Abstract

Thyroid hormone, operating through its receptors, plays crucial roles in the control of normal human physiology and development; deviations from the norm can give rise to disease. Clinical endocrinologists often must confront and correct the consequences of inappropriately high or low thyroid hormone synthesis. Although more rare, disruptions in thyroid hormone endocrinology due to aberrations in the receptor also have severe medical consequences. This review will focus on the afflictions that are caused by, or are closely associated with, mutated thyroid hormone receptors. These include Resistance to Thyroid Hormone Syndrome, erythroleukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal clear cell carcinoma, and thyroid cancer. We will describe current views on the molecular bases of these diseases, and what distinguishes the neoplastic from the non-neoplastic. We will also touch on studies that implicate alterations in receptor expression, and thyroid hormone levels, in certain oncogenic processes.

1. Preface

More than two thousand years ago, Aristotle discovered a link between castration and disruption of male maturation. Through extensive experimentation on bird and beast, he hypothesized that the testes were vital to the development of secondary male sex characteristics [1]. Excision of these organs drastically altered body size and behavior, as well as hair, feather, and horn growth [2]. These experiments were the earliest seeds of what would eventually become our current understanding of endocrinology. And from these same beginnings arose the recognition that aberrant endocrine signaling, through intentional intervention, accident, or pathogenic processes, could lead to disease.

Comprehension of endocrine signaling grew slowly over the next two millennia until the mid-19th century, which oversaw a dramatic expansion of research into endocrine glands and their secretions. With these studies came the first hints of methods to clinically intervene when normal endocrine homeostasis was disturbed. In 1849, Berthold discovered how to undo the deed of Aristotle, showing that castrated roosters regained their comb and wattle if the testes were surgically transplanted back into the abdominal cavity; Berthold correctly reasoned that the growth-enhancing compound in the testes must be soluble and blood-borne [3]. Similarly, the roles of the thyroid gland came to focus when Murray, in 1891, determined that a patient's symptoms (now known to be due to hypothyroidism) disappeared after grafting half of a sheep's thyroid beneath her skin. Because the patient's symptoms disappeared quickly after the operation, Murray surmised his patient's improvement could not be attributed to regained function of the sheep's gland but rather must be “due to the absorption of the juice of the healthy thyroid gland by the tissues of the patient” [4]. He later suggested that injections of thyroid gland extract would likely produce the same effect, a prediction subsequently confirmed by Baumann and Roos [5]. Graves reciprocally demonstrated that excessive thyroid gland activity leads to the pathological process now denoted hyperthyroidism [6]. In 1915, Kendall reported the successful isolation of thyroid hormone [7].

As more and more endocrine hormones were identified between the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, interest turned toward understanding not only their synthesis and chemical structures, but also their mechanisms of action within their target tissues. In the 1960s, Jensen et al. demonstrated that radiolabeled estrogen injected into female rats localized, in part, to reproductive target tissues, hinting at the existence of a tissue-specific receptor for this hormone [8, 9]. In 1973, Jensen et al. demonstrated that the estrogen/estrogen receptor (ER) complex shuttled from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and enhanced RNA synthesis in uterine tissue (Jensen et al. referred to it as an “alleviation of a deficiency in RNA synthesis”) [10]. This was one of the first indications that nuclear receptors could influence transcription, foreshadowing both the appellation of “nuclear” to the term “receptor” and the role of these receptors in gene regulation. Additional evidence for the participation of nuclear receptors in transcription control soon accumulated, extending this paradigm to glucocorticoids and thyroid hormones [11–19]. The molecular cloning of the cDNA for glucocorticoid receptor (GR) was reported in 1985, and, just a year later, the cDNAs for the human estrogen receptor and thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) were isolated and described [20–25]. Today, 48 members of the nuclear receptor family have been identified in humans, 49 in mice, 21 in flies, and 270 in worms [26–28].

This work ultimately led to the current model of endocrine signaling wherein minute amounts of potent compounds are carried from their site of synthesis through the blood to mediate distal physiological changes. In the cases of interest to us here, these compounds are small, lipophilic molecules derived from cholesterol (the androgens of Aristotle's observations), highly modified amino acids (the thyroid hormones), or a variety of other greasy compounds. Nuclear receptors within the target tissues are the regulatory ambassadors in this endocrine diplomacy: they receive extracellular information in the form of their cognate hormone, bind to specific target genes, collaborate with coregulatory partners, and initiate phenotypic change by altering the regulation of a broad array of gene targets [10, 29, 30]. We now know that nuclear receptors have a pervasive reach into nearly all aspects of animal biology and play key roles not only in endocrine signaling but also in metabolic and xenobiotic sensing [31–33]. In humans, frogs, flies, and likely every other form of metazoan life, nuclear receptors are key regulators of development, growth, metabolism, reproduction, homeostasis, and circadian rhythm. A recent hierarchical clustering analysis based on nuclear receptor expression, function, and physiology organized the known mouse nuclear receptors into six distinct clades that span steroidogenesis, reproduction, development, metabolism, and energy homeostasis [34].

Not surprisingly, departures from this normal pathway of endocrine signaling in humans have the potential to wreak developmental or physiological disorder and can require medical intervention. In the day-to-day routine of the clinical endocrinologist, these departures are most commonly the consequence of too little or too much hormone production. Although we will touch on these hormone deficiencies and excesses, the main topic of this paper lies on the other side of the equation: mutations in the nuclear receptors that receive the hormone signals, rather than defects in the hormone signals per se. This paper will introduce thyroid hormone endocrinology and discuss how thyroid hormone receptors function as members of the larger nuclear receptor family. We will then discuss the role of TR signaling in human disease, with an emphasis on endocrine and neoplastic disorders.

2. Normal Thyroid Hormone Endocrinology

2.1. The Signal

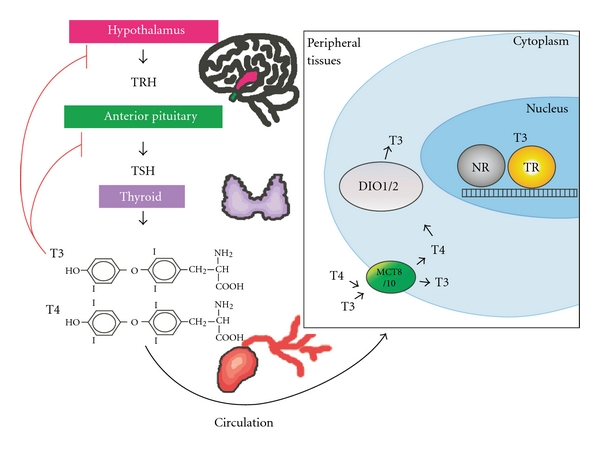

In a healthy individual, thyroid hormone is produced in response to a cascade of signals originating in the hypothalamus, which synthesizes thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) (Figure 1). TRH induces expression of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in the anterior pituitary, which induces, in turn, synthesis and release of T3/T4 thyronine by the follicular cells of the thyroid gland. T3 and T4 are the most abundant forms of thyroid hormone and are carried in the circulation chiefly as complexes with transthyretin, serum albumin, and thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) [42, 43]. On arrival at a responsive cell, T3 and T4 are transported across the cell membrane primarily by monocarboxylate anion transporters 8 and 10 (MCT8 and MCT10) [44, 45] (Figure 1). T4 can be converted to T3 by deiodinase type 2 (DIO2) found in a variety of other responsive tissues [46]. Although both T3 and T4 can bind to, and modulate the activity of, intracellular TRs, T3 is considerably more active than T4, leading many to view the latter as a prohormone [46]. Deiodination of T3 or T4 on their inner ring by deiodinase type 3 (DIO3) leads to their inactivation. Interestingly, DIO1, a third deiodinase found primarily in the liver and kidney, can remove iodines from either the outer or inner ring and therefore can alternatively generate or inactivate T3 [46]. It should be noted that several metabolic derivatives of thyroid hormone can signal through membrane-associated G-protein coupled receptors such as TAAR1 [47]; however, the TRs appear to represent the key receptors for T3 and T4 and are the focus of the remainder of this paper.

Figure 1.

Regulation of thyroid hormone synthesis and activity. TRH is produced in the hypothalamus (shown in pink) and stimulates the anterior pituitary (shown in green) to create TSH, which stimulates the follicular cells of the thyroid gland (purple) to produce T3 and T4. T3 and T4 circulate through the blood to the peripheral tissues (see box at right), where they are transported across the cell membrane into the cytoplasm by MCT8/MCT10 (green oval). T4 can be converted to T3 by deiodinase type 1 and deiodinase type 2 (DIO1/2, gray sphere). Both T3 and T4 can enter the nucleus and regulate TR activity. TR is shown here as a yellow sphere bound to DNA. On most sites, TRs can dimerize, either as homodimers or as heterodimers, with another nuclear receptor partner (NR, dark gray sphere).

