Abstract

The “hardening hypothesis” states tobacco control activities have mostly influenced those smokers who found it easier to quit and, thus, remaining smokers are those who are less likely to stop smoking. This paper first describes a conceptual model for hardening. Then the paper describes important methodological distinctions (quit attempts vs. ability to remain abstinent as indicators, measures of hardening per se vs. measures of causes of hardening, and dependence measures that do vs. do not include cigarettes per day (cigs/day).) After this commentary, the paper reviews data from prior reviews and new searches for studies on one type of hardening: the decreasing ability to quit due to increasing nicotine dependence. Overall, all four studies of the general population of smokers found no evidence of decreased ability to quit; however, both secondary analyses of treatment-seeking smokers found quit rates were decreasing over time. Cigs/day and time-to-first cigarette measures of dependence did not increase over time; however, two studies found that DSM-defined dependence appeared to be increasing over time. Although these data suggest hardening may be occurring in treatment seekers but perhaps not in the general population of smokers, this conclusion may be premature given the small number of data sets and indirect measures of quit success and dependence in the data sets. Future studies should include questions about quit attempts, ability to abstain, treatment use, and multi-item dependence measures.

Keywords: hardening, nicotine, nicotine dependence, smoking, smoking cessation, tobacco

1. Introduction

Tobacco control has decreased the prevalence of smoking in the U.S.; however, this success has varied across populations (U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1989). For example, current smokers are more likely to have less education and income than prior smokers (MMWR, 2009). One hypothesis to explain such changes is that tobacco control has prompted the “easy-to-quit” smokers to quit and, thus, remaining smokers are those more resistant to stopping smoking. In 2003, two reviews of this “hardening” hypothesis concluded that a) logically, one would expect hardening to occur; but b) there is little empirical evidence of hardening (National Cancer Institute, 2003; Warner and Burns, 2003).

The purpose of the current article is to update these reviews. Because studies sometimes confuse measures of hardening with measures of the causes of hardening, and sometimes fail to distinguish quit attempts from successful abstinence after a quit attempt, the current article first presents a conceptualization of smoking cessation to facilitate discussion of hardening. Next, because definitions of hardening have become so idiosyncratic that they are substantially interfering with understanding the concept (Costa et al., 2010), the article suggests one definition (i.e., decreased ability to stop due to increased nicotine dependence) that is likely to be important to examine. Then, because the last review on hardening was 8 years ago, the paper presents more recent empirical tests of hardening. Finally, the paper suggests methodological assets to include in future studies.

2. A Conceptualization of Smoking Cessation Relevant to Hardening

A change in smoking prevalence among adults can occur by a change in a) the number of young smokers who become adult smokers, b) the number of smokers who die, c) the number of quit attempts, and d) the ability to remain abstinent after a given quit attempt. Prior studies of hardening have focused on one or both of the latter two. In these studies, a quit attempt is typically defined as an attempt to stop smoking in the last year and often requires ≥ 24 hrs of abstinence (Hughes and Callas, 2010). The ability to remain abstinent is typically defined as a period of continuous abstinence for several months among those who have attempted to quit (Hughes et al., 2003). Successful cessation is often defined as the product of quit attempts and ability to remain abstinent and is often defined as the fraction of smokers who convert to continuous abstinence during the last year (National Cancer Institute, 2003).

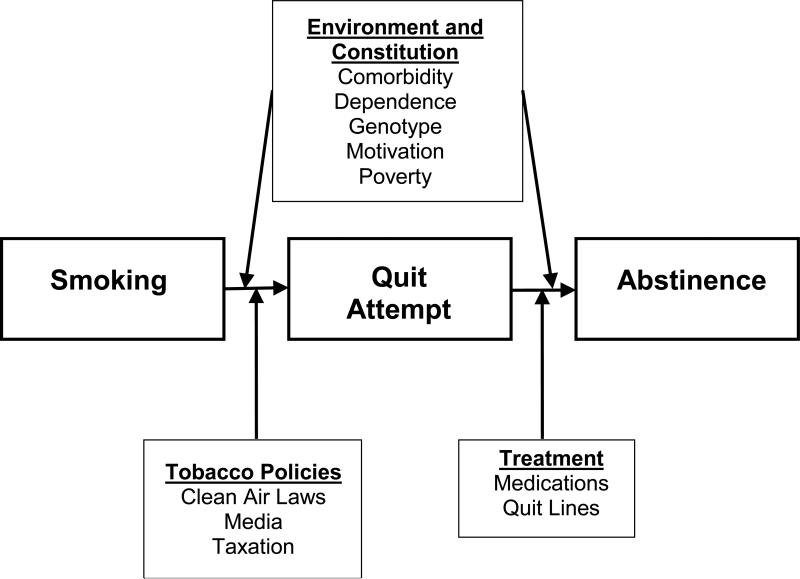

This distinction among quit attempts, the ability to remain abstinent, and successful cessation, is important because it is likely that different variables control the process of making a quit attempt and ability to remain abstinent. For example, tobacco control activities appear to more strongly influence a quit attempt (U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1989) whereas treatment and a smoker's constitution appear to more strongly influence the ability to abstain (Hatsukami et al., 2008) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Heuristical Model of Smoking Cessation

