SUMMARY

Retinal ganglion cells adapt by reducing their sensitivity during periods of high contrast. Contrast adaptation in the firing response depends on both presynaptic and intrinsic mechanisms. Here, we investigated intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation in OFF Alpha ganglion cells in the in vitro guinea pig retina. Using either visual stimulation or current injection, we show that brief depolarization evoked spiking and suppressed firing during subsequent depolarization. The suppression could be explained by Na channel inactivation, as shown in salamander cells. However, brief hyperpolarization in the physiological range (5–10 mV) also suppressed firing during subsequent depolarization. This suppression was sensitive selectively to blockers of delayed-rectifier K channels (KDR). Somatic membrane patches showed TEA-sensitive KDR currents with activation near −25 mV and removal of inactivation at voltages negative to Vrest. Brief periods of hyperpolarization apparently remove KDR inactivation and thereby increase the channel pool available to suppress excitability during subsequent depolarization.

INTRODUCTION

The visual system adjusts its sensitivity depending on the history of light stimulation, a property known as adaptation. In the retina, cellular responses adapt to several statistics of the visual input, including the mean light level, variation around the mean (or ‘contrast’) and higher correlations over space and time (Demb, 2008; Rieke and Rudd, 2009; Gollisch and Meister, 2010). Retinal ganglion cells, the output neurons, adapt to contrast presented within both well-controlled laboratory stimuli and more natural stimuli (Lesica et al., 2007; Mante et al., 2008). Contrast adaptation improves signal processing, because it enables high sensitivity when the input is weak and prevents response saturation when the input is strong (Shapley and Victor, 1978; Victor, 1987; Chander and Chichilnisky, 2001). Furthermore, contrast adaptation enhances information transmission at low contrast (Gaudry and Reinagel, 2007a). In the retina, a major goal is to understand how contrast adaptation arises in the circuitry, at the level of synapses and intrinsic membrane properties.

Contrast adaptation has been studied in several cell types of salamander retina, including cone photoreceptors and two of their postsynaptic targets: horizontal and bipolar cells. Neither cones nor horizontal cells adapt to contrast, and thus contrast adaptation first appears beyond the point of cone glutamate release (Baccus and Meister, 2002; Rieke, 2001). Bipolar cells, the excitatory interneurons that transmit cone signals to ganglion cells, do adapt to contrast (Baccus and Meister, 2002; Rieke, 2001). The bipolar cell’s contrast adaptation is reflected in the excitatory membrane currents and membrane potential (Vm) of ganglion cells (salamander: Baccus and Meister, 2002; Kim and Rieke, 2001; mammal: Beaudoin et al., 2007; 2008; Manookin and Demb, 2006; Zaghloul et al., 2005). However, this presynaptic mechanism for contrast adaptation explains only a portion of the adaptation in the ganglion cell’s firing rate (Kim and Rieke, 2001; Zaghloul et al., 2005; Manookin and Demb, 2006; Beaudoin et al., 2007; 2008). Thus, the presynaptic mechanism combines with intrinsic mechanisms within the ganglion cell to reduce sensitivity during periods of high contrast. In dim light, where signaling depends on rods and rod bipolar cells, contrast adaptation depends predominantly on the ganglion cell’s intrinsic mechanism (Beaudoin et al., 2008).

In theory, an intrinsic mechanism for contrast adaptation should sense changes in Vm during high contrast exposure. During high contrast, a ganglion cell’s Vm spans a wide range and includes periods of both hyperpolarization (up to ~10 mV) and depolarization (up to ~20 mV) from the resting potential (Vrest); the depolarizations are accompanied by increased firing. The duration of hyperpolarizations and depolarizations are determined by the temporal filtering of retinal circuitry, which under light-adapted conditions shows band-pass tuning with peak sensitivity near ~8 Hz; this tuning results in brief periods of depolarization and firing (~50–100 msec) that are themselves separated by ~100–200 msec (Berry et al., 1997; Zaghloul et al., 2005; Beaudoin et al., 2007). Therefore, an intrinsic mechanism that suppresses firing at high contrast should recover with a time course longer than the interval between periods of firing; in this way, firing in one period could activate a suppressive mechanism that would affect the subsequent period.

One intrinsic mechanism for adaptation was discovered in isolated salamander ganglion cells. A period of depolarization and spiking caused Na channel inactivation and resulted in a smaller pool of available channels during subsequent periods of excitation (Kim and Rieke, 2001; 2003). Channel inactivation recovered with a time constant of ~200 msec, and thus one period of depolarization could influence the next period. During prolonged high variance current injection (i.e., a substitute for high contrast stimulation), a steady pool of inactive channels accumulated, resulting in a tonic suppression of excitability.

Here, we investigated this Na channel mechanism and also investigated additional intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation in intact mammalian ganglion cells. We focused on a well-characterized cell type, the OFF Alpha cell, which shows both presynaptic and intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation (Shapley and Victor, 1978; Zaghloul et al., 2005; Beaudoin et al., 2007; 2008). We studied intact cells in light-sensitive tissue, where channels in both the soma and dendrites could contribute, and where the cell type could be targeted and confirmed based on its soma size, physiological properties and dendritic morphology (Demb et al., 2001; Manookin et al., 2008). In addition to Na channel inactivation, we found a second mechanism that contributes to contrast adaptation. This mechanism involves a common voltage-gated K channel, the delayed rectifier (KDR). Brief periods of hyperpolarization in the physiological range (~10 mV negative to Vrest) suppressed subsequent excitability during a depolarizing test pulse or contrast stimulus. The suppressive effect of hyperpolarization lasted for ~300 msec. Pharmacological experiments and somatic patch recordings linked the mechanism to KDR channels.

RESULTS

Excitability depends on the history of both membrane depolarization and hyperpolarization

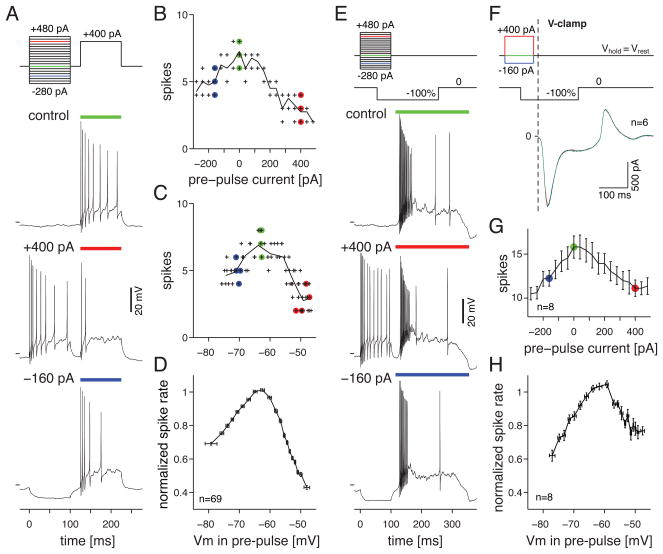

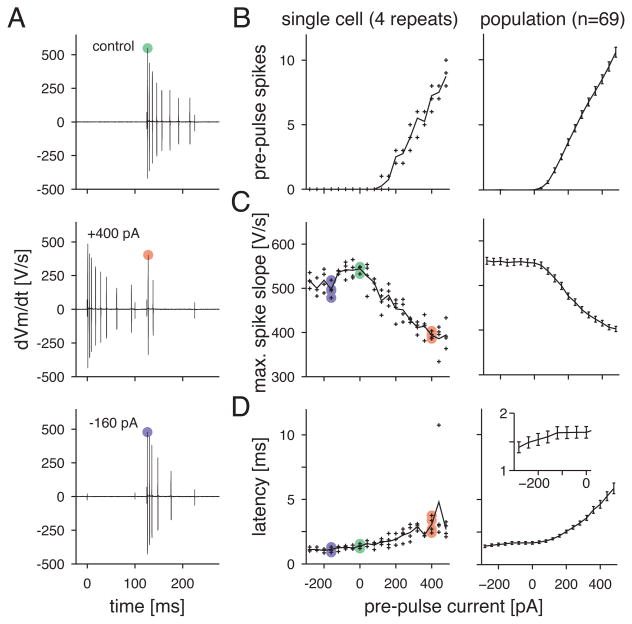

We first studied intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation in OFF Alpha cells using a paired-pulse current injection paradigm. The retinal circuit filters the visual input to emphasize temporal frequencies in the range of ~5–10 Hz (Zaghloul et al., 2005), and thus the relevant time scale for direct stimulation in our experiments is in the range of ~50–100 msec (i.e., a half-period of 5–10 Hz). In the basic experiment, a cell was recorded in current-clamp in the whole-mount retina in the presence of a background luminance and intact synaptic input (see Experimental Procedures). A hyperpolarizing or depolarizing current was injected during a pre-pulse (100 msec). The membrane was allowed to return to Vrest (~−65 mV) during a 25 msec inter-pulse interval, and then depolarizing current was injected during a test-pulse (+400 pA, 100 msec). Firing to the test pulse was suppressed by both depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses (Figure 1A). Plotting the spike number, measured over the duration of the test pulse, as a function of pre-pulse current showed a peak in firing around the baseline condition (pre-pulse = 0 pA) with suppression for both negative and positive pre-pulse amplitudes (Figure 1B). In order to average across cells, each of which had slightly different Vrest and input resistance (Rin), we re-plotted the data as a function of Vm during the pre-pulse (Figure 1C). The number of spikes evoked by the test pulse peaked when the pre-pulse was near the average Vrest, and was suppressed by pre-pulses that evoked hyperpolarizations and depolarizations within the physiological range (−10 mV to +20 mV re Vrest) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses suppress firing during a depolarizing stimulus.

