Abstract

In this paper we develop and test a new approach to explain the link between social factors and individual offending. We argue that seemingly disparate family, peer, and community conditions lead to crime because the lessons communicated by these events are similar and promote social schemas involving a hostile view of people and relationships, a preference for immediate rewards, and a cynical view of conventional norms. Further, we posit that these three schemas are interconnected and combine to form a criminogenic knowledge structure that gives rise to situational interpretations legitimating criminal behavior. Structural equation modeling with a sample of roughly 700 hundred African American teens provided strong support for the model. The findings indicated that persistent exposure to adverse conditions such as community crime, discrimination, harsh parenting, deviant peers and low neighborhood collective efficacy increased commitment to the three social schemas. The three schemas were highly intercorrelated and combined to form a latent construct that strongly predicted increases in crime. Further, in large measure the effect of the various adverse conditions on increases in crime was indirect through their impact on this latent construct. We discuss the extent to which the social schematic model presented in the paper might be used to integrate concepts and findings from several of the major theories of criminal behavior.

“The history of science clearly indicates that as the understanding of causal processes develops, what initially appears extremely complex ultimately proves to reduce to a relatively small number of mediating mechanisms. Clearly, this reduction is needed in the field of antisocial behavior…”

(Rutter 2003).

Studies indicate that perpetrators tend to view their criminal actions as legitimate and acceptable given the prevailing circumstances (Baumeister, 1997; Giordano et al., 2002; Katz, 1988). Offenders do not usually see their behavior as evil or immoral. Instead, they consider their deeds to have been sensible, necessary, inevitable, or compelled by the exigencies of the situation (Katz, 1988; Shermer, 2004; Steffensmeier & Ulmer, 2005; Sykes & Matza 1957). In many instances, offenders perceive their actions as a moralistic pursuit of justice calculated to address some injustice or grievance (Black, 1998; Katz, 1988). Following arrest, perpetrators almost always find public portrayal of their crimes to be dramatically different than the meaning that they attributed to their behavior at the time of the offense (Baumeister, 1997; Black, 1998). This suggests that the challenge in explaining crime is identifying the factors that cause some individuals to perceive that illegal actions are warranted, necessary, and/or justified. We need a theory that specifies the social circumstances and life lessons that foster this deviant view of reality.

Questions about learning naturally suggest a social learning framework, which in criminology is dominated by Akers’ social learning theory (Akers, 1998; Akers & Sellers, 2009). According to Akers’ model, social learning takes place through imitation and reinforcement. Individuals attain definitions either favorable or unfavorable to the commission of crime as a consequence of imitation and reinforcement in their everyday environment. Consonant with this perspective, the present paper is concerned with identifying the processes whereby adverse social circumstances influence situational definitions favorable to the commission of crime. We depart from Akers’ social learning theory, however, by shifting the emphasis from operant learning to the messages or principles communicated by persistent and recurring circumstances that comprise an individual’s everyday existence. Rather than focusing upon schedules of reinforcement, we accent the lessons or tenets implicit in the repetitive patterns of interaction occurring within a person’s social space. The heuristic value of this altered focus is that it suggests a common set of avenues whereby seemingly disparate social environments foster crime.

Past research has provided strong evidence that exposure to community disorganization (e.g., Sampson et al., 2002), harsh parenting (e.g., Reid, Patterson, & Snyder., 2002), deviant peers (e.g., Warr, 2002), racial discrimination (e.g., Simons et al., 2003), and a wide variety of other adverse circumstances (Agnew, 2006) increase the chances that a person will engage in criminal behavior. In the following pages, we argue that this is the case because the lessons communicated by these events promote social schemas that combine to form a criminogenic knowledge structure that shapes situational interpretations legitimating or compelling criminal and antisocial behavior. We test this social schematic perspective on crime using longitudinal data from roughly 700 African American adolescents. Finally, we discuss the implications of this new social learning approach to explaining crime.1

LESSONS AND SCHEMAS

Numerous theories in social and developmental psychology (Baldwin, 1992; Cassidy & Shaver, 2008; Dodge & Pettit, 2003) and in cultural sociology (Bourdieu, 1990, 1998; Meisenhelder, 2006) suggest that social schemas serve as the link between past experiences and future behavior. Social schemas are internalized representations of the patterns inherent in past social interactions that guide the processing of future social cues (Crick & Dodge, 1994). They are abstract principles and dispositions that are tacitly relied upon when perceiving situations and forming lines of action (Bordieu, 1990; Meisenhelder, 2006). All situations involve a vast array of stimuli and social schemas simplify the task of processing that information as they specify the regularities, patterns, or rules of everyday life (Dodge & Pettit, 2003). These simplifying principles make defining and responding to situations more efficient as they suggest which cues are most important, the meaning of these stimuli, and the likely consequence of various courses of action (Baldwin, 1992; Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Social schemas are durable as they are the internalization of patterns intrinsic to the repeated and persistent interactions to which the individual has been exposed, and they are transposable in that they are carried into new settings and situations (Bordieu, 1990,Bordieu, 1998; Sallaz & Zavisca, 2007). Humans who inhabit the same position in the social world develop comparable constellations of schemas (Bourdieu, 1984, 1990; Crick & Dodge, 1994). Similar conditions of existence result in a common set of schemas, with the consequence being similar expectations, choices, and lines of action.

Offenders are more likely than their conventional counterparts to have experienced difficulties and challenges relating to community disadvantage, inept parenting, discrimination, affiliation with deviant peers, and the like. These various hardships and disadvantages are so disparate that one might assume that each of them influences involvement in crime through a separate and unique avenue. Indeed, this is the assumption of many theories of crime. In contrast, we posit that these family, peer, and community conditions increase crime through a common mechanism: they teach a mutual set of lessons that are internalized as social schemas that justify crime. This collection of schemas includes a hostile view of relationships, a concern with immediate gratification, and a cynical view of conduct norms. These schemas, each of which is discussed below, closely correspond to cognitive constructs that extant work has linked to offending. Specifically, they relate to theory and research concerned with hostile attributions (Dodge, 2006; Dodge et al., 1990), low self-control (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990), and commitment to conventional norms (Akers, 1998; Bandura et al., 1996; Hirschi, 1969), respectively.

We expect that these social schemas are correlated and coexist. Our rationale for this prediction is twofold. First, these schemas represent mental structures that are a function of the same set of social conditions such as poor parenting and bad neighborhoods. Second, as argued below, there is good reason to believe that these deviant schemas impact one another. A hostile view of relationships, in particular, is likely to foster belief in the other two schemas. We now turn to consideration of each of the three schemas that comprise the criminogenic knowledge structure.

HOSTILE VIEW OF RELATIONSHIPS

Numerous studies (Bowlby, 1982; Baldwin, 1992; Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2001) have documented the way that relationship schemas influence a person’s interaction with others. These studies indicate that individuals who possess an optimistic, trusting model of relationships engage in warm, cooperative interactions with other people, whereas those who hold a hostile, distrusting model approach others with suspicion and aggression. Given their cynical view of relationships, persons who hold a hostile view of relationships assume that most people are unfair and cannot be trusted to reciprocate. They expect to be cheated and exploited and believe that they must use coercive measures to both obtain what they deserve and punish wrongdoers (Dodge, 1980, 1986; Dodge et al., 1990; Slaby & Guerra, 1988).2 They are hypersensitive to disrespect and consider a strong response to such events to be imperative. To let transgressions go unchallenged, even small ones, demonstrates weakness and exposes one to future predation and exploitation. Such an orientation to relationships is a major component of what Anderson (1999) has labeled the code of the street. Furthermore, persons with a hostile view of relationships regard most people as different from themselves, which blunts empathy as humans tend to show empathy and sympathy toward individuals perceived as trustworthy and similar to themselves (Berreby, 2005, de Waal, 2008).