So why are these distinctions important for understanding hardening? As an example, assume that the incidence of successful cessation is declining over time and one concludes hardening is occurring. If this decline is due mostly to fewer quit attempts, the logical solution is to change tobacco policies; e.g., increase taxation, or strengthen warning labels. If this decline is due to less ability to abstain, the logical solution is to increase treatment efforts. As another example, assume the incidence of successful cessation is not changing. Although it is tempting to state that this means no hardening is occurring, it is possible that tobacco control is increasing quit attempts, but other factors (e.g., dependence) are decreasing the ability to remain abstinent, and these two opposing processes cancel each other out (Warner and Burns, 2003).

3. Definitions of Hardening

Hardening has been defined in many different ways (Costa et al., 2010; Hughes and Brandon, 2003). Some focus on the outcome; i.e., decreased quit attempts, decreased ability to abstain, or successful cessation. Others focus on possible causes; i.e., increased nicotine dependence, low motivation, low socioeconomic status and psychiatric co-morbidity. And others require both changes in outcomes and causes. This is problematic for several reasons. First, when definitions include several constructs in the same definition (e.g., low motivation to quit and high dependency), it is unclear which construct is accounting for the hardening. Second, when constructs vary across studies, the studies may not be comparable. For example, hardening can be defined as decreased quit attempts in one study vs. decreased success after quitting in another study. Also hardening can be defined as increased psychiatric co-morbidity in one study and high dependence in another study. In summary, if the concept of hardening becomes overly inclusive, then the term has such heterogeneity that it loses meaning.

The current paper examines hardening defined as decreased ability to remain abstinent on a given quit attempt due to increased nicotine dependence, for several reasons (Hughes and Brandon, 2003); first, the studies that initially used the term “hardening” were referring to this definition (Coambs et al., 1989; Hughes, 1996). Second, the hardening hypothesis has attracted attention, in large part because it could suggest increasing provision of treatment resources (Warner and Burns, 2003;Burns et al., 2003) and most treatments focus on nicotine dependence (Hatsukami et al., 2008). Third, it prevents confusion of hardening with efforts to reduce disparities in smoking. Tobacco control has recognized that remaining smokers are more and more those with lower incomes and education and, thus, have suggested strategies need to change (Murray et al., 2009). However, to label the entire panoply of ways in which smokers have changed over time that might influence quitting as “hardening” is unlikely to be helpful. For example, the policy and treatment strategies needed to address difficulty quitting in poor smokers vs. dependent smokers are likely to be quite different.

4. Populations in Which Hardening Might Be Occurring

Hardening has often been thought of as a concept that should apply to the entire population of smokers; however, the concept has also been examined within subsets of smokers. The most commonly investigated subset has been treatment seekers. This distinction is important, because it is feasible that hardening could be occurring among treatment seekers but not in the population-at-large.

There are several other subgroups in which hardening might be occurring. One way to identify such subgroups is to locate those groups with a low prevalence of smoking (Lee et al., 2007). For example, it is plausible that the few U.S. physicians who smoke (Lee et al., 2007) have a high prevalence of inability to quit. In contrast, this may not occur in Asian physicians, many of whom smoke (Mckay et al., 2006).

The remainder of this review will focus on a) evidence of whether the ability to remain abstinent after a quit attempt has decreased over time in either the general population of smokers or among those who seek treatment and on b) whether dependence has increased in both populations and in doing so, c) point out how future studies could better answer these questions. The review will first discuss the results of the two prior reviews and then those of the newer studies.

