Abstract

Background/Aim:

Both nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection are common in Egypt, and their coexistence is expected. There is controversy regarding the influence of NAFLD on chronic HCV disease progression. This study evaluates the effect of NAFLD on the severity of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) (necroinflammation and fibrosis) and assesses the relative contribution of insulin resistance syndrome to the occurrence of NAFLD in patients with chronic HCV infection.

Patients and Methods:

Untreated consecutive adults with chronic HCV infection admitted for liver biopsy were included in this study. Before liver biopsy, a questionnaire for risk factors was completed prospectively, and a blood sample was obtained for laboratory analysis.

Results:

Our study included 92 male patients. Their mean ± SD age and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level were 42 ± 7.7 years (range 20-56) and 68 ± 41.7 U/L (range 16-214), respectively. The mean insulin level and insulin resistance index were 15.6 ± 18.3 mIU/mL (range 5.1-137.4) and 5.9 ± 15.2 (range 0.9-136.2), respectively. Fifty four percent of patients had steatosis and 65% had fibrosis. In multivariate analyses, steatosis was associated with insulin resistance and fibrosis was associated with high AST level, age ≥40 years, and steatosis.

Conclusions:

Steatosis is a histopathologic feature in >50% of patients with chronic HCV infection. Insulin resistance has an important role in the pathogenesis of steatosis, which represents a significant determinant of fibrosis together with high serum AST level and older age.

Keywords: Hepatic fibrosis, hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, viral hepatitis

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide.[1] The overall prevalence of chronic HCV infection among world population is 3%.[2] According to an epidemiologic study by a team from Ain-Shams University, Egyptian Ministry of Health (MOH), and World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of HCV infection in Upper Egypt was 29.3%.[3] The severity of the disease varies widely from asymptomatic chronic infection to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Several factors can be associated with fibrosis progression, including insulin resistance (IR), type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, obesity, and age at infection.[4,5]

The worldwide (including the Middle East) prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) ranges from 10-51% depending on the population studied and the methodology used.[6] A study by Strickland and colleagues showed that bright liver by ultrasongraphic examination is present in 35.3% of 271 HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) negative subjects in Shibin El Kom, Egypt.[7] The most common risk factor for NAFLD was the presence of IR syndrome.[8,9] Hepatic steatosis is also a common histological feature of chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Various factors may be associated with steatosis in patients with chronic HCV infection, including IR, type 2 DM, dyslipidemia, and obesity.[4,5,10,11]

Both NAFLD and HCV infection are common in Egypt, and their coexistence initiates a vicious circle, i.e., they interact with each other.[12] Simple steatosis occurs in 40-70% of patients with chronic HCV infection and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) occurs in 19%.[13,14] There is some controversy with regard to the influence of NAFLD on fibrosis progression in patients with chronic HCV infection. Several studies in patients with chronic HCV infection suggested an influence of steatosis on the progression of fibrosis.[11,15] However, other studies did not show such an association.[16,17]

Therefore, we decided to conduct a prospective hospital based study of a consecutive group of patients with chronic HCV infection, taking into account confounding factors for both steatosis and fibrosis (multivariate analysis) to investigate the independent factors associated with steatosis and to determine the relationship between steatosis and each of the liver inflammation grade and fibrosis stage.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 92 consecutive untreated Egyptian male patients with chronic HCV infection who had undergone liver biopsy in Assiut University Hospital were prospectively included in this study. Patients with clinical or ultrasonographic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, any history of alcohol intake, detectable serum HBsAg, and previous administration of interferon-based antiviral therapy were excluded.

Data collection

Every patient completed a questionnaire 1-2 days before liver biopsy. The questionnaire included details on sex, age, occupation, alcohol consumption, smoking, site of residence (rural or urban), education level, any previous surgery or invasive medical procedures, any previous schistosomiasis and/or its parentral therapy, and any other potential source of infection. Measures of height, weight, waist circumference, blood pressure were taken at the same time.

Laboratory evaluation

A fasting venous blood sample was obtained 1-2 days before liver biopsy for analysis of the following parameters: prothrombin time, platelet count, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and fasting serum levels of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, and triglycerides. The upper limit of normal of ALT and AST levels in our laboratory were 41 U/L.