A. OFF Alpha ganglion cell response to current injection. Control shows the response to the test pulse alone (+400 pA). Lower traces show the test pulses preceded by either a depolarizing or hyperpolarizing pre-pulse. Horizontal line before each trace indicates −60 mV.

B. Across four trials, the number of spikes during the 100-msec test pulse is plotted against the current injected during the pre-pulse. Colored symbols indicate the conditions shown in A.

C. The firing rates from B. are plotted against the median Vm during the pre-pulse.

D. Population plot of test pulse firing rate versus pre-pulse Vm, normalized to the firing rate when the pre-pulse equaled the average Vrest (−65 mV; n = 69 cells). Error bars represent ±1 SEM across cells (y-dimension) or ±1 SD of binned Vm (x-dimension).

E. Same format as A., except the depolarizing test pulse was replaced by a −100% contrast step of a spot stimulus (0.4-mm diameter, centered on the cell body; background equaled the mean luminance). Stimulus timing allowed Vm to return to Vrest prior to the visual response (see Results). Colored bars indicate the period of analysis in G. and H.

F. Voltage-clamp recordings of the response to the spot stimulus in E. A cell was stimulated with pre-pulses in current clamp and then switched to voltage clamp to record synaptic input during the spot. Traces show the average across 6 cells.

G. The firing rate during the contrast response in E. is plotted against the current injection of the pre-pulse (n=8 cells; error bars indicate ±1 SEM).

H. Population plot of the contrast response versus pre-pulse Vm, following the conventions in D. (n=8 cells).

Depolarization and hyperpolarization suppress subsequent firing to visual contrast

To test the physiological relevance of the pre-pulses in the above current-injection experiment, we substituted the test pulse with a visual stimulus: a spot (0.4-mm diameter) that decreased contrast by 100% (i.e., the mean luminance switched to black). The number of spikes evoked by the contrast stimulus peaked when the pre-pulse was near Vrest and was suppressed by pre-pulses that evoked hyperpolarizations or depolarizations (Figure 1E, G, H). Thus, pre-pulses evoked by current injection at the soma suppress subsequent visually-evoked, synaptically-driven responses originating at the dendrites.

We tested whether the pre-pulse and associated change in Vm and firing rate could have fed back through the circuitry (i.e., through gap junctions with inhibitory amacrine cells) to suppress the visual response. We injected either hyperpolarizing or depolarizing pre-pulses in current clamp, as above, and then switched to voltage clamp to record contrast-evoked synaptic currents (Vhold near Vrest, ~−65 mV). Under these conditions, the pre-pulses had essentially no effect on the synaptic input (Figure 1F) suggesting that the effect of pre-pulses on the firing response to contrast depends on intrinsic properties of the ganglion cell and does not involve feedback onto presynaptic neurons.

Depolarization and hyperpolarization suppress subsequent excitability for hundreds of msec

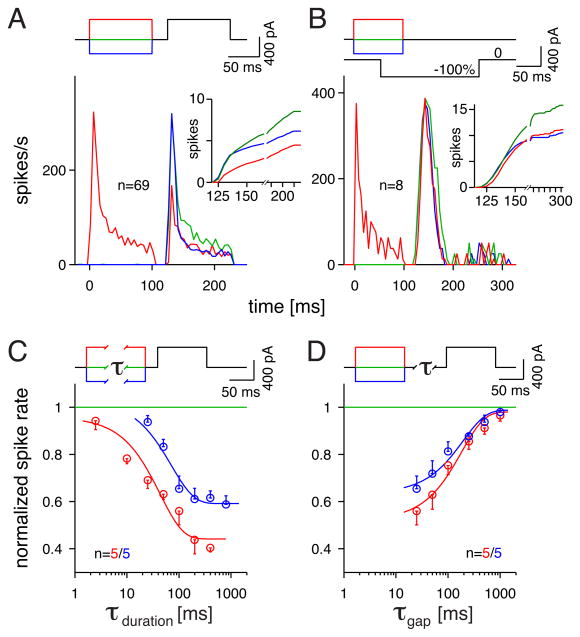

Depolarization and hyperpolarization typically stimulate different sets of voltage-gated channels, and so it seemed likely that the suppressive effects observed by depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses depended on separate mechanisms. Indeed, the time course of suppression differed following the two classes of pre-pulse. In most experiments below, pre-pulse current injections were designed to change Vm within the physiological range: +400 pA versus −280 pA, which typically evoked +15 mV versus −10 mV changes in Vm. A depolarizing pre-pulse suppressed firing to the test pulse across the entire test pulse duration, whereas a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse suppressed only the late firing to the test pulse (Figure 2A). The time course of the suppressive effects can be visualized in cumulative firing rate plots for each stimulus (Figure 2A, inset). We performed a similar analysis in the case where visual contrast replaced the test pulse. In this case, the depolarizing pre-pulse suppressed firing to contrast across the duration of the response, whereas a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse suppressed primarily the late firing (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. The suppressive actions of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing pre-pulses show different time courses.

A. The firing rate to a test pulse preceded by a depolarizing pre-pulse (+400 pA, red), a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (−280 pA, blue) or no pre-pulse (control condition, green). Post-stimulus time histograms (PSTHs) show the average of 69 cells (2–4 trials/cell). Inset shows the cumulative firing to the test pulse; early response is shown at a finer time scale than the later response (tick marks every 25 msec).

B. Same format as A., except the test pulse was replaced by a −100% contrast step (stimulus described in Figure 1E.).

C. Suppressive effects of various pre-pulse durations (n = 5 cells). Suppression mediated by depolarizing (red) or hyperpolarizing pre-pulses (blue) is plotted relative to the firing in the control condition (no pre-pulse). Error bars show SEM across cells (n = 5). Smooth lines show exponential fits to the two activation rates with half-maximal effects at 44 ms (depolarization) or 71 ms (hyperpolarization).

D. Recovery of the suppressive effects of pre-pulses for various inter-pulse intervals (τ). Smooth lines show exponential fits to the two recovery rates (see Results). Error bars show SEM across cells (n = 5).

We next varied the duration of the pre-pulse to determine how much time was required to generate a suppressive effect. Depolarizing pre-pulses suppressed firing even following short pre-pulse durations (<5 msec) that evoked only a single spike, whereas hyperpolarizing pre-pulses suppressed firing only following longer pre-pulse durations (>20 msec) (Figure 2B). Thus, the differences in the time dependence on pre-pulse duration suggest that depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses act by different mechanisms.

As discussed above (see Introduction), an intrinsic mechanism that suppresses firing at high contrast should recover with a time course longer than the interval between periods of firing; in this way, firing in one period could activate a suppressive mechanism that would affect the subsequent period (i.e., >100 msec recovery). We therefore examined the recovery of suppression following depolarizing or hyperpolarizing pre-pulses. Both types of pre-pulse suppressed firing and required >300 msec for complete recovery (Figure 2C). The fitted half maximum time constants for recovery were 182 msec and 195 msec for depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses, respectively. Thus, both hyperpolarization and depolarization can suppress subsequent excitability and have the appropriate recovery time to contribute to contrast adaptation to physiological stimuli.

Both depolarization and hyperpolarization reduce the gain of excitatory responses

We tested the influence of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses on the complete input-output function of the test pulse response. We varied test pulse amplitude to mimic different contrast levels (up to +480 pA). The current-firing (I-F) relationship during the test pulse was measured under control conditions (pre-pulse, 0 pA) and in the two pre-pulse conditions (+400, −160 pA). The I-F relationships were relatively linear and could therefore be characterized by a slope and an offset (Figure 3A). Both types of pre-pulse suppressed the firing by reducing the slope, indicating a reduction in gain (Figure 3B). However, there were different effects on the offset (Figure 3C). The depolarizing pre-pulse increased the offset, so that a larger test-pulse was required to evoke spiking. The hyperpolarizing pre-pulse decreased the offset, so that in most cases the firing near threshold was slightly enhanced by the pre-pulse, and the suppression of firing occurred primarily for the largest test pulses. Thus, hyperpolarizing pre-pulses suppress subsequent firing primarily for strong stimuli; whereas depolarizing pre-pulses suppress subsequent firing for all stimuli.

Figure 3. Depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses reduce response gain.

