Abstract

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by diffuse mucosal inflammation limited to the colon and rectum. Although a complete medical cure may not be possible, UC can be treated with medications that induce and maintain remission. The medical management of this disease continues to evolve with a goal to avoid colectomy and ultimately alter the natural history of UC. Emergence of antitumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) agents has expanded the medical armamentarium. 5-Aminosalicylates continue to be used in mild to moderate UC and corticosteroids are mainly used for induction of remission with immunomodulators (6-mercaptopurine/azathiopurine/methotrexate) being applied as steroid-sparing agents for maintenance therapy. Infliximab has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and used in the treatment of moderate to severe UC; nevertheless, its use may be associated with significant adverse effects and have a negative impact on the postoperative course should the patients undergo restorative proctocolectomy. In addition, there is always a concern about patients' compliance to medical therapy, cost of medications, and risk for UC-associated dysplasia. The authors discuss the pros and cons of medications used in the treatment of UC.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, medical treatment, risks and benefits

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by diffuse mucosal inflammation limited to the colon. It usually involves the rectum at presentation and may extend proximally in a symmetrical, circumferential, and continuous pattern to involve parts or all of the large intestine. The disease course of UC is characterized by exacerbations and remissions, which may occur spontaneously or in response to treatment changes, superimposed infection, intercurrent stress, or illness.1 UC affects ∼500,000 individuals in the United States with an incidence of ∼12 per 100,000 per year.2,3,4,5,6 UC poses a considerable health burden in terms of cost. The disease accounts for over a quarter million physician visits annually with 30,000 hospitalizations. It is also associated with the loss of over a million workdays per year.7 The US direct health care costs are astoundingly high, exceeding 4 billion dollars annually, which includes estimated hospital costs of over $960 million and drug costs of $680 million.8,9 The general principle in treating UC patients is improvement of quality of life (QOL), induction and maintenance of remission, mucosal healing, the avoidance of colectomy, and decreasing the likelihood of the development of cancer.

The lifetime risk of a severe exacerbation of UC requiring hospitalization is ∼15%.10 Patients with extensive disease (macroscopic disease proximal to the splenic flexure) are more likely to develop acute severe colitis. Approximately 4 to 9% of UC patients will require colectomy within the first year of diagnosis;11,12 the risk of colectomy following that is 1% per year.13 The vast majority of UC patients will require medical therapy throughout their lifetime. Therefore, an understanding of the appropriate use of these agents and their risks and benefits is important for the physician caring for these patients. In recent years, the medical management of UC has changed significantly. In particular, the advent and approval of antitumor necrosis factor-α (TNF- α) agents like infliximab in the management of moderate to severe UC has expanded the role of medical therapy in UC.

Several agents have been shown to have clinical benefit for induction and maintenance therapy of UC. However, the challenge lies with the management of severe UC that does not respond to medical management. A recent study showed that there was a 7% absolute reduction in the risk of colectomy in the infliximab versus placebo group (10% vs 17%, respectively) over a 54-week follow-up period.14 Whether the use of infliximab decreased the risk of colectomy in the long run is not known. With life-long treatment, there are always concerns about patients' compliance with medical therapy, the cost and side effects of medications, and dysplasia risk. Here we discuss the various medications used in the treatment of UC and the pros and cons of medical treatment.

REVIEW CRITERIA

In May 2010, we searched MEDLINE from 1980 to the present using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms ulcerative colitis, aminosalicylates, azathioprine, corticosteroids, mercaptopurine, infliximab, medical management, colectomy, restorative proctocolectomy, and the keyword phrase “medical management of ulcerative colitis.” Full articles and abstracts without language restrictions were considered. Important developments in research and reports from centers of excellence form the basis of this review article. Treatment of UC involves sequential therapy to treat acute disease followed by therapy to maintain remission. We will discuss various medications used in the management of UC and discuss the risks and benefits of various approaches.

MEDICATIONS

5-Aminosalicylates

Sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) remain the first-line therapy for the induction of remission in patients with mild to moderate active UC.15,16 Oral 5-ASAs come in a wide range of formulations with different release characteristics, which have been reviewed recently.17,18 Sulfasalazine, 5-ASA bound to sulfapyridine by an azo bond, was the initial form found to be useful in the treatment of UC.19,20 Because the 5-ASA component is the therapeutically active compound, several oral preparations of 5-ASA were subsequently developed. However, sulfasalazine appears to have comparable efficacy against alternative formulations in a recent meta-analysis.21 The type and dosage of 5-ASA therapy are determined by location, severity of disease, cost and insurance coverage, and patients' preference. Most ASA agents have comparable pharmacokinetics in terms of systemic absorption, urinary excretion, and fecal excretion of active ingredient. Meta-analyses showed that topical 5-ASA delivered rectally appeared to be superior to placebo and topical corticosteroids for the induction of remission in distal UC.22,23,24 However, concomitant topical application of 5-ASA and corticosteroid was shown to be superior to topical 5-ASA alone. Topical 5-ASA appears to be at least as effective as oral 5-ASA in maintenance of remission for distal UC. 5-ASA appears to be more effective than placebo across all dose ranges with a trend toward a dose–response effect. Patients with active proctitis or distal colitis disease can be treated either with topical (enemas or suppositories) or oral 5-ASA, or a combination of both. However, controlled trials have shown that rectal therapies have a more rapid effect than oral treatment. Combination therapy with oral and topical 5-ASAs may achieve a higher remission rate than either rectal 5-ASA or oral 5-ASA alone in distal UC. In one study, patients treated with both topical and oral 5-ASAs had an 89% remission rate, compared with 69% for topical 5-ASA alone and 46% for oral 5-ASA alone.25 In patients with left-sided disease or extensive mild-to-moderate active UC, oral 5-ASAs may be used along with topical 5-ASAs.