A hostile view of relationships would be expected to promote situational definitions leading to aggression, intimidation, and exploitation of others. Consistent with this idea, research has shown that this view of relationships is strongly held by aggressive children and adolescents (Burks et al., 1999; Dodge et al., 1990, 2002; Dodge & Newman, 1981; Zelli et al., 1999). Indeed, a meta-analysis of over 100 studies reported a robust association between a hostile view of others and youth aggression (Orbio de Castro et al., 2002); moreover, antisocial adults also demonstrate this cognitive bias (Epps & Kendall, 1995; Bailey & Ostrov, 2007; Vitale et al., & Bolt, 2005). Further, there is strong evidence that aggression and violence is often a response to situations where an individual feels disrespected (Anderson, 1990, 1999; Gilligan, 2001; Jacobs & Wright, 2006; Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003), and possessing a hostile view of relationships increases the likelihood that an individual will interpret an interaction as involving such an affront.

Several studies have shown that persistent exposure to harsh, emotionally distant parenting fosters a hostile view of relationships (Dodge, 1991; Dodge et al., 1990; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2001). We argue that models of relationships are learned and reinforced in a wide variety of settings besides the family. Research shows, for example, that racial discrimination foments a hostile view of relationships (Simons et al., 2003, 2006). This would be expected as victims of discrimination learn first hand that people often show prejudice and favoritism in their treatment of others. In addition to harsh parenting and discrimination, we expect that other adverse conditions that have been linked to crime also contribute to a hostile view of others. This includes persistent exposure to a deviant peer group as interaction in such settings often focuses upon the need to stand up to the members of other groups who cannot be trusted (Granic & Dishion, 2003). Furthermore, living in a neighborhood where crime and victimization are high is apt to promote a hostile, distrustful view by providing persistent examples of individuals who are deceitful and treacherous (e.g., Anderson 1999). In contrast, exposure to supportive parenting and residing in an area high in collective efficacy are likely to encourage a more positive view of people and relationships. Supportive parents show kindness and altruism and the residents of efficacious communities assist one another and make sacrifices for the common good.

IMMEDIATE GRATIFICATION (DISCOUNTING THE FUTURE)

Self-control has been the centerpiece of several theories of crime (Gottfredson & Hirschi 1990; Wilson & Herrnstein, 1985), and an enormous body of research demonstrates that self-control is an important predictor of crime (e.g., Pratt & Cullen 2000). Importantly, research also shows that individuals’ self-control is influenced by social experiences and events, such as parenting (e.g., Hay 2001), peers (Burt et al. 2006), and community characteristics (Pratt, Turner, & Piquero, 2004). Self-control involves inhibiting impulses and delaying gratification in order to obtain a later reward (e.g., Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). Although most individuals develop at least a modest ability to delay gratification, virtually everyone tends to discount distant compared to more immediately available rewards. People differ in their discounting curves, however, with some individuals showing a weak and others a strong tendency to discount future rewards and consequences (Ainslie, 2000; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989; Wilson & Herrnstein, 1985).

When individuals perceive that there is a low probability that their behavior will result in long-term benefits, they engage in steep discounting. At least seven experiments have reported that socially excluded individuals show a reduction in self control when they are lead to believe that their actions will have no impact upon future acceptance (DeWall et al., 2008). Further, a recent experiment found that exposure to information suggesting the world is unjust enhanced participants’ preferences for immediate versus larger, delayed rewards (Callan et al., 2009), and several studies have reported that fatalism regarding the future increases the acceptability of risky behavior, including crime (Brezina et al., 2010; Caldwell et al., 2006; DuRant et al., 1994; Hill et al., 1997; Ross & Hill, 2002; Wilson & Daly, 1997).

These studies indicate that patience and delayed gratification are often not practical (Hauser, 2006; Wilson, 2007). In some environments, reciprocity and fair play are uncommon and delayed rewards rarely materialize. In such contexts, steep discounting of future events and pursuing immediate rewards is a rational response to information indicating an uncertain probability of reaping delayed benefits (Callan et al., 208; Wilson, 2007; Wilson & Daly, 1997, 2006). It is adaptive for individuals living in such unpredictable, hostile environments to be opportunistic in their pursuit of rewards. In this way, we argue that delayed gratification (i.e., the exercise of self-control) will be reduced by persistent exposure to community crime, racial discrimination, and deviant peers. Inherent within these experiences is the lesson that life is unfair and unpredictable and one should take advantage of rewards whenever they become available. On the other hand, supportive parenting and collective efficacy are likely to increase delay of gratification and pursuit of long-term rewards as such experiences indicate that people are trustworthy and can be depended upon to keep their word.

In addition we propose that concern with immediate gratification is likely reinforced by a hostile view of relationships. Such a view of relationships suggests that people cannot be trusted to reciprocate or to keep their promises. Therefore, one should obtain rewards from others whenever they become available. Also, a hostile view of relationships reduces empathy and undermines concern about the impact of one’s actions on others, thereby making it easier to pursue immediate rewards without regard for the deleterious consequences for others. Other individuals are more likely to become potential marks if they are untrustworthy, you do not empathize with them, and are unconcerned with treating them fairly (Berreby, 2005; Sykes & Matza 1957). Thus a hostile view of relationships would have the consequence of reinforcing concern with immediate gratification and an opportunistic scrutiny of situations.

CYNICAL VIEW OF CONVENTIONAL NORMS

The last element in the criminological knowledge structure involves a person’s beliefs regarding society’s norms of conventional conduct. Some individuals consider social norms prohibiting sexual promiscuity, fighting, substance use, cheating on tests, and the like to be legitimate, morally compelling standards of behavior, whereas others possess a cynical, contemptuous view of these social rules. Several studies have reported that a disparaging view of conventional norms increases the probability of engaging in criminal behavior (e.g., Akers, 1998; Hirschi, 1969).

Both social control (Hirschi, 1969; Sampson & Laub, 1993) and social learning theories (Akers, 1998) argue that supportive parenting increases the chances that youth will develop a commitment to conventional norms. In addition, social learning theory (Akers, 1998) emphasizes the role of peer affiliations. Consistent with these arguments, a multitude of studies have reported that involved, supportive parenting increases commitment to conventional norms whereas affiliation with deviant peers discourages such commitment (see Akers & Sellers, 2009).

We argue that a cynical view of conventional norms is also rooted in other social circumstances. Community collective efficacy, for example, would be expected to enhance a youth’s commitment to social norms as it communicates that residents believe that conduct norms are legitimate and worthy of enforcement. When residents fail to respond to deviance, on the other hand, adolescents are apt to conclude that conduct norms are inconsequential. Similarly, events such as neighborhood crime and discrimination convey the message that conduct norms are unimportant. These incidents indicate that, instead of playing by society’s rules, people tend to simply pursue their selfish interests.

We expect that a cynical view of conduct norms is reinforced by the other two criminogenic schemas. Many persons respect authority and believe that most conventional norms enhance social order, harmony, and organization. Individuals who trust and care about others and who delay immediate gratification to obtain long-term rewards, usually see the value of honoring these conventions. We have noted, however, that in response to the lessons inherent in their everyday circumstances, some individuals perceive life as unpredictable, believe that society is comprised of selfish, untrustworthy people, and therefore judge that the wisest approach is to enjoy rewards whenever they become available. For these opportunistic persons, honoring social prohibitions regarding sex, drugs, fighting, and the like make little sense. If other people are not following society’s rules, why should they? Only a sucker would do so. Further, their hostile view of relationships contributes to a lack of trust and respect for the authority figures and social institutions that champion these social rules. Thus, we expect that persons possessing a hostile view of relationships and seeking immediate gratification will tend to hold a cynical view of society’s conduct norms.

THE CRIMINOLGENIC KNOWLEDGE STRUCTURE

We have argued that the social schemas that comprise an individual’s knowledge structure tend to be interrelated and connected as they are rooted in same set of social conditions and are mutually reinforcing. In addition, we expect that they operate as a dynamic unity. It is not any one schema that predicts an individual’s actions in a situation; rather it is the dynamic interplay of the constellation of relevant schemas that is important (Bourdieu, 1984; Swarz, 2002). A person’s collection of schemas operates in a manner analogous to the rules of grammar or the rules of a game. A person tacitly integrates the rules of grammar when formulating linguistic utterances or the rules of the game when designing a strategic move. Likewise, individuals implicitly combine the rules of social life represented by their constellation of schemas when construing situational circumstances and constructing a line of action (Bourdieu, 1984, 1990). Based upon this idea, we expect that it is the combination of the three schemas, and not simply belief in any one element, that is most important in explaining individual variation in offending. Past research has investigated the extent to which specific attitudes and beliefs predict criminal behavior, whereas our social schematic approach suggests that it is the constellation of schemas—the dynamic whole rather than the sum of the parts, that predicts crime and antisocial behavior.

