Weight loss surgery (WLS) has had a tumultuous history. The initial operations performed 5 decades ago had questionable weight loss, carried unacceptably high risks, and had unknown long-term health benefits [1]. For many years, WLS was the option of last resort and only for the most extremely debilitated patients. But things have changed, and dramatically so. Unbridled growth in severe obesity has been matched by advances in surgical techniques and technologies available for its treatment. Soon it may not be unreasonable to consider WLS as the first line treatment for obesity and weight-related comorbidities like diabetes and sleep apnea.

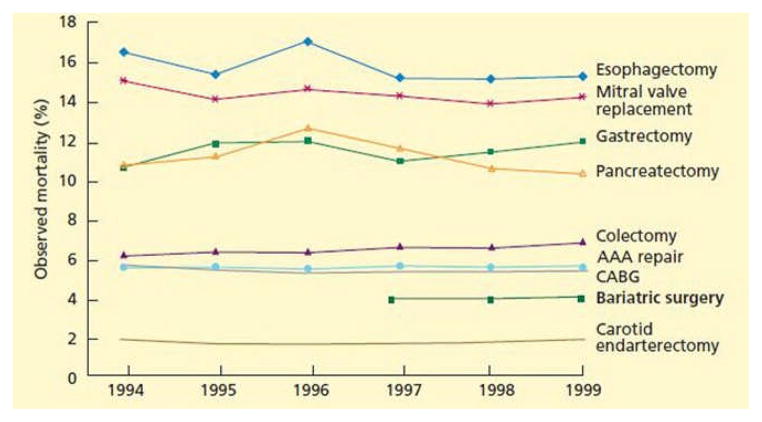

Indeed WLS offers much more than significant and sustained weight loss. Recent studies demonstrate its ability to cure diabetes [2], to improve outcomes from cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a large, matched cohort of patients [3], and to reduce the risk of death by approximately 35% over time [4,5]. Findings from the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery I (LABS-1) trial, a prospective, multicenter observational study in 4776 WLS patients, reported a 30-day overall death rate of 0.3%, with serious complications in 4.1% of patients—figures similar to those seen in other major operations [1,6–9] (Fig 1). Between 1998 and 2004, the number of weight loss procedures performed in the United States soared by 800% to 121,500 [10]. That number reached 171,000 in 2005 [1]. Despite this exponential growth, WLS still has the perception of being a risky procedure among the general public, insurance companies, and even other health care providers. The sheer number of cases performed annually has raised concerns among third party payers and government agencies about provider qualifications and patient safety. For its part, the obesity health care providers have gone through great lengths to ensure that the quality of WLS has kept pace with quantity. Fellowships devoted solely to bariatric surgery have been established [1], and more importantly, evidence-based standards for the care of WLS patients have been published [11].

Fig 1.

Mortality after bariatric and other surgery after age 65. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting. (Reprinted with permission from Flum et al [84]. Adapted with permission from original in Goodney PP, Siewers AE, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Wennberg DE, Birkmeyer JD. Is surgery getting safer? National trends in operative mortality. J Am Coll Surg 2002;195:219–27.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

The first such report came in the wake of a massive chemotherapy overdose that killed Boston Globe journalist Betsy Lehman [12] and led to the subsequent creation of the Betsy Lehman Center for Patient Safety and Medical Error Reduction (Lehman Center). This organization’s mission is to improve patient safety by developing evidence-based, best practice standards of care.

In 2004, the Lehman Center and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health convened an Expert Panel [13] to assess weight loss procedures, identify issues related to patient safety, and develop evidence-based best practice recommendations. The Panel worked with more than 100 specialists in 9 separate task groups to examine every facet of care—from psychological evaluation and anesthetic perioperative procedures to multidisciplinary treatment and data collection (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Surgical care |

| Criteria for patient selection and multidisciplinary evaluation and treatment |

| Patient education/informed consent |

| Anesthetic perioperative care and pain management |

| Nursing perioperative care |

| Pediatric/adolescent care |

| Facility resources |

| Coding and reimbursement |

| Data collection/future considerations |

| Endoscopic intervention |

| Policy and access to care |

The resulting document, published as a supplement to Obesity in 2005 [13], set the standard for WLS across the state and well beyond it. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) abstracted the report for broad use and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) used it as the blueprint for its Bariatric Surgery Network Center accreditation program. Its recommendations influenced health care policy and medical practice in the United States and abroad [14].

Much has happened since 2005, including rapid growth in the literature, development of new procedures, shifting patient demographics, shorter lengths of hospital stay, and widespread use of laparoscopy. To address the impact of these changes on patient safety, the Lehman Center reconvened the Expert Panel in 2007 to update the earlier systematic literature review and evidence-based recommendations.

The new report, published in Obesity 2009 [15], is even more comprehensive than the first. It covers every practice area in the original publication as well as 2 new topics: endoscopic interventions and policy and access. Recommendations were developed using an established evidence-based model. This approach was used to optimize patient safety in a high-risk specialty that continues to grow at a breakneck pace, fueled, in part, by the high failure rate of alternative therapies (eg, improved nutrition, behavior modification, increased exercise, and medications) [9,16].

In 2006, the number of weight loss procedures performed in the United States topped 200,000 [17]; in 2008, that figure reached an estimated 220,000 [18,19]. Weight loss operations will continue to grow at an accelerating pace as evidence on their safety and efficacy mounts and more insurers provide coverage [20]. Today, there are approximately 15 million people in the United States with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 kg/m2, but only 1% of the clinically eligible population receives surgical treatment for their obesity [18].

This situation is not limited to the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 400 million adults currently have class I obesity (BMI >30). By the year 2015, that number is expected to reach an estimated 700 million [21]. Without intervention, only 1 in 7 obese patients will reach their full life expectancy [22,23].

Bariatric surgery has taken on many forms since the first operations in the 1950s. Five decades later, no single “best” operation has emerged from the available options. But a lot of effort has been placed on determining the best way to treat obesity and to avoid the complications of WLS. Care starts with a multidisciplinary approach to surgical weight loss and ends with life-long follow-up for those who undergo WLS.

Multidisciplinary Teams

WLS patients suffer from a multifactorial disease that makes them a uniquely vulnerable population in need of specialized resources and ongoing multidisciplinary care [15,24]. The Lehman Center report stressed the need to use dedicated teams to provide best practice treatment (Table 2). These should include surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, psychologists, dietitians, and others who are specially trained to deliver pre-, peri-, and postoperative care. Use of such teams can identify obesity-related conditions that may put patients at increased operative risk for complications, morbidity, and mortality [25]. Dedicated, multidisciplinary treatment teams and support groups for long-term follow-up have improved the efficacy and safety of WLS. So, too, have accredited “Centers of Excellence” that implement evidence-based, best practice standards.

Table 2.

Assets of multidisciplinary surgical weight loss team [14]

| Assets to multidisciplinary surgical weight loss program (required) |

| Bariatric surgeons (2) |

| Bariatrician |

| Pediatric obesity specialist* Program coordinator Dietitian/nutritionist |

| Psychiatrist/psychologist/social worker |

| Exercise physiotherapist |

| Surgical floor nurses |

| Operating room nurses |

| Operating room technicians |

| Receptionist |

| Additional assets to multidisciplinary surgical weight loss program (preferred) |

| Anesthesiologist |

| Gastroenterologist |

| Radiologist |

| Cardiologist |

| Pulmonologist |

| Endocrinologist |

For pediatric weight loss surgery only.

Minimally Invasive WLS

Since 2004, WLS has been mainstreamed into accredited training programs in the United States [26]. This change has helped shorten the learning curve for laparoscopic operations. In recent years, minimally invasive WLS has increased from 9.4% of procedures to 71.0%. In large part, this shift accounts for the growing popularity of WLS and the rapid increase in the number operations performed [27].

Minimally invasive techniques have reduced some of the complications in readmissions rates, and a 2.3-day decrease in length of stay [27] (Table 3). Laparoscopy has not only led to greater acceptance of WLS as a treatment for obesity, but it has also paved the way for new kinds of procedures. Overall, laparoscopy has been a notable advance. A comparison between patients who had WLS in the 2001 to 2002 period and those who had it between 2005 and 2006 shows a 21% decrease in total complications, 37% decrease in inpatient complications, 31% decrease in readmissions rates, and a 2.3-day decrease in length of stay [27] (Table 3). Laparoscopy has not only led to greater acceptance of WLS as a treatment for obesity, but it has also paved the way for new kinds of procedures.

Table 3.

Risk-adjusted changes in bariatric outcomes and utilization over time

| Unadjusted | Risk adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2002 | 2005–2006 | 2001–2002 | 2005–2006 | |

| Inpatient complication rate | 21.93% | 15.31%* | 23.60% | 14.81%* |

| 30-day overall complication rate | 32.39% | 26.31%* | 33.68% | 25.45%* |

| 180-day overall complication rate | 39.57% | 33.64%* | 41.69% | 32.81%* |

| Specific 180-day complications | ||||

| Anastomosis complications | 12.29% | 9.48%* | 13.01% | 9.26%* |

| Marginal ulcer | 0.99% | 2.05%* | 1.81% | 2.05% |

| Abdominal hernia | 7.10% | 4.83%* | 7.19% | 4.81%* |

| Dumping, vomiting, diarrhea, etc. | 19.59% | 19.34% | 21.44% | 18.63% |

| Hemorrhage | 1.67% | 2.06% | 1.96% | 1.94% |

| Wound dehiscence | 1.78% | 2.32% | 2.19% | 2.15% |

| Infection | 5.59% | 3.32%* | 7.16% | 3.03%* |

| Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism | 2.34% | 2.47% | 2.50% | 2.40% |

| Respiratory failure | 3.05% | 2.42%† | 4.27% | 2.15%* |

| Pneumonia | 4.08% | 3.26%† | 5.02% | 3.01%‡ |

| Postoperative acute myocardial infarction | 0.32% | 0.40% | 0.46% | 0.37% |

| Postoperative stroke | 0.00% | 0.08% | — | 0.10% |

| Readmission with complication | 7.18% | 7.59% | 9.78% | 6.79%* |

| Emergency room visit with complication | 1.31% | 1.86%† | 1.44% | 1.79% |

| Outpatient hospital visit with complication 14.23% | 13.48% | 14.78% | 13.26%* | |

| Office visit with complication | 11.22% | 11.11% | 12.61% | 10.60% |

| 180-daytotal hospital days (days) | 6.0 | 4.0* | 6.1 | 3.7* |

| 180-day total hospital payments ($) | 31,016 | 27,591‡ | 29,563 | 27,905* |

| 180-day inpatient physician payments ($) | 3308 | 3151 | 3383 | 3128 |

Adapted with permission from Encinosa and colleagues [27].

Significantly different from the 2001–2002 complication rate at the 99% level.

Significantly different from the 2001–2002 complication rate at the 90% level.

