Abstract

Objectives

To explore issues of intervention tailoring for ethnic minorities based on information and experiences shared by researchers affiliated with the Health Maintenance Consortium (HMC).

Methods

A qualitative case study methodology was used with the administration of a survey (n=17 principal investigators) and follow-up telephone interviews. Descriptive and content analyses were conducted, and a synthesis of the findings was developed. Results: A majority of the HMC projects used individual tailoring strategies regardless of the ethnic background of participants. Follow-up interview findings indicated that key considerations in the process of intervention tailoring for minorities included formative research; individually oriented adaptations; and intervention components that were congruent with participants’ demographics, cultural norms, and social context.

Conclusions

Future research should examine the extent to which culturally tailoring long-term maintenance interventions for ethnic minorities is efficacious and should be pursued as an effective methodology to reduce health disparities.

Keywords: cultural, tailoring, ethnic minorities, disparities

INTRODUCTION

There is evidence that the overall health of the US population has improved1–3 with social and behavioral interventions playing a crucial role in the process.4,5 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2006), however, has noted that ethnic minorities experience higher mortality and morbidity rates than do nonminorities. Hispanics and African Americans experience more age-adjusted years of potential life lost before age 75 than do non-Hispanic whites due to stroke, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, diabetes, and homicide.6,7 Both Hispanics and African Americans have higher rates of obesity and report lower levels of physical activity than those of non-Hispanic whites.6–8 Asian populations suffer a higher incidence of tuberculosis, certain types of cancer, and Hepatitis B than do non-Hispanic whites.9 Native Americans are more likely to report poorer health outcomes than any other ethnic group.10 In addition, disparities exist in access to health care and are associated with higher mortality rates among ethnic minority groups.1

The increasing diversification of the United States underlines the need to address ethnic health disparities and weigh the significance of using a cultural sensitivity paradigm in the design and dissemination of health interventions targeting minorities. Whereas ethnic minorities currently constitute about one third of the US population, it is expected that by 2050 minorities will become the majority and represent 54% of the national population. It is also estimated that by 2050, the Hispanic population will grow almost 3-fold (from 49 million to 132.8 million); the Asian group will more than double from 14.4 million to 34.4 million; and the African American population will increase almost 43% (to become 56.9 million).11 If ethnic minorities continue to experience health disparities,1,2,6–10 the estimated population growth of these groups may exacerbate the negative impact of these disparities.

Responding to both the IOM recommendation to eliminate disparities and the NIH mandate for a more systematic inclusion of ethnic minorities in research12,13 to reflect national demographic trends will require, among other public health strategies, the diffusion of effective health interventions that are culturally sensitive to ethnic minorities.

This paper through a case study approach aimed to explore ways in which the Health Maintenance Consortium (HMC) (a collective of 21 NIH-sponsored research projects) addressed issues of cultural tailoring explicitly for ethnic minority participants. We wanted to understand to what extent, and what types of, culturally sensitive strategies were used by the consortium for tailoring maintenance health interventions that were inclusive of ethnic minority participants.

This case study is based on information and experiences shared by researchers who participated in the HMC. Consortium researchers were funded by NIH to conduct studies to test different theoretical models for achieving long-term behavioral change. Intervention outcomes in these studies included lifestyle behaviors associated to chronic disease (ie, eating behaviors, physical activity, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption), more risky behaviors (ie, suicide, drug abuse, and HIV-related sexual behaviors), and preventive practices (ie, mammography and mental health screening).

Cultural Sensitivity Paradigm

The cultural sensitivity paradigm guiding the process of intervention tailoring or adaptation for diverse groups in public health and behavioral research has emerged from multiple disciplines, including health communication,14,15 psychology,16 substance abuse prevention,17–23 HIV research,24,25 and health care systems.26–30 The paradigm is not only consistent with the movements of patient-centered care and the chronic care model,31 but its relevance is also underscored within the health-disparity literature addressing ethnic disparities.2,28,30,32

