Abstract

Background/Aim:

α-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency results from mutations of the protease inhibitor (PI). The AAT gene is mapped on chromosome 14 and has been associated with chronic liver disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Objective:

To determine the frequency of AAT mutations on S and Z carrier alleles in healthy Saudi individuals from Qassim Province in Saudi Arabia.

Patients and Methods:

A total of 158 healthy, unrelated participants from Qassim Province were recruited. They were genotyped for the two AAT-deficiency alleles, PI*S and PI*Z, using polymerase chain reaction, with primers designed throughout to mediate site-directed mutagenesis.

Results:

Of the 158 subjects, 11.39% were carriers for the S mutation (i.e., had the MS genotype), whereas 2.53% were carriers for the Z mutation (i.e., had the MZ genotype). The SZ genotype was present in 3.8% of subjects, while the homozygous genotype SS was present in 1.9% of subjects. No subjects showed the ZZ mutant genotype. Accordingly, frequency of the mutant S and Z alleles of AAT gene was 9.49% and 3.19%, respectively.

Conclusion:

The results obtained showed a high prevalence of the AAT deficiency allele in the Saudi population. This probably warrants adoption of a screening program for at-risk individuals, so that they might initiate adequate prophylactic measures.

Keywords: α-1 antitrypsin, Saudi Arabia, S allele, Z allele

α-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency is one of the most common serious and potentially fatal hereditary disorders in the adult population. For the most part, AAT deficiency is characterized by clinical manifestations such as respiratory tract diseases and cirrhosis of the liver.[1] It affects all major racial subgroups, with an estimated 120.5 million affected individuals and carriers in the 58 countries surveyed worldwide. In addition, the prevalence of AAT deficiency varies markedly from one country to the other, as well as from one region to the other within a given country.[2]

AAT is a 52-kD glycoprotein comprising a single chain of 394 amino acid residues and three asparagine-linked complex-carbohydrate side chains.[3] In addition to its ability to inhibit trypsin,[4] AAT can also inhibit most neutrophilic serine proteases. Its specific target, however, is neutrophil elastase, an enzyme that digests elastin, basement membrane, and other extracellular matrix components. Indeed, AAT is produced mainly by hepatocytes and secreted into the plasma; it diffuses passively into all of the body organs to protect extracellular tissue structures against a neutrophil elastaseattack[5] (which can cause alveolar parenchyma and support-matrix damage in the lungs).[6]

AAT deficiency is an autosomal-recessive metabolic disease that results from mutations on the protease inhibitor (PI) locus, with encoded gene 14q31-32.3.[7] The polymorphism described on this gene gives rise to protein variants. The gene is organized into three noncoding exons (Ia, Ib, and Ic) and four coding exons (II, III, IV, and V) through sixintrons.[8] The open reading frame is located in the last four exons and codes for 418 amino acids. The first 24 amino acids form a signal peptide, which is cleaved during intracellular processing, resulting in a 394 amino acid-long mature protein.[9,10]

The normal gene is designated PI*M and is highly pleomorphic, with more than 100 normal and deficiency alleles having been identified using assays based on isoelectric focusing.[11,12] Most investigators have reported that the two most frequent mutations on the PI locus are PI*S (Glu264Val), which expresses approximately 50 to 60% of AAT, and PI*Z (Glu342Lys), which expresses approximately 10 to 20% of AAT, compared with M-phenotype subjects.[13,14] These two mutations have different geographic distributions, with PI*S reaching the highest frequencies in the Iberia Peninsula and PI*Z reaching the highest frequencies in northern Europe. PI*ZZ, PI*SZ, and PI*SS are considered to be deficiency genotypes and both PI*MS and PI*MZ are carriers of the anomaly. However, PI*ZZ individuals are at higher risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) than PI*SZ subjects.[15]

This work aims to determine the frequency of potentially harmful deficiency alleles in the AAT gene among healthy Saudi individuals.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Recruitment of individuals

The study population was recruited from primary care clinics within Qassim University's medical centre. The sample comprised students and employees who visited the center for a routine checkup. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals. Ethics approval was obtained from the scientific and ethical committees of Qassim University College of Medicine.

Sampling techniques

For all blood samples, genomic deoxyribonucleic acid(DNA) was extracted from 1 ml of peripheral blood using the MagNA Pure LV blood reagent set (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instruction. DNA from each sample was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a genotyping kit to detect the S and Z alleles.