The various oral 5-ASA preparations are equally effective in producing a response in 40 to 75% of patients after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment.26 In patients with active UC, delayed-release oral mesalamine (Asacol HD®, Proctor and Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Cincinnati, OH) in doses of 2.4 g/day demonstrated comparable efficacy (51 vs 56%) versus 4.8 g/day. However, a dose of 4.8 g/day was more effective in moderate disease (57 vs 72%).27 Recently, a new formulation of ASA utilizing a multimatrix (MMX) release system (Lialda®, Shire US, Wayne, PA) has been studied, which in addition to being pH dependent (breaks down at pH ≥7, normally in the terminal ileum) also slowly releases 5-ASA throughout the entire colon. The clinical remission rates were 37.2% and 35.1% in the 2.4 and 4.8 g/day groups after 8 weeks of treatment, respectively, compared with 17.5% in the placebo group in active mild-to-moderate UC.28,29,30 These once-daily doses provide the opportunity to improve adherence rates, which is a major issue in patients with UC. Of note, combination therapy with oral and rectal mesalamine may be superior to oral or rectal therapy alone in patients with extensive colitis.31 With regard to maintenance, oral mesalamine has been shown to decrease relapse rates to 23 to 37% at 12 months compared with 50 to 65% in placebo patients.15,26 A subsequent trial evaluated the efficacy of maintenance therapy of MMX over a 12-month period at 1.2 g twice a day versus 2.4 g/day. The remission rates were similar; 64.4% with 1.2 g and 68.5% with 2.4 g/day.32 Another oral mesalamine formulation has been developed with the trade name Apriso® (Salofalk Granu-Stix; Salix Pharmaceuticals, Morrisville, NC). Apriso® has mesalamine granules that have a gastric acid-resistant enteric coating (which dissolves at pH >6) that delays release and has a retarding polymer matrix in the granule core that extends release throughout the colon similar to Lialda®. A clinical trial showed that Apriso® can be administered once daily and was shown to be as effective and safe at a three times a day schedule in mild to moderate UC.33,34,35 Finally, although no randomized trials are available, several observational studies and a meta-analysis have shown a potential protective effect of 5-ASA therapy at doses >1.2 g/day against the development of colorectal cancer and dysplasia.36,37 The reduction of colectomy risk has not been studied in patients on ASA treatment.

Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids can be used for both left-sided colitis and extensive colitis. In patients with proctitis or left-sided disease, topical corticosteroids in the form of foams and enemas are used. In a meta-analysis in patients with active distal UC, although rectal application of hydrocortisone or budesonide was superior to placebo, topical hydrocortisone appears to be less effective than topical 5-ASAs in inducing remission. Topical hydrocortisone may be considered as an alterative agent in patients who fail in topical 5-ASA therapy.38,39

In patients with extensive pancolitis and a more severe clinical presentation, or in patients who fail to respond to oral and topical 5-ASA therapy, oral corticosteroids like prednisone may be used for induction therapy. However, parenteral corticosteroids are often required in patients with severe colitis.40 Response is seen within 10 to 14 days, but should then be tapered as corticosteroids are not used for maintenance due to their lack of efficacy and adverse effects.41 One of the common mistakes in managing UC is the use of corticosteroids for long-term maintenance. On the other hand, the requirement of oral or parenteral use of corticosteroids is a reliable prognostic factor. In UC patients requiring corticosteroid use, approximately one-third of patients underwent colectomy within 12 months.42

To minimize the systemic toxicity, topically active steroid formulations have been tried in UC. Budesonide is an oral glucocorticoid with high first-pass metabolism, and thus has limited systemic toxicity. In a study evaluating oral budesonide in patients with extensive and left-sided mild-to-moderate UC, comparable efficacy to prednisolone in inducing remission was observed. However, endoscopic and histologic scores were superior in the prednisolone group.43 Therefore, oral budesonide has not been routinely used in treating UC.

Azathioprine and 6-Mercaptopurine

6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) and its prodrug azathioprine (AZA) are antimetabolite drugs, inhibiting purine synthesis. Therapeutically effective doses of AZA and 6-MP are 2.0 to 3.0 mg/kg/day and 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg/day, respectively; their effect may take up to 17 weeks.44 The dosage of 6-MP and AZA may be directed by measuring thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) activity. Low to intermediate levels of TPMT are associated with the risk of leucopenia.45 Thus patients with normal TPMT activity may receive standard doses of AZA or 6-MP. Patients with intermediate activity can receive 50% of the standard dose. Patients who have no TPMT activity should not be treated with the agents.46

The main application of 6-MP/AZA in the UC is to maintain remission of the disease. Patients with UC in remission on AZA ≥6 months relapsed at a higher rate over one year when converted to placebo (59%) as compared with those who continued AZA (36%).47 6-MP/AZA typically works in UC patients whose disease activity responds to corticosteroid therapy. 6-MP/AZA has a steroid sparing effect.48,49,50,51 There appears to be fewer colectomies in those patients maintained on AZA.50,51 A prospective study evaluating the efficacy of AZA in maintaining remission in patients with acute severe colitis after successful therapy with corticosteroids found a decreased rate of relapse (10% vs 55%) and severe relapse (0% vs 36%) when compared with a historical cohort that did not receive AZA after steroid-induced remission.52 Controlled trials have also demonstrated a benefit of AZA plus sulfasalazine versus sulfasalazine alone in patients with newly diagnosed UC,53 and a similar ability to maintain remission with less toxicity in AZA alone compared with AZA plus olsalazine in patients with steroid dependent UC.54 In a meta-analysis of 6-MP/AZA compared with either placebo or 5-ASAs, the mean efficacy (pooled data) was 60% (95% CI 51–69%) in the 6-MP/AZA group and 37% (95% CI 28–47%) in the control groups. When only compared with placebo, 6-MP/AZA was found to be beneficial in maintaining remission with odds ratio (OR) of 2.59 (95% CI 1.26–5.3), absolute risk reduction of 23%, number needed to treat (NNT) of 5.55 This meta-analysis suggests the efficacy of thiopurines in the maintenance of remission. Accordingly, the American Gastroenterology Association's guidelines recommended that patients with steroid-dependent UC should be treated with 6-MP/AZA, based on the grade A evidence (homogeneous randomized controlled trials or well-designed cohort studies).56

