Abstract

Objective To determine whether vertebroplasty is more effective than placebo for patients with pain of recent onset (≤6 weeks) or severe pain (score ≥8 on 0-10 numerical rating scale).

Design Meta-analysis of combined individual patient level data.

Setting Two multicentred randomised controlled trials of vertebroplasty; one based in Australia, the other in the United States.

Participants 209 participants (Australian trial n=78, US trial n=131) with at least one radiographically confirmed vertebral compression fracture. 57 (27%) participants had pain of recent onset (vertebroplasty n=25, placebo n=32) and 99 (47%) had severe pain at baseline (vertebroplasty n=50, placebo n=49).

Intervention Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus a placebo procedure.

Main outcome measure Scores for pain (0-10 scale) and function (modified, 23 item Roland-Morris disability questionnaire) at one month.

Results For participants with pain of recent onset, between group differences in mean change scores at one month for pain and disability were 0.1 (95% confidence interval −1.4 to 1.6) and 0.2 (−3.0 to 3.4), respectively. For participants with severe pain at baseline, between group differences for pain and disability scores at one month were 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.5) and 1.4 (−1.2 to 3.9), respectively. At one month those in the vertebroplasty group were more likely to be using opioids.

Conclusions Individual patient data meta-analysis from two blinded trials of vertebroplasty, powered for subgroup analyses, failed to show an advantage of vertebroplasty over placebo for participants with recent onset fracture or severe pain. These results do not support the hypothesis that selected subgroups would benefit from vertebroplasty.

Introduction

Two recent randomised placebo controlled trials of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures, the only published randomised trials with a placebo control, blinded treatment allocation, and blinded outcome assessment, failed to confirm the efficacy of vertebroplasty.1 2 These results have generated considerable controversy.3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Despite the negative overall findings of the two placebo controlled trials, it has been suggested that there may be subgroups of patients who would benefit from vertebroplasty, and the suitability of the procedure for some of the included trial participants has been questioned. Some commentators have maintained that vertebroplasty should only be offered to patients with acute vertebral fractures of recent onset (<6 weeks),6 11 whereas others have claimed it is more effective for those with severe pain.6 11 16

Since publication of these trials, the results from the vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II) trial, a large open label randomised trial, have also been reported.17 The participants’ mean duration of pain was slightly less than six weeks and all reported baseline scores for pain of 5 or more on a 0 to 10 visual analogue scale. Compared with usual care, vertebroplasty resulted in an additional benefit of 2.6 units on the pain scale at one month, a result that was clinically and statistically significant. However, these results may be explained by the fact that neither the participants nor the outcome assessors or investigators were blinded to treatment allocation. Empirical evidence from meta-epidemiological studies has shown that lack of blinding results in an average 25% over-estimate of relative treatment benefit.18 19

Acutely painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures generally heal quickly, as was well illustrated in the Vertos II trial in which more than 50% of those who initially qualified for the study were deemed ineligible owing to spontaneous resolution of pain.17 This implies that most people would be unlikely to benefit from early invasive intervention, and it would need to be postulated that a subgroup with more persistent symptoms would derive benefit.

In contrast with what has been claimed both placebo controlled trials included participants with recent onset fractures (<6 weeks)—one third in the Australian study and about 20% in the US trial. Although neither trial found evidence that duration of symptoms was a treatment effect modifier, individually they lacked sufficient power to draw definitive conclusions from subgroup analyses. They also lacked sufficient power to investigate smaller benefits in pain or function than those originally hypothesised. By combining the data from both trials, the larger overall sample size provides an opportunity to undertake select subgroup analyses and to investigate smaller benefits in pain or function.

We combined the individual patient level data from both placebo controlled blinded trials to determine whether vertebroplasty is more effective than placebo for patients with fracture pain of recent onset (≤6 weeks) compared with pain of longer duration, and whether vertebroplasty is more effective for patients with severe pain (≥8 on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale). Using the combined data we also investigated whether smaller benefits in pain or function were detectable.

In a post specified analysis, the US trial found a trend towards a higher rate of participants with a clinically meaningful improvement in pain at one month in the vertebroplasty group, although the treatment groups did not differ for physical disability related to back pain.2 With the combined trials we had sufficient power to test this trend. Using the whole dataset we also carried out responders’ analyses based on a 3 unit improvement in pain scores, a 3 unit improvement in score on the modified, 23 item Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, and 30% improvement in each of the pain and disability outcomes.

