Abstract

Background

We investigated the role of psychosocial and proximal contextual factors on nicotine dependence in adolescence.

Methods

Data on a multiethnic cohort of 6th to 10th graders from the Chicago public schools were obtained from four household interviews conducted with adolescents over two years and one interview with mothers. Structural equation models were estimated on 660 youths who had smoked cigarettes by the first interview.

Results

Pleasant initial sensitivity to tobacco use, parental nicotine dependence (ND), adolescent ND and extensiveness of smoking at the initial interview had the strongest total effects on adolescent ND two years later. Perceived peer smoking and adolescent conduct problems were of lesser importance. Parental ND directly impacted adolescent ND two years later and had indirect effects through pleasant initial sensitivity and initial extensiveness of smoking. Parental depression affected initial adolescent dependence and depression but adolescent depression had no effect on ND. The model had greater explanatory power for males than females due partly to the stronger effect of conduct problems on dependence for males than females.

Conclusions

The findings underscore the importance of the initial drug experience and familial factors on adolescent nicotine dependence and highlight the factors to be the focus of efforts targeted toward preventing ND among adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescent nicotine dependence, pleasant initial sensitivity, parental nicotine dependence, conduct problems, longitudinal

Much more is known about the etiology of smoking than nicotine dependence (ND) in adolescence. Several studies have compared the characteristics of dependent and non-dependent adolescent smokers (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2007; DiFranza et al., 2007a; Hu, Davies, & Kandel, 2006; Kandel, Hu, Griesler, & Schaffran, 2007; Karp, O'Loughlin, Hanley, Tyndale, & Paradis, 2006). To our knowledge, no study has tested a causal model of adolescent ND to specify the role of important risk and protective factors. We apply a developmental socialization framework to document the impact of individual psychosocial characteristics and proximal contextual variables on ND in adolescence.

The Developmental Socialization Framework

For lack of a theoretical framework conceptualizing the factors and developmental processes for adolescent ND, we relied on general models of smoking, substance abuse, and deviant behavior to guide our investigation, and in particular on developmental socialization, which incorporates elements of social control, social learning and differential association theories (Kandel, l980). The fundamental assumption is that adolescent behaviors result from individual attributes, including biological and genetic factors, within the individual's major social contexts, ranging from the proximal contexts of family and peers, to school, community and the larger society. Only family and peers are considered in this study, in addition to individual factors, in an adolescent cohort followed for two years.

Familial influences derive from parental role models, quality of parental child-rearing, parental personality, and family structure. Parental smoking and ND directly increase child onset of smoking, daily smoking and ND (Chassin, Presson, Todd, Rose, & Sherman, 1998; Hill, Hawkins, Catalano, Abbott, & Guo, 2005; Kandel et al., 2007; Kandel & Wu, 1995). Inadequate child-rearing practices (low monitoring, poor bounding), and lack of family rules, are associated with onset, daily and persistent smoking, and ND. Living in a single parent family is associated with onset but not daily or persistent smoking (DiFranza et al., 2007a; Griesler, Kandel & Davies, 2002; Hill et al., 2005; Kandel, Kiros, Schaffran & Hu, 2004; O'Loughlin, Karp, Koulis, Paradis & DiFranza, 2009), although Orlando, Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein (2004) reported that non-intact family was associated with heavy smoking. Low monitoring indirectly affects child smoking and ND by fostering aggressiveness and association with drug using or delinquent peers (Chassin et al., 1998; Kandel & Wu, 1995; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Parental depression is associated with adolescent depression, conduct problems, and smoking (Griesler et al., 2002; Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, Taylor, Pawlby, & Caspi, 2005; Wickramaratne & Weissman, 1998). The direct and indirect effects of parental ND, depression and monitoring on adolescent ND remain to be specified.

Deviant peers' impact on the etiology and maintenance of drug use has been extensively documented. Peer smoking predicts initiation, persistence of smoking and dependence (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2007; Bauman & Ennett, 1994; Griesler et al., 2002; Kandel et al., 2004) and is a mediator of conduct disorder on substance use (Mason, Hitchings, & Spoth, 2008) and smoking specifically (Brook, Whiteman, Czeisler, Shapiro, & Cohen, 1997).

Adolescent behavioral and personality characteristics, e.g., delinquency, conduct disorder, depression, and other psychiatric disorders, are associated with initiation, continued use of cigarettes and other substances, and with ND (Choi, Pierce, Gilpin, Farkas, & Berry, 1997; Lynskey & Fergusson, 1995). However, the direction of causality between psychiatric disorders, smoking and ND is unresolved. Psychiatric disorders, especially conduct disorder, precede smoking initiation, predict continued smoking and dependence, and may be further exacerbated by smoking. In turn, heavy smoking and ND predict psychiatric disorders, particularly mood and anxiety disorders (Boden, Fergusson & Horwood, 2010; Breslau, Novak, & Kessler, 2004; Griesler, Hu, Schaffran, & Kandel, 2008; Hu et al., 2006; Isensee, Wittchen, Stein, Höfler, & Lieb, 2003; Karp et al., 2006; Patton et al., 1998; Pederson & von Soest, 2009).

