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1117–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seidler EM, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide with salicylic acid, and combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chalker DK, Shalita A, Smith JG, Jr, Swann RW. A double-blind study of the effectiveness of a 3% erythromycin and 5% benzoyl peroxide combination in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:933–936. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poulin Y, Sanchez NP, Bucko A, et al. A 6-month maintenance therapy with adapalene-benzoyl peroxide gel prevents relapse and continuously improves efficacy among severe acne vulgaris patients: results of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011 Apr 1; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10344.x. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gold LS, Tan J, Cruz-Santana A, et al. A North American study of adapalene-benzoyl peroxide combination gel in the treatment of acne. Cutis. 2009;84:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gollnick HP, Draelos Z, Glenn MJ, et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a unique fixed-dose combination topical gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a transatlantic, randomized, double-blind, controlled study in 1670 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1180–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thiboutot DM, Weiss J, Bucko A, et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a fixed-dose combination for the treatment of acne vulgaris: results of a multicenter, randomized double-blind, controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Troielli PA, Asis B, Bermejo A, et al. Community study of fixed-combination adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% in acne. Skinmed. 2010;8:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andres P, Pernin C, Poncet M. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide once-daily, fixed-dose combination gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, bilateral (split-face), dose-assessment study of cutaneous tolerability in healthy participants. Cutis. 2008;81:278–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loesche C, Pernin C, Poncet M. Adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% as a fixed-dose combination gel is as well tolerated as the individual components alone in terms of cumulative irritancy. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:524–526. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zouboulis CC, Fischer TC, Wohlrab J, Barnard J, Alio AB. Study of the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of 2 fixed-dose combination gels in the management of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2009;84:223–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eichenfield LE, Jorizzo JL, Dirschka T, et al. Treatment of 2,453 acne vulgaris patients aged 12–17 years with the fixed-dose adapalene-benzoyl peroxide combination topical gel: efficacy and safety. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1395–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eady EA, Farmery MR, Ross JI, Cove JH, Cunliffe WJ. Effects of benzoyl peroxide and erythromycin alone and in combination against antibiotic-sensitive and -resistant skin bacteria from acne patients. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:331–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feldman SR, Tan J, Poulin Y, Dirschka T, Kerrouche N, Manna V. The efficacy of adapalene-benzoyl peroxide combination increases with number of acne lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]