A. Firing rate during test pulses of variable current amplitude (+80 to +480 pA) were suppressed by either depolarizing (+400 pA, red) or hyperpolarizing pre-pulses (−160 pA, blue). Responses could be fit by a line, defined by an offset on the x-axis and a slope.

B. Upper panel shows the average slope across cells in each condition (error bars indicate SD across cells, n = 18). Lower panel shows the difference between each pre-pulse condition and the control condition (error bars indicate SEM across cells).

C. Same format as B. for the effect of pre-pulses on the offset of the I-F function.

D. Average, normalized firing rate to stimuli of various negative contrasts (9–100%) under control conditions (no pre-pulse, green) and following either a depolarizing (red) or hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (blue). Stimulus timing was designed to evoke firing at approximately the same time following the pre-pulses (i.e., lower contrasts presented earlier). Responses are normalized to the maximum firing rate under control conditions. Error bars indicate SEM across cells (n = 10). Stimulus was a 1-mm diameter spot, centered on the cell body (dark background).

E. Average PSTH to spot stimuli at three contrast levels under control conditions (no pre-pulse, green) and following either a depolarizing (red) or hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (blue) (n = 10).

We repeated the above experiment substituting different contrast levels for the test pulse: a spot (1-mm diameter) that decreased contrast by variable amounts (9–100%). We varied the timing of stimulus onset so that lower contrast stimuli occurred earlier in time; this ensured that firing at all contrast levels would begin ~25 msec following pre-pulse offset (see Experimental Procedures; Figure 3D). The contrast response function measured under control conditions (pre-pulse, 0 pA) was suppressed when the visual stimulus was preceded by either depolarizing or hyperpolarizing pre-pulses (Figure 3D). However, the two forms of suppression differed. The depolarizing pre-pulse shifted the contrast response function rightward on the log-contrast axis and thereby suppressed the response to all contrasts; whereas the hyperpolarizing pre-pulse suppressed mostly the response to high contrasts (Figure 3D). Furthermore, the time course of suppression differed for the two pre-pulses, as is illustrated most clearly at high contrast (Figure 3E). The depolarizing pre-pulse suppressed the spike rate during the entire responses; whereas the hyperpolarizing pre-pulse suppressed the spike rate during the late phase of the response.

Visually-evoked hyperpolarization suppresses firing to subsequent visually-evoked depolarization

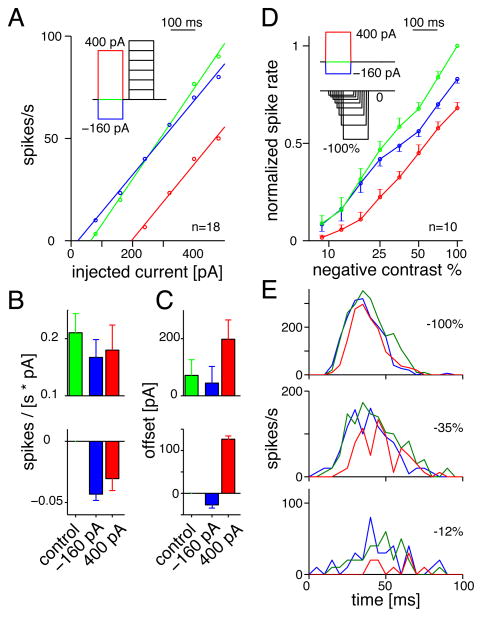

To demonstrate further the physiological relevance of the suppressive effect of hyperpolarization, we used a purely visual paradigm to generate periods of hyperpolarization and depolarization. Sinusoidal contrast modulation of a spot was presented for four seconds. In one condition, the cell responded naturally for the first two seconds and then switched to a clamped state, where dynamic current injection prevented stimulus-evoked hyperpolarization (Figure 4A). In a second condition, the cell started in the clamped state and then switched to the un-clamped state. At certain stimulus frequencies, the response was suppressed in the un-clamped state, suggesting that visually-evoked hyperpolarization normally suppresses firing during subsequent periods of depolarization. The level of response ‘crossed over’ after two seconds, when the recording state switched on each trial (Figure 4B, gray line).

Figure 4. Firing rate is suppressed following periods of hyperpolarization evoked by visual contrast.

A. Ganglion cell response to 3-Hz sinusoidal contrast modulation of a spot (0.4-mm diameter, background equal to the mean luminance). Black trace shows the response to the first cycle and to the sixth and seventh cycles. Between the sixth and seventh cycles (at 2 sec; vertical gray line), the cell switched (‘S’) from an un-clamped state (‘U’) to a clamped state (‘C’), where dynamic current injection prevented stimulus-evoked hyperpolarization. Red trace shows the same cell, but the recording started in the clamped state and then switched to the un-clamped state. Lowest panel shows injected current. Horizontal line before each voltage trace indicates −60 mV.

B. The average number of spikes during each cycle at 3 Hz is plotted over time (n = 10 cells; error bars here and in C. and D. indicate SEM across cells). Recordings started in either the un-clamped state (black) or clamped state (red) and then switched states after two sec (gray line).

C. Average firing rate during the first stimulus cycle in the clamped (red, C1) or un-clamped states (black, U1) over a range of temporal frequencies (n = 10 cells).

D. Average firing rate during the final stimulus cycle preceding the switch (red, CS−1; black, US−1).

E. Points show the percentage decrease in firing during the un-clamped state compared to the clamped state. Blue points show this comparison for the first stimulus cycle: (U1−C1)/C1; green points show this comparison for the two cycles surrounding the switch between states: [(US−1 − CS+1) + (US+1 − CS−1)]/(CS−1 + CS+1). Error bars indicate ±1 SEM across cells (n = 10).

We quantified the suppressive effect of contrast-evoked hyperpolarization on the firing rate as a function of temporal frequency. For the initial stimulus period, the response was suppressed across a wide frequency range (Figure 4C). There was a significant decrease in firing in the un-clamped state (expressed as a percentage difference from firing in the clamped state) between 2 and 10 Hz (Figure 4E, p<0.01 at each frequency). Thus, at the switch from mean luminance (i.e., 0% contrast) to high contrast modulation, hyperpolarization preceding the initial depolarization was generally suppressive. Following two seconds of stimulation, the initial firing rate adapted to a steady rate (illustrated for the 3 Hz stimulus; Figure 4B). At this point, the hyperpolarizations had a smaller suppressive effect on subsequent depolarization (Figure 4D) and depended more on the temporal frequency of modulation; suppression was observed in the 2–5 Hz range (Figure 4E; p<0.01 for 2–3 Hz; p<0.05 for 5 Hz; n=10). Thus, the suppressive effect of hyperpolarization on subsequent firing could be evoked by visual contrast stimuli but was frequency dependent.

Depolarizing pre-pulses suppress subsequent excitability by inactivating Na channels

We next turned to the mechanisms for the suppressive effects of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing pre-pulses. Based on an earlier study in isolated salamander ganglion cells, we hypothesized that Na channel inactivation would explain the suppression following depolarizing pre-pulses and the accompanying spiking (Kim and Rieke, 2001; 2003). We could not measure Na currents directly from intact ganglion cells, and we were not successful in preparing nucleated patches. However, we could gauge Na channel availability in the intact cell by measuring the spike slope (Colbert et al, 1997).

In response to depolarizing current injection, the maximum spike slope declined during the burst, presumably because fewer Na channels were available on each subsequent spike (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the initial spike slope during the test pulse was suppressed following depolarizing pre-pulses (+400 pA; Figure 5A). Across cells, the firing rate during the depolarizing pre-pulse increased roughly linearly with current amplitude (Figure 5B). In the same recordings, the slope of the first action potential during the test pulse decreased linearly (Figure 5C). Thus, there was an approximately linear relationship between the spike number during the pre-pulse and the apparent number of available Na channels at the beginning of the subsequent test pulse (i.e., as reflected by the maximum slope of the first action potential). Consistent with this interpretation, the spike latency during the test pulse increased with the current amplitude of the pre-pulse (Figure 5D). However, hyperpolarizing pre-pulses had no consistent effect on spike slope during the test pulse (Figure 5C); comparing within cells, there was only a trend toward a higher spike slope following a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (p < 0.11), which may indicate a small increase in the availability of Na channels. There was a small but significant decrease (p < 0.001, compared within cells) in the spike latency following a strong hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (Figure 5D, inset); this may be explained by an increased availability of Na and voltage-gated Ca channels, but we did not investigate this further.

Figure 5. Evidence that depolarizing pre-pulses suppress subsequent firing due to Na channel inactivation.

A. The derivative of the voltage response in the control and two pre-pulse conditions. The maximum slope of the initial action potential during the test pulse is suppressed by a preceding depolarizing pre-pulse. Data are from the recordings shown in Figure 1A.

B. Firing rate to each level of the pre-pulse for one cell (left, four trials) and for the population (right; error bars in B. and D. show ±1 SEM across cells, n = 69).

C. Same format as B. for the maximum slope of the first spike during the test pulse.

D. Same format as B. for the latency between test pulse onset and the first spike. Inset at right shows, on an expanded scale, a decreased spike latency following the most negative current injections.

Suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses does not depend on Ih or Ca channels

We next turned to the mechanism for the suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses. A potential mechanism could be the hyperpolarization-activated current Ih, associated with CNG channels (Lee and Ishida, 2007; Gasparini and DiFrancesco, 1997). To test for the involvement of Ih, we measured the effect of pre-pulses in the presence of the channel blocker ZD7288 (25 μM). For this drug, and all others described below, we show the drug’s effect on basic physiological properties compared to the control state for the same sample of cells and compared to the larger sample of control recordings (n = 69 cells; Figure 6C). ZD7288 had little effect on basic physiological properties. Furthermore, both hyperpolarizing and depolarizing pre-pulses continued to suppress subsequent firing to a test pulse in the presence of the drug (Figure 6BI). These results suggest that Ih does not mediate the suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses. Indeed, we did not observe a prominent sag during the ~10 mV hyperpolarizations evoked by the pre-pulse. As a positive control, we found that an apparent Ih observed under voltage clamp in control conditions was blocked by ZD7288 (Figure 6BI, inset).

Figure 6. The suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses does not depend on Ih, CaV or KCa channels.

A. Example responses to +400 pA current injection (0–100 msec) under control conditions (black) and in the presence of a channel blocker (red): Ih (ZD 7288, 25 μM), T-type Ca channel (Mibefradil, 10 μM), BK channel (Charybdotoxin, 20 nM; Paxilline, 200 nM) and SK channel (Apamin, 2.5 μM). Horizontal line before each trace indicates −60 mV.

B. Normalized firing rate versus pre-pulse Vm in each drug condition (red) versus control condition in the same cells (black; see Figure 1D). Error bars show ±1 SEM across cells (n = 4–6 per condition). Inset in first row shows that ZD 7288 blocks a hyperpolarization-activated inward current (arrow) under voltage clamp (voltage step from −70 mV to −110 mV and back to −70 mV). Inset in second row shows that, shortly after wash in, Mibefradil blocks an inward current (arrow) under voltage clamp (activated by a voltage step to −60 mV following a hyperpolarizing step to −90 mV).

C. Basic membrane and firing properties in each drug condition. For each group of cells, the spike width (SW), resting potential (Vrest), input resistance (Rin) and maximum firing rate to +400 pA current injection (FR) are plotted for the control (black) and drug condition (red). Error bars indicate SD across cells. For each measure, the gray horizontal bar indicates the mean ± 1 SD range across a large sample of cells under control conditions (n = 69).

We next tested whether Ca channels were involved in the suppression caused by hyperpolarizing pre-pulses, either directly or indirectly via activation of Ca-activated K (KCa) channels. We first blocked all voltage-gated Ca channels with cobalt (2 mM). This condition hyperpolarized the membrane (~5 mV) and relatively large currents were required to evoke spiking. This requirement for large currents may have been caused by the block of T-type channels or by a shift in activation threshold for KDR channels (Mayer and Sugiyama, 1988; Margolis and Detwiler, 2007). Using a larger range of pre-pulse amplitudes (−560 to +800 pA) and a larger test pulse (+800 pA), we still observed both forms of suppression on the test pulse, indicating that Ca channels are not mediating either effect. Nevertheless, because the firing properties were altered so dramatically by cobalt, we tested several other specific blockers.

Several types of Ca or KCa channels were blocked selectively to test for a role in the suppression by hyperpolarizing pre-pulses. T-type Ca channels were blocked by mibefradil (10 μM). This blocker is not entirely specific to Ca channels (Eller et al. 2000), because it also lowers the activation and inactivation threshold for voltage gated K channels (Perchenet and Clement-Chomiene, 2000; Chouabe et al., 1998; Yoo et al., 2008). Nevertheless, there was essentially no impact on the suppressive effect of the pre-pulses (Figure 6AII, BII). As a positive control, an apparent T-type ICa observed under voltage clamp in control conditions was blocked by mibefradil (Figure 6BII, inset).

We tested KCa channel blockers, including two BK blockers (Charybdotoxin, 20 nM; Paxilline, 200 nM) and an SK blocker (Apamin; 2.5 μM). Charybdotoxin increased the spike rate evoked by a +400 pA test pulse (Figure 6C). However, both hyperpolarizing and depolarizing pre-pulses suppressed firing during the test pulse under all conditions (Figure 6BIII–V). In each case, we compared drug versus control conditions for normalized firing rates following hyperpolarizations to −75±5 mV; of all the drugs tested, the largest effect on the hyperpolarizing pre-pulse was observed in the presence of charybdotoxin (p<0.12; n=5; 6BIII). However, because paxilline, a more selective antagonist of BK channels (Rauer et al., 2000; Grissmer et al., 1994), had no effect (Figure 6BIV), we questioned the specificity of charybdotoxin and proceeded to test the involvement of other K channels.

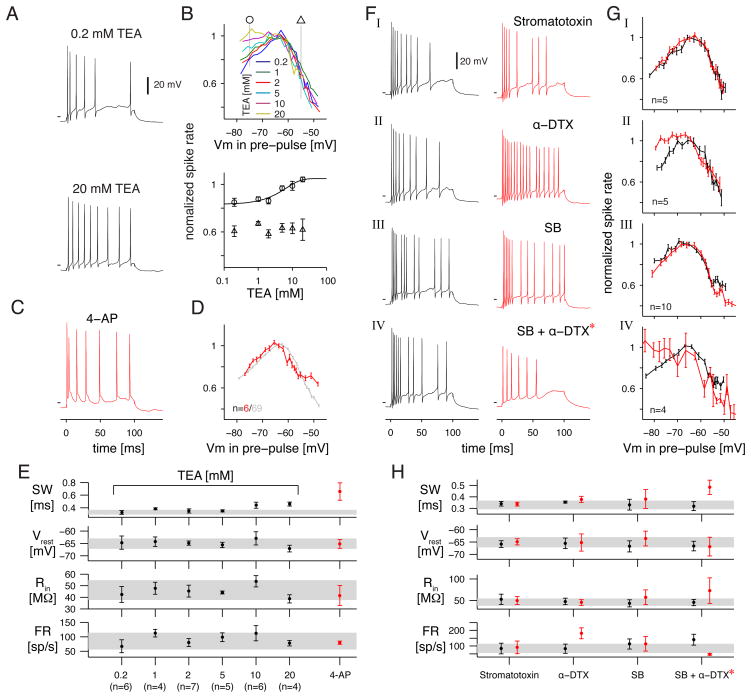

Suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses depends on a TEA- and α-dendrotoxin-sensitive delayed-rectifier K channel

We next asked whether the mechanism for the suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses could be explained by a voltage-gated K (KV) channel. A useful tool for determining KV channel involvement is the general blocker TEA. However, adding TEA to the bath caused oscillations in Vm due presumably to altered synaptic release from presynaptic bipolar and amacrine cells (not shown). Therefore, we applied TEA intracellularly by adding it to the pipette solution (and increased the osmolarity of the extracellular solution by the same amount with glucose). Intracellular TEA caused little change in basic properties aside from an increase in spike width at higher concentrations (Figure 7E). At 20 mM, internal TEA had no effect on the action of the depolarizing pre-pulse but completely suppressed the action of the hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (Figure 7B). We measured TEA’s suppression of the hyperpolarizing pre-pulse effect at six levels of intracellular TEA (i.e., six different pipette solutions tested in different cell groups). A half-maximum effect was achieved at 7.4 mM TEA (Figure 7B). This result suggests that the suppression of firing by a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse is mediated by a KV channel.

Figure 7. The suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses depends on a TEA- and α-dendrotoxin-sensitive K channel.

A. Example responses to +400 pA current injection (0–100 msec) with recording solution that contained either 0.2 or 20 mM TEA. Horizontal line in A., C. and F. indicates −60 mV.

B. upper panel: Normalized firing rate versus pre-pulse Vm with various levels of TEA added to the pipette solution (0.2 to 20 mM; see Figure 1D).

lower panel: Normalized spike rate for conditioning pre-pulses that depolarized the cell to −55 mV (triangles) or hyperpolarized the cell to −75 mV (circles) plotted against the TEA concentration. The line shows an exponential fit to the spike rates following hyperpolarization (circles; error bars show ±1 SEM across cells, n = 4–7 per condition). The suppression of spike rate following depolarizing pre-pulses was not affected by TEA concentration (triangles).

C. Example responses to +400 pA current injection (0–100 msec) with 4-AP added to the pipette solution (200 μM).

D. Normalized firing rate versus pre-pulse Vm in the presence of 4-AP. Data from control cells (n = 69) are shown for comparison.

E. Basic membrane and firing properties for recordings with various levels of either TEA or 4-AP in the pipette solution. Same format as Figure 6C.