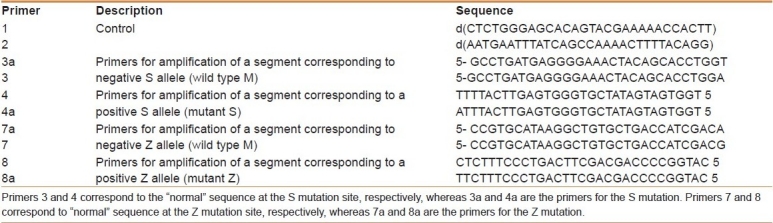

Each sample underwent PCR involving two different sets of amplification primers—the first being complementary to the normal sequence at the Pi*Z or the Pi*S locus (stock primer mix A) and the second being complementary to the Z or S mutant genotype sequence at the Pi*Z or Pi*S locus (stock primer mix B)—derived from the known sequences.[16] The specific primers successfully identified the S and Z alleles in each case, and were used in optimal PCR conditions [Table 1]. The final 50 μl volume of PCR reactant contained 25 μl of PCR master mix, 1 μl of primer 1 (0.1 μM), 1 μl of primer 2 (0.1 μM), template DNA (105 to 106 copies), and 23 μl sterile double-distilled H2O. The amplification procedure consisted of a time delay enzyme activation step of 20 minutes at 94°C, followed by 32 cycles,eachone composedof 2 minutes at 94°C (denaturation), 1 minute at 62°C (annealing), and 1 minute at 72°C (extension); there was a final extension step of 10 minutes at 72°C.

Table 1.

The complete stable and destabilized primer panel

Gel electrophoresis

Separation and determination of the products of the PCR was achieved by agarose gel electrophoresis. Each sample pair was run in adjacent lanes; this resulted in a characteristic pattern of bands that was unique to a genotype (i.e., Pi*M, Pi *MZ, Pi*MS, Pi*SS, Pi*SZ, or Pi*ZZ), thus enabling the genotype of each sample to be determined. Using horizontal submarine gels with combs suspended 1 mm above, the gel trays were prepared using 100 ml of Tris/Borate/Ethylenediaminetetraacetic-acid(TBE) buffer solutioncontaining 2% agarose. As the running buffer, TBEcontaining 0.1 mg/mlSYBR green and 0.1% bromophenol blue was used. Electrophoresis was then carried out at 5 V/cm-1 until the dye front had migrated 4 cm toward the anode. After electrophoresis, the gels were placed on an ultraviolet transilluminator at 260 nm and photographed.

RESULTS

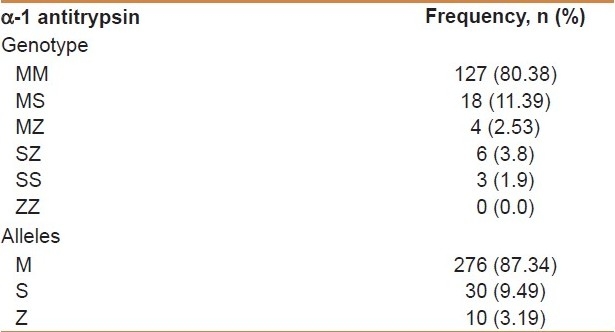

We obtained blood samples from 158 healthy, unrelated individuals of Saudi Arab ethnicity. Their ages ranged from 12 to 60 years, with a mean age of 24.52 years. The sample included 105 (66.5%) males and 53 (33.5%) females; 11.39% of sampled subjects were carriers for the S mutation (i.e., had the MS genotype),whereas2.53% were carriers for the Z mutation (i.e., had the MZ genotype). The SZ genotype was present in 3.8% of subjects, while the homozygous genotype SS was present in 1.9% of subjects. No one showed the ZZ mutant genotype. Frequency of the mutant S allele of the AAT gene was 9.49%, while that of the Z allele was 3.19%. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of AAT genotypes and alleles in the study population: N= 158

DISCUSSION

Since the first report of AAT deficiency in Saudi Arabia in 1979,[17] there has been an increased interest in screening more Saudi individuals to estimate the prevalence of this genetic mutation. The last report of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences on the prevalence of AAT deficiency in Saudi Arabia called for the results to be both confirmed and extended to other geographic regions of Saudi Arabia.[18] The present study describes for the first time the prevalence of the two most common AAT deficiency alleles, PI*S and PI*Z, in the Saudi population of Qassim Province, and shows the relatively high frequency of both mutations. Interestingly, allele frequencies of the mutant S allele and the mutant Z allele of the AAT gene were 9.49% and 3.19%, respectively, which is slightly higher than their frequencies in a previous report from a central area of Saudi Arabia (5.2% and 2.2%, respectively).[19] The difference is understandable because current study use more accurate technique to identify the abnormal allies.