The concept of cultural sensitivity has been used interchangeably as cultural competence, cultural appropriateness, or cultural consistency. Although there is not a single theoretical framework or a standard definition in reference to the cultural sensitivity paradigm, we defined the concept as “the extent to which ethnic and cultural characteristics, experiences, norms, values, behavioral patterns, and beliefs of a target population, and relevant historical, environmental, and social forces” (p.493) are taken into account in intervention design, implementation, and assessment.33

The application and impact of the cultural sensitivity paradigm has also been investigated. Considerable research supports the notion that addressing the individual needs and sociocultural context of ethnic minorities in behavioral interventions results in statistically significant health-outcome modifications among participants.34–39

Despite the emergence of cultural frameworks and the evidence showing that culturally tailored interventions are effective in improving, in the short term, the health status of ethnic minorities,34–39 there is paucity of studies examining cultural sensitivity applications in long-term maintenance of behavior change in minority health research. This case study, therefore, was proposed as an instructive exercise to gain insights on culturally sensitive issues as addressed by HMC researchers.

Background of the Health Maintenance Consortium

The case study consortium was established in 2004 with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The HMC is a collective of 21 behavioral research projects focused on understanding the long-term maintenance of behavior change as well as identifying intervention components for achieving sustainable health promotion and disease prevention. Coordinated by the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, the HMC comprised NIH administrators, 21 research investigators in the United States, and the HMC Resource Center program staff and advisors.

METHODS

A qualitative case study methodology was used for the study. The data collection process consisted of 2 phases: a descriptive analysis of data from a survey administered to 17 HMC principal investigators (PIs) and telephone interviews with 4 HMC PIs to follow up on issues of cultural sensitivity specifically related to ethnic minority participants.

Survey

Using a community-based participatory approach, a task force was established as part of the HMC activities to investigate the role that different intervention strategies played in the long-term maintenance of behavior change. The task force comprised 9 HMC members, including HMC PIs, advisors, and staff and NIH administrators. We all participated on a voluntary basis. The goal of the task force was to compile an inventory of interventions for projects affiliated with the HMC and to identify intervention components. Using a consensus process, the task force designed a structured 52-item questionnaire to be administered to HMC PIs conducting studies that tested the effects of long-term interventions. The task force also established the content validity of the questionnaire. The survey instrument was then pilot tested to assure it met the group’s aim and to test its readability and comprehension. The instrument was administered via e-mail to 21 PIs. A total of 17 PIs responded. The survey queried the PIs about the characteristics of their interventions, including topics related to ways in which the intervention was tailored to be culturally sensitive.

For purposes of this case study, we examined data obtained from responses to only 6 close-ended items included in the instrument survey. These 6 items were related to cultural sensitivity (as shown in Table 1). The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Survey Instrument Items and Interview Themes

Survey instrument items related to cultural sensitivity (the list of possible responses is not shown):

|

Theme guide with open-ended questions used in follow-up interviews:

|

Follow-up Interviews

In addition to analyzing the survey data collected by the task force, authors of this paper also conducted telephone interviews with 4 HMC PIs to expand on issues of cultural-tailoring processes applied to ethnic minority groups. The interviews were based on a theme guide (Table 1).

Principal investigators who responded to the survey (n=17) were asked to state via e-mail whether or not they tailored their interventions to make them culturally sensitive for ethnic minority participants. Of the 17 PIs who replied to the e-mail inquiry, 4 responded affirmatively. One of the interviews was related to an intervention not affiliated to HMC, but was nevertheless considered because the PI culturally adapted the HMC-related intervention to an ethnic minority group. A description of the 4 studies is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies Included in the Interview Data Analysis

| Study 1. HIV Prevention Maintenance for African American Teens. Aim: To determine the efficacy of an HIV maintenance prevention intervention to sustain condom-protected sexual intercourse among African American females aged 14–20 years, over an 18-month follow-up period. |

| Study 2. !Viva Bien! This project was a cultural adaptation for Latinas of the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program (MLP) (affiliated with HMC). Aim of the MLP and !Viva Bien!: To improve multiple health behaviors in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes |

| Study 3. Finding the M.I.N.C. for Mammography Maintenance. Aim: To identify the minimum intervention needed for change for annual mammography use and maintenance among women of diverse occupations and backgrounds. |

| Study 4. Weight Loss Maintenance in Primary Care. Aim: To evaluate 2 interventions for weight loss maintenance in primary care patients recruited by their physicians. |

