Abstract

The Ministry of Health in Iraq is undertaking a systematic programme to integrate mental health into primary care in order to increase population access to mental health care. This paper reports the evaluation of the delivery of a ten day interactive training programme to 20% of primary care centres across Iraq. The multistage evaluation included a pre- and post-test questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitudes and practice in health workers drawn from 143 health centres, a course evaluation questionnaire and, in a random sample of 41 clinics, direct observation of health workers skills and exit interviews of patients, comparing health workers who had received the training programme with those from the same clinics who had not received the training. Three hundred andseventeen health workersparticipated in the training, which achieved an improvement in test scores from 42.3% to 59%. Trained health workers were observed by research psychiatrists to have a higher level of excellent skills than the untrained health workers, and patient exit interviews also reported better skills in the trained rather than untrained health workers. The two week course has thus been able to achieve significant change, not only in knowledge, but also in subsequent demonstration of trained practitioners practical skills in the workplace. Furthermore, it has been possible to implement the course and the evaluation despite a complex conflict situation.

Keywords: evaluation, mental health, primary care, training

Introduction

Iraq has a population of 30 million, with a life expectancy of 69 years and literacy of 76%. Mortality in under-fives is 69 per 1000 and maternal mortality is 400 per 100 000. The rate if HIV infection is 0.8%.1 Until the 1980s Iraq prided itself on its progressive and responsive healthcare system and was known as the jewel in the crown of the Middle East. However, during the 1990s the regime of Saddam Hussein cut public health funding by 90%, leading to an increase in maternal mortality, infant mortality, malnutrition and infectious diseases. The conflict of 2003 destroyed an estimated 12% of hospitals and primary care centres.2 Since that time, substantial international funds have enabled the operation of 240 hospitals and 1200 primary health centres, and the training of staff, although continuing conflict has hampered health provision, especially in areas of violent insurgency.3

Before 2003, mental health services were served by about 100 psychiatrists running public outpatient services in a few universities, a single large psychiatric hospital in Baghdad (1300 beds) and extensive private clinics in the main cities. Since 2003 consecutive administrations have tried to rebuild the system, and have taken the opportunity to decentralise and increase population access to mental health care. Thus since 2003, small mental health units within general hospitals have been established in all governorates while private sector clinics continue to provide a sizeable service.4 Non-governmental organisations provide logistic support and training for staff, as well as providing community based support.5

However, the prevalence of mental disorders is so high in all countries, including Iraq,6,7 that specialist care can only ever meet a small proportion of population needs, and there is international consensus that the role of primary care in the delivery of mental health care is a cornerstone for comprehensive services.8–10 It eases access and overcomes the stigma of attending psychiatric hospitals and clinics. Furthermore, early diagnosis and treatment, a friendly environment, better collaboration with specialised services, and effective supervision and follow-up of chronic patients are other advantages of integrating mental health into primary care.11

An earlier baseline survey of public perceptions of mental disorder indicated that the Iraqi public would welcome the development of mental health services in primary care and indicated their preference for a locally responsive service.12

Primary healthcare centres were first established in Iraq in the 1950s and were expanded during the post-2003 reconstruction phase to number 1136 in 2007,each serving a population of 35000, with 1480 728 consultations annually;5 in 2008 the Ministry of Health began a systematic programme to integrate mental health provision into primary care.

Methods

Governance of the programme

The Iraq Ministry of Health appointed a lead in primary care and another in specialised services for each governorate. They were tasked with training healthcare staff, improving population access to care, updating medical records and enhancing collaboration between primary care and specialised care. A memorandum of understanding was signed between the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the International Medical Corps (IMC), to provide training on mental health for primary care across the country. IMC appointed a mental health advisor to the MoH who led the programme to integrate mental health into primary care, in dialogue with the mental health and primary care directorates in the MoH. The IMC mental health advisor worked closely with the MoH, the National Council for Mental Health and the Ministry of Health in Kurdistan.

