Abstract

Choroidal carcinoma is an insidious tumor frequently causing late liver metastases which are associated with a poor outcome. Since metastatic liver lesions are potentially resectable with curative intention, tight follow-up schedules after treatment of primary tumors for the early detection of liver metastasis have been proposed. The methods employed so far, however, have proven to be of limited sensitivity, and it is likely that a combined approach comprising the use of both imaging techniques and biohumoral markers will, in the future, improve the sensitivity of methods aiming at detecting liver metastasis early. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is increasingly used in the clinic due to its advantage over conventional sonography for the early detection of tumor lesions and thus represents a promising accurate and cost-effective diagnostic tool. Its use for the early diagnosis of metastatic choroidal cancer has never been proposed before in the literature. Here, we describe for the first time the CEUS features of a large liver metastasis originating from choroidal cancer occurring 13 years after diagnosis in comparison to PET-CT, MRI and conventional sonography. Furthermore, we propose CEUS as a routine follow-up method for the early detection of liver metastasis of patients affected by choroidal carcinoma.

Key words: Contrast-enhanced ultrasound, Choroidal melanoma, Metastasis

Introduction

Choroidal melanoma is a primary intraocular malignant tumor frequently causing liver metastasis several years after the first diagnosis. Liver metastasis may occur in absence of specific complaints and has been reported to present with signs of impaired liver function such as coagulation disorders or obstructive jaundice, reflecting the presence of large lesions which had remained undetected over several years. Early detection of liver metastatic disease and eligibility for surgery have a determinant prognostic relevance, patients not eligible for operation having a median survival of 6 months. Therefore, it has been proposed to perform several tight follow-up schedules after treatment of primary tumors for an early detection of liver metastasis. These include the regular monitoring of liver enzymes, routine chest X-rays and ultrasound investigation of the liver and several newly developed tumor markers [1, 2]. Recent reports have shown that these follow-up methods have high specificity but not high sensitivity for the early detection of metastasis from choroidal cancer [1, 3]. To increase diagnostic accuracy, the routine use of PET-CT has been proposed as screening method for initial staging [4]. However, follow-up protocols after tumor treatment have to take into account the balance between the need for accurate diagnostic procedures, the burden for the patient including radiation exposure during imaging procedures and cost-effectiveness of screening methods. Future follow-up schedules will likely be based on both imaging techniques and biohumoral markers.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is being increasingly employed in the clinic, typical patterns of vascular uptake and washout of contrast medium allowing a clear advantage over conventional ultrasound in determining malignancy of lesions in the liver [5, 6, 7]. Up to date, no report has been published on the use of CEUS for the early detection of liver lesions from metastatic melanoma. We present the case of a 36-year-old patient who presented to our institution with a large metastatic lesion from a choroidal cancer in absence of symptoms and of liver enzyme elevations. Here, we describe CEUS features of liver metastasis and the correlation with other modern imaging methods, and propose the use of CEUS as a standard investigation method for the follow-up of patients affected by choroidal cancer.

Case Presentation

A 36-year-old patient presented to his general practitioner for a liver ultrasound investigation as routine follow-up procedure after treatment of a choroidal cancer in 1996. Examination showed a lesion of approximately 5 cm in size in liver segment VIII. The patient was thus admitted to our department for further investigation. The primary tumor had been treated by repeated ruthenium applications in 1996 and 2002. A laser treatment was also performed in 1997. Since the first diagnosis, the patient underwent regular ultrasound investigations of the liver and liver enzyme monitoring at 6 months intervals. Previous analyses had failed to show any signs of liver metastasis. As the patient presented to our institution, he did not report any relevant subjective complaints. Physical examination showed no pathological findings. Biochemical parameters, including liver function tests, liver enzymes as well as several tumor markers (AFP, CEA, CA19-9, chromogranin A), showed normal values. A conventional ultrasound investigation, CEUS, a CT and a MRI were performed after admission.