F. Example responses to +400 pA current injection (0–100 msec) under control conditions (black) and in the presence of a Kv2 channel blocker (Stromatotoxin, 1 μM), a Kv1 channel blocker (α-Dendrotoxin, 70 nM) and synaptic blockers (SB: strychnine, 100 μM; gabazine, 10 μM; CNQX, 100 μM; D-AP-5, 100 μM; L-AP-4, 100 μM). In the fourth row, the SB condition served as the control and α-Dendrotoxin (70 nM) was the drug condition (*, the current injection was reduced to +200 pA in the SB+ α-Dendrotoxin condition).

G. Normalized firing rate versus pre-pulse Vm in each drug condition (red) versus control (black). Error bars show ±1 SEM across cells (4–10 per condition).

H. Basic membrane and firing properties for each condition in F. and G. Same format as part E.

We explored further the Kv channel involved in hyperpolarization-mediated spike suppression through additional pharmacological experiments. We tested for a role of fast inactivating KV channels (e.g., A-type and D-type) by adding the blocker 4-AP (Storm, 1993). Initially, we added 4-AP to the extracellular solution (1–2 mM), but this produced large oscillations of Vm, presumably mediated by presynaptic effects. We therefore added 0.2 mM 4-AP to the pipette solution. This concentration blocked the after-hyperpolarization (AHP) following a spike and dramatically increased the spike width (Figure 7E), but had little effect on the suppressive effects of hyperpolarizing or depolarizing pre-pulses (Figure 7D). Higher concentrations of 4-AP (2 mM) led to dramatically altered spiking and oscillatory depolarizations which precluded the main analysis (data not shown). Thus, fast inactivating Kv channels are responsible for the after-hyperpolarization following a spike but not the suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses. Consistent with this interpretation, the hyperpolarizing pre-pulses, under control conditions, seemed to have no effect on the after-hyperpolarization following a spike.

We tested the involvement of KDR channels by applying the Kv2-specific blocker stromatotoxin (1 μM; Escoubas et al., 2002). This drug had no effect on basic physiological properties (Figure 7FI, H) and did not block the suppressive effect of either type of pre-pulse (Figure 7G1). We next tested the involvement of Kv1 channels by applying the specific blocker α-Dendrotoxin (70 nM; Harvey, 2001; Scott et al., 1994): a pore blocker of channels that contain Kv1.1 Kv1.2 or Kv1.6 subunits (Harvey 2001), which have been found in ganglion cells (Pinto and Klumpp 1998; Holtje et al 2007). This drug increased the maximum firing rate (p<0.001), tended to increase spike width slightly (p < 0.11, n=5) (Figure 7FII, H) and lead to mild Vm oscillations but did not increase Rin (Figure 7H). In addition, the drug blocked the action of the hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (p<0.005 n=5; Figure 7G2).

We tested whether the positive effect of α-Dendrotoxin could be explained by an action at a presynaptic site in the retinal network. Thus, we repeated the experiment after first blocking ON bipolar cell pathways (L-AP-4), AMPA- and NMDA-type glutamate receptors (CNQX, D-AP-5), and GABA-A (gabazine) and glycine receptors (strychnine; see Figure legend for drug concentrations). These blockers, on their own, increased Rin (p<0.005) and tended to increase the spike width (p<0.07, n=10; Figure 7H) but did not block the effect of either hyperpolarizing or depolarizing pre-pulses (Figure 7G3). The blockers also induced mild oscillations of Vm. Adding α-Dendrotoxin to the blockers increased the oscillations dramatically, making it difficult to obtain isolated responses to injected current. Furthermore, the excitability was increased under this condition, necessitating a lower level of test pulse current (+200 pA instead of +400 pA). Nevertheless, the average of four cells showed that α-Dendrotoxin blocked the suppressive effect of hyperpolarizing pre-pulses under conditions with most synapses blocked (p<0.005 n=4; Figure 7GIV).

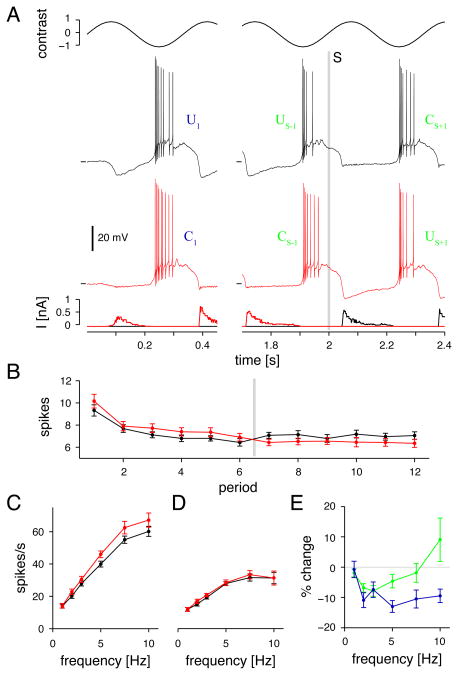

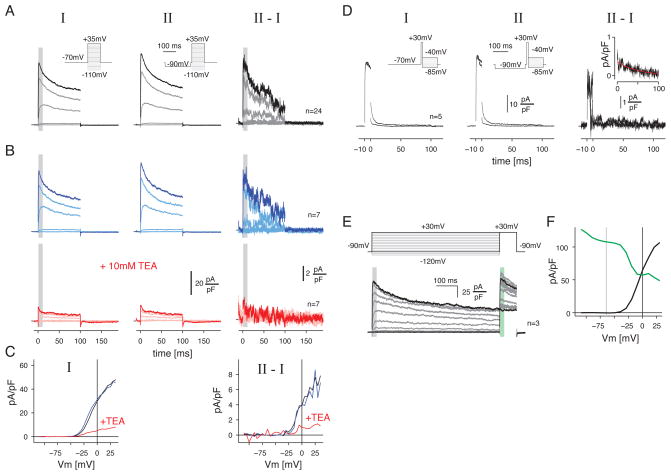

Somatic membrane patches show a KDR current that could explain the suppressive effect of membrane hyperpolarization on subsequent firing

We recorded currents in somatic membrane patches to characterize the properties of KDR channels (see Experimental Procedures). Patches were held at −70 mV and then stepped to a series of potentials (−110 to +35 mV). From a population of patches, we recorded outward currents activated at Vm positive to ~−35 mV (Figure 8A, C). These currents were enhanced following a 20 mV hyperpolarizing pre-pulse (Figure 8A). The difference between the conditions showed an outward current activated at Vm positive to ~−25 mV (Figure 8C). This difference current activated rapidly (<0.5 msec at Vholds between −10 and +35 mV), and inactivated to half the maximum level in <100 msec (Figure 8A). We tested the effect of TEA in a subset of patches (n = 7), and found that all currents were suppressed. In most cases, we were not able to record long enough to reverse the effect of TEA, although in one case we measured partial recovery (~30%). Thus, these currents showed characteristic activation properties and TEA-sensitivity of KDR channels (Storm, 1993; Baranauskas, 2007).

Figure 8. Hyperpolarization from rest activates delayed rectifier currents in somatic patch recordings.

A. Somatic patch recordings of currents activated by voltage steps from −70 mV to potentials ranging from −110 to +35 mV. The step was presented alone (I) or was preceded by a conditioning voltage step to −90 mV (II). The difference traces (II – I) show the currents sensitive to the hyperpolarizing step. Traces show the average across patches (n = 24) normalized by the capacitance (pA/pF).

B. Same format as A. for a subset of patches (n = 7) before (blue) and after (red) adding TEA (10 mM) to the bath medium.

C. The voltage-current relationship for series I and the difference curve, II – I. Points show the average during the times indicated by the gray bars in A. and B. The current evoked by positive steps from −70 mV activated near −35 mV and was TEA sensitive. The current from the difference trace (II – I) activated near −25 mV and was TEA sensitive.

D. Voltage dependence of deactivation (n = 5 patches). Patches were stepped from −70 mV to +30 mV and then to potentials ranging from −85 to −40 mV; the steps to these extreme values are illustrated. The initial step to +30 mV was presented alone (I) or was preceded by a conditioning voltage step to −90 mV (II). The difference traces (II-I) show the currents sensitive to the hyperpolarizing step. Inset shows the average tail current at post-pulse potentials between −60 and −40 mV. Red line shows a fitted exponential with a time constant of 35 msec.

E. Steps to +30 mV were preceded by prolonged steps to potentials ranging from −120 to +30 mV. Both black traces show steps from −90 to +30 mV, indicating the stability of the recording over time (averaged over 3 patches).

F. The voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation of K currents measured in E. Activation (black line) and inactivation (green line) were measured over the time windows indicated in E. Inactivation of the K current can be removed at potentials negative to the typical −65 mV resting potential (left of the gray vertical line).

For the KDR current activated by preceding hyperpolarization, we measured the time course of deactivation. Patches (n = 5) were stepped from −70 mV to +30 mV for 10 msec (Figure 8D) and then to a series of potentials in the physiological range (−85 to −40 mV) without or with a preceding hyperpolarizing step (to −90 mV, 200 msec). The difference in the tail currents between the two conditions show deactivation of those KDR currents activated by the hyperpolarizing step. Deactivation (averaged over Vholds between −60 to −40 mV) was complete in ~100 msec, with a time constant of 35 msec (Figure 8D, inset).

