Several researchers have pointed out that the production and rearing of children produces externalities—that is, costs and benefits passed on to society at large. Dasgputa (2000) discusses several negative externalities to childbearing that appear to help sustain high fertility levels in poor countries. On the other hand, in a developed economy such as the United States, which has relatively low fertility, substantial expenditures on public goods, and a pay-as-you-go retirement income program, available estimates indicate sizable positive externalities to childbearing. Lee and Miller (1990), for example, reported that the externality to childbearing in the United States was about $105,000 in 1985 dollars. The models used to develop such estimates treat the population as homogeneous with respect to age-specific fertility. Yet a substantial proportion of women in the US remain childless, while many fathers are completely uninvolved with their children. In view of the likely differences between parents and individuals who remain childless, with respect to both the support of and the consumption of public expenditures, it is likely that the externality associated with a first birth is quite different from that associated with a second or higher-order birth. The purpose of this study is to determine the net fiscal impact of the transition to parenthood. The dollar amounts and institutional details described refer to the United States. However, we believe that the arguments apply broadly among low-fertility countries.

Couples are assumed to choose to bear and rear children because they anticipate receiving happiness and satisfaction (i.e., utility) from them that exceeds the substantial private costs they incur. Thus these private costs are internalized: they are taken into account by the couples when they decide to have children or decide not to have children, and therefore should not be part of the calculation of externalities to childbearing. However, children also incur public costs, since the public sector provides public education to all and health care, welfare payments, and other transfers to some. But children also become adults, get jobs, pay taxes, receive continuing benefits, have children themselves, retire, receive Social Security, Medicare, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Medicaid, and their children and all descendants presumably move through a similar life cycle of interactions with the public sector. Because this ongoing stream of taxes paid and benefits received from the public sector is not taken into account by the parents, it is a fiscal externality. This externality could, in principle, be either positive or negative: Lee and Miller (1990) found that in developing countries it was typically negative, while in rich industrial countries it was positive.

In addition to these net transfers, each additional child shares the tax cost of providing public goods, but imposes no additional costs through its consumption of public goods, which by definition are zero. In this way, public goods lead to positive externalities to childbearing. Incremental individuals also share the burden of the federal debt, another positive externality. However, they also dilute the value of any natural resources or other wealth owned by the general public, a negative externality. Perhaps the largest negative externality imposed by a birth is the damage to the environment, if use of the environment is mismanaged by public policy or by dilution of the per capita value of an optimally managed environmental resource, or both. There are, of course, many other ways in which an incremental person affects others. The wages of other workers may be reduced, and consequently the profits earned by owners of capital may be raised, for example. These would be pecuniary externalities, which are not true or technical externalities.

Most attempts to quantify the external costs or benefits of childbearing have focused on the readily quantifiable flows of taxes paid to, and benefits paid by, governments. The most recent estimates indicate that the social benefits of childbearing are quite large in the United States. The National Academy of Science’s study The New Americans (Smith and Edmonston 1997) investigated the fiscal impacts of population change associated with immigration. The framework used to obtain those estimates also generates estimates of the fiscal externalities of a native newborn child. The calculations, which also take into account the expected fiscal impacts of the newborn child’s descendants and the educational attainment of the child’s parents, are striking, ranging from a net present value (NPV) of $92,000 (in 1996 dollars) for the child of a native-born parent with less than a high school education to an NPV of $245,000 for the child of a parent with greater than high school education. Much of the present value of adding a newborn child is attributable to the child’s descendants. This is important because childless individuals by definition have no descendants, and therefore the potential social value of those descendants remains unrealized.

Although overall fertility has remained fairly constant in the US since the early 1980s, the prevalence of biological childlessness among women who have reached the upper limit of childbearing age has risen since 1975, and by 2008 it was nearly 18 percent (Dye 2010). As Folbre (2008) notes, “[c]hildren symbolically repay their parents by spending money and time on children of their own. The terms of this repayment are modified when the next generation has fewer children…” (p. 17). It is widely acknowledged that the private costs of raising children are high, and some observers have suggested a connection between those high costs and rising childlessness (e.g., Crittenden 2001; England and Folbre 1999a). Yet the findings cited above suggest that these private costs are accompanied by substantial public benefits to childbearing. Societal well-being may be improved through interventions that align private and public costs and benefits. If childbearing produces positive externalities, then policies that subsidize childbearing—such as tax reductions, child allowances, or subsidized child care—may be warranted. Some such policies already exist, of course, although many commentators argue for further reductions in the cost of childbearing (England and Folbre 1999b). There is also evidence that childless couples and individuals may lead a backlash against “family friendly” policies in both the public and corporate sector (Casper, Weltman, and Kwesiga 2007; Ryan and Kossek 2008). Thus our estimates have the potential to contribute to public discourse regarding family policy.

There are many reasons to anticipate differences in life-cycle patterns of tax and benefit streams between parents and nonparents, although in some cases the anticipated direction of differences is ambiguous. For example, public assistance payments and school-based nutrition programs are targeted primarily at children, and the benefits from these programs accrue mainly to parents and their offspring. The childless pay property taxes to support public schools, but have no children to consume that education; they may, however, enjoy private benefits in the form of increased housing values (Hilber and Mayer 2004). On the other hand, families with children may consume more housing and therefore pay more in property taxes than the childless. And, while poor families with children consume a large share of public assistance and related benefits, the average of lifetime earned income (and therefore of income and payroll tax payments) may be higher among parents than among the childless.

Research on childlessness often alludes to reduced prospects for old-age support (Rowland 2007) or fears of social isolation, with adverse mental health problems as additional reasons for concern (Zhang and Hayward 2001). Indeed, informal care, provided mainly by family members, is widely acknowledged to represent a large proportion of long-term care and support in the US (Wolff and Kasper 2006). Most disabled elderly are not institutionalized, and within that group most receive care either exclusively from informal providers or from a mixture of formal and informal providers. Unmarried individuals without living children are more likely than those with children to be in nursing homes (Aykan 2003), while childless elderly have significantly higher levels of publicly funded nursing home costs (through Medicare and Medicaid combined) than do parents (Wolf 1999). Other research has shown that having children both delays entry into, and hastens exit from, nursing homes (Garber and MaCurdy 1990; Freedman 1993; Gaugler et al. 2007). With respect to home care, which accounts for a small proportion of public long-term care expenditures, available evidence is less clear.

A broad definition of “parent”

Demographic assessments of childlessness focus, unsurprisingly, on fertility (Sardon 2003). In a typical aggregate economic-demographic model, everyone is identical and everyone has average fertility; thus, there is no need to distinguish parents from nonparents. In recent decades, however, patterns of marriage and cohabitation, of childbearing within and outside of marriage, and of parent/child coresidence, have become quite heterogeneous. As a consequence, “fertility” and “parenting” do not perfectly coincide.

Implicit in the rationale for studying the external costs and benefits of children for society is the recognition that parents incur substantial private costs in raising children. These private costs have much to do with time and money investments in children, regardless of the biological relationships between adult and child. Thus, because we want to allocate economic flows according to parental status, we must go beyond the biological dimension of parenting, recognizing its social and economic dimensions as well.

A large body of research documents the complexities of contemporary family structure in the United States (e.g., Bumpass and Lu 2000; Blau and van der Klaauw 2008). Unmarried cohabiting couples coresiding with children of one or the other or both members, as well as lone-parent households, are a prominent feature of this complex picture of the family (Carlson and Furstenberg 2003). Despite this heterogeneity, mother/child coresidence is nearly universal (Heuveline, Timberlake, and Furstenberg 2003); thus for women fertility and parenting are nearly synonymous. However, many fathers are economically or socially disengaged from their children. For example, Mott (1990) found that about 18 percent of children experience no coresidence with their father during the first four years of life. Some of the absent fathers, to be sure, are living with minor children (their own or those of a new partner) in another household. Yet Garfinkel, McLanahan, and Hanson (1998) found that less than one third of nonresident fathers are living with a new partner and children at a point in time; over the nonresident father’s lifetime, the percentage who spend at least part of the time in a household with children is probably much higher than one third.