Methods

The methods and results for both studies are presented in detail elsewhere.1 2 20 21 Up to the one month outcome both trials were done according to similar but not identical protocols for entry criteria, randomisation, and how the treatments in the treatment and control arms were administered.

The Australian study was a multicentre, randomised controlled trial in which participants with one or two painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures of less than 12 months’ duration and unhealed, as confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, were randomly assigned to vertebroplasty or to a sham procedure.1 20 Participants were stratified according to treatment centre, sex, and duration of symptoms (<6 weeks or ≥6 weeks) and outcomes were assessed at one week and one, three, and six months. The US trial was also a multicentre, randomised controlled trial in which participants with one to three painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures of less than 12 months’ duration and unhealed were randomly assigned to vertebroplasty or to a sham procedure.2 21 Participants were stratified according to treatment centre, and outcomes were assessed at three days, two weeks, and one and three months. Both trials blinded participants, investigators, and outcome assessors. The Australian trial was a parallel group design, whereas in the US trial participants were allowed to cross over to the other study group after one month or later if pain relief was not adequate.

The sham procedures in each trial attempted to simulate vertebroplasty as much as possible. In both, the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and periosteum of the pedicles were infiltrated with local anaesthetic. The Australian trial inserted a needle to rest on the lamina of the vertebral body, and after removal of the central sharp stylet the vertebral body was gently tapped with a blunt stylet. The US trial did not insert a needle but used verbal and physical clues such as pressure on the patient’s back to simulate the procedure. Both trials prepared the medical cement (polymethylmethacrylate) so that its smell permeated the room.

The primary outcome for the Australian trial was pain, measured on an 11 point numerical rating scale,1 20 and for the US trial was disability, measured by the modified, 23 item Roland-Morris disability questionnaire.2 21 Pain outcomes were assessed slightly differently in each trial. Participants in the Australian trial were asked to rate their average pain over the previous week, whereas participants in the US trial were asked to rate their average pain over the previous 24 hours. Based on empirical data which show that asking about the previous week or previous 24 hours yields similar results,22 we considered the measures of pain to be comparable for the purpose of this meta-analysis.

Disability was assessed in both trials using the modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, and generic health status was assessed using the EQ-5D. These two measures were included in the Australian trial several months after enrolment began and therefore were not available for all participants at the earlier time points. Although the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire was originally developed for use in patients with non-specific low back pain,23 the modified version has been shown to be valid and responsive for studying vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures.24

Outcome measures and time points

Common time points for data collection in both trials were baseline, one month, and three months. Crossover was allowed in the US trial after one month and, as 35 participants crossed over after this time, for the current analyses we have included follow-up to one month only. For both trials we obtained individual patient data for outcomes up to one month. Baseline data included study centre, race, sex, age in years, pain score measured on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale, duration of pain in weeks, scores on the modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, and EQ-5D scores based on the US value sets.

Outcomes between baseline and one month were not measured at identical times in each study. In the Australian trial, assessments of pain, disability, and generic health status (EQ-5D) were carried out at one week, whereas in the US trial pain and disability were assessed at one day, three days, and two weeks and no EQ-5D assessments were made between baseline and one month.

We compared all outcome measurements between groups at baseline and one month. For the intermediate time points at three days, one week, and two weeks, we carried out three separate comparisons: the outcomes at one week for the Australian trial with the outcomes at three days for the US trial, the outcomes at one week for the Australian trial with a score computed as the mean of the scores at three days and two weeks for the US trial, and the outcomes at one week for the Australian trial with the outcomes at two weeks for the US trial. The results were comparable for each of the intermediate time point analyses and we therefore only present the third intermediate comparison (see web extra table 1 for the first and second intermediate comparisons).

For the primary analysis, a priori subgroups were participants with pain of recent onset (≤6 weeks or >6 weeks) and participants with severe pain scores at baseline (≥8 or <8). For the responders’ analyses we used the combined dataset to consider the proportion showing at least a 3 unit improvement in pain score from baseline, the proportion showing at least a 3 unit improvement in disability score from baseline (modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire), the proportion showing a 30% improvement in pain score, and the proportion showing a 30% improvement in disability score. To assess whether these results could be subject to confounding we also compared the groups for self reported opioid use at one month.