The difference current in Figure 8A suggests that hyperpolarization from Vrest increases the availability of KDR channels. To explore further the voltage-dependence of inactivation, we made a pre-step to several potentials (−120 to +30 mV) followed by a test pulse to +30 mV, to activate all available channels (Figure 8E; n = 3 patches). The voltage-dependence of inactivation showed two components, consistent with the presence of at least two channel types (Figure 8F, green line). The rate of inactivation was high between −120 and −60 mV and again between −35 and −10 mV. Thus, a component of inactivation can be removed by hyperpolarization from Vrest. The collected pharmacology and somatic patch recordings suggest that a Kv1-family KDR channel mediates the suppressive effect of hyperpolarization on subsequent depolarization and firing in retinal ganglion cells and thereby contributes to an intrinsic mechanism for contrast adaptation.

DISCUSSION

The contrast adaptation observed in ganglion cell firing exceeds that present in the subthreshold Vm or excitatory membrane currents (Kim and Rieke, 2001; Zaghloul et al., 2005; Beaudoin et al., 2007; 2008). This discrepancy implicates intrinsic mechanisms for adaptation within ganglion cells (Gaudry and Reinagel, 2007b). Here, we demonstrate two distinct intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation in the OFF Alpha ganglion cell: Na channel inactivation and removal of delayed-rectifier K channel (KDR) inactivation. Importantly, both mechanisms act within the physiological range of Vm, and both mechanisms show the appropriate time-course to suppress visually-evoked firing during periods of high contrast. Below, we consider the evidence for these two mechanisms, their key properties for evoking adaptation, their interaction with each other and with synaptic inputs, and their presence in other retinal cell types and neural circuits.

Evidence for two distinct intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation within an intact mammalian ganglion cell

One intrinsic mechanism for contrast adaptation, Na channel inactivation, was identified originally in studies of isolated salamander ganglion cells of unknown type (Kim Rieke, 2001; 2003). In these cells, the Na current could be studied directly to characterize activation and inactivation properties. Slow recovery from inactivation (>200 msec) explained low output gain at high contrast because of the reduced pool of available Na channels, with little or no apparent involvement of Ca or K channels (Kim and Rieke, 2001; 2003). Our results show a similar Na channel mechanism in the intact OFF Alpha ganglion cell. The maximum slope of the action potential, a proxy measure of Na current, suggested reduced channel availability following periods of depolarization and firing (Figure 5). Furthermore, the suppressed firing persisted in the presence of multiple blockers of K and Ca channels, consistent with a Na channel mechanism (Figures 6–7).

We also identified a novel intrinsic mechanism for adaptation mediated by KDR channels. In intact cells, brief hyperpolarization within the physiological range (~10 mV negative to Vrest) reduced subsequent firing to a depolarizing test pulse or contrast stimulus (Figures 1–3). During contrast stimulation, blocking hyperpolarization by dynamic current injection removed the suppression of subsequent firing and enhanced the firing rate (Figure 4). The hyperpolarization-induced suppression of subsequent firing was blocked by internal TEA and by external α-dendrotoxin (Figures 6–7). Furthermore, somatic membrane patches showed characteristic properties of a KDR current (activation at ~−25 mV) and steady-state inactivation at Vrest could be removed by hyperpolarization (Figure 8). The collected results support a KDR mechanism, whereby hyperpolarizations from Vrest increase the available KDR channel pool and suppress firing during subsequent depolarization.

The study of intrinsic mechanisms for adaptation in intact cells and circuits is challenging and requires complementary experimental approaches. Some of these approaches yielded unexpected results worth mentioning. For example, external α-dendrotoxin increased firing significantly, while internal TEA (20 mM) did not (Figures 6–7), even though TEA is a more general blocker of K channels. However, TEA increased the spike width substantially. The increased spike width increases the time that unblocked K channels could be activated and also possibly leads to increased Na channel inactivation. Thus, unintended effects on K and Na channels may have counteracted any increase in firing rate caused by specifically blocking α-dendrotoxin-sensitive KDR channels. Another unexpected result was that hyperpolarizing current had no effect on subsequent firing to weak visual stimulation but enhanced slightly the firing to weak current injection (Figure 3). The distinct effects may be explained by the different time courses of the stimuli: the current injection was a square-pulse, whereas the low contrast synaptic input was necessarily more sluggish due to the filtering by retinal circuitry. However, in general, similar results were elicited by protocols that used either current injection or synaptic stimulation as the test stimulus (Figures 1–2, 4).

Critical properties of KDR channels for contrast adaptation

Somatic membrane patch recordings showed several properties of KDR currents that could explain their role in contrast adaptation. First, the channels activate at voltages traversed during an action potential (activation at −25 mV). Second, channel inactivation at Vrest could be removed by hyperpolarization (Figure 8). Thus, a period of hyperpolarization would increase the number of available channels, which could then be activated during a subsequent burst of firing. The initial spikes in the burst would be largely unaffected, but channels opened during these initial spikes would suppress subsequent spikes (Figure 2) because KDR deactivation is relatively slow (Figure 8D) compared to the typical inter-spike interval during the initial spike burst (Figure 1); Kv1 channels also contribute to the inter-spike interval in neocortical pyramidal cells (Guan et al., 2007). Furthermore, our whole-cell recordings showed that hyperpolarization for periods of >100 msec were most effective at suppressing subsequent firing (Figure 2). Therefore, the suppression following hyperpolarization should be tuned to temporal frequencies that both: drive hyperpolarization for 100 msec periods or longer (i.e., 5-Hz or lower) and drive a strong burst of firing during subsequent depolarization (i.e., above 1-Hz). This tuning was confirmed in contrast stimulation experiments, in which hyperpolarization-induced suppression was maximal in the ~2–5 Hz range (Figure 4).

Interaction between synaptic and intrinsic mechanisms for contrast adaptation

Under physiological conditions, there are opportunities for the two intrinsic mechanisms to interact. For example, hyperpolarization from Vrest could remove both KDR and Na channel inactivation. These two actions could have opposing effects on firing during subsequent depolarization. However, the increased Na channel availability induced by brief ~10 mV hyperpolarization seemed to be minor: the spike slope was barely enhanced by prior hyperpolarization, although the spike latency was decreased somewhat (Figure 5). Thus, physiological levels of hyperpolarization studied here appear to affect primarily the KDR channels. Furthermore, the AHP following each spike seemed insufficient for substantially removing inactivation of KDR currents that are inactivated at rest. Rather, inhibitory synaptic input to the ganglion cell would be necessary for prolonged (>100 msec) hyperpolarization of sufficient magnitude (~5–10 mV; Figure 4). For the OFF Alpha ganglion cell, such inhibitory input is conveyed primarily by the AII amacrine cell (Manookin et al., 2008; Murphy and Rieke, 2006; Münch et al, 2009; van Wyk et al., 2009). Suppressing bipolar cell glutamate release cannot generate substantial hyperpolarization, because the release is rectified (Demb et al., 2001; Liang and Freed, 2010; Werblin, 2010). Thus, direct synaptic inhibition serves not only to hyperpolarize Vm and counteract simultaneous depolarizing inputs (Münch et al., 2009) but also leads to a short-term memory of synaptic activity that influences excitability on a physiologically-relevant time scale.

Contrast adaptation in the ganglion cell firing rate is routinely quantified using a linear-nonlinear (LN) cascade model, in which the adaptation of an underlying linear filter is separated from the nonlinearity imposed by the firing threshold (Chander and Chichilnisky, 2001; Kim and Rieke, 2001; Zaghloul et al., 2005). While this model is useful for quantifying adaptation and explains much of the variance in the firing response (Beaudoin et al., 2007), it clearly confounds several underlying mechanisms. For local contrast stimulation, there are two major inputs to the OFF Alpha cell, bipolar input and AII amacrine cell input, and the adaptation in these inputs is distinct; both inputs show reduced gain at high contrast but the excitatory inputs exhibit a relatively larger speeding of response kinetics (Beaudoin et al., 2008). The two intrinsic mechanisms also show distinct tuning: the hyperpolarization-induced suppression contributes primarily at low temporal frequencies (Figure 4). Each synaptic or intrinsic mechanism for contrast adaptation contributes a ~10–20% gain reduction, so that the total reduction at high contrast is ~40–50% (Kim and Rieke, 2001; Beaudoin et al., 2007). Exploring detailed interactions between each of the mechanisms requires a more sophisticated biophysical model of the ganglion cell.