2.2. The Receptor

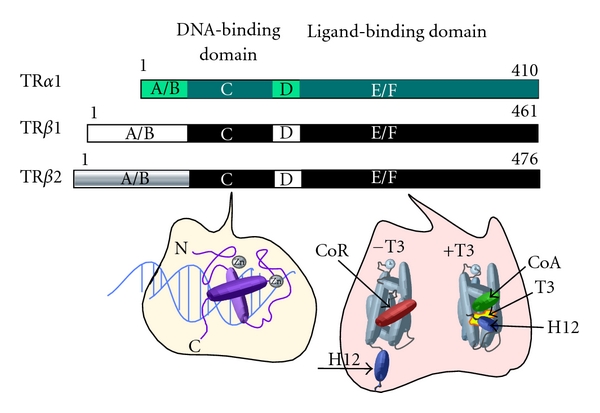

Once in a target cell, T3 and T4 bind to the TR subfamily of nuclear receptors. In common with virtually all members of the nuclear receptor family, TRs are composed of a shared architecture consisting of an N-terminal (A/B) domain that contains binding sites for transcriptional coregulators, a central DNA binding domain C responsible for target gene recognition, an intervening “hinge” domain (D), and a C-terminal, hormone-binding domain (E/F) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Domain comparison of different TR isoforms and schematic of DNA- and ligand-binding domain crystal structures. Each TR isoform is represented as a horizontal bar, from N to C termini. Total amino acid length is indicated at right [35, 36]. Within a given isoform, the location of each domain is lettered (A/B, C, D, and E/F). Identical domains of TRβ1 and TRβ2 are shown in matching colors. Note the unique A/B domain of TRβ2. Below left depicts the structure of the TR DNA-binding domain. α-helical domains are represented as purple cylinders and coordinating zinc atoms (Zn) as silver spheres. Below right depicts two conformations (−T3 and +T3) of the TR ligand-binding domain, which is composed of 12 α helices; the 12th helix (dark blue cylinder, labeled “H12”) contains the ligand-dependent activation domain. In the −T3 conformation, helix 12 is in an extended position and the corepressor binding groove is filled with the CoRNR-box helical motifs found in SMRT and NCoR (red cylinder, labeled “CoR”). In the +T3 conformation, helix 12 has rotated to close around T3 hormone ligand (shown in yellow), and a novel docking surface for the LXXLL motifs of a transcriptional coactivator has formed (green cylinder, labeled “CoA”).

2.2.1. The “A/B” Domain

The “A/B” domains of the TRs recruit an assortment of coregulatory proteins that can participate in ligand-independent transcription regulation and/or modify the hormone-dependent transcriptional properties of the E/F domain (see below) [48–51]. This region is also a target of a variety of phosphorylation events that modulate TR function [52]. Interestingly, the (A/B) domain of many nuclear receptors appears to posses little inherent secondary or tertiary structure but is thought instead to assume more ordered conformations on interaction with other proteins; it has been suggested that this induced fit phenomenon allows the (A/B) domain to adapt to different coregulators and to different cellular environments [53–57].

2.2.2. The “C” Domain

The “C” domain in TRs, in common with virtually all other nuclear receptors, is comprised of two, highly conserved α-helical domains that are oriented and stabilized through interactions with coordinated zinc atoms [58–61]. The first α-helix tucks into the major groove of DNA and interacts intimately with a cognate hexanucleotide sequence on the DNA [62–64] (Figure 2). The most crucial base-specific contacts are made by the “P-box” amino acids within this first α-helix, and nuclear receptors with different P-box amino acids recognize different hexanucleotide sequences [65–67]. TRs possess an EGKG P-box and bind most tightly to consensus AGGTCA DNA sequences in vitro but can recognize a variety of variations on this theme; the presence of nonconsensus sequences in nature are likely to contribute to the specificity of target gene recognition by TRs in vivo [68].

The second α-helix in the “C” domain lies orthogonal to the first α-helix and stabilizes the receptor-DNA interaction through both direct and water-mediated contacts with the DNA phosphodiester backbone [60]. Amino acids within or flanking the second a-helix (the D-box) also can serve as a receptor dimerization interface [60, 69]. In fact TRs can bind to DNA as receptor monomers, homodimers, or heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) or other members of the nuclear receptor family [70–74]. The best characterized TR DNA binding sites (“thyroid hormone response elements” or TREs) consist of two hexanucleotide sequences (half-sites) and bind a TR-TR or TR-RXR receptor dimer. The sequence, orientation, and spacing of the half-sites all contribute to proper TR recognition. In TRs, the second α-helix is followed by a short, flexible loop of amino acids and a third α-helix; this “C-terminal extension” helix both makes additional dimerization contacts and can contact the minor groove of the DNA, permitting recognition of an extended DNA sequence that includes bases 5′ to the historically defined hexanucleotide half-site [61, 75]. In addition to its role in DNA binding, the “C” domain also represents a docking surface for several known coregulatory proteins [76].

2.2.3. The “D” Domain

The “D” domain is thought to act as a flexible linker joining together the more conformationally and evolutionarily constrained “C” and “E/F” domains. TRs can recognize a surprising variety of half-site orientations, and the receptor “D” domain has been proposed to provide the rotational flexibility to accommodate the necessary twists and turns [70–74]. Consistent with this concept, different crystal structures of TR reveal different structural options for the “D” domain, either a flexible loop or a short α-helix, as it exists from the “C” domain [77]. The “D” domain also possesses key nuclear localization motifs and can participate in recruitment of several regulatory proteins, either alone or in conjunction with the other nuclear receptor domains [77–80].

2.2.4. The “E/F” Domain

The “E/F” domain of TRs binds the thyroid hormone. It also forms a second receptor dimerization surface and is a major site of coregulator interaction (Figure 2). Although less than 35% sequence identity is conserved among the “E/F” domains of different nuclear receptors, structural analysis reveals a highly shared canonical architecture composed of a triple laminate of α-helices surrounding a variable-sized hollow pocket lined with hydrophobic residues (Figure 2) [81–88]. This pocket varies in size and shape for different nuclear receptors, thereby defining their ligand specificity. A C-terminal α-helix (denoted helix 12 or H12) exists from this triple helical stack and forms a short, pivoting structure that can adopt different conformations depending on presence and character of the hormone ligand. Binding to hormone induces a “mouse-trap mechanism” whereby portions of the “E/F” domain constrict around the hormone, and H12 swings shut to close off the pocket [81, 89].

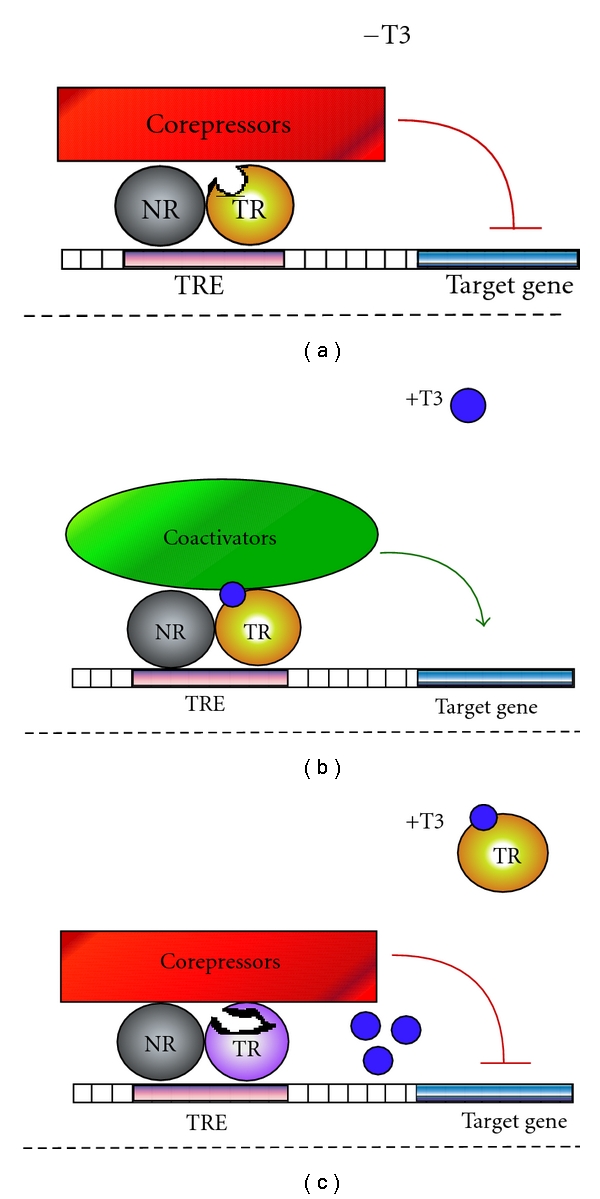

These hormone-driven conformational changes are the principal means by which ligand regulates TR-mediated transcriptional regulation (Figure 3). For example, the TR “E/F” domain possess a hydrophobic surface groove composed of portions of helices H3, H4, and H5 [90]. In the absence of hormone, this surface groove can interact with CoRNR-box helical motifs found in the SMRT and NCoR family of corepressors, resulting in recruitment of these corepressors. The corepressors, in turn, recruit deacetylases and additional histone modifiers that, by altering the chromatin template, lead to repression of transcription [91–94]. The reorientation of H12 that occurs in response to binding of hormone agonist occludes this corepressor docking surface, releasing corepressor and simultaneously forming a novel docking surface for the LXXLL motifs that are found in many transcriptional coactivators, such as SRC1 [90, 95–99] (Figure 2). These coactivators typically possesess associated histone acetyl and methyl transferase activities that, by appropriately modifying the chromatin, enhance transcription. Other coactivators include the Mediator complex (which helps recruit the general transcriptional machinery) and ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers (which regulate nucleosomal packaging). Differences in the shape and size of the hormone ligand can operate the H12 conformational toggle switch in different fashions; hormone antagonists, for example, induce H12 conformations that further stabilize corepressor binding and/or destabilize coactivator binding [100–102].

