Abstract

Objective

To describe the osteoarthritis study population of CHECK (Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee) in comparison with relevant selections of the study population of the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) based on clinical status and radiographic parameters.

Methods

In The Netherlands a prospective 10-year follow-up study was initiated by the Dutch Arthritis Association on participants with early osteoarthritis-related complaints of hip and/or knee: CHECK. In parallel in the USA an observational 4-year follow-up study, the OAI, was started by the National Institutes of Health, on patients with or at risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. For comparison with CHECK, the entire cohort and a subgroup of individuals excluding those with exclusively hip pain were compared with relevant subpopulations of the OAI.

Results

At baseline, CHECK included 1002 participants with in general similar characteristics as described for the OAI. However, significantly fewer individuals in CHECK had radiographic knee osteoarthritis at baseline when compared with the OAI (p<0.001). In contrast, at baseline, the CHECK cohort reported higher scores on pain, stiffness and functional disability (Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index) when compared with the OAI (all p<0.001). These differences were supported by physical health status in contrast to mental health (Short Form 36/12) was at baseline significantly worse for the CHECK participants (p<0.001).

Conclusion

Although both cohorts focus on the early phase of osteoarthritis, they differ significantly with respect to structural (radiographic) and clinical (health status) characteristics, CHECK expectedly representing participants in an even earlier phase of disease.

Osteoarthritis is the most common diagnosis made in older patients with knee or hip pain. The diagnosis can be based on symptoms, signs and radiographic findings, and as such can be defined by various sets and combinations of criteria.1,2 The prognosis of osteoarthritis for the individual patient is uncertain; the course of symptoms, clinical signs, disability and radiographic changes is difficult to predict.3 Besides, it has been demonstrated that there is inconsistency between the radiographic change and severity of joint pain with accompanying disability.4 Clearly, to understand more about the disease and its course, large independent detailed observational studies starting (very) early in the stage of the disease are necessary.

Therefore, in The Netherlands, a prospective 10-year follow-up study was recently initiated by the Dutch Arthritis Association in order to establish the onset and progression of osteoarthritis in participants with early complaints of hip and/or knee pain: CHECK (Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee), using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework. The ICF model provides an integrative framework, combining biological, psychological and social aspects of health and disease.5 The objective of CHECK is to study the course of complaints, the mechanisms that cause joint damage and to identify markers for the diagnosis and course of joint damage, as well as to identify prognostic factors that predict and explain the course of osteoarthritis. In parallel, an observational study on osteoarthritis was initiated by the National Institutes of Health: the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI). This 4-year follow-up study will create a public archive of data, biological samples and joint images to study the natural history of, and risk factors for, the onset and progression of knee osteoarthritis. In fact, both initiatives, CHECK and the OAI, seek answers to the same questions in comparable populations. In the present report the CHECK population is described at baseline and compared with relevant subpopulations of the OAI to provide a basis for further research and a comparison of both cohorts in the future.

METHODS

CHECK cohort

Design

From October 2002 to September 2005 a cohort was formed of 1002 participants with pain and/or stiffness of the knee and/or hip, which is to be followed prospectively for a period of at least 10 years. Nationwide, 10 general and academic hospitals in The Netherlands are participating, located in urbanised and semi-urbanised regions. The study was approved by the medical ethics committees of all participating centres, and all participants gave their written informed consent before entering the study.

Study population

General practitioners (GP) in the surroundings of the participating centres were invited to refer eligible persons to these centres. All patients that visited the GP on their own initiative, potentially fulfilling the inclusion criteria, were referred to one of the 10 participating centres. In addition, participants were recruited through advertisements and articles in local newspapers and on the Dutch Arthritis Association website. The physicians in the participating centres checked whether referred patients as well as patients from their outpatient clinics fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Individuals were eligible if they had pain and/or stiffness of the knee and/or hip, were aged 45–65 years, and had never or not longer than 6 months ago visited the GP for these symptoms for the first time.

Exclusion criteria were: any other pathological condition that could explain the existing complaints (eg, other rheumatic disease, previous hip or knee joint replacement, congenital dysplasia, osteochondritis dissecans, intra-articular fractures, septic arthritis, Perthes’ disease, ligament or meniscus damage, plicasyndrome, Baker’s cyst) or co-morbidity that did not allow physical evaluation and/or follow-up of at least 10 years, malignancy in the past 5 years and inability to understand the Dutch language.