Recognizing these complexities, we base our analysis on a definition that identifies parenting with incurring substantial private costs of raising children. We define parents as people who devote uncompensated time or monetary resources to, or coreside with, biological, adoptive, or stepchildren aged 0 through 17. Thus, while all taxpayers provide some support to children through public welfare payments and the financing of education, someone whose only support to children is in the form of income or property taxes would not be classified as a parent because those tax dollars are not directed at their own (biological, adoptive, or step) children. Similarly, someone whose only investment in children took the form of paid provision of childcare would not be considered a parent because his or her efforts are compensated. Under our definition a “deadbeat dad” who has no contact with his children and pays no child support is, despite his biological role in producing children, not considered a parent. And the stepparent whose spouse’s children are coresident while minors, and who therefore are de facto beneficiaries of the stepparent’s time and monetary contributions to the household, however modest, is classified as a parent. Under our definition of parenting, distinctions between biological, adoptive, and stepchildren are irrelevant, regardless of any emotional, affective, or other psychological distinctions across those categories. The upper limit we place on the ages during which parenting can occur is arbitrary, and we realize that most parents continue to support their children well into adulthood and often by bequests when they die.

Our definition of parents takes into account directed expenditures of resources in three domains—time, money, and coresidential space—that are widely acknowledged to constitute the available “currencies” for intergenerational resource flows (Soldo and Hill 1993). A problem with our approach is that whereas a nonparent occupies a polar location on a continuum, parents can be found throughout the rest of that continuum. For example, an absent father who makes just a few child support payments and has no other contact with his child is only in a minimal sense an economic parent. In principle one might impose an arbitrary criterion by which someone would be awarded “full” parental status (e.g., by maintaining coresidence with and/or making time investments and/or contributing financially to a child in each year from birth through age 17) and then coding each potential parent according to the degree to which he or she attained that standard; such an approach, however, seems infeasible given available data.

Scope of analysis

Ours is a descriptive analysis of the relative life-cycle patterns of taxes paid and benefits received by parents and nonparents. Some of the differences are causal, for example those arising mechanically from the public costs of educating children or more subtly from variations in labor market activity and consumption patterns over the life cycle. Others reflect selectivity with respect to the characteristics of individuals who become parents, for example by education, wealth, race/ethnicity, or region of residence. Our calculations of the fiscal net present value for parents versus nonparents do not employ a behavioral model of fertility or parenting choices in the face of incentives created by tax and transfer programs. Nevertheless, our descriptive accounting model is a useful companion to any attempt to model the behavioral consequences of these fiscal flows.

Earlier research has found that the dependent’s exemption provisions of income taxation have a pronatalist effect (Whittington, Alm, and Peters 1990; Whittington 1992). Moffitt’s (1992) review, however, found only mixed evidence of the pronatalist effects of public assistance. Some research has shown a pronatalist effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit (Baughman and Dickert-Conlin 2003). Public interventions other than direct taxation or benefit transfers might also contribute to parenting decisions and, consequently, have fiscal impacts. For example, Schmidt (2007) found that state-level mandates for private health insurance coverage of infertility treatments significantly increase first-birth rates. These results imply that there may be several “margins” (i.e., budget constraint segments) along which tax and transfer policies potentially influence fertility outcomes. Yet even an ambitious model that included all of these possibilities would be inadequate for our purposes. It would also be necessary to model the decisions to marry or cohabit, and to provide support to a nonresident child. The specification and estimation of such a model lies well outside the scope of our analysis.

A related point is our inability to distinguish childlessness that results from infertility problems from that which is purposively chosen. Little is known about levels or trends in involuntary childlessness. While the volume of infertility treatment has risen during the 1980s and early 1990s, a majority of women who reported using infertility services in 1995 had previously given birth to one or more children (Stephen and Chandra 2000). Furthermore, infertility does not rule out becoming a parent, as we define it, because the transition to parenthood can occur formally through adoption or marriage (and the consequent acquisition of stepchildren) or informally through cohabitation. Data from the 2000 Census indicate that 48 percent of households that contain any adopted children contain only adopted children, while 47 percent of households that contain any stepchildren contain only stepchildren (derived from data found in Krieder 2003, Table 8; a tiny percentage of households contain both adopted and stepchildren but no biological children). These results imply that a substantial proportion of parents who would otherwise remain childless acquire their children in ways other than through biological reproduction. The extent to which these behaviors resolve situations of biological infertility cannot be determined with available data.

We also ignore the consumption-related environmental impacts of child-bearing. This class of externalities is very difficult to measure and is rarely included in empirical analyses. In the long run an additional child will itself bear additional children and contribute a sustained increase in population size, with consequent environmental effects. Nevertheless, the net environmental impact of growing childlessness is less clear cut. Furthermore, the distribution of fertility can change while holding constant the overall level of fertility and therefore holding constant the overall level of environmental externalities.

Analytic model

Lee and colleagues have developed a comprehensive economic-demographic accounting framework for studying the fiscal impact of population change (Lee and Miller 1990,Lee and Miller 1997; Lee and Edwards 2002a, 2002b). Its essential elements are as follows: (1) use individual- and household-level data to estimate a series of age profiles of taxes paid to, and benefits received from, federal and state/local programs; (2) obtain an initial count by age for each population group; (3) specify assumptions about the future demography (fertility, mortality, and immigration) and economy (productivity growth rates, real interest rates, and any difference between the rate of growth of health costs and productivity growth); (4) specify algorithms for adjusting taxes and programmatic expenditures in each future year, reflecting assumptions about the bounds of allowable public debt relative to GDP; and (5) produce an economic-demographic forecast, period by period, with individuals added to and removed from the population according to the demographic assumptions. The fiscal flows (element 1 above) are averages for men and women combined, so the net present values are computed using a one-sex accounting model.

In the forecast, individuals move, year by year, along their predetermined age profiles of earned income, adjusted to reflect productivity change, and along their age profiles of consumption of publicly funded program benefits, also adjusted to reflect productivity growth and the specified trajectory of health care costs. In the model, population change and productivity growth lead to GDP change (by assuming that aggregate labor income is a fixed share of GDP), which, in turn, changes the demands for various public expenditures. Imbalances between demographically driven changes in public expenditures and GDP-driven changes in tax revenues induce adjustments to taxes in accordance with the assumed limit on the debt-to-GDP ratio. Thus, in any given future year the effective profile of earnings, taxes paid, and benefits received across age groups is endogenously determined in the forecast. The model’s output includes separate accounts for individuals in the baseline or starting population and those in the offspring or descendants’ population (for additional details see Smith and Edmonston 1997, especially pp. 323–327).

In the NAS study of the fiscal impacts of immigration, separate profiles were estimated by three levels of education, and separately for foreign-born, second-generation (native-born of foreign-born parents), and third-generation (native-born of native-born parents) individuals. The accounting model used in these calculations can also deal with other ways of disaggregating the population into constituent groups and can produce estimates of cohort-specific age profiles of fiscal flows for the total population, in which everyone is average.

