Abstract

Envelope (env) proteins of certain endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) participate in various pathophysiological processes. In this study, we characterized pathophysiologic properties of two murine leukemia virus-type ERV (MuLV-ERV) env genes cloned from the ovary of C57BL/6J mice. The two env genes (named ENVOV1 and ENVOV2), with 1,926 bp coding region, originated from two MuLV-ERV loci on chromosomes 8 and 18, respectively. ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 were ~75 kDa and predominantly expressed on the cell membrane. They were capable of producing pseudotype murine leukemia virus virions. Tropism trait and infectivity of ENVOV2 were similar to the polytropic env; however, ENVOV1 had very low level of infectivity. Overexpression of ENVOV2, but not ENVOV1, exerted cytotoxic effects and induced expression of COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, and iNOS. These findings suggest that the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 are capable of serving as an env protein for virion assembly, and they exert differential cytotoxicity and modulation of inflammatory mediators.

1. Introduction

Ancient infection of germline cells with exogenous retroviruses established a genome-wide random embedment of proviruses, called endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), and Mendelian genetics governs their inheritance to the offsprings [1]. ERVs are reported to exist in the genome of all vertebrates and constitute approximately 8% of the human genome and 10% of the mouse genome [2–4]. The majority of ERVs identified so far are reported to be defective primarily based on their inability to encode intact polypeptides for gag (group specific antigen), pol (reverse transcriptase), and env (envelope) genes, which are essential for the retroviral life cycle [5]. However, recent studies identified a number of ERVs, which retain intact coding potentials for gag, pol, and/or env genes, and some of them are reported to be associated with a range of normal physiology (e.g., placental morphogenesis) as well as pathogenic processes (e.g., multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, injury, and chronic fatigue syndrome) [6–10]. On the other hand, biology of porcine ERVs (PERVs) has been studied extensively because of the potential transmission of PERVs to humans as an adverse side effect of xenotransplantation [11].

The env glycoproteins of certain human ERVs (HERVs) have been implicated in diverse disease processes [12–16]. For instance, the env glycoproteins of HERV-K, HERV-E, and ERV-3 were characterized as tumor-associated antigens in different types of cancer [15–18]. The HERV-W env glycoprotein, called syncytin-1, is highly expressed in glial cells within central nervous system of multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune disease, patients [13]. It is proposed that potent proinflammatory properties of syncytin-1 contribute to neuronal inflammation and resultant damage to oligodendrocytes during the progression of multiple sclerosis [12]. On the other hand, syncytin-1 and HERV-FRD env glycoprotein, called syncytin-2, are reported to play an essential role during embryonic development by controlling formation of placental syncytiotrophoblasts primarily through their highly fusogenic properties [19–22]. Additional env glycoproteins have been identified and characterized from murine ERVs (syncytin-A and syncytin-B) and endogenous Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus (enJSRV), and their roles in placenta morphogenesis are similar to syncytin-1 and syncytin-2 [7, 23, 24]. The findings from recent studies provide evidence suggesting that env glycoproteins of certain ERVs play a critical role in biological processes of normal physiology as well as diseases.

During a survey of expression profile of MuLV-ERV subgenomic env transcripts in various normal tissues of C57BL/6J mice, two putative full-length env transcripts were identified in the ovary. In this study, the biological characteristics of these two MuLV-ERV env genes, named ENVOV1 and ENVOV2, were investigated by examining a selective set of pathophysiologic parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Female C57BL/6J mice (approximately 12 weeks old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Me) and housed according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health. The Animal Use and Care Administrative Advisory Committee of the University of California, Davis, approved the experimental protocol. Three mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation for tissue collection without any pretreatment, and tissue samples were snap-frozen.

2.2. RT-PCR Analyses

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis were performed primarily according to the relevant protocols provided by the kit manufacturer. Briefly, total RNAs were extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif) and cDNAs were synthesized using 100 ng of total RNA from each sample (tissue or cell) and the Sensiscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen). The primers capable of amplifying the full length as well as subgenomic MuLV-ERV transcripts were designed based on the MAIDS (murine acquired immunodeficiency virus) virus-related provirus (GenBank No. S80082) [25]: forward, 5′-CAT TTG GAG GTC CCA CCG AGA-3′ (MV1K) and reverse, 5′-CTC AGT CTG TCG GAG GAC TG-3′ (MV2D). The following are the primer sets used for inflammatory mediators: COX-2 (forward, 5′-ACA CAG TGC ACT ACA TCC TGA C-3′ and reverse, 5′-ATC ATC TCT ACC TGA GTG TC-3′), ICAM-1 (forward, 5′-AGC TGT TTG AGC TGA GCG AGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTG TCG AAC TCC TCA GTC A-3′), IL-1β (forward, 5′-GAC AGT GAT GAG AAT GAC CTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAA CTC TGC AGA CTC AAA CTC CA-3′), IL-6 (forward, 5′-GCC TTC CCT ACT TCA CAA GTC CG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAC TAG GTT TGC CGA GTA GAT CTC-3′) [26], iNOS (forward, 5′-ACA AGC TGC ATG TGA CAT CGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAG AGC CTG AAG TCA TGT TTG C-3′), and TNF-α (forward, 5′-GCA TGA TCC GCG ACG TGG AA-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGA TCC ATG CCG TTG GCC AG-3′) [27]. In addition, β-actin (forward, 5′-CCA ACT GGG ACG ACA TGG AG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTA GAT GGG CAC AGT GTG GG-3′) was used as an internal expression control [28]. The density of amplified products (applied only for inflammatory mediators) was measured using KODAK Molecular Imaging Software ver. 4.5 (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY), and it was normalized to β-actin control.