In addition, individual genetic differences in initial sensitivity to nicotine may constitute a critical element in adolescent susceptibility to ND (Eissenberg & Balster, 2000; Pomerleau, Pomerleau, & Namenek, 1998). The most sensitive youths, who initially experience more positive effects, are more likely to proceed rapidly to regular smoking (Sartor et al., 2010) and to become dependent (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2007; DiFranza et al, 2007a; Kandel et al., 2007). Tolerance and dependence may result not from extent of smoking but from pre-existing biobehavioral differences in sensitivity to nicotine (Shiffman, 1991).

Influences of parents, peers, and child psychopathology vary by gender. Parental monitoring reduces onset of daily smoking more in males than females (Hill et al., 2005), whereas maternal smoking (Kandel & Wu, 1995), peer influences (Hu, Flay, Hedeker, Siddiqui & Day, 1995), depression and anxiety (Kandel et al., 2007; Patton et al., 1998), and behavioral disorders (Costello, Erkanli, Federman & Angold, 1999) are associated with persistent smoking, daily smoking and ND more in females than males.

To specify the important factors for ND in adolescence, we estimated a structural equation model (SEM) among adolescents (14.7 years old on average), who were followed for two years in a period of risk for experiencing ND symptoms following smoking onset. The 24-month follow-up is sufficient to capture onset of ND symptoms. In the cohort, 25% of youths experienced their first DSM-IV ND criterion within 5 months of starting to use tobacco (first puff of cigarette), 51% did so within 23 months; 25% met full ND (three criteria) within 23 months (Kandel et al., 2007). Latency estimates reported by other investigations vary depending upon definitions of smoking onset and ND. For onset of any ND symptom, estimates range from 1 month (from first inhalation) to 27 months (from first puff); for full ND, from 4.6 to 40.6 months (DiFranza et al., 2002; 2007b; Doubeni, Reed & DiFranza, 2010; Gervais, O'Loughlin, Meshefedjian, Bancej, & Tremblay, 2006).

The causal model is described under Methods.

Method

Participants

Subjects are from The Transition to Nicotine Dependence study, a five-wave longitudinal multi-ethnic cohort of 1,039 6th-10th graders selected from the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and one of their parents. A two-stage design was implemented to select the sample for follow-up. In Phase I (spring 2003), 15,763 students in grades 6-10 were sampled from 43 CPS schools (83.1% completion rate); 1,236 youths were selected: 1,106 tobacco users who reported starting to use tobacco within 12 months and 130 non-tobacco users susceptible of starting to smoke (Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, & Farkas, 1996), divided among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic African Americans, and Hispanics. In Phase II, on average 9 weeks after each school survey, 1,039 youths (84.1% of target; 272 white, 343 African American, 424 Hispanic) and one parent (86.8% mothers) participated in the two-year follow-up involving three annual 90-minute computerized household interviews with youths and parents at Waves 1, 3, 5 (W1, W3, W5) and two 20-minute bi-annual interviews with youths at Waves 2 and 4 (W2, W4). Adolescents reported at every wave about their smoking and DSM-IV ND symptoms, annually about DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. Mothers reported annually on their DSM-IV ND symptoms, DSM-IV depression, and their child's psychiatric disorders. Completion rates at W2-W5 were 96.0% of the W1 sample. The National Opinion Research Center (NORC) conducted the fieldwork.

There were inconsistencies between school and household smoking reports. Of the 832 youths, who in school had reported smoking lifetime, 643 did so at W1. Compared with consistent reporters, underreporters (N=189) were younger, more likely to be African American, lighter smokers, had more non-smoking parents and peers, and reported fewer deviant activities (Griesler et al., 2008). There were 71 new smokers. The analytical sample includes youths who reported lifetime smoking at W1 and were reinterviewed at W3, W4 and W5 (N=660). Smoking status was defined per household reports because data on smoking and ND were unavailable for those who reported never smoking at W1.

Human Subjects Procedures

We obtained parental consent for the school survey and interviews; adolescent assent for both. Procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, and NORC.

Definitions of Variables

Model variables were from W1, W3, W4 and W5 for youths, W1 for parents. The W2 youth smoking measures were omitted because their assessment overlapped with the first six months of the annual assessments of W3 depression and conduct problems and were correlates, not predictors, of these variables.