Significantly different from the 2001–2002 complication rate at the 95% level.

Types of WLS

Primary operations for WLS are either restrictive, malabsorptive, or a combination of both (Table 4). Most malabsorptive procedures fall into the latter category. The 2 most common operations in the United States today are the adjustable gastric band (AGB) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [30]. Other approaches include sleeve gastrectomy (SG), biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) with or without a duodenal switch (DS), vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG), and jejunoilial bypass (JIB). Very few VBGs are performed due to numerous complications. JIB has been abandoned altogether for the same reason [31].

Table 4.

Types of weight loss surgery operations

| Types of operation | % excess weight loss | |

|---|---|---|

| Restrictive | Adjustable gastric band (AGB) | 50–60% [165] |

| Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) | 33–83% [187,190] | |

| Vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) | 63–70% [196] | |

| Malabsorptive | Jejunal-ileal bypass (JIB) | |

| Combined | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) | 70–80% [53] |

| Biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch (BPD-DS) | 77–88% [276,386] | |

| Endoscopic | Intragastric balloon | 27–48% [297] |

| Endoluminal sleeve | NA | |

| Endoluminal plication | NA | |

| Others | Gastric pacing | 40% [303] |

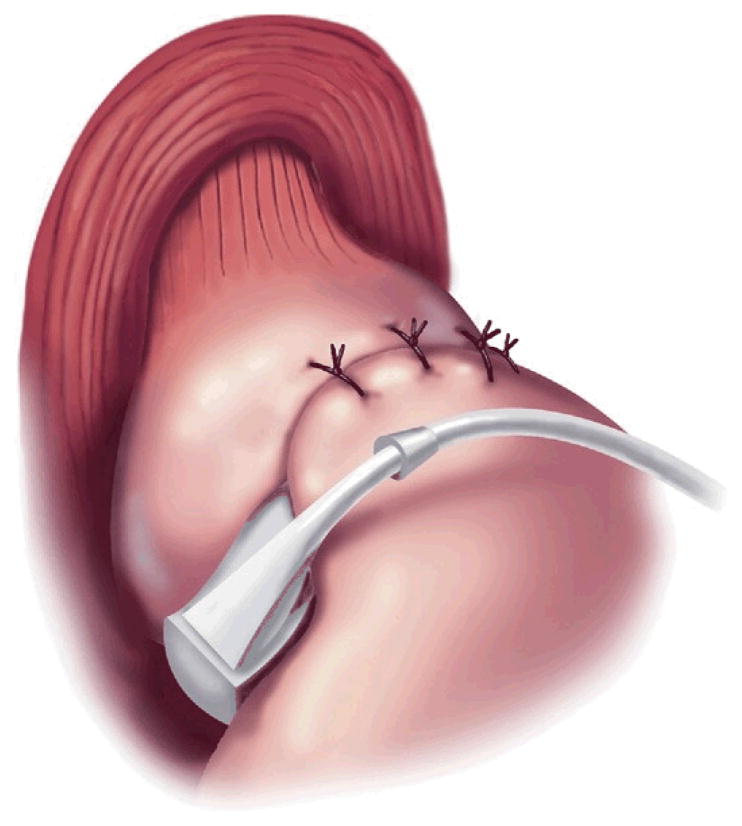

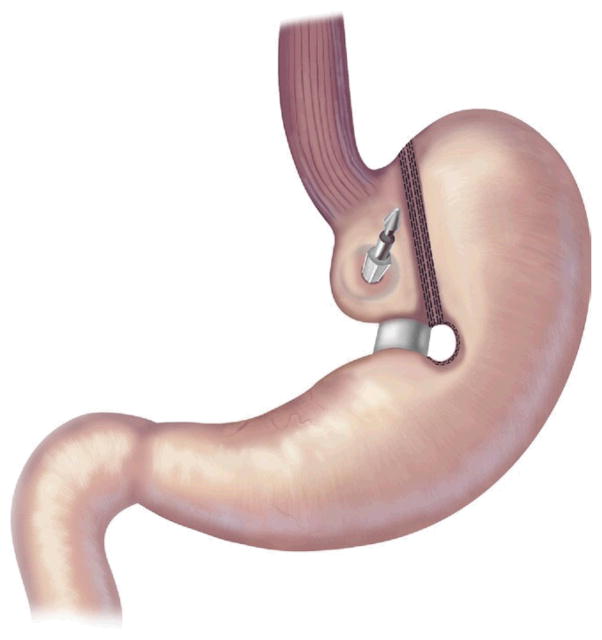

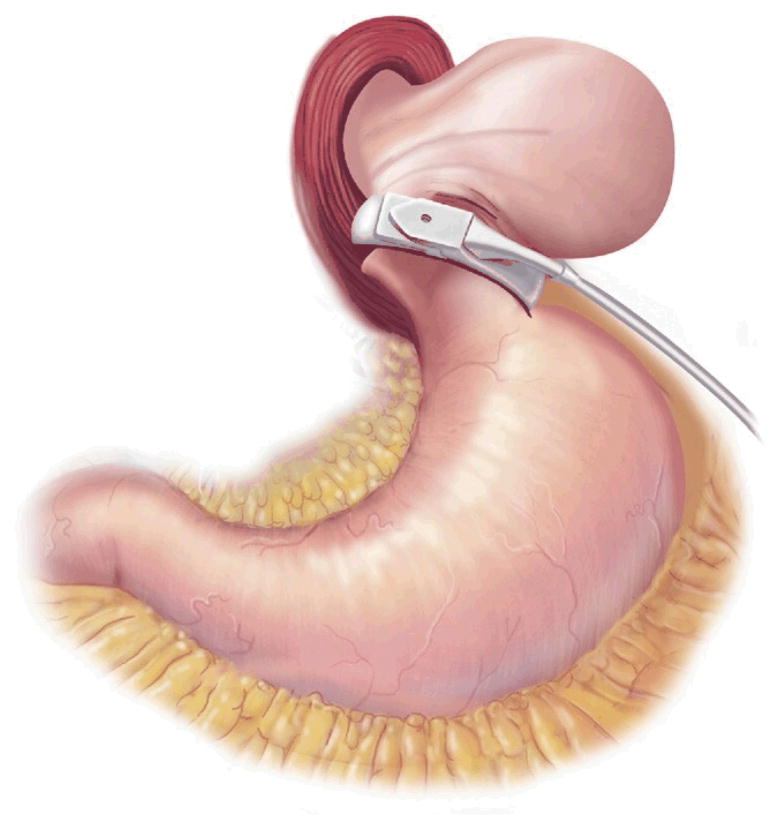

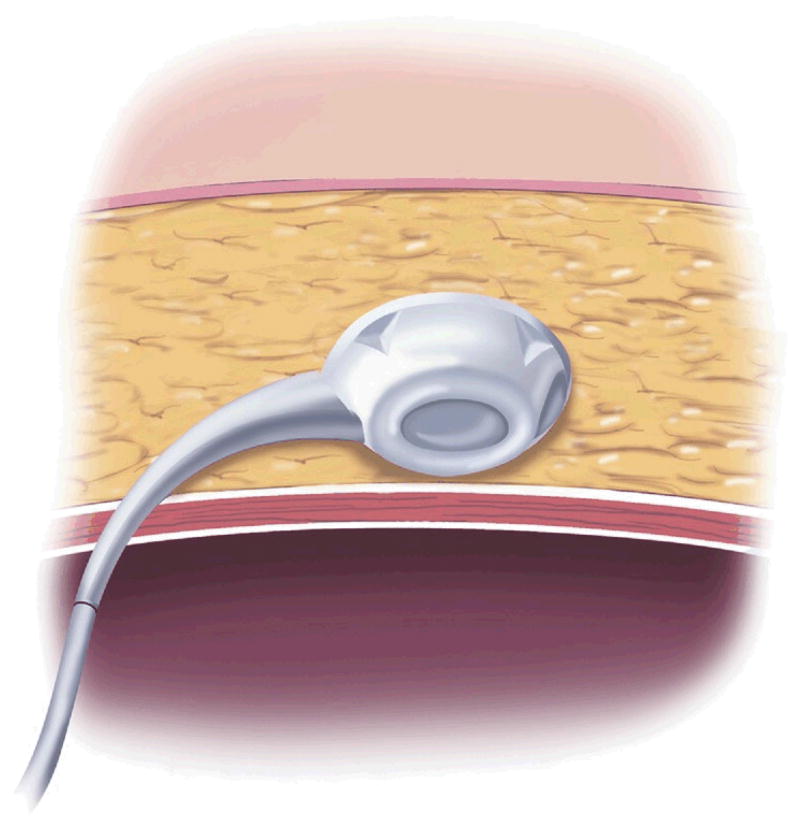

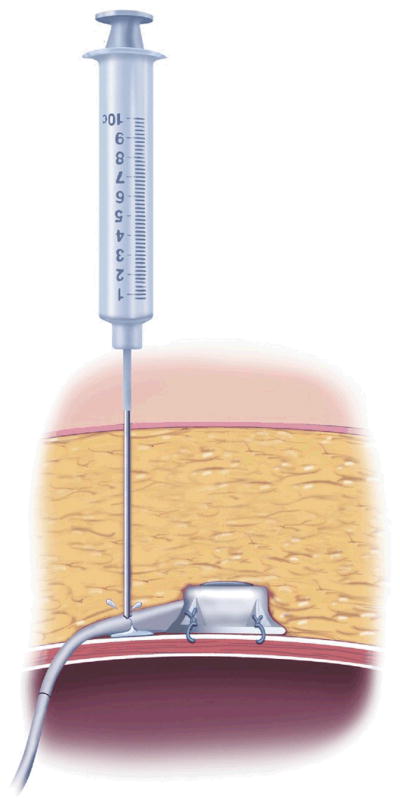

AGB surgery is purely restrictive. It involves placing an inflatable Silastic band around the proximal aspect of the stomach to create a 30-mL gastric pouch [32] (Fig 2). The band attaches via tubing to a port in the subcutaneous tissue, which can be accessed with a Huber needle, much like a chemotherapy port. The port is used by surgeons to inject or withdraw fluid from the band to further restrict or loosen it [33].

Fig 2.

