Abstract

We have implemented an aldol-based ‘build/couple/pair’ (B/C/P) strategy for the synthesis of stereochemically diverse 8-membered lactam and sultam scaffolds via SNAr cycloetherification. Each scaffold contains two handles, an amine and aryl bromide, for solid-phase diversification via N-capping and Pd-mediated cross coupling. A sparse matrix design strategy that achieves the dual objective of controlling physicochemical properties and selecting diverse library members was implemented. The production of two 8000-membered libraries is discussed including a full analysis of library purity and property distribution. Library diversity was evaluated in comparison to the Molecular Library Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) through the use of a multi-fusion similarity (MFS) map and principal component analysis (PCA).

Introduction

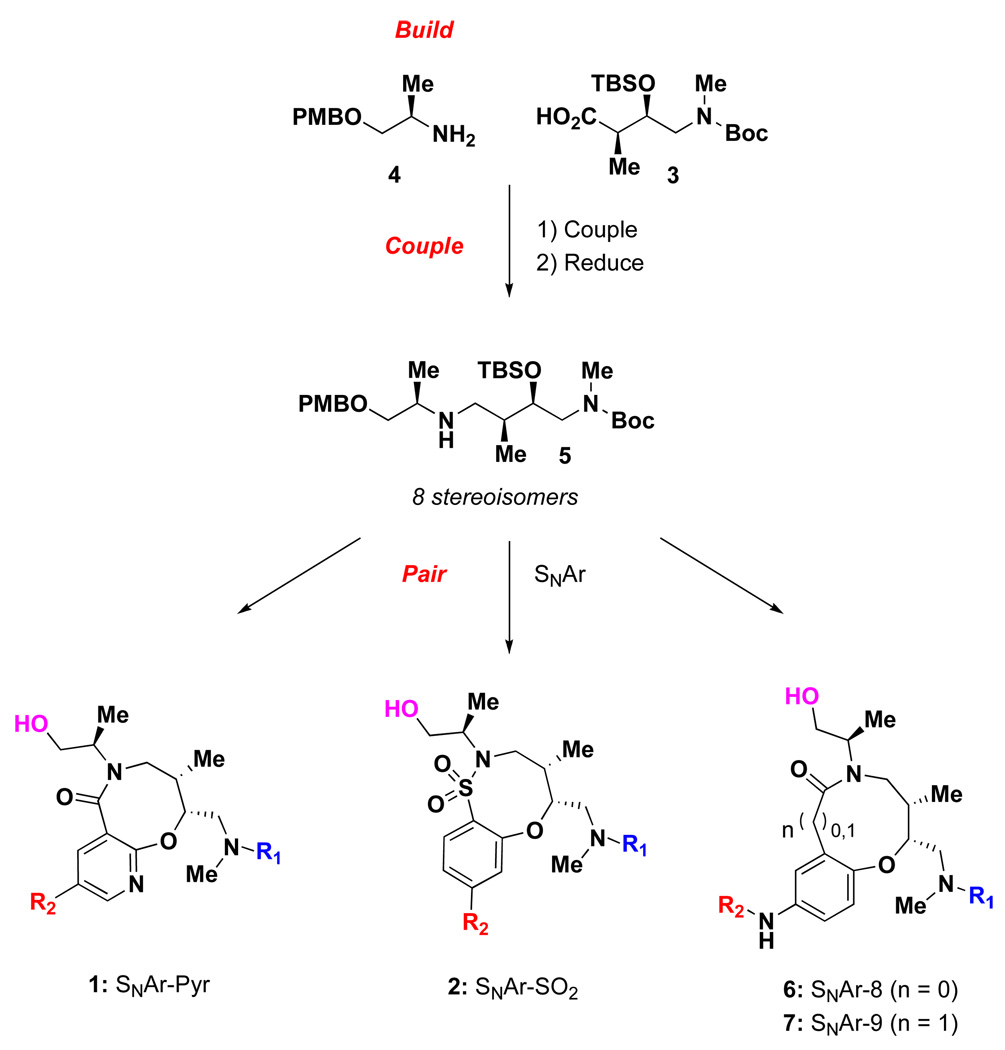

Diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) is a commonly employed strategy for the facile assembly of structurally diverse molecules rivaling the complexity of natural products.1 A primary goal of DOS is the generation of compounds with both skeletal and stereochemical diversity. Recently we described an aldol-based ‘build/couple/pair’ (B/C/P) strategy for the generation of a stereochemically diverse set of medium- and large-sized rings via a common linear template.2 Here, we take advantage of this aldol-based strategy for the synthesis of fused pyridines (1) and fused sultams (2) (Figure 1). In the build phase, a series of asymmetric syn- and anti-aldol reactions were applied to produce four stereoisomers of a Boc protected β-hydroxy-γ-amino acid (3). Both stereoisomers of PMB-protected alaninol (4) were also obtained to complement the aldol-derived acids. In the couple step, all 8 stereoisomeric amides were synthesized from both the chiral acid and amine building blocks. The amide was subsequently reduced to generate a secondary amine (5). Finally, in the pair phase, we utilized an intramolecular SNAr3 as the key cyclization step to access either the SNAr-Pyr lactam (1)4 or the SNAr-SO2 sultam (2).5 This work is built off of our previous success with the SNAr reaction for the synthesis of 8- and 9-membered lactams (6 and 7).2 Two 8000-membered libraries were produced using solid-phase synthesis techniques. All 8 stereoisomers were prepared for each scaffold, providing not only structure-activity relationships (SAR) in primary screens, but also stereo/structure-activity relationships (SSAR). A sparse matrix library design strategy6,7 was utilized to aid in the selection of diverse library members with built-in structural analogs and physicochemical properties suitable for high-throughput screening and downstream discovery.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of medium-sized ring scaffolds from a common linear intermediate.

