Abstract

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is not uncommon in patients with acute leukemia due to frequent blood transfusions. The treatment of HCV in patients with acute leukemia can produce profound immune dysfunction with the risk of severe cytopenia. We report the case of a young man who was treated with combined therapy of peginterferon α 2a and ribavirin for HCV while he was on maintenance anti-leukemic treatment. The patient required reduction in the dose of peginterferon α 2a and the addition of filgrastim due to neutropenia. Therapy for HCV was continued for 72 weeks and at the end of therapy, the patient had undetectable HCV RNA. The patient maintained a sustained viral response two years after the end of therapy and developed complete remission of leukemia, whereupon his anti-leukemic therapy was also discontinued. We recommend conducting further large prospective studies in HCV patients treated for leukemia to determine the safety and efficacy of antiviral therapy in this group of patients.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic HCV hepatitis, peginterferon α-2a

Hepatitis C is not uncommon in patients with various hematological malignancies, as these patients frequently require blood transfusions during the course of their disease. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) hepatitis in pediatric patients with acute leukemia shows wide variation among different studies ranging from 1 to 43%.[1] Treatment of HCV in this group of patients has special safety concerns. The combined use of anti-HCV and anti-leukemic therapy may cause severe myelo-suppression with serious neutropenia.

We report the case of a young adult male patient who was found to have HCV hepatitis with genotype 1 during the course of therapy for acute leukemia. The patient received combined treatment with peginterferon α 2a and ribavirin while he was on maintenance anti-leukemic treatment.

