Abstract

Glycolytic isozymes that are restricted to the male germline are potential targets for the development of reversible, non-hormonal male contraceptives. GAPDHS, the sperm-specific isoform of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, is an essential enzyme for glycolysis making it an attractive target for rational drug design. Toward this goal, we have optimized and validated a high-throughput spectrophotometric assay for GAPDHS in 384-well format. The assay was stable over time and tolerant to DMSO. Whole plate validation experiments yielded Z’ values >0.8 indicating a robust assay for HTS. Two compounds were identified and confirmed from a test screen of the Prestwick collection. This assay was used to screen a diverse chemical library and identified fourteen small molecules that modulated the activity of recombinant purified GAPDHS with confirmed IC50 values ranging from 1.8 to 42 µM. These compounds may provide useful scaffolds as molecular tools to probe the role of GAPDHS in sperm motility and long term to develop potent and selective GAPDHS inhibitors leading to novel contraceptive agents.

Keywords: Glycolysis, GAPDHS, high throughput screening, sperm, contraceptive.

INTRODUCTION

Sperm-selective targets are being investigated to develop novel, reversible small molecule contraceptives. These include distinct isozymes in the glycolytic pathway [1-5], such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase S (GAPDHS) [6, 7]. GAPDHS is ~70% identical to its somatic GAPDH isozyme, with amino acid differences distributed along the length of the protein [5, 8, 9]. The most distinctive structural feature of the sperm isozyme is a proline-rich N-terminal region that has no homology to somatic GAPDH enzymes from widely divergent species. Expression of GAPDHS is restricted to the male germline, offering the potential for contraception by selective inhibition of sperm metabolism without blocking glycolysis in other tissues. Gene targeting studies determined that mice lacking GAPDHS are infertile and produce sperm with very low ATP levels and no progressive motility [10]. These studies demonstrate the importance of glycolysis for sperm energy production and also provide evidence that inhibition of GAPDHS should not impair testicular function, since sperm production is unaffected in mice lacking this enzyme [10].

Early studies identified α-chlorohydrin and related derivatives as potential male contraceptives with reversible effects on fertility at low doses (reviewed in [11, 12]). Numerous reports detailed the inhibitory effects of α-chlorohydrin on GAPDHS activity, its ability to impair sperm motility and fertility and its selectivity versus the somatic GAPDH. However, side effects were observed in vivo [11-13]. More recently, structure-based drug design approaches have been applied to GAPDHS (from rat) to identify novel leads for male contraceptive development [7]. Few differences were observed between the active sites of human somatic GAPDH and sperm-specific GAPDHS, although differences elsewhere on the protein were noted that might be targetable for selective inhibitors of GAPDHS [7].

Drug targeting of GAPDH enzymes is not restricted to contraceptive studies. Compounds to inhibit pro-apoptotic activity of human GAPDH are also being investigated [14]. GAPDH has also proven to be an attractive drug target in protozoa [15] such as trypanosomes [16] and Entamoeba [17], since many of these parasites rely solely on glycolysis for their energy supply. Structure- and catalytic mechanism-based approaches have been applied to design compounds that inhibit the glycolytic enzymes of the parasites without affecting the corresponding proteins of the human host [18-20]. For some trypanosomatid enzymes, potent and selective inhibitors have already been developed that affect only the growth of cultured trypanosomatids, and not mammalian cells [16].

Towards the goal of discovering potent inhibitors for the validation of human GAPDHS as an important and novel target for male contraceptive development, we carried out a high throughput screen (HTS) against purified recombinant human GAPDHS lacking the proline-rich region. An NAD-dependent assay for GAPDHS activity was optimized and validated for HTS. We screened 56,000 compounds selected to maximize chemical diversity. From this collection, we identified 14 hits by dose-response confirmatory testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

Reagents

Unless otherwise stated all reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) or Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) at the highest level of purity possible. Human somatic GAPDH purified from erythrocytes (catalog # G6019) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and was greater than 90% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE. DL-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) (catalog # G5251) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Costar 384-well, flat-bottom, clear plates were from Corning (Lowell, MA) (catalog # 3702). The Prestwick Chemical Library was obtained from Prestwick Chemical (Washington, DC). The compounds for high throughput screening and IC50 determinations were obtained from Asinex Corporation (Moscow, Russia).

Construction of the Recombinant Human GST-GAPDHS

Unless stated, all procedures were performed according to manufacturer’s procedures. The gene for human sperm-specific gyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHS) (Accession No. NM_014364.4) lacking the proline-rich N-terminal region, and comprising residues 69-408, was synthesized (GeneArt Inc., Burlington, CA) with optimal codon usage for bacterial expression. The GAPDHS gene was flanked by an EcoRI and a XhoI site that were used to sub-clone the gene into the prokaryotic GST fusion vector, pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). The predicted molecular weight of the GST-GAPDHS construct was calculated as 63,729.39 Da.

Expression and Purification of Hu GST-GAPDHS in E. coli

Expression of GST-GAPDHS was performed in the gapA-deficient E. coli strain DS112 [21] obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (New Haven, Connecticut) as strain CGSC#7563. For large scale expression and purification, 6L cultures of DS112/GST-GAPDHS were grown at 37oC in M9 minimal media supplemented as described [21] and containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. The cultures were grown at 37oC to an OD ~0.5, the incubation temperature was reduced to 30oC and the cell culture induced for 48 h with a final concentration of 0.2 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer (DPBS, 1 mM PMSF (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), 1 mM EDTA (Promega, Madison, WI), 1 mM DTT (US Biochemicals, Santa Clara, CA), 10 µg/ml lysozyme (Fisher BioReagents, Suwanee, GA), 0.1% Triton X-100) and lysed at 23,000 psi by passage through a M-110EH homogenizer (Microfluidics, Newton, MA). After centrifugation at 30,000g for 1 h, the resulting supernatant was added to pre-equilibrated Glutathione agarose resin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) (6 ml resin/100 ml lysate) and incubated overnight at 4oC. After washing, GST-GAPDHS was eluted with 10 mM glutathione (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Purified GST-GAPDHS protein was stored at -80oC. Recombinant GST-GAPDHS samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (4-12% Bis-Tris gels, NuPAGE MOPS SDS running buffer, Invitrogen) and gels stained with Coomassie blue. Protein concentrations were estimated by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Analytical size exclusion chromatography was carried out on a Superose 12 column (GE Healthcare) as previously described [22].

Enzymatic Assay for GAPDHS

The dehydrogenase activity of GAPDHS was measured kinetically by monitoring the accumulation of NADH at 340 nm [23] immediately following the addition of the substrate, DL-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP). One enzyme unit is defined as the amount of enzyme necessary for the formation of 1 µmol of 1,3-diphosphoglycerate min-1. GAPDH was assayed at pH 8.9, optimal for its activity [24]. For Km determination for GAP, the reaction mixture contained GAPDHS, 50 mM glycine, 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.9, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM NAD and a 14 point GAP concentration range between 0 and 10 mM GAP. Assays were performed at room temperature.

