Abstract

Lung metastases are the main cause of death in patients with osteosarcoma (OS). Salvage chemotherapy has been largely unsuccessful in improving the long-term survival of these patients. Understanding the mechanisms that play a role in the metastatic process may identify new therapeutic strategies. We have demonstrated that the cell surface Fas expression, the Fas/FasL signaling pathway, and the constitutive expression of FasL in the lung microenvironment play a critical role in the metastatic potential of OS cells. Here we review the status of Fas expression in two sets of OS cells, human SAOS and LM7 and murine K7 and K7M2, which differ in their ability to metastasize to the lungs. We demonstrated that Fas expression inversely correlated with metastatic potential. Evaluation of Fas expression in a set of lung metastases from patients demonstrated low or no Fas expression consistent with our hypothesis that Fas+ osteosarcoma cells cannot form metastases. The absence of FasL in the lung allows Fas+ osteosarcoma cells to form metastases indicating that the microenvironment is an important contributor to the metastatic potential of osteosarcoma cells. Disruption of the signal transduction pathway using Fas-associated death domain dominant negative (FDN) also allowed Fas+ cells to form lung metastases. Aerosol Gemcitabine (GCB) upregulated Fas expression and induced tumor regression in wild-type Balb/c mice but not Fas L-deficient mice. In conclusion, Fas constitutes an early defense mechanism that allows Fas+ tumor cells to undergo apoptosis when in contact with constitutive FasL in the lung. Fas− cells or cells with a corrupted Fas pathway evade this defense mechanism and form lung metastases. The aerosol delivery of chemotherapeutic agents that upregulate Fas expression may benefit patients with established pulmonary metastases.

Key words: osteosarcoma, Fas/APO1, Fas ligand, aerosol, gemcitabine

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) accounts for 5% of childhood cancer, and is the most common bone tumor in children and adolescents.(1,2) Survival of patients with nonmetastatic disease at the time of diagnosis has improved dramatically over the past 30 years due to advances in chemotherapy and surgery with 60–65% of patients surviving more than 10 years.(3–5) However, patients who present with metastases at diagnosis or those who have recurrent disease have a poor prognosis, with overall survival rates of less than 20%.(6,7)

OS metastatic disease can have a long latency period between successful control of the primary tumor and the development of pulmonary metastases. OS has a predilection for metastasizing to the lungs compared with other sites, and the sensitivity of OS pulmonary metastases to various treatment regimens has been poor.(8–11) Lung metastasis remains the main cause of death in these patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that a possible cause of treatment failure is the low drug concentration achieved in the target organ by systemic administration.(12–14) Understanding the key mechanisms of metastases, the role that the organ microenvironment plays in supporting or impeding metastatic tumor cell growth, and how to increase drug concentration in the target organ can lead to improved targeted therapy for patients with OS. Here we will review our studies relating to understanding and treating OS lung metastases.

The Fas/FasL Apoptosis Pathway and Osteosarcoma Lung Metastases

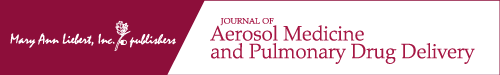

Defects in the apoptotic pathway have been linked to the pathogenesis of cancer cells.(15,16) Cancer can also evade ligand-induced apoptosis by downregulating specific receptors. The Fas pathway (Fig. 1) comprises the Fas receptor (CD95/APO-1) (Fig. 1a) and its ligand, Fas Ligand (FasL) (Fig. 1b). Fas requires trimerization with FasL or agonistic anti-Fas antibody to elicit apoptosis. Once the complex is trimerized, it allows appropriate assembly of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) (Fig. 1c), ultimately resulting in proteolytic cleavage of procaspase 8 (Fig. 1d) and subsequent effector caspases (caspase 3, 6, and 7) (Fig. 1e) with subsequent apoptosis (Fig. 1f). This is the type I, or classical pathway. The type II, or mitochondrial pathway involves procaspase 9 cleavage (Fig. 1g) through the release of cytochrome c (Fig. 1h), which binds to the adaptor molecule Apaf-1 (apoptotic protease activating factor-1) (Fig. 1i) causing an ATP- or dATP-dependent conformational change in the zymogen, or inactive caspase. The activated caspase 9 (Fig. 1j) then cleaves and activates the effector caspases (3, 6, and 7) (Fig. 1e) with subsequent apoptosis (Fig. 1f).(17–20)

FIG. 1.