Adolescent variables

ND criteria W1, W5

Measured per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) by an instrument developed for adolescents (Dierker et al., 2007). The 11-item scale measured symptoms defining the seven DSM-IV dependence criteria experienced the last 12 months at W1 and since the W4 interview at W5 (Mean interval=6.1 months): tolerance, withdrawal, impaired control, unsuccessful attempts to quit, great deal of time spent using, neglect important activities, use despite physical or psychological problems (α=.85). Full nicotine dependence was defined as 3 or more criteria.

Pleasant initial sensitivity to first tobacco W1

(modified Pomerleau et al., 1998). Average score of four items measuring pleasant experiences (coded 1=none to 4=intense): pleasant sensations, relaxation, pleasurable dizziness, and pleasurable rush/buzz (α=.71).

Perceived peer smoking W1, W4

0=none, 1=one, 2=some, 3=most, 4=all friends smoked.

Number of cigarettes smoked last 12 months W1, or since W3 at W4

For each interval, logarithm of the product of number of (a) days smoked and (b) cigarettes smoked per day in the most recent month smoked. Number of days: 0=0; 1-2=1.5; 3-5=4.0; 6-9=7.5; 10-39=25; 40-99=70; 100-199=150; 200-299=250; 300 or more=333. Daily quantity: one or two puffs=0.5; 1 cigarette=1; 2-5=3; 6-15=10; 16-25=20; 26-35=30; more than 35=40.

Depression W1, W3

Latent factors constructed from two indicators at each wave: (1) depressive symptoms scale past 30 days[D1] (Gadow et al., 2002), average of 12 4-point items (range 0-3, α=.89); (2) number of major depressive disorder criteria last 12 months[D2], based on the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children from youths and parents (DISC-IV-Y and –P)(range 0-8; α=.87)(Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, & Comer, 2000).

Conduct problems W1, W3

Latent factors constructed from two indicators at each wave: (1) delinquent activities[C1], sum of 15 delinquent behaviors collapsed at 11+ (range 0-11, α=.80) (Resnick et al., 1997)(see online materials, Table A); (2) number of conduct disorder criteria last 12 months at W1[C2], DISC predictive scale (DPS)(Lucas et al., 2001)(range 0-8, α=.62), and an indicator based on parents and youths (DISC-IV-Y and –P) at W3[C3] (range 0-9, α=.63).

Age in years W1

Age 11 was grouped with 12; age 17 with 16.

Race/Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic.

Gender

Female=0; male=1.

Parental variables

Lifetime depression W1

DSM-IV major depressive disorder per the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 2.1)(Andrews & Peters, 1998).

Lifetime ND W1

Measured as for youths (α=.80) and defined as full dependence: ≥3 criteria.

Monitoring W1

Extent and frequency of monitoring and supervising the youth's whereabouts (Kandel & Wu, 1995). Averaged six 5-point items (1=never to 5=always)(α=.49).

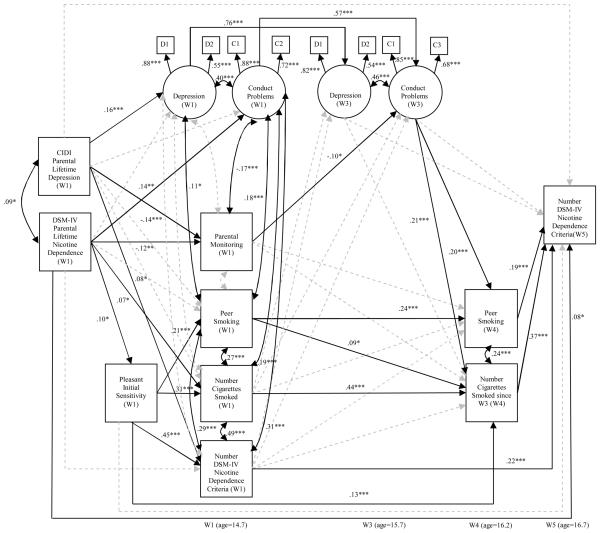

Model

The outcome variable was the count of ND criteria experienced by adolescents at W5, controlling for W1 ND baseline level (Figure 1). The model tested the following assumptions. Parental ND and depression (W1), adolescent pleasant initial sensitivity (W1), ND (W1), depression and conduct problems (W3), and extensiveness of smoking and peer smoking (W4) affect directly adolescent W5 dependence. Parental dependence and depression affect directly parental monitoring, adolescent depression, conduct problems, extensiveness of smoking, ND, and association with smoking peers at W1. Adolescent pleasant initial sensitivity to tobacco (W1) mediates the effects of parental dependence on adolescent extensiveness of smoking dependence over time and directly affects peer smoking at W1. Extensiveness of smoking and peer smoking at W1 are mediated by these same variables at W4 and influence each other over time. The paths from parental dependence and monitoring to adolescent dependence at W5 also mediate child psychopathology at W3 (depression, conduct problems) and extensiveness of smoking and peer smoking at W4. Child psychopathology impacts ND directly as well as indirectly through peer smoking and extensiveness of smoking. Sociodemographic controls included adolescent age, gender and race/ethnicity. Two additional family variables (family structure, parental involvement) were considered but omitted because they had no significant associations with youth ND and their inclusion would have unnecessarily increased the complexity of the model.

