Abstract

Tight junctions are the most apical component of the junctional complex critical for epithelial cell barrier and polarity functions. Although its disruption is well documented during cancer progression such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition, molecular mechanisms by which tight junction integral membrane protein claudins affect this process remain largely unknown. In this report, we found that claudin-7 was normally expressed in bronchial epithelial cells of human lungs but was either downregulated or disrupted in its distribution pattern in lung cancer. To investigate the function of claudin-7 in lung cancer cells, we transfected claudin-7 cDNA into NCI-H1299, a human lung carcinoma cell line that has no detectable claudin-7 expression. We found that claudin-7 expressing cells showed a reduced response to hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) treatment, were less motile, and formed fewer foot processes than the control cells did. In addition, cells transfected with claudin-7 dramatically decreased their invasive ability after HGF treatment. These effects were mediated through the MAPK signaling pathway since the phosphorylation level of ERK1/2 was significantly lower in claudin-7 transfected cells than in control cells. PD98059, a selective inhibitor of ERK/MAPK pathway, was able to block the motile effect. Claudin-7 formed stable complexes with claudin-1 and -3 and was able to recruit them to the cell-cell junction area in claudin-7 transfected cells. When control and claudin-7 transfected cells were inoculated into nude mice, claudin-7 expressing cells produced smaller tumors than the control cells. Taken together, our study demonstrates that claudin-7 inhibits cell migration and invasion through ERK/MAPK signaling pathway in response to growth factor stimulation in human lung cancer cells.

Keywords: Claudin-7, Tight junctions, Cell migration and invasion, ERK1/2, Human lung cancer cells

Introduction

Tight junctions (TJs) are the most apical component of the junctional complex and provide one form of cell-cell adhesion in epithelial cells [1-2]. Claudins are a family of TJ integral membrane proteins that have molecular weights of 20-27 kDa and contain four transmembrane domains [3-4]. They are the major structural and functional components of TJs and play a critical role in regulating paracellular barrier permeability [5-10]. Claudins are widely expressed in almost all epithelial cells and show tissue-specific distribution patterns [11].

Disruption of TJ functions has been reported to be associated with the development of cancers [12]. Several claudin members have been evaluated in primary human tumors to examine their expression levels and cancer progression. Among them, claudin-1, -3, -4, and -7 were either diminished, or elevated, or mislocated in tumor cells compared to the normal adjacent cells [13]. For example, claudin-1 exhibited a consistent elevation in colon carcinoma [14-15] and claudin-7 was shown to be reduced or absent in breast cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [16-17]. Claudin-3 and -4 were frequently overexpressed in ovarian, breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers [18-19]. Downregulation of claudins could contribute to epithelial transformation by increasing the paracellular permeability of nutrients and growth factors to cancerous cells. On the other hand, the barrier function of neoplastic cells could also be altered by upregulation of claudin expression, as they display a disorganized arrangement of TJ strands [20].

Lung cancer usually forms in the epithelial cells lining air passages. Lung cancer can be classified as non-small cell lung cancer (including squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma) and small cell lung cancer. Epithelial cells often express multiple claudin isoforms that interact in a homophilic or heterophilic manner. For example, claudin-1, -3, -4, -5, and -7 were detected in airway epithelial cells while claudin-2, -6, -9, -10, -11, -15, and -16 were not detected in the lung [21]. Chao et al. showed that claudin-1 acted as a metastasis suppressor and could be a useful prognostic predictor and potential drug treatment target for patients with lung adenocarcinoma [22]. Paschoud et al. reported that lung squamous cell carcinomas were positive for claudin-1 and negative for claudin-5, whereas lung adenocarcinomas were positive for claudin-5 and negative for claudin-1. Claudin-4 and tight junction associated protein ZO-1 were detected in both types of tumors [23]. Moldvay et al. analyzed the expression profiles of different claudins in lung cancers and found that claudin-7 was downregulated in several types of lung cancers including the squamous cell carcinoma at the mRNA level [24]. However, the exact roles of claudin-7 in human lung cancers are largely unknown.

The hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor c-Met is a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays an important role in regulating cellular proliferation, motility, and morphogenesis [25]. The binding of HGF to the c-Met receptor results in the autophosphorylation of several tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic domain, thereby activating the c-Met receptor. HGF is normally secreted by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells, but can also be produced by tumor cells with variable expression observed in 45% of lung cancer tumors [25-26]. Navab et al. found that the co-expression of Met and HGF promoted systemic metastasis in NCI-H4650, a human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line [27]. High levels of HGF have also been found in pancreatic cancer [28] and are related to the invasion of ovarian cancer cell [29] and human mammary ductal carcinoma [30]. The HGF inhibitors are considered to have therapeutic potential in cancers [31]. The phosphorylation of c-Met receptors induces several signaling pathways including ERK/MAPK, PI3/Akt, and JNK/SAPK pathways [32]. However, the involvement of claudin-7 in these signaling pathways has not been reported in lung cancer. In this study, we demonstrate that claudin-7 inhibits the upregulation of the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway upon HGF stimulation and thus reduces the cell migration and invasion ability in non-small lung carcinoma cells.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

The rabbit polyclonal anti-MAPK was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The rabbit polyclonal anti-claudin-1 and -3 antibodies were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The rabbit anti-claudin-7 antibody was obtained from IBL (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Japan). The mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The agarose conjugated anti-GFP beads were obtained from MBL (Medical and Biological Laboratories, Japan). All chemicals and reagents were from Sigma. Unless indicated otherwise, all tissue culture reagents including RPMI 1640 culture medium, penicillin/streptomycin, and geneticin were purchased from Invitrogen. All culture plates were from Corning Incorporated (Corning, NY).

Immunohistochemistry analysis of human lung cancer tissue microarray

Lung cancer tissue microarrays were purchased from Pantomics (Richmond, CA), which include 96 cores of normal, inflammatory lung tissue, and common types of lung cancers. All the tissues were from surgical resection. The slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohol washes. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the slides in boiling sodium citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) for 30 min, and endogenous peroxidases were quenched by incubating the slides in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min at room temperature. The slides were then incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against human claudin-7 at room temperature for 1 h followed by incubation of anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. Diaminobenzidine-hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was the chromogen, and the counterstaining was carried out with 0.5% hematoxylin.

Cell culture and transfection

NCI-H1299 (human non-small cell lung cancer cells) cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and grown in RPMI 1640 culture medium containing 10% FBS, 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in humidified air (5% CO2 atmosphere) at 37°C. Claudin-7-GFP and vehicle vectors were transfected into H1299 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 48 h incubation, transfected cells were transferred from 6-well plates to 100-mm plates and geneticin (G418) was added to the plates the next day. Following the geneticin selection, GFP-positive cells were selected using a high speed Flow Cytometry Instrument (Becton Dickinson, Flow Cytometry Core Facility at Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University). This method allowed us to obtain 100% claudin-7-GFP-positive cells, therefore, to better detect the effects of claudin-7 on the changes of cellular functions.