Figure 3.

Transcriptional activity of wild-type and dominant-negative TRs. (a) In the absence of T3, wild-type TR (orange sphere plus a grey homo- or heterodimer partner) binds to thyroid hormone response elements (TREs-, shown as pink rectangle on DNA), recruits a cohort of corepressor proteins (shown as a red rectangle), and represses transcription of a given target gene (blue rectangle). (b) In the presence of T3 (dark blue sphere), wild-type TRs undergo a conformational change and exchange corepressor proteins for coactivators (green oval) to activate transcription of a target gene. (c) Dominant-negative TR mutants (shown here as a disfigured lavender sphere) have defects in hormone binding, corepressor release, or coactivator recruitment and consequently repress transcription even in the presence of hormone and other wild-type TRs.

Although this H12-driven mechanism by which TRs bind corepressors in the absence of hormone and release corepressors and bind coactivators on binding to T3 is the best worked out paradigm (Figure 3), a substantial number of genes are regulated by TRs in the inverse fashion (activated in the absence and repressed in the presence of T3) [103–105]. Additional genes appear to be constitutively regulated up or down by TRs in a hormone-independent manner [37]. The precise basis for this diversity in the transcriptional response is incompletely understood, but it presumably reflects mechanisms by which the nature of the DNA binding site, and/or the presence of additional transcription factors on the target gene, can alter coregulator recruitment or function. It should be noted that thyroid hormone receptors not only operate as transcription factors but also mediate nonnuclear effects by interacting with other proteins; although not the focus of this review, this aspect of TR function will arise again in our discussion of the TRβ-PV mutant (Figure 4) [106].

Figure 4.

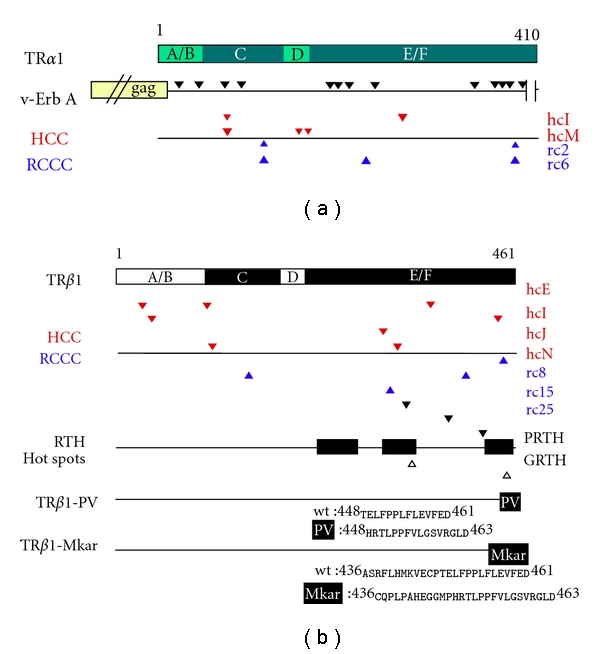

Oncogenic- and RTH-associated mutations in different TR isoforms. (a) A schematic of wild-type TRα1 is shown as a horizontal bar as in Figure 1; beneath, horizontal lines depict v-Erb A and several representative HCC/RCCC TRα1 mutants. As a result of fusion of retroviral gag-sequences, the N-terminus of v-erb A is 12 amino acids shorter than TRα1. V-erb A's 13 mutations are indicated by black arrowheads. From left to right, they are R24H, Y44C, G73S, K90T, K186R, P191L, P203L, K233N, T342S, P363S, T370A, C378Y, and F395S. A 9 amino-acid C-terminal deletion is indicated by vertical lines. All mutations and deletions are in relation to the avian TRα1 sequence [24]. Under the schematic for v-Erb A, red and blue arrowheads indicate mutations found in representative HCC and RCCC mutants, respectively, [37–39]. The nomenclature for each mutant is provided at the far right of the figure. For HCC, these mutants are hcI-TRα1 (K74E, A264V) and hcM-TRα1 (K74R, M150T, and E159K). For RCCC, these mutants are rc2-TRα1 (I116N and M388I) and rc6-TRα1 (I116N, A225T, and M388I). (b) A schematic of wild-type TRβ1 is shown as a horizontal bar as in Figure 1; beneath, horizontal lines depict several representative HCC/RCCC TRβ mutants, RTH hot spots, and the RTH mutant, TRβ1-PV. As above, red and blue arrowheads indicate representative mutations found in HCC and RCCC [37–39]. For HCC, these mutants are hcE-TRβ1 (M32I, C107R, and T368N), hcI-TRβ1 (S43L, C446R), hcJ-TRβ1 (M313I), and hcN-TRβ1 (K113N and T329P). For RCCC, these mutants are rc8-TRβ1 (F451S), rc15-TRβ1 (K155E, K411E), and rc25-TRβ1 (Y321H). Below the schematic for HCC/RCCC mutants, the locations of RTH hot spots are shown (amino acids 234–282, 310–353, and 429–460 [36]). Representative mutants for PRTH are: R338L, R383H, and R429Q. For GRTH, these mutations are G345S and P453S. The TRβ1-PV mutant has undergone a C-insertion at codon 448 that results in a frameshift at the C-terminus of the receptor [40]. The location of the 16 new PV-specific amino acids is indicated by a black box on the TRβ1-PV schematic, and the identities of these amino acids (and their wild-type TRβ1 counterparts) are shown below. The TRβ1-Mkar mutant has a T insertion at codon 436 that results in a frameshift at the C-terminus of the receptor. The locations of these new 28 amino acids are indicated by a black box on the TRβ1-Mkar schematic, and their identities are shown below. Note that Mkar shares with PV the amino acid sequence from codons 448 to 463 [41].

3. Diversification of Signal Reception: The TR Isoforms

TRs in humans are encoded by two distinct genetic loci: TRα on chromosome 17 and TRβ on chromosome 3. Alternative splicing and promoter usage produces additional diversity, leading to the synthesis of a series of TR “isoforms,” the most studied of which are TRα1, TRβ1, and TRβ2 [35, 106] (Figure 2). All three bind T3 and can modulate expression of target genes in response to this hormone (not all splice variants do so; the TRα2 splice form, e.g., does not bind T3 and appears to mediate a hormone-independent mode of transcriptional regulation [35, 106]). Though virtually all cells express some form of TR, the ratios of the different isoforms vary in different tissue types and during development [106, 107]. TRα1 is expressed in the early stages of embryonic development, and is widely distributed, although particularly abundant in skeletal muscle and brown fat. TRβ1, in contrast, appears later in development and is present at the highest levels in the liver and kidney. TRβ2 is restricted to the pituitary, hypothalamus, sensory cells in the inner ear, and in the cone cells of the retina [35, 106–110].

TR knockout mice have helped delineate each isoform's role in thyroid hormone action. Mice missing the TRα1 isoform, for example, have cardiac abnormalities and lower body temperatures, whereas TRβ−/− animals have hearing defects and a loss of negative feedback regulation of the hypothalamus/pituitary/thyroid axis (e.g., high T3/T4 and unsuppressed TSH and TRH levels) [111–114]. Of note, mice bearing genetic disruption of all TR isoforms also present with high circulating T3/T4 and unsuppressed TSH levels (apparently due to the loss of TRβ2 in the hypothalamus and pituitary) but otherwise display fewer systemic abnormalities than do the TRβ-specific isoform knockouts. Presumably the loss of the peripheral TRα1 and TRβ1 response in these combined knockout mice renders them resistant to the otherwise detrimental effects of their elevated T3/T4 levels [115, 116]. In fact, chemically or genetically induced hypothyroidism also presents as a much more severe syndrome than does the TRα/TRβ combined receptor knockout, indicating that the presence of unliganded TRs is more disruptive physiologically than is the complete lack of TR function. Taken as a whole, these genetic studies indicate that the different isoforms mediate both shared, and specific physiological and developmental functions and that TRs play major biological roles even in the absence of T3.

