Abstract

CALGB conducted a Phase II study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen with allogeneic transplantation to treat patients with recurrent low grade B cell malignancies. Patients over age 18 with a diagnosis of relapsed, chemotherapy-sensitive disease underwent transplantation with a matched sibling donor and conditioning with cyclophosphamide (1 g/m2/d × 3) and fludarabine phosphate (25 mg/m2/d × 5). GVH prophylaxis included cyclosporine or tacrolimus plus low-dose methotrexate. Forty-four evaluable patients with a median age of 53 and median of two prior regimens were accrued. Sixteen patients had follicular NHL and 28 had histologies including 7 indolent B cell lymphomas, 4 mantle cell, 15 chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and 2 prolymphocytic leukemia pts. The six-month treatment-related mortality (TRM) was 2.4% and three-year TRM was 9%. Three-year event-free and overall survival were.75 and .81 for the follicular patients, .59 and .71 for the CLL/PLL patients, and .55 and .64 for the other histologies. The incidence of grade 2–4 acute graft vs host disease (GVHD) was 29% and extensive chronic GVHD was 18%. This report demonstrates that allogeneic sibling transplantation with a reduced intensity conditioning regimen is safe and efficacious for patients with advanced indolent B cell malignancies enrolled on a Cooperative Group study.

Introduction

The treatment of low-grade non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (NHL) has traditionally been associated with high response rates, but a generally accepted inability to induce durable remissions and cure in the vast majority of patients with advanced disease.1,2 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), and prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL) share similar characteristics as treatable but incurable malignancies with conventional approaches.3 Mantle cell lymphoma is a more aggressive malignancy that has recently demonstrated sensitivity and durable remissions following high dose therapy with intensive chemotherapy regimens and transplantation.4–6 These approaches have produced encouraging results in this disease and demonstrate improved progression-free and overall survival compared to conventional chemotherapy regimens plus the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab when used as a component of initial therapy.

As with its use in mantle cell lymphoma, the addition of rituximab to conventional regimens for indolent lymphomas or CLL has increased the response rate and disease-free survival in these diseases.3,7–9 The addition of rituximab also led to an improvement in overall survival when it was included as a component of salvage therapy in one large study.10 Additional treatments such as 131Iodine tositumomab or 90Yttrium ibritumomab tiuxetan labeled anti-CD20 bound isotopes are also effective, but not necessarily more so than employing maintenance therapy with unlabelled anti-CD20 antibodies11–14 Although these improvements have been gratifying for patients afflicted with these malignancies, eventual progression to refractory disease and death remains a problem.1,2.

Over the past 20 years, reports have emerged of the value of high-dose therapy with transplantation in treating these illnesses. Early studies with autologous transplants were especially encouraging when the infused marrow product was rendered tumor free by pcr analysis after ex vivo purging with anti-CD20 antibodies.15–17. Concerns remain about the risk of late complications such as the emergence of myelodysplasia or acute leukemia in patients treated with this approach and for a number of years, such treatment had fallen out of favor.18–22 Recent data has suggested that the use of antibody-mediated in vivo tumor cell purging might be lead to long remissions and possible cure without the high risk of treatment related complications associated with allogeneic transplants, but the durability of these responses and the long term risks of secondary malignancies remain uncertain.23–27

Data has emerged from both registry and large single institution studies that allogeneic donor transplants, whether with an ablative or non-ablative approach can be associated with prolonged remission and apparent cure for low-grade NHL patients.28–36 Reduced intensity regimens have demonstrated low morbidity and mortality rates associated with these approaches even after relapse following an autologous transplant.37–39 As a result of these encouraging single-institution results, CALGB undertook a prospective multi-center trial for patients with relapsed low-grade or mantle cell lymphoma, CLL, PLL, or SLL using matched related donors and a reducedintensity regimen.40 The current report describes the results of this Phase II study with a single conditioning regimen, GVHD prevention, and supportive care strategy.

Methods

Study Objectives

The primary objective of this trial was to demonstrate a six-month treatment-related mortality (TRM) rate of less than 30% in a multi-center trial for patients with low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma, CLL and PLL. The secondary objectives of the trial were to measure the response rates at six and 12 months post-transplant, the event-free and overall survival of this study population and assess the development of the total and T cell chimerism rates in the peripheral blood and marrow at 30, 60, 90, and 180 days. Additional study endpoints included determining the cumulative risk of acute and chronic graft vs host disease, and identifying other treatment-related toxicities such as sinusoidal obstructive syndrome and duration of cytopenias. Classical definitions of GVHD were used including a designation of chronic GVHD as that which occurred after day 100.42

Patient Eligibility

All patients were < 70 years of age, had histologically documented chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL), low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), or mantle cell lymphoma as follows. Diagnosis of CLL was made according to the NCI 1996 criteria.41 Histologic documentation of CLL or PLL required a lymphocytosis > 5,000/µl with < 55% prolymphocytes for CLL; patients with ≥ 55% prolymphocytes were classified as PLL. Histologic documentation of low-grade NHL was made according to the REAL Subtypes: small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular center lymphoma (grade I or II), diffuse predominantly small cell type, or marginal zone B-cell. Patients must have failed at least one prior regimen or have ≥3 of the IPI risk factors; age > 60; PS>1; LDH>normal; presence of > 1 site of extra-nodal disease; or stage III/IV disease. Diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma required histologic documentation with at least one of the following: immunophenotype with expression of CD5 and CD19 without CD23; cytogenetic analysis with presence of t(11;14); over-expression of cyclin D1, or bcl1 re-arrangement.