Notably, the model proposes that learned knowledge structures, rather than situational factors, are the primary mechanisms that account for the causal effects of social factors on crime. The model views objective situational opportunities for crime as ubiquitous, whereas perceived opportunities for crime are largely dependent on individuals’ knowledge structures, as individuals with criminogenic knowledge structures often construe the routine situations encountered in everyday life as an occasion for some antisocial act. 3 Although there are situations that virtually compel criminal behavior (e.g., rival gang invades your turf, a companion pulls a knife on a shopkeeper), we argue that for the most part individuals with a criminogenic knowledge structure select themselves into such situations. However, it is certainly the case that individuals sometimes encounter, not by design or through any fault of their own, situations that are so provoking that they incite a violent or antisocial response regardless of a person’s knowledge structure, such as walking in on your spouse having sex with a family friend. Importantly, we argue that even in such situations it is still the case that those more strongly committed to the criminogenic knowledge structure are most likely to respond in a violent or antisocial fashion.

SEX DIFFERENCES

Throughout human history and in every culture men have displayed higher rates of aggression and antisocial behavior than women (Archer, 2004; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Steffensmeier et al., 2005). Therefore any compelling theory of crime must account for this major and persistent sex difference (Wilson & Herrnstein, 1985). Although a comprehensive discussion of the role and effects of sex or gender in the proposed theoretical model is beyond the scope of the present study, given the salience of sex4 differences, we briefly outline the basics in our approach. We expect that a portion of the association between sex and crime is explained by males being somewhat more likely than females to experience the adverse social conditions that have been linked to crime. There is some evidence, for example, that boys are more likely than girls to experience harsh parenting (Sobsey et al., 1997), criminal victimization (Stewart et al., 2006), and affiliation with deviant peers (Warr, 2002). The observed sex differences, however, are usually small, and we expect that they account for only a modest proportion of the association between sex and crime. Instead, we posit that the greater portion of the association between sex and crime is explained by evolved sex differences that influence the probability that men and women will develop the schemas that comprise the criminogenic knowledge structure.

From an evolutionary perspective, sex differences are expected wherever men and women are exposed to differing selection pressures. Throughout human history, the mother’s presence was more critical to the survival of her offspring than was that of the father (Campbell, 1999; Campbell et al., 2001). Studies in pre-industrial societies confirm that death of the mother is the single most important threat to infant survival (Voland, 1988; Hill & Hurtado, 1996). This suggests that women who were cautious and avoided risky situations would have been more likely to successfully reproduce (Campbell et al., 2001). In contrast, scholars have argued that risk-taking among males increased survival and reproductive success by vanquishing rivals, killing prey, and attracting mates (Daly & Wilson, 2001; Wilson & Daly, 1985). As a consequence of these differing environmental pressures, available evidence suggests that women have evolved a lower threshold for fear than men (Campbell et al., 2001). Scores of studies have found that girls express fear earlier than boys and that women experience fear and phobias more frequently and intensely (given the same stimulus) than men (see Campbell, 2006). Further, research shows that on average females are more cautious, are more sensitive to potential dangers, and engage in less risk-taking than males (Byrnes et al., 1999; Hersch, 1997). These findings portend sex differences regarding elements of the criminogenic knowledge structure.

First, women’s concern with safety and security reduces the probability that they will adopt a hostile view of relationships. Although women are no less likely than men to develop the perception that people cannot be trusted, their greater fear and caution is likely to deter them from embracing a tough, coercive response to perceived mistreatment. After all, aggressive encounters could result in injury. Furthermore, physically aggressive acts by females are attract more social control that that for males given that aggressive acts are inconsistent with social constructions of femininity (e.g., Messerschmidt 1993). Rather than criminalized physical aggression, research shows that females are more likely to engage in indirect or relational aggression, which is not regulated by criminal statutes (Björkqvist, Österman, & Langerspetz 1994). In addition, we expect that women are generally more likely than men to endorse conventional norms prohibiting fighting, drug use, cheating, driving fast, and the like. Given the danger associated with these behaviors, women are more apt than men to see the wisdom of rules proscribing such activities. Finally, we expect to find sex differences in self-control. Although there is no reason to believe that men and women differ in the general tendency to pursue immediate rewards in response to environments that fail to reward delayed gratification, women appear to be more cautious than men regarding the instantaneous reinforcement associated with risky or dangerous activities (Burton et al., 1998; Keane et al., 1993; LaGrange & Silverman, 1999; Nakhaie et al., 2000; Tittle et al., 2003).

PROPOSED MODEL

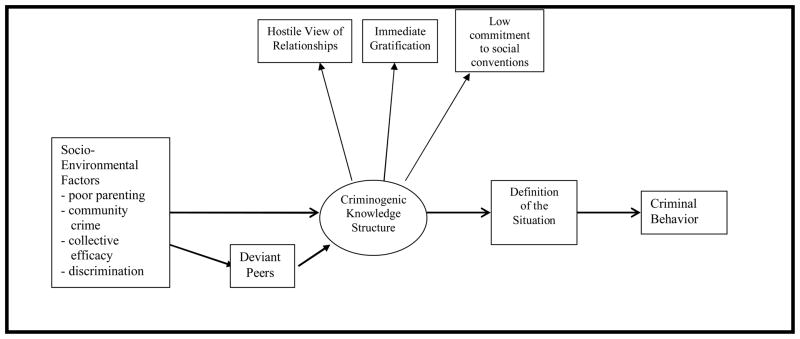

Figure 1 presents a general model summarizing our theoretical arguments. The model suggests that the various social environmental conditions emphasized in many dominant criminological theories influence risk for crime because they influence development of three social schemas: a hostile view of relationships, focus upon immediate rewards, and low commitment to conduct norms. These cognitive schemas, in turn, increase the probability that an individual will define situations in a manner that legitimates, justifies, or requires criminal behavior. These definitions might involve, for example, a perceived threat, slight, or injustice that requires a forceful reaction. Or, they might entail discerned opportunities for a quick reward or an immediate benefit by engaging in behavior that flouts convention or exploits others.

Figure 1.

A Social Schematic Model of Crime.

Turning to specific predictions derived from this model, we have argued that the three criminogenic schemas are rooted in similar social conditions and that they are mutually reinforcing. Thus, our first hypothesis is that the three schemas will be intercorrelated and will load as indicators of a latent construct that we call a criminogenic knowledge structure. The model suggests that this criminogenic knowledge structure increases the likelihood of crime because it promotes situational definitions favorable to such lines of action. Unfortunately, our data set does not include assessments of situational definitions. Therefore, we can only assess the extent to which this knowledge structure predicts an increase in criminal behavior, with the assumption that situational definitions account for this effect.

The left side of our theoretical model includes the social causes of crime: supportive parenting, collective efficacy, neighborhood crime, racial discrimination, and deviant peers. Perhaps the strongest association in criminology is that between affiliation with deviant peers and involvement in criminal behavior (Warr, 2002). Hence this variable is a component of most criminological theories. Social learning theories, for example, assert that parenting (Akers, 1998; Patterson et al., 1992) and social disorganization theories argue that collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 2002) deters association with deviant peers in addition to directly discouraging involvement in crime. Similarly, strain theories argue that exposure to high crime neighborhoods and racial discrimination (Agnew, 2006; Cloward & Ohlin, 1960) increase affiliation with delinquent peers as well as involvement in crime. In line with these theories and depicted in Figure 1, we contend that supportive parenting, collective efficacy, community crime, and racial discrimination affect criminal propensity in part by influencing affiliation with deviant peers. We depart from these theories, however, regarding the nature of the effect of these variables on crime. We contend that the criminogenic knowledge structure is the individual-level mechanism that explains the effects of social factors on individual offending. Thus, we hypothesize that the criminogenic knowledge structure mediates the effect of all of these variables, including affiliation with deviant peers, on criminal behavior.

Finally, we have no reason to believe that there will be sex differences in the structural associations posited between the various constructs, although males may exhibit greater exposure than females to some adverse social environments. We do expect, however, that sex will be related to the criminogenic knowledge structure which, in turn, will mediate much, if not all, of the association between sex and crime.