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine (CSA), an immunosuppressant that inhibits T lymphocyte function has been used in severe corticosteroid-resistant UC.57 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 20 patients who had failed intravenous (IV) corticosteroid therapy, 82% responded to CSA, 0% responded to placebo; of the 9 placebo patients who did not respond initially, 55% did well when crossed over to open-label CSA. However, 3 of 11 patients in the cyclosporine group versus 4 of the 9 patients in the placebo group required colectomy within 1 month.57 Following that, four additional controlled trials of CSA in patients with severe UC were conducted. The studies produced a response rate of 80%.58,59,60,61 In a study of 30 patients who were randomized to either CSA or methylprednisone, 64% of patients who received CSA and 53% who received steroids achieved clinical remission within 8 days. At 1 year, 78% of the CSA group was in remission as opposed to 37% in the corticosteroid group. After one year, 7 of the 9 responders in the cyclosporine group were still in remission compared with 4 of the 8 in the corticosteroid group (p > 0.05), and colectomy rates were similar.58,62

The long-term response rates in patients treated with CSA has been evaluated. In a study of 42 patients with severe steroid-refractory UC treated with IV CSA followed over a 5-year period, 45% avoided colectomy, with higher rates in those who initially responded to CSA and in those concomitantly on AZA or 6-MP (49% vs 17%).63 A study comparing QOL in patients who underwent colectomy versus management with CSA found that individuals given cyclosporine scored as well or better than their surgical counterparts.64 In a retrospective single-center study of 86 patients treated with CSA, 25% of initial responders required colectomy at a mean interval of 178 days, and life-table analysis showed that of all patients treated with CSA, 55% would avoid colectomy at 3 years.65 The dose used in many of the studies is 4 mg/kg per 24 hour with a goal trough level of 300 to 400 ng/mL; although some studies have suggested that lower doses of CSA may be as effective.61,66

Anti-TNF Agents

TNF inhibitors have been recently approved for the management of moderate to severe UC. Infliximab (IFX), a chimeric monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 antibody toward TNF-α), was the first drug of the category approved for the treatment of UC. IFX has been studied in several small open-labeled trials in steroid-refractory and steroid-dependent UC.67,68,69,70,71 Subsequently, a double-blind, placebo controlled study of IFX was terminated prematurely due to slow enrollment, but showed a 50% response rate at 2 weeks in patients previously refractory to IV corticosteroids.72 Two additional placebo-controlled studies of steroid-refractory disease73,74 found favorable results, which led to large subsequent studies. The Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 1 and 2 (ACT 1 and 2), which enrolled patients with moderate-to-severe active UC treated with corticosteroids and/or 6-MP/AZA (ACT 1) or with UC refractory to at least one standard therapy (ACT 2) are the landmark studies evaluating the efficacy of IFX.75 In ACT 1, the clinical response to IFX at 8 weeks was 69% (5 mg/kg) and 61% (10 mg/kg) versus 37% in the placebo group (p < 0.001), and similar response rates were found at 8 weeks in ACT 2. In both studies, patients who received IFX were more likely to have a clinical response at week 30, and in ACT 1, more patients who received IFX had a clinical response at week 54. Endoscopic remission, which has been of interest as a treatment result, was also seen in >50% of the IFX-treated groups in ACT 1 at 30 and 54 weeks. Subsequently, a follow-up study was done to evaluate health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients treated with IFX to see whether improved clinical response translated to improved QOL. The study found substantially improved HRQoL sustained through 1 year with maintenance therapy.76 However, the influence on the risk of colectomy was not evaluated until recently. In a recently published follow-up of ACT 1 and 2 studies evaluating colectomy rates, the cumulative incidence of colectomy in patients treated with infliximab through 54 weeks was 10% compared with 17% for the patients in the placebo group.14 There was a 41% reduction in the colectomy rate in UC patients treated with IFX. However, the patients enrolled in the study who had moderate-to-severe UC and had not received IV corticosteroid within 2 weeks were judged unlikely to require colectomy within 12 weeks. Hence, the reduction in risk cannot be entirely attributed to IFX.14

Previous studies have addressed the risk of colectomy in patients with severe UC. In a small pilot study of 11 patients hospitalized with severe steroid-refractory disease, 50% of patients receiving IFX responded compared with no response in patients in the placebo group, but the numbers were too small to detect a statistically significant benefit.72 A study of 45 severe UC inpatients at risk for surgery showed a decreased rate of colectomy at 3 months in those who received one dose of IFX (29 vs 67%, p = 0.017).73 However, the risk of colectomy in the long run was evaluated in a study of 314 UC patients from Italy.77 Fifty-two (16.5%) patients had severe UC and 15 of the 52 patients (29%) did not respond to a median of 7 days of IV corticosteroids. Of these, four underwent urgent colectomy and 11 received IFX. A clinical response was observed in all IFX-treated patients. In the long-term, another 6 patients underwent elective colectomy. The overall colectomy rate, following the acute flare-up, was 19%. The long-term colectomy risk was comparable in patients treated with infliximab and in steroid-responsive patients (18% vs 11%, respectively). However, patients treated with IFX had a shorter colectomy-free disease course than the patients responding to IV corticosteroids. The authors speculated that steroid-refractory patients, who achieve remission with IFX, have a more severe disease than steroid-responsive patients.77

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS

Benefits

Medical management offers the option of avoiding surgery in the majority of patients with UC. Although colectomy is potentially curative in some patients with UC and substantially reduces the risk of colon cancer, the surgery is often associated with a variety of complications, particularly in patients who have restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA). The short-term and long-term surgical complications include anastomotic leaks, pelvic sepsis, pouchitis, Crohn disease (CD) of the pouch, cuffitis, and irritable pouch syndrome (IPS), which adversely affect the outcome and compromise patient's QOL. In addition, IPAA may also impact the patient's sex life and fertility. In addition, there is a small risk for the development of neoplasia of the anal transitional zone (ATZ).78 In a recently published study from our group, the cumulative incidence for pouch neoplasia at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 0.9%, 1.3%, 1.9%, 4.2%, and 5.1%, respectively. The cumulative incidence for pouch cancer (including SCC and pouch lymphoma) at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.8%, 2.4%, and 3.4%, respectively.78 The cumulative incidence for pouch dysplasia at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 0.8%, 1.3%, 1.5%, 2.2%, and 3.2%, respectively.78 Thus patients with IPAA still may require frequent pouch endoscopy to evaluate the IPAA for any dysplasia or cancer. Patients with IPAA may also be at risk for anemia and bone loss. However, surgery may be indicated when complications of severe disease occur such as hemorrhage, toxic megacolon, or perforation. Thus, the benefits of medical management should be discussed in non-life-threatening conditions before proceeding to surgical management.