Compound Libraries and Handing

A chemical collection of 56,000 compounds was purchased from Asinex Corp. All compounds in the Asinex library adhere to Lipinski’s rule of 5, with no more than 5 hydrogen bond donors, no more than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors, a molecular weight under 500 g/mol, and a partition coefficient (LogP) less than 5 [25]. All compounds are registered in ActivityBase (IDBS Inc., Guildford UK) and can be positionally located in bar-coded 384-well plates with associated SD file data. Compound handling for HTS was essentially as previously described [26, 27]. Compounds are stored at 4oC in 384-well Greiner V-bottom polypropylene plates (catalog # 781280) (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) in 100% DMSO at 10 mM and 1 mM concentrations. For HTS, 0.5 µL of 1 mM compound in DMSO was spotted into columns 3 - 22 of dry Costar clear flat bottom 384-well assay plates (catalog #3701, Corning Corp., Corning, NY) using a Biomek® NX (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA) and P20 tips. Columns 1, 2, 23, and 24 were spotted with 0.5 µL of DMSO for use as positive and negative controls. Dry spotting of compounds into assay plates was performed as a routine method to conserve compounds [26]. For dose-response measurements, 4 µL of the 10 mM DMSO stock of selected compounds was added to 1 µL of DMSO using a Biomek® NX.

The Prestwick collection containing 1,120 FDA approved compounds was prepared as 10 mM stocks in 100% DMSO. Compounds (0.5 µL) were pre-spotted into the 384-well plates using a Biomek® NX to give a final screening concentration of 10 µM.

High Throughput Screening GAPDHS Assay

The high throughput screening (HTS) assay for GAPDHS is based on the standard spectrophotometric assay of GAPDH activity described above. For HTS, all steps were carried out at room temperature in Costar clear flat-bottom 384-well plates pre-spotted with either 0.5 µL DMSO or 0.5 µL of compound. The assay consisted of two 25 µL additions carried out using a Thermo Multidrop 384-well liquid dispenser (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Reactions with inhibitors were carried out with a 15 min preincubation of compounds with 25 µL of GAPDHS/NAD. The enzymatic reaction was then initiated by addition of 25 µL of GAP substrate. The final HTS assay (50 µL) contained 30 nM GAPDHS, 50 mM glycine, 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.9, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1% DMSO, 0.5 mM NAD and 0.5 mM GAP and a final concentration of 10 µM compound for single-point screening. For HTS, maximum signal positive controls contained only DMSO (no compound), while the minimum controls were obtained by adding all assay components except enzyme. Kinetic reads (at 30 sec intervals for 5 min) of the plates were carried out on a Spectramax Plus 384 reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Inhibition data was analyzed in ActivityBase and using Microsoft Excel. Hits were defined using a standard deviation based-hit threshold (signal mean (µ) plus 3x the standard deviation (σ) in the compound data, µ+3σ).

Estimation of Assay Quality

The Z’-factor was used to assess the quality of the assay and estimate the screening window [28]. The Z’-factor incorporates both the dynamic range of the assay and well-to-well variability. Values are obtained by running one whole 384-well plate of maximum (max) signal control and one whole 384-well plate of minimum (min) signal control. Z’-factor was calculated using the formula: Z’ = 1 - (3SDmax + 3SDmin)/(Meanmax – Meanmin)

where SD = standard deviation. Max = maximum signal. Min = minimum signal.

Dose Response Measurements

For IC50 determinations, serial dilutions of compounds (8 mM stock concentration in DMSO) were performed in 100% DMSO with a two-fold dilution factor resulting in 10 final concentrations spanning 80 µM to 0.165 µM. The serially diluted compounds (0.5 µL) were dry spotted into assay plates and were assembled as described for the single-concentration screen. For each concentration, percent inhibition values were calculated and IC50 values and Hill slopes determined using a four-parameter dose-response (variable slope) equation in GraphPad Prism or using XLfit software (IDBS). Some compounds were also tested by dose response in the presence of detergent (0.01% Tween-20 final concentration). In some cases, compounds were also tested by dose response against a form of human histag-GAPDHS expressed in the baculovirus/insect cell system [22]. Buffer conditions were as described above and his-GAPDHS was used at a final concentration of 60 nM in the assay.

Ligand Efficiency Calculation

IC50 values were used to calculate ligand efficiency (LE or Δg) and binding efficiency index (BEI) [29]. Ligand efficiency normalizes the binding energy of the ligand (ΔG = -RTlnIC50) at 300 K (~27°C) to the number of non-hydrogen atoms in the molecule (Δg = ΔG Nnon-H atoms-1) [30], while BEI expresses binding affinity per total molecular weight (MW) of the inhibitor (BEI=-logIC50 MW-1) [29].

Compound Filter Assay

The ability of compounds to interfere with the GAPDHS assay readout was assessed as follows. The enzymatic assay was run kinetically as described above until an absorbance (A340) of 0.7 was reached. Compounds were then added to the reaction to a final compound concentration of 50 µM and the A340 measured immediately after this addition.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for nonlinear regression statistical analysis. GraphPad InStat Student’s two tailed t-test was used for comparing IC50 values, differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

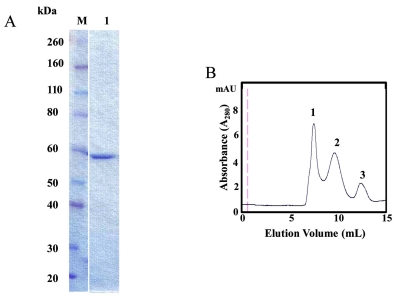

Expression of full-length GAPDHS in E. coli has proven difficult in quantities sufficient for screening a large number of compounds [7]. Substantially better yields and activities were obtained by elimination of the proline-rich N-terminal region [1] that is not required for enzyme activity [22]. When typical E. coli strains were used for expression, mass spectrometry analyses confirmed that mouse GAPDHS and the host bacterial GAPDH formed mixed tetramers, resulting in the co-purification of bacterial and recombinant enzymes (data not shown). A similar observation has been made for the rat GAPDHS expressed in E. coli with the purified tetrameric enzyme consisting of 3 subunits of E. coli GAPDH and 1 subunit of rat GAPDHS [7]. Our approach was to express recombinant human GAPDHS lacking the proline-rich N-terminal region in a GAPDH-deficient E. coli strain (CGSC strain #7563). Further, the form we expressed was a GST-GAPDHS fusion protein to improve solubility. The size and purity of soluble recombinant GST-GAPDHS was confirmed by SDS-PAGE with a band at ~ 60 kDa observed (Fig. 1A). Typical yields were ~13 mg of purified GST-GAPDHS per 6L E. coli culture. Hu GST-GAPDHS protein purified from E. coli was further characterized by analytical size exclusion chromatography as previously described [22]. GST-GAPDHS was applied to a Superose 12 column and eluted as a mixture of three forms (Fig. 1B), with peak 1 eluting in the void volume. Comparison with known protein standards indicated that the elution volumes of peaks 2 and 3 corresponded most closely to the tetrameric and monomeric forms of GST-GAPDHS respectively, with ~75% of the protein estimated as tetrameric, 10% monomeric and the remainder presumably in some aggregated form.

Fig. (1).