Adjustable gastric band. (Adapted with permission from Jones and colleagues[33], c2007 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

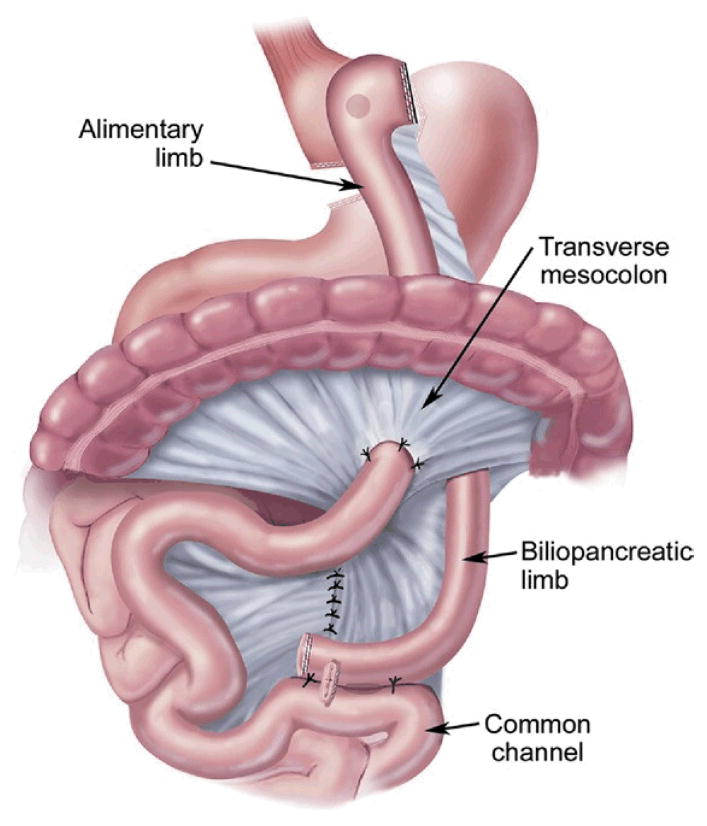

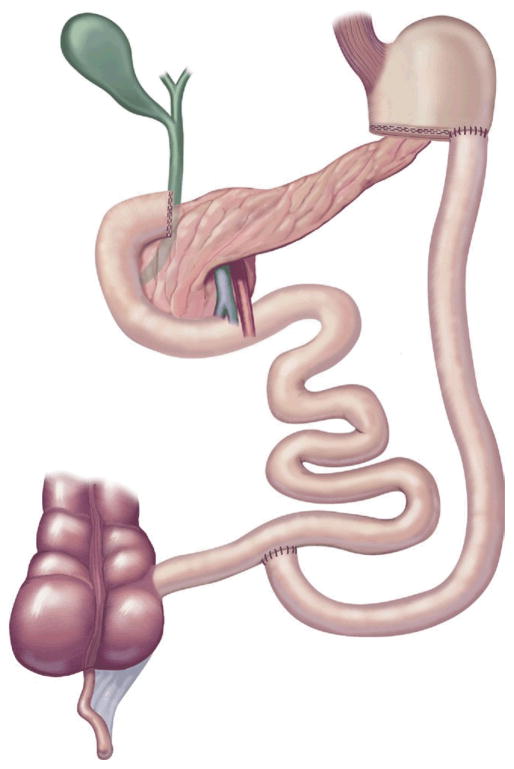

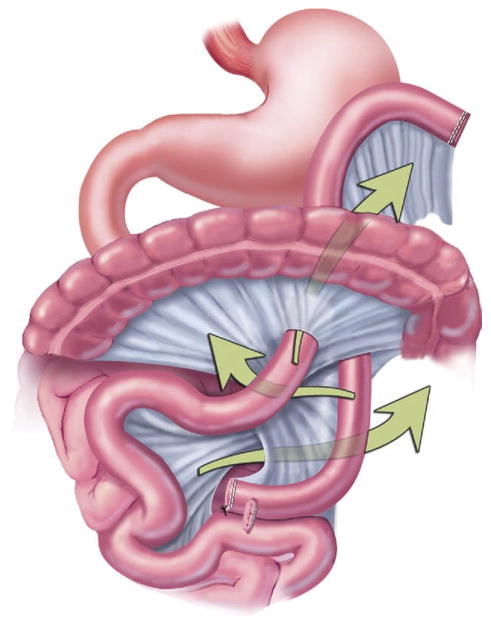

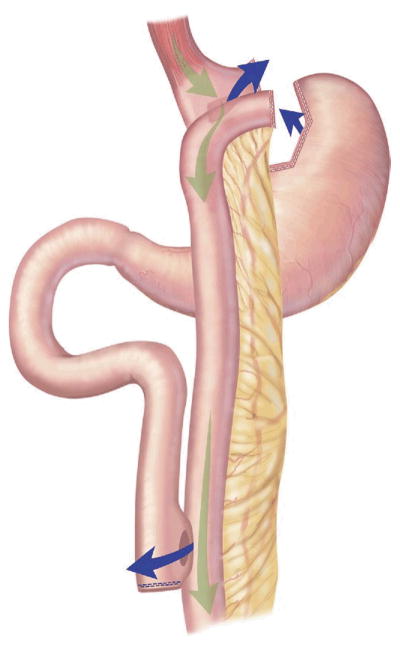

RYGB is a combined restrictive and malabsorptive procedure that entails creating a small 15- to 30-mL stomach pouch and a Roux limb 75 to 150 cm in length that reroutes a portion of the alimentary tract to bypass the distal stomach and proximal small bowel [15]. Connecting the Roux limb to the biliopancreatic limb forms the common channel [34] (Fig 3). Many variations of RYGB are available. The Roux limb can be passed through the transverse mesocolon (retrocolic) or in front of the colon (antecolic). It can also be passed in front of the stomach (antegastric) or behind it (retrogastric). So the procedure can be described as an antegastric, retrocolic RYGB, for instance. Additionally, there have been groups that perform a resectional gastric bypass, where the remnant stomach is removed [35]. No single technique has proven superior in weight loss or overall complications.

Fig 3.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.(Adapted with permission from Jones and colleagues [33], c2007 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.)(Color version of figure is available online.)

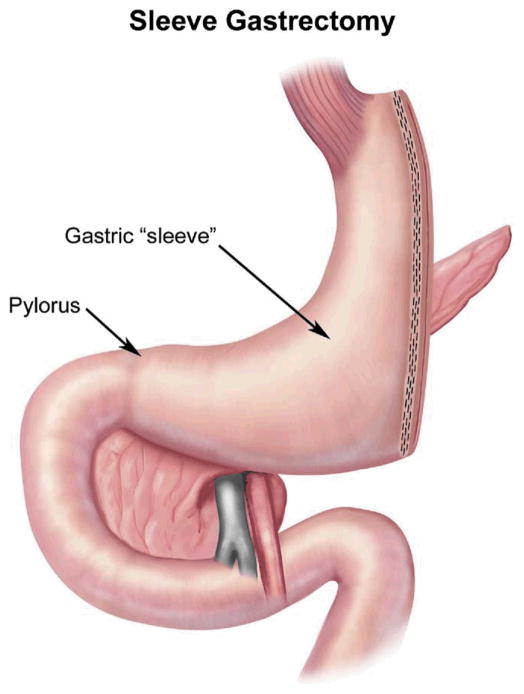

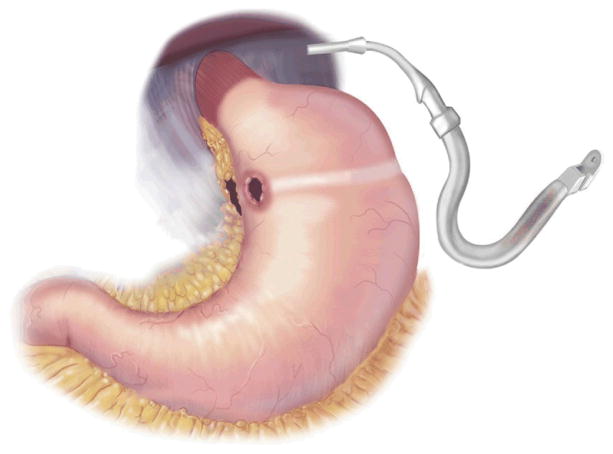

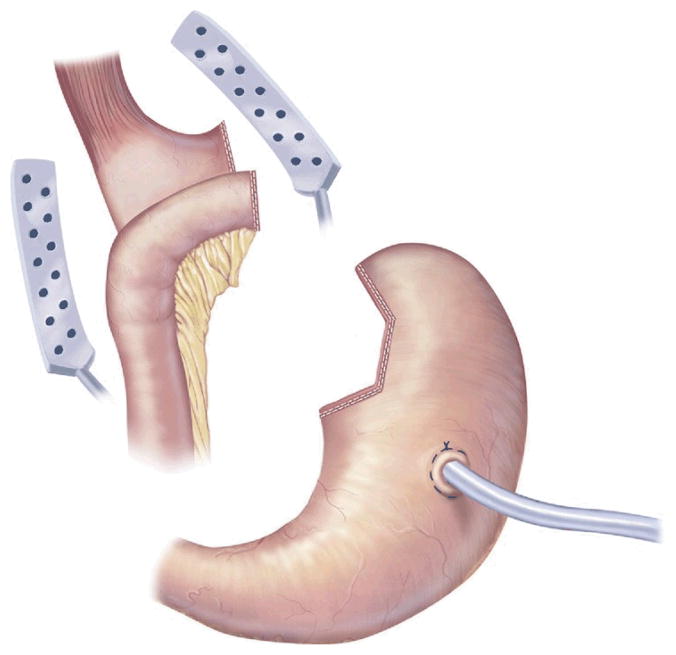

The SG is a restrictive procedure that creates a 100- to 150-mL stomach by performing a partial gastrectomy of the greater curvature side of the stomach [36] (Fig 4). The last 6 to 8 cm of antrum remains intact, and thus, the pylorus is preserved to help prevent gastric emptying problems. At times, an intraoperative decision is made to perform an SG in lieu of a more technically challenging malabsorptive procedure, if the latter is felt to be too dangerous. This choice is usually prompted by adhesions or a body habitus that compromises adequate visualization. After significant weight loss has occurred, the SG can be revised to a BPD-DS or a RYGB to treat the remaining obesity [37]. Unlike AGB, research suggests that hormonal changes occur with SG. Serum levels of ghrelin, a hormone that stimulates appetite, decrease after SG but increase after AGB [38]. For this reason, some surgeons believe that SG may be superior to AGB. However, long-term data on the differences between the 2 approaches are not yet available.

Fig 4.