CASE REPORT

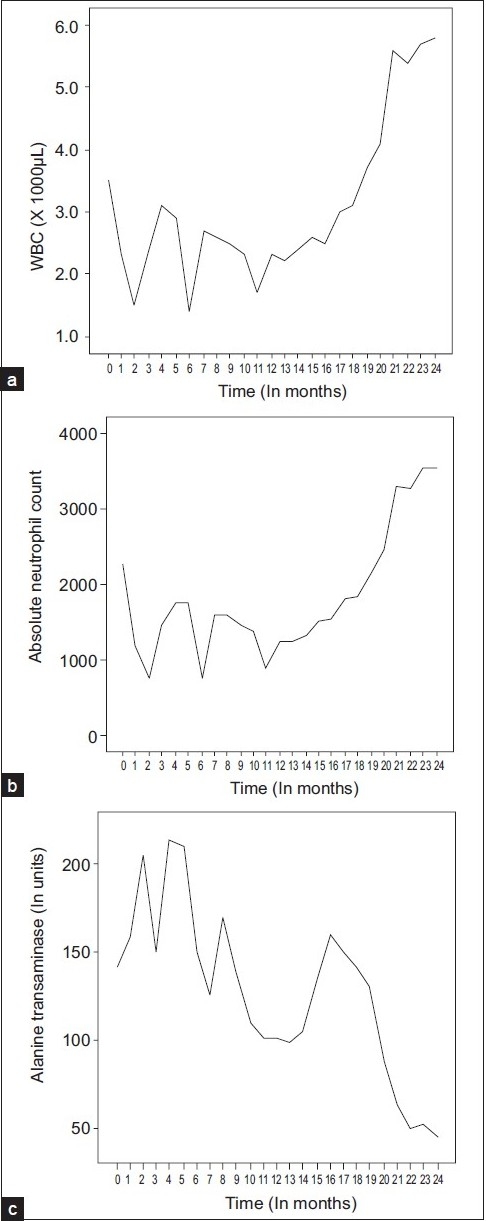

A 22-year-old male was diagnosed as having acute lymphobastic leukemia (ALL) in 2004. After induction and consolidation phases of chemotherapy and while in remission, he was started on maintenance chemotherapy with methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, and dexamethosone. During therapy, he developed high bilirubin and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. The patient had a history of blood transfusion about six months before his current presentation but denied any past history of liver disease. The patient was obese with a BMI of 36 and a known diabetic controlled on oral hypoglycemic agents. There were no stigmata of chronic liver disease and there was no hepatosplenomegaly. Total bilirubin was 29 μmol/L and serum albumin was 28 g/dl. Urea, creatinine, and electrolytes were within normal limits. Serology for HBsAg, HIV, toxoplasmosis, cytomegolvirus, and brucella was negative. Anti-HCV was strongly reactive with an HCV RNA of 2,230,000 IU/ml (genotype 1). Liver histology revealed grade 3/4 inflammatory activity and stage 2/6 fibrosis, according to Ishak modified histological activity index.[2] After improvement of septicaemia, maintenance chemotherapy was restarted. However, his ALT remained >2 times the upper limit of normal. The risks and benefits of the anti-HCV treatment were discussed with the patient and treatment was initiated with subcutaneous peginterferon α-2a 180 μg/week and oral ribavirin of 1200 mg/day along with vincristine and 6- mercaptopurine. Eight weeks into therapy, due to the development of neutropenia, the dose of peginterferon α-2a was reduced to 135 micrograms/week. After 12 weeks of therapy, the HCV RNA was 48,700 IU/ml, indicating insufficient virological response. The reduced chances of viral clearance were explained to the patient who preferred to continue therapy. At 24 weeks of therapy, his HCV RNA became undetectable, but due to neutropenia he required recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor, [Filgrastim] 300 μg subcutaneously, twice weekly. Filgrastim therapy was adjusted in order to maintain the neutrophil count above 1.0 × 103/uLfor the entire period of anti-viral therapy [Figure 1]. As the patient had late response, therapy was continued for 72 weeks during which he remained on maintenance chemotherapy. He remained HCV RNA negative at the end of therapy and at 26 weeks after discontinuation of therapy, indicating that he had achieved sustained viral response (SVR). He was also closely followed up by the medical oncologist and remained in remission from his leukemia. Six months after having obtained SVR, his maintenance chemotherapy was also discontinued. He has been followed up regularly and his leukaemia continues to be in remission.

Figure 1.

Tracings of the white blood cells (a), the absolute neutrophil count (b), and the alanine aminotransferase (c) against follow-up time in months

DISCUSSION

Although the association between HCV infection and hematological malignancies has been the focus of several previous publications, the causal relation of such an association has not been conclusive. Dibendetto et al,[3] in a retrospective study of 87 children with ALL, found that 32% were positive for HCV. All HCV-positive patients frequently had elevated ALT and total bilirubin levels. About 18% of those patients had signs of chronic liver disease. In another study from northern Italy, 43% of children with ALL were found to be HCV positive.[4] Some studies suggest a positive association between HCV and the risk of hematological malignancies such as B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[5]

Patients with leukemia may have a greater risk of exposure to HCV infection due to the frequent blood transfusions. In the present case, patient had history of blood transfusion 6 months before the diagnosis of the HCV although it is questionable whether a recent infection could have caused 2/6 fibrosis.[6] Although the patient had a high BMI, there was no evidence on liver biopsy to suggest that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease may have contributed to accelerated development of fibrosis.

In patients with hematological malignancy, HCV may have little impact on the short-term survival of leukemia patients. However, the long-term survival of such patients may be impacted due to the development of cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, given that the natural history of HCV may be more aggressive in patients with hematological malignancies, because of simultaneous administration of cytotoxic therapy.[7] Recent advances in the treatment of cancer and in supportive care have resulted in longer life expectancy of patients with hematological malignancies. Treatment of the HCV infection may increase the survival. In our patient, initiation of HCV treatment was considered to be necessary because fibrosis had already been documented and further delay in the initiation of antiviral therapy may have led to progression of the fibrosis.

The current gold standard for treatment of HCV is the combined treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for a period of 24–48 weeks, depending on the viral genotype.[8] The present report describes the successful outcome of combined antiviral therapy for chronic HCV during therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia with achievement of SVR. The patient received simultaneous maintenance therapy of ALL and pegylated interferon and ribavirin for HCV. The main risk associated with this simultaneous therapy was the increased risk of myelosuppression. During the course of therapy the patient developed significant neutopenia; but this was readily reversed when the dose of pegylated interferon was reduced to 135 mcg per week and G-CSF was started. The mechanism of myelosuppression was probably a direct effect of interferon and cytotoxic therapy on bone marrow progenitor cells. Prior to the introduction of filgrastim, hematotoxicity was the main reason for withholding antiviral therapy from HCV patients. However, with its introduction, several patients are now able to complete their antiviral therapy.[9] This approach may allow for the required drug delivery for viral hepatitis or leukemia. For this reason, our patient was able to receive full maintenance therapy for ALL during the treatment for HCV without any dose reduction. This was in contrast to previous case studies where dose reduction or suspension of therapy was required in up to 80% if patients who were anti-HCV positive.[10]

As the patient achieved suboptimal virological response, the treatment was continued for 72 weeks. Berg et al.[11] have shown that in patients with HCV genotype 1, who achieve partial early virological response, extending treatment duration to 72 weeks may significantly improve SVR.