METHODS

SAMPLE

Our research utilizes the first four waves of the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), a multi-site (Georgia and Iowa) investigation of neighborhood and family processes that contribute to African American children’s development in families living in a wide variety of community settings (see Gibbons et al., 2004; Simons et al., 2002). Sample members were recruited from neighborhoods, defined as census tracts, that varied on demographic characteristics, specifically racial composition (i.e., percent black) and economic level (i.e., percent of families with children living below the poverty line). In Georgia, families were selected from 36 census tracts from metropolitan areas such as South Atlanta, East Atlanta, Southeast Atlanta, and Athens, that varied in terms of economic status and ethnic composition. In Iowa, the 35 census tracts that met the study criteria were located in two metropolitan communities: Waterloo and Des Moines. In both research sites, families were drawn randomly from rosters and contacted to determine their interest in participation.

The first wave of the FACHS data were collected in 1997 from 897 African American, fifth-grade children (417 boys and 480 girls; 475 from Iowa and 422 from Georgia), their primary caregiver, and a secondary caregiver when one was present in the home. Primary caregivers’ mean age was 37 (range 23 to 80 years), 93% were female, 84% were the target’s biological mothers, and 44% identified themselves as single parents. Their educational backgrounds were diverse, ranging from less than a high school diploma (19%) to a bachelor’s or advanced degree (9%).

The second, third, and fourth waves of data, which we use for our research, were conducted in 1999–2000, 2001–2002, and 2004–2005 to capture information when the target children were ages 12–13, 14–15, and 17–18, respectively. We focus on the latter three waves of data given that this is a period for escalating rates of delinquency and police contact (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Moffitt, 1997; Sampson & Laub, 1993). Of the 897 families, 779 remained in the panel at Wave 2; 767 were interviewed at Wave 3; and 714 were retained at Wave 4 (80% of the original sample).

Analyses comparing those families that did not participate in waves 2 or 3 did not differ significantly from those that participated with regard to youths’ age, sex, or participation in delinquency or primary caregivers’ education, household income, or neighborhood characteristics. Respondents who dropped out after the third wave, however, differed in a few ways from those in the first 3 waves. A higher percentage of those interviewed at wave 4 were female, and, not surprisingly, engaged in slightly less delinquency (diff = −.51, t =−1.97) on average than those not re-interviewed at Wave 4. A greater proportion of the families that did not participate at wave 4 had lower household incomes on average than those in the sample. No differences between those remaining in the panel and those dropping out with regard to community measures, family structure, or parenting practices.

Seven hundred fourteen members of the original sample of children and their caregivers were interviewed at wave 4. Given the sampling design, these subjects represent a sample of Black youth from the two research sites that come from extremely poor to middle class families and who reside in neighborhoods that exhibit significant variability in economic status, racial composition, and other factors, sampling features that are well-suited for studying neighborhood effects (Jencks & Mayer, 1990).

MEASURES

Our analyses primarily utilize measures from waves 3 and 4, although controls for prior delinquency and social schemas are drawn from waves 1 and 2. We use multiple informants in instances where youths may have limited and/or biased information, such as parenting practices and neighborhood social ties (Furman et al., 1989; Simons et al., 1994). In these instances, we combine caregiver and youth reports. This multi-method approach was assumed to provide a more comprehensive and valid depiction of parental behavior than measures based only on a single respondent.

We have argued that persistent exposure to various environments influences individuals offending through the lessons inherent in social experiences which are internalized or saved as cognitive schemas. Obviously this implies that exposure to various environments is causally prior to the development of the schemas, which in turn, influences later crime. For several reasons, we model these processes at waves 3 and 4, rather than measuring one step at each wave. First, we are examining youth across developmental stages (late childhood through early adulthood) in which arguably the greatest changes in life circumstances occur. Both the respondents’ experiences in social situations as well as the individuals’ themselves are quite different when they are 10–12 to when they are 17–20. Most importantly, our analyses are organized by our proposition that it is persistent exposure to social contexts, rather than exposure at one time point, that influences the content of schema, as well as our contention that more recent exposure to antagonistic or supportive environments should have a stronger influence on current schemas than those that occurred many years prior. For these reasons, we utilize the average wave 3 and 4 measures of the social contexts to predict the social schemas and crime measured at wave 4.5 Importantly, we examine the veracity of our causal order arguments by testing the effects of changes in the environments from waves 2 through 4 on changes in the schemas.6

DEPENDENT VARIABLE:CRIME

This construct was measured using youth self-reports on the conduct disorder section of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version 4 (DISC-IV). The DISC-IV corresponds to symptoms listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The DISC was developed over a 15-year period of research on thousands of youths and parents and has demonstrated reliability and validity (Schaffer et al., 1993). The conduct disorder section contains a series of questions regarding how often during the preceding year the respondent engaged in 26 antisocial acts such as shoplifting, physical assault, setting fires, vandalism, burglary, and robbery. The maximum possible score of 26 corresponds to a subject responding that he or she engaged in all of the different acts. Not surprisingly, no respondent reported engaging in all 26 acts in any wave. The maximum score was 21 at wave 4. Coefficient alpha for the instrument was above .90. The control for previous delinquency was measured with the instrument averaged across waves 1 and 2. The maximum scores were 15 and 19 in the first two waves, respectively. Coefficient alpha was above .89 in both waves.

DEVIANT SCHEMAS

Hostile View of Relationships

A hostile view of relationships consists of two dimensions: a cynical view of others’ intentions and belief in the need for an aggressive attitude to avoid exploitation. The measure was generated combining two scales which capture each dimension and load on separate factors. The first was comprised of 16 items which assess respondents’ hostile view of others intentions, and includes, for example, the following items: “When people are friendly, they usually want something from you”; “Some people oppose you for no good reason”; “You have often been lied to.” The response format ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Coefficient alpha for the scales were .81 and .88 at waves 2 and 4, respectively. A five item scale was used to assess the extent to which respondents believe that a tough, aggressive response to others is necessary and functional, analogous to Anderson’s depiction of the street code. Respondents indicated how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: “People do not respect a person who is afraid to fight for his/her rights”; “People tend to respect a person who is tough and aggressive”; “Being viewed as tough and aggressive is important for gaining respect”; “It is important not to back down from a fight or challenge because people will not respect you”; and “It is important to show courage and heart and not be a coward in a fight in order to gain or maintain respect”. Response categories ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Coefficient alpha for the mean scale was .78. Only the first two of the five items were available in the wave 2 instrument. Thus, the wave 2 measure of reputation for toughness was the mean of those two items (α =.57). The two dimensions were standardized and averaged to create the measure of hostile view utilized in the analyses. Coefficient alpha was .83 at wave 4 and .73 at wave 2.

Immediate Gratification (discounting the future)

This construct was assessed with 13 items and captures respondent’s propensity to discount the future in choosing courses of action. These items were gleaned from Kendall and Wilcox’s (1979) good self-control (1 item: “When you have to wait in line you do it patiently”) and poor self-control scales (6 items, e.g., “You would rather have a small gift today than a large gift tomorrow”; “You have to have everything right away”) as well as Eysenck and Eysenck’s (1977) risk-taking scale (6 items, e.g., “You enjoy taking risks”; “You would do almost anything for a dare”). The resulting mean scale captures the extent to which the youth focus upon immediate rather than delayed gratification. Coefficient alpha was .75 and .76 for waves 2 and 4, respectively.

Low Commitment to Social Conventions

This measure includes youth responses questions about how wrong they believe it is for someone their age to engage in various deviant actions. The instrument included acts such as using marijuana, having casual sex, and cheating on a test. The response format for each item was: 1) not at all wrong, 2) a little bit wrong, 3) fairly wrong, and 4) very wrong. The items were reverse coded prior to creating the mean scale such that the maximum score corresponds to a response of “not at all wrong” for all six items. Only two respondents scored the maximum. Although one hundred ninety-five individuals (27%) indicated that all of the deviant acts were “very wrong,” considerable variation in scores were observed across the sample (α =.78).

