Abstract

Gradients of chemorepellent factors released from myelin may impair axon pathfinding and neuro-regeneration after injury. Analogous to the process of chemotaxis in invasive tumor cells, we found that axonal growth cones of Xenopus spinal neurons modulate the functional distribution of integrin receptors during chemorepulsion induced by myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG). A focal MAG gradient induced polarized endocytosis and concomitant asymmetric loss of β1-integrin and vinculin-containing adhesions on the repellent side during repulsive turning. Loss of symmetrical β1-integrin function was both necessary and sufficient for chemorepulsion, which required internalization by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Induction of repulsive Ca2+ signals was necessary and sufficient for the stimulated rapid endocytosis of β1-integrin. Altogether, these findings identify β1-integrin as an important functional cargo during Ca2+-dependent rapid endocytosis stimulated by a diffusible guidance cue. Such dynamic redistribution allows the growth cone to rapidly adjust adhesiveness across its axis, an essential feature for initiating chemotactic turning.

During development of the nervous system, axons project from neuronal cell bodies and connect with the appropriate target cells. Nerve growth cones at the tips of extending axons mediate this pathfinding through the extracellular matrix (ECM) by sensing gradients of chemotropic factors and initiating attractive or repulsive steering1. Chemotactic growth cone guidance is also important in the context of nervous system injury, as factors released from the breakdown of myelin may act as chemorepellents and inhibit axon elongation, thereby preventing functional recovery2. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that mediate axon growth inhibition and chemorepulsion could provide important insights for developing strategies to enhance neuro-regeneration after injury or degenerative disease.

Many axon guidance cues, cognate receptors, and early messengers have been identified, yet our understanding of the cellular processes underlying growth cone chemotaxis remains incomplete. Current models rely heavily on cytoskeletal rearrangements, but in vivo studies have demonstrated that regulated adhesion to the ECM is also critical for proper pathfinding1,3–5. The body of evidence, derived largely from non-neuronal cell types, indicates that ECM-adhesions can be regulated by non-mutually exclusive mechanisms. These include modulation of ECM-receptor affinity for the substrate, recruitment of adaptor and signaling proteins, and the spatial distribution of ECM-receptors. For instance, the diffusible guidance cue semaphorin 3A (sema3A) can both reduce the activation state of β1-integrin receptors6 and promote disassembly of paxillin-containing adhesions in the growth cone7,8. Whether a diffusible cue can modulate the spatial distribution of integrin receptors during growth cone turning is unknown, although recent findings indicate that the spatial distribution of integrin receptors must be regulated during fibroblast and invasive cancer cell migration9. In these migrating cells, internalization of integrin receptors may facilitate disassembly of adhesions10.

The major factors in myelin that inhibit axon extension and repel migrating growth cones are myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMgp), and Nogo. The functional receptors and complex signaling mechanisms for these structurally unrelated factors are still being defined11–14. Previous findings have shown that a gradient of MAG can stimulate NgR-dependent asymmetric focal Ca2+ signals in the growth cone that are necessary for chemorepulsion15,16. These low-amplitude Ca2+ signals are sufficient to induce growth cone repulsion when applied asymmetrically17,18, although the downstream effectors are largely unknown19. Because intracellular Ca2+ is a central regulator of vesicle dynamics in neurons20,21, we hypothesized that a gradient of MAG induces asymmetric endocytosis across the axis of the growth cone to remodel adhesions and initiate repulsive turning.

We here show that a focal gradient of MAG can induce polarized endocytosis concomitant with asymmetric redistribution of β1-integrin and vinculin-containing contact adhesions in axonal growth cones. Polarized integrin function was both necessary and sufficient to induce chemorepulsive growth cone steering. Finally, the endocytic removal of β1-integrin was positively regulated by Ca2+ signaling and required clathrin-mediated endocytosis, which was also necessary for MAG-induced chemorepulsion. These findings are the first demonstration that a diffusible guidance cue can direct trafficking of integrin receptors to redistribute ECM-adhesions asymmetrically during chemotactic growth cone guidance.

Results

A MAG gradient polarizes endocytosis in nerve growth cones

To test whether a gradient of MAG stimulates polarized endocytosis during repulsive growth cone turning, we devised a live-cell assay to visualize the formation of endocytic vesicles by transiently labeling the growth cone plasmalemma with the lipophilic styryl dye FM 5-95. A brief dye pulse from a micropipette positioned in front of the leading edge of the growth cone labeled the surface membrane and the fast destaining properties of FM 5-95 allowed us to rapidly monitor endocytic events using confocal microscopy (1 Hz) in real time. We observed a surprisingly rapid rate of constitutive endocytosis in motile growth cones, which was often focused at “hot spots” in the peripheral domain and near the base of filopodia (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). The formation of endocytic vesicles was stochastic, with a random distribution across the lateral axis of the growth cone (Fig. 1c–e, i). The focal spots of endocytic activity lasted tens of seconds and nascent endocytic vesicles moved rapidly from the plasmalemma into the growth cone central domain (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). Similar assays using fluorescent dextran as a fluid-phase marker confirmed that FM 5-95 containing structures were internalized vesicles and tubular endosomes (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Videos 3–5). These real-time observations are reminiscent of early endocytic profiles detected in electron micrographs of chick growth cones22.

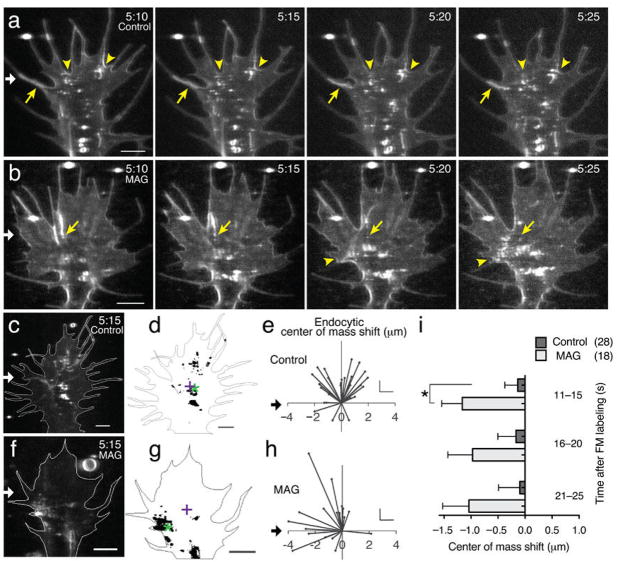

Figure 1. MAG-gradient stimulated asymmetric membrane internalization.

(a,b) A microscopic gradient of vehicle solution (a) or MAG (b) was applied to the growth cone of a Xenopus spinal neuron from a micropipette (200 μg/ml; white arrow) for the times indicated (min:s; see Methods). After a 5-min application, the surface membrane was labeled by a focal pulse of FM 5-95 (t= 5:00), which was delivered from a micropipette positioned directly in front of the growth cone leading edge. Time-lapse confocal images (t= 5:10–5:25) demonstrate rapid formation of large tubules (yellow static arrows) and hot spots of endocytosis (yellow arrowheads). See Supplementary Videos 1 and 6. Scale bars, 5 μm. (c,f) Representative confocal images show the spatial distribution of endocytosis 15 s post dye labeling and after stimulation (white arrow) with a control (c) or MAG (f) gradient for the time indicated (min:s). See Supplementary Video 7. Scale bars, 5 μm. (d,g) Binary images from (c,f) show the MAG-induced shift in center of endocytic activity (center of mass, green *) relative to the center of the growth cone (centroid, +). (e,h) Summary of endocytic center of mass shift as in (d,g), respectively. Trajectories depict the shift in endocytic center of mass for individual growth cones 15 s post-dye labeling. The origin is the center of each growth cone. Scales: x = 1 μm, y = 2 μm. (i) The average shift in the endocytic center of mass for all time points after FM-dye labeling (5-s bins). Data are the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 18, 28; * P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U-test).

Focal application of a MAG gradient from a second micropipette positioned to one side of the growth cone caused a notable shift in endocytic vesicle formation towards the side nearer the MAG point source (Fig. 1b, f; Supplementary Videos 6 and 7). We measured the asymmetry of endocytosis by calculating the difference in the center of mass of labeled endocytic vesicles from the spatial center of the growth cone. Using this method, we found that endocytic events were asymmetrical along the lateral axis of the growth cone, as measured 5 min after the onset of the MAG gradient, before the growth cone had executed repulsive turning (Fig. 1g–i). This asymmetry was most detectable within 15 s of surface labeling, most likely because significant retrograde movement of nascent endocytic vesicles occurred over time leading to a more Gaussian distribution. Such polarized endocytosis may facilitate the removal of surface receptors, membrane-associated proteins, and bulk membrane preferentially from the lagging edge in the early events initiating repulsive growth cone turning.