Characterization of GST-GAPDHS. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified recombinant human GST–GAPDHS. GST-GAPDHS was expressed in the gapA-deficient E. coli strain DS112 and purified using glutathione-Sepharose. Coomassie-Blue stained 4-12% Bis-Tris gel, lane M, Prestained protein markers (Novex); lane 1, recombinant human GST-GAPDHS (2 µg). (B) Size exclusion chromatography of purified GST-GAPDHS. Purified human GST-GAPDHS was loaded on a Superose 12 column at 0.5 ml/min in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 400 mM NaCl buffer. The molecular size of the peaks indicated by the numbers were estimated as described previously [22].

The GST-GAPDHS fusion protein had enzymatic activity, enabling us to avoid substantial losses that occurred during thrombin cleavage to remove the GST protein tag. Consequently, the uncleaved GST-GAPDHS protein was used for all subsequent studies and will be referred to as GAPDHS from here on.

GAPDHS Assay Development and Optimization

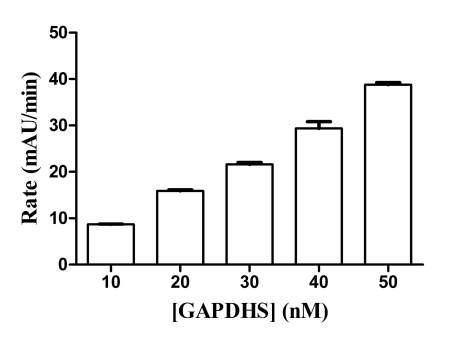

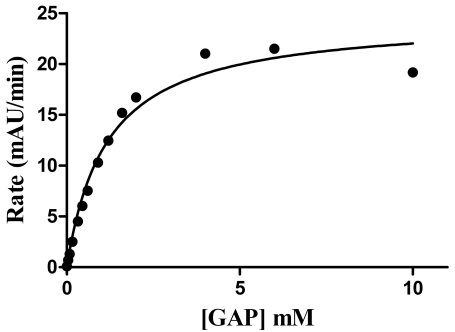

GAPDHS activity was measured using a standard spectrophotometric assay monitoring the accumulation of NADH at 340 nm [23] following the addition of the substrate, DL-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP). The assay was developed with a final assay volume of 50 µL in 384-well format. GAPDHS activity was measured kinetically by taking absorbance readings every 30 sec over 5 min. The GAPDHS activity in the assay was directly proportional to the concentration of enzyme (Fig. 2). The Km values for GAP and NAD were determined as 1.1 mM (Fig. 3) and 0.1 mM (data not shown), respectively. Activity of the purified recombinant human GAPDHS was ~46 U/mg, comparable to the activities of commercial preparations of GAPDH purified from rabbit muscle (Sigma). For HTS, an assay concentration of 30 nM GAPDHS was chosen which provided both an adequate assay window and linear GAPDHS enzyme activity over the time of the assay.

Fig. (2).

GAPDHS Enzyme Titration. GAPDHS was titrated at the indicated concentrations under the final assay conditions. Data points represent average of four determinations per concentration.

Fig. (3).

Determination of the Km value for GAP substrate. GAP was titrated at a 14 point concentration range between 0 and 10 mM in the assay using 8 nM GAPDHS. Km value was calculated using non-linear regression analysis for the Michaelis-Menten equation in GraphPad Prism 5.

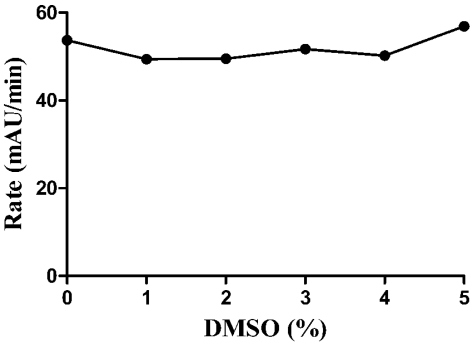

For our preferred HTS scheme, 0.5 µL of compound per well is pre-spotted in 384-well plates giving a final compound concentration of 10 µM in the final 50 µL assay volume. Because the compounds to be screened are dissolved in DMSO, the DMSO tolerance of the assay was assessed. Concentrations up to 5% DMSO had no effect on GAPDHS activity (Fig. 4). For the HTS and dose response experiments, the maximum concentration of DMSO is 1%. Addition of up to 1% BSA was also tested, but found to have no affect on GAPDHS activity in the assay (data not shown). Substrate concentrations were set at 0.5 mM NAD (5x Km NAD) and 0.5 mM GAP (0.5x GAP Km) with the goal of biasing the screen toward detection of GAP competitive compounds.

Fig. (4).

Tolerance of GAPDHS assay to DMSO. DMSO was tested in the GAPDHS HTS assay (30 nM GAPDHS, 50 mM glycine, 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.9, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1% DMSO, 0.5 mM NAD and 0.5 mM GAP) at the indicated concentrations of DMSO.

GAPDHS Assay Automation and Validation

To assess variability of the GAPDHS assay with full automation, triplicate 384-well DMSO plates in a typical “Min-Mid-Max” experiment [28, 31] were analyzed to determine Z’-factor [28] as a measure of assay quality. To facilitate HTS, the assay was simplified into two steps using Multidrop 384 (Thermo Fisher) bulk dispensers (Table 1). The assay was run as a 5 min kinetic read. All plates were pre-spotted with 0.5 µL DMSO using a Biomek NX liquid handling workstation. Initial experiments were conducted in the absence of compounds to evaluate the robustness of the assay window by measuring statistically significant changes in enzyme rates between no GAPDHS (minimum signal ▲), 0.5x GAPDHS concentration (mid signal ♦) and 1x GAPDHS concentration (maximum signal ■) (Fig. 5A).

Table 1.

Automation Protocol for GAPDHS HTS Assay

| Step | Event | Parameter | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-spot | 0.5 µL | Add DMSO/test compound to 384-well plates using Biomek NX |

| 2 | Dispense | 25 µL | Add GAPDHS and NAD solution to a set of ten plates using Multidrop 384 |

| 3 | Incubate | 15 min | Room temperature |

| 4 | Dispense | 25 µL | Add GAP substrate to one plate using Multidrop 384 |

| 5 | Read | ∆A340 | SpectraMax plate reader; 5 min kinetic read |

| 6 | Dispense | 25 µL | Repeat steps 4 and 5 for remaining nine plates |

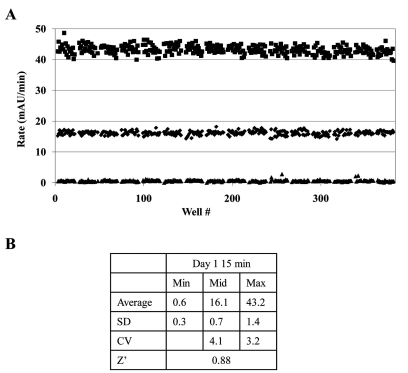

Fig. (5).