Figure 1.

Developmental process of DSM-IV nicotine dependence among W1 lifetime smokers (N=660).

*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001. Dotted paths not significant. CFI=0.96, RMSEA=.05

Statistical Analysis

Structural equation models (SEM) identified the relationships among variables and were estimated in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2007). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) estimated simultaneously a single measurement model for depression and conduct problems at W1 and W3, each latent construct reflecting two observed variables (Figure 1). For each latent variable, the factor loading of one indicator was constrained at 1 while the other was freed. All error and disturbance terms variances were freed. An SEM was first estimated in the total sample. Model fit was evaluated by two indices: comparative fit index (CFI) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI compares model fit against the null model; values of .95 or larger reflect good fit. RMSEA displays the average deviation between observed and predicted correlations among indicators and should be smaller than .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), although .08 is acceptable (Bollen & Long, 1993). Models were also estimated separately by gender. Using the multigroup comparison procedure, we tested that the measurement model was not different between males and females and the causal model applied equally well to each group. Factor loadings, intercepts and thresholds of the factor indicators were set to be equal across groups. That model was compared to the full model where coefficients were freed. The likelihood ratio chi-square statistic tested significant differences between the two nested models. Modification indices identified paths that were different and indicated the sources of model misspecification (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993). Coefficients with the highest values on the modification indices were freed until the difference in the likelihood ratio chi-squares between the full and reduced models was no longer statistically significant.

Total, direct and indirect effects were calculated for the total sample and for each gender. Indirect effects were decomposed to identify important mediators and included overlapping effects. To handle missingness of data, the missing at random estimation procedure was implemented.

Results

Sample Description

Of the 660 lifetime smokers, 54.1% were female; 26.8% non-Hispanic whites, 31.3% non-Hispanic African Americans, 41.9% Hispanics. At W1, adolescents were 14.7(SD=1.3) years old on average; 59.8% had smoked in the last 12 months, on average 25.7(SD=65.2) days, and 1.5(SD=2.9) cigarettes per day, for a total of 136(SD=533) cigarettes. Of W1 smokers, 55.4% experienced no DSM-IV ND criteria at W1, 17.2% experienced one criterion, 10.9% experienced two criteria, 8.0% three criteria, 8.5% four to six criteria. No youth experienced seven criteria. Thus, 16.5% met criteria for full dependence in the last 12 months. At W5, 44.3% had smoked within the six months since W4, and more heavily than two years earlier. They smoked on average 55.0(SD=86.5) days and 4.1(SD=5.4) cigarettes per day, for a total of 469(SD=1,106) cigarettes; 38.5% did not experience any ND criterion in the prior six months, 23.2% experienced one criterion, 16.1% two criteria, 6.9% three criteria, 15.3% four to six criteria (22.2% full dependence). Distributions of variables in the total sample and by gender are available online (Table B).

Structural Equation Modeling

Correlations among variables appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations Between Covariates (N=660)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4a | 4b | 5a | 5b | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10a | 10b | 11a | 11b | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Parental depression-W1(binary) | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 2-Parental dependence-W1(binary) | .09 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3-Pleasant initial sensitivity-W1 | .03 | .05 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4a-Depressive symptoms-W1 | .11 | .04 | .14 | |||||||||||||||

| 4b-Depressive disorder criteria-W1 | .16 | .04 | .12 | .43 | ||||||||||||||

| 5a-Delinquency-W1 | .02 | .10 | .20 | .28 | .11 | |||||||||||||

| 5b-Conduct disorder criteria-W1 | .04 | .08 | .15 | .28 | .12 | .63 | ||||||||||||

| 6-Parental monitoring-W1 | -.16 | -.14 | −.06 | −.03 | −.14 | −.19 | −.13 | |||||||||||

| 7-Perceived peer smoking-W1 | −.04 | .03 | .22 | .10 | .02 | .14 | .10 | .02 | ||||||||||

| 8-Cigarettes smoked-W1(log) | .07 | .10 | .34 | .00 | .06 | .15 | .15 | −.04 | .33 | |||||||||

| 9-Dependence criteria-W1 | .09 | .12 | .45 | .07 | .05 | .29 | .17 | −.07 | .30 | .65 | ||||||||