Although there appears to be significant overlap between the target genes regulated by the different TR isoforms, the detailed transcriptional response on a given gene can differ for each isoform [37, 117, 118]. For example, TRα1 can induce expression of certain genes more strongly than does TRβ1, whereas these isoforms confer nearly equal activity on other genes [37]. Similarly, TRβ2 fails to repress and instead activates certain genes under T3 conditions that confer repression by TRβ1 or TRα1 [50, 119–122]. These gene- and isoform-specific transcriptional responses are likely to reflect differences in the coregulatory factors that are recruited by each isoform once bound to a given target gene.

4. A Failed Response: TR Mutations and Resistance to Thyroid Hormone (RTH) Syndrome

Circulating T3/T4 levels are tightly controlled by a negative feedback loop wherein surges of thyroid hormone bind to TRs in the hypothalamus and pituitary, which then suppress TRH and TSH production and, as a consequence, repress further release of T3/T4 (Figure 1). Production of too much or too little thyroid hormone causes a number of clinically important endocrine disorders. In Graves' disease, for example, a hyperstimulated thyroid overproduces T3 leading to cardiac abnormalities, palpitations, fatigue, weight loss, dyspnea, myxedema, and muscle wasting [123, 124]. Conversely, insufficient T3 (hypothyroidism) produces depression, weight gain, edema, thickened speech, reduced cognition, cold intolerance, and, in a neonate, cretinism (a disorder marked by retarded physical and mental development) [124–126].

The consequences of over- or underproduction of circulating T3/T4 had been recognized for over a century when Refetoff et al., in 1967, reported an intriguing paradox in a study of two siblings with goiter, short stature, deafness, mutism, and bone deformations [127]. Although these symptoms shared several characteristics with hypothyroidism, both patients had high concentrations of thyroid hormone in the blood. Refetoff et al. suggested that the patients' tissues might be deficient in their ability to sense T3 and coined the phrase “Resistance to Thyroid Hormone (RTH) Syndrome: [127, 128]. This was soon confirmed, and, since then, RTH syndrome has been recognized as an autosomal dominant genetic disease that affects approximately 1 in 40,000 people worldwide [36, 129].

The vast majority of RTH cases have been traced to mutations in the TRβ isoform (Figure 4) [130–134]. As of 2010, at least 137 different RTH-TRβ mutations have been identified, distributed among more than 300 families [36, 128, 135–138]. Despite this genetic diversity, virtually all of these RTH-TRβ mutations appear to share one key property: they encode mutant receptors that function as dominant-negative inhibitors of wild-type TR function [36] (Figure 3). RTH syndrome is, in fact, largely a disease of heterozygotes, and it is believed that RTH-TR mutant receptors interfere with normal T3 signaling by competing with the wild-type TRs expressed in the same cells from the unaffected TR alleles. Only two cases of patients homozygous/hemizygous for the TRβ mutation have been published: one was the product of a cousin marriage, and the other was born to a mother with goiter and a father of indeterminable genotype [139, 140].

RTH-TRβ mutants can interfere with both wt TRα1 and wt TRβ1 functions and are likely to mediate both isoform-specific and nonspecific effects in vivo, depending on the tissue and on the target gene. Interestingly, no RTH mutations have been mapped to TRα in humans, and, when TRβ RTH mutations are artificially targeted to TRα1 in mice, they do not produce RTH but generate instead a distinct slew of neoplastic and metabolic defects [141–145]. Although less frequently cataloged, and presenting with distinct symptoms, genetic defects in the MCT8 transporter, or in the incorporation of selenocysteines into the active sites of deiodinases, can also lead to defects in thyroid hormone signaling [36, 44]. This paper, however, will focus on RTH syndromes that arise due to lesions in the TRβ gene.

The genetic lesions responsible for RTH syndrome cluster in several “hot spots” mapping within the “D” and “E/F” domains of TRβ and result in defects in the hormone-driven release of corepressors and acquisition of coactivators (Figure 4) [79, 146–149]. In many cases, these mutations map to the hormone binding pocket and impair or eliminate the ability of the RTH-TRβ mutant to bind T3/T4 [36]. Although somewhat more rare, additional RTH mutants have been identified that retain a near wild-type affinity for T3/T4 but are defective in the conformational machinery that couples hormone binding to corepressor release and/or coactivator recruitment [150]. For example, proline 453 in TRβ1 is an important pivot on which H12 reorients in response to hormone agonist (Figure 4). Different amino acid substitutions at P453 have been identified in multiple human RTH syndrome kindreds; RTH-TR mutants bearing these substitutions retain significant T3 binding, but nonetheless exhibit defects in corepressor release, presumably due to a failure of H12 to properly reorient in response to bound hormone [151–155].

It is important to note that the symptoms of RTH syndrome are not identical to those of either a homozygous or heterozygous null mutation of TRβ. Instead it is the ability of the RTH syndrome TRβ mutants to function as dominant-negatives that plays a critical role in producing the disease phenotype. Is it the failure of the mutant TRβ to release corepressor, or to bind coactivator, that leads to this dominant-negative phenotype? In most RTH mutants tested, experimental inhibition of corepressor binding by biochemical or genetic manipulation reduces dominant-negative activity [150, 156]. Consistent with these findings, RTH patients with TR mutants that interact weakly with corepressors generally have more minimal disease symptoms than those with a strong corepressor interaction [157]. Nonetheless, a defect in coactivator binding (rather than in corepressor release) represents the primary defect in at least one RTH-TR mutant [147] and appears to contribute to the dominant-negative phenotype exerted by several other RTH-TR mutants (see Pituitary Resistance, below). It is also important to note that there are multiple forms of corepressor, and RTH mutants can display alterations in corepressor selectivity, rather than global defects in corepressor release. For example, NCoR and SMRT are closely related corepressor paralogs found in many cells. Wild-type TRs preferentially interact with NCoR, whereas the Mkar RTH mutant of TRβ (representing a C-terminal frame shift mutation), significantly reduces NCoR binding, but results in an increase in the SMRT interaction (Figure 4) [41]. NCoR and SMRT also undergo alternative mRNA splicing, and several RTH-TRβ mutants differ from wtTRβs in their ability to bind to these different corepressor splice variants [38, 158, 159]. This point will be addressed again in our discussion of oncogenic versions of TR (below).

5. Different Paths to Resistance: Generalized versus Pituitary RTH Disease

RTH has been divided clinically into two main subtypes, generalized (GRTH) versus pituitary (PRTH) [118, 130, 160–164]. GRTH is characterized by a broad insensitivity to thyroid hormone; as a result GRTH patients display some characteristics suggestive of hypothyroidism (e.g., short stature, goiter, and hearing impairments, reflecting an impaired T3 hormone response in peripheral tissues) but also have inappropriately high circulating levels of T3 and T4 and nonsuppressed TSH (a consequence of a loss of negative feedback in the hypothalamus/pituitary/thyroid gland axis) [35]. In essence, GRTH patients make more T3 and T4 than normal, but “do not know it,” and present in some fashion as if they make too little. In contrast, in PRTH patients, negative feedback sensing in the hypothalamus/pituitary/thyroid gland is selectively impaired (resulting in high levels of circulated T3/T4), whereas the peripheral tissue response remains relatively intact (resulting in symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as cardiac palpitations, heat intolerance, and nervousness) [35, 165, 166]. Thus, PRTH patients make too much T3 and T4, and “do know it,” often to the point of peripheral thyrotoxicity.

These subtypes are not completely discrete: a given mutation can manifest as either GRTH or PRTH in different individuals, or within a given individual at different times [36]. Nonetheless certain RTH mutations are more often associated with one or the other form of disease, an observation that has been recently confirmed in a mouse knock-in model of PRTH syndrome [167]. Notably, the mutations most often associated with GRTH typically map to amino acid substitutions in the hormone binding or pivot/H12 domains of TRβ and can be explained conceptually through their potential to interfere with hormone binding, corepressor release, or coactivator recruitment. In contrast, the most extensively characterized PRTH mutations map to a set of three arginines that form charged clusters on the surface of the TR “E” domain. In normal TRs, these arginines have been implicated in stabilizing the overall conformation of the “E/F” domain and also as important contacts in receptor homodimerization [168, 169].

Several explanations have been advanced for how PRTH mutations might impair T3 negative feedback in the hypothalamus/pituitary/thyroid axis while sparing the T3 response in the peripheral tissues. One proposal focuses on the observations that (a) TRβ1 forms homodimers more efficiently than does TRβ2, (b) TR homodimers recruit corepressors more efficiently than do TR/RXR heterodimers, and (c) many PRTH mutations impair homodimerization but retain the ability to form heterodimers with RXRs [94, 167, 170–177]. By this scenario, the diminished homodimerization properties of the PRTH mutants would favor TR-mediated activation over TR-mediated repression, resulting in a loss of repression of T3 synthesis in the hypothalamus and pituitary (producing increases in circulating T3 levels), yet enhancing T3-mediated positive gene regulation, resulting in the symptoms of peripheral thyrotoxicity characteristic of PRTH.

