Abstract

Sleeplessness, a universal condition with diverse causes, may be increasingly diagnosed and treated (or medicalized) as insomnia. We examined the trend in sleeplessness complaints, diagnoses, and prescriptions of sedative hypnotics in physician office visits from 1993 to 2007. Consistent with the medicalization hypothesis, sleeplessness complaints and insomnia diagnoses increased over time and were far outpaced by prescriptions for sedative hypnotics. Insomnia may be a public health concern, but potential overtreatment with marginally effective, expensive medications with nontrivial side effects raises definite population health concerns.

The occasional inability to sleep, or sleeplessness, is part of the universal human experience and has been recorded by ancient and modern authors.1–4 Recently, however, sleeplessness has been characterized as an epidemic5 and an unmet public health problem.6 Insomnia diagnoses in the United States, which appear to be increasing, are associated with poor health outcomes and may cost $100 billion annually in health services, accidents, and lost productivity.7–9

It is unclear, however, if the United States is facing a true insomnia epidemic or a surplus of diagnoses and drug prescriptions.10 Sleep patterns are influenced by changing cultural norms, shifting demographics (adults ≥ 65 years are more likely to be sleepless11), and increased use of technology.6,12,13 Awareness raised by public health and pharmaceutical agencies may facilitate new diagnoses.14,15 Medicalization may also contribute to the increased perception, diagnosis, and treatment of sleeplessness as the medical condition insomnia.3

Medicalization is the process by which formerly normal biological processes or behaviors come to be described, accepted, or treated as medical problems.16 The process is value neutral, but outcomes affect individual and public health.16 Medicalization may raise awareness about and improve access to beneficial medical treatments for previously underrecognized disorders.17 Conversely, it may reframe and transform ideas of physical and emotional normalcy prompting the overuse of potentially harmful drugs or surgery.18,19 Excessive or inappropriate use of medical solutions to treat life problems may negatively affect public health.10,17–19

We explored the idea that the US epidemic of insomnia may be, in part, facilitated by medicalization. Explorations of medicalization are typically qualitative and focus on the conceptual nature of the disorder.17 Sleep is no exception.20–23 Our research is the first to our knowledge to focus on the measurable outcomes of the patient–physician interaction surrounding sleeplessness and the public health implications.

Using nationally representative office visit data we measured trends over time in (1) complaints of sleeplessness, (2) diagnoses of insomnia, and (3) prescriptions of sedative hypnotics. Medicalization theory predicts an increasing incidence of insomnia diagnoses and treatments over time that outpace sleeplessness complaints, particularly among younger adults.

METHODS

We used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an annual population-based, nationally representative survey of US office-based physician visits conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The NAMCS provides information on private-pay and public-sector patients using a multistage geographically clustered probability sample of approximately 3000 randomly chosen physicians per year.24

The unit of analysis was the office visit. To maintain International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9)25 code consistency for insomnia diagnosis and capture 1 year of data before the introduction of zolpidem, the first of the nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics (NBSHs), we examined data from 1993 to 2007 for adults aged 18 years and older.

Key variables included the following:

Sleeplessness as reason for office visit (complaints of “sleeplessness,” “can't sleep,” “trouble falling asleep” [NCHS code 1135.1]);

Diagnoses of insomnia (ICD-9 diagnosis codes 78052, 78050, 3074, 78059, 30742, 3074, 30748, 78056, 78055, 30741, 30742, 30749, 32700, and 32709);

Prescription of benzodiazepines (estazolam, flurazepam, quazepam, temazepam, and triazolam) or NBSHs (zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone, and ramelteon) indicated for insomnia.

We calculated means and 95% confidence intervals using SVY commands in Stata version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), which adjust for the complex weighted design of NAMCS. We calculated rates per 10 000 visits for each type of event (complaint, diagnosis, and prescription) and age group (18–44, 45–64, and ≥ 65 years) and regressed on year using a bivariate linear model. The regression coefficients (slopes) represent the average annual increase in each type of event over the 15-year observation period. Because of small cell sizes, we combined data years into 5 blocks of 3-year increments when calculating outcomes by age groups.

RESULTS

Table 1 reveals that approximately 2.7 million adult office visits involved complaints of sleeplessness in 1993. By 2007, this figure had more than doubled to 5.7 million. During the same period, insomnia diagnoses increased more than 7-fold, from about 840 000 to 6.1 million. Approximately 2.5 million office visits in 1993 resulted in a prescription for a benzodiazepine, compared with 3.7 million in 2007. Prescriptions for NBSHs increased about 30-fold from 1994 (540 000 prescriptions) to 2007 (16.2 million).