5. Search for New Studies

To locate possible new data on changes in the ability to remain abstinent over time due to nicotine dependence in July, 2010, the author searched PubMed, PsychInfo, Cochrane Library, clinicaltrials.gov, CRISP, CDC Tobacco Information and Prevention Database, and EMBASE for articles whose title, abstract or keyword included “hard* AND (smok* OR tobacco OR cigar* OR nicotin*).” The author's own files were searched. Any leads found in the reference lists of the articles obtained were pursued. Finally, a request for papers was posted on the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SNRT; www.srnt.org) listserve. This search located 151 papers, of which 38 studies, not previously reviewed, appeared to be appropriate and were examined. Unfortunately, these 38 revealed few new studies of hardening (see below). Given a) the small number of studies, b) methodological variability (e.g., some are surveys, some are literature reviews), c) variability in samples (some are of all smokers, some are of only treatment seekers), d) variability in time frames (some begin in 1965 and others in 1990), and e) variability in outcomes (point prevalent abstinence vs. 3+ months of abstinence), a meta-analysis was not attempted (Slavin, 1995).

6. Is the Ability to Remain Abstinent On a Given Quit Attempt Decreasing Over Time?

6.1 Results Covered in Prior Two Reviews

The prior two reviews (Warner and Burns, 2003; National Cancer Institute, 2003) cited two population-based surveys that examined the ability to remain abstinent. The U.S. Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS) (i.e., data from the U.S. census) provided a description of the proportion of smokers who were able to remain abstinent for 3+ months among smokers who tried to quit one or more times in the last year (National Cancer Institute, 2003; Warner and Burns, 2003). There was no evidence in this data set that the ability to remain abstinent was declining; i.e., the proportion ranged from 24% to 27% with no time trend. The California (U.S.) Tobacco Survey provided similar data of U.S. smokers in a state with vigorous tobacco control activities (Burns et al., 2003). Among smokers who tried to quit one or more times, the success rate did not change over time. The rate was 17% in 1992/93; 16% in 1995/96 and 20% in 1998/99.

A third study reported in these reviews examined hardening among treatment seekers. This was a literature analysis of quit rates in research studies of cognitive-behavioral treatments for smoking cessation (Irvin and Brandon, 2000). Among treatment seekers, long-term abstinence decreased from about 80% in studies reported in the late 1970s to about 55% in those reported in the late 1990s.

In summary, in these two reviews, there was no evidence of decreasing ability to abstain in the general population of smokers but there was evidence for this in the one treatment sample. Unfortunately, all three studies were based on data collected prior to 2000. Tobacco control activities have probably increased since then, raising the possibility of more recent hardening occurring.

6.2 New Study/Analyses

One new study examined the TUS-CPS but used a different method of analysis and more restrictive definition of abstinence than the prior analyses (Messer et al., 2007). In this data set, successful cessation among those who tried to quit one or more times was 2.7% in 1980-89 and 3.4% in 1990-99; i.e., no indication of hardening.

