Abstract

Objectives

The epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclooxygenase-2 pathways play key and often complementary roles in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer (CRC). This study explores the clinical and biological effects of combined blockade of these pathways

Methods

Cetuximab-naive patients with refractory CRC were treated with cetuximab (400 mg/m2 loading dose followed by weekly cetuximab at 250 mg/m2) and celecoxib (200 mg orally twice daily). Urinary PGE-M, a stable metabolite of PGE-2 that correlates with in vivo COX-2 activity, and serum TGF-α, a ligand that binds to EGFR, were measured serially to assess the biological effect of COX-2 and EGFR blockade.

Results

Seventeen patients accrued on this study. Of the thirteen patients evaluable for response, there were two (15.4%) with confirmed partial responses, 4 (30.8%) with stable disease, and 7 (53.8%) with progressive disease. The median PFS for all evaluable patients was 55 days (95% CI [45, 112]; range 10-295 days). This study was terminated early due to lack of sufficient clinical activity. There were no statistically significant differences in serum TGF-α or urinary PGE-M between cycles in responders or nonresponders.

Conclusions

This regimen resulted in response rates similar to those published for cetuximab monotherapy in patients with recurrent CRC. Aside from a higher than expected rate of infusion reactions, no other unexpected toxicities were observed. No differences in serum TGF-α or urinary PGE-M between cycles were seen, suggesting that the appropriate targets may not have been hit.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor pathway, cyclooxygenase-2 pathway, cetuximab, celecoxib, colorectal cancer

Introduction

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway is important in carcinogenesis. It plays key roles in cell proliferation, adhesion, invasion, survival, and angiogenesis. Tumors in which the EGFR pathway is activated include lung cancer, CRC, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and head and neck cancer. Antibodies and small molecule inhibitors acting on different parts of this pathway have shown effectiveness as anti-neoplastic agents in these cancers (1, 2).

In CRC, antibodies to EGFR have been used both as a monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy. Cetuximab, a chimeric neutralizing antibody against the extracellular, ligand-binding domain of the EGFR, was the first EGFR antibody approved by the FDA for the treament of advanced CRC. As a monotherapy, it is associated with a 10% response rate in chemotherapy refractory colorectal cancer. Interestingly, in patients that had progressed on irinotecan-based chemotherapy, the combination of cetuximab and irinotecan yields a 23% response rate whereas single agent cetuximab only had an 11% response rate, suggesting that cetuximab may overcome irinotecan resistance in some tumors (3).

The cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway is another important pathway in carcinogenesis. Cyclooxygenases convert arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, and prostaglandins are involved in vasoconstriction, vasodilation, platelet aggregation, and immunomodulation. There are two isoforms of COX, COX-1 and COX-2. COX-2 is the isoform whose upregulation is most commonly associated with carcinogenesis (4). Preclinical data showed that upregulation of COX-2 in tumor cells resulted in increased PGE2 production and increased tumor invasiveness (5). The increased PGE2 production can then lead to increased production of interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and increased Bcl-2, all of which can favor tumor growth and dissemination. It can also promote proangiogenic factors such as VEGF, bFGF, PDGF, and TGF-β1 (6). COX-2 is overexpressed in many tumor types, including colon, lung, breast, liver, head and neck, pancreas, esophagus, and prostate. Upregulation of COX-2 has been observed in adenomatous colorectal polyps (7) and in Barrett’s esophagus (8), two precancerous states.

Celecoxib, a selective oral COX-2 inhibitor, at a dose of 200 mg bid, is used for arthritis patients. This dose level is also well tolerated. At a higher dose of 400 mg bid, it has been shown to prevent/reduce colon polyps in individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis (9).

COX-2 overexpression may induce EGFR expression, which can enhance tumor growth (10). The human colon cancer cell line COLO 320DM transfected with COX-1 or COX-2 had growth rates two fold faster than mock-transfected cells, increased DNA synthesis, and increased expression of EGFR. The addition of indomethacin, a COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor, suppressed the stimulated growth, the increased DNA synthesis, and the induction of EGFR in the COX-1- and COX-2-transfected cells.