The “loss” with surgical therapy would be the “gain” for continuous medical therapy. The step-up approach has been the standard of care in medical therapy for UC, starting with 5-ASAs, then corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and in some cases, biologics. A top-down therapy79 has aimed at altering the natural history of IBD using an aggressive treatment starting with biologics with or without concurrent immunomodulators; it has been used in treating patients with CD. However, this approach has not been studied in UC.

Problems

There have been issues of continuous medical therapy in patients with UC, particularly with agents like immunomodulators and biologics. UC is considered a life-long disease that requires long-term therapy. A step-up approach for medical therapy is routinely applied, from 5-ASA compounds, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics. There is no convincing evidence suggesting that the long-term medical therapy may alter the natural history of UC. In addition, there are always concerns about patients' compliance to medical therapy, cost and side effects of medications, and dysplasia risk. Risks and benefits need to be carefully discussed with the patients before offering specific treatment.

PROBLEMS WITH ADHERENCE TO MEDICAL THERAPY

Nonadherence has been observed in a significant proportion of patients with UC. Medication nonadherence prevalence rates vary from 35 to 72% in various studies.80,81,82,83 In a retrospective survey of IBD patients, the overall compliance rate with a maintenance dose of mesalamine was only 40%. The median dosage of medication dispensed per patient was 71% of the prescribed regimen.80 Noncompliant patients were more likely to be male, single, and have disease limited to the left colon.80 Nonadherence is more of a problem in children and adolescents, given the complex challenges unique to childhood and adolescence, including the maturation of cognitive and behavioral patterns (e.g., health beliefs) that affect self-management. Reported nonadherence rates in pediatric IBD patients ranged from 50 to 66%.84,85

Long-term use of immunomodulators that requires periodic monitoring of laboratory tests, may pose a particular challenge for patients' compliance. In a study of 159 patients with CD or UC who were treated with AZA, 13% were found noncompliant based on measurement of serum metabolite concentration.86 The noncompliant rate was even higher in patients with a combination therapy of 5-ASA and immunomodulators.87 Noncompliant patients had a higher risk for disease relapse.86,88 For example, patients who were noncompliant to mesalamine therapy had a 5-fold increased risk for relapse compared with patients who took at least 80% of their prescribed dose.88 Given the problems with nonadherence, surgery may offer an alternative.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF MEDICATIONS

Medications used in the treatment of IBD are associated with several adverse effects. Sulfasalazine consists of sulfapyridine linked to 5-ASA (mesalamine, mesalazine) via an azo bond. However, its use is limited by high rates of intolerance among patients. Side effects can include headache, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, skin rash, fever, hepatitis, hematologic abnormalities, folate deficiency, pancreatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and reduction in sperm counts.89 Sulfapyridine, a sulfonamide moiety has been suggested to be responsible for hypersensitivity reactions. Sulfasalazine-induced hepatotoxicity manifests as elevation of aminotransferases, hyperbilirubinemia, and less commonly, fever, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and granulomatous liver disease.90 Hepatotoxicity can also be a part of a hypersensitivity reaction.90

Similarly, thiopurines used in the treatment of IBD are associated with liver toxicity.90 Hepatotoxicity usually manifests by elevation in aminotransferases, accompanied by flu-like symptoms. In some patients, it can present as an isolated cholestatic enzyme elevation. Abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) usually return to normal after discontinuation of the agents.90 6-MP/AZA-induced hepatotoxicity occasionally may be idiosyncratic in nature with rare presentation with veno-occlusive disease (VOD).91 Acute pancreatitis is also reported with 6-MP/AZA use in IBD. Pancreatitis is an early idiosyncratic adverse reaction after initiation of treatment and usually occurs within 3 to 4 weeks of therapy. Pancreatitis is considered to be idiosyncratic and dose-independent.92

The use of anti-TNF agents is also associated with several adverse effects including infusion reactions, hypersensitivity reactions, tuberculosis, and lymphoma.93 Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma has been described in IBD patients treated with anti-TNF drugs including infliximab and adalimumab, particularly in combination with immunomodulators.90 Reports from the manufacturer maintained TREAT registry with a voluntary reporting system, however, suggest that serious infection from IFX-treated CD patients appeared to be associated with a concurrent use of corticosteroids or narcotic analgesics.94 The risk of postoperative complications in UC patients treated with IFX before colectomy has been studied.95,96 After adjusting for age, high-dose corticosteroids, AZA, and severity of colitis, infliximab use remained significantly associated with infectious complications, with an odds ratio of 2.7 in a multivariable analysis.95 In a study from our institution, preoperative IFX use was also found to be associated with an increased risk for three-stage restorative proctocolectomy instead of the traditional two-stage procedure and an increased risk of postoperative infectious complications.96 A multicenter study from Europe evaluated the safety of IFX in 52 patients with steroid-refractory UC who did not respond to CSA.97 Fifteen patients (29%) ended with colectomy within a median of 5 weeks. The rate of adverse events was 25% (6 infections, 3 infusional reactions, 1 leukopenia, 1 bowel perforation, 1 fever, and 1 peripheral neuropathy). One death occurred in a 40-year-old man due to pneumonia who underwent surgery 10 days after the first infliximab infusion.97 Therefore, it appears that the pushing of medical therapy to the limit may be costly in terms of severe adverse effects before and after colectomy.