MAG stimulates endocytosis of β1-integrin

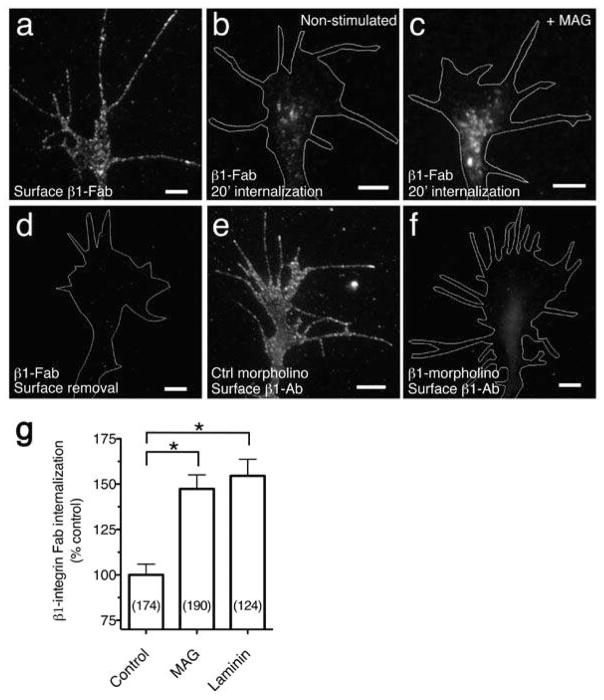

Because components of integrin-containing adhesions can mediate axon pathfinding in vivo4 and endocytosis of β1-integrin participates in the disassembly of focal adhesions in migrating fibroblasts10, we tested whether β1-integrin is a functionally relevant cargo in the nascent endocytic vesicles stimulated by MAG. To monitor the trafficking of β1-integrin from the surface membrane, we generated β1-integrin antibody Fab fragments (β1 Fab) to directly measure integrin endocytosis while avoiding clustering and activation induced by whole antibodies. Xenopus spinal neurons grown on fibronectin were incubated with β1 Fab at 8°C to prevent endocytosis while allowing surface binding (Fig. 2a). After a defined internalization period (20 min, see Methods), we removed noninternalized β1 Fab by a low pH wash to reveal β1-integrin in endocytic vesicles (Fig. 2b). Uniform treatment with MAG during the internalization period significantly increased the level of endocytosed β1 Fab compared to controls (Fig. 2c, g). Treatment with soluble laminin, which has been shown previously to bind directly and downregulate integrin heterodimers23, also stimulated the rate of β1-integrin endocytosis (Fig. 2g). Addition of the fluid-phase endocytosis marker fluorescent dextran during the internalization period co-labeled endocytic compartments containing β1 Fab (Supplementary Fig. 2), which confirmed these as intracellular rather than integrin clusters on the plasmalemma. Moreover, performing the low pH wash immediately after the surface-binding step, without internalization, effectively removed surface β1 Fab (Fig. 2d). The β1 antibody was specific toward Xenopus β1-integrin, since knocking down expression of β1-integrin with a morpholino oligonucleotide significantly decreased binding to the growth cone surface as measured by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. 3). Treatment with MAG had no effect on the binding of β1 Fab to the growth cone plasmalemma (108.2% ± 8.1 s.e.m., n = 89) compared to vehicle-treated controls (100.0% ± 8.1, n = 59; P = 0.55, Mann-Whitney U-test). Additionally, MAG treatment had no significant effect on fluid-phase endocytosis of fluorescent dextran in growth cones on either ECM or non-ECM substrates (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating that MAG-stimulated internalization of β1-integrin is not secondary to stimulation of a nonselective bulk endocytic process.

Figure 2. MAG stimulated endocytosis of β1-integrin.

(a) Fluorescence image shows β1 Fab specific to the extracellular domain of β1-integrin bound to the surface of a Xenopus spinal neuron growth cone at 8°C, prior to internalization or surface removal. (b,c) Endocytosed β1 Fab after surface binding as in (a) and treatment with BSA vehicle (b) or MAG (1 μg/ml; c) during a 20-min internalization period. Any remaining surface-bound Fab was removed with a low pH wash. (d) Removal of surface-bound β1 Fab with a low pH wash at 8°C, prior to internalization. (e,f) β1-antibody specificity assessed by immunofluorescence labeling of neurons cultured from embryos that were injected with control (e) or β1-integrin (f) morpholinos to knock down expression (quantitation in Supplementary Fig. 3. Scale bars, 5 μm. (g) Summary of β1 Fab internalization measured by the mean fluorescence intensity of growth cones treated with BSA vehicle, MAG, or soluble laminin (25 μg/ml) during the 20-min internalization period. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. from 3 independent experiments (n = the number associated with each bar; * P < 0.0001, bracketed comparisons, Mann-Whitney U-test).

MAG-induced redistribution of β1-integrin adhesions

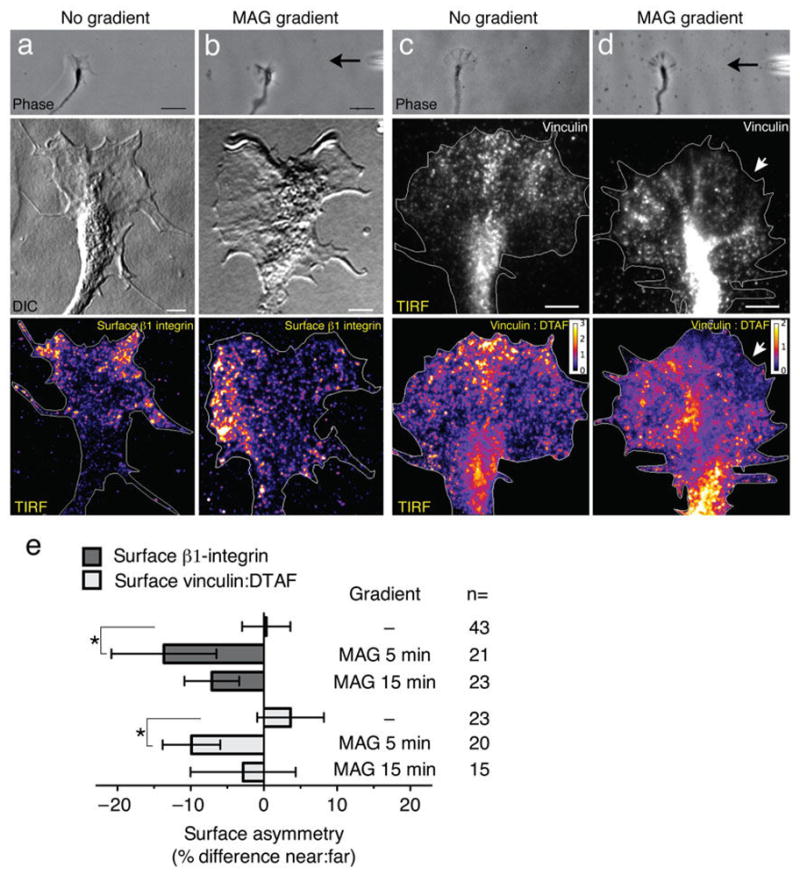

The stimulated internalization of β1-integrin by MAG may regulate the surface distribution of integrin receptors available for interactions with the ECM across the axis of the growth cone. To test for spatial asymmetry of β1-integrin during growth cone repulsion, live growth cones were treated with a MAG gradient (5 or 15 min) then immediately fixed and immunostained for surface β1-integrin using nonpermeabilizing conditions. The same growth cone was then imaged using TIRF microscopy, which enabled the detection of β1-integrin at the ventral surface specifically, where interactions with the underlying fibronectin substrate take place. In non-treated growth cones, surface β1-integrin was enriched in the peripheral domain with a symmetric distribution across the lateral axis of the growth cone (Fig. 3a). Stimulation with a MAG gradient for 5 min caused a significant shift in the distribution of β1-integrin on the growth cone surface, with decreased levels on the side nearer the MAG point source (Fig. 3b, e). This shift was less evident after a 15-min exposure to the MAG gradient (Fig. 3e), suggesting that asymmetric redistribution of β1-integrin is an early event that precedes turning of the growth cone away from the repulsive MAG gradient.

Figure 3. Polarized redistribution of ECM adhesion proteins by a MAG gradient.