Solution-phase synthesis of library scaffolds

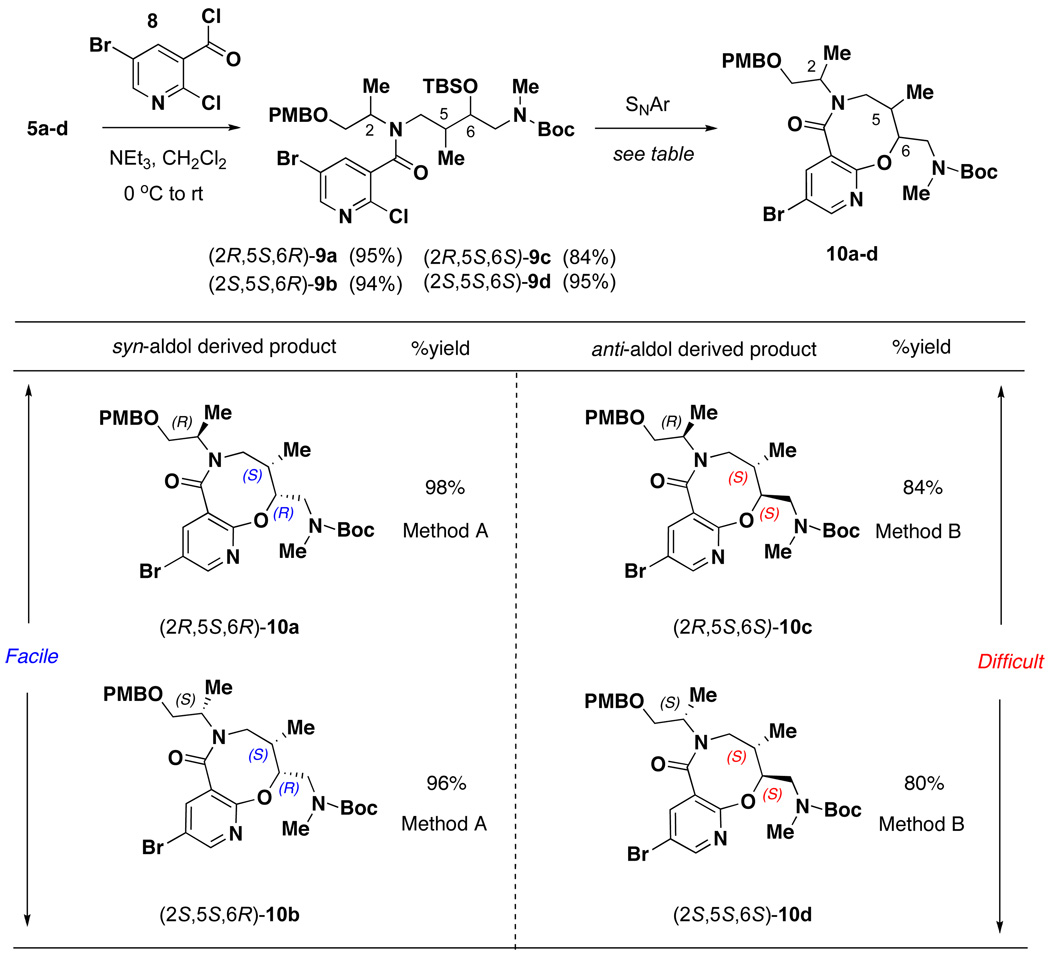

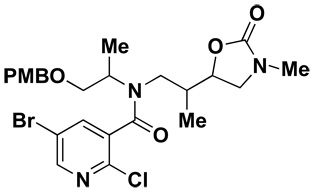

The synthesis of SNAr-Pyr scaffold 1 began with acylation of linear amine 5 using 5-bromo-2-chloronicotinoyl chloride 8, which afforded amide 9a–d in good yields (Table 1). The subsequent intramolecular SNAr reaction showed strong stereochemical dependence. Amide 9a was converted directly to 10a in excellent yield (94%) upon treatment with TBAF in THF at 65 °C. However, application of these conditions to 9b provided lactam 10b in modest yield (71%). Fortunately, a two step protocol involving cyclization using NaH in THF once the TBS group had been deprotected with CsF proved effective. The syn-aldol derived substrates 9a and 9b were converted to 10a and 10b respectively in high yields (96–98%) without a need for chromatographic purification using this two step protocol. Meanwhile, SNAr reaction of anti aldol-derived substrates 9c and 9d proved challenging, as the two step protocol led to formation of significant amount of oxazolidinone side-product (40–50%).8 Use of the one step deprotection/cyclization using TBAF in THF led to incomplete reaction even after 5 days and repeated addition of TBAF. Finally, choice of the solvent proved critical and use of TBAF in DMF led to complete conversion of the SNAr reaction with minimal oxazolidinone formation (10–15%). Under these conditions, the anti-aldol derived substrates 9c and 9d gave 84% and 80% of 10c and 10d, respectively. As our plan called for loading onto solid support (SynPhase™Lanterns)9 using an acid-labile silicon linker, the Boc protecting group was exchanged for Fmoc, and subsequent DDQ mediated PMB removal led to the isolation of primary alcohol 1 (Scheme 1). SNAr-pyr scaffolds 1a–d (and the corresponding enantiomers ent-1a–d) were prepared in 15–20 g quantities using this 5-step sequence starting from linear amine 5.

Table 1.

SNAr cyclization to form lactams 10a–d

|

SNAr reaction conditions: Method A a) CsF (5 equiv), DMF, 85 °C; (b) NaH (5 equiv), THF, 0 °C to rt; Method B TBAF (5 equiv), DMF, 65 °C.

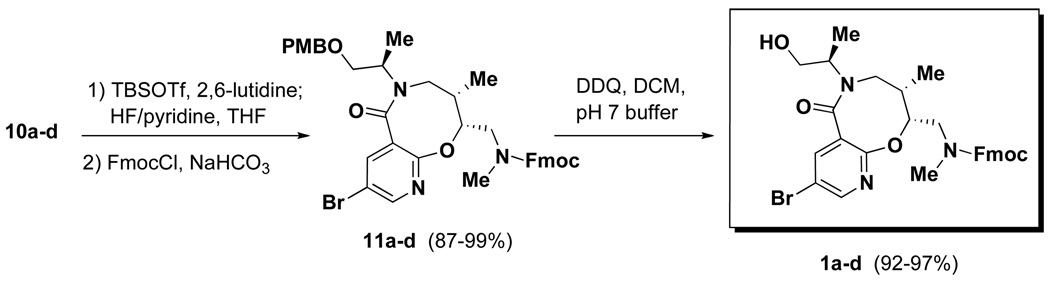

Scheme 1.