This instrument was not incorporated in the wave 2 interview schedule, but an analogous norms scale was available. In the second wave, the youths completed a four-item scale that asked how they feel about kids their age having sex, smoking, drinking, or using drugs. The response format for these items was as follows: 1) You think it is very bad, 2) You think it is bad; 3) You think it is neither bad nor good, 4) You think it is good, 5) You think it is very good. Items were standardized and then averaged to create a mean scale of deviant norms at wave 2 (α = .77).

SOCIAL ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS

Supportive Parenting

The instruments used in creating the quality of parenting measure were adapted from instruments developed for the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP; Conger & Elder, 1994). These measures have demonstrated high reliability and validity. Prior to data collection, focus groups confirmed that the items resonate with African American parents and capture what they consider to be the important dimensions of effective parenting. Both caregivers and youths completed instruments assessing problem-solving and inductive reasoning, and youth answered three additional scales concerning parental warmth, hostility, and positive reinforcement. Respondents were asked about parenting “during the past 12 months”; response categories the items were as follows: 1) never, 2) sometimes, 3) often, and 4) always. Responses were coded such that higher scores correspond to superior parenting. In both waves, a composite supportive parenting measure was created by standardizing and averaging the scales. These two scales (r =.43) were then averaged to create the measure of supportive parenting used in the study analyses.

At each wave target youths answered 9-items concerning parenting warmth.7 Coefficient alpha for the 9-item scale was .89 and .91 at waves 3 and 4, respectively. Parental hostility was measured with 14 items that assess the frequency with which caregivers engage in harsh discipline or otherwise hostile behaviors towards the target youth. These items were recoded such that a high score indicates an absence of caregiver hostility (α = .83 and .85). Targets reported on their caregiver’s positive reinforcement; coefficient alpha for this two-item scale was approximately .57. Caregiver problem-solving was assessed with three items. Alpha coefficients were roughly .58 for both respondents in both waves. Finally, caregiver’s inductive reasoning, the extent to which caregivers provide explanations for the decisions they make regarding their children, was measured with respondents’ answers to five items. Coefficient alpha was .86 for youths and .84 for the primary caregivers. The reliability coefficient for the six scales at wave 3 was .73 and .66 for the three scales at wave 4. The correlation between the wave 3 and 4 scales was .43, and the reliability coefficient was .60.

Discrimination

At waves 3 and 4, the target youth completed 13 items from the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff 1996). This instrument has strong psychometric properties and has been used extensively in studies of African Americans (e.g., Simons et al. 2006). The items assess the frequency (1=never, 4=several times) with which various discriminatory events were experienced over the past year. The scale asks about events that occurred as a consequence of being African American and includes items such as racial slurs, being hassled by the police, disrespectful treatment by sales clerks, false accusations by authority figures, and exclusion from social activities. Coefficient alpha for this scale was .90 and .91 at waves 3 and 4, respectively. The two scales (r =.50) were summed and averaged to create a composite measure of discrimination.

Community Crime and Victimization

This composite measure was equally based on two scales: community crime and victimization in the community. The measure of crime was assessed with a revised version of the community deviance scale developed for the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN; Sampson et al., 1997). The 9-item measure is concerned with how often various criminal acts occur within the community. It includes behaviors such as fighting with weapons, robbery, gang violence, and sexual assault. In wave 3, primary caregivers and target children completed these items in reference to their residential neighborhood. At wave 4, since almost half of the youth lived apart from their caregivers at least part of the year, only target reports were utilized. Coefficient alpha for the target and PC reports were above .80 at wave 3; the correlation between the target and caregiver reports was approximately .35. Coefficient alpha for the target reports at wave 4 was .88.

The measure of criminal victimization was based on target youth responses to two items. These items assessed the number of times that someone in “the neighborhood surrounding where you lived for most of the past 12 months used violence, such as in a mugging, fight, or sexual assault against you?” and “against one of your friends.” Responses ranged from 0 (94% and 91%, respectively) to 8 (3%) and 12 (2%), respectfully. Alpha for 2-items composite scale was approximately .78 in both waves. Finally, the measures were combined averaged from waves 3 and 4 two create the measures utilized in the model. The correlation between the measures at waves 3 and 4 was .23.

Community Collective Efficacy

Following Sampson and colleagues (1997), the measure of collective efficacy was formed by combining a social ties scale with a social control scale. Community social ties was assessed with a 9-item revised version of the Social Cohesion and Trust Scale developed for the PHDCN (Sampson et al., 1997). The items focus on the extent to which individuals in the area interact, trust, and respect each other and share values. In wave 3, youths and caregiver reports were standardized and summed to create the social ties scale. Coefficient alpha for the scale at wave 3 was above .80 for both respondents, and the correlation between youth and caregiver reports was roughly .35. The youth reports were used for the wave 4 measure; alpha reliability was .86.

The social control scale consists of 6 items (also adapted from the PHDCN, Sampson et al., 1997) that assess the extent to which individuals in the neighborhood would take action if various types of deviant behavior were evident. For example, items included: “If teenagers got loud or disorderly, the adults in the area would tell them to behave,” and “The adults in the area would not hesitate to call the authorities if a group of teens were fighting with each other.” Reliability coefficients for the 3 measures (youths at waves 3 and 4, caregivers at wave 3) were all above .85. The wave 3 and 4 scales were averaged to create a measure of persistent exposure. The correlations between the two measures was .25.

Deviant Peers

At waves 3 and 4, the target youth reported their affiliation with deviant peers using an instrument adapted from the National Youth Survey (NYS; Elliot et al. 1989). They were asked how many of their close friends (1=none, 2=half, 3=all) had engaged in each of 15 deviant acts at wave 4 (19 acts in wave 3). The acts ranged from relatively minor offenses, such as using tobacco, to more serious violations, such as stealing something worth more than $50, attacking someone with a weapon with the idea of hurting them, and using crack or cocaine. Alpha coefficient was .83 and .87 for the scales at waves 3 and 4, respectively. These two scales (r =.42) were standardized, summed, and averaged to create the measure used in the present study.

Control Variables

In all of the models we present, the sex of the respondents is controlled. The variable sex is coded 1 for males and 0 for females. In several models, where preliminary analyses support incorporating the variable, the standardized age of the respondents is entered as a control. Age is measured in months at the time of the wave 4 interview. Additional controls were considered, including household income; primary caregiver race, age, and sex; and the presence of a second caregiver in the home. None of these variables significantly influenced the processes under consideration and, thus, were not included in the models.

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test our hypotheses. SEM offers several advantages to traditional econometric analyses. This approach permits correction for bias in the estimation of substantive parameters due to measurement error. Moreover, it allows for the estimation of substantive parameters simultaneously in the context of a full-information model—a model corresponding to the causal ordering of both the theoretical arguments and the longitudinal FACHS data. Perhaps most important for the present study, SEM provides tests of significance for indirect (or mediation) effects, including specific paths (e.g., Bollen 1989).

Analyses were conducted using the statistical program MPlus Version 6.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 2010) using maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square statistic that are robust to non-normality. Noting that we adjusted for item nonresponse for respondents who were interviewed in at least waves 1, 2, and 4 and employed wave 4 measures in lieu of wave 3 and 4 averaged scales for those not interviewed at wave 3, we utilize the default of listwise deletion in estimating the models. With one exception, the study variables were generally symmetric and normally distributed. The lone exception is the dependent variable, crime, which is an overdispersed count variable, which is estimated with a negative binomial equation model accommodating the features of count outcome (Long 1997).8

To assess goodness-of-fit, Steiger’s Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck 1992), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler 1990), and the chi-square divided by its degrees of freedom (fit ratio) are used. The CFI is truncated to the range of 0 to 1, and values close to 1 indicate a very good fit (Bentler 1990). A RMSEA smaller than .05 indicates a close fit, whereas a RMSEA between .05 and .08 suggests a reasonable fit (Browne & Cudeck 1992).