The starting point for our calculations is the population-average dynamic profiles used in the estimates presented in Smith and Edmonston (1997). Our NPVs use an array of per capita flows of funds for each combination of age, a (up to a maximum beyond which survivorship is negligible); year, t; and fiscal flow, f. We partition each element of the array into two components, one for parents and one for nonparents, using a decomposition approach that is spelled out in the Appendix. We use external information on the nonparent-to-parent ratio within each fiscal flow (ka,t,f) and on the proportion of parents within a cohort ( ) to perform the decomposition. Details on the data sources and methods used to derive these quantities are also presented in the Appendix. The model can handle arbitrarily many generations of offspring, but in practice the end of the forecast period is reached when the discount rate reduces the present value of a dollar in some future year to a negligible amount, which inevitably occurs as long as the real discount rate exceeds the productivity growth rate plus the population growth rate.

Model inputs

Our analysis includes 49 tax and benefit flows (a list of these flows appears in the Appendix). Each flow accrues either to the federal balance sheet or to the state and local balance sheet (aggregated across all states and localities), or to both. All are associated either with taxes paid or with benefits received directly by individuals or households. Pure public goods such as national defense, interest on the national debt, and spending on research and development are not included among benefits consumed because they benefit society as a whole.

Differences in NPVs between parents and nonparents depend partly on the age profile of each fiscal flow and partly on the prevalence of nonparents at each age. Fiscal flows that peak early in the life cycle (for example, spending on public schools) contribute relatively more to the NPV calculation than flows that peak late in the life cycle (for example, Medicare benefits), other things being equal. And, holding constant the total of the age-specific flow and the nonparent-to-parent ratio of flows at each age, the greater the proportion of parents, the greater the share of the aggregate fiscal flow allocated to parents. Therefore, we analyze the sensitivity of our results to the proportion of parents.

Some programs—for example, public elementary and secondary schools, school lunch programs, and so on—by design are directed solely at children, hence the costs of those programs are associated exclusively with parents. For such programs, ka,t,f = 0 by definition. In most cases, however, the ratios must be determined empirically. Our estimates of the average levels of fiscal flows to or from parents and nonparents use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID 2006) for the period 1967–2005, and from other sources (for details see the Appendix). We use those age-specific averages to estimate a set of k ratios that are assumed to apply to all future years covered by our NPV calculations. It is not necessary to decompose the fiscal flows associated with offspring generations into their “parent” and “nonparent” components. This is because any fiscal externalities associated with offspring accrue, in their entirety, to individuals identified as parents in the initial population. Thus, our decomposition of fiscal flows is needed only for individuals in the population of potential parents, that is, in the initial population.

Because the proportion of parents in a cohort at each age influences the decomposition of fiscal-flow totals into their nonparent- and parent-specific components, the age profile of the prevalence of parenthood will influence the NPV computations. If parents and nonparents have different death rates at older ages, then the proportion of parents will change as a cohort ages as a result of differential survivorship of the two groups. The few studies that investigated mortality differences by parental status, most of which examined women’s mortality (e.g., Lycett, Dunbar, and Voland 2000; Grundy and Tomassini 2005; Friedlander 1996), have produced mixed findings. Because of the social support that can be provided by children, fathers might be expected to enjoy lower mortality than childless men. For women, the situation is more complex because childbearing is protective for some diseases (Kravdal and Hansen 1993; Vachon et al. 2002; Melton et al. 2001; Talbott et al. 1989), yet higher-parity mothers appear to have adverse mortality outcomes due to “wear and tear” (Doblhammer 2000).

We analyzed differential mortality between parents and nonparents using data from the Health and Retirement Survey1 for individuals age 55 and older. Consistent with our one-sex accounting model, we pooled men and women and estimated a proportional-hazards model of the association between parenthood and mortality, using as the baseline mortality rate an unrestricted single-year step function in age. The results (not shown) indicate that nonparents’ death rates are 9.7 percent higher at each age (through age 99, the oldest age at which our data permitted single-year estimation). This difference is statistically significant (p = 0.037) but small: a change in death rates of this magnitude implies a difference in life expectancy at age 55 of only 8 months (using the NCHS 1999–2001 life table), so we have disregarded it in our analysis.

The “thought experiment”

In our analysis, there are three types of people: (1) children, (2) adult parents, and (3) adult nonparents. We define children as all persons less than 18 years old. We do not distinguish people by sex or race; instead, we depict a composite “average” person of each type. Furthermore, we distinguish between those already alive at the start of the projection period (i.e., the initial population) and those born thereafter (i.e., the offspring population). We distinguish between adult parents and adult nonparents in the starting population, but not in the offspring population. Finally, in our analysis “parent” and “nonparent” are lifetime statuses: upon reaching age 18 individuals are classified as parents or nonparents, even if they do not become parents until many years later. The lifetime perspective accounts for the possibility that choices about educational attainment or the timing and intensity of labor market behavior reflect plans for future childbearing and childrearing.

For our purposes, it is necessary only to decompose the life-course patterns of taxes and benefits for a single birth cohort. In particular, for individuals age 18 at baseline (when t=0), we determine fiscal flows for the sequence of flows for ages a=18 (in year t=0), a=19 (in year t=1), a=20 (in year t=2), and so on, until the population of people initially 18 years old has completely died out. It is also necessary to distinguish the offspring of those persons initially 18 years old from all other members of the offspring population. Having decomposed the array of fiscal flows among the population initially age 18 for all relevant future years, we compute the net present value of each of the fiscal flows individually and then obtain their sum. The difference between the NPV of the fiscal flows of parents and nonparents, that is, NPVP − NPVNP + NPVOFFSPRING, represents the fiscal impacts of replacing an average nonparent with an average parent. This comparison does not hold constant any of the other differences between parents and nonparents, such as differences in family background, health and other endowments, educational attainment, labor market outcomes, and any of the other numerous influences on life-cycle tax payments or benefits received. Thus our estimate cannot be interpreted as the net fiscal impact of the marginal nonparent’s transition to parenthood. As noted before, an exceedingly complex structural model of parenting choices would be required to generate an estimate of the fiscal impact of the marginal individual’s parenting outcomes.

Results

Age patterns of k ratios

Table 1 shows age-specific k ratios for the 17 data series for which we have the requisite individual-level data. Recall that k is the age-specific ratio of average levels of a fiscal flow among nonparents to average levels among parents. Thus a ratio over 1 indicates that nonparents are paying higher taxes (or receiving higher benefits) than parents in that age group. We generally computed k for five-year age groups, except at the youngest (18–24) and oldest (65–74 and 75-plus) ages, but for low-prevalence programs such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) we have used wider age intervals, producing smoother age profiles of nonparent-to-parent ratios.

Table 1.

Age-specific k (nonparent-to-parent) ratios, selected tax and expenditure programs

| Age group

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | 40–44 | 45–49 | 50–54 | 55–59 | 60–64 | 65–74 | 75+ | |

| Federal | |||||||||||

| Taxes | |||||||||||

| Income tax | 1.05 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.29 | 1.12 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 1.67 |

| Excise tax | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 1.19 | 1.19 |

| FICA and SMI | 1.00 | 1.11 | 1.26 | 1.32 | 1.22 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.99 |

| Benefits | |||||||||||

| OASDI | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Medicaid (noninstitutional)a | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| SSIa | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 2.28 | 2.28 | 2.28 | 2.28 | 1.22 | 1.22 |

| EITC | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Food stampsa | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Rent subsidy | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.11 | 2.11 |

| Public housing | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| Unemployment benefitsa | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.32 | 1.32 |

| Public collegea | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 |

| Military retirement | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.57 | 1.57 |

| State and local | |||||||||||

| Taxes | |||||||||||

| Income tax | 1.05 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 1.62 |

| Property tax (owners) | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| Property tax (renters) | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 1.76 | 1.76 | 1.76 | 1.76 | 1.73 | 1.73 |

| Sales tax | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 1.13 |

| Unemployment premiums | 1.12 | 1.15 | 1.18 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.70 | 0.72 |