Sleevegastrectomy. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

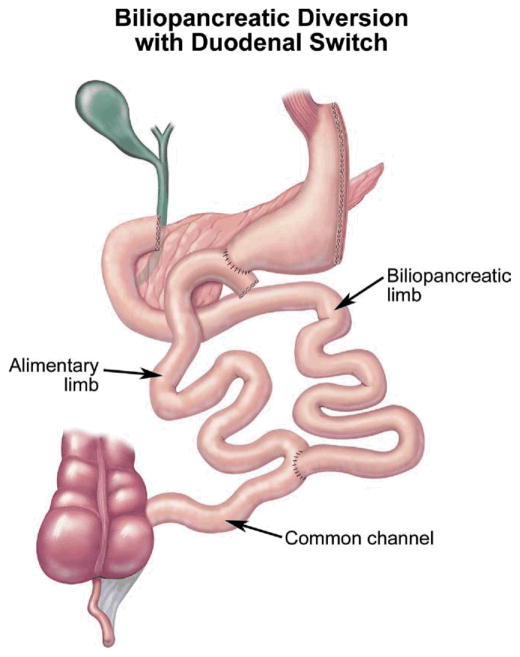

The original BPD or Scopinaro procedure was designed to eliminate the complications from bacterial overgrowth seen with the JIB [39]. The classic Scopinaro procedure was introduced in 1979 and involved: 1) partial gastrectomy, 2) dividing the small bowel halfway between the ligament of Treitz and the ileocecal valve, 3) a Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy between the stomach pouch and the distal small bowel to create an alimentary limb, and 4) a biliopancreatic limb that joins the alimentary limb to create a common channel [40] (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Biliopancreatic diversion. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

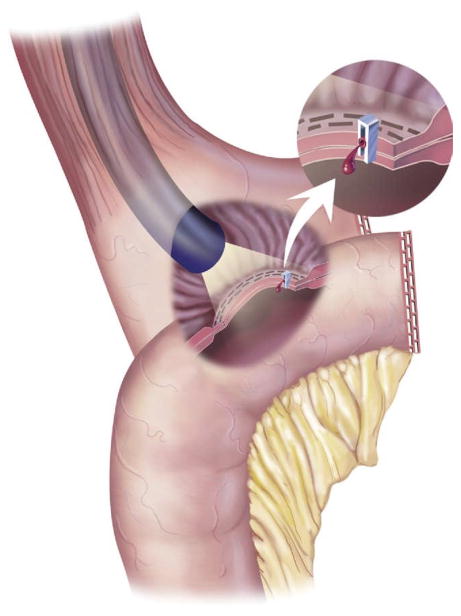

The DS is a modification of the BPD created to control some of the complications of the original Scopinaro procedure [41] (Fig 6). A 150- to 200-mL SG is performed with preservation of the lesser curvature, antrum, pylorus, first portion of the duodenum, and vagal innervation to decrease dumping and marginal ulceration [42]. The duodenum is divided between its first and second portions, and the jejunem is divided halfway between the ligament of Treitz and the ileocecal valve. The alimentary limb is created by anastomosing the distal small bowel limb to the proximal duodenum. The distal duodenum with the remainder of the small bowel is the biliopancreatic limb. It is anastomosed to the distal small bowel to create the common channel [43].

Fig 6.

Biliopancreatic diversion-duodenal switch.(Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

A common channel length of at least 100 cm is generally preferred to decrease metabolic disturbances and the need for revision due to malnutrition [44]. In general, the complications and outcomes after BPD and DS are similar.

VBG involves creating a small stomach pouch by first fashioning a gastrotomy with an end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) stapler in the proximal stomach. A linear stapler is then fired from the gastrotomy to the angle of His to create the lateral edge of the neo-stomach. A ring is placed around the stomach from the lesser curvature to the initial gastrotomy to form the distal aspect of the neo-stomach [39]. The remainder of the stomach remains intact (Fig 7). The use of VBG has fallen out of favor among most weight loss surgeons due to higher rates of complication and inferior long-term weight loss compared with the easier-to-perform AGB [39].

Fig 7.

Vertical banded gastroplasty. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

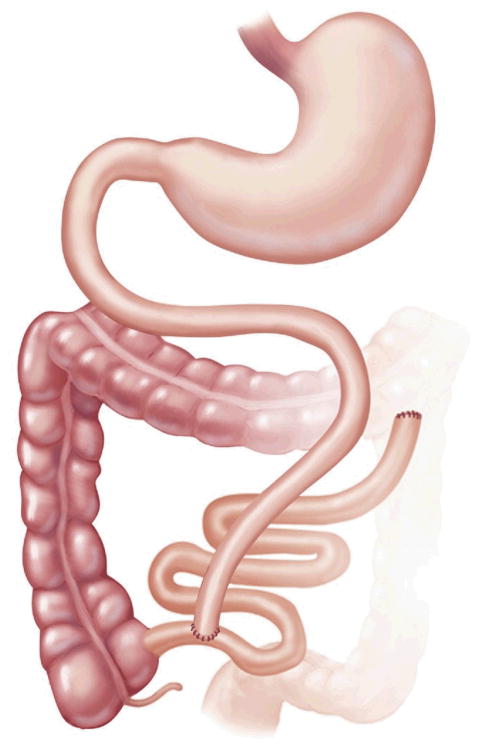

JIB is a purely malabsorptive procedure that connects the proximal jejunum to the distal ileum so that the length of the common channel (or absorptive capacity) is about 100 cm (Fig 8). As mentioned earlier, this approach has been abandoned due to numerous complications related to bacterial overgrowth in the blind limb [39].

Fig 8.

Jejunal-ileal bypass. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Staged Procedures

With the increasing incidence of extreme obesity (BMI >50 kg/m2), more patients are undergoing staged procedures using restrictive operations (AGB or SG) as a bridge to more technically complex malabsorptive techniques, such as a BPD or DS [45]. The latter procedures produce more weight loss than purely restrictive operations. After a few months of significant weight loss, more complex operations are less technically challenging to perform.

Indications for Surgery

In addition to the many different operations available, there is an increasing list of indications for WLS. The original National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria limited WLS to those with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2 or a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities of obesity [46].

Today, more and more adolescents are undergoing WLS as the incidence of obesity increases in this population [47].

A growing body of data also suggests that WLS may be used successfully to treat diabetes in overweight and even normal-weight individuals, and that WLS performed before other kinds of surgeries can improve outcomes. These new indications mean that general surgeons will see more and more WLS patients, increasing the need to be familiar with surgical anatomies, results, and complications. Early recognition of complications is critical. After initial stabilization, post-WLS patients should be referred to their operating surgeon or a full-service WLS program.

Complications

Complications can be divided into 3 major categories: intraoperative, early postoperative, and late postoperative (Table 5). Some apply to all WLS surgeries, whereas others are procedure specific. Complications that are germane to all WLS operations are: DVT/PE, pulmonary/cardiovascular complications, gallstone formation, malnutrition, psychiatric sequelae, failure to lose weight, and death.

Table 5.

General complications of weight loss surgery

| Intraoperative | Splenic injury |

| Trocar injury | |

| Bowel ischemia | |

| Early | Leak DVT/PE |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Pulmonary | |

| Death | |

| Late | Gallstone formation |

| Nutritional deficiencies | |

| Neurologic | |

| Psychiatric | |

| Inadequate weight loss |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

According to national registries, significant progress has been made in the care of WLS patients, with better prevention and control of adverse events [16,48,49]. Efforts to promote continuous improvement are being performed by groups like the Lehman Center [50] and the ACS. The National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), which provides risk-adjusted outcomes, allows centers to compare their results [51]. A meta-analysis of more than 80,000 patients who underwent WLS procedures since 1990 shows an overall perioperative mortality rate of 0.28%, with 0.35% mortality in the first 2 years [48].

Registries track resolution of such obesity-related comorbidities as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea. As mentioned earlier, WLS also decreases overall mortality in obese patients compared with controls [49] (Table 6). However, more work must be done to ensure the best possible outcomes for obese patients. Indeed, future treatment algorithms may differ from those in use today, but for now, WLS remains the most successful and cost-effective way to treat severe obesity.

Table 6.

Benefits of weight loss surgery

| Increased life expectancy |

| Decreased risk of cardiovascular event |

| Resolution of diabetes |

| Resolution of hypertension |

| Resolution of hyperlipidemia |

| Resolution of sleep apnea |

| Resolution of GERD* |

| Resolution of polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Resolution of stress urinary incontinence |

| Improvement of degenerative joint disease |

| Improvement of venous stasis disease Improvement of nonalcoholic hepatitic steatosis Improvement of pseudotumor cerebri |

| Increased fertility |

| Decreased complications from pregnancy and childbirth |

| Improved quality of life |

| Improved outcomes from nonbariatric operations |

| Decreased cancer risk |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass specifically.

Intraoperative Complications

WLS in obese patients is technically challenging. Thick subcutaneous tissue increases the torque on the parts, making fine movements more difficult. Extensive intra-abdominal and visceral fat can obscure visualization and limit exposure. Despite safeguards, intraoperative complications may occur even among highly skilled surgical teams.

Splenic Injury

Minor splenic injury usually consists of a capsule tear, and splenectomy is rarely required. In 1 series of open WLS that included revision procedures, the rate of splenic injury was 3%; only 1 splenectomy (0.5%) was required [52]. Splenic injuries typically occur from excess traction on short gastric vessels used to identify the greater curve side of the stomach’s cardia. In RYGB and SG, the short gastric vessels are commonly divided using electrocautery, the harmonic scalpel, the ligature device, or clips. Retracting downward on the stomach can tear the capsule of the spleen and lead to bleeding.

If bleeding is minimal, direct pressure can be applied laparoscopically with gauze pads. Products like Surgicel promote hemostasis. Any question of continued bleeding should lead to conversion to open surgery. If bleeding cannot be controlled after conversion to the open approach, use of instruments like the argon beam, followed by splenectomy, may be required. Surgeons should not hesitate to convert to an open procedure when there is brisk hemorrhaging from a splenic source.

Bowel Ischemia

Intraoperative bowel ischemia can occur from several different maneuvers during malabsorptive WLS procedures. When the small bowel is divided, intestinal ischemia can result from a division of the mesentery that compromises the mesenteric root. Too much tension on the Roux limb can affect the vascular supply. In addition, the Roux limb can twist if not properly oriented, causing interrupted blood flow. Internal herniation between bypassed segments can lead to ischemia (Fig 9). During repair of mesenteric defects to prevent herniation, an injury to the mesenteric vessels can also result in ischemia.

Fig 9.

Possible internal hernia sites after RYGB. (Adapted with permission from Jones and colleagues [33], c2007 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

If a prior WLS surgery patient presents with signs of severe abdominal pain, hematochezia, and an acute abdomen [53], the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia should be considered. In the long term, mesenteric ischemia may contribute to leaks [54] and stenoses. The stable patient can be transferred to a bariatric team familiar with the surgical anatomy. For the unstable patient, prompt surgical intervention should include examination for ischemia, internal hernias, and adhesions.