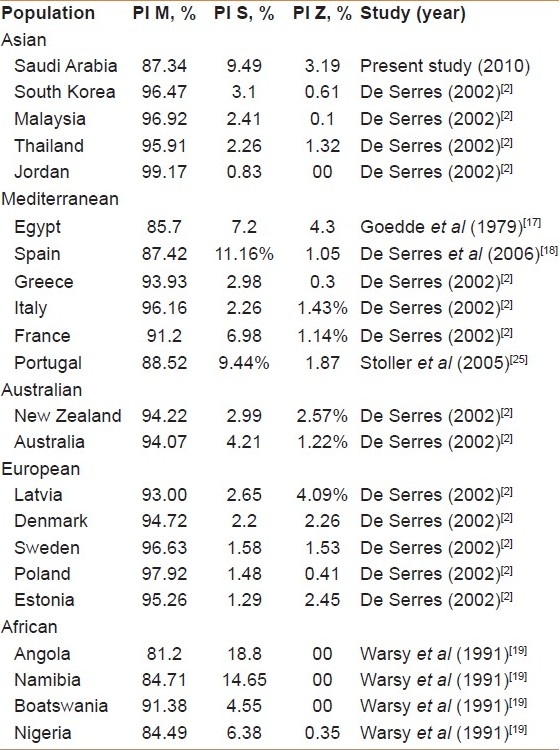

Our cohort's S-allele frequency was fairly comparable with the frequencies of surrounding populations from Mediterranean areas and African countries: Egypt, 7.2%[20]; Portugal, 9.44%[21]; France, 6.98%[2]; Spain, 11.16%[22]; Angola,18.8%[23]; Namibia, 14.7%[23]; Nigeria, 6.4%[23]; and Botswana, 4.5%[23]. However, our cohort's S-allele frequency was higher than those reported in other countries of the world: Tunisia, 0.6%[24]; Jordan, 0.83%, Malaysia, 2.41%, Thailand, 2.26%, and South Korea, 3.1%.[2]

Similarly, the frequency of the PI*Z mutant allele in our cohort (3.19%) was fairly comparable with European countries such as Denmark (2.26%), Estonia (2.45%), Poland (2.45%), Sweden (2.3%), and New Zealand (2.57%), but lower than the frequency in Latvia (4.09%).[2] However, the frequency of the PI*Z mutant allele in our cohort was much higher than the frequency in Jordan (0.00%), Malaysia (0.1%), Thailand (1.32%), and South Korea (0.61%). These comparisons are summarized in Table 3.[2,17–19,25]

Table 3.

Allele frequencies of Pi M, PI S and PI Z in Saudi population compared withother populations[2,17–19,25]

It was previously reported that the levels of AAT in the blood of Saudi individuals is 95 to 275 mg/dl for adult males and 100 to 350 mg/dl for adult females.[26] In a recent study comparing the international prevalence of AAT mutations, in which patients were pooled from multiple studies conducted in Saudi Arabia (for an estimatedtotal of 801 screened Saudi patients), it was concluded that the total calculated prevalence of PI*S and PI*Z alleles is 11.3% for this population.[18]

It has been documented in nationwide prospective screening studies that only 10 to 15% of the Pi*ZZ population develop clinically significant liver disease in the first 20 years of life; however, 85 to 90% of these individuals have elevated serum transaminases in infancy without any obvious liver injury by the age of 18 years, while patients heterozygous for the Pi*Z allele still bear an increased risk for chronic liver disease.[27,28] Also, it was demonstrated that hepatic dysfunction could develop at as early as 6 months of age among MS-allele heterozygotes, with subsequent development of cryptogenic cirrhosis between the ages of 1 month and 18 years.[29]