Wound healing (migration) assay

H1299 cells stably transfected with claudin-7 or vector alone were seeded in P60 plates and allowed to grow to full confluence. The monolayer of cells was scratched using a 1 ml pipette tip to create a wound. The plates were washed three times with PBS to remove floating cells before adding the serum-free medium to the plates. Cells were treated with or without 100 ng/ml HGF for 10 h at 37°C and the cell migration distances were photographed at 0, 5, 10 h after the scratches were made. Three fields were randomly selected for each experiment, and three independent experiments were performed to calculate the migration distance using Metamorph software.

Cell invasion assay

Matrigel™ Matrix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was diluted 1:5 using serum free RPMI 1640 medium and added to the Transwell inserts in 24-well plates. Vector transfected or claudin-7 transfected H1299 cells were serum starved overnight, and then trypsinized, centrifuged, and suspended in serum free medium. One×105 cells were added to the Transwell inserts. Four hundred microliters of medium containing 1% of FBS either with or without 100 ng/ml HGF were added to the lower chamber of the plate. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the cells left on the upper surface of the Transwell membrane were gently removed, and the invasive cells on the lower surface of the Transwell membrane were stained with 1% Toluidine Blue. The membranes were then cut out and the invasive cells were observed and counted under the light microscope.

Cell number count in 2- and 3-dimensional (D) cultures

For 2D cultures, vector and claudin-7 transfected H1299 cells were plated in the 6-well culture plates at 5,000 cells per well and then trypsinized at 2, 4, and 6 days, respectively. Cells were counted by both hemacytometer and Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). At least six independent experiments were performed with triplicates for each experiment per time point. For 3D cultures, 150 μl of Matrigel were added to each well of a 24-well plate. Five ×104 cells suspended in 4% Matrigel were added on top of the solidified Matrigel in each well. After cells were plated for 2, 4, and 6 days, the cell recovery solution (BD Biosciences) was added to the each well. Both 4% Matrigel and the solidified Matrigel were digested and removed by centrifuging. The remaining cells were counted by the same methods as used in 2D cell counting.

Annexin V and flow cytometric analysis

Apoptotic and dead cells were analyzed using FlowCellect Annexin Red Kit purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). Cells were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended to 106 cells/ml in 1×Assay Buffer. One hundred microliters of cells in suspension were used and 100 μl of Annexin V working solution (1:20 dilution of Annexin V into the 1×Assay Buffer) were added to each cell sample, followed by incubation in a 37°C CO2 incubator for 15 min. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 1×Assay Buffer again. Five microliters of 7-AAD reagent was added to each sample and then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 5 min. The stained cells were analyzed immediately by BD LSRII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Annexin V positive cells were the early apoptotic cells, while both Annexin V and 7-AAD positive cells represented late stage apoptotic and dead cells.

In vivo tumor xenograft model

Female nude mice (3-5 weeks old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA) and used for human tumor xenografts. Two×106 H1299 cells transfected with vector or claudin-7 were suspended in 200 μl of culture medium and injected subcutaneously into the left and right sides of the rear flank of each nude mouse. It was observed that all nude mice developed tumors for up to 7 weeks after injection, then the mice were sacrificed and the tumors were removed and weighed. The animal experiments were performed according to the animal use protocol approved by East Carolina University.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Origin50 (OriginLab, MA) software. The differences between two groups were analyzed using the unpaired Student's t-test. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Claudin-7 shows altered and reduced expression in human lung cancer

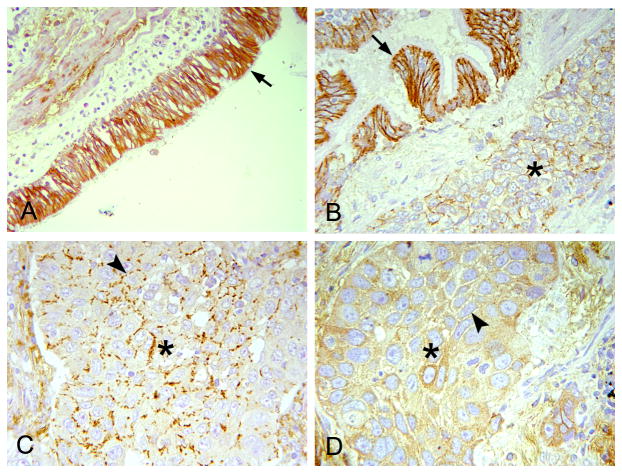

We performed immunohistochemical analyses of claudin-7 expression and distribution using tissue microarrays, which contain both normal human lung tissue and multiple types of lung cancers (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma). Claudin-7 was strongly expressed in benign bronchial epithelial cells with a predominant cell-cell junction staining pattern (Fig. 1A, arrow). In lung cancers, the cell junction expression pattern of claudin-7 was either altered with discontinued weak expression or completely absent. These changes were most obvious in squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 1B, C and D). Fig. 1B shows the remarkable difference between the normal bronchial tissue (arrow) that had strong claudin-7 staining in the cell-cell junction and the adjacent lung cancer tissue (asterisk) that displayed a very weak expression of claudin-7. The arrowheads in Fig. 1C and D point at the cell-cell contact region with discontinued or absent claudin-7 staining, respectively, in the lung cancer.

Fig. 1.

Claudin-7 showed reduced or altered expression in human lung cancer. The expression pattern of claudin-7 was examined by immunohistochemical staining using human lung cancer tissue microarrays. (A) Strong claudin-7 signal was present in benign bronchial epithelial cells with a predominant cell-cell junction staining pattern (arrow). (B) Decreased claudin-7 expression was observed in squamous cell carcinoma (*) with the presence of claudin-7 signal in the nearby normal bronchial epithelial cells (arrow). (C) Discontinued, weak expression of claudin-7 was present (arrowhead) in the cell junctions of squamous cell carcinoma (*). (D) The expression of claudin-7 was absent (arrowhead) in this case of squamous cell carcinoma (*). Magnification: × 200.