Trocar Injury

It can be very difficult during laparoscopic procedures to obtain a pneumoperitoneum, and injuries can occur during placement of the Veress needle or the ports. Damage to the aorta and iliac vessels can be life threatening, but the overall incidence of such injuries is quite low, ranging from 0% to 0.16% [55,56]. Schwartz and colleagues described the use of a Veress needle placed in the left upper quadrant near the costal margin in the midclavicular line to obtain the pneumoperitoneum before placing the trocar. Of 600 severely obese patients, they reported only 1 incident, a colonic serosal injury, where the mucosa was not violated. Sub- and intraomental air occurred, but was not of clinical significane [55]. Others using an optical view bladeless trocar without a pneumoperitoneum report no mortality [56]. A Cochrane review of 17 randomized controlled trials comparing pneumoperitoneum techniques in 3040 patients concluded that there was no statistical difference in complication rates between closed, open, or optical view insertion techniques for establishing a pneumoperitoneum [57]. Obese patients, though, were not analyzed separately, and there are no randomized controlled trials comparing the different techniques in patients with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Transabdominal ultrasound has also been used in patients with previous abdominal operations who are undergoing RYGB. Kothari and colleagues found that preincision outcomes from radiology correlated with the surgeon’s intraoperative findings [58]. However, this technique has never been compared with other approaches for avoiding trocar associated injury. When performing nonbariatric procedures in obese patients, Jones and colleagues favor use of the left upper quadrant Veress needle placement to gain the pneumoperitoneum and optical view for trocar entry [33]. However access is achieved, the surgeon should routinely inspect the area underneath the insertion site for bleeding or intestinal injury. Uncontrolled bleeding requires prompt conversion to an open procedure to treat the injury.

Early Postoperative Complications

Leak

The overall leak rate after WLS is 0.0% to 5.6% [53]. Leaks are the most dreaded complication due to their association with life-threatening sequelae. Gonzalez and colleagues reported a mortality of 15% in patients with leaks versus 1.7% in those without them [54]. Interestingly, randomized controlled trials comparing open RYGB to laparoscopic RYGB do not show a difference in leak rates [28]. Leaks are more apt to occur with either technique if the patients are male and over the age of 50 [59]. In laparoscopic BPD-DS, the leak rate ranges from 0.4% to 0.9% [41]. No randomized trials have compared leak rates in open versus laparoscopic BPD-DS. SG leak rates range from approximately 0% to 1.4% [60]. In purely restrictive procedures (eg, AGB and VBG), they vary from 0.0% to 0.05% [49,61].

It is important to note that leak rates increase greatly in all revision operations. Revision surgery is the most important predictor of leaks, with a rate of 18% to 35% [62,65]. Leaks may occur as a result of technical factors such as ischemia, tension [54], or stapler misfire. Surgeons who have performed less than 75 cases seem to have a higher likelihood of developing a leak complication during laparoscopic procedures [28].

Several studies have evaluated techniques used to prevent leaks. Oversewing of the staple line using a continuous suture may reduce gastrogastric fistula formation [66]. Bovine pericardial strips may reduce the incidence of staple line bleeding, but their effect on leak rate is questionable [67]. Fibrin sealant has yet to prove a decrease in the incidence of leaks [54]. Although some subclinical leaks have been managed nonoperatively [68], prompt recognition of the clinical signs, evaluation, diagnosis, and management can be life saving. Leaks are discussed in more detail in the RYGB section.

Deep Venous Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the most common cause of death in the perioperative period, accounting for 50% of all such deaths [69]. The rates of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) after WLS are similar between open and laparoscopic techniques: up to 1.3% and 0.4%, respectively [70]. The rate of PE after open WLS ranges from 0.25% to 3%; after laparoscopic procedures, it ranges from 0.7% to 2.4% [70]. In AGB surgery, PE is also the most common cause of death [71]. Melinek and colleagues found microscopic evidence of DVT in 80% of gastric bypass patients, although only 20% were diagnosed clinically [72]. In that obesity induces a prothrombotic state, WLS candidates should be considered at high risk for the development of venous thromboemboli [73].

Unfortunately there are no quality data identifying the best forms of DVT/PE prophylaxis, and the practice of experienced weight loss surgeons varies widely [74]. Unless there are other clinical concerns, the Lehman Center report recommends the use of anticoagulants with sequential compression devices [13]. For patients at increased risk for DVT/PE, extended prophylaxis should also be considered [13].

Another approach is the use of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters in patients who are at the highest risk for a DVT or PE (ie, those with a history of a venous thrombolic event or venous stasis, poor ambulation, pulmonary hypertension, severe sleep apnea, a BMI >60 kg/m2, or central obesity) [75]. In a series of 330 such patients, those who had IVC filters placed preoperatively were less apt to develop a PE than those who did not (0.63% vs. 2.94%) [76]. It is important to note that for patients who have undergone WLS, their risk of DVT/PE is likely to remain elevated despite substantial weight loss, especially if their preoperative BMI was greater than 50 kg/m2. Unless there are contraindications, postoperative WLS patients who remain severely obese should receive anticoagulants and sequential compression devices during general anesthesia. Consultation with a hematologist or vascular surgeon may be helpful when treating high-risk patients.

Cardiovascular Complications

The incidence of an ischemic event after WLS is less than 1% [53]. Fatal cardiovascular events can range from 12.5% to 17.6% of all perioperative deaths [77], making them the second most common cause of postoperative mortality [71]. Between 1 and 6 months after WLS, cardiovascular complications cause 33% of all such deaths [22]. Cardiovascular risk decreases over time [78], but remains high immediately after operation.

Pulmonary Complications

Atelectasis occurs at a rate of 8.4% after laparoscopic WLS [79], but the incidence of other pulmonary complications is approximately 4.5% [80]. Of all perioperative deaths, respiratory failure accounts for an estimated 11.8%, making it the third most common cause of mortality [77]. Persistent vomiting or reflux after WLS can be due to stomal obstruction or stenosis, and such patients are at long-term risk for aspiration pneumonia [81]. Those on Medicare, with chronic lung disease, men, and patients over age 50 have the highest incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications [82].

Mortality

Even among well-selected patients, the rate of mortality after the most commonly performed WLS procedures ranges from 0% to 2.5%. One meta-analysis of RYGB, AGB, VBG, and BPD found no statistically significant difference in mortality rate [49]. However, another study indicated that AGB had the lowest overall death rate, at 0.01%, and BPD the highest, at 0.8% [77]. Several recognized risk factors for death after WLS include male gender, age greater than 65, and surgeon inexperience.

Data show that low-volume hospitals with fewer than 50 cases per year have the highest rate of adverse outcomes [83]. Odds of death at 90 days are 1.6 times higher for patients whose surgeons perform less than themedian volume of bariatric procedures [84]. Flum and colleagues found that within the first 30 days, patients older than 65 years had a 4.8% death rate, with older men having a higher risk of 3.7% [84]. The most common causes of death after WLS are PE, followed by myocardial infarction, leak, and respiratory failure [77].

Late Postoperative Complications

Complications can occur from several weeks to several years after WLS. Physicians should be wary of abdominal pain, extremity weaknesses, rashes, psychiatric complaints, or inability to tolerate a diet. WLS patients require lifelong follow-up and multidisciplinary care with a team that includes a nutritionist, psychiatrist, and other consultants [15].

Gallstone Formation

The incidence of gallstone formation is 27% to 38% after RYGB [53]. Several factors, including decreased gallbladder emptying, contribute to development of stones. Surgical disruption of hepatic branches of the vagus nerve and altered enteric stimulation can also result in biliary dyskinesia and bile stasis [85]. Gallstones also tend to form as a result of postoperative changes in gallbladder mucin production, calcium concentration, and the bile salt/cholesterol ratio [86,87]. For these reasons, many weight loss surgeons perform a concomitant cholecystectomy, especially if gallstones are present during an RYGB. In those without preoperative gallstones, use of ursodiol for 6 months after RYGB can reduce the incidence of gallstone formation from 32% to 2% [88].

The use of prophylactic cholecystectomy remains controversial and may not be reimbursed by third party payers. If prophylactic cholecystectomy has not been performed, patients with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain should be evaluated for gallstones and common bile duct stones. Choledocholithiasis, in particular, poses a problem with the divided pouch and resultant inability to rely on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for diagnosis and treatment.

The incidence of gallstone formation in AGB and VBG is similar to that in RYGB. One study shows that 21.4% of patients develop gallstones after laparoscopic AGB [85]. These patients lost more than 1.7% of their weight per week [85]. One single-institution, randomized, double-blind, prospective trial compared the incidence of gallstone formation with and without the use of ursodiol for 6 months after AGB and VBG. With ursodiol, the rate of gallstone formation fell from 22% to 3%. The authors concluded that it should be used for gastric restrictive as well as malabsorptive or combination procedures [89].

Unfortunately, most insurance companies do not cover expenses associated with routine use of ursodiol after purely restrictive procedures. Alternatively, a cholecystectomy can be performed a few weeks before WLS in patients with preoperative gallstones. In theory, doing so will reduce the odds that spilled bile will infect the band. Data show the incidence of cholecystectomy after SG ranges from 0.007% to 14% [90–92].

However, it is unknown whether patients were taking postoperative ursodiol. Recommendations call for SG patients to do so for 6 months after their operations [36].

In cases of choledocholithiasis in RYGB or BPD-DS patients, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should be used to evaluate the common bile duct. If stones are detected and the duodenum cannot be accessed via ERCP or transgastric ERCP, open common bile exploration is usually necessary. Anecdotally, we have seen several post-RYGB patients with ampullary stenosis and right upper quadrant discomfort, dilated hepatic ducts, and elevated liver enzymes, and no stones with ultrasound or MCRP; yet choledochojejunostomy produced significant improvement. Ultimately, any WLS patient with postoperative right-sided abdominal or epigastric pain should be evaluated for gallstone disease and appropriately treated.

Nutritional Deficiencies

Many obese persons undergoing WLS have preoperative nutritional deficiencies [93] that can be exacerbated by malabsorptive procedures. Even patients undergoing purely restrictive procedures are at risk for nutritional deficiencies due to poor eating habits as well as food intolerances and eating restrictions [94,95]. This heightened risk underscores the importance of lifelong follow-up of WLS patients, and the need for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for nutritional-related abnormalities. Nutritional deficiencies can occur in up to 44% of patients several years after operation [93]. The incidence of anemia can be as high as 74%, especially among women of childbearing age. Premenopausal women are also likely to have poor iron status due to menstruation [96].

Vitamin B12/Folate

After WLS, vitamin B12 deficiency results from the body’s inability to separate the vitamin from protein foodstuffs, and failure to absorb free vitamin B12 [93,97,98]. Patients may present with weakness and fatigue from megaloblastic anemia, parasthesias, peripheral neuropathy, and demyelination of the corticospinal tract and dorsal columns [99]. After RYGB and BPD, this can occur in 12% to 33% of patients [100]. The deficiency can be corrected with 350 J.g/day of vitamin B12. Some patients do very well with monthly subcutaneous injections [101]. Very few require parenteral administration (2000 J.g/mo) [101].

Folate deficiency has been reported in 38% of patients after RYGB [102]. Treatment is critical for those who intend to become pregnant. Folate deficiency may lead to neural tube defects in infants [103]. Supplementation with 400 J.g/day, an amount contained in most multivitamins [101], is generally recommended. Vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies rarely manifest clinically when patients are compliant with multivitamin use and nutrition follow-up.