Activation of the Fas/FasL apoptotic pathway by interaction of Fas+ cells with FasL. The classical (type I) apoptosis pathway involves caspase 8. Fas (a) binds with Fas ligand (FasL, b), the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) (c) assembles, procaspase 8 is cleaved, and caspase 8 (c) is activated. Cleaved caspase 8 (d) triggers activation of effector caspases 3, 6, and 7 (e), and apoptosis occurs (f). The mitochondrial pathway involves caspase 9. Procaspase 9 (g) is activated upon the release of cytochrome c (h), which binds apoptotic protease activating factor- 1 (Apaf-1) (i). The activated complex, apoptosome, (j) cleaves and activates effector caspases 3, 6, and 7 (e), with subsequent apoptosis (f). FADD = Fas-associated death domain protein; FLIP = FLICE inhibitory protein; Bcl-2 = B-cell lymphoma protein 2; IAPs = inhibitor of apoptotic proteins.

Constitutive expression of membrane-bound Fas occurs in a variety of normal cells while FasL is largely restricted to the lungs, testes, gastrointestinal tract, and anterior chamber of the eye. Constitutive FasL expression has been shown to mediate immune privilege.(21–24) Indeed, Fas-mediated apoptosis of effector T lymphocytes terminate immune responses and is anti-inflammatory. Griffith et al.(25–28) demonstrated that, herpes simplex virus type 1,HSV-1, infection in the anterior chamber of the eye in a FasL-deficient mouse resulted in a massive, uncontrolled, and inflammatory cell proliferation in the eye, leading to blindness. Normally, the constitutive FasL would interact with the Fas expressed on T cells, quelling the inflammatory response. However, in the absence of FasL, these T cells proliferated uncontrollably, damaging the eye and causing blindness. In normal mice, this inflammatory response was controlled and eliminated. Thus, changes in Fas or FasL expression can impact the ability of cells to grow and proliferate in a specific organ.

Dysregulation of the Fas pathway has been implicated in tumor development and progression. Loss of Fas function has been shown to be both necessary and sufficient for tumor growth.(29,30) In addition, metastatic cells need a permissive and supportive microenvironment for growth and survival. Our laboratory is particularly interested in the role of Fas–FasL interaction in the development of OS pulmonary metastases because OS metastasizes almost exclusively to the lung, one of the organs where FasL is constitutively expressed. Cells with Fas would therefore be expected to be eliminated when they enter the lung microenvironment and not form metastases. To determine if there was a correlation between Fas expression and metastatic potential, we quantified the Fas expression in a series of human and mouse OS cells. We created a series of sublines with different metastatic potential using human SAOS OS cells by cycling these through the lungs seven times.(31) As shown in Table 1, each passage through the lungs resulted in a subline with greater metastatic potential. Although the parental SAOS cells did not induce lung metastases 17 weeks after intravenous (i.v) injection, the LM6 and LM7 cell lines induced numerous and large pulmonary metastases in 100% of the mice at 12 and 10 weeks, respectively.

Table 1.

Metastatic Characteristics of the SAOS Parental and LM Sublines

| |

|

Lung metastasesb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | Doubling time (h)a | Time (weeks) | Incidencec | Median No. (range) | Diameter (mm) |

| SAOS parental | 45.7 ± 3.3 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LM2 | 43.6 ± 4.2 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LM3 | 44.1 ± 2.6 | 17 | 2/5 | 0 (0–1) | 0.5–1.0 |

| LM4 | 40.0 ± 0.9 | 17 | 3/4 | 9 (0–100) | 0.5–2.0 |

| LM5 | 37.2 ± 3.8 | 17 | 4/4 | 88 (7->200) | 0.5–5.0 |

| LM6 | 34.9 ± 1.4 | 12 | 9/9 | 92 (30->200) | 0.5–5.6 |

3 × 103 cells were cultured at 37°C for 24 h, then pulsed with [3H]-thymidine. Cells were harvested 24, 48, and 72 h later and cpms quantified using a plate harvester (Tomtec, Orange, CT, USA) and beta plate counter (Wallac OY, Turku, Finland). The formula used to calculate doubling time was time × log 2/log (n/no) where no is the cpm of cells incubated for 24 h and n is the cpm of cells incubated for 48 and 72 h. The result was the average of three independent experiments.