Expression of claudin-7 alters the cell morphology in response to HGF

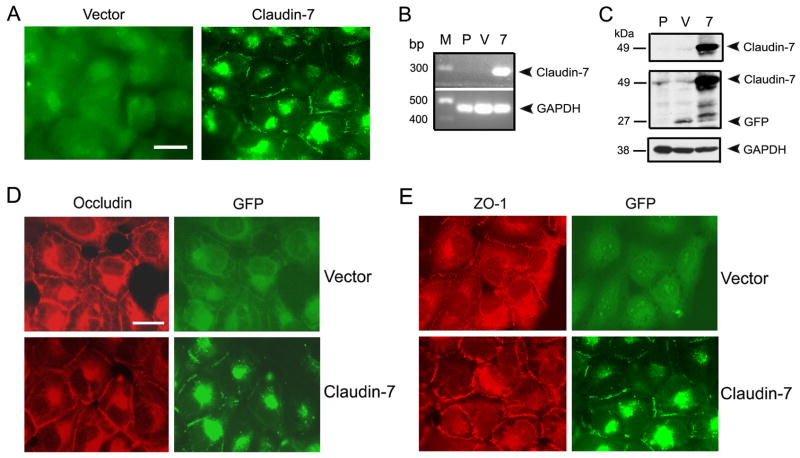

To study the functions of claudin-7 in lung cancer in vitro, we transfected claudin-7 tagged with GFP into NCI-H1299, a human lung carcinoma cell line derived from the metastases in a lymph node. The subcellular localization of overexpressed claudin-7-GFP was examined by a fluorescent microscope. While GFP signal was evenly distributed in the cytoplasm of GFP-vector transfected cells (Fig. 2A), GFP-claudin-7 signal can be clearly visualized at the cell-cell contact area as well as in the intracellular compartments (Fig. 2A). There was no detectable endogenous claudin-7 mRNA in parental (P) and vector transfected (V) H1299 cells by RT-PCR analysis when compared to claudin-7 transfected cells (Fig. 2B). Since claudin-7 was tagged with GFP, it was shown as a 49 kDa protein on Western blot membrane recognized by both anti-claudin-7 and anti-GFP antibodies (Fig. 2C, 7). GFP signal was detected in vector cells as a 27 kDa protein (Fig. 2C, V). To detect the localization of other TJ proteins, occludin (a TJ membrane protein, Fig. 2D) and ZO-1 (a TJ associate protein, Fig. 2E) were double labeled with GFP in vector and claudin-7 transfected cells, respectively. Both occludin and ZO-1 were localized at the cell-cell contact area as well as in the cytoplasm. We also measured transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) and paracellular permeability of tracer molecules in vector and claudin-7 transfected cells (Fig. S1). We did not detect a significant difference in TER between vector and claudin-7 transfected cells although the paracellular permeability of small tracer molecule (fluorescein, M.W.: 332) was reduced in claudin-7 transfected cells.

Fig. 2.

Establishment of NCI-H1299 cells stably transfected with claudin-7 and vector. (A) Ectopic expression of claudin-7 in NCI-H1299 cells. The fluorescent light microscopy revealed the green fluorescent signal in vector-GFP transfected (Vector) and claudin-7-GFP transfected cells (Claudin-7). Bar: 10 μm. (B) Verifying claudin-7 gene transfection in NCI-H1299 cells by RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcripted into cDNA. The RT-PCR products were expected to be a 293 bp fragment for claudin-7 (7) and a 480 bp fragment for GAPDH (positive control). Claudin-7 mRNA was absent in both parental (P) and vector transfected (V) cells. Molecular marker (M) was indicated in the first lane. (C) Immunoblot analysis of claudin-7 expression. Parental (P), vector (V), and claudin-7 (7) cells were lysed in RIPA Buffer, and a total of 20 μg proteins for each sample were loaded onto the SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Membranes were blotted against claudin-7 (top panel) and GFP antibodies (middle panel). GAPDH staining was used as a loading control (bottom panel). Claudin-7 expression was absent in parental and vector transfected cells, but present in claudin-7 transfected cells. (D) and (E) Localization of occludin (D) and ZO-1 (E) in vector and claudin-7 transfected H1299 cells. Occludin and ZO-1 were localized at the cell-cell contact area as well as in the cytoplasm of both vector and claudin-7 transfected cells. (D) and (E): Bar: 10 μm.

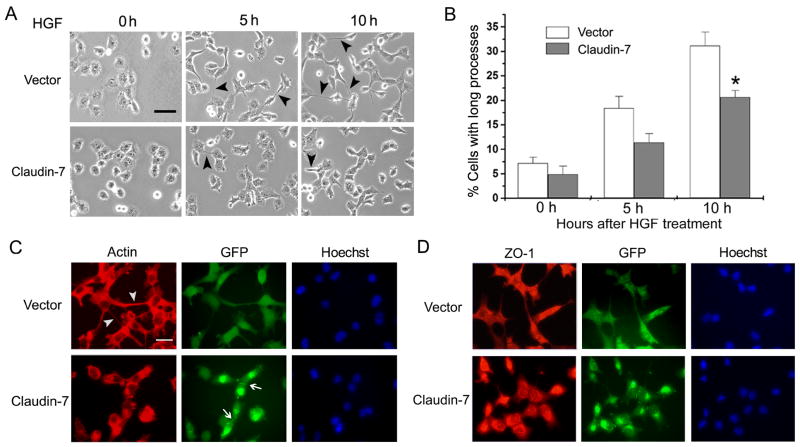

The morphology of claudin-7 and vector transfected cells was very similar under the normal culture condition without any stimulation. However, when the cells were treated with HGF, a cell scattering factor whose receptor, known as c-Met, was expressed in H1299 cells, the difference in the morphological changes was observed between these two cell lines (Fig. 3). After 5 and 10 h of HGF treatments, claudin-7 cells were less motile and formed fewer cell extensions compared to that of vector cells (Fig. 3A, arrowheads). In Fig. 3B, three random areas were chosen from each of the three independent experiments, and cells with foot processes longer than the cell body were measured. The quantitative analyses demonstrated that the vector cells stretched out more and their foot processes were longer than those of the claudin-7 cells (Fig. 3B). Fig. 3C shows the actin staining of cells 10 h after HGF treatment. HGF-treated vector cells stretched out and had long foot processes (Fig. 3C, Vector, arrowheads in Actin staining). These vector cells had no claudin-7 expression (Fig. 2B and C). On the other hand, the claudin-7 expressing cells did not form long foot processes (Fig. 3C, Claudin-7, Actin), and these cells expressed claudin-7 at the cell-cell junction (Fig. 3C, Claudin-7, GFP, arrows). The Hoechst was used to stain the cell nuclei. The cells in Fig. 3D had the same treatment as the cells in Fig. 3C, but were triple stained with ZO-1, GFP, and Hoechst in both cell lines. It showed that ZO-1 was distributed in the cytoplasm after 10 h HGF treatment. These results indicated that claudin-7 may play an important role in inhibiting cell spreading. We did not observe a correlation between the expression level of claudin-7 and its ability in inhibiting cell spreading (Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Morphological changes of vector and claudin-7 transfected cells after HGF treatment. (A) Vector and claudin-7 expressing cells were grown in the normal culture medium for one day, and then the cells were switched to the serum-free medium containing 100 ng/ml HGF (0 h). Phase contrast images were taken at 0 h, 5 h and 10 h following HGF treatment. Arrowheads point to the sample cells with stretched long processes. It was noticed that vector cells showed longer cellular processes than claudin-7 expressing cells. Bar: 20 μm. (B) The statistical analyses demonstrated that, after 5 and 10 h of HGF treatment, the stretching cells with foot processes longer than the cell body were significantly higher in vector cells than in claudin-7 expressing cells. Three random areas were chosen from each experiment. Data was analyzed from three independent experiments. * P<0.05. (C) After 10 h HGF treatment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformadehyde and stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Actin staining) for 30 min. Vector cells showed longer foot processes (arrowheads) than the claudin-7 expressing cells did. Arrows indicate the expression of claudin-7 at the cell-cell junction between two adjacent claudin-7 cells (GFP signal). The cell nucleus was stained by Hoechst. (D) ZO-1 staining after 10 h HGF treatment in vector and claudin-7 transfected H1299 cells. After HGF treatment, the localization of ZO-1 at the cell-cell junction was disrupted and the majority of ZO-1 was relocalized to the cytoplasm (compared to the ZO-1 staining in Fig. 2E). (C) and (D): Bar: 20 μm.