After written consent was obtained, interviews with the 4 PIs were conducted by telephone and recorded. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. For Study 2, the PI and a research team member were interviewed, but both interviews were treated as one set of data or transcript. Transcripts were reviewed independently. Then, using a focused coding process in which concepts that emerged throughout the data were identified, transcript findings were combined into larger, overreaching themes.40 This study was approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Survey instrument data

The descriptive analysis of survey responses revealed that the most frequent tailoring strategy was matching intervention schedules with participants’ availability (76.5%). Another prevailing strategy was delivering the intervention in accessible locations to participants or meeting their transportation needs (64.7%).

Half of the HMC projects tailored the interventions based on formative research. In addition, 8 studies (47%) reported that their interventions were delivered by individuals who were knowledgeable of the cultural views and values of participants (it is worth noting that the descriptive data did not capture details or examples of such cultural views and values; Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of HMC Projects (n=17) by Intervention Tailoring Strategy

| Intervention tailoring strategies a | %b |

|---|---|

| The design of the treatment strategies was based on formative research experiences, norms, beliefs, values, behavioral patterns, socioeconomic level, or other cultural characteristics of participants. | 58.8 |

| Recruitment staff are from the participants’ community. | 11.8 |

| The treatment strategies include activities that involve family and friends of participants. | 29.4 |

| The intervention delivery setting was selected to make it accessible to, or meet the transportation needs of, participants (eg, community setting, church, neighborhood). | 64.7 |

| The delivery of the intervention is facilitated by individuals or organizations from the participants’ community (eg, community health workers, community leaders). | 11.8 |

| The intervention delivery schedules were adapted to match the participants’ availability. | 76.5 |

| The treatment strategies address trust issues related to research participation. | 23.5 |

| The interventionists are knowledgeable of cultural views and values of participants. | 47.1 |

| The interventionists’ racial/ethnic background is matched to the participants. | 11.8 |

| The interventionists’ age is matched to the participants. | 5.9 |

| The interventionists’ gender is matched to the participants. | 17.6 |

| Recruitment was done in minority newspapers, churches, and community events. | 5.9 |

| Intervention content was based on the socioeconomic status of the participants. | 35.3 |

| Intervention content was developed to match the participants’ cultural views and values. | 23.5 |

| Intervention content was developed to match the participants’ literacy level. | 58.8 |

| Intervention content was developed in the preferred language of the participants. | 23.5 |

This is the list of statements as presented in the survey instrument. Survey respondents were asked to check each statement that applied to their study.

Percentage of respondents that checked the corresponding item box

Almost 2 thirds of the HMC studies developed intervention contents that met the literacy level of the target population (Table 3). All interventions were delivered in English, and only one reported having an interpreter in the intervention classes.

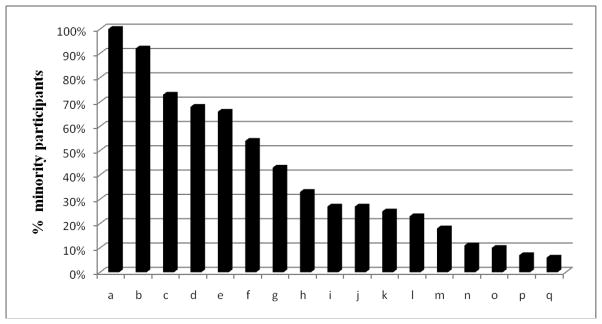

All 17 projects included some ethnic minority participants. The average percentage of ethnic minority inclusion was 40.18%, and the range was from 6% to 100%, with only one study having all participants from an ethnic minority group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Ethnic Minority Participants by Study (n=17)

Follow-up Interview Data

Three major themes emerged from data obtained through the follow-up interviews: the importance of formative research in cultural tailoring, intervention cultural components, and main lessons learned.