Sample size calculations

The original sample size calculations for the Australian trial indicated that 24 participants would be needed in each treatment group to show a 2.5 unit advantage in pain scores, assuming a standard deviation of 3.0, a significance level of 5%, and 80% power. The observed standard deviation for pain was about 2.0 rather than 3.0 as assumed for study planning and therefore the power calculations are conservative. From the combined trials 25 participants in the control group and 32 in the vertebroplasty group had recent onset pain and 50 in the control group and 49 in the vertebroplasty group had severe pain at baseline. Thus the combined data provided greater than 80% power to assess whether vertebroplasty had a 2.5 unit advantage over control for patients with acute fractures or severe pain. The combined data would also have 53% power to detect a 3 unit difference (assuming a standard deviation of 5.5) in disability scores for the subgroup with recent onset pain and 77% power for the subgroup with severe pain at baseline.

The accepted minimum clinically important difference for pain is 1.5 units on an 11 point scale.25 26 With 209 participants we had over 94% power to detect a 1.5 unit advantage for vertebroplasty over control, assuming a standard deviation of 3.0 for each group. For the modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire the accepted minimum clinically important difference is 2 or 3 points on a 0 to 23 scale,24 and with 209 participants we had 88% power to show a 3 point advantage for the vertebroplasty group, assuming a standard deviation of 6.7.

Statistical analysis

To assess baseline differences between the Australian and US trial populations we used χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables.

We calculated the mean change scores for each group for the main outcomes and a priori subgroups at each time point. Analysis of covariance was used to generate estimates of treatment effect on the outcome measures of pain using a numerical rating scale, the modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, and EQ-5D. As study centre was nested within trial, we adjusted for study centre as a fixed effect to account for differences between both study centre and trial. The fixed main effects were intervention group, the relevant primary outcome, subgroup variables, and interactions as appropriate. Age and sex were not included as evidence is lacking that these influence outcome.

We compared the proportions of participants in each group who showed at least a 3 unit improvement in pain or disability scores or a 30% improvement in pain or disability scores from baseline using relative risks estimated from a generalised linear binomial model with a log link and robust error variance to account for the clustering of trial site.27 A relative risk greater than 1 indicates that a higher proportion of participants in the vertebroplasty group achieved at least a 3.0 unit or 30% improvement in pain or disability scores. We used logistic regression with adjustment for baseline opioid use and study centre to compare self reported opioid use at one month for each treatment group; a relative risk greater than 1 indicates that a higher proportion of participants in the vertebroplasty group were using opioids one month after the procedure.

Results

Data on 209 participants (Australian trial n=78, US trial n=131) were available for analysis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants in each trial. The average duration of pain was shorter for participants in the Australian trial, with a higher proportion reporting pain of recent onset (P<0.001). Self reported use of opioids at baseline was also higher for participants in the Australian trial (P=0.001). All other measures were comparable between trials. The baseline characteristics of combined participants by treatment group (table 1) and of the subgroups by treatment group (table 2) were also similar.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in each trial and each treatment group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Australian trial (n=78) | US trial (n=131) | Combined treatment groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebroplasty (n=106) | Placebo (n=103) | |||

| Australian trial | — | — | 38 (36) | 40 (39) |

| US trial | — | — | 68 (64) | 63 (61) |

| Women | 62 (79) | 99 (76) | 84 (79) | 77 (75) |

| Severe pain at baseline (score ≥8) | 38 (49) | 61 (47) | 50 (47) | 49 (48) |

| Recent onset pain (≤6 weeks) | 31 (40) | 26 (20) | 25 (24) | 32 (31) |

| Self reported opioid use | 64 (82) | 78 (60) | 72 (68) | 70 (68) |

| Mean (SD) age at baseline (years) | 76.6 (12.1) | 73.8 (9.4) | 73.7 (11.2) | 76.1 (9.8) |

| Mean (SD) pain* | 7.3 (2.2) | 7.0 (1.9) | 7.1 (2.0) | 7.1 (2.0) |

| Mean (SD) pain duration (weeks) | 11.7 (11.1) | 22.5 (16.3) | 17.9 (15.1) | 19.1 (15.9) |

| Mean (SD) RMDQ score† | 17.3 (2.8), n=59 | 17.1 (4.0), n=131 | 16.8 (3.5), n=98 | 17.4 (3.8), n=92 |

| Mean (SD) EQ-5D score† (US value sets) | 0.50 (0.23), n=59 | 0.55 (0.20), n=130 | 0.55 (0.19), n=98 | 0.52 (0.23), n=91 |

RMDQ=modified, 23 item Roland-Morris disability questionnaire.