All patients had stable or responsive disease to their most recent treatment and were ≥ 4 weeks since prior chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. Patients may not have received a prior autologous transplant and not have symptomatic pulmonary disease, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or serious infection. All patients had a matched sibling donor by low-resolution typing at HLA A, B, DR.

All patients were staged with a physical exam, CT or PET/CT scan, bone marrow aspirate and biopsy, and organ function testing. Laboratory values included granulocytes ≥ 500/µL, platelets, ≥ 50,000/µL, calculated creatinine clearance, ≥ 40 cc/min, total bilirubin, ≤ 3 × ULN, AST, ≤ 3 × ULN, negative u-HCG or serum HCG if of child-bearing potential, DLCO > 40% and LVEF > 30%.

Each participant signed an IRB-approved, protocol-specific informed consent in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines.

Treatment Schema

Fludarabine was given at a dose of 30 mg/m2/day on Days -7 through -3. Cyclophosphamide was given at a dose of 1 g/m2/day IV on days -5 through -3. A target goal of 5–8 × 106 matched sibling donor peripheral blood CD34+ cells were collected following four or five days of G-CSF administration at 10 ug/kg/d on days -5 to -2 or -1, and infused on day 0.

GVHD prophylaxis and assessment

GVHD prophylaxis consisted of tacrolimus on day -1 with tapering begun on Day +90 as tolerated with a goal of stopping by Day +150. The rate of taper was adjusted for the presence of signs and symptoms of GVHD. Tacrolimus was tapered more quickly (Day +60 to Day +90) if donor chimerism of CD3 cells was < 50% at Day +60 or if disease progression occurred. A competing risks model was used to simultaneously estimate the probabilities of acute or chronic GVHD and death. A similar competing risks model was used to simultaneously estimate the probabilities of acute GVHD and death.

Donor Lymphocyte Infusion

Patients with progressive disease and no evidence of GVHD were tapered off tacrolimus at the time progressive or stable disease was noted. If there was no evidence of active GVHD, then donor lymphocyte infusions (DLI) were given no sooner than 30 days after complete cessation of GVHD prophylaxis treatment. The initial dose of DLI was 1 × 107 CD3 cells/kg. Subsequent doses of DLI could be given at intervals of no less than 30 days in the absence of response or GVHD with doses of 5 × 107 CD3 cells/kg.

Supportive Care

Antibiotic Prophylaxis consisted of fluconazole, acyclovir, and TMP/SMX per institutional standards. CMV monitoring and therapy were based on positive cultures or pcr testing. G-CSF was administered at a dose of 5 ug/kg/day from day +5 until an ANC of >1000/ul was achieved for 3 consecutive days.

Study Monitoring and Statistical Design

Study monitoring, data quality and statistical evaluation were undertaken by the CALGB Statistical and Data Management Centers. The primary endpoint of the study was treatment-related mortality within six months of the day of stem cell infusion (Day 0). The primary hypothesis was that the probability of experiencing a TRM was less than 30%. The null hypothesis, H0, that the TRM rate, p. is less than or equal to .15 (H0: p <0.15) was compared with the alternative hypothesis, HA, that p is greater than or equal to 0.30 (HA: p> 0.30). TRM was assessed at three stages with 15 patients accrued per stage and a maximum of 45 patients entered onto the study as long as the stopping criteria for the study were not met. The significance level and power of this design were 0.08 and 0.85, respectively. The time to event distributions for overall and event-free survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method while the discrepancy between two time to event distributions was tested using the log-rank test.

Chimerism studies

Donor chimerism in peripheral blood as well as CD19, CD3, and CD14/15 selected cells were determined using a pcr-based method that routinely achieved 1% sensitivity. CD19, CD3, and CD14/15 cells were selected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using Miltenyi magnetic particles (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The purity of each cell subset was determined by flow cytometry. Two short tandem repeat (STR) loci were amplified for each donor-recipient pair (selected from VWF, D21S11, D18S51, D16S539, PENTA D, D3S1358, FGA, D7S820, D2S1338, D10S2325, D12S391, SE33, PENTA E). Amplicons were separated using an automated nucleotide sequencer (ABI 3100 Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the quantity of each informative allele from duplicate samples was determined using GeneMapper fragment analysis software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).43