Formative Research

The intervention tailoring process in 3 projects was informed by formative research including literature searches, focus groups, interviews, theatrical testing, and pilot testing:

“You can read the literature, but unfortunately, even the African American community is not homogeneous. So if you were dealing with Caribbean Americans, African Americans, or Africans, people who have lived in the North versus the South, there really are some differences that need to be taken into account. The only way to really get at those nuanced differences is by doing some in depth formative work” (Study 1).

Study 2 began the formative process by searching the literature for “some insights into things that we should consider changing from the parent program [The Mediterranean Lifestyle Program]. There could be some factors unique to Latinas that would make a difference in terms of learning self- management procedures. In that literature we frankly didn’t find anything that was very profound.”

Study 2 also conducted focus groups, but again “we were left with the sense that the overall format in the parent program was feasible for implementation with Latinas. Childcare and transportation were 2 of the areas the participants thought we should be sensitive to because they thought the intervention would be rather demanding.”

Study 1 conducted 2 pilots assessing the feasibility and cultural appropriateness of the program: “The pilot studies were sort of a dress rehearsal. We went through all the procedures, including randomization, and we delivered our intervention, and at the end of each intervention session, that’s when we requested specific information about the session. Were the activities appropriate? Were the health educators appropriate?”

Study 2 also pilot tested shortened versions of the intervention: “We were able to pilot the measures to see if they were clear and could be understood by the women--whether the literacy level was appropriate. We piloted the recruitment procedures. Probably the biggest thing we learned from the pilot was that we needed to add a family component to the intervention.”

Study 3 conducted interviews and focus groups to find out women’s perceptions about their experiences with mammography screening.

Study 1 used theatrical testing “where we had members of the community actively participating as consultants in each of the components of the study, and then evaluated it for its appropriateness, in terms of linguistic and cultural relevance.”

Intervention Components

The interviewees highlighted the main components they included to make the interventions culturally sensitive. These components were related to the demographic characteristics, cultural norms, and social environment of participants.

Demographic characteristics of delivery agents and participants were matched in some of the studies. Study 1 hired health educators who were African American females, and about 95% of the research team was also African American. Study 2 presented intervention materials in English and Spanish and had bilingual staff.

Although Study 3 did not plan to match gender characteristics of interventionists and participants, the intervention counselors were of mammography-seeking age, a similar age of participating women: “We wanted to have telephone advisors and counselors who were mature and who could relate to women.”

Taking into account the cultural norms of the target population was also relevant in studies 1 and 2 when selecting intervention activities and materials:

“We wanted to look at symbolism because clearly that is an important cultural component. Even the logo that we eventually used was symbolic of African culture” (Study 1).

Study 2 also took into account Hispanic cultural symbolism in some group activities, in which “all the decorations had a fiesta style.”

In Study 1, the researchers emphasized the importance of cultural congruence:

“For example, in our study one of the key themes was to be safe for yourselves, your family, and your community. In African American communities young women are important, not only to their family, but to their community. So the whole issue of altruism, collectivism, which is an African American trait, was emphasized” (Study 1).

Studies 2 and 4 included ethnic foods of the target population. In Study 4, interventionists taught African Americans “ways to either avoid fried food or preparing that food in ways that didn’t involve so many extra calories.”

In studies 1 and 2, culturally sensitive music and poetry were also incorporated into the intervention. The researcher from Study 1 stated the intervention included materials from African American artists such as the musician Lauren Hill and the poet Maya Angelou. Study 2 introduced music that participants would like: “We definitely had a Latin flavor to the music that we used for the physical activity sessions. We had salsa dancing at our different functions.”

The social context of the target population was another intervention component in 3 studies:

“Our intervention addressed the realities of being an African American woman. What are the threats in the community? What are the barriers to practicing safer sex? We also addressed future orientation as perceived by African Americans. A lot of them don’t perceive they have a future. You also have to address gender norms, critical issues that not only in African-American communities are prominent, but in general” (Study 1).

Study 2 included social support groups for participants and also met their transportation needs to attend sessions: “Women came together at the end of each of our group sessions, and had an opportunity to socialize and talk about their successes and failures with the program, which we felt was a critical element in maintaining their involvement in the program.”