*In Australian trial pain was average overall pain during past week; in US trial pain was average pain intensity during past 24 hours.

†Outcomes added to Australian trial several months after enrolment began.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants by subgroup and each treatment group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Baseline pain score | Duration of pain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate (<8) | Severe (≥8) | ≤6 weeks | >6 weeks | ||||||

| Vertebroplasty (n=56) | Placebo (n=54) | Vertebroplasty (n=50) | Placebo (n=49) | Vertebroplasty (n=25) | Placebo (n=32) | Vertebroplasty (n=81) | Placebo (n=71) | ||

| Women | 45 (80.4) | 46 (85.2) | 39 (78.0) | 31 (63.3) | 17 (68.0) | 21 (65.6) | 67 (82.7) | 56 (78.9) | |

| Pain duration or baseline pain score | 9 (16.1)* | 15 (27.8)* | 16 (32.0)* | 17 (34.7)* | 16 (64.0)† | 17 (53.1)† | 34 (42.0)† | 42 (59.2)† | |

| Self reported opioid use | 33 (58.9) | 32 (59.3) | 39 (78.0) | 38 (77.6) | 23 (92.0) | 28 (87.5) | 49 (60.5) | 42 (59.2) | |

| Mean (SD) age at baseline (years) | 72.7 (12.7) | 75.9 (9.7) | 74.8 (9.3) | 76.3 (10.0) | 79.6 (4.9) | 78.0 (9.2) | 71.8 (12.0) | 75.2 (10.0) | |

| Mean (SD) duration of pain (weeks) | 18.8 (14.9) | 19.1 (15.2) | 16.8 (15.4) | 19.1 (16.7) | 3.4 (1.7) | 3.4 (1.8) | 22.3 (14.6) | 26.2 (14.2) | |

| Mean (SD) pain‡ | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.3) | 8.8 (0.9) | 8.9 (0.9) | 7.7 (2.2) | 7.4 (2.2) | 6.9 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.9) | |

| Mean (SD) RMDQ score§ | 16.4 (4.0), n=52 | 16.7 (3.7), n=51 | 17.3 (2.8), n=46 | 18.4 (3.6), n=41 | 17.3 (2.5), n=24 | 18.0 (3.5), n=29 | 16.7 (3.8), n=74 | 17.2 (3.9), n=63 | |

| Mean (SD) EQ-5D score (US value set)§ | 0.60 (0.16), n=52 | 0.60 (0.19), n=50 | 0.48 (0.20), n=46 | 0.43 (0.23), n=41 | 0.49 (0.23), n=24 | 0.46 (0.26), n=29 | 0.57 (0.17), n=74 | 0.55 (0.20), n=62 | |

RMDQ=modified, 23 item Roland-Morris disability questionnaire.

*Pain duration ≤6 weeks.

†Baseline pain score ≥8.

‡In Australian trial pain was average overall pain during past week; in US trial pain was average pain intensity during past 24 hours.

§RMDQ and EQ-5D outcomes were added to Australian trial several months after enrolment began.

Table 3 shows the mean change scores from baseline and adjusted between group differences in pain and disability scores at two weeks/one week and one month and the EQ-5D at one month. Both groups did not differ significantly for pain, disability, or health status at any time point. The adjusted between group differences for pain and disability scores were all below the minimum clinically important difference for each respective measure and below the more stringent 1.5 units for pain and 2 points for disability.

Table 3.

Mean change scores (SD) from baseline and adjusted between group differences for main outcomes and for each subgroup at follow-up points

| Outcome | Mean (SD) change* at 2weeks/1 week | Adjusted between group difference† (95% CI) | Mean (SD) change* at 1 month | Adjusted between group difference† (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebroplasty | Placebo | Vertebroplasty | Placebo | |||

| Overall pain | 2.2 (2.8), n=102 | 2.5 (3.0), n=99 | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.6) | 2.8 (3.0), n=102 | 2.2 (3.2), n=99 | 0.6 (−0.2 to 1.4) |