| 10a-Depressive symptoms-W3 | .09 | .02 | .04 | .59 | .31 | .14 | .14 | −.03 | .11 | .01 | .02 | |||||||

| 10b-Depressive disorder criteria-W3 | .05 | .01 | .06 | .37 | .44 | .11 | .07 | −.05 | .04 | .01 | .02 | .44 | ||||||

| 11a-Delinquency-W3 | .02 | .10 | .11 | .15 | .05 | .47 | .36 | −.15 | .11 | .12 | .14 | .29 | .08 | |||||

| 11b-Conduct disorder criteria-W3 | −.02 | .07 | .07 | .16 | .12 | .35 | .32 | −.20 | .06 | .05 | .04 | .22 | .15 | .56 | ||||

| 12-Perceived peer smoking-W4 | .00 | .04 | .19 | .05 | .02 | .17 | .12 | −.05 | .33 | .22 | .18 | .03 | −.05 | .24 | .15 | |||

| 13-Cigarettes smoked-W4(log) | .01 | .14 | .29 | .02 | .09 | .19 | .14 | −.07 | .27 | .55 | .36 | −.01 | .00 | .23 | .18 | .37 | ||

| 14-Dependence criteria-W5 | .02 | .13 | .25 | .04 | .06 | .13 | .06 | −.09 | .20 | .36 | .30 | .05 | .02 | .16 | .10 | .28 | .59 | |

| 15-Age-W1 | .02 | −.05 | .12 | .06 | .12 | −.03 | −.07 | −.03 | .22 | .16 | .12 | .01 | .04 | −.11 | −.07 | .14 | .10 | .06 |

| 16-Gender | −.04 | .05 | .04 | −.26 | −.13 | .07 | .09 | −.10 | −.03 | .03 | .03 | −.30 | −.13 | .06 | .03 | .10 | .07 | .01 |

Bolded coefficients significant at p<.05.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The measurement model for the two latent variables, depression and conduct problems, fit the data for the total sample (CFI=.95, RMSEA=.08) and by gender (CFI=.96, RMSEA=.07). There was no significant measurement variance across gender.

Causal model: total sample

The significant estimated standardized coefficients for the SEM are indicated in Figure 1. The standardized loadings to manifest indicators of the latent factors and correlations between the indicators for each latent factor ranged from .43 to .88 (p<.001). Total effects, direct and indirect effects, and important mediators of model variables appear in Table 2.

Table 2.

Decomposition of Total Effects on W5 Nicotine Dependence (N=660)

| Total effect |

Direct effect |

Total indirect effect |

Indirect/ Total |

Decomposition of indirect effect througha |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β(s.e.) | β(s.e.) | β(s.e.) | β | |||

| Parental depression(W1) | .032(.047) | .003(.042) | .029(.018) | 91% | Depression(W1) | .003 |

| Conduct problems(W1) | .001 | |||||

| Parental monitoring(W1) | .003 | |||||

| Peer smoking(W1) | −.004 | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W1) | .009 | |||||

| Dependence criteria(W1) | .007 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Parental dependence(W1) | .151(.045)** | .082(.039)* | .069(.021)** | 46% | Pleasant initial sensitivity | .027* |

| Depression(W1) | .002 | |||||

| Conduct problems(W1) | .011 | |||||

| Parental monitoring(W1) | .003 | |||||

| Peer smoking(W1) | .002 | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W1) | .018* | |||||

| Dependence criteria(W1) | .025 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Pleasant initial sensitivity | .265(.047)*** | .045(.049) | .220(.029)*** | 83% | Peer smoking(W1) | .016** |

| Cigarettes smoked(W1) | .054*** | |||||

| Dependence criteria(W1) | .103*** | |||||

| Depression(W3) | .000 | |||||

| Conduct problems(W3) | .004 | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | .102*** | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Depression(W1) | .022(.045) | .022(.045) | 100% | Depression(W3) | .022 | |

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | −.008 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Conduct problems(W1) | .075(.035)* | .075(.035)* | 100% | Conduct problems(W3) | .075* | |

| Peer smoking(W4) | .021** | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | .044*** | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Parental monitoring(W1) | −.021(.018) | −.021(.018) | 100% | Conduct problems(W3) | −.013 | |

| Peer smoking(W4) | −.004 | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | −.015 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Peer smoking(W1) | .077(.022)*** | .077(.022)*** | 100% | Peer smoking(W4) | .045** | |

