Using an analysis of province-level indicators, Stuckler et al. highlighted inequalities in South Africa's health infrastructure that persisted after the end of apartheid.1 Since 2004, the South African government has worked to increase access to HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis prevention as well as to care and treatment services, with extensive support from the US government through the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); the 2010 budget for PEPFAR in South Africa was more than $550 million. We investigated the relationship between the PEPFAR response in South Africa and the need as defined by the burden of HIV/AIDS at the district level.

We calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients to determine the associations among measures of HIV testing, treatment, and services for orphans and vulnerable children from October 2010 to December 2010 PEPFAR monitoring data and HIV/AIDS burden, healthcare infrastructure, socioeconomic status, and perinatal mortality. To indicate the HIV/AIDS burden, we used the number of persons living with HIV by district in 2008.2–4 We used the provincial health care infrastructure ranks per capita1 to indicate health care infrastructure. District-level socioeconomic status and perinatal mortality were also derived from previous reports.5

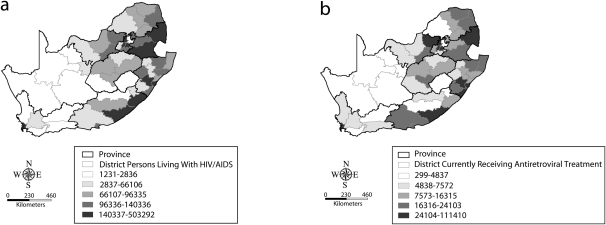

We found strong associations between the HIV/AIDS burden and the persons reached with HIV testing (Spearman rank correlation coefficient [SRCC]=0.73; P<.001), the persons supported for HIV treatment (SRCC=0.83; P<.001; Figure 1), and the orphans and vulnerable children accessing services (SRCC=0.61; P<.001). We found no association between a district's socioeconomic ranking and HIV testing or HIV treatment (SRCC=−0.08; P=.58 and SRCC=0.02; P=.92, respectively). In districts with lower socioeconomic ranking, however, we found a trend toward more orphans and vulnerable children accessing services (SRCC=0.25; P=.07). No association was found between PEPFAR-supported services and perinatal mortality or provincial health care infrastructure rankings.

Number of Persons in South Africa (a) Living With HIV/AIDS, by District, 2008, and (b) Currently Receiving Antiretroviral Treatment for HIV/AIDS Through the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief-Supported Facilities, by District, 2010.

We found that PEPFAR-supported services at the district level significantly correlated with the burden of HIV/AIDS. Whereas Stuckler et al. used province-level indicators, we used district-level measures, which may be more precise. It is reassuring to note that services were delivered according to the burden of disease in the PEPFAR response to HIV/AIDS—South Africa's primary cause of morbidity and mortality.6 Although PEPFAR support largely strengthens services in response to the epidemics of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, research has shown that such services positively affect the general health care infrastructure.7 Because PEPFAR is transitioning from an emergency response model to a capacity-building and health system– strengthening one, the underlying inequities in healthcare services could be further ameliorated.8

Acknowledgments

We thank the Enhancing Strategic Information (ESI) project for producing Figure 1. The ESI project is funded by the US Agency for International Development and implemented by John Snow, Inc. (contract GHS-I-03-07-00002-00).

References

- 1.Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M. Health care capacity and allocations among South Africa's provinces: infrastructure–inequality traps after the end of apartheid. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mid-Year Population Estimates, 2008. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2008. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022008.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Census 2001 Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2003. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/census01/html/default.asp. Accessed May 23, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.2008 National antenatal sentinel HIV & syphilis prevalence survey. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2009. Available at: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/index.html. Accessed May 22, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day C, Monticelli F, Barron P, Haynes R, Smith J, Sello E. District health barometer year 2008/09. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Country health system fact sheet 2006 South Africa. Available at: http://www.who.int/hosis/en. Accessed February 17, 2011

- 7.Brugha R, Simbaya J, Walsh A, Dicker P, Ndubani P. How HIV/AIDS scale-up has impacted on non-HIV priority services in Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(540):1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partnership framework to support the implementation of the HIV & AIDS and TB response (2012-2017) between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the United States of America. Available at: http://www.pepfar.gov/frameworks/southafrica/index.htm. Accessed May 23, 2011