| RMDQ | 3.2 (5.1), n=94 | 4.4 (5.2), n=88 | −0.8 (−2.2 to 0.7) | 4.1 (5.9), n=94 | 3.9 (6.1, n=89 | 0.8 (−0.9 to 2.4) |

| EQ-5D (US value set) | — | — | — | 0.12 (0.19), n=94 | 0.11 (0.23), n=88 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) |

| Subgroups | ||||||

| Pain ≤6 weeks: | ||||||

| Overall pain | 2.4 (2.9), n=25 | 2.9 (3.7), n=31 | −0.7 (−2.1 to 0.7) | 3.1 (3.3), n=25 | 2.8 (4.0), n=31 | 0.1 (−1.4 to 1.6) |

| RMDQ | 2.3 (4.5), n=24 | 4.5 (5.4), n=28 | −1.6 (−4.3 to 1.0) | 3.8 (5.9), n=24 | 4.4 (5.4), n=28 | 0.2 (−3.0 to 3.4) |

| EQ-5D (US value set) | — | — | — | 0.15 (0.24), n=24 | 0.15 (0.30), n=28 | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.13) |

| Pain >6 weeks: | ||||||

| Overall pain | 2.1 (2.7), n=77 | 2.3 (2.3), n=68 | 0.1 (−0.8 to 0.9) | 2.7 (2.9), n=77 | 2.0 (2.7), n=68 | 0.8 (−0.1 to 1.8) |

| RMDQ | 3.5 (5.3), n=70 | 4.4 (5.2), n=60 | −0.4 (−2.1 to 1.3) | 4.2 (6.0), n=70 | 3.7 (6.3), n=61 | 1.0 (−1.0, to 3.0) |

| EQ-5D (US value set) | — | — | — | 0.11 (0.18), n=70 | 0.09 (0.20), n=60 | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.09) |

| Baseline pain score ≥8: | ||||||

| Overall pain | 3.0 (2.6), n=47 | 3.7 (3.0), n=48 | −0.8 (−1.8 to 0.3) | 3.9 (2.9), n=46 | 3.5 (3.2), n=47 | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.5) |

| RMDQ | 3.0 (4.8), n=43 | 4.5 (5.5), n=40 | −1.0 (−3.2 to 1.2) | 4.1 (5.9), n=42 | 3.3 (5.6), n=40 | 1.4 (−1.2 to 3.9) |

| EQ-5D (US value set) | — | — | — | 0.16 (0.21), n=42 | 0.15 (0.25), n=40 | 0.05 (−0.03 to 0.12) |

| Baseline pain score <8: | ||||||

| Overall pain | 1.5 (2.7), n=55 | 1.3 (2.4), n=51 | 0.4 (−0.7 to 1.4) | 1.9 (2.8), n=56 | 1.1 (2.8), n=52 | 0.8 (−0.3 to 1.9) |

| RMDQ | 3.3 (5.4), n=51 | 4.3 (5.0), n=48 | −0.6 (−2.5 to 1.4) | 4.2 (6.0), n=52 | 4.4 (6.4), n=49 | 0.2 (−2.1 to 2.5) |

| EQ-5D (US value set) | — | — | — | 0.09 (0.17), n=55 | 0.07 (0.21), n=48 | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.09) |

RMDQ=modified, 23 item Roland-Morris disability questionnaire.

*Positive values for mean change indicate improvements from baseline.

†Estimates of mean change from regression models adjusting for trial; positive values for between group differences favour vertebroplasty group, negative values favour placebo group.

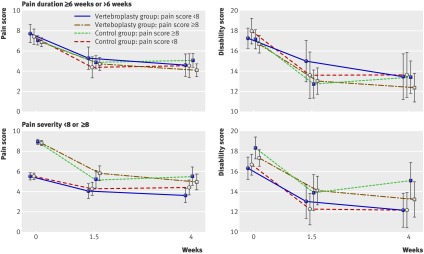

Outcomes did not differ between the groups for participants with pain duration recent onset or longer (>6 weeks) or for participants with severe pain at baseline pain or mild to moderate pain (score <8) at either the two weeks/one week or one month time points (table 3 and figure). The adjusted mean between group differences were all below the minimum clinically important differences for pain and disability scores.

