Abstract

Macfarlane Burnett stated in 1962 that “By the late twentieth century, we can anticipate the virtual elimination of infectious diseases as a significant factor in social life”. Probiotics have become of interest to researchers in recent times. Time has come to shift the paradigm of treatment from specific bacteria elimination to altering bacterial ecology by probiotics. The development of resistance to a range of antibiotics by some important pathogens has raised the possibility of a return to the pre-antibiotic dark ages. Here, probiotics provide an effective alternative way, which is economical and natural to combat periodontal disease. Thus, a mere change in diet by including probiotic foods may halt, retard, or even significantly delay the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases, promoting a healthy lifestyle to fight periodontal infections.

Keywords: Prebiotics, probiotics, symbiotic

INTRODUCTION

Mostly addressed as delicate microscopic speciality, periodontics has entered the saga of metamorphosis that explores and understands human body mechanisms at biomolecular levels. Altering the building blocks of life is a wise and precise way to correct flaws. There have been major shifts in treatment paradigm from nonspecific to specific approach. Now treatment options propose altering ecology of niches, in order to modify pathological plaque to a bioflim of commensalisms. Probiotics are live microorganisms administered in adequate amounts with beneficial health effects on the host.

Probiotics nano soldiers refer to genera of organisms, which play a crucial role in halting, altering, or delaying periodontal diseases. It poses a great potential in arena of periodontics in terms of plaque modification, halitosis management, altering anerobic bacteria colonization, improvement of pocket depth, and clinical attachment loss.

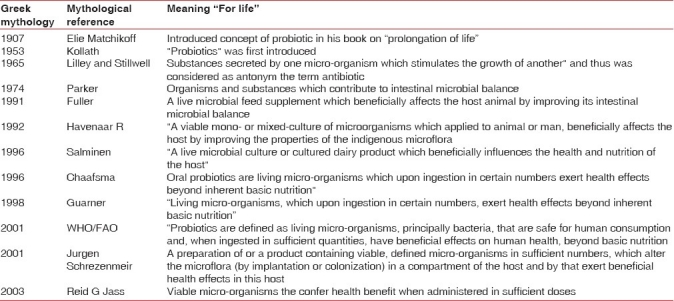

Probiotics are broadly categorised in two genus Lactobaccilus and Bifidobacterium. While other microorganisms also classified into this group includes yeast and moulds e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, Sochromyces boulardii. Probiotics have evolved for more than 10 decade back to present day. Elie Metchnikoff, introduced concept of probiotics in his book on “prolongation of life.” Various authors have then subsequently defined probiotics [Table 1].

Table 1.

Evolution in definition of probiotics

Proposed mechanics of probotics:

Various mechanisms have been proposed for probiotic actions. Probiotics have been documented to modulate host immunity both systemically and locally. Recently, “Oral lymphoid foci”[1] have been identified in interdental papillae, which provides site for local immune modulation. These were earlier thought to act on gastrointestinal tract mucosa only.

Probiotics stimulate dendritic cells (antigen presenting cells) resulting in expression of Th1 (T-helper cell 1) or Th2 (T-helper cell 2) response, which modulates immunity. Probiotics enhances innate immunity and modulate pathogen induced inflammation through “Toll-like receptors” on dendritic cell. Intracellular pathogens are phagocytosed by Th1 response, while extracellular pathogens are taken care by Th2 response. Probiotics can mimic response similar to a pathogen but without periodontal destruction.

Other proposed mechanisms include Glycoprotein – carbohydrate cell surface interaction mediate by inter species interactions.[2] Similarly, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus acidophilus co-aggregate with Fusobacterium nucleatum. Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Lactobacillus paracasei have strong binding activity to primary pellicle. Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus casei shirota, Lactobacillus casei ATCC 11578 prevent adherence of bacteria to salivary pellicle by altering its composition.

Aggregation alteration is another important proposed mechanics as Hetrofermentative Lactobacillus is the strongest inhibitor of Aggregatibacter actinomycetem comitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia.[3] Fusobacterium nucleatum aggregate with Weissella ciberia[4] in preference to Treponema denticola and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Lactobacillus rhamnosus co-aggregates with Fusobacterium nucleatum.

Weissella cibaria isolates generated a substantial quantity of hydrogen peroxide, which was sufficient to inhibit the proliferation of Fusobacterium nucleatum.[4]

Apoptosis is yet another proposed mechanism. Probiotics stimulate apoptosis of tumor cells through end product formation.[5] It has also reported to inhibit apoptosis of mucosal cells.[6]

Probiotic mixture has also been reported to protect epithelium barrier by maintaining tight junction protein expression and prevent apoptosis of mucous membrane.[7]

The oral anerobic bacteria exhibit a higher degree of susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide than do other genera of aerobic or facultative anerobic bacteria.