In Study 4, the weight-control specialist provided nutrition advice to participants based on their cultural background or the neighborhood: “Our whole approach to weight-control programs is focused much more on the food environment and much less on the psychological characteristics of our participants. There were was a big difference between African Americans and Caucasians in terms of the food environment. That was at least partly based on the fact that in general the African Americans came from lower social economic levels and lived in different neighborhoods; therefore they had less money to spend on healthy foods and healthy foods were less available to them.”

Main Lessons Learned

Two themes emerged as common lessons among interviewees: the tailoring process has to be individually oriented and is time-consuming.

“I think that is one reason why our interventions are not nearly as effective as they could be, because they are so broad. By designing a really broad intervention it is really targeted at no one” (Study 1).

The PI of Study 1 also mentioned that researchers need to understand the target population and involve individuals from this population in the intervention design, implementation, and evaluation: “The more tailoring you do and the more personalized you make it, the better it is. So there are different levels of tailoring. Tailoring is not a yes or no issue. Think of tailoring as a continuum. Your intervention has to target an individual, not a group.”

The main lesson for researchers in Study 2 was acknowledging the heterogeneity of the target population:

“If you have a group of Latinas living in Denver, in terms of acculturation and nationality there is a lot of diversity. I think the main lesson is that with tailoring you have to be extremely flexible. We incorporated family night because of our pilot study participant feedback, but there were some women who said, ‘I don’t care what my family thinks, I’d rather have an evening where they stay at home and I can just enjoy my time with the other women here.’ In terms of language and bilingualism, we have monolingual Spanish speakers, monolingual English speakers, and people who are bilingual. I think the lesson is to not make narrow stereotyped assumptions because there is so much diversity in each ethnic group” (Study 2).

For researchers of Study 3, the culturally sensitive process “is laborious and time consuming.” Additionally, in retrospective Study 3 researchers would have oversampled racial and ethnic minorities in order to “do some better comparisons across race and ethnicity.”

The PI of Study 4 also emphasized the importance of an individually oriented tailoring process:

“We have to realize that our interventions don’t work very well with everyone. But I don’t think it has anything to do with tailoring. It has to do with the huge difficulty everyone has in changing their habits, food choices, given that we are living in an extremely unhealthy food environment. So when you think about behavior modification procedures, they are all about tailoring to begin with. In other words, the whole idea is teach general principles, but then help people apply those principles to their particular life situations, and that is true regardless of who they are. Participants want a helper who addresses their particular challenges, as opposed to just applying a one size fits all” (Study 4).

DISCUSSION

Our case study analyses indicate that all projects affiliated with the HMC included ethnic minority participants, as required by NIH funding guidelines. Also, most of the PIs reported to having used individual tailoring strategies to make their interventions more responsive to their target populations regardless of the ethnicity background of participants. This case study highlights that intervention tailoring explicitly applied to ethnic minorities was rarely performed in the HMC interventions.

We found that culturally sensitive tailoring efforts in the HMC projects focused mainly on conducting individual tailoring to meet particular needs of target populations (ie, easy access to classes, transportation, adequate schedules, literacy level), without further tailoring the interventions more specifically for their minority participants. In other words, in most HMC projects both minority and nonminority participants were exposed to the same tailored intervention. Notwithstanding this finding, the practice of individual tailoring is of great significance in behavioral research. Although our study did not investigate the effects of intervention tailoring on health outcomes, considerable research shows that tailoring efforts yield effective changes in behavioral health outcomes.34–39,41

From the follow-up interviews with PIs who worked to make their interventions culturally sensitive to an ethnic minority group, we learned that formative research plays a key role in the tailoring process. This finding is consistent with previous research.15,34,35,42 Additionally, we found that the tailored interventions for ethnic minorities included the following cultural components: materials and activities that were congruent with the participants’ demographics (ie, ethnicity, language, and age), cultural norms and practices (ie, ethnic foods, music), and social environment (ie, socioeconomic status, social support need, gender bias). These findings resonate with studies in the literature that also examined components of culturally sensitive interventions for minorities.27,28,31 Finally, the PIs highlighted that cultural tailoring for ethnic minorities has to be individually based and is time-consuming.