Mean (95% confidence intervals) scores for pain and disability (modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire) at baseline, intermediate (two weeks/one week), and one month time points by treatment group for participants with recent onset pain (≤6 weeks) or pain of longer duration and for participants with mild to moderate or severe pain at baseline

The vertebroplasty and placebo groups did not differ in the proportions showing a 3 unit improvement in pain score or a 3 point improvement in disability score at either the two weeks/one week or one month time points (table 4). At one month only was the trend towards a higher proportion of the vertebroplasty group achieving at least 30% improvement in pain scores (relative risk 1.32, 95% confidence interval 0.98 to 1.76, P=0.07). At neither time point did the groups differ in the proportions achieving at least 30% improvement in disability scores (table 4).

Table 4.

Number (%) of participants and relative risk (95% confidence interval) for at least 3 units improvement in pain or disability score or at least 30% improvement in pain or disability score from baseline to each time point. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Improvement in outcomes from baseline | Vertebroplasty group | Placebo group | Relative risk* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | |||

| 2 weeks/1 week: | |||

| <3 units | 59 (57.8) | 56 (56.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) |

| ≥3 units | 43 (42.2) | 43 (43.4) | |

| 1 month: | |||

| <3 units | 47 (46.1) | 56 (56.6) | 1.3 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| ≥3 units | 55 (53.9) | 43 (43.4) | |

| Roland-Morris disability questionnaire† | |||

| 2 weeks/1 week: | |||

| <3 units | 53 (56.4) | 41 (46.6) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| ≥3 units | 41 (43.6) | 47 (53.4) | |

| 1 month: | |||

| <3 units | 45 (47.9) | 43 (48.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| ≥3 units | 49 (52.1) | 46 (51.7) | |

| Pain | |||

| 2 weeks/1 week: | |||

| <30% | 52 (51.0) | 52 (52.5) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| ≥30% | 50 (49.0) | 47 (47.5) | |

| 1 month: | |||

| <30% | 41 (40.0) | 54 (54.6) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8) |

| ≥30% | 61 (59.8) | 45 (45.5) | |

| Roland-Morris disability questionnaire† | |||

| 2 weeks/1 week: | |||

| <30% | 63 (61.8) | 55 (55.6) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| ≥30% | 39 (38.2) | 44 (44.4) | |

| 1 month: | |||

| <30% | 61 (59.8) | 59 (59.0) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| ≥30% | 41 (40.2) | 41 (41.0) | |

*Relative risk >1 indicates that participants in vertebroplasty group were more likely to experience greater change in outcome.

†Modified, 23 item questionnaire.

In view of the observed trend, the analyses were repeated based on a priori subgroups. At the two weeks/one week time point, patients with severe pain at baseline were more likely to show at least a 3 unit improvement or at least a 30% improvement in pain but the proportion with a clinically meaningful improvement did not differ between the groups (see web extra tables 2 and 3). The subgroups with recent onset of pain or pain of longer duration did not differ (see web extra tables 4 and 5).

At baseline, 68% of participants in each treatment group were using opioids for pain. At one month the vertebroplasty group was more likely to report opioid use (64% vertebroplasty group v 46% placebo group; P=0.018). After adjusting for baseline opioid use, patients randomised to vertebroplasty were 25% more likely to be taking opioids at one month than patients randomised to placebo (relative risk 1.25, 1.14 to 1.36, P<0.001; table 5).

Table 5.

Opioid use at baseline and one month and relative risk (95% confidence interval) for taking opioids at one month. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Opioid use at baseline | Opioid use at one month | Relative risk (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebroplasty group | Placebo group | ||

| No | 12/34 (35) | 2/33 (6) | 1.25 (1.1 to 1.4) |

| Yes | 52/69 (75) | 44/68 (65) | |

*Relative risk of opioid use at one month adjusting for opioid use at baseline; relative risk >1 indicates that participants in vertebroplasty group were more likely to be taking opioids at one month.

Discussion

In an individual patient meta-analysis from two randomised placebo controlled and blinded trials of vertebroplasty, combined data compared with the data from the individual trials did not differ significantly despite the larger sample size and increased power. In particular, no smaller benefits in pain or function were detected with vertebroplasty. Subgroup analyses also failed to show an advantage of vertebroplasty for participants with pain of recent onset (≤6 weeks) or severe pain at baseline (score ≥8). At one month the proportion of participants who had achieved improvements of at least 3 units in pain or disability (modified Roland-Morris disability questionnaire) scores did not differ significantly between the groups. The trend was towards a higher proportion in the vertebroplasty group achieving at least a 30% improvement in pain scores at one month, but this group was more likely to be using opioids at one month; this may have influenced reported pain severity in favour of vertebroplasty and also suggests that pain may have been less well controlled in the vertebroplasty group.