Definitions and calculations

Chronic HCV infection was defined by detectable serum antibody to HCV (Anti-HCV) and HCV RNA for at least 6 months. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the following equation: BMI = weight (in kilograms)/ height2 (in meters). Overweight was defined as a BMI of 25-29.9 Kg/m2. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 Kg/m2. Systemic hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg on at least 2 consecutive measures.

Impaired glucose tolerance was defined as fasting glucose level of 110-125 mg/dL. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose level of >126 mg/dL. Dyslipidemia was defined as one or more of the following: cholesterol level of ≥200 mg/dL, LDL-cholesterol level of ≥130 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol level of <27 mg/dL, or triglycerides level of ≥165 mg/dL. Insulin resistance index (IRI) was calculated according to the following equation: Insulin resistance index (Homeostasis Model [HOMA-IR]) = insulin in μIU/mL – glucose in mmol/L divided by 22.5. An upper limit of normal HOMA-IR is 1.5.[12]

The insulin resistance syndrome (IRS) was defined by the presence of ≥3 of the following criteria: entral (abdominal) obesity (waist circumference >102 cm in men or >88 cm in women), hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dL), low HDL level (<40 mg/dL in men or <50 mg/dL in women), high blood pressure (≥130/85 mm Hg), and high fasting glucose (≥110 mg/dL).[18]

Histopathological evaluation

Liver histopathology was available for all the 92 patients. Histopathologic evaluation was performed without knowledge of the patients’ clinical or laboratory data. All liver biopsies were examined by an experienced histopathologist and lesions were graded (necroinflammation) and staged (fibrosis) according to the histological activity index (HAI).[19] Steatosis was defined and graded according to Brunt and colleagues.[20] Liver sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) and with special stains, namely reticulin (for reticular fibers) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) (for glycogenated nuclei) before being examined.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected in a pre-designed form and entered in a Microsoft Excel data sheet before being statistically analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago IL, USA) for windows, version 13. Data are presented as mean ± SD (maximum-minimum) or number (percentage) as appropriate. Predictive factors for the presence of steatosis and fibrosis were identified using both univariate (Yates corrected chi-square test) and multivariate (stepwise binary logistic regression) analyses to assess the specific effect of each predictor. Factors included in the multivariate analysis were those with a significant level in the univariate analysis. Statistical significance was taken at the 5% level.

Ethical considerations

The aim of the study was explained to all participants. They were assured that refusing participation in this study will not affect their benefit from all services and treatment. A written consent was obtained from all the participants. Security and confidentiality of all the information obtained was observed. Data was collected by personal interviews with participants by one investigator (AFH). The study was approved by the Assiut Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethical committee, and was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