Therefore, this study sought to explore these findings further in the clinical setting by inhibiting these two complementary pathways in patients with metastatic CRC with the combination of cetuximab and celecoxib. Laboratory correlative studies were incorporated to evaluate the biological effect of the combination and to determine whether the targets were sufficiently inhibited. TGF-α, the principal ligand for EGFR, is overexpressed in a variety of tumor types. Pre- and post- treatment serum was collected for these assays. Monoclonal antibody blockade of EGFR may result in increased levels of soluble TGF-α (11, 12). Measurement of COX-2 activity in vivo is difficult given the variability in tumor tissue availability. However, indirect assessment of COX-2 activity may be possible through measurement of endogenous prostaglandin production as assessed by measurement of their urinary metabolites. PGE-M is the principal urinary metabolite of PGE2 (13). Since COX-2 is not constitutively expressed in normal tissues, in patients with CRC, the major source of urinary PGE-M presumably originates within the tumor as a result of COX-2-induced PGE2 production. Changes in urine PGE-M levels in response to a COX-2 inhibitor may serve as a surrogate marker of COX-2 activity within the tumor itself. Pretreatment and post-treatment urine PGE-M levels were assayed to assess for the adequacy of COX-2 inhibition. These correlative studies were designed to determine the feasibility of using these biomarkers as predictive markers of efficacy in subsequent trials.

Patients and Methods

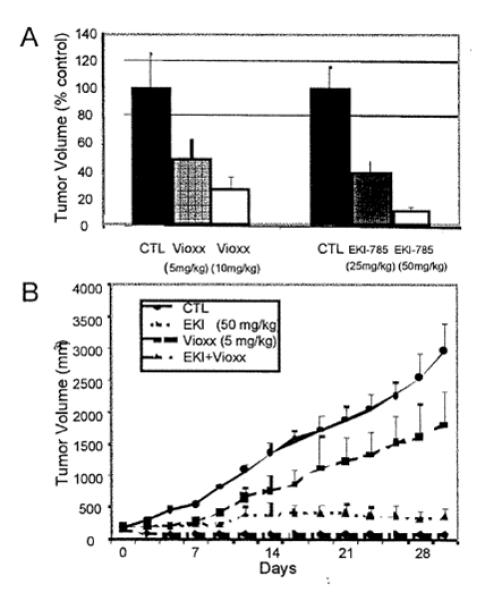

Xenograft experiments

We previously identified that a human CRC cell line, HCA-7, expresses COX-2 (14). These cells retain the capacity to form a uniform polarizing monolayer when cultured on Transwell filters. HCA-7 cells (2 × 107) were injected subcutaneously into nu/nu mice. When tumors reached approximately 150 mm3, the mice received EKI-785 (25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg three times a week, i.p.), rofecoxib (5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg daily gavage), or both EKI-785 (50 mg/kg) and rofecoxib (5 mg/kg) for one month. EKI-785 was supplied by Wyeth-Ayerst (Madison, N.J.) and rofecoxib was supplied by Merck (Rahway, NJ). Tumor volumes were measured three times a week. There were ten mice per group. Control for rofecoxib was methylcellulose by gavage, and control for EKI-785 was DMSO by intraperitoneal injection.

Clinical Trial

This was a phase II open label single institution study to evaluate the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with celecoxib in colorectal cancer. Given that both agents are well tolerated and had non-overlapping toxicities, the doses chosen for the study were full doses of both agents, i.e., cetuximab 400 mg IV loading dose followed by 250 mg IV weekly and celecoxib 200 mg PO bid. There was a planned toxicity evaluation after the first six patients with dose-de-escalation if the combination was not well tolerated.