Content of the training programme

The training programme for primary care is a ten-day course, and consists of five modules, the first covering core concepts (mental health, mental disorders and common neurological disorders and their contribution to physical health, economic and social outcomes, and understanding linkages between mental health and the Millennium Development Goals); the second, core skills (communication skills, assessment, mental state examination, diagnosis, management, managing difficult cases, management of violence and breaking bad news); the third, common neurological disorders (epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, headache, dementia, toxic confusional states), the fourth, psychiatric disorders (content based on the World Health Organization primary care guidelines, adapted for Iraq) and the fifth, health (and other sector) system issues of policy; legislation; links between mental health and child health, reproductive health, HIV and malaria; roles and responsibilities; health management information systems; working with community health workers and with traditional healers; and integration of mental health into annual operational plans.

Delivery of the training programme

The primary care training programme started in February 2009 and ended in November 2009, and comprised eight courses covering 20% of primary healthcare centres (PHCs) across Iraq. The training toolkit was adapted for Iraq from a toolkit developed for Kenya and used in a number of countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia;13,14 it was translated into Arabic. Each training course lasted two weeks and covered all aspects of mental health. They were delivered in the form of data presentations (with Arabic and English simultaneously on the slides), role plays, small and large discussion groups, videos and visits to mental health units. Trainees received CDs of the course materials, checklists, booklets and educational pamphlets for patients. Two workshops were held for mental health leads to review the programme and to discuss outcome results. All agreed to persevere with all efforts to consolidate the program and provide support to cover all PHCs.

Evaluation of the training programme

The impact of the training programme was assessed in two stages. In the first stage, all participants were assessed before and after the training programme with a pre- and post-test questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitudes and practice (devised as part of the teaching toolkit).14 In the second stage, a random sample of 41 clinics was drawn from the six governorates of Baghdad al Rusafa, Basra, Najaf, Kerbela, Babel, Dewaniya, and trained and untrained staff from the same clinics were then evaluated with a course evaluation questionnaire and a job skills assessment adapted by the IMC from the manuals of the Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore.

The job skills assessment included observation of a physician's skills during his daily work and exit interviews of five randomly selected patients from his clinic. The job skills assessment procedure was conducted by seven psychiatrists from different hospitals in several governorates, who had been selected by IMC in collaboration with the national mental health adviser to the MoH. Thepsychiatrists received a brief training in the evaluation procedure from the IMC, and were then distributed to assess the 41 health centres and conduct patient exit interviews. The psychiatrists were initially blind to the training status of the physicians, although during the course of the assessment this may have become apparent to the assessor.

Results

Table 1 gives the distribution of PHC clinics assessed in each governorate. A total of 317 healthcare workers drawn from 143 health centres participated in the overall training programme. Of these, 117 (37%) were general practitioners, 83 (26%) healthcare workers, 42 (13%) nurses, 33 (10%) social workers and 13% others. Of the total, 109 (34%) were women.

Table 1.

Number of PHC clinics observed in each governorate

| Governorate | Number of PHC clinic observed |

|---|---|

| Baghdad | 9 |

| Babil | 5 |

| Basrah | 13 |

| Dewaniyah | 2 |

| Karbala | 6 |

| Najaf | 6 |

| Total | 41 |

Table 2 gives the distribution of patient exit interviews. Trained and non-trained staff in 41 clinics were observed and 820 patient exit interviews were conducted.

Table 2.