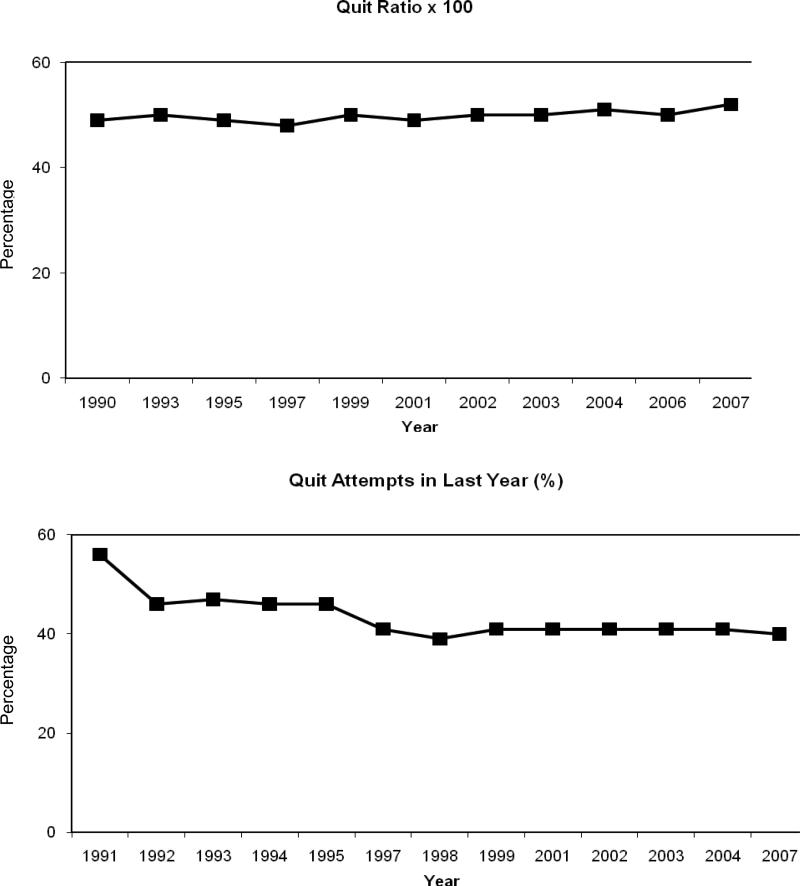

To provide another population-based test of hardening, the author used reports of the U.S. National Health Interview Supplements (NHIS) (Thorne et al., 2008) to plot the annual “quit ratio” over time. The quit ratio is the proportion of ever-smokers who now do not smoke, and is a measure of successful cessation. If hardening is occurring, the quit ratio should decrease over time. Visual inspection of the data suggests the quit ratio increased from 1965 to 1990 (Hughes, 2001b) but has not changed from 1990 to 2007 (Figure 2, top panel). Thus, these data appear to contradict the hypothesis that the ability to abstain is decreasing over time. However, one could again hypothesize that the ability to abstain actually decreased but this was offset by an increase in the number of quit attempts. Fortunately, the NHIS data set also reports the annual incidence of quit attempts in the same samples (Figure 2, bottom panel). Visual inspection suggests no increase in quit attempts over this period; thus, this alternate hypothesis appears unlikely.

Figure 2.

Upper Panel: Quit Ratio (former smokers/eversmokers) from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHISs)

Lower Panel: Percent of current smokers who made an attempt to stop smoking in the last 12 months from NHISs.

The other published study examined hardening among treatment seekers. The same authors of the prior analyses of past behavioral treatment studies conducted a second analysis (Irvin et al., 2003) that examined studies of medications for smoking cessation. Placebo quit rates decreased from an estimated 32% in 1985 to 24% in 2000. Active treatment quit rates also decreased – from an estimated 67% to 45% for gum and 65% to 27% for patch.

In summary, just as with the earlier reviews, the two new studies and the author's analysis again suggest hardening is not occurring in the general population but may be occurring amongst treatment seekers. Of course, there are alternate explanations for the above outcomes. The population studies did not directly measure success on a given attempt; rather they measured the proportion of abstinent smokers among smokers who made one or more quit attempts in the last year. In prior surveys, among those who attempted to quit in the last year, half or more have tried to quit more than once (Gilpin and Pierce, 1994); thus, it could be that the success on a given attempt is decreasing but this is offset by an increase in multiple attempts to quit in a given year.

The results of the treatment study that found evidence of hardening also has alternate explanations. For example, perhaps the decline in quit rates is not because of hardening but rather, because over time, new treatments are tried in less appropriate, more resistant, or less compliant samples (i.e., selection bias). Or perhaps early on only positive trials are accepted by journals (i.e., publication bias) (Etter et al., 2007).

7. Is Nicotine Dependence Among Remaining Smokers Increasing Over Time?

7.1. Search for Studies

To locate studies focusing on dependence, the author noted those articles in the above searches that had the terms “dependen*’” and “addict*” in the abstract. Among the 887 articles, 22 seemed appropriate but only 5 were included.

7.2. Changes in Nicotine Dependence in Population-Based Samples

Few surveys in the search used formal measures of nicotine dependence such as the Fagerstom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (Piper et al., 2006). The most common proxy measure for dependence was cigs/day. In the prior reviews and in five new studies, with one exception (John et al., 2005), cigs/day either remained the same over time or decreased in population-based samples (Al-Delaimy et al., 2007; O'Connor et al., 2006; Jeon et al., 2008; Goodwin et al., 2009; Celebucki and Brawarsky, 2003; Hyland and Cummings, 2003), suggesting dependence is not increasing over time. However, in many countries, cigs/day is decreasing due to non-dependence pressures such as taxation, work and home restrictions, and stigmatization (Warner, 2006). Thus, some have argued that cigs/day is no longer an adequate proxy for dependence (Hughes, 2001b).

Another proxy is the time-to-first cigarette (TTFC) after awakening (Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence Phenotype Workgroup et al., 2007). Although correlated with cigs/day, it appears TTFC predicts inability to quit and other dependence outcomes independent of cigs/day (Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence Phenotype Workgroup et al., 2007). Three studies cited in the prior review examined changes in TTFC. Among California, U.S.A. smokers, the proportion who smoked within 30 min of arising did not change between 1990 and 1999 (Burns et al., 2003). Among Massachusetts, U.S.A. smokers, there was a small non-significant increase in those smoking within 30 minutes upon arising from 50% in 1994 to 54% in 1999 (Celebucki and Brawarsky, 2003). Finally, the Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation was a large policy trial that formed a sample that was similar to a population-based sample (Hyland and Cummings, 2003). In this trial, the prevalence of smoking early upon awakening between 1988 and 1993 surveys did not change. A population-based survey conducted in Germany in the mid 1990s when few tobacco control efforts occurred, also did not find TTFC decreased (John et al., 2005).