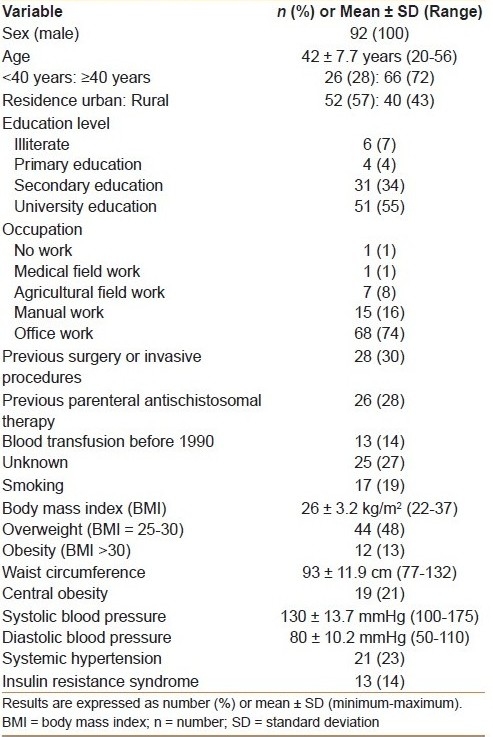

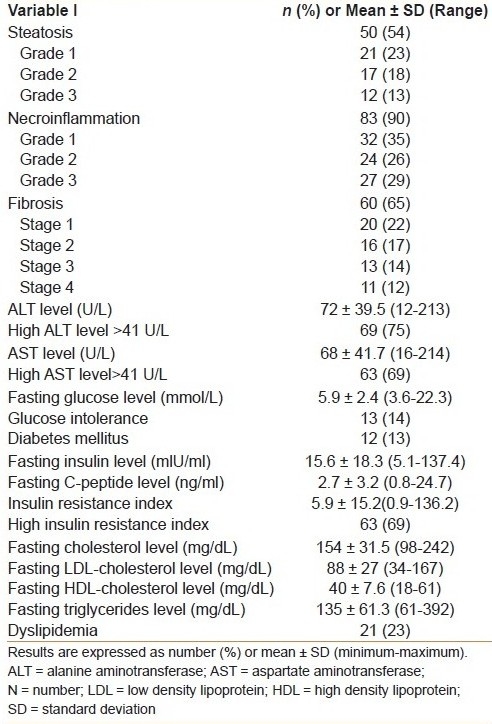

The detailed clinical, laboratory, and pathological characteristics of the 92 patients included in this study are shown in Tables Table 1a and b. All patients were males, and their mean ± SD age was 42 ± 7.7 years. The mean ± SD serum levels of ALT and AST were 72 ± 39.5 U/L and 68 ± 41.1 U/L, respectively. The mean IRI was 5.9 ± 15.2. Insulin resistance (defined as an IRI >1.5) was detected in 63 (69%) patients.

Table 1a.

Patients’ characteristics (n = 92)

Table 1b.

Laboratory and liver biopsy findings in all patients (n = 92)

The potential source of infection was previous surgery or invasive medical procedures in 28 (30%) patients, previous parentral anti-schistosomal therapy in 26 (28%) patients, blood transfusion before 1990 in 13 (14%) patients, and unknown in the remaining 25 (27%) patients probably representing house-hold and/or intra-familial transmission. About half of patients received university education and 75% of them were office workers.

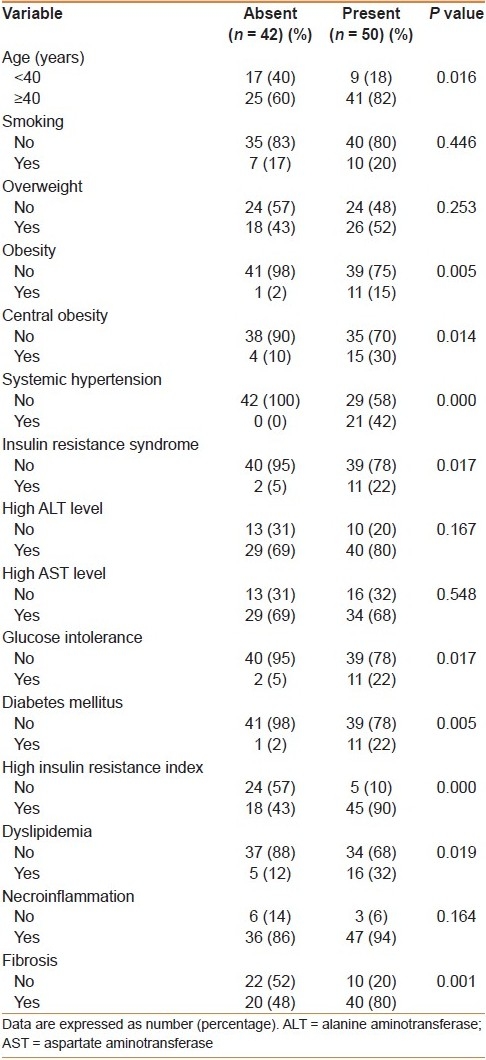

Factors associated with the presence of steatosis

In our study patients, 50 (54%) had steatosis. Steatosis was graded as mild (grade 1) in 23% of patients, moderate (grade 2) in 18%, and marked (grade 3) in 13%. In univariate analysis [Table 2], the presence of steatosis was significantly associated with older age (≥40 years), obesity, central obesity, systemic hypertension, IR, IRS, glucose intolerance, DM, dyslipidemia, and fibrosis. There was no significant association between the presence of steatosis and smoking, overweight, high levels of ALT and AST, and necroinflammation. However, in multivariate analysis [Table 3], only insulin resistance (odds ratio (OR) = 16.3 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 3.4-77.7) was the significant and independent predictor of hepatic steatosis [Table 3].

Table 2.

Factors associated with the presence of steatosis

Table 3.