GAPDHS assay variability assessment. (A) 384-well plates were pre-spotted with 0.5 µL of DMSO using a Biomek NX. One plate each was used to determine the maximum signal (■), mid signal (♦) and minimum signal (▲). The Min, Mid and Max plates contained final assay concentrations of 0, 16 and 32 nM GAPDHS respectively. After 15 min of pre-incubation, GAP was added and rates determined over 5 min with 30 sec reads. The data represent values measured in individual wells, consisting of 320 replicates for each condition. (B) The variability for inhibition was determined from the max and min plates. Z’-factors, standard deviations (SD) and coefficient of variance (CV) were calculated in Excel.

The data yielded a calculated Z’-factor for individual plates of 0.88 and CVs <5% (Fig. 5B) demonstrating a suitable assay window and acceptable variability for HTS as typically defined [28, 31, 32] and [NIH Chemical Genomics Center Assay Guidance Manual: (http://spotlite.nih.gov/assay/index.php/Table_of_Contents)]. For HTS, typically 10-20 compound plates are screened in one run. To assess the stability of the assay over such a ten 384-well plate run, a variability study was performed allowing compound preincubation with GAPDHS and NAD for 15 min or 60 min to simulate the first and tenth plate conditions, respectively. In comparison, the data yielded a calculated Z’ for individual plates of 0.83 and CVs of 5.03% for the 60 min preincubation study demonstrating the robustness of the assay over the time frame required to screen ten 384-well plates. The assay was repeated for a second day with comparable results for Z’ and CVs (data not shown). The scheme used for HTS was to add the GAPDHS/NAD solution to the 10 plates at 6 min intervals, to add GAP to each plate after its 15 min compound incubation, and then to read immediately thus ensuring that compound incubation times were identical for all wells on all plates (Table 1).

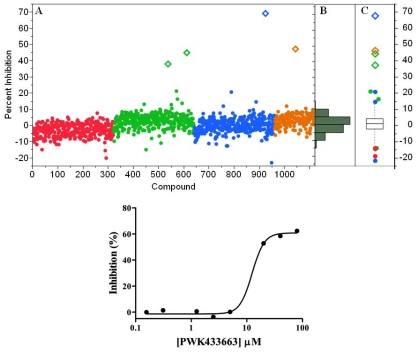

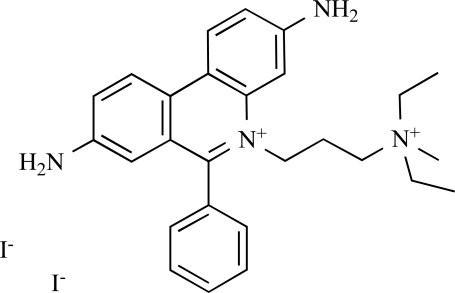

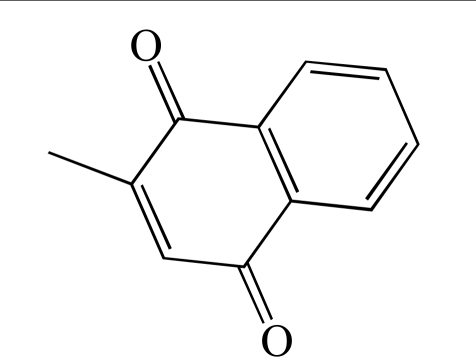

GAPDHS Pilot Screen

As a final validation, a small test set of diverse compounds was screened to determine the performance of the GAPDHS assay under HTS conditions in the presence of typical small molecule compounds. In this pilot screen, the process and the plates with controls were set-up exactly as for the primary screen. We used the Prestwick collection, a purchased compound library made up of 1,120 compounds with established biological activities, 90% of which are FDA-approved drugs. The Prestwick library was screened at 10 µM in the automated GAPDHS assay and hits were identified using a standard deviation based hit-threshold [33] (signal mean (µ) plus 3x the standard deviation (σ) in the compound data, µ+3σ). The Z’-factors for the controls on each of the four plates were all >0.75. From single-point screening of the Prestwick collection, four compounds had percent inhibition values above the 30% threshold (Fig. 6A). The compound distribution data scatter as shown in the histogram (Fig. 6B) and box plot (Fig. 6C) shows a normal (unskewed) distribution with a mean set to zero. Two of the four compounds confirmed with dose response in this assay (Table 2), including propidium iodide with an IC50 value of 28 µM (Fig. 6D), yielding an overall hit-rate of 0.2%.

Fig. (6).

Pilot screening results from the Prestwick FDA-approved drug library. (A) Pilot screen scatter for the 1,120 compound Prestwick library. Each point represents the percent inhibition value for a single compound. Each 384-well plate is represented by a different color. The threshold for defining actives is set at µ+σ. (B) Histogram of screening data showing a normal distribution. (C) Box plot representing quartiles and outliers. (D) Dose response confirmation for active compound PWK-433663 (propidium iodide) showing a 28 µM IC50 value (average of three independent determinations).

Table 2.

Inhibitors of Human GAPDHS Identified from a Pilot Screen of the Prestwick Set

| No. | Compound IDa | Name | Structure | % Inhibition in HTS | IC50 (µM)b | Hill Slope Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PWK-433663 | Propidium iodide |  |

69.2 | 28 | 1.01 |

| 2 | PWK-433331 | Menadione |  |

37.9 | 40% inhibition at 80 µM | 1.10 |

Prestwick chemical identifier number.

For IC50 determinations, serial dilutions of compounds were tested starting at a high concentration of 80 µM. If 50% inhibition was not achieved at top dose, value is shown as % inhibition at 80 µM.

IC50 and Hill slope values determined by XLfit software (ID Business Solutions).

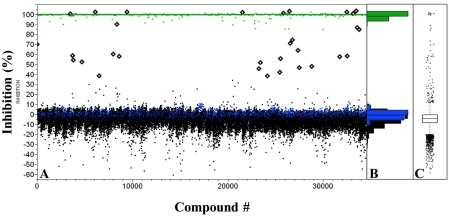

GAPDHS HTS and Inhibitor Identification

To identify inhibitors of human GAPDHS, a diverse collection of 28,880 small organic molecules selected from the purchased Asinex set was screened in 384-well format (90 plates) at 10 µM single point concentration. Actives were identified using a standard deviation based-hit threshold (µ+3σ). GAPDHS percent inhibition values were plotted for each compound (Fig. 7A). The compound distribution data scatter as shown in the histogram (Fig. 7B) and box plot (Fig. 7C) shows a normal (un-skewed) distribution and a standard deviation in compound data of 8.8%. The average Z' for this screen was 0.88. Thirty one active compounds exhibiting GAPDHS inhibition values above the 30% threshold were identified (Fig. 7A) for a primary hit rate of 0.1%.

Fig. (7).

High throughput screening of human GAPDHS. Compounds were pre-spotted (0.5 µl) into 384-well plates and the human GAPDHS enzyme assay carried out in a final volume of 50 µl as described in the materials and methodology. (A) Scatterplot showing percent inhibition values for compounds screened and with actives shown as diamonds above a 3 sigma threshold. Positive controls are shown in green, negative controls in blue and Asinex compounds in black. (B) Histogram of screening data showing a normal distribution and, (C) Box plot representing quartiles and outliers.