Baseline measurements

Variables categorised according to the ICF model (table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment of the variables, categorised according to the dimensions of the ICF, comparison of CHECK and OAI

| CHECK | OAI | |

|---|---|---|

| Body function and structures | Physiological functions of body systems and anatomical part of the body | |

| Articular factors | Single PA view TFJ, mediolateral view TFJ, bilateral skyline view PFJ | Bilateral PA view TFJ AP view pelvis |

| AP pelvis view, faux profil view of hip | PA view dominant hand | |

| Kinesiological factors | Pain during joint motion of the hip and knee. Assisted active range of joint motion of the hip and knee (in degrees) with a goniometer |

Knee flexion pain/tenderness |

| Knee | Palpable warmth, refill test, bony tenderness, crepitus, patellofemoral grinding test | Effusion, bony tenderness, crepitus patellar tenderness, alignment, medial-lateral laxity |

| Hip | Sign of Thomas | NA |

| Hand | DIP and PIP bony enlargements | DIP bony enlargements |

| Pain | Pain scale of WOMAC | Pain scale WOMAC |

| Knee/hip pain intensity 0–10 rating scale | Knee pain 0–10 rating scale KOOS knee pain and symptoms |

|

| Stiffness | Stiffness scale WOMAC | Stiffness scale WOMAC |

| Other joint symptoms | Hip pain, stiffness Foot/toe symptoms |

Symptoms of hip, shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand/ finger, ankle, foot/toe |

| Fatigue | Vitality scale of the SF-36-item health status survey questionnaire | NA |

| Activities | Execution of a task or action by an individual | |

| Limitations in activity | Functioning scale WOMAC | Functioning scale WOMAC |

| Participation | Involvement in life situation | |

| Working status | Employment, current and past | Employment, current and past |

| Participants with paid employment were asked whether they would like to change their working environment | Work disability due to health problems | |

| Environmental and personal factors | Complete background of an individual’s life and living situation | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, household composition | Age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, residency, income |

| Height, weight, education | Height, weight, education | |

| Utility | EuroQol | |

| Quality of life | SF-36 | SF-12, KOOS quality of life |

| Co-morbidity | List of complaints and diseases | Comorbidity index |

| Psychological factors | ||

| Pain coping | Pain coping inventory | NA |

| Fear and depression | Scale form the SF-36: emotional role—functioning | CES-D (depressive symptoms) |

| Social support | Social support scale | NA |

| Physical workload | Based on the Dutch Musculoskeletal Questionnaire | Frequent knee bending activities |

| Physical activity during leisure | Physical activity, qualitative and quantitative | KOOS sport, recreation Physical activity (PASE) Limitation of activity due to knee symptoms |

| Healthcare use | Medical consumption, to have and use aids | Medication consumption |

| Lifestyle | Tobacco, alcohol use | Tobacco, alcohol use |

| Changes in feeding habits | Dietary nutrient intake | |

AP, anteroposterior; CHECK, Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee; KOOS, Knee Outcomes in Osteoarthritis Survey; NA, not available; OAI, Osteoarthritis Initiative; PA, posterioranterior; PASE, physical activity scale for the elderly; PFJ, patellofemoral joint; SF-12, Short Form 12-item medical outcome study; SF-36, Short Form 36-item health status survey questionnaire; TFJ, tibiofemoral joint; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index.

Body function and structures: articular and kinesiological factors

To assess cartilage and bone at baseline, imaging techniques were employed and samples of blood and urine collected. During follow-up this is also done at 2, 5, and 10 years. At baseline both knees and hips were analysed in all participants, independent of symptoms and signs.