2.3. Cloning and Sequencing of env Transcripts

The RT-PCR products of the MuLV-ERV subgenomic transcripts (~2.9 Kb) were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, Wis) followed by plasmid DNA preparation using a kit from Qiagen, and sequencing analysis at Davis Sequencing Inc (Davis, Calif) or Molecular Cloning Laboratory (South San Francisco, Calif). DNA sequences were analyzed using Vector NTI-ver. 10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif) or Editseq and MegAlign program within DNASTAR ver. 8.0.2 (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis).

2.4. Construction of ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 Expression Vectors

The coding regions of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 were amplified by PCR from their respective original cDNA clones using a set of primers embedded with restriction enzyme sites for cloning into the pcDNA4/HisMax (Invitrogen): forward with NotI, 5′-CGC GGC GGC CGC ATG GAA GGT CCA GCG TTC TC-3′, ENVOV1-reverse with XhoI, 5′-GGC TCG AGT TAT TCA CGT GAT TCC ACT TTT TCT GG-3′, and ENVOV2-reverse with XhoI, 5′-GGC TCG AGT TAT TCA CGT GAT TCC ACT TCT TCT GG-3′. The amplified coding sequences after 10 PCR cycles were cloned into the pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega) followed by digestion with NotI and XhoI and subsequently cloned into pcDNA4/HisMax (Invitrogen).

2.5. Cell Lines

The GP2-293 packaging cells (purchased from Clontech, Mountain View, Calif), tsA201 cells (a derivative of HEK293 cells), COS-7 cells, and COS-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, streptomycin, and penicillin G. Five other cell lines (HeLa, Neuro-2a, MDCK, HCT 116, and NIH3T3) were cultured according to the protocols recommended by the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va).

2.6. Assays for Production, Tropism, and Infectivity of Pseudotype LacZ-MuLV Virions

The GP2-293 cells, which were seeded onto a 6-well plate at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells per well, were cotransfected with pQCLIN (Clontech, Mountain View, Calif) and pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV1 or pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV2 plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The following env proteins were used for tropism and infectivity controls: ecotropic (pEco), 4070A amphotropic (pAmpho), 10A1 amphotropic (p10A1) with a broader host range than 4070A, and G glycoprotein of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G) (Clontech). Culture supernatants containing pseudotype viral particles were passed through a 0.45 μM filter (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa). Transfection efficiency was estimated by counting the stained cells under the microscope after X-gal staining.

For each cell line (a total of 8 cell lines) employed for tropism and infection analysis, 5 × 104 cells/well were seeded onto a 24-well plate and incubated overnight in preparation of viral transduction. Subsequently, the medium was replaced with 0.5 mL of serial dilutions of culture supernatants containing pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virions, in which Polybrene (Sigma, Milwaukee, Wis) was added (8 μg/mL), followed by washing after 4 hours and incubation with 0.5 mL of fresh media for 2 days. The infected cells were treated with fixing solution (2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS) and stained with X-gal solution. Cells stained blue were counted under the microscope as an infection unit.

2.7. Western Blot Analyses

To confirm expression of the pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV1 or pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV2 construct, Western blot analysis was performed following transfection into tsA201 cells using Fugene 6 reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). At 2 days after transfection, the cells were harvested, and Western blot analysis was performed. Briefly, the membrane, blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk (NFDM), was incubated with a goat antibody specific for gp69/71 of Rauscher MuLV (1 : 2000 dilution with 5% NFDM in TBST [Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20]) obtained from ViroMed Biosafety Laboratories (Camden, NJ) followed by an anti-goat-HRP antibody (1 : 5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif). The protein signal was visualized using ECL reagents (GE healthcare, Pittsburgh, Pa). A similar protocol was used to detect env glycoprotein from supernatants of the GP2-293 cells producing pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virions.

2.8. Immunocytochemistry

HeLa cells, which were transfected with the pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV1 or pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV2 construct, were harvested and transferred into 0.1% poly-L-Lysine coated coverslips and incubated for 1 day. Cells were then immunostained with a goat antibody specific for gp69/71 (1 : 200 diluted in culture medium, ViroMed Biosafety Laboratories) and fixed with both 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were incubated with a Texas-Red-conjugated antigoat IgG secondary antibody (1 : 200 diluted in PBS, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif) and stained cells were visualized by a Zeiss microscope using AxioVison software version 4.5 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

2.9. Cytotoxicity and Cell Proliferation Assays

HeLa cells, which were transfected with the pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV1 or pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV2 construct, were subjected to cytotoxicity assay using a Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Roche, South San Francisco, Calif) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm with a reference at 600 nm using a reader from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, Calif). Cell proliferation rate was measured from these cells using the colorimetric MTT (3- (4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Sigma, Milwaukee, Wis) assay as described previously [29]. Absorbance was read at 560 nm with a reference at 600 nm using a reader (Molecular Devices). All experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and 4 independent experiments were repeated.