Two population-based studies examined DSM-defined dependence, not across surveys at different times, but across birth cohorts. One examined the incidence of lifetime nicotine dependence among ever-daily smokers across four birth cohorts in the Tobacco Use Supplement to the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey (Breslau et al., 2001). Nicotine dependence increased in an orderly fashion from older cohorts (50% in those 45-54 years old at the time of the interview) to younger cohorts (85% in those 15-24 years old at the interview), suggesting dependence is increasing over time. A similar analysis examined current nicotine dependence among ever-smokers across four cohorts of the large U.S. National Epidemiological Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (Goodwin et al., 2009). Again nicotine dependence increased among younger cohorts; i.e., 41% among those 45-55 years old vs. 54% among those 16-24 years old.

Although the above change could be due to less cessation among the more dependent smokers (i.e., leaving only the more dependent smokers), alternate explanations are possible. For example, some evidence indicates that new initiates to smoking are more likely to quickly develop nicotine dependence (Chassin et al., 2007). Also, it may be that older cohorts had more time to develop lifetime dependence; however, onset of nicotine dependence after age 25 is rare (Breslau et al., 2001). Also, the results of these two studies could be due to memory distortion or recall bias among those who began smoking many years ago vs. a few years ago (Hughes, 2001a). Finally, younger cohorts of smokers may be more open to labeling smoking a dependence than older cohorts (Hughes, 2001a).

7.3. Changes in Nicotine Dependence in Treatment Seekers

In the second literature analysis of published treatment studies described above (Irvin et al., 2003), TTFC increased but cigs/day decreased among treatment seekers. A more externally-valid analysis of smokers calling to the New Zealand quitline found a decrease, not an increase, in the number of heavy smokers and in the number of those who smoked within 30 min of arising (Li and Grigg, 2007).

8. Discussion

8.1 Overview

This paper suggests studies on hardening should a) distinguish between whether hardening influences quit attempts or ability to remain abstinent, b) distinguish between measures of hardening per se (e.g., ability to remain abstinent) vs. measures of presumed causes of hardening (e.g., dependence), c) examine the ability to remain abstinent due to dependence, and d) examine hardening in both treatment seekers and the general population of smokers. The review of existing data concludes hardening appears to be more likely among treatment seekers than non-treatment seekers, but further tests of this are needed.

8.2 Changes in Ability to Quit

The current analysis focused on one definition of hardening; i.e., the inability to remain abstinent after a quit attempt. The author was able to locate two new studies plus add his own analysis. The results of the newer studies were similar to that of the prior review (National Cancer Institute, 2003; Warner and Burns, 2003). Overall 4/4 of the population based surveys/analyses did not find decreased ability to quit whereas 2/2 treatment-seeker analyses did find this. Although this suggests the ability to quit smoking on a given attempt is decreasing in treatment seekers but not in the general population of smokers, the number of data sets examined is small, and all of the analyses had methodological limitations. In addition, almost all these studies used data collected prior to 2000 when hardening may have been less evident. Also, many used a small range of time to examining hardening (e.g., ≤10 years). Finally, all but one of the studies was of U.S. smokers. Several other countries such as Sweden and the United Kingdom have had large declines in smoking (Bogdanovica et al., 2011) and, thus, could provide tests of hardening.

8.3. Changes in Dependence

Across several serial cross-sectional surveys, cigs/day did not increase; however, the effect of tobacco control activities on tobacco consumption may be causing consumption measures of dependence to be less valid measures of nicotine dependence (Hughes, 2001b). Two studies using DSM measures (which do not include consumption) (Breslau et al., 2001; Goodwin et al., 2009) suggested dependence is increasing over time, but these used retrospective birth cohort analysis and alternative explanations for their results are possible. Among treatment seekers, one new study of a quitline found TTFC and cigs/day were not increasing over time (Li and Grigg, 2007), but a second meta-analysis of smoking RCTs found TTFC was increasing but cigs/day was decreasing (Irvin et al., 2003). In addition, although not reviewed above, two studies have tested the hypotheses that, if hardening is occurring, remaining smokers in countries with low prevalences of smoking should be more dependent than smokers in countries with high prevalences. Both found this was the case when the Fagerstrom measure of dependence (which includes both consumption and non-consumption indices of dependence) was used (Fagerstrom et al., 1996; Fagerstrom and Furgerg, 2008).