Several studies indicate that AAT deficiency is far less familiar to many clinicians than its prevalence would suggest.[30] Unrecognized individuals with severe AAT deficiency are usually the result of the following two reasons. The first is masked normal phenotype expression despite severe deficiency and the second is undiagnosed cases despite suggestive symptoms.[25,31,32] The relative proportion of these two groups remains unknown. It was estimated that the average delay between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of AAT deficiency is about 7.2 years. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that under-recognition persists, despite extensive educational efforts and the publication of evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management of AAT deficiency.[5,30,31]

Current study should encourage practicing physicians in Saudi Arabia to adhere to published guidelines by routinely screening symptomatic adults with emphysema, COPD,asthma, or unexplained liver disease. AdvancedAAT patients might be candidate of AAT replacement therapy, while AAT carrier diagnosis might provide genetic counseling to persons who are planning a pregnancy or are in the prenatal period. In addition, awareness of carrying a gene that may increase the susceptibility to COPD may be an additional factor for a successful enrollment of patients in smoking cessation program.[33]

CONCLUSION

The results obtained from this study, which show the relatively high frequency for S and Z allele mutations leading to AAT deficiency and subsequent potential risks of liver dysfunction and COPD,[34–42] probably warrant the adoption of screening measures for genetically susceptible groups. However, we recommend that further studies of the Saudi population be carried out, especially to address the effects of genetic background (represented by such potentially harmful gene mutations), together with other environmental factors on the incidence and prevalence of hepatic and pulmonary disorders.