1 × 106 of the indicated cells were injected i.v.into nude mice. Mice were euthanized 17 weeks after tumor cell injection (SAOS, LM2, LM3, LM4, and LM5). Mice injected with LM6 cells were euthanized earlier because of impending death. Tumors were harvested and analyzed.

Number of tumor-positive mice/number of inoculated mice.

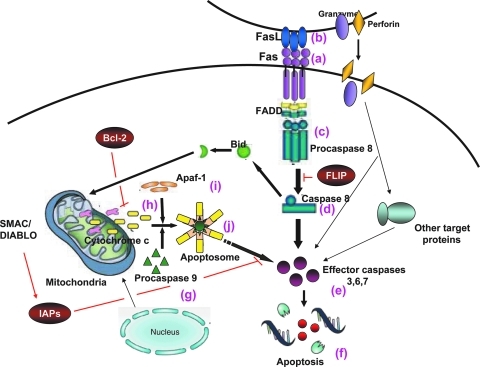

We demonstrated an inverse correlation between Fas expression and the metastatic potential of human OS cells.(32) Highly metastatic LM6 cells showed low levels of Fas mRNA (Fig. 2A) and protein expression(32) compared with the parental SAOS cells.

FIG. 2.

Fas expression in metastatic and non-metastatic OS cells. (A) Northern blot analyses of Fas expression in nonmetastatic parental (P) SAOS cells and the metastatic LM2 and LM6 sublines. GADPH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B) Cell surface Fas in nonmetastatic K7, intermediate metastatic K12, and highly metastatic K7M2 mouse OS cells as quantified using flow cytometry. MFI = mean fluorescence intensity. (C) Immunohistochemistry for Fas expression in K7M2 lung metastases. Normal lung (a). Osteosarcoma lung nodule (b). Tumor necrosis (c). Fas+ cells are depicted in brown and Fas− cells are depicted in blue.

We also analyzed a nonmetastatic murine OS cell line and its metastatic subline.(33) K7 cells originated from a spontaneous Balb/c OS. Similar to our approach with the human cells, the K7M2 metastatic subline was created by cycling K7 cells through the mouse.(33) K7M2 cells are highly metastatic, whereas K7 cells do not form metastases, and K12 cells (an intermediate subline) induce infrequent pulmonary metastases following injection. K7M3 cells were obtained in our lab by recycling metastatic K7M2 cells through the lung an additional time. K7M3 cells induced lung metastases in 90% of mice 4 weeks after intrabone injection. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for Fas again correlated with metastatic potential. (Fig. 2B). The nonmetastatic (K7) and intermediate metastatic cells (K12) showed higher levels of Fas expression than did the metastatic K7M2 and K7M3 cells (Fig. 2B). K7M2 and K7M3 pulmonary metastases were Fas− when stained by immunohistochemistry (blue indicates Fas− cells and brown indicates Fas+ cells) (Fig. 2C). We also analyzed OS pulmonary metastases from 60 patients and found them all to be uniformly Fas−.(34) Taken together, our data indicate that Fas expression inversely correlates with the metastatic potential of OS cells. Cells with low Fas expression are highly metastatic while those with high Fas expression are less metastatic.