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlation matrix for the study variables. The mean number of criminal acts committed by the study youths is 2.84 and ranges from 0 to 21 acts. Approximately 33% (237) of the respondents did not commit any of the acts in wave 4; roughly 43 percent (305 respondents) committed 1 to 4; 24 percent (171 youths) committed five or more. Among the respondents who committed at least one of the acts in the crime measure, almost half committed at least 4 different acts, and more than 20 percent admitted to engaging in at least 7 different acts. Clearly, sufficient involvement and individual variation in criminal offending exists in the data.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix for Study Variables (n=713).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CrimeW4 | — | 2.84 | 3.52 | ||||||||||

| 2. Deviant PeersW3+W4 | .38 ** | — | .01 | .88 | |||||||||

| 3. Immediate GratificationW4 | .28 ** | .34 ** | — | .00 | .59 | ||||||||

| 4. Hostile ViewW4 | .30 ** | .34 ** | .30 * | — | 1.58 | .59 | |||||||

| 6. Social ConventionsW4 | .33 ** | .43 ** | .30 ** | .36 ** | — | −.07 | .59 | ||||||

| 7. Community CrimeW3+W4 | .22 ** | .35 ** | .13 ** | .24 ** | .17 ** | — | −.07 | .75 | |||||

| 8. Collective EfficacyW3+W4 | −.15 ** | −.15 ** | −.13 ** | −.06 | −.16 ** | −.17 ** | — | 2.21 | .49 | ||||

| 9. Supportive ParentingW3+W4 | −.20 ** | −.39 ** | −.36 ** | −.24 * | −.34 ** | −.19 ** | .18 ** | — | −.01 | .87 | |||

| 10. DiscriminationW3+W4 | .26 ** | .34 ** | .21 ** | .23 ** | .20 ** | .20 ** | −.05 | −.12 ** | — | .51 | .29 | ||

| 11. DelinquencyW1+W2 | .27 ** | .40 ** | .20 ** | .19 ** | .28 ** | .18 ** | −.06 | −.26 ** | .25 ** | — | 2.17 | 2.40 | |

| 12. Sex (1=Male) | .13 ** | .04 | .01 | .10 * | .19 ** | .01 | .05 | .02 | .01 | .17 ** | — | .44 | .50 |

| 13. Age (standardized) | .04 | .08 * | .01 | −.03 | .05 | −.03 | −.05 | −.08 * | .16 ** | .14 ** | −.01 | .00 | 1.00 |

p ≤.05;

p ≤.001 (two-tailed)

Turning to the zero-order correlations, the pattern of associations is largely as expected. Each of the social schemas has approximately a .3 correlation with crime (p<.001) as well as associations with each other ranging from .30 to .36. As expected the social environmental variables are significantly related to the social schemas in the expected direction, with one exception. Collective efficacy is not related to hostile views.

Sex is not significantly associated with most of the study variables; however, as expected, being male is significantly related to crime, tough reputation, and low commitment to social conventions. Contrary to our expectations, however, there is no significant association between being male and immediate gratification. Further analysis showed that being male is significantly related (r averages .11) to the risk-taking items in the immediate gratification scale but not to those concerned with patience and delayed gratification.9 These results are consonant with those of prior studies showing that the relationship between sex and self-control is explained by males’ greater attraction to risk-taking than females’ (see Campbell, 2006).

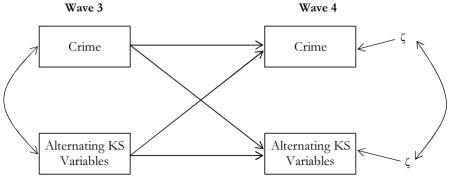

SEM RESULTS

We argued that persistent childhood and adolescent exposure to adverse social environmental conditions fosters criminogenic schemas. Thus, we began our analyses by examining the extent to which changes in social schemas from wave 2 to wave 4 (mid to late adolescence) were explained by changes in social environments. We expected that increased exposure to coercive environments (i.e., crime, discrimination) augment each of the criminogenic schemas, whereas supportive environments (i.e., parenting, collective efficacy) diminish belief in the schemas. Six SEMs were estimated, two for each social schema. In the first, change in the schemas from wave 2 to wave 4 was predicted by the change in the social environmental variables. Change in the schemas was assessed by incorporating the wave 2 schema as an exogenous predictor. In the second model for each schema, increased affiliation with deviant peers was added as an exogenous predictor in order to take into account the fact that some of a social environment’s effect may be indirect through its impact on peer associations. Table 2 presents the results.10 In general, the findings show that changes in social environments produce changes in each of the social schemas. The model fit statistics across the table indicate that the models fit the data quite well. Across the six models, the chi-square statistic is insignificant, indicating that the model fits the data well. The RMSEA statistic for all models is less than or equal to .01. The CFI statistic is 1.00 in all cases as well.

Table 2.

Results from SEMs Predicting the Change in Schemas (n =713).

| Exogenous Predictors | Immediate GratificationW4 | Hostile ViewsW4 | Social ConventionsW4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| γ | γ | γ | γ | γ | γ | |

| Outcome VariableW2 | .40 ** | .42 ** | .30 ** | .30 ** | .20 ** | .18 ** |

| Community CrimeW4-W2 | .01 | .01 | .18 ** | .17 ** | .17 ** | .15 ** |

| Collective Efficacy W4-W2 | −.06 † | −.05 | −.02 | −.01 | −.08 * | −.08 * |

| Supportive Parenting W4-W2 | −.16 ** | −.12 ** | −.10 ** | −.09 ** | −.12 ** | −.09 ** |

| Discrimination W4-W2 | .19 ** | .15 ** | .18 ** | .17 ** | .08 ** | .05 |

| Sex (1=Male) | − | − | .06 † | .06 † | .19 | .19 † |

| Age | − | − | −.06 † | −.06 | .06 | .07 † |

| Deviant PeersW4-W2 | .15 ** | .04 | .15 ** | |||

| R 2 | .22 | .24 | .17 | .17 | .16 | .20 |

| χ2(df) | 9.04(12) | 9.11(14) | 4.95(9) | 6.25(11) | 5.23(8) | 11.35(13) |

| RMSEA/CFI | .00/1.00 | .00/1.00 | .00/1.00 | .00/1.00 | .00/1.00 | .00/1.00 |

NOTE: Reduced models presented; standardized coefficients shown.

p <.01;

p <.05;

p <.08 (two-tailed).

Turning to the parameter estimates in Table 2, immediate gratification shows the most stability across the models (γ = .40), followed by hostile view (γ= .30), and social conventions (γ=.20). Increased exposure to community crime and victimization is associated with significant increases in hostile view and lower commitment to social conventions, with and without changes in deviant peers in the model. Community collective efficacy is associated with a significant decrease in low commitment to social conventions (γ= −.08) and a marginally significant decrease in immediate gratification (γ= −.06). The influence of collective efficacy on these two schemas is only slightly altered by the inclusion of deviant peers, suggesting that its influence is not indirect through deviant peer affiliation. Supportive parenting significantly decreases each of the schemas, with the strongest effects on immediate gratification; path coefficients ranged from -.12 to -.16 (p<.001). Experiences with discrimination produce statistically and substantively significant changes in all of the schemas, with the strongest effects on immediate gratification and hostile views. As can be seen comparing the first and second models for each schema, some of the effects of changes in the contexts are indirect through changes in deviant peer affiliations, which are significantly related to changes in immediate gratification and social conventions. Sex is not associated with changes in immediate gratification, but being male is significantly associated with increased rejection of social conventions (γ = .23). Finally, being older is associated with lower hostile views and increased rejection of social conventions, but these coefficients are only marginally significant.

Overall, the changes in the social schemas produced by changes in to social environmental conditions are largely consistent with our arguments. Approximately 20% of the variance in immediate gratification, hostile views, and commitment to social conventions is explained in the models. Even with the relative stability of both the schemas and the contexts, changes in exposure to deleterious and supportive conditions alter social schemas.

We have argued that the three schemas are interrelated, mutually reinforcing cognitive frameworks that combine to form knowledge structure which influences crime through definitions of the situation. This argument implies that the schemas should come together as a higher-order latent construct. We estimated a confirmatory factor analysis to test this idea. Following convention, we set the metric for the latent construct by fixing the factor loading of immediate gratification to 1. Multiple group analyses indicated that the factor loadings were invariant by sex.11 Though not a definitive test, the results of the CFA provide support for our argument. The factor loadings are .61 for immediate gratification, .68 for hostile views, and .66 for social conventions, suggesting that these constructs combine to comprise a latent construct.