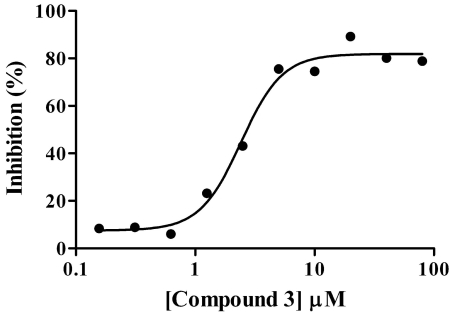

Dose response/IC50 determinations were conducted for compounds identified as single-point actives. Data from these assays were analyzed in ActivityBase and plots were assessed for IC50 and Hill slope values. Of the 31 compounds tested in dose response, nine compounds exhibited sigmoidal dose response behavior and were confirmed as hits with IC50 values ranging from 1.8 to 42.5 µM for an overall confirmation rate of 29% (Table 3). Inhibition by three other compounds (12-14 in Table 3) was trending upwards at the highest doses tested. A second round of screening of the remaining Asinex collection yielded two more hits after confirmation (10 and 11 in Table 3). For all fourteen hits, the percent inhibition values from the primary screen, IC50 values and Hill slope values are shown in Table 3. The dose-response curve for the most potent GAPDHS inhibitor identified from the diversity screen, (compound 3), is shown in Fig. (8) and exhibits an IC50 value of 1.8 µM and a Hill slope of 1.1.

Table 3.

Activities of Confirmed Hits from Chemical Library Screen of Recombinant Human GAPDHS

| No. | GST-GAPDHS | His-GAPDHS IC50 (µM)f | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Inhibition in HTS | IC50 (µM)a | Hill Slope Valueb | LEc (kcal mol-1 non-H atom-1) | BEId | ||

| 1 | 70.1% | 10.7 | 1.7 | 0.30 | 17 | 13 |

| 2 | 102.5% | 6.5 | 1.1 | 0.47 | 24 | 11 |

| 3 | 90.3% | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.53 | 28 | 3 |

| 4 | 64.2% | 16.8 | 1.0 | 0.55 | 28 | 30 |

| 5 | 56.0% | 8.3 | 1.4 | 0.32 | 16 | 10 |

| 6 | 103.4% | 11.9 | 1.0 | 0.27 | 14 | 12 |

| 7 | 45.9% | 20.8 | 0.9 | 0.21 | 11 | 22 |

| 8 | 103.5% | 36.1 | 1.1 | 0.38 | 20 | 44 |

| 9 | 33.8% | 42.5 | 1.8 | 0.40 | 18 | 26 |

| 10 | 51.3% | 45% inhibition at 80 µM | 0.6 | N/Ae | N/A | ND |

| 11 | 101.1% | 11.0 | 1.4 | 0.36 | 18 | 13 |

| 12 | 86.9% | 30% inhibition at 80 µM | N/A | N/A | N/A | ND |

| 13 | 52.6% | 30% inhibition at 80 µM | N/A | N/A | N/A | ND |

| 14 | 102.0% | 30% inhibition at 80 µM | N/A | N/A | N/A | ND |

For IC50 determinations, serial dilutions of compounds were tested starting at a high concentration of 80 µM versus the E. coli expressed GST-GAPDHS. If 50% inhibition was not achieved at top dose, value is shown as % inhibition at 80 µM. IC50 values are the average for at least three independent determinations.

IC50 and Hill slope values determined by XLfit software (ID Business Solutions).

LE: ligand efficiency (Δg=ΔG Nnon-H atoms-1), a measure of the binding energy of the ligand per non-hydrogen atom [30].

BEI: binding efficiency index (BEI=-logIC50 MW-1) a measure of the binding affinity of the ligand per ligand molecular weight [29].

N/A not applicable, as a dose response curve was not generated.

IC50 determinations from dose response against the baculovirus expressed his-GAPDHS [22]. Values determined by XLfit software (ID Business Solutions). ND, not determined.

Fig. (8).

IC50 value determination for compound 3. Compound 3 was serially diluted in DMSO and the dose response assay carried out as detailed in materials and methodology and then transferred to assay plates for the GAPDHS enzyme assay. The 1.8 µM IC50 value for compound 3 was calculated from the average of three independent determinations.

To assess hits based on both potency and molecular weight, values were calculated for ligand efficiency (LE) and binding efficiency index (BEI) (Table 3). These parameters allow inhibitor activities to be compared independent of possible molecular weight biases [29, 30]. Based on IC50 values, compounds 2 and 3 were the most inhibitory (6.5 and 1.8 µM, respectively, Table 3). These compounds have a relatively low molecular weight (216 and 207 Da, respectively) and maintained their potent inhibitory ranking after using LE and BEI equations to normalize inhibitory activity to molecular weight among the compounds identified in our screen. An order of magnitude higher IC50 (16.8 µM) was observed for compound 4 (170 Da), though the relative potency of this inhibitor increased significantly after normalization. Of the inhibitors yielding a dose-response curve, compounds 6 and 7 (among the highest MW in the set) had the weakest LE and BEI rating, while their IC50 values were mid-range. LE values varied from 0.21 to 0.55 kcal mol-1 non-H atom-1; while BEI ranged from 11 to 28. In general, comparable LE and BEI values were obtained. In both cases higher numbers correspond to increased efficiency.

Compounds eliciting dose-response curves using the GST-GAPDHS were also tested against the his-GAPDHS form of the enzyme that we have recently produced using the baculovirus/insect cell system [22]. All of the compounds tested had comparable IC50 values on both GAPDHS enzymes (Table 3).

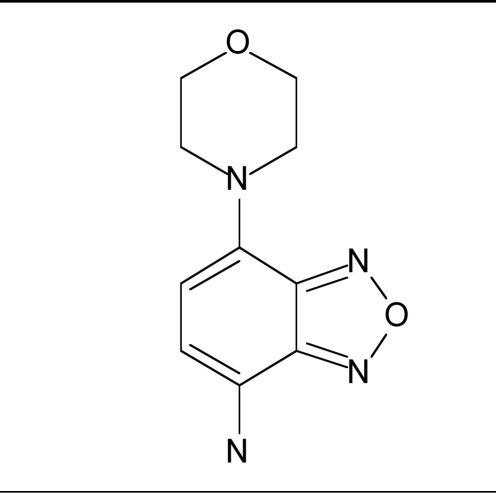

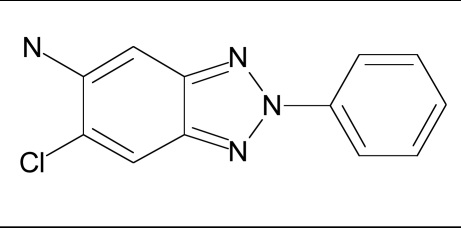

To assess selectivity of the GAPDHS hits versus the somatic form of GAPDH, the GAPDHS hits were tested for dose-response in a comparable assay using commercially available somatic GAPDH purified from human erythrocytes (Sigma). The assay for human GAPDH was first validated (data not shown) using procedures previously described for the GAPDHS assay. For a subset of compounds, the corresponding IC50 values versus the somatic GAPDH along with compound structures are shown in Table 4. For compounds 8 and 9 we observed no statistically significant differences between the IC50 values for sperm GAPDHS versus somatic GAPDH. Because the remaining compounds in Table 4 did not yield complete dose response curves we could not conclude whether there were any statistical differences between the two isozymes.