In summary, one could conclude that nicotine dependence, when indexed by non-consumption measures is not increasing over time. Again, given the small number of data sets examined and the limitations of retrospective cohort analyses, a perhaps more appropriate conclusion is that an adequate test of increasing dependence has not been done.

8.4. Future Studies

To better examine changes in the ability to quit in the general population, future national or state surveys could be modified to better assess hardening. Such surveys should include measures both of quit attempts and success on each given quit attempt. Since recall of quit attempts can be poor (Gilpin and Pierce, 1994), focus on the most recent quit attempt would be preferred; however, very recent quit attempts (e.g., within the last 3 months) should be ignored since it is unclear whether those abstinent are likely to remain abstinent (Hughes et al., 2004). Finally, about a quarter of quit attempts use treatment (Shiffman et al., 2008). Since treatment is associated with quitting success, it should be a covariate in analyses. It may be that quitting is becoming more difficult but this has been offset by increased use of treatment.

Given that tobacco control activities have a significant effect on tobacco consumption (Warner, 2006), measures of dependence that do not rely on consumption should be preferred in future studies. Although TTFC is often used, given this is but a single question, it should be supplemented by other multi-item non-consumption dependence measures (Piper et al., 2006). Some existing national annual surveys (e.g., the U.S. National Household Survey on Drug Use and Health and U.S. National Health Interview Survey) already include such measures, but they do not do so consistently across annual surveys. Several recently developed, more-validated, multi-item measures of nicotine dependence (Piper et al., 2006) include the Cigarette Dependence Scale (Etter et al., 2009), the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (Wellman et al., 2005), the Kano Test for Social Nicotine Dependence (Otani et al., 2009), the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (Shiffman et al., 2004), the Smoking Motives Questionnaire (Hudmon et al., 2003), the Tobacco Dependence Screening (Kawakami et al., 1999), and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (Smith et al., 2010).

To better examine test hardening in treatment seekers, many North American quitlines have begun to use a common measure of the ability to remain abstinent in their evaluations (www.naqc.org). These evaluations could provide several independent, externally valid tests of hardening among treatment seekers. Dependence is often correlated with other characteristics associated with ability to stop smoking; e.g., psychiatric comorbidity. Thus, to truly examine nicotine dependence, these associated features may need to be used as covariates in analyses. Detection of hardening may require analyses of large ranges of years; i.e., more than 15 years, in part, because some changes could be non-linear over time. For example, hardening may be especially prominent during those years when the prevalence of smoking is not declining. Finally, since hardening may vary across subpopulations of smokers, future studies, both of inability to quit and severity of dependence, should look specifically at subgroups that have very low rates of smoking; e.g., those with advanced degrees and women of certain ethnicities.

8.5. General Discussion

This review has defined “hardening” as the phenomena of remaining smokers being less likely to remain abstinent after a quit attempt. The review focused on whether smokers who tried to quit were successful. It is tempting to equate failure to quit with “difficulty quitting;” however, no studies have reported whether self-reported difficulty quitting has changed over time. It is plausible that remaining smokers could find quitting more difficult but this is counterbalanced by greater motivation to quit due to public health efforts.

Although this review often refers to “remaining smokers;” in fact, the population of adult smokers is influenced by those who become smokers and those who die from smoking. Thus, another possibility is that, in fact, hardening among remaining smokers is occurring but is being offset by the fact that the new smokers who enter the population are more easily motivated to quit or are less dependent than prior cohorts (Warner and Burns, 2003; National Cancer Institute, 2003; Chaiton et al., 2008). However, new cohorts of initiates to smoking appear to be more dependent, not less dependent, than earlier cohorts (Chassin et al., 2007). On the other hand, smokers who do not quit are more likely to die from smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1990) and because such smokers are not in the analyses, this selection bias could decrease the ability to detect hardening.

A third possible explanation is that the effect of tobacco control activities is greater in more dependent smokers than in less dependent smokers (Warner and Burns, 2003; National Cancer Institute, 2003), offsetting the hardening selection bias. For example, price increases and worksite restrictions may have a greater impact on heavier smokers which is just the subpopulation that the hardening hypothesis states will be less likely to quit (National Cancer Institute, 2003).