Our patient developed a remission of his leukemia and this was maintained for two years after discontinuation of maintenance anti-leukemic therapy. This might have been a spontaneous remission after the treatment of leukemia or may be due to simultaneous treatment with interferon, as interferon has been shown to have some anti-leukemic effect in view of some data from clinical and in vitro studies showing efficacy of interferon against acute leukaemia.[12]

There are limited data available about the treatment of chronic HCV in patients with various hematological malignancies. Komatsu et al first described the use of interferon-α alone in 13 pediatric patients with acute leukemia.[13] The treatment was started after completion of treatment for acute leukemia and was continued for only 22 weeks. Thirty eight percent of children were able to have complete response at the end of treatment. It was not mentioned whether any patient had SVR. In another report, Waldron described the use of interferon a alone in a patient with chronic HCV hepatitis during therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.[14] The patient required modification of maintenance anti-leukemic treatment. Interferon therapy was continued for 27 months. Although, HCV PCR was undetectable at the end of therapy, but eventually patient did not achieve SVR. In another study by Lackner et al.[15] 12 patients with chronic hepatitis C with hematological malignancies received combined therapy with interferon a and ribavirin for 12 months. Treatment was well tolerated and about 50% of patients were able to achieve SVR.

In conclusion, this is the first report that shows successful treatment of chronic HCV in a patient with ALL who was simultaneously receiving maintenance antileukemic therapy. This report also demonstrates that combined anti-viral therapy for HCV can be safely administered with anti-leukemic therapy in patients with ALL. The safety and efficacy of combined treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin was almost the same as in patients who are not receiving antileukemic therapy. This also highlights the importance of conducting large prospective studies in this group of patients to determine the safety and efficacy of the current gold standard therapy for HCV.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paydas S, Kiliç B, Sahin B, Buğdayci R. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders in Southern Turkey. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1303–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, DeGroote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dibenedetto SP, Ragusa R, Sciacca A, Di Cataldo A, Miraglia V, D’Amico S, et al. Incidence and morbidity of infection by hepatitis C virus in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:271–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01954518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campello C, Poli A, Dal MG, Besozzi-Valentini F. Seroprevalence, viremia and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus: A community-based population study in northern Italy. Infection. 2002;30:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s15010-001-1197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schöllkopf C, Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H, Rostgaard K, Panum I, Vinner L, et al. Hepatitis C infection and risk of malignant lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1885–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman AJ, Dore GJ, Law MG, Thorpe M, Von Overbeck J, Lloyd AR, et al. Estimating progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;34:809–16. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribas A, Butturini A, Locasciulli A, Aricò M, Gale RP. How important is hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infection in persons with acute leukemia? Leuk Res. 1997;21:785–8. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(97)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrine SK, Rossi S, Navarro VJ. Management of patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Exp Med. 2006;6:20–6. doi: 10.1007/s10238-006-0089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danish FA, Koul SS, Subhani FR, Rabbani AE, Yasmin S. Role of hematopoietic growth factors as adjuncts in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C patients. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:151–7. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.41739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dibenedetto SP, Ragusa R, Sciacca A, Di Cataldo A, Miraglia V, D’Amico S, et al. Incidence and morbidity of infection by hepatitis C virus in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:271–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01954518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg T, Von Wagner M, Nasser S, Sarrazin C, Heintges T, Buggisch P, et al. Extended treatment duration for hepatitis C virus type 1: Comparing 48 versus 72 weeks of peginterferon-alfa-2a plus ribavirin. Gastroenterol. 2006;130:1086–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muretto P, Tomassoni S, Staccioli MP, Tabellini L, D’Adamo F, Delfini C. Does interferon-a exert an anti-leukemic effect by enhancing cell mediated immunity in chronic myeloid leukemia? Haematologica. 2000;85:212–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu H, Fujisawa T, Inui A, Miyakawa Y, Onoue M, Sekine I, et al. Efficacy of interferon in treating chronic hepatitis C in children with a history of acute leukemia. Blood. 1996;87:4072–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldron P. Interferon treatment of chronic active hepatitis C during therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 1999;61:130–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199906)61:2<130::aid-ajh10>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lackner H, Moser A, Deutsch J, Kessler HH, Benesch M, Kerbl R, et al. Interferon-alpha and ribavirin in treating children and young adults with chronic hepatitis C after malignancy. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E53. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]