TABLE 1.

National Estimates of Sleeplessness-Related Complaints, Diagnoses, and Prescriptions for Benzodiazepine and Nonbenzodiazepine Sedative Hypnotics as a Result of Physician Office Visits: United States, 1993–2007

| Year | Total Visits (Total Weighted Estimates), in Millions | Sleeplessness Complaints, Estimated No. (95% CI), in Millions | Insomnia Diagnoses, Estimated No. (95% CI), in Millions | BDZ Prescriptions, Estimated No. (95% CI), in Millions | NBSH Prescriptions, Estimated No. (95% CI), in Millions |

| 1993 | 35 978 (717.2) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.3) | 2.5 (1.7, 3.4) | —a |

| 1994 | 33 598 (681.5) | 2.9 (1.9, 3.9) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.6) | 0.54 (0.3, 0.8) |

| 1995 | 36 875 (697.1) | 2.8 (2.0, 3.7) | 1.4 (0.9, 1.9) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) |

| 1996 | 29 805 (734.5) | 3.2 (2.4, 4.0) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.2) | 1.9 (0.8, 3.0) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.3) |

| 1997 | 24 715 (787.4) | 3.8 (2.7, 4.8) | 2.3 (1.2, 3.4) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.3) | 2.1 (1.4, 2.7) |

| 1998 | 23 339 (829.3) | 3.7 (2.6, 4.8) | 2.8 (1.5, 4.1) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.0) | 2.1 (1.4, 2.9) |

| 1999 | 20 760 (756.7) | 5.0 (3.2, 6.8) | 2.3 (1.6, 3.1) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.2) | 2.4 (1.7, 3.2) |

| 2000 | 27 369 (823.5) | 5.1 (3.8, 6.4) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.1) | 2.2 (1.1, 3.2) | 3.3 (2.2, 4.5) |

| 2001 | 24 281 (880.5) | 4.5 (3.1, 5.8) | 2.7 (1.8, 3.7) | 3.0 (2.0, 4.1) | 4.8 (3.5, 6.1) |

| 2002 | 28 738 (890.0) | 4.4 (3.2, 5.6) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.3) | 1.9 (1.2, 2.6) | 4.4 (3.3, 5.4) |

| 2003 | 25 288 (906.0) | 5.0 (3.7, 6.4) | 3.6 (2.4, 4.7) | 2.4 (1.5, 3.4) | 6.3 (5.0, 7.6) |

| 2004 | 25 286 (910.9) | 5.0 (3.7, 6.4) | 3.2 (1.9, 4.5) | 3.0 (2.1, 4.0) | 8.4 (6.3, 10.6) |

| 2005 | 25 665 (963.6) | 5.9 (4.4, 7.5) | 4.2 (2.8, 5.5) | 3.4 (2.2, 4.6) | 12.3 (9.9, 14.7) |

| 2006 | 29 392 (902.0) | 4.4 (3.3, 5.5) | 5.2 (3.7, 6.6) | 3.5 (2.5, 4.5) | 12.6 (10.5, 14.8) |

| 2007 | 32 778 (994.3) | 5.7 (4.4, 7.1) | 6.1 (4.8, 7.5) | 3.7 (2.6, 4.8) | 16.2 (13.7, 18.6) |

| Model statisticsb | |||||

| Slope, b | 203 712 | 301 178 | 113 624 | 1 029 827 | |

| Correlation, r | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.93 | |

Note. BDZ = benzodiazepine; NBSH = nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotic.

NBSHs were not separately coded in the survey until 1994.

For model statistics, b is the slope from bivariate regression of variable on year; r is the temporal correlation of variable with year.

We observed linear slopes over time for rates of sleeplessness complaints (b = 203 712), insomnia diagnoses (b = 301 178), and prescriptions for benzodiazepines (b = 113 624) and NBSHs (b = 1 029 827). Given the large sample size, all slopes were positive and statistically significant. However, the NBSH trajectory far outpaced other outcomes.