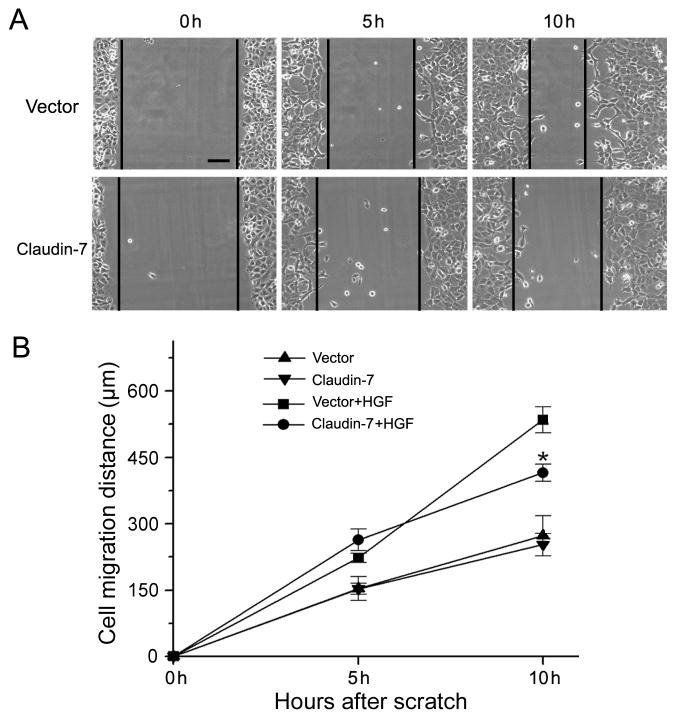

Claudin-7 reduced cell migration and invasion under HGF treatment

The effect of claudin-7 on HGF-induced cell migration was further investigated using the wound healing assay. Cells were cultured until fully confluent, and then a scratch was made to create a wound on the cell monolayer. Fig. 4A showed the result from one of the three independent experiments and Fig. 4B was the summary of these three independent experiments. Our results revealed that, without HGF treatment, there was no significant difference between vector and claudin-7 transfected cells. However, under HGF treatment, the cell migration distance was significantly shorter in claudin-7 cells than in the vector cells at 10 h, indicating that claudin-7 reduced the cell migration ability upon HGF treatment.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of cell migration ability between vector and claudin-7 transfected cells in response to HGF treatment. (A) Cells were grown in the normal culture medium until they reached full confluence and then switched to the serum-free medium containing 100 ng/ml HGF. A scratch was made on the cell monolayer at the zero time point (0 h) to serve as a reference for observing cell migration. Photomicrographs were taken at 0 h, 5 h, and 10 h time points after the scratches were made. Bar: 30 μm. (B) The cell migration distances (μm) were measured at 0, 5, and 10 h time points from three independent experiments. No difference was detected between vector and claudin-7 expressing cells in the untreated groups (serum-free medium without HGF). However, after 10 h of HGF treatment, vector cells showed the higher migration ability as demonstrated by significantly greater cell migration distances than claudin-7 expressing cells. * P < 0.05.

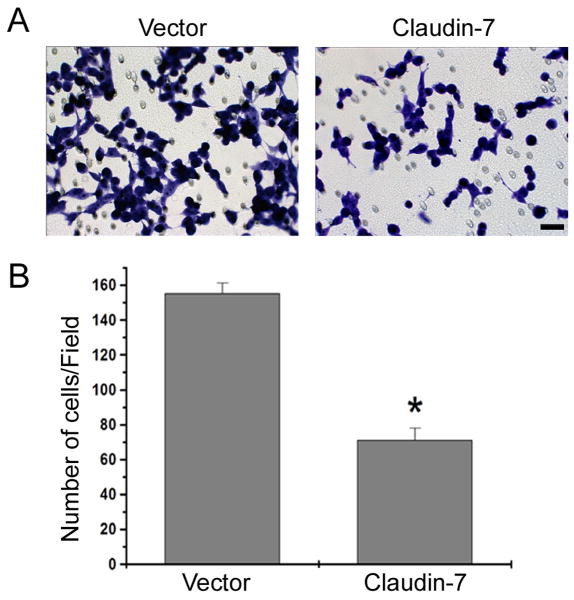

We also investigated whether claudin-7 overexpression could reduce cell invasion, a critical step in cancer cell metastasis. After applying HGF into the lower chamber of a Transwell plate for 24 h, there were more vector transfected cells that migrated through the Matrigel than there were claudin-7 transfected cells (Fig. 5A). Quantitative analyses of five independent experiments demonstrated that there were twice as many invasive cells in the vector transfected cells than in the claudin-7 expressing cells (Fig 5B). This data strongly supports that the cells with claudin-7 expression reduces the cell invasion in response to HGF treatment compared to the cells without claudin-7 expression.

Fig. 5.

Cell invasion assay using Matrigel. (A) Vector and claudin-7 expressing cells were grown on the transwell plates. The culture medium containing 1% FBS and 100 ng/ml HGF was added to the lower chamber. The cells stained with 1% Toluidine Blue were the cells that invaded the Matrigel and migrated through the polycarbonate membrane to the lower surface of the membrane. Bar: 20 μm. (B) Statistical analysis of five independent experiments with triplicates for each experiment revealed a significant difference in the number of invasive cells between vector and claudin-7 expressing cells. * P<0.01.

Claudin-7 attenuated the activation of ERK/MAPK pathway upon HGF treatment and recruited claudin-1 and -3 to the cell membrane