Radiographs of the tibiofemoral joints (TFJ) were made by a weight-bearing posteroanterior (PA) view, semi-flexed (7–10°) according to Buckland-Wright and colleagues.6–8 Radiographs of the patellofemoral joints were made by a single standing mediolateral view in 30° flexion and a skyline (inferior superior) view in 30° flexion.9,10 For the hip, weight-bearing antero-posterior (AP) radiographs of the pelvis were made.11,12 In addition, a weight-bearing single faux profile radiograph of both hips was obtained.13

All radiographs were made without fluoroscopy, and were digitalised and centrally stored. Radiographs of PA TFJ and AP pelvic views at baseline were scored according to Kellgren and Lawrence (K&L).14 Blood and urine samples were collected, using a standardised protocol at all sites. Multiple aliquots of serum, plasma and urine were centrally stored at −80°C. DNA was collected at baseline and was stored at −20°C.

Kinesiological factors (table 1) were assessed each year by a protocol that was established to measure clinical features of knee, hip, and hands.

Body function and structures: pain, stiffness, and fatigue

Questionnaires were selected based on the following criteria: validated in participants with osteoarthritis; demonstrated reliability, validity and, if applicable, responsiveness; the questionnaire is internationally accepted, is available in the Dutch language and has a high feasibility. Questionnaires are administered annually.

The Western Ontario and McMaster osteoarthritis index (WOMAC),15–17 a questionnaire with well-known and good clinimetric properties and recommended by OMERACT is utilised to measure pain (five items), stiffness (two items) and physical functioning (see below).18,19 The five point Likert version of the WOMAC was used; item responses range from “none” to “extreme” and are summed to produce subscales (pain 0–20, stiffness 0–8, functioning 0–68) with higher scores indicating worse health.

Fatigue was assessed with the vitality subscale of the Short Form 36-item health status survey questionnaire (SF-36). This questionnaire is a generic instrument yielding scores on eight scales, with two summary scores, the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS). The physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health and bodily pain scale contributes most to the scoring of the PCS. The mental health, role limitations due to emotional problems and social functioning scales contributes most to the MCS. These summary scores of the SF-36 are equivalent to the summary scores of the SF-12,20 as used in the OAI. Scores on the scales range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a better health-related quality of life.21

Activities

The WOMAC was used to assess physical functioning (17 items).18,19

Participation

To assess the involvement in life situation, employment and leisure activities were measured with the questionnaire from the Patient Panel Chronic Diseases (The Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research; NIVEL) and the questionnaire “economic aspects in rheumatoid arthritis”.22

Environmental factors and personal factors

Table 1 provides an overview of the environmental and personal factors collected at baseline. Co-morbidity was assessed with a standard consensus-based list.23 Pain-coping behaviour was measured with the pain coping inventory, assessing both behavioural and cognitive coping strategies.24 To assess a person’s distress and fear, a subscale of the SF-36 was used. Social support was measured with the Dutch “social support scale”.25 Physical load and economic consequences were assessed with the Dutch musculoskeletal questionnaire and the questionnaire “economic aspects in rheumatoid arthritis”, respectively.22,26

Every 3 months, the 10 institutes were visited by a single central coordinator to support complete and accurate data gathering.

Osteoarthritis Initiative

All details of the OAI are available on the internet (http://www.oai.ucs.edu). In short, individuals were eligible if they had or were at risk of symptomatic TF knee osteoarthritis and were aged between 45 and 79 years. Individuals with inflammatory arthritis, bilateral end-stage knee osteoarthritis, inability to walk and a contraindication for magnetic resonance imaging were excluded. Recruitment of 4796 individuals was realised from March 2004 to May 2006. At baseline the cohort was divided into two subcohorts, one with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (defined as in at least one knee frequent knee symptoms and radiographic TF knee osteoarthritis, defined as K&L ≥2; progression cohort) and a second cohort of 3285 individuals without symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, selected on the basis of having specific characteristics that give them an increased risk of developing symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (incidence cohort). For the incidence cohort age-specific eligibility criteria were defined. Individuals aged 45–49 years were eligible when they had frequent knee symptoms, or made frequent use of medication for the treatment of knee symptoms or had infrequent knee symptoms, and in addition had one or more other eligible risk factor such as knee injury, knee surgery, overweight, positive family history, etc. Individuals aged 50–69 years were eligible if they had frequent knee symptoms, or made frequent use of medication for the treatment of knee symptoms, or were overweight, or had two or more of the eligible risk factors.