Eligibility

Patients were required to have histologically confirmed metastatic or unresectable colorectal cancer for which standard curative or palliative measures do not exist or are no longer effective aside from EGFR antibody therapy. They had to have progressed after ≥1 chemotherapy regimen for advanced disease. Prior therapy with agents targeting the EGFR pathway was not allowed. Patients had to be ≥18 years old, have an ECOG performance status ≤2, and have measurable disease (at least one lesion with longest diameter ≥20 mm with conventional techniques or ≥10 mm with spiral CT scan) with a life expectancy of > 3 months. They had to have adequate organ and marrow function, defined as absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1500/ul, platelets ≥ 100,000/ul, normal total bilirubin, AST(SGOT)/ALT(SGPT) ≤ 2.5× institutional upper limit of normal or ≤ 5× normal if liver metastases are present, normal creatinine or estimated creatinine clearance ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 by Cockroft-Gault calculation for patients with creatinine levels above institutional normal. Patients had to agree to use adequate contraception. Patients were required to understand and give written informed consent. Ineligibility criteria included patients with chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 4 weeks (6 weeks for nitrosoureas or mitomycin C) prior to entering the study or patients who have not recovered from adverse events from prior therapy. Patients receiving investigational agents or patients with brain metastases were ineligible. Patients who had previously had a severe infusion reaction to a monoclonal antibody were ineligible. Aside from a daily 81 mg aspirin, patients were required to be off all other selective or non-selective COX-2 inhibitors for a minimum of two weeks prior to study entry. Patients with serum calcium > 12 mg/dl were ineligible. Patients were not allowed to have had major surgery within 4 weeks of study entry or minor surgery within 1 week of study entry. Significant traumatic injury occurring within 28 days of treatment initiation was not allowed. Patients with gastrointestinal tract disease resulting in inability to take oral medication or a requirement for IV alimentation or prior surgical procedures affecting absorption or active peptic ulcer disease were ineligible. Patients with uncontrolled intercurrent illness or psychiatric illnesses/social situations that would limit compliance with study requirements were also ineligible. Pregnant women or individuals with HIV were ineligible.

Treatment

The study was conducted at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Patients were accrued from October 2005 to October 2006. Cetuximab was given weekly. During week one, patients received cetuximab at 400 mg/m2 over 2 hours. For the initial cetuximab dose, patients were pre-medicated with diphenhydramine hydrochloride 50 mg (or an equivalent antihistamine) intraveneously given 30-60 minutes prior to the first dose of cetuximab. Additional pre-medication for the initial treatment and for subsequent treatments was at the Investigator’s discretion. Subsequent doses were administered at 250 mg/m2 over 1 hour. Subsequent doses of cetuximab could be dose reduced and/or dose delayed secondary to toxicity. Patients were instructed to take celecoxib 200 mg orally twice a day. Cetuximab was supplied free of charge by Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, NJ). Celecoxib was supplied free of charge by Pfizer, Inc (New York, NY).

Patients were closely monitored during the cetuximab infusion and observed for one hour afterwards for signs of anaphylaxis. If grade 3 or greater infusion reaction occurred, patients were removed from study. All toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 3.0.

Serum and urine samples were obtained prior to the start of therapy, 1 week after starting therapy, and at the beginning of each new cycle. On the days of serum sampling, celecoxib was taken prior to or during the cetuximab infusion.