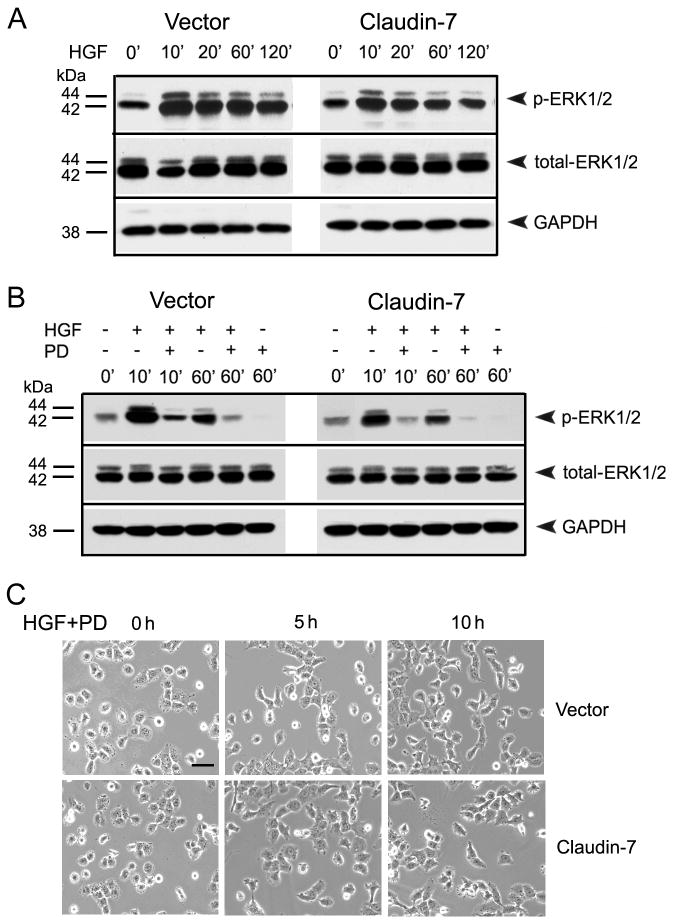

HGF is a growth and scatter factor regulating cellular proliferation, motility, and morphogenesis. After binding to its receptor c-Met, HGF activates the tyrosine kinase of the receptor in its cytoplasmic domain, which initiates the distinct downstream signal transduction cascades including ERK/MAPK, PI3/AKT, JNK/SAPK, and STAT3 pathways [32]. To investigate which pathway is involved in the claudin-7 expression-mediated reduction of cell migration and invasion, we examined these individual pathways. We found that AKT, JNK, and STAT3 were all activated after HGF treatment, but there were no significant differences in phospho-AKT, JNK, and STAT3 expression levels between the vector and claudin-7 expressing cells (data not shown). However, the phospho-ERK1/2 level showed a significant difference between the vector and claudin-7 expressing cells, suggesting that the HGF-induced morphological changes could be mediated through the ERK/MAPK pathway (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6A, the phospho-ERK1/2 did not show a significant difference between vector and claudin-7 cells without HGF treatment (0′). The expression level of phospho-ERK1/2 in both vector and claudin-7 cells was greatly enhanced 10 min after HGF treatment (10′), and thereafter it decreased in a time dependent fashion. However, the amount of phospho-ERK1/2 increase in claudin-7 expressing cells was less than that in vector cells at each time point (Fig. 6A). The total ERK1/2 expression did not show a significant difference in either cell lines with or without HGF treatment.

Fig. 6.

The phospho-ERK1/2 levels in vector and claudin-7 expressing cells with HGF and PD98059 treatments. (A) Cells were grown in culture medium without HGF (0′). Then cells were treated with 100 ng/ml HGF for 10, 20, 60, and 120 min in the serum-free medium before they were lysed in RIPA Buffer. The membrane was immunoblotted against phospho-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Vector and claudin-7 transfected cells were pre-treated with PD98059 for 60 min and then treated with either 100 ng/ml HGF alone or with 50 μM PD98059 for 10 and 60 min. Cells were then lysed in RIPA buffer and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against phopho-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Morphological comparison between vector and claudin-7 expressing cells after HGF combined with PD98059 treatments. Cells were treated with PD98059 for 60 min prior to HGF and PD98059 exposures for 0, 5, and 10 h. The concentrations of HGF and PD98059 used were the same as stated in (B). With HGF/PD98059 treatment, the long cellular processes in both vector and claudin-7 expressing cells were inhibited and no significant differences between them were observed. Bar: 20 μm.

To demonstrate whether the upregulation of phospho-ERK1/2 by HGF and morphological changes are mediated through ERK/MAPK pathway, cells were treated with PD98059, a selective inhibitor for ERK/MAPK pathway, for 60 min prior to HGF treatment. Fig. 6B showed that the upregulation of phospho-ERK1/2 by HGF was greatly reduced by PD98059. It is noticeable that the expression level of phospho-ERK1/2 was higher in vector cells than that in claudin-7 expressing cells after 10 and 60 min treatment of HGF and PD98059 simultaneously, which further indicated that claudin-7 expression reduced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 upon HGF treatment. After 60 min of PD98059 treatment, the expression of phospho-ERK1/2 was completely inhibited in both cells.

We also pre-treated the cells with PD98059 for 60 min, and then switched to the FBS-free medium containing both HGF and PD98059 to study the morphological changes of vector and claudin-7 expressing cells. Neither the vector nor the claudin-7 expressing cells showed significant cell stretching (Fig. 6C, 5 h and 10 h) compared to their control group (Fig. 6C, 0 h) after HGF and PD98059 treatment. There was no morphological difference between the vector and claudin-7 expressing cells at 5 and 10 h of treatments, indicating that PD98059 treatment blocked the effect of HGF in both cells. This data suggests that the morphological changes of the cells were likely mediated through ERK/MAPK pathway.

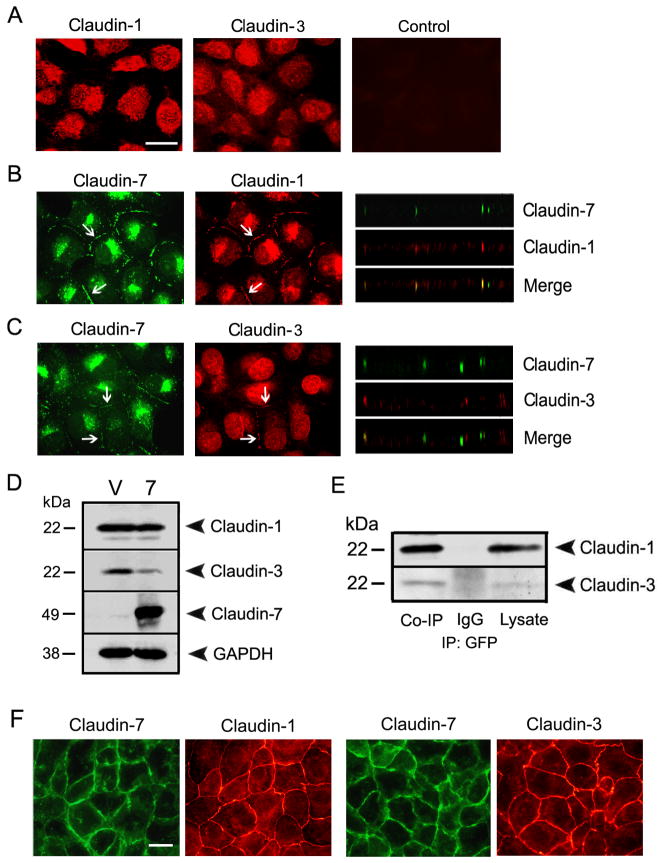

We also examined the localization and expression levels of other claudin members with or without claudin-7 expression. Surprisingly, we observed that without claudin-7, the localization of claudin-1 and -3 was cytosolic (Fig. 7A). However, after claudin-7 transfection, both claudin-1 and -3 were partially redistributed to the cell-cell contact region (arrows) and were colocalized with claudin-7 (arrows) as shown in Fig. 7B and C. This data suggested that claudin-7 was able to recruit claudin-1 and -3 to the cell-cell junction area. By Western blotting analysis, our results revealed that the expression level of claudin-1 remained the same while the claudin-3 expression was downregulated in claudin-7 transfected cells compared to that of vector transfected cells (Fig. 7D). Moreover, claudin-7 was co-immunoprecipitated with claudin-1 and -3 (Fig. 7E), indicating that they formed stable protein complexes in claudin-7 expressing cells. In comparison, there were no changes in the expression and localization of occludin and ZO-1 proteins (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