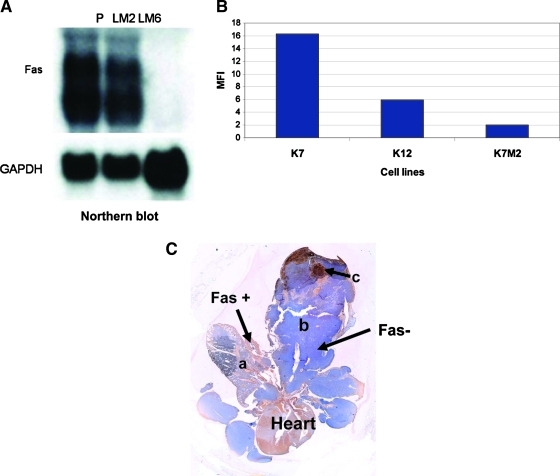

If FasL in the lung plays a role in the clearance of OS cells, Fas+ cells should be eliminated when they enter the lung. By contrast, Fas− cells should survive. Blocking the Fas pathway would therefore be expected to result in the survival of Fas+ cells. To determine the importance of an intact Fas signaling pathway to the metastatic potential of OS cells, we transfected nonmetastastic K7 cells with Fas-associated death-domain, dominant–negative plasmid (K7/FDN).(35,36) K7/FDN cells were resistant to FasL in vitro, were retained in the lung longer than control cells, and induced large lung metastases. Control transfected (K7neo1-1) and parental (K7) cells did not form lung metastases following i.v. injection (Fig. 3). K7/FDN lung nodules were Fas+ when analyzed by immunohistochemistry.(35) These data confirmed that, in the absence of a functional Fas pathway, Fas+ cells can grow in the lung and induce lung metastases.

FIG. 3.

Blocking the Fas signaling pathway allows Fas+ cells to induce lung metastases following i.v. injection. Fas+ K7 cells were transfected with FDN, Fas-associated death domain dominant negative or a control (neo) vector and injected into mice. Mice were euthanized 4 weeks later, and lung metastases were quantified.

We confirmed the importance of FasL in the tumor microenvironment for inhibiting the development of Fas+ OS metastases by demonstrating that Fas+ OS cells were able to grow in the lung when injected into FasL-deficient gld mice but not wild-type Balb/c mice.(36) This further supports our hypothesis that FasL is responsible for the removal of Fas+ OS cells and that the downregulation of Fas can allow OS cells to evade this host defense mechanism.

Rationale for the Use of Aerosol Therapy for the Treatment of Osteosarcoma Lung Metastases

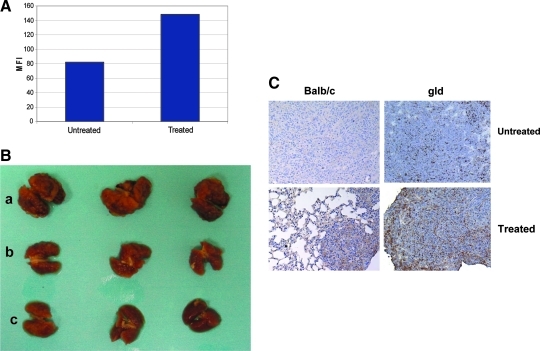

Having demonstrated that OS lung metastases have low or no cell surface Fas in a microenvironment where FasL is expressed, we hypothesized that inducing the upregulation or reexpression of Fas may result in the apoptosis of OS cells in the lung and subsequent tumor regression. We therefore sought to identify agents that increase Fas expression on OS cells. Gemcitabine (GCB) is a pyrimidine antimetabolite that belongs to the nucleoside analog family.(37) Incubation of OS cells with GCB in vitro increased Fas expression (Fig. 4A) and cell sensitivity to FasL.(36,38) Because OS metastasizes almost exclusively to the lung, we elected to test the therapeutic efficacy of GCB against osteosarcoma lung metastases.

FIG. 4.

Aerosol Gemcitabine (GCB) induces Fas expression and the regression of established OS lung metastases in BALB/C mice.(36,38) (A) GCB upregulates Fas expression. Flow cytometry of Fas expression in OS K7M3 cells, showed Fas upregulation in the treated group. MFI = mean fluorescence intensity. (B,C) K7M3 cells (3 × 106) were injected i.v. into Balb/c mice. Mice were treated with aerosol GCB weekly (b) or 3 × /week (c) for 2.5 weeks. Mice were then euthanized. Lung nodules were quantified and analyzed for Fas expression by immunohistochemistry (C). Brown depicts Fas+ cells and blue Fas− cells.