This study has limitations due to its descriptive and qualitative nature and specific focus on HMC-affiliated projects. Despite its limitations, this case study is instructive in that it provides valuable insights into the individual and cultural tailoring process of long-term behavioral interventions. Although it is worth noting that the main goal of the HMC-affiliated projects was not to address health disparities, further steps for HMC members, and behavioral scientists in general, may be to explore the extent to which tailoring or adapting long-term maintenance behavior interventions for ethnic minorities can be efficacious and reduce health disparities.

In conclusion, our case study showed the adoption of individual tailoring in general, but less ethnicity–specific tailoring in the HMC projects. Case study findings may suggest the need to address a major research and practice gap. The maintenance behavior research and health disparities field can benefit from more attention to the application of the cultural sensitivity paradigm. There are some research questions that require our immediate attention. To what extent do processes of culturally tailoring long-term interventions for ethnic minorities change and sustain their health outcomes? What are effective tailoring strategies in maintenance interventions for ethnic minorities?

As the United States becomes more ethnically diverse and health disparities persist, the application of the cultural sensitivity paradigm in behavioral research with minorities will become increasingly important. In a review of population-based interventions engaging ethnic minorities in healthy living, Yancey et al43 call for rigorous trials in multi-ethnic and ethnic-specific settings to obtain sufficient evidence on the effectiveness of tailored interventions targeting these diverse groups. The IOM also underlines that culturally appropriate education programs are key in comprehensive, multilevel strategies to eliminate ethnic health inequalities.2 In addition, previous research confirms that behavioral interventions tailored to meet the cultural and social context of ethnic minorities are more likely to increase the external validity of interventions,42 accelerate advances in minority health,32,44 and address health disparities.30,32 Previous systematic reviews, which present evidence of the effectiveness of interventions tailored for minority groups,45,46 conclude that the tailoring process should consider community involvement, face-to-face interventions, inclusion of lay facilitators, and formative research activities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH—National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (3 R01HD047143-01S1).

Contributor Information

Nelda Mier, Email: nmier@tamhsc.edu.

Marcia G. Ory, Email: MOry@srph.tamhsc.edu.

Deborah Toobert, Email: deborah@ori.org.

Matthew Lee Smith, Email: matlsmit@tamu.edu.

Diego Osuna, Email: Diego.Osuna@kp.org.

James McKay, Email: mckay_j@mail.trc.upenn.edu.

Edna K. Villarreal, Email: evillarreal@srph.tamhsc.edu.

Ralph J. DiClemente, Email: rdiclem@sph.emory.edu.

Barbara K. Rimer, Email: brimer@unc.edu.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Unfinished business. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. Examining the health disparities research plan of the National Institutes of Health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. The National Academies Press; 2002. [Accessed August 25, 2009]. Available at: http://books.nap.edu/books/030908265X/html/index.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao Y, Tucker P, Okoro CA, et al. Reach 2010 Surveillance for health status in minority communities --- United States, 2001–2002. MMWR Surv. 2004;53(6):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ory MG, Jordan PJ, Bazzarre T. The Behavior Change Consortium: Setting the stage for a new century of health behavior-change research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(5):500–511. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syme SL. Investments in research and intervention at the community level. In: Berkman L, editor. Through the Kaleidoscope: Viewing the Contributions of the Behavioral and Social Sciences to Health. Washington DC: National Academic Press; 2002. pp. 42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health disparities experienced by Hispanics ---United States. MMWR. 2004;53(40):935–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health disparities experienced by Black or African Americans--United States. MMWR. 2005;54(1):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed September 1, 2009];US Physical activity statistics. 2007 Available at: http://apps.Nccd.Cdc.Gov/pasurveillance/democompareresultv.Asp?State=1&cat=4&year=2007&go=go#result.

- 9.Management Sciences for Health. [Accessed July 3, 2009];The provider’s guide to quality & culture: Asian Americans & Pacific Islanders: Health disparities. 2003 Available at: http://erc.Msh.Org/mainpage.Cfm?File=7.2.0.Htm&module=provider&language=english.