(a) A control untreated growth cone imaged live (top panel) or after fixation and immunolabeling for surface β1-integrin (middle and bottom panels). The pseudo-colored image shows a symmetric distribution of β1-integrin at the ventral surface membrane as detected by TIRF microscopy. (b) Representative images (as in a) of a growth cone treated with a MAG gradient (5 min, black arrow at right) show the laterally polarized distribution of surface β1-integrin. (c) Representative images of a control untreated growth cone (as in a) except immunolabeled for vinculin (middle and bottom panels). Dual-labeling with the amine-reactive flourescein DTAF controlled for changes in growth cone thickness and the pseudo-colored ratiometric image shows vinculin:total protein, with warm colors corresponding to a ratio > 1 (see look-up table). (d) Representative images of a MAG-gradient treated growth cone (5 min) immunolabeled for vinculin as in (c). The white arrows indicate the relative loss of vinculin labeling on the side of the growth cone facing the MAG gradient. Scale bars, 5 μm (top panels) and 20 μm (middle and bottom panels). (e) Summary of β1-integrin and vinculin asymmetry measurements. Surface is defined as the growth cone plasmalemma including the cytoplasmic face. Negative values indicate a loss in mean fluorescence intensity nearest the point source (see Supplementary Fig. 5e). Data are the mean ± s.e.m. (n = number of growth cones examined; * P < 0.05, bracketed comparisons; t-test).

Integrin receptors within contact adhesions at the surface membrane recruit adaptor proteins to functionally link to the actin cytoskeleton. We tested whether a MAG gradient could polarize the recruitment and plasmalemmal distribution of vinculin, a known component of adhesion sites in the growth cone24. After treating growth cones with a MAG gradient and immunostaining for vinculin, we labeled total protein with an amine-reactive fluorescein (DTAF) in order to account for differences in growth cone thickness. Clusters of vinculin-containing puncta were present in the growth cone peripheral domain and likely represent sites of adhesion to the ECM (Fig. 3c), although much of the total vinculin staining was localized to the central domain. Regions on the ventral plasmalemma enriched in vinculin relative to total protein were clearly evident in the vinculin:DTAF ratiometric images (Fig. 3c). Whereas vinculin recruitment was symmetric in untreated growth cones (Fig. 3c, e), treatment with a MAG gradient (5 min) induced a loss of symmetry with decreased membrane recruitment of vinculin on the side nearer the MAG point source (Fig. 3d, e). This asymmetric shift in vinculin distribution at the plasmalemma paralleled that seen for β1-integrin (Fig. 3b, e). These results support the idea that a MAG gradient can induce asymmetric adhesion across the axis of the growth cone to initiate chemorepulsive turning. A MAG gradient caused no polarization in the plasmalemmal distribution of phosphofocal adhesion kinase (Y397; FAK) relative to total protein, suggesting that autophosphorylation at Y397 may not participate in the asymmetric remodeling of β1-integrin and vinculin-containing adhesion sites induced by MAG (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Chemorepulsion involves polarized integrin function

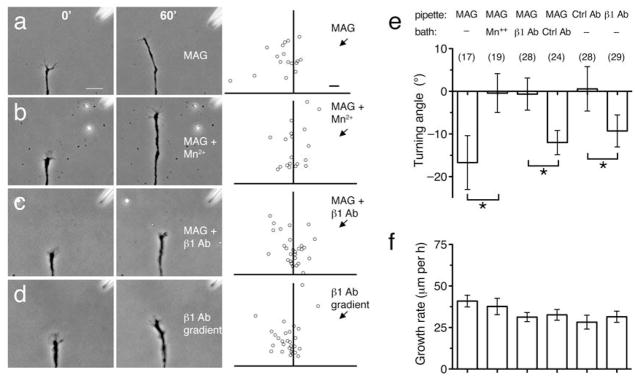

The MAG-induced redistribution of β1-integrin at the ventral surface membrane may impose polarized integrin function across the growth cone axis. Therefore, equalizing integrin function on both sides of the growth cone may abolish MAG-induced chemorepulsion. As previously shown, a microscopic gradient of MAG induced repulsive turning (−16.7° ± 6.3 s.e.m.) when focally applied at a 45° angle across the axis of the growth cone (Fig. 4a, e). Uniform treatment with Mn2+ (1 mM), an established activator of fibronectin receptor heterodimers25, abolished growth cone repulsion induced by a MAG gradient (−0.4° ± 4.6; Fig. 4b, e). Likewise, inhibiting integrin function on both sides of the growth cone by uniform treatment with a β1-integrin function-blocking antibody ablated the MAG-induced repulsion (−0.7° ± 3.8; Fig. 4c, e), whereas treatment with a normal rabbit IgG control antibody had no effect (−12.0° ± 2.8; Fig. 4e). This function-blocking antibody was specific towards β1-integrin in these Xenopus spinal neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3) and inhibited axon outgrowth when used at high doses (data not shown), but did not inhibit outgrowth at the concentration used for turning assays (Fig. 4f). In contrast, downregulating global β1-integrin levels with an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide severely inhibited axon outgrowth on fibronectin (Supplementary Fig. 6), which precluded its use in functional growth cone turning assays. Treatment with Mn2+, which increased axon length in an overnight axon outgrowth assay (Supplementary Fig. 6), had minimal effect on growth rate during the 1-hr growth cone turning assay (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4. Polarized β1-integrin function mediates growth cone repulsion by MAG.

(a–c) Phase images show a representative growth cone at the onset (left) and the end (right) of a 1-hr exposure to a MAG gradient (150 μg/ml in the pipette). Assays were done in normal saline (a), saline containing Mn2+ (1 mM; b), or saline containing a function-blocking antibody to β1-integrin (5 μg/ml; c). Scatter plots depict the end points of individual growth cone extension for all the neurons examined for each condition. The origin is the center of the growth cone at the onset of the experiment and the original direction of growth was vertical. The arrow indicates the direction of the gradient. (d) Experiment carried out in the same manner as in (a), except that a gradient of function blocking antibody to β1-integrin was applied to the growth cone (0.4 mg/ml in the pipette). Scale bars, 20 μm (phase images) and 10 μm (scatter plots). (e,f) Summary of turning angles (e) and growth rates (f) for all conditions. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. (n = the number associated with each bar; * P < 0.05, bracketed comparisons, Mann-Whitney U-test).

We next tested whether inhibiting the function of β1-integrin unilaterally would alone induce repulsive growth cone turning. Significantly, a microscopic gradient of β1-integrin function-blocking antibody (0.4 mg/ml in the pipette) was sufficient to induce growth cone repulsion (−9.3° ± 3.7) that recapitulated turning induced by MAG (Fig. 4d, e). This effect was dose-dependent as higher concentrations caused only a trend toward repulsion (−5.7° ± 4.3 at 1 mg/ml; −4.0° ± 6.0 at 2 mg/ml), likely due to saturated antibody binding on both sides of the growth cone. The estimated concentration of function-blocking antibody at the growth cone (0.5 μg/ml) was near the limit of detection by immunofluorescence microscopy (data not shown). A gradient of control antibody caused no preferential turning (0.6° ± 5.2; Fig. 4e). These findings support the notion that breaking the symmetry of integrin-containing adhesions across the growth cone is both necessary and sufficient to induce growth cone turning.

MAG stimulates surface removal of β1-integrin

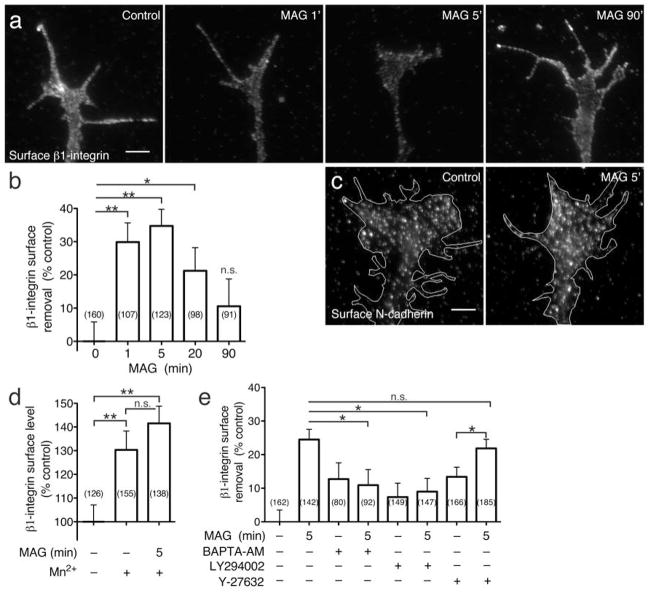

Stimulated endocytosis of β1-integrin may functionally reduce the amount of receptors available for interactions with the ECM at the growth cone plasmalemma. Alternatively, surface levels may remain unchanged or increase if rates of endocytic recycling and exocytosis increase concomitantly. To address this, we measured β1-integrin levels at the growth cone surface by immunofluorescence microscopy on nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 5a). Uniform treatment with MAG triggered a rapid reduction in total surface levels of β1-integrin within 1 min and a maximum 35% (± 5.0 s.e.m.) reduction after a 5-min treatment (Fig. 5a, b). Levels of surface β1-integrin recovered at later time points, returning to within 10% of pre-stimulation levels after a 90-min MAG treatment (Fig. 5a, b). The MAG treatment did not induce a similar downregulation of α5-integrin (Supplementary Fig. 7), one of several known alpha-subunit receptors for fibronectin. Most spinal neurons expressed low levels of α5-integrin (data not shown), suggesting the possibility that additional α-subunits may interact with β1-integrin as a functional fibronectin receptor in these neurons. To further examine whether surface levels of an unrelated receptor are also downregulated by MAG treatment, we used the same approach to measure N-cadherin levels at the growth cone plasmalemma. A 5-min treatment with MAG caused no surface removal of N-cadherin (−2.2% ± 3.7 s.e.m., n = 98) compared to vehicle treatment alone (0% ± 3.7, n = 98; P = 0.68, t-test; Fig. 5c). This is in contrast to the MAG-induced removal of β1-integrin, which was maximal at 5 min. Taken together, these results suggest that MAG induces a selective redistribution of surface receptors rather than indiscriminate bulk removal of all membrane-associated proteins.