The interactions of claudin-7 with claudin-1 and -3 in NCI-H1299 cells. (A) Localization of claudin-1 and -3 in vector cells by immunofluorescent staining. Without claudin-7 expression, claudin-1 and -3 were largely localized in the cytoplasm. The Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody staining (Control) served as a negative control. (B) and (C) After claudin-7 was ectopically transfected into NCI-H1299 cells, both claudin-1 (B) and -3 (C) were recruited into cell junction membrane. X-Z planes (right columns) also showed the colocalization of claudin-1 with claudin-7 and the partial colocalization of claudin-3 with claudin-7. (A)–(C): Bar: 10 μm. (D) The expression levels of claudin-1 and -3 in vector (V) and claudin-7 transfected cells (7) by Western blotting. Claudin-1 expression was very similar in both cells while claudin-3 expression was downregulated in claudin-7 transfected cells. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of claudin-7 with claudin-1 and -3. Claudin-7 transfected cells were lysed in RIPA buffer without SDS and immunoprecipitated with the agarose conjugated anti-GFP monoclonal antibody. The membranes were then blotted with either anti-claudin-1 or anti-claudin-3 polyclonal antibodies. The IgG and cell lysates served as negative and positive controls, respectively. (F) As a positive control for claudin-1 and -3 antibodies, HCC827 cells (a human lung adnocarcinoma cell line) were double immunostained with claudin-1 and -7 or with claudin-3 and -7. (F): Bar: 10 μm.

The majority immunostaining signals for claudin-1 and -3 were cytosolic in H1299 cells. In order to confirm that these were the true signals, we used another human lung cancer cell line, HCC827, which has strong endogenous claudin-7 expression (Fig. S2, A). Using the same claudin-1 and -3 primary antibodies, we showed that both claudin-1 and -3 immunostaining signals were nicely localized at cell-cell contact area in HCC827 cells (Fig. 7F). Knockdown of claudin-7 did not disrupt the cell membrane localization of claudin-1 and -3 (data not shown).

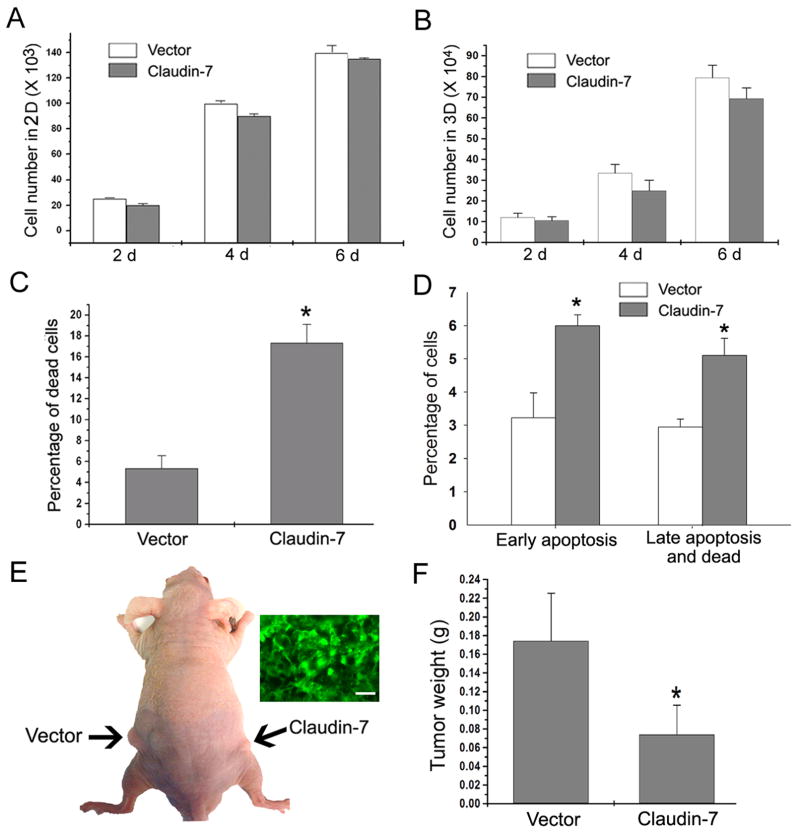

Claudin-7 expression reduced tumor xenograft growth in nude mice

To investigate whether claudin-7 can inhibit cell growth, cell numbers cultured in regular culture plates (2D) and three–dimensional (3D) conditions using Matrigel were evaluated. We did not observe any significant difference in cell number counts in 2D (Fig. 8A) and 3D culture conditions (Fig. 8B), although claudin-7 expressing cells did show a slightly lower number of cell counts on days 4 and 6 (Fig. 8B). Using ethidium bromide and acridine orange (EB/AO) staining, we found that the claudin-7 expressing cells displayed significantly more cell death than the vector cells did (Fig. 8C). This result was further confirmed by Annexin V apoptosis assay and flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 8D)

Fig. 8.

Tumorigenesis in nude mice induced by inoculation of vector and claudin-7 transfected H1299 cells. (A) Vector and claudin-7 transfected H1299 cells were plated in 6-well culture plates at 5,000 cells per well and counted at 2, 4, and 6 days for cell growth in two dimensional (2D) cultures. Results were obtained from six independent experiments. (B) Five × 104 cells were plated on the Matrigel matrix. Cells were recovered from the matrix at 2, 4, and 6 days after plating using the cell recovery solution, and the number of cells was counted for each sample. The data was obtained from four independent experiments. (C) Cells were grown on the regular culture plates and the percentage of cell death was examined in vector and claudin-7 expressing cells by EB/AO staining. The data was obtained from six independent experiments. * P<0.05. (D) Annexin V apoptosis assay was used to detect apoptotic cells as well as dead cells. The Annexin V positive cells were the early apoptotic cells, while both Annexin V and 7-AAD positive cells were the late apoptotic/dead cells. The percentages of early apoptotic cells and late apoptotic/dead cells in claudin-7 transfected cells were significantly higher than those in the vector transfected cells. * P<0.05. (E) Vector or claudin-7 transfected cells were harvested and suspended in the culture medium. Two × 106 cells were subcutaneously injected into the left and right sides of the nude mice. Arrows indicate the tumors generated subcutaneously in nude mice. Insert figure shows the frozen section of a tumor induced by claudin-7 expressing cells to show the retained claudin-7-GFP signals. Bar: 30 μm. (F) The nude mice were sacrificed seven weeks after the injection, and the tumors were removed and weighed. Claudin-7 expressing cells-induced tumors in nude mice were smaller in size compared to those of vector cells. The data was analyzed from twelve nude mice. * P < 0.05.