Alternatively, it is known that the hypothalamus and pituitary express primarily the TRβ2 splice form, whereas most peripheral tissues, such as liver, muscles, and kidneys, express primarily TRβ1 [35, 106, 178–183]. TRβ2 displays an enhanced ability to respond to T3 than does TRβ1, a phenomenon that may permit the hypothalamus and pituitary to sense, and suppress, surges of T3 before these elevated hormone levels saturate the more widely distributed TRβ1 isoforms [122, 184]. TRβ1 and TRβ2 share the same “C,” “D,” and “E/F” domains, and so RTH mutations are expressed as both splice forms. We have suggested that PRTH mutations have a more severe impact on the T3 response of TRβ2 compared to their impact on TRβ1, resulting in an increase in thyroid hormone levels (due to the impaired TRβ2-mediated negative feedback response in the hypothalamus/pituitary) while nonetheless conferring a thyrotoxic effect in peripheral tissues (mediated by the less-impaired TRβ1 splice form) [122]. As is most often the case with competing scientific theories, it is likely that both models play a role in the actual genesis of PRTH disease.

6. A Still Darker Side to Aberrant T3 Sensing: TRs and Their Mutations in Oncogenesis

In an ironic twist of history, TRs were linked to cancer before they were ever recognized as endocrine receptors. The avian erythroblastosis retrovirus (AEV) was first identified in 1935 as a retrovirus that could induce erythroleukemias and fibrosarcomas in infected chickens [185]. By the early 1980s it was realized that the oncogenic proclivities of AEV mapped to two viral oncogenes, v-Erb A and v-Erb B, that worked together to induce oncogenic transformation [186–188]. In 1986, v-Erb A was shown to be a retrovirally acquired, mutated version of avian TRα1 (Figure 4) [24, 25], establishing the precedent that mutated versions of TR can participate in the initiation or progression of oncogenesis. Mutated versions of TRs have been subsequently linked to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), renal clear cell carcinoma (RCCC), pituitary adenomas, and thyroid malignancies (Figure 4) [189–192]. Conversely, wt TRs can function as tumor suppressors, and loss of wt TR expression has been associated with these and other tumors [193]. We will discuss these malignancies in turn.

6.1. V-Erb A

Acutely transforming retroviruses cause neoplasia by acquiring, mutating, and inappropriately expressing host cell genes involved in the control of normal cell proliferation or differentiation. AEV represents a model by which two virally acquired cell genes, v-Erb A and v-Erb B, cooperate to induce neoplasia [187, 194–196]. V-Erb B is a mutated version of the avian epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, a cell surface tyrosine kinase that induces a cascade of mitogenic signals in response to extracellular EGF [188, 197]. Through loss of its extracellular regulatory and C-terminal domain, compounded by internal point mutations, v-Erb B has acquired a constitutive kinase activity that can induce proliferation of immature erythroid cells and fibroblasts even in the absence of EGF. V-Erb A is, as noted above, a mutated version of chicken TRα1. However, in contrast to the constitutive activation seen for v-Erb B, the mutations in v-Erb A have turned the latter into a constitutive repressor [198–201]. V-Erb A cooperates with v-Erb B in oncogenesis by suppressing differentiation of AEV-infected erythroid cells and by promoting the growth and life span of AEV-infected fibroblasts.

The basis of the dominant-negative activity of v-Erb A is obvious on inspection: the H12 helix toggle switch critical for corepressor release and coactivator recruitment by the wt TRα1 is deleted from the v-Erb A coding region (Figure 4) [24, 25]. In addition to this C-terminal deletion, v-Erb A has sustained a fusion at its N-terminus with sequences derived from the retroviral “gag” protein and 13 internal amino acid substitutions (Figure 4) [24, 25]. Several of these substitutions map to the hormone binding pocket, virtually abolishing the ability to bind T3 and further favoring corepressor over coactivator binding, whereas others map to the “A/B” and “C” domains.

Thus, in many ways, one would expect v-Erb A to operate as a particularly virulent version of an RTH mutant. Why then does v-Erb A function in neoplasia, whereas the RTH mutants induce primarily endocrine disorders? Neither the avian origin nor the TRα1 isoform backbone of v-Erb A fully explains this phenomenon. Instead, the acquisition of oncogenesis by v-Erb A appears to result in large part from changes in its DNA recognition domains. V-Erb A has sustained two amino acid substitutions within the P- and D-boxes of the “C” domain that play crucial roles in DNA binding specificity, as well as two additional amino acid substitutions in the “A/B” domain that can modify DNA recognition by the adjacent “C” domain [202]. As a consequence, v-Erb A possesses an altered specificity for artificial DNA response elements in vitro compared to wt TRα1 and an altered target gene specificity in transfected cells [196, 203–207]. It is likely that the oncogenic properties of v-Erb A reflect these changes in DNA recognition, permitting the viral protein to target a distinct set of “neoplastic” genes that differ from the “endocrine” genes normally targeted by TRα1. These novel v-Erb A targets may include those regulated by other nuclear receptors (such as retinoic acid receptor), or by other, nonreceptor transcription factors [194]. Consistent with this proposal, replacement of portions of the “C” domain of v-Erb A with the corresponding wt TRα1 sequences severely inhibits oncogenic transformation by AEV [208]. It should be noted that these DNA binding domain mutations probably work together with the other mutations in v-Erb A that favor repression by deleting H12, inhibiting T3 binding, enhancing homodimer formation, and widening the ability of v-Erb A to bind to both SMRT and NCoR forms of corepressor [205].

6.2. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The neoplastic properties of v-Erb A were viewed as an obscure tidbit of avian retrovirology exotica until eerily analogous TR mutants were discovered in a variety of human tumors. The first among these was human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Worldwide, HCC ranks 5th out of all neoplasias for number of cases and third for number of deaths [209]. HCC can manifest as a medley of symptoms, including upper abdominal pain, weakness, weight loss, and jaundice [210]. Infection with hepatitis B or C virus is one of the major risk factors for HCC, along with cirrhosis, and exposure to aflatoxin, a highly mutagenic fungal compound often found in stores of contaminated grains or nuts [211].

Though the risk factors for HCC are known, the molecular mechanisms responsible for subsequent tumor initiation and progression are not fully understood. Alterations in a variety of tumor suppressors and oncogenes have been identified in HCC, as have a variety of chromosomal losses, gains, and translocations [212–216]. Most provocatively for the topic of this paper, however, is that TR mutants have been identified at high incidence in both HCC cell lines and in solid tumors [189, 217]. One study found that 65% of examined tumors had mutations in TRα and 76% had mutations in TRβ, with a significant subgroup of these tumors bearing mutations in both loci [189].

The HCC-TR mutants, when analyzed, resemble in many of their properties the RTH paradigm: they are impaired for transcriptional activation, many display defects in T3-driven corepressor release and/or coactivator binding, and the majority can function as dominant negative inhibitors of wild-type receptor activity in reporter gene assays (Figure 4) [39]. Unlike RTH syndrome, however, the TR mutations in HCC are not inherited, but instead arise de novo during the progression of the HCC tumors [189]. Also in stark contrast to RTH syndrome, the vast majority of HCC-TR mutants analyzed had sustained two or more genetic lesions, with at least one lesion located so as to impact DNA recognition (i.e., in the “A/B” or “C” domains). Indeed, two of the HCC-TR mutants studied were able to bind in vitro to DNA sequences not recognized by the wild-type receptors [39].

This suite of molecular defects suggested a potential role for these HCC-TR mutants in the mismanagement of transcription of genes not normally under T3 regulation. Gene expression analysis of hepatoma cell lines expressing specific HCC-TR mutants confirmed this supposition by demonstrating that these mutants regulate a distinct set of genes from that regulated by the corresponding wild-type receptors [37]. Analysis of the HCC-TR target gene set revealed several provocative features. A subset of genes normally regulated by wt TRs were not targeted by the HCC-TR mutants tested; conversely, the HCC-TR mutants regulated a panel of novel genes that were not targets of wt TR regulation. Several genes were targeted by each of the HCC-TR mutants, such as AGR2, DKK1, CDC7AL, and SLC2A2 and were repressed in both the absence and presence of hormone compared to the wild-type receptors [37]. Interestingly, HCC-TR target genes included not only genes that were constitutively repressed by the mutant receptors, as expected from prior reporter gene assays, but also genes that were constitutively activated, including GNG12, GPC3, and KCNAB2 [37]. At least several of these aberrantly regulated genes have been previously implicated in cancer [37]. Therefore, although the TR mutations associated with HCC appear to impede the ability of the receptor to respond to T3, they do not necessarily prevent the receptor from mediating hormone-independent transcriptional effects, both down and up.