Footnotes

Source of Support: 1st author received grant from Qassim University

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lomas DA, Parfrey H. Alpha 1 Antitrypsin deficiency 4: Molecular pathophysiology. Thorax. 2004;59:529–35. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.006528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Serres FJ. Worldwide racial and ethnic distribution of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: Details of an analysis of published genetic epidemiological surveys. Chest. 2002;122:1818–29. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.5.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brantly ML, Paul LD, Miller BH, Falk RT, Wu M, Crystal RG. Clinical features and history of the destructive lung disease associated with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency of adults with pulmonary symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:327–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neto L, Junior C, Cardoso G, Ferreira A, Marino G, Monteiro N. Pulmonary aspects in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Rev Port Pneumol. 2004;10:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Standards for the diagnosis and management of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:818–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.168.7.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stockley RA. Alpha (1)-antitrypsin: More than just deficiency. Thorax. 2004;59:363–4. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.023572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMeo DL, Silverman EK. A1-Antitrypsin deficiency.2: Genetic aspects of alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency: Phenotypes and genetic modifiers of emphysema risk. Thorax. 2004;59:259–64. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blank CA, Brantly M. Clinical features and molecular characteristics of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Ann Allergy. 1994;72:105–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long GL, Chandra T, Woo SL, Davie EW, Kurachi K. Complete sequence of the cDNA for human alpha 1-antitrypsin and the gene for the S variant. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4828–37. doi: 10.1021/bi00316a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlino E, Cortese R, Ciliberto G. The human alpha-1- antitrypsin gene is transcribed from two different promoters in macrophages and hepatocytes. EMBO J. 1987;6:2767–71. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Report of a WHO meeting. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 1996. [Accessed 2010 Aug 11]. Human Genetics Programme, Division of Noncommunicable Diseases. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/HQ/1996/WHO_HGN_AATD_WG_96.5.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alpha 1-Pi deficiency. World Health Organization [article in German] Pneumologie. 1997;51:885–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Lancet. 2005;365:2225–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrell RW, Lomas DA. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency-a model for conformational diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:45–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco I, de Serres FJ, Fernandez-Bustillo E, Lara B, Miravitlles M. Estimated numbers and prevalence of PI*S and PI*Z alleles of alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency in European countries. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:77–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00062305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockley RA, Campbell EJ. Alpha-1-antitrypsin genotyping with mouthwash specimens. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:356–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17303560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goedde HW, Benkmann HG, Agarwal DP, Hirth L, Bienzle U, Dietrich M, et al. Genetic studies in Saudi Arabia: red cell enzyme, haemoglobin and serum protein polymorphisms. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1979;50:271–7. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330500217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Serres FJ, Blanco I, Fernández-Bustillo E. Estimated numbers and prevalence of PI*S and PI*Z deficiency alleles of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in Asia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1091–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00029806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warsy AS, El-Hazmi MA, Sedrani SH, Kinhal M. Alpha-1-antitrypsin phenotypes in Saudi Arabia: A study in the central province. Ann Saudi Med. 1991;11:159–62. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1991.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Settin A, El-Bendary M, Abo-Al-Kassem R, El Baz R. Molecular analysis of A1AT (S and Z) and HFE (C282Y and H63D) gene mutations in Egyptian cases with HCV liver cirrhosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spınola C, Bruges-Armas J, Pereira C, Brehm A, Spınola H. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency in Madeira (Portugal): The highest prevalence in the world. Respir Med. 2009;103:1498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De la Roza C, Lara B, Vila S, Miravitlles M. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: Situation in Spain and development of a screening program. Arch Bronconeumol. 2006;42:290–8. doi: 10.1016/s1579-2129(06)60145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Serres FJ, Blanco I, Bustillo EF. Pi S and Pi Z alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency worldwide.A review of existing genetic epidemiological data. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2007;67:184–208. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2007.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denden S, Khelil H, Perrin P, Daimi H, Leban N, Ouaja A, et al. Alpha 1 antitrypsin polymorphism in the tunisian population with special reference to pulmonary disease. Pathol Biol. 2008;56:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoller JK, Sandhaus RA, Turino G, Dickson R, Rodgers K, Strange C. Delay in diagnosis of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: A continuing problem. Chest. 2005;128:1989–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sedrani SH, el-Hinnawi SI, Warsy AS. Establishment of a normal reference range for alpha 1-antitrypsin in Saudis using rate nephelometry. Am J Med Sci. 1988;296:22–6. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sveger T, Thelin T, McNeil TF. Young adults with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency identified neonatally: their health, knowledge about and adaptation to the high risk condition. Acta Pediatr. 1997;86:37–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volpert D, Molleston JP, Perlmutter DH. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency-associated liver disease progresses slowly in some children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:258–63. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima LC, Matte U, Leistner S, Bopp AR, Scholl VC, Giugliani R, et al. Molecular analysis of the Pi Z allele in patients with liver disease. Am J Med Genet. 2001;287:90–104. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman EK, Miletich JP, Pierce JA, Sherman LA, Endicott SK, Broze GJ, Jr, et al. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: High prevalence in the St.Louis area determined by direct population screening. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:961–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campos MA, Waner A, Zhang G, Sandhaus RA. Trends in the diagnosis of symptomatic patients with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency between 1968 and 2003. Chest. 2005;128:1179–86. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoller JK, Smith P, Yang P, Spray J. Physical and social impact of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: Results of a survey. Cleve Clin J Med. 1994;61:461. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.61.6.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrarotti I, Gorrini M, Scabini I, Ottaviani S, Mazzola P, Campo I, et al. Secondary outputs of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency targeted detection programme. Respir Med. 2008;102:354–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikebe N, Akaike T, Miyamoto Y, Hayashida K, Yoshitake J, Ogawa M, et al. Protective effect of S-nitrosylated alpha(1)-protease inhibitor on hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:904–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perlmutter DH. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: Liver disease associated with retention of a mutant secretory glycoprotein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;232:39–56. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-394-1:39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perlmutter DH. Liver injury in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency: An aggregated protein induces mitochondrial injury. J ClinInvestig. 2002;110:1579–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI16787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teckman JH, An JK, Blomenkamp K, Schmidt B, Perlmutter D. Mitochondrial autophagy and injury in the liver in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G851–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00175.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teckman JH, An JK, Loethen S, Perlmutter DH. Fasting in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficient liver: Constitutive activation of autophagy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G1156–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00041.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teckman JH, Perlmutter DH. Retention of mutant alpha (1)-antitrypsin Z in endoplasmic reticulum is associated with an autophagic response. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G961–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.5.G961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldonyte R, Jansson L, Ljungberg O, Larsson S, Janciauskiene S. Polymerized alpha-antitrypsin is present on lung vascular endothelium.New insights into the biological significance of alpha-antitrypsin polymerisation. Histopathology. 2004;45:587–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulgrew AT, Taggart C, Lawless MW, Green CM, Brantly ML, O’Neill SJ, et al. Z alpha-1-antitrypsin polymerizes in the lung and serves as a neutrophil chemoattractant. Chest. 2004;125:1607–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.5.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strange C, Stoller JK, Sandhaus RA, Dickson R, Turino G. Results of a survey of patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Respiration. 2006;73:185–90. doi: 10.1159/000088061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]