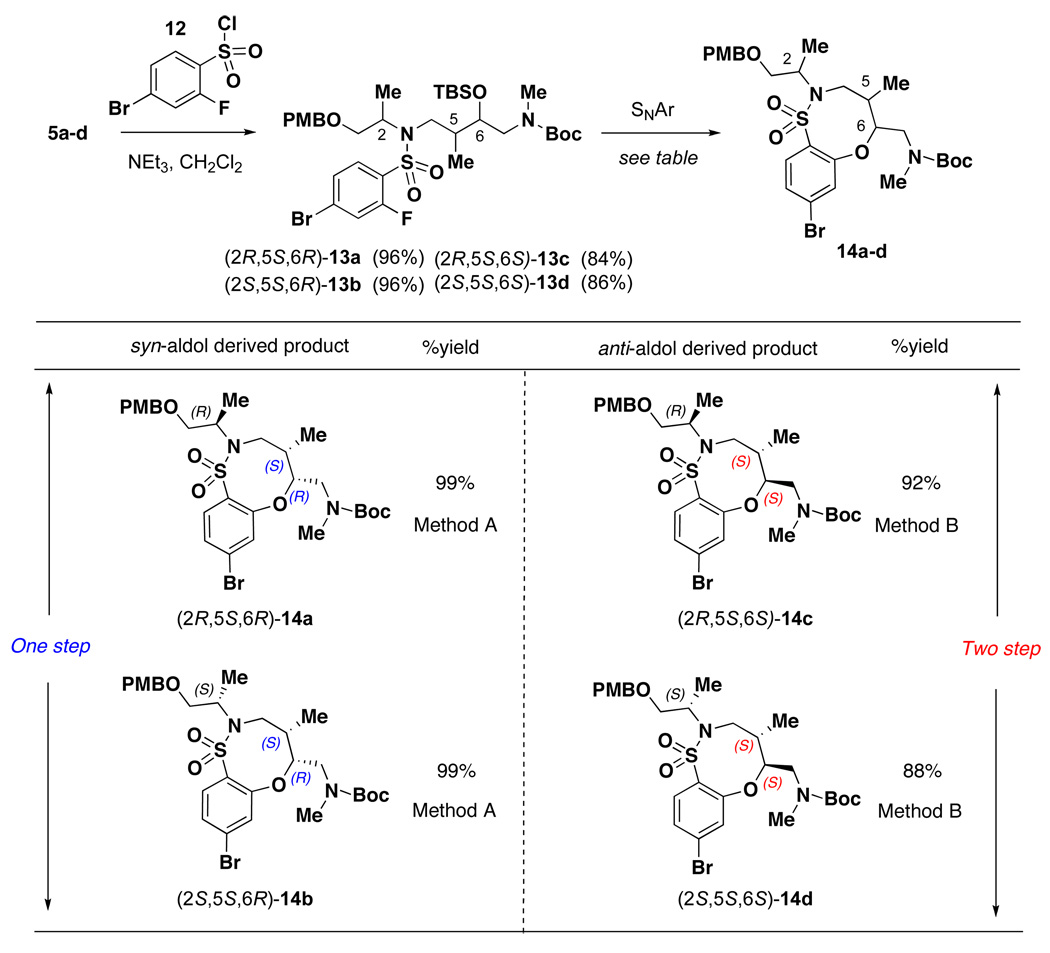

Preparation of final SNAr-Pyr scaffold 1

A similar approach as described above was utilized in the synthesis of fused bicyclic sultams.5 All stereoisomers of the common linear intermediate 5 were coupled with 4-bromo-2-fluorobenzene sulfonyl chloride 12 in good yield to give the SNAr precursor 13 (Table 2). Similar to the pyridine fused systems, the SNAr reaction involving sulfonamides 13 proceeded differently depending on the relative stereochemistry of the adjacent stereocenters. Sulfonamides 13a and 13b, both derived from the syn-aldol reaction, were easily converted in excellent yield to sultams 14a and 14b, respectively, by treatment with CsF in DMF at 85 °C. Sulfonamides 13c and 13d, both derived from the anti-aldol, were converted to sultams 14c and 14d utilizing the two-step approach that was employed for substrates 9a and 9b. First, treatment with CsF gave a mixture of uncyclized TBS deprotected material along with desired 14. Treatment of the mixture with NaH gave complete conversion to 14c and 14d, respectively, in good yield over the two steps. It is important to note, no matter the protocol used, the product could be isolated in sufficient purity without silica gel purification. This is in contrast to the SNAr-Pyr substrates, where the use of TBAF required silica gel purification. Completing the synthetic sequence required the exchange of the Boc group for Fmoc followed by DDQ-mediated PMB removal to afford the desired SNAr-SO2 scaffolds 2a–d (and the corresponding enantiomers ent-2a–d) in good yield in 15–20 g quantities (Scheme 2).

Table 2.

SNAr cyclization to form sultams 14a–d

|

SNAr reaction conditions: Method A CsF (5 equiv), DMF, 85 °C; Method B a) CsF (5 equiv), DMF, 85 °C; (b) NaH (1 equiv), THF, 0 °C to rt.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of final SNAr-SO2 scaffold 2

