Abstract

Background:

Dental biofilm harboring oral bacteria is highly correlated with the progression of dental diseases. The existence of micro organisms as polyspecies in an oral biofilm and dental plaque has profound implications for the etiology of periodontal disease. The adhesion of streptococci to the tooth surface is the first step in the formation of dental plaque. Antiadhesive agents which can disrupt the biofilm formation can be an effective alternative to antibacterial therapy.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 10 patients both male and female between the age group of 20–40 years were included in the study. Plaque samples were taken and subjected to culturing on rabbit's blood agar plate for the growth of streptococci colonies for 24–48 h. The streptococci colonies were identified and was further subjected to subculturing for 24–48 h with disc containing ethyl alcohol+cranberry extract (Group A) and water+cranberry extract (Group B). Both these groups A and B were further divided into subgroups I, II, III, IV, and V according to concentration 1:2, 1:4, 1:40, 1:100 and 1:600 respectively.

Results:

Zone of inhibition of Group A with subgroup I disc was 2 mm. while with subgroups II, III, IV, V disc was 4mm. Whereas the zone of inhibition seen of Group B was same (2mm) in subgroups I, II, III, IV discs however a significant zone of inhibition (10mm) was observed in subgroup V disc.

Conclusion:

Cranberry juice (active ingredient: Non dialyzable material) inhibits the adhesion and reverses the coaggregation of various oral micro organisms. The present study revealed that cranberry gel in highly concentrated (1:600) form has an inhibitory effect on the colonization of the streptococci species, and thus can be beneficial in the inhibition of dental plaque formation.

Keywords: Anti-adhesion, biofilm, cranberry juice [NDM], Streptococci species

INTRODUCTION

Inhibition of bacterial colonization is vital for the prevention of chronic oral infectious diseases caused by dental plaque bacteria.[1] Several methods of interfering with the accumulation of bacteria in biofilm have been done. Anti adhesion compounds that prevent bacterial accumulation from or initiate detachment from the oral surfaces and reducing the biofilm mass has shown significant results.[2–4] This approach has many advantages, as almost no bacterial resistance is encountered, as seen in other antibacterial or antibiotic treatments. Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the genus Vacciniu m subgenus Oxycoccus, or in some treatments, in the distinct genus Oxycoccus. It is found in acidic bogs throughout the cooler parts of the Northern Hemisphere including northern Europe, northern Asia and America. It has small 5–10 mm leaves. The flowers are dark pink, with a purple central spike, produced on fine hairy stems [Figure 1]. The fruit is a small pale pink berry, with a refreshing sharp acidic flavor.

Figure 1.

Showing cranberries (group of evergreen dwarf shrubs)

The name cranberry derives from “craneberry”, first named by early European settlers in America who felt that the expanding flower, stem, calyx, and petals resembled the neck, head, and bill of a crane (bird). Cranberries are a major commercial crop in certain US states and Canadian provinces. Most cranberries are processed into food products such as juice, sauce, and sweetened dried Cranberries and can be added in soups and stews.[5]

The high molecular weight non dialyzable material (NDM) an active ingredient of cranberry juice has shown to reverse the co aggregation of the majority of bacterial pair, it exhibits tannin-like properties and is highly soluble in water. Further, it is devoid of proteins, carbohydrates and fatty acids and contains 56.6% carbon and 4.14% hydrogen. Precoatings of the bacteria with NDM have shown to reduce their ability to form biofilm.[2] Cranberries are a source of polyphenols antioxidants and phytochemicals and is under active research for possible benefits to the cardiovascular system, immune system and as anti-cancer agents.[6,7]

Cranberry juice contains a chemical component that is able to inhibit and even reverse the formation of plaque by Streptococcus mutans pathogens that cause tooth decay. The juice components are also effective against formation of kidney stones[8,9] Cranberry fruit is a rich source of polyphenols, and has shown biological activities against Streptococcus mutans.The influence of extracts of flavonols (FLAV), anthocyanins (A) and proanthocyanidins (PAC) from cranberry on virulence factors involved in Streptococcus mutans biofilm development and acidogenicity. PAC and FLAV, alone or in combination, inhibited the surface-adsorbed glucosyltransferases and F– ATPases activities, and the acid production by S. mutans cells. Furthermore, biofilm development and acidogenicity were significantly affected by topical applications of PAC and FLAV (P<0.05). Proanthocyanidins and flavonols are the active constituents of cranberry against S.mutans.[3] NDM containing mouthwash showed a significant reduction in the salivary streptococcus mutans and total bacterial count.[10]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The purpose of this study was to investigate the inhibitory effects of cranberry juice on the adherence of oral streptococci on biofilm formation.