Figure 5. MAG- induced surface removal of β1-integrin.

(a) Representative fluorescence images show surface β1-integrin immunolabeling (see Methods) on growth cones treated with BSA vehicle (control) or following stimulation with MAG (1 μg/ml) for 1 (1’), 5 (5’), and 90 (90’) min. Scale bars, 5 μm. (b) Summary of β1-integrin surface removal in growth cones treated with MAG for the times indicated. For all surface removal measurements, mean fluorescence intensities of growth cones were normalized to vehicle-treated controls and are displayed as the percentage of surface fluorescence lost upon treatment. (c) Representative fluorescence images of surface N-cadherin on growth cones treated with vehicle (control) or MAG for 5 min (MAG 5’). (d) Summary of β1-integrin surface levels in growth cones treated with MAG (5 min) with or without pretreatment with Mn2+ (30 min; 1 mM). Mean fluorescence intensities of growth cones were normalized to vehicle-treated controls and are displayed as the percentage of surface fluorescence relative to control growth cones. (e) Summary of β1-integrin surface removal in the presence of inhibitors, as indicated. Intracellular Ca2+ was buffered by pre-loading neurons with BAPTA-AM prior to MAG treatment (see Methods). Pharmacological inhibitors to ROCK (Y-27632, 25 μM) and PI3K (LY294002, 3.33 μM) were added 30 min prior to MAG treatment. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. from 3 independent experiments; n = the number associated with each bar; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.005, n.s. = no significant difference, bracketed comparisons, Mann-Whitney U-test.

The observation that uniform treatment with Mn2+ prevented chemorepulsion induced by a MAG gradient (Fig. 4b, e) prompted us to ask whether Mn2+ treatment affects the surface removal of β1-integrin. Using the same surface labeling approach, we found that a 30-min pretreatment with Mn2+ alone significantly increased β1-integrin levels at the growth cone plasmalemma compared to untreated controls (Fig. 5d). This increased surface expression of β1-integrin provides an interesting correlation to the Mn2+ stimulation of axon outgrowth measured in an overnight assay (Supplementary Fig. 6). Importantly, a 5-min MAG treatment caused no surface reduction of β1-integrin after the Mn2+ pretreatment (Fig. 5d).

We showed previously that MAG stimulates intracellular Ca2+ signals in the growth cone that are necessary for chemorepulsion15. Addition of the cell permeant BAPTA-AM, which effectively buffers intracellular Ca2+ and abolishes growth cone repulsion by MAG, also prevented the MAG-induced removal of β1-integrin from the growth cone surface (Fig. 5e). Because phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activity has also been shown necessary for growth cone repulsion by MAG (ref. 26), we tested whether PI3K signaling participates in the MAG-induced surface removal of β1-integrin. Treatment with the specific PI3K inhibitor LY294002 significantly inhibited the MAG-stimulated surface removal of β1-integrin (Fig. 5e). Activation of the NgR receptor also stimulates the rhoA-ROCK pathway, which is necessary for the MAG-induced inhibition of axon outgrowth27. Addition of the cell permeant ROCK inhibitor Y27632 did not prevent surface removal of β1-integrin induced by MAG. Treatment with BAPTA-AM, LY294002, or Y27632 alone showed a non-significant trend toward reduced surface levels (Fig. 5e). Collectively, these findings support the notion that Ca2+ and PI3K signals facilitate the endocytic removal of β1-integrin from the growth cone surface membrane, whereas ROCK activity is dispensable.

Intracellular Ca2+ signals induce integrin endocytosis

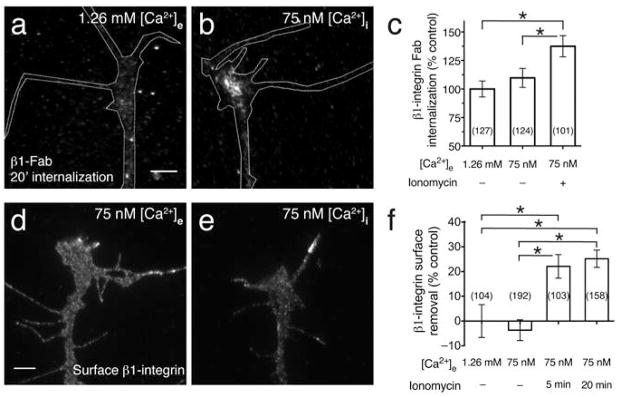

Our observation that Ca2+ signals are necessary for the MAG-induced removal of β1-integrin from the growth cone surface prompted us to investigate whether Ca2+ signals alone are sufficient to induce integrin endocytosis. A previous report demonstrated that directly inducing low-amplitude (75 nM) intracellular Ca2+ signals ([Ca2+]i) with a gradient of the Ca2+–selective ionophore ionomycin can recapitulate repulsive growth cone turning15. We utilized a similar approach to directly manipulate [Ca2+]i during the β1 Fab internalization assay. The extracellular Ca2+ level ([Ca2+]e) was preset by incubating spinal neurons in a solution containing defined concentrations of Ca2+ and EGTA. During the β1 Fab internalization period, we used ionomycin to clamp [Ca2+]i to [Ca2+]e. The resting [Ca2+]i in these neurons is ~60 nM in reduced [Ca2+]e bathing solution15,18. Internalization of β1 Fab increased when [Ca2+]i was elevated from the resting level (Fig. 6a, c) to 75 nM (Fig. 6b, c). Presetting [Ca2+]e to 75 nM in the absence of ionomycin had no effect on integrin endocytosis (Fig. 6c). Reducing [Ca2+]e to 75 nM without ionomycin caused no change in β1 Fab binding to the growth cone surface (108.8% ± 10.25 s.e.m., n = 69) compared to the controls where [Ca2+]e was set to 1.26 mM (100% ± 8.1, n = 59; P = 0.70, Mann-Whitney U-test).

Figure 6. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ regulates endocytosis of β1-integrin.

(a) Fluorescence image shows β1 Fab internalization in a control growth cone in normal saline after treatment with DMSO vehicle alone (1.26 mM [Ca2+]e). Experiment was performed as in Fig. 2a. Scale bars, 5 μm. (b) Experiment carried out as in (a) but in the presence of low Ca2+-saline (75 nM [Ca2+]e). Low-amplitude [Ca2+]i signals were induced by treatment with ionomycin during the 20-min internalization period (5 nM; see Methods). (c) Summary of β1 Fab internalization measured by the mean fluorescence intensity of growth cones treated as indicated. Data for all graphs were normalized to the normal saline controls. (d) Representative fluorescence image shows surface β1-integrin immunolabeling on a control growth cone in low Ca2+-saline (75 nM [Ca2+]e) treated with DMSO vehicle (5 min). (e) Experiment carried out as in (d) except that ionomycin was added for 5 min (75 nM [Ca2+]i) prior to fixation. (f) Summary of β1-integrin surface removal in growth cones treated as indicated. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. from 3 (c) or 2 (f) independent experiments (n = the number associated with each bar; * P < 0.05, bracketed comparisons, Mann-Whitney U-test).

To determine whether the Ca2+-induced endocytosis is sufficient to reduce β1-integrin levels at the growth cone plasmalemma, we used the surface immunolabeling assay (Fig. 5) while manipulating [Ca2+]i as described above. Presetting [Ca2+]e to 75 nM alone had no effect on surface β1-integrin levels when compared to normal saline (Fig. 6d, f), which coincides with the equivalent binding of β1 Fab to live cells in normal or reduced Ca2+ saline. Addition of ionomycin for 5 or 20 min, which set [Ca2+]i to 75 nM, both triggered a surface removal of β1-integrin compared to the levels measured when [Ca2+]e was set to 1.26 mM or 75 nM without ionomycin (Fig. 6d–f). Collectively, these findings demonstrate for the first time that Ca2+ signals can stimulate the rapid endocytosis of β1-integrin and alter the amount of surface receptors available for functional interactions with the ECM.