To provide a more effective route of administration of the drug, we chose aerosol delivery of the drug rather than the traditional intravenous route because it has previously shown to have certain advantages. Aerosol administration provides direct delivery of the drug to the target organ where metastases are. Aerosol administration provides uniformly distribution throughout the lungs, avoids the dilutional effects in the blood seen with i.v. administration as well as degradation in the liver and/or gastrointestinal tract, achieving higher pulmonary drug concentrations.(12,39) In addition, GCB solubilizes in saline solution and has no irritant effects. Aerosol treatment was performed as previously described.(38) An AeroTechII nebulizer was used to generate aerosol particles with 5% CO2-enriched air obtained after mixing normal air with CO2 using a blender (Bird3M, Palm Springs, CA, USA) at the air flow rate of 10 L/min. The estimated total deposited amount (D) of inhaled GCB was calculated using the following formula: D = C × V × DI × CF × T, where C is the drug concentration in aerosol volume (1 mg of GCB/mL stock), V is the volume of air inspired in 1 min (for mice, V = 1 L/min per kg), DI is the estimated deposition index (for mice is 0.3), CF is the CO2 factor that allows increase pulmonary deposition of the drug by threefold, and T is the duration of the treatment (min). In two different OS mouse models, K7M3 and DLM8, aerosol GCB induced both the upregulation of Fas on the OS lung metastases and the regression of these established metastases (Fig. 4B).(36,38) Intraperitoneal GCB administered at a similar dose (0.5 mg/kg) had no effect.(38) Indeed, the efficacy of lung-specific delivery on OS pulmonary metastases was shown using a dose eightfold lower than that required for i.v. administration. Because myelosupression is an unwanted side effect following the i.v. administration of GCB, the finding that eigfhtfold less drug is effective when given by aerosol delivery may decrease the toxicity of this drug. Moreover, aerosol gemcitabine at the eightfold lower dose also induced regression of the primary tumor in the limb,(38) indicating that this route of administration can be effective in treating both primary and metastatic disease. Finally, when administered at therapeutic doses, aerosol GCB does not cause local injury to the lung.(36,38) Nevertheless, doses as high as 12 mg/kg could be fatal due to significant pulmonary edema.(39,41,42)

If Fas is critical to the therapeutic efficacy of GCB, the absence of FasL should decrease Gemcitabine's therapeutic effect on OS lung metastases. Indeed, although aerosol GCB induced the upregulation of Fas in K7M3 lung metastases in FasL-deficient mice (Fig. 4C), there was no tumor response.(36) These data confirm that the constitutive FasL in the lung is critical to the therapeutic efficacy of aerosol GCB against OS lung metastases, and that the lung microenvironment may contribute significantly to whether a tumor responds to therapy.

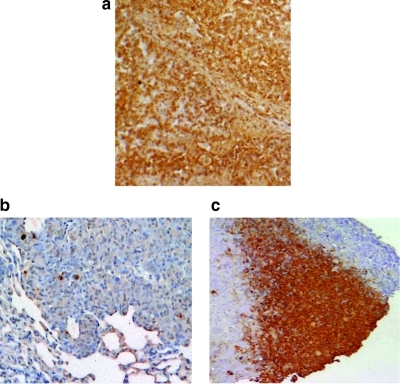

To determine whether aerosol GCB triggers activation of the intermediates of the signal transduction pathway for apoptosis, we examined K7M3 lung nodules for evidence of cleaved caspases and markers of apoptosis. Immunohistochemical analyses of K7M3 lung nodules from Balb/c mice treated with aerosol GCB showed that they had higher levels of cleaved caspase 9 (p = 0.005) and 3 (p = 0.002) expression compare to nodules from the control mice. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), a marker of apoptosis, was also present in these aerosol GCB-treated nodules (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Aerosol GCB induces apoptosis of OS lung metastases. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was used as a marker for apoptosis. Positive cells are stained brown. Lung tumor (a) was used as a positive control. Untreated OS lung metastasis (b) has low to no TUNEL expression compared to GCB treated (c).

The safety of aerosol GCB was recently investigated in dogs with spontaneous OS that developed lung metastases.(40) Aerosol GCB was well tolerated by all the dogs. Fas expression in the lung metastases of the dogs was absent or low prior to therapy, similar to what we had previously observed in humans. Lung metastases removed from the aerosol GCB-treated dogs showed intratumoral necrosis with significantly higher Fas expression compared to the controls (p = 0.0075). TUNEL was also elevated in lung metastases from the GCB-treated dogs.