Decrease in pro inflammatory cytokines by probiotics ingestion is another mode of action as seen in gingival crevicular fluid GCF of patient on chewing gum containing Lactobacillus reutri.[3]

Lactobacillus salivaris and Lactobacillus gasseri show strong inhibition of periopathogenic bacteria.[8] Secretion of bacteriocins by Lactobacillus reutri, e.g., reutrin and reutricyclin inhibits growth of pathogens and has high affinity for host tissue and has anti- inflammatory effect by inhibition of proinflamatory mediators[9] similarly Weissella ceberia releases catalase.[4]

Probiotics in periodontal disease

Porphyromonas gingivalis, Aggeratibacter actinomycetem comitans, Tanirella forsythus, and Treponema denticola are established periopathogens covering red and green complex of Socransky colour coding.

Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus uberis have reported to inhibit the growth of pathogens both in the laboratory and animal models. They are indicators of healthy periodontium. When these bacteria are absent from sites in the periodontal tissues, those sites become more prone to periodontal disease.[10]

Recently, various studies have reported lactic acid inhibition of oral bacteria suggesting a promising role in combating periodontal diseases.

Lactobacillus reuteri was evaluated by Krasse et al.[11] in recurrent gingivitis case. A parallel, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with 59 patients having moderate-to-severe gingivitis were taken up. Lactobacillus reuteri strains were administered via chewing gum twice a day for 2 weeks at a concentration of 1×108 CFU (colony forming unit) along with Scaling and root planning. After 2 weeks, the clinical parameters were improved in group consuming probiotics chewing gum.

In a one-way crossover, open-label placebo-controlled study Kang et al.[12] included 72 volunteers. Subjects rinsed in morning twice with 15 ml rinse containing probiotics strain. Rinsing was repeated in the afternoon and in the evening, after brushing. There was a significant, 20% reduction in plaque scores when the Weissella cibaria CMS1-containing rinse was used. These results indicate that the Weissella cibaria isolates possess the ability to inhibit biofilm formation.

Another parallel open label placebo controlled study by Hillman et al. on 24 gnotobiotic rats, including single baseline application resulted significant decrease levels of Aggregatebacter actinomycetum comitans when compared with placebo groups.[13]

Another study by Grudianov et al. using mixture of probiotics also reported improvement of clinical sign of gingivitis. Probiotics have also been employed as antimutagenic and anticarigenic agents.[14]

Recently, an in vitro study done by Nara et al. on Lactobacillus helveticus demonstrated release of short peptide stimulate osteoblast to promote bone formation, thus proposing important role in repair of periodontal bone destruction. Increase in remission period upto 10–12 weeks was reported in periodontal dressing containing Lactobacillus casei was reported by Volozhin.

A parallel open label study by Ishikawa enrolled 84 subjects; consuming tablets containing Lactobacillus salivaris T1 2711 strain 5 times a day for 8 weeks resulted in decrease in black pigmented anerobic rods. A similar study by Matsuka reported decrease bleeding on probing and decrease in Porphyromonas gingivalis count.[15]

A study done on release of pro inflammatory cytokine on Lactobacillus brevis by Ricca et al. and Lactobacillus reutri by Svante Twetman et al. showed decreased levels, improving the clinical signs of gingivitis.

Teughels et al. conducted a split mouth design study on 32 beagle dogs with artificially created pockets, bacterial pellets Streptococcus sanguis KTH-4, Streptococcus salivarius TOVE, and Streptococcus mitis BMS were applied locally in designated periodontal pockets at baseline, 1, 2, and 4 weeks, result showed decrease in anerobic bacteria and Campylobacter rectus with decrease pocket recolonization and bleeding on probing when compared with controls.[16]

Acilact, a Russian probiotic preparation of a complex of five live lyophilized lactic acid bacteria, is claimed to improve both clinical and microbiological parameters in gingivitis and mild periodontitis patients.[17]

Halitosis management

Volatile sulphur compounds (VSC) are responsible for halitosis. Bacteria responsible for VSC production are Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Treponema denticola. A probiotic strain (Weissella cibaria) possesses the ability to inhibit VSC production under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. It possesses great potential as novel probiotic for use in the periodontium. Co-aggregation of Fusobacterium nucleatum with other periopathogens results in secondary colonization of biofilm and contributes substantially to VSC production in the oral cavity.[18]