UC itself appears to have no adverse effects on fertility in women98 and men.99 However, a variety of medications used in the management of IBD may affect fertility. Among the medications, sulfasalazine has been clearly associated with male infertility and abnormalities in sperm count, motility, and morphology.100 An association between sulfasalazine use in the parent and congenital malformations in the progeny has been described.101 6-MP and AZA do not appear to reduce semen quality in men with IBD.102 IFX treatment in men may decrease sperm motility and morphology.103 The safety of anti-TNF agent use during pregnancy is still controversial. All currently IBD-targeted anti-TNFα agents were shown to be able to cross the placenta to a certain degree: IFX was labeled as a Class B drug for pregnancy by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Association between the use of corticosteroids and stillbirth has been reported.104,105 In addition, the use of purine analogues by both men and women treated for IBD was reported to be associated with congenital abnormalities.106 Surgical treatments in the form of IPAA would circumvent these issues and would be beneficial in patients with IBD.

RISK OF DYSPLASIA AND COLORECTAL CANCER WITH MEDICAL THERAPY

Colon cancer is one of the common causes for mortality in UC patients. The cost of surveillance colonoscopy is high. A meta-analysis of published studies reported that the overall risk for colorectal cancer was 2% after 10 years, 8% after 20 years, and 18% after 30 years of diagnosis.107 There are no randomized controlled trials of surveillance colonoscopy in patients with UC or CD. Patients with a long history of UC on medical therapy are at risk for the development of dysplasia and cancer. Although a small risk of malignant transformation in the cuff or anal transitional zone remains in patients with total proctocolectomy and IPAA,79 the risk is much lower than an intact colon left behind.

Whether medical therapy changes the natural history of UC, particularly patient survival, is not clear. There are no randomized trials assessing the impact of surveillance on mortality from colorectal cancer in UC patients. A small study of 41 patients with colorectal cancer arising in the setting of UC showed that the 5-year survival rate was 77% in UC patients on a surveillance program, compared with a 36% 5-year survival of those on no surveillance.108 In contrast, some investigators questioned the usefulness of surveillance in UC patients.109 Retrospective and prospective studies have failed to conclusively resolve the question of efficacy of surveillance to decrease mortality. In addition, the cost of detecting cancer in UC can be expensive. It was estimated that it requires approximately $71,000110 or $200,000111 per cancer detected. Mathematical models suggest that longer intervals between surveillance colonoscopies are more cost-effective until the disease duration reaches 20 years.112

Although colectomy is considered the most effective way to reduce cancer risk, the role of medical therapy in reducing the risk of neoplasia in UC is still controversial. There are several epidemiologic studies that have identified long-term 5-ASA therapy as a factor that significantly reduces the risk for developing colorectal cancer.113,114 A meta-analysis was performed to evaluate 3 cohort and 6 case-control studies consisting of 334 cases of colorectal cancer, 140 cases of dysplasia, and 1,932 UC patients.115 Pooled analysis showed a protective association between 5-ASA use and colorectal cancer alone (OR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.37, 0.69), or a combined endpoint of colorectal cancer and dysplasia (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.38, 0.69).115 However, 5-ASA use was not associated with a lower risk of dysplasia alone.115 The chemopreventive effect of 5-ASAs needs to be further verified; it is not clear whether long-term use of 5-ASAs can affect the natural history of UC.

LIMITATIONS TO SURVEILLANCE COLONOSCOPY

After 8 to 10 years of colitis, an annual or biannual surveillance colonoscopy should be performed.116 There are potential problems with surveillance that include such factors as pathologic interpretation, physicians' knowledge and practice, and the patients' compliance. IPAA would be beneficial in patients with questionable compliance as it removes the risk of missing a screening colonoscopy or a pathological interpretation. Studies have shown that surveillance compliance can be diminished when a patient is asymptomatic and poor compliance could increase the risk for cancer. The only study to directly address the outcomes in patients documented to be noncompliant with annual surveillance was a cohort of 121 patients with UC >7 years and 7 patients developed cancer.117 Two of these 7 had not complied with a recommendation for repeat colonoscopy or colectomy after dysplasia. The patients had quiescent disease and presented years later with obstructive symptoms related to tumor.117

CONTROVERSY ON SURVEILLANCE VERSUS COLECTOMY FOR LOW-GRADE DYSPLASIA

Patients with high-grade dysplasia or flat low-grade dysplasia or multifocal low-grade dysplasia in flat mucosa should undergo colectomy.118 A dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) arising from UC is also an indication for colectomy. There has been no consensus regarding colectomy for patients with low-grade dysplasia, particularly unifocal.118 Given the controversy in the management of low-grade dysplasia, medical management would not circumvent the problem as there is no consensus on how frequently to monitor and follow patients.

TREATMENT EFFECTIVENESS: IMPROVED QUALITY OF LIFE

QOL is an important measure to assess the effect of treatment. Numerous studies have examined the effects of surgery on QOL in patients with UC.119,120,121,122 QOL is usually better in surgically than medically treated patients, particularly in patients with severe UC who have extremely poor QOL before surgery, although the degree of improvement varies depending on disease activity and severity at the time of surgery; and surgical outcome.122 IPAA surgery was designed to improve the QOL. QOL is an important measure of operative outcome with any surgery, perhaps because more conventional measures of quality such as morbidity and mortality have declined steadily. As the usual route of defecation and continence are maintained, it is reasonable to assume that IPAA offers a clear improvement in the QOL, compared with ileostomy or medically managed patients.

Some studies did not assess QOL before surgery and hence QOL improvements after surgery can be presumed to be from IPAA. Nevertheless, several investigators concluded that QOL in patients after colectomy was similar to that in the general population.119,120,121 Although a substantial improvement in QOL compared with the preoperative level is often seen in patients with UC,123,124 the results are inconsistent. Some studies reported either minimal change in general QOL when comparing pre-IPAA with post-IPAA scores,124 or QOL lower than published norms for the general population in postsurgical patients with UC.125 Even with surgical complications, 90% of patients with IPAA were satisfied with the procedure and 95% would undergo the procedure again; 71% of patients felt no restriction in general after IPAA.126

Although IPAA may not be the ultimate gold standard treatment, it is the gold standard surgical option we have at present in UC patients to substantially improve the QOL from the surgical perspective. However, the patient should be given detailed information about the different medical and surgical options and their pros and cons and the available data before proceeding with definite management.