Comparison to other systems and cell types

To our knowledge, the paired-pulse current injection paradigm used here has not been explored extensively using hyperpolarizing pre-pulses in the physiological range. However, certain paradigms were similar and could be compared to ours. For example, in parasympathetic neurons (Fukami and Bradley, 2005), neostriatal neurons (Nisenbaum et al., 1994) and striatal neurons (Mahon et al., 2000) a period of hyperpolarization lead to decreased sensitivity and reduced spiking to subsequent depolarization. In these cases the suppression was explained by the activation of KV currents. However, the mechanism was apparently different from the one demonstrated in ganglion cells, because the previous effects were blocked by low concentrations of 4-AP (<0.2 mM; compare to Figure 7C, D). Experiments in pyramidal neurons of sensorimotor cortex (Spain et al. 1991) and the Hippocampus (Nistri and Cherubini 1991) also showed a suppressive effect of hyperpolarization on subsequent excitability. These effects may have been similar to the one shown here, because they were blocked by relatively high concentrations of 4-AP (>1 mM) and TEA (20 mM). However, in most cases, the previous experiments hyperpolarized cells beyond the physiological range (to ~−90 mV). Further experiments could determine whether milder hyperpolarization has a suppressive effect similar to the one shown here.

The suppressive actions of Na and KDR channels studied here can be distinguished from other mechanisms for adaptation of firing rate studied in cortical cells. For example, an adaptation of the firing mechanism was observed under conditions of visual stimulation that lead to tonic depolarization and decreased Rin (Cardin et al., 2008). However, this and related effects (Chance et al., 2002) show reduced gain of the firing mechanism measured in the presence of increased synaptic conductance. The mechanism we describe is apparently distinct: a change in the gain of the firing mechanism following a brief period of depolarization and hyperpolarization that would typically be evoked by a transient synaptic input. Both mechanisms may typically combine in intact cells under physiological conditions.

Each of the ~15–20 ganglion cell types likely expresses a unique combination of ion channels (Kaneda and Kaneko, 1991; Ishida, 2000; O’Brien et al., 2002; Margolis and Detwiler., 2007). Thus, it is possible that certain cell types lack one or both mechanisms for intrinsic adaptation shown here. For example, parvocellular-pathway (midget) ganglion cells in the monkey apparently show little or no contrast adaptation, and therefore they may have Na and K channel properties that do not produce adaptation (Benardete et al., 1992). Preliminary experiments on two other cell types in guinea pig, suggested that one (the OFF Delta cell) adapted to hyperpolarizing pre-pulses, whereas a second (the ON Alpha cell) did not. Future studies will be required to relate channel subunit expression to the two intrinsic mechanisms for adaptation demonstrated here.

KDR channels may play additional roles in adaptive behavior upstream of the ganglion cell. For example, in isolated salamander bipolar cells, these channels mediated adaptation to the mean membrane potential (Mao et al., 1998; 2002). At depolarized levels, the bipolar cells showed reduced gain and developed band-pass tuning to temporal inputs. Thus, within the retina KDR channels could play a role in adaptation to both the mean and the contrast of the visual input.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue preparation and electrophysiology

The experimental procedures have been described in detail previously (Beaudoin et al., 2008; Manookin et al., 2008). In each experiment, a Hartley guinea pig was dark adapted for >1 hour and then anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1), decapitated, and both eyes were removed. All procedures conformed to NIH and University of Michigan guidelines for the use and care of animals in research. The eye cup (retina, pigment epithelium, choroid, and sclera) was mounted flat in a chamber on a microscope stage and superfused (~6 ml min−1) with oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) Ames medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 33°C. The retina and electrode were visualized using a cooled CCD camera (Retiga 1300, Qcapture software; Qimaging Corporation, Burnaby, British Columbia). Large cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer (diameter: 20–25 μm) were targeted for recording. A glass electrode (tip resistance, 3–6 MΩ) was filled with Ames medium for loose-patch extracellular recordings. Once the cell type was confirmed by responses to visual stimulation, the pipette was withdrawn and a second pipette was used for whole-cell recording. The intracellular recording solution contained (in mM): K-methanesulfonate, 120; HEPES, 10; NaCl, 5; EGTA, 0.1; ATP-Mg2+, 2; GTP-Na+, 0.3; Lucifer Yellow, 0.10%; titrated to pH = 7.3. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) except Mibefradil and ZD7822 (Tocris; Ellisville, MO).

Vm was recorded at 20 kHz and stored on a computer using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier and pClamp 9 software (Axon Instruments; Foster City, CA). Junction potential (−9 mV) was corrected. We wrote programs in Matlab (The Mathworks; Natick, MA) to generate current injection protocols and to analyze responses. Results are from 177 OFF Alpha cells (Vrest, −65.1 ± 2.1 mV, n=69). During current clamp recordings, the bridge (10–20 MΩ) was checked continuously (every 1–5 min.) and balanced. The recording was terminated if the bridge exceeded 25 MΩ. In a few cases, drug actions and visually evoked currents were evaluated in voltage clamp (Figure 6). Series resistance (Rs) was 10–15 MΩ and compensated by 60%.

Visual Stimuli

The retina was continuously illuminated at ~2 × 103 isomerizations M-cone−1 sec−1 by either a monochrome 1-inch computer monitor (Lucivid MR 1–103; Microbrightfield; Colchester, VT), a RGB OLED Display (SVGA+ Rev. 2, eMagin, Bellevue, WA ) or the green channel of an RGB LED (NSTM515AS, Nichia America Co., Wixom, MI). LED intensity was controlled by pClamp 9 software via a custom non-inverting voltage-to-current converter using operational amplifiers (TCA0372, ON Semiconductor, Phoenix, AZ). For all stimulation devices, the Gamma curve was corrected in software. Responses were measured to spots, annuli and gratings to confirm the OFF-center and nonlinear properties of OFF Alpha cells (Demb et al., 2001; Hochstein and Shapley, 1976).

In one experiment, we combined current injection with visual stimulation using the LED stimulator. In this case, the timing of the contrast stimulus was adjusted so that spiking would occur ~25 msec following the offset of a current step. Preliminary experiments using loose-patch recordings (n = 5 cells) suggested that such timing could be achieved if a 100% contrast stimulus was displayed 70 msec prior to the desired onset time. For lower contrast stimuli, where there is a longer delay to the first spike, stimulus onset was advanced by 55 msec/(−log10(contrast)), so the first spike was evoked at roughly the same time at each contrast level.

Dynamic current injection

In some current clamp recordings we dynamically compensated visually-evoked hyperpolarization with current injection. We employed a small circuit using a dual operational amplifier TCA0372 (ON Semiconductor) and an Attiny85 microcontroller (Atmel Corp., San Jose, CA). In order to prevent unintended compensation of spike AHPs, the time constant of current injection was voltage and time dependent: small hyperpolarizations from rest were compensated slowly. Dynamic current injection, I(t), was calculated from a simplified Hodgkin-Huxley equation:

| (1) |

where Imax is the maximum possible current injection of the setup (2 nA) and n2 is the voltage-dependent proportion of that current. Changes in n over time were computed as follows:

| (2) |

where n∞(Vm) is the steady-state activation:

| (3) |

V1/2 is the voltage that generates a half-maximal value of steady-state activation, and was set in each case by measuring Vrest at the beginning of each experiment and subtracting 7 mV; this value ensured that voltage was clamped at ~−2 mV below rest. The time constant in equation 2, τ(Vm), is defined as:

| (4) |

where τmin = 52 μs (the sample rate) and τmax = 4 ms; this latter value was determined empirically to cancel synaptic current but not affect the spike AHP.

Vm was measured with 0.15 mV resolution (i.e., 10-bit resolution, range = −100 to +50 mV) at 19.3 kHz from the output of the Multiclamp 700B amplifier. Calculations used look-up tables for the voltage dependence of τ(Vm) and n∞(Vm) and were completed in 40μs. I(t) was then updated with 8-pA resolution, low-pass filtered at 10 kHz and injected into the cell via the Multiclamp 700B amplifier. Improper bridge balance (e.g., >20 MΩ or changed by >~2 MΩ) caused strong oscillations, that in some cases even triggered spikes. Only recordings without such oscillations were analyzed.