Hydrogen peroxide has been implicated in maintenance of a stable ecological system, and protecting against invading pathogens. Hydrogen peroxide is known to reduce concentrations of sulphur gas significantly in vivo. Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei have been determined to inhibit the in vitro proliferation of anerobic bacteria via the production of a strong acid.[18] The Weissella cibaria isolates resulted in a higher ecological pH than that which would normally be observed in conjunction with Lactobacilli[4] encouraging with regard to the utility of this species within the context of probiotic use. Streptococcus salivaris produces bacteriocins, which inhibit bacteria producing VSC. Recently, in a study it was shown that lozenges and gum containing Streptococcus salivaris decrease VSC in halitosis patients.[9]

Probiotics in general use

Proven indication

Rota virus diarrhoea

Reduction of antibiotic associated side effect

Possible indication

Dental caries and periodontal health

Food allergies and lactose intolerance

Atopic eczema

Prevention of vaginitis

Urogenital infections

Irritable bowel disease

Cystic fibrosis

Traveller's diarrhoea

Enhance oral vaccine administration

Helicobacter pylori infection

Various cancers

Natural options

Nature has a huge source of pro- and pre-biotic food.

Probiotics: fermented vegetables dishes like Sauerruben (turnips) and sauerkraut (cabbage), are quite popular in north Europe. Kombucha, a fermented tea thought to originate in Russia or China, is another great source of beneficial bacteria that is also dairy-free. Water kefir, alternatively known as tibicos and Japanese water crystals, is a probiotic beverage similar to Kombucha and Ginger Beer (traditional symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeasts and with powdered ginger and sugar). Moroccan preserved lemons are naturally fermented without the use of a starter. Coconut kefir is a probiotic beverage prepared from young coconut water and a starter culture. Sour pickles are the traditional alternative to vinegar pickles and are prepared using a simple solution of unrefined sea salt and clean, chlorine-free water encouraging the growth of lactobacillus, which customarily outcompete pathogenic bacteria. Other sources include dairy products. Recently, hisayama study showed that daily intake of dairy product containing lactic acid is good for periodontal health.[19]

Prebiotics: “A prebiotic is a selectively fermented ingredient that allows specific changes, both in the composition and/or activity in the gastrointestinal microflora that confers benefits upon host well-being and health.”[20] They are termed as functional food not destroyed while cooking. Traditional dietary sources of prebiotics include soybeans, inulin sources (such as Jerusalem artichoke, jicama, and chicory root), raw oats, unrefined wheat, unrefined barley, and yacon. Roberfroid, states that only two specific fructo oligosaccharides – oligofructose and inulin - meet his seminal definition of “Prebiotic.” Some prebiotics may act as a bifidogenic, i.e., promoting bifidobacteria growth factor and vice versa, but the two concepts are not identical.

Short-chain prebiotics, e.g., oligofructose act on right side of the colon providing nourishment to the bacteria in that area. Longer-chain probiotics, e.g., Inulin, are predominantly in the left side of the colon. Full-spectrum prebiotics act throughout the colon, e.g., oligofructose-enriched inulin (OEI). The majority of research done on prebiotics is based on full-spectrum prebiotics, typically using OEI as the research substance.[20] Genetically engineering plants for the production of inulins has also become more prevalent[21] despite the still limited insight into the immunological mechanisms activated by such food supplementation.

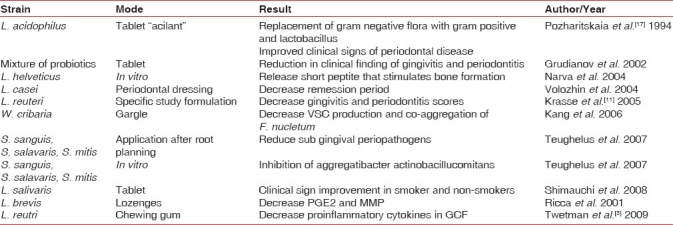

Synbiotics: As probiotics are mainly active in the small intestine and prebiotics are only effective in the large intestine, the combination of the two may give a synergistic effect. Appropriate combinations of prebiotics and probiotics are synbiotics.[22] Various preparations have been tried in periodontal context with certain amount of clinical success, these trials supports the use of probiotics in field of periodontics [Table 2].

Table 2.

Periodontal clinical studies done on probiotics

Safety concerns and dosage

Probiotics organisms are classified by FDA as generally regarded as safe (GRAS).