At baseline materials for the identification of joint imaging, biomarkers and genetic markers were collected. Also data on the clinical and joint status of subjects and on risk factors for the progression and development of knee osteoarthritis were collected by questionnaires and examination (categorised according to the dimensions of the ICF model depicted in table 1).

In the present report baseline CHECK data of the entire cohort were compared with data of the OAI incidence cohort. To make the cohorts more comparable, in addition, CHECK participants with knee problems (excluding those with exclusively hip problems; n = 829) were compared with participants of the OAI incidence cohort within the same age range (45–65 years), who had at least frequent or infrequent knee symptoms excluding those who eg, just had overweight without symptoms and excluding those who had had previous knee surgery (n = 1578).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of both cohorts are presented using descriptive statistics: median and 25th–75th percentiles or percentages. Differences between groups are analysed using Mann–Whitney U tests or the χ2 test, when appropriate.

RESULTS

More than 75% of participants were selected based on advertisements including the website. The baseline characteristics of the participants from CHECK and the relevant populations of the OAI are presented in table 2. With respect to radiological osteoarthritis (K&L score) and health status there were some striking differences between the cohorts.

Table 2.

Demographic and disease characteristics in CHECK and selections of the OAI

| CHECK | OAI incidence cohort | p Value | CHECK knee subgroup | OAI incidence subgroup | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1002 | 3285 | NA | 829 | 1578 | NA | ||

| Age in years | 56 (52–60) | 61 (53–69) | <0.001 | 56 (52–60) | 56 (51–61) | 0.8 | ||

| Gender, female | 79% | 59% | <0.001 | 80% | 64% | <0.001 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26 (23–28) | 28 (25–31) | <0.001 | 26 (24–28) | 28 (25–32) | <0.001 | ||

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Primary school | 3% | 3% |

|

3% | 2% |

|

||

| Secondary school | 70% | 65% | 0.1 | 71% | 65% | 0.006 | ||

| High professional education/university | 27% | 32% | 26% | 33% | ||||

| Site of pain | ||||||||

| Knee only | 41% | 37% |

|

50% | 43% |

|

||

| Hip only | 17% | 7% | <0.001 | NA | NA | 0.002 | ||

| Knee and hip | 42% | 48% | 50% | 57% | ||||

| No hip or knee pain | NA | 37% | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Pain intensity (range 0–10) | 3 (3–5) | 2 (0–3) | <0.001 | 3 (2–5) | 2 (0–4) | <0.001 | ||

| K&L rating score for knee | ||||||||

| Grade 0 | 68% | 14% |

|

65% | 19% |

|

||

| Grade 1 | 25% | 46% | 27% | 50% | ||||

| Grade 2 | 6% | 16% | <0.001 | 7% | 16% | <0.001 | ||

| Grade 3 | 1% | 19% | 1% | 13% | ||||

| Grade 4 | NA | 5% | NA | 2% | ||||

| K&L rating score for hip | ||||||||

| Grade 0 | 79% | NA | NA | 83% | NA | NA | ||

| Grade 1 | 15% | NA | NA | 13% | NA | NA | ||

| Grade 2 | 5% | NA | NA | 4% | NA | NA | ||

| Grade 3 | 1% | NA | NA | 0% | NA | NA | ||

| WOMAC subscales | ||||||||

| Pain (range 0–20) | 5 (2–7) | 1 (0–3) | <0.001 | 5 (2–7) | 1 (0–3) | <0.001 | ||

| Stiffness (range 0–8) | 3 (2–4) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 | 3 (2–4) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 | ||

| Physical function (range 0–68) | 14 (7–24) | 2 (0–8) | <0.001 | 14 (7–24) | 3 (0–9) | <0.001 | ||