Applied to both federal and state/local expenditures

EITC = Earned Income Tax Credit

FICA = Federal Insurance Contributions Act

OASDI = Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance

SMI = Support for Mortgage Interest

SSI = Supplemental Security Income

For many programs and in particular for tax payments, the k ratios are closely tied to the relative age profiles of per capita income received by nonparents and parents. These profiles (not shown) indicate that nonparents have higher per capita incomes than parents up to about age 45, which is to be expected inasmuch as these are the ages when mothers are more likely to have reduced labor force activity while caring for young children. On the other hand, between the mid-50s and early 70s, parents have higher per capita incomes than do nonparents. For benefit programs with some targeting of children, such as Food Stamps, Medicaid (for those under 65), and especially the Earned Income Tax Credit, the k ratios are well below one. There are some surprises in Table 1 as well. For example, SSI benefits (for people 45 and older), unemployment benefits, and (again for those 45 and older) housing subsidies go to nonparents at a substantially higher rate than to parents. Veterans’ pensions also favor nonparents, a finding that may indicate that spending one’s career in military service is incompatible with parenting.

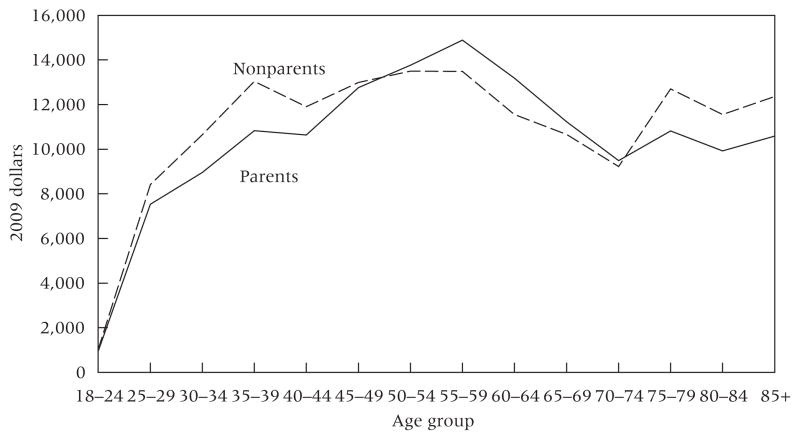

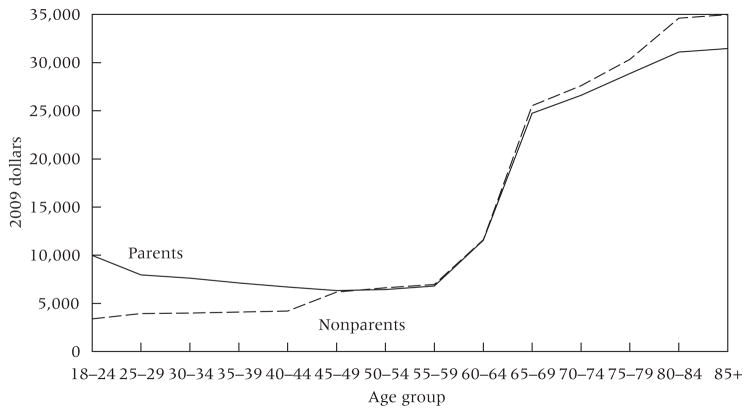

Figures 1 and 2 summarize the age profiles of all taxes paid, and all benefits received, by parents and nonparents. These profiles are obtained by multiplying each program’s baseline age profile by the corresponding set of k ratios (including all programs where k = 0 by assumption, or k = 1 in the absence of evidence to the contrary), then adding across programs. Figure 1 indicates that nonparents pay higher taxes than parents up to age 50, and again at ages 70 and older. Figure 2 shows that parents consume more publicly funded benefits than nonparents up to age 45, but fewer such benefits from age 65 onward. Between ages 45 and 65 the two groups’ per capita consumption of publicly funded benefits is indistinguishable.

FIGURE 1.

Age profile of taxes paid in baseline year, by parent status

FIGURE 2.

Age profile of benefits received in baseline year, by parent status

NPV calculations

There are two components of our NPV calculations: average own-lifetime estimates for parents and nonparents in the initial or starting population; and per-parent estimates for the offspring population. The calculations used a 1994 baseline population and age profiles of taxes and benefits measured in 1994 dollars. All results have been inflated to 2009 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. The baseline results assume that the proportion of parents in the population is 0.87.2

The economic assumptions underlying our estimates were based closely on those used by the Congressional Budget Office in its long-term projections done in 1996 (CBO 1996): a productivity growth rate of 1 percent per year, tax and most benefit rates rising at this rate as well, and various public and quasi-public goods expenditures rising at the rate of GDP growth. For health care costs, CBO closely followed the 1995 report of the Medicare Trustees. The NAS study followed the more recent 1996 report by the Trustees.3 For the return earned on trust funds and for calculating the NPVs, we use a real discount rate of 3 percent (as in the baseline results presented in Smith and Edmonston 1997).4 The debt-to-GDP ratio was capped at the level reached in projections in 2016, and fiscal balance was maintained thereafter, half by cutting benefits and half by raising taxes.

In Table 2, all tax and benefit programs for which we had to assume k = 1 have been grouped together, because they do not contribute to any potential differential between parents and nonparents. The “other taxes” row of the table includes corporate taxes and a host of user and licensing fees, estate and gift taxes, customs levies, and other miscellaneous taxes; together these amount to around 22 percent of all taxes included in the NPV figures. The “other benefits” row includes energy assistance, incarceration costs, public employee and railroad retirement benefits, workmen’s compensation, and congestible goods such as highways; together they represent 35–37 percent of benefits received.

TABLE 2.

NPV at age 18 of lifetime taxes and benefits by program and parent status

| Nonparents | Parents | Offspring | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxes paid | |||

| Federal income tax | $196,000 | $185,000 | $309,000 |

| State income tax | 42,000 | 41,000 | 64,000 |

| Excise tax | 14,000 | 13,000 | 20,000 |

| FICA | 157,000 | 141,000 | 238,000 |

| SMI | 4,000 | 4,000 | 7,000 |

| Property tax (owners) | 24,000 | 26,000 | 39,000 |

| Property tax (renters) | 14,000 | 7,000 | 12,000 |

| Sales taxes | 38,000 | 43,000 | 64,000 |

| UI premiums | 9,000 | 9,000 | 14,000 |

| Other taxesa | 136,000 | 136,000 | 212,000 |

| Total taxes | 634,000 | 605,000 | 979,000 |

| Benefits received | |||

| OASDI | 66,000 | 66,000 | 96,000 |

| Medicare | 49,000 | 49,000 | 70,000 |

| Medicaid (institutional)a | 18,000 | 11,000 | 17,000 |

| Medicaid (noninstitutional)a | 5,000 | 16,000 | 60,000 |

| SSIa | 5,000 | 5,000 | 6,000 |

| EITC | 0 | 3,000 | 3,000 |

| AFDC/TANFa | 0 | 12,000 | 13,000 |

| School lunch | 0 | 0 | 4,000 |

| Food stampsa | 1,000 | 4,000 | 12,000 |

| Rent subsidies | 1,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 |

| Public housing | 2,000 | 2,000 | 4,000 |

| UI benefitsa | 8,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 |

| Public schoolsa | 0 | 10,000 | 143,000 |

| Public higher educationa | 21,000 | 15,000 | 34,000 |

| Student aid | 4,000 | 3,000 | 5,000 |

| Military retirement | 11,000 | 9,000 | 14,000 |

| Other benefitsa | 115,000 | 115,000 | 218,000 |

| Total benefits | 306,000 | 328,000 | 711,000 |

| Taxes minus benefits | 328,000 | 277,000 | 268,000 |

Federal and state/local taxes, or benefits, combined

NOTE: All figures in 2009 dollars, calculated using a 3 percent discount rate.