2.10. Analysis of Inflammatory Mediators

RAW264.7 cells, which were transfected with the pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV1 or pcDNA4/HisMax-ENVOV2 construct, were harvested at 1 day after transfection, and they were examined for expression of a set of inflammatory mediators at mRNA levels by RT-PCR, and the relevant protocols and reagents are described in Section 2.2 above.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student's t-test and statistical significance was determined as *P < .05 and **P < .01.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Initial Characterization of Two MuLV-ERV env Subgenomic Transcripts Expressed in the Ovary of C57BL/6J Mice

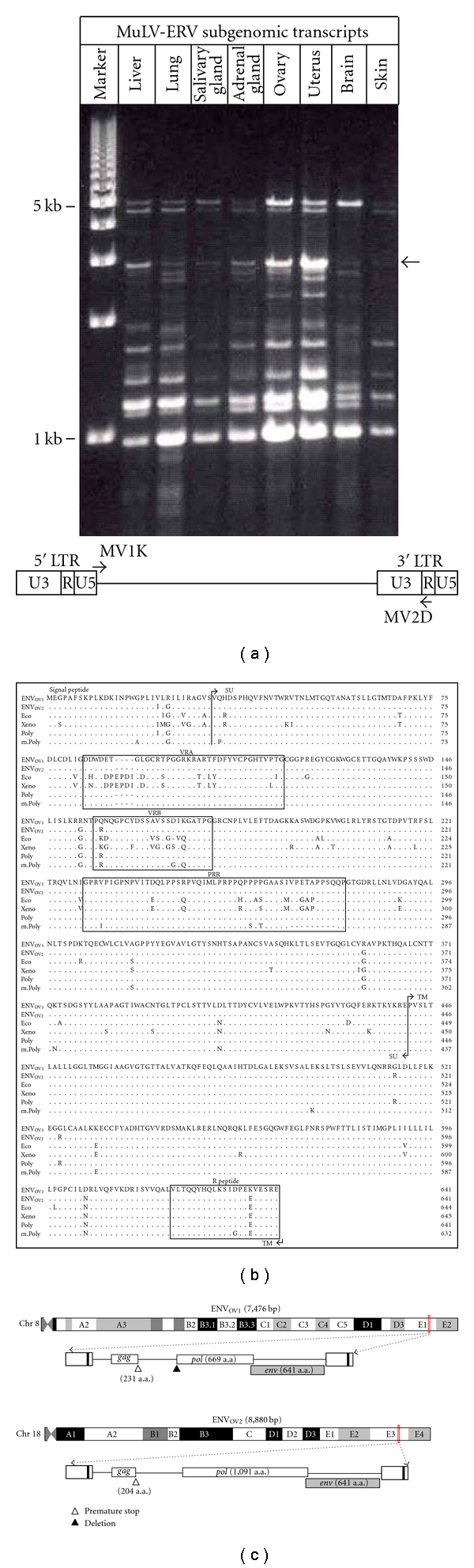

The expression profiles of MuLV-ERV env genes in various normal tissues (liver, lung, salivary gland, adrenal gland, brain, skin, ovary, and uterus) of C57BL/6J mice were investigated. A number of putative subgenomic transcripts with varying sizes, ranging from ~1 Kb to ~5 Kb, which may be generated by splicing and/or deletion, were differentially expressed in each tissue. Among them were ~2.9 Kb bands presumed to be amplified from full-length MuLV-ERV env transcripts, and their expression was evident in the ovary and uterus as well as other tissues (Figure 1(a)). Sequencing analysis revealed that the two 2,892 bp transcripts were env mRNAs, which were generated by a single splicing using the well-characterized donor and acceptor signals [30]. A subsequent open reading frame analysis revealed that the two full-length MuLV-ERV env genes, named ENVOV1 and ENVOV2, retain intact coding potential for env glycoproteins of 641 amino acids. While the nucleotide and polypeptide sequences of the ENVOV2 was identical to an env gene of an polytropic murine leukemia virus (MuLV)-related retroviral sequence from NFS/N mice, the ENVOV1 has not been reported yet [31].

Figure 1.

Identification of full-length env transcripts from the ovary of C57BL/6J mice. (a) A number of MuLV-ERV subgenomic transcripts were expressed in normal tissues (liver, lung, salivary gland, adrenal gland, brain, and skin) of C57BL/6J mice. A schematic diagram indicates the locations of primers used for amplification of the subgenomic transcripts. (b) The amino acid sequences of two intact env genes, named ENVOV1 and ENVOV2, which were isolated from the ovary (indicated with an arrow in panel (a)), were compared to reference env polypeptides with known tropism traits (GeneBank accession number: AAG39911 (Eco), ACY30460 (Xeno), AAO37283 (Poly), and AAA88318 (m.Poly)). (c) The putative MuLV-ERV proviruses harboring the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 genes were mapped to chromosomes 8 and 18 of C57BL/6J genome, respectively. SU (surface domain), TM (transmembrane domain), VRA (variable region A), VRB (variable region B), PRR (proline rich region), LTR (long terminal repeat), R (repeat), and U (unique region).

Prior to the functional characterization of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2, they were aligned with four different reference env polypeptides displaying different host tropisms: ecotropic, xenotropic, polytropic, and modified polytropic (Figure 1(b)). It turned out that both ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 had a higher level of sequence similarity to the polytropic/modified polytropic env polypeptides compared to the others. Both the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 share the identical sequence in the variable region A and proline rich region, while one amino acid residue was different in the variable region B and R peptide, respectively. To identify the putative MuLV-ERVs encoding the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2, respectively, the C57BL/6J genome sequence (Build 37.1) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was surveyed with the respective env nucleotide sequences using the BLAST program [32]. The putative proviruses presumed to encode the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 were mapped to ideogram data of chromosome 8 and ideogram data of chromosome 18, respectively. Both MuLV-ERVs retained the coding potential for env polypeptide, and ENVOV2 also had the coding potential for pol polypeptide (Figure 1(c)).