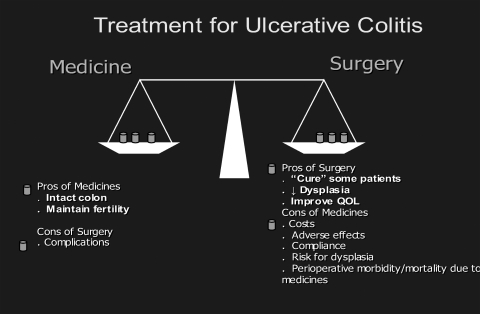

In summary, the step-up approach is the current standard of care for patients with UC. For patients with mild-to-moderate UC, optimization of medical therapy is the key. Risks and benefits of medical versus surgical therapy should be carefully balanced in patients with moderate-to-severe steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory UC. Figure 1 summarizes the pros and cons of medical management.

Figure 1.

The pros and cons of medical and surgical management of ulcerative colitis.

References

- 1.Meyers S, Janowitz H D. The “natural history” of ulcerative colitis: an analysis of the placebo response. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11(1):33–37. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus E V, Jr, Silverstein M D, Sandborn W J, Tremaine W J, Harmsen W S, Zinsmeister A R. Ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gut. 2000;46(3):336–343. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappelman M D, Rifas-Shiman S L, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(12):1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loftus C G, Loftus E V, Jr, Harmsen W S, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(3):254–261. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrinton L J, Liu L, Lewis J D, Griffin P M, Allison J. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Northern California managed care organization, 1996-2002. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(8):1998–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrinton L J, Liu L, Lafata J E, et al. Estimation of the period prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among nine health plans using computerized diagnoses and outpatient pharmacy dispensings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(4):451–461. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnenberg A, Chang J. Time trends of physician visits for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States, 1960-2006. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(2):249–252. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen G C, Tuskey A, Dassopoulos T, Harris M L, Brant S R. Rising hospitalization rates for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States between 1998 and 2004. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(12):1529–1535. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kappelman M D, Rifas-Shiman S L, Porter C Q, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1907–1913. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards F C, Truelove S C. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299–315. doi: 10.1136/gut.4.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moum B, Vatn M H, Ekbom A, et al. Southeastern Norway IBD Study Group of Gastroenterologists Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in southeastern Norway: evaluation of methods after 1 year of registration. Digestion. 1995;56(5):377–381. doi: 10.1159/000201262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Nielsen O H, Binder V. Changes in extent of ulcerative colitis: a study on the course and prognostic factors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(3):260–266. doi: 10.3109/00365529609004876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandborn W J, Rutgeerts P, Feagan B G, et al. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1250–1260. quiz 1520. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland L, Macdonald J K. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD000543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000543.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter M J, Lobo A J, Travis S P, IBD Section, British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 5):V1–V16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenstein G R, Kamm M A. Review article: 5-aminosalicylate formulations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis—methods of comparing release rates and delivery of 5-aminosalicylate to the colonic mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(6):663–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenstein G R, Kamm M A, Sandborn W J, Lyne A, Joseph R E. MMX mesalazine for the induction of remission of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: efficacy and tolerability in specific patient subpopulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(11):1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao S S, Dundas S A, Holdsworth C D, Cann P A, Palmer K R, Corbett C L. Olsalazine or sulphasalazine in first attacks of ulcerative colitis? A double blind study. Gut. 1989;30(5):675–679. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.5.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dick A P, Grayson M J, Carpenter R G, Petrie A. Controlled trial of sulphasalazine in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1964;5:437–442. doi: 10.1136/gut.5.5.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of sulfasalazine in comparison with 5-aminosalicylates in the induction of improvement and maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(6):1157–1170. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall J K, Irvine E J. Putting rectal 5-aminosalicylic acid in its place: the role in distal ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(7):1628–1636. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee F I, Jewell D P, Mani V, et al. A randomised trial comparing mesalazine and prednisolone foam enemas in patients with acute distal ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38(2):229–233. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regueiro M, Loftus E V, Jr, Steinhart A H, Cohen R D. Medical management of left-sided ulcerative colitis and ulcerative proctitis: critical evaluation of therapeutic trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(10):979–994. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000231495.92013.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safdi M, DeMicco M, Sninsky C, et al. A double-blind comparison of oral versus rectal mesalamine versus combination therapy in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(10):1867–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss A C, Peppercorn M A. The risks and the benefits of mesalazine as a treatment for ulcerative colitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6(2):99–107. doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanauer S B, Sandborn W J, Dallaire C, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablets) compared to 2.4 g/day (400 mg tablets) for the treatment of mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: The ASCEND I trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(12):827–834. doi: 10.1155/2007/862917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamm M A, Sandborn W J, Gassull M, et al. Once-daily, high-concentration MMX mesalamine in active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):66–75. quiz 432–433. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichtenstein G R, Kamm M A, Boddu P, et al. Effect of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalamine (SPD476) for the induction of remission of mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandborn W J, Kamm M A, Lichtenstein G R, Lyne A, Butler T, Joseph R E. MMX Multi Matrix System mesalazine for the induction of remission in patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a combined analysis of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(2):205–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marteau P, Probert C S, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut. 2005;54(7):960–965. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamm M A, Lichtenstein G R, Sandborn W J, et al. Randomised trial of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalazine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2008;57(7):893–902. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.138248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruis W, Kiudelis G, Rácz I, et al. International Salofalk OD Study Group Once daily versus three times daily mesalazine granules in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Gut. 2009;58(2):233–240. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.154302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruis W, Jonaitis L, Pokrotnieks J, et al. Once daily 3 g mesalamine is the optimal dose for maintaining clinical remission in ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, controlled, dose ranging study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(Suppl 1):A489. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prescribing information for Apriso (extended release mesalamine) Morrisville, NC: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