Although the role of many of the HCC target genes in oncogenesis remains to be determined, it was notable that the HCC-TR mutants gained the ability to activate several genes known to play proproliferative roles (CSF1, NRCAM, and CX3CR1) and to repress several genes known to function as tumor suppressors (DKK1, TIMP3). Conversely, several potential proproliferative genes repressed by wt TRs were not repressed by the HCC-TR mutant (e.g., GPC3, expression of which has been linked to cell proliferation in liver), and several potential tumor suppressor genes activated by wt TR were not activated by the HCC-TR mutant (e.g., TIMP3) [37].

These findings further extended the conceptual model first put forward for v-Erb A: TR mutants associated with disease act, at least in part, as dominant-negative inhibitors of normal TR action. In the absence of any additional changes, these TR mutants can cause endocrine disorders such as RTH syndrome. Acquisition of yet-additional lesions that impact the DNA recognition domains of the receptor, as observed for v-Erb A and for the HCC-TR mutants described above, appears to unleash a previously cryptic oncogenic function in the TRs, permitting the mutant receptors to extend their regulatory reach to genes capable of contributing to leukemogenesis and hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Drawing this conceptual link between v-Erb A and the HCC-TR mutants tantalizingly closer, systemic expression of v-Erb A in transgenic mice under a β-actin promoter results in a high incidence of HCC [218].

Given the evidence that multiply mutated TRs contribute to multiple neoplastic diseases, are there other forms of cancer in which TRs might play a role? To address this question, we next turn our discussion to renal clear cell carcinomas.

7. The Internist's Tumor: Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCCC)

RCC accounts for ~3% of all adult malignant diseases [219]. In men, it is the 7th most commonly occurring cancer; in women, it is the 9th [220]. Once known as “the internist's tumor” for its ability to produce an assortment of internal maladies and symptoms (flank pain, blood in the urine, fever, and palatable abdominal masses, to name a few), RCC actually encompasses a diverse assortment of tumor subtypes [221]. The most common of these subtypes (~75–80%) is of the clear cell variety and is abbreviated RCCC (or ccRCC) [219]. The name is derived from the appearance of the cytoplasm after histological prep of cancer tissue: high lipid content results in a clear solution [219]. Risk factors for RCC include tobacco use, high body mass index, and hypertension [219, 222–226]. Though methods of detecting renal tumors have improved in recent years, worldwide incidence and mortality rates are on the rise [220]. Metastatic RCC is highly resistant to conventional treatments (chemotherapy, radiation, and hormone therapy) and survival outcomes after diagnosis are typically less than one year [220, 227]. Though understanding the molecular basis of this disease has greatly advanced treatment options, therapy-refractory tumors typically develop 6–15 months after initial clinical intervention [228].

Approximately 80% of RCCCs bear inactivating mutations in the von Hippel Lindau gene (VHL) [229]. VHL encodes the targeting component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which marks the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) for degradation. Normally, HIF functions as an oxygen-sensing transcription factor; under hypoxic conditions it activates an array of genes involved in the formation of new blood vessels [230–232]. When VHL is inactivated, HIF accumulates and proangiogenic factors are transcribed unchecked; this contributes to the highly vascular tumors characteristic of RCCC [233]. Additionally, VHL has been implicated in spindle misorientation and chromosome instability; a defective VHL protein may, therefore, drive formation of additional tumor-promoting mutations [234]. In RCCCs with this genetic root, one defective VHL allele is typically inherited, and the other is deleted or mutated somatically.

Although VHL inactivation is considered the predominant molecular change associated with development of RCCC, it alone is not sufficient to cause cancer in mice [235, 236]. It is likely that VHL inactivation serves as the first step towards tumorigenesis and that additional steps, or “hits,” are required for tumor progression [237]. In fact, an intriguing diversity of TR mutations, deletions, and aberrant mRNA expression patterns have been observed in RCCC. For example, an analysis of 71 RCCC tumors found characteristic deletions at 3p26 and 3p24, which are home to VHL and TRβ, respectively [238]. Analysis of TR mRNA expression in RCCC tumor tissues revealed a significant reduction of TRβ mRNA in the majority of samples tested (although paradoxically, TRβ mRNA was overexpressed in several samples) [239]. Reduction of TRα mRNA was also observed in several RCCC tumors, although complete loss of the TRα locus on chromosome 17 was rare [238–240]. And, of greatest relevance to the topic of this paper, mutations in both TR isoforms have been identified in ~40% of RCCC tumors examined, in TRα, TRβ, or both [190]. It is therefore likely that defects in TR function can serve as a 2nd hit that triggers, or participates in, the transition from renal cyst to clear cell carcinoma.

Ten different RCCC-TR mutants have been studied in molecular detail [190]. In common with HCC, the majority of these RCCC mutants contain more than one genetic lesion each, with at least one or more of these lesions frequently mapping to the “A/B” or “C” domains; nonetheless, no two identical TR mutations have been isolated to date from the two different forms of neoplasia. The majority of the RCCC-TR mutants tested display hormone binding and coregulator release/acquisition defects in vitro and can function as dominant negatives in reporter gene assays (Figure 4) [38]. Several RCCC-TR mutants also display a gain in their specificity for certain splice forms of SMRT and NCoR compared to the wild-type receptor [38]. The multiple genetic lesions carried by a given mutant receptor can work together to contribute to the overall dominant-negative phenotype [38].

Do the mutations in the “A/B” and “C” domains of the RCCC-TR mutants alter their DNA specificity? Consistent with this idea, nuclear extracts from RCCC tumors were found to be impaired in their ability to bind to consensus TREs compared to extracts from wt tissues [190]. Expression array analyses of cells stably transfected with RCCC mutant receptors are in progress to determine if there are changes in target gene specificity (Rosen, Chan, and Privalsky unpublished observations).

8. Thyroid Neoplasia

A third example of an association of a human neoplasia with mutations in the TR loci was revealed by studies of papillary thyroid malignancies. Almost 63% of these malignancies were found to have mutations in TRα, and a remarkable 94% in TRβ; in contrast 22% and 11% of thyroid adenomas bore mutations in these isoforms, respectively, and no mutations were found in normal thyroid controls [191, 241]. This pattern is most consistent with a role of the TR mutants in cancer progression, rather than initiation. Further analysis demonstrated that the majority of these mutated TRs lost transcriptional activation function and displayed dominant-negative activity when coexpressed with their normal TR counterparts [191, 241]. Many, but not all, of these mutants contained multiple genetic lesions, with one tumor possessing 5 different lesions within a single TRβ1 allele and another possessing 6 in TRα1 and 2 in TRβ1 [191]. In many of these mutants, lesions included at least one mutation within the “A/B” or “C” domains. The effects of these mutations on DNA binding in vitro, or target gene specificity in cells, have not been reported.

9. Potential Cracks in the Wall Separating RTH Syndrome from HCC, RCC, and Thyroid Malignancy

The narrative to this point may have led the unwary reader to the conclusion that the absence or presence of DNA binding domain mutations determines if a given dominant-negative TR mutant induces endocrine or neoplastic disease. However, there is some evidence that this phenomenon may not be absolute. Although not associated with overt neoplasia, RTH-TR mutations in humans often lead to goiter, a nonneoplastic hyperplasia of the thyroid gland in response to the loss of T3/T4 feedback regulation. Further, a very strong dominant-negative RTH-TRβ mutant, denoted PV and representing a frameshift at the C-terminus of the receptor, causes not only severe disruption of the pituitary-thyroid axis and goiter, but also TSH-omas, and metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma in homozygous-mutant mice [40, 242–245]. The “A/B” and “C” domains of the PV mutant are fully wild type in sequence (Figure 4), suggesting that strong, dominant-negative RTH-TR mutants may have an inherent oncogenic potential that is rarely displayed in humans (where homozygosity for the RTH mutation is very unusual) but can uncloak when presented with an appropriate opportunity.

Subsequent analysis of the PV/PV mutant mice revealed several mechanisms by which the mutant receptor appears to be mediating oncogenesis; significantly, none of these involved the classic mode of direct binding of the TR mutant receptors to DNA [163]. The PV mutant was found to heterodimerize with, and inhibit, another member of the nuclear receptor family, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, removing an antiproliferative signal [246, 247]. Many nuclear receptors exert nongenomic functions outside of the nucleus, and the PV mutant also induced one of these: the phosphatidyl-inositol 3 kinase/AKT pathway [248, 249]. The PV mutant also makes protein-protein interactions with β-catenin and pituitary tumor transforming gene protein, increasing levels of these proteins by inhibiting their degradation [249–252]. Finally, through protein-protein interactions with the CREB transcription factor, the PV-TRβ mutant was able to induce cyclin D1 [245]. These PV-TR studies raise the possibility that similar TR signaling pathways, unrelated to DNA recognition per se, may also play a role in HCC-TR and RCCC-TR oncogenesis.