Results

Patient Characteristics

Forty-seven patients from 13 different CALGB transplant centers were registered onto this study (Table 1). Three patients never began therapy and will not be included in this analysis of 44 patients who were treated per protocol between August, 2001 and April, 2006. Histologies included 16 follicular, 7 other indolent B cell disease, 4 mantle cell, 15 CLL and 2 PLL pts. Median time from diagnosis to transplant was 2.5 years (range 0.4 to 12.4 years). The median number of prior therapies was 3 for the entire group (range 1–6) including a median of 3 for those patients with CLL/PLL or Mantle Cell/Other histologies and 2 prior therapies for the 16 patients with follicular NHL. Four patients had received prior irradiation and 1 of 27 NHL patients had an ECOG performance status greater than 1. Forty-one percent of NHL patients had > 1 site of extra-nodal disease. The majority of patients had either a short duration of initial remission, young age, high-risk disease, or were transplanted following multiple therapies.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| 47 Patients Enrolled (44 evaluable) | |||

| Median age | 53 yrs (range 39–68) | ||

| male | 80% | ||

| caucasian | 72% | ||

| Time from dx to SCT | 2.5 yrs (0.4–12) | ||

| Elevated LDH | 8/27 (30%) | ||

| Stage IV >1 extranodal site | 11/27 (41%) NHL pts | ||

| Histologies | |||

| NHL | 27 pts (61%) | ||

| Follicular | 16 pts (36%) | ||

| B cell | 7 pts (16%) | ||

| SLL | 3 pts | ||

| Marginal Zone | 3 pts | ||

| Malt | 1 pt | ||

| Mantle Cell | 4 pts (9.1%) | ||

| CLL | 15 pts (34.1%) | ||

| PLL | 2 pts (4.6%) | ||

| Prior Therapies | |||

| Prior treatment | CLL/PLL | Other B Cell/MC | Follicular |

| # patients | 17 | 11 | 16 |

| # chemo regimens | 3(1–5) | 3 (1–6) | 2 (1–3) |

| Immunotherapy | 9 | 7 | 3 |

| XRT | 1 | 1 | 3 |

Toxicity

Overall 6-month treatment-related mortality was 2.3% (1 subject) at day 117 from GVHD and sepsis indicating strong statistical evidence in support of the study hypothesis (Table 2). Three additional patients died of non-relapse causes at 18, 19, and 36 months from GVHD and sepsis for a three-year treatment-related mortality rate of 9%. One additional patient died of fungal pneumonia in conjunction with treatment for chronic GVHD 7 years following transplant, while another died of pancreatic adenocarcinoma for an overall non-relapse mortality of 13.6% after a minimum follow-up of 3 years. Twenty-five percent (11/44) of patients experienced grade 4 non-hematologic toxicities, primarily from infection or GVHD. Additional serious toxicities included one pulmonary embolus, one grade 4 sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, and two second malignancies; one of the pancreas and a second of the distal esophagus. The median duration of an ANC < 1000/ul was 8 days (range 0–19) and thrombocytopenia < 100,000/ul was 12 days (range 0–38). Twenty-seven of the 44 patients required no platelet transfusions. The median number of red cell transfusions during the transplant period was 1 (range 0–9) with 13 patients requiring no RBC transfusions. Infectious complications were documented in 67% of patients; viral infections in 32%, including CMV reactivation in 15% of patients and CMV infection in 2 patients, bacterial in 41% and fungal in 20% of patients (more than one type of infection was seen in multiple patients). An additional 30% of patients had site-specific infections for which no organism was identified.

Table 2.

Toxicities

| Hematologic | ||

| Days ANC < 1000/ul | 8 (0–19) | |

| Days plts < 100,000/ul | 12 (0–38) | |

| Non-heme Grade IV toxicities (44 evaluable) | ||

| *Total | 11 (25%) | |

| Pulmonary | 5 (11%) | |

| Metabolic | 2 (4.5%) | |

| Pulmonary Embolus | 1 (2%) | |

| Veno-occlusive Disease | 1 (2%) | |

| 2nd tumor (panc, esoph CA) | 2 (4.5%) | |

| Infections | ||

| Viral | 14 (32%) | |

| **CMV | 9 (20%) | |

| Bacterial | 18 (41%) | |

| Fungal | 10 (22%) | |

| Other | 13(30%)(no organism) | |

| Total | 28 (67%) | |

More than one type of infection was seen in multiple patients.

Two patients had CMV infection with pneumonia (1) or colitis (1) and seven had viral reactivation requiring pre-emptive therapy.

Chimerism

As described in Table 3, the median % of peripheral blood donor T-cell chimerism at days 30, 60 and 180 were 88, 94, and 97% respectively. Comparable values for unfractionated (lymphoid + myeloid population) peripheral blood chimerism at days 30, 60, and 180 were 80, 85, and 99% respectively. While these median values were high, a significant percentage of patients demonstrated a persistent mixed chimerism picture out to day 180. Greater than 90% peripheral blood donor T cells was seen in 45, 61, and 64% of patients at days 30, 60, and 180 post-transplant. Likewise, > 90% unfractionated peripheral blood donor chimerism was seen in 26, 36, and 65% of patients at days 30, 60, and 180 respectively. (Table 3) Thus, if full donor chimerism was defined as > 90% donor cells, then 64 and 65% of patients showed full donor engraftment in the unfractionated and lymphoid compartments respectively by six months. Bone marrow and peripheral blood gave similar chimerism results at each time point. Finally, no correlation was observed between chimerism status and relapse.

Table 3.