- 36.Velayos F S, Terdiman J P, Walsh J M. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(6):1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine J S, Burakoff R. Chemoprophylaxis of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: current concepts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(10):1293–1298. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James S L, Irving P M, Gearry R B, Gibson P R. Management of distal ulcerative colitis: frequently asked questions analysis. Intern Med J. 2008;38(2):114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lémann M, Galian A, Rutgeerts P, et al. Comparison of budesonide and 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas in active distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(5):557–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faubion W A, Jr, Loftus E V, Jr, Harmsen W S, Zinsmeister A R, Sandborn W J. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(2):255–260. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Truelove S C, Willoughby C P, Lee E G, Kettlewell M G. Further experience in the treatment of severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1978;2(8099):1086–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng S C, Kamm M A. Therapeutic strategies for the management of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(6):935–950. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Löfberg R, Danielsson A, Suhr O, et al. Oral budesonide versus prednisolone in patients with active extensive and left-sided ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(6):1713–1718. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson D C, May G R, Fick G H, Sutherland L R. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(2):132–142. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-2-199507150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Black A J, McLeod H L, Capell H A, et al. Thiopurine methyltransferase genotype predicts therapy-limiting severe toxicity from azathioprine. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(9):716–718. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-9-199811010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snow J L, Gibson L E. A pharmacogenetic basis for the safe and effective use of azathioprine and other thiopurine drugs in dermatologic patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(1):114–116. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawthorne A B, Logan R F, Hawkey C J, et al. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine withdrawal in ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 1992;305(6844):20–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6844.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adler D J, Korelitz B I. The therapeutic efficacy of 6-mercaptopurine in refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(6):717–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.George J, Present D H, Pou R, Bodian C, Rubin P H. The long-term outcome of ulcerative colitis treated with 6-mercaptopurine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(9):1711–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ardizzone S, Molteni P, Imbesi V, Bollani S, Bianchi Porro G, Molteni F. Azathioprine in steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(1):330–333. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199707000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lobo A J, Foster P N, Burke D A, Johnston D, Axon A T. The role of azathioprine in the management of ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(5):374–377. doi: 10.1007/BF02156261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karoui S, Djebbi S, Belkhodja A, Boubaker J, Filali A. [Maintenance therapy by azathioprine after successful treatment by intravenous corticosteroid in acute severe colitis. An open prospective study] Tunis Med. 2008;86(4):322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timmer A, McDonald J W, Macdonald J K. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000478. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000478.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mantzaris G J, Sfakianakis M, Archavlis E, et al. A prospective randomized observer-blind 2-year trial of azathioprine monotherapy versus azathioprine and olsalazine for the maintenance of remission of steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(6):1122–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.11481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gisbert J P, Linares P M, McNicholl A G, Maté J, Gomollón F. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of azathioprine and mercaptopurine in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(2):126–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lichtenstein G R, Abreu M T, Cohen R, Tremaine W, American Gastroenterological Association American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):940–987. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lichtiger S, Present D H, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(26):1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D'Haens G, Lemmens L, Geboes K, et al. Intravenous cyclosporine versus intravenous corticosteroids as single therapy for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(6):1323–1329. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svavoni F, Bonassi U, Bagnolo F, et al. Effectiveness of cyclosporine (CsA) in the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A1096. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Assche G Van, D'Haens G, Noman M, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of 4 mg/kg versus 2 mg/kg intravenous cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(4):1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moskovitz D N, Assche G Van, Maenhout B, et al. Incidence of colectomy during long-term follow-up after cyclosporine-induced remission of severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(6):760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shibolet O, Regushevskaya E, Brezis M, Soares-Weiser K. Cyclosporine A for induction of remission in severe ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004277. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004277.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah S B, Parekh N K, Hanauer S B, et al. Intravenous cyclosporine in severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: long term follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(Suppl 1):133. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen R D, Brodsky A L, Hanauer S B. A comparison of the quality of life in patients with severe ulcerative colitis after total colectomy versus medical treatment with intravenous cyclosporin. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arts J, D'Haens G, Zeegers M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with intravenous cyclosporin in patients with severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(2):73–78. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rayner C K, McCormack G, Emmanuel A V, Kamm M A. Long-term results of low-dose intravenous cyclosporin for acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(3):303–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chey W Y. Infliximab for patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7(Suppl 1):S30–S33. doi: 10.1002/ibd.3780070507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chey W Y, Hussain A, Ryan C, Potter G D, Shah A. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2373–2381. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaser A, Mairinger T, Vogel W, Tilg H. Infliximab in severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2001;113(23-24):930–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su C, Salzberg B A, Lewis J D, et al. Efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2577–2584. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gornet J M, Couve S, Hassani Z, et al. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis: an open-label multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(2):175–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sands B E, Tremaine W J, Sandborn W J, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of severe, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7(2):83–88. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, et al. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(7):1805–1811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Probert C S, Hearing S D, Schreiber S, et al. Infliximab in moderately severe glucocorticoid resistant ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003;52(7):998–1002. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn W J, Feagan B G, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feagan B G, Reinisch W, Rutgeerts P, et al. The effects of infliximab therapy on health-related quality of life in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(4):794–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aratari A, Papi C, Clemente V, et al. Colectomy rate in acute severe ulcerative colitis in the infliximab era. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(10):821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kariv R, Remzi F H, Lian L, et al. Preoperative colorectal neoplasia increases risk for pouch neoplasia in patients with restorative proctocolectomy. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):806–812. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.D'Haens G, Baert F, Assche G van, et al. Belgian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Group. North-Holland Gut Club Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9613):660–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kane S V, Cohen R D, Aikens J E, Hanauer S B. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2929–2933. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cervený P, Bortlík M, Kubena A, Vlcek J, Lakatos P L, Lukás M. Nonadherence in inflammatory bowel disease: results of factor analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(10):1244–1249. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sewitch M J, Abrahamowicz M, Barkun A, et al. Patient nonadherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(7):1535–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bernal I, Domènech E, Garcia-Planella E, et al. Medication-taking behavior in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(12):2165–2169. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mackner L M, Crandall W V. Oral medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(11):1006–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000186409.15392.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oliva-Hemker M M, Abadom V, Cuffari C, Thompson R E. Nonadherence with thiopurine immunomodulator and mesalamine medications in children with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(2):180–184. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802b320e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wright S, Sanders D S, Lobo A J, Lennard L. Clinical significance of azathioprine active metabolite concentrations in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53(8):1123–1128. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.032896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mantzaris G J, Sfakianakis M, Archavlis E, et al. A prospective randomized observer-blind 2-year trial of azathioprine monotherapy versus azathioprine and olsalazine for the maintenance of remission of steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(6):1122–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.11481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kane S V, Aikens J E, Huo D, Hanauer S B. Medication adherence is associated with improved outcomes in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mahadevan U. Medical treatment of ulcerative colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17(1):7–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Navaneethan U, Shen B. Hepatopancreatobiliary manifestations and complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(9):1598–1619. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21219. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Farrell G C. Drug-Induced Liver Disease. 1st ed. Singapore: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.