Library Design

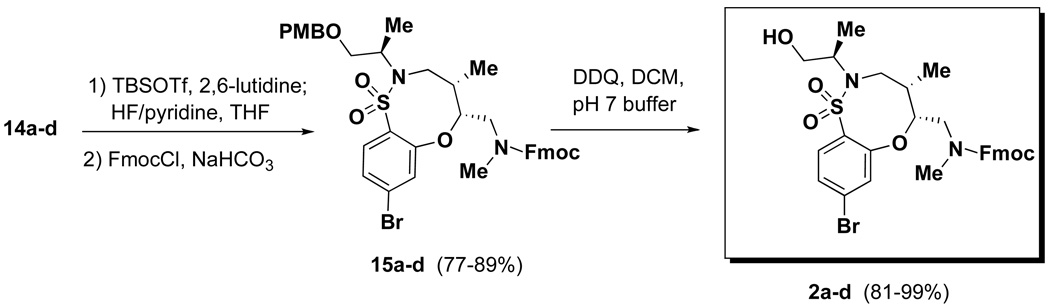

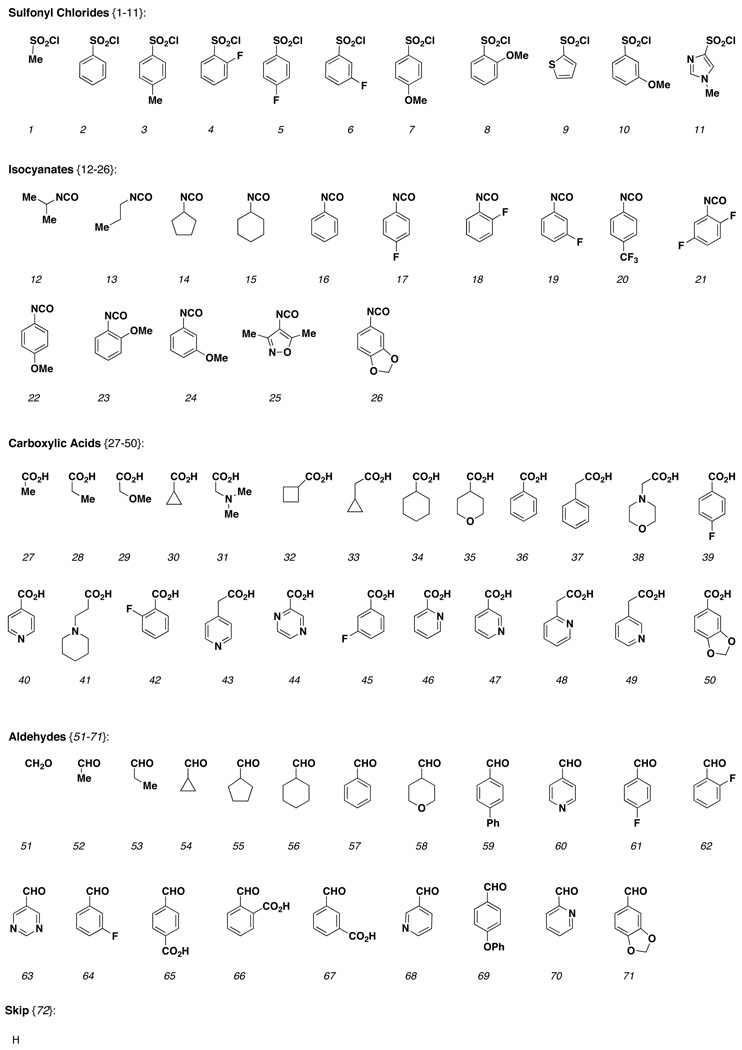

With the SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 scaffolds in hand, a sparse matrix design strategy was implemented to select library members to be synthesized.6 A virtual library was constructed for each scaffold incorporating all possible building block combinations at R1 (amine) and R2 (aryl bromide) using a master list of reagents (R1 = sulfonyl chlorides, isocyanates, acids and aldehydes; R2 = boronic acids and alkynes). Physicochemical property filters were then applied to eliminate building block combinations that led to products with undesirable physicochemical properties. Property filters included the following: MW ≤625, ALogP -1 to 5, H-bond acceptors and donors ≤10, rotatable bonds ≤10 and TPSA ≤140. In order to increase the percentage of ‘Lipinski compliant’ products, a ‘75/25’ rule was also implemented where 75% of all library members had MW <500. A total of 1000 compounds per scaffold were selected from the remaining set using chemical similarity principles, maximizing diversity but retaining near neighbors for built-in SAR. The reagents selected for library production are shown below (Chart 1 and Chart 2). The same set of reagents was used for each stereoisomer thereby maintaining the ability to generate SSAR for each building block combination.

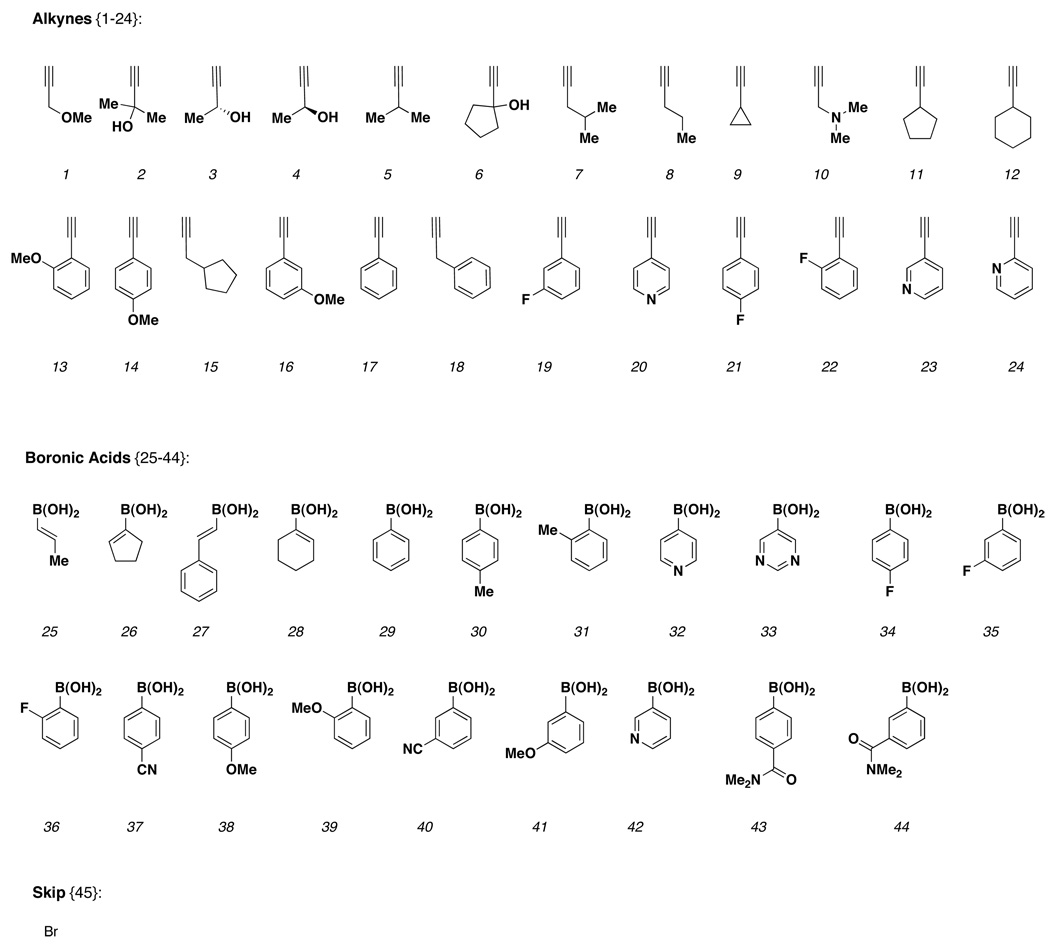

Chart 1.

Building blocks {1–72} used for amine capping at R1.

Chart 2.

Building blocks {1–45} used for cross-coupling reactions at R2.