| Present employment | ||||||||

| Paid job/volunteer | 53% | 70% |

|

<0.001 | 52% | 79% |

|

<0.001 |

| No paid job | 47% | 30% | 48% | 21% | ||||

| SF-36 subscales (range 0–100): | ||||||||

| Physical function | 80 (65–90) | NA | NA | 75 (65–85) | NA | NA | ||

| Physical role | 100 (50–100) | NA | NA | 100 (38–100) | NA | NA | ||

| Bodily pain | 67 (57–80) | NA | NA | 67 (57–80) | NA | NA | ||

| Fatigue | 65 (55–75) | NA | NA | 65 (55–75) | NA | NA | ||

| Social function | 88 (63–100) | NA | NA | 88 (63–100) | NA | NA | ||

| Fear and depression | 100 (100–100) | NA | NA | 100 (100–100) | NA | NA | ||

| Mental health | 80 (68–88) | NA | NA | 80 (68–88) | NA | NA | ||

| PCS | 47 (40–51) | 53 (46–56) | <0.001 | 47 (40–51) | 53 (46–56) | <0.001 | ||

| MCS | 55 (50–59) | 55 (50–58) | 0.4 | 55 (50–59) | 55 (49–58) | 0.3 | ||

| EuroQol utility | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) | NA | NA | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) | NA | NA | ||

Median values with 25th–75th percentiles between brackets and categorical variables as percentages (%) are given.

BMI, body mass index; K&L, Kellgren and Lawrence grade; MCS, mental component scale (in Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee; CHECK both scales calculated without general health scale); NA, not available/applicable; braces indicates statistical differences between the distribution of a parameters between both cohorts; OAI, Osteoarthritis Initiative; PCS, physical component scale; SF-36, Short Form 36-item health status survey questionnaire with higher score indicating a better health-related quality of life; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index with higher scores indicating worst health.

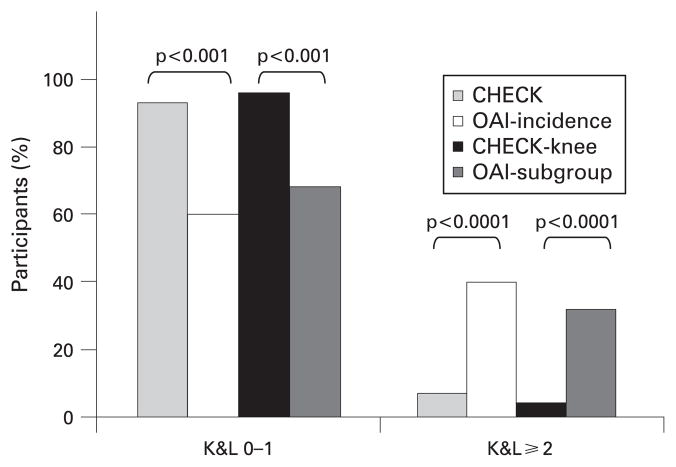

Radiographic joint damage was clearly more notable in the OAI compared with CHECK (table 2). In fig 1 the percentage of participants with a knee K&L grade 0–1 and ≥2 is depicted. Based on the definition of K&L grade ≥2, at baseline only 7% of CHECK participants had radiographic knee osteoarthritis compared with 40% in the OAI incidence cohort (p<0.001). Evidence for radiographic hip osteoarthritis was only present in 7% of the participants of CHECK. The significant difference in knee K&L grade was also clear when the subgroups of both cohorts were compared (8% and 32%; p<0.001). Even when the participants with K&L grade 4 were omitted from the calculations, the difference in severity of radiographic joint damage between both cohorts remains evidently significant. This difference in severity of joint damage between both cohorts was not based on differences in gender (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Comparison of radiographic joint damage between Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee (CHECK) and Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) and their subpopulations at baseline. The bars depict the percentage of knees with a Kellgren and Lawrence (K&L) score of 0–1 and a K&L score ≥2. p Values for statistical comparison are given.

Despite the limited number of participants with radiographic knee osteoarthritis in CHECK, 76% of the patients with knee symptoms could be diagnosed as osteoarthritis according to the clinical American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of osteoarthritis.1,2 Only a minority of CHECK participants with hip symptoms (24%) fulfilled the clinical classification criteria of hip osteoarthritis.