Similarly, aerosol GCB was shown to be efficacious in an orthotopic model of lung cancer.(39) Effect of regional chemotherapy was confirmed when 31% of mice with intrabronchial injection of tumor cells failed to develop tumor with a significant decrease in tumor growth in the remainder of the cases. A potential role of Fas/FasL in the therapeutic efficacy of GCB in this orthotopic model of lung cancer deserves further investigation because the Fas receptor was shown to be downregulated in the majority of nonsmall lung cell carcinomas.(43)

In summary, the use of organ-specific drug delivery with an agent that upregulates Fas expression on OS cells is a potential novel therapeutic approach for OS patients for whom standard treatment has failed. Aerosol GCB upregulated Fas expression and induced tumor regression. It is our interpretation that by upregulating cell surface Fas on OS cells, aerosol GCB increased the sensitivity of these cells to FasL-mediated apoptosis. Aside from its direct cytotoxic effect as a nucleoside analog, GCB's therapeutic effect may be mediated by its ability to upregulate Fas, thereby spontaneously activating the Fas/FasL apoptosis pathway, particularly in organs such as the lung, where FasL is constitutively expressed. Taken together, our preclinical data and the most recent safety data in dogs with OS support the clinical investigation of aerosol GCB in patients with OS lung metastases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA42992 (E.S.K.) and National Institutes of Health Core Grant CA16672.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Young JL., Jr Ries LG. Silverberg E. Horm JW. Miller RW. Cancer incidence, survival, and mortality for children younger than age 15 years. Cancer. 1986;58(2 Suppl):598–602. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860715)58:2+<598::aid-cncr2820581332>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson M. Pediatric osteosarcoma: therapeutic strategies, results, and prognostic factors derived from a 10-year experience. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1988–1997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.12.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe N. Osteosarcoma. Pediatr Rev. 1991;12:333–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe N. Recent advances in the chemotherapy of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. 1972. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;270:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe N. The classic: recent advances in chemotherapy of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. 1972. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:19–21. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000180509.90557.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe N. Carrasco H. Raymond K. Ayala A. Eftekhari F. Can cure in patients with osteosarcoma be achieved exclusively with chemotherapy and abrogation of surgery? Cancer. 2002;95:2202–2210. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marina N. Gebhardtb M. Teotc L. Gorlicket R. Biology and therapeutic advances for pediatric osteosarcoma. Oncologist. 2004;9:422–441. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-4-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bielack SS. Marina N. Ferrari S. Helman LJ. Smeland S. Whelan JS. Heman JH. Osteosarcoma: the same old drugs or more? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3102–3203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1108. author reply 3104–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kager L. Zoubek A. Pötschger U. Kastner U. Flege S. Kempf-Bielack B. Branscheid D. Kotz R. Salzer-Kuntschik M. Winkelmann W. Jundt G. Kabisch H. Reichardt P. Jürgens H. Gadner H. Bielack SS. for the Cooperative German-Austrian-Swiss Osteosarcoma Study Group: Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2011–2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kager L. Zoubek A. Kastner U. Kempf-Bielack B. Potratz J. Kotz R. Exner GU. Franzius C. Lang S. Maas R. Jürgens H. Gadner H. Bielack S. Skip metastases in osteosarcoma: experience of the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1535–1541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whelan J. Seddon B. Perisoglou M. Management of osteosarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006;7:444–455. doi: 10.1007/s11864-006-0020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma S. White D. Imondi AR. Placke ME. Vail DM. Kris MG. Development of inhalational agents for oncologic use. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1839–1847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyle AH. Huxham LA. Chiam ASJ. Sim DH. Minchinton AI. Direct assessment of drug penetration into tissue using a novel application of three-dimensional cell culture. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6304–6309. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minchinton AI. Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;l6:583–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson CB. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science. 1995;267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Symonds H. Krall L. Remington L. Sáenz-Robles M. Jascks T. Van Dyke T. p53-dependent apoptosis in vivo: impact of p53 inactivation on tumorigenesis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:247–257. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata S. Apoptosis regulated by a death factor and its receptor: Fas ligand and Fas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994;345:281–287. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagata S. Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata S. Fas-mediated apoptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;406:119–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0274-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suda T. Nagata S. Why do defects in the Fas–Fas ligand system cause autoimmunity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(6 Pt 2):S97–S101. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strasser A. Jost PJ. Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson TA. Griffith TS. A vision of cell death: insights into immune privilege. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:167–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson TA. Griffith TS. A vision of cell death: Fas ligand and immune privilege 10 years later. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:228–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt DS. Eis-Hubinger AM. Schneweis KE. The role of the immune system in establishment of herpes simplex virus latency—studies using CD4+ T-cell depleted mice. Arch Virol. 1993;133:179–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01309753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith TS. Yu X. Herndon JM. Green DR. Ferguson TA. CD95-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes in an immune privileged site induces immunological tolerance. Immunity. 1996;5:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffith TS. Brunner T. Fletcher SM. Green DR. Ferguson TA. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffith TS. Ferguson TA. The role of FasL-induced apoptosis in immune privilege. Immunol Today. 1997;18:240–244. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)81663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owen-Schaub L. Chan H. Cusack JC. Roth J. Hill LL. Fas and Fas ligand interactions in malignant disease. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owen-Schaub LB. Fas function and tumor progression: use it and lose it. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:95–96. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia SF. Worth LL. Kleinerman ES. A nude mouse model of human osteosarcoma lung metastases for evaluating new therapeutic strategies. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:501–506. doi: 10.1023/a:1006623001465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worth LL. Lafleur EA. Jia SF. Kleinerman ES. Fas expression inversely correlates with metastatic potential in osteosarcoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:823–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khanna C. Prehn J. Yeung C. Caylor J. Tsokos M. amd Helman L. An orthotopic model of murine osteosarcoma with clonally related variants differing in pulmonary metastatic potential. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18:261–271. doi: 10.1023/a:1006767007547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon N. Arndt CAS. Hawkins DS. Doherty DK. Inwards CY. Munsell MF. Stewart J. Koshkina NV. Kleinerman ES. Fas expression in lung metastasis from osteosarcoma patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:611–615. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000188112.42576.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshkina NV. Khanna C. Mendoza A. Guan H. DeLauter L. Kleineman ES. Fas-negative osteosarcoma tumor cells are selected during metastasis to the lungs: the role of the Fas pathway in the metastatic process of osteosarcoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:991–999. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon N. Koshkina NV. Jia S-F. Khanna C. Mendoza A. Worth LL. Kleinerman ES. Corruption of the Fas pathway delays the pulmonary clearance of murine osteosarcoma cells, enhances their metastatic potential, and reduces the effect of aerosol gemcitabine. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15 Pt 1):4503–4510. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galmarini CM. Mackey JR. Dumontet C. Nucleoside analogues: mechanisms of drug resistance and reversal strategies. Leukemia. 2001;15:875–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koshkina NV. Kleinerman ES. Aerosol gemcitabine inhibits the growth of primary osteosarcoma and osteosarcoma lung metastases. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:458–463. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gagnadoux F. Pape AL. Lemarié E. Lerondel S. Valo L. Leblond V. Racineux J-L. Urban T. Aerosol delivery of chemotherapy in an orthotopic model of lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:657–661. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00017305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez CO. Crabbs TA. Wilson DW. Cannan VA. Skorupski KA. Gordon N. Koshkina N. Kleinerman E. Anderson PM. Aerosol gemcitabine: preclinical safety, in vivo antitumor activity in osteosarcoma-bearing dogs. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2009 doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0773. [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DosReis GA. Borges VM. Zin WA. The central role of Fas-ligand cell signaling in inflammatory lung diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:285–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DosReis GA. Borges VM. Role of Fas-ligand induced apoptosis in pulmonary inflammation and injury. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2003;2:161–166. doi: 10.2174/1568010033484287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brambilla E. Gazdar A. Pathogenesis of lung cancer signaling pathways: roadmap for therapies. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1485–1497. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00014009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]