Solid-phase Library Production

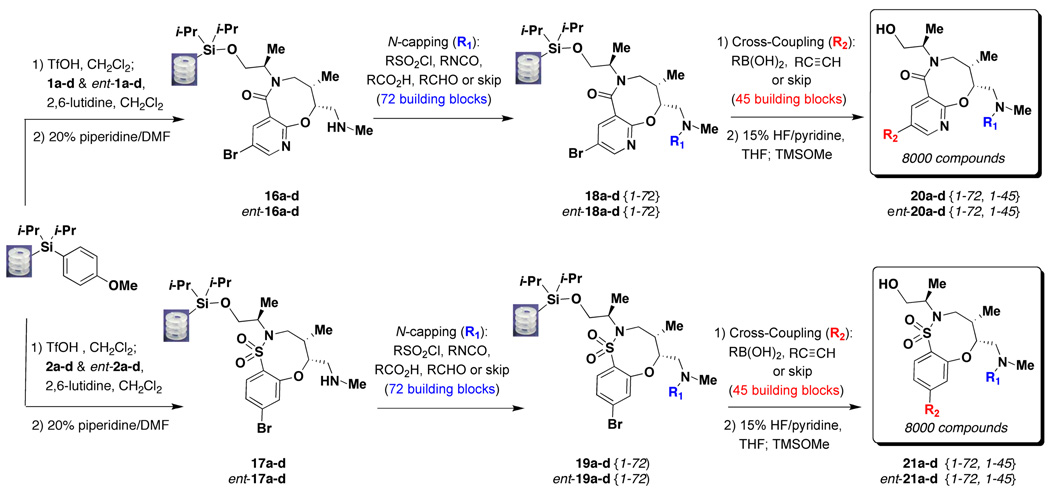

The construction of the SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries is outlined in Scheme 3. Scaffolds 1a–d and 2a–d (and the corresponding enantiomers) were loaded onto silicon-functionalized PS-SynPhase™ Lanterns (L-series) activated with TfOH in the presence of 2,6-lutidine (average loading level = 18 umol/Lantern).9,10 The first diversity site, a secondary amine, was then revealed under standard conditions required for Fmoc removal (20% piperidine in DMF), and amines 16a–d and 17a–d were capped with the selected electrophiles (sulfonyl chlorides 1–11, isocyanates 12–26, carboxylic acids 27–50 and aldehydes 51–71) or skipped (72) to yield compounds 18a–d{1–72} and 19a–d{1–72}. Next, Sonogashira and Suzuki cross-coupling reactions were carried out to introduce appendage diversity at R2. For the Sonogashira reaction, the Lantern-bound aryl bromides were heated at 60 °C in DMF overnight in the presence of DIEA, CuI, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, and the selected alkynes {1–24}. Meanwhile, for the Suzuki reaction, the Lanterns were heated at 60 °C in EtOH for 5 days in the presence of Et3N, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 and boronic acids {25–44}. Removal of residual Pd and Cu was achieved by washing the Lanterns with 0.1 M NaCN. Finally, cleavage with HF-pyridine in THF afforded library members 20a–d{1–72,1–45} and 21a–d{1–72,1–45} with an average yield of 90 and 91% respectively.11

Scheme 3.

Solid-phase synthesis of SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries on SynPhase™ Lanterns