Maintaining vitamin B12 and folate levels helps suppress rising homocysteine levels in WLS patients who already have, or are at risk for, metabolic syndrome. Homocysteine is an amino acid with direct toxic effects on vascular endothelium [104], and is recognized as an independent risk factor for CVD and thromboembolic events [105]. Several studies have demonstrated a rise of homocysteine above 10 J.mol/L in patients after WLS, and have attributed it to a decrease in vitamin B12 and folate [106–109].

Higher folate and vitamin B12 concentrations are needed to maintain normal homocysteine levels [97]. To keep them at less than 10 J.mol/L [106], Dixon and colleagues recommend a serum folate level of approximately 15 ng/mL and a vitamin B12 serum level greater than 600 pg/mL.

Iron

Iron deficiency results from 2 main mechanisms. With purely restrictive procedures, there is less gastric acid secretion to reduce dietary iron into the ferrous state required for absorption [93,110]. In malabsorptive procedures, bypassing the duodenum and proximal jejunem eliminates the 2 main areas of iron absorption [93]. Iron deficiency can be seen in up to 32% [111] of patients who undergo restrictive procedures, and in 14% to 52% of those who have malabsorptive WLS [100].

Patients typically present with diminished exercise and work tolerance, impaired thermoregulation, immune dysfunction, gastrointestinal disturbances, and cognitive impairment. They can also present with pica. Kushner and colleagues published a report of 2 RYGB patients who developed pica so severe, they routinely awoke in the middle of the night to satisfy their ice cravings [112]. This symptom resolved with iron replenishment [112].

Iron deficiency is usually treated with 650 mg of daily oral ferrous sulfate tablets [110]. Vitamin C helps promote iron absorption [110]. Additionally, pro-phylactic oral iron supplements are recommended for premenopausal women who undergo RYGB, especially if they are already anemic[97].

Thiamine (B1)

Thiamine deficiency (beriberi) can be due to decreased duodenal absorption, but more often, it is a consequence of persistent vomiting [113].

In WLS patients, it can occur early in the postoperative period, when weight loss is most rapid, or after prolonged vomiting caused by a variety of factors [114]. Bacterial overgrowth seen after some BPD and JIB procedures is also associated with thiamine deficiency [115]. Because thiamine is involved with carbohydrate metabolism, its reserves can be depleted in WLS patients on high carbohydrate diets [116].

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS)—a neurologic derangement characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, nystagmus, and mental confusion—is an increasingly recognized complication of thiamine deficiency. When brought on by dietary deficiency [114], it is most commonly seen in alcoholics. It has also been reported in patients suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum, AIDS, Crohn’s disease, and those receiving total parenteral nutrition (TPN) [114].

In WLS patients, WKS is associated with polyneuropathy and encephalopathic manifestations [117]. Given the lack of biochemical, radiologic, and histologic evidence, this complication can be difficult to diagnose [114]. However, rapid recognition and intervention are critical. Delay in thiamine replenishment increases the risk of long-term and even irreversible problems [118].

When thiamine deficiency is suspected, replacement should be quick and continuous until the rapidity of weight loss subsides or the cause of the prolonged vomiting is treated. In general, oral repletion with 50 to 100 mg of thiamine up to 3 times per day should correct the deficiency, but parenteral or intramuscular administration may be necessary in patients with hyperemesis [119]. Such therapy should last 7 to 14 days, then be continued orally [116] WLS patients should continue to receive a multivitamin. Most of these contain amounts of thiamine that exceed the recommended 1 mg/day for men and 0.8 mg/day for women [101].

Protein

Protein deficiency is defined as serum albumin below 3.5 g/dL [93]. It can occur in 18% of BPD patients [120], and 13% of those who have RYGB [121]. However, it is rare in those with Roux limbs shorter than 150 cm [122]. Hospitalization for severe protein deficiency can occur in 3.7% of BPD patients, and revision surgery in 6% [123]. Those with a common channel only 50 cm long have the highest rates of protein deficiency [121].

Patients with protein malnutrition can present with excessive weight loss, severe diarrhea, hyperphagia, muscle wasting (marasmus), and edema [124]. Approximately 3 weeks of TPN can correct the acute problems [125], although dietary counseling to increase protein intake can help prevent recurrences [126]. In general, WLS patients should have 1.2 g of protein/kg/day postoperatively [127].

Calcium and Vitamin D

Several studies show reduced bone mineral density in patients years after WLS [128–132]. Calcium is absorbed in the duodenum and proximal jejunum with malabsorptive procedures, making patients prone to calcium deficiency [93]. Conversely, vitamin D is absorbed in the jejunum and ileum. The condition is exacerbated by defective absorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins [93]. Low serum calcium levels prompt increased parathyroid hormone production to induce release of calcium from bone, thereby increasing the long-term risk of osteoporosis [93].

Patients present with myalgias, arthralgias, muscle weakness, and fatigue—symptoms that may occur up to 12 years after gastric bypass [133].

Coates and colleagues found a reduction of bone mineral density 9 months after laparoscopic RYGB despite increased dietary calcium and vitamin D, and normal levels of parathyroid hormone and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [128]. The incidence of calcium deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism can be as high as 69% 4 years after BPD, with the prevalence of clinically significant hyperparathyroidism up to 27% [134].

Calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D should be monitored regularly in WLS patients. Calcium supplementation of 1.2 to 1.5 g/day and ergocalciferol dosing of 400 IU daily are recommended [135]. Calcium levels are maintained at the expense of mobilization from bone. Thus, it is important to note that secondary hyperparathyroidism manifests as a late consequence of calcium deficiency [136]. Treatment may require daily calcium dosages in excess of recommended amounts to prevent it [137,138]. In that calcium carbonate requires bioavailability of stomach acid, calcium citrate should be used to help correct the deficiency [93].

Other Fat-Soluble Vitamins: A, E,K

Shorter common channels delay mixing of fat with pancreatic enzymes and bile salts, decreasing fat absorption and increasing the risk of fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies after malabsorptive procedures [93]. As little as 32% of dietary fat is absorbed after BPD [139]. Slater and colleagues reported respective deficiencies in vitamins A, D, and K of 69%, 4%, and 68% 4 years after malabsorptive WLS [134]. Brolin and colleagues found a 10% incidence of vitamin A deficiency after RYGB [122].

A few case studies note vitamin A deficiency leading to night blindness [140]. In 1 report, it caused xerophthalmia, nyctalopia, and eventually, visual deterioration to legal blindness after RYGB [141]. Deficiencies in vitamins E and K have no significant clinical effect [125].

Zinc

Zinc deficiency is seen mainly after BPD [134], but can also occur after purely restrictive procedures due to poor dietary intake [142]. It can cause alopecia, but in general, clinical manifestations are uncommon [93] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Nutritional deficiencies

| Deficiency | Symptoms | Incidence | Prophylactic treatment | Deficiency treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12/Folate [101] | Megaloblastic anemia, parasthesia, peripheral neuropathy, demyelination of the corticospinal tract and dorsal columns | 12–38% | 350–400 J.g/day orally | 2000 J.g/mo IM or IV |

| Vitamin B1 thiamine [119] | Hyperemesis, Wernicke- Korsakoff syndrome, peripheral polyneuropathy | 0.8–1.0 mg/day | 50–100 mg three times per day for 7 to 14 days | |

| Vitamin A [97,134] | Night blindness, xerophthalmia, nyctalopia, blindness | 10–69% | Most MVI | |

| Vitamin D/Calcium [133] | Myalgias, arthralgias, muscle weakness, fatigue, decreased bone mineral density, hyperparathyroidism | 48–69% | 1.2–1.5 g/day calcium citrate, 400 IU/day ergocalciferol | |

| Vitamin E [134] | 4% | Most MVI | ||

| Vitamin K [134] | 68% | Most MVI | ||

| Iron [110] | Microcytic anemia, decreased exercise tolerance, immune dysfunction, impaired thermoregulation, GI disturbances, cognitive impairment, pica | 14–52% | 650 mg/day of vitamin C containing iron supplement | |

| Protein [124] | Excessive weight loss, diarrhea, marasmus, edema, hair loss | 13–18% | 1.2 g/kg/day | TPN |

| Zinc [134] | Alopecia | Rare | MVI with zinc |

MVI, multivitamin; GI, gastrointestinal; TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

Neurologic Complications

The prevalence of neurologic complications after WLS ranges from 5% to 16% [143]. Many symptoms result from nutrient and vitamin deficiencies, but not all can be directly attributed to malnutrition. Problems often start to manifest years after WLS, and are often misdiagnosed. Over a 10-year period in 1 institution, Juhasz-Pocsine and colleagues found 26 patients whose neurologic conditions could be related to WLS [144]. The average time to onset of symptoms was 6.6 years. Conditions were grouped into 5 major categories: encephalopathy, optic neuropathy, posterolateral myelopathy, acute polyradiculopathy, and polyneuropathy. Several patients fell into more than one neurologic category; all were treated for nutritional deficiencies.

One patient had a disabling posterolateral myelopathy that failed to respond to nutrition supplementation. Full recovery followed RYGB revision that shortened the bypassed limb of jejunem by 70 cm. In all, 42.6% of patients had a persistent neurologic deficit 10 years after surgery. This suggests that their neuropathies were either not caused by malnutrition, or that the deficiency led to irreparable damage [144].

Thaisetthawatkul and colleagues compared 435 WLS patients to 126 open cholecystectomy patients and found that the rate of peripheral neuropathy was higher in those who had WLS [145]. This group had an abnormal amount of inflammation on nerve biopsy. The authors concluded that no specific nutritional deficiency could account for the neuropathies. However, some patients had an altered immune response after WLS [145]. Multivitamin supplementation, close follow-up, and ongoing patient education are essential to prevent, identify, and treat nutritional and neurologic complications. WLS patients should see a nutritionist once per year.

Psychiatric

Most overweight patients do not have a psychological illness. However, 27.3% to 41.8% [146] of severely obese patients have axis I disorders, and up to 25% have axis II disorders [147]. Depression is the most common axis I disorder, prevalent in approximately 66% of WLS candidates with an axis I disorder [148]. Anxiety disorders [147], binge eating [149], and substance abuse [150] may also be present. Severely obese patients may suffer from somatization, negative body attitude, and low self-esteem [151]. The most common axis II disorders are passive-aggressive, schizotypal, histrionic, and borderline personality disorders [150]. Psychiatric issues must be addressed before and after surgery, and are part of the lifelong multidisciplinary approach to obesity management.

Mental illness is not an absolute contraindication to WLS; no evidence shows that it is a negative predictor of weight loss [6]. However, active psychosis and severe mental retardation (IQ <50) are typically contraindications if the patient cannot demonstrate understanding of the procedure or comply with postoperative diet, exercise, and follow-up instructions [152].