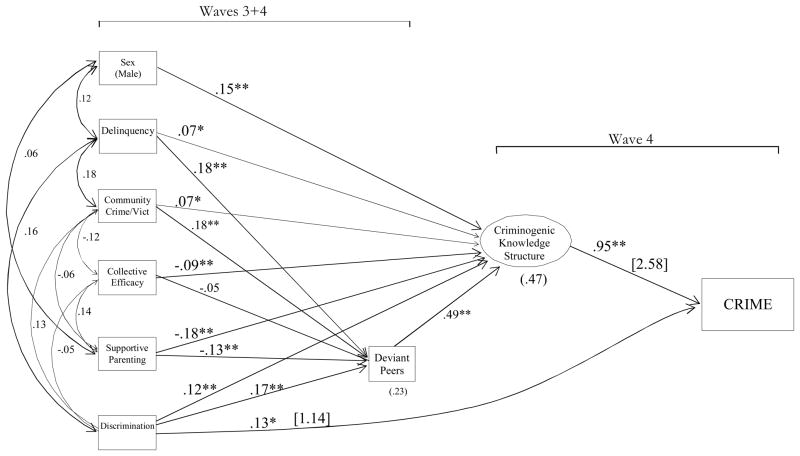

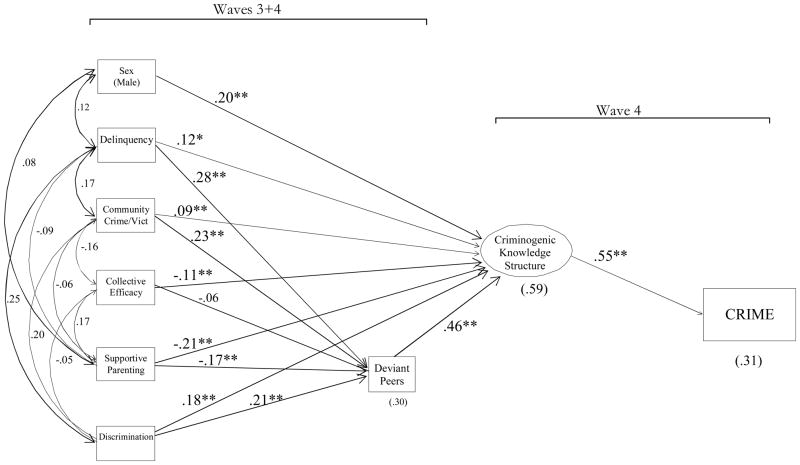

Next, we estimated a structural model to test the central feature of our proposed theoretical model that this latent knowledge structure construct is associated with crime (i.e., it is criminogenic) and that it mediates much of the effects of social environments on crime. First, we estimated a model that included all possible pathways between the constructs. Following the initial estimation of the model, nonsignificant paths (t <1.5), which were not part of the hypothesized model, and residual correlations were eliminated to improve model fit. All direct paths between the ecological contexts and crime and the direct path from earlier delinquency to the outcome were removed in this step, as all had t-values less than 1.5, excepting discrimination which continued to have a direct effect. Figure 2 displays the results of the reduced model for the total sample. Although model fit indices are not available for the count model, the model fit indices for the continuous model presented in Appendix A indicate a good fit of the model to the data.12

Figure 2. Reduced Structural Equation Model (n =713).

Negative Binomial Model estimator predicting crime.

Notes:Standardized values displayed; age controlled but only related to exogenous constructs and thus not shown for clarity. R2 in parentheses below endogenous constructs. Event rate ratio from NB model in brackets.

Appendix A.

Reduced Continuous SEM (n =713).

Notes: Standardized values displayed; age controlled but only related to exogenous constructs and thus not shown for clarity. R2 in parentheses below endogenous constructs.

Model fit indices: χ2(df) =63.36(36) p=.003; CFI = .97; TLI = .97; RMSEA =.03.

The results in Figure 2 show that the social environmental factors influence the latent knowledge structure variable as predicted.13 Community crime and discrimination have positive effects on the criminogenic schema of .07 and .12, respectively. Supportive parenting and collective efficacy, on the other hand, are negatively associated with this knowledge structure (γ = −.18 and γ = −.09, respectively). Moreover, these social environmental variables, with the exception of collective efficacy, which does not appear to influence deviant peer affiliations, are significantly related to deviant peers in the same manner. That is, community crime and discrimination are associated with an increase whereas quality of parenting is associated with a decrease in affiliation with deviant peers. Deviant peers, in turn, shows a strong association with knowledge structure (γ = .49). This pattern of findings is consistent with our argument that affiliation with deviant peers fosters a criminogenic knowledge structure and that, in addition to their direct effects, the other social environmental variables influence this knowledge structure indirectly through their impact on affiliation with deviant peers. The first half of Table 3 displays the total effects of the social environmental variables on the knowledge structure as well as the specific indirect paths through deviant peers. Delta method standard errors for significance testing of the indirect effects were computed in Mplus.14,15 Finally, as shown in Figure 2, the effect of deviant peers on crime is completely mediated by the knowledge structure.16

Table 3.

Indirect Effects

| Predictors | Criminogenic Knowledge Structure

|

Crime

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Peers to CKSa | Total Indirect | CKS to Crimeb | Peers to CKS to Crimec | |

| DelinquencyW1+W2 | .248 *** | .128 *** | .135 *** | .065 ** | .070 *** |

| Community CrimeW3+W4 | .193 *** | .106 *** | .105 *** | .047 * | .058 *** |

| Collective EfficacyW3+W4 | −.130 *** | −.026 | −.071 ** | −.057 ** | −.014 |

| Supporitive ParentingW3+W4 | −.288 *** | −.080 *** | −.157 *** | −.114 *** | −.043 *** |

| DiscriminationW3+W4 | .276 *** | .099 *** | .150 *** | .097 *** | .054 *** |

| Deviant PeersW3+W4 | .252 *** | .252 *** | |||

| Sex (1=Male) | .106 *** | .106 *** | |||

p <.001;

p <.01;

p <.05

Notes: These indirect effects were calculated from a continous SEM using delta method standard errors.

This column displays the effects of each predictor to peers to the CKS (criminogenic knowledge structure).

This column displays the effects of each predictor to CKS to crime.

This column displays the effects of each predictor from the path through deviant peers to CKS to crime.

Among the controls for sex and prior delinquency, both being male and prior delinquency are positively related to the criminogenic knowledge structure directly (.15 and .07, p<.001, respectively) and to deviant peers. Importantly, both of these variables are fully mediated by knowledge structure. In other words, sex/gender influences on crime are explained by the criminogenic knowledge structure; likewise with previous delinquency.17

Finally, the path between knowledge structure and delinquency is significant and large (β=.95, p<.001). A standard deviation increase in the knowledge structure increases the expected count of crime by 159% (calculated as follows [100 × (eβ−1)]). Moreover, the latent knowledge structure construct fully mediates all of the other predictors in the model with the exception of racial discrimination. Discrimination has a significant direct effect on crime (γ=.13) in addition to its larger indirect effect through knowledge structure. Forty-seven percent of the variance in knowledge structure is explained by the ecological contexts, sex, previous delinquency, and deviant peer affiliation, and the continuous model explains 31% of the variance in crime.18

The right side of Table 3 displays the indirect effects of the social environmental factors on crime along with their significance. All of the social environmental variables have significant (p<.001) indirect effects on crime. The standardized indirect effects range from an absolute value high of .252 for deviant peers and −.157 for quality of parenting to −.071 for collective efficacy. Turning to specific paths, the two ways the social environmental factors can influence crime is through criminogenic knowledge structure to crime or through deviant peers to criminogenic knowledge structure to crime. All of the indirect effects through these two pathways are significant, excepting collective efficacy through peers.

Although not part of our hypotheses, it is worth noting that prior delinquency does not have a direct influence on later crime; its effect is indirect through deviant peers and criminogenic knowledge structure. As shown in Table 3, both of these indirect effects are significant. This finding indicates that the stability of antisocial behavior over time is explained by the fact that early involvement enhances commitment to a criminogenic knowledge structure both directly and indirectly by increasing affiliation with deviant peers. The effect of sex on crime is also fully mediated by the knowledge structure. The indirect effects, shown at the bottom of Table 3, are significant and positive, suggesting that sex differences in crime are accounted for by the criminogenic knowledge structure.