Criteria of an ideal microorganism used as probiotics.[23]

High cell viability, resistant to low ph and acids

Ability to persist

Adhesion to cancel the flushing effect

Able to interact or to send signals to immune cells

Should be of human origin

Should be non pathogenic

Resistance to processing

Must have capacity to influence local metabolic activity

Studies on commercial preparations have reported probiotics on label were not matching with the contents, in commercial products misidentification of probiotics bacteria is common. Lactobacillus acidophilus in many commercial preparations either has no active species or had other species. Another important concern is dose of probiotics required for adequate action; various studies have reported different values, 1×108-10, 1×109-10, 1×1010-11.[23]

Some cases of bacteraemia and fungenaemia have been reported in immunocompromised individuals in gut syndrome and chronic diseases.[8]

Lactobacillus endocarditis have been reported after dental treatment in a patient taking Lactobacillus rhamnosus.[24]

Reported cases of infection are extremely rare accounting to 0.05–0.4% of infective endocarditis and bacteraemia.[24] Liver abscess was reported in an individual on Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.[25]

Concerns have been raised for lifelong use of probiotics on having adverse effect on risk group, though risk group have not been identified. Stimulation of immune system by probiotics could prove to show degradation in autoimmune diseases, and they could transfer antibiotic resistance to pathogens.[23]

Probiotic are supplied along with prebiotic in form of powder sachet, gelatine capsules, or suspension. “BION” commercially available in Indian market (combination of pre- and pro-biotic) has 0.48 billon spores of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococus thermophilus, and 0.10 billon spores of Saccharomyces boulardii along with 300 mg of fructo-oligosaccharides, is prescribed as single dose daily before meals in the morning.

Designer probiotics

The term “Patho-Biotechnology” was introduced by Sletor and Hill. It comprises of three basic approaches

Use of attenuated bacterial pathogens as vaccine

Isolation and purification of pathogen specific immunogenic protein for direct application

Equipping probiotics bacteria with genetic element necessary to overcome stress outside host, inside host and antagonise invading pathogens

Third approach is what is termed as “designer probiotics”. This approach employs probiotics to be engineered to express receptor mimic structures on their surface few studies done are limited to gut, periodontal studies are lacking, but poses a great potential in this field to develop. Designer probiotics have been employed in treatment of HIV, also employs as a novel vaccine delivery vehicle. Improving the stress tolerance profile of probiotic cultures significantly improves tolerance to processing stress and prolongs survival during subsequent storage. This in turn contributes to a significantly larger proportion of the administered probiotics would reach the desired location (e.g., the gastrointestinal tract/periodontium) in a bioactive form.[26]

Replacement therapy

The term replacement therapy (also called bacteriotherapy or bacterial interference) is sometimes used interchangeably with probiotics.[27]

But it differs from probiotics in following:

Effector strain is not ingested and is applied directly on the site of infection.

Colonization of the site by the effector strain is essential.

Involves dramatic and long-term change in the indigenous microbiota and is directed at displacing or preventing colonization of a pathogen.

Have a minimal immunological impact.

While on other hand Probiotics are generally used as:

Dietary supplements and are able to exert a beneficial effect without permanently colonizing the site.

Rarely dramatic and long-term microbiological change.

Exerts beneficial effects by influencing the immune system.

Teughels et al. employed this term as probiotics and conducted studies, with application of Streptococcus salivaris, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus sanguis, repeatedly on root surfaces after scaling and root planning have resulted decrease number of periopathogens.[16] It refers to the basic idea of replacing pathogenic bacteria by supplying commensalisms, which have same affinity for tooth surface adherence.

CONCLUSION

Probiotics are counterparts of antibiotic thus are free from concerns for developing resistance, further they are body's own resident flora hence are most easily adapted to host. With fast evolving technology and integration of biophysics with molecular biology, designer probiotics poses huge opportunity to treat diseases in a natural and non invasive way. Periodontitis have established risk of various systemic diseases like diabetes, atherosclerosis, hyperlipedemia, chronic kidney diseases, and spontaneous preterm birth.