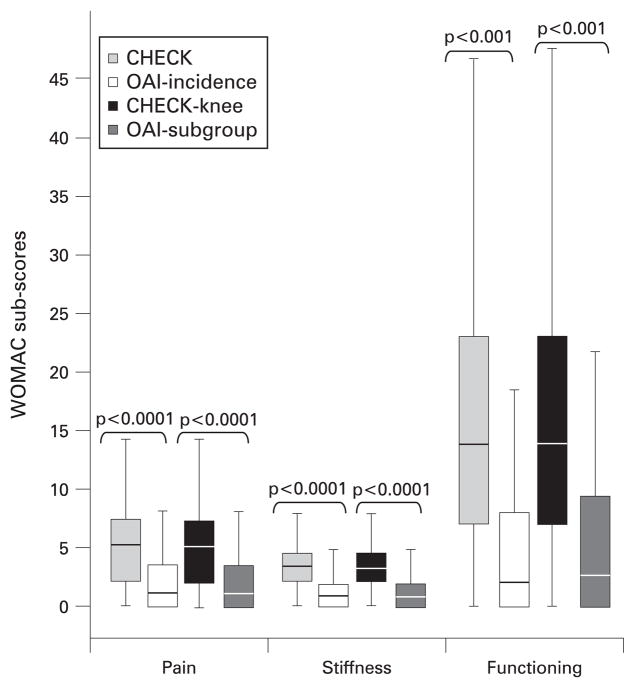

The evident difference in radiographic joint damage between both cohorts was not accompanied by a similar difference in pain and physical function. On the contrary, as shown in fig 2, on each of the WOMAC subscales participants of CHECK presented with more pain, stiffness and problems in function than patients in the OAI. This was observed for the whole cohorts as well as the subgroups of both cohorts (all p<0.001). Women reported more pain and functional disability than men, which was almost identical with the OAI (all p<0.05; data not shown)

Figure 2.

Comparison of the three Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) subscales for pain, stiffness and functional disability between Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee (CHECK) and Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) and their subpopulations at baseline. Box whisker plot (median and 25th–75th percentiles) and p values are given. A higher score indicates more pain, stiffness and problems in physical functioning.

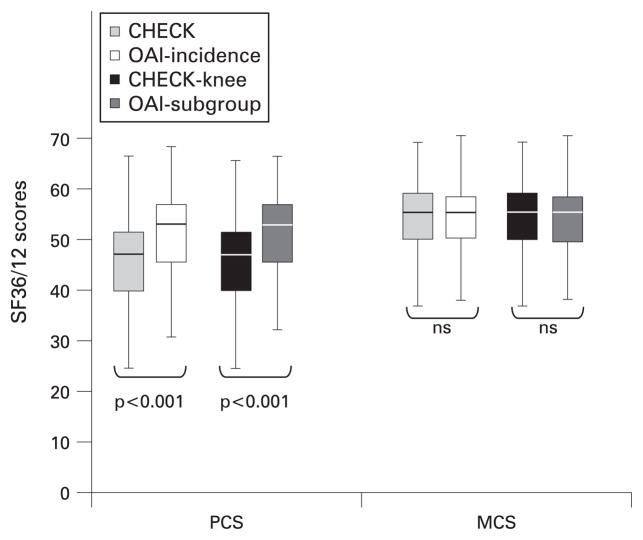

The specific difference in physical function, contrasting the radiographic difference between both cohorts, was underscored by the difference in PCS in contrast to MCS of the SF-36/12 scale (fig 3); CHECK participants scoring less than patients from the OAI (p>0.001) for the PCS but not for the MCS (not significant). Also for these scales, in both cohorts women scored worse compared with men (all p<0.05; data not shown).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the physical component summary (PCS) scale and mental component summary (MCS) scale of the Short Form 36-item health status survey questionnaire (SF-36/12) between Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee (CHECK) and Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) and their subpopulations at baseline. Box whisker plot (median and 25th–75th percentiles) and p values are given. A higher score indicates a better health-related quality of life.

DISCUSSION

The CHECK study is the first prospective 10-year follow-up study of osteoarthritis in an early phase of the disease that combines biological, psychological and social aspects of osteoarthritis. Radiographic knee osteoarthritis was present only in a small number of the CHECK participants when compared with the OAI. In contrast, the participants in CHECK had more pain, more stiffness, more limitations in activities and a worse health status. The worse clinical health status is supported by the use of pain medication: At baseline, only 9% of the participants in OAI had taken any pain medication, whereas this was 46% for CHECK (data not shown). Other characteristics such as body mass index or gender appeared not to be explanatory for this observed characteristic difference between both cohorts (data not shown). It could be that the difference in radiographic joint damage between both cohorts is due to differences in implementation of the K&L grading method. However, grading of a random sample of the OAI knee radiographs by those who performed the grading for CHECK excluded this possibility (data not shown). Although not expected to be explanatory, it should be kept in mind that radiographs were taken, although according to standard protocols, in 10 different centres, whereas in the OAI only four centres are involved. It can not be ruled out that the social, cultural and healthcare system differences between the USA and Europe, in particular The Netherlands, account for (part of) the difference in reported health status. Also differences in inclusion between both cohorts can not be ruled out.