Factors significantly and independently associated with the presence of steatosis

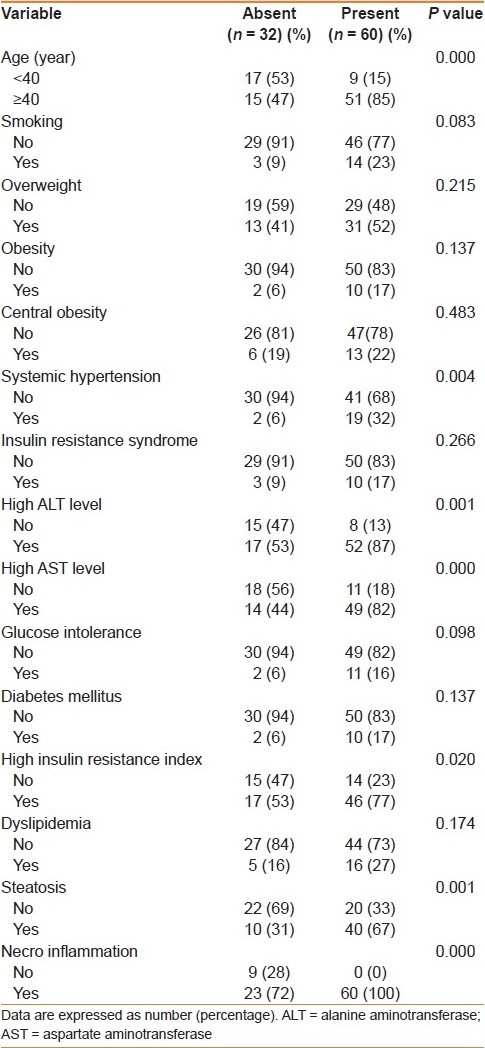

Factors associated with the presence of fibrosis

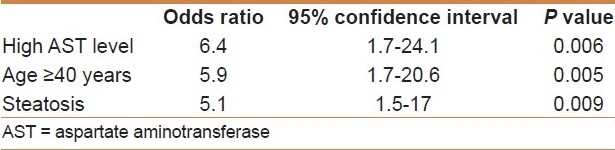

A total of 60 (65%) patients had fibrosis. Fibrosis was classified as stage 1 in 20 (22%) patients, stage 2 in 16 (17%), stage 3 in 13 (14%), and stage 4 (cirrhosis) in 11 (12%). In univariate analysis [Table 4], the presence of fibrosis was significantly associated with older age, systemic hypertension, high levels of ALT and AST, IR, steatosis, and necroinflammation. There was no significant association between the presence of fibrosis and smoking, overweight, obesity, central obesity, glucose intolerance, DM, dyslipidemia, and IRS. However, in multivariate analysis [Table 5], fibrosis was significantly, independently associated with high AST level (OR = 6.4, 95% CI = 1.7-24.1), older age (OR = 5.9, 95% CI = 1.7-20.6), and steatosis (OR = 5.1, 95% CI = 1.5-17).

Table 4.

Factors associated with the presence of fibrosis

Table 5.

Factors significantly and independently associated with the presence of fibrosis

DISCUSSION

There is some controversy with regard to the influence of NAFLD on CHC severity and progression. Either steatosis potentiates the liver cell injury induced by the HCV or it is indicative of a more extensive viral mediated cytodestructive process.[21] In fact, steatosis can be a marker, but not a cause of disease progression. The frequent association between the presence of steatosis and the grade of necroinflammation may suggest that steatosis is a marker of necroinflammation that, in turn, is a marker of fibrosis progression.[22]

In this study that was conducted in 92 patients with treatment-naïve chronic HCV infection, using multivariate analysis, steatosis was significantly and independently associated with IR, but was not associated with necroinflammation. Although an association between steatosis and necroinflammation in patients with chronic HCV infection was reported by few studies,[23,24] Friedenberg and colleagues found that the grade of steatosis was not associated with the grade of necroinflammation.[25] This finding suggest that steatosis is not a necroinflammation byproduct, but may result from a state of IR.