Chimerism

| Day post-transplant | 30 | 60 | 180 |

|---|---|---|---|

| T cells | |||

| # pts with > 90% donor cells | 45% | 61% | 64% |

| median % donor cells | 88% | 94% | 97% |

| Unfractionated whole blood cells | |||

| # pts with > 90% donor cells | 26% | 36% | 65% |

| median % donor cells | 80% | 85% | 99% |

GVHD

The overall incidence of grades 1–4 acute GVHD was 61% of which 11% was grade 2, 16% grade 3, and 2.3% grade 4. Twenty-nine point three (29.3) percent of patients experienced limited and 18% had extensive chronic GVHD.

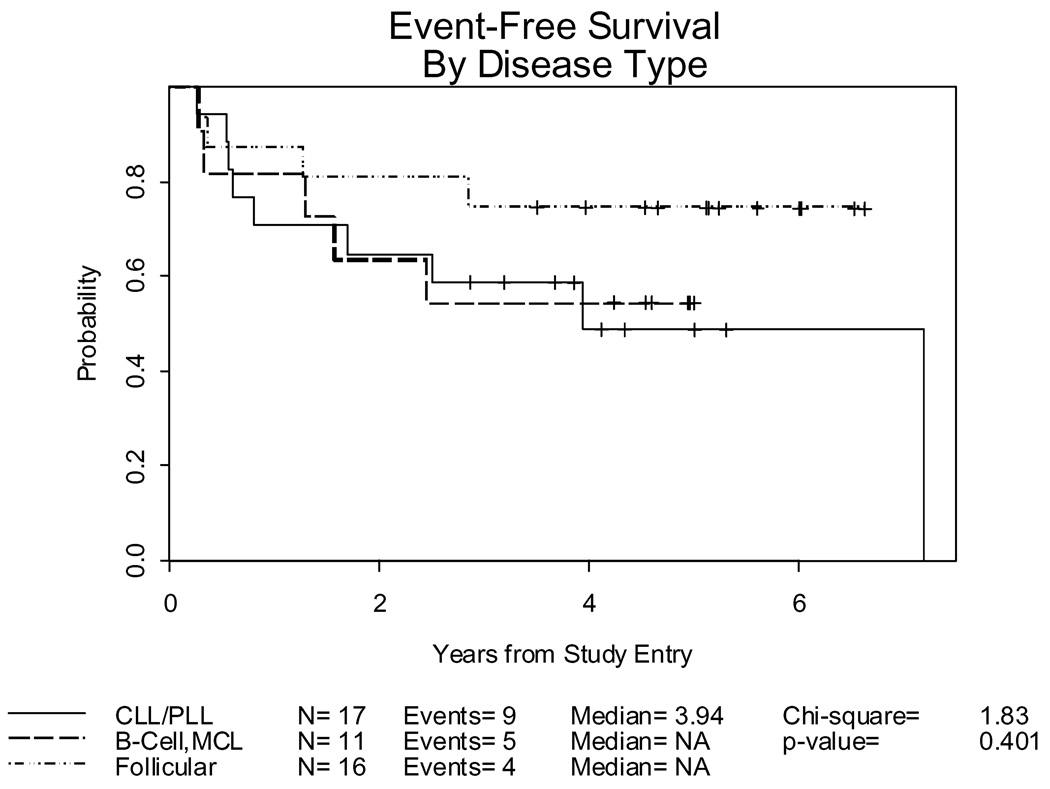

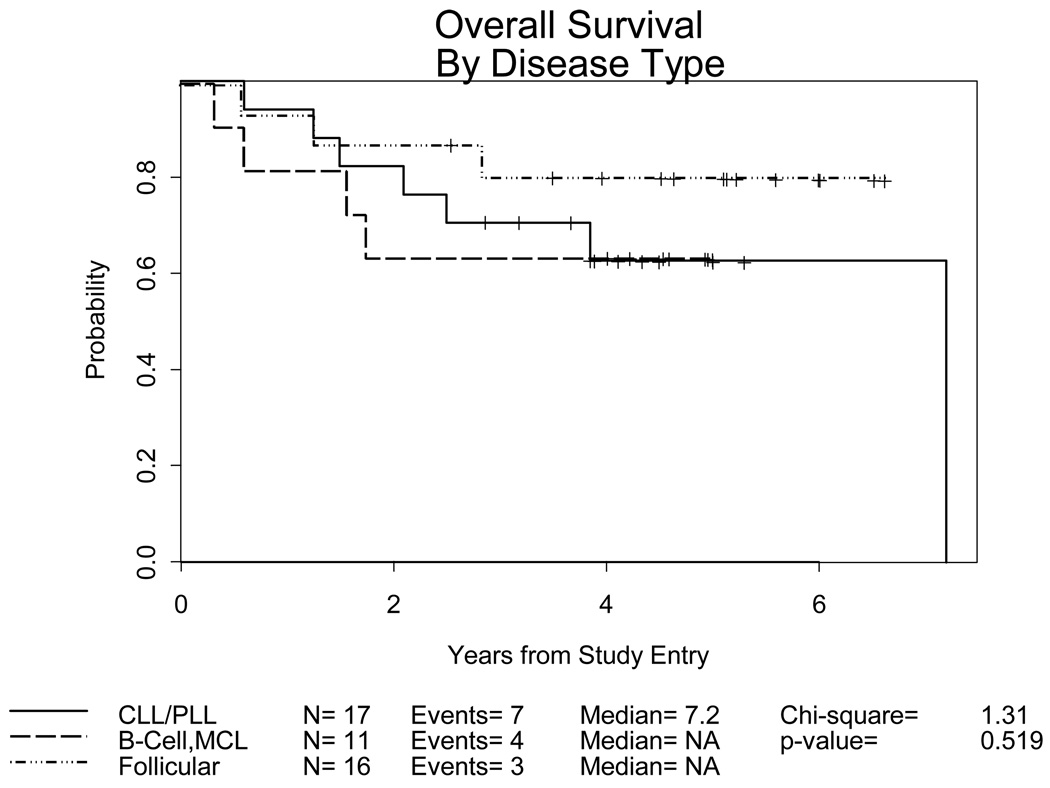

Event-free and Overall Survival Figures 1 and 2

Figure 1.

Event-Free Survival for 44 evaluable patients and 18 deaths or episodes of progressive disease by disease histology: Follicular, n=16/4 events; other B Cell/Mantle Cell, n=11/5 events; and CLL/PLL, n=17/9 events

Figure 2.

Overall Survival: 44 evaluable patients and 14 deaths by disease histology: Follicular, n=16/3 deaths; B Cell/Mantle Cell, n=11/4 deaths; CLL/PLL, n=17/7 deaths

Event-free survival (EFS) is defined as time to progression or death due to any cause (Table 4). There have been 18 events. Twelve patients have relapsed at 3 (3 pts), 4 (1 pt), 6 (2 pts), 9(1 pt) 15 (2 pts), 20 (1 pt), 29 (1pt) and 45 (1 pt) months post transplant. The other 6 events were deaths in the absence of relapse due to GVHD (2), sepsis (2), fungal pneumonia in the setting of chronic GVHD (1) and adenocarcinoma (1). While most patients with lymphoma achieved optimal response within the first three months post-transplant, the CLL/PLL cohort demonstrated a slower pace of response with the median time to CR being 3.5 months, but one patient reported as requirig 9 months and another 22 months post-transplant. Six of 17 patients with CLL/PLL, 3/16 with follicular and 3/11 patients with other indolent B cell malignancies have relapsed. Four patients received DLI for progressive disease and subsequently died of their malignancy. The other relapsed patients were felt to be ineligible for DLI either because of uncontrollable relapse or pre-existing GVHD. One additional patient received DLI for a stable partial response and one for loss of chimerism. Both remain in complete remission more than four years post transplant.

Table 4.

Outcomes

| Follicular | CLL/PLL | Other/MC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # | 16 | 17 | 11 |