MAG-induced turning requires clathrin-mediated endocytosis

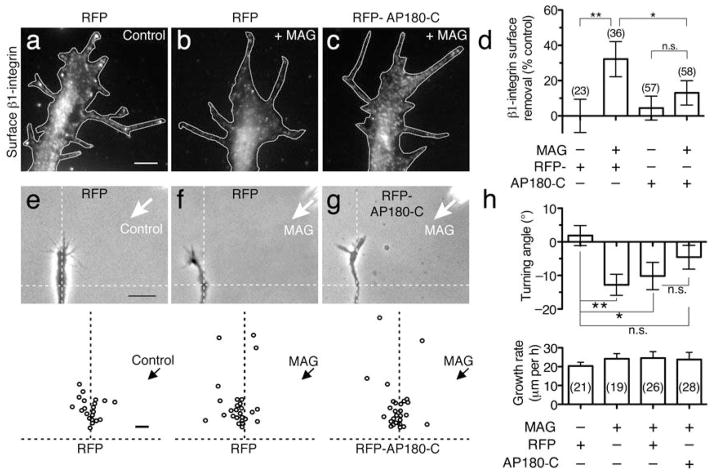

To further define the mechanism of the MAG-induced surface reduction of β1-integrin at the growth cone plasmalemma, we tested the role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME), which is prominent in the growth cone22,28 and has been shown previously to internalize integrins29. To functionally inhibit CME specifically, we expressed the dominant inhibitory clathrin-binding domain of the endocytic scaffold protein AP180 (AP180-C; see Methods), which has been demonstrated to sequester cytosolic clathrin30. A 5-min treatment with MAG stimulated a 32% (± 10 s.e.m.) surface removal of β1-integrin in spinal neuron growth cones expressing RFP alone (Fig. 7a, b), which paralleled that observed in non-expressing growth cones (Fig. 5). In contrast, expressing an RFP-AP180-C chimera significantly inhibited the MAG-induced surface removal of β1-integrin (13% ± 7; Fig. 7c, d). Expressing RFP-AP180-C had no effect on the basal level of plasmalemmal β1-integrin in untreated growth cones compared to RFP expression alone (Fig. 7d).

Figure 7. MAG-induced surface removal of β1-integrin and repulsion require clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

(a–c) Representative fluorescence images show surface β1-integrin immunolabeling on growth cones expressing RFP (a, b) or RFP-AP180-C (c) after treatment with BSA vehicle (a) or MAG (1 μg/ml) for 5 min (b, c). Scale bar, 5 μm. (d) Summary of β1-integrin surface removal in RFP- or RFP-AP180-C-expressing growth cones treated with BSA vehicle or MAG as indicated. Bars represent the mean fluorescence intensity for each group normalized to vehicle-treated RFP-expressing control growth cones. (e–g) Phase images of representative growth cones expressing RFP (e, f) or RFP-AP180-C (g) at the end of a 1-hr application of a BSA vehicle gradient (e; control) or MAG gradient (f, g; 150 μg/ml in the pipette). Dashed lines overlaid on the phase images indicate the position and orientation of the growth cone at the onset of the turning assay. Scatter plots depict the end points of individual growth cone extension relative to the starting position (origin) for all neurons examined. The original direction of growth was vertical and the arrow indicates the direction of the gradient. Scale bars, 20 μm (phase images) and 10 μm (plots). (h) Summary of turning angles and growth rates for all conditions. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. from at least 2 independent experiments (n = the number associated with each bar; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, n.s. = no significant difference, bracketed comparisons, Mann-Whitney U-test). For comparison of the mean turning angles between groups treated with a MAG gradient: RFP- vs. RFP-AP180-C-, P = 0.21; and nonexpressing vs. RFP-AP180-C-, P = 0.09.

If endocytic removal of β1-integrin is functionally relevant for growth cone turning, then inhibiting CME should abolish MAG-induced chemorepulsion. We tested this using the growth cone turning assay while expressing RFP or RFP-AP180-C. As expected, a MAG gradient induced repulsive turning of non-expressing (−12.8° ± 3.1, s.e.m.) or RFP-expressing (−10.2° ± 4.1) growth cones compared to a vehicle control gradient (1.9°± 4.3; Fig. 7e, f, h). In contrast, expression of RFP-AP180-C reduced the MAG-induced repulsive turning to −4.6° (± 3.5), which was not a significant repulsion compared to the vehicle control gradient (Fig 7g, h). The rate of axon extension was unaffected by overexpression of RFP-AP180-C or RFP alone (Fig. 7h), which agrees with published findings that clathrin-independent endocytic pathways are constitutively active in the growth cone and support basal outgrowth20,31. Taken together, these results indicate that CME mediates the stimulated removal of β1-integrin from the growth cone surface and is necessary for repulsive turning induced by MAG.

Discussion

Polarized endocytosis in the growth cone

This study reveals a functional role for endocytosis stimulated by a diffusible guidance cue and provides novel insights into the coordination of membrane trafficking and ECM adhesion during chemotactic growth cone guidance. We found that the inhibitory factor and chemorepellent MAG stimulates membrane internalization and endocytosis of β1-integrin by CME. This endocytic activity correlates with the de-enrichment of β1-integrin and the adhesion protein vinculin on the lagging edge closest to the MAG point source. A gradient of MAG is unable to repel axons when either asymmetric integrin function or CME is abolished. Finally, we show that the same low-amplitude Ca2+ signals that mediate MAG-induced growth cone repulsion are both necessary and sufficient to trigger endocytosis of β1-integrin. Altogether, these findings identify rapid endocytosis of adhesion receptors as a key cellular effector process downstream of Ca2+ signals during growth cone chemorepulsion (see Supplementary Fig. 8).

Growth cones respond to gradients of diffusible guidance cues by asymmetrically amplifying early intracellular signals including Ca2+ (refs. 15,32) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3; ref. 33). Subsequent cellular effector processes recently demonstrated to be polarized across the axis of the growth cone during chemotactic turning include actin translation34, actin assembly35, and exocytic trafficking36. Here, we show that endocytosis is also polarized during growth cone repulsion. Our live cell assay revealed that MAG stimulates asymmetric endocytosis rapidly (5 min; see Fig. 1b, f–i; Supplementary Video 6 and 7), tens of minutes before the growth cone executes turning. This rapid endocytosis correlates with the timing of β1-integrin internalization and surface redistribution induced by MAG (see Figs. 3b and 5a–b), supporting the notion that endocytic removal of β1-integrin is an early step in the initiation of chemorepulsive turning.

Regulation of ECM adhesions by integrin redistribution

Redistributing integrin receptors across the lateral axis of the growth cone provides a mechanism whereby adhesion to the ECM can polarize to initiate turning. Recently, integrin trafficking has gained attention as a mechanism by which migrating fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and invasive tumor cells can redistribute integrins to the leading edge to drive cell migration9,29. Both endocytosis and exocytosis of integrins are polarized to the leading edge of these migrating cells and have been proposed to facilitate the disassembly and assembly of ECM-adhesions, respectively, to increase adhesion turnover9,10. The idea that a balance of endocytic and exocytic trafficking of integrins is required for optimal cell migration leads to the prediction that exogenous factors favoring internalization would downregulate surface integrin receptors and promote adhesion disassembly. Our findings that MAG stimulates integrin endocytosis and triggers surface removal of β1-integrin and vinculin on the repellent side support such a model in the guidance of growth cones.

In addition to modulating the levels of integrin at the surface membrane, MAG may preferentially remove integrins from adhesion complexes in order to directly regulate traction to the ECM. Although our experiments do not test this directly, precedence exists for internalization of β1-integrin at focal adhesion sites in migrating fibroblasts10. Alternatively, endocytic removal of integrins not part of adhesive complexes could reduce the pool available for clustering and modulate the probability of nascent adhesion formation.

Integrin endocytosis downstream of intracellular Ca2+

Our observations that Ca2+ signals are both necessary and sufficient for the endocytic removal of β1-integrin from the growth cone surface (see Figs. 5e and 6) build upon previous reports that Ca2+ signals are 1) necessary for MAG-induced repulsion15,37, and 2) are alone sufficient for growth cone repulsion17,18. The Ca2+ effector proteins regulating β1-integrin internalization remain to be determined, but it is intriguing that the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin, which directly regulates the function of dynamin in nerve terminals38, has also been implicated in repulsive growth cone turning39. In addition to endocytic trafficking, calcineurin has been shown to participate in de-adhesion of the growth cone from the ECM induced by focal Ca2+ signals40. We observed a significant decrease in surface β1-integrin as early as 1 min after MAG stimulation, which is in line with the temporal dynamics of rapid Ca2+- and dynamin-mediated endocytosis observed in synaptic terminals21,38.