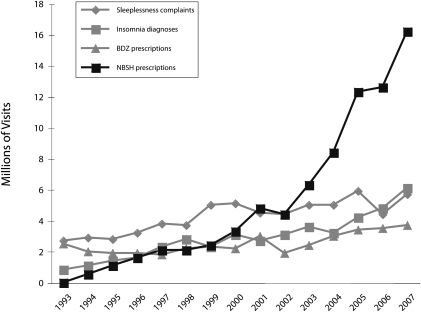

Figure 1, which illustrates Table 1 data, shows the actual time trends in the 4 variables. Complaints of sleeplessness exceeded diagnosis rates from 1993 through 2005; by 2006, however, these lines had merged. Over time, NBSH prescriptions far outpaced both complaints of sleeplessness and diagnoses of insomnia. By 2007, more than 1.6% of all office visits in the United States were generating these prescriptions. The temporal linear correlations in order by strength (0.94–0.77) were diagnoses, NBSH prescriptions, complaints, and benzodiazepines. All were strong, confirming the linear trajectories of the variables over time.

FIGURE 1.

Sleeplessness-related trends of complaint, insomnia diagnosis, benzodiazepine (BDZ) and nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotic (NBSH) prescription as a result of physician office visits: United States, 1993–2007.

By the year 2000, adults aged 65 years and older were less likely than were those aged 18 to 44 years or 45 to 64 years to list sleeplessness as the reason for an office visit or to receive an insomnia diagnosis. As seen in Table 2, from 1996 to 1998 onward those aged 65 years and older were less likely to receive an NBSH prescription than were those aged 45 to 64 years. Compared with other age groups, adults aged 65 years and older were most likely to receive a benzodiazepine prescription in all years, but, as indicated by low temporal correlations and small negative slopes, their sleeplessness complaints and benzodiazepine prescriptions did not increase steadily over time. The steepest slopes are for the NBSH prescriptions across all age groups.

TABLE 2.

National Estimates of Sleeplessness-Related Complaints, Diagnoses, and Prescriptions for Benzodiazepine and Nonbenzodiazepine Sedative Hypnotics as a Result of Physician Office Visits, by Age Group: United States, 1993–2007

| Sleeplessness as Reason for Office Visit, Complaints Per 10 000 Visits |

Insomnia Diagnoses, Per 10 000 Visits |

BDZ Prescriptions, Per 10 000 Visits |

NBSH Prescriptions, Per 10 000 Visits |

|||||||||

| Years | 18–44 Years | 45–64 Years | ≥ 65 Years | 18–44 Years | 45–64 Years | ≥ 65 Years | 18–44 Years | 45–64 Years | ≥ 65 Years | 18–44 Years | 45–64 Years | ≥ 65 Years |

| 1993–1995 | 48.3 | 55.5 | 51.7 | 16.1 | 25.6 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 34.1 | 63.6 | 11.9 | 17.8 | 18.1 |

| 1996–1998 | 47.9 | 67.1 | 59.9 | 30.1 | 37.1 | 44.0 | 13.7 | 37.1 | 49.3 | 17.8 | 42.4 | 37.0 |

| 1999–2001 | 79.8 | 71.5 | 67.6 | 39.2 | 44.1 | 38.7 | 32.2 | 36.5 | 45.1 | 37.8 | 79.1 | 43.5 |

| 2002–2004 | 69.5 | 85.1 | 40.8 | 47.7 | 57.6 | 29.2 | 27.3 | 32.7 | 42.3 | 60.0 | 110.0 | 91.9 |

| 2005–2007 | 69.0 | 81.4 | 57.1 | 73.1 | 71.6 | 53.0 | 28.4 | 46.1 | 63.9 | 143.5 | 228.3 | 159.0 |

| Model statisticsa | ||||||||||||

| Slope, b | 2.10 | 2.33 | −0.28 | 4.40 | 3.75 | 1.58 | 0.93 | 0.68 | −0.16 | 10.63 | 16.95 | 11.69 |

| Correlation, r | 0.70 | 0.93 | −0.13 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.60 | −0.07 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

Note. BDZ = benzodiazepine; NBSH = nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotic.

For model statistics, b is the slope from bivariate regression of variable on year-range midpoint.; r is the temporal correlation of variable with year-range midpoint. Ranges are 3 years except for the first year range for NBSH which is 2 years (1994-1995), because NBSH was not coded in 1993.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of NAMCS data over a 15-year period revealed a striking disparity between rates of sleeplessness complaints and insomnia diagnoses compared with the rapid increase in NBSHs prescribed. NBSH prescriptions grew 21 times more rapidly than did sleeplessness complaints and 5 times more rapidly than did insomnia diagnoses, suggesting that life problems are being treated with medical solutions, without benefit of formal complaint or diagnosis. Conversely, tandem increases in diagnosis and treatment—or significant increases in diagnosis alone—would suggest greater prevalence of a discrete disease state.