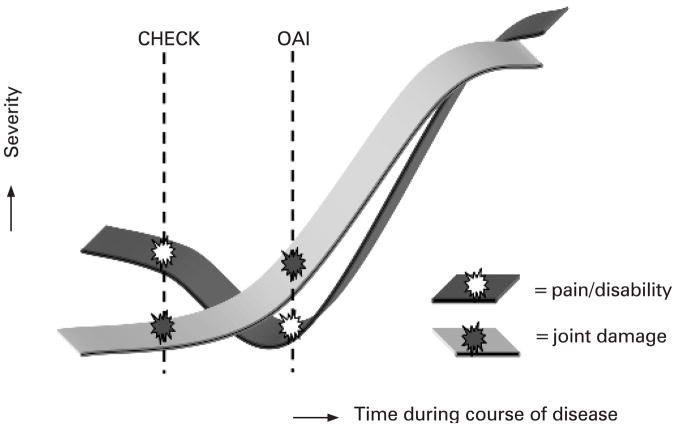

The OAI incidence cohort is recognised as an early osteoarthritis cohort. Taking the radiological findings into account, we conclude that CHECK was started in an even earlier phase of the disease compared with the OAI. Although this is apparently in discordance with the more severe clinical symptoms, the relation between radiographic damage and clinical symptoms has never been clear27 and is the subject of study in both cohorts. Therefore, it is hypothesised that in the early phase of osteoarthritis pain, stiffness and disability (of still unknown origin) are prominent and not yet accompanied by radiographic findings of osteoarthritis (CHECK). In the subsequent phase (OAI) patients are coping with the pain and physical disability, leading to a decrease in the report of these characteristics, while independently (or maybe as a consequence) structural changes, visible on radiographs, develop. In other words, earlier recruitment of patients may carry more perceived symptoms of osteoarthritis (as also seen in rheumatoid arthritis), while in a later stage coping with a new disease may ameliorate the symptoms (fig 4). In the final course of the disease the structural (radiographic) changes progress and lead to further pain and disability. It should be taken into account that, in addition, several other factors, as described in the ICF model, may add to the apparent discrepancy observed between pain and structural joint damage over time.28 Our hypothesis can be tested in the future follow-up of patients in both cohorts, in particular those with the more severe complaints (still) without radiographic joint damage. If it appears that the CHECK population with respect to pain and joint damage, independent of factors such as social background, healthcare system differences, cultural difference, variance in methodology etc, follows the OAI population, then our hypothesis may hold true. Of course other factors, independent of symptoms and joint damage, need to be evaluated regarding observed differences between both cohorts, as such giving both cohorts their surplus value.

Figure 4.

Schematic presentation of the hypothesis as put forward in the discussion explaining the (apparent) discrepancy between both cohorts with respect to pain and joint damage. CHECK, Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee; OAI, Osteoarthritis Initiative.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants of the CHECK cohort and all collaborators of the different sites for their initial and still continuing efforts.

Funding: CHECK is funded by the Dutch Arthritis Association on the lead of a steering committee comprising 16 members with expertise in different fields of osteoarthritis chaired by JWJB and coordinated by JW. Involved are: Academic Hospital Maastricht; Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam; Jan van Breemen Institute/VU Medical Center Amsterdam; Kennemer Gasthuis Haarlem; Martini Hospital Groningen/Allied Health Care Center for Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Groningen; Medical Spectrum Twente Enschede/Twenteborg Hospital Almelo; St Maartenskliniek Nijmegen; Leiden University Medical Center; University Medical Center Utrecht and Wilhelmina Hospital Assen.