AFDC = Aid to Families with Dependent Children

EITC = Earned Income Tax Credit

FICA = Federal Insurance Contributions Act

OASDI = Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance

SMI = Support for Mortgage Interest

SSI = Supplemental Security Income

TANF = Temporary Assistance to Needy Families

UI = Unemployment Insurance

The net present value at age 18 of taxes paid by the average parent over his or her remaining lifetime is $605,000, whereas the comparable figure for nonparents is $634,000; nonparents, in other words, pay more than parents in lifetime taxes. However, the NPV of taxes paid (over a 300-year horizon, in these calculations) by the offspring of the parents is nearly $1 million, far more than offsetting the own-lifetime difference between nonparents and parents. The own-lifetime publicly funded benefits consumed by parents also exceed the analogous figure for nonparents, despite the fact that for many of the programs shown, nonparents receive more than parents.

The relevant figures for determining the net externalities associated with parenting depend on the difference between taxes paid and benefits received. Nonparents pay $328,000 more in taxes than they receive, while parents pay $277,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits. The offspring of the parents, in turn, pay over $268,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits. In each case, the excess of tax payments over benefit consumption results partly from the exclusion of pure public goods from the benefit side of the balance sheet: whereas all tax payments represent a reduction in private consumption possibilities, only the “excludable” part of public expenditures belongs in these accounts. By definition, there is no marginal cost for providing an incremental person with the services of a public good, but an incremental person does help to pay the cost of the public good, thereby reducing the taxes that the original population must pay for this purpose.

Thus, the net present value of the fiscal externalities of becoming a parent, calculated from the “taxes minus benefits” row of Table 2, equals $277,000 (parents) minus $328,000 (nonparents) plus $268,000 (offspring), or $217,000 in 2009 dollars. This number represents our central finding: the net fiscal externality of becoming a parent is positive and substantial. An asset with a present value of $217,000 would yield an annual flow of $6,510 in perpetuity at a real rate of 3 percent in 2009 dollars. Alternatively, the same asset is equivalent to a lifetime annuity that pays nearly $8,100 per year, beginning in one’s eighteenth year and continuing to death (computed using the 1999–2001 all races and both sexes life table for the US produced by NCHS).

Sensitivity analysis

Table 3 summarizes the contributions to the net fiscal externalities of parenting obtained for discount rates of 0.01, 0.03 (which duplicates Table 2), and 0.05. With discount rates of less than 3 percent, the fiscal externality of becoming a parent rises sharply, nearing $4 million when r = 0.01. This very large present value is largely due to the exclusion of pure public goods from the consumption side of the life-cycle balance sheet. For higher discount rates, the fiscal externality of parenting falls; the externality falls to zero when r = 0.043. This represents the internal rate of return—the interest rate at which the net present value of taxes paid minus benefits consumed is equalized between parents and nonparents. As long as the real interest rate is lower than this figure, parents are, on balance, net contributors to societal well-being if measured strictly in public expenditure terms.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity of NPV to discount rate

| Discount rate

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| Taxes paid | |||

| Nonparents | $1,168,000 | $634,000 | $376,000 |

| Parents | 1,133,000 | 605,000 | 354,000 |

| Offspring | 13,796,000 | 979,000 | 220,000 |

| Benefits received | |||

| Nonparents | 745,000 | 306,000 | 151,000 |

| Parents | 750,000 | 328,000 | 175,000 |

| Offspring | 9,851,000 | 711,000 | 206,000 |

| Taxes – benefits | |||

| (1) Nonparents | 424,000 | 328,000 | 225,000 |

| (2) Parents | 384,000 | 277,000 | 179,000 |

| (3) Offspring | 3,946,000 | 268,000 | 15,000 |

| Net externality [=(2)−(1)+(3)] | 3,906,000 | 217,000 | −31,000 |

NOTE: All figures in 2009 dollars.

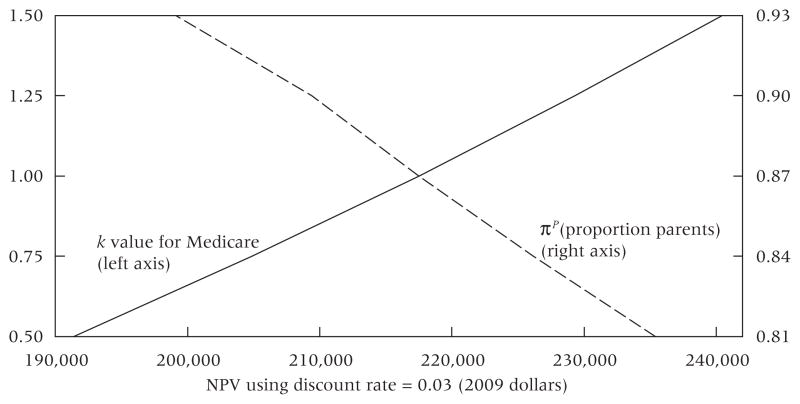

We have conducted two other sensitivity analyses, the results of which are shown in Figure 3. First, we used a range of values for k—the nonparent-to-parent ratio—for the Medicare program, which is the second-largest single benefit program according to Table 2. Available evidence does not support a value for k other than 1, although there are arguments suggesting that it could be either higher or lower (Wolf and Laditka 2006). The solid line in Figure 3 shows that over a broad range of possible values—from k = 0.5 to k = 1.5—the net fiscal externality to parenting (using a 3 percent discount rate) ranges from slightly over $190,000 to about $240,000; in all cases, the net externality remains positive. A similar degree of sensitivity to the value of πP—the proportion of parents in the population—is revealed by the dashed line in Figure 3: the lower the proportion of parents, the greater the net externality per parent.

FIGURE 3.

Sensitivity of NPV to π P and the Medicare k value

Fiscal externalities compared to private spending on children

We have imputed private household spending on children to the parents in our PSID database. For this task, we used average per-child expenditures on children found in the US Department of Agriculture’s report Expenditures on Children by Families, 2008 (Lino and Carlson 2009). The report provides average expenditures from pretax income by income class and child’s age (in three-year groups from 0–2 to 15–17), separately for one- and two-parent families. The report also provides adjustment factors for combining children by age and by number of siblings. We used these averages to construct a synthetic age profile of household spending on children. We divided total spending equally between the two parents in couple-headed households, then averaged the imputed per-parent spending by single year of age of the parent, and finally obtained the NPV at age 18 of all future spending on children. Using r = 0.03, the resulting NPV is $192,000 (in 2009 dollars), well below the per-parent fiscal externality of parenting. This finding is even more remarkable when we consider that household pretax income includes some transfer income, such as TANF and food stamps. If we subtract publicly funded household expenditures on children from the total, the fiscal externality associated with parenting far exceeds the purely private expenditures parents make on behalf of their own children.

Discussion

There are several ways in which our estimate of the net fiscal externality to being a parent—$217,000—could contribute to policy debates. One might argue that becoming a parent is tantamount to providing society with a non-depreciating capital asset that generates an annual flow of revenues, in perpetuity, such that the present value of the asset (at an interest rate of 3 percent) is $217,000. A more qualitative interpretation is that parents receive a small net subsidy over their own lifetimes, while producing offspring whose value to society is many times the size of that subsidy. For discount rates lower than 3 percent the fiscal externality is considerably larger, although for discount rates greater than 4.3 percent it is negative.