Thus, a critical need to establish good periodontal health for attaining good systemic health is of utmost importance and probiotics are promising, safe, natural, and side effects-free option, which are required to be explored in depth for periodontal application. Advances and accomplishments attained give us the ability to employ these friendly bacteria (probiotics) as nano soldiers in combating periodontal diseases. Despite great promises, probiotics works are limited to gut. Periodontal works are sparse and need validation by large randomized trials. It can be said probiotics are still in “infancy” in terms of periodontal health benefits, but surely have opened door for a new paradigm of treating disease on a nano – molecular mode.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cutler CW, Jotwani R. Dendritic cells at the oral mucosal interface. J Dent Res. 2006;85:678–89. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimaudo NJ, Nesbitt WE. Coaggregation of candida albicans with oral fusobacterium species. Oral Microbial Immunol. 1997;12:168–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twetman S, Derawi B, Keller M, Ekstrand K, Yucel-Lindberg T, Stecksen-Blicks C, et al. Short term effect of chewing gum containing probiotics lactobacillus reutri on levels of inflammatory mediators in GCF. Acta Odontol Scand. 2009;67:19–24. doi: 10.1080/00016350802516170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang MS, Kim BG, Chung J, Lee HC, Oh JS. Inhibitory effect of Weissella cibaria isolates on the production of volatile sulphur compounds. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:226–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyer C, Kosters A, Sethi G, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB, Versalovic J. Probiotic lactobacillus reuteri promotes TNF-induced apoptosis in human myeloid leukemia-derived cells by modulation of NF-kappaB and MAPK signalling. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1442–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan F, Polk DB. Probiotic bacterium prevents cytokine-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50959–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mennigen R, Nolte K, Rijcken E, Utech M, Loeffler B, Senninger N, et al. Probiotic mixture VSL#3 protects the epithelial barrier by maintaining tight junction protein expression and preventing apoptosis in a murine model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1140–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90534.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [last cited on 2010 May 25]. Available from: http://www.journaloforalmicrobiology.net/index.php/jom/article/view Article/1949/2256 .

- 9. [last cited on 2010 May 25]. Available from: http://www.cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-75/issue-8/585.pdf .

- 10.Hillman JD, Socransky SS, Shivers M. The relationships between streptococcal species and periodontopathic bacteria in human dental plaque. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30:791–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krasse P, Carlsson B, Dahl C, Paulsson A, Nilsson A, Sinkiewicz G. Decreased gum bleeding and reduced gingivitis by the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. Swed Dent J. 2005;30:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang MS, Chung J, Kim SM, Yang KH, Oh JS. Effect of Weissella cibaria isolates on the formation of Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Caries Res. 2006;40:418–25. doi: 10.1159/000094288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillman JD, Shivers M. Interaction between wild-type, mutant and revertant forms of the bacterium Streptococcus sanguis and the bacterium Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in vitro and in the gnotobiotic rat. Arch Oral Biol. 1988;33:395–401. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(88)90196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [last cited on 2010 May 25]. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/content/31h148h666j508u1/

- 15.Matsuoka T, Sugano N, Takigawa S, Takane M, Yoshinuma N, Ito K, et al. Effect of oral Lactobacillus salivarius TI 2711 administration on periodontopathic bacteria in subgingival plaque. Jpn Soc Periodontol. 2006;48:315–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teughels W, Newman MG, Coucke W, Haffajee A, Van DerMei HC, Haake SK, et al. Guiding periodontal pocket recolonization: A proof of concept. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1078–82. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pozharitskaia MM, Morozova LV, Melnichuk GM, Melnichuk SS. The use of the new bacterial biopreparation Acilact in the combined treatment of periodontitis. Stomatologiia (Mosk) 1994;73:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimazaki Y, Shirota T, Uchida K, Yonemoto K, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, et al. Intake of dairy product and periodontal diseases: The hisayama study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:131–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [last cited on 2010 May 25]. Available from: http://www.jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/abstract/137/3/830S .

- 20.Ritsema T, Smeekens SC. Engineering fructan metabolism in plants. J Plant Physiol. 2003;160:811–20. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleessen B, Hartmann L, Blaut M. Oligofructose and long-chain inulin: Influence on the gut microbial ecology of rats associated with a human faecal flora. Br J Nutr. 2001;86:291–300. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J.Nutr. 125:1401–12. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackay AD, Taylor MB, Kibbler CC, Hamilton-Miller JM. Lactobacillus endocarditis caused by a probiotic organism. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:290–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rautio M, Jousimies-Somer H, Kauma H, Pietarinen I, Saxelin M, Tynkkynen S, et al. Liver abscess due to a Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain indistinguishable from L. rhamnosus strain GG. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1159–60. doi: 10.1086/514766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anuradha S, Rajeshwari K. Probiotics in health and disease. Jounal,Indian academy of clinical medicine. 2005;6:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sleator RD, Hill C. Patho-biotechnology; using bad bugs to make good bugs better. Sci Prog. 2007;90:1–14. doi: 10.3184/003685007780440530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson M. Manipulation of the indigenous microbiota. In: Wilson M, editor. Microbial inhabitants of humans. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 395–416. [Google Scholar]