Tobacco control efforts have produced a dramatic fall in the prevalence of smoking in the U.S. (U.S. Dept Health and Human Services, 1989). However, in the last decade, that decrease has slowed, in large part due to lack of progress in adult cessation (Mendez and Warner, 2004). How much of this lack of progress is due to a failure to adequately motivate smokers to stop or is because remaining smokers are less successful in quitting is unclear. Both possibilities are face-valid. For example, perhaps we have not learned how to adequately motivate poor smokers, such as those with comorbidity. Or it could be that there are dependent smokers that are relatively resistant to motivational messages and are unlikely to quit unless they receive treatment (Hughes, 2008).

In summary, determination of whether remaining smokers are less likely to quit due to increased nicotine dependence is important to help allocate resources. Although many have worried that such a demonstration would lead to a re-allocation of public health resources to treatment and thereby decrease current public health activities (Warner and Burns, 2003), this is not a necessary outcome. Given that smoking is the greatest risk for early death of an individual (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004), treatment of smoking can be viewed as a clinical, not public health activity, and thus its funding should come from clinical funds (Hughes, 2008). In fact, over time, public and private insurance plans have increased funding for smoking cessation treatments (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Demonstration that remaining smokers are less likely to quit could be a strong argument that, just like some with alcohol or drug dependence, some smokers are unlikely to quit with simple public health efforts and, thus, clinical funds for treatment are appropriate.