To study whether claudin-7 can inhibit tumor growth in vivo, we injected vector or claudin-7 expressing NCI-H1299 cells into the nude mice. As shown in Fig. 8E (arrows), the tumor size inoculated with vector cells was much larger than that induced by the inoculation with claudin-7 cells. The insert is a GFP-image that was taken from the tumor induced by claudin-7 expressing cells to show that tumor cells retained the claudin-7 expression. Fig. 8F showed the quantitative analysis confirming that the sites inoculated with claudin-7 expressing cells developed the tumors three times smaller in weight than those inoculated with vector transfected cells, demonstrating that claudin-7 inhibited the tumor growth in vivo.

Discussion

In this study, we found that claudin-7 expression was either downregulated or its localization was disrupted in human lung cancer tissues. To investigate how claudin-7 affects the behavior of lung cancer cells, we transfected claudin-7 tagged with GFP into a human non-small cell lung cancer cell line NCI-H1299. Our results demonstrated that claudin-7 significantly reduced the cell migration and invasive ability upon HGF treatment. This effect is most likely through the attenuated activation of ERK/MAPK pathway in response to HGF stimulation since the inhibition of MAPK pathway abolished this effect completely. We also demonstrated that claudin-7 was able to recruit claudin-1 and -3 from the cytoplasm to cell-cell contact area. Finally, in vivo analyses demonstrated that claudin-7 reduced xenograft tumor growth in nude mice.

It is known that cell-cell adhesion is reduced in many different types of human cancer. The escape of cancer cells from the primary tumor sites is a crucial step in invasion and metastasis. Disruption of cell-cell junctions may trigger the release of cancer cells from the primary cancer sites and confer invasive properties on a tumor [33]. Claudins are a family of TJ membrane proteins with cell adhesive properties [34]. Many claudins, including claudin-7, have been reported to be downregulated in various human cancers. For example, Moustafa et al. reported that claudin-7 was downregulated in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas compared to normal cells [17]. Kominsky et al. found that loss of claudin-7 correlated with histological grade in both ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast [16]. Yu Usami DDS et al. found that reduced expression of claudin-7 at the invasive front of the esophageal cancer was significantly associated with the depth of invasion, stage, lymphatic vessel invasion, and lymph node metastasis [33]. Therefore, we hypothesize that claudin-7 may act as a tumor inhibitor in human cancers. An alternative explanation could be that the claudin-7 expressing cells were more highly differentiated. Although overexpression of claudin-7 did not induce E-cadherin expression in H1299 cells, claudin-7 expressing cells showed less motility with reduced cell migration and invasive ability compared to the vector transfected cells after HGF treatment. We propose that ERK/MAPK pathway was involved in this process since claudin-7 expressing cells displayed the significantly reduced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 compared to the control cells after growth factor treatment. However, it is currently unclear how claudin-7 interacts with the ERK/MAPK pathway. Claudin-7 may bind to the upstream components of MAPK pathway and exert a negative effect to reduce the activation of ERK1/2 in the presence of growth factor stimulation.

The interactions between MAPK pathway and tight junction proteins have been previously reported [35-36]. For example, TJ membrane protein occludin participates in the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway [37]. In the hepatic cell line derived from occludin-deficient mice, MAPK activation was downregulated, which triggered the apoptosis and increased claudin-2 expression. However, when occludin was transfected into these occludin-deficient cells, MAPK became activated and the increases in claudin-2 expression and apoptosis were diminished [37].

Nakamura's group at Osaka University was the first to purify and clone HGF [38]. HGF has been shown to exhibit a wide variety of biological activities including the stimulation of tumor proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis through c-Met receptor in a variety of cancers. In this study, we showed that HGF promoted cell migration in both vector and claudin-7 transfected NCI-H1299 lung carcinoma cells. But interestingly, with HGF treatment, claudin-7 expressing cells showed less motility and formed fewer cell processes than the vector cells did. In addition, less migratory behavior was observed in claudin-7 expressing cells. The cell invasion assay also showed that the vector transfected cells displayed a higher invasive ability than the claudin-7 transfected cells upon HGF treatment. The upregulation of phospho–ERK1/2 by HGF was reduced in claudin-7 expressing cells, indicating that claudin-7 may negatively affect HGF-induced ERK/MAPK pathway activation.

PD98059 is a specific inhibitor of MEK1/2, which is immediately upstream of ERK/MAPK activation and is known to inhibit the migration of diverse cell types [39-40]. In the current study, in order to verify that cell migration was mediated through the ERK/MAPK pathway, we used PD98059 to treat the cells. Our results showed that PD98059 was able to completely inhibit the activation of ERK1/2. The cells with HGF/PD98058 treatment no longer have long cellular processes compared to the cells with HGF alone treatment. After HGF/PD98059 treatment, there was no difference in cell morphology between claudin-7 and vector transfected cells. This confirmed that ERK/MAPK pathway was indeed involved in the cell migration and invasion in NCI-H1299 cells.