DISCUSSION

Criminal offenders, like conforming individuals, tend to view their actions as legitimate and acceptable given prevailing circumstances (Katz, 1988; Baumeister, 1997; Giordano et al. 2002). The motives for criminal acts usually involve elements of revenge, teaching someone a lesson, impressing peers or bystanders, or the opportunistic pursuit of material rewards (Black, 1998; Katz, 1988). There is usually little empathy or concern for the fair treatment of those negatively affected by these acts. We posited that these perceptions and behaviors are fostered by the combination of three schemas: a hostile view of relationships, a focus upon immediate rewards, and low commitment to conventional conduct norms.

We argued that this cognitive framework, which shapes situational definitions and resulting actions, develops in response to adverse social environmental conditions that past research has linked to crime. Social environments that have been shown to encourage crime (e.g., neighborhood crime, discrimination) tend to be unpredictable, exploitive, and low on trust, reciprocity and support, whereas those that have been shown to discourage crime (e.g., authoritative parenting, collective efficacy) tend to be predictable, supportive, and high on trust and reciprocity. The two types of milieus teach very different lessons regarding the nature of relationships, the value of delayed gratification, and the authority of social conventions. Consequently, persistent exposure to such antagonistic social circumstances and lack of exposure to these positive conditions increases the chances of developing social schemas involving a hostile view of relationships, a focus upon immediate rewards, and cynicism regarding conventional conduct norms.

We posited that these three elements represent an interconnected set of learned, mutually reinforcing principles that combine to form a knowledge structure conducive to crime. We hypothesized that this cognitive structure fosters situational definitions that lead to actions that are aggressive, opportunistic, and sometimes criminal. Finally, we argued that females, given their greater fear and caution, would be less likely than males to develop criminogenic knowledge structures, and that this difference largely accounts for sex differences in criminal behavior.

Our findings provided preliminary support for this perspective. First, social environmental factors emphasized by other criminological theories were found to predict changes in the three schemas. Specifically, community crime, deviant peers, and discrimination increased whereas collective efficacy and supportive parenting decreased belief in the schemas. Second, as predicted, the schemas were intercorrelated and combined to form a latent construct. Consistent with the contention that this construct represented a criminogenic knowledge structure, it was a strong predictor of change in crime. Further, our findings indicated that in large measure the effect of the various social environmental conditions on offending is indirect through the criminogenic knowledge structure. With one exception, to be discussed below, the effect of these adverse conditions on change in crime was completely mediated by the latent variable criminogenic knowledge structure. Finally, we found that controlling for criminogenic knowledge structure eliminated the association between sex/gender and crime. Our results indicated that this effect is largely a consequence of males being more committed to a hostile view of relationships and less committed to social conventions than females.

In contrast to the effects of the other social factors, whose effects on crime were fully explained by the criminogenic knowledge structure, racial discrimination had a direct effect in addition to its indirect effect. While this was not expected, this finding is not inexplicable. First, unlike the other examined social factors, racial discrimination is experienced exclusively by racial-minorities. Thus, it may be the case that racial discrimination affects socially behaviors such as crime through racially-specific factors. Scholars have argued the unique position of African Americans shapes the development of a distinctive worldview (e.g., Unnever & Gabbinon 2010). Thus, it is possible that unique racial schemas or factors are needed to fully explicate the link between race and racism and offending. It may also be the case ethnic-racial factors condition the influence of racial discrimination on cognitions and behavior. For example, recent research has highlighted the importance of ethnic-racial socialization—a class of protective practices utilized to promote minority children’s pride and esteem in their racial group and to provide children with competencies to deal with racial stratification—in explaining variations in responses to racial discrimination (Neblett Jr. et al., 2008). Research indicates that that ethnic-racial socialization influences adolescents’ criminal responses to discrimination (Burt 2009). Thus, while the majority of the effects of racial discrimination are indirect through individuals’ knowledge structures, the remaining effect on offending might be accounted for by various race- or ethnic-specific processes or mechanisms that affect situational definitions and thus in situ behavior.

Alternatively, it might also be the case that a general factor accounts for the remaining direct effect of discrimination. As we noted earlier, using the example of the someone walking in on his/her spouse in coitus with a family friend, there are some situational factors which might compel criminal behavior net of individuals’ criminogenic knowledge structures. In some circumstances, racial discrimination might be so frustrating, anger-provoking, or even maddening that it could foster an antisocial reaction regardless of the victim’s knowledge structure. A particularly severe experience with discrimination could be the precipitating factor, or it could be a triggering event that is no more injurious than those that have come before but served as the last straw. While further research is needed to explicate the direct effect of racial discrimination, the above explanations are not inconsistent with the proposed model.

Although our findings largely confirmed the study hypotheses and provided preliminary support for our theoretical arguments, our study is not without limitations. Perhaps most importantly, due to the absence of measures, we were unable to test the idea that situational definitions mediate the relationship between criminogenic knowledge structure and perpetration of criminal behavior. Additionally, the relative length of the intervals between waves, given the ages of the youth in the sample, precluded our ability to provide a rigid test of the causal order of our proposed model. Further tests are needed that subject the theorized causal sequencing to further scrutiny.

Another limitation is the homogeneity of our sample; all of the respondents in our sample were African American. Use of an all African American sample had the benefit of allowing us to incorporate racial discrimination into the model; a factor that recent research indicates is an important predictor of crime among African Americans (e.g., Simons et al. 2006; Unnever et al. 2009). Although we cannot think of any reason why our results would be specific to African Americans, our findings clearly need to be replicated with more diverse samples.

Although important elements remain to be tested, the proffered framework has the potential to integrate a wide array of extant criminological findings and constructs into a coherent theoretical perspective. It specifies a temporal linkage between social environmental factors identified by various control, strain, and cultural deviance perspectives and the development of a set of social schemas posited to foster situational definitions conducive to crime. These schemas build upon Dodge’s (1986; Dodge et al., 1990) concept of hostile attribution bias, Anderson’s (1999) research on street code, Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) work on self-control, and Akers’ (1998) and Hirschi’s (1969) emphasis upon moral beliefs and conduct norms. We argue that what unites these seemingly disparate community, family, and peer variables is the common set of lessons regarding the nature of relationships, the value of delayed gratification, and the authority of conduct norms inherent in these social interactions. These cognitive constructs were reconceptualized as interlinked schemas that operate in concert to foster situational definitions favorable to crime. The result is a broader, more comprehensive model than that achieved in most prior attempts at theoretical integration.

An advantage of this social schematic theory is that it can easily be expanded to accommodate additional social environments and experiences that have been shown to increase the probability of criminal behavior. Watching violent TV (Bushman & Huesmann, 2000; Huesmann et al., 2003), playing violent video games (Anderson et al., 2010; Anderson & Bushman 2001), incarceration (Laub & Sampson, 2003), and other negative social relations (Agnew, 2006), for example, have been linked to increases in offending. Our social schematic perspective would predict that in large measure these variables have their effect because they teach lessons about relationships and about how the world works, thereby promoting a hostile view of relationships, a focus upon immediate rewards, and low commitment to conventional conduct norms.

Research has also identified social factors that reduce involvement in criminal and deviant behavior. Marriage, employment, and military service, for example, have been linked to a reduction in antisocial behavior (Sampson & Laub, 1993, 2003). We expect that these factors reduce offending because they foster a benign, predictable view of social life, thereby diminishing belief in the criminogenic knowledge structure. Support for this idea comes from studies showing that individuals with a distrustful view of relationships tend to develop a more positive relationship schema after marrying a caring and supportive individual (Hazan & Hutt, 1990). Similarly, affiliation with conventional peers increases self-control (Burt et al., 2006) while improved parenting has been linked both to increased self-control (Burt et al., 2006; Hay & Forrest, 2006) and decreased commitment to a hostile view of relationships (Simons et al., 2006). Such findings highlight the malleability of social schemas and point to various pro-social interventions to reduce offending by changing cognitive structures. Indeed, there is already evidence supporting the efficacy of this approach. Several studies, for example, have show that it is possible to enhance sensitivity to others and delayed gratification (e.g., Reid et al. 2005; Strayhorn 2002). And, at least five intervention experiments have shown that a hostile view of relationships can be altered and that this change decreases deviant, aggressive behavior (see Dodge, 2006).