The OAI is a public–private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and conducted by the OAI study investigators. This paper was prepared using an OAI public use dataset and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the medical ethics committees of all participating centres.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:505–14. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dijk GM, Dekker J, Veenhof C, Van den Ende CH. Course of functional status and pain in osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:779–85. doi: 10.1002/art.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Hochberg MC. Determinants of pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: effect of demographic and psychosocial variables using 3 pain measures. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1785–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cieza A, Stucki G. New approaches to understanding the impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:141–54. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckland-Wright C. Protocols for precise radio-anatomical positioning of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral compartments of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;3(Suppl A):71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckland-Wright JC, Macfarlane DG, Williams SA, Ward RJ. Accuracy and precision of joint space width measurements in standard and macroradiographs of osteoarthritic knees. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:872–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.11.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckland-Wright JC, Wolfe F, Ward RJ, Flowers N, Hayne C. Substantial superiority of semiflexed (MTP) views in knee osteoarthritis: a comparative radiographic study, without fluoroscopy, of standing extended, semiflexed (MTP), and schuss views. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2664–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaisson CE, Gale DR, Gale E, Kazis L, Skinner K, Felson DT. Detecting radiographic knee osteoarthritis: what combination of views is optimal? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1218–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.11.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurin CA, Dussault R, Levesque HP. The tangential x-ray investigation of the patellofemoral joint: x-ray technique, diagnostic criteria and their interpretation. Clin Orthop. 1979;144:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auleley GR, Duche A, Drape JL, Dougados M, Ravaud P. Measurement of joint space width in hip osteoarthritis: influence of joint positioning and radiographic procedure. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:414–19. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.4.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrozier T, Bochu M, Gratacos J, Piperno M, Mathieu P, Vignon E. Evaluation of the ‘Lequesne’s false profile’ of the hip in patients with hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:295–300. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lequesne MG, Laredo JD. The faux profil (oblique view) of the hip in the standing position. Contribution to the evaluation of osteoarthritis of the adult hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:676–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.11.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veenhof C, Bijlsma JW, Van den Ende CH, van Dijk GM, Pisters MF, Dekker J. Psychometric evaluation of osteoarthritis questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:480–92. doi: 10.1002/art.22001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellamy N, Kirwan J, Boers M, Brooks P, Strand V, Tugwell P, et al. Recommendations for a core set of outcome measures for future phase III clinical trials in knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis. Consensus development at OMERACT III. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:799–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boers M, Brooks P, Strand CV, Tugwell P. The OMERACT filter for Outcome Measures in Rheumatology. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:198–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roorda LD, Jones CA, Waltz M, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM, van der Eijken JW, et al. Satisfactory cross cultural equivalence of the Dutch WOMAC in patients with hip osteoarthritis waiting for arthroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:36–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.2002.001784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verstappen SM, Boonen A, Verkleij H, Bijlsma JW, Buskens E, Jacobs JW. Productivity costs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the influence of methods and sources to value loss of productivity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1754–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picavet HS, van Gils HWV, Schouten JSAG. RIVM rapportnummer 266807002. Bilthoven: CBS/RIVM; 2000. Musculoskeletal complaints in the Dutch population, prevalences, consequences and risk groups (in Dutch: Klachten van het bewegingsapparaat in de Nederlandse bevolking, prevalenties, consequenties en risicogroepen) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraaimaat FW, Evers AW. Pain-coping strategies in chronic pain patients: psychometric characteristics of the pain-coping inventory (PCI) Int J Behav Med. 2003;10:343–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1004_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fink P, Jensen J, Borgquist L, Brevik JI, Dalgard OS, Sandager I, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in primary public health care: a Nordic multicentre investigation. Part I: Method and prevalence of psychiatric morbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;92:409–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hildebrandt VH, Douwes M. Physical load and work: questionnaire on musculoskeletal load and health complaint (in Dutch: lichamelijke belasting en arbeid: vragenlijst bewegingsapparaat) Den Haag: Directoraat-Generaal van de Arbeid; 1991. pp. S122–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannan MT, Felson DT, Pincus T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1513–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, Hirsch R, Helmick CG, Jordan JM, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: The disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:635–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]