UrinaryPGE-M

PGE2 production was quantified by measuring the major metabolite of PGE2 - 11-α-hydroxy-9,15-dioxo-2,3,4,5,20-pentanor-19-carboxy-prostanoic acid (PGE-M) by mass spectrometry as previously described (15). For these analyses, stable isotope dilution methodology was employed utilizing chemically synthesized [2H7] PGE-M as a standard. For the quantification of this compound in human urine, the following approach was utilized. Urine (1 ml) and ~20 ng [2H7] PGE-M was acidified with HCl (1M) to pH3 and 0.5 ml of 0-methylhydroxylamine HCl (40 mg) in acetate buffer (1.5 M, pH 5) was added to form the methoxamine. The prostanoid derivative was extracted twice as the carboxylic acid at pH 2.5 (HCl, 1M) with 3 ml ethyl acetate/hexane (70:30 v/v). After evaporation of the solvent, acetonitrile (30 ul), 35% pentafluorobenzyl bromide in acetonitrile (15 ul) and N-ethyldiisopropylamine (10 ul) were added. The mixture was allowed to react at 40° C for 25 min. The dry sample was then purified by TLC in a solvent system of ethyl acetate/hexane 90:10 v/v. PGE-M has an Rf=0.63. A broad zone (Rf=0.53-0.70) was scraped from the TLC and eluted with ethyl acetate. The solvent was evaporated and the prostanoid derivatized with BSTFA (25 ul) and dimethylformamide (10 ul) for 1 hour. The sample was dried and resuspended in 10 ul undecane for mass spectrometric (MS) analysis. For MS analysis a Finnegan MAT TSQ45 gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer was employed. GC was performed using a DB1701 capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.25 um film thickness). The column temperature was programmed from 190° C to 300° C at 20° C per min. The major ion generated in the NICI mass spectrum of the PFB ester, O-methyloxime, TMS ether derivative of PGE-M is m/z 637 and the corresponding ion generated by the [2H7]PGE-M standard was m/z 644. Levels of endogenous PGE-M in a biological sample were calculated from the ratio of intensities of the ions m/z 637 to m/z 644.

Methods for analyzing serum TGF-α

Methods utilized for analyzing serum for the ligand TGFα were previously reported (12).

Methods for detection of cetuximab-crossreacting IgE

The cetuximab-crossreacting IgE in the pre-cetuximab treatment serum samples were detected as a part of a previously published study (16)

Tumor Evaluation

Response to therapy was evaluated with serial CT scans every 8 weeks ± 1 week. RECIST criteria (17) were used to determine response to therapy. CR (complete response) or PR (partial response) was confirmed with repeat imaging obtained at least 4 weeks later.

Statistical Methods

The t-test statistic was used to examine mean TGF-α and PGEM differences between response groups at the first treatment time. Additionally, average group differences between the first and second treatment cycle were examined by way of a repeated measures analysis of variance. Differences in survival and time to progression curves were tested using the log-rank test statistic.

Results

Tumor xenografts

We previously showed that administration of TGF-α to the basolateral compartment of polarized HCA-7 cells, a human CRC cell line, results in increased expression of COX-2 and the release of eicosanoids, including PGE2, into the basolateral medium (14). More recently, we have reported that combined blockade of cell surface cleavage of TGF-α (TACE inhibitor), EGFR ligand uptake (cetuximab) and EGFR tyrosine kinase (EKI-785, an irreversible EGFR TKI) results in cooperative growth inhibition of HCA-7 cells in vitro (2). In these studies, EKI-785 was the most potent single agent. This led to in vivo proof-of-principle experiments in HCA-7 nude mouse xenografts in which we combined EKI-785 with rofecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor. HCA-7 cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice and allowed to grow to approximately 150 mm3.. The mice were then treated with EKI-785 alone, rofecoxibalone , or the combination of rofecoxib and EKI-785. Figure 1A illustrates that rofecoxib and EKI-785 as single agents resulted in concentration-dependent tumor growth inhibition. In Figure 1B, the combination of rofecoxib and EKI-785 resulted in marked growth inhibition. These data suggest that inhibition of both the COX-2 and EGFR can result in cooperative growth inhibition.. However, gefitinib, another EGFR TKI, exhibited no clinical activity in patients with advanced colorectal cancer (18). This led us to conduct the present trial with cetuximab and celebrex.

Figure 1.

Effects of EGFR TKI (EKI-785) and COX-2 inhibitor (rofecoxib) on HCA-7 tumor cell growth in nude mice.

HCA-7 cells (2 × 107) were injected subcutaneously into nu/nu mice. When tumors reached approximately 150 mm3, the mice received EKI-785 (25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg three times a week, i.p.), rofecoxib (5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg daily gavage), or both EKI-785 (50 mg/kg) and rofecoxib (5 mg/kg) for one month. Tumor volumes were measured three times a week. Values are expressed as means +SEM. There were ten mice per group. Panel A represents % control tumor volume at conclusion of experiment. Panel B plots tumor volumes over time. CTL represents control for rofecoxib (methylcellulose by gavage) and EKI-785 (DMSO i.p.), respectively.