In addition, using multivariate analysis, we found that fibrosis was associated with older age (≥40 years), high AST level, and steatosis. Several studies reported an association between fibrosis and steatosis in patients with chronic HCV infection,[11,15] while some studies failed to find such an association.[16,17] Steatosis was significantly associated with stellate cell activation in patients with chronic HCV infection.[26] Several studies reported an association between fibrosis and age in patients with chronic HCV infection.[5,27] The role of ageing in fibrosis progression can be related to a higher vulnerability to environmental factors (especially oxidative stress) or reduction in blood flow, mitochondria capacity, or immune capacities.[28]

In the present study, there was an association between fibrosis and necroinflammation. However, using multivariate analysis, there was no such association. Several studies on patients with chronic HCV infection showed an association between fibrosis and necroinflammation and suggested that necroinflammation is implicated in the fibrogenesis process,[29,30] Stellate cells are activated around necroinflammation lesions.[31] Some studies found no significant relationship between necroinflammation grades and fibrosis progression.[32,33] However, necroinflammation is a dynamic process in chronic HCV infection and may fluctuate over time. Indeed, the necroinflammation grade reflects the severity of necrosis and inflammation at a given point.[34]

In univariate analysis, there was an association between fibrosis and smoking. However, using multivariate analysis, there was no association between fibrosis and smoking. Tsochatzis and colleagues reported significantly higher necroinflammatory grade in Egyptian smokers with chronic HCV infection,[35] but the total lifetime smoking history was not associated with necroinflammation, suggesting that smoking may have a rapid and reversible hepatotoxic effect.[36]

A link between steatosis and IR has already been reported in previous studies,[11,37] and was attributed to host metabolic disorders or due to HCV infection. Infection with HCV can induce a state of IR independent of the known major risk factors.[38] In addition, Kawagutchi et al., 2004 reported that HCV infection changes a subset of hepatic molecules regulating glucose metabolism. A possible mechanism is that HCV core-induced suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) 3 promotes proteosomal degradation of IR substrates 1 and 2.[39] Furthermore, Akuta et al., 2009 have shown that amino acid substitutions in the HCV core region are the important predictor of severe insulin resistance in patients without cirrhosis and DM.[40]

HCV infection may directly impair the mechanism of insulin signal transduction.[41] Also, it has been shown that the HCV core protein induces gene expression and activity of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma), increasing the transcription of genes involved in hepatic fatty acid synthesis.[42,43] Whether IR is due to host metabolic factors or a direct effect of HCV cannot be determined by this study and warrants further investigation. Treatment of IR may lead to improvement of steatosis and consequently, fibrosis in patients with chronic HCV infection. This suggests that all patients with chronic HCV infection should be screened for IR and its associated metabolic disorders such as type 2 DM, dyslipidemia, systemic hypertension, obesity, and central obesity.[44]

In agreement with this study, a study by Zechini et al., showed a statistically significant positive correlation between baseline aminotransferase values with the hepatitis activity index and fibrosis score.[45] Also, a study by Assy et al., reported a significant positive correlation between AST values and the extent of hepatic fibrosis (r = 0.64).[46] Moreover, AST was an independent predictor of significant fibrosis (F ≥ 2) in chronic HCV patients from Central Saudi Arabia who are infected with Genotype 4, the same genotype that is prevalent in Egypt.[47]

The inclusion of only male patients is one of the strengths of this study to avoid the previously confirmed negative role of menopause on steatosis and the potential benefit of hormone replacement therapy on hepatic fibrosis in HCV infected patients.[48] In addition, all patients were treatment-naïve. This excludes any confounding effect(s) previous treatment on both the laboratory and the histopathological findings. Also, none of our patients had any history of alcohol intake. This represents another strength of this study due to the well-known impact of ethanol consumption on hepatic steatosis,[49,50] a factor that confounds other studies on HCV patients preformed in areas where alcohol consumption is prevalent. A potential limitation of the present study is the lack of data related to serum HCV load, which may not significantly impact the results. Indeed, continuous fluctuation of viral load makes the reliance on a single HCV RNA quantity unsatisfactory. Also, in contrary to the case of HBV infection where viral load predicts outcome, HCV quantity is not an independent predictor of pathology.[48] Another limitation of this study is the deficiency of data related to intake calorie and physical activity as IR can be caused by over-eating or physical inactivity. Unfortunately, this was not included in this study protocol and needs to be considered in any future study addressing this issue.