An understanding of the functional roles of endocytic processes in growth cone extension and guidance remain incomplete. Our findings indicate that the MAG-stimulated surface removal of β1-integrin requires a CME pathway, which was also required for chemorepulsion by a MAG gradient (see Fig. 7). Clathrin-dependent endocytosis has been implicated in growth cone collapse41 and the desensitization42 induced by collapsing factors, but an endocytic cargo with a functional role in the collapsing response remains unidentified. Collapsing factors and chemorepellents can also stimulate fluid-phase or macropinocytotic endocytosis43,44. The function of this process is unknown, but may reflect the need to engulf large amounts of surface membrane in order to drastically reduce the size of the growth cone during collapse. We found that MAG does not stimulate fluid-phase endocytosis (see Supplementary Fig. 4) but induces the formation of small endocytic vesicles (see Fig. 1; Supplementary Videos 6 and 7) and selective surface removal of β1-integrin over N-cadherin and α5-integrin (see Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 7). Our observation that low-amplitude Ca2+ signals drive internalization of β1-integrin raises the important question of how specific cargo are sequestered into endocytic pits and internalized. This is beyond the scope of our study, but may be related to an endocytic process whereby higher-amplitude Ca2+ signals control receptor density and subunit composition in postsynaptic terminals45.

Binding of MAG to NgR inhibits axon extension in rodent cerebellar granule neurons and dorsal root ganglion neurons12,14 and induces Ca2+-dependent repulsion of Xenopus spinal neuron growth cones16. A recent report indicated that MAG can also bind β1-integrin in vitro and induce FAK activation in cultured hippocampal neurons that is dependent on the expression of β1-integrin46. The latter findings suggest that β1-integrin can mediate outside-in signals downstream of MAG. In comparison, we found no polarized activation of FAK in the growth cone of Xenopus spinal neurons induced by a MAG gradient (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Our findings provide evidence for an inside-out mechanism whereby low-level Ca2+ signals, known to be downstream of NgR complex activation16, trigger endocytosis of β1-integrin. However, these observations do not exclude the possibility that additional receptors or signaling pathways could also trigger surface removal of β1-integrin.

In addition to Ca2+ signals, NgR activation can stimulate the rhoA-ROCK pathway, which is a known regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and adhesion complexes47. Furthermore, Ca2+ signals can modulate rhoA activity and these two pathways may undergo cross talk downstream of NgR activation48. Our results indicate that the MAG-induced surface removal of β1-integrin is Ca2+-dependent but does not require ROCK activity (see Fig. 5). Thus, these two pathways can act in parallel to independently govern downstream effector processes, which may work synergistically to steer growth cones more effectively. Our finding that inhibiting CME causes no preferential turning to a MAG gradient, but may not completely abolish chemorepulsive turning (see Fig. 7e–h), does not exclude the possibility of this cooperative model.

Altogether, our findings reveal that a diffusible guidance cue can direct integrin trafficking to modulate the functional distribution of integrin- and vinculin-containing adhesions in the growth cone during repulsive guidance. Our results also provide support for the idea that manipulations to increase integrin-mediated adhesion may help overcome inhibitory factors to neuro-regeneration at sites of injury. Enhancing overall adhesion might provide a permissive environment for the regrowth of injured axons that have downregulated integrins during nervous system development49,50. Furthermore, our results suggest that stimulating integrin function could have a dual role by overcoming the asymmetric de-adhesion induced by gradients of inhibitory factors that repel regenerating axons and prevent them from crossing the injury site.

Methods

Culture preparation and Xenopus embryo injection

Cultures of spinal neurons were prepared from the neural tube tissue of 1-d old (Stage 22) Xenopus laevis embryos by methods previously described15 and used for experiments 14–20 hrs after plating at 20–22°C. All experiments were conducted with the approval of the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Blastomere injection was performed as described previously26. Morpholino oligonucleotides or mRNA (1–2 μg/μl) were injected into 1–2 blastomeres at the 1–4 cell stage. A pFLAG-CMV2-AP180-C plasmid was a generous gift from Mark McNiven (Mayo Clinic). A 1.9 kb fragment encoding the C-terminus of AP180 was PCR-amplified from pFLAG-CMV2-AP180-C and subcloned into pCS2+RFP (Addgene plasmid 17112, Randall Moon) using standard procedures. In vitro transcription of capped mRNA was performed using the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). Unless indicated, we coated all coverglass with poly-D-lysine (Sigma, 0.5 mg/ml) followed by fibronectin (Sigma, 20 μg/ml). Culture medium for 1-day Xenopus laevis spinal neurons consisted of 87.5% (v/v) Leibovitz medium (GIBCO) containing 0.4% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (HyClone), and 12.5% (v/v) saline solution (in mM: 10 D-glucose, 5 Na-pyruvate, 1.26 CaCl2, and 32 HEPES, pH 7.5). Experiments were performed in modified ringers (MR) solution (in mM: 120 NaCl, 2.2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 2 Na-pyruvate, pH 7.6).

FM-dye internalization assay

To deliver a gradient of MAG (200 μg/ml in the micropipette; 5-min; R&D systems) or control BSA vehicle (0.1% in MR), we positioned a micropipette facing the growth cone at a 90° angle to the axon trajectory prior to FM dye labeling (see functional growth cone turning assay). Spinal neuron cultures were grown on uncoated coverglass. For focal dye labeling, we delivered a transient pulse of FM 5-95 (1 mM in the pipette, Invitrogen) to individual growth cones from a second micropipette positioned 100 μm in front of the leading edge of the growth cone in the direction of neurite extension. A picospritzer controlled focal dye application (2 Hz, 400 ms pulse duration, 4 pulses, 2.5 psi) at the onset of fluorescence imaging (1 Hz) with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M LSM 5LIVE confocal microscope (63X 1.2NA water immersion lens, 2x optical zoom). Original 8-bit images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). A region of interest outlining the growth cone periphery, including lamellipodia and filopodia, was created for each time point and used to determine the centroid (center of the growth cone area). Images were thresholded to minimize plasmalemmal dye fluorescence and a center of mass (COM) of endosome position was determined from a binary image34. The shift in endocytic COM was calculated by subtracting the centroid from the COM. The COM shift data from 5 consecutive timepoints (5 s) were averaged into a binned group.

β 1-integrin Fab internalization assay

Anti-β1-integrin IgG (8c8, Univ. Iowa Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) hybridoma cell supernatant was purified using standard protein G purification (Mayo Clinic Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility). We generated β1 Fab fragments by enzymatic digestion of IgG using ficin (Sigma). After dialysis and size exclusion chromatography, we pooled purified Fab fractions (assessed by SDS-PAGE/SYPRO Ruby staining; Invitrogen) and tested for the ability to bind nonpermeabilized spinal neurons using standard immunofluorescence microscopy. For internalization assays, we incubated spinal neuron cultures with β1 Fab (20 μg/ml) for 10 min in order to bind surface β1-integrin, followed by consecutive rinses with MR to remove nonbound Fab. We then treated cells with BSA vehicle, MAG (1 μg/ml), or soluble laminin (25 μg/ml; Invitrogen) during a 20-min internalization period at 20–22°C. Consecutive rinses at 8°C with MR and pH 3.0 MR removed non-internalized β1 Fab from the surface membrane after the internalization period, followed by standard fixation, permeabilization, blocking, and secondary antibody detection16. To manipulate [Ca2+]e and [Ca2+]i, we pre-incubated spinal neuron cultures for at least 30 min prior to Fab binding in a solution (in mM: 120 NaCl, 2.2 KCl, 1.26 CaCl2, 1.575 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 2 Na-pyruvate, 1.72 EGTA, pH 7.6) containing defined free [Ca2+]e, which was calculated using MaxChelator (http://maxchelator.stanford.edu). Defined [Ca2+]e conditions were maintained during the Fab binding and internalization periods. To set [Ca2+]i to [Ca2+]e, we added ionomycin (5 nM, LC Labs) or DMSO vehicle at the onset of the 20-min internalization period, after which nonbound Fab was removed using pH 3.0 Ca2+-free MR. For growth cone surface binding experiments, we incubated cells with β1 Fab for 15 min at 8°C followed by consecutive rinses at 8°C with MR and processing as described above.