10. Ups and Downs of Wild-Type TR Expression in Oncogenesis

The impact of TRs on neoplasia is not restricted to scenarios involving receptor mutants. Wild-type TRs can act as tumor suppressors in many contexts, and losses in wild-type receptor expression appear to precipitate, or otherwise contribute to, several classes of neoplasia. For example, a double knockout of both TRα and TRβ in mice results in a higher incidence of follicular thyroid carcinoma and increased aggressiveness in a skin cancer model [253, 254]. Changes in TRα1 levels have been shown in 49% of human gastric cancers analyzed by immunoblotting [193]. Reduction in TRβ1 levels or changes in subcellular localization have been reported in colorectal cancers [255]. In several cases these changes in TR expression levels were associated with alterations in the restriction pattern of the TR gene, suggesting that loss of expression might reflect an underlying genetic event. In other cases, TR expression appears to be suppressed epigenetically by hypermethylation of the promoter region of the TR gene; for example, biallelic inactivation of TRβ expression by promoter methylation has been found in human breast cancers [192, 256]. Notably, reintroduction of wild-type TRβ into HCC or mammary carcinoma cell lines that have lost endogenous TR expression retards proliferation, results in partial mesenchymal to epithelial transitions, and suppresses invasiveness, extravasation, and metastasis in nude mice [253, 257].

11. Thyroid Hormone Status and Cancer

As noted above, changes in TR expression and function are associated with a wide variety of neoplastic events. Can changes in thyroid hormone levels exert similar effects? Answering this question has proven to be complex and somewhat contentious. In clinical studies, hypothyroidism has been reported to correlate with a lower risk of primary mammary carcinoma and a reduction in progression to invasive disease [258]. Pharmacologically induced hypothyroidism has similarly been reported to yield an improved survival in glioblastoma when used together with tamoxifen [259]. Consistent with hypothyroidism being beneficial, T3 has been reported to induce the proliferation and invasiveness of several types of tumor-derived cells in culture or in xenograft models, including HCC-derived cells [253].

In contrast, however, other studies indicate that low thyroid hormone levels increase the risk of HCC in humans, and high T3/T4 are therapeutic [260]. Dating back to the late 18th century, administration of thyroid extract was often used in conjunction with oophorectomy as a treatment for breast cancer [261–263] though its efficacy was not well established [264]. More recently, T3, operating through TRβ1, has been shown to retard the proliferation, anchorage-independent growth, and invasiveness of mammary cancer cells in culture [265]. Similarly, long-term hypothyroidism in women has been associated with an elevated risk of HCC [266], whereas T3 administration can reduce HCC progression in animal studies [267], and T4 has shown some success in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer [268].

Clearly “results may vary!” It is likely that the impact of thyroid hormone differs in different types of cancer and may control different aspects of the same cancer (proliferation, differentiation, invasion, metastasis, apoptosis, and senescence) differently. For example, the investigators that have shown T3 to be promitogenic in rodent liver have also shown that T3 suppresses formation of preneoplastic nodules in a diethylnitrosamine rat model of HCC; T3 is therefore likely to be exerting both proproliferative and prodifferentiation effects on liver [269]. It is worth noting that T3 also induces both differentiation and proliferation in several other contexts, such as the gut [270]. As is virtually always true in science, more studies will be required to fully reveal all of the intricate web of biological processes regulated by T3 and its receptors.