Distribution of patient exit interviews performed in each governorate

| Governorate | Number of interviews performed (non-trained) | Number of interviews performed (trained) |

|---|---|---|

| Babil | 50 | 50 |

| Baghdad | 91 | 91 |

| Basrah | 130 | 130 |

| Dewaniyah | 18 | 20 |

| Karbala | 60 | 60 |

| Najaf | 60 | 60 |

| Total | 409 | 411 |

The training achieved an improvement in test scores from a pre-training average score of 42.3% to a post-training score of 59% (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Pre- and post-training assessment of training participants

| Name of place | Average of pre-test score (%) | Average of post-test score (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Najaf | 38.3 | 71.8 |

| Baghdad (Rusafa) | 35.1 | 56.1 |

| Basra | 42.6 | 60.6 |

| Baghdad(Karkh) | 39.7 | 57.9 |

| Baghdad (Kirkuk) | 46.1 | 64.4 |

| Baghdad (Dyala) | 41.5 | 51.9 |

| Erbil | 42.7 | 47.6 |

| Thi-Qar (Nasiryah) | 50.8 | 58.7 |

| Total | 42.3 | 59.0 |

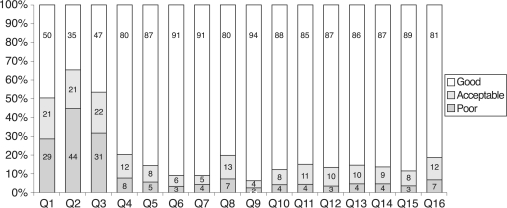

Figure 1 shows results of the course evaluation questionnaire. The participants' evaluation of the course demonstrates that nearly all participants found the course very good on all parameters, apart from aspects of notification about the course, information provided before the course and selection of the training venue, where views were more mixed.

Figure 1.

Histogram 1: course evaluation questionnaire

Detailed questionnaire information can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Course evaluation questionnaire

| Q1 | Timing of notification prior to the training course |

| Q2 | Information provided about training course before trainee arrived |

| Q3 | Selection of training venue |

| Q4 | Quality of training materials in relation to training objectives and course content |

| Q5 | Organisation of training course (length of lectures, timing of breaks etc.) |

| Q6 | Relationships among the training participants |

| Q7 | Relationship between trainees and trainers during the training |

| Q8 | Objectives of training courses were made clear to the participants |

| Q9 | Training courses met the stated objectives |

| Q10 | Training course topics were relevant to the objectives |

| Q11 | Training course contents were clear to the training participants |

| Q12 | Training course contents were well presented |

| Q13 | Training methods and approaches facilitated learning |

| Q14 | The training courses retained trainee's interest |

| Q15 | Sequence of training information presented |

| Q16 | The training courses enabled trainees to better perform their jobs |

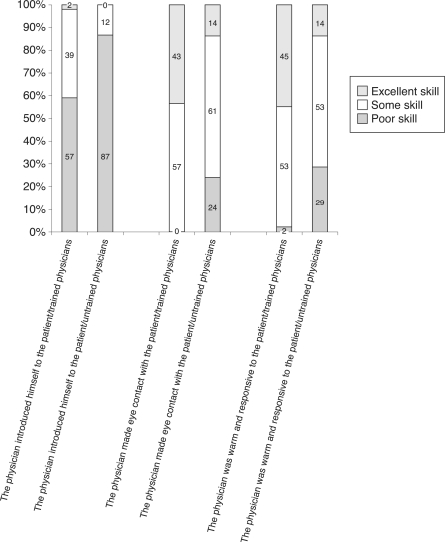

Figure 2 shows the psychiatrists' assessment of the physician's approach to the arrival of the patient. It can be seen that a greater proportion of the trained than the untrained physicians displayed excellent skills in relation to self-introduction, eye contact and responsiveness.

Figure 2.

Histogram 2: psychiatrists' assessment of patient arrival skills

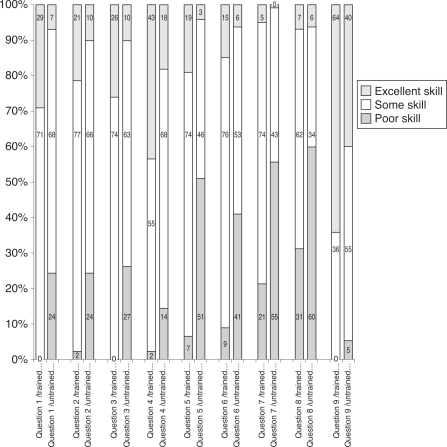

Figure 3 shows the psychiatrists' assessment in relation to the consultation itself. It shows that a greater proportion of the trained than the untrained physicians displayed excellent skills in relation to nine aspects of the consultation. Detailed information about consultation skills can be found in Table 5.