Patients

Seventeen patients were enrolled from February 2005 to October 2006. Patient demographics are listed in Table 1. Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. Four patients went off study for toxicity or complications. Three of the patients were removed for grade 3 infusion reaction with the first dose of cetuximab. One patient was removed for grade 2 conjunctivitis. No patient died while on treatment. One patient is still alive.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| n | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 |

| Female | 7 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 15 |

| African American | 2 |

| ECOG PS on Day 1 of treatment | |

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 13 |

| 2 | 2 |

| Stage at original diagnosis | |

| 0 | 1 |

| I | 0 |

| II | 3 |

| III | 7 |

| IV | 6 |

| Prior therapy | |

| 5-fluorouracil | 17 |

| Irinotecan | 17 |

| Oxaliplatin | 17 |

| Bevacizumab | 12 |

| Radiation | 1 |

| Sites of metastases | |

| Liver | 14 |

| Lung | 9 |

| Lymph nodes | 11 |

| Peritoneum | 4 |

| Ovary/vagina/uterus | 2 |

| Adrenal | 2 |

| Pancreas | 1 |

| Spleen | 1 |

Treatment Toxicity

Table 2 lists the grade 3 and 4 toxicities seen in patients on this study. Treatment was well tolerated, and no unexpected toxicities were seen with the exception of a high rate of grade 3 hypersensitivity reactions in this small patient population. The only grade 3 or 4 toxicities attributed to protocol therapy were hypersensitivity reactions and dermatological toxicities. One patient experienced urinary hemorrhage but this was secondary to disease progression. One patient experienced grade 4 neurological toxicity that was due to the development of brain metastases. One patient reported grade 3 sensory neuropathy but this was present prior to start of therapy and did not worsen on therapy. An episode of grade 3 constipation was felt to be unrelated to therapy as it was present at the start of therapy. A patient had grade 3 urinary retention that was present prior to start of protocol therapy and did not change on therapy.

Table 2.

| Toxicity | Grade 3 n (%) |

Grade 4 n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic reaction/Hypersensitivity |

3 (18) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) |

| Constipation | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Dermatologic | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| Anemia | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| Hemorrh age, GU – Bladder |

1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Neurological – Brain metastases |

0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) |

| Sensory neuropathy | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Urinary retention | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

As mentioned, the rate of grade 3 hypersensitivity reactions (3/17 patients, 17.6%) was high for this population compared to the rate reported in the package insert (3%) (19). It has previously been reported that hypersensitivity reactions to cetuximab are secondary to a pre-existing IgE antibody against cetuximab (15). The patients in this study made up part of the data set for that published study and the IgE values are listed in Table 3. The limit of detection of the assay is 0.35 IU/mL. All of the patients with grade 3 hypersensitivity reactions had detectable IgE antibodies against cetuximab. Patient 9 had a minimally detected IgE antibody level of 0.37 IU/mL. He had a minimal reaction manifested as pruritis affecting the palms and feet and red hands that was judged by the treating physician to not represent a true hypersensitivity reaction. The other three patients with detectable IgE levels had clear grade 3 hypersensitivity reactions and were not re-challenged.

Table 3.

| Patient number |

IgE (IU/mL) | Grade 3 hypersensitivity reaction |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.35 | No |

| 2 | 0.35 | No |

| 3 | 0.35 | No |

| 4 | 0.35 | No |

| 5 | 7.01 | Yes |

| 6 | 0.35 | No |

| 7 | 0.80 | Yes |

| 8 | 0.35 | No |

| 9 | 0.37 | No |

| 10 | 0.35 | No |

| 11 | 9.20 | Yes |

| 12 | 0.35 | No |

| 13 | 0.35 | No |

| 14 | 0.35 | No |

| 15 | 0.35 | No |

| 16 | 0.35 | No |

| 17 | 0.35 | No |

Clinical Efficacy

Out of the thirteen evaluable patients, there were two patients (15.4%) with confirmed partial responses (PR), 4 patients (30.8%) with stable disease (SD), and 7 (53.8%) with progressive disease (PD).