In addition to weight loss and control of comorbidities, one of the goals of WLS is to improve quality of life (QOL). Patients suffering from postsurgical depression lose less weight and have a lower QOL [153]. They may find that their lives do not dramatically improve once their obesity is treated. For some, underlying emotional problems were not all due to their obesity [154]. Data show that the psychosocial benefits of WLS may decline after several years, returning patients to their preoperative state [154]. A thorough assessment is needed before WLS, and those with psychopathologies are encouraged to participate in a support group or follow-up with their therapists after the WLS.

Depression

Depression and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric illnesses in the severely obese [155]. Patients with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2 are 5 times more likely to have had a major depressive episode within the past year than their less obese counterparts [156]. During assessment, the mental health expert needs to distinguish between endogenous and obesity-related depression and determine the relationship, if any, between the 2 diseases. Although most depression is relieved with weight loss, a subgroup of patients remains depressed after operation [157]. Indeed, the suicide rate is higher than expected after WLS [158,159]. Primary care providers and other members of the multidisciplinary treatment team need to be aware of psychiatric illnesses, and make certain that appropriate referrals for treatment are arranged before and after WLS.

Eating Disorders/Binge Eating

Binge eating is present in up to 30% of WLS candidates [160], and continues in up to 46% of these patients after operation [149]. Preoperative binge eating is not a negative predictor for adequate weight loss, but postoperative binging undermines it [150]. Grazing is a risk factor for binge eating in the postoperative setting [161]. After WLS, approximately 23% of patients will have some form of eating disorder that may reduce weight loss or lead to weight regain [162]. In general, studies show that patients have better and more flexible control over their eating after WLS [163].

However, all patients are encouraged to participate in a bariatric program that includes nutritional education and counseling to help combat eating disorders. In summary, obesity-related psychological issues may improve after weight loss, but patients often face new psychological challenges or return to preoperative symptoms as body image changes. The Lehman Center report recommends that mental health assessment should be a standard part of multidisciplinary care. Inquiring about psychiatric problems and making appropriate referrals to mental health professionals is important to the overall health and well-being of patients.

Procedure-Specific Complications

Restrictive Procedures

The following sections will focus on procedure-specific complications. Restrictive operations (eg, AGB, VBG, SG) work by limiting the amount of food patients can ingest at any one time. Restrictive WLS tends to be better tolerated in the immediate postoperative period with less mortality than malabsorptive procedures, but overall long-term morbidity may be higher.

Adjustable Gastric Band

AGB is the second most commonly performed WLS procedure in the United States today and the most common worldwide [164]. In general, patient satisfaction with gastric banding is high, and the early postoperative complication rate is low. Patients can expect to lose 50% to 60% of excess weight and resolve 60% to 80% of comorbid illnesses [165]. Total short-term morbidity is approximately 1.2%, with a 0.05% mortality rate [95]. In a review of 9682 AGB patients, PE caused most deaths that occurred in the first 30 days after operation [71]. Late complications can range from as low as 10% to as high as 40%, with 21.7% to 35.5% of patients needing revision or removal of either the band or the port [165,166] (Table 8).

Table 8.

Complications of adjustable gastric band

| Rate of occurrence (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gastric prolapse: anterior | 1–22 [169] |

| Gastric prolapse: posterior | 2 [172] |

| Esophageal/pouch dilation | — |

| Gastric erosion | 1 [173] |

| Band leakage | 4.4 [174] |

| Tubing/port leakage | 0.4 [174] |

| Acute stomal obstruction | 14 [167] |

| Port flip | — |

| Port infection | 0.3–9 [178] |

| Inadequate weight loss | 40 [165] |

Three technical advances can reduce the rate of complications associated with AGB placement. First, use of the pars flaccida technique can prevent band slippage and prolapse by limiting retrogastric dissection and adding a gastrogastric imbrication [33]. Second, removal of the esophageal fat pad may reduce the incidence of acute stomal obstruction [167]. Third, concomitant repair of a hiatal hernia is known to reduce the incidence of band slippage, pouch dilation, and the need for reoperation [168].

Acute Stomal Obstruction

Acute stomal obstruction has been reported to occur in as many as 14% of patients and is due to an overly tight band [169]. Causes include tissue edema, hematoma, or excess tissue incorporated under the band as it is placed around the proximal stomach [169]. Patients present in the first few days after surgery with oral (PO) intolerance that includes secretions, along with nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain [169]. Diagnosis is confirmed by an upper gastrointestinal series of X-rays with no passage of contrast past the band [169]. Removal of the esophageal fat pad can reduce the rate of obstruction from 8% to 0% [167]. Acute stomal obstruction may be managed by waiting 3 to 6 days for the edema to resolve, or by prompt surgical intervention [169].

AGB patients frequently complain of an inability to tolerate food and liquids in the morning—a sensation that dissipates over the course of the day. This is likely due to edema that may occur when patients are supine. Over time, the swelling resolves and passage through the band becomes easier. This is normal after AGB placement and should not be confused with acute stomal obstruction [170]. As patients lose weight, the band may become looser and the sensation may cease.

Those who undergo a recent band fill may also experience symptoms similar to acute stomal obstruction. An upper gastrointestinal series is not needed; the history of a fill within the last 72 hours associated with acute onset of nausea, vomiting, and PO intolerance should be sufficient to make the diagnosis. Since many WLS patients may live a distance away from their bariatric surgeon, patients will sometimes present at the nearest emergency room for relief of their symptoms. If possible, they should be transferred immediately to a bariatric center or admitted for intravenous hydration while arranging follow-up with their weight loss surgeon or the nearest WLS center. If transfer is not possible, or treatment delay will cause undue distress, the port may be accessed to unfill the band.

Port access should be performed under sterile conditions using only a Huber needle. The ports used in most band systems are not unlike those used to access long-term central venous catheters, such as port-a-caths. Use of a typical hollow core needle will damage the port and cause a leak in the band system. If the physician cannot feel the port or is unsure of its location, access can be performed under fluoroscopy. It is reasonable to remove all of the fluid from the port when patients present with acute symptoms. They can then follow up with their weight loss surgeon for a subsequent refill. Once the fluid is removed, patients should be given a glass of water to drink. They will note right away if they are able to swallow or if they are still overly restricted. Failure to immediately improve after an unfill should signal a more serious problem, such as a prolapse.

Band Slip/Anterior Gastric Prolapse

The incidence of band slippage varies widely and occurs anywhere from 1% to 22% of cases [169]. The band moves cephalad and creates an acute angle with the stomach pouch and the esophagus [169], causing an obstruction (Fig 10). Patients complain of poor tolerance to oral intake and of reflux symptoms that are worse when supine. Ironically, they may actually gain weight because they can only tolerate soft and liquid foods (eg, candy and ice cream) that can easily slide past the acute angle created by the band. This complication usually requires replacement of the band or conversion to another weight loss operation.

Fig 10.

Gastric prolapse. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Band Slip/Posterior Gastric Prolapse

With posterior gastric prolapse, the stomach body migrates upward, displacing the band caudally and creating a large new pouch [169]. Posterior gastric prolapse is more common than anterior prolapse [171]. Patients present with symptoms of obstruction: reflux, food intolerance, and epigastric pain. They may also have weight gain. Diagnosis is made by upper gastrointestinal series that show the posterior displacement of the body of the stomach above the band, perhaps best seen on a lateral view [169]. The band will angle downward.

Use of the pars flaccida technique has reduced the incidence of this complication from 24% to 2% [172]. Although generally not an emergency, it requires surgical removal of the band. Transfer to a weight loss surgeon should be expedited. Left untreated, patients are at risk of gastric strangulation (patients present with acute severe epigastric pain and vomiting). It is important for the emergency room physician and general surgeon to distinguish between gastric prolapse and gastric strangulation.

Band Erosion

Band erosion occurs in approximately 1% of cases [173]. It may be caused by gastric wall ischemia, pressure necrosis, or possibly an infection that allows the band to erode through the stomach wall [173] (Fig 11). This complication can cause loss of band restriction and weight gain, peritonitis, abscess formation, port-cutaneous fistula, and most commonly, a port-site infection [173]. Diagnosis of the erosion can be made by upper gastrointestinal series or endoscopy [173]. Treatment is removal of the band and primary closure of the stomach ulcer [173].

Fig 11.

Gastric erosion. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Band and Balloon Leakage

A band that leaks saline provides no restriction. Patients complain of the lack of restriction despite good results with a prior fill [174]. The band can be tested by emptying it with a syringe to find out whether significantly less or no fluid returns on aspiration. The leak can be confirmed radiographically by attempting port fill under fluoroscopy and noting if the contrast leaks out of the tubing or balloon [175].

Disruption of the inflatable portion of the band is rare; the highest incidence rate is 4.4% [174]. When leakage occurs, the band should be removed.

Pouch/Esophageal Dilation

The pouch and esophagus stretch when food is consumed faster than it can empty from the pouch [169]. Patients present with food and saliva intolerance, reflux, and a sensation of fullness in their chests [169]. This complication may be due to behavioral problems more than mechanical ones. Data show that patients with pouch/esophageal dilation are much more likely to have eating and mood disorders [176]. The diagnosis can be confirmed with upper gastrointestinal series radiographs. The initial treatment is behavioral diet modifications, along with removal of all the fluid in the band for a few months [169]. If that fails, the band should be removed [177]. Patients should be referred to a WLS program for appropriate management.

Port Complications

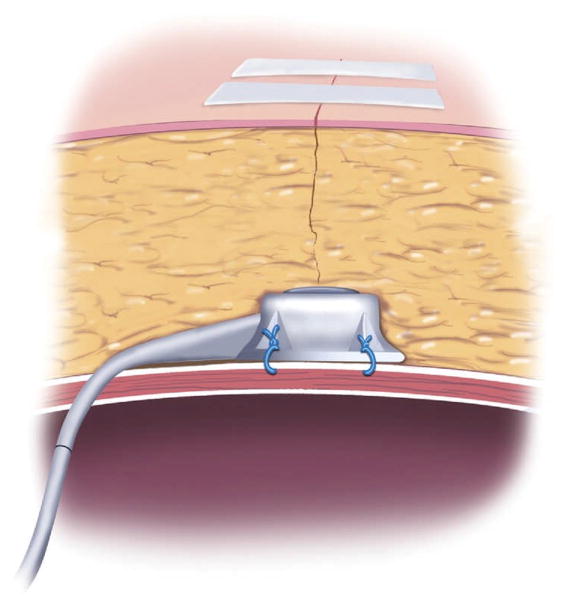

The location of the port may not be obvious to surgeons unfamiliar with AGB placement. Typically, the device is just inferior to the largest abdominal incision. Attempts to access it without knowing exactly where it is may damage the port or the tubing (Fig 12). A plain film of the abdomen may be helpful. When the patient performs a straight leg raise using both legs, the port is easier to palpate. Overall port complications occur in 7.1% to 14.5% of band placements [178,179]. They can be divided into 2 types: infectious and port malfunctions, including port flip and port/tube leakage.