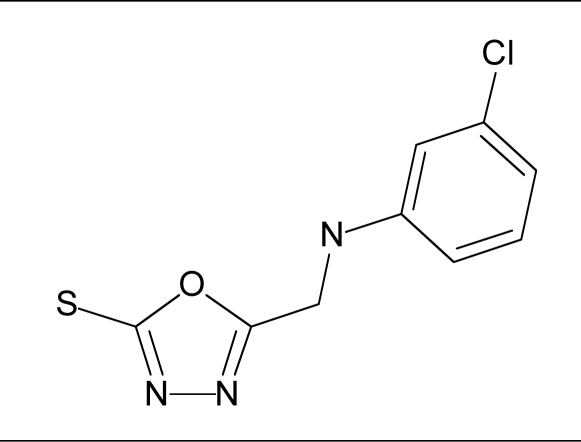

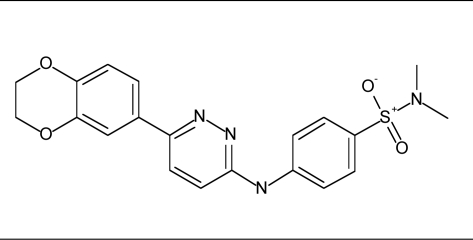

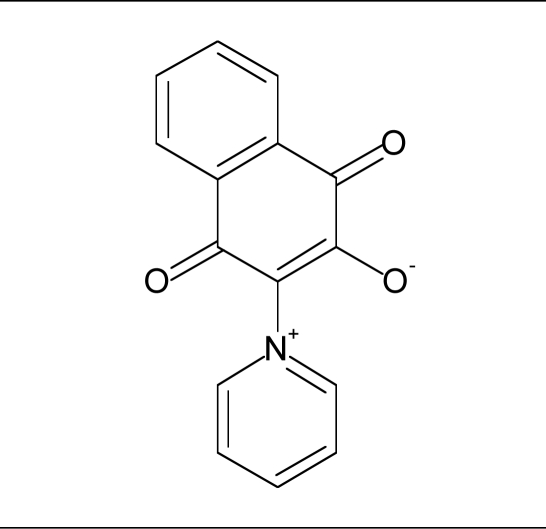

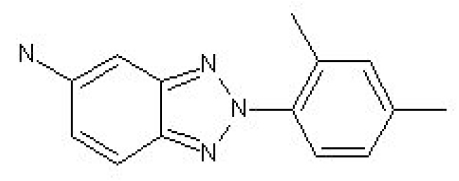

Table 4.

Recombinant GAPDHS Activity Versus Somatic GAPDH and Structures for a Subset of GAPDHS Hits

| Compound No. | Structure | GAPDHS IC50 (µM)* | Somatic GAPDH IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 |  |

36.1 | 54.9 |

| 9 |  |

42.5 | 66.4 |

| 10 |  |

45% inhibition at 80 µM | <30% inhibition at 80 µM |

| 12 |  |

30% inhibition at 80 µM | <30% inhibition at 80 µM |

| 13 |  |

30% inhibition at 80 µM | <30% inhibition at 80 µM |

| 14 |  |

30% inhibition at 80 µM | <30% inhibition at 80 µM |

For IC50 determinations, serial dilutions of compounds were tested starting at a high concentration of 80 µM. If 50% inhibition was not achieved at top dose, value is shown as % inhibition at 80 µM. IC50 values determined by XLfit software (ID Business Solutions).

K-means clustering was performed to group compounds by similarity with a 0.65 cutoff. Two of the 14 compounds (compounds 13 and 14) that showed some inhibition of GAPDHS were of the same scaffold. The remaining 12 compounds were structurally unrelated.

Follow Up Assays

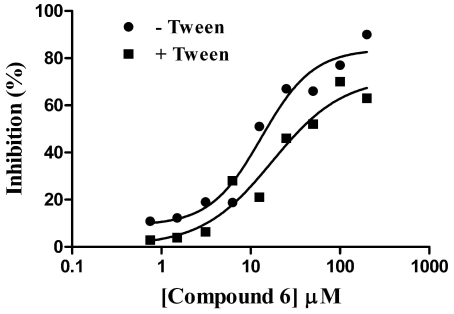

To further confirm GAPDHS hits and eliminate false positives, a series of follow up assays were carried out. Two of the confirmed compounds (displaying full dose response) from Table 3 (compounds 4 and 6) were repurchased from Asinex as dry powders to test in follow up assays. Using dry powder, compound 6 (Table 3) had an IC50 value of 13 µM (Fig. 9) very close to that observed (11 µM) from dose response using master plate derived compound (Table 3). Further, this compound had a comparable IC50 value of 17 µM when tested in the presence of 0.01% Tween-20 (Fig. 9). Menadione, identified from the pilot screen of the Prestwick set (Table 2), also displayed comparable IC50 values of 47 µM and 53 µM respectively when tested in the absence and presence of 0.01% Tween-20.

Fig. (9).

IC50 value determinations for compound 6 in the presence and absence of detergent. Compound 6 was serially diluted in DMSO and the GAPDHS enzymatic assay carried out in the absence or presence of 0.01% Tween-20.

These compounds were also assessed for their ability to interfere with the GAPDHS enzymatic assay. The GAPDHS assay was first run kinetically in the absence of any compound until an A340 of ~0.7 was reached. Compounds were then added to a final concentration of 50 µM and the A340 read again immediately after compound addition. The resulting A340 values for the GAPDHS assay with menadione, compound 4 and compound 6 were essentially unchanged at 0.78, 0.67 and 0.69, respectively, suggesting that these compounds do not quench the NADH signal.

DISCUSSION

GAPDHS is expressed only in male germ cells and is required for sperm motility and male fertility [10]. It is an essential enzyme in the central metabolic pathway of glycolysis and is the only GAPDH isozyme in sperm. Consequently, GAPDHS has been proposed as an excellent contraceptive target, particularly if this isozyme can be selectively inhibited without blocking the somatic GAPDH enzyme found in all other tissues. We were able to produce human GAPDHS by expression of a GST-GAPDHS fusion protein in an E. coli strain lacking endogenous GAPDH, and the availability of this enzyme provides an excellent basis for the identification of compounds that inhibit the activity of human GAPDHS. The GST-GAPDHS was pure as judged by SDS-PAGE and existed predominantly as a tetramer as assessed by analytical size exclusion chromatography. It is unclear why some of the GST-GAPDHS eluted in the void volume, although this may be due to the solubility of the enzyme when produced in E. coli or due to increased enzyme association due to the GST tag. Although some of the GST-GAPDHS protein eluted at the void and is presumably aggregated, this GST-GAPDHS enzyme preparation had a higher specific activity (46 U/mg) than the his-GAPDHS form (28 U/mg) that we have recently expressed in the baculovirus/insect cell expression system [22].