Age trends were also suggestive of medicalization. Although middle-aged (those aged 45–64 years) and sometimes younger adults (those aged 18–44 years) lack the changing sleep architecture and increased comorbidities of older adults,26 they still outpaced those aged 65 years and older on all sleeplessness-related measures, excluding benzodiazepine prescription. Increased sleeplessness among young and middle-aged adults may be attributable to nonbiological issues, including stress, multiple social roles, increased use of technology, or targeted marketing of sleep-inducing drugs.3,6,15

Also noteworthy is the convergence of the numbers of complaints and diagnoses in 2006 and 2007. Previously, sleeplessness complaints were more likely to result in a diagnosis of mental illness.27 Greater awareness of correlations between insomnia, health, and quality of life may result in the topic of sleep being introduced in unrelated office visits, prompting diagnoses.28,29 Medicalization may also be a factor; instead of viewing insomnia as a symptom of another illness (e.g., depression or arthritis), it may be viewed as a discrete medical problem with a pharmacological solution.

Although efficacious treatment of sleeplessness positively affects other facets of well-being,27,28 underlying causes and mode of therapy are important considerations. NBSHs are relatively expensive but may be less addictive than are benzodiazepines.30,31 However, NBSHs increase sleep time by less than 12 minutes on average,32,33 and side effects include sleep driving, sleep eating, sleep walking, and short-term amnesia.34,35 NBSHs may be particularly risky for patients who take multiple medications, have histories of drug abuse or mental illness, or are older and at risk for falls.36,37

Proven nondrug treatments exist; a review of 48 clinical trials found that almost 80% of insomnia patients benefited from behavioral therapies for at least 6 months after treatment completion without known side effects.38 Sleep hygiene practices (e.g., controlling diet, exercise, and substance use) and environmental modifications e.g., (light, temperature, noise) can counteract sleep deterrents such as artificial light and 24-hour Internet access.39 Preventing occupational stress and implementing job sharing, flexible hours, and sleep hygiene school curricula, could reduce the societal burden of sleeplessness.6

Despite these facts, prescription sleep aids remain the treatment of choice for most physicians.40 Physicians' choices, however, may be influenced by market pressures, time constraints, direct-to-consumer advertising, and increased consumerism among patients.41,42 With greater awareness and training, clinicians might utilize more nondrug treatments.43,44 Patients, in turn, require more information about the deleterious health effects of long-term sleep loss and the benefits of behavioral therapies.

Although this study goes beyond previous work on the medicalization of sleep by using quantitative indicators to track the outcomes of the patient–physician interaction and highlighting related public health risks, it has several noteworthy limitations. NAMCS was neither intended nor designed to capture or measure the medicalization process and may underrepresent lower-income groups who use emergency services for primary health care. Because the unit of analysis is the office visit, results are suggestive of, but not equivalent to, patient outcomes. Finally, NAMCS is cross-sectional, so data may be capturing the same patients across or within years. However, the 1-week data collection period is unlikely to include repeat visitors.

Sleeplessness may very well be a public health problem, but its medicalization as insomnia—a diagnostic entity with predominantly pharmacological solutions—may encourage overuse of expensive, potentially harmful drugs while deflecting attention from effective public health approaches.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant T-32 HS000032), the National Institute on Aging (grant 2T32AG000272-06A2), and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (grant 5-T32-AT003378).

M. E. Moloney gratefully acknowledges support from Victor Marshall, Barbara Entwisle, Gail Henderson, Peggy Thoits, and Timothy Carey.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina institutional review board (study 08-0593).