We have seen that public-sector transfer programs create a positive externality to childbearing. This externality distorts the incentives guiding individual fertility choices, perhaps leading to a suboptimal level of childbearing. Adjustments in taxes or subsidies could internalize these social spillovers and move fertility closer to its social optimum. However, these adjustments might involve costly subsidies or tax breaks for couples who would have borne the same number of children in any case, and the result could be a net fiscal loss, at least in the short term and possibly in the long term as well. As we have indicated, we lack a structural model of parenting choices that would permit us to investigate such effects. If the goal were to reduce the long-term fiscal imbalances resulting from an aging population, then different policies would be called for.

More generally, one might argue that parents pay too much in taxes or, equivalently, bear too large a share of the total costs of raising children. On the other hand, one might use these results to argue that nonparents should pay a surtax or otherwise increase their contribution to the public budget. Another way to “capture” the fiscal externality is to increase public spending on behalf of children, through education, health, or income-support programs. Another area of policy relevance, outside the realm of taxes and transfers, relates to coverage of reproductive benefits. King and Harrington Meyer (1997) found that poor women tend to have broad access to contraceptive coverage but little access to infertility treatments, while working- and middle-class women enjoyed broader coverage of infertility treatments but scant coverage of contraception.

An acknowledgment of the social value of informal care—including the care provided by children to their parents—is implicit in proposals to link tax reductions to caregiving. To invoke the social value of informal care as a rationale for differential tax treatment according to parental status is to echo past calls to link Social Security benefits to fertility (Demeny 1987; Burggraf 1997). An interesting parallel has arisen in Germany, whose 1994 Dependency Insurance Act launched a universal long-term-care insurance program funded through an earmarked payroll tax. In 2001 Germany’s highest court ruled that it was unconstitutional to tax parents and the childless at the same rate; interestingly, the judge rejected (for lack of evidence) the argument that parents used fewer care resources, basing his decision instead on the fact that parents, through their childbearing, produce the future workers needed to keep the insurance system solvent while the childless do not (Schneider 2002). Our findings imply that parents’ childrearing activities produce a substantial fiscal dividend in the contemporary United States as well.

Our results are, to an unknown extent, specific to both the time period—the late twentieth century—and the policy setting—US tax, transfer, and expenditure programs—used in our analysis. One issue we have not explored is the extent to which the net present values we provide are specific to the single birth cohort—people aged 18 in 1994—for which we have obtained our estimates. For example, the budget-balancing assumptions built into the underlying model, together with the combination of age distribution and programmatic structure represented—in particular, the growth of old-age entitlements in a pay-as-you-go system—result in a combination of tax increases and benefit reductions somewhere in our reference cohort’s middle years. These adjustments are likely to produce NPVs that differ from those of cohorts born earlier, or later, than the cohort featured in our analysis.

Changes over time in underlying demographic and economic variables could also alter our findings. For example, the average age of women’s first childbirth, and therefore the timing of the transition into parenthood, has risen in recent decades (Mathews and Hamilton 2002). As the onset of childbearing shifts to later in the life cycle, the net fiscal benefits attributable to offspring are delayed, reducing their present value at age 18 in the parent’s life. However, those who delay childbearing may have labor market behavior—and, therefore, tax payments—that more closely resemble those of nonparents at young ages, narrowing the own-lifetime differences in net tax payments between parents and nonparents. Because the latter changes occur sooner, they might outweigh the reductions in offspring NPVs associated with delayed childbearing.

Past research suggests that externalities to childbearing are positive in developed countries and negative in developing countries (Lee and Miller 1990). Estimates of the fiscal externalities to becoming a parent in developed countries other than the United States would depend on many factors, including parenting patterns, the level and nature of taxation—for example, the relative importance of income-based taxation, prominent in the US, and consumption-based taxation such as the Value Added Tax, widely used in Europe—and the relative importance of public goods and excludable goods and services in the public budget. However, our finding that much of the NPV of becoming a parent is due to the future net tax contributions from offspring is likely to be true in other developed countries as well.

There are many ways to characterize the interactions among demographic change, tax and transfer programs, and intergenerational flows of economic resources. Our approach emphasizes a within-cohort comparison between two demographic groups, parents and nonparents. Another approach is to consider between-cohort differences. For example, Bommier et al. (2010) investigate the degree to which various generations experience net gains or losses with respect to intergenerational transfer of resources to finance public education, Social Security, and Medicare benefits. They find that the NPV at birth of expected benefits from these three programs is negative for some birth cohorts and positive for others. The two approaches address very different issues; in principle, the net positive externalities to parenting found in our analysis can arise in birth cohorts that experience net gains or net losses through the intergenerational transfer mechanisms analyzed by Bommier et al.

As acknowledged above, we make no attempt to account for environmental externalities associated with becoming a parent. Environmental externalities produced by population change, which can occur as a result of aging and spatial redistribution as well as fertility, might take the form of harmful emissions, nonrenewable resource depletion, or disposal of waste (Pebley 1998). A few studies have tried to compute the monetary costs of these environmental externalities. For example, O’Neill and Wexler (2000) abatement costs imposed by computed the present value, at birth, of the CO2 an incremental childbirth over a 100-year interval. Their base-case estimate is that this environmental externality costs as much as $4,900 (in 1990 dollars, using a 3 percent discount rate). Converting this estimate to 2009 dollars and further discounting to the average age at childbirth, we find that the offspring of someone who ends up with two children impose “greenhouse” external costs on society of about $13,000. While not definitive, this estimate suggests that the fiscal externality to becoming a parent, net of this particular associated environmental cost, is likely to remain positive.

Our analysis employs an abstract depiction of demographic, economic, and public-sector dynamics and depends on a long list of assumptions, and interpretation of the findings must be mindful of those assumptions. It would be desirable to relax many of our assumptions, but to do so would require additional data (some of which do not appear to exist) and a far more complex analytic model. Finally, we have noted elements of spillover from private familial behavior into the public arena, some of which—environmental externalities, for example—are omitted from our analysis. These and many other issues remain as opportunities for additional research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant no. R03-HD048674-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by grant no. R37-AG025247 from the National Institute on Aging. An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America. We have received helpful suggestions and comments from many individuals, including Alan Auerbach, Nancy Folbre, Wendy Sigle-Rushton, and seminar participants at Syracuse University and the University of Pennsylvania. Katie Francis also provided valuable assistance. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of their departments or agencies.

Appendix

Decomposition of fiscal flows

Each fiscal flow Ya,y,f represents the per capita average of funds flowing to or from people of age a, in year t, for flow f, and can be decomposed using the identity

| (1) |

where the proportions (πa,t) and mean fiscal flows on the right-hand side of the equation pertain to nonparents (N) and parents (P) respectively. We treat each nonparent-specific flow as a fixed multiple of the respective parent-specific flow, ka,t,f so we can rewrite (1) as

| (2) |

eliminating from the equation. Given values of ka,t,f and , determined out-side the model, we can solve (2) for the unknown value of and then calculate Our problem becomes one of finding suitable values for the πs and the ks.

Derivation of k ratios

Data

Our analysis relies mainly on data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a large, ongoing panel study of family and economic dynamics that began in 1968 (Hill 1992). Annual interviews with family heads (and occasionally with their spouses) conducted from 1968 to 1997, followed by biennial interviews in 1999, 2001, 2003, and 2005, are used in this study. We used the PSID data to determine age-specific averages of several tax and benefit amounts, separately for parents and nonparents. This, in turn, requires that we categorize PSID sample individuals as parents or nonparents. Our use of a lifetime definition of parent status places restrictions on our use of the data. In particular, PSID respondents were first asked about their childbearing and adoption history in the 1985 interview and in each subsequent interview. We assume that a transition to parenthood cannot take place after age 45. This accords with the Census Bureau’s practice of reporting parity distributions by age up to a maximum of age 44 (i.e., women aged 40–44; see, e.g., Dye 2010). The implication of this assumption is that to be included in the analysis, PSID respondents must reach age 45, and report on their childbearing history, at or after the 1985 interview.