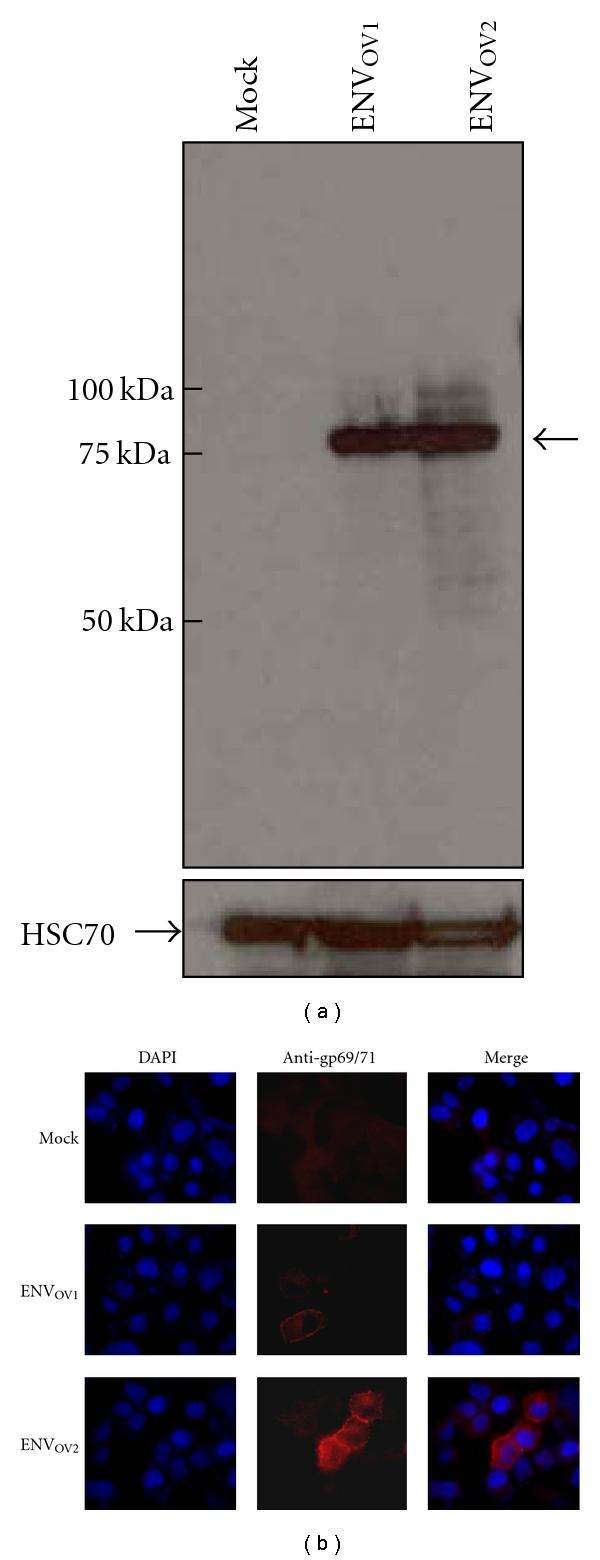

To examine whether the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 are able to produce full-length env polypeptides, they were overexpressed in a human cell line followed by Western blot detection using an anti-gp69/71 (env) antibody. A protein band of ~75 kDa, which was about the size of MuLV-ERV env polypeptides, was detected (Figure 2(a)). Moreover, the subcellular distribution of these env polypeptides was examined by transient transfection followed by immunocytochemistry using the same antibody used for the Western blot analysis. Both the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 proteins were evidently expressed on the cell membrane as was expected from the retroviral env polypeptides (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Coding potential and membrane localization of ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides. (a) The coding potential of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides was confirmed by overexpression followed by Western blot analysis using antibody against Rauscher MuLV gp69/71 env polypeptide. (b) The cellular distribution of the overexpressed ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides was examined by immunocytochemistry using antibody against Rauscher MuLV gp69/71 polypeptide, and their membrane staining pattern was evident. The cells transfected with a blank plasmid serves as a negative control (mock). DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