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | .031* | |||||

|

| ||||||

| No. Cigarettes smoked(W1) | .173(.028)*** | .173(.028)*** | 100% | Depression(W3) | −.001 | |

| Conduct problems(W3) | .004 | |||||

| Peer smoking(W4) | .012 | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | .164*** | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Dependence criteria(W1) | .229(.063)*** | .215(.057)*** | .014(.025) | 6% | Depression(W3) | .001 |

| Conduct problems(W3) | .005 | |||||

| Peer smoking(W4) | .018 | |||||

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | −.005 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Depression(W3) | .029(.059) | .040(.056) | −.011(.020) | −38% | Cigarettes smoked(W4) | −.011 |

|

| ||||||

| Conduct problems(W3) | .133(.059)* | .018(.056) | .115(.022)*** | 86% | Peer smoking(W4) | .037** |

| Cigarettes smoked(W4) | .078*** | |||||

Includes all overlapping effects.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

The model provided a good fit to the data (CFI=.96; RMSEA=.05) and explained 41% of the total variance in ND at W5. Of the W1 factors, those with the highest total effects on dependence at W5 were in order: pleasant initial sensitivity to tobacco, W1 adolescent ND and extensiveness of smoking, parental dependence, W1 perceived peer smoking and adolescent conduct problems. The effect of initial sensitivity was mostly indirect (83%) and mediated by W1 adolescent ND (47%) and extensiveness of smoking at W1 and W4 (48%). Over half (54%) the total effect of parental dependence was direct; it affected adolescent dependence at W5 but not W1. Of the indirect paths of parental ND to adolescent W5 dependence, the most significant were through adolescent pleasant initial sensitivity (40%) and W1 extensiveness of smoking (26%). Parental dependence had additional direct (positive) effects on W1 conduct problems and (negative) effects on parental monitoring. Parental ND also had indirect effects on W3 conduct problems through parental monitoring.

Parental depression had no direct effect on adolescent ND at W5, but at W1 increased adolescent ND and depression, and decreased parental monitoring (Figure 1). Thus, adolescent initial extensiveness of smoking increased with parental dependence and adolescent initial dependence increased with parental depression. The negative effect of W1 parental monitoring on adolescent extensiveness of smoking at W4 was mediated by reduced adolescent conduct problems at W3.

There was continuity over time of extensiveness of smoking and association with smoking peers. These two factors at W4 had highly significant effects on W5 adolescent ND. The peer socialization path (W1 peer smoking to W4 adolescent extensiveness of smoking) was significant while the path reflecting peer selection (W1 adolescent extensiveness of smoking to W4 peer smoking) was not. The effects of W1 adolescent dependence on W3 depression and conduct problems were not significant. Correlatively, adolescent depression and conduct problems at W3 had no significant direct impact on W5 ND; conduct problems had an indirect effect mediated by W4 extensiveness of smoking (68%) and peer smoking (32%).

Adolescent age, gender, and race/ethnicity were associated with dependence and its risk factors. Age was associated with higher pleasant initial sensitivity, depression, peer smoking, extensiveness of smoking and dependence at W1 and lower conduct problems at W3. Females experienced greater parental monitoring, and higher depression at W1 and W3 than males, while males experienced more conduct problems at W1 and more peer smoking at W4 than females.

Gender specific models

The fully constrained equality model across gender fit well (CFI=.96, RMSEA=.05) and differed significantly from the freed model (X2(33)=52.78, p<.05). Four paths were significantly stronger for males than females: pleasant initial sensitivity to W1 extensiveness of smoking (X2(1)=9.04, p<.001), conduct problems to W4 extensiveness of smoking (X2(1)=11.51, p<.001) and W5 dependence (X2(1)=6.75, p<.01), and age on W1 dependence (X2(1)= 8.95, p<.01). The total effect of W3 conduct problems on W5 ND was stronger for males than females (t=3.39, p<.001). Fit indices for the final model with four freed paths were CFI=.97 and RMSEA=.05. The model explained 51% of the variance in W5 ND for males, 38% for females.

Discussion

We tested a model of risk and protective factors for ND in adolescence and specified direct effects, indirect effects and mediators of adolescent psychosocial characteristics and proximal social contexts of parents and peers on ND in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. Data on parental characteristics were obtained from parents themselves.

The model provided insights into the processes that affect ND in adolescence. These are similar in many respects to those observed for other forms of substance use and deviant behavior but highlight the primary importance of a biobehavioral factor, the initial experiences associated with tobacco use, and the secondary importance of a familial factor, parental ND. Pleasant initial sensitivity to tobacco was the most important predictor of ND and had the strongest total effect of the variables in the model. Pleasant initial sensitivity facilitated continued and extensive smoking, which led to dependence. Individual differences in sensitivity to nicotine may reflect genetic (Ehringer et al., 2007; Pomerleau et al., 1998; Sherva et al., 2008) and environmental influences. Subjective experiences of initial tobacco use may be influenced by expectancies learned from peers, family, and the media. Differences in drug sensitivity may underlie substance dependence more generally and may be a prognostic factor for later dependence on that substance, as shown for cannabis (Fergusson, Horwood, Lynskey, & Madden, 2003).