Conventional Ultrasound and CEUS

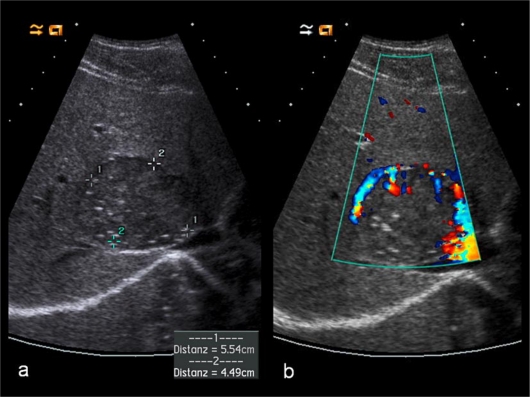

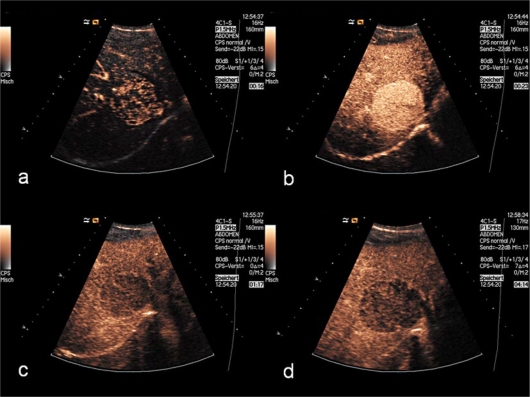

Ultrasound examination was performed using a high-end sonographic scanner (AcusonTM Sequoia 512; Siemens). The patient underwent a B-mode ultrasonographic and a color Doppler examination using a 4-MHz multifrequency convex transducer (fig. 1). The contrast-enhanced examination was performed with low-mechanical index (low-MI imaging, mean MI = 0.15) to avoid destruction of microbubbles in real-time tissue harmonic imaging (CadenceTM contrast pulse sequencing imaging on the ACUSONTM Sequoia 512 ultrasound system). A bolus injection of 2.0 ml of a second-generation blood pool contrast agent (SonoVue®; Bracco, Milan, Italy), consisting of stabilized microbubbles of sulfur hexafluoride, was administered into an antecubital vein through an 18-gauge needle and was followed by a flush of a 10-ml saline solution. The entire liver was scanned for 5 min in accordance with the maximum circulation time of the contrast agent (fig. 2). The examination was digitally stored on magnetic optical discs.

Fig. 1.

Baseline scan (a) showing a single isoechoic metastasis with maximum diameter of 5.5 × 4.5 cm in segment VIII. In color Doppler examination (b), the lesion shows some peripheral vascularity.

Fig. 2.

In the early arterial phase (a), 16 s after SonoVue injection, the lesion displays a strong enhancement, most of the liver parenchyma being only partially filled with contrast medium. During the arterial phase (b), the lesion shows a strong, homogenous enhancement. In the portal venous phase (c), there is partial washout of contrast medium from the lesion, here appearing hypo-enhancing compared to the homogenously enhancing normal liver. In the delayed phase (d), 4 min after injection of the contrast medium, the lesion shows a hypoechoic, sharply circumscribed punched-out enhancement defect.

MRI

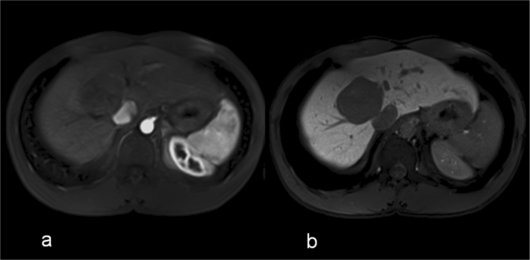

Standard MRI examination was performed on a 32-channel 1.5 T MR system (Magnetom Avanto; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). The MRI examination included native and T1-, T2-weighted and 3D gradient echo sequences for early dynamic imaging as well as for imaging of the liver specific phase. The slice thickness in these sequences was 3 mm in a single breath-hold examination that covers the entire liver. Gd-EOB-DTPA (Primovist; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) was administered as a bolus at a dose of 0.025 mmol/kg body weight via an antecubital i.v.-line (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hypovascular liver metastasis in the arterial (a) and hepatocyte phase (b) imaged by a T1-weighted 3D-gradient echo sequence after bolus injection of Gd-EOB-DTPA. In the hepatocyte phase (b), the margins of the lesions appear very clear and sharply delineated from increased contrast between the metastasis (no liver-specific uptake) and surrounding liver parenchyma (regular uptake).

MS-CT

After local anesthesia with 10 ml of Scandicain 2%, the patient underwent liver biopsy by CT-guided fluoroscopy using a 16-gauge/10-cm biopsy needle, on a 128-detector MDCT (Somatom Definition AS; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

In comparison to standard ultrasound (fig. 1), CEUS imaging allowed to readily recognize the morphology and the malignant features of the metastatic lesions due to early contrast medium uptake (fig. 2a, b) and by the rapid washout in the portal (fig. 2c) and late phase (fig. 2d). Due to the washout, the lesion appeared hypoechoic at CEUS compared to the normal liver parenchyma. The resulting reverse image was comparable to that obtained by MRI performed with liver-specific contrast medium, where the morphology of the lesion resulted from the lack of hepatocyte-specific contrast medium uptake (fig. 3).