We first adapted and validated an HTS assay in 384-well format based on a standard GAPDH spectrophotometric assay [23] to measure inhibition of recombinant human GAPDHS activity. The assay signal was demonstrated to be proportional to GAPDHS enzyme concentration and up to 5% DMSO was tolerated in the assay. As assessed by whole 384-well plate min-max variability experiments, the assay was robust with Z’ values >0.8 and the assay window was stable for 60 minutes allowing ten plates to be run in a single batch. Alpha-chlorohydrin has been reported as a GAPDHS inhibitor (reviewed in [11]), with its metabolite S-3-chlorolactaldehyde being the actual inhibitory form [34, 35]. Our attempts to generate S-3-chlorolactaldehyde and test it as an inhibitor of GAPDHS are ongoing. In the absence of a GAPDH control inhibitor, a no enzyme addition was used as the minimum control with the expectation that the Z’ would be higher relative to using a known inhibitor for the minimum control.

We and others have determined that a test screen of a diverse set of compounds such as the Prestwick set has great value in evaluating an assay’s response to compounds with varied structures (rather than evaluating with just DMSO) under HTS conditions [31]. The value of the Prestwick collection is that it may also yield interesting inhibitory compounds that already have a wealth of associated data [36, 37]. Screening of the 1,120 compound Prestwick collection against recombinant human GAPDHS, yielded two confirmed inhibitors, propidium iodide and menadione. One of these compounds, menadione, was previously identified as a non-selective inhibitor of GAPDH isozymes in vivo (PMID: 12788228, PMID: 2353814). To our knowledge, no reports of propidium iodide inhibiting GAPDH enzymes have been published. Both menadione and propidium iodide were also identified as actives [22] when we subsequently screened the Prestwick collection against the purified his-GAPDHS expressed in the baculovirus/insect cell system.

We used the validated GAPDHS high throughput assay to screen a diverse library of small molecules to identify inhibitors of GAPDHS activity. From the screen, confirmed inhibitors of GST-GAPDHS had IC50 values ranging from 1.8 to 42.5 µM. As an additional confirmation, we also tested those compounds eliciting dose-response curves versus the his-GAPDHS form of the enzyme that we have recently produced using the baculovirus/insect cell system [22] and comparable IC50 values were obtained on both forms of GAPDHS.

Hits identified during the high-throughput screen varied in potency. This variation may correlate directly to ligand molecular weight. Two related equations have been introduced to normalize potency to molecular weight to improve comparisons of ligand activity. Ligand efficiency (LE) normalizes binding energy to the number of non-hydrogen atoms in the ligand [30], whereas the binding efficiency index (BEI) normalizes binding affinity to ligand molecular weight [29]. The latter index was introduced to account for large MW differences apparent among diverse heteroatoms [29]. We used both equations to divorce ligand inhibitory activity from a possible MW bias in our data. In general, the different equations yielded comparable results (Table 3). Ranking compound activity by IC50 or LE/BEI would result in asymmetric lists, suggesting molecular weight affects the observed IC50 values. While the relative ranking of some inhibitors improved upon normalization (notably compound 4), the most potent and relatively low molecular weight compounds (compounds 2 and 3) remained at the top of both lists, suggesting at least three promising GAPDHS inhibitory hits have been identified in this study.

A critical phase of hit confirmation is to distinguish those compounds that are targeting the enzymatic activity from those that might be acting as false positives [32]. Dose response behavior was used to confirm hits identified during HTS. The confirmation rate of 29% suggested that a number of false positives may have been eliminated during dose response testing. False positives may act by interfering with assay read-out, chemically modifying the enzyme or by aggregation-based affects [38]. Compounds with dose-response curves were further analyzed using Hill slope values. Those with high Hill slopes (>2) would typically be eliminated to avoid compounds that may act as aggregators or covalent-modifiers [38].The majority of confirmed GAPDHS inhibitors had Hill slope values between 0.9 and 1.1, with none having values >2. However, at this stage we did not eliminate any hits based solely on Hill slope value, since compounds acting allosterically or irreversibly may also have interest as potential leads as GAPDHS inhibitors. Another mechanism of artifactual inhibition is compound aggregation followed by interaction with the enzyme [38-40]. This inhibition can be distinguished by its detergent sensitivity and a counter-screen using low concentrations of detergent was able to discriminate between classical 1:1 inhibitors and promiscuous aggregators [38, 39]. We used a concentration of Tween-20 (0.01%) at the higher end of the range of suggested detergent concentrations [39], to assess whether inhibition profiles were detergent-sensitive or detergent-resistant. We found that inclusion of Tween-20 had no effect on the inhibition profile of compound 6, indicating that it is a standard 1:1 reversible inhibitor. Assays based on measuring absorbance are also susceptible to compound-dependent interference [31, 32]. This was minimized in part by running our assay in kinetic mode. In addition, to assess compound interference, we used a filter assay in which compound is added after completion of the enzymatic reaction and the absorbance immediately read. For those compounds that we tested from dry powder (compounds 4, 6, 10, 11, 12 and menadione), we did not observe any compound-dependent quenching of the NADH signal.

All the compounds identified as confirmed hits in Table 3 will be either re-sourced as dry powders or resynthesized for further confirmation and biological testing. Unfortunately, the most active compound (compound 3, Table 3) is unavailable through any commercial supplier so we are currently planning to synthesize it. Compounds will be tested in counterscreens decribed herein to assess detergent sensitivity and assay interference. Isothermal calorimetry will also be used to measure the stoichometry of binding. Confirmed hits will then be tested for their ability to inhibit sperm function, including effects on quantitative parameters of sperm motility determined by computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) and CASAnova, a recently developed support vector machines model [41].

A number of approaches will be taken to identify additional GAPDHS inhibitors, including substructure searches to identify similar compounds from our in house library and external libraries, and using structure-based drug design which has already proved successful for targeting GAPDH in parasites [15, 18-20]. Structures for human GAPDHS are available in the pdb database (3PFW and 3H9E) and will be used for assessing both our current hits and for structure-based drug design approaches. Alternative assay formats may also be utilized for additional screens including coupled assays for GAPDHS [42] and those using the resazurin/diaphorase system [43].

Structures and selectivity data for those compounds not included in Table 4 were not disclosed for intellectual property considerations. Additional studies using purchased powders are underway to further evaluate these compounds and identify others that inhibit GAPDHS, focusing on those that exhibit the highest potency and selectivity for the sperm isozyme. Those GAPDHS inhibitors showing little selectivity versus the somatic form may still have utility as molecular probes to assess the role of GAPDHS in sperm function. Details on the mechanism of action, structure-activity relationships, selectivity, and activity in sperm assays of the most potent GAPDHS inhibitors will be detailed in a forthcoming manuscript.

CONCLUSION

A high throughput assay for sperm-specific glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHS) was optimized and validated for the identification of small molecule inhibitors. The robustness of the GAPDHS primary assay was confirmed by whole plate variability studies. Screening of a small molecule diversity library identified a number of inhibitors of recombinant human GAPDHS with IC50 values ranging from 1.8 to 42 µM. These compounds may provide useful scaffolds as molecular tools to probe the role of GAPDHS in sperm function or for developing potent and selective GAPDHS inhibitors leading to novel contraceptive agents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by cooperative agreement U01 HD060481 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH; subproject CIG-05-10 from CICCR, a program of CONRAD, Eastern Virginia Medical School; the Golden LEAF Foundation and the BIOIMPACT Initiative of the state of North Carolina through the Biomanufacturing Research Institute & Technology Enterprise (BRITE) Center for Excellence at North Carolina Central University.