Figure 3.

Histogram 3: psychiatrists' assessment of consultation skills

Table 5.

Consultation skills

| Q1 | The physician listened to the patient's problems before he/she began asking questions |

| Q2 | The physician asked the patient what he/she thought was wrong |

| Q3 | The physician listened attentively to the patient's issues |

| Q4 | The physician asked questions |

| Q5 | The physician conducted a systematic review (appetite, weight, sleep patterns etc.) |

| Q6 | The physician asked open-ended questions |

| Q7 | The physician addressed non-verbal cues (weeping, tremors etc.) |

| Q8 | During the consultation, the physician kept notes |

| Q9 | The physician maintained a respectful attitude throughout the visit |

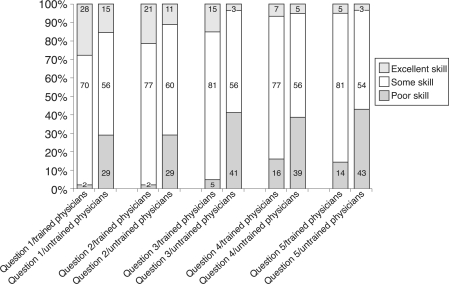

Figure 4 shows the psychiatrists' assessment in relation to diagnosis and establishment of a treatment plan. A greater proportion of the trained than the untrained physicians displayed excellent skills in relation to diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 4.

Histogram 4: psychiatrists' assessment of diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis and treatment details are set out in Table 6.

Table 6.

Diagnosis and treatment

| Q1 | The physician gave the patient a diagnosis |

| Q2 | The physician made a treatment plan |

| Q3 | The physician ensured the patient understood the treatment plan |

| Q4 | The physician gave the patient information (verbal or written) about the diagnosis |

| Q5 | The physician made a follow-up appointment with the patient, or encouraged the patient to make a follow-up appointment if they later felt that they wanted one |

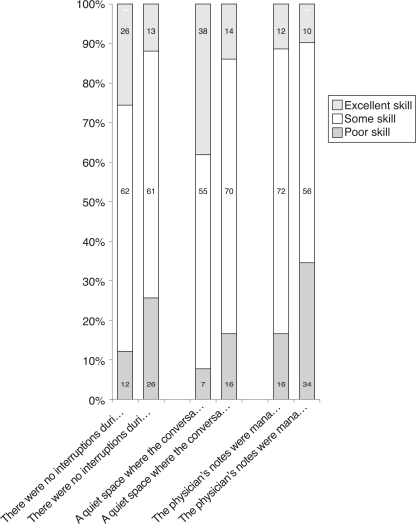

Figure 5 shows results of the job skills assessment carried out by the psychiatrists, in relation to the establishment of confidentiality and privacy. This indicates that the untrained groups were already fairly competent in this respect, and the training did not achieve such major gains as in other areas.

Figure 5.

Histogram 5: psychiatrists' assessment of confidentiality and privacy

Figure 6 shows the patients' assessment of the physicians' approach to the arrival of the patient. It shows that trained physicians were more likely to introduce themselves, make eye contact and be warm and responsive, although the differences were small.

Figure 6.