Immunofluorescence, fluorescence microscopy and image analysis

Spinal neuron cultures were chemically fixed in a cytoskeleton-stabilizing buffer containing 2.5% paraformaldehyde and 0.01% glutaraldehyde for 20 min. All blocking and immunolabeling steps were performed in MR containing 5% goat serum. Alexa-dye labeled secondary antibody conjugates (Invitrogen) were used at 2 μg/ml. Unless indicated, we performed all fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope equipped with a 63X 1.4NA oil-immersion objective and a Zeiss AxioCam CCD camera with identical acquisition settings for control and experimental groups. The original 14-bit images were analyzed using ImageJ (Bio-Formats ZVI plugin). A region of interest encompassing the entire growth cone (defined as the distal 20 μm for surface immunolabeling, distal 40 μm for Fab and fluid-phase internalization assays) was used to determine the mean fluorescence intensity of thresholded images (identical for experimental and control conditions). Data were background subtracted and normalized to the appropriate controls.

Immunolabeling of growth cone surface receptors

Spinal neuron cultures were treated with MAG (1 μg/ml) or a control BSA vehicle solution for the indicated times followed by standard fixation. We immunolabeled nonpermeabilized cells using a monoclonal antibody to the extracellular domain of β1-integrin (8c8-c, 1:50) followed by secondary antibody detection. Pharmacological inhibitors LY294002 (3.33 μM; Calbiochem) and Y-27632 (25 μM; Calbiochem), as well as MnCl2 (1 mM), were added 30 min prior to MAG stimulation. To buffer intracellular Ca2+, we incubated cells in reduced Ca2+ saline (30 nM) for 30 min consisting of 50% culture medium and 50% EGTA-buffered saline (in mM: 120 NaCl, 4.9 KCl, 1.55 MgCl2, 1.25 glucose, 5 Na-pyruvate, 4 Hepes, 0.65 EGTA) and then added BAPTA-AM (Calbiochem, 1 μM) or DMSO vehicle for an additional 30 min while maintaining [Ca2+]e at 30 nM. We removed remaining extracellular BAPTA-AM by consecutive washes in reduced Ca2+ saline and then incubated cells for an additional 20 min equilibration period prior to MAG or vehicle treatment. In order to measure only receptors at the plasmalemma, we excluded inadvertently permeabilized growth cones from the analysis, as identified by tubulin immunofluorescence with polyclonal anti-β-tubulin (Abcam ab15568, 0.4 μg/ml) or monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (Abcam DM1A, 0.25 μg/ml). We used identical procedures for surface detection of N-cadherin (Santa Cruz H-63, 0.5 μg/ml) and α5-integrin (P8D4; 4 μg/ml; Douglas DeSimone, University of Virginia; see Supplementary Fig. 7). The specificity of β1-integrin antibodies was assessed by surface immunolabeling on spinal neuron cultures where β1-integrin levels were knocked down using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (standard control antisense, 5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′, 0.7 mM; β1-integrin antisense, 5′-GTGAATACTGGATAATGGGCCATCT-3′, 1.4 mM). Co-injection of Texas-Red dextran (1.5 mM, 3,000 MW lysine fixable, Invitrogen) identified morpholino-positive cells and surface immunolabeling was performed as described above using antibody 8c8 or the polyclonal β1-integrin function-blocking antibody 2999 (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Retrospective detection of growth cone adhesion proteins

To deliver a gradient of MAG (150 μg/ml in the micropipette; 5 or 15 min), we positioned a micropipette at a 90° angle relative to the direction of neurite extension (see functional growth cone turning assay). Because only one growth cone per dish was exposed to the MAG gradient, additional growth cones were used randomly as non-treated controls. Surface β1-integrin was immunolabeled as described above. Inadvertently permeabilized growth cones (β-tubulin positive), growth cones with a β1-integrin fluorescence signal less than double background levels, and growth cones with a diameter < 7 μm were excluded from analysis. We performed vinculin (Sigma V931, 1:250) and phospho-FAK (BioSource 44-624G, 1:250; see Supplementary Fig. 5) immunolabeling on permeabilized cells (0.2 % Triton-X-100) and used Alexa555 secondary antibody conjugates. Total protein labeling with an amine-reactive fluorescein (5-DTAF, 400 nM, Invitrogen) accounted for differences in growth cone thickness35. To co-label β1-integrin and phospho-FAK, we performed surface β1-integrin immunolabeling on fixed cells followed by permeabilization, primary, and secondary detection of phospho-FAK. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope equipped for total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRF) with an argon laser tuned to 488 and 514 nm, a 100× α Plan-Fluar 1.45NA objective, bandpass emission filters (500–550, 550–600), and a Hamamatsu EM-CCD camera. To overcome artifacts from glass-induced streaking in TIRF microscopy, we captured images at 3 unique x-y positions and the final data for individual growth cones represent an average of the three positions. Quantitative measurements of asymmetry were performed on the original 14-bit images using NIH ImageJ software. A square region of interest 1/5 the diameter of the growth cone was placed on the near (N) and far (F) sides of the growth cone relative to the MAG pipette and the fluorescence intensity of each was measured from a thresholded image. The following equation was used to determine percent asymmetry for β1-integrin: % difference = 100 * [(N–F)/((N+F)/2)]. The following equation was used to normalize vinculin or phospho-FAK to total protein: % difference = 100 * [((Nvinc/NDTAF) – (Fvinc/FDTAF))/((Nvinc/NDTAF) + (Fvinc/FDTAF))/2]. For demonstrative purposes, the mid-tone levels of representative vinculin TIRF micrographs (Fig. 3c,d; middle panels) were reduced to bring out brighter puncta in the growth cone periphery. Example ratiometric images of vinculin:DTAF were created in ImageJ using background subtraction and the RatioPlus plugin.

Functional growth cone turning assay

Microscopic gradients were produced as previously described32. We positioned a micropipette containing MR + BSA vehicle (0.1%), MAG (150 μg/ml), control rabbit IgG (MC64; 0.4 mg/ml), or β1-integrin function-blocking antibody 2999 (0.4 mg/ml) 80 μm away from the center of the growth cone and at an angle of 45° with respect to the initial direction of neurite extension. A standard pressure pulse was controlled by a picospritzer and we determined the actual concentration at the growth cone to be 800-fold lower than the concentration in the micropipette. A CCD camera recorded phase-contrast images (20× objective). The turning angle was determined as previously described32. Only growth cones that extended > 5 μm over the 1-hr period were used for analysis. To directly manipulate integrin function, Mn2+ (1 mM) and the β1-integrin function-blocking antibody 2999 (5 μg/ml; K. Yamada, National Institutes of Health) were added > 30 min prior to the start of the growth cone turning assay. This antibody specifically recognizes and blocks the function of Xenopus β1-integrin (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fluid-phase endocytosis assays

For live-cell fluid-phase endocytosis assays, we focally applied TRITC-dextran (1 mM in the micropipette; 10,000 MW, neutral, Invitrogen) for 10–15 s to individual growth cones using a micropipette positioned 80 μm in front of the leading edge of the growth cone in the direction of neurite extension. A second micropipette containing MR, positioned 80 μm perpendicular to the growth cone trajectory, was immediately used to wash away non-internalized fluorescent dextran. A picospritzer controlled both micropipettes. Co-internalization of Alexa-488 dextran (0.5 mM in the pipette, 10,000 MW, Invitrogen) and FM 5-95 (100 μM in the pipette) was performed by simultaneous local application from the same micropipette and similar use of a second wash micropipette. Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM5LIVE confocal microscope with a 63X water-immersion objective. For quantitative measurements of fluid-phase endocytosis, we incubated cells with fluorescent dextran (150 μM; FITC or TRITC 10,000 MW lysine fixable; Invitrogen) for 10 min with the indicated concentration of MAG or BSA vehicle control and removed non-internalized dextran by consecutive washes at 10°C. For co-internalization of β1 Fab and fluorescent dextran, we first bound β1 Fab to the surface of live spinal neurons as described above. After rinsing away non-bound Fab, we added Alexa-647 dextran (10,000 MW, 125 μM, Invitrogen) and MAG (1 μg/ml) together during the 20-min internalization period.