In conclusion, in this prospective study of patients with naïve chronic HCV infection, hepatic steatosis was associated with and was a significant determinant of hepatic fibrosis, together with older age and high serum AST levels, but is not a marker of disease severity. The main independent predictor of steatosis, in this study was IR. Centers established to providing interferon-based anti-HCV therapy should be joined with a parallel campaign for the prevention, detection, and management of IR-associated metabolic disorders. There should also be programs for increasing public awareness, early detection, and treatment of these problems. This program will have a positive impact not only on decreasing the rate of progression of CHC and increasing HCV response to antiviral therapy, but will also contribute to decreasing the rate of cardiovascular diseases associated with IR syndrome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marcellin P. Hepatitis C: The clinical spectrum of the disease. J Hepatol. 1999;31:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis C: The clinical spectrum of the disease. Hepatol. 1997;26:15S–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persico M, Masarone M, La Mura V, Persico E, Moschella F, Svelto M, et al. Clinical expression of insulin resistance in hepatitis C and B virus-related chronic hepatitis: Differences and similarities. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:462–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fartoux L, Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Poupon R, Serfaty L. Impact of steatosis on progression of fibrosis in patients with mild hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:82–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellentani S, Bedogni G, Miglioli L, Tiribelli C. The epidemiology of fatty liver. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1087–93. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strickland GT, Elhefni H, Salman T, Waked I, Abdel-Hamid M, Mikhail NN, et al. Role of hepatitis C infection in chronic liver disease in Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:436–42. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mofrad PS, Sanyal AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Med Gen Med. 2003;5:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iuliano AD, Feingold E, Wahed AS, Kleiner DE, Belle SH, Conjeevaram HS, et al. Host genetics, steatosis and insulin resistance among African Americans and Caucasian Americans with hepatitis C virus genotype-1 infection. Intervirology. 2009;52:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000214380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papatheodoridis GV, Chrysanthos N, Savvas S, Sevastianos V, Kafiri G, Petraki K, et al. Diabetes mellitus in chronic hepatitis B and C: Prevalence and potential association with the extent of liver fibrosis. J Viral Hepatitis. 2006;13:303–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conjeevaram HS, Kleiner DE, Everhart JE, Hoofnagle JH, Zacks S, Afdhal NH, et al. Race, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;45:80–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafiq N, Younossi ZM. Interaction of metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic hepatitis C. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:207–15. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubbia-Brandt L, Quadri R, Abid K, Giostra E, Malé PJ, Mentha G, et al. Hepatocyte steatosis is a cytopathic effect of hepatitis C virus genotype 3. J Hepatol. 2000;33:106–15. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon A, McLean CA, Pedersen JS, Bailey MJ, Roberts SK. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis B and C: Predictors, distribution and effect on fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2005;43:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiha G, Seif S, Zalata K. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection genotype 4: Prevalence and clinical correlations. Liver Int. 2006;26:80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma P, Balan V, Hernandez J, Rosati M, Williams J, Rodriguez-Luna H, et al. Hepatic steatosis in hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: Does it correlate with body mass index, fibrosis, and HCV risk factors? Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:25–9. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000011597.92851.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jármay K, Karácsony G, Nagy A, Schaff Z. Changes in lipid metabolism in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6422–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Santrach PJ, Moore SB. Host- and disease-specific factors affecting steatosis in chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1998;29:198–206. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asselah T, Ripault MP, Marcellin P. What does chronic hepatitis C steatosis mean? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2003;27:1073–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hepburn MJ, Vos JA, Fillman EP, Lawitz EJ. The accuracy of the report of hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography in patients infected with hepatitis C in a clinical setting: A retrospective observational study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidi M, Muratori P, Granito A, Muratori L, Pappas G, Lenzi M, et al. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis C: Impact on response to anti-viral treatment with peg-interferon and ribavirin. Alimen Pharmacol Therapeut. 2005;22:943–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedenberg F, Pungpapong S, Zaeri N, Braitman LE. The impact of diabetes and obesity on liver histology in patients with hepatitis C. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2003;5:150–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adinolfi LE, Utili R, Ruggiero G. Body composition and hepatic steatosis as precursors of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients. Hepatology. 1999;30:1530–1. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzzi A, Leandro G, Rubbia-Brandt L, James R, Keiser O, Malinverni R, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with liver fibrosis in non-diabetic chronic hepatitis C patients. J Hepatol. 