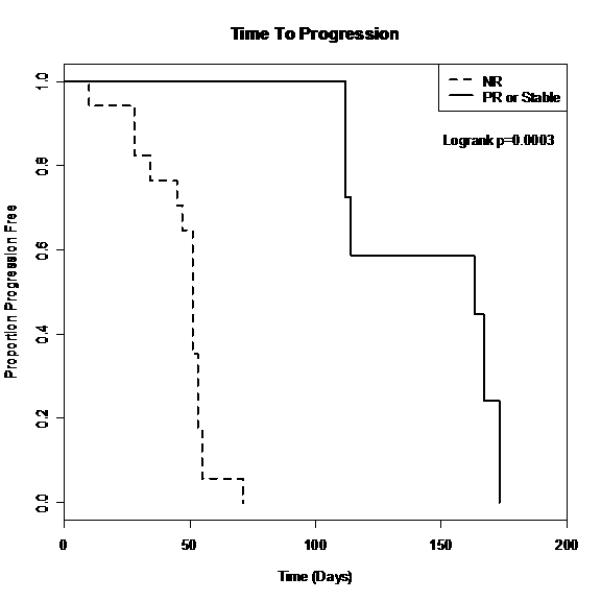

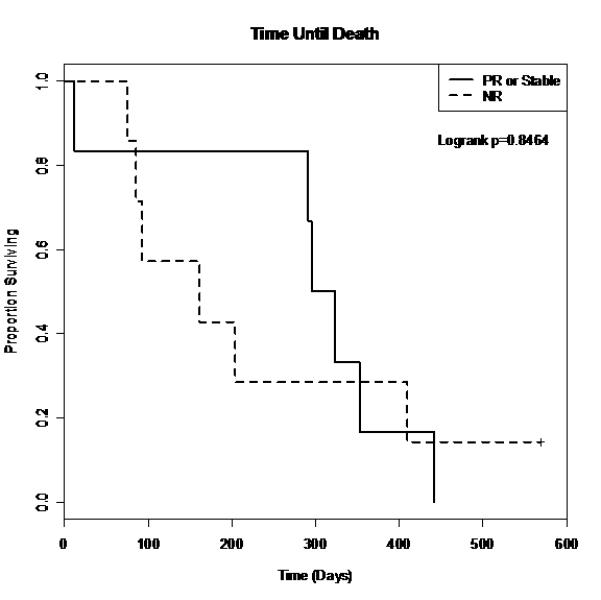

The median PFS for all patients (except for the 3 with grade 3 infusion reactions and one with toxicity) was 55 days (95% CI [45, 112]; range 10-295 days). For patients with stable disease or a PR, the median PFS was 138 days (95% CI [112, 167]). For patients with progressive disease, the median PFS was 47 days (95% CI [28, 55]). As shown in figure 2 there was a statistically significant difference between the responders and progressive disease survival curves (p=0.0003). There was no statistically significant difference in survival times between the responders and progressive disease groups (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for PFS

Figure 3.

Survival curves for time until death.

The longest surviving patient was a patient who progressed after two cycles on study. He was subsequently treated with irinotecan and cetuximab for nine months prior to progression. Of note, he had previously progressed on irinotecan as well. He eventually passed away 22 months after he enrolled on study.

Biologic Correlative Studies

The objective of the biologic correlative studies was to determine whether the combination of cetuximab and celecoxib elicited any change in the EGFR or COX-2 pathway. Table 4 describes the distributions and p-values for the urinary PGE-M and serum TGF-α levels for two treatment cycles; there were no statistically significant differences between the responders and progression groups. Additionally, there were no statistically significant difference in TGF-α or PGE-M between cycles in either the responder group (p=0.0524) or the progressive group (p=0.0609). There were no statistically significant changes in PGE-M between cycles in either the responder group or the progressive group (p=0.9610 and p=0.5092, respectively).