Finally, given that almost all interventions vary in their effectiveness across subpopulations, given the lack of progress in increasing cessation among current smokers, and given the apparent logic of hardening, the paucity of empirical studies on hardening is surprising. Inclusion of well-crafted questions in new surveys could provide more definitive answers with only moderate costs or efforts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Delaimy W, Pierce J, Messer K, White M, Trinidad D, Gilpin E. The California Tobacco Control Program's effect on adult smokers: (2) daily cigarette consumption levels. Tob. Control. 2007;16:91–95. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanovica I, Godfrey F, McNeill A, Britton J. Smoking prevalence in the European Union: a comparison of national and transnational prevalence survey methods and results. Tob. Control. 2011 doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036103. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Nicotine dependence in the United States: prevalence, trends and smoking persistence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2001;58:810–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DM, Major JM, Anderson CM, Vaughn JW. Those Who Continue To Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions? Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2003. Changes in cross-sectional measures of cessation, numbers of cigarettes smoked per day, and time to first cigarette-California and national data. pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Celebucki C, Brawarsky P. Those Who Continue to Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change our Interventions? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2003. Hardening of the target: Evidence from Massachusetts. pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention State Medicaid coverage for tobacco-dependence treatments - United States, 2006. MMWR. 2008;57:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton M, Cohen J, Frank J. Population health and the hardcore smoker: Geoffrey Rose revisited. J. Public Health Policy. 2008;29:307–318. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson C, Morgan-Lopez A, Sherman S. “Deviance proneness” and adolescent smoking 1980 versus 2001: has there been a “hardening” of adolescent smoking? J. Applied Dev. Psychol. 2007;28:264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Coambs RB, Kozlowski LT, Ferrence RG. The future of tobacco use and smoking research. In: Ney T, Gale A, editors. Smoking and Human Behavior. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; New York: 1989. pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Cohen J, Chaiton M, Ip D, McDonald P, Ferrence R. “Hardcore” definitions and their application to a population-based sample of smokers. Nic. Tob. Res. 2010;12:860–864. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Burri M, Stapleton J. The impact of pharmaceutical company funding on results of randomized trials of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2007;102:815–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter J, LeHouezec J, Huguelet P, Etter M. Testing the Cigarette Dependence Scale in 4 samples of daily smokers: psychiatric clinics, smoking cessation clinics, a smoking cessation website and in the general population. Addict. Behav. 2009;34:446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom K, Furgerg H. A comparison of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and smoking prevalence across countries. Addiction. 2008;103:841–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Kunze M, Schoberberger R, Breslau N, Hughes JR, Hurt RD, Puska P, Ramstrom L, Zatonski W. Nicotine dependence versus smoking prevalence: comparisons among countries and categories of smokers. Tob. Control. 1996;5:52–56. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin E, Pierce JP. Measuring smoking cessation: problems with recall in the 1990 California Tobacco Survey. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:613–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R, Keyes K, Hasin D. Changes in cigarette use and nicotine dependence in the United States: evidence from the 2001-2002 wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:1471–1477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Stead LF, Gupta P. Tobacco addiction. Lancet. 2008;371:2027–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60871-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon K, Marks JL, Pomerleau CS, Bolt DM, Brigham J, Swan GE. A multidimensional model for characterizing tobacco dependence. Nic. Tob. Res. 2003;5:655–664. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Brandon TH. A softer view of hardening. Nic. Tob. Res. 2003;5:961–962. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. The future of smoking cessation therapy in the United States. Addiction. 1996;91:1797–1802. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911217974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Distinguishing nicotine dependence from smoking: why it matters to tobacco control and psychiatry. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2001a;58:817–818. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Those Who Continue to Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions? Smoking and Tobacco Monograph No. 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2001b. The evidence for hardening. Is the target hardening? [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Niaura R, Ossip-Klein D, Richmond R, Swan G. Measures of abstinence from tobacco in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. Tobacco treatment specialists: a new profession. J, Smok, Cessat. 2008;2(Suppl.):2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Callas P. Definition of a quit attempt: a replication test. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Cummings K. Those Who Continue to Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions? Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2003. Changes in measures of nicotine dependence using cross-sectional and longitudinal data from COMMIT. pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Brandon TH. The increasing recalcitrance of smokers in clinical trials. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2000;2:79–84. doi: 10.1080/14622200050011330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Hendricks PS, Brandon TH. The increasing recalcitrance of smokers in clinical trials II: pharmacotherapy trials. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:27–35. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000070534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H, Hahm F, Lee H, Hong J, Bae J, Park J, Kim J, Bae A, Park J, Chung E, Shin J, Choi Y, Chung I, Lee H, Cho M. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of 12-month tobacco dependence among ever-smokers in South Korea, during 1984-2001. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2008;23:207–212. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Meyer C, Rumpf H, Schumann A, Hapke U. Consistency or change in nicotine dependence according to the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence over three years in a population sample. J. Addict. Dis. 2005;24:85–100. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami N, Takatsuka N, Inaba S, Shimizu H. Development of a screening questionnaire for tobacco/nicotine dependence according to ICD-10, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV. Addict. Behav. 1999;24:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Fleming L, Arheart K, LeBlanc W, Caban A, Chung-Bridges K, Christ S, McCollister K, Pitman T. Smoking rate trends in U.S. occupational groups: the 1987 to 2004 National Health Interview Survey. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007;49:75–81. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31802ec68c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Grigg M. Evidence of declining nicotine dependency in new callers to a national quitline. J. Smok. Cessat. 2007;2:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mckay J, Eriksen M, Shafey O. The Tobacco Atlas. American Cancer Society; Altanta: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D, Warner K. Adult cigarette smoking prevalence: declining as expected (not as desired). Am. J. Public Health. 2004;94:251–252. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer K, Pierce J, Zhu S, Hartman A, Al-Delaimy W, Trinidad D, Gilpin E. The California Tobacco Control Program's effect on adult smokers: smoking cessation. Tob. Control. 2007;16:85–90. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MMWR Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation - United States, 2008. MMWR. 2009;58:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray R, Bauld L, Hackshaw L, McNeill A. Improving access to smoking cessation services for disadvantaged groups: a systematic review. J. Public Health. 2009;31:258–277. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute . Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 2003. Those Who Continue To Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions? [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor R, Giovino G, Kozlowski L, Shiffman S, Hyland A, Bernert J, Caraballo R, Cummings K. Changes in nicotine intake and cigarette use over time in two nationally representative cross-sectional samples of smokers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006;164:750–759. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani T, Yoshii C, Kano M, Kitada M, Inagaki K, Kurioka N, Isomura T, Hara M, Okubo Y, Koyama H. Validity and reliability of Kano Test for social nicotine dependence. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009;19:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Baker TB. Assessing tobacco dependence: a guide to measure evaluation and selection. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2006;8:339–351. doi: 10.1080/14622200600672765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;34:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995;48:9–18. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00097-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Piper M, Bolt D, Fiore M, Wetter D, Cinciripini P, Baker T. Development of the Brief Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:489–499. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Malarcher A, Maurice E, Caraballo R. Cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence Phenotype Workgroup. Baker T, Piper M, McCarthy D, Bolt D, Smith S, Kim S-Y, Colby S, Conti D, Giovino G, Hatsukami D, Hyland A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Niaura R, Perkins K, Toll B. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007;9:S555–S570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . A Report of the US Surgeon General. Office on Smoking and Health; Rockville: 1990. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta: 2004. The Health Consequences of Smoking. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Dept Health and Human Services . A Report of the U.S. Surgeon General. U.S. Office on Smoking and Health; Washington, D.C.: 1989. Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking: 25 Years of Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE, Burns DM. Hardening and the hard-core smoker: concepts, evidence, and implications. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:37–48. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000060428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner K. Tobacco Control Policy. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman R, DiFranza J, Savageau J, Godiwala S, Friedman K, Hazelton J. Measuring adults’ loss of autonomy over nicotine use: the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2005;7:157–161. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]