In the first interview year (1968) we include all family heads or spouses age 18 or older. Someone age 18 in 1968 was born in 1950. The last year of birth included in the sample is 1960; people born that year were 18 in 1978. We restrict our sample of person-years to years in which the individual was at least 18 and either the family head or the spouse of family head, because more of the key economic information is provided for heads and spouses than for other family members. The resulting PSID sample includes 9,824 individuals, who provide us with a total of 220,432 person-years of information. Individuals contribute 22 person-years of information to the sample, on average, although they are in the sample from 1 to 35 times.

Measuring parent status in the PSID

The PSID includes fertility histories reported separately by men and women in 1985 and updated in subsequent annual interviews. The fertility histories reported by men are known to be extremely inaccurate (Rendall et al. 1999). Adopted children are also recorded. Beginning in 1985 the PSID collected information on child support payments made, permitting men who are continuously observed to live alone (or in a couple-headed household with no children present) to be categorized as parents where appropriate. Finally, in each year it is possible to determine whether there are children age 18 or less in the household who are coded as the biological, adoptive, or step child of either the head or the spouse of the head.

We code as a “parent” in the PSID anyone who (1) reports having given birth to or having fathered a child at any point, provided that the report is given by someone at least 45 years old; or (2) ever reports paying child support; or (3) ever coresides with a minor own child or spouse’s child. This broadly construed coding scheme accords reasonably well with our broad definition of parenting, but nevertheless has some shortcomings. First, we overlook anyone—especially, absent fathers—whose only claim to “parent” status is the fact that they invest time, but no money, on behalf of noncoresident children. It seems reasonable to assume that there are relatively few such people. More problematic is the fact that even with the up-to-35-year life history potentially observed in the PSID, we may miss key parts of people’s parenting careers. For example, a man whose sole parenting experience comes from making child support payments, but whose child support behavior occurred exclusively before 1968, would be incorrectly categorized as a nonparent in our analysis. Moreover, because of patterns of nonresponse in the data, together with the sample-inclusion conditions imposed, we often observe just a few years of the potential life histories of people in the sample. Therefore some PSID respondents are likely to be incorrectly classified as nonparents.

Age profiles of fiscal flows

The PSID permits direct observation of several of the fiscal flows used in the accounting model: property tax payments (for homeowners), SSI and OASDI benefits, food stamps, unemployment compensation benefits, and military retirement benefits. Not all of these flows are included in each year’s interview; however, for all fiscal-flow variables that are observed, we pool all possible years of information in the analysis. For several fiscal flows we develop approximate life-cycle measures: for rent subsidies and public housing, the PSID includes indicator variables for the receipt of such benefits, but no information on their value. Similarly, for noninsitutional Medicaid, we know the number of recipients in a household but not the value of services received. For these three flows, we compute k ratios based on the assumption that relative flows are proportional to the receipt of services (or, in the case of Medicaid, the number of recipients). For property taxes paid by renters, we assume that taxes are equally capitalized into rents for parents and nonparents; therefore k is the age-specific ratio of rents paid by nonparents and parents. We assume that unemployment insurance premiums are proportional to earnings. The PSID provides no information on institutional Medicaid costs; for this fiscal flow, we use results for the 65-and-older population reported in Wolf (1999), which are based on data from the National Long Term Care Survey.

For several tax items, we rely on simulations produced by the National Bureau of Economic Research TAXSIM computer program (Feenberg and Coutts 1993). Many of the input fields required for TAXSIM are directly reported in the PSID. One major exception is deductible expenses, which we imputed to PSID units using a random-matching approach based on discrete classes of taxable income. TAXSIM was used to obtain estimates of federal income taxes, EITC benefits, FICA and SMI (Medicare) taxes, and state income taxes. When preparing input data files for TAXSIM, we assumed that all couples file joint returns.

Federal excise taxes and state/local sales taxes required special treatment. Using results on the effective incidence of the aggregate of these two taxes reported in Pechman (1985), in combination with data from the CBO (2007) on the incidence of federal excise taxes alone, we developed imputed values for each type of tax, taking into account family income and the nominal level of sales taxation in the respondent’s state of residence. Given the limited information available on tax incidence, our estimates of these tax amounts are limited to 1980.

We assume that benefits associated with public higher education and student aid spending are proportional to educational attainment. We treat educational attainment as a lifetime attribute, similar to parenthood itself. For Medicare costs our baseline estimates assume no differences in age-specific costs between nonparents and parents, despite evidence that the health, disability status, and longevity of the two groups differ, leading one to anticipate that Medicare costs also differ across the groups. Our findings include tests of the sensitivity of the results to the assumption that k = 1 for Medicare.

Although the accounting program treats federal and state/local budgets separately, the PSID data on which we base our estimates of age profiles of fiscal flows and, consequently, k do not distinguish between federal and state/local sources of benefits. For such flows, we use the same values of k for both federal and state/local programs. Finally, for several of the fiscal flows included in our calculations, k = 0 by definition: this is true for AFDC/TANF, school lunch programs, and elementary and secondary education.

Many of the fiscal flows measured in the PSID accrue to households, yet our accounting exercise is individually based. To account for all flows, we have divided all household-based flows (e.g., income taxes, excise and sales taxes, food stamps, subsidized rent, public housing, and so on) by 2 when the PSID unit contains both a head and a spouse. Finally, for several of the fiscal flows used in the model, we have no information upon which to base an estimate of k: corporate taxes, energy assistance, incarceration costs, refugee aid, railroad retirement, congestible goods, worker’s compensation, bilingual education, and public employee retirement plans. In such cases, we assume that k = 1. Many of the latter flows are quite small relative to total tax receipts or expenditures on benefits.

Footnotes

For details about the Health and Retirement Survey see Juster and Suzman (1995) or «http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/».

0.87 is the average proportion of parents found among the 1959 and 1960 birth cohorts in our Panel Study of Income Dynamics data; it is also the predicted proportion of parents from a trend line fitted to observed proportions for the 1941–1960 birth cohorts.

Real costs per enrollee were projected to rise at 5.8 percent per year initially, with the rate falling to 2.1 percent by 2005 and to 1.2 percent by 2020; thereafter costs per enrollee were assumed to rise at the rate of labor productivity, or 1 percent per year, as was the case for all the other age profiles. These projected increases in real costs per enrollee were then used to shift the age profiles for use of Medicare and Medicaid. See Board of Trustees (1996).

This discount rate is the real rate of return earned on the special issue US Treasury Bonds held in the Social Security Trust Fund. It is commonly taken as the “risk free” rate of return.

References

- Aykan Hakan. Effect of childlessness on nursing home and home health care use. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2003;15(1):33–53. doi: 10.1300/J031v15n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman Reagan, Dickert-Conlin Stacy. Did expanding the EITC promote motherhood? American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings. 2003;93(2):247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Blau David M, van der Klaauw Wilbert. A demographic analysis of the family structure experiences of children in the United States. Review of the Economics of the Household. 2008;6:193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. The 1996 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bommier Antoine, Lee Ronald, Miller Tim, Zuber Stéphane. Who wins and who loses? Public transfer accounts for US generations born 1850 to 2090. Population and Development Review. 2010;36(1):1–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass Larry, Lu Hsien-Hen. Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies. 2000;54:29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burggraf Shirley P. The Feminine Economy and Economic Man. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia, Furstenberg Frank., Jr . CRCW Working Paper no. 03-14-FF. Princeton University; 2003. Complex families: Documenting the prevalence and correlates of multi-partnered fertility in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Casper Wendy J, Weltman David, Kwesiga Eileen. Beyond family-friendly: The construct and measurement of singles-friendly work culture. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2007;70:478–501. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office of the United States (CBO) The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Years 1997–2006. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office of the United States (CBO) [accessed 6/25/2008];Data on the Distribution of Federal Taxes and Household Income. 2007 Online at « http://www.cbo.gov/publications/collections/taxdistribution.cfm».