References

- 1.Wilson JD, Roehrborn C. Long-term consequences of castration in men: lessons from the Skoptzy and the eunuchs of the Chinese and Ottoman courts. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(12):4324–4331. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes J, editor. The Complete Works of Aristotle. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berthold A. Transplantation der Hoden. Archiv fur Anatomie, Physiologie und Wissenschaftliche. 1849;16:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray GR. Note on the treatment of myxoedema by hypodermic injections of an extract of the thyroid gland of sheep. British Medical Journal. 1891;2:p. 796. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.1606.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann E, Roos EZ. übernahm er mit Albrecht Kossel die Leitung von Hoppe-Seylers. Zeitschrift für Physiologische Chemie. 1895;21:p. 481. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graves RJ. Clinical lectures. London Medical and Surgical Journal. 1835;7:516–517. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendall EC. Landmark article, June 19, 1915. The isolation in crystalline form of the compound containing iodin, which occurs in the thyroid. Its chemical nature and physiologic activity. By E.C. Kendall. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1983;250(15):2045–2046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen EV. Biological Activities of Steroids in Relation to Cancer. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macgregor JI, Jordan VC. Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacological Reviews. 1998;50(2):151–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen EV, Brecher PI, Numata M, Mohla S, De Sombre ER. Transformed estrogen receptor in the regulation of RNA synthesis in uterine nuclei. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1973;11:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(73)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tata JR, Widnell CC. Ribonucleic acid synthesis during the early action of thyroid hormones. Biochemical Journal. 1966;98(2):604–620. doi: 10.1042/bj0980604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringold GM, Yamamoto KR, Tomkins GM. Dexamethasone mediated induction of mouse mammary tumor virus RNA: a system for studying glucocorticoid action. Cell. 1975;6(3):299–305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ringold GM, Yamamoto KR, Bishop JM, Varmus HE. Glucocorticoid stimulated accumulation of mouse mammary tumor virus RNA: increased rate of synthesis of viral RNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1977;74(7):2879–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheidereit C, Geisse S, Westphal HM, Beato M. The glucocorticoid receptor binds to defined nucleotide sequences near the promoter of mouse mammary tumour virus. Nature. 1983;304(5928):749–752. doi: 10.1038/304749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payvar F, DeFranco D, Firestone GL. Sequence-specific binding of glucocorticoid receptor to MTV DNA at sites within and upstream of the transcribed region. Cell. 1983;35:381–392. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samuels HH, Shapiro LE. Thyroid hormone stimulates de novo growth hormone synthesis in cultured GH cells: evidence for the accumulation of a rate limiting RNA species in the induction process. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1976;73(10):3369–3373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spindler BJ, MacLeod KM, Ring J, Baxter JD. Thyroid hormone receptors. Binding characteristics and lack of hormonal dependency for nuclear localization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1975;250(11):4113–4119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spindler SR, Mellon SH, Baxter JD. Growth hormone gene transcription is regulated by thyroid and glucocorticoid hormones in cultured rat pituitary tumor cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257(19):11627–11632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pascual A, Casanova J, Samuels HH. Photoaffinity labeling of thyroid hormone nuclear receptors in intact cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257(16):9640–9647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollenberg SM, Weinberger C, Ong ES. Primary structure and expression of a functional human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA. Nature. 1985;318(6047):635–641. doi: 10.1038/318635a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinberger C, Hollenberg SM, Ong ES. Identification of human glucocorticoid receptor complementary DNA clones by epitope selection. Science. 1985;228(4700):740–742. doi: 10.1126/science.2581314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green S, Walter P, Kumar V. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: Sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature. 1986;320(6058):134–139. doi: 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene GL, Gilna P, Waterfield M. Sequence and expression of human estrogen receptor complementary DNA. Science. 1986;231(4742):1150–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.3753802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sap J, Munoz A, Damm K. The c-erb-A protein is a high-affinity receptor for thyroid hormone. Nature. 1986;324(6098):635–640. doi: 10.1038/324635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberger C, Thompson CC, Ong ES. The c-erb-A gene encodes a thyroid hormone receptor. Nature. 1986;324(6098):641–646. doi: 10.1038/324641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Burch PE, Cooney AJ, et al. Genomic analysis of the nuclear receptor family: new insights into structure, regulation, and evolution from the rat genome. Genome Research. 2004;14(4):580–590. doi: 10.1101/gr.2160004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Näär AM, Thakur JK. Nuclear receptor-like transcription factors in fungi. Genes and Development. 2009;23(4):419–432. doi: 10.1101/gad.1743009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sluder AE, Maina CV. Nuclear receptors in nematodes: themes and variations. Trends in Genetics. 2001;17(4):206–213. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily: a rosetta stone for physiology. Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;19(6):1429–1438. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambon P. The nuclear receptor superfamily: a personal retrospect on the first two decades. Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;19(6):1418–1428. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The many faces of PPARγ. Cell. 2005;123(6):993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukherjee S, Mani S. Orphan nuclear receptors as targets for drug development. Pharmaceutical Research. 2010;27:1439–1468. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schupp M, Lazar MA. Endogenous ligands for nuclear receptors: digging deeper. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(52):40409–40415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.182451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bookout AL, Jeong Y, Downes M, Yu RT, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126(4):789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of Thyroid hormone action. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(3):1097–1142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Refetoff S, Dumitrescu AM. Syndromes of reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormone: genetic defects in hormone receptors, cell transporters and deiodination. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;21(2):277–305. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan IH, Privalsky ML. Isoform-specific transcriptional activity of overlapping target genes that respond to thyroid hormone receptors α1 and β1. Molecular Endocrinology. 2009;23(11):1758–1775. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen MD, Privalsky ML. Thyroid hormone receptor mutations found in renal clear cell carcinomas alter corepressor release and reveal helix 12 as key determinant of corepressor specificity. Molecular Endocrinology. 2009;23(8):1183–1192. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan IH, Privalsky ML. Thyroid hormone receptors mutated in liver cancer function as distorted antimorphs. Oncogene. 2006;25(25):3576–3588. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parrilla R, Mixson AJ, McPherson JA, McClaskey JH, Weintraub BD. Characterization of seven novel mutations of the c-erbAβ gene in unrelated kindreds with generalized thyroid hormone resistance. Evidence for two ’’hot spot’’ regions of the ligand binding domain. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88(6):2123–2130. doi: 10.1172/JCI115542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu SY, Cohen RN, Simsek E, et al. A novel thyroid hormone receptor-β mutation that fails to bind nuclear receptor corepressor in a patient as an apparent cause of severe, predominantly pituitary resistance to thyroid hormone. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(5):1887–1895. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schussler GC. The thyroxine-binding proteins. Thyroid. 2000;10(2):141–149. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton JA, Benson MD. Transthyretin: a review from a structural perspective. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2001;58(10):1491–1521. doi: 10.1007/PL00000791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heuer H, Visser TJ. Minireview: pathophysiological importance of thyroid hormone transporters. Endocrinology. 2009;150(3):1078–1083. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Der Deure WM, Peeters RP, Visser TJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone transporters, including MCT8, MCT10, and OATPs, and the effects of genetic variation in these transporters. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2010;44(1):1–11. doi: 10.1677/JME-09-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gereben B, Zeöld A, Dentice M, Salvatore D, Bianco AC. Activation and inactivation of thyroid hormone by deiodinases: local action with general consequences. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2008;65(4):570–590. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zucchi R, Chiellini G, Scanlan TS, Grandy DK. Trace amine-associated receptors and their ligands. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;149(8):967–978. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hadzic E, Desai-Yajnik V, Helmer E, et al. A 10-amino-acid sequence in the N-terminal A/B domain of thyroid hormone receptor α is essential for transcriptional activation and interaction with the general transcription factor TFIIB. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(8):4507–4517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oberste-Berghaus C, Zanger K, Hashimoto K, Cohen RN, Hollenberg AN, Wondisford FE. Thyroid hormone-independent interaction between the thyroid hormone receptor β2 amino terminus and coactivators. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(3):1787–1792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang Z, Privalsky ML. Isoform-specific transcriptional regulation by thyroid hormone receptors: hormone-independent activation operates through a steroid receptor mode of coactivator interaction. Molecular Endocrinology. 2001;15(7):1170–1185. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian H, Mahajan MA, Chun TW, Habeos I, Samuels HH. The N-terminal A/B domain of the thyroid hormone receptor-β2 isoform influences ligand-dependent recruitment of coactivators to the ligand-binding domain. Molecular Endocrinology. 2006;20(9):2036–2051. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weigel NL. Steroid hormone receptors and their regulation by phosphorylation. Biochemical Journal. 1996;319(3):657–667. doi: 10.1042/bj3190657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams M, Reginato MJ, Shao D, Lazar MA, Chatterjee VK. Transcriptional activation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is inhibited by phosphorylation at a consensus mitogen-activated protein kinase site. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(8):5128–5132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar R, Lee JC, Bolen DW, Thompson EB. The conformation of the glucocorticoid receptor af1/tau1 domain induced by osmolyte binds co-regulatory proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(21):18146–18152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wardell SE, Kwok SC, Sherman L, Hodges RS, Edwards DP. Regulation of the amino-terminal transcription activation domain of progesterone receptor by a cofactor-induced protein folding mechanism. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25(20):8792–8808. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.8792-8808.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chandra V, Huang P, Hamuro Y, et al. Structure of the intact PPAR-γ-RXR-α nuclear receptor complex on DNA. Nature. 2008;456(7220):350–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar R, Litwack G. Structural and functional relationships of the steroid hormone receptors’ N-terminal transactivation domain. Steroids. 2009;74(12):877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freedman LP, Luisi BF, Korszun ZR, Basavappa R, Sigler PB, Yamamoto KR. The function and structure of the metal coordination sites within the glucocorticoid receptor DNA binding domain. Nature. 1988;334(6182):543–546. doi: 10.1038/334543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luisi BF, Xu WX, Otwinowski Z, Freedman LP, Yamamoto KR, Sigler PB. Crystallographic analysis of the interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with DNA. Nature. 1991;352(6335):497–505. doi: 10.1038/352497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rastinejad F, Perlmann T, Evans RM, Sigler PB. Structural determinants of nuclear receptor assembly on DNA direct repeats. Nature. 1995;375(6528):203–211. doi: 10.1038/375203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaffer PL, Gewirth DT. Structural basis of VDR-DNA interactions on direct repeat response elements. EMBO Journal. 2002;21(9):2242–2252. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smit-McBride Z, Privalsky ML. DNA sequence specificity of the v-erb A oncoprotein/thyroid hormone receptor: role of the P-box and its interaction with more N-terminal determinants of DNA recognition. Molecular Endocrinology. 1994;8(7):819–828. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.7.7984144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nelson CC, Hendy SC, Faris JS, Romaniuk PJ. The effects of P-box substitutions in thyroid hormone receptor on DNA binding specificity. Molecular Endocrinology. 1994;8(7):829–840. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.7.7984145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nelson CC, Hendy SC, Faris JS, Romaniuk PJ. Retinoid X receptor alters the determination of DNA binding specificity by the P-box amino acids of the thyroid hormone receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(32):19464–19474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Umesono K, Evans RM. Determinants of target gene specificity for steroid/thyroid hormone receptors. Cell. 1989;57(7):1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Claessens F, Gewirth DT. DNA recognition by nuclear receptors. Essays in Biochemistry. 2004;40:59–72. doi: 10.1042/bse0400059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khorasanizadeh S, Rastinejad F. Nuclear-receptor interactions on DNA-response elements. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2001;26(6):384–390. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phan TQ, Jow MM, Privalsky ML. DNA recognition by thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors: 3,4,5 rule modified. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2010;319(1-2):88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Nuclear receptors. How to finger DNA. Nature. 1995;375(6528):190–191. doi: 10.1038/375190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurokawa R, Yu VC, Naar A, et al. Differential orientations of the DNA-binding domain and carboxy-terminal dimerization interface regulate binding site selection by nuclear receptor heterodimers. Genes and Development. 1993;7(7 B):1423–1435. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lazar MA, Berrodin TJ, Harding HP. Differential DNA binding by monomeric, homodimeric, and potentially heteromeric forms of the thyroid hormone receptor. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1991;11(10):5005–5015. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Näär AM, Boutin JM, Lipkin SM, et al. The orientation and spacing of core DNA-binding motifs dictate selective transcriptional responses to three nuclear receptors. Cell. 1991;65(7):1267–1279. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90021-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wahlstrom GM, Sjoberg M, Andersson M, Nordstrom K, Vennstrom B. Binding characteristics of the thyroid hormone receptor homo-and heterodimers to consensus AGGTCA repeat motifs. Molecular Endocrinology. 1992;6(7):1013–1022. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.7.1324417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Forman BM, Casanova J, Raaka BM, Ghysdael J, Samuels HH. Half-site spacing and orientation determines whether thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors and related factors bind to DNA response elements as monomers, homodimers, or heterodimers. Molecular Endocrinology. 1992;6(3):429–442. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.3.1316541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen Y, Young MA. Structure of a thyroid hormone receptor DNA-binding domain homodimer bound to an inverted palindrome DNA response element. Molecular Endocrinology. 2010;24(8):1650–1664. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mathur M, Tucker PW, Samuels HH. PSF is a novel corepressor that mediates its effect through Sin3A and the DNA binding domain of nuclear hormone receptors. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21(7):2298–2311. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2298-2311.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nascimento AS, Dias SMG, Nunes FM, et al. Structural rearrangements in the thyroid hormone receptor hinge domain and their putative role in the receptor function. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;360(3):586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Busch K, Martin B, Baniahmad A, Renkawitz R, Muller M. At least three subdomains of v-erbA are involved in its silencing function. Molecular Endocrinology. 1997;11(3):379–389. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.3.9903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Safer JD, Cohen RN, Hollenberg AN, Wondisford FE. Defective release of corepressor by hinge mutants of the thyroid hormone receptor found in patients with resistance to thyroid hormone. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(46):30175–30182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aranda A, Pascual A. Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(3):1269–1304. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Renaud JP, Rochel N, Ruff M, et al. Crystal structure of the RAR-γ ligand-binding domain bound to all-trans retinoic acid. Nature. 1995;378(6558):681–689. doi: 10.1038/378681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wagner RL, Apriletti JW, McGrath ME, West BL, Baxter JD, Fletterick RJ. A structural role for hormone in the thyroid hormone receptor. Nature. 1995;378(6558):690–697. doi: 10.1038/378690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]