2005;42:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poynter ME, Daynes RA. Peroxysome proliferator-activated receptor a activation modulates cellular redox status, represses nuclear factor-kB signaling, and reduces inflammatory cytokine production in aging. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32833–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hézode C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Nguyen S, Grenard P, Julien B, Zafrani ES, et al. Daily cannabis smoking as a risk factor for progression of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;42:63–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boccato S, Pistis R, Noventa F, Guido M, Benvegnù L, Alberti A. Fibrosis progression in initially mild chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baroni GS, Pastorelli A, Manzin A, Benedetti A, Marucci L, Solforosi L, et al. Hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis are associated with necroinflammatory injury and Th1-like response in chronic hepatitis C. Liver. 1999;19:212–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Lancet. 1997;349:825–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarski JP, Mc Hutchison J, Bronowicki JP, Sturm N, Garcia-Kennedy R, Hodaj E, et al. Rate of natural disease progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2003;38:307–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asselah T, Boyer N, Guimont MC, Cazals-Hatem D, Tubach F, Nahon K, et al. Liver fibrosis is not associated with steatosis but with necroinflammation in French patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2003;52:1638–43. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsochatzis E, Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Tiniakos DG, Manesis EK, Archimandritis AJ. Smoking is associated with steatosis and severe fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C but not B. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:752–9. doi: 10.1080/00365520902803515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hézode C, Lonjon I, Roudot-Thoraval F, Mavier JP, Pawlotsky JM, Zafrani ES, et al. Impact of smoking on histological liver lesions in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2003;52:126–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camma C, Bruno S, Marco VD, Di Bona D, Rumi M, Vinci M, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with steatosis in nondiabetic patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:64–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hui JM, Sud A, Farrell GC, Bandara P, Byth K, Kench JG, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and insulin resistance: How do they interact, and what is the effect on hepatic fibrosis? Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1695–704. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawaguchi T, Yoshida T, Harada M, Hisamoto T, Nagao Y, Ide T, et al. Hepatitis C virus down-regulates insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 through up-regulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1499–508. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63408-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Hirakawa M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, et al. Amino acid substitutions in the hepatitis C virus core region of genotype 1b are the important predictor of severe insulin resistance in patients without cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1032–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aytug S, Reich D, Sapiro LE, Bernstein D, Begum N. Impaired IRS-1/PI3-kinase signaling in patients with HCV: A mechanism for increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Hepatology. 2003;38:1384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Del Campo JA, Romero-Gomez M. Steatosis and insulin resistance in hepatitis C: A way out for the virus? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5014–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Negro F, Sanyal AJ. Hepatitis C virus, steatosis and lipid abnormalities: Clinical and pathogenic data. Liver Int. 2009;29:26–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Younossi ZM, McCullough AJ. Metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C virus: Impact on disease progression and treatment response. Liver Int. 2009;29:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zechini B, Pasquazzi C, Aceti A. Correlation of serum aminotransferases with HCV RNA levels and histological findings in patients with chronic hepatitis C: The role of serum aspartate transaminase in the evaluation of disease progression. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:891–6. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Assy N, Minuk GY. Serum aspartate but not alanine aminotransferase levels help to predict the histological features of chronic hepatitis C viral infections in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1545–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Ashgar H, Helmy A, Khan MQ, Al-Kahtani K, Al-Quaiz M, Rezeig M, et al. Predictors of sustained viral response to a 48-week course of peginterferon α-2a and ribavirin in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 4. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:4–14. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Codes L, Asselah T, Cazals-Hatem D, Tubach F, Vidaud D, Paraná R, et al. Liver fibrosis in women with chronic hepatitis C: Evidence for the negative role of the menopause and steatosis and the potential benefit of hormone replacement therapy. Gut. 2007;56:390–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serfaty L, Poujol-Robert A, Carbonell N, Chazouillères O, Poupon RE, Poupon R. Effect of the interaction between steatosis and alcohol intake on liver fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1807–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vădan R, Gheorghe L, Becheanu G, Iacob R, Iacob S, Gheorghe C. Predictive factors for the severity of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C and moderate alcohol consumption. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2003;12:183–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]