3.2. Infectivity and Tropism Traits of ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 Polypeptides

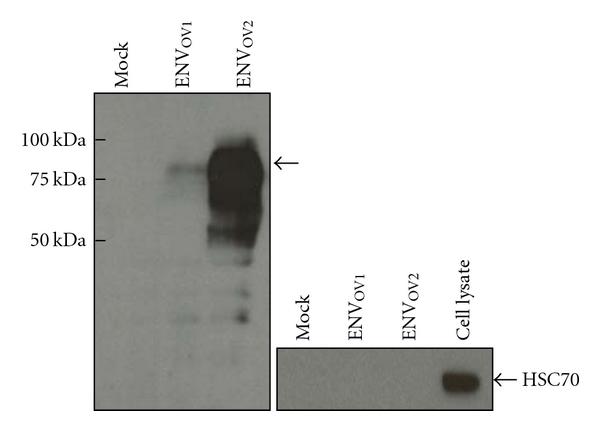

Two relevant characteristics, tropism and infectivity, of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides were determined using a retroviral packaging system and compared to reference env proteins with known host tropisms: ecotropic, amphotropic, and pantropic. Prior to the analyses of infectivity and tropism traits, the packaging potential of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides and release of pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virions were confirmed by detection of ~75 kDa bands in the culture supernatants collected after transfection (Figure 3). Interestingly, a markedly higher level of env protein was detected in the supernatants presumed to contain ENVOV2-packaged pseudotype virions compared to the ENVOV1 samples. This finding may suggest that the ENVOV2 polypeptide is more efficiently produced and/or packaged during the course of virion assembly compared to the ENVOV1. The infectivity and tropism traits of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides were then examined by infection of various cell types derived from human, nonhuman primate, mouse, and dog. It revealed that the pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virions packaged with either ENVOV1 or ENVOV2 were capable of infecting both mouse as well as nonmouse cells suggesting their polytropic tropism trait, which is consistent with the alignment data presented in Figure 1 (Table 1). While the pseudotype ENVOV2-LacZ-MuLV virions demonstrated infectivity that is very similar to the amphotropic and pantropic controls, the ENVOV1-LacZ-MuLV virions had substantially low infection titers compared to the controls, probably due to low expression level and/or inefficient packaging potential during virion assembly.

Figure 3.

Production of pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virions. Presence of the pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virus particles in culture supernatants of the GP2-293 packaging cells was confirmed by detection of the env polypeptides using antibody against Rauscher MuLV gp69/71. Arrow indicates the env polypeptides. Supernatants collected from cells transfected with a blank plasmid serves as a negative control (mock).

Table 1.

Tropism trait and infectivity of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides. Infection titer unit (U/mL): number of LacZ positive cells per mL of supernatant containing virus particles. ND: not detectable.

| Cell lines | Infection titer (U/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENVOV1 | ENVOV2 | pEco | pAmpho | p10A1 | pVSVG | |