By combining data from the Australian1and US2 trials, which were carried out using similar protocols and outcome measures, we were able to perform subgroup analyses to assess whether vertebroplasty is indicated for patients with severe or acute pain only. This analysis provides no evidence to support the use of the procedure for these selected patient groups. Individual patient meta-analysis is the ideal method for exploring variability in effectiveness,28 yet it is rarely done.29 Challenges include acquiring and harmonising the data.30 When each group became aware of the other’s trial, efforts were made to harmonise outcome assessment in case further research questions required a combined analysis. This paper shows the benefits of this approach.

Commentaries comparing blinded and unblinded trials of vertebroplasty have focused on patient selection.3 6 10 11 12 16 The commentators suggested that the “negative” outcomes reported in the blinded trials resulted from enrolment of patients who would not generally be expected to benefit from spinal augmentation based on duration of pain, the use of magnetic resonance imaging, or other factors. The current individual patient meta-analysis, based on the only two double blind randomised placebo controlled trials published to date, refutes these arguments on duration and severity of pain by providing improved power compared with the individual trials.

Logically it is unlikely that factors predicting a more favourable outcome from vertebroplasty will be identified, as the net overall effect of vertebroplasty in both placebo controlled trials was close to zero.9 Furthermore, the only way that vertebroplasty could have a large benefit for a proportion of patients would be if the condition of a substantial proportion was made worse—a scenario that is not reflected in the available data.

In view of the recent publication of the open label Vertos II trial,17 we extended our analysis to include the specific enrolment criteria, pain of recent onset (≤6 weeks) and pain score of 5 or more, from that trial, and again were unable to show a treatment benefit for vertebroplasty (data not shown). This adds further weight to the likelihood that lack of blinding and an inadequate control group accounted for the treatment benefit observed in Vertos II.

This meta-analysis was based on the evidence from the two most rigorous trials applied to vertebroplasty to date. Although both trials infiltrated local anaesthetic under the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and periosteum in the control group, which some have argued may be an active control, a recent open cohort study using a local anaesthesia regimen identical to this failed to show any benefit of local anaesthesia into the periosteum.31 This suggests that the role of local anaesthesia in the observed improvement in the control groups of both trials was likely to be insignificant.

This meta-analysis adds to the available literature that the benefits of vertebroplasty, even in selected subgroups, are overstated. Future trials should be informed by these results and if any doubts remain about the value of vertebroplasty for specific subgroups of patients, these should be examined in randomised blinded placebo controlled trials.

What is already known on this topic

Two double blind randomised placebo controlled trials failed to confirm the efficacy of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures

Despite these findings, it has been suggested that there may be subgroups of patients who would benefit from vertebroplasty

Some commentators maintain the procedure should only be offered to patients with fractures of recent onset (<6 weeks), whereas others have claimed it is effective for those with severe pain

What this study adds

Individual patient data meta-analysis from two randomised trials of vertebroplasty failed to show an advantage of vertebroplasty over placebo for participants with recent onset fracture or severe pain

These results do not support the hypothesis that selected subgroups would benefit from vertebroplasty

Contributors: RB and DFK planned the work. MPS carried out the analysis and MPS and RB drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design of the analysis, interpretation of findings, and writing of the final manuscript. RB is the guarantor.

Funding: RHO is supported in part by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) population health career development award and RB is supported in part by an NHMRC practitioner fellowship.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: RHO is supported in part by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) population health career development award and RB is supported in part by an NHMRC practitioner fellowship; DFK has received research support from Stryker and ArthroCare and is a consultant for CareFusion, JGJ has received an honorarium for lecturing at a course sponsored by Synthes in 2010, is on the GE Healthcare comparative effectiveness advisory board, is a consultant to HealthHelp, and is cofounder and patent holder of PhysioSonics; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d3952

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Data for first and second intermediate comparisons