Histogram 6: physicians' performance on three patient arrival skills, as perceived by patients (patients of trained physicians – potp, patients of untrained physicians – poutp)

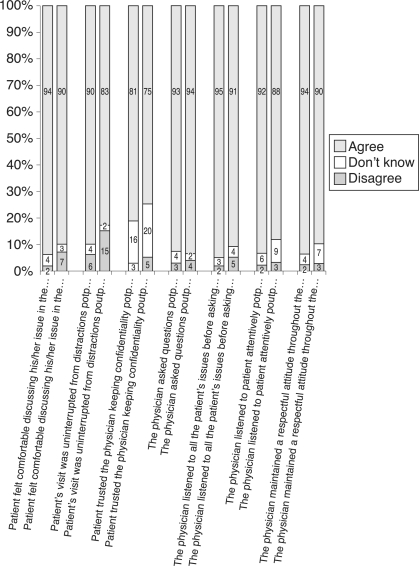

Figure 7 shows the patients' assessment of the physicians' consultation skills. These were generally better in trained than untrained physicians, although the differences again were small.

Figure 7.

Histogram 7: overall performance on the seven consultation skills of physicians, as perceived by patients (patients of trained physicians – potp, patients of untrained physicians – poutp)

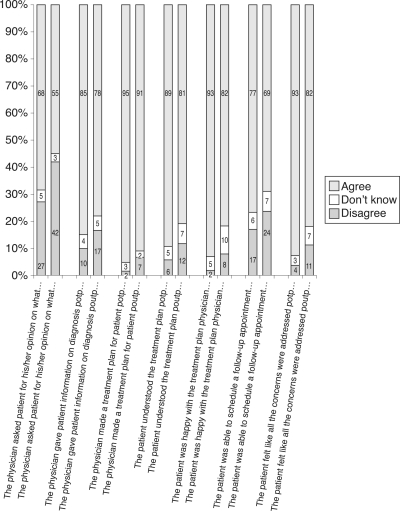

Figure 8 shows the patients' assessment of the diagnostic and treatment skills of the physicians. Similarly, these were better in trained than untrained physicians but again the differences were small.

Figure 8.

Histogram 8: physicians' performance on the seven treatment and diagnosis skills, as perceived by patients (patients of trained physicians – potp, patients of untrained physicians – poutp)

In relation to patient satisfaction, 72.4% of patients seen by trained physicians were satisfied with the information given to them about diagnosis and treatment, compared with 60.8% of patients seen by untrained physicians (p<0.001); 90.7% of patients seen by trained physicians were satisfied with their physician's ability to make a treatment plan compared to 80.3% of those seen by non-trained physicians (p<0.0001); 82.5% of patients seen by trained physicians felt they understood their treatment plan compared with 69.5% of patients seen by non-trained physicians (p<0.0001); and 84.8% of patients seen by trained physicians were happy with their treatment plan compared with 68.2% of those seen by untrained physicians. Overall, a higher proportion of patients of trained physicians reported overall satisfaction with the care received than did patients of non-trained physicians (85.6% vs 69.3%, p<0.001).

Discussion

This is an evaluation of a systematic attempt to train physicians working in primary care centres with a short but comprehensive mental health continuing professional development (CPD) course, within the context of integrating mental health into the national health sector strategic plans.

The study has demonstrated an increase in the knowledge of all trained participants, and a higher level of excellent skills in a subsample of trained physicians than in their untrained peers.

It is of methodological interest that the patient assessments found less difference between trained and untrained groups than the psychiatrist assessments, but all found that the trained group performed better than the untrained group of physicians.

The limitations of the study were first that the controls were chosen from the same practice, which, while controlling for contextual variables, meant that some crossover in skills could have occurred as trained physicians may have discussed their training with their untrained peers. Secondly, although the psychiatrists were initially blind to the training status of the physicians, their status may well have become apparent during the course of the evaluation process.

The evaluation methodology provides a comprehensive assessment of the value of the training and will enable us to fine-tune the training package. The overall outcome has been positive. Many trainees applied the training to other centres in the area, resulting in better communication and collaboration with specialised services and active engagement of the community, including schools, worship places, social services and civil society organisations.