| Human | ||||||

| HeLa | 1.6 × 101 | 1.5 × 104 | ND | 2.2 × 104 | 2.2 × 104 | 4.7 × 104 |

| tsA201 | 3.1 × 101 | 2.0 × 106 | ND | 2.8 × 106 | 1.4 × 106 | 8 × 106 |

| HCT116 | 2.0 × 101 | 3.2 × 104 | ND | 2.7 × 104 | 4.0 × 104 | 1.7 × 104 |

|

| ||||||

| Nonhuman primate | ||||||

| COS-1 | 4.0 × 101 | 2.0 × 105 | ND | 2.0 × 105 | 3.8 × 105 | 1.2 × 105 |

| COS-7 | 6.9 × 101 | 8.4 × 105 | ND | 1.3 × 106 | 3.2 × 106 | 5.2 × 106 |

|

| ||||||

| Mouse | ||||||

| NIH3T3 | 2.0 × 101 | 9.5 × 104 | 4.5 × 105 | 1.7 × 104 | 3.3 × 104 | 1.4 × 104 |

| Neuro2a | ND | 2.1 × 104 | 4.4 × 103 | 2.7 × 103 | 2.1 × 103 | 4.8 × 103 |

|

| ||||||

| Dog | ||||||

| MDCK | ND | 3.2 × 101 | ND | 3.2 × 102 | 2.6 × 102 | 1.2 × 102 |

3.3. Cytopathic Characteristics of ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 Polypeptides

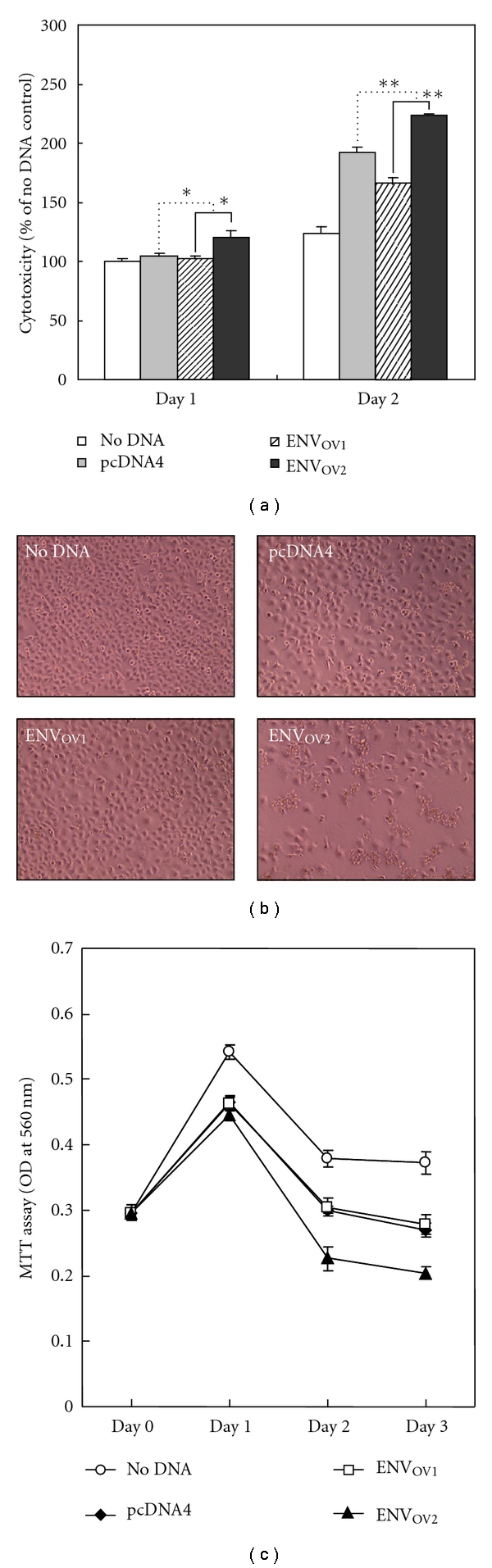

In this experiment, the cytopathic effects of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides were examined by overexpression followed by measurement of cytotoxicity and inhibition of cell proliferation. Cytotoxic property of the ENVOV2 polypeptide was clearly demonstrated by both colorimetric quantitative assay and microscopic examination of morphological characteristics, including adherence to culture plate (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). In contrast, no significant cytotoxic effects were observed in the cells overexpressed with the ENVOV1 polypeptide compared to negative controls. On the other hand, the overexpression of the ENVOV2 polypeptide, but not ENVOV1 polypeptide, evidently inhibited cell proliferation, which was measured by colorimetric quantitation of cell growth (Figure 4(c)). It is likely that inhibition of cell proliferation by the ENVOV2 polypeptide is linked to its cytotoxic effect, and it is unclear how its high infection titer correlates with the cytopathic characteristics.

Figure 4.

Cytopathic effects of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides. (a) and (b) Cytotoxic property of the ENVOV2 polypeptide, but not ENVOV1 polypeptide, was observed during cytotoxicity assay by measurement of lactate dehydrogenase release and morphologic examination of cells (200x magnification). The degree of cytotoxicity was normalized to the no DNA (Panel (a)). (c) ENVOV2 polypeptide's inhibitory effect on cell proliferation was demonstrated by MTT assay, which measures cell viability, following overexpression. All experiments were performed in triplicate. ∗ and ∗∗ indicate statistical significance (*P < .05; **P < .01).

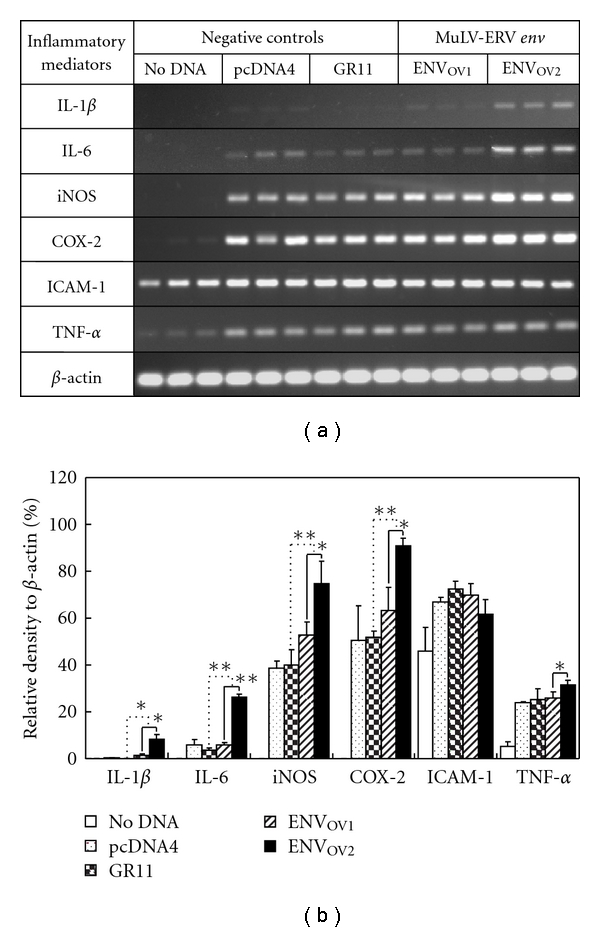

3.4. Modulation of Inflammatory Mediators by ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 Polypeptides

To investigate whether the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 play a role in inflammation, changes in mRNA expression of a set of inflammatory mediators were surveyed following their overexpression in RAW264.7 alveolar macrophage cells. The set include proinflammatory mediators of COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2), ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1), iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase), IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. The expression of four proinflammatory mediators, COX-2, iNOS, IL-1β, and IL-6, was significantly increased by overexpression of ENVOV2 polypeptide but not ENVOV1 (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)). In contrast, no significant changes in ICAM-1 and TNF-α levels were detected following the overexpression of either the ENVOV1 or the ENVOV2 polypeptide. The findings from this study suggest that the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides differentially participate in certain signaling events controlling the production of inflammatory mediators.

Figure 5.

Effects of ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides on expression of inflammatory mediators. (a) and (b) The effects of the ENVOV1 or ENVOV2 polypeptide in RAW264.7 on the expression of various inflammatory mediators are presented. Differential modulation potentials for inflammatory mediators were observed between ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides. The densitometric value of each inflammatory mediator was normalized to β-actin, and a graph was formulated. Three different forms of negative control were included in this experiment: no DNA, pcDNA4 (blank pcDNA4/HisMax plasmid), and GR11 (similar insert size as ENVOV1 and ENVOV2: mouse glucocorticoid receptor in pcDNA4/HisMax). The assay was performed in triplicate. ∗ and ∗∗ indicate statistical significance (*P < .05; **P < .01).