- 92.Mardini H E. Azathioprine-induced pancreatitis in Crohn's disease: a smoking gun or guilt by association. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(2):195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shale M, Kanfer E, Panaccione R, Ghosh S. Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2008;57(12):1639–1641. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lichtenstein G R, Feagan B, Cohen R D, et al. Risk factors for serious infections in patients receiving infliximab and other Crohn's disease therapies: TREAT registry data. Gastroenterology. 2010;38(Suppl 1):475. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Selvasekar C R, Cima R R, Larson D W, et al. Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(5):956–962. discussion 962–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mor I J, Vogel J D, da Luz Moreira A, Shen B, Hammel J, Remzi F H. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(8):1202–1207. discussion 1207–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chaparro M, Burgueno P, Flores E, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab rescue therapy after cyclosporine failure in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2010;38(Suppl):688. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Järnerot G. Fertility, sterility, and pregnancy in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17(1):1–4. doi: 10.3109/00365528209181034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Narendranathan M, Sandler R S, Suchindran C M, Savitz D A. Male infertility in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11(4):403–406. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198908000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Toovey S, Hudson E, Hendry W F, Levi A J. Sulphasalazine and male infertility: reversibility and possible mechanism. Gut. 1981;22(6):445–451. doi: 10.1136/gut.22.6.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moody G A, Probert C, Jayanthi V, Mayberry J F. The effects of chronic ill health and treatment with sulphasalazine on fertility amongst men and women with inflammatory bowel disease in Leicestershire. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12(4):220–224. doi: 10.1007/s003840050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dejaco C MC, Mittermaier C, Reinisch W, et al. Azathioprine treatment and male fertility in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(5):1048–1053. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mahadevan U, Terdiman J P, Aron J, Jacobsohn S, Turek P. Infliximab and semen quality in men with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(4):395–399. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000164023.10848.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dominitz J A, Young J C, Boyko E J. Outcomes of infants born to mothers with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(3):641–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nørgård B, Fonager K, Pedersen L, Jacobsen B A, Sørensen H T. Birth outcome in women exposed to 5-aminosalicylic acid during pregnancy: a Danish cohort study. Gut. 2003;52(2):243–247. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nørgård B, Pedersen L, Fonager K, Rasmussen S N, Sørensen H T. Azathioprine, mercaptopurine and birth outcome: a population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(6):827–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Eaden J A, Abrams K R, Mayberry J F. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48(4):526–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Choi P M, Nugent F W, Schoetz D J, Jr, Silverman M L, Haggitt R C. Colonoscopic surveillance reduces mortality from colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(2):418–424. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90715-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lynch D A, Lobo A J, Sobala G M, Dixon M F, Axon A T. Failure of colonoscopic surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1993;34(8):1075–1080. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sonnenberg A, El-Serag H B. Economic aspects of endoscopic screening for intestinal precancerous conditions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(1):165–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Collins R H, Jr, Feldman M, Fordtran J S. Colon cancer, dysplasia, and surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis. A critical review. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(26):1654–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706253162609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Provenzale D, Onken J. Surveillance issues in inflammatory bowel disease: ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32(2):99–105. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pinczowski D, Ekbom A, Baron J, Yuen J, Adami H O. Risk factors for colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(1):117–120. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Eaden J, Abrams K, Ekbom A, Jackson E, Mayberry J. Colorectal cancer prevention in ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(2):145–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Velayos F S, Terdiman J P, Walsh J M. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(6):1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kornbluth A, Sachar D B, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):501–523, quiz 524. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Woolrich A J, DaSilva M D, Korelitz B I. Surveillance in the routine management of ulcerative colitis: the predictive value of low-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(2):431–438. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90831-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Gastrointestinal Consortium Panel Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele R J. Objective assessment of quality of life following panproctocolectomy and ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(5):321–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Carmon E, Keidar A, Ravid A, Goldman G, Rabau M. The correlation between quality of life and functional outcome in ulcerative colitis patients after proctocolectomy ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(3):228–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fazio V W, O'Riordain M G, Lavery I C, et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230(4):575–584. discussion 584–586. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thirlby R C, Sobrino M A, Randall J B. The long-term benefit of surgery on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Surg. 2001;136(5):521–527. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.5.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Berndtsson I, Oresland T. Quality of life before and after proctocolectomy and IPAA in patients with ulcerative proctocolitis—a prospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(2):173–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martin A, Dinca M, Leone L, et al. Quality of life after proctocolectomy and ileo-anal anastomosis for severe ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(2):166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Parks A G, Nicholls R J. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 1978;2(6130):85–88. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6130.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McLeod R S, Baxter N N. Quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease after surgery. World J Surg. 1998;22(4):375–381. doi: 10.1007/s002689900400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]