Somatic patch recordings

Outside-out patches were pulled from identified OFF Alpha ganglion cells in order to study voltage-gated currents. After establishing a seal of >5 GΩ on the soma and correcting for the pipette capacitance, the cell membrane was disrupted to establish a whole-cell configuration, with Vhold = −60 mV. The pipette was slowly removed from the cell using the manipulator’s piezo-drives, while constantly checking Rs, Rin and capacitance. After reaching >100 MΩ of Rs (from originally 10–20 MΩ) the pipette was quickly removed manually several hundred μm. Initial membrane capacitance and Rin were recorded from the membrane patch. Cases where Vm was positive to −30 mV or when the ratio of Rin to Rs was <10 were not studied further. Voltage-clamp recordings were performed without Rs compensation at 10 kHz with a 4 kHz Bessel-filter. Capacitance artifacts and leak currents were measured during the voltage-clamp recordings using 5 mV steps from Vholds and used to record changes in membrane parameters. Recordings with roughly constant leak current were used for analysis. Capacitance artifacts were fitted with a double exponential function and together with the leak current subtracted from the current traces. Due to imperfect fits of the first two recorded points in the capacitance artifact, the first 0.2 ms after a voltage step were omitted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mania Kupershtok for technical assistance and Dr. Josh Singer for comments on the manuscript. Supported by a Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award, an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship and the NIH (EY14454; EY14454-S1; Core Grant EY07003).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baccus SA, Meister M. Fast and slow contrast adaptation in retinal circuitry. Neuron. 2002;36:909–919. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranauskas G. Ionic channel function in action potential generation: current perspective. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;35:129–150. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-8001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin DL, Borghuis BG, Demb JB. Cellular basis for contrast gain control over the receptive field center of mammalian retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2636–2645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4610-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin DL, Manookin MB, Demb JB. Distinct expressions of contrast gain control in parallel synaptic pathways converging on a retinal ganglion cell. J Physiol. 2008;586:5487–5502. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benardete EA, Kaplan E, Knight BW. Contrast gain control in the primate retina: P cells are not X-like, some M cells are. Vis Neurosci. 1992;8:483–486. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800004995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MJ, Warland DK, Meister M. The structure and precision of retinal spike trains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5411–5416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin JA, Palmer LA, Contreras D. Cellular mechanisms underlying stimulus-dependent gain modulation in primary visual cortex neurons in vivo. Neuron. 2008;59:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance FS, Abbott LF, Reyes AD. Gain modulation from background synaptic input. Neuron. 2002;35:773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander D, Chichilnisky EJ. Adaptation to temporal contrast in primate and salamander retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9904–9916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09904.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouabe C, Drici MD, Romey G, Barhanin J, Lazdunski M. HERG and KvLQT1/IsK, the cardiac K+ channels involved in long QT syndromes, are targets for Ca channel blockers. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert CM, Magee JC, Hoffman DA, Johnston D. Slow recovery from inactivation of Na+ channels underlies the activity-dependent attenuation of dendritic action potentials in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6512–6521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06512.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demb JB. Functional circuitry of visual adaptation in the retina. J Physiol. 2008;586:4377–4384. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demb JB, Zaghloul K, Haarsma L, Sterling P. Bipolar cells contribute to nonlinear spatial summation in the brisk-transient (Y) ganglion cell in mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7447–7454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07447.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller P, Berjukov S, Wanner S, Huber I, Hering S, Knaus HG, Toth G, Kimball SD, Striessnig J. High affinity interaction of mibefradil with voltage-gated Ca and Na channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:669–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas P, Diochot S, Celerier ML, Nakajima T, Lazdunski M. Novel tarantula toxins for subtypes of voltage-dependent K channels in the Kv2 and Kv4 subfamilies. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:48–57. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami H, Bradley RM. Biophysical and morphological properties of parasympathetic neurons controlling the parotid and von Ebner salivary glands in rats. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:678–686. doi: 10.1152/jn.00277.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, DiFrancesco D. Action of the hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) blocker ZD 7288 in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Pflugers Arch. 1997;435:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s004240050488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudry KS, Reinagel P. Benefits of contrast normalization demonstrated in neurons and model cells. J Neurosci. 2007a;27:8071–8079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1093-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudry KS, Reinagel P. Contrast adaptation in a nonadapting LGN model. J Neurophysiol. 2007b;98:1287–1296. doi: 10.1152/jn.00618.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollisch T, Meister M. Eye smarter than scientists believed: neural computations in circuits of the retina. Neuron. 2010;65:150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D, Lee JC, Higgs MH, Spain WJ, Foehring RC. Functional roles of Kv1 channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1931–1940. doi: 10.1152/jn.00933.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AL. Twenty years of dendrotoxins. Toxicon. 2001;39:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstein S, Shapley RM. Linear and nonlinear spatial subunits in Y cat retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1976;262:265–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtje M, Brunk I, Grosse J, Beyer E, Veh RW, Bergmann M, Grosse G, Ahnert-Hilger G. Differential distribution of voltage-gated K channels Kv 1.1–Kv1.6 in the rat retina during development. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:19–33. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida AT. Ion channel mutations in retinal neurons. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2000;75:69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M, Kaneko A. Voltage-gated Na currents in isolated retinal ganglion cells of the cat: relation between the inactivation kinetics and the cell type. Neurosci Res. 1991;11:261–275. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Rieke F. Temporal contrast adaptation in the input and output signals of salamander retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21:287–299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Rieke F. Slow Na+ inactivation and variance adaptation in salamander retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1506–1516. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01506.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Ishida AT. Ih without Kir in adult rat retinal ganglion cells. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:3790–3799. doi: 10.1152/jn.01241.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesica NA, Jin J, Weng C, Yeh CI, Butts DA, Stanley GB, Alonso JM. Adaptation to stimulus contrast and correlations during natural visual stimulation. Neuron. 2007;55:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Freed MA. The ON pathway rectifies the OFF pathway of the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5533–5543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4733-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon S, Delord B, Deniau JM, Charpier S. Intrinsic properties of rat striatal output neurones and time-dependent facilitation of cortical inputs in vivo. J Physiol. 2000;527(Pt 2):345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manookin MB, Beaudoin DL, Ernst ZR, Flagel LJ, Demb JB. Disinhibition combines with excitation to extend the operating range of the OFF visual pathway in daylight. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4136–4150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4274-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manookin MB, Demb JB. Presynaptic mechanism for slow contrast adaptation in mammalian retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2006;50:453–464. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mante V, Bonin V, Carandini M. Functional mechanisms shaping lateral geniculate responses to artificial and natural stimuli. Neuron. 2008;58:625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao BQ, Macleish PR, Victor JD. The intrinsic dynamics of retinal bipolar cells isolated from tiger salamander. Vis Neurosci. 1998;15:425–438. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898153051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao BQ, Macleish PR, Victor JD. Relation between K-channel kinetics and the intrinsic dynamics in isolated retinal bipolar cells. J Comp Neurosci. 2002;12:147–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1016563028021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis DJ, Detwiler PB. Different mechanisms generate maintained activity in ON and OFF retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5994–6005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0130-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Sugiyama K. A modulatory action of divalent cations on transient outward current in cultured rat sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1988;396:417–433. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GJ, Rieke F. Network variability limits stimulus-evoked spike timing precision in retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2006;52:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch TA, da Silveira RA, Siegert S, Viney TJ, Awatramani GB, Roska B. Approach sensitivity in the retina processed by a multifunctional neural circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1308–1316. doi: 10.1038/nn.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum ES, Xu ZC, Wilson CJ. Contribution of a slowly inactivating K current to the transition to firing of neostriatal spiny projection neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1174–1189. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nistri A, Cherubini E. Inactivation characteristics of a sustained, Ca(2+)-independent K+ current of rat hippocampal neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1992;457:575–590. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien BJ, Isayama T, Richardson R, Berson DM. Intrinsic physiological properties of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol. 2002;538:787–802. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perchenet L, Clement-Chomienne O. Characterization of mibefradil block of the human heart delayed rectifier hKv1.5. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:771–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto LH, Klumpp DJ. Localization of K channels in the retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17:207–230. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(97)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer H, Lanigan MD, Pennington MW, Aiyar J, Ghanshani S, Cahalan MD, Norton RS, Chandy KG. Structure-guided transformation of charybdotoxin yields an analog that selectively targets Ca(2+)-activated over voltage-gated K(+) channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1201–1208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke F. Temporal contrast adaptation in salamander bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9445–9454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09445.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke F, Rudd ME. The challenges natural images pose for visual adaptation. Neuron. 2009;64:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott VE, Muniz ZM, Sewing S, Lichtinghagen R, Parcej DN, Pongs O, Dolly JO. Antibodies specific for distinct Kv subunits unveil a heterooligomeric basis for subtypes of alpha-dendrotoxin-sensitive K+ channels in bovine brain. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1617–1623. doi: 10.1021/bi00173a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapley RM, Victor JD. The effect of contrast on the transfer properties of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1978;285:275–298. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivyer B, Taylor WR, Vaney DI. Uniformity detector retinal ganglion cells fire complex spikes and receive only light-evoked inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:5628–5633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909621107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain WJ, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Post-inhibitory excitation and inhibition in layer V pyramidal neurones from cat sensorimotor cortex. J Physiol. 1991;434:609–626. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm JF. Functional diversity of K+ currents in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Seminars in Neuroscience. 1993;5:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk M, Wassle H, Taylor WR. Receptive field properties of ON- and OFF-ganglion cells in the mouse retina. Vis Neurosci. 2009;26:297–308. doi: 10.1017/S0952523809990137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor JD. The dynamics of the cat retinal X cell centre. J Physiol. 1987;386:219–246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werblin FS. Six different roles for crossover inhibition in the retina: Correcting the nonlinearities of synaptic tranmission. Vis Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1017/S0952523810000076. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HY, Zheng H, Nam JH, Nguyen YH, Kang TM, Earm YE, Kim SJ. Facilitation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels (IKCa1) by mibefradil in B lymphocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:549–560. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaghloul KA, Boahen K, Demb JB. Contrast adaptation in subthreshold and spiking responses of mammalian Y-type retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:860–868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2782-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]