4. Discussion

Two MuLV-ERV env genes with intact coding potential, named ENVOV1 and ENVOV2, were isolated from the ovary of normal C57BL/6J mice and their biological properties were characterized. Although the sequence of one (ENVOV2) of the two env genes has been reported previously, its biological functions have not been characterized [31]. The findings from this study suggest that both the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides, which were determined to confer polytropic tropism, participate in a range of biological processes, such as retroviral packaging, cell death, proliferation, and inflammation.

The results from this study suggest that putative MuLV-ERVs, or unidentified exogenous retroviruses, which are packaged with either ENVOV1 or ENVOV2 polypeptide, are capable of infecting cells of mice as well as other species, such as humans, nonhuman primates, and dogs. De novo as well as stress-related activation of the MuLV-ERVs, which are packaged with these env polypeptides, may be followed by infection of specific cells of local as well as distant. In addition to the potential cytopathic effects examined in this study, the genomic random integration of the proviral DNAs may be directly linked to various pathogenic outcomes following infection. Further in vivo studies are needed to determine infectivity of the MuLV-ERVs packaged with these env polypeptides in mice as well as other species.

ERVs have been associated with a range of diseases, such as sepsis, multiple sclerosis, and injury whose central pathology includes inflammatory conditions [12, 33–37]. Some reports provided evidence that certain ERV env gene products, but not the relevant virus particles, play a role in the inflammatory processes associated with various pathologic phenotypes [38, 39]. The HERV-W syncytin-1 exerted its inflammatory effects by induction of proinflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, iNOS, and TNF-α, leading to neuron inflammation in multiple sclerosis patients [12, 40]. The findings from this study that the ENVOV2 polypeptide is capable of modulating inflammatory mediators suggest its potential roles in immunologic homeostasis as well as in various diseases involving inflammatory conditions, such as sepsis [41, 42].

A markedly higher level of packaging and subsequent release of pseudotype LacZ-MuLV virions was predicted with the ENVOV2 compared to the ENVOV1, based on the detection of abundant env polypeptide in the culture supernatants of ENVOV2 samples. It is consistent with the finding that the ENVOV2-packaged virions (pseudotype ENVOV2-LacZ-MuLVs) had higher infection titers compared to the ENVOV1-packaged virions (pseudotype ENVOV1-LacZ-MuLVs). It is possible that the putative high packaging rate with the ENVOV2 polypeptide is directly linked to its efficient transcription and/or translation as well as stability. On the other hand, abundant presence of the ENVOV2 polypeptide in the cytoplasm may explain, at least in part, the characteristics of cytotoxicity and inhibition of proliferation compared to the ENVOV1. Throughout the entire coding sequences, nine amino acid residues (V22I, R24G, R158G, Q161R, R362G, G518R, G528R, D608, and K640E) were different between the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides. Further investigation may be needed to learn the roles of these polymorphic residues in stability as well as pathogenic characteristics, including infectivity, of the ENVOV1 and ENVOV2 polypeptides.

5. Conclusions

The findings from this study indicate that certain MuLV-ERV env polypeptides, such as ENVOV2, may participate in a range of pathophysiologic processes as an envelope of MuLV-ERV virions and/or independently.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Shriners of North America (no. 86800 to K. Cho and no. 84308 to Y.-K. Lee [postdoctoral fellowship]) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM071360 to K. Cho).