- 10.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics. 356. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2005. Health Characteristics of the American Indian and Alaska Native Adult Population: United States, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Population Projections. National Population Projections. Released 2008 (based on census 2000). Summary tables. Table 4. [Accessed November 8, 2009];Projections of the population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United states: 2010 to 2050. Available at: http://www.Census.Gov/population/www/projections/summarytables.Html.

- 12.Singer BH, Ryff CD National Research Council. Committee on Future Directions for Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at The National Institutes of Health. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. New Horizons in Health: An Integrative Approach. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caban CE. Hispanic Research: Implications of the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on Inclusion of Women and Minorities in Clinical Research. J Nat Cancer Inst Monogr. 1995;18:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Ann Rev Pub Health. 2004;25:429–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrera M, Gonzalez-Castro F. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13:311–316. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, et al. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. J Community Psychol. 2002;28(3):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prev Sci. 2002;3(3):241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ringwalt C, Bliss K. The cultural tailoring of a substance use prevention curriculum for American Indian Youth. J Drug Educ. 2006;36(2):159–177. doi: 10.2190/369L-9JJ9-81FG-VUGV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Martinez CR., Jr The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci. 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Pantin H, et al. Substance abuse prevention intervention research with Hispanic populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(Suppl 1):S29–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro FG, Harmon MP, Coe K, Tafoya-Barraza HM. Drug prevention research with Hispanic populations: theoretical and methodological issues and a generic structural model. NIDA Res Monogr. 1994;139:203–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro FG, Shaibi GQ, Boehm-Smith E. Ecodevelopmental contexts for preventing type 2 diabetes in Latino and other racial/ethnic minority populations. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):89–105. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9194-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson BDM, Miller RL. Examining strategies for culturally grounded hiv prevention: a review. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(2):184–202. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.184.23838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinh-Thomas P, Bunch MM, Card JJ. A research-based tool for identifying and strengthening culturally competent and evaluation-ready HIV/AIDS prevention programs. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(6):481–498. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.7.481.24050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell JC, Campbell DW. Cultural competence in the care of abused women. J Nurse Midwifery. 1996;41(6):457–462. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(96)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, et al. Culturally competent healthcare systems. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(Suppl 3):S68–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O., 2nd Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suh EE. The model of cultural competence through an evolutionary concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2004;15(2):93–102. doi: 10.1177/1043659603262488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):S181–S217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, et al. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(Suppl 1):S7–S15. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):477–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Resnicow K, Braithwaite RL, Dilorio C, Glanz K. Applying theory to culturally diverse and unique populations. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Joseey-Bass; 2002. pp. 485–509. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mier N, Ory MG, Medina AA. Anatomy of culturally sensitive interventions promoting nutrition and exercise in Hispanics: a critical examination of existing literature. Health Promot Pract. 2009 doi: 10.1177/1524839908328991. Online First 0: 1524839908328991v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown SA, Hanis CL. Culturally competent diabetes education for Mexican Americans: The Starr County Study. Diabetes Educ. 1999;25(2):226–236. doi: 10.1177/014572179902500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(4):623–634. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarkisian CA, Brown AF, Norris KC, et al. A systematic review of diabetes self-care interventions for older, African American, or Latino adults. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(3):467–479. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charmaz K. Grounded theory. In: Emerson RM, editor. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press Inc; 2001. pp. 335–352. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Resnicow K, Davis R, Zhang N, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on ethnic identity: results of a randomized study. Health Psych. 2009;28(4):394–403. doi: 10.1037/a0015217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995;23(1):67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yancey AK, Kumanyika SK, Ponce NA, et al. Population-based interventions engaging communities of color in healthy eating and active living: a review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(1):A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marin G, Marin BV. Research with Hispanic Populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glazier RH, Bajcar J, Kennie NR, et al. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1675–1688. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arblaster L, Lambert M, Entwistle V, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of health service interventions aimed at reducing inequalities in health. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1996;1(2):93–103. doi: 10.1177/135581969600100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]