Neurite length measurements

For measurements of neurite length in response to increasing concentrations of Mn2+, we cultured spinal neurons on a fibronectin substrate in a media consisting of 50% CMC and 50% MR with the addition of MnCl2 and fixed cells 8 h after plating. For length measurements in neurons containing morpholino oligonucleotides, we fixed spinal neuron cultures grown on fibronectin 14 h after plating. We measured axon length on phase-contrast or fluorescence images (10×) using the ImageJ plugin NeuronJ (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Only the longest neurite or branch of an individual neuron was measured and only axons > 50 μm in length were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism software (v5). Data with a normal distribution (D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test) were assessed using a two-tailed t-test comparing each experimental condition to the appropriate control. All other data were tested for statistical significance using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test, comparing experimental groups to the appropriate control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenneth Yamada, Douglas DeSimone, and Mark McNiven for generous gifts of antibodies to β1-integrin, α5-integrin, and dynamin (MC64 control rabbit IgG), respectively. We also thank Ramakrishnan Muthu for assistance with β1 Fab purification; Timothy Gomez, Bruce Horazdovsky, Charles Howe, Mark McNiven, Richard Pagano, and members of the Henley lab for critical comments; Anthony Windebank for sharing lab space at the beginning of these studies, and Jim Tarara, Steven Henle, Ellen Liang, Zheyan Chen, Bing-Yan Lin, Velizar Petrov, Daniel Triner and Jarred Nesbitt for technical assistance. This work was supported by a John M. Nasseff, Sr. Career Development Award in Neurologic Surgery Research from the Mayo Clinic (J.R.H.) and career development funds from the Craig Neilsen Foundation (J.R.H.). A Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Predoctoral Fellowship award supported J.H.H.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.H.H. and J.R.H. conceived the project and designed experiments; J.H.H., M.A.-R. and J.R.H. performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper; J.R.H. supervised the project.

The supplementary data include eight Supplementary Figures and seven Supplementary Videos.

References

- 1.Dickson BJ. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Science. 2002;298:1959–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang S, et al. Soluble myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) found in vivo inhibits axonal regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:333–346. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poinat P, et al. A conserved interaction between beta1 integrin/PAT-3 and Nck-interacting kinase/MIG-15 that mediates commissural axon navigation in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2002;12:622–631. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00764-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robles E, Gomez TM. Focal adhesion kinase signaling at sites of integrin-mediated adhesion controls axon pathfinding. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/nn1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens A, Jacobs JR. Integrins regulate responsiveness to slit repellent signals. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4448–4455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04448.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serini G, et al. Class 3 semaphorins control vascular morphogenesis by inhibiting integrin function. Nature. 2003;424:391–397. doi: 10.1038/nature01784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechara A, et al. FAK-MAPK-dependent adhesion disassembly downstream of L1 contributes to semaphorin3A-induced collapse. EMBO J. 2008;27:1549–1562. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woo S, Gomez TM. Rac1 and RhoA promote neurite outgrowth through formation and stabilization of growth cone point contacts. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1418–1428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4209-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caswell P, Norman J. Endocytic transport of integrins during cell migration and invasion. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezratty EJ, Bertaux C, Marcantonio EE, Gundersen GG. Clathrin mediates integrin endocytosis for focal adhesion disassembly in migrating cells. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;187:733–747. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atwal JK, et al. PirB is a functional receptor for myelin inhibitors of axonal regeneration. Science. 2008;322:967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1161151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domeniconi M, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein interacts with the Nogo66 receptor to inhibit neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 2002;35:283–290. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filbin MT. PirB, a second receptor for the myelin inhibitors of axonal regeneration Nogo66, MAG, and OMgp: implications for regeneration in vivo. Neuron. 2008;60:740–742. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu BP, Fournier A, GrandPré T, Strittmatter SM. Myelin-associated glycoprotein as a functional ligand for the Nogo-66 receptor. Science. 2002;297:1190–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1073031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henley JR, Huang K-h, Wang D, Poo M-m. Calcium mediates bidirectional growth cone turning induced by myelin-associated glycoprotein. Neuron. 2004;44:909–916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong ST, et al. A p75(NTR) and Nogo receptor complex mediates repulsive signaling by myelin-associated glycoprotein. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1302–1308. doi: 10.1038/nn975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong K, Nishiyama M, Henley J, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M. Calcium signalling in the guidance of nerve growth by netrin-1. Nature. 2000;403:93–98. doi: 10.1038/47507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng JQ. Turning of nerve growth cones induced by localized increases in intracellular calcium ions. Nature. 2000;403:89–93. doi: 10.1038/47501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng JQ, Poo MM. Calcium signaling in neuronal motility. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:375–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diefenbach TJ, Guthrie PB, Stier H, Billups B, Kater SB. Membrane recycling in the neuronal growth cone revealed by FM1-43 labeling. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9436–9444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09436.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu XS, et al. Ca(2+) and calmodulin initiate all forms of endocytosis during depolarization at a nerve terminal. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nn.2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng TP, Reese TS. Polarized compartmentalization of organelles in growth cones from developing optic tectum. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101:1473–1480. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Condic ML, Letourneau PC. Ligand-induced changes in integrin expression regulate neuronal adhesion and neurite outgrowth. Nature. 1997;389:852–856. doi: 10.1038/39878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sydor AM, Su AL, Wang FS, Xu A, Jay DG. Talin and vinculin play distinct roles in filopodial motility in the neuronal growth cone. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:1197–1207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gailit J, Ruoslahti E. Regulation of the fibronectin receptor affinity by divalent cations. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12927–12932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ming G, et al. Phospholipase C-gamma and phosphoinositide 3-kinase mediate cytoplasmic signaling in nerve growth cone guidance. Neuron. 1999;23:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niederöst B, Oertle T, Fritsche J, McKinney RA, Bandtlow CE. Nogo-A and myelin-associated glycoprotein mediate neurite growth inhibition by antagonistic regulation of RhoA and Rac1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10368–10376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10368.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshihara HKHF. The Role of Endocytic L1 Trafficking in Polarized Adhesion and Migration of Nerve Growth Cones. J Neurosci. 2001 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09194.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura T, Kaibuchi K. Numb controls integrin endocytosis for directional cell migration with aPKC and PAR-3. Dev Cell. 2007;13:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, et al. Expression of auxilin or AP180 inhibits endocytosis by mislocalizing clathrin: evidence for formation of nascent pits containing AP1 or AP2 but not clathrin. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114:353–365. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonanomi D, et al. Identification of a developmentally regulated pathway of membrane retrieval in neuronal growth cones. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121:3757–3769. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng JQ, Felder M, Connor JA, Poo MM. Turning of nerve growth cones induced by neurotransmitters. Nature. 1994;368:140–144. doi: 10.1038/368140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akiyama H, Matsu-ura T, Mikoshiba K, Kamiguchi H. Control of neuronal growth cone navigation by asymmetric inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signals. Science Signaling. 2009;2:ra34. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leung KM, et al. Asymmetrical beta-actin mRNA translation in growth cones mediates attractive turning to netrin-1. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1247–1256. doi: 10.1038/nn1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen Z, et al. BMP gradients steer nerve growth cones by a balancing act of LIM kinase and Slingshot phosphatase on ADF/cofilin. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:107–119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tojima T, et al. Attractive axon guidance involves asymmetric membrane transport and exocytosis in the growth cone. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:58–66. doi: 10.1038/nn1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song H, et al. Conversion of neuronal growth cone responses from repulsion to attraction by cyclic nucleotides. Science. 1998;281:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu JP, Sim AT, Robinson PJ. Calcineurin inhibition of dynamin I GTPase activity coupled to nerve terminal depolarization. Science. 1994;265:970–973. doi: 10.1126/science.8052858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen Z, Guirland C, Ming GL, Zheng JQ. A CaMKII/calcineurin switch controls the direction of Ca(2+)-dependent growth cone guidance. Neuron. 2004;43:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conklin MW, Lin MS, Spitzer NC. Local calcium transients contribute to disappearance of pFAK, focal complex removal and deadhesion of neuronal growth cones and fibroblasts. Dev Biol. 2005;287:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piper M, et al. Signaling mechanisms underlying Slit2-induced collapse of Xenopus retinal growth cones. Neuron. 2006;49:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piper M, Salih S, Weinl C, Holt CE, Harris WA. Endocytosis-dependent desensitization and protein synthesis-dependent resensitization in retinal growth cone adaptation. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nn1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fournier AE, et al. Semaphorin3A enhances endocytosis at sites of receptor-F-actin colocalization during growth cone collapse. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:411–422. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolpak AL, et al. Negative guidance factor-induced macropinocytosis in the growth cone plays a critical role in repulsive axon turning. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10488–10498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2355-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanley JG, Henley JM. PICK1 is a calcium-sensor for NMDA-induced AMPA receptor trafficking. EMBO J. 2005;24:3266–3278. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goh EL, et al. beta1-integrin mediates myelin-associated glycoprotein signaling in neuronal growth cones. Molecular Brain. 2008;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamashita T, Higuchi H, Tohyama M. The p75 receptor transduces the signal from myelin-associated glycoprotein to Rho. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:565–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin M, et al. Ca2+-dependent regulation of rho GTPases triggers turning of nerve growth cones. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2338–2347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4889-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tysseling-Mattiace VM, et al. Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit glial scar formation and promote axon elongation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3814–3823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Condic ML. Adult neuronal regeneration induced by transgenic integrin expression. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4782–4788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04782.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.