The authors thank Ginger Smith (BRITE, NCCU) for automation technical assistance, and Dr. Mary Berlyn and the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University, New Haven, CT) for providing E. coli strain CGSC#7563.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest for the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bunch DO, Welch JE, Magyar PL, Eddy EM, O'Brien DA. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase-S protein distribution during mouse spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:834–41. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.3.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danshina PV, Geyer CB, Dai Q, et al. Phosphoglycerate kinase 2 (PGK2) is essential for sperm function and male fertility in mice. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:136–45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eddy EM, Welch JE, Mori C, Fulcher KD, O'Brien DA. Role and regulation of spermatogenic cell-specific gene expression: enzymes of glycolysis. In: Bartke A, editor. Function of somatic cells in the Testis, Serono Symposia USA. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 362–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li SS, O'Brien DA, Hou EW, Versola J, Rockett DL, Eddy EM. Differential activity and synthesis of lactate dehydrogenase isozymes A (muscle), B (heart), and C (testis) in mouse spermatogenic cells. Biol Reprod. 1989;40:173–80. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod40.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch JE, Schatte EC, O'Brien DA, Eddy EM. Expression of a glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene specific to mouse spermatogenic cells. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:869–78. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danshina PV, Temple B, Williams KP, Sexton JZ, Yeh LA, O'Brien DA. New strategies for male fertility control: sperm glycolytic enzymes as targets. J Androl. 2009;30(Suppl):23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frayne J, Taylor A, Cameron G, Hadfield AT. Structure of insoluble rat sperm glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase via heterotetramer formation with E. coli glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase reveals target for contraceptive design. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22703–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch JE, Brown PL, O'Brien DA, et al. Human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase-2 gene is expressed specifically in spermatogenic cells. J Androl. 2000;21:328–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch JE, Barbee RR, Magyar PL, Bunch DO, OBrien DA. Expression of the spermatogenic cell-specific glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDS) in rat testis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:1052–60. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miki K, Qu W, Goulding EH, et al. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase-S, a sperm-specific glycolytic enzyme, is required for sperm motility and male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407708101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones AR. The antifertility actions of alpha-chlorohydrin in the male. Life Sci. 1978;23:1625–45. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C, Cooper TG. A re-appraisal of the post-testicular action and toxicity of chlorinated antifertility compounds. Int J Androl. 1999;22:130–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jelks KB, Miller MG. Alpha-chlorohydrin inhibits glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in multiple organs as well as in sperm. Toxicol Sci. 2001;62:115–23. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/62.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kragten E, Lalande I, Zimmermann K, et al. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, the putative target of the antiapoptotic compounds CGP 3466 and R-(-)-Deprenyl. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5821–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verlinde CL, Bressi JC, Choe J, et al. Protein structure-based design of anti-protozoal drugs. J Braz Chem Soc. 2002;13:843–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verlinde CL, Hannaert V, Blonski C, et al. Glycolysis as a target for the design of new anti-trypanosome drugs. Drug Resist Updates. 2001;4:50–65. doi: 10.1054/drup.2000.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saavedra E, Encalada R, Pineda E, Jasso-Chávez R, MorenoSánchez R. Glycolysis in Entamoeba histolytica. FEBS J. 2005;272:1767–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H, Feil IK, Verlinde CL, Petra PH, Hol WG. Crystal structure of glycosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Leishmania mexicana: implications for structure-based drug design and a new position for the inorganic phosphate binding site. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14975–86. doi: 10.1021/bi00046a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kundu S, Roy D. Computational study of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Entamoeba histolytica: implications for structure-based drug design. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2007;25:25–33. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2007.10507152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souza DH, Garratt RC, Araújo AP, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi glycosomal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: structure, catalytic mechanism and targeted inhibitor design. FEBS Lett. 1998;424:131–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seta FD, Boschi-Muller S, Vignais ML, Branlant G. Characterization of Escherichia coli strains with gapA and gapB genes deleted. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5218–21. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5218-5221.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamson DR, House AJ, Danshina PV, et al. Recombinant human sperm-specific glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHS) is expressed at high yield as an active homotetramer in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2011;75:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmalhausen EV, Muronetz VI, Nagradova NK. Rabbit muscle GAPDH: non-phosphorylating dehydrogenase activity induced by hydrogen peroxide. FEBS Lett. 1997;414:247–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Copeland L, Zammit A. Kinetic properties of NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the host fraction of soybean root nodules. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;312:107–13. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen RS, Zylka MJ, Scott JE. A high throughput assay to identify small molecule modulators of prostatic acid phosphatase. Curr Chem Genomics. 2009;3:42–9. doi: 10.2174/1875397300903010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sexton JZ, Wigle TJ, He Q, et al. Novel inhibitors of E. coli RecA ATPase activity. Curr Chem Genomics. 2010;4:34–42. doi: 10.2174/1875397301004010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang JH, Chung TDY, Oldenburg KR. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abad-Zapatero C, Metz JT. Ligand efficiency indices as guideposts for drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:464–9. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopkins AL, Groom CR, Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:430–1. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams KP, Scott JE. Enzyme assay design for high-throughput screening. In: Janzen WP, Bernasconi P, editors. Methods in molecular biology. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 107–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inglese J, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, et al. High-throughput screening assays for the identification of chemical probes. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:466–79. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coma I, Herranz J, Martin J. Statistics and decision making in high-throughput screening. In: Janzen WP, Bernasconi P, editors. Methods in molecular biology. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 69–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford W. Glycolysis and sperm motility: does a spoonful of sugar help the flagellum go round? Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:269. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevenson D, Jones A. The action of (R)- and (S)-alpha-chlorohydrin and their metabolites on the metabolism of boar sperm. Int J Androl. 1984;7:79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1984.tb00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen M, Wang J, Lu J, et al. The anti-helminthic niclosamide inhibits Wnt/Frizzled1 signaling. Biochemistry. 2009:10267–74. doi: 10.1021/bi9009677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sexton JZ, He Q, Forsberg LJ. High content screening for nonclassical peroxisome proliferators. Int J High Through Screen. 2010;1:127–40. doi: 10.2147/IJHTS.S10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, et al. A high-throughput screen for aggregation-based inhibition in a large compound library. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2385–90. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan AJ, Gray NM, Lowe PN, Chung C. Effect of detergent on “promiscuous” inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3448–51. doi: 10.1021/jm0340896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoichet BK. Interpreting steep dose-response curves in early inhibitor discovery. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7274–7. doi: 10.1021/jm061103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodson SG, Zhang Z, Tsuruta JK, Wang W, O'Brien DA. Classification of mouse sperm motility patterns using an automated multiclass support vector machines model. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1207–15. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furfine CS, Velick SF. The acyl-enzyme intermediate and the kinetic mechanism of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bembenek ME, Kuhn E, Mallender WD, Pullen L, Li P, Parsons T. A fluorescence-based coupling reaction for monitoring the activity of recombinant human NAD synthetase. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005;3:533–41. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]