- Crittenden Ann. The Price of Motherhood. New York: Metropolitan Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta Partha. Population and resources: An exploration of reproductive and environmental externalities. Population and Development Review. 2000;26(4):643–689. [Google Scholar]

- Demeny Paul. Re-linking fertility behavior and economic security in old age: A pronatalist reform. Population and Development Review. 1987;13(1):128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Doblhammer Gabriele. Reproductive history and mortality later in life: A comparative study of England and Wales and Austria. Population Studies. 2000;54:169–176. doi: 10.1080/713779087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye Jane Lawler. Current Population Reports no. P20–563. 2010. Fertility of American women: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Folbre Nancy. The cost of caring. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1999a;561:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Folbre Nancy. Who should pay for the kids? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1999b;563:194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg Daniel, Coutts Elisabeth. An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1993;12(1):189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Folbre Nancy. Valuing Children: Rethinking the Economics of the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman Vicki A. Kin and nursing home lengths of stay: A backward recurrence time approach. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34(2):138–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander Nancylee J. The relation of lifetime reproduction to survivorship in women and men: A prospective study. American Journal of Human Biology. 1996;8(6):771–783. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(1996)8:6<771::AID-AJHB9>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber Alan, MaCurdy Thomas. Predicting nursing home utilization among the high-risk elderly. In: Wise David., editor. Issues in the Economics of Aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 173–204. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel Irwin, McLanahan Sara S, Hanson Thomas L. A patchwork portrait of nonresident fathers. In: Garfinkel Irwin, McLanahan Sara S, Meyer Daniel R, Seltzer Judith A., editors. Fathers Under Fire: The Revolution in Child Support Enforcement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1998. pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler Joseph E, Duval Sue, Anderson Keith A, Kane Robert L. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S.: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. « http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2318/7/13». [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grundy Emily, Tomassini Cecilia. Fertility history and health in later life: a record linkage study in England and Wales. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(1):217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline Patrick, Timberlake Jeffrey M, Furstenberg Frank F., Jr Shifting child-rearing to single mothers: Results from 17 Western countries. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(1):47–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilber Christian AL, Mayer Christopher. Why do households without children support local public schools? NBER Working Paper No. 10804 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Hill Martha S. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics: A User’s Guide. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Juster F Thomas, Suzman Richard. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30(Supp):S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- King Leslie, Meyer Madonna Harrington. The politics of reproductive benefits: U.S. insurance coverage of contraceptive and infertility treatments. Gender and Society. 1997;11(1):8–30. doi: 10.1177/089124397011001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Øystein, Hansen Svein. Hodgkin’s disease: The protective effects of child-bearing. International Journal of Cancer. 1993;55(6):909–914. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieder Rose M. Adopted children and stepchildren: 2000. Census 2000 Special Report CENSR-6RV. 2003 « http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/censr-6.pdf».

- Lee Ronald, Miller Tim. Population policy and externalities to childbearing. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1990;510:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Ronald, Miller Tim. Project on the Economic Demography of Interage Income Reallocation, Demography. University of California-Berkeley; 1997. The life time fiscal impacts of immigrants and their descendants. Published as Chapter 7 of Smith and Edmonston. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Ronald D, Edwards Ryan D. The fiscal impact of population change. In: Little Jane Sneddon, Triest Robert K., editors. Seismic Shifts: The Economic Impact of Demographic Change. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Conference Series No. 46. 2002a. pp. 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Ronald D, Edwards Ryan D. The fiscal impacts of population aging in the U.S.: Assessing the uncertainties. In: Poterba J, editor. Tax Policy and the Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002b. [Google Scholar]

- Lino Mark, Carlson Andrea. Expenditures on Children by Families, 2008. US Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous; 2009. Publication Number 1528–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lycett John E, Dunbar Robin I, Voland Eckart. Longevity and the costs of reproduction in a historical human population. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 2000;267:31–35. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews TJ, Hamilton Brady E. Mean age of mother, 1970–2000. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002;51:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton L, Joseph, et al. Long-term fracture risk among infertile women: A population-based cohort study. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine. 2001;10:289–297. doi: 10.1089/152460901300140040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt Robert. Incentive effects of the U.S. welfare system: A review. Journal of Economic Literature. 1992;30:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mott Frank L. When is a father really gone? Paternal-child contact in father-absent homes. Demography. 1990;27:499–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill Brian C, Wexler Lee. The greenhouse externality to childbearing: a sensitivity analysis. Climatic Change. 2000;47:283–324. [Google Scholar]

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics, public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pebley Anne R. Demography and the environment. Demography. 1998;35:377–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechman Joseph A. Who Paid the Taxes, 1966–1985? Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall Michael S, Lynda Clarke H, Peters Elizabeth, Ranjit Nalini, Verropoulou Georgia. Incomplete reporting of men’s fertility in the United States and Britain: A research note. Demography. 1999;36(1):135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland Donald T. Historical trends in childlessness. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(10):1311–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Ann Marie, Kossek Ellen Ernst. Work-life policy implementation: Breaking down or creating barriers to inclusiveness? Human Resource Management. 2008;47(2):295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Sardon Jean-Paul. Childlessness. In: Demeny Paul, McNicoll Geoffrey., editors. Encyclopedia of Population. Vol. 1. Thompson Gale Publishers; 2003. pp. 128–130. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt Lucie. Effects of infertility insurance mandates on fertility. Journal of Health Economics. 2007;26(3):431–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Ulrike. Recent developments in long-term care in Germany. presented at the FAMSUP meeting; Strasbourg. 11–12 July.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smith James, Edmonston Barry., editors. The New Americans: Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Soldo Beth J, Hill Martha S. Intergenerational transfers: Economic, demographic, and social perspectives. In: Maddox George L, Lawton M Powell., editors. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Vol. 13. New York: Springer; 1993. pp. 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen Elizabeth Hervey, Chandra Anjani. Use of infertility services in the United States: 1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(3):132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott Evelyn O, et al. Reproductive history of women dying of sudden cardiac death: A case-control study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;18:589–594. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon Celine M, et al. Association of parity and ovarian cancer risk by family history of breast or ovarian cancer in a population-based study of postmenopausal women. Epidemiology. 2002;13(1):66–71. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington Leslie A. Taxes and the family: The impact of the tax exemption for dependents on marital fertility. Demography. 1992;29(2):215–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington Leslie A, Alm James, Elizabeth Peters H. Fertility and the personal exemption: Implicit pronatalist policy in the United States. American Economic Review. 1990;80(3):545–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf Douglas A. The family as provider of long-term care: Efficiency, equity, and externalities. Journal of Aging and Health. 1999;11(3):360–382. doi: 10.1177/089826439901100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf Douglas A, Laditka James N. Report to Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. Childless elderly beneficiaries’ use and costs of Medicare services. online at « http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2006/childless.pdf». [Google Scholar]

- Wolff Jennifer L, Kasper Judith D. Caregivers of frail elders: Updating a national profile. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(3):344–356. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Zhenmei, Hayward Mark D. Childlessness and the psychological well-being of older persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B(5):S311–320. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.5.s311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]