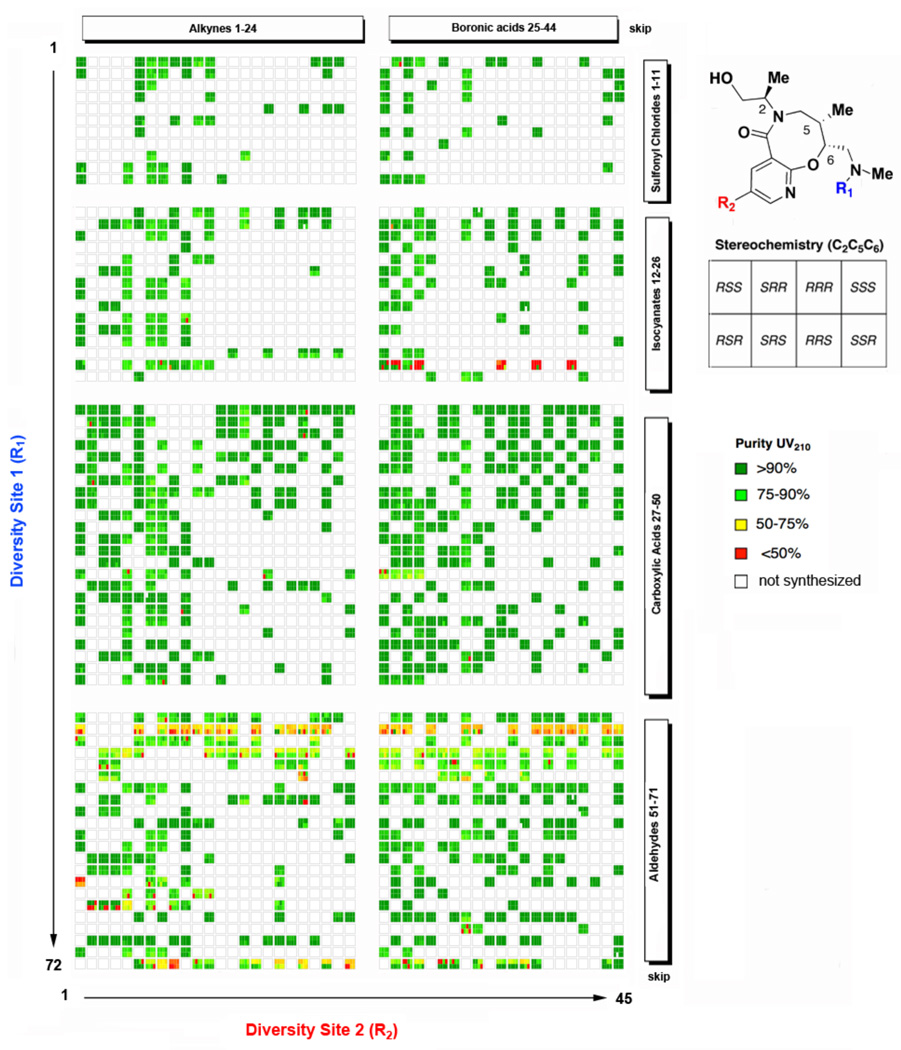

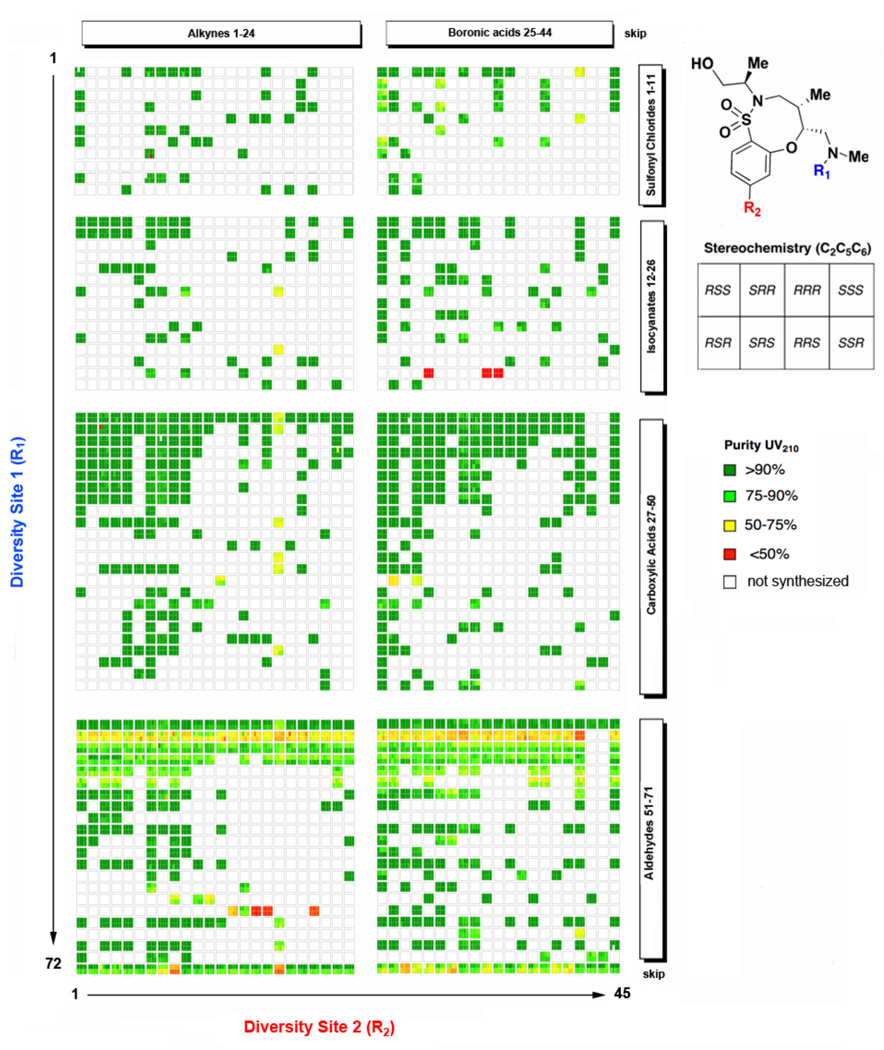

All library products were analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography, and compound purity was assessed by UV detection at 210 nm. An overview of compound purity for the SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries with respect to building blocks and stereochemistry is provided in Figures 2 and 3. The average purity of the SNAr-Pyr library was 85%, with 89% of the library being >75% pure, while the average purity of the SNAr-SO2 library was 85%, with 91% of the library being >75% pure. (See Figures S5 and S6). In general, all building blocks performed well during the library production with the exception of certain reagent combinations. For example, compounds containing the dimethylisoxazole urea (18a–d{25} and 19a–d{25}) performed poorly in the subsequent Suzuki reaction, presumably due to reduction of the N-O bond, as an M+2 impurity was observed by LCMS for this reagent combination. Meanwhile products of reductive alkylation with 3-pyridyl benzaldehyde 18a–d{68} and 19a–d{68} performed poorly in the subsequent Sonogashira reaction. The success of the cross-coupling reaction in the presence of a free amine at R1 to produce library members 20a–d{72,1–44} and 21a–d{72,1–44} was highly variable depending on the nature of the boronic acid and alkyne but in general was problematic. Surprisingly, the use of acetaldehyde for reductive alkylation at R1 resulted in compounds (20a–d{2,1–72} and 21a–d{2,1–72}) of low purity for both libraries.

Figure 2.

Purity analysis (UV 210 nm) for SNAr-Pyr Library. Library members are displayed as blocks of 8 stereoisomers (see legend) and reagents used for solid-phase diversification are shown on the x- and y-axes. (See Charts 1 and 2 for detailed list of reagents).12

Figure 3.

Purity analysis (UV 210 nm) for SNAr-SO2 Library. Library members are displayed as blocks of 8 stereoisomers (see legend) and reagents used for solid-phase diversification are shown on the x- and y-axes. (See Charts 1 and 2 for detailed list of reagents).12

Library Analysis

The SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries originate from the same linear intermediate (5, Figure 1) and vary in the pairing stage giving rise to different molecular architectures. The SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 scaffolds have differences in their physicochemical properties such as molecular weight (372/407), ALogP (1.2/1.5) and TPSA, (75/87) that ultimately influence product selection (Table 3). As evident in Figures 2 and 3 the selected building block combinations vary significantly for these two scaffolds. For example, products are spread evenly in the SNAr-Pyr library (Figure 2), as compared to the SNAr-SO2 library (Figure 3) for which small aliphatic building block combinations are favored (e.g., acids 27–34 and aldehydes 51–54). Analysis of the SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries reveals that the property profile for each library was within the intended range for the library design (MW ≤625, ALogP -1 to 5, H-bond acceptors and donors ≤10, rotatable bonds ≤10 and TPSA ≤140). Not surprisingly, SNAr-SO2 library members have higher mean values for MW and TPSA due to inherent differences between the initial scaffolds.

Table 3.

Property analysis for SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries

| Property | SNAr-Pyr Scaffolda (n = 1) |

SNAr-SO2 Scaffolda (n = 1) |

SNAr-Pyr Libraryb (n = 7045) |

SNAr-SO2 Libraryb (n = 6690) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 372 | 407 | 484 | 504 |

| ALogP | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.9 |

| TPSA | 75 | 87 | 95 | 105 |

| Rotatable Bonds | 4 | 4 | 7.3 | 7.2 |

| HBA | 5 | 5 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| HBD | 2 | 2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

Property analysis of bare scaffolds, where R1 and R2 = H.

Property analysis (mean value) of all registered library samples passing QC requirements (purity >75%).