| 3 year Event-free survival | .75 (.46–.90) | .59 (.33–.78) | .55 (.23–.78) |

| 3 year Overall Survival | .81 (.51–.93) | .71 (.43–.87) | .64 (.30–.85) |

| Disease progression | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Death | 3 | 7 | 4 |

For the 30 patients still alive, the median follow-up is 4.6 years. The EFS at 3 years for follicular patients was 0.75 (.46–.90), compared to 0.59 (.33–.78) for CLL/PLL and 0.55 (0.23–.78) for the other and mantle cell histologies combined (Figure 1). Fourteen deaths have occurred from progressive disease (7), infection and GVH (6, one of which occurred following a second transplant for relapsed disease), and a second malignancy (1). Overall survival at 3 years is 0.81 (.51–.93) for the follicular histologies, 0.71 (.43–.87) for CLL/PLL and 0.64 (.30–.85) for the other and mantle cell histologies, respectively (Figure 2).

Discussion

Despite the recent advances in standard therapies, treatment outcomes for patients with indolent B cell malignancies remain suboptimal, as life expectancies are clearly reduced by these diagnoses.1–10,14,25 For those patients who are seeking a cure, stem cell transplantation has been available for many years, although late recurrences and the development of secondary myelodysplasia have undermined the utility of autologous transplants while treatment-related morbidity and mortality, and lack of suitable donors have limited the use of allogeneic transplants.15–17,22 Recently, the use of reduced intensity regimens has markedly reduced early morbidity and mortality following allogeneic transplantation.32–34,43–48 While early relapse and later complications of chronic graft vs host disease and infection remain a problem, the overall success with these reduced intensity regimens have all indicated a plateau on the survival curves with 4 year or longer disease free remission rates exceeding 60% for chemotherapy-responsive patients.32,35,36,44 The data from Khouri is especially encouraging with the use of transplant and high-dose rituximab as the progression-free survival (PFS) in that trial exceeded 80% at five years with a very low incidence of acute and chronic GVHD for matched related transplant patients.36 A treatment regimen including the identical schedule and dosage of rituximab is currently being evaluated in a multi-center trial sponsored by an intergroup collaboration between the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT-CTN), CALGB, ECOG, and SWOG.