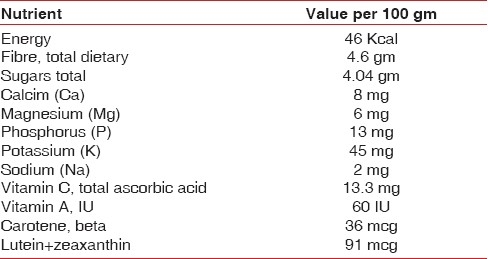

Nutrient and antioxidant capacity

Cranberries have moderate levels of vitamin C, dietary fiber and the essential dietary mineral, manganese, as well as a balanced profile of other essential micronutrients [Table 1].

Table 1.

Nutrient and anti-oxidant capacity of cranberry

Preparation of cranberry juice

Cranberry pure extract*, was dissolved in sterile water and 70% ethyl alcohol. The extract was mixed till it dissolved completely and a homogenous solution was formed and gel was obtained subsequently. Cranberry extract was measured according to the concentration required from 2 mg weight to 600 mg weight and was dissolved in appropriate quantity of water and ethyl alcohol.

* Cranberry fruit extract, –Superdrug Stores, Croydon, U.K.

Method of collection of plaque

The patient was asked to rinse thoroughly and a jet of water spray was used to eliminate any debris present on the tooth surface. The plaque samples were subsequently obtained from patients suffering from chronic gingivitis utilizing disposable sterile cotton swabs [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Disposable sterile cotton swabs

Since the study was conducted to check the inhibitory effect of cranberry juice on streptococci species, these organisms were cultured on blood agar plates in the Department of Pathology and Microbiology of U.P. Dental College and Research Centre, Lucknow.

Preparation of blood agar plate

Ten blood agar plates were made. Nutrient agar (7 gm) was boiled in 250 ml of sterile water, to mix it completely. After a homogenous solution was prepared, this solution was autoclaved. The nutrient agar solution was allowed to cool. The flask was swirled to mix the solution thoroughly and to avoid the formation of bubbles and froth on the surface, and dispensed into sterile plates. Cooling the agar and warming of the blood are essential steps of this procedure because agar if hot can damage red blood cells, and cold blood can cause the agar to gel before pouring [Figure 3]. Ten percent (1.5–2 ml) of rabbit's blood was mixed in the nutrient agar (15–20 ml) for each plate of blood at 35°C. They were further stored in a refrigerator. Before inoculation these plates were kept in an incubator such that they are completely dry [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Nutrient agar (cooled till temperature 35°C)

Figure 4.

Blood agar plate

The plaque samples which were taken from the patients were inoculated on ten blood agar plates and incubated in an incubator at 37°C for 24 –48 h.

Identification of Streptococci

Results showed well formed colonies on the agar plate [Figure 5]. The streptococcus colonies (pin point head) were diagnosed by Lance Field Test. These colonies were then picked up with the help of a sterile loop and were sub cultured on another blood agar plate.

Figure 5.

Streptococci colonies

Two groups of discs were formed. Group A discs contained ethyl alcohol with different concentration of cranberry extract and Group B discs contained water with different concentration of cranberry extract They were further divided into subgroups I, II, III, IV, V according to different concentrations and these discs were subsequently placed on the two sub cultured plate with their controls. These plates were further subjected to incubation at 37°C for 24–48 h and results so obtained were observed.

†- Disposable sterile cotton swabs, Clone Bio System Pvt Ltd, Human Diagnostics, Calcutta, India.

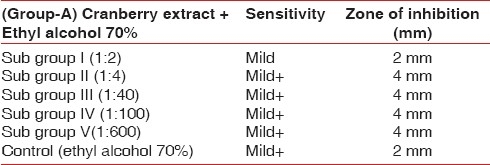

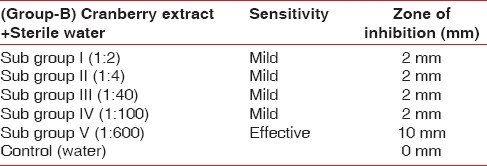

RESULTS

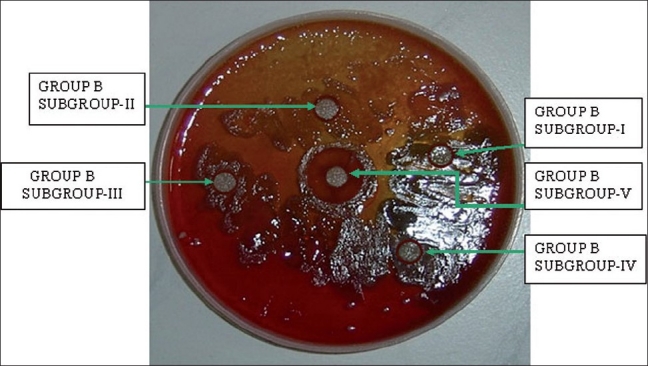

To investigate the effect of cranberry juice on biofilm, streptococci species were treated with Group A with subgroups I, II, III, IV, V and control revealed inhibitory zones of 2, 4, 4, 4, 4, 2 mm respectively [Table 2]. Group B [Table 3] with subgroups I, II, III, IV revealed mild inhibitory zone of 2 mm as seen on the blood agar plate which was not effective for the inhibition of biofilm formation. Control (water) showed 0 mm zone of inhibition, whereas highly concentrated cranberry gel form of 1:600, i.e. subgroup V showed an inhibitory zone of 10 mm. This finding was significant since it showed that Streptococci was exposed to increased concentration of NDM in the cranberry juice there was a pronounced reduction in the bacterial density [Figure 6].