The work is well integrated into the MoH strategy and policy documents. The MoH is continuing to fund the training programme and is extending it to cover the whole country. While the present minister is a psychiatrist, which has undoubtedly assisted the prioritisation of this work, it has been well embedded in the health system and is likely to continue over the coming years.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a systematic assessment of primary care training in Iraq. It has demonstrated that a two-week course has been able to achieve significant change, not only in knowledge, but also in subsequent demonstration of trained practitioners practical skills in the workplace compared with their untrained peers. Similar primary care training using the same course material (theory, role plays, discussions and good practice guidelines) adapted for each country has been carried out in Kenya13,14 and Nigeria,15 as well as Malawi, Oman and Pakistan (to be reported in due course). Primary care training using a variety of other methods is also being carried out in other countries in the region including Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain, Egypt,16 Saudi Arabia and Iran. Randomised controlled trials of the training are currently being undertaken in Malawi and Kenya. We are not aware of other evaluations similar to this one in Iraq yet being undertaken.

The challenges of integrating mental health into primary care are many and include the difficulty of ensuring adequate sustainable funding for a rolling programme of mental health CPD, ensuring provision to primary care of essential psychotropic medication, regular support and supervision from specialist carers, and inclusion of mental health in health management information systems etc. It is therefore always important to accompany primary care training programmes with sustained attention to these issues. In Iraq, the work has undoubtedly been more challenging because of the context of continued conflict in which policy makers and physicians have to operate in their daily lives.

Conclusion

A systematic training programme on mental health for primary care staff can be rolled out, even in complex conflict situations, and can achieve measurable improvements in physician behaviour, as assessed both by independent psychiatrists and by patients themselves.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to USAID and IMC Iraq for funding and supporting the program and to MOH staff for their support. Thanks also go to Mujibo Rahman for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Contributor Information

Sabah Sadik, Director of Training and Development, Ministry of Health, Baghdad, Iraq.

Saad Abdulrahman, Clinical Psychologist, Ministry of Health, Baghdad, Iraq.

Marie Bradley, Senior Mental Health Nurse, Leicester NHS Trust, UK.

Rachel Jenkins, Professor of Epidemiology and International Mental Health Policy and Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre, Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Bank. data.worldbank.org/country/iraq2010

- 2.Library of Congress, Federal Research Division Country Profile: Iraq. lcweb2.10c.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Iraq.pdf Library of Congress, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medact Enduring Effects of War: health in Iraq 2004. London: Medact, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadiq S, Al-Jadiry M. Mental health services in Iraq. International Psychiatry 2006;3:11–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health, Iraq. Ministry of Health Annual Report 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alhasnawi S, Sadik S, Rasheed M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS). World Psychiatry 2009;8:97–109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Jawadi A. Prevalence of childhood and early adolescent mental disorders among children attending primary health care centres in Mosul, Iraq: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2007;7:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care Alma Ata, USSR. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns B, Regier D, Goldberg I, Kessler L. Future directions in primary care/mental health care research. International Journal of Mental Health 1979;8:130–40 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepherd M. Mental health as an integrant of primary medical care. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 1980;30:657–64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Integrating Mental Health into Primary Care: a global perspective. www.who.int/mental_health/policy/Integratingmhintoprimarycare2008_lastversion.pdf

- 12.Sadik S, Bradley M, AL-Hasoon S, Jenkins R. Public attitudes to mental disorder in Iraq. International Journal for Mental Health Systems. Submitted 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins R, Kiima D, Njenga F, et al. Integration of mental health into primary care in Kenya. World Psychiatry In press 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins R, Kiima D, Okonji M, Njenga F, Kingora J, Lock S. Integration of mental health in primary care and community health workers in Kenya: context, rationale, coverage and sustainability. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2010;7:37–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gureje O. The WPA Train the Trainers workshop on mental health in primary care (Ibadan, Nigeria, 26 to 30 January 2009). World Psychiatry 2009;8:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins R, Heshmat A, Loza N, Siekkonen I, Sorour E. Mental health policy and development in Egypt: integrating mental health into health sector reforms 2001 to 2009. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2010;4:1–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.