A liver biopsy confirmed the suspicion of a liver metastasis from melanoma. The histological diagnosis was supported by typical morphological features as well as by positive staining for Melan A, HMB45 and S100 and by negative staining for KL1. Since the liver lesion was confined to the right liver lobe and did not show any signs of portal vein invasion, the patient underwent right partial hepatectomy with curative intention. The procedure was performed successfully and the patient was discharged shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Upon diagnosis of choroidal melanoma, the detection of concomitant metastatic lesions or the early recognition of metastasis occurring after treatment of the primary tumor has a major prognostic implication since in 80% of cases these lesions represent the only site of metastasis, and the median survival of patients not eligible for surgery is about 6 months [8]. Therefore, similarly to other malignancies preferentially causing metastasis in the liver, such as colon or breast cancer, early detection of liver lesions in the follow-up of choroidal cancer has important therapeutic and prognostic pitfalls [8].

Current protocols for the early detection of metastasis from choroidal carcinoma include regular monitoring of liver enzymes and ultrasound investigation of the liver. Upon detection of liver enzyme abnormalities or pathological findings at ultrasound, CT or MRI scans are usually performed [9]. However, it has recently been shown that liver ultrasound as well as elevated liver enzymes are of limited sensibility for the early detection of liver metastasis [3, 9]. The limits of these standard follow-up methods and the need of prolonged follow-ups are exemplified by the present case: the patient presented with a large metastatic lesion that had grown undetected over a long period of time in the absence of biochemical abnormalities or subjective complaints many years after the treatment of the primary tumor. In order to increase diagnostic accuracy, alternative methods besides conventional ultrasound and liver enzymes have been proposed. Recently, several biohumoral markers [2] or the utilization of PET-CT for the staging of choroidal melanoma [4] have been proposed, and their combined use might allow for earlier diagnosis of liver metastasis. However, follow-up methods after the diagnosis of choroidal cancer should possibly be not only accurate but also sustainable during a life-long follow-up with regard to risks connected with radiation exposure, patient compliance, availability and cost-effectiveness.

CEUS is being increasingly employed in the clinic for several diagnostic purposes and has proven particularly effective in discriminating between malignant and nonmalignant lesions [10]. In particular, it provides a significant advantage in the identification and the definition of the malignant character of liver tumor lesions [6]. Recently, we could also show that CEUS is more accurate than multislice computed tomography in the prediction of malignancy and benignity of liver tumors [7]. Moreover, evidence is accumulating on the fact that CEUS has a diagnostic reliability comparable to that of contrast-enhanced MRI with a liver-specific contrast agent, and an even higher diagnostic certainty of >90% compared with contrast-enhanced multidetector spiral CT [11, 12]. For the follow-up of patients, the employment of CEUS represents an alternative as feasible method for frequent and repeated investigations. Together with the increasing evidence on its diagnostic accuracy, reproducibility and availability as diagnostic tool, its cost-effectiveness and the lack of radiation burden make CEUS a possible candidate for the follow-up of patients after resection of choroidal cancers.

In summary, the case of a young patient presenting with a large metastatic lesion, occurring 13 years after diagnosis of choroidal melanoma, and no signs of liver enzyme elevation is representative of the need for an accurate diagnostic method as an alternative to those currently used. In this case report, we presented for the first time CEUS features of metastatic disease and proposed the employment of this method for the early detection of metastatic disease.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License (www.karger.com/OA-license), applicable to the online version of the article only. Distribution for non-commercial purposes only.

References

- 1.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, et al. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report 23. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2438–2444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barak V, Frenkel S, Kalickman I, et al. Serum markers to detect metastatic uveal melanoma. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1897–1900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks C, Foss AJ, Hungerford JL. Predictive power of screening tests for metastasis in uveal melanoma. Eye (Lond) 1998;12(Pt 6):945–948. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finger PT, Kurli M, Reddy S, et al. Whole body PET/CT for initial staging of choroidal melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1270–1274. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.069823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chami L, Lassau N, Malka D, et al. Benefits of contrast-enhanced sonography for the detection of liver lesions: comparison with histologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:683–690. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung EM, Clevert DA, Schreyer AG, et al. Evaluation of quantitative contrast harmonic imaging to assess malignancy of liver tumors: a prospective controlled two-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6356–6364. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clevert DA, Jung EM, Stock KF, et al. Evaluation of malignant liver tumors: biphasic MS-CT versus quantitative contrast harmonic imaging ultrasound. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:1195–1202. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damato B. Developments in the management of uveal melanoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2004;32:639–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eskelin S, Pyrhonen S, Summanen P, et al. Screening for metastatic malignant melanoma of the uvea revisited. Cancer. 1999;85:1151–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greis C. Ultrasound contrast agents as markers of vascularity and microcirculation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;43:1–9. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boozari B, Lotz J, Galanski M, et al. [Diagnostic imaging of liver tumours. Current status] Internist (Berl) 2007;48:8. doi: 10.1007/s00108-006-1773-x. 10-16, 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regge D, Campanella D, Anselmetti GC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of portal-phase CT and MRI with mangafodipir trisodium in detecting liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]