Table 2.

Results showing zone of inhibition in mm after using discs containing different concentrations of cranberry extracts in ethyl alcohol

Table 3.

Results showing zone of inhibition in mm after using discs containing different concentrations of cranberry extracts in water

Figure 6.

Blood agar plate which had undergone subculturing of streptococci species with placement of discs with different concentrations of cranberry extract in water and in highly concentrated gel form is showing the largest zone (10 mm) of inhibition of Streptococci species

DISCUSSION

Cranberry juice has been used in herbal medicine as an anti-infection agent, especially for urinary tract infections. The NDM of the cranberry juice is highly soluble in water, devoid of proteins, carbohydrates and fatty acids[11] and has an anti-coaggregation effect[1] is anti-enzymatic[10] and promotes reduction of cariogenic bacteria in vivo.[12] Some researchers have focused on polymers, such as polyvinylmethylethyl maleic acid copolymer[13] which act as an antiadhesive agent. Three classes of anti-adhesion agents were proposed in the literature[3] receptor analogues, anti-adhesion antibodies and adhesin analogues. According to our results, NDM acts as an anti-biofilm agent by affecting biofilm formation and disrupting existing biofilms. Howell et al. found that high molecule mass proanthocyanidine (condensed tannin) from cranberry juice prevented the expression of the P–fimbria of the E-scherichia –coli and inhibited its adherence activity.[14]

Rabbit's cited blood was taken, which had 10% sodium citrate to prevent coagulation. Rabbit blood was utilized since they do not have antibodies against diseases like humans and hence, the micro organism can grow flawlessly. Human blood is also discouraged because of the increased possibility of growth of human blood–borne pathogens such as HIV or hepatitis making the identification of particular species difficult.[15]

Group A discs with subgroups I, II, III, IV, V, control and Group B discs with subgroups I, II, III, IV revealed mild zone of inhibition of 2 mm. whereas Group B subgroup V showed significant zone of inhibition of 10 mm, which can be effective in inhibiting and reversing the co-aggregation of oral microorganisms. Control Group B showed 0 mm zone of inhibition as seen on the blood agar plate since water itself do not have any anti bacterial properties. Ethyl alcohol itself is an anti bacterial agent and showed some degree of inhibition, i.e., 2 mm, therefore, attributing to zone of inhibition to some extent in Group A subgroup II, III, IV, whereas subgroup V was not effective at all since the solubility of cranberry extract in ethyl alcohol was not as fine as in water.[2]

Cranberry juice has been demonstrated to inhibit the adherence of some bacteria. The present study revealed that the cell surface hydrophobicity of some oral streptococci was reduced by the addition of the cranberry juice and that the reduction was dependent on the concentration of the juice. It is probable that the cranberry juice components bond to and or mask the hydrophobic protein(s) on the cell surface of oral Streptococci.

The high molecular weight constituent of cranberry juice inhibited the growth of oral streptococci in vitro suggesting that it can have an inhibitory effect in the formation of plaque biofilm since the streptococcus species are the initial colonizers, which are crucial for biofilm formation. Bacteria, especially those immobilised in biofilm, are the foremost perpetrators of oral disease.[12–14] Until date, in addition to mechanical means, the reduction in the number of bacteria is achieved mostly by the use of antibacterial agents.[16] However, the antibacterial agents may exert a selective ecological pressure, causing a shift in microbial population, which would affect the delicate balance in the oral environment ecosystem resulting in secondary infections. Although these agents are effective, the primary concern is the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria, which may lead to treatment failure and increased medical outlay. Yet, very few new classes of anti- biofilm agents are currently being developed. Initiating detachment or affecting bacterial adhesion appears to be a promising approach to controlling diseases associated with biofilm formation.[10,16–18] Milk constituents[19] low molecular weight chitosan,[2] and antibacterial agents at sub-inhibitory– concentrations[20] were found to promote detachment of bacteria from biofilm. Other researchers have focused on polymers, such as polyvinylmethylether maleic acid copolymer,[13] which act as an anti-adhesive agent. It has also been suggested that detachment of oral bacteria from biofilm results from enzymatic activity.[21]

The present study revealed that cranberry gel in highly concentrated (1:600) form has an inhibitory effect on the colonization of the Streptococci species, which can be beneficial in the reticence of the formation of dental plaque. The cranberry non dialyzable material (NDM) also seems to affect the phosphorylation and expression of various intracellular proteins that are implicated in MMP production thus can be exploited as an anti-biofilm agent. Our results strongly suggest that this cranberry fraction may act notably via a down regulation of activator protein-1 activity, leading to the inhibition of MMP production. Therefore concentrated cranberry juice/mouth washes can be utilized as a preventive agent for biofilm formation.