Table 4.

Biologic Correlates

| Variable | Treatment Cycle | Stable or PR | NR | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (N) | Mean ± SD (N) | |||

| PGE-Ma | 1 | 30.42 ± 17.15 (6) | 21.94 ± 17.13 (11) | 0.6166 |

| 2 | 28.42 ± 25.73 (6) | 29.76 ± 41.34 (4) | 0.8981 | |

| TGF-α | 1 | 26.38 ± 17.15 (5) | 25.90 ± 10.93 (10) | 0.8787 |

| 2 | 48.02 ± 16.94 (6) | 49.95 ± 27.27 (4) | 0.9391 |

test statistics based on log transformed data

Discussion

The EGFR and cyclooxygenase pathways are targets for pharmacological therapy. Several EGFR inhibitors have been FDA-approved for cancer therapy including small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as erlotinib and monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab. While the monoclonal antibodies have shown single agent efficacy in colorectal cancer (2, 20), the small molecule inhibitors are ineffective in this malignancy (17). Blockade of the cyclooxygenase pathway has proven effective in decreasing the incidence of precancerous polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. However, studies in colorectal cancer have yet to show that blockade of this pathway is effective in controlling malignancy. COX-2 inhibition does not appear to add to the benefit of chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer (21-24). In fact, preclinical data suggests that it may attenuate the effect on 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines (25)

Because COX-2 overexpression can lead to EGFR expression, we hypothesized that inhibition of both pathways may lead to more effective inhibition of tumor growth than either alone. Unfortunately, the response rates in this study did not support this hypothesis and the study was terminated early given the lack of sufficiently promising clinical activity for this drug combination. The RR and PFS were similar to that reported for single agent cetuximab (3). Not surprisingly, the patients who had SD or PR had improved PFS compared to the patients with PD. What is unexpected is that there was no statistically significant difference in survival between the patients with SD or PR and the patients with PD. Equally interesting is the fact that the longest surviving patient on this study had progressive disease on a prior irinotecan regimen and on this regimen of cetuximab and celecoxib, but he subsequently had a prolonged period of nine months of stable disease on the combination of cetuximab and irinotecan. While it had previously been speculated that cetuximab may reverse irinotecan resistance, it has not been reported that cetuximab and irinotecan can control disease in patients who had previously progressed on both of these drugs separately.

No unexpected toxicities were seen with the combination. However, there was an unexpectedly high rate of hypersensitivity reactions seen with the first infusion of cetuximab. Although the rate of severe hypersensitivity reactions seen in this study (17.6%) is higher than the previously reported rates of 1-3% in other large studies, it is similar to the rate reportedly for the region of the United States where this study was conducted (26). As previously reported, this hypersensitivity reaction appears to be secondary to a pre-existing IgE antibody in these patients, and the prevalence of this IgE antibody parallels the hypersensitivity rate seen (15).

In this small patient sample, the response rates seen were similar to those previously reported for single agent cetuximab. Given the lack of statistically significant differences in TGF-α or PGE-M between cycles, it is possible that lack of clinical synergy between cetuximab and celecoxib may be secondary to dosing at levels too low to achieve significant effective systemic biological blockade of the pathways. It may be that we need more potent EGFR and/or COX 2 inhibitors to demonstrate a synergistic effect with the combination in a clinical setting.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Grant Number P50CA095103 and CA46413 to Dr. Robert Coffey from National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI or NIH.

This study was also supported with funding by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Cetuximab was supplied by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Imclone.

Celecoxib was supplied by Pfizer.

We appreciate Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills at the University of Virginia for performing the IgE detection assay.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Emily Chan: Advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Imclone, and Pfizer. Research funds from Pfizer.

Jordan D. Berlin: Advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Imclone, and Pfizer. Research funds from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Imclone.