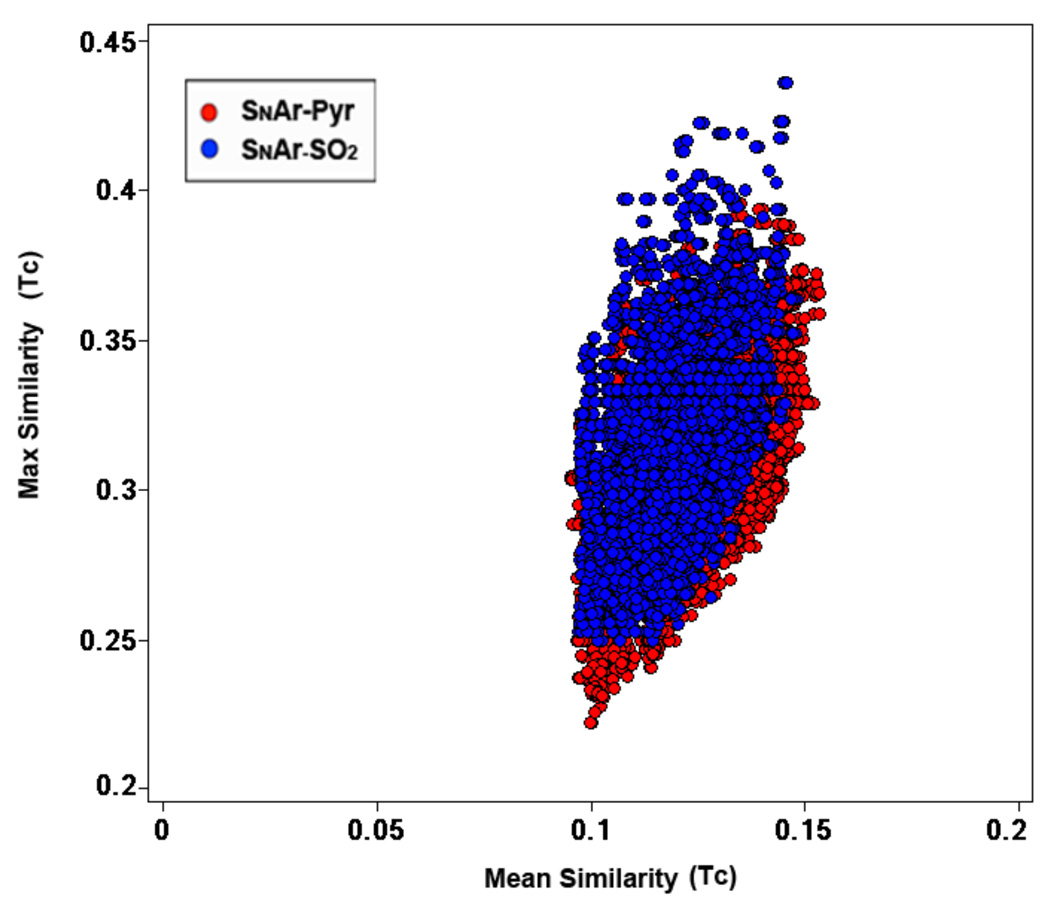

The structural diversity of library members resulting from SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 pathways was analyzed in comparison to the NIH Molecular Library Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) as we intended to submit a subset of these compounds to the collection at the time of the analysis. We employed multi-fusion similarity (MFS) maps for the comparison of each collection using extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFP_4) for molecular representation and Tanimoto coefficient as the similarity measure.13 In this method, each molecule in the test set (SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 library members) is compared to every molecule in the reference set (MLSMR) and the largest similarity score and the mean similarity score to the reference set is obtained. The resulting mean similarity (X-axis) and maximum similarity (Y-axis) values are plotted in two dimensions as a scatter plot facilitating the visual characterization and comparison. Figure 4 shows the MFS map comparing SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries to the MLSMR. Each data point in the map depicts a compound from the test set and its location was influenced by the reference set. (The reference compounds themselves do not appear in the plot.) The maximum mean similarity of each library is 0.15 indicative of their overall structural diversity with respect to the MLSMR reference set. There are no compounds with maximum similarity equal to or greater than 0.45 in the MLSMR, which clearly illustrates the regions of chemical space unexplored by the MLSMR.

Figure 4.

Multi-fusion similarity map comparing the SNAr-Pyr (red) and SNAr-SO2 (blue) libraries to the MLSMR. The reference set (MLSMR) is not shown on the map (see text for details).

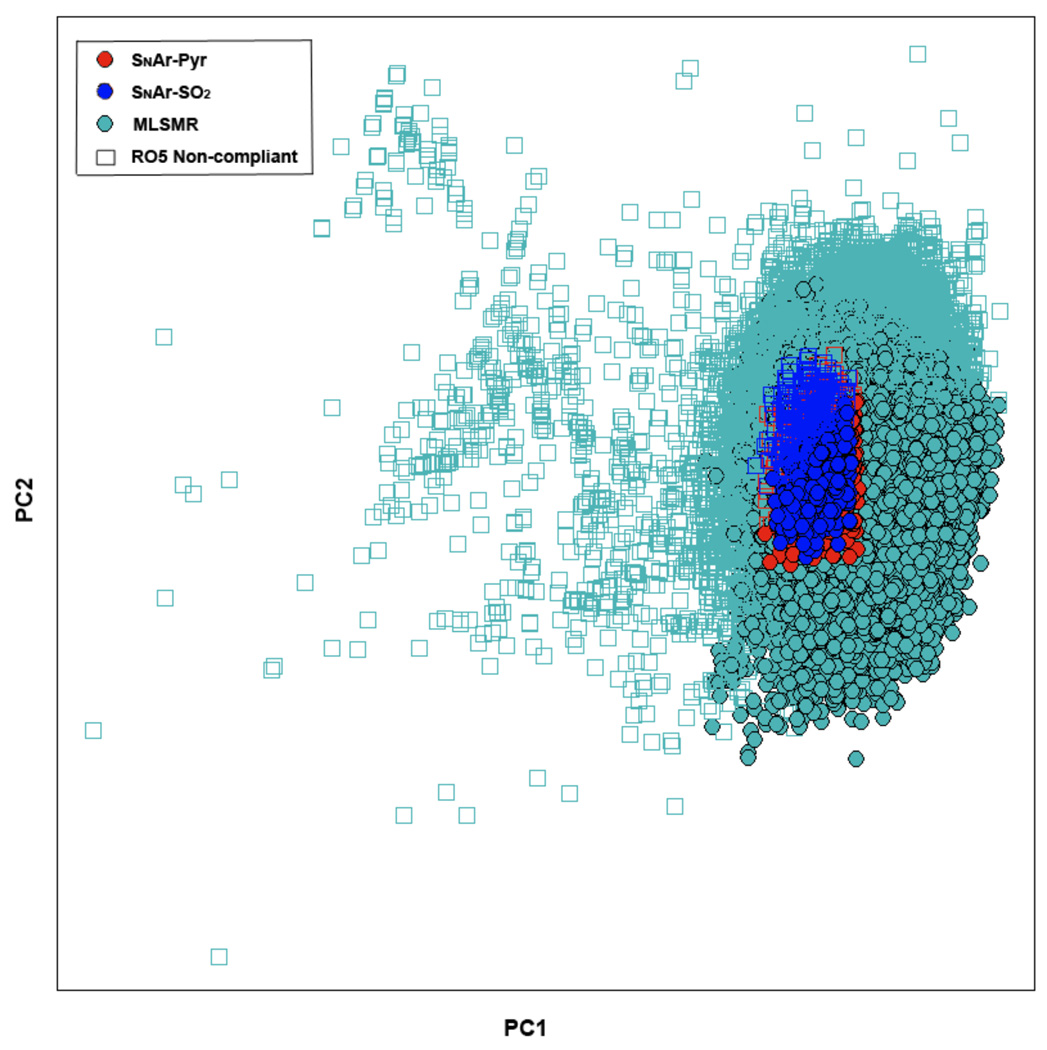

We also carried out a principal components analysis (PCA)14 using 16 structural and physicochemical descriptors (including MW, ALogP, rotatable bonds and TPSA) for the MLSMR and SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries. The PCA plot is shown in Figure 5. The DOS libraries property space is embedded in the MLSMR property space with ~75% of compounds being Lipinski compliant. This observation is particularly important because it dispels the common notion that DOS may not render compounds with good properties.15 While occupying the desirable property space we have covered new chemical space of structural diversity.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis of SNAr-Pyr and SNAr-SO2 libraries compared to MLSMR. The 16 molecular descriptors used for PCA included molecular weight, ALogP, LogD, number of rotatable bonds, TPSA, number of nitrogen, oxygen, halogen, and sulfur atoms, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, aromatic rings, ring fusion degree, normalized number of ring systems, chiral centers, and fraction of sp3.

Conclusion

In summary we have implemented an aldol-based ‘build/couple/pair’ (B/C/P) strategy for synthesis of stereochemically diverse 8-membered lactam and sultam scaffolds via SNAr cycloetherification. A sparse matrix design strategy was implemented to select library members for synthesis to achieve a balance between diversity and built-in structural analogs. Analysis of final library members illustrates that the sparse matrix design achieved the intended outcome of structural diversity and favorable physicochemical properties. Screening of these compounds is currently underway in multiple biochemical and cell-based assays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by the NIGMS-sponsored Center of Excellence in Chemical Methodology and Library Development (Broad Institute CMLD; P50 GM069721), as well as the NIH Genomics Based Drug Discovery U54 grants Discovery Pipeline RL1CA133834 (administratively linked to NIH grants RL1HG004671, RL1GM084437, and UL1RR024924). We would like to thank Dr. Stephen Johnston for analytical support and Anita Vrcic for sorting, cleavage and formatting of library members.