References

- 1.Goldberg P, Kaufman D. Everybody's Guide to Natural Sleep: A Drug-Free Approach to Overcoming Insomnia and Other Sleep Disorders. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sumners-Bremner E. Insomnia: A Cultural History. London, England: Reaktion Books; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams SJ. Sleep and Society: Sociological Ventures Into the (Un)known. London, England: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene G. Insomniac. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton WL. Can't sleep? Read this. New York Times, April 2, 2006. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/02/fashion/sundaystyles/02SLEEP.html. Accessed January 31, 2007

- 6.Institute of Medicine Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bains OS. Insomnia: difficulty falling and staying asleep. : Watson NF, Bradley BV, Clinician's Guide to Sleep Disorders. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare; 2006:83–109 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namen AM, Dunagan DP, Fleischer A, et al. Increased physician-reported sleep apnea: The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Chest. 2002;121(6):1741–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, Duurence HH, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30(2):213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch HG, Schwartz L, Woloshin S. What's making us sick is an epidemic of diagnoses. New York Times, January 2, 2007. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/02/health/02essa.html?ex=1168750800&en=e8f868f3aae2f4c5&ei=5070&emc=eta1. Accessed January 6, 2007

- 11.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, et al. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18(6):425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mooallem J. The sleep-industrial complex. New York Times Magazine, November 18, 2007. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/18/magazine/18sleep-t.html?ref=magazine. Accessed November 18, 2007

- 13.Zee PC, Turek FW. Sleep and health: everywhere and in both directions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(16):1686–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koroneos GA. dream campaign. Pharm Exec. 2007;27(6):100–102 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson F. Awakening a sleepy market. Pharm Exec. 2007;27(1):62–66 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad P, Schneider JW. Deviance and Medicalization: From Badness to Sickness. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad P. The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions Into Treatable Disorders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott C. Better Than Well: American Medicine Meets the American Dream. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman SM, Rothman DJ. The Pursuit of Perfection. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams SJ, Seale C, Boden S, Lowe P, Steinburg DL. Medicalization and beyond: the social construction of insomnia and snoring in the news. Health (London). 2008;12(2):251–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seale C, Boden S, Williams S, Lowe P, Steinberg D. Media constructions of sleep and sleep disorders: a study of UK national newspapers. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):418–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hislop J, Arbor S. Understanding women's sleep management: beyond medicalization-healthicization? Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25(7):815–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroll-Smith S, Gunter V. Governing sleepiness: somnolent bodies, discourse, and liquid modernity. Sociol Inq. 2005;75(3):346–371 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ambulatory health care data. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htm. Accessed May 28, 2009

- 25.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ancoli-Israel S, Ayalon L. Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skaer TL, Robison LM, Sclar DA, Galin RS. Psychiatric comorbidity and pharmacological treatment patterns among patients presenting with insomnia: an assessment of office-based encounters in the USA in 1995 and 1996. Clin Drug Investig. 1999;18:161–167 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krystal AD. Treating the health, quality of life and functional impairments in insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(1):63–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz DA, McHorney CA. The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(3):229–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser AD. Use and abuse of the benzodiazepines. Ther Drug Monit. 1998;20(5):481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasu RS, Shenolikar RA, Nahata MC, Balkrishnan R. Physician and patient factors associated with the prescribing of medications for sleep difficulties that are associated with high abuse potential or are expensive: an analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey for 1996–2001. Clin Ther. 2005;27(12):1970–1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, et al. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1335–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saul S. Sleep drugs found only mildly effective, but wildly popular. New York Times, October 23, 2007. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/23/health/23drug.html?_r=1&scp=9&sq=sleep%20pills&st=cse. Accessed December 15, 2007

- 34.Saul S. FDA issues warning on sleeping pills. New York Times, March 15, 2007. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/15/business/15drug.ready.html. Accessed March 30, 2007

- 35.Saul S. Some sleeping pill users range far beyond bed. New York Times, March 8, 2006. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/08/business/08ambien.html. Accessed April 15, 2009

- 36.Hajak G, Müller WE, Wittchen HU, Pittrow D, Kirch W. Abuse and dependence potential for the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics zolpidem and zopiclone: a review of case reports and epidemiological data. Addiction. 2003;98(10):1371–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851–2858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin CM. Psychological and behavioral treatments for primary insomnia. : Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine. 4th ed Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2005:726–737 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(3):215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rybarczyk B, Stepanski E, Fogg L, Lopez M, Barry P, Davis A. A placebo-controlled test of cognitive-behavioral therapy for comorbid insomnia in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1164–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conrad P, Leiter V. Medicalization, markets and consumers. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(extra issue):158–176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stange KC. In this issue: doctor–patient and drug company–patient communication [editorial]. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:2–4 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Espie CA. “Stepped care”: a health technology solution for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy as a first line insomnia treatment. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1549–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chesson AL, Anderson WM, Littner M, et al. Practice parameters for the nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. Sleep. 1999;22(8):1128–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]