Dependent parents were more likely to have dependent offspring two years later not only because of the direct impact of parental dependence on adolescent ND but also because these children were more likely to experience pleasant experiences at their initial tobacco use, they were more likely to smoke extensively and to manifest conduct problems. Conduct problems resulted also from lower parental monitoring and, in turn, led to association with smoking peers. Parental monitoring had no direct impact on association with smoking peers, in contrast to its reported impact on association with substance using or delinquent peers (Patterson et al., 1992). It is of interest that early in the process of adolescent dependence, parental ND affects extensiveness of adolescent smoking while parental psychopathology contributes directly to addictive behavior, irrespective of extensiveness of smoking. Indeed, parental depression was a direct risk factor for initial adolescent ND and depression. However, adolescent ND was not associated with later depression nor did depression lead to ND. Conduct problems appear to be more important determinants of ND than depression once young people have started to smoke.

Thus, parental influences on child ND are biological and social. Biological effects derive from genetic liability indexed by parental dependence, and prenatal or postnatal tobacco exposure, which impact adolescent ND directly or indirectly through subjective experiences associated with tobacco use and conduct problems. Social influences derive from parental socialization, such as role modeling of smoking and inadequate monitoring, which were investigated in this study, as well as transmission of favorable attitudes toward tobacco and tobacco availability, which were not.

Extensiveness of smoking and peer smoking six months earlier were immediate predictors of adolescent ND at the final interview. Compared with the non-significant effect of adolescent's own smoking on peer smoking, the significant effect of peer smoking on extensiveness of smoking supports socialization rather than selection effects (Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Kandel, 1978) in the friendships of smoking adolescents. Imitation and social reinforcement would account for the influence of peer smoking on adolescent ND.

While the model had greater explanatory power for males than females, associations between risk and protective factors and ND were mostly common across gender, with two exceptions. Conduct problems had stronger effects on extensiveness of smoking and on ND among males than females. This is in contrast to Costello et al. (1999)'s analyses of cross-sectional data.

The study has limitations. The sample was drawn from Chicago schools and is not nationally representative. We focused on parental and peer influences and did not consider the more distal social contexts of school and community. School attitudes toward smoking, smoking levels, anti-smoking policies, the banning of vending machines, and neighborhood characteristics, such as safety and disorganization, have been found to affect lifetime, current and daily smoking, but have not been examined for ND (Ennett, Flewelling, Lindrooth & Norton, 1997; Kandel et al., 2004; Leatherdale, Cameron, Brown, & McDonald, 2005; O'Loughlin et al., 2009). Since the parent sample included very few fathers (N=37), results apply only to mothers. To our knowledge, two studies examined the effect of paternal parenting on child ND or heavy smoking. Contradictory findings were reported: getting along with father did not predict ND (DiFranza et al., 2007a), while father warmth and hostility predicted son's heavy smoking (White, Johnson, & Buyske, 2000). Future studies on adolescent ND should include school and community variables, family structural variables, and psychosocial variables from mothers and fathers. Genetic and environmental contributions should also be examined together.

Within these limitations, the study provides insights into the factors and developmental process underlying nicotine addiction in adolescence. Overall, the process is similar for males and females. The overall significance of initial sensitivity to tobacco and parental dependence underscores the roles of biological and genetic factors in ND. The roles of parental monitoring, adolescent problem behaviors, peer smoking and parental depression highlight the additional importance of familial, behavioral and social factors and the multifactorial etiology of nicotine addiction. Prevention and intervention efforts should address multiple risk factors targeted toward parents and children, especially parental smoking, parenting skills, and adolescent mental health. Efforts targeted toward parental smoking cessation would not only have direct effects on reducing youth addictive smoking, but would also have indirect effects through improved parental monitoring and reduction of youth conduct problems and affiliation with smoking peers. Educational initiatives that would teach youths to identify signals that increase the likelihood of ND, such as heightened pleasant sensitivity to tobacco and initial symptoms of ND, might deter youths from continuing smoking and encourage them to seek help to stop smoking (Doubeni et al., 2010).

Acknowledgment

This research was partially supported by DA12697, DA026305 and K-5 DA0081 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and ALFCU51672301 and ALF6814 from Legacy to Denise Kandel.