References

- 1.Boeke JD, Stoye JP. Retrotransposons, endogenous retroviruses, and the evolution of retroelements. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1997. pp. 343–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths DJ. Endogenous retroviruses in the human genome sequence. Genome Biology. 2001;2(6, article 1017) doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herniou E, Martin J, Miller K, Cook J, Wilkinson M, Tristem M. Retroviral diversity and distribution in vertebrates. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(7):5955–5966. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5955-5966.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420(6915):520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gifford R, Tristem M. The evolution, distribution and diversity of endogenous retroviruses. Virus Genes. 2003;26(3):291–316. doi: 10.1023/a:1024455415443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clausen J. Endogenous retroviruses and MS: using ERVs as disease markers. International MS Journal. 2003;10(1):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlap KA, Palmarini M, Varela M, et al. Endogenous retroviruses regulate periimplantation placental growth and differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(39):14390–14395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603836103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson H, Bachmann S, Schröder J, McArthur J, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Retroviral RNA identified in the cerebrospinal fluids and brains of individuals with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(8):4634–4639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061021998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombardi VC, Ruscetti FW, Gupta JD, et al. Detection of an infectious retrovirus, XMRV, in blood cells of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Science. 2009;326(5952):585–589. doi: 10.1126/science.1179052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yolken RH, Karlsson H, Yee F, Johnston-Wilson NL, Torrey EF. Endogenous retroviruses and schizophrenia. Brain Research Reviews. 2000;31(2-3):193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss RA. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nature Medicine. 1997;3(3):282–286. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antony JM, Ellestad KK, Hammond R, et al. The human endogenous retrovirus envelope glycoprotein, syncytin-1, regulates neuroinflammation and its receptor expression in multiple sclerosis: a role for endoplasmic reticulum chaperones in astrocytes. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179(2):1210–1224. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antony JM, van Marle G, Opii W, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus glycoprotein-mediated induction of redox reactants causes oligodendrocyte death and demyelination. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(10):1088–1095. doi: 10.1038/nn1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Parseval N, Forrest G, Venables PJW, Heidmann T. ERV-3 envelope expression and congenital heart block: what does a physiological knockout teach us. Autoimmunity. 1999;30(2):81–83. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang-Johanning F, Frost AR, Jian B, et al. Detecting the expression of human endogenous retrovirus E envelope transcripts in human prostate adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98(1):187–197. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang-Johanning F, Frost AR, Jian B, Epp L, Lu DW, Johanning GL. Quantitation of HERV-K env gene expression and splicing in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22(10):1528–1535. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson E, Andersson AC, Nilsson BO. Expression of an endogenous retrovirus (ERV3 HERV-R) in human reproductive and embryonic tissues—evidence for a function for envelope gene products. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 1994;99(2):113–120. doi: 10.3109/03009739409179354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang-Johanning F, Liu J, Rycaj K, et al. Expression of multiple human endogenous retrovirus surface envelope proteins in ovarian cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;120(1):81–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frendo JL, Olivier D, Cheynet V, et al. Direct involvement of HERV-W Env glycoprotein in human trophoblast cell fusion and differentiation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23(10):3566–3574. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3566-3574.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malassiné A, Blaise S, Handschuh K, et al. Expression of the fusogenic HERV-FRD Env glycoprotein (syncytin 2) in human placenta is restricted to villous cytotrophoblastic cells. Placenta. 2007;28(2-3):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sha M, Lee X, Li XP, et al. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature. 2000;403(6771):785–789. doi: 10.1038/35001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blond JL, Lavillette D, Cheynet V, et al. An envelope glycoprotein of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-W is expressed in the human placenta and fuses cells expressing the type D mammalian retrovirus receptor. Journal of Virology. 2000;74(7):3321–3329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3321-3329.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupressoir A, Marceau G, Vernochet C, et al. Syncytin-A and syncytin-B, two fusogenic placenta-specific murine envelope genes of retroviral origin conserved in Muridae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(3):725–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406509102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong R, Huang L, Shi J, et al. Syncytin-A mediates the formation of syncytiotrophoblast involved in mouse placental development. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2007;20(5):517–526. doi: 10.1159/000107535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho BC, Shaughnessy JD, Largaespada DA, et al. Frequent disruption of the Nf1 gene by a novel murine AIDS virus-related provirus in BXH-2 murine myeloid lymphomas. Journal of Virology. 1995;69(11):7138–7146. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7138-7146.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, et al. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437(7062):1167–1172. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho K, Adamson LK, Greenhalgh DG. Parallel self-induction of TNF-α and apoptosis in the thymus of mice after burn injury. Journal of Surgical Research. 2001;98(1):9–15. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YK, Chew A, Phan H, Greenhalgh DG, Cho K. Genome-wide expression profiles of endogenous retroviruses in lymphoid tissues and their biological properties. Virology. 2008;373(2):263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horiuchi M, Itoh A, Pleasure D, Itoh T. MEK-ERK signaling is involved in interferon-γ-induced death of oligodendroglial progenitor cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(29):20095–20106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mount SM. A catalogue of splice junction sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 1982;10(2):459–472. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans LH, Lavignon M, Taylor M, Alamgir ASM. Antigenic subclasses of polytropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) isolates reflect three distinct groups of endogenous polytropic MLV-related sequences in NFS/N mice. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(19):10327–10338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10327-10338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho K, Chiu S, Lee YK, Greenhalgh D, Nemzek J. Experimental polymicrobial peritonitis-associated transcriptional regulation of murine endogenous retroviruses. Shock. 2009;32(2):147–158. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31819721ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho K, Greenhalgh D. Injury-associated induction of two novel and replication-defective murine retroviral RNAs in the liver of mice. Virus Research. 2003;93(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho K, Pham T, Adamson L, Greenhalgh D. Regulation of murine endogenous retroviruses in the thymus after injury. Journal of Surgical Research. 2003;115(2):318–324. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee Y-K, Chew A, Fitzsimon L, Thomas R, Greenhalgh D, Cho K. Genome-wide changes in expression profile of murine endogenous retroviruses (MuERVs) in distant organs after burn injury. BMC Genomics. 2007;8, article 440 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasmussen HB, Geny C, Deforges L, et al. Expression of endogenous retroviruses in blood mononuclear cells and brain tissue from multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis. 1995;1(2):82–87. doi: 10.1177/135245859500100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rolland A, Jouvin-Marche E, Saresella M, et al. Correlation between disease severity and in vitro cytokine production mediated by MSRV (multiple sclerosis associated retroviral element) envelope protein in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2005;160(1-2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saresella M, Rolland A, Marventano I, et al. Multiple sclerosis-associated retroviral agent (MSRV)-stimulated cytokine production in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2009;15(4):443–447. doi: 10.1177/1352458508100840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rolland A, Jouvin-Marche E, Viret C, Faure M, Perron H, Marche PN. The envelope protein of a human endogenous retrovirus-W family activates innate immunity through CD14/TLR4 and promotes Th1-like responses. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(12):7636–7644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bone RC. Toward a theory regarding the pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: what we do and do not know about cytokine regulation. Critical Care Medicine. 1996;24(1):163–172. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199601000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozbalkan Z, Aslar AK, Yildiz Y, Aksaray S. Investigation of the course proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines after burn sepsis. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2004;58(2):125–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.0106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]