In the current report, the fact that a multi-center group was able to conduct an allogeneic transplant study that yielded excellent outcomes with only a 2.3% six month TRM was very encouraging. Recent mortality rates from other trials are similar, but at the time the study was planned, there was no Cooperative Group experience with reduced-intensity allogeneic transplant on which to base an expectation of TRM.28,33,34 Morbidity was also low, with an overall incidence of grade IV non-hematologic toxicities of 25% including an 11% incidence of pulmonary complications that consisted of pneumonitis, infection, and alveolar hemorrhage. Severe hepatic and renal toxicities were rare and the overall incidence of infections included 5% CMV infection and 15% reactivation, 41% bacterial, and 20% documented fungal processes.

The overall incidence of grade 2–4 acute GVHD was 29%. Thirty percent of patients had limited and 18% had extensive chronic GVHD. While these numbers are somewhat higher than those reported by groups that have used alemtuzamab as a component of the conditioning regimen, reactivation of CMV is less frequent, and the need for donor lymphocyte infusion for relapse appears lower in the current study.32,39,44 At day 30 post-transplant, only 26% of patients demonstrated > 90% unfractionated peripheral blood donor chimerism and 45% demonstrated > 90% T cell donor chimerism. By day 180, the % of patients with > 90% unfractionated and T cell donor chimerism had increased to 65 and 64% respectively. At the same time points, the median percentage of donor T cell chimerism was higher and reached 85 and 94% by day 60, and 99 and 97% by day 180. Thus, while the median % of donor cells is high in both the myeloid and lymphoid compartments by day 180, only about 2/3 of patients achieved full donor chimerism in both components of the peripheral blood by as late as 6 months following transplant. If the approach encouraged by Thomsen and colleagues44was followed, this could lead to donor lymphocyte infusions for as many as 1/3 of the patients, even in the absence of disease progression. Peripheral blood and marrow values correlated well with one another. The lack of correlation between relapse and chimerism status may reflect small numbers of patients in our study or alternatively, indicate that partial chimerism may in fact be sufficient to maintain an anti-tumor effect while associated with a low rate of long term GVHD in most patients. Our results are somewhat different from the report by Thomson where relapse was lower in those patients who converted from partial to full donor chimerism after DLI infusions compared to those who remained with a mixed chimerism status despite DLI. They also reported a higher remission and durable remission rate in those relapsed patients who received DLI than we observed, perhaps due to earlier intervention at a time of less advanced disease. Alterations in the immunosuppression regimens used or early infusion of DLI might enhance the rate and frequency of full donor chimerism, but one would expect this to be associated with an increased rate and severity of GVHD. Despite these concerns, the Thomson results were excellent, with 76% of patients remaining progression-free at four years with only 18% having extensive chronic GVHD.44 There were 14 deaths reported to date in the CALGB study including nine in patients who had relapsed and required additional therapy. One patient died from a pancreatic cancer, 2 years post transplant. Five patients died of infection related to GVHD at 4, 18, 19, 36, and 72 months post transplant.

Significant challenges remain to the successful application of this approach. While the use of well-matched unrelated donors has not had a negative impact in recent reports of transplant studies for acute leukemia, data on approaches using such donors in low-grade malignancies is just emerging. Recent reports by the EBMT and CIBMTR have indicated that while use of unrelated donors resulted in a somewhat higher incidence of acute and chronic GVHD, the overall rates of progression, morbidity, and mortality compare favorably to outcomes following fully-ablative transplants.33,45 It is notable, however, that the recent paper by Thomson reported higher rates of progression-free survival in their matched related than unrelated patients, even with a reduced intensity regimen. While 53 is relatively old for allogeneic transplants, it is young for low grade NHL and CLL populations and in future trials, one would anticipate an even higher median age and likely a higher morbidity and mortality rate. Whether the relapse rate could be reduced further by more intensive therapy remains a question to be considered given the high rate of toxicity and low success rate associated with frank relapse followed by DLI in the current study.48,49 Of the six patients who received DLI, four died from progressive disease despite the onset of significant GVHD while the two patients infused with DLI for loss of chimerism and stable partial remission remain in CR more than two years beyond DLI infusion. This suggests that careful monitoring for relapse and early use of DLI may be a more effective strategy than delaying such efforts until frank recurrence is observed.44,50

Although the number of enrolled patients with low-grade NHL or CLL are less than in the Khouri or Thomson trials, our results are remarkably similar, especially for the follicular lymphoma patients.36,44 Even in more aggressive diseases such as prolymphocytic leukemia or mantle cell lymphoma, there appears to be a plateau on the event-free survival curves, albeit with median follow-up that remains less than four years. While the number of patients is small, we have only had one patient relapse beyond 2 years in this study, suggesting that most responses will be durable. This is consistent with the results published by the M.D. Anderson group in which non-ablative allogeneic transplant appeared to confer a higher likelihood of prolonged disease-free survival in mantle cell patients, especially in those with relapsed or refractory disease, compared to what had been achieved with autologous transplantation.51 Also of note is the prolonged time to best response that can be seen in these patients, particularly those with CLL. This likely reflects in part the slow time to establishing full donor chimerism which is associated with the graft vs leukemia effect that is known to occur in these patients but which can take months to develop.