At least 30% improvement in pain score by baseline pain severity subgroup

At least 3 unit change in pain score by baseline pain severity subgroup

At least 30% improvement in pain score by baseline pain duration subgroup

At least 3 unit change in pain score by baseline pain duration subgroup

References

- 1.Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt C, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:557-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, Turner JA, Wilson DJ, Diamond TH, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:569-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baerlocher MO, Munk PL, Liu DM. Trials of vertebroplasty for vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2098; author reply 2099-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baerlocher MO, Munk PL, Liu DM, Tomlinson G, Badii M, Kee ST, et al. Clinical utility of vertebroplasty: need for better evidence. Radiology 2010;255:669-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baerlocher MO, Munk PL, Radvany MG, Murphy TP, Murphy KJ. Vertebroplasty, research design, and critical analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009;20:1277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bono CM, Heggeness M, Mick C, Resnick D, Watters WC, 3rd. North American Spine Society: newly released vertebroplasty randomized controlled trials: a tale of two trials. Spine J 2010;10:238-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchbinder R, Kallmes DF. Vertebroplasty: when randomized placebo-controlled trial results clash with common belief. Spine J 2010;10:241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Kallmes D. Vertebroplasty appears no better than placebo for painful osteoporotic spinal fractures, and has potential to cause harm. Med J Aust 2009;191:476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Kallmes D. Invited editorial presents an accurate summary of the results of two randomised placebo-controlled trials of vertebroplasty. Med J Aust 2010;192:338-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark W, Lyon S, Burnes J. Trials of vertebroplasty for vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark WA, Diamond TH, McNeil HP, Gonski PN, Schlaphoff GP, Rouse JC. Vertebroplasty for painful acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures: recent Medical Journal of Australia editorial is not relevant to the patient group that we treat with vertebroplasty. Med J Aust 2010;192:334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangi A, Clark WA. Have recent vertebroplasty trials changed the indications for vertebroplasty? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33:677-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kallmes D, Buchbinder R, Jarvik J, Heagerty P, Comstock B, Turner J, et al. Response to “randomized vertebroplasty trials: bad news or sham news?” AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:1809-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kallmes DF, Jarvik JG, Osborne RH, Comstock BA, Staples MP, Heagerty PJ, et al. Clinical utility of vertebroplasty: elevating the evidence. Radiology 2010;255:675-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carragee E. The vertebroplasty affair: the mysterious case of the disappearing effect size. Spine J 2010;10:191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munk PL, Liu DM, Murphy KP, Baerlocher MO. Effectiveness of vertebroplasty: a recent controversy. Can Assoc Radiol J 2009;60:170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, Jansen FH, Tielbeek AV, Blonk MC, et al. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1085-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud L, Schulz K, Jüni P, Altman D, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;36:601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psaty BM, Prentice RL. Minimizing bias in randomized trials. JAMA 2010;304:793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt CJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of vertebroplasty for treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a randomised controlled trial [ACTRN012605000079640]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray LA, Jarvik JG, Heagerty PJ, Hollingworth W, Stout L, Comstock BA, et al. INvestigational Vertebroplasty Efficacy and Safety Trial (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial of percutaneous vertebroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007;8:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khosla A, Turner JA, Jarvik JG, Gray LA, Kallmes DF. Impact of pain question modifiers on spine augmentation outcome. Radiology 2010;257:477-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 1983;8:141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trout AT, Kallmes DF, Gray LA, Goodnature BA, Everson SL, Comstock BA, et al. Evaluation of vertebroplasty with a validated outcome measure: the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:2652-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Concurrent comparison of responsiveness in pain and functional status measurements used for patients with low back pain. Spine 2004;29:E492-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. J Rheumatol 1982;9:768-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart L, Tierney J. To IPD or not to IPD? Advantages and disadvantages of systematic reviews using individual patient data. Eval Health Prof 2002;25:76-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koopman L, van der Heijden G, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Rovers M. A systematic review of analytical methods used to study subgroups in (individual patient data) meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:1002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Walraven C. Individual patient meta-analysis—rewards and challenges. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinjikji W, Comstock B, Gray L, Kallmes D. Local Anesthesia with Bupivacaine and Lidocaine for vertebral fracture trial (LABEL): a report of outcomes and comparison with the Investigational Vertebroplasty Efficacy and Safety Trial (INVEST). AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010:31:1631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data for first and second intermediate comparisons

At least 30% improvement in pain score by baseline pain severity subgroup

At least 3 unit change in pain score by baseline pain severity subgroup

At least 30% improvement in pain score by baseline pain duration subgroup

At least 3 unit change in pain score by baseline pain duration subgroup