Fig 12.

Position of AGB port. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Port Flip

A port flip can occur from poorly tied knots or excessive physical movement by the patient (Fig 13). Sutures are typically tacked to the abdominal wall fascia with a large permanent suture, such as 0-prolene [33]. Breakage of the suture allows the port to flip. There are some reports of ports flipping due to excessive abdominal movement.178 Flipped ports must be repositioned surgically. This can be performed on an outpatient surgery basis, without replacing the band or tubing portion of the system.

Fig 13.

Port flip. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Port/Tubing Leak

Port or tubing leaks occur 0.4% of the time, typically after multiple attempts to fill the band [178] (Fig 14). The complication is more common when the band is difficult to palpate due to abdominal girth [178]. Patients with no fluid in their bands usually have a leak. Uncertain diagnosis can be confirmed by accessing the band under fluoroscopy and noting the extravasation of fluid with the injection of contrast. If the leak is in the port or tubing, the tubing can be replaced without removing the band itself

Fig 14.

Cause of port/tubing leak in AGB. (Adapted with permission from Jones DB, Olbers T, Schneider B, Atlas of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, c2010 Cine-Med Publishing, Inc., www.cine-med.com.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Port/Band Infection

Infections occur 0.3% to 9% of the time [178]. At the level of the band, these can be associated with gastric erosion. In the event of an intra-abdominal infection from another source (eg, gangrenous cholecystitis, diverticulitis, or ruptured appendicitis), it may be prudent to remove the band at the time of surgical care for the primary source of infection to prevent potential spread to the band.

If only superficial cellulitis is present, port-level infections can be treated initially with intravenous antibiotics. Failure to respond to antibiotics is an ominous sign and usually requires removal of the entire band system. If the patient presents with purulence, the entire system should generally be removed. It is important to remember that port site infection may result from band erosion or another intra-abdominal source that tracks to the port device.

Inadequate Weight Loss

The data are inconsistent as to the amount of weight loss one can expect after AGB placement. Up to 40% of patients lose less than 25% of excess weight [165]; after 10 years, as few as 28% maintain 20% excess weight loss (EWL) [165]. In cases of inadequate weight loss, it is important to distinguish between band complications that cause weight gain or dietary behaviors that limit weight loss. Reoperation should not be rushed if the problem is not due to a technical complication [180].

Rather, patients should be encouraged to continue follow-up with the appropriate members of the multidisciplinary treatment team. The nutritionist should be consulted to reinforce the importance of an appropriate solid diet. The weight loss surgeon can explain that band tightening will not counteract the effects of such foods as ice cream, sweets, and chips. Psychiatric therapy may address problems adjusting to a postsurgical diet or other emotional issues that undermine success. All patients should be encouraged to actively participate in a support group to help them adjust to their post-WLS lifestyle.

Single Incision Laparoscopic Band Placement

Single incision laparoscopic surgery is an investigational procedure; no published data are available about this approach. The technique involves placement of multiple ports, or 1 port with multiple channels, through a single, slightly larger skin incision. The procedure is performed in similar fashion to AGB placement. One of the goals is to make the incision in or near the umbilicus to help “hide” it. Cosmetic benefit is the only advantage associated with this approach.

Although experience is limited, this technique has some limitations. It requires special laparoscopic equipment. Since range of motion is limited, it is best to use a camera with a flexible tip and a light source that does not project off the side of the laparoscope. When used properly, the scope tip will perform most lateral and vertical movements. The flexible tip allows visualization of almost the entire surgical field with very little motion. Flexible tip cameras, which are not easy to use even by experienced laparoscope operators, require practice in a simulated surgical environment. Flexible tip instruments and very low profile ports can also add to the range of motion and triangulation of the surgical field within the limited space.

Even with these tools, adequate visualization is not always possible. Patient safety should not be compromised when attempting any single incision procedure. The threshold for placing enough ports for proper visualization and instrument positioning should be low; additional ports should be added as needed. Poor visualization and improper angulation of instruments may lead to more complications after AGB placement.

Single incision approaches tend to cause port complications. Because the area proximal to the umbilicus typically has more subcutaneous adipose tissue, access may be more difficult and fluoroscopic guidance required for initial band adjustments. In addition, when patients sit up, extra force on ports placed near the umbilicus may lead to port flips. Although early in its development, single incision laparoscopic access is likely to increase in popularity, especially as instrumentation improves. As patient demand for single incision laparoscopic surgery increases, more and more surgeons will likely provide this option. Surgeons early in their learning curve should discuss their experience with the patient as part of the informed consent process.

Sleeve Gastrectomy

Data on the efficacy and safety of SG as a staged or primary procedure are just now being collected. A few short-term series with more than 100 patients have been conducted, but findings are insufficient to conclude that the approach offers greater perioperative safety than any other WLS procedure. However, collective retrospective data suggest that it is at least as safe as RYGB, with an overall complication rate of approximately 24% and a mortality rate of 0.37% [36] (Table 9). Evidence suggests that SG is as effective as RYGB at treating obesity and its comorbidities [181].

Table 9.

Complications of sleeve gastrectomy

| Occurrence (%) | |

|---|---|

| Bleeding | 0–6.4 [90,187] |

| Leaks | 1.4 [60] |

| Narrowing/stenosis | 0.7 [90] |

| Gastric emptyingabnormality | Unknown |

Like malabsorptive procedures, SG produces a marked and sustained reduction in ghrelin levels up to a year after the procedure [38,182]; an outcome that may reduce desire for food [182]. Gumbs and colleagues suggest that SG is the best restrictive operation for extremely obese patients [183]. It may also be an ideal procedure for those who require anti-inflammatory medication or have inflammatory bowel disease [184].

In a randomized prospective study comparing SG to AGB, the former showed higher % EWL at 1 and 3 years (57.7% vs. 41.4%, P = 0.0004) and (66% vs. 48%, P = 0.0025), respectively [185]. Ultimately, the amount of weight loss maintained may be secondary to the remaining stomach size and antral remnant, but the optimum parameters for these have yet to be determined [186]. It also remains to be seen what happens to stomach size and weight loss after more than 5 years of follow-up.

Bleeding

The incidence of bleeding in SG ranges from 0% to 6.4% [90,187]. It occurs mostly from the staple line after the gastrectomy, due in part to the use of larger staples to help seal the thicker tissue of the distal stomach [188]. Many authors advocate routine reinforcement of the staple line by oversewing, applying fibrin glue, or using buttress materials. Although the latter 2 decrease bleeding, oversewing may lead to some narrowing of the gastric tube [37].

Leaks

Leaks after SG occur in up to 1.4% [60] of primary procedures and as many as 6.25% of revision or second staged operations [90]. Clinical studies have yet to prove that the use of fibrin glue, staple line buttressing materials, or oversewing decreases the chance of leaks. Evidence suggests that a switch to smaller stapler height near the angle of His, where the stomach tissue is thinner and most leaks occur, may help prevent leaks [187,190]. Many surgeons favor leaving a small “dog ear” at the angle of His, and not hugging the gastroesophageal junction.

SG can generate higher gastric pressures, and leaks may consequently be slower to close [191]. Gastric decompression and good drainage are the mainstays for controlling leaks, but reoperation may be required if patients are not hemodynamically stable or develop a chronic leak. Those with leaks may present with tachycardia, respiratory distress, fever, and perhaps a “feeling of doom.”

Narrowing/Stenosis

Narrowing creates gastric outlet obstruction that prevents adequate oral intake. It occurs in approximately 0.7% of patients following SG [90]. It may result from use of a gastric tube that is too small to create the sleeve [192], or oversewing the staple line used to create the sleeve [37]. To avoid this complication, some favor the use of fibrin glue or staple line buttressing materials to prevent bleeding. Bougie sizes along the staple line have ranged from 32 to 60 French, but the ideal size has yet to be determined. Creating the sleeve with a tube that is too large can lead to weight gain or reduced weight loss [186]. Many surgeons use a 36 French bougie.

Narrowing occurs most commonly at the gastroesophageal junction and the incisura angularis [193]. Corkscrewing of the gastric tube may also cause narrowing symptoms [193]. Patients with this complication will present with dysphagia, vomiting, dehydration, reflux, and poor PO tolerance [193,194]. The diagnosis can be made by upper gastrointestinal series [193]. Patients with stenosis will require admission for intravenous hydration. Definitive treatment consists of endoscopic dilation, but if the segment of narrowing is too long, surgical intervention is necessary. Most treatment consists of conversion to another WLS, such as RYGB, but there are also some data about successful laparoscopic seromyotomy (division of the long area of stenosis) to relieve the symptoms of narrowing [193]. Once patients are stabilized, they should be transferred to a weight loss surgeon familiar with SG.

Increased or Decreased Gastric Emptying

Controversy over delayed gastric emptying leading to reflux disease and pouch dilation centers around the amount of antrum to leave behind [186].

Unlike the fundus, the antrum lacks storage capacity and may contribute to feelings of satiety and fullness after meals [186]. Too large an antrum may result in delayed gastric emptying, whereas complete removal may lead to dumping and increased gastric emptying [186].

The incidence of dilation does not directly correlate with weight regain [195]. Many surgeons begin resection 5 to 7 cm from the pylorus. However, Melissas and colleagues determined that gastric emptying time is reduced in SG patients with a 7-cm antrum [91]. This may result in less restriction and lead to weight regain over time [185,186].

Treatment of stenosis consists of sleeve revision to reduce volume, adding a BPD, or converting to a RYGB. SG technique is an area that warrants further examination as the exact mechanism(s) of action remain unknown.

Nutrition

Nutritional recommendations after SG follow those of other restrictive procedures. Data on specific nutritional changes after SG are not available; evidence of more hormonal, nutrient, and caloric concerns after this operation is scant [183]. Although ghrelin levels decline after SG, the effects of that or other changes on morbidity are unknown and require further investigation.

Vertical Banded Gastroplasty

VBG was once a very popular form of WLS. As a purely restrictive weight loss procedure, patients could lose up to 70% of their excess weight [196]. Unfortunately they could also experience an 18% perioperative complication rate [196], and a failure rate as high as 43% [197]. In a comparison of AGB and VGB reoperation rates within 5 years of WLS, Miller and colleagues found a 32.4% difference (7.5% vs. 39.9%, respectively) [61].

The main causes of failure in VBG were stomal stenosis, staple line dehiscence leading to fistula and weight gain, reflux disease, and band erosion [62]. Due to unsatisfactory long-term weight loss, most bariatric surgeons agree that VBG should not be used as a primary treatment for obesity [39] (Table 10).

Table 10.

Complications of vertical banded gastroplasty

| Occurrence (%) | |

|---|---|

| Staple line dehiscence | 48 [200] |

| Obstruction/gastric restriction | 40 [199] |

| Band erosion | 1–7 [197,202] |

| Inadequate weight loss | 58 [111] |

Staple Line Dehiscence