References

- 1.(a) Schreiber SL. Target-Oriented and Diversity-Oriented Organic Synthesis in Drug Discovery. Science. 2000;287(5460):1964–1969. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Burke MD, Schreiber SL. A Planning Strategy for Diversity-Oriented Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:46–58. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Neilsen TE, Schreiber SL. Towards the Optimal Screening Collection: A Synthesis Strategy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;74:48–56. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcaurelle LA, Comer E, Dandapani S, Duvall JR, Gerard B, Kesavan S, Lee MD, IV, Liu H, Lowe JT, Marie J-C, Mulrooney CA, Pandya BA, Rowley A, Ryba TD, Suh B-C, Wei J, Young DW, Akella LB, Ross NT, Zhang Y-L, Fass DM, Reis SA, Zhao W-Z, Haggarty SJ, Palmer M, Foley MA. An Aldol-Based Build/Couple/Pair Strategy for the Synthesis of Medium- and Large-Sized Rings: Discovery of Macrocyclic Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16962–16976. doi: 10.1021/ja105119r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For the synthesis of aryl-alkyl ethers via intramolecular SNAr, see: Goldberg M, Smith L, II, Tamayo N, Kiselyov AS. Solid Support Synthesis of 14-Membered Macrocycles Containing 4-Hydroxyproline Structural Unit via SNAr Methodology. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:13887–13898. Jefferson EA, Swayze EE. β-Amino Acid Facilitates Macrocyclic Ring Closure in a Combinatorial Library. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:7757–7760. Temal-Laib T, Chastanet J, Zhu J. A Convergent Approach to Cyclopeptide Alkaloids: Total Synthesis of Sanjoinine G1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:583–590. doi: 10.1021/ja0170807. Abrous L, Jokiel PA, Friedrich SR, Hynes J, Jr, Smith AB, III, Hirschmann R. Novel chimeric scaffolds to extend the exploration of receptor space: Hybrid beta-D-glucose-benzoheterodiazepine structures for broad screening. Effect of amide alkylation on the course of cyclization reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:280–302. doi: 10.1021/jo0352068. Tempest P, Ma V, Kelly MG, Jones W, Hulme C. MCC/SnAr methodology. Part 1: Novel access toa range of heterocyclic cores. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:4963–4968.

- 4.For the synthesis of a related pyridoxazocinone scaffold, see: Seto S, Tanioka A, Ikeda M, Izawa S. Design and synthesis of novel 9-substituted-7-aryl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2H-pyrido[4,3-b]- and [2,3-b]-1,5-oxazocin-6-ones as NK1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:1479–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.091.

- 5.For previous work on the synthesis of sultams, see: Rolfe A, Lushington GH, Hanson PR. Reagent Based DOS: A Click, Click, Cyclize Strategy to Probe Chemical Space. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:2198–2203. doi: 10.1039/b927161a. Samarakoon TB, Hur MY, Kurtz RD, Hanson PR. A Formal [4+4] Complementary Ambiphile Pairing (CAP) Reaction: A New Cyclization Pathway for ortho-Quinone Methides. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2182–2185. doi: 10.1021/ol100495w. Rolfe A, Samarakoon TB, Hanson PR. Formal [4+3] Epoxide Cascade Reaction via a Complementary Ambiphilic Pairing. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1216–1219. doi: 10.1021/ol100035e. Jeon KO, Rayabarapu D, Rolfe A, Volp K, Omar I, Hanson PR. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:4992–5000. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.03.080. Rayabarapu DK, Zhou A, Jeon KO, Samarakoon T, Rolfe A, Siddiqui H, Hanson PR. α-Haloarylsulfonamides: Multiple Cyclization Pathways to Skeletally Diverse Benzofused Sultams. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3180–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.11.053. Zhou A, Rayabarapu D, Hanson PR. "Click, Click, Cyclize”: A DOS Approach to Sultams Utilizing Vinyl Sulfonamide Linchpins. Org. Lett. 2009;11:531–534. doi: 10.1021/ol802467f. Jimenez-Hopkins M, Hanson PR. An RCM Strategy to Stereodiverse δ-Sultam Scaffolds. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2223–2226. doi: 10.1021/ol800649n.

- 6.For details concerning the application of a sparse matrix design strategy for diversity-oriented synthesis, see: Akella LB, Marcaurelle LA. Application of a Sparse Matrix Design Strategy to the Synthesis of DOS Libraries. ACS Comb. Sci. doi: 10.1021/co200020j. Accepted.

- 7.(a) Weber L. Current Status of Virtual Combinatorial Library Design. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2005;24:809–823. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clark RD, Kar J, Akella L, Soltanshahi F. OptDesign: Extending Optimizable k-Dissimilarity Selection to Combinatorial Library Design. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003;43:829–836. doi: 10.1021/ci025662h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

8.Structure of oxazolidinone byproduct formed in the presence of NaH:

- 9.(a) Ryba TD, Depew KM, Marcaurelle LA. Large-scale preparation of silicon- functionalized SynPhase Lanterns for solid-phase synthesis. J. Comb. Chem. 2009;11:110–116. doi: 10.1021/cc8000986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Duvall JR, Vrcic A, Marcaurelle LA. Small-molecule library synthesis on silicon-functionalized SynPhase Lanterns. Curr. Protoc. Chem. Bio. 2010;2:135–151. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch100038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanterns were equipped with radio frequency transponders to enable tracking and sorting of library members.

- 11.Average yield adjusted for purity. See Supporting Information (Figures S1–S4) for yield analysis.

- 12.A detailed account of purity and yield for each library compound is provided as Supporting Information.

- 13.(a) Medina-Franco JL, Maggiora GM, Giulianotti MA, Pinilla C, Houghten RA. A similarity-based data-fusion approach to the visual characterization and comparison of compound databases. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2007;70:393–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Medina-Franco JL, Martínez-Mayorga K, Giulianotti MA, Houghten RA, Pinilla C. Visualization of the Chemical Space in Drug Discovery. Curr. Comp. Aided Drug Des. 2008;4:322–333. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolliffe IT. Principal Component Analysis, Second Ed. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Shelat AA, Guy K. The Interdependence between Screening Methods and Screening Libraries. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cooper TWJ, Campbell IB, Macdonald SJF. Factors Determining the Selection of Organic Reactions by Medicinal Chemists and the Use of These Reactions in Arrays (Small Focused Libraries) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:8082–8091. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Singh N, Guha R, Giulianotti MA, Pinilla C, Houghten RA, Medina-Franco JL. Chemoinformatic Analysis of Combinatorial Libraries, Drugs, Natural Products, and Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository. J. Chem. Info. Model. 2009;49:1010–1024. doi: 10.1021/ci800426u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.