Our results testify not only to the efficacy of this approach, but confirm that this treatment can be undertaken safely and effectively in a large number of transplant-centers by following rigorous protocols. These outcomes should reassure the oncology community that this is a viable and potentially curative strategy for otherwise healthy patients with advanced, but still chemosensitive disease, or those demonstrating progressively shorter durations of response to standard therapies.

Acknowledgements

The research for CALGB 109901 was supported, in part, by a grant from Amgen, Inc and by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA31946) to the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (Monica Bertagnolli, MD, Chairman) and to the CALGB Statistical Center (Stephen George, PhD, CA33601). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute. We also wish to thank the patients and staff who took part in this trial and made this study possible.

The following institutions participated in this study:

Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC–Minetta C Liu, M.D., supported by CA77597

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY–Lewis R. Silverman, M.D., supported by CA04457

Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY–Ellis Levine, M.D., supported by CA59518

The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH–Clara D Bloomfield, M.D., supported by CA77658

University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA–Barbara A. Parker, M.D., supported by CA11789

University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA–Charles J Ryan, M.D., supported by CA60138

University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA–William V. Walsh, M.D., supported by CA37135

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC–Thomas C. Shea, M.D., supported by CA47559

Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC–David D Hurd, M.D., supported by CA03927

Western Pennsylvania Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA–John Lister, M.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Swenson WT, Wooldridge JE, Lynch CF, et al. Improved survival of follicular lymphoma patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5019–5026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher RI, LeBlanc M, Press OW, et al. New treatment options have changed the survival of patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8447–8452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam CS, O'Brien S, Wierda W, et al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:975–980. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam ST, Bassett R, Ledesma C, et al. Mature results of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center risk-adapted transplantation strategy in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;113:4144–4152. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damon LE, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for untreated patients with mantle-cell lymphoma: CALGB 59909. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6101–6108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo–purged stem cell rescue: A nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2009;112:2687–2692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:1417–1423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochster H, Weller E, Gascoyne RD, et al. Maintenance rituximab after cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone prolongs progression-free survival in advanced indolent lymphoma: Results of the randomized phase III ECOG1496 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1607–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallek M, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink A-M, et al. First-Line Treatment with Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, and Rituximab Improves Overall Survival in Previously Untreated Patients with Advanced Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Results of a Randomized Phase III Trial On Behalf of An International Group of Investigators and the German CLL Study Group. Blood. 2009;114 Abstract 535. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Oers MHJ, Klasa R, Marcus RE, et al. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: Results of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial. Blood. 2006;108:3295–3301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminski MS, Tuck M, Estes MAJ, et al. I-Tositumomab Therapy as Initial Treatment for Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:441–449. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Press OW, Unger JM, Braziel RM, et al. Phase II trial of CHOP chemotherapy followed by tositumomab/iodine I-131 tositumomab for previously untreated follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Five-year follow-up of Southwest Oncology Group Protocol S9911. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4143–4149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, et al. Phase III Trial of Consolidation Therapy With Yttrium-90–Ibritumomab Tiuxetan Compared With No Additional Therapy After First Remission in Advanced Follicular Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5156–5164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buske C, Hoster E, Dreyling M, et al. Rituximab in Combination with CHOP in Patients with Follicular Lymphoma: Analysis of Treatment Outcome of 552 Patients Treated in a Randomized Trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group after a Follow up of 58 Months. Blood. 2008;112 Abstract 2599. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman AS, Neuberg D, Mauch P, et al. Long-term follow-up of autologous bone marrow transplantation in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:3325–3333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohatiner AZ, Nadler L, Davies AJ, et al. Myeloablative therapy with autologous bone marrow transplantation for follicular lymphoma at the time of second or subsequent remission: Long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2554–2559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montoto S, Canals C, Rohatiner AZ, et al. Long-term follow-up of high-dose treatment with autologous haematopoietic progenitor cell support in 693 patients with follicular lymphoma: An EBMT registry study. Leukemia. 2007;21:2324–2331. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennifer R. Brown, Heather Yeckes, Jonathan W, et al. Increasing Incidence of Late Second Malignancies After Conditioning With Cyclophosphamide and Total-Body Irradiation and Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2208–2214. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatia S, Robison LL, Francisco L, et al. Late mortality in survivors of autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation: Report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2005;105:4215–4222. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gyan E, Foussard C, Bertrand P, et al. High-dose therapy followed by autologous purged stem cell transplantation and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma: A randomized multicenter study by the GOELAMS with final results after a median follow-up of 9 years. Blood. 2009;113:995–1001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micallef IN, Lillington DM, Apostolidis J, et al. Therapy-related myelodysplasia and secondary acute myelogenous leukemia after high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic progenitor-cell support for lymphoid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:947–955. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Schiegnitz E, et al. Moderate increase of secondary hematologic malignancies after myeloablative radiochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with indolent lymphoma: Results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4926–4933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schouten HC, Qian W, Kvaloy S, et al. High-dose therapy improves progression-free survival and survival in relapsed follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Results from the randomized European CUP trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3918–3927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Schiegnitz E, et al. Myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission prolongs progression-free survival in follicular lymphoma: Results of a prospective, randomized trial of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2004;104:2667–2674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebban C, Brice P, Delarue R, et al. Impact of rituximab and/or high-dose therapy with autotransplant at time of relapse in patients with follicular lymphoma: A GELA study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3614–3620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiddemann W, Buske C, Kneba M, et al. Autologous stem cell transplanation after myeloablative therapy in first remission may be beneficial in patients with advanced stage follicular lymphoma after front-line therapy with R-CHOP. An analysis of two consecutive studies of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2008 Abstract 772. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladetto M, De Marco F, Benedetti F, et al. Prospective, multicenter randomized GITMO/IIL trial comparing intensive (R-HDS) versus conventional (CHOP-R) chemoimmunotherapy in high-risk follicular lymphoma at diagnosis: The superior disease control of R-HDS does not translate into an overall survival advantage. Blood. 2008;111:4004–4013. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Besien K, Loberiza FR, Jr, Bajorunaite R, et al. Comparison of autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:3521–3529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verdonck LF, Dekker AW, Lokhorst HM, et al. Allogeneic versus autologous bone marrow transplantation for refractory and recurrent low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;90:4201–4205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arcaini L, Montanari F, Alessandrino EP, et al. Immunochemotherapy with in vivo purging and autotransplant induces long clinical and molecular remission in advanced relapsed and refractory follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1331–1335. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarella C, Zanni M, Magni M, et al. Rituximab improves the efficacy of high-dose chemotherapy with autograft for high-risk follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicenter Gruppo Italiano Terapie Innnovative nei linfomi survey. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3166–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris E, Thomson K, Craddock C, et al. Outcomes after alemtuzumab-containing reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation regimen for relapsed and refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2004;104:3865–3871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laport G, Bredeson CN, Tomblyn M, et al. Autologous versus reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients with follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma beyond first complete response or first partial response. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.11.004. Abstract 7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomblyn M, Brunstein C, Burns LJ, et al. Similar and promising outcomes in lymphoma patients treated with myeloablative or nonmyeloablative conditioning and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson S, Canals C, Blaise D, et al. Reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for follicular lymphoma results in an improved progression free survival when compared to autologous stem cell transplantation. An analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the EBMT. Blood. 2008;112 Abstract 458. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khouri IF, McLaughlin P, Saliba RM, et al. Eight-year experience with allogeneic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular lymphoma after non-myeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. Blood. 2008;111:5530–5536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson KJ, Morris EC, Bloor A, et al. Favorable long-term survival after reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation for multiple-relapse aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:426–432. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingram W, Devereux S, Das-Gupta EP, et al. Outcome of BEAM-autologous and BEAM-alemtuzumab allogeneic transplantation in relapsed advanced stage follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:235–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pérez-Simón JA, Kottaridis PD, Martino R, et al. Comparison between 2 prospective studies in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2002;100:3121–3127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shea TC, Johnston J, Walsh W, et al. Reduced Intensity Allogeneic Transplantation Provides High Disease-Free and Overall Survival in Patients with Advanced Indolent NHL and CLL: CALGB 109901. Blood. 2007;110 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.016. Abstract 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever MR, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharf SJ, Smith AG, Hansen JA, et al. Quantitative determination of bone marrow transplant engraftment using fluorescent polymerase chain reaction primers for human identity markers. Blood. 1995;85:1954–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomson KJ, Morris EC, Milligan D, Parker AN, Hunter AE, Cook G, Bloor AJ, Clark F, Kazmi M, Linch DC, Chakraverty R, Peggs KS, Mackinnon S. T-cell-depleted reduced-intensity transplantation followed by donor leukocyte infusions to promote graft-versus-lymphoma activity results in excellent long-term survival in patients with multiply relapsed follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Aug 10;28(23):3695–3700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9100. Epub 2010 Jul 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vigouroux S, Michallet M, Porcher R, et al. Long-term outcomes after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for low-grade lymphoma: A survey by the French Society of Bone Marrow Graft Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Haematologica. 2007;92:627–634. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Avivi I, Montoto S, Canals C, et al. Matched unrelated donor stem cell transplant in 131 patients with follicular lymphoma: An analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Br J Haematologica. 2009;147:719–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rezvani AR, Storer B, Maris M, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in relapsed, refractory, and transformed indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:211–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hari P, Carreras J, Zhang MJ, et al. Allogeneic transplants in follicular lymphoma: Higher risk of disease progression after reduced-intensity compared to myeloablative conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen S, Busque L, Kiss T, et al. Tandem Autologous-Allogeneic Nonmyeloablative Sibling Transplant in Relapsed Follicular Lymphoma Leads to Impressive Progression Free Survival with Minimal Toxicity. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.11.028. Abstract 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mandigers CM, Verdonck LF, Meijerink JP, et al. Graft-versus-lymphoma effect of donor lymphocyte infusion in indolent lymphomas relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:1159–1163. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tam CS, Bassett R, Ledesma C, et al. Mature results of the MD Anderson Cancer Center risk-adapted transplantation strategy in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;113:4144–4152. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]