Mace L. Rothenberg: Leadership position at Pfizer Oncology. At the time the work was performed, he was a Professor at Vanderbilt and had no financial conflict with Pfizer.

Christine H. Chung: Research funds from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Merck, AstraZeneca.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pal SK, Pegram M. Epidermal growth factor receptor and signal transduction: potential targets for anti-cancer therapy. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2005;16:483–94. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200506000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merchant NB, Voskresensky I, Rogers CM, et al. TACE/ADAM-17 : A component of the epidermal growth factor receptor axis and a promising therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:1182–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JR, DuBois RN. COX-2: A molecular target for colorectal cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2840–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsujii M, Kawano S, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human colon cancer cells increases metastatic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3336–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S, et al. Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell. 1998;93:705–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasaki T, Nosho K, Ohnishi M, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 overespression is common in serrated and non-serrated colorectal adenoma, but uncommon in hyperplastic polyp and sessile serrated polyp/adenoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagorce C, Paraf F, Vidaud D, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 is expressed frequently and early in Barrett’s oesophagus and associated adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:457–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbach G, Lynch PM, Phillips RKS, et al. The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1946–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinoshita T, Takahashi Y, Sakashita T, et al. Growth stimulation and induction of epidermal growth factor receptor by overexpression of cyclooxygenases 1 and 2 in human colon carcinoma cells. Biochimica et Biophysica. 1999;1438:120–30. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutsaers AJ, Francia G, Man S, et al. Dose-dependent increases in circulating TGF-α and other EGFR ligands act as pharmacodynamic markers for optimal biological dosing of cetuximab and are tumor independent. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15:2397–405. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burdick JS, Ching EK, Tanner G, et al. Treatment of Menetrier’s disease with a monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1697–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphey LJ, Williams MK, Sanchez SC, et al. Quantification of the major urinary metabolite of PGE2 by a liquid chromatographic/mass spectrometric assay: determination of cyclooxygenase-specific PGE2 synthesis in healthy humans and those with lung cancer. Anal Biochem. 2004;334:266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Franklin KL, Graves-Deal R, et al. Myristoylated Naked2 escorts transforming growth factor α to the basolateral plasma membrane of polarized epithelial cells. PNAS. 2004;101:5571–76. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401294101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schweer H, Meese CO, Seyberth HW. Determination of 11 α-hydroxy-9, 15-dioxo-2,3,4,5,20-pentanor-19-carboxyprostanoic acid and 9 α, 11 α -dihyroxy-15-oxo-2,3,4,5,20-pentanor-19-carboxyprostanoic acid by gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1990;189:54–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung CH, Mirakur B, Chan E, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-α-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1109–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New Guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothenberg ML, LaFleur B, Levy DE, et al. Randomized phase II trial of the clinical and biological effects of two dose levels of gefitinib in patients with recurrent colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9265–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cetuximab package insert.

- 20.Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, et al. Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;25:1658–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan C-X, Loehrer P, Seitz D, et al. A phase II trial of irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin combined with celecoxib and glutamine as first-line therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2005;69:63–70. doi: 10.1159/000087302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Rayes BF, Zalupski MM, Manza SG, et al. Phase II study of dose attenuated schedule of irinotecan, capecitabine, and celecoxib in advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:283–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0472-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiello E, Giuliani F, Gebbia V, et al. FOLFIRI with or without celecoxib in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized phase II study of the Gruppo Oncologico dell’Italia Meridionale (GOIM) Ann Oncol. 2006;17(Suppl 7):vii55–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohne C-H, De Greve J, Hartmann JT, et al. Irinotecan combined with infusional 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid or capecitabine plus celecoxib or placebo in the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. EORTC study 40015. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:920–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim YJ, Rhee JC, Bae, et al. Celecoxib attenuates 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in HCT-15 and HT-29 human colon cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1947–52. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i13.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neil BH, Allen R, Spigel DR, et al. High incidence of Cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3644–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]