However, additional studies are required to identify the exact mechanism of action of the cranberry nondialyzable material[22]

Acknowledgments

For this study, I would thank my Professor and Head of the Department Dr. Vivek Govila for his guidance and support which was very vital in the making of this study. Also, I would thank the Department of Pathology and Microbiology of U.P. Dental College and Research Center for conducting the study. My great regards to Dr. Mridul Mehrotra (Professor of Microbiology) for giving his guidance for the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiss EI, Lev-Dor R, Kashamn Y, Goldhar J, Sharon N, Ofek I. Inhibiting interspecies coaggregation of plaque bacteria with cranberry juice constituent. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1719–23. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ofek I, Hasty DL, Sharon N. Anti-adhesion therapy of bacterial diseases: Prospects and problems. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;38:181–91. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly CG, Younson JS. Anti-adhesive strategies in the prevention of infectious disease at mucosal surfaces. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:1711–21. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvin RT, Bautista DL. Hope for the post-antibiotic era? Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:20. doi: 10.1038/5189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The American Cranberry-Basic Information on Cranberries. Library.wisc.edu. [last retrieved on 2009 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.library.wisc.edu/guides/agnic/cranberry/faq.htm .

- 6.Seifried HE, Anderson DE, Fisher EI, Milner JA. A review of the interaction among dietary antioxidants and reactive oxygen species. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:567–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halliwell B. Dietary polyphenols: Good, bad, or indifferent for your health? Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McHarg T, Rodgers A, Charlton K. Influence of cranberry juice on the urinary risk factors for calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. BJU Int. 2003;92:765–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler T, Jansen B, Hesse A. Effect of blackcurrant-, cranberry- and plum juice consumption on risk factors associated with kidney stone formation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1020–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg D. Studying plaque biofilms on various dental surfaces. In: An YH, Friedman RJ, editors. Handbook of bacterial adhesion: Principles, methods, and applications. NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 353–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ofek I, Goldhar J, Sharon N. Anti-Escherichia coli adhesin activity of cranberry and blueberry juices. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;408:179–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0415-9_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss EI, Kozlovsky A, Steinberg D, Lev-Dor R, Bar Ness Greenstein R, Feldman M, et al. A high molecular mass cranberry constituent reduces mutans streptococci level in saliva and inhibits in vitro adhesion to hydroxyapatite. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;232:89–92. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(04)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan YH, de Graaf T, Lath DL, Humphreys SM, Marlow I, Brook AH. Selection of oral microbial adhesion antagonists using biotinylated Streptococcus sanguis and a human mixed oral microflora. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell AB, Vorsa N, Der Marderosian A, Foo LY. Inhibition of the adherence of p-fimbriated Escherichia coli to uroepithelial cell surface by proanthocyanidin extracts from cranberries. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1085–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerhardt, Philipp, Murray RG, Willis A, Wood, Krieg NR. Washington, D. C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. Methods for General and Molecular Bacteriology; p. 619. (642, 647). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ofek I, Goldhar J, Zafriri D, Lis H, Adar R, Sharon N. Anti-Escherichia Coli adhesin activity of cranberry and blueberry juices. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1599. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105303242214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liljemark WF, Bloomquist C. Human oral microbial ecology and dental caries and periodontal diseases. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1996;7:180–98. doi: 10.1177/10454411960070020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsh PD, Bradshaw DJ. Microbial community aspects of dental plaque. In: Newman H, Wilson M, editors. Dental plaque revisited oral biofilms in health and disease. Cardiff, UK: Bioline; 1999. pp. 237–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharon N, Ofek I. Safe as mother's milk: Carbohydrates as future anti-adhesion drugs for bacterial diseases. Glycoconj J. 2000;17:659–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1011091029973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai S, Simionato MR, Mayer MP, Novo NF, Zelante F. Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of chemical agents on hydrophobicity and in vitro adherence of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis. Caries Res. 1994;28:335–41. doi: 10.1159/000261998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan JB, Ragunath C, Ramasubbu N, Fine DH. Detachment of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans biofilm cells by an endogenous beta-hexosaminidase activity. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4693–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4693-4698.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarsi R, Muzzarelli RA, Guzman CA, Pruzzo C. Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans adsorption to hydroxyapatite by low-molecularweight chitosans. J Dent Res. 1997;76:665–72. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]