Abbreviations

- ND

nicotine dependence

Footnotes

No conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Auther; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Peters L. The psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:80–85. doi: 10.1007/s001270050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Al Koudsi N, Rodriguez D, Wileyto EP, Shields PG, Tyndale RF. The role of CYP2A6 in the emergence of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e264–274. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Ennett SE. Peer influence on adolescent drug use. American Psychology. 1994;49:820–822. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.9.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196:440–446. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Long JS. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, C.A.: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Psychiatric disorders and stages of smoking. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Czeisler LJ, Shapiro J, Cohen P. Cigarette smoking in young adults. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1997;158:172–188. doi: 10.1080/00221329709596660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin LA, Presson CC, Todd M, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1189–1201. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Berry CC. Which adolescent experimenters progress to established smoking in the United States? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1997;13:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker LC, Donny E, Tiffany S, Colby SM, Perrine N, Clayton RR. The association between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among first year college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, O'Loughlin J, McNeill AD, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow-up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:228–235. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Pbert L, O'Loughlin J, McNeill AD, et al. Susceptibility to nicotine dependence: The Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth 2 study. Pediatrics. 2007a;120:e974–983. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, O'Loughlin J, Pbert L, Ockene JK, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007b;161:704–710. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubeni CA, Reed G, DiFranza JR. Early course of nicotine dependence in adolescent smokers. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1127–1133. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, Clegg HV, Collins AC, Corley RP, Crowley T, Hewitt JK, et al. Association of neural nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;144B:596–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Balster RL. Initial tobacco use episodes in children and adolescents: Current knowledge, future directions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:S41–S60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett S, Flewelling RL, Lindrooth RC, Norton EC. School and neighborhood characteristics associated with school rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwook LJ, Lynskey MT, Madden PAF. Early reactions to cannabis predict later dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Carlson G, Schneider J, Nolan EE, Mattison RE, et al. A DSM-IV-referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:671–679. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais A, O'Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G, Bancej C, Tremblay M. Milestones in the natural course of cigarette use onset in adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175:255–261. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB, Davies M. Ethnic differences in predictors of initiation and persistence of adolescent cigarette smoking in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4:1–15. doi: 10.1080/14622200110103197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Hu M, Schaffran C, Kandel DB. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence among adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1341–1351. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185d2ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Guo J. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB, Flay BR, Hedeker D, Siddiqui O, Day LW. The influence of friends' and parental smoking on adolescents smoking behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psycholgy. 1995;25:2018–2047. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu M-C, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the U.S. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isensee B, Wittchen H-U, Stein MB, Höfler M, Lieb R. Smoking increases the risk of panic. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:692–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. Lisrel 8: Structural equation modeling with the simplis command language. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84:427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Drug and drinking behavior among youth. Annual Review of Sociology. 1980;6:235–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu M-C, Griesler PC, Schaffran C. On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kiros G-E, Schaffran C, Hu M-C. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:128–135. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P. The contribution of mothers and fathers to the intergenerational transmission of cigarette smoking in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Karp I, O'Loughlin J, Hanley J, Tyndale RF, Paradis G. Risk factors for tobacco dependence in adolescent smoking. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:199–204. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Pawlby SJ, Caspi A. Maternal depression and child antisocial behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:173–181. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST, Cameron R, Brown KS, McDonald PW. Senior student smoking level at school, student characteristics, and smoking onset among junior students: A multilevel analysis. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, et al. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM. Childhood conduct problems, attention deficit behaviors, and adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:281–302. doi: 10.1007/BF01447558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Hitchings JE, Spoth RL. The interaction of conduct problems and depressed mood in relation to adolescent substance involvement and peer substance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;26:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user's guide. Author; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- O'Loughlin J, Karp I, Koulis T, Paradis G, DiFranza J. Determinants of first puff and daily cigarette smoking in adolescents. Amercian Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:585–597. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking and their correlates from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:400–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial Boys. Castalia; Eugene: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. Depression, anxiety, and smoking initiation. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1518–1522. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson W, von Soest T. Smoking, nicotine dependence and mental health among young adults. Addiction. 2009;104:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS, Namenek RJ. Early experience with tobacco among women smokers, ex-smokers, and never smokers. Addiction. 1998;93:595–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93459515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Scherrer JF, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Pergadia ML, et al. Initial response to cigarettes predicts rate of progression to regular smoking: Findings from an offspring-of-twins design. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Comer J. Scoring Manual: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) Columbia University; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sherva R, Wilhelmsen K, Pomerleau CS, Chasse SA, Rice JP, Snedecor SM, et al. Association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in neruonal acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 5 (CHRNA5) with smoking status and with “pleasurable buzz” during early experimentation with smoking. Addiction. 2008;103:1544–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Refining models of dependence. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:611–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Johnson V, Buyske S. Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12:287–310. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramaratne PJ, Weissman MM. Onset of psychopathology in offspring by developmental phase and parental depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:933–942. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]