Other signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt pathway, can also interact with tight junction proteins. It has been reported that in the hepatic cell lines derived from occludin-deficient mice, the activation of MAPK and Akt was decreased and cell apoptosis was increased. Ectopic expression of occludin to these hepatic cells increased Akt activity and inhibited apoptosis, which suggested that lack of occludin made hepatocytes sensitive to proapoptotic stimuli due to a decrease in Akt activity [37]. In our study, phospho-Akt was upregulated in both vector and claudin-7 cells after HGF treatment. However, there was no expression difference of phospho-Akt between these two cell lines (data not shown). We also examined p38 and SAPK/JNK, but no changes in their expression levels have been observed between vector and claudin-7 cells. Therefore, the inhibition of migration and invasion by claudin-7 expression was likely through ERK/MAPK pathway, but not AKT, p38 and/or JNK pathways in NCI-H1299 lung cancer cells. It is unclear at the present time how exactly claudin-7 affected the cell migration and invasion through ERK/MAPK cascade. Fujibe et al. reported that Thr203 of claudin-1 was a putative phosphorylation site for MAPK, which was required to promote the barrier function of tight junctions [41]. Chen et al. found that inhibition of the MEK pathway restored the tight junction formation and claudin-1 and E-cadherin localization in Ras-transformed Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells [42]. In our current study, it is possible that claudin-7 may serve as an inhibitor of the upstream elements of ERK/MAPK pathway, thus downregulating the ERK1/2 activity and reducing cell motility. It is important to note that while claudin-1 and -3 were localized in the cytoplasm of vector cells, their localization was changed to the cell-cell junction area in claudin-7 expressing cells. The localization change of claudin-1 and -3 from cytoplasm to the cell-cell junction area was also observed in H522 human lung cancer cells after claudin-7 transfection (data not shown). We propose that claudin-7 is able to recruit claudin-1 and -3 to the cell membrane although we cannot rule out the possibility that it is due to the cell phenotype change after claudin-7 expression. The recruitment of claudin-1 and -3 to cell junctions could contribute to the reduced cell migration and invasive ability mediated through claudin-7 expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jiao Zhang, Rodney Tatum, and Beverly G. Jeansonne for their technical assistance. This work was supported by a research award from ECU Division of Research and Graduate Studies and National Institute of Health grants ES016888 and HL085752.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–293. doi: 10.1038/35067088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneeberger EE, Lynch RD. The tight junction: a multifunctional complex. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1213–1228. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00558.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita K, Furuse M, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin multigene family encoding four-transmembrane domain protein components of tight junction strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:511–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Mariscal L, Betanzos A, Nava P, Jaramillo BE. Tight junction proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;81:1–44. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(02)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukita S, Furuse M. Claudin-based barrier in simple and stratified cellular sheets. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:403–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amasheh S, Meiri N, Gitter AH, Schoneberg T, Mankertz J, Schulzke JD, Fromm M. Claudin-2 expression induces cation-selective channels in tight junctions of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4969–4976. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu AS, Enck AH, Lencer WI, Schneeberger EE. Claudin-8 expression in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells augments the paracellular barrier to cation permeation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17350–17359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandre MD, Lu Q, Chen YH. Overexpression of claudin-7 decreases the paracellular Cl- conductance and increases the paracellular Na+ conductance in LLC-PK1 cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2683–2693. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin K, Fogg VC, Margolis B. Tight junctions and cell polarity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:207–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turksen K, Troy TC. Barriers built on claudins. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2435–2447. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soler AP, Miller RD, Laughlin KV, Carp NZ, Klurfeld DM, Mullin JM. Increased tight junctional permeability is associated with the development of colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1425–1431. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.8.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swisshelm K, Macek R, Kubbies M. Role of claudins in tumorigenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:919–928. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miwa N, Furuse M, Tsukita S, Niikawa N, Nakamura Y, Furukawa Y. Involvement of claudin-1 in the beta-catenin/Tcf signaling pathway and its frequent upregulation in human colorectal cancers. Oncol Res. 2001;12:469–476. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhawan P, Singh AB, Deane NG, No Y, Shiou SR, Schmidt C, Neff J, Washington MK, Beauchamp RD. Claudin-1 regulates cellular transformation and metastatic behavior in colon cancer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1765–1776. doi: 10.1172/JCI24543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kominsky SL, Argani P, Korz D, Evron E, Raman V, Garrett E, Rein A, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Sukumar S. Loss of the tight junction protein claudin-7 correlates with histological grade in both ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Oncogene. 2003;22:2021–2033. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Moustafa AE, Alaoui-Jamali MA, Batist G, Hernandez-Perez M, Serruya C, Alpert L, Black MJ, Sladek R, Foulkes WD. Identification of genes associated with head and neck carcinogenesis by cDNA microarray comparison between matched primary normal epithelial and squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:2634–2640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morin PJ. Claudin proteins in human cancer: promising new targets for diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9603–9606. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewitt KJ, Agarwal R, Morin PJ. The claudin gene family: expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Mariscal L, Lechuga S, Garay E. Role of tight junctions in cell proliferation and cancer. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2007;42:1–57. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coyne CB, Gambling TM, Boucher RC, Carson JL, Johnson LG. Role of claudin interactions in airway tight junctional permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L1166–1178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00182.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chao YC, Pan SH, Yang SC, Yu SL, Che TF, Lin CW, Tsai MS, Chang GC, Wu CH, Wu YY, Lee YC, Hong TM, Yang PC. Claudin-1 is a metastasis suppressor and correlates with clinical outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:123–133. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-456OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paschoud S, Bongiovanni M, Pache JC, Citi S. Claudin-1 and claudin-5 expression patterns differentiate lung squamous cell carcinomas from adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:947–954. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moldvay J, Jackel M, Paska C, Soltesz I, Schaff Z, Kiss A. Distinct claudin expression profile in histologic subtypes of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence RE, Salgia R. MET molecular mechanisms and therapies in lung cancer. Cell Adh Migr. 2010;4:146–152. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.1.10973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma PC, Tretiakova MS, MacKinnon AC, Ramnath N, Johnson C, Dietrich S, Seiwert T, Christensen JG, Jagadeeswaran R, Krausz T, Vokes EE, Husain AN, Salgia R. Expression and mutational analysis of MET in human solid cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:1025–1037. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navab R, Liu J, Seiden-Long I, Shih W, Li M, Bandarchi B, Chen Y, Lau D, Zu YF, Cescon D, Zhu CQ, Organ S, Ibrahimov E, Ohanessian D, Tsao MS. Co-overexpression of Met and hepatocyte growth factor promotes systemic metastasis in NCI-H460 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1292–1300. doi: 10.1593/neo.09622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kemik O, Purisa S, Kemik AS, Tuzun S. Increase in the circulating level of hepatocyte growth factor in pancreatic cancer patients. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2009;110:627–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei W, Kong B, Yang Q, Qu X. Hepatocyte growth factor enhances ovarian cancer cell invasion through downregulation of thrombospondin-1. Cancer Biol Ther. 9 doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.2.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jedeszko C, Victor BC, Podgorski I, Sloane BF. Fibroblast hepatocyte growth factor promotes invasion of human mammary ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9148–9155. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parr C, Sanders AJ, Jiang WG. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Activation Inhibitors - Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009 doi: 10.2174/1871520611009010047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma PC, Tretiakova MS, Nallasura V, Jagadeeswaran R, Husain AN, Salgia R. Downstream signalling and specific inhibition of c-MET/HGF pathway in small cell lung cancer: implications for tumour invasion. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:368–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Usami Y, Chiba H, Nakayama F, Ueda J, Matsuda Y, Sawada N, Komori T, Ito A, Yokozaki H. Reduced expression of claudin-7 correlates with invasion and metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubota K, Furuse M, Sasaki H, Sonoda N, Fujita K, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S. Ca(2+)-independent cell-adhesion activity of claudins, a family of integral membrane proteins localized at tight junctions. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80452-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lan M, Kojima T, Osanai M, Chiba H, Sawada N. Oncogenic Raf-1 regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition via distinct signal transduction pathways in an immortalized mouse hepatic cell line. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2385–2395. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipschutz JH, Li S, Arisco A, Balkovetz DF. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 control claudin-2 expression in Madin-Darby canine kidney strain I and II cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3780–3788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murata M, Kojima T, Yamamoto T, Go M, Takano K, Osanai M, Chiba H, Sawada N. Down-regulation of survival signaling through MAPK and Akt in occludin-deficient mouse hepatocytes in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura S, Moriguchi A, Morishita R, Aoki M, Yo Y, Hayashi S, Nakano N, Katsuya T, Nakata S, Takami S, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Higaki J, Ogihara T. A novel vascular modulator, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), as a potential index of the severity of hypertension. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:238–243. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grotegut S, von Schweinitz D, Christofori G, Lehembre F. Hepatocyte growth factor induces cell scattering through MAPK/Egr-1-mediated upregulation of Snail. EMBO J. 2006;25:3534–3545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujibe M, Chiba H, Kojima T, Soma T, Wada T, Yamashita T, Sawada N. Thr203 of claudin-1, a putative phosphorylation site for MAP kinase, is required to promote the barrier function of tight junctions. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Lu Q, Schneeberger EE, Goodenough DA. Restoration of tight